?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article presents the findings of an explanatory study into the perceptions of Dutch Muslims in The Hague concerning pre-emptive counter-extremism and de-radicalisation policies. Based on 15 in-depth interviews with established Muslim community figures and a theoretical survey of 102 respondents from 8 mosques, it was found that pre-emptive interventions were perceived unfavourably due to their inherent misconceptualization of the Muslim lived experience. Respondents perceived wide-ranging negative labelling, viewing policies as not just ineffectual but also detrimental in a climate of persistent Islamophobia. In reality, these Dutch Muslims were faced with tackling the challenges of radicalisation based on their existing levels of social and cultural capital. Securitisation forces some Dutch Muslims into further retreat at a time of existing issues of social exclusion and political polarisation. This research highlights the need for greater sensitivity to Muslim community norms and values in developing policy in this area.

Introduction

The topic of Salafism is at the “top of the list” in attempts being made to understand the mechanisms driving radicalisation in the Netherlands. Salafism is defined as a branch of Islamism where followers believe they should live their lives according to the guidance provided by the first three generations of Islam (de Koning Citation2013). Salafist influences were a concern for the Dutch security services before the 2004 assassination of Dutch film director Theo van Gogh, but the murder caused a surge in Dutch national security service interests in surveilling radical Salafism (de Graaf Citation2010). Following the assassination, the “Hofstad” terrorist group emerged as a threat, gaining notoriety in the Netherlands for its expansive network of connections, as well as polarising members, with some “suspected of planning attacks against politicians” (Vidino Citation2007, 584). Van Gogh’s killing prompted the government to set up the NCTV (National Coordinator for Counter-Terrorism and Security). Increased surveillance has led to Salafist organisations being placed under a constant spotlight, hampering their ability to effectively disseminate their ideology. On the other hand, conflating “Islam with the risk of terrorism” has been a concurrent phenomenon in matters of security, leading to Muslim communities being under constant observance (Bull and Rane Citation2019, 2). This “othering” of the Muslim social identity has propelled isolation and is said to be a “catalyst for springing religious terrorists into action” (Jackson Citation2007, 406; Abbas Citation2007). In some cases, pre-emptive measures across society are considered so deleterious that Muslim communities perceive themselves as “aliens” in mainstream society.

This article examines the extent to which Dutch Muslim communities in the political metropolitan of The Hague perceive themselves to be adversely labelled by the current pre-emptive policies of deradicalisation. The Dutch Ministry of Safety and Justice maintains that pre-emptive security measures concerning radicalisation include aspects such as cooperation with Muslim community leaders, communication with education systems, police surveillance, and community centres for Muslim youth (Ministry of Security and Justice, National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism, and Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment Citation2014). However, the Inspectorate Ministry has thus far not evaluated the effectiveness of policies aimed at Muslim communities (Inspectorate of Security and Justice, and Ministry of Security and Justice Citation2017). This has repercussions for broader issues of integration and multiculturalism.

Thus, an opening exists where the “consideration of voices” of communities and their experiences of “counter-terror measures” is lacking (Spalek and Lambert Citation2008, 260). This remains a problem in the Netherlands but the experience of Dutch Muslim communities regarding securitisation has not yet been understood either. This research article constitutes an attempt to assess the perceptions of Dutch Muslims on matters of counter-terrorism and pre-emptive de-radicalisation, and the nature of how securitisation reinforces the “suspect community” paradigm. It is argued that in the Dutch context, there are numerous limitations in implementing effective counter-terrorism and counter-extremism policy, with community members reporting little or no direct engagement, which is compounded by a casual Islamophobia that arguably reflects growing wider political sentiment in Western Europe. The findings have implications for improving counter-extremism and de-radicalisation initiatives as well as wider social cohesion policies.

Theoretical Framework

The Rise of Salafism in the Netherlands

Jihadi Salafism is known as the branch of Salafism that purposefully uses violence to ensure that society adheres to Sharia laws as written in the Qur’an and practiced by the first three generations of Muslims (Pall and Martijn Citation2017). Jihadi Salafism has brought about increased levels of anxiety in Dutch society, especially after the Salafist Hofstad group planned, and were in the process of executing, a series of terrorist attacks. Nevertheless, adhering to Salafism in the Netherlands was not thought illegal until the implementation of the Crimes of Terrorism Act in 2004 and the creation of the NCTV in 2005. The intent to support Jihadi Salafist organisations was made punishable in 2004, but it is also apparent that branches of Salafism are not entirely motivated by extremism and violence (Vellenga and Kees Citation2019). Rather, there are three recognised clusters: (1) Selefies: apolitical and non-violent; (2) political Salafists: non-violent and political activists, and (3) jihadi Salafists: participate in politics and are violent (de Graaf Citation2010).

Historically, the growth of Salafism in the Netherlands emerged many years after the major labour migrations of Moroccan, Turkish, and Surinamese workforces during the 1960s-1980s (Buijs and Frank Citation2009). Initially, the Dutch government adopted policies to support and legally recognise Islamic religious practices, as awareness of the disadvantages facing Muslim communities had begun to increase (Buijs and Frank Citation2009). In effect, the lack of equality facing Dutch Muslim communities permitted Salafism to act “as an instrument of security and protection in an insecure and changing […] minority situation” (Olsson Citation2014, 173). Muslim youths were becoming accustomed to disaffection and dissatisfaction in a climate of fear orchestrated by Dutch politicians “trying to crush this [form of Islam] from above” (Buijs and Frank Citation2009, 429). Policies enacted during the 1980s recognised that integration policies in pursuit of a multicultural society had failed (Fadil, Koning, and Ragazzi Citation2019). Although the number of assaults encountered by Muslims was higher after the Theo Van Gogh murder in 2004 than after the 9/11 attacks, harsh security measures specifically targeting Muslim communities were commended by 90% of the Dutch population (Buijs and Frank Citation2009, 434).

In Dutch society today, the worry that Salafism is eroding Dutch norms and values has become a topic of frequent discussion. A joint investigation by “NRC Handelsblad” newspaper and TV programme “Nieuwsuur” in 2019 exposed 50 Mosques in the Netherlands in which Jihadi Salafist ideologies were allegedly being taught (Kouwenhoven and Milena Citation2019). Most of the teachings highlighted the need to reject Dutch society and required followers to take multiple-choice tests. Options for the punishment of “non-believers” included: “(a) lashes (b) stoning or (c) death by sword”, in which option (c) was taught to be the correct answer (Kouwenhoven and Milena Citation2019). Children were ostensibly trained to believe that non-Muslims and Muslims who do not follow the Jihadi Salafist ideology should be considered non-human and deserve punishment by death. However, there has been harsh criticism from Dutch Muslim communities, who have objected to the negative labelling; “[t]hrough such a generalized message, it is as if every mosque is suddenly deemed as dangerous” (Reub Citation2019). Nevertheless, Saïd Bouharrou, a member of the Moroccan Mosque Foundation, denounced such teachings as “horrendous” and detrimental to the image of Muslim communities (Kouwenhoven and Milena Citation2019).

As a result of the investigation, the government immediately inspected the 50 mosques and tightened education inspection regulations. Additionally, the House of Representatives issued a formal request to increase transparency concerning foreign investments in mosques and religious institutions (Reub Citation2019). The fear that Salafism has become an increasing threat to Dutch society became evident in 2019 when the Ministry of Social Affairs set up the “Taskforce Problematic Behavior & Unwanted Foreign Funding” to curve the increase of Salafist influences within the Muslim communities (Koolmees Citation2019). The issue of Salafism in the Netherlands introduced a chain reaction of pre-emptive security measures, overwhelming Dutch citizens with concerns over their national security.

Securitisation of Islam

The concept of pre-emptive measures is deemed a “symptom” of national security, where implementation demonstrates increased awareness of possible threats (Mythen Citation2012). A transformation occurs during securitisation which alters counter-terrorism into “risk management” (de Graaf Citation2019, 97). Expectations of possible dangers emanating from within Muslim communities can become a triggering factor in the actions of security services. Consequently, the “National Counterterrorism Risk Strategy 2016–2020” by the NCTV emphasised the importance of flexibility in such actions (National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism Citation2016). In a letter from the NCTV to the House of Representatives, five main pre-emptive intervention goals were highlighted (Grapperhaus and Piece Citation2017):

(1) Gaining insight on possible attacks through surveillance;

(2) Prevention and disturbance of extremist individuals;

(3) Protecting individuals and property from radicalised individuals;

(4) Optimal preparedness in case of an attack;

(5) Preserving democracy and legally pursuing radicalised individuals.

