ABSTRACT

Children who grow up in families who are affiliated with violent extremism and terrorism are frequently viewed through a security-oriented lens which focuses on their risk of radicalisation, or the security risk they may pose to society. This security-oriented approach limits a broader understanding of the multiple ways in which a child’s life may be impacted when an immediate family member is involved in terrorism. To rectify this, this paper highlights the utility of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (EST) to systematically identify how this familial affiliation may impact the child’s life in diverse ways that extend beyond security-oriented outcomes. We demonstrate that EST is particularly useful because it allows us to systematically and holistically understand how the life of the child is impacted by familial association with a terrorist group in multiple spheres of their life (family, education, peer groups, etc.). We apply this approach to an example of a family who travelled to Syria in 2015 to join ISIS. This article demonstrates the utility of EST for researchers and practitioners to better understand the impact of familial involvement in terrorist groups on children moving away from more security-oriented approaches.

Introduction

“45,000 children of ISIS ‘are ticking time bomb’” states a 2019 headline in The Times, suggesting that children who have been affiliated to ISIS (largely through their family) pose an inherent risk to society (Kington Citation2019). Such statements are not uncommon, and present children linked to terrorist groups through a risk-oriented lens. In particular, this securitisation concerns children from families that became affiliated with ISIS between 2014 and 2019 and who were amongst the up to 52,000 foreigners who joined the terrorist group from around the world (J. Cook and Vale Citation2018).Footnote1 In Europe, hundreds, if not thousands, of ISIS-affiliated individuals and their families have now returned and largely comprise women and their children (J. Cook and Vale Citation2018; Mehra et al. Citation2024; The Foreign Terrorist Fighter Knowledge Hub Citation2023).

Beyond this, 1,566 persons have been arrested for terrorism-related offences in Europe between 2019 and 2021 (European Union Citation2022).Footnote2 That many of these individuals have children is frequently overlooked, and there is a gap in knowledge pertaining to how these children’s lives have been impacted by a family member’s association with terrorism. The well-being of children “affiliated” with violent extremist and terrorist groups through their families is a timely and pressing issue, particularly in policy circles and for practitioners working with these families.

Terrorism studies have often considered the status of these children in limited, security-oriented ways. There remains a significant knowledge gap on how the life of a child may be uniquely impacted when a family member is involved in violent extremism (VE) or terrorism.Footnote3 It is particularly important to recognise that children’s lives can be impacted in more complex ways than their inevitable radicalisation. Their familial affiliation can affect their relationships with peer groups, their education, and various environments and actors they are exposed to. This has not been systematically considered in the literature on children affiliated with terrorism.Footnote4 This limited focus impacts not only how children are viewed vis-à-vis terrorism, but it can also stifle the implementation of development-centric approaches to support them.

This paper proposes an interdisciplinary approach to research concerned with children of terrorism-affiliated families. We do so by applying Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (EST), a model used in studying child development, to terrorism studies. This model was developed to understand childhood development through an analysis of the impact of different social spheres and actors that a child engages with over time. We adapt this model to consider how a child’s life may be impacted in these different “social layers” when an immediate family member is involved in terrorism. By doing so, we demonstrate the benefit of focussing on the overall well-being of children in families affiliated with terrorism (specifically, their healthy development), rather than on the overall risk. Our analytical framework also allows for a consideration of potential risks of exploitation by terrorist groups, but it is designed primarily to assist in the development of child-oriented responses. In turn, drawing on this model can help de-securitise this population of children and generate a greater focus on well-being considerations and outcomes.

This article proceeds as follows: the first section defines key terms and reviews the literature on both children involved in armed groups and terrorism more generally, and on children affiliated with ISIS specifically, highlighting key gaps. Section two outlines the research design and introduces Bronfenbrenner’s EST as a conceptual framework for understanding the impact of family involvement in terrorist groups on child development. Section three applies Bronfenbrenner’s model to the case of an American family who travelled to Syria in 2015. In this family, a mother and (step-)father took two children to Syria, where two additional children were born. One of the children was forced to participate in ISIS propaganda which was broadcast around the world. Following the death of the husband, and the territorial defeat of ISIS in 2019, the mother and her four children ended up in al-Hol camp in Northeast Syria before they were repatriated to the US. The discussion and findings demonstrate how the entire life of a child can be impacted as a result of a family member’s involvement in terrorism, and that this impact goes well beyond their potential risk of radicalisation. The paper subsequently discusses the applicability of EST to the field of terrorism studies and concludes with directions for further research.

Terminology pertaining to children and terrorist groups

This section provides clarifications regarding several important definitions, and a consideration of how they are practically applied in our case study and analysis.

Terrorism and violent extremism

Both the academic field of terrorism studies, and terrorism legislation globally, lack terminological consistency, and to this day there is no consensus on the definition of terrorism (Schmid Citation2011). For simplicity, we refer to UN Resolution 1566 (2004), which defines terrorism as:

“ … criminal acts, including against civilians, committed with intent to cause death or serious bodily injury, or taking of hostages, with the purpose to provoke a state of terror in the general public or in a group of persons or particular persons, intimidate a population or compel a government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act, which constitute offences within the scope of and as defined in the international conventions and protocols relating to terrorism” (United Nations Security Council Citation2004). [italics our emphasis]

There is also no universally recognised definition of “violent extremism”, though it is generally associated with violent behaviour resulting from a process of radicalisation. The EU’s Crime Prevention Network defines violent extremism as “the position of an individual who actually has committed one or more acts of violence out of extremist considerations. It is used here as an equivalent to terrorism” (EUCPN, Citation2019). This definition supports a clear distinction between extremism of thought (often legally protected freedom of thought) and extremism of behaviour (often illegal or violent behaviour, and action) (Neumann Citation2013, 875). The focus of our paper exclusively lies on a distinctive category of children in families where an immediate relative promotes or engages in criminal acts as defined by the criminal code of that respective jurisdiction.

While we recognise that this category of children may share experiences with children raised in families who hold extremist views, but who do not engage in illegal extremism-motivated activities, the present paper is exclusively focused on family structures in which members have crossed a legally recognised criminal threshold.

Definition of the child

There is no universally accepted definition of a child, with widely diverse cultural and local understandings of childhood (Wessells Citation1997, 36) The UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) states that “a child means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier” (UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Citation1989). The term “youth” constitutes another sub-grouping, which generally refers to young people between 15–24 (Secretary-General’s Report to the General Assembly, A/36/2015 Citation1981). For this paper, we adhere to the UN’s definition of “child”; at the same time, we recognise that there are distinct legal and developmental implications for children belonging to the “youth” category. For example, youth are generally considered to have the ability to exert more agency in their decision-making processes. The following sections demonstrate that age is an important consideration when analysing how children are perceived in political discourses, and how they can actively manoeuvre their lives when their families are involved in terrorism.

