ABSTRACT

Intelligence agencies play a prominent role in the production of knowledge about national security threats and their evaluation. This function is not just a value-neutral technical activity, but a social and political action. The purpose of this article is to explore the ways in which the Slovak Information Service, an intelligence agency responsible for the protection of national security, discursively constructs security threats and assigns enemy images to specific actors. The analysis was conducted on the publicly available parts of the agency’s Annual Reports. It utilised qualitative document analysis, supplemented by quantitative analysis of the frequency of use of specific keywords. The analysis, which identified the main threats connected to internal security, is constructed in a manner which connects terrorism with migration and the Muslim faith, assigning terror identities to specific groups. The agency’s constructions of internal threats were also utilised in the political discourse. Moreover, securitisation rhetoric was used in connection to the movements promoting human rights and fighting fascism, labelling them as left-wing extremists. In the field of foreign threats, their construction depends on both international developments and domestic political dynamics.

Introduction

The past few years have resulted in the rising prominence of a multiplicity of national security threats from both state and non-state actors, including a rise in the terrorist threat after the 2015 and 2016 attacks, the migration and refugee crisis and an increasing spread of disinformation following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. All these threats have come to the forefront of public discourse in Central and Eastern European countries, including Slovakia. One of the actors entering this debate was intelligence agencies, which are the primary organisations responsible for the collection of information on and the evaluation of threats.

Gill and Phythian (Citation2016, 8) argue that various processes of intelligence cannot be considered merely technical and value-neutral actions, since they are inherently social and political activities. Through intelligence work, intelligence agencies produce, give meaning to, and hierarchise, threats and enemy images. These images of the enemy are based on the reality of threats through the analysis of real events, such as terrorist attacks. However, around these real events, images are created that can substantially exaggerate the real danger (Mathiesen Citation2013, 61–63).

In this regard, these images form an official narrative on the imminence and magnitude of threats in individual countries, or on the broader supranational level. Intelligence products concerning these narratives serve as a basis for policy making. Pili (Citation2019) considers intelligence agencies as social epistemic institutions, “organisations with the goal of providing knowledge and foreknowledge of an enemy’s intentions and behaviour to the decision maker.” However, this knowledge is limited by a number of factors, including time and resources, as well as by the focus of intelligence gathering. What is considered a threat is therefore formulated and re-formulated not only by the intelligence agency, but also by the political elite who task the agency.

The Slovak Information Service (Slovenská informačná služba, SIS) is the agency responsible for the protection of national security and the aversion of security threats against the Slovak Republic. For a relatively long time, its functioning was shrouded in overt secrecy. This is because between 2005 and 2011 it did not publicly release any official documents, including Annual Reports. Since 2011, eight Reports of the agency have been made publicly available, providing an opportunity to gain insight into the agency’s activities in relation to a myriad of threats, as well as the language it uses to construct these threats.

The methods of constructing national security threats, either as a result of domestic developments or in the light of international threats, such as terrorism, the migration crisis, digital propaganda and Crimean aggression, remain largely unexplored topics in the case of the Slovak Republic. At the same time, these constructions form a political, as well as a broader social discourse on individual threats and set the agenda for taking political decisions in the area of national and European security. The purpose of this article is to explore the discursive construction of threats to national security, to identify their hierarchy, language, development over time in the official Annual Reports of the SIS, and to place them in a broader political and social context.

Intelligence and contemporary threats to national security

Any state has both the right and the duty to protect its citizens. Intelligence is a means towards the provision of security. It is comprised of “mainly secret activities – targeting, collection, analysis, dissemination and action – intended to enhance security and/or maintain power relative to competitors by forewarning threats and opportunities” (Gill and Phythian Citation2018, 5). By their nature as forward-looking enterprises, the activities of intelligence agencies should lead to the ability of the identification of relevant risks and threats and their neutralisation before they occur or escalate within the boundaries of the state.

The proper functioning of intelligence services is therefore essential for the maintenance of security in any society. At the same time, the conduct of democratic intelligence services is subject to more thorough forms of oversight, since democratic demands require that their activities be legitimate and operate within democratic standards and rules (Caparini Citation2007, 4). Intelligence activities must therefore be carried out within certain limits, which take into account the individual rights and freedoms of citizens and balance these with the right to security. This requires their functioning under a clearly defined legal mandate (Gill Citation1994, 64–65) which also defines the extent of the focus on individual threats.

A complete state of security is never possible, and every state needs to attempt to allocate its resources in the most efficient way. Intelligence assists in the mitigation of security risks and uncertainties. Phythian (Citation2012, 192–196) identified an important distinction between uncertainty, risk and threat. Risk can be defined as a measurable uncertainty, something quantifiable. On the other hand, uncertainty remains unmeasurable, due to a lack of information and knowledge. The process of knowledge accumulation and the understanding of a risk leads to the formulation of a threat, which can be defined as a sufficiently imminent risk. The successful process of intelligence gathering and analysis transforms uncertainty into risk, and subsequently into a concrete threat. In this sense, the process of intelligence can be understood as risk shifting. It assists a state to “shift uncertainty into risk, to assess and manage probabilities, and to mitigate hazards” (Warner Citation2009, 22).

The changing landscape of the security environment in past years has led to the ever-rising prominence of intelligence. The nature of risks and threats has shifted from a monolithic single adversary to a multiplicity of threats. These include terrorism, border security and immigration issues, natural threats, transnational crime and cyber security (Jensen, McElreath, and Graves Citation2018). The national security environment has become more complex and uncertain, with the increasing prominence of non-state actors and asymmetric threats that have the power and capacity to disrupt national security (Quiggin Citation2007, 14–17).

The changes in the focus of intelligence react to wider societal changes and demands of citizens for security. Acharya (Citation2014) argues that the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which represent a milestone in the emergence of asymmetrical non-state actor threats to national security, created an “age of fear.” This means that the fear of terrorism created a climate of fear, heightened not only by the attacks, but also by the government discussions of this threat which eliminated almost all discourse on other threats. A major portion of the resources of intelligence agencies have therefore been assigned to counterterrorism.

The overt focus of intelligence on some specific, highly visible and publicised risks and threats is a result of its adaptation to the “post-normal age,” in which the attainment of the whole truth is impossible and is replaced by competing narratives of events. Policy makers expect intelligence agencies to produce the specific knowledge to support the narratives used by decision makers (Palacios Citation2018, 188–189). Consequently, intelligence agencies do not merely objectively describe reality, but, for a range of reasons – be it limitations in data collection as well as specific aims of intelligence products – participate in the creation and reproduction of a social reality (Fry and Hochstein Citation1993). Moreover, the formulation of concrete threats is not just a result of intelligence work, but is a political activity, distorted by ideological bias (Jackson Citation2010, 458–459). The processes of the identification and management of threats therefore need to be understood within these processes.

Construction of threats and its effects

The construction of threats is not a value-neutral activity. This attribute is also translated into policy briefs and public documents presented by intelligence services. What is important is the language adopted and labels used to identify threats. The most prominent case in recent years is the fight against terrorism.Footnote1 The language of terrorism and the fight against terrorism has a performative character, shaping the perception of threats to national security. These perceptions are then transferred to the adoption of specific measures, which subsequently have real and often serious consequences for security policy or specific communities (Demirsu Citation2017, 4).