Some of the pre-emptive measures mentioned in the report, Evaluation of the Netherlands Comprehensive Action Programme to Combat Jihadism, include active “cooperation with the Muslim community, Support for educational institutions”, and the “Mobilization of societal opposition and enhancing resilience against radicalization and tensions” (Inspectorate of Security and Justice, and Ministry of Security and Justice Citation2017, 43). The strategic framework stated the importance of cooperation between many organisational bodies, such as intelligence services, local governments, security services, police, companies, social services, mental health care, education, and welfare organisations. For these measures to be effective, the House of Representatives provided the NCTV with 13 million EUR in addition to the standard budget (Grapperhaus and Piece Citation2017). This expansion demonstrated that the pre-crime rationale among the Dutch government has taken priority over post-crime actions.

However, a pre-emptive security rationale triggered adverse reactions from UK Muslim communities, where the “subject of heightened popular and state Islamophobia” was relentless (Tufail and Poynting Citation2013, 43). As a result, Britain became exclusionary through its deradicalisation policies. Similarly, a survey study of 2,088 respondents in Australia noted that ethnic minority groups tend to perceive pre-emptive policies as “racial profiling and […] over-policing” (Murphy and Cherney Citation2011, 238). Yet, with stricter procedural justice mechanisms implemented concerning pre-emptive policies, the perception and willingness of the communities to cooperate with the state were not present due to a loss of trust (Murphy and Cherney Citation2011). The impact of securitising Muslims in the UK and Australia has contributed to a widely held perception that the police and government misconstrued groups, giving rise to the “innocent until proven Muslim” concept (Tufail and Poynting Citation2013, 48).

The Voice of the “Other”

The notion that European Muslims have become isolated through securitisation is not a new proposition (Abbas Citation2007). The idea that Muslim communities are a constant threat has become everyday parlance in many circles of influence, including in media, politics, and policy. The perception of being the “other” has propelled isolation. In some cases, it is said to be a “catalyst for springing religious terrorists into action” (Jackson Citation2007, 406). The Minister in charge of counter-terrorism in the UK during 2005 said that, “Muslims will have to accept their ‘reality’” of being subject to frequent police stops (Abbas Citation2007, 294). This has led to criticism that these pre-emptive security measures act as push factors in radicalisation, with heightened levels of perceived discrimination among Muslims increasing the likelihood of larger support for radical groups (Mirahmadi Citation2016). The duality present within the communities is one in which they must cooperate with the government to fight radicalisation, yet at the same time moderate their behaviours so as not to trigger the suspicion of security services (Roex and Vermeulen Citation2019). This has caused many Western European governments to view such communities “as Muslims first and citizens second” (Edmunds Citation2012, 74).

A study in the US concerning the hearings on The Extent of Radicalisation in the American Muslim Community and That Community’s Response by Homeland Security noted that the association of radicalisation and Muslim communities was inherently present (Edwards Citation2015). The study showed that deradicalisation policies could be seen as an exclusionary “tool of power exercised by the state […] to control Muslim communities” whilst justifying various policy implementations (Edwards Citation2015, 114). The reality of social exclusion triggers Muslim communities to perceive such measures as hostile, with pre-emptive policies bringing about “unwanted and unwarranted attention” (Tufail and Poynting Citation2013, 48). This attention culminates in adverse perceptions of law enforcement and the internalisation of self-policing among Muslim communities.

An evaluation report from the Dutch Inspectorate of the Ministry of Justice and Security noted that most of the pre-emptive measures concerning cooperation with Muslim communities had not been evaluated for efficiency or effectiveness (Inspectorate of Security and Justice, and Ministry of Security and Justice Citation2017). Moreover, online reports from the municipality of The Hague reported that surveys to gauge perceptions in highly populated Muslim neighbourhoods have not been conducted (‘The Hague In Numbers: Safety [Translated]’ Citation2019). The necessity of understanding and cooperating with Muslim communities is a vital component in the struggle against radicalisation and in delivering effective policy outcomes. Yet, when looking into the consequences of these pre-emptive measures, such as in the UK, it seems as though these policies have been counter-effective (Tufail and Poynting Citation2013). Understanding the position from the scrutinised point of view could inform the security realm of how policies affect Muslim communities in light of an outwardly accepting society. “[G]enerically labelled Muslims” have deemed such policies a major factor that contributes to their “hostile” label (Mythen Citation2012, 414).

Methodology

Data Collection

Using a deductive approach, this mixed-methods study was carried out to ascertain the explanatory factors of the research question (Walliman Citation2011). This methodology is nomothetic, where the assumption of negative perceptions is based on the universal applicability of the hypothesis (Möller and Nyman Citation2005). The Hague holds the highest percentage of Muslims living within its municipality (14.7%), compared to other large metropolitans such as Rotterdam (13.7%), Amsterdam (12.1%), and Utrecht (9.9%) (NOS Citation2017). In 2018, 5% of the total Dutch population followed Islam (CBS Statline Citation2019b). It is expected that in 2050, the total percentage of Muslims in The Netherlands will rise to 7.6 (FORUM – Institute for Multicultural Affairs Citation2010, 10). Moreover, it was noted by the Institute for Multicultural Affairs in 2010 that an average of 10% of Moroccan youths (18–25 years old) was suspected of crime versus 2.5% of Non-Muslim youths (FORUM – Institute for Multicultural Affairs Citation2010, 25). The Hague was chosen as the site for the research to “reveal the conditions in which policies are enacted [and] to argue more strongly for policy development” (Simons Citation2015, 173).

A mixed-methods approach was chosen to collect data in the form of face-to-face interviews and drop-and-collect surveys. A total of 15 semi-structured interviews took place with “elite” Muslim community members, such as imams or mosque board members. Each interview was conducted in Dutch and subsequently translated, transcribed, and analysed in English using thematic analysis. The interviews were recorded to “maintain the level of accuracy and richness of data” (Meyer Citation2001, 339). Drop-and-collect surveys were chosen as a second method. The survey consisted of 45 statements based on an even Likert scale. The survey was no longer than an A4-double sided paper so as to maintain the respondents’ attention and to ensure that answers were given truthfully rather than as quickly as possible. A total of 102 surveys were completed by members from eight different mosques in The Hague. The eight Mosque consisted of members with Surinamese, Turkish, and Moroccan cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, all eight follow the Sunni branch of Islam. However, one of the eight mosques has been labelled by media and politicians as teaching radical Sunni ideologies. Muslim groups that are part of a religious foundation also have commonalities based on ethnic or cultural association, permitting the targeted characteristics to be accurately interpreted from the survey (Brückner Citation2011).

Operationalisation

Interviews and Surveys

Various websites of all the mosques in The Hague were scouted to acquire contact information and potential respondents; however, the response rate to emails was low. Telephoning the mosques served as the primary method of communication. From September through to November 2019, over 280 phone calls were made. Most responses were an immediate rejection of participation in the research. Conversing in a colloquial language and less official terms helped foster a connection and the will to participate in the interviews. The term “Salafism” was not used by the interviewees themselves. The topic of Salafism is known to be a sensitive issue; therefore, for the respondents to remain at ease and to not cause an immediate adverse reaction to the research, this term was not brought up unless by the respondents themselves. This was averted by using vocabularies such as “radical Islam” or “extremism”. This more subtle approach to the interviews allowed for the snowballing of a long list of potential contacts and a dependable network.

Each interview was conducted at the choice of the respondent, including at train stations, a doctor’s office, mosques, homes, offices, and Turkish cafés. Most interviews took take place on weekends or Friday after the Jummah prayers and they lasted an average of one hour and fifteen minutes. A headscarf and long-sleeved shirts were worn to each interview to show respect. It was said to be appreciated, allowing the ice to break and to ensure a more relaxed atmosphere during the interview. However, on other occasions, the interviewer was not welcome, which manifested in glares from mosque followers or an unwillingness to converse whilst waiting for the respondent to arrive. It demonstrated a lack of trust of outsiders on the part of attendees, especially given the female gender and Dutch ethnicity of the interviewer. However, the co-author of this study is a Muslim male academic, well-versed with the research topic in an international context, and thus able to mediate in matters of cultural, religious, or ethnic sensitivity so as to ensure the overall effectiveness of the project.