Childhood as a political construct in warfare

A significant body of scholarship maintains that “childhood” cannot be understood merely in terms of the early stages of human development it also is a social and political construct (James and Prout Citation1990). This is particularly evident in the context of armed conflict, where children are not approached uniformly. Scholars have demonstrated that children are treated uniquely based on their features and that specific context, and revealed cases in which political actors did not acknowledge humans below the age of eighteen as children with distinct rights, in particular males involved in armed groups and children of “the enemy”. For example, Rosen describes the “politics of age” which shapes the concept of “childhood” and raises attention to how different parties may debate the concept of who is a child based on their own legal and political agendas (Rosen Citation2007). Shoker highlights how removing boys and military-age males from the collateral damage counts in US drone strikes made them eligible targets, and she raises questions about how exceptions to the protection of children may be based on “gender, race, age and religion” (Shoker Citation2021, 3). Research by Shalhoub-Kevorkian looks at Palestinian children and argues that they have been “unchilded” by the Israeli state, who construct “Palestinian children as dangerous entities,” and thus “violence against Palestinian childhood becomes part of the [Israeli] war machine” (Shalhoub-Kevorkian Citation2019, 16). Concerns about the treatment of boys associated with terrorist groups (specifically ISIS) have also been raised by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights who highlights the plight of boys in prisons in Northeast Syria. She notes that “They are tragically being neglected by the own countries through no fault of their own except they were born to individuals allegedly linked or associated with designated terrorist groups” (United Nations Human Rights Citation2022). This literature is important, because it draws attention to the need for scholars to consider how boys and girls of different ages and backgrounds may be uniquely viewed, approached, protected, or even punished when their own family is associated with terrorism.

Children’s agency

Both the fields of childhood studies and international relations are in a long-standing debate around portrayals of children’s agency, especially when they are subjected to or involved in political violence (White and Choudhury Citation2010; Denov and Akesson Citation2017). Research primarily concerned with childhood agency has generated invaluable insights into the lived experiences and resilience of child soldiers and addressed children’s own choices to join armed groups (Shepler Citation2014). However, regarding such engagement in violent groups, it has also led to polarised and often simplistic discourses of vulnerability/victimhood versus agency/participation (Cook et al. Citation2019; Punch Citation2020; Qvortrup Citation2009). Moreover, research on children’s agency in armed conflict rarely considers the impact of familial affiliation with such groups, especially when children are not actively involved themselves. We acknowledge that there is varying scope for these children to exercise agency in certain areas in their lives. At the same time, we believe that a predominant focus on agency (rather than on their social relationships more broadly) would limit our capacity to adequately capture these children’s complex experiences and development within this article. We therefore chose a broader framework that can help us understand the multiple ways in which a child’s life is impacted by family members’ involvement in terrorism, while still recognising the importance of interrogating children’s agency and resilience on an individual level.Footnote5

Child soldiers

Children associated with terrorists are often equated with child soldiers. While this term is primarily associated with children trained and used as combatants, a more recent definition includes “children associated with an armed force or armed group” more broadly. This category covers “any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, spies or for sexual purposes” (The Paris Principle Citation2007). The age of a child limits the criminal culpability and liability of children in judicial proceedings, including children associated with armed groups, recognising such children as victims of war, who are in need of certain protections, even in cases where they too may have been perpetrators.

Research frequently focuses on child soldiers in conflicts in countries such as Uganda (Derluyn Citation2004), Sierra Leone (Betancourt Citation2010), the Democratic Republic of Congo (Kelly, Branham, and Decker Citation2016; Rakisits Citation2008), Liberia (Malan Citation2000; Murphy Citation2003), Vietnam (Nguyen Citation2022), and Nepal (Kohrt et al. Citation2016), amongst others. These studies (a snapshot of the broader literature) generally consider children’s roles within these groups and more specifically, how these roles impacted them as children, and their pathway(s) to association, amongst others. Such a focus often emphasises how children could best be supported in rehabilitation programmes post-conflict. In Mozambique, long-term studies focused on the life outcomes of child soldiers provide useful findings on activities which best supported their long-term reintegration and survival (Boothby, Crawford, and Halperin Citation2006). Authors focused on child recruitment and armed roles note important distinctions between child soldiers and children in terrorist groups, particularly around the “microprocesses of recruitment”, which may account for differences in recruitment by armed groups or family members (Bloom and Horgan Citation2019). For example, Horgan et al. (Citation2017) consider how children are socialised into terrorist groups while Morris and Dunning (Citation2020) consider their recruitment. Yet, a research gap in such literature includes how children can be affected when their families are involved in terrorism, of which one (of many) possible outcome(s) could be related to facilitating their entry into armed groups (child soldiers) or their broader “affiliation”.

ISIS-affiliated children

The majority of research concerned with ISIS-affiliated children focuses on their roles as child soldiers. Bloom (Citation2019) provides nuanced accounts of the recruitment and indoctrination processes that ISIS-affiliated child soldiers were subjected to. Khoo and Brown (Citation2021) examine the role of children in ISIS propaganda and demonstrate that children’s primary reason to join the group is to ensure their survival, while Vale (Citation2022) considers how propaganda portrays child executioners in ISIS. Al Ibrahim (Citation2020) finds that ISIS propaganda primarily portrays children as violent and capable members of their group, which further reinforces the dominant perception of ISIS-affiliated children as child soldiers. While these studies are important to gain insight into the lived realities of ISIS child soldiers, they only concern the small number of boys (and even smaller number of girls) that were actually trained as soldiers and that were actively involved in the group’s activities (United States Attorney’s Office Citation2022). Yet, the range of experiences that children have as a result of their parents’ involvement in terrorist groups go well beyond those that child soldiers were exposed to.

There are only a few publications in the field of terrorism studies that examine the multitude of factors that shape the experiences of children exposed to terrorist organisations via their families. Cook and Vale (Citation2018, 29) note that age and gender differences significantly determine the experiences of children in the Islamic State who were taken by their parents from outside of Iraq and Syria. Although the authors find that younger children are more frequently considered as passive victims of their circumstances, and that boys and girls generally experience different forms of violence, they also note various exceptions, showing that children’s experiences are highly unique. In a similar vein, Brown provides a particularly nuanced account of the gender-related differences in the experiences of boys and girls living under ISIS and in camps in Syria. She finds that children face gender and age-specific vulnerabilities, with boys and girls displaying different symptoms of PTSD in response to their adverse childhood experiences (Brown Citation2021). Children from jihadist-affiliated families in the Netherlands have also been examined in relation to intergenerational transmission of ideology, noting that parents indeed can have a notable impact on their children’s ideology, but that there has been limited research on this topic (Wieringen et al. Citation2021).

Although a growing body of literature in the fields of child psychology and psychiatry examines approaches to rehabilitating and reintegrating ISIS-affiliated children (Klein et al. Citation2020, 149; Kizilhan Citation2019), Bunn et al. (Citation2023) note that the body of research concerned with the rehabilitation of children of ISIS-affiliated foreign fighters remains underdeveloped. The authors emphasise the multiple adversities that these children have experienced and argue that the management of child returnees should not be confined to security measures but also include interventions to address their health and psychological needs. Such studies are particularly important, because they acknowledge that ISIS-affiliated children have been exposed to a wide range of adversities that go beyond active involvement in terrorist activities. Related to this, there has also been an uptick in literature that analyses how children who have been involved in armed roles can be rehabilitated (Bunn et al. Citation2023; Ellis et al. Citation2023; Langer et al. Citation2020; Kizilhan Citation2019), and that considers their legal status (Anaie Citation2018; Brooks et al. Citation2021). Cook also considers the unique features of children affiliated to ISIS-linked families in Iraq, but who themselves were not child soldiers with ISIS (Cook Citation2023). Beyond the field of terrorism studies, there is a notable body of literature that looks at rehabilitating and reintegrating ISIS-affiliated children, largely in the fields of child psychology and psychiatry (Ellis et al. Citation2022; Klein et al. Citation2020; Weine et al. Citation2020). Challenges faced by ISIS-affiliated children, particularly in the post-war period, are also addressed in the field of law (Bradley Citation2017; Mustasaari Citation2020; Nyamutata Citation2020) and by NGOs who advocate for the rights of these children (Achiles, Nava, and Said Citation2022; Becker Citation2023; MSF Citation2022). This growing body of literature is largely driven by the sizeable international case load associated with ISIS.