Wolfendale (Citation2006) argues that counterterrorism and its rhetoric can add to the spread of fear and anxiety by exaggeration of the terrorist threat and scaring the public by means of public statements and recurrent reminders of the terrorist threat . One of the tangible effects is the invention and subsequent attribution of terror identities to specific groups or communities (Monaghan and Walby Citation2012, 141–146), which are hence stigmatised in public discourse, and possibly placed under greater surveillance by state security forces.

In recent years, the effect of the terrorist or Islamist label on the perceptions of violent acts and the support for specific policies was tested experimentally, confirming that these labels and categorisations lead to an increased perception of threats. Research by Woods (Citation2011), which tested the attachment of three different categorisations of a news story describing an act of violence, showed that the mere labelling of the act as “terrorism” does not increase the perceived threat. However, the addition of a nuclear attack or radical Islam label results in elevated threat perceptions.

An experiment by Baele and others conducted a similar vignette-based experiment, where they attached labels (“terrorist”, “Islamist” or no label) to a news story including an act of violence. Their findings showed that the addition of terrorist or Islamist labels leads to a different perception of the perpetrator of violence – they are associated with traits such as irrational, ideological and immoral. Moreover, participants exposed to the terrorist and Islamist labels were more willing to advocate hardline policy preferences and harsher prison sentences for the perpetrators (Baele et al. Citation2019).

These experimental findings confirm that the language of terrorism has a performative character, leading to an increased threat perception and a willingness to accept harsher security policies by the state. The above-mentioned experiments investigated media categorisations, but I believe that the same principle can be applied to the products of intelligence agencies. The latter are the main authority and principle producers of knowledge about terrorism and the magnitude of its threat. Moreover, publicly available reports are often cited and serve as a basis for public discussions on these issues. How intelligence agencies construct threats is therefore important not only for its impact on policy making, but also on public perceptions and reactions.

The combination of a structural aspect and the constructed aspects of threats creates a threat infrastructure, forming the basis for the politics of insecurity (Béland Citation2007). On the structural level, the politics of insecurity are manifested in the negative perceptions of out-groups (e.g. migrants, minorities) by individuals with heightened fear dispositions. They perceive the out-groups as a threat, which is demonstrated in political support for punitive policies against out-groups, such as support for stricter migration legislation (Hatemi et al. Citation2013).

Another structural change in the threat infrastructure is a significant shift in the security landscape in a specific country, such as a terrorist attack. Such a shift affects the prioritisation of the perceived competence of political actors in addressing security concerns and leads to greater political support for those actors (Aytac and Carkoglu Citation2019). Therefore, political actors can affect the constructed aspect of a threat infrastructure, taking a proactive approach, heightening the specific threats and using the strategy of moral framing (Spielvogel Citation2005) to present themselves as guardians of security, culture and morality against threats of terrorism and migration.

Another area in which the politics of insecurity are utilised is the enforcement of controversial legislation. The 2015 and 2016 terrorist attacks in Europe served as grounds for the extension of intelligence competences, including several technological surveillance capabilities to detect possible threats (Bozinovic Citation2017; Woods Citation2017). Efforts to extend the powers of intelligence agencies came as a result of the discussion of the existing threats and their relevance, particularly in the context of the increasing threat of terrorism. Thus, the extension of competences in the field of security and surveillance came under certain discursive legitimisation strategies for threats (Bogain Citation2017). These discursive strategies construct specific threats or enemy images that change over time.

Methodology

The research presented in this article is an explorative case study of the language of the construction of threats by the Slovak intelligence agency. It is based on both a qualitative and quantitative analysis of official publicly available Annual Reports of the civilian agency Slovak Information Service from 2011 until 2018. This range is limited by the availability of the reports, since reports before 2011 are not publicly available. Every year, SIS prepares an Annual Report of its activities, which is then discussed in a classified manner in Parliament. Unclassified parts of the Reports are then made available to the public.Footnote2 These include an overview of activities and the results of the annual work of the agency, as well as information about personnel, budget and cooperation with other institutions.

The study of intelligence is often limited, due to the secret nature of intelligence work and the possibilities of access to relevant sources (Warner Citation2007). The official documents are the most readily available sources for a study. For the purposes of my research, this represents the strength of this data source, since their public availability also means their public visibility. The way in which threats are constructed in these Annual Reports therefore has the most prominence in public discourse.

The analysis of documents is a relevant method of research, since official documents produced by organisations can be considered as “social facts,” despite their inherent limitation of not being a description of the social world they represent. These are texts that use specific language in order to persuade readers. In this sense, they construct their own social reality (Atkinson and Coffey Citation2004).

Qualitative document analysis (QDA) is the qualitative method utilised for the analysis. QDA is a method that is characterised by its relative flexibility when it comes to coding and its focus on the construction, management and packaging of discourse to the audience. It follows “certain issues, words, themes and frames over a period of time” and attempts to uncover “relevant social activities, identities, meanings and relationships” to study trends in communication patterns and discourse utilised by the creators of the document (Altheide et al. Citation2008). For these reasons, it is an appropriate methodological choice for tracking the methods in which threats were constructed over time.

The analysis was conducted in Atlas.ti software. The qualitative analysis was approached inductively, coding all the relevant threats and actors associated with these threats. For internal threats, the specific codes were associated specifically with the themes of terrorism, migration and extremism. Associated with foreign threats were the threats of infiltration, cyber threats and hybrid threats. The analysis entailed the uncovering of patterns within individual themes, as well as the discussion of connections between specific themes.

The qualitative analysis was supplemented by a quantitative examination of the frequency of usage of the specific keywords used to label individual threats. For this purpose, the Word Cruncher function was used. The quantitative analysis serves for the purpose of evaluation of the development of threats, as well as the emphasis placed on them over time. This analysis functioned with specific keywords and their variations used in the analysed documents – both adjectives and nouns and their variations, based on grammatical gender and grammatical case in the Slovak language.Footnote3 This quantitative analysis worked with the assumption that a larger number of mentions of a specific threat indicated its larger significance at that time.

Construction of threats in intelligence documents

The analysis presented here explores the construction of the most prominent threats to national security identified by the Slovak Information Service and associated actors who are carriers of these threats, as well as the processes of the attribution of the characteristics of threats to specific individuals or groups. National security no longer merely refers to protection from external military threats, but entails a plethora of direct and indirect threats, both actor-based and structural, foreign and domestic. Moreover, the threats are not universal, they are country- specific (Caudle Citation2009). In the following analysis, I focus on the threats which were discussed in more than a general manner in the Annual Reports and which identify specific groups of actors presenting the threat. They may be divided into two categories – internal and foreign threats. In the area of internal threats, I present the threat of terrorism and migration, followed by extremism.

Terrorism and migration threats

The threat of terrorism remains one of the most prominent threats in all the Annual Reports. Between 2011 and 2015, the SIS did not identify any imminent threat of terrorism in Slovakia.Footnote4 Between 2016 and 2018, the situation concerning the threat of terrorism was evaluated as relatively calm or stable. Despite this evaluation and the lack of the presence of terrorist attacks within the country,Footnote5 evaluations of a potential terrorist by the intelligence agency attached “terror identities” to certain groups.