The process of obtaining survey respondents proved to be challenging. Drop-and-collect surveys left the responsibility of finding respondents with members of the mosques. Over 400 surveys were printed out in total. Only two interviewees allowed the possibility of leaving surveys behind at the mosques, with the condition of no more than ten or fifteen surveys to be filled out. There were two stated reasons for refusing to share the surveys. First, most members of the mosque did not understand Dutch or English very well. Second, interviewees did not want to expose their members to a survey containing highly sensitive and controversial topics. Consequently, contacting the Foundation Islamic Organisation (FIO) gained more respondents. below provides a descriptive profile of the survey sample.

Table 1. Demographic descriptive frequency

Each interview was conducted and transcribed in Dutch. For the use of this research, quotes were translated into English. Thematic analysis revealed 10 categories, containing 112 indicators. The surveys were analysed using SPSS Version 24.0 (IBM Corp Citation2016).

Reliability and Validity

There has not been a survey conducted before on this topic, thus no validity measures were previously established. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) allowed for new variables and measures to be determined and tested for their relationships, grouping certain variables together that measure components in commonality (Hayasbi and Yuan Citation2010). A total of 7 composite variables emerged after a series of EFAs with Oblimin-Kaiser rotations. The across-loading limit of >.03 was chosen since the survey was exploratory. Thus, the limit of exclusion was reduced to gain composite variables that were conceptually similar. From the EFA, a total of 26 questions remained in 7 composite variables for further analysis. An additional 5 variables, which were not found to be conceptually similar to the other composite variables in the EFA, were chosen from the survey due to their importance to the research. These included: Islam Perception 4 (I am aware of the negative perceptions of Islam), Islam Perception 6 (People judge me negatively for practicing Islam), Radicalisation 25 (I perceive to be negatively labelled by society because of radicalised individuals), Radicalisation 26 (I perceive to be negatively labelled by security forces because of radicalised individuals), and Pre-Emptive Measure 27 (I am aware of the security measures against radicalisation). Once construct validity was established, the 7 component variables were tested for reliability via Cronbach’s Alpha. Each of the 7 composite variables had a score of α = .774 or higher, thus passing the criterion value of α >.70 for reliability to be established. below presents the results of the factor analysis.

Table 2. Results of factor analysis a.: pattern matrix.

Results and Analysis

“The Dirty Game that is Politics”

The “Tool” of Islamophobia

According to 14 of the interviews, the negativity surrounding Islam has seeped into the Dutch political system. The survey discovered a negative correlation between composite variables Religious Discrimination and Effectiveness of Pre-Emptive Measures, r(100) = −.209, p= .035. Pre-emptive measures towards radicalisation were not considered effective by the respondents, whilst religious discrimination maintains a prominent hold in The Hague. Politicians were frequently blamed for the negative labelling of Muslims in society. The phenomenon of abasing Islam for political gain was frequently mentioned by the interviewees. One respondent felt that politicians manipulate society:

Politics must have a scapegoat […] One has to cultivate a certain fear against another culture. Just to be able to grab votes. This is what prevails now. And that is because politicians as demagogues can play on people’s ignorance. (Zubair Citation2019)

The infamous 2014 “Less Moroccans! Less Moroccans!” slogan yelled out by Geert Wilders during a campaign speech was thought to have been counter-productive, contributing towards a “breeding ground” for young individuals (Narish Citation2019). The hostile environment was seen as having been generated by politicians with interests in maintaining their party’s popularity. For instance, when the terrorist attack of 19 March 2019 in Utrecht pressured various political parties to halt campaigning as a show of respect for the victims, the FvD (Forum of Democracy) continued to campaign and blamed the terrorist attack on the influx of Muslim migrants (Fallon Citation2019). The FvD campaign ended with the most seats in the House of Representatives, with the political party leader stating “[p]eople no longer believe in the Netherlands. That’s for sure. No longer in Western civilization either … ” (Tempelman Citation2019).

The redundancy of pre-emptive policies was noted by many respondents. The less survey respondents felt they were able to practice Islam without judgement, the less they deemed pre-emptive policies to be effective (F(6,94) = 3.66, p= .003, = 0.138). Consequently, it was argued that a mentality had fostered among Muslim youths which revealed itself in daily situations. One respondent noted how the clear divide of good and bad was equated with “Muslim and non-Muslim”:

If an individual can be linked to Islam, then Islam is put on the naughty bench. If ‘Jan’ does it [terrorist attack], then Jan is responsible for his actions […] It’s just crooked (Latib Citation2019).

Zubair noted the abuse of policies for political gain as also present. Islamophobia creates popularity for certain political parties, amalgamating with the inaction of politicians to listen to the Muslim community. This lethargy was understood by Zubair as a case of politicians inadvertently supporting policies that “are polarizing. And when that is done, we don’t have a voice” (Zubair Citation2019). The lack of political support for Muslim communities had entrenched a sense of immense irritation. Zubair opined that pre-emptive policies created a fissure that broke down cohesion among societies. Understanding the consequences of such policies could repair the social disconnect between non-Muslim and Muslim communities. Nevertheless, the aspect of being labelled negatively was present among all 15 interviewees.

Feeling Misunderstood

According to the survey respondents, incorrect understandings of Islam by politicians are one of the primary reasons negative labelling occurs. The perception of being negatively labelled as radicalised (n= 101, m= 5.15, sd = .860) was “Agreed” by most respondents. Respondents with a Dutch majority background (n= 11, m= 4.61, sd = .976), as opposed to respondents with a non-Western background (n= 90, m= 5.21, sd = .828), experienced significantly less negative labelling (t(100) = −2.237, p= .027). This perspective can explain a certain disdain towards politics. Anger as well as a lack of trust was found among the interviewees when discussing this topic. Tabeeb, a Mosque board member, shared an experience in which,

Many young individuals are starting to say ‘F**k you. I’m done. Who do they think they [politicians] are?’ They then go in the wrong direction, and we try to corral them. […] I’m worried. I have four grandchildren. I’m not worried about my position but that of my grandchildren, the coming generation (Tabeeb Citation2019).

Many respondents argued that politicians had not sufficiently made the connection between being Muslim and an active member of society. Misinformation was regarded by 14 interviewees as harmful to their self-perception.

On 12 February 2020, the Parliamentary Committee on the influence of Salafism on Dutch mosques suggested that the fear interviewees had had was justified (NOS Citation2020). The vice-president of the CMO (Contact Body Muslims and Government) Ahmet El Boujoufi, (CMO Citation2020) stated that Muslim youth were vulnerable to extreme Salafist ideologies, explaining that some youth uncritically accept changes to mosque policies and Salafistic ideologies (NOS Citation2020). At the public hearing, it was specified that board members of mosques who came to speak in front of the committee were threatened by Muslim youths. The Director of the AIVD (General Intelligence and Security Services), Dick Schoof, declared on 10 February 2020 that the social cohesion of Muslim youth is being disrupted by Salafist recruiters who “start with childcare, where young children are taught anti-integration and anti-democratic values that go against Western society” (Feenstra Citation2020).

The characteristic of most Salafists being young Muslim individuals is found to be historically accurate in the UK, according to a 2008 report by the University of London (Al-Lami Citation2008). It was noted that a majority of radical Muslims originated from the first generation of immigrant parents (ibid). The concern that the next generation may turn to radical Salafism with less hesitation was a persistent thought among some of the respondents in this study, especially as discrimination against Muslims was palpable, and it has a role in making younger people more susceptible to extremist influences. More recently, Leszczensky, Maxwell, and Bleich (Citation2020) discovered that the notion of most Jihadi Salafists being young Muslim individuals to be correct within the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, and the UK. A statistically significant variation of Religious Discrimination (n = 102, m= 2.87, sd = 1.14, t(100) = −3.35, p= .001) was found for individuals under the age of 35 within the survey. That is, they experienced more religious discrimination (n = 45, m= 3.28, sd = 1.15) than those aged above 35 (n = 56, m= 2.55, sd = 1.04).

