ABSTRACT

As an important facilitator in e-government and society in general, Open SDI merits an assessment of its characteristics and the monitoring of its development. The aim of the study was the proposal of the SDI openness assessment approach based on existing openness assessment frameworks, as well as the presentation of the Polish Spatial Data Infrastructure (PSDI) development towards openness. The results indicated that ten geodetic and cartographic databases fulfilled ten out of eleven criteria of data openness, according to the methodological assumptions, and reached a 3-star level of openness. The need for further development of the infrastructure towards sharing public administration data is recognized, as well as non-governmental data that meet the open data criteria, thus contributing to the openness of the SDI. The proposed assessment method, referenced to a five-level data openness system and providing clear scoring benchmarking for assessing SDI openness, may be used for comparative analysis of SDI openness in different countries, including EU Member States that draw on the experience of the implementation of the INSPIRE Directive.

1. Introduction

The term ‘open’ is used for data that anyone is free to access, use, modify and share – subject, at most, to measures that preserve provenance and openness (http://opendefinition.org/okd/). Two dimensions of data openness are recognized: data must be both legally and technically open (Pasquetto, Sands, and Borgman Citation2015; European Data Portal Citation2018; https://okfn.org/).

Legal openness means that data must be placed in the public domain or be available under open license. The data should be accessible to the widest possible range of users with the possibility to be used for any purpose, including business and non-commercial use, whereas technical openness means that data must be published in a (electronic) machine-readable non-proprietary format to facilitate its re-use and further processing without requiring any licensed commercial software (Dulong de Rosnay and Janssen Citation2014; Directive Citation2019; European Data Portal Citation2019). The entire dataset should be available for download, and in spite of many useful opportunities for a web application programming interface (API) or similar services like geoportals, bulk access also seems to be a profitable publishing practice from the point of view of programming, simplicity and directness (https://opendatahandbook.org/guide/en/how-to-open-up-data/). Moreover, open data should meet at least some basic quality requirements, since users − although they often do not state such needs − expect the data to be complete and up-to-date.

Legislation on open public data has already been established in many countries, e.g. the Open, Public, Electronic and Necessary (OPEN) Government Data Act (Foundations Citation2019) providing a comprehensive, government-wide mandate for federal agencies to publish all their information as open data, using standardized, non-proprietary formats, in the US. Across the pond, the EU Directive on open data and the re-use of public sector information, also referred to as the ‘Open Data Directive’ (Directive Citation2019), prompts EU Member States to facilitate the re-use of public sector data with minimal or no legal, technical and financial restraints and to make available datasets that may, potentially, have a high impact on society and the economy (European Data Portal Citation2019). The term government data refers to all data and information created, collected and stored by public administration bodies or organizations subject to public administration (also referred to as Public Sector Information – PSI). Citizens are interested in ‘open government data’ (OGD), as they no longer want to be exclusively passive recipients of legislation; instead, they want to increase their civic responsibility and seek constructive ways to engage in public policy-making (Weerakkody, Irani, and Kapoor Citation2017; Diaz and Maso Citation2014).

While there is an abundance of data available today, open data awareness is necessary to make potential users familiar of the existence, characteristics and possibilities of such data. As such, ensuring discoverability and searchability is another significant open data challenge (Dulong de Rosnay and Janssen Citation2014; Inkpen, Gauci, and Gibson Citation2020).

The practical benefits of ‘openness’ can be impressively magnified by the ability to combine different distributed datasets together. Indeed, an infrastructure linking the existing open access repositories in the EU has been created and access has been provided through a portal (www.europeandataportal.eu). Nevertheless, this does not exhaust the Open Spatial Data Infrastructure (Open SDI) issue. It should be remembered that in the first generation of Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDIs), headed by the national SDI of the US, the precursor of sharing and opening (geographic) information, data has been the main driver of development and the main goal of government-driven initiatives. Conversely, the next generation of SDIs is driven by user needs, with focus on the use of both data and data applications, therefore resulting in greater stakeholder influence on SDI development (e.g. Masser Citation2005; Nebert Citation2004; Crompvoets et al. Citation2008; Zwirowicz-Rutkowska and Michalik Citation2016; Imran Citation2019). By the same token, in the case of Open SDI, users should be prioritized.