Already in 2011, the agency identified a growing threat of terrorism within the European territory related to the “individual Jihad,” reinforced by supportive statements by influential Islamic clerics and “aggressive Internet propaganda” (Report Citation2011). In 2017, the potential of a terrorist threat was also identified in Slovakia in connection with Jihadism and completed or thwarted terrorist attacks conducted within the European Union in past years.

The connection of Jihadism was linked, even though not explicitly, to the local Muslim community within the country. It needs to be stressed that the Slovak Muslim community is very small, estimated at between 4,800 to 5,000 individuals, and publicly invisible (Lenč Citation2019). In general, the intelligence agency considered the local Muslim community as moderate. Despite this, the 2018 Report attached a certain amount of risk to it:

The Muslim community in Slovakia did not publicly react to the events associated with terrorist attacks with an Islamist background. No open spreading of Jihadist content or sympathies for Jihadist organizations were noticed. However, the activities of a few individuals on social media websites were identified as potentially threat-posing (Report Citation2018).

The Report does not demonise the community as a whole. Nevertheless, the mere link to terrorism through the inability to condemn it, coupled with suspicious activities of a few individuals, constructs a category of mistrust, which feeds into and perpetuates wider ideas about Muslims as a suspect community (see e.g. Pantazis and Pemberton Citation2009) within the societal and political context in which Islam is perceived mostly negatively (Lenč Citation2017). The language falls within the paradigm of growing expectations of Muslims for specific political performance (such as very loud condemnation of terrorism), in order to be considered “good Muslims” (Breen-Smyth Citation2014, 237). Inability to meet these demands leads to relegation into the suspect category. Therefore, despite the seemingly mild language of the Report, it singles out individuals belonging to the Muslim community as a potential risk who need to be monitored.

The second identified group that poses a security threat was migrants. The focus on what the intelligence agency labelled as “illegal migration” underwent a significant shift in 2014. Until then, the focus had been mostly on the Schengen border with Ukraine, which was an entry point for migrants on their way to the European Union. The thrust on the eastern border intensified in 2014, after the escalation of the Ukraine-Russia conflict. The paradigm changed with the eruption of the migration and refugee crisis in 2015. Even though Slovakia was barely affected by it,Footnote6 the intelligence service considered illegal migration as one of the most prominent threats:

When monitoring illegal migration in 2015, the service focused on assessing security risks related to illegal migrants coming to the EU, primary risks of potential infiltration of people sympathising with radical and terrorist Islamist organisations into the migration wave, veterans from conflict zones and people who might have committed crimes against humanity in these zones (Report Citation2015).

The above-mentioned practice creates two major problems. Firstly, there is the label of “illegal migration.” The distinction between migrants and refugees or asylum seekers is not only a linguistic one, but also carries significant political implications. Refugees/asylum seekers are granted legal rights under International Law. Moreover, adding the adjective “illegal” to the migration is a securitisation practice that exacerbates migrant-as-a-threat discourse, leading to the heightened refusal of migration and resulting in restrictive immigration practices (Ibrahim Citation2005).

The second problem is the clear association of migrants with terrorism. The migration and refugee crisis re-focused some of the activities of the intelligence service on the evaluation of “security risks related to illegal migrants” (Report Citation2015). The primary threat posed by these migrants was the risk of infiltration by sympathisers with radical and terrorist Islamist organisations. Therefore, not all migrants or refugees were considered as terrorists, but there was a risk of infiltration by a terrorist, or radicalisation of migrants during their movement to Europe. The agency warned that some of the refugee camps on the way have “appropriate conditions for spreading radical Islam” (Report Citation2018).

The association of migrants with terrorists is a result of the refugee crisis being immediately followed by the terrorist crisis of the Paris attacks in November 2015. Nail considers this as politically charged terminology, resulting in the language of a “new hybrid warfare of migration” which leads to the securitisation of borders and a political turn towards nationalism (Nail Citation2016). Because of the connection to terrorism, illegal migrants are not refugees, but rather a security threat to be dealt with and unworthy of the assistance of the Slovak state, or of other European states.

It is important to note that when SIS discusses the threat of illegal migration, it moves the threat to the level of the European Union as a whole. Due to the limited number of refugees and migrants entering Slovakia, the threat could not be credibly constructed in relation to domestic developments. This illustrates the point of over-exaggeration of the threat in the Slovak discourse.

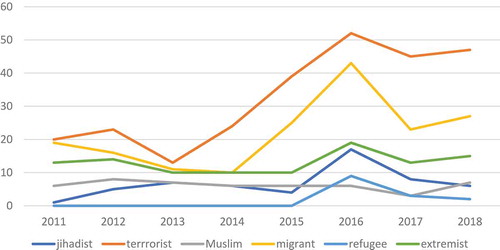

The prominence of the above-discussed threats has changed over time. This can be illustrated by the number of mentions of specific words associated with individual threats in the Annual Reports. As can be seen from below, some of the threats remain relatively stable (extremism, Islam) and others gain prominence over time (terrorism, migration).

Both terrorist and migration threats peaked at the height of the migration and refuge crisis in Europe in 2016, declining afterwards but remaining the most overriding threat. The pairing of these two threats is a result of the language of the documents that linked them. Moreover, the label “refugee” was almost non-existent, first being mentioned in 2016. The labelling of asylum seekers as “migrants”, not refugees, facilitated the securitisation approach towards them.

Despite the focus on the relationship between terrorism and migration, the actual connection of Slovakia to the terrorist attacks carried out in Europe was established through the trafficking of easy-to-reactivate firearms to criminals and terrorists in Belgium (Duquet and Goris Citation2018) and France (Florquin and Desmarais Citation2018). The threat of blank-firing weapons (or expansion weapons) was first identified by the SIS only in 2015, after the medialisation of the use of the weapons bought via a Slovak store in the Charlie Hebdo shooting and Paris terrorist attacks:

SIS collected and evaluated information about the so-called expansion firearms, modified from live firearms with reactivation potential. This risk was identified in 2014. At the beginning of 2015, a valid legislation in the Slovak Republic enabled deactivation of firearms allowing subsequent reactivation. Since more EU countries had stricter legislation at that time, foreigners started buying expansion weapons in Slovakia on a large scale (Report Citation2015).

The controversy over the sale of these weapons and the documentation of their ties to terrorist attacks led to the Amendment of the Law on Firearms and Ammunition in 2015, requiring stricter evidence of these weapons and a ban on their sale over the Internet. This helped to mitigate this immediate threat. Nevertheless, monitoring by the intelligence agency of the sales of blank-firing weapons also continued in subsequent years, as remaining a possible security threat. The case of blank-firing weapons shows that overemphasis on one group of threats relating to the struggle against terrorism, i.e. migration and Islam in the Slovak case, can lead to under-emphasis of other domestic threats which can prove to be more immediate and also easier to neutralise.

Extremism

Another global development in past years has been the rise of political extremism. It is an issue that has been of interest to the Slovak Information Service for the past decade. In this section, I focus firstly on right-wing and then on left-wing extremism, as seen through the lenses of the intelligence agency.