“It’s Not News unless it’s a Hype”

Negative Labelling

Research into public opinion on Islamophobia in Europe and the US has determined that “perceptions of Muslims are connected to political views” (Ogan et al. Citation2013, 40). The Dutch media was condemned by most interviewees. Board member Narish was quick to declare that, “the media keeps shoving the label of radicalization our way because they need to have a group to show the negativity of Islam” (Narish Citation2019). The creation of the misrepresented “hype” allows politicians to extend policies across cultural boundaries to securitise the “other”. The consistent coverage of Muslims in the media was viewed by Zaheer as a “profit machine” (Zaheer Citation2019). Narish echoed this issue: “you can throw a lot of money at something, but if the media shows evidence to the contrary then the policies are of no use” (Narish Citation2019). Adverse press coverage was viewed as rendering policy ineffective by casting Muslims in a negative light, where the Muslim community itself becomes the central focus, thus increasing their exclusion. From the “Pre-emptive Policies” category, the “Non-effective policy” indicator was ranked sixth out of 26. Continuous negative labelling reverses the purpose of pre-emptive policies as the reputational disadvantage affects the Muslim community’s self-perception. The indicator of “Negative Self-Perception” was the fourth highest of 11 other indicators within the category of “Emotional Responses”. It is the opinion of Zaheer that they are constantly being handed responsibility to counter to the actions of others. He said,

We always need to justify ourselves. Actually, we are already 1-0 behind, and because of that we have to work so much harder against the media to prove it is not the case (Zaheer Citation2019).

How politicians use the media to push Islam into a negative light was mentioned in 14 interviews. The survey analysis found that Religious Discrimination was positively correlated (r(99) = .682, p<.001) with Radical 26 (I perceive to be negatively labelled by security forces because of radicalised individuals). That is, the more religious discrimination was experienced by respondents, the more respondents perceived that they were negatively labelled by the security services.

Instilling the Fear of Islam

The Hague was mentioned by respondents as one of the main “Salafist hubs” in the Netherlands, in which all Muslim communities were thought to be “held responsible for jihadist attacks elsewhere” (de Graaf Citation2010, 17–18). Subsequently, Dutch society is perceived as possessing anxiety towards Islam, which is present in the media, politics, and education. Cahil explained that through the media in Dutch society, young Muslim children are confronted with prejudice daily. He shared an example in which his son attending elementary school was given a task: “Muslims were shown to be terrorists in the picture books, with a couple of options: ‘Who is the Muslim?’ That’s horrible. Horrible!” (Cahil Citation2019). Instilling fear of Islam has become habitual among Dutch society according to the interviewees. Not being provided the benefit of the doubt no longer occurs, according to Cahil. The sheer ridiculousness of accusations has led to a continuous battle with those who view non-Muslims to be narrow-minded:

Everyone is quick to judge. Having a big mouth, yet not cleaning up their sh*t. […] But look in the mirror as to how democratic the Netherlands is. Look at the statements by the media. […] I honestly sometimes could cry (Cahil Citation2019).

The “sh*t” Cahil is referring to is the grudge the Muslim community has against politicians and the security services. The frequent “statements like ‘F**k off to your own country’” have been enough for Cahil to become ashamed of Dutch society (Cahil Citation2019).

A 2017 study of the influence of negative media on Muslims in the US revealed that “more balanced news coverage of Muslims […] would reduce the perception that Muslims are necessarily violent” (Saleem et al. Citation2017, 863). The lack of trust in the media and its reports of radicalism in The Hague was grasped as an issue by respondents. The “limited reflection of [anti-Islamic incidents] in the media confirm the feeling of many Muslims that they are second-class citizens under threat” (Buijs and Frank Citation2009, 429). This sentiment was echoed by the indicator “Not believing the Media” being the second-highest in the category of “Media Influence”. Omar reiterated that the community is slowly shifting into a mentality of automatically not believing media reports:

When we read that, we think ‘is that really how it is?’ […] People are more like ‘pff, again another story, it won’t stop, it’s only going to get worse’ So we don’t believe those [media reports] anymore (Omar Citation2019).

Normalisation of Islamophobia has amounted to what Omar describes as sensationalism aimed at creating a common enemy for society as a whole:

Did you see what they wrote about the [undisclosed] mosque? About a preacher and circumcising women? It’s totally not Islamic. This was something that happened in 2015 and it is brought up every year to create hype (Omar Citation2019).

The necessity of keeping Dutch society absorbed by policymaking requires a level of anxiety to be constantly maintained (Jackson Citation2007). For politicians to securitise the issue of radical Salafism, they transform the notion of radicalisation into a binary distinction, in which Muslims can either be “bad” or “good”. The dualistic distinction presented by the media strips the identity of Muslim individuals and marks entire communities as either “safe or radical” (Kibria, Watson, and Selod Citation2018). Policies such as surveillance or disturbance became a justified means to lessen the perceived anxiety of Dutch society. The additional pre-emptive policies that arise due to the increased presence of Salafism among Muslim communities has led to the perfect breeding ground for recruitment. The discrimination felt by the Muslim community was identified as acceptable political action, rendering pre-emptive policies as counter-productive and destructive of Muslim social identities. The malleability of their social identities becomes a window of opportunity for Salafists. Salafism is then able to take advantage of the consequences that result from pre-emptive policies and further their ideology through the discontent perceived by the Muslim communities. Internal conflicts that exist when perceiving to be labelled as the “other” increased affinity towards Jihadi Salafists. Such tropes as the “emergence of a parallel society” (Ardriaanse Citation2020) have become a cornerstone for radical Salafists to gain influence among disaffected youth, where Salafism coincides well with a securitised population (Schuurman, Bakker, and Eijkman Citation2018).

Pre-Emptive Policies: “Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire!”

Façade Policies

Throughout the 2000s, the AIVD released multiple reports about the Salafi community in the Netherlands. One recent report noted that in the early 2000s both “active government policy and Muslim communities’ enhanced resilience to radicalization” deterred Salafist recruiters (General Intelligence and Security Services, and Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2014). Similarly, some interviewees in this study said that this “resilience” could be helpful when executed correctly. Yet, in practice, this cooperation was deemed to be faulty. A reoccurring theme among the interviewees was the feeling of being used by the government as a “shield” rather than a co-operator. Tabeeb explained,

We are pushed aside like ‘that is your thing, you do what you do and we [government] will do our own thing’. But when sh*t hits the fan, I get called in to extinguish the fire (Tabeeb Citation2019).

Once the government involves the Muslim community, the blame for ineffective policies becomes collective. Muslim communities being used as political backlash “armour” shifts the scales of power entirely to their disadvantage; policymakers are essentially setting up Muslim communities for inevitable disappointment. From the category of “Pre-emptive policies,” the indicator “Do not trust security services” was placed eight out of twenty-six. Furthermore, the survey showed that the dependent variable, I am aware of the negative perceptions of Islam, had one significant predictor variable – I am aware of the security measures against radicalisation), with a p-value of .001. The regression (F(6,96) = 2.34, p= .038, =.131) was also statistically significant. If an understanding of pre-emptive measures was present, a higher level of awareness of the negative perception of Islam was also found among the respondents.

The 2017 Inspectorate of Security and Justice report, Evaluation of the Netherlands Comprehensive Action Programme to Combat Jihadism, stated that the policy concerning “cooperation with the Muslim community” had not been evaluated for efficacy (Inspectorate of Security and Justice, and Ministry of Security and Justice Citation2017). “Combating Radicalization” involved the participation of citizens within Muslim communities and had not been evaluated either. Securitised policies which were deemed by AIVD reports as essential have been implemented, but seemingly executed blindly. The sporadic involvement of the Muslim community when it benefits the political image of The Hague was comprehended as damaging trust. The appearance of the municipality’s “do-gooder” attitude shatters when the manipulation of “elite” Muslim community members is found.