The major shortcoming of this literature is its predominant focus on children’s roles in relation to their involvement in armed groups. It does not sufficiently consider the multiple broader experiences of these children associated with armed groups, nor does it capture the experiences of children whose parents are affiliated with these groups, but who are not actively involved in these groups themselves. Our case study addresses these gaps in two ways. First, we draw on the case of one family to highlight that while these children can indeed become “children associated with armed groups” through their familial affiliation, their lives are also affected in many other ways that can directly impact their healthy development. Second, we analyse cases of children within the same family, including one who had a more direct association with ISIS (child 1), and three who were not directly associated with the armed group (children 2, 3 and 4), to highlight the complexity of children’s very diverse experiences even within a single family. The next section discusses Bronfenbrenner’s model and its potential as a framework for interrogating how children’s lives may be more widely impacted when their family is affiliated with a terrorist group.

Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological model

Urie Bronfenbrenner was a developmental psychologist who focused on human development. In his EST, Bronfenbrenner proposed that beyond just psychological conditions, human development is impacted by different “systems” around it, which include social, cultural, and political systems. For Bronfenbrenner, the ecology of human development involves,

the scientific study of the progressive, mutual accommodation between an active, growing human being and the changing properties of the immediate settings in which, the developing person lives, as this process is affected by relation between these settings, and by the larger contexts in which they are embedded (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, 21).

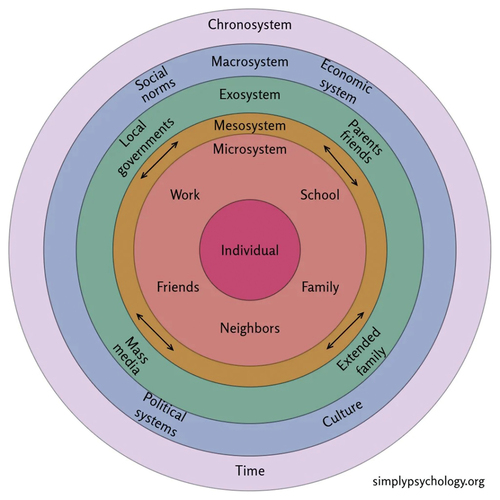

The socio-ecological model has several nested layers as seen in . These include the microsystem which entails those day-to-day settings in which a child engages in face-to-face interactions, and which captures particularly how they experience these interactions. The mesosystem comprises the “interrelations among two or more settings in which the developing person actively participates”, for example, how school, home and neighbourhood peer groups interact (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, 25). The exosystem refers to “one or more settings that do not involve the developing person as an active participant, but in which events occur that affect, or are affected by, what happens in the setting containing the developing person” (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, 25). This could include, for example, the parents’ network of friends, or local government activities. The macrosystem considers the more contextual factors that shape, but do not necessarily interact directly with, a child’s life: the culture, subculture, and the beliefs or ideologies which underpin it. Finally, the chronosystem considers changes or continuities over time, particularly as they relate to a person’s development (Bronfenbrenner Citation1986a, 724).

Figure 1. Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological model (Bronfenbrenner Citation1977, 513 as presented in Guy-Evans Citation2024).

We propose using Bronfenbrenner’s EST to identify how children’s lives may be uniquely impacted by their families’ affiliation with terrorism (Bronfenbrenner Citation1977, Citation1986a; Citation1986b, 1992). We argue that the impacts and implications of familial involvement in terrorism on the life of a child cannot be assessed in isolation. A child’s entire environment can be directly impacted by their family members’ active involvement in terrorism. Family members may take them to a conflict zone or a local terrorist network, expose them only to certain terrorist-affiliated peer networks or communities, or to environments (rallies, camps, educational institutions, and other locations) that may be directly related to an ideology. Their parent may be in prison for a related crime, or face employment restrictions based on their profile and have difficulty paying the bills. In such cases, children are affected in different areas of their life as a direct result of their family member’s affiliation with a terrorist group.

Thus, their entire world, and their development within that world, can be impacted on several levels, not only within the child’s direct family environment, but also by their families’ engagement with the wider world. Adopting the main principles of Bronfenbrenner’s EST allows us to consider these specific implications on multiple levels – the individual, family, and broader community, and societal level. As Stokols notes, “An ecological perspective offers a way to simultaneously emphasise both individual and contextual systems and the interdependent relations between these two systems” (Stokols Citation1996). It is thus helpful to look at not only the individual situation of the child, but how the familial association with terrorism may impact their life situation (and key areas such as their development) on multiple levels. Furthermore, while Bronfenbrenner’s EST is not primarily concerned with children’s agency, it provides a helpful framework for understanding how generational relations are impacted by a family’s affiliation with terrorism, and how this shapes children’s experiences. The framework can therefore also be used by scholars to examine how relationships between family members affiliated with terrorism and children impact: 1) a child’s perception of agency; 2) the ability to exercise real agency; and 3) the prevalence of restrictions on children’s agency in multiple social contexts.

Bronfenbrenner in related fields

A significant body of scholarship already utilises Bronfenbrenner’s theory to look at children in the context of fragile life situations, including in political violence. According to Bloom and Horgan, scholars may highlight EST as a useful tool for supporting child soldiers involved with terrorist groups, but which may have to be reconsidered in cases where the family (micro-system) may be involved in the recruitment of their children (Bloom and Horgan Citation2019, 178). However, the use of EST as applied to children affiliated with terrorist groups is much more limited, and predominantly focuses on their radicalisation. Ellis et al. (Citation2022) highlights the need for multi-disciplinary approaches to researching radicalisation and notes that Bronfenbrenner’s model “can be particularly useful in considering how the interplay of multiple factors may shape youth development and, for some, result in violent radicalization” (Ellis et al. Citation2022, 1322). The authors apply EST to individual cases of youth identified as vulnerable to radicalisation, profiles them for relevant vulnerabilities at all levels, and discusses the multi-agency interventions that were adopted for each case (Ellis et al. Citation2022).

A small number of publications on terrorism draw on Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model (Ehiane Citation2021; Nivette et al. Citation2021; Taylor and Soni Citation2017). Cook (Citation2023) uses EST to consider the unique features of children affiliated to ISIS-linked families in Iraq, but who themselves were not child soldiers, and demonstrates the myriad of ways in which these children’s lives are negatively affected due to their familial links to ISIS. Cummings et al. examine the effects of political violence on families and children in Northern Ireland and note that “more needs to be understood about bidirectional relations between political violence and children’s functioning, including the associations between children’s attitudes and behaviours in these contexts and family, community and political conflict and violence” (Cummings et al. Citation2009). Cardeli et al. (Citation2022) use EST to look more explicitly at children coerced into violence, specifically by gangs and terrorist groups (Cardeli et al. Citation2022). They note that “Bronfenbrenner’s [EST] offers a useful framework for understanding the various personal, social, and cultural factors that might give rise to a child’s involvement in violent groups” (Cardeli et al. Citation2022, 321). The authors highlight gaps in the field where there has been “little integration of [Bronfenbrenner’s model] into terrorism studies even though the field has increasingly recognised the value of ecological models”. However, Cardeli et al. do not consider more broadly how a child’s life is impacted when their family is involved in terrorism, which in some cases may result in their involvement in violence, and in other cases does not. Yet, they usefully concur that “efforts to understand children’s involvement in violent groups may benefit from assessing factors across various levels of the social ecology and examining the ways in which these factors work together to promote or prevent risk” (Cardeli et al. Citation2022, 331).