The threat of right-wing extremism underwent several changes. Until 2013, the threat of right-wing extremism in Slovakia was represented primarily by unofficial groups outside of the political party spectrum (Nociar Citation2012). The year 2013 was a landmark year, due to the success of extremist political forces in institutionalised politics, with the victory of Marian Kotleba in the post of Governor of the Banská Bystrica Region. This was followed by the entrance to Parliament in 2016 of the right extremist party Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia (Kotleba – Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko, K-LSNS).

This shift in the nature of the right-wing extremist threat was reflected by the intelligence agency. The period of the prominence of unofficial groups was characterised by street violence, football hooliganism and participation in protests. According to the SIS, these activities had been on the decline at the beginning of the 2010s. Instead of that, the new aim of the extremist forces was identified in 2011 as an attempt to establish themselves within the political scene through the presentation of issues related to “difficult co-existence of the majority population with the Roma community, social issues and criticism of the state authorities” (Report Citation2011). The largest threat of the attainment of political function would be to “provide ground for extremist ideology” (Report Citation2013).

A major change in the focus of right-wing extremism came about with the migration and refugee crisis, after they shifted their rhetoric on the

anti-migration and anti-Islamic attitudes and fight against multiculturalism more intensively. EU and NATO criticism became one of the main topics. The traditional XRW [right-wing extremism] topic – anti-Roma rhetoric – became secondary (Report Citation2015).

The campaign of extremists moved into the online sphere, which, according to SIS, increased the risk of strengthening the position of right-wing extremist political parties. The response of the state to the activities of right-wing extremists, both online and offline, was only limited, allowing them to keep increasing their public visibility (Vicenová Citation2020).

Moreover, these developments do not mean that the threat has exclusively shifted to the official political arena. The right-wing extremist link was also identified in relation to the paramilitary groups which operate within the territory of Slovakia. The 2017 Report mentions that an “unregistered organisation whose members were military sympathisers continued to hold exercises, recruit new members and present its activities to the public” (Report Citation2017) – clearly referring to the Slovak Conscripts organisation (Slovenskí branci). Despite these activities, combined with the conducting of vigilante-style patrols and collaboration with the Russian motorcycle gang, Night Wolves, the state was not able to react effectively against the Slovak Conscripts (Mareš and Milo Citation2019).

An important tool of right-wing extremists in their campaign from unofficial actors and political irrelevance towards an established political party was the Internet and social media in particular. Social media is seen as a platform used for the popularisation of radical opinions and a communication tool used for the activisation of extremist sympathisers. In Slovakia especially, the extreme right online network consists of both non-party and political party organisations, which form a cohesive horizontal network that is formalised and institutionalised and more conducive to close collaboration (Caiani and Kluknavská Citation2017). Social media were therefore exploited for the collaborative spread of extremist ideology and this threat prevails to this day.

A special category in the Reports is left-wing extremism. The threat of left-wing extremism, even though considered relatively low and “not intensive” (Report Citation2016), is associated with the anti-fascist scene. In 2011, the intelligence agency identified a connection with violent attacks against right-wing extremists. Afterwards, their activities moved primarily into the online sphere and the organisation of protest and cultural activities. In 2018, the SIS identified activities of left-wing extremists as attempts to

criticise and discredit Slovak XRW [right-wing extremism] representatives and protect the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersexual (LGBTI) persons in 2018. New themes emerged on the Slovak XLW [left-wing extremism] scene in 2018, e.g. the support for Kurdish military activities in Syria, the fight for gender equality and environmental activities against mining and burning brown coal (Report Citation2018).

In the evaluation of left-wing extremists, the intelligence agency uses its rhetoric to securitise legitimate activities, such as protests and cultural events aimed at the promotion of the humane treatment of migrants and refugees, promotion of the rights of sexual minorities and the struggle for environmental issues.

The protection of LGBTI rights, which is singled out as more of a long-term issue, has to be understood in the context of the wider elite and societal backlash against the rights of sexual minorities. The latter do not have much societal support in the relatively socially conservative Slovakia. They experience strong opposition from the political elite and Catholic Church (Guasti and Bustikova Citation2020). Most of the activities in support of LGBTI people are organised by NGOs and often have the support of liberal politicians. Therefore, securitisation of the whole agenda by the SIS leads to de-legitimisation of the attempts to expand or protect sexual minority rights, even if the activities are supported by a small group of more radical activists.

Overall, the focus given to the threat of extremism, both right-wing and left-wing remained relatively stable over the examined period, as can be seen from . However, the analysis showed that both threats of extremism underwent a dynamic change in the language of the intelligence agency. The threat of right-wing extremism shifted into the arena of institutionalised politics and the threat of left-wing extremism into the arena of political activism.

Threats from foreign actors

The growing complexity of both the physical and online infrastructure created a situation in which protection from foreign threats means focusing on a multiplicity of heterogenous hazards. These include more traditional threats in the form of the infiltration of foreign intelligence, threats to strategic infrastructure, as well as emerging cyber threats and information warfare. Foreign threats are conditioned upon domestic specifics, as well as the position of countries in the international security environment, mainly membership in the EU and NATO.

Activities of foreign intelligence agencies have traditionally been the focus of the Slovak Information Service as part of its counter-espionage function. In the first years under analysis, it identified attempts by several foreign intelligence services to “infiltrate central bodies of the state administration, security forces and to affect the public opinion” (Report Citation2011) in a more general fashion. In 2014, as a reaction to the Crimean crisis, the SIS identified Russia as an actor which intensified its activities in all the NATO and EU member states, including Slovakia. Only in 2018, members of Russian intelligence agencies were identified explicitly as a threat in their attempts to infiltrate and gain collaborators in the domestic state administration and security forces.Footnote7 Moreover, China was identified as an actor attempting to gain information in the area of information technologies and was also of interest in relation to its economic investment in the country.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent escalation of the Russia–Ukraine conflict in Eastern Ukraine was considered as a turning point for the security environment of the Slovak Republic in some of the security documents. This was most explicitly formulated in the White Paper on Defence of the Slovak Republic of 2016, prepared by the Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic. This document identified the threat of the potential escalation and spread of the conflict and established a paradigm of “national responsibility for defence” (White Paper on Defence of the Slovak Republic Citation2016). The document has served as a basis for expenditure in the field of national defence. Nevertheless, SIS does not identify the threat of military aggression in its publicly available documents, and it connects the negative impacts of the conflict more with the potential of illegal migration.

What are known as “hybrid threats” became another area of interest. These were first identified by the SIS to have a negative impact on society in 2016, even though only in a general manner.Footnote8 Hybrid threats can be understood as a range of instruments of power and influence aimed at the pursuit of national interests in foreign countries. Hybrid threats exploit the existing systemic vulnerabilities, using a variety of tools – ranging from the spread of disinformation, cyber attacks and strategic leaks, to the funding of extremist organisations or protest movements (Treverton et al. Citation2018). In the case of Central Eastern Europe, Russia is the most prominent actor responsible for hybrid threats. The growth of Russian disinformation campaigns was already identified during the Crimean crisis in 2014 as part of the active measures directed towards countries of interest (Kragh and Åsberg Citation2017).