The term Open SDI is used for spatial data infrastructures that are conceptually open to the participation of all key stakeholders in terms of both open data provision, and the governance and implementation of the infrastructure. The set of key stakeholders of the infrastructure encompasses citizens, research institutions, private organizations and other businesses and non-governmental actors (Vancauwenberghe et al. Citation2018; Vancauwenberghe and van Loenen Citation2018). Therefore, the development and implementation of an Open SDI is not only about providing access to data according to open data principles allowing data re-use but, moreover, about organizing and governing the infrastructure in an open manner, enabling and stimulating the participation of non-government actors (e.g. Vancauwenberghe et al. Citation2018; Gil et al. Citation2012). Therefore, on the one hand, Open SDI contributes to the improvement of the digital competence of public administration and e-government development. On the other, open SDI contributes to the development of the information society through its empowerment and public participation in public affairs or policy-making processes, as well as to meeting (society) information needs, which in turn contributes to the development of the service sector and entrepreneurship. Simultaneously, Open SDI contributes to an open data ecosystem as defined by Zuiderwijk, Janssen, and Davis (Citation2014), including elements of publishing, searching, evaluating and viewing data and its metadata or analyzing, combining and visualizing data.

Since Open SDI contributes to e-government and is also an important tool benefiting society, it seems essential to assess its characteristics and monitor its development. The related literature provides some assessment frameworks and initiatives in the field of the SDI with particular emphasis on the issue of openness both of spatial repositories and the infrastructure organizing frames. The framework developed by Vancauwenberghe et al. (Citation2018) distinguishes three openness assessment categories as follows: readiness and impact of the SDI and data openness. The method follows the process approach, which includes the phases of initial assessment and implementation of the open data initiative, as well as the analysis of implementation effects, benefits and influences. The applicability of the method was presented for two datasets, namely the address data and large-scale topographic data, and resulted in the Map of Open SDI in Europe including 28 EU Member States, as well as Norway. In turn, the development of the indicators describing the data openness category was introduced by Mulder, Wiersma, and Van Loenen (Citation2020). The testbed was two datasets, i.e. the road and parcel databases in each of the researched four countries located worldwide, i.e. Canada, Brazil, Australia and the Netherlands. Undoubtedly, as the opening of data repositories progresses in many countries (Open Data Maturity Report Citation2020; Open Data Inventory Executive Summary, Citation2021), the need to investigate its links with the development of different components of national open SDIs and monitoring changes become essential. The components include, among others, datasets; administrators; users; procedures and SDI policies and goals; software; business context and objectives of organizations and investors implementing an SDI. This entails demand for studies on the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of open spatial data that are available, as well as some issues of the open infrastructure management. It is also assumed that initiatives measuring open data with their analysis and methodology interpenetrate the instruments supporting the assessment of open SDI, which stimulates the improvement and development of the methods, as well as the consideration of integration of other assessment categories, indicators or measuring schemas.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. The first objective is to propose an approach to assess the openness of SDIs based on the existing openness assessment frameworks and extended with dimensions and indicators related to the technical perspective of open data implementation. The second objective is to present the open spatial data development through the Polish Spatial Data Infrastructure (PSDI), taking into account ten geodetic and cartographic databases.

2. Open geodetic and cartographic data

In Poland, spatial data available in the SDI are collected by many central institutions and local government units at all levels. The largest spatial data resources are recorded in the State Geodetic and Cartographic Resource (Polish abbreviation: PZGiK). They are defined in the Geodetic and Cartographic Law (Citation1989) as

datasets maintained pursuant to the act by the bodies of the Surveying and Cartography Service, the maps, registers, lists and compilations created on the basis of such datasets, documentation containing the results of geodetic and cartographic works or documents created as a result of such works, as well as aerial and satellite imagery.

The geodetic data collected in the State Geodetic and Cartographic Resource are also the reference data for many state registers, whose features are located with the use of geodetic data, e.g. land plots or address points.

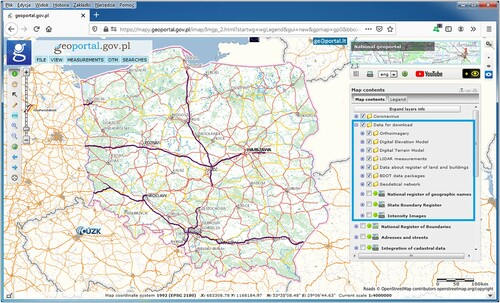

The data recorded in the State Geodetic and Cartographic Resource are crucial for the functioning of the Polish Spatial Data Infrastructure, serving as references for the thematic data (Izdebski Citation2020; Izdebski and Seremet Citation2020). The PSDI also comprises other important data, e.g. pertaining to geology, hydrography, environmental protection or communication networks. The main access point to the PSDI resources is the geoportal.gov.pl service.

Thanks to an amendment to the Geodetic and Cartographic Law (Citation1989), survey and cartographic data, which until now were made available through paid portals, have become generally available free of charge and without any restrictions on use. The changes concern survey data at the central, voivodeship and county levels. As a result, ten different databases are currently available for download as follows: (1) Numerical terrain model (Polish abbreviation: NMT) − central level; (2) Numerical coverage model (Polish abbreviation: NMPT) – central level; (3) LIDAR data – central level; (4) 3D Building Models – central level; (5) Orthophotomaps – central level; (6) Data of geodetic control networks – central and county level; (7) Database of topographic objects (BDOT10k) – central and voivodeship level; (8) Database of geographic objects – central level; (9) National registry of geographic names – central level; (10) National registry of boundaries – central level.