EST has also been applied in adjacent fields, including in research on children in gangs (Goodrum et al. Citation2015; Hong Citation2010), children of immigrants (Paat Citation2013; Goodrum et al. Citation2015), and children in religious families (Loser et al. Citation2008), offering some insights as to the model’s relevance and application to our target group, which may have overlapping features with children in these other categories of children. These articles focus on the implications for children’s developmental outcomes. Additionally, public health approaches proposed in preventing/countering violent extremism (P/CVE) have considered the impact of environments on multiple levels (Weine et al. Citation2017). This review suggests that Bronfenbrenner’s EST may be a particularly promising framework for identifying how children are affected when their family is involved in terrorism.

Methodology

The present research draws on a qualitative case study of an American family that travelled to Syria in 2015 and became affiliated with ISIS to demonstrate the applicability of EST to gain a more nuanced understanding of the ways parental involvement in terrorist organisations can impact a child’s life. According to George and Bennett (Citation2005), case studies are useful for documenting “complex interactions” through process tracing and are particularly suitable for exploratory studies of individuals or groups in a unique context and allow for the generation of rich descriptions and explanations, and in-depth insights (Yin Citation2009). We selected this family because of the availability of rich and detailed, publicly accessible information about their lives, and thus the ability to gain a nuanced understanding of how their family involvement impacted the lives of these children. A case study refers to a “class of events” that can be a “phenomenon of scientific interest” with the aim of developing theory regarding the “causes of similarities or differences among instances (cases) of that class of events” (George and Bennett Citation2005, 17–18). Our case study is used to investigate a class of events (children affiliated to a terrorist group through familial links) which can further help us understand how this case may be similar or distinct to other children in families affiliated to terrorist groups in future research.

Qualitative case studies do not necessarily provide clarity on how much certain factors contribute to an outcome. For example, to what extent is a negative (or positive) developmental outcome for a child based exclusively on that family member’s involvement in terrorism? Case studies are indeed stronger at assessing “whether and how a variable mattered to the outcome than at assessing how much it mattered” (George and Bennett Citation2005, 25). However, we can determine whether familial affiliation with a terrorist group did in fact impact the lives of these children, and describe how they were impacted in this case. We call for further research on this topic at the end of the paper, specifically in relation to conjunctions of factors – are these necessary and/or sufficient for an outcome (George and Bennett Citation2005, 26)?

We systematically collected open-source data pertaining to our case study using two databases: LexisNexis and the Google search engine. This included newspaper articles, documentaries, podcast, video footage, ISIS propaganda videos, government statements, and court dockets related to the case of the family. We further conducted a systematic keyword search that included all known family members’ names, as well as the terms “Islamic State”, “terrorism”, “terrorist groups”, and “ISIS”.

In accordance with the analytical process outlined by Bowen (Citation2009, 27–40), the selected sources were examined, coded, and categorised, and themes were uncovered. First, we familiarised ourselves with the data by reviewing all materials and took notes and identified patterns and themes that emerged from the data. Bowen’s second step requires the researcher to develop a coding system or thematic framework to organise the collected data. We relied on the five layers in Bronfenbrenner’s EST to organise factors that were likely to affect child development (discussed in more detail below).

The next step in our data analysis process involved the indexing of data. Here, the thematic framework was applied to the data by systematically indexing all information in accordance with the relevant theme (Bowen Citation2009). We followed a two-step process to group our information according to the five levels or systems that impact child development. In our first step, we developed a timeline of all documented life changes that have occurred for the family. This timeline enabled us to structure the collected information systematically, in accordance with Bronfenbrenner’s chronosystem. In the next step, we grouped the available data on each of the events outlined in the chronosystem into the other levels outlined in Bronfenbrenner’s EST. After coding the data, we interpreted the available information by analysing the relationships, themes, and patterns that emerged from the data. We present our data analysis in a narrative form as a chronological story of the lives of these children, to provide a holistic overview of the ways in which their lives were impacted by their parents’ affiliation with ISIS.

Guiding questions deriving from the application of EST to case studies

Integrating EST as a conceptual framework in our case study design prompted us to generate a list of guiding questions. These could help researchers to gather and analyse relevant data on how children may be uniquely impacted in terrorist-affiliated families more generally, and to further consider the developmental impacts on those children on different levels.

Microsystem

In the family, who is in the immediate environment of the child? Who is involved in terrorism? Who is not?

How/does familial involvement in terrorism directly impact the immediate relationships and environment of the child?

Who are the other immediate people in that child’s life, and where do they encounter them?

What are the characteristics that define the relationship between the child and these immediate people? For example, are these people sources of abuse, subordination, and indoctrination, or of comfort, protection, and care?

Mesosystem

How are relationships between key actors in the child’s life impacted by a family member’s involvement in terrorism?

What implications does this have for the child? How does this impact the child?

Exosystem

How are the family’s networks and relationships (which the child is not directly involved in) related to, or impacted by, their involvement in terrorism?

How/do these relationships impact the child?

Macrosystem

What are the characteristics of the larger social and cultural context in which the child lives, particularly vis-à-vis that terrorist group or ideology?

What are the economic and political systems, and legal frameworks where the child lives? How do these affect persons that are involved in terrorism, and how actors associated with that group may be regarded or interacted with?

Chronosystem

What are the major life-changing events (particularly those linked to terrorist activities) that shaped the child’s environments over time?

How old is the child at the times of these events? What is known about their stage of development at that time?

General questions:

How does the ideology present affect any of the above (e.g. whether religious, left- or right-wing ideology, or other)?

What are the risk and protective factors visible in each layer?

How do age, gender, developmental and other related features impact the child at each level?

Did the family stay within their home community, or travel to another community, and what are the implications of this (e.g. foreign travel vs. domestic travel vs. no travel)? This may consider implications of travel to conflict zones, for example, where terrorist groups hold and administer territory.

Limitations

Applying a theoretical framework from the field of child development to the field of terrorism studies poses certain limitations. Scholars in terrorism studies are usually not trained child psychologists. This means that we can describe the ways in which a child’s life is impacted, and how that is linked to the family member’s relationship with that ideology/group, but not necessarily how those events directly determine specific developmental outcomes for that child. Furthermore, current research lacks a quantitative basis to determine the most common experiences of children in families affiliated with terrorism (e.g. what percentage may be trained in some way for defence or combat, or how many have family members in prison, etc.). However, we believe that the proposed approach remains helpful for terrorism scholars to think more holistically and systematically about how children are impacted by familial involvement in terrorism, and that this approach promotes more interdisciplinary research between terrorism studies and fields such as child psychology or social work. We also consulted frequently with professionals including child psychologists, social workers, project partners, advisory board members with interdisciplinary backgrounds, and an ethics advisor linked to the project to assess the utility and application of this approach (see disclaimer).

We also considered the possibility that the use of open-source data could pose ethical challenges related to upholding principles of privacy and confidentiality, especially in cases where children and vulnerable populations are included. As a result of the wealth of information that is publicly available about this family, it was not possible for the research team to ensure their confidentiality in this paper. However, we decided not to use the name of the family in this paper to minimise to the greatest extent possible further coverage and scrutiny of the children.