Disrupting Policies

One of the main strategic methods the security services apply when it comes to pre-emptive measures is the policy of disruption. Latib had multiple experiences with the policy: “Everything that has to do with the foundation – they use the disruption method” (Latib Citation2019). Latib and other mosque board members had frequent confrontations due to feeling unjustly chosen for inspections or other random controls by the police. Statistically, this is indicated in the data: the Prejudice Towards Muslim Communities variable correlated significantly positive with Perception of Security Services, r(100) =.572, p <.001. The more prejudice is perceived among Muslim communities, the higher they scored on perceived heightened police presence. Likewise, the variable of Perception of Security Services had a negative correlation with Islam Perception, r(100) =.-466, p=.001. Thus, the more the respondents perceived the security services to be negative, the lower the scores on Islam Perception. With a positive security service perception score, respondents felt that they could practice Islam less freely in The Hague.

Latib explained how matters intensified in recent periods when he rented out 50 storage units on the premises of the mosque. The police had found a “bait bike” in the storage units, allowing them to raid the unit. What was shocking for him was that the tenant who had the “bait bike” in his possession was not charged. Yet, Latib was facing a possible court dispute concerning the closure of the mosque and had to allow police access onto the entire premises. Latib noted that nothing was found, except for the stolen bike, which the police already knew to be there. The police were described as “mafia-like” due to their underhanded approach. Muslim community and security services relations were understood to be at a stalemate.

The implementation of pre-emptive policies does not allow for the natural flow of democratic processes, since securitisation does not have time for normal deliberations (Roex and Vermeulen Citation2019). In its place, an expedited process of intervention occurs, in the process, not allowing the consequences of the policy to be fully appreciated by policymakers. This is also verified through the statistics of the survey analysis. A significant regression equation (F(6,94) =3.62, p=.003), with an of 0.188 in terms of Perception of Security services and six independent variables, were found. Respondents with a Dutch background scored 0.532 lower in terms of perceived security services than non-western background respondents. Dutch individuals had a more positive opinion of the security services than non-western background individuals in The Hague.

The need to hear the voice of the “other” has not been taken into consideration, rendering the policies ineffective in the eyes of interviewees. Constant vigilance, combined with the mentality that to be understood the Muslim community must be completely transparent, has created anger among the youth. A wave of frustration pushes individuals such as Cahil to become desperate. He stated,

Do we have to expose ourselves completely? What do we still have to do? I can only take off my jacket, but I can’t lower my pants anymore! […] We’re always looked at with a certain stare […] I’m not going to take crazy steps to show them [NCTV/AIVD] otherwise (Cahil Citation2019).

The indicator “Perception of being specifically targeted” obtained the highest score in the thematic analysis. Additionally, “Perceived discriminatory policies”, in the category “Pre-emptive policies” gained the highest score out of a total of 26 total indicators. The data combined with the stories shared by Latib and others demonstrated that pre-emptive policies lead to higher levels of division and dissatisfaction.

The Burqa Ban

On 1 August 2019, the so-called “Burqa ban” (boerkaverbod) law came into force in the Netherlands. It implements a partial ban on face-covering clothing, which applies in certain locations, including governmental buildings, educational institutions, and public transport. Although the law, which was proposed by Geert Wilders, expressly applies to a range of clothing including “ski masks, full-size helmets, and other face-covering garments”, the name listed on the government website remains “boerkaverbod”, which suggests an intent to target Muslim women (McAuley Citation2019).

When it came to the question of Religious Discrimination (n =102, m =2.87, sd =1.14), a t-test revealed that gender played a significant role in how religious discrimination was perceived (t(100) = −2.267, p=.026). On the question of religious affiliation, females (n=35, m=3.05, sd =1.05) revealed that they perceived themselves (n=35, m=3.05, sd =1.05) to be more discriminated than males (n=66, m=2.52, sd =1.15). Females (n=35, m=3.78, sd =.997) deemed pre-emptive measures to be less effective compared with the males (n=67, m=4.29, sd =.739). Moreover, females responded higher in their mean score (n=35, m=4.24, sd =1.44) of Radical 25(I perceive to be negatively labelled by society because of radicalised individuals) (n =102, m =3.39, sd =1.48) than males (n=67, m=3.49, sd =1.46); (t(100) = −2.489, p=.014). Finally, the variable Radical 26 (I perceive to be negatively labelled by security forces because of radicalised individuals) showed that gender played a significant role yet again (t(99) =−2.2034, p=.045). The results showed that females have a higher perception score in terms of negative labelling by security services than males. The Burqa ban negatively affected female perceptions of security services and society.

A frequent response to the Burqa ban was one of astonishment. During the policy-making process, a respondent at the FIO was engaged with. Tabeeb explained that although he was brought in as a consultant, the coordinator of the Approach to Radicalisation and Polarisation in The Hague at the time, Tamara Jopp, did not engage with his feedback. After waiting eighteen months for a reply, he felt “snubbed” by the administration. Hadad described the repercussions of the policy since its implementation. His daughters at school were frequently subjected to smartphone videos sent by other pupils consisting of men beating up women wearing Burqas. His wife frequently gets yelled at or “gets spit or scolded as a ‘penguin’ […] With guys from the car yelling ‘lookout, you’ll end up flat on the street!’” (Hadad Citation2019). The discrimination Muslim women face when wearing a burqa depicts the social environment in which intolerance of Islam is largely accepted. In the eyes of Hadad, the ban is another political measure that undermines the image of Muslim communities and their self-perception. When confronted daily with phrases such as “Why do you wear a headscarf in Holland, don’t be weird!”, it is understandable that members of the Muslim community become irate at the constant projection of Islam as something fearful (Hadad Citation2019).

The Double-Edged Sword of Government Communication

Policy-making is the realm of government, but it is also “monopolizing public thinking” (Kiser Citation1999 as in Raadschelders 2000). Through policy decisions that are being made in a restricted “zone”, interviewees repeated that policy-makers are out of touch with Muslim communities. Policies affect Muslim communities daily, yet the vital role that leading members of the Muslim community can play is mostly ignored:

I think that often people don’t know what Muslims believe in and what they stand for. […] The PVV, the FvD. They have never been in contact with such a person [Muslim], so that is often the point. […] And can’t imagine living in our situation (Zubair Citation2019).

According to Hadad, the lack of will on the part of the government to communicate and listen to the Muslim community is viewed as sabotaging policies before they are even implemented. The Central Bureau of Statistics noted that in 2017, 82.8% of neighbourhoods in The Hague sought contact with the police of their own accord, whilst police sought 17.2% contact with neighbourhoods (CBS Statline Citation2019a). Additionally, a low 33.9% agreed that the police want to contact neighbourhoods (CBS Statline Citation2019a). The indicator of being “heavily misunderstood” was the second-highest in the category of “Islam and its perception”. It demonstrates the dissatisfaction the Muslim community has been lost on policymakers. Tabeeb understood that any changes to the policies “reset” their development:

[The government should] talk to the FIO, talk to someone who has knowledge of it. I MEAN HELLO?! We hear this, we see this, we notice this. And we don’t say ‘Solve it for us’ but we call for joint action to ensure that this does not go further (Tabeeb Citation2019).

A harmful relationship combined with a lack of effort on the part of the government to engage in effective cooperation mitigates negative perceptions against the Muslim community. The indicator “Not being taken seriously by the police” within the category “Pre-emptive policies” scored ninth out of 26 indicators. Additionally, the Effectiveness of Pre-emptive Measure is a significant predictor (p=.078) for Radical 26 (I perceive to be negatively labelled by security forces because of radicalised individuals). The more negative the labelling by the security services, the less effective pre-emptive measures were perceived.

Interviewees believed that if the Muslim community stays silent and does not want to cooperate, they remain susceptible to negative labelling (Moshin Citation2019). Unless the Muslim community takes the initial steps to communicate and cooperate with security services, they remain labelled as a possible “threat” (Omar Citation2019). Omar described that communication with the police was done only for “survival” purposes and to make clear that his mosque was not radical. Omar noted the policy of cooperation and communication with Muslim leaders was not being practiced in reality. The constant observance the Muslim community is subjected to is deemed problematic.

In a similar vein, as part of the securitisation process, the UK government categorised vast swathes of British Muslims as potential radical Salafists or Islamists (Spalek and Lambert Citation2008). The notion of following variations on conservative of traditional Islam was being conflated with extremism where, “being singled out […] when going about their [Muslim leaders] business, […] undermines their confidence as stakeholders” within the cooperation policy (Spalek and Lambert Citation2008, 267). Directly labelling communities as “dangerous”, the UK police “focus(ed) on groups and networks in ways that obscure the extent to which their operations may sometimes impact adversely on communities” (Spalek and Lambert Citation2008, 266). The consequences of securitisation further negatively label Muslim communities, which in turn can impede the readiness of Muslim leaders to cooperate with security services in support of policy implementation.