The fact that no specific actor was mentioned by the SIS in relation to the spread of disinformation can be explained by the Slovak political dynamics. The Slovak National Party (Slovenská národná strana, SNS), which was a coalition party between 2016 and 2020, had an above-average relationship with Russia (Mikušovič Citation2019). The party also managed to block the new Security Strategy of the Slovak Republic, which was drafted in 2017 by the Ministry of Defence, and which identified Russia and the spread of disinformation as a new threat (Šnídl Citation2018). Anton Šafárik, the former Director General of the Slovak Information Service between 2016 and April 2020, was a Slovak National Party nominee. Therefore, the political context suggests that even a minority party is able to influence the emphasis on national security threats, even if only regarding the accuracy of the framing of the threat – whether it is constructed in a general manner or explicitly identifies the responsible actor.

The explicit identification of Russia as the source of disinformation only appeared in the 2018 Report, after other state institutions (such as the Ministry of the Interior) broke ground with the identification of Russia as a source of hybrid threats. The 2018 SIS Report states that the primary sources of disinformation campaigns were Russian sources, and these narratives were copied by the Slovak pro-Russian media and social media groups:

Particularly the so-called alternative media spread the propaganda campaigns and focused on false news and disinformation to discredit the EU and NATO as untrustworthy institutions and membership of them as damaging the national interests of members. The campaigns tried to deepen the public distrust of state institutions and political system itself and deepen the existing differences between various socioeconomic, ethnic and religious groups (Report Citation2018).

The aim of these activities is directed towards the undermining of institutional legitimacy and the destabilisation of institutions (Bennet and Livingston Citation2018).

A persisting problem of the Slovak state administration was cyber security. The SIS identified insufficient compliance with the security requirements imposed on public administration information systems and non-compliance with the principles of information security management. The staffing and financial provision of information security management in some public administration bodies is often unsatisfactory. This problem was also prevalent within the intelligence agency. Based on information from the Reports, this threat was considered as a serious issue and the agency participated in training courses conducted on different levels of state administration.

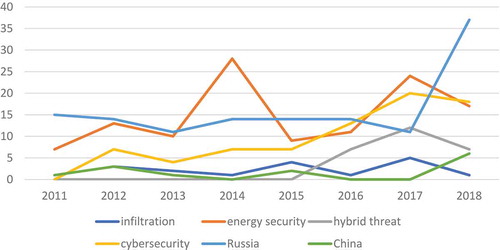

The dynamics between hybrid threats and cyber security, which are both closely connected, suggest that cyber security and hybrid threats, especially the spread of disinformation, were considered as rather technical issues due to their politically charged nature. Therefore, their detailed analysis was avoided until the 2018 Report. The development of the mention of these two threats in the Reports can be seen in . This analysis shows that both have been rising in significance.

Another long-standing foreign security threat is energy security, more specifically the transit of natural gas from Russia through Ukraine, and energy dependency on Russia. The threat materialised most prominently in January 2009, when a gas crisis between Russia and Ukraine resulted in the halting of the gas transit to Slovakia for 11 days (more information in Duleba Citation2009). The SIS focused its intelligence activities on the “risks of restriction or supply cuts of strategic raw material, especially oil and gas” (Report Citation2012). The focus on energy security intensified in 2014, in relation to the escalation of the Crimean crisis. Due to the energy dependency on Russian natural gas, energy security remains one of the most prominent threats, as illustrated in . The increase of mention in 2014 is connected with the escalation of the crisis in Ukraine. Another increase in 2017 is a result of the connection of the energy security threat with the threat of cyber attacks.

Decreasing the energy dependence on Russia has been a long-term goal for the Slovak Republic, resulting in attempts to diversify energy sources. In recent years, the greatest problem has been the dependence on sources of nuclear energy, with attempts by the state administration to decrease this dependency. Moreover, the attempts to decrease dependence on Russia also relate to military technology, which translated into several purchases of new military technology from Western countries (SME Citation2014).

Analysis of foreign security threats by intelligence assigns enemy images to specific actors, which are deemed responsible for the threat. In their Annual Reports, SIS assigned these images to two specific countries: Russia and China. As can be seen in , Russia was mentioned more often than China, since it had been a stable part of the intelligence discourse mainly because of the energy dependency on natural gas. The leap in mentions of Russia came in the 2018 Report, as a result of changing domestic political dynamics.

The threat of migration in the political discourse and its effects

The method by which threats are constructed by the intelligence service has effects on the political discourse and policy formulation in some specific areas. The effect of these constructions are not straightforward and cannot be analysed directly. However, I work with the assumption that it can influence the formation of discourse, or be instrumentalised for political purposes. The connection to the ruling political coalition exists through the Security Council of the Slovak Republic, which assigns responsibilities to the Slovak Information Service. The Head of the Council is the Prime Minister, and the Director of the SIS is a permanent member.

An overlap with the political discourse can best be illustrated by the discussions of migration. In Slovakia, the political elites traditionally held a restrictive approach to migration, even though it was not especially present in the public discourse (Androvičová Citation2016, 46). This changed dramatically with the migrant and refugee crisis in 2015. The topic of migration became dominant in public discourse, and also one of the main issues of the March 2016 parliamentary elections (Žúborová and Borárosová Citation2017).

The discourse centred around migration was a discourse of othering and exclusion, associating Muslim refugees with the theme of crime, including organised crime and terrorism, as well as the theme of cultural incompatibility with the local population, making the Muslim migrants undeserving and unacceptable (Kissová Citation2018). Moreover, these discourses of threats were instrumentalised by political actors and used as a legitimisation strategy in the electoral campaign. The securitisation discourse intensified after the Paris terrorist attack in November 2015. It was epitomised by the public statement by Prime Minister Róbert Fico, who said in a television broadcast: “We are monitoring every single Muslim in the territory of the Slovak Republic” (Čapkovičová Citation2015). This perpetuated and emphasised the construction of an “imaginary suspect community” (Breen-Smyth Citation2014) and gave it prominence in the public sphere, since the securitisation discourse came from the highest political position.

The connection between the political rhetoric and rhetoric of the intelligence apparatus was strengthened in the unusual press release by the Slovak Information Service published on 26 February 2016, which can be considered as its contribution to the culminating pre-election campaign. In this text, SIS warned against the heightened threat of terrorism due to the unconstrained influx of migrants into the EU:

The dysfunctional Schengen border allows not only war refugees, the persecuted and economic migrants to enter the EU, but also, without any control, people who pose real security threats, especially terrorist threats … Without spreading any panic, we consider the security situation to be serious for the reasons set out above, and several measures need to be taken as soon as possible to resolve it.

The discourse of otherness resulted in the willingness to aid only Christian refugees, based on the assumption of a shared religious background and thus higher compatibility with the local culture. At the end of 2015, Slovakia decided to accept 149 Christian refugees from Iraq. As argued by Kissová (Citation2018), this is also a result of the representation of Christian versus Muslim refugees in the political discourse, where the former were presented through personal stories filled with persecution and violence, while the latter were associated with terrorism and the threat of Islamisation.