In order to facilitate free data sharing from a central resource, it is possible to download assets from the National Geoportal of Spatial Data Infrastructure (https://www.geoportal.gov.pl/). Data may be downloaded from the ‘Data download’ section, according to users’ needs without any restrictions (). The storing of downloadable data in one place makes the search for assets easy. There is no need to perform complex searches. Alongside the data download option, www.geoportal.gov.pl presents data in the form of information layers, which along with the dataset metadata gives users the opportunity to assess their usefulness.

Data download is quite simple. The user should enable the appropriate information layer and then click on the area of interest. In most cases, data is shared in areas defined by map sections in the 1992 coordinate system (EPSG:2180). There is also data available within the administrative boundaries of counties, such as BDOT10k or geodetic control networks.

3. Methods

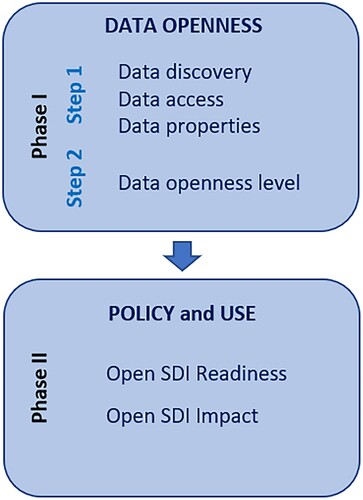

The approach presented in this study is focused on the three key SDI components, i.e.: (1) spatial data, web services and metadata; (2) procedures, policies, business context and objectives of organizations and investors of SDI; (3) users. Our method for assessing the openness of SDI () began with the analysis of open data (Phase I), available through main access points to the infrastructures. This phase was divided into two steps (Steps 1–2 in ). In the first one, three aspects of data were taken into account (column 1 in ), basing on categorization by Mulder, Wiersma, and Van Loenen (Citation2020). Data discovery focuses on the ease of finding the required data. The aspects of data access and download are covered by the Data access dimension. Finally, the Data properties category considers selected issues related to working with data. In this study measures associated with the presented dimensions (column 2 in ), as well as the scoring system was also adapted from Mulder, Wiersma, and Van Loenen (Citation2020). For five indicators (Ib.1, Ib.2, Ib.3, Ic.2 and Ic.3.), the scoring system included two values (no/yes), while for two others (Ic.4 and Ic.5) the value ‘partially’ was also used. For four indicators (Ia.1, Ia.2, Ib.4 and Ic.1), the scoring system included an optional description. Startpage.com was used as the search engine, in accordance with Mulder, Wiersma, and Van Loenen (Citation2020).

In the second step of the first phase (Phase I Step 2 in ) of the assessment proposal presented in this study, data openness level category was introduced, which concerns the open data deployment. In general, in the area of opening public repositories it is proposed (e.g. Open Data Maturity Report Citation2020; Resolution of the Council of Ministers, Citation2016, Citation2021) to consider the 5-star scheme for Open Data introduced by Berners-Lee (https://5stardata.info/en/) to rate the openness of datasets from a technical perspective. As these repositories in many cases are the source of data in the infrastructure it is essential to include these characteristics in the open SDI assessment approach. The scoring system (columns 1–2 in ) for the Data openness level category was adapted from Berners-Lee (https://5stardata.info/en/). The number of stars corresponds to data openness levels, and to reach the highest level, all lower levels’ conditions must be met. A dataset is labeled one star if it is available on the web with an open license and in any format (e.g. PDF); it is labeled two stars if it is additionally published as ‘machine-readable structured data’ (e.g. Excel). Three-star openness is reached if a dataset is also published in a non-proprietary open format (e.g. CSV). The four-star openness level requires the use of open standards from the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the Resource Description Framework (RDF), together with the SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) to identify things, while the highest level of openness is reached if the dataset is also linked to ‘other people’s data to provide context’.

In the second phase (Phase II in ) our approach focused on policies and goals, business context and objectives of organizations and investors, as well as users of the open SDI. The perspectives presented by Vancauwenberghe et al. (Citation2018), i.e. Readiness and Impact of Open SDI, with their assigned indicators (, columns 1–2), were employed. The Readiness dimension assesses the policies and strategy, as well as the extent to which non-government actors participate and contribute to developing the SDI towards openness. The Impact dimension focuses on the benefits and use of open data. Vancauwenberghe et al. (Citation2018) propose the low/medium/high scoring system without detailed description for all indicators of the Readiness dimension, and one indicator (Use) for the Impact dimension. In this study, the following scoring criteria interpretations for each indicator assessing SDI openness in low/medium/high scoring system were established (). In the open SDI assessment framework by Vancauwenberghe et al. (Citation2018) for the indicator Benefits (Impact category) two values are possible: ‘no/yes’. These values are also included in the method presented in this study.