Another limitation of open-source data is that the information was collected for a specific purpose which may differ from that of the researchers. Most of the publicly available information centres around the mother. While this information provides us with invaluable data on key factors that impact her children’s lives, the data is not primarily focused on the children’s development and experiences. Moreover, US laws protect the identity of minors, which means there is very little information on the younger children in this family. Working with incomplete or limited data can exacerbate the risk of bias in data analysis, which can lead to incorrect conclusions. We were transparent about the areas in which crucial information is missing and avoided overanalysing the available data.

Case study – the family

In what follows we will present our findings related to the ISIS-affiliated family in chronological order of their travel. The immediate family comprised the mother, husband (stepfather to child 1, biological father of children 2, 3 and 4), child 1 (male, oldest), child 2 (female, second oldest), child 3 (male, third oldest), and child 4 (female, fourth oldest). The mother and her husband travelled to Syria with child 1 and 2, while children 3 and 4 were born in Syria.

Before travel to Syria (−2015)

Microlevel considerations

In 2012 in the US, two years after his parents separated, child 1 and his mother moved to a different state, and his mother married the man who would later travel with the family to Syria to join ISIS (Baker Citation2020b). Initially, the husband was described as a Muslim who would occasionally pray, but who “seemed very relaxed with things”. The family lived in a large suburban house (Baker Citation2020b). Child 1’s father lived several states away, and although their relationship is described as loving, they did not see each other frequently (Baker Citation2020c), Child 1 developed what appears to be a close relationship with his stepfather. A video shows the boy thanking his stepfather for gifting him a new bike in which the stepfather responds: “You’re welcome, buddy, you’re my best friend”. In addition to the mother and her husband, child 1 also spent time with his maternal aunt, who lived half an hour away from the family and who took child 1 to the zoo (Baker Citation2020b). A year after their marriage, child 2 was born (Baker Citation2020b). The mother was described as “always interacting with the kids, playing with them”. According to her friends, the children “were very well cared for” and the mother “was amazing with the kids” (Baker Citation2020a).

The family’s affiliation with ISIS was not apparent for most of the children’s lives in the US, and therefore their relationships with their immediate contact person did not appear to be impacted by the parents’ involvement in terrorism. Child 1’s interaction with his maternal aunt became limited because she increasingly did not approve of his stepfather and had a falling out with the children’s mother, but at that time the stepfather had not yet been openly affiliated with ISIS (Baker Citation2020a). He had a reputation for “disappearing for days on cocaine binges”, which may constitute a risk factor for radicalisation; however there are no documented indications of religious extremism before 2014 (Baker Citation2020b). The stepfather also begins to take child 1 to a local shooting range, though it is not clear if this is in anticipation of going to Syria (Roy Citation2019b).

Meso-level considerations

The family initially gave the impression of a happy home, and the mother and her husband had a close relationship. The couple also worked together in the husband’s family business. The husband was described as caring and generous, providing his wife with luxury items like expensive cars (Baker Citation2020d). At the same time, the mother later revealed that the relationship was emotionally abusive and tainted by her husband’s drug abuse and infidelity, followed by his increasing radicalisation. The mother reported that the emotional abuse she experienced in this relationship had been a contributing factor for her choice to support her husbands’ decision to move to Syria. Her husband’s involvement in ISIS led her to make secret travel arrangements in 2014 and 2015 to deposit money and gold in Hong Kong (Baker Citation2021e). Although her husband “introduced the idea of wanting to join ISIS to his wife” over Thanksgiving in 2014, the mother maintained that the husband had been deceitful about his intentions to join ISIS (UNISET Canada Citation2022). The mother explained that the abusive and deceitful relationship between her and her husband led her to take her children to travel with him. But she also lied to other key individuals in child 1’s life, which meant that they were unaware and unable to prevent the children from travelling to Syria. Deceived by the mother, child 1’s paternal father even signed the documents required to obtain the passport child 1 needed to travel (Baker Citation2021b) Consequently, children 1 and 2 were taken to ISIS-occupied Syria by their mother and her husband.

The husband’s involvement in terrorism impacted the family’s networks and relationships only to a limited extent before moving to Syria. However, he had five brothers and he discussed ISIS and watched propaganda videos with at least two of them. While one of the brothers distanced himself from his brother’s ISIS-sympathising behaviour and asked him to stop watching propaganda, another brother shared the husband’s ideology (Baker Citation2021b). While the husband did not show any clear signs of violent extremist radicalisation prior to their departure, his brother “openly discussed his support for ISIS before travelling to Syria”. The brother also sent various emails about ISIS to the husband and the mother (his sister-in-law), and other family members. The mother confirmed that her husband’s brother was “far more radicalised”, and “ultimately swayed his brother to follow him to Syria, beginning most likely in November 2014” when the brother visited the husband in his hometown (UNISET Canada, Citation2022).

Exolevel considerations

There is reason to suspect that members of the husband’s family may have supported terrorism before the two brothers decided to move to Syria to join ISIS. The family’s shipping company had been under the suspicion of transporting goods used by terrorist organisations. This had an indirect, yet far-reaching impact on the lives of the children because the FBI asked their mother to become an informant and to report on activities in the company that could aid their investigation. When the couple prepared for their departure from the US, the mother lied to the FBI about their travel reasons, which ultimately led, in part, to her imprisonment upon return from ISIS and impacted her sentencing (Baker Citation2021b). While their mother’s relationship with the FBI did not appear to directly impact the children’s lives before travelling to Syria, it impacted her sentencing and thus separation of her from her children when they returned.

ISIS announced its so-called caliphate in spring 2014, and by the fall of that year, had undertaken a genocidal campaign in Sinjar against the Yazidis prompting an international coalition to intervene. By 2014, ISIS was holding and administering an area the size of Britain, imposing its strict interpretation of Islamic law, and highlighting life in the “caliphate” in high quality propaganda, which was easily accessible across the internet. For example, between September and December 2014, “at least 46,000 Twitter accounts were used by ISIS supporters” and “almost one in five ISIS supporters selected English as their primary language when using Twitter” (Berger and Morgan Citation2015). Governments around the world were also taking steps at this time to prevent their citizens from travelling to Iraq and Syria and the group and its members were internationally condemned.

Macrolevel considerations

Radicalisation is a complex issue that can occur in various contexts for various reasons. The data does not allow for a nuanced analysis of how macro-level characteristics may have affected this family. However, there are a range of factors that are recognised to be conducive to fostering feelings of marginalisation, discrimination, and grievances, which in turn are considered conditions that extremists exploit for recruitment. In the case of ISIS travellers, these included grievances including experiences of Islamophobia, and real and perceived profiling and discrimination of Muslim individuals and communities, and ambitions to live in a utopian “Islamic” state, amongst many others. Due to limited data, it is not possible to evaluate what macro-level factors affected this family, or how. However, in an email to one of his brothers, the husband maintained that the factors contributing to his decision to join ISIS included cold weather-related health issues and disillusionment over his costly and unsuccessful immigration process: “the reason why I left was because I was really tired of being illegal” (UNISET Canada, Citation2022) which may speak to the broader context the family lived in (environment, immigration policy).