Non-Effective Pre-Emptive Policies

The lack of awareness from the government is central to understanding that certain policies, although made with good intentions, have been rendered inadequate. Zubair plays an integral role in his mosque’s activities and replied to the question of pre-emptive deradicalisation measures with dissolution: “I don’t know at all what the municipality is doing to combat radicalization” (Zubair Citation2019). The rising number of radical Salafists in The Netherlands is regarded as not slowing down (General Intelligence and Security Services, and Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2010). Many interviewees went as far as to state that it is only logical. It was specified that government subsidies to promote community projects were used by Salafist centres to endorse radical ideas (General Intelligence and Security Services, and Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations Citation2010), for example, by groups publishing anti-Western homework booklets for children at the mosques. Omar has had many a time where,

The only thing the police do preventively is to occasionally talk a little about the recent incidents. ‘How are we going to solve that?’ But there are no real preventive measures (Omar Citation2019).

The AIVD has admitted that their measures since 2010 have not “help[ed] stem the new wave of radicalization” (Inspectorate of Security and Justice, and Ministry of Security and Justice Citation2017). Tabeeb views the lack of effectiveness to be a “performance show” for the AIVD to indicate that they are needed, thereby placing a target upon Muslim communities. This is statistically supported (t(100) = −2.804, p=.006) by the survey, where non-western background respondents were more likely to express negative (n=90, m=3.76, sd =.836) concerns regarding the Security Services than respondents with a majority Dutch background (n=11, m=3.02, sd =.711).

The focus on mosques today, as perceived by the interviewees, appears to be more in line with the interests of the AIVD and its continued demand for effective deradicalisation. Combining the need to cooperate with AIVD whilst moderating their behaviours and actions to avoid targeting has led to Muslim communities becoming both the victim and the criminal. Latib views AIVD efforts towards the mosques as a ploy to gain further interest in their existence:

I always say ‘if the AIVD says there is nothing wrong’ then they also get less budget. There must be problems because otherwise, they won’t get any money. Their right to exist is also linked to our demise (Latib Citation2019).

The policies were not thought to be effective by many of the interviewees. A personal account by Zaheer, depicted the consequences of the interventions further:

I will tell you because this is no longer really a secret. The first people who went to Syria went to ISIS. They were not radicalized. They were all drug dealers and you name it. […] They no longer had an adventure here. […] The second group that travelled there. They weren’t very smart guys. These were mostly from poverty line-like neighbourhoods […] Those were boys who used to be bullied by teachers at primary and secondary school. It was always said ‘Your father doesn’t speak Dutch, you don’t speak Dutch either’ […] the struggle is there. We ask the question ‘what is behind the question?’ We almost never ask them (Zaheer Citation2019).

His personal experiences have allowed him to directly support at-risk youths, potentially making Zaheer of great value to policy-makers; however, the only individuals who converse with Zaheer about the Muslim youths on a day-to-day basis are community officers.

From the survey analysis, it was statistically confirmed that Muslim youths are at a much higher risk of radicalisation. First, Religious Discrimination (n =102, m =2.87, sd =1.14) is significantly more likely to be experienced (t(100) = −3.35, p= .001) for individuals under the age of 35 (n =45, m =3.28, sd =1.15) than individuals over the age of 35 (n=56, m=2.55, sd =1.04). Second, from the composite variable Islam Perception, individuals who are older than 35 perceive themselves to be more accepted within society in terms of practicing Islam, t(100) = 1.821, p=.072. Furthermore, on Perception of Security Services (n=101, m=3.68, sd =.851), respondents under the age of 35 perceived significantly higher (n=45, m=3.98, sd =.780) Security Service involvement and Awareness of Police Presence, t(100) = −3.349, p=.001 than those above 35 (n =57, m=3.44, sd =.835). Individuals under the age of 35 perceived themselves to be negatively labelled due to radicalised individuals in The Hague. These survey results depict youth as more vulnerable to perceiving discrimination, whether religiously through the acceptance of Islam in society or through security services practices or as a result of society’s opinion towards radicalised individuals.

The Lack of Belief in Security Services

When asking interviewees their opinion on the policies implemented by the AIVD, two types of answers arose. First, the interviewees discussed the actions of AIVD as an organisation as a whole, rather than mentioning any specific policies that have been implemented. Second, there was a group that brushed off the question and preferred not to discuss AIVD in detail at all.

Moshin claimed to have monthly discussions with a contact person from AIVD. Throughout his interview, Moshin remained extremely positive about AIVD and the policies implemented, especially the policy of cooperation with Muslim communities. Yet, from the category Pre-Emptive Policies, the two indicators “Active cooperation with AIVD & NCTV” and “Effective policies” were ranked lowest out of the 26 total indicators. Importantly, no other interviewee was as positive about AIVD as Moshin. When interviewees were asked about specific AIVD policies, Omar added,

Liar, liar, pants on fire. It really isn’t like that. I challenge the AIVD to talk about this with me on television. I challenge them. Show me! That they have information here […] There is not a single mosque that I know has regular contact with the AIVD […] It’s stupid! Ridiculous! It’s very annoying. That is not at all true of what that report says (Omar Citation2019).

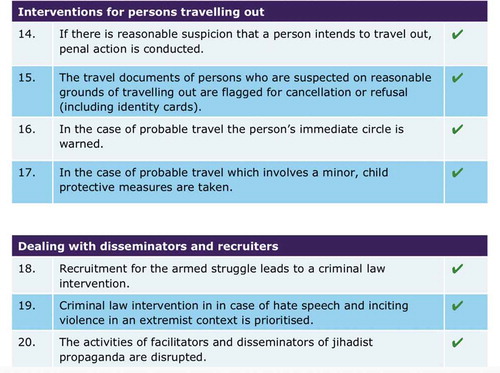

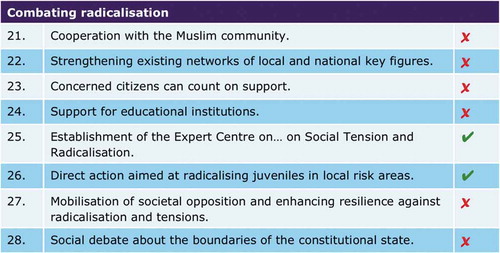

Such reactions do not come as a surprise. Although policies are said to be implemented by AIVD, they are not all evaluated further for efficacy and societal consequences after their implementation. below depicts that several policies concerning criminal law interventions, including possible travels outside Dutch borders and returning Foreign Fighters, have been examined by the Inspectorate Ministry of Justice and Safety. However, for the policies concerning Muslim communities and radicalisation, only two had been checked ().

Figure 1. Policies studied by the inspectorate of security and justice (inspectorate of security and justice, and ministry of security and justice Citation2017, 42)

Figure 2. Policies studied by the inspectorate of security and justice (inspectorate of security and justice, and ministry of security and justice Citation2017, 43)

To the bewilderment of the respondents, although such reports are published, politicians and aspects of the government routinely blame Muslim communities for harbouring and growing radicalised Salafists. Anxiety around the mosques when discussing the AIVD has become a staple emotion among the Muslim community. With such a constant sense of angst and vigilance surrounding securitised communities, a “clash of civilizations” is perceived to be taking place (Tufail and Poynting Citation2013, 47). It is a “clash” in which social cohesion begins to crumble and the negative labelling of the “other” becomes commonplace. Pre-emptive policies were fathomed as creating fear, where it was thought that Muslim communities can only be “corralled” if such fear is present.

“How Many Times Should We Respond?”