Table 1. Scoring criteria for indicators assessing policy and use.

The PSDI and ten databases (see Section 2) available through the central access point of the PSDI (the PSDI geoportal) and managed by the national surveying service, were assessed according to the proposed openness assessment approach.

4. Results

4.1. Phase I: data openness

The results of Phase I Step 1 of the proposed openness assessment approach, i.e. the assessment of the openness of the 10 datasets described in Section 2, are provided in . The analysis of all three dimensions of openness (i.e. data discovery, access and properties) leads to the conclusion that the resources under investigation are characterized by a high level of openness.

Table 2. Phase I Step 1: data openness assessment in the PSDI.

All datasets were successfully discovered online within the first ten results of the search engine. There were references to the Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography web service, national geoportal, as well as Central Repository of Public Information in the search results. Details on how to download the data from the geoportal were presented in Section 3.1.

The procedure followed to access and download data through the national geoportal is similar for each dataset. It is possible to download the whole dataset through an application programming interface (API). Data is downloaded without any registration and free of charge. In Poland, no license is provided for data made available free of charge. The Act on Geodetic and Cartographic Law (Citation1989), however, specifies in Article 40c(3) that ‘entities that use the data shall include in their published studies information on the source of the material used’. Datasets are published not only in the national geoportal, but also in the Central Repository of Public Information. The available network services include discovery, view and download services. The desired level of database interoperability is achieved through the use of the recommended open formats and standards, and best practices.

Metadata is present for all the datasets and available in the Polish language. Metadata in the foreign languages are not available. The portal guide instructions and dataset names are also available in Polish. The metadata is documented in compliance with the ISO 19115 metadata standard.

The results of Phase I Step 2 of the assessment approach are provided in . Considering the five-star system, it should be noted that all analyzed datasets reached a 3-star level of openness. They are available on the web and published as machine-readable structured data. The datasets can be downloaded as GML files, while ESRI shapefile format is also provided. As for 3D-building data (dataset no. 4 in ), the CityGML format is used. The models achieve a level of detail (LOD) 1 and 2. Metadata are published in the XML and PDF formats.

4.2. Phase II: policy and use

presents the results of Phase II of PSDI openness evaluation.

Table 3. Phase I Step 2: openness level of the PSDI data available through the main access point.

As the strategy of opening spatial data in PSDI arises only indirectly from the relevant government document, the Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography introduced an amendment to the Geodetic and Cartographic Law (Citation1989) in terms of opening up the reference geospatial data required. The Act on Spatial Information Infrastructure (Citation2010) regulates the inclusion of resources from third parties, which must meet the criteria of the data included in the infrastructure. There is, however, little indication of non-government actors in decision making about the PSDI and data in the national geoportal. There are 11 public administration bodies responsible for PSDI implementation and development, as well as policy-making regarding open data. These two issues led to a ‘medium’ value as regards open spatial data vision and strategy, as well as open data policy (). ‘Low’ value was assigned to the Open decision making and Non-government data indicators, since there is little indication of non-government actors in decision-making about the PSDI and there are no examples of inclusion of spatial data provided by non-government bodies in the SDI in terms of open data policy and its characteristics in the national geoportal.

For the Use indicator, a High value was assigned. The development of both commercial and educational applications, geoportals and services is indicated, taking into account the second half of 2020. Some of these applications won the prize of the Surveyor General of Poland in a competition organized by the Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in December 2020 (https://www.geoportal.gov.pl/o-geoportalu/aktualnosci/-/asset_publisher/HCHq0YGNRszn/content/21-12-2020-rozstrzygamy-konkurs-na-najlepsze-wykorzystanie-danych-i-uslug-gugik-w-2020-r-). The Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography monitors the use of data and various initiatives related to open survey and cartography resources. In order to facilitate the use of data, some information and technology businesses offer QGIS plug-ins. The QGIS plug-in ‘Search for parcels’ (Polish abbreviation: ULDK GUGiK) is one such example, and allows to indicate the parameters of the parcels (e.g. province, county, municipality, parcel number), and then to download vector data with the basic attributes (https://gisplay.pl/gis/8067-qgis-wyszukiwarka-lpis-zastapiona-wtyczka-uldk-gugik.html). Another solution is the ‘GUGiK Data Downloader’ (https://www.envirosolutions.pl/gis-tools.html), which allows users to select data by pointing on the map or in reference to any vector data layer. Additionally, data could be filtered before downloading by type, resolution, source etc. Together with the downloaded datasets, a metadata CSV report is also available. Finally, a comprehensive package of procedures developed in R (https://gisplay.pl/dopobrania/rgugik_poradnik.htmlSite) exists, which may be used to download open survey data.