Chronolevel considerations

Prior to moving to ISIS, the children did not experience any major life-changing events that were a direct result of their parent’s affiliation to ISIS. Major occurrences in the life of their mother were associated with proactively preparing for a new life abroad. This included the liquidation of all the family’s assets, lying to friends and family, their mother working with the FBI, and obtaining travel documentation for her children.

Time in Syria (2015–2018)

By May 2015, the family had travelled to Turkey, crossed the border, and entered Syria with a then seven-year-old male (child 1), a two-year-old female (child 2), the mother and husband, and the husband’s brother (UNISET Canada, Citation2022; United States Department of Justice Citation2020). Two more children were later born in Syria in 2015 (child 3, male) and 2017 (child 4, female).

Microlevel considerations

Upon arrival, the mother stayed at a “guest house” for women and children with child 1 and 2 and other newly arrived ISIS-affiliated families (Roy Citation2019a). Here, the family would have lived and interacted with other ISIS-affiliated families from around the world. However, details about their experience here are unknown. Meanwhile, the husband trained with ISIS as a sniper and was thus absent immediately after their arrival. The whole family eventually settled in Raqqa, which was the ISIS capital in Syria at the time (Childress and Baker Citation2022). The family moved to a large house on the edges of the city. The house is described as beautiful and spacious, and adequate for a high-ranking ISIS member – suggesting that the initial level of comfort for the family would have been linked to the father’s status in ISIS (Baker Citation2021c). The children had a lot of space to play, and lived next to the river where they went swimming.

At first, the mother spent all her time at home with her children. During this time, children 1 and 2 had a very close relationship with their mother, and child 1 recalled having a lot of playtime and good food. However, in 2015, the mother was arrested by ISIS and detained for two and a half months under suspicion of spying for the US. When she was detained, the children witnessed the door get kicked in and they were blindfolded (Childress and Baker Citation2022). During their mother’s imprisonment, it is unclear who took care of the children or what their experience was in this time.

Moving to Syria thus caused various changes in the children’s microsystem. Child 1 was no longer in frequent contact with his biological father, and none of the children were in contact with their maternal aunt and grandparents. Living under ISIS introduced the children to several new individuals who were present in their daily life. In 2015, the mother and her husband purchased an enslaved Yazidi boy, with whom child 1 developed a strong emotional bond. He recalled that the children “were like brothers” (Childress and Baker Citation2022). According to Lamb (Citation2018) the boy later expressed the wish to see him and his mother, and even to move to America with them.

The husband and mother also bought two enslaved Yazidi girls aged 14 and 15. The mother told the older girl that “she was going to be like (her) daughter”, yet they were forced to do domestic labour and were frequently raped by the husband (Childress and Baker Citation2022). While not much is known about the relationship between the children and the younger Yazidi girl, the older Yazidi girl developed a very close and loving relationship with child 1. They taught each other their native languages, but that also meant that child 1 had to translate to her that she was going to be raped by his stepfather. While the mother maintained that child 1 was unable to understand the context at that time, a documentary featuring the child contradicts this. It was also noted that the husband physically assaulted the pregnant mother in the home (Baker Citation2020e). Thus, the children were exposed to domestic abuse against both their mother, and the enslaved persons in their household, with whom they developed emotional bonds.

Records show that the mother did not appear to have sent child 1 and 2 to an ISIS school and tried to shield them from ISIS exposure. Ultimately, she was unable to protect her children from the violent ideology and activities of the group, not least because of her husband’s active role in ISIS. Child 1’s relationship with his stepfather changed significantly in Syria. Early pictures showed the family playing and swimming together in a river, reflecting a positive relationship. Yet, for prolonged periods, the husband was absent due to training and fighting missions. The husband also started to threaten and physically abuse child 1 who later described him as mentally unstable, and feared and obeyed him. The husband frequently exposed all members of the household to terrorist propaganda and violence by forcing them to watch ISIS’ TV channel, which the mother could not prevent. She was moreover unable to protect child 1 and the Yazidi boy from receiving weapons training and from being exploited by her husband, his brother, and other ISIS members for propaganda purposes. In this context, she even assumed an active part by filming him assembling a suicide vest in 2017. In turn, child 1 increasingly lost faith in his mother, who frequently told him that they were going home, but at one point he stopped believing her (Baker Citation2021a). Child 1 also recalled being afraid of saying the wrong thing, being acutely aware of how easily he could be killed and disclosed that ISIS members threatened to kill the boys if they did not cooperate in the propaganda (Childress and Baker Citation2022). On at least one occasion child 1 returned home crying in the evenings after being forced to participate in ISIS propaganda and told his mother that his uncle treated him badly when he forgot his lines (Baker Citation2020e). It is unclear whether child 1 and the Yazidi boy were exclusively trained by child 1’s stepfather and step-uncle or if they had also been exposed to other ISIS members. Moreover, beyond forming a close friendship with each other, it is not known whether the two boys interacted with other children outside of the household. In their first house by the river, neighbours were not affiliated with ISIS, and there is evidence of interaction as adults and other children remember child 1 and his name.

The husband was ultimately killed in a drone strike in 2017 – a significant life experience for the whole family. Both the mother and child 1 independently stated that members of their household were happy about the husband’s death, and child 1 explained that they “were all crying out of joy” (Baker Citation2021a). It is not known how the younger children in the family experienced the death of their father, though this likely had some impact. After this, the family moved to another house in Raqqa with the husband’s brother, but eventually escaped with a people smuggler to Deir ez-Zor. During the escape journey, the children hid in barrels in the back of a truck. The family had to clear multiple ISIS checkpoints, where if caught, they may have been killed, a likely terrifying experience for children. The three Yazidi children were ultimately sent to Kurdish forces by the mother and freed. By November 2017, the mother and her four children were in the custody of Kurdish forces, who eventually transferred them to al-Roj camp in Northeast Syria, where they stayed until July 2018 (Childress and Baker Citation2022). At this time, their living conditions in the camp were dire, with outbreaks of tuberculosis and hepatitis, which the mother and child 3 contracted, while child 3 and child 4 were reportedly malnourished (Roy Citation2019b). Little is known about the interactions between the children and other families in the camp. However, the mother reported positive interactions between child 1 and camp guards, who helped him to retrieve his ball from beyond the fence and who drank tea with the child (Baker Citation2020e).

Mesolevel considerations

Following her detention in an ISIS prison in 2015, and after being brought in front of ISIS judges with her husband, the relationship between the mother and her husband broke down, even though he seemed to have lobbied for her release (Roy Citation2019b). Since moving to Syria, the husband became increasingly physically abusive towards his wife. He also lied to her about the intention of the videos that she took of child 1 assembling a suicide vest. He told her they were made to convince their family to send them money to get them out of Syria, when in fact he tried to exploit the family financially to support ISIS. After her release from prison, the mother noted she “couldn’t stand looking at him” anymore (Baker Citation2020e).

Relationships that existed in the US were largely cut off when the family moved to Syria. There is no contact recorded between the mother and her parents, her sister, or child 1’s biological father until 2017. However, it is evident that the lives of the mother’s broader family were impacted by her affiliation with ISIS. From 2017 onwards, they became involved in her life again, spoke occasionally with the mother and tried to help her and her children to exit Syria. This was particularly supported by the mother’s sister, who was able to build a relationship with the children through online communication (Childress and Baker Citation2022). The mother reportedly requested money from her sister to facilitate a human smuggler in 2017, and she quit her job to try and focus exclusively on the mother’s case, including advocating for her with local politicians and various US security forces. The sister also eventually became an FBI informant in the mother’s case (Roy Citation2019b). Moreover, there is evidence that the husband’s family was impacted by the two brothers’ decision to join ISIS. For example, one of their brothers was denied naturalisation in the US because of his siblings’ ISIS affiliation. He appealed this decision, arguing that his “brothers’ actions are not a basis to deny (his) naturalisation” (UNISET Canada Citation2022).