The threat discourse was also used to push legislation aimed at the increase of law enforcement and intelligence competencies during the crisis, especially in the period after the 2015 Paris terrorist attack. In January 2015, the Ministry of the Interior presented a new Law on Intelligence Agencies which would expand the surveillance capabilities of the newly established intelligence agency (e.g. unlimited access to telecommunications metadata). This Law was presented as a reaction to the changing security landscape in Europe, including the heightened threat of terrorism. The new proposal created resistance from both civil society and opposition political parties and was eventually abandoned by the governing party (Kovanic and Coufalova Citation2020, 124).

The second legislative change came in November 2015, in the form of what was called the “Anti-terrorist Package”, which was a direct reaction to the Paris terrorist attack. The package included the amendment of 16 laws, expanding the competencies of both the Police Department and the Slovak Information Service. The explanatory report on the Law specified that the new legislation is a reaction to the terrorist attacks, as well as “the current increase in illegal international passenger transport and migration, cyber attacks, political and religious extremism” which have the capacity to threaten national security. The process of the passing of the legislation suffered from several legitimacy problems, not conforming to standard legislative procedures (Kovanic and Coufalova Citation2020, 125).

The language of internal threat construction, which can be identified in the language of the Slovak Information Service, entered the political discourse with the migration and refugee crisis in 2015. The securitisation approach to migration, which existed in the official documents was then formulated and re-formulated in the statements by politicians, including the highest ranks such as the Prime Minister. It was then instrumentalised for the purposes of the electoral campaign, but also had tangible effects on the formulation of migration policy and the response to the terrorist attacks carried out in Europe in 2015. These developments present evidence of the weak embeddedness of European norms and values in the majority of the political elite (Gál and Malová Citation2018, 115).

Conclusion

The publicly available parts of the Annual Reports of the Slovak Information Service provided insight into how the intelligence agency constructed the most prominent security threats and to which actors they assigned enemy images. When it comes to the hierarchy of threats, the threat of terrorism was considered as the most pressing. As an internal threat, its prominence increased with the migration and refugee crisis in 2014, and the subsequent terrorist attacks conducted in 2015 in Europe.

As an internal threat, terrorism was connected with migration and later assigned to migrants and refugees, especially those of a Muslim background. The language that was used by the SIS assigned a terror identity to the Muslim population. The very small local Muslim population was indirectly identified as a low, yet possible danger in relation to radicalisation and Islamism. In a similar fashion, construction of the threat of left-wing extremism assigned an extremist label to the left movement, advocating anti-fascism and the protection of minority rights.

When it comes to the effects of these labels, the political discourse securitised the migration and refugee crisis and made similar connections between terrorism and migration as the intelligence discourse. As suggested by Palacios (Citation2018), there was a convergence of narratives used by the political elite and intelligence agency. These narratives were instrumentalised for the purposes of a parliamentary election campaign for the 2016 elections, as well as for the legitimisation of controversial measures adopted for the purposes of the struggle against terrorism. With regards to migration and terrorism, the rhetoric of the political elite supplemented the “age of fear” (Acharya Citation2014). The fear of migrants also spread to the level of society, where several opinion polls showed that migrants were considered as a security threat by large portions of the population in December 2015, reaching the level of 70% of citizens (Mesežnikov Citation2016, 115–118).

The construction of foreign threats reacted to the activities of foreign intelligence, as well as broader geopolitical developments. Traditionally, it focused on the energy security threat due to Slovakia’s dependency on Russian natural gas, and also reacted to the rise in cyber threats and hybrid threats. On the other hand, the construction of the external enemy image was dependent upon the domestic political dynamics, more specifically the willingness of the political actors to acknowledge the Russian threat in relation to cyber and hybrid threats. The ideological closeness of the Director of the SIS to the pro-Russian Slovak National Party facilitated the fact that the connection of these threats with Russia was not explicitly mentioned in the Annual Reports until 2018 Report.

Intelligence agencies have an epistemic function (Pili Citation2019) and they construct the knowledge of threats to national security. They formulate and re-formulate who is a threat and assign enemy images. As demonstrated in my analysis, some threats can be over-exaggerated or assigned to larger parts of the population, as a result of the prevailing political interest or societal norms and prejudices. For the same reasons, other threats might be underestimated or downplayed through their presentation in an inexact manner. Therefore, in order to ensure that intelligence agencies operate within democratic standards and rules (Caparini Citation2007), the focus should not only be placed on their legal mandate and the effectiveness of their activities, but also on the language that is used in relation to the threats they identify and monitor.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martin Kovanic

Martin Kovanic, is an assistant professor at the Department of Social Studies, Faculty of Regional Development and International Studies, Mendel University in Brno. His research interests include surveillance, intelligence and post-communist politics. He has published several articles and book chapters on these issues. In 2015, he conducted a research visit at Vienna Centre for Societal Security. He also participated on the EU project Increasing Resilience in Surveillance Societies (IRISS) and other national grants in the field of surveillance and security.

Notes

1. The term “terrorism” is a contested and problematic concept in itself. It is criticised as a moral or political term, a rhetorical label that is instrumentalised to serve specific political goals. For a more detailed criticism, see e.g. (Jackson Citation2007). For a discussion of the problems of its conceptualisation, see e.g. (Weinberg, Pedahzur, and Hirsch-Hoefler Citation2004).

2. Since I was interested in the language of the documents, and they are prepared for Slovak parliamentarians and the public, and then replicated in the discourse, I worked with the Slovak variants of the Reports in my analysis. Slovak versions are available at https://www.sis.gov.sk/pre-vas/sprava-o-cinnosti.html. However, the quotes presented in the analysis are taken from the English variants, since official translations are provided by the agency.

3. For example, the code “terrorist” thus includes the Slovak words terorizmus, terorizme, terorizmom, terorista, teroristi, teroristov, teroristický, teroristickú, teroristická, teroristické, teroristického, teroristickej, teroristickou, teroristických, teroristickým and teroristickými. Similar logic is applied to the rest of the analysed codes.

4. At the height of the migrant and refugee crisis in 2015, EUROPOL identified an increased threat to security in relation to Jihadist terrorism and foreign terrorist fighters in their EU Terrorism Situation and Trend (Report Citation2016). Nevertheless, in relation to Slovakia, it observed low threat levels in this regard.

5. There is only one case of Slovaks connected to terrorism in the past years. The first was the case of the explosion of a home-made bomb in front of a fast food restaurant in the town of Košice in December 2011. The explosion caused only material damage. The culprit was originally found guilty of the crime of terrorism, but it was later requalified by the intervention of the Supreme Court of the Slovak Republic to a public threat. More information about the case can be found in Slovak at: https://kosice.korzar.sme.sk/c/20612152/prvy-slovensky-terorista-dostane-odskodne.html

6. The extent to which the migration and refugee crisis affected Slovakia can be illustrated by the numbers of asylum requests, which did not exceed over 400 per year, even at the height of the crisis between 2014–2016, and the low numbers of granted asylums (14 in 2014, 8 in 2015, 167 in 2016, 29 in 2017). The figures of 2016 include 149 Christian refugees, which will be discussed later in the article. The overview of statistics can be found on the website of the Ministry of the Interior, available at https://www.minv.sk/?statistiky-20

7. The discussion about the infiltration of agents of Russian intelligence agencies has gained a lot of prominence in the Czech Republic in recent years. The Czech Security Information Service identified several fields in which they attempt to collect information. See, for example, (Kundra Citation2018). It can be hypothesised that the situation was also relatively comparable to Slovakia.