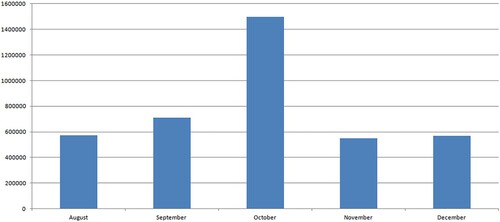

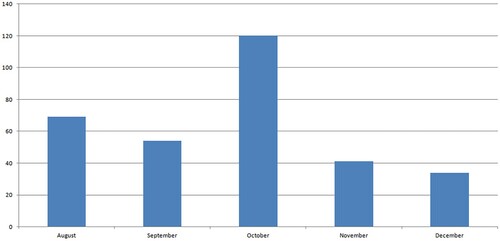

The value for the Use indicator was established based on the statistics of data downloads () during the August − December 2020 period. The total number of data downloads in the analyzed period amounted to 3,896,277. The highest number of downloads, as well as volume of data, were observed in October and amounted to 1,446,061 and 120 TB respectively. The lowest number of downloads was reported in November (553543), while the lowest download data volume was noted in December (35 TB).

Some benefits have been confirmed so far. From the perspective of survey and cartography services, fewer applications concerning data provision are processed; therefore, there is more time for other tasks. At a university level, open data extended both didactic and research activities. Some professions (e.g. urban planners) underline the benefits for their activities in decision-making processes, including faster access to information, and reduction in time needed to analyze and study data.

5. Discussion

The study concerns basic reference data in the PSDI, which is maintained by the Geodetic and Cartographic service. Pursuant to the Geodetic and Cartographic Law (Art. 40.1), the role of the State Geodetic and Cartographic Resource is to serve the national economy, state defense, public safety and order, science, culture, nature conservation, and the needs of citizens. The function of the Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in opening up the reference geospatial data is a milestone for the development of Polish geodesy and cartography, as well as PSDI. The assessment of data openness presented in this paper was based on ten databases, eight of which were made available as open data in September 2020.

The ‘Medium’ value for open data vision and policy indicators was established in this study in regard to geospatial government data, a strategy derived indirectly from documents relating to open public data. Regulation concerning the PSDI derives from the Act on Spatial Information Infrastructure (Citation2010), which is the transposition of the INSPIRE Directive (2007). The act defines, among others, the rules of technical openness, as well as access to spatial datasets and services, but it also describes the conditions and some limitations of their use. From the perspective of public authorities, this legislation was a very important step towards opening and sharing geospatial public data for the purpose of individual task realization that may have a direct or indirect impact on the environment. Considering non-governmental organizations (NGOs), research institutes and many professional groups, however, the Act did not cover all their needs. Legislation, rule implementation and technical guidelines for open geospatial data, understood as accessible to the widest possible range of users with the possibility to be used for any purpose, including business and non-commercial use, are scattered or non-existent, as a multitude of public administration authorities are responsible for opening geospatial data. Each acts within their competences with regard to data corresponding to the spatial data themes of SDI (Act on Spatial Information Infrastructure, Citation2010), which are made available through the main access point of the PSDI, as well as other spatial datasets. Due to the amendment to the Geodetic and Cartographic Law (Citation1989), survey and cartographic data have become generally available, free of charge and without any restrictions on use.

The availability of open geospatial data in the PSDI is the result of actions undertaken centrally. The Polish Ministry of Digital Affairs, based on numerous international initiatives and its experience in running the national public data portal (https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset), has prepared the Public Data Opening Program (Resolution of the Council of Ministers Citation2016; Resolution of the Council of Ministers Citation2021). This strategic document is primarily addressed to government administration bodies and their subordinate organizational units. Due to the interoperability of data opening, its use by other entities that create or store public data is also encouraged, especially local self-government units, non-governmental organizations and research institutes. The main aim of the Program is to improve the quality and increase the number of data available in the Central Repository of Public Information. The list of priority areas for opening public data starts with the spatial data under the jurisdiction of the Main Office of Geodesy and Cartography, and the environmental data under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment, the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management, the National Geological Institute, and the General Directorate for Environmental Protection (including climatic data, hydrological data, forms of nature protection etc.). Open spatial data are integrated on an ongoing basis within the repository of the National Spatial Data Infrastructure, which in turn is a component of the State Information Infrastructure and supports the development of an information society.