Exolevel considerations

Child 1 and the Yazidi boy were heavily featured in the international media because of their forced participation in ISIS propaganda videos, in which the US President was threatened, which received extensive media attention around the world. In these videos the images of the children were shown, meaning that they would have been easily identified (Lamb Citation2018). Child 1’s association with ISIS, and his featuring in the propaganda video, were directly facilitated by the parents (Childress and Baker Citation2022). In an interview, a journalist noted to the mother, “A lot of people will look at that video, and they will see [child 1] as a threat to Americans. They will see a kid that knows how to use weapons, apparently, that maybe knows how to use a bomb”. She agreed (Baker Citation2018).

The extent to which the mother was affiliated with ISIS remains a controversy. However, various individuals, including the older Yazidi girl and the family’s neighbours in Syria, maintained that she was not part of the group (Baker Citation2021e). During her imprisonment by ISIS, the mother experienced torture and rape, which would have deeply affected her (Childress and Baker Citation2022). Journalists gathered compelling evidence which suggests that the husband was a very well-known ISIS commander, and part of a notorious unit of elite ISIS fighters. His boss was believed to be Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, ISIS spokesperson, leader of their external operations and the group’s second in command. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the husband travelled to see al-Adnani to tell him about his wife’s imprisonment Although it was impossible to verify this, it is assumed that al-Adnani helped the husband to get his wife out of prison (Baker Citation2021c).

Macrolevel considerations

Throughout the period of 2015–2018, the war against ISIS intensified significantly. Raqqa was retaken by Kurdish-led forces in October 2017 and the final territorial defeat ultimately occurred in Baghouz, Syria in early 2019. In this period, persons residing in Syria, including this family, were exposed to an active conflict zone including aerial bombardments, fighting, and public executions and punishments in areas held by ISIS. In their home countries, as well as in other western countries, attacks conducted by individuals inspired by or directly linked to ISIS killed hundreds of people. This increased fear of the group and public intolerance for persons who joined ISIS. Foreigners who were captured in Syria and Iraq at this time were largely directed to local prisons in the case of adult males and adolescents, and camps (al-Hol and al-Roj specifically) in the case of women and children. Debates were occurring in the respective home countries about whether to repatriate these individuals, with frequent cases of public frustration and anger at government efforts to return their ISIS-affiliated citizens. The US became one of the few countries that actively advocated for this, bringing their own citizens home, and supporting other countries in their repatriation efforts – ultimately facilitating the return of this family.

Chronolevel considerations

The children’s lives in Syria were characterised by instability and various life-changing events. Moving to the ISIS-occupied city of Raqqa caused a drastic change in the living conditions and social structures of child 1 and child 2. In Syria, all children were exposed to unstable and frequently changing contact persons and accommodations. The children experienced separation from their mother and from the three Yazidi children with whom they lived with for several years, and the death of their (step)father. The children were also impacted by drastically declining economic conditions as a result of living in a war zone. Upon arrival, the family lived in relative prosperity (Baker Citation2020d), but over a short period of less than three years, they witnessed the destruction of their “home” by bombs and supply shortages that forced them to scavenge for food (Baker Citation2021a). Eventually, the family fled and were transferred to various detention settings before settling in al-Roj camp for eight months (Baker Citation2021).

Returning home (2018–2023)

In July 2018, the mother and her four children were repatriated by the US government and the mother faced trial in the US.

Microlevel considerations

Upon return to the US, the mother was taken into custody and sentenced to 78 months in prison and was thus separated from her children (United States Department of Justice Citation2020). Upon return to the US, the children were taken into care by child protective services (Childress and Baker Citation2022). The three youngest children eventually moved in with their mother’s parents (the children’s grandparents), although the mother’s sister also wanted custody of the kids (Childress and Baker Citation2022; Roy Citation2019b). At their grandparents, the three younger children live in a safe family environment with a large outdoor space and ample opportunities to play. According to their grandparents, the oldest girl seemed distanced at the beginning, but the two younger children immediately bonded with the grandparents. All three children appeared talkative and happy; however the grandparents reported signs of PTSD in the older girl, who thought they were being bombed when their neighbours set off a firework on Independence Day. She was also able to differentiate between the sound of fireworks and guns, suggesting that she had been extensively exposed to explosions and gun shots in Syria (Baker Citation2021a).

Child 1 received counselling and moved in with his biological father upon return, which means that the siblings were separated, but also that child 1 received the necessary support (Childress and Baker Citation2022). Today he remains in contact with his siblings and grandparents and visits them semi-regularly (Baker Citation2020b). It is unclear to what extent the children are in contact with their imprisoned mother, but it is likely that they and their grandparents are interacting with her to some degree. When child 1 spoke about his experience with ISIS with his dad by his side, he noted that “not all kids want to do that … a lot of the time they’re forced” and made a public plea to try and reduce the perceived threat of children who had no choice in their involvement in ISIS (Childress and Baker Citation2022). The child likely remains recognisable in public today, and it is not clear how his experience in Syria impacts areas such as school attendance, his peer groups, or other close relationships in his life.

Mesolevel considerations

Much of the media attention on the family upon their return to the US focused on the court case of the mother. It was reported that their mother suffered from PTSD and was taking medication (Roy Citation2019b). The mother was eventually charged with conspiring to provide material support for terrorism and aiding and abetting to provide material support (United States Department of Justice Citation2018). Child protective services worked with the grandparents at this time to arrange a living situation for the three youngest children, and for child 1 to live with his father and the presence of family structures upon their return appears to be a protective factor for these children. The trial of the mother would have also impacted all persons in this family – grandparents, sister, and children, some of which attended her trial. The family was also exposed to increased public interest and scrutiny due to the high-profile status of the mother’s case, which may have resulted in stigmatisation of the family.

Exolevel considerations

Their mother’s imprisonment for supporting terrorism and the deceased (step)father’s status as a terrorist likely led to social stigma. More generally, the issue of ISIS-affiliated returnees remains an on-going issue which often comes up in the news. Public attitudes to child returnees also appear to be softening, even though headlines discussing children as “ticking time bombs” and ongoing threats continue, particularly in relation to children remaining in camps in Northeast Syria.

Macrolevel considerations

Countries around the world have established rehabilitation and reintegration programmes for returnees, which returnees are generally required to go through, though not in the US. There have thus far been limited recorded instances of returnee adult women or returnee children being involved in terrorism-related incidents which may build up some level in trust generally around return processes.

Chronolevel considerations

The children’s experience of returning to the US and the subsequent imprisonment of their mother represents a significant life event for the children. Living with their grandparents meant that children 2, 3 and 4 went through a notable adjustment phase. Child 2 was very young when taken to Syria, and children 3 and 4 never lived in the US before. None of them had a close relationship with their grandparents before living with them. In contrast, child 1 remembered life in the US and lived with his father, with whom he already had a close relationship. Over time children 2, 3 and 4 may require age-appropriate explanations about their mother and deceased father’s situation. All children may also require opportunities to maintain a relationship with their mother. The chronosystem also includes the possible transition of their mother back into her children’s lives upon her release in the future. This may introduce additional adjustments and challenges for the children.