8. With regard to the recognition of Russian hybrid warfare as a security threat, the comparison with the Czech Republic is striking, where it rose to one of the most prominent threats between 2014 and 2016 (Daniel and Eberle Citation2018).

References

- Acharya, A. 2014. Age of Fear: Power versus Principle in the War on Terror. Routledge Revivals. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Altheide, D., M. Coyle, K. DeVriese, and C. Schneider. 2008. “Emergent Qualitative Document Analysis.” In Handbook of Emergent Methods, edited by S. Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy, 127–151. London: Guilford Press.

- Androvičová, J. 2016. “The Migration and Refugee Crisis in Political Discourse in Slovakia: Institutionalized Securitization and Moral Panic.” Acta Universitatis Carolinae, Studia Territorialia 16 (2): 39–64.

- Atkinson, P., and A. Coffey. 2004. “Analysing Documentary Realities.” In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice, edited by D. Silverman, 56–75. Second ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Aytac, E., and A. Carkoglu. 2019. “Terror Attacks, Issue Salience, and Party Competence: Diagnosing Shifting Vote Preferences in a Panel Study.” Party Politics. Online First. doi:10.1177/1354068819890060.

- Baele, S. J., O. C. Sterck, T. Slingeneyer, and G. P. Lits. 2019. “What Does the “Terrorist” Label Really Do? Measuring and Explaining the Effects of the “Terrorist” and “Islamist” Categories.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42(5), 520–540. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2017.1393902

- Béland, D. 2007. “Insecurity and Politics: A Framework.” Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers Canadiens De Sociologie 32 (3): 317–340.

- Bennet, L., and S. Livingston. 2018. “The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions.” European Journal of Communication 33 (2): 122–139. doi:10.1177/0267323118760317.

- Bogain, A. 2017. “Security in the name of human rights: the discursive legitimation strategies of the war on terror in France.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 10(3), 476–500. doi:10.1080/17539153.2017.1311093.

- Bozinovic, F. 2017. “Finding the Limits of France’s State of Emergency.” Claremont-UC Undergraduate Research Conference on the European Union 2017: 4.

- Breen-Smyth, M. 2014. “Theorising the “Suspect Community”: Counterterrorism, Security Practices and the Public Imagination.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 7 (2): 223–240. doi:10.1080/17539153.2013.867714.

- Caiani, M., and A. Kluknavská. 2017. “Extreme Right, the Internet and European Politics in CEE Countries: The Cases of Slovakia and the Czech Republic.” In Social Media and European Politics. Rethinking Power and Legitimacy in the Digital Era, edited by M. Barisione and A. Michailidou, 167–192. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Caparini, M. 2007. “Controlling and Overseeing Intelligence Services in Democratic States.” In Democratic Control of Intelligence Services: Containing Rogue Elephants, edited by H. Born and M. Caparini, 3–24. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Čapkovičová, D. 2015. “Fico Pobúril Výrokom O Monitorovaní Moslimov Ich Komunitu.” Noviny.sk, November 16. https://www.noviny.sk/slovensko/154627-fico-poburil-vyrokom-o-monitorovani-moslimov-ich-komunitu

- Caudle, S. L. 2009. “National Security Strategies: Security from What, for Whom, and by What Means.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 6 (1): 1–26.

- Daniel, J., and J. Eberle. 2018. “Hybrid Warriors: Transforming Czech Security through the ‘Russian Hybrid Warfare’ Assemblage.” Czech Sociological Review 54 (6): 907–931. doi:10.13060/00380288.2018.54.6.435.

- Demirsu, I. 2017. Counter-terrorism and the Prospects of Human Rights. Securitizing Difference and Dissent. London: Palgrave.

- Duleba, A. 2009. Poučenia z plynovej krízy v januári 2009. Analyza príčin vzniku, pravdepodobnosti opakovania a návrhy opatrení na zvyšenie energetickej bezpečnosti SR v oblasti dodávok zemného plynu. Bratislava: VC SFPA.

- Duquet, N., and K. Goris. 2018. “The Illicit Gun Market in Belgium: A Lethal Cocktail of Criminal Supply and Terrorist Demand.” In Triggering Terror. Illicit Gun Markets and Firearms Acquisition of Terrorist Networks in Europe, edited by N. Duquet, 21–80. Brussels: Flemish Peace Institute.

- EUROPOL. 2016. European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) 2016. Hague: EUROPOL. file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/europol_tesat_2016.pdf.

- Florquin, N., and A. Desmarais. 2018. “Lethal Legacies: Illicit Firearms and Terrorism in France.” In Triggering Terror. Illicit Gun Markets and Firearms Acquisition of Terrorist Networks in Europe, edited by N. Duquet, 169–236. Brussels: Flemish Peace Institute.

- Fry, M. G., and M. Hochstein. 1993. “Epistemic Communities: Intelligence Studies and International Relations.” Intelligence and National Security 8 (3): 14–28. doi:10.1080/02684529308432212.

- Gál, Z., and D. Malová. 2018. “Slovakia: A Farewell to A Passive Policy-taker Role?” In Central and Eastern Europe in the EU. Challenges and Perspectives under Crisis Conditions, edited by C. Schweiger and A. Visvizi, 106–119. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gill, P. 1994. Policing Politics. Security Intelligence and the Liberal Democratic State. New York: Frank Cass.

- Gill, P., and M. Phythian. 2016. “What Is Intelligence Studies?” The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs 18 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1080/23800992.2016.1150679.

- Gill, P., and M. Phythian. 2018. Intelligence in an Insecure World. Third ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Guasti, P., and L. Bustikova. 2020. “In Europe’s Closet: The Rights of Sexual Minorities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” East European Politics 36 (2): 226–246. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1705282.

- Hatemi, P. K., R. McDermott, L. J. Eaves, K. S. Kendler, and M. C. Neale. 2013. “Fear as A Disposition and an Emotional State: A Genetic and Environmental Approach to Out‐Group Political Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 279–293. doi:10.1111/ajps.12016.

- Ibrahim, M. 2005. “The Securitization of Migration: A Racial Discourse.” International Migration 43 (5): 163–187. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00345.x.

- Jackson, P. 2007. “The Core Commitments of Critical Terrorism Studies.” European Political Science 6 (3): 244–251.

- Jackson, P. 2010. “On Uncertainty and the Limits of Intelligence.” In The Oxford Handbook of National Security and Intelligence, edited by L. K. Johnson, 452–471. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jensen, C. J. I. I. I., D. H. McElreath, and M. Graves. 2018. Introduction to Intelligence Studies. Second ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kissová, L. 2018. “The Production of (Un)deserving and (Un)acceptable: Shifting Representations of Migrants within Political Discourse in Slovakia.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 32 (4): 743–766. doi:10.1177/0888325417745127.

- Kovanic, M., and A. Coufalova. 2020. “The Legitimacy of Intelligence Surveillance: The Fight against Terrorism in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” Intelligence and National Security 35 (1): 115–130. doi:10.1080/02684527.2019.1634389.