Open decision making in the case of the PSDI is still challenging, as there is no strongly developed governance structure through which different non-governmental actors are actively engaged. The Council for Spatial Information Infrastructure fulfills some tasks in this field. This is a body working alongside the ministry responsible for PSDI, which is composed of representatives from national administrations, local and regional government representatives, as well as academic experts. The Council is not represented directly by the private sector or NGOs, and its governance structure, including different stakeholders interested in the development of the PSDI, limits potential broader activity in joint decision making. Taking into account the results of the analysis of the EU28 Member States and Norway presented in a report by Barbero et al. (Citation2019), considering a continuum from no engagement (which is still the case in a minority of countries) to full decision-making power (which is still rare), the Polish approach falls in between these two extremes.

The main access point of the PSDI consists of several dedicated geoportals. The ‘INSPIRE’ geoportal is developed in accordance with the implementation rules and specifications of INSPIRE. The national access point implements the solutions, which support the opening of spatial data to different groups of stakeholders, as well as allowing the integration of users’ feedback and preferences better in the way geospatial data are made available. As for the amount of downloaded data, judging from the ten databases under consideration in this study, in relation to the size of the entire resource, this reached 28%, 22%, 50%, 17% and 14% in the months of August, September, October, November and December 2020 respectively. It should be remembered, however, that these were the first months these ten high-impact databases were made available, and efforts to increase the share of users are in progress.

The proposed assessment approach adopted several criteria and indicators from the existing openness assessment frameworks with the following intentions. First of all, our intention was to collate a profound, multi-dimensional evaluation, and the mixture of the three assessment frameworks, excluding unnecessary overlaps, provided this opportunity. Secondly, we sought to establish continuity by referring the assessment results to previous ones. In using these methodologies, however, we have identified weaker points and proposed some improvements. The indicator ‘metadata’, according to Mulder, Wiersma, and Van Loenen (Citation2020) denotes that metadata are documented in compliance with the ISO 19115 standard, while the ‘multilingual metadata’ indicator points to availability in both Polish and English versions. In the opinion of the authors of this study, the availability of metadata in English or other foreign languages should be an additional indicator, as the occurrence of metadata in the national language (the proposed indicator ‘metadata’) is a very important property of open data itself, which may be assessed in compliance with the ISO 19115 standard (the proposed indicator name ‘metadata standard’). The benchmark to determine the ‘low, medium, high’ values used by Vancauwenberghe et al. (Citation2018) was not expressed clearly; therefore, the assessment results presented in (column 3) are based on scoring criteria for indicators assessing SDI openness (), which were developed in this study. The proposals for five indicators IIa.1–IIa.4 and IIb.1 () were referenced to the analytical framework of the SDI in the digital government transformation assessment (Barbero et al. Citation2019) and Open Data Barometer (Citation2017).

Table 4. Phase II: policy and use.

In regard to thematic geoportals managed by central institutions, some attempts to implement the four-star level of spatial data openness are noticeable. These efforts concern metadata, created for reference spatial objects using HTML and RDF, that conform to the GeoDCAT-AP profile (https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/ge.58/2017/mtg3/2017-UNECE-topic-i-EC-GeoDCAT-ap-paper.pdf). Taking into account all the OGDs available in the open data repository, there are 11 resources that have reached the four-star level of data openness.

The actions taken to open survey and cartographic data have already made it much easier to access this type of data. Data sales generated little revenue, which by far exceeded the costs necessary to support the sales and data management process. The term impact involves, on the one hand, determining the use of data according to the amount of data retrieved, and, on the other hand, identifying the benefits, as well as attempting to quantify them. Indirect benefits for the economy and administration as a whole are assumed, resulting from easy access and the potential for extensive use of spatial data. This should translate into technological development and an increase in society’s digital competences. In addition to financial issues, the following intangible benefits are an extremely important effect of data release: increasing the innovativeness of private sector companies, meeting public expectations for the release of public data, and increasing the role of research carried out by the education sector using spatial data. The latter could in turn lead to popularization of the research outcomes based on open spatial data. While considering FAIR Principles (Wilkinson Citation2016) they could contribute to the infrastructure supporting the reuse of scholarly data.

6. Conclusions

The paper proposed the SDI openness assessment approach based on existing openness assessment frameworks, to describe the actual state of geospatial reference data openness in Poland in the context of the Polish strategy for open public data since 2016. The results indicated that ten geodetic and cartographic databases fulfilled ten out of eleven criteria of data openness, according to the methodological assumptions, and reached a 3-star level of openness. In terms of PSDI openness, the participation of non-governmental actors and their datasets is challenging. There is need for further development of the PSDI towards sharing public administration data that meet the open data criteria, thus contributing to the openness of the PSDI.