Discussion

The case above highlights the multiple and diverse ways in which children in this family were impacted by their parents’ involvement in ISIS. The people they were exposed to in their day-to-day life at the micro-level evolved from family members in their home country, to persons enslaved in their home, and ISIS fighters. The children also experienced the loss of their (step)father who died while fighting for the group, and who had been increasingly abusive and exploitative before his death. Upon returning home, the ultimate separation of siblings, and a mother in prison, meant that they now live with family members they had not seen in several years or ever met, but also returned to a seemingly safe and stable environment. At the meso- and exolevels, the interactions of those around them directly impacted their lives – through an increasingly abusive and violent relationship between the parents, a husband abusing slaves held in their home, a mother being detained and tortured by fellow members of ISIS, and an aunt back in their home country who was trying to help secure their escape by working with law enforcement agencies. At a macro-level, increasing legal, political, and military responses to ISIS impacted the family and children, including their ultimate repatriation, as well as the perception of the family both while in Syria and upon their return home. The experiences of the children were also very much affected by their age and gender. As the older siblings, Child 1 and Child 2 had interactions and relationships with non-extremist family members and other individuals than those of his siblings prior to travel, which likely affected their return home and ease of reintegration and provided a protective factor. Due to his older age and because he was a boy, Child 1 was significantly more exposed to dangerous activities. He was forced to interact with weapons and terrorists, and he was sent on dangerous food searches, while the younger siblings spent their time primarily at home.

This case highlights the many diverse ways that these children’s lives were impacted on multiple levels based on their family’s affiliation with ISIS. These impacts extend far beyond more simplistic labels of being a “ticking time bomb” or at risk of radicalisation, and capture a complex set of experiences, risks, and resilience factors (based on available information). The application of EST to cases in future research could allow for a targeted identification of risks and resilience factors at the level of each child, and the unique considerations that would be applicable to each based on their age, gender, and level of development.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates the utility of EST to better map and understand the ways in which children’s lives are affected when their family is affiliated with terrorism. We find that utilising this conceptual framework in terrorism studies opens novel avenues for multi-disciplinary work, especially with scholars in the fields of child psychology, and social work. As demonstrated in this paper, a multidisciplinary approach facilitates a better understanding of the individual life experiences of children involved in terrorist groups. Research from other fields also highlights the importance of considering aspects such as agency of these children, or how children may be viewed or treated based on their profile (age, gender, race, etc.), including in legal and security contexts.

There are other fields which also highlight overlapping ideological, social, and experiential features which may be considered in future research. These include extremists or cults, which may share aspects of the ideological indoctrination and commitment, and social dynamics. Examining right-wing extremist communities in rural Germany as part of the EU-funded PREPARE project for example, we found striking similarities and differences in the experiences of these children and of child returnees, for example, restricting their exposure to different worldviews, and exposing them to violent ideology and activities (Schneider Citation2022). Other fields may also include militias or gangs where there may be similar features related to violence (exposure to, and conduct of), and social dynamics. Children associated with armed groups may have similar roles and participation in violence, and face issues such as social stigma and rejection. Refugee children in some cases may also face displacement and exposure to violence, as well as perceptions as “the other”. These are just some examples. The point is that by viewing children that grow up in families affiliated with terrorism in more dynamics terms we can see that in many ways, key features of their experience may not be so exceptional or unique. Such a comparative approach could help reduce the stigma of children affiliated with terrorist groups, because it would help reframe these children as yet another group that faces risks and adversities while growing up in challenging environments. Such work can also help desecuritise these children and move away from threat-oriented notions.

Future work drawing on EST could also be used to advance and to synthesise findings pertaining to the experiences of children whose families are affiliated with terrorist groups. This would allow us to better understand some of the more commonly shared features of children whose families are affiliated with terrorist groups, and to investigate whether similar experiences correlate with specific risks or resilience factors that may exist in such environments. The guiding questions that we developed based on EST are specifically designed to consider children who grow up in different ideologically-affiliated families and future research could consider right-wing, leftist, and other ideologies, and distinguish between families that remain in their countries versus those who travel to conflict zones.

We hope that by utilising this model in the field of terrorism studies, it will reap some practical benefits. EST could assist scholars who focus on terrorist groups, and particularly on children associated with these, to consider how the life of a child may be impacted in very different and indeed similar ways. In turn, this will enable these scholars to help support more interdisciplinary work with practitioners who may ultimately support these children.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our PREPARE research assistants Breanna Cross, Abirami Rajesh, and Ricardo Jesus Vaz for their assistance on this manuscript, Clarisa Nelu for her help finalising the manuscript, and Prof. Tahir Abbas for his initial review and feedback. We would also like to thank the PREPARE partners ICCT, TNO, Trilateral Research, and Gobierno Vasco – Departmento Seguridad and the PREPARE advisory board for their partnership and collaboration on the PREPARE project for which this manuscript is an output. Finally, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

This project was funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund – Police (ISFP) program under grant agreement No 10,103,586 for the PREPARE project.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joana Cook

Joana Cook is an Assistant Professor of Terrorism and Political Violence at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs (ISGA), Leiden University (Netherlands), and Editor-in-Chief, Senior Project Manager at the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT, Netherlands). She’s also an Adjunct Lecturer at Johns Hopkins University (US). She was the lead investigator of the PREPARE project.

Lynn Schneider

Lynn Schneider is a research fellow at the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. Her work focuses on P/CVE policy and practice, in particular on the educational and legal responses to children affiliated with violent extremist/terrorist organisations. She was a post-doctoral researcher on the PREPARE project.

Notes

1. The term “affiliated” highlights the limited agency that these children often have in the matter and notes the diverse ways in which a child may be associated with a group. This can include children who were taken with, or born to, foreign parents in Syria and Iraq.

2. According to recent TE-SAT reports, this includes arrests related to terrorism offences per year as follows: 2021–388 arrests; 2020–449 arrests; 2019–723 arrests.

3. We refer to an immediate family member involved in violent extremism or terrorism who would most frequently account for parents and siblings, but may also include others (aunts, uncles, grandparents) in cases where they are considered in the micro-environment of the child (see Bronfenbrenner’s model below for further discussion).

4. For reader ease henceforth we refer to terrorism only with the understanding that this also considers children in families affiliated with violent extremism.

5. Future work on this topic may, however, consider the work of Erica Burman, Jens Overtup, and Alan Prout and Allison James, amongst many others.

References

- Achiles, K., A. Nava, and J. Said. 2022. “Remember the Armed Men Who Wanted to Kill Mum: The Hidden Toll of Violence in Al Hol on Syrian and Iraqi Children.” Save the Children International.https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/remember-the-armed-men-who-wanted-to-kill-mum-the-hidden-toll-of-violence-in-al-hol-on-syrian-and-iraqi-children/.

- Al Ibrahim, D. 2020. “Cubs of Caliphate: Analysis of Children’ Images in ISIS Visual Propaganda.” International Journal of Media Science Works 7 (8): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3977932.

- Anaie, T. 2018. “Victimized Perpetrators: Child Soldiers in ISIS and the Need for a New International Legal Approach.” Rutgers Race & L Review 20:93.

- Baker , J., FRONTLINE, PBS. “Episode 13: ‘Your Questions Answered.’” I'm Not A Monster. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/podcast/im-not-a-monster/im-not-a-monster-episode-13-epilogue-your-questions-answered/transcript/.