- Kragh, M., and S. Åsberg. 2017. “Russia’s Strategy for Influence through Public Diplomacy and Active Measures: The Swedish Case.” Journal of Strategic Studies 40 (6): 773–816. doi:10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830.

- Kundra, O. 2018. “V Česku je zhruba 120 ruských diplomatů. BIS odhaduje, že třetina z nich jsou špioni.” Hospodářské noviny, August 3. https://archiv.ihned.cz/c1-66209060-v-cesku-je-zhruba-120-ruskych-diplomatu-bis-odhaduje-ze-tretina-z-nich-jsou-spioni

- Lenč, J. 2017. “Unwelcome Foreigners: Muslims in Slovakia.” In Muslims Are: Challenging Stereotypes, Changing Perceptions, edited by A. Bilá, 78–91. Bratislava: Open Society Foundation.

- Lenč, J. 2019. “Slovakia.” In Yearbook of Muslims in Europe, edited by O. Scharbrodt, S. Akgönül, A. Alibašić, J. S. Nielsen, and E. Račius, 554–566. Vol. 11. Leiden: Brill.

- Mareš, M., and D. Milo. 2019. “Vigilantism against Migrants and Minorities in Slovakia and in the Czech Republic.” In Vigilantism against Migrants and Minorities, edited by T. Bjørgo and M. Mareš, 129–150. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mathiesen, T. 2013. Towards a Surveillant Society. The Rise of Surveillance Systems in Europe. Hook: Waterside Press.

- Mesežnikov, G. 2016. “Problematika migrácie autečencov na Slovensku v rokoch 2015–2016: Spoločenská atmosféra, verejná mienka, politickí aktéri.” In Otvorená krajina alebo nedobytná pevnosť? Slovensko, migranti a utečenci, edited by G. Mesežnikov and M. Hlinčíková, 113–152. Bratislava: Inštitút pre verejné otázky.

- Mikušovič, D. 2019. “Ruský rok Andreja Danka: v Moskve bol častejšie ako v Prahe, doviezol si aj doktorát..” Denník N, December 27. https://dennikn.sk/1698131/rusky-rok-andreja-danka-v-moskve-bol-castejsie-ako-v-prahe-doviezol-si-aj-doktorat/

- Monaghan, J., and K. Walby. 2012. “Making up ‘Terror Identities’: Security Intelligence, Canada’s Integrated Threat Assessment Centre and Social Movement Suppression.” Policing and Society 22 (2): 133–151. doi:10.1080/10439463.2011.605131.

- Nail, T. 2016. “A Tale of Two Crises: Migration and Terrorism after the Paris Attacks.” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 16 (1): 158–167. doi:10.1111/sena.12168.

- Nociar, T. 2012. Right-Wing Extremism in Slovakia. International Policy Analysis. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Palacios, J.-M. 2018. “The Role of Strategic Intelligence in the Post-Everything Age, the International Journal of Intelligence.” Security, and Public Affairs 20 (3): 181–203. doi:10.1080/23800992.2018.1532181.

- Pantazis, C., and S. Pemberton. 2009. “From the ‘Old’ to the ‘New’ Suspect Community. Examining the Impacts of Recent UK Counter-Terrorist Legislation.” British Journal of Criminology 49 (5): 646–666. doi:10.1093/bjc/azp031.

- Phythian, M. 2012. “Policing Uncertainty: Intelligence, Security and Risk.” Intelligence and National Security 27(2), 187–205. doi:10.1080/02684527.2012.661642.

- Pili, G. 2019. “Intelligence and Social Epistemology - toward a Social Epistemological Theory of Intelligence.” A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy 33 (6): 574–592. doi:10.1080/02691728.2019.1658823.

- Quiggin, T. 2007. Seeing the Invisible. National Security Intelligence in an Uncertain Age. London: World Scientific Publishing.

- Report. 2011. “2011 SIS Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, October 2012. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2011.html

- Report. 2012. “SIS 2012 Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, November 2013. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2012.html

- Report. 2013. “SIS 2013 Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, October 2014. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2013.html

- Report. 2015. “SIS 2015 Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, June 2016. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2015.html

- Report. 2016. “SIS 2016 Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, May 2017. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2016.html

- Report. 2017. “SIS 2017 Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, May 2018. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2017.html

- Report. 2018. “SIS 2018 Annual Report.” Slovak Information Service, June 2019. https://www.sis.gov.sk/for-you/sis-annual-report-2018.html

- SME. 2014. “Výborom prešlo zníženie energetickej a vojenskej závislosti od Ruska.” SME, May 13. https://domov.sme.sk/c/7200617/vyborom-preslo-znizenie-energetickej-a-vojenskej-zavislosti-od-ruska.html

- Šnídl, V. 2018. “SNS blokuje prijatie dokumentov, ktoré označujú Putinovo Rusko za hrozbu.” Denník N, June 30. https://dennikn.sk/1166628/sns-blokuje-prijatie-dokumentov-ktore-oznacuju-putinovo-rusko-za-hrozbu/

- Spielvogel, C. 2005. ““You Know Where I Stand„: Moral Framing of the War on Terrorism and the Iraq War in the 2004 Presidential Campaign.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 8 (4): 549–569. doi:10.1353/rap.2006.0015.

- Treverton, G. F., A. Thvedt, A. R. Chen, K. Lee, and M. McCue. 2018. Addressing Hybrid Threats. Stockholm: Swedish Defence University.

- Vicenová, R. 2020. “The role of digital media in the strategies of far-right vigilante groups in Slovakia.” Global Crime 21 (3–4): 242–261. doi:10.1080/17440572.2019.1709171.

- Warner, M. 2007. “Sources and Methods for the Study of Intelligence.” In Handbook of Intelligence Studies, edited by L. K. Johnson, 17–27. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Warner, M. 2009. “Intelligence as Risk Shifting.” In Intelligence Theory: Key Questions and Debates, edited by P. Gill, S. Marrin and M. Phythian, 16–32. New York: Routledge.

- Weinberg, L., A. Pedahzur, and S. Hirsch-Hoefler. 2004. “The Challenges of Conceptualizing Terrorism.” Terrorism and Political Violence 16 (4): 777–794. doi:10.1080/095465590899768.

- White Paper on Defence of the Slovak Republic. 2016. Bratislava: Ministry of Defence of the Slovak Republic. https://www.mosr.sk/data/WPDSR2016_LQ.pdf

- Wolfendale, J. 2006. “Terrorism, Security, and the Threat of Counterterrorism.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29 (7): 753–770. doi:10.1080/10576100600791231.

- Woods, J. 2011. “Framing terror: an experimental framing effects study of the perceived threat of terrorism.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 4 (2): 199–217. doi:10.1080/17539153.2011.586205.

- Woods, L. 2017. “United Kingdom. The Investigatory Powers Act 2016.” Journal of Data Protection & Privacy 1 (2): 222–232.

- Žúborová, V., and I. Borárosová. 2017. “Migration Discourse in Slovak Politics. Context and Content of Migration in Political Discourse: European Values versus Campaign Rhetoric.” Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics 11 (1): 1–19.