The described case study complements SDI practices with the open geospatial data assessment approach, as well as considerations of open SDI readiness and impact. The assessment methodology developed in this study consists of two phases that allow for the analysis of both data and selected aspects of an open SDI. The recently published Open SDI assessment frameworks by Mulder, Wiersma, and Van Loenen (Citation2020) and Vancauwenberghe et al. (Citation2018) highlight many aspects and characteristics of open geospatial data, which can be grouped into the following categories: data discovery, data access and data characteristics. The presented assessment approach integrates one more category, namely data openness, which refers to the technical component of data openness, and follows the 5-star deployment scheme for Open Data. This allows to perceive the issue of open spatial data in the broader context of technological advances, thus indicating opportunities for the development of Open SDIs. Our contribution also concerns scoring benchmarking for assessing SDI openness. The proposed framework may be used for comparative analysis of SDI openness in different countries, including EU Member States that draw on the experience of the implementation of the INSPIRE Directive.

The strategy of opening up public data in Poland should be connected with promoting solutions, which could be used in practice in many different sectors and services. The Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography has published a document presenting the current state of spatial data and services availability in the PSDI with guidelines on the technical requirements and tutorials on the use of the resources (http://www.gugik.gov.pl/pzgik/podstawowe-uslugi-danych-przestrzennych).

It is also proposed to provide additional incentives to increase the participation of non-governmental actors in decision making on the PSDI in the open data strategy, as well as the coordination of strategy and policy activities in relation to geospatial data at the central level of public administration. The establishment of a consultative group integrating non-public stakeholders interested in the development of the PSDI could also be considered. Another issue is the improvement of accessibility and presentation of spatial data in the Central Repository of Public Information. It is also recommended to improve the Polish standards (https://dane.gov.pl/media/ckeditor/2020/06/16/standard-techniczny.pdf) describing the minimum technical requirements for open public data, and to include criteria specified for spatial information. It should be emphasized, however, that the level of data openness in the spatial data infrastructure, when referenced to the 5-star open data model, depends on the technical profile of the infrastructure. The SDI development towards solutions based on the semantic web with the extensive development of proper spatial information standards (e.g. Wiemann and Bernard Citation2016; Ronzhin et al. Citation2019; Jiang et al. Citation2020) could allow for achieving higher levels of data openness (i.e. use of URL and linking data) in relation to the level considered in this study (open, machine-readable format and available on the web) and, eventually, a higher level of SDI openness.

The assessment approach developed in this study focuses mainly on legal and technical dimensions. There is need to address more perspectives, such as institutional, financial and ethical ones. The overview of institutional arrangements is a proposal to fill these gaps at least in part. Although the Polish SDI reached the milestone of opening up geospatial data, there is still room for further studies on its benefits and the issue of re-use for example.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Act of the 17th of May 1989 on Geodetic and Cartographic Law. 1989. Journal of Law, No 30, entry 163. Warsaw: Government Legislation Centre. (in Polish).

- Act of the 4th of March 2010 on Spatial Information Infrastructure. 2010. Journal of Law, No76, entry 469. Warsaw: Government Legislation Centre. (in Polish).

- Barbero, M., M. Lopez Potes, G. Vancauwenberghe, D. Vandenbroucke, and V. Nunes de Lima, ed. 2019. The Role of Spatial Data Infrastructures in the Digital Government Transformation of Public Administrations. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-76-09679-5, https://doi.org/10.2760/324167, JRC117724.

- Crompvoets, J., A. Rajabifard, B. van Loenen, and T. Delgado Fernandez. 2008. A Multi-View Framework to Assess Spatial Data Infrastructures. Melbourne: Digital Print Centre, The University of Melbourne.

- Diaz, P., and J. Maso. 2014. “Social Networks and Internet Communities in the Field of Geographic Information and Their Role in Open Data Government Initiatives.” In: Frameworks of IT Prosumption for Business Development. ISBN13: 9781466643130. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-4313-0.ch018.

- Directive (EU). 2019. “2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information, Official Journal of the European Union, L 172/56.” Accessed December 18, 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1561563110433&uri=CELEX:32019L 1024.

- Dulong de Rosnay, M., and K. Janssen. 2014. “Legal and Institutional Challenges for Opening Data Across Public Sectors: Towards Common Policy Solutions.” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 9 (3): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762014000300002.

- European Data Portal. 2018. “Open Data Goldbook for Data Managers and Data Holders Practical Guidebook for Organisations Wanting to Publish Open Data.” Accessed December 14, 2020. https://www.europeandataportal.eu/sites/default/files/european_data_portal_-_open_data_goldbook.pdf.

- European Data Portal. 2019. “Open Data Maturity.” Report 2019. Accessed December 27, 2020. https://www.europeandataportal.eu/sites/default/files/open_data_maturity_report_2019.pdf.

- Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115–435; 2019.

- Gil, J., L. Diaz, C. Granell Canut, and J. Huerta. 2012. “Open Source Based Deployment of Environmental Data Into Geospatial Information Infrastructures.” International Journal of Applied Geospatial Research 3 (2): 6–23.