Radicalisation – Community Resilience

On the whole, Dutch pre-emptive policies are deemed ineffective by most of the interviewees, with some taking it upon themselves to create their own policies within their mosques. The creation of guidelines by mosques was proving to be highly effective against Salafistic radicalisation. For example, a group of Muslim communities in Victoria, Australia, took the initiative to create social activities and mentoring systems that have proven to “advance social inclusion and common security” (Halafoff Citation2012, 183). Not only had the Muslim communities in Australia promoted multicultural awareness, but they had also been effective in promoting counter-terrorism policies. In The Hague, the policies are deemed as “too little, too late” in terms of effectiveness. Hadad described that once radicalisation is noticed, “We have to do it ourselves […] We now solve radicalization ourselves” (Hadad Citation2019). Omar also mentioned that once an individual starts to radicalise, there is no protocol or external intervention from the police. Rather, the imam and board members at the mosque confront the individual themselves. Tabeeb shared an experience of a mentorship programme his mosque had organised together with its followers:

We have a residents’ organization. I get mothers of ‘I am afraid of my son, I no longer recognize him in his behaviour and he is with all kinds of figures I don’t know of.’ […] So then you sit with such a boy […] And then I don’t get the story of the mother herself but his own story of: ‘Did you hear what happens in Schilderswijk and Transvaal? My friends live there and they experience it.’ […]Then he sits [leaned back, crossed arm] and then says ‘F**k you, F**k police, and I have no job and I cannot finish my education. And then, Claudius [a Mentor] says, ‘Do you have to react like that? Why do radicalize towards me? […] If you need me, give me a call!’ And in this way, you also minimize the attitude (Tabeeb Citation2019).

The thematic analysis indicators such as “Non-effective policies” and “Failed policies” were ranked in the top five for the category of “pre-emptive policies”. Indicators such as “radicalized individuals are dealt with internally by the Imam and the board”, “call the police on own accord”, and “invest in own security” from the category of “mosque activities” depict the effort Muslim communities take themselves rather than waiting for government intervention that may not be effective. Tabeeb described another intervention initiative that prevented young women from the neighbourhood from travelling to Syria between the years 2015–2018:

We also have neighbourhood fathers. We have contact with the neighbourhood fathers who are almost all Moroccan who ask me ‘Do you have time tomorrow?’

Tabeeb: ‘Yes of course. What is it?’

‘No, no, no I don’t want to say it over the phone.’

Upon meeting, Tabeeb adds: ‘I have discovered that at the […] street on that number, there are girls who are almost certainly going to Syria’

Tabeeb: ‘How will you address the issue; how do you know?’

‘I spoke with the mother and her daughter has ideas to travel to Syria’. And that is handled as discreetly as possible (Tabeeb Citation2019).

Muslim communities in The Hague believe that they carry out the deradicalisation intervention without the aid of the security services, whose policies are deemed by interviewees as inverted – in the process, inflicting more damage than “good” to the community as a whole. Omar and other mosques had taken precautions such as screening the imams before they arrive at their mosques. Omar describes these precautions as self-preservation. He explained that,

They always want you to get the police right away, but that is not possible. I have to do research first. What is this individual about then? What is it? I also have to take into account the impact it has on the community […] And at a time when we call in the police. Then I know what will happen. […] Before you know it, the board members’ phones are tapped. Such a person is tapped and that appears in the newspaper with headlines: ‘Yes, the mosques have a radical imam. They are busy with all sorts of troubles’ (Omar Citation2019).

Muslim communities in The Hague have evolved into much more than a religious community. They have developed a sense of survival, in which precautions are taken to avoid the scrutiny of society and government. The indicator “proposed policies” within the category “mosque activities” scored the second highest. It indicates the self-awareness Muslim communities have about their potential demise when linked to radical individuals and are prepared to take action themselves to prevent further stigmatisation. In 2016, the Ministry of Social Affairs in cooperation with Experts in Media and Society stated that “distrust of the government and social institutions is also associated with multi-ethnic society”, where blame is frequently placed upon Muslim and migrant communities (Witten2017). It is no surprise that the interviewees tackle radicalisation without the aid of the government to avoid additional negative labelling from society.

Conclusion

This research has provided an original insight into the perspectives of Muslim communities in The Hague concerning pre-emptive policies concerning radicalisation. Through the 15 interviews and 102 survey responses, it is deduced that due to various policies, adverse labelling is largely perceived by individuals in the Muslim community. Not only has adversarial labelling been named as an overriding consequence of the implementation of policies, but the respondents themselves view the policies as counter-productive. Media and politics are linked in a destructive web that feeds each other to remain relevant and “exciting” in an attempt to thrust forward negative agendas. Policy-makers who lack a balanced point of view create policies that are believed to be misguided. Furthermore, to remain pertinent to the national security of The Netherlands, government bodies such as the AIVD and the NCTV are perceived to target Muslim communities on purpose. The amount of alleged misinformation and the lack of knowledge from both journalists and policymakers has led Muslim communities to distrust governmental bodies. According to the interviewees, the top-down model of policy decision-making has rendered the effectiveness of pre-emptive policies futile.

The distrust has led to Muslim youths becoming further disillusioned with Dutch society. This was assessed to be a great concern as it potentially leads vulnerable youth into the hands of Dutch Salafist recruiters. It was also noted that since the early 2000s, these recruiters have had the upper hand when it comes to evading the Dutch security services. Moreover, these policies have not only been observed as failing by the Muslim communities, but also by the AIVD themselves. This admission from the AIVD indicates that these pre-emptive policies have been created in a policy-decision “vacuum” where misinformation and lack of consequential awareness were abundant. The absent communication between Dutch Muslim groups and governmental bodies in The Hague has led communities to become isolated and frustrated. Pre-emptive policies, by nature, are primarily based upon community cooperation, but they are perceived to be failing. The deleterious consequences of ineffective policies have forced many Muslim communities to remain cautious.

This research has shown that The Hague is lacking the precise execution of deradicalisation policy and has not fully evaluated their effectiveness. The need for Muslim communities to monitor their behaviour whilst remaining completely transparent has led to an anxious existence. Social exclusion created via Islamophobia has thrown up severe barriers regarding the possibility of a well-integrated multicultural society. Muslim communities are not being heard; they are being watched from a distance. Consequently, Muslim communities have turned inward when searching for methods against radicalisation, no longer seeking the aid of security services in fear of being classified as “dangerous” or “evil”. In essence, deradicalisation has become a private matter. According to the interviewees, to involve security services only increases suspicions and adverse labelling. The burden was placed upon the Muslim communities to increase awareness within their communities. At the same time, their disadvantaged position in society is a consequence of discrimination and securitisation. It was noted that the privacy needed to deal with radicalised individuals is not wanted but necessary for their “survival”. Securitisation enforces the crumbling self-image of Muslim communities in The Hague. With increased anxiety surrounding the topic of Islam in The Hague, the self-perception of Muslim individuals has deteriorated.

The perspectives of Muslim communities are a crucial factor in the establishment of pre-emptive radicalisation policies. It is important to engage more proactively with communities affected by radicalisation to create truly effective policies, working closely with communities to take advantage of local knowledge and expertise. Jihadi Salafism can become less of a threat if policy-makers within Western Europe view the micro-dynamics of Muslim communities as vital signifiers for curbing Islamophobia and objectification within the realm of securitisation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Liselotte Welten

Liselotte Welten is a Cum Laude MSc graduate in Crisis and Security Management from Leiden University in the Netherlands. She received a bachelor’s degree with honours in Liberal Arts & Science with a major in Social Sciences from University College Roosevelt in Middelburg. She is currently researching Salafism in the Dutch context for the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in The Hague.

Tahir Abbas

Tahir Abbas is an Associate Professor in Terrorism and Political Violence at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University in The Hague. His recent books are Countering Violent Extremism (Bloomsbury, 2021, in press), Islamophobia and Radicalisation (Oxford University Press, 2019) and Contemporary Turkey in Conflict (Edinburgh University Press, 2017). His recent edited books are Political Muslims (co-ed., with S Hamid, Syracuse University Press, 2019) and Muslim Diasporas in the West: Critical Readings in Sociology (4 vols., Routledge Major Works Series, 2016). He has been a visiting scholar at the London School of Economics (2017-2019) and New York University (2015-2016).

References

- Abbas, T. 2007. “‘Muslim Minorities in Britain: Integration, Multiculturalism and Radicalism in the Post-7/7 Period.” Journal of Intercultural Studies Vol 28 (3): 2007. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07256860701429717

- Al-Lami, M. 2009. “Studies of Radicalisation: State of the Field Report”. Royal Holloway University of London Politics and International Relations Working Paper Series Paper no. 11.

- Ardriaanse, M. L. 2020. “The Influence Of Salafists Is Increasing [Translated].” NRC Handelsblad. https:/www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/02/10/invloed-salafisten-neemt-toe-a3989951 10 February 2020.

- Brückner, H. 2011. “‘Surveys’.” The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199215362.013.28. 6 January 2011.

- Buijs, P., and J. Frank. 2009. “Muslims in the Netherlands: Social and Political Developments after 9/11.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (3): 421–438. doi:10.1080/13691830802704590.

- Bull, M., and H. Rane. 2019. “Beyond Faith: Social Marginalisation and the Prevention of Radicalisation among Young Muslim Australians.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 12 (2): 273–297. doi:10.1080/17539153.2018.1496781.

- Cahil. 2019. “Interview.”

- CBS Statline. 2019b. “StatLine - Religious Affiliation; Personal Characteristics [Translated].” 2019. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82904NED/table?ts=160752638282

- CMO. 2020 “Organizational Structure - CMO’. Contactorgaan Moslims En Overheid.” Accessed 13 January 2021. http://cmoweb.nl/organisatiestructuur/

- Edmunds, J. 2012. “The “New” Barbarians: Governmentality, Securitization and Islam in Western Europe.” Contemporary Islam 6 (1): 67–84. doi:10.1007/s11562-011-0159-6.

- Edwards, J. 2015. “Figuring Radicalization: Congressional Narratives of Homeland Security and American Muslim Communities.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 12 (1): 102–120. November. doi10.1080/14791420.2014.996168.

- Fadil, N., M. Koning, and F. Ragazzi. (eds). 2019. Radicalization in Belgium and the Netherlands – Critical Perspectives on Violence and Security. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Fallon, K. 2019. “Forum Voor Democratie: Why Has the Dutch Far Right Surged?” AlJazeera. 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2019/3/25/forum-voor-democratie-why-has-the-dutch-far-right-surged

- Feenstra, W. 2020. “Director AIVD Warns Against “Salafist Drivers” [Translated].” De Volkskrant. https:/www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/directeur-aivd-waarschuwt-voor-salafistische-aanjagers~b2178f43/ 10 February 2020.

- FORUM – Institute for Multicultural Affairs. 2010. “The Position of Muslims in the Netherlands, Facts and Figures, 2010.” Fact Book. Utrecht, The Netherlands. https://www.eukn.eu/fileadmin/Lib/files/EUKN/2010/0_linkclick.pdf

- General Intelligence and Security Services, and Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations. 2010. “Current Trends and Developments in Salafism in the Netherlands.” Resilience and Resistance. The Hague: General Intelligence and Security Services (AIVD). https://english.aivd.nl/publications/publications/2010/04/14/resilience-and-resistance

- General Intelligence and Security Services, and Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations. 2014. ‘Swarm Dynamics and New Strength’. The Transformation of Jihadism in the Netherlands. The Hague: General Intelligence and Security Services (AIVD). https://english.aivd.nl/publications/publications/2014/10/01/the-transformation-of-jihadism-in-the-netherlands

- Graaf, B. D. 2010. “The Nexus between Salafism and Jihadism in the Netherlands”. CTC Sentinel 3(3): 17-22

- Graaf, B. D. 2019. “Foreign Fighters on Trial: Sentencing Risk, 2013–17.” In Radicalization In Belgium And The Netherlands: Critical Perspectives On Violence And Security, 97–130. I.B. Tauris. doi:10.5040/9781788316187.ch-004.

- Grapperhaus, and C. Piece. 2017. “Integral Approach to Terrorism Kst-29754-436 [Translated].” 28 November 2017. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-29754-436.html

- Hadad. 2019. “Interview.”

- Halafoff, A. 2012. “Building Community Resilience.” In Rohan Gunaratna, Jolene Jerard, and Salim Mohamed Nasir (eds.), Countering Extremism: Insurgency and Terrorism Series, Volume 1, 183–191. London: Imperial College Press.

- Hayashi, K., & Yuan, K.-H. (2010). Exploratory factor analysis. In N. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of research design (pp. 459–464). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- IBM Corp. 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Apple. ENG. IBM. version 24.0. Chicago, Illinois.

- Inspectorate of Security and Justice, and Ministry of Security and Justice. 2017. Evaluation Of The Netherlands Comprehensive Action Programme To Combat Jihadism. The Hague: Inspectorate of Security and Justice & Ministry of Security and Justice. https://radical.hypotheses.org/files/2016/04/EvaluationoftheNetherlandscomprehensiveactionprogrammetocombatjihadism.pdf

- Jackson, R. 2007. “Constructing Enemies: “Islamic Terrorism” in Political and Academic Discourse.” Government and Opposition 42 (3): 394–426. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2007.00229.x.

- Kibria, N., T. H. Watson, and S. Selod. 2018. “Imagining the Radicalized Muslim: Race, Anti-Muslim Discourse, and Media Narratives of the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombers.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4 (2): 192–205. doi:10.1177/2332649217731113.

- Kiser, L. 1999. “Democracy and the University Curriculum’. In Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, 7. Bloomington, MA: University of Michigan Press, Quoted in Raadschelders, Jos C. N. 2000. ‘Understanding Government in Society: We See the Trees, but Could We See the Forest?” Administrative Theory & Praxis 22 (2): 192–225. doi:10.1080/10841806.2000.11643448.

- Koning, M. D. 2013. “The Moral Maze: Dutch Salafis and the Construction of a Moral Community of the Faithful.” Contemporary Islam 7 (1): 71–83. doi:10.1007/s11562-013-0247-x.

- Koolmees. 2019. “Fundamental Rights In A Multiform Society; Government Letter; Integrated Approach To Problematic Behavior And Unwanted Foreign Financing Of Social And Religious Institutions: KST29614108 [Translated].” Government Website. Parlimentaire Monitor. 11 February 2019. https://www.parlementairemonitor.nl/9353000/1/j9vvij5epmj1ey0/vkvzo7el49yr#p3

- Kouwenhoven, A., and H. Milena. 2019. “Salafist Schools Teach Children To Turn Against The Netherlands [Translated].” In NRC Handelsblad. 10 September 2019. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2019/09/10/salafistische-scholen-leren-kinderen-zich-af-te-keren-van-nederland-a3972845

- Latib. 2019. “Interview.”

- Leszczensky, L., R. Maxwell, and E. Bleich. 2020. “What Factors Best Explain National Identification among Muslim Adolescents? Evidence from Four European Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (1): 260–276. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1578203.

- McAuley, J. 2019. “As the Netherlands’ Burqa Ban Takes Effect, Police and Transport Officials Refuse to Enforce It.” Washington Post. Accessed. 13 January 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/as-the-netherlands-burqa-ban-takes-effect-police-and-transport-officials-refuse-to-enforce-it/2019/08/01/a91fb648-b461-11e9-acc8-1d847bacca73_story.html

- Meyer, C. B. 2001. “‘A Case in case Study Methodology’.” Field Methods 13 (4): 339. doi:10.1177/1525822X0101300402.

- Ministry of Security and Justice, National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism, and Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment. 2014. “The Netherlands Comprehensive Action Programme to Combat Jihadism Overview of Measures and Action.” Overview of Measures and Actions. The Hague: Ministry of Security and Justice. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/ 44369.

- Mirahmadi, H. 2016. “Building Resilience against Violent Extremism: A Community-Based Approach.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 668 (1): 129–144. doi:10.1177/0002716216671303.

- Möller, A., and E. Nyman. 2005. “Why, What and How? – Questions for Psychological Research in Medicine.” Disability and Rehabilitation 27 (11): 649–654. doi:10.1080/09638280400018551.

- Moshin. 2019. “Interview.”

- Murphy, K., and A. Cherney. 2011. “Fostering Cooperation with the Police: How Do Ethnic Minorities in Australia Respond to Procedural Justice-Based Policing?” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology - AUST N Z J CRIMINOL 44 (2): 235–257. August. doi10.1177/0004865811405260.

- Mythen, G. 2012. “no One Speaks for Us”: Security Policy, Suspected Communities and the Problem of Voice.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 5 (3): 409–424. doi:10.1080/17539153.2012.723519.

- Narish. 2019. “Interview.”