- Imran, M. 2019. “Enabling Crowdsourcing in the Framework of User-centered SDIs for Information Management of Geographical Volunteer Content.” 5th International Conference on Information Management (ICIM), Cambridge, England, 24–27 March, 2019. 5TH International Conference on Information Management (ICIM 2019), 7–12.

- Inkpen, R., R. Gauci, and A. Gibson. 2020. “The Values of Open Data.” Area 53 (2): 240–246. doi:10.1111/area.12682.

- Izdebski, W. 2020. Spatial Data Infrastructure in Poland [Polish Spatial Data Infrastructure]. Warszawa: Geo-System Sp. z o.o. ISBN: 978-83-943086-4-3. (in Polish).

- Izdebski, W., and A. Seremet. 2020. “Practical Aspects of Spatial Data Infrastructure in Poland (in Polish).” Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography. ISBN 978-83-254-2583-8, Warszawa.

- Jiang, H., J. van Genderen, P. Paolo Mazzetti, Hyeongmo KooH, and Min Chen M. 2020. “Current Status and Future Directions of Geoportals.” International Journal of Digital Earth 13 (10): 1093–1114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2019.1603331.

- Masser, I. 2005. GIS Worlds: Creating Spatial Data Infrastructures. Redlands, CA: ESRI Press.

- Mulder, A. E., G. Wiersma, and B. Van Loenen. 2020. “Status of National Open Spatial Data Infrastructures: A Comparison Across Continents.” International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructure Research 15: 56–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.2902/1725-0463.2020.15.art3.

- Nebert, D. 2004. “The SDI Cookbook.” http://gsdiassociation.org/images/publications/cookbooks/SDI_Cookbook_GSDI_2004_ver2.pdf.

- Open Data Barometer. 2017. “Research Handbook – v1.0.” Accessed May 26, 2021. http://opendatabarometer.org/doc/leadersEdition/ODB-leadersEdition-ResearchHandbook.pdf.

- Open Data Inventory. 2021. “(ODIN 2020/21) Executive Summary.” Accessed May 26, 2021. https://odin.opendatawatch.com/Downloads/otherFiles/ODIN-2020-ExecutiveSummary.pdf.

- Open Data Maturity Report. 2020. Publications Office of the European Union ISSN: 2600-0512. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2830/619187. https://data.europa.eu/sites/default/files/edp_landscaping_insight_report_n6_2020.pdf.

- Pasquetto, I., A. Sands, and Ch Borgman. 2015. “Exploring Openness in Data and Science: What is ‘Open’, to Whom, When, and why?” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 52 (1): 1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2015.1450520100141.

- Resolution of the Council of Ministers. 2016. “Program of opening public data (in Polish).” https://mc.bip.gov.pl/programy-realizowane-w-mc/programu-otwierania-danych-publicznych.html.

- Resolution of the Council of Ministers. 2021. “Program of opening public data (in Polish).” https://monitorpolski.gov.pl/M2021000029001.pdf.

- Ronzhin, S., E. Folmer, R. Mellum, T. E. von Brasch, E. Martin, E. L. Romero, S. Kytö, E. Hietanen, and P. Latvala. 2019. “Next Generation of Spatial Data Infrastructure: Lessons from Linked Data implementations Across Europe.” International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research 14: 83–107.

- Vancauwenberghe, G., K. Valečkaitė, B. van Loenen, and F. W. Donker. 2018. “Assessing the Openness of Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDI): Towards a Map of Open SDI.” International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructure Research 13: 88–100.

- Vancauwenberghe, G., and B. van Loenen. 2018. “Exploring the Emergence of Open Spatial Data Infrastructures: Analysis of Recent Developments and Trends in Europe.” In User Centric E-Government. Integrated Series in Information Systems, edited by S. Saeed, T. Ramayah, and Z. Mahmood, 23–45. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59442-2_2.

- Weerakkody, V., Z. Irani, K. Kapoor, U. Sivarajah, and Y. K. Dwivedi. 2017. “Open Data and its Usability: An Empirical View from the Citizen’s Perspective.” Information System Frontiers 19: 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-016-9679-1.

- Wiemann, S., and L. Bernard. 2016. “Spatial Data Fusion in Spatial Data Infrastructures Using Linked Data.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 30 (4): 613–636.

- Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, et al. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship.” Scientific Data 3: 160018. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18.

- Zuiderwijk, A., M. Janssen, and C. Davis. 2014. “Innovation with Open Data: Essential Elements of Open Data Ecosystems.” Information Polity 19 (1, 2): 17–33.

- Zwirowicz-Rutkowska, A., and A. Michalik. 2016. “The Use of Spatial Data Infrastructure in Environmental Management:an Example from the Spatial Planning Practice in Poland.” Environmental Management 58: 619–635. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0732-0.