Abstract

This article explores “the play element in photography”, to adapt a key phrase from Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (1938). The context for this exploration is the melancholic paradigm that dominates much of contemporary writing and thinking about vernacular or popular photography, a paradigm that emphasises memory, death and mourning, at the expense of other practices and dispositions, not least the ludic. It notes that the existing literature on photography and play concentrates almost entirely on humorous images: optical jokes, trick photography, and a wide variety of distorted pictures. But play is an activity, a practice, as much as it is a product or an outcome. In other words, the ludic in photography is not just a quality of the object photographed, but of a photographic doing. Following this principle, the article shows the ways in which key modes of play such as competition, chance, make-believe and vertigo, are at work in photographic practices old and new, including in the aerostatic photography of Félix Nadar, with which it begins and ends.

Seeing ghosts

Whatever photography is, it isn’t much fun.Footnote1 We know this because a host of sombre critics tell us so. Take, for example, Félix Nadar’s Quand j’étais photographe (1900), which, if we are to believe one of its translators, is the gloomiest of books. In his introduction to the English translation, When I Was a Photographer (2015), Eduardo Cadava dwells soberly on the connections that he says Nadar establishes between photography, death and mourning. For Nadar, Cadava tells us, “photographs are taken by the living dead” and “there can be no photograph that is not associated with death”.Footnote2 He makes much of a story Nadar tells of a young man who takes photographs of the town of Deuil from Montmartre, ten miles away. It was the improbable distance that astounded Nadar, but it is the name of the town that Cadava seizes on. Deuil is the French word for mourning, and “In taking a photograph of mourning, the photographer not only takes a photograph of an experience at the heart of photography — mourning may even be another name for photography — but also takes a photograph of photography itself.”Footnote3 Nadar’s photography of the Paris catacombs, meanwhile — remarkable primarily for its pioneering use of artificial lighting — “literalizes the relation between photography and death”.Footnote4 Throughout this analysis it is hard to know exactly who is speaking — is it Nadar who says these things, or is it Cadava who ventriloquizes the dead photographer?

The first thing to note about When I Was a Photographer is its odd, almost picaresque style — what Cadava calls the “wandering, deviating quality of the text” — that makes it, as Rosalind Krauss says, like a “rambling anecdote,” full of “arbitrary elaboration of what seem like irrelevant details, of a constant wandering away from what would seem to be the point.”Footnote5 It is a quality that “has dissuaded readers from it”Footnote6 and no doubt contributed to the century-long gap between original publication and the translation into English. The second thing to note is that it contains no photographs and tells the reader remarkably little about the development of portrait photography and Nadar’s central place in it. Nadar has a little more to say about his adventures in “aerostatic” photography, but he seems more interested in writing about ballooning than about the pictures that he took from balloons. And while it is true that for Nadar photography “materializ[es] the impalpable specter that vanishes as soon as it is perceived,”Footnote7 another picture emerges in his feverish account of what he says Niépce brought into the world:

Everything that unhinges the mind was gathered together there: hydroscopy, bewitchment, conjuration, apparitions. Night, so dear to every thaumaturge, reigned supreme in the gloomy recesses of the darkroom, making it the ideal home for the Prince of Darkness. It would not have taken much to transform our filters into philters.Footnote8

Rather than telling a tale of photography stalked by death, Nadar, in his distinctive and florid way, conjures an image of photography as technological magic, in this case a psychedelic and devilish magic.

As for ballooning, Cadava tells us that airborne Nadar “encountered more than anything else his finitude” and that his aerial photographs “signal an act of mourning that remains in love with a city that could be said to have died several times, even if it is still living, even if, in its living it remains haunted by its past and its deaths.”Footnote9 Nadar did crash a good deal, and sustained some serious injuries, but here is what he says about flight:

Free, calm, levitating into the silent immensity of welcoming and beneficent space, where no human power, no force of evil, can reach him, man seems to feel himself really living for the first time, enjoying, in a plenitude until then unknown to him, the wholeness of his health in his soul and body […] the spasm of ineffable transport liberates the soul from matter, which forgets itself, as if it no longer existed, vaporizes itself into the purest essence […] Another ecstasy, however, calls us back to the admirable spectacle offered to our charmed gazes.Footnote10

We could construe this as evidence of a photographic death drive, a longing for vaporisation, but the “ecstasy” and “plenitude” Nadar reports are above all … lively and vital. Indeed, a recent biography claims that the Great Nadar was “exuberant, agitated, impetuous, horrified by tedium”.Footnote11 Nevertheless, Cadava insists that the photographer’s studio was akin to “a mortuary chamber”.Footnote12

For the daredevil Nadar, photography embodies the joyful thrills of the funfair and magic show, and When I Was a Photographer is a shaggy-dog story, a comic novel. What might lead one to different conclusions, to a favouring of the solemn and serious over the playful and exuberant in Nadar’s prose? One answer is simply, fidelity to a pre-existing and highly efficacious critical framework in photography studies that we might call the melancholic paradigm. For Cadava is far from alone in asserting the primacy of death, mourning and loss in photography. Here are a few more examples from this fertile discursive field:

we arrange photographs in our rooms of our beloved, often because they cannot be with us there – often (and eventually) because they are dead. Photography is the medium in which we unconsciously encounter the dead.Footnote13

There can be no photograph that is not about mourning and about the simultaneous desire to guard against mourning, precisely in the moments of releasing the shutter and of viewing and circulating the image. What the photograph mourns is both death and survival.Footnote14

While the snapshot takes movement as its referent but betrays it through its petrification, the time exposure has stillness or death as its referent but transforms it into a recurrent temporality of mourning.Footnote15

The photographic album, the faithfully visited gravestone, is a monument to memory.Footnote16

And so we have taken our photographs, voraciously and anxiously, as if to fail to do so would be to let our precious memories fade away into the mists of time and amnesia.Footnote17

The selection is partial, even random, but could be almost endlessly supplemented, so widespread is the genre. In sum, according to the melancholic paradigm, photography is a technology of memory, but one in which the remembered object is never fully there, never meets photography’s promise of proof against forgetting. Instead, the paradigm always finds in a photograph absence, lack, anxiety. Its mournful prognostications were once a necessary antidote to the sunny commercial discourse of the snapshot companies, of family ideology, and of simple-minded positivists. For this reason it is particularly prevalent in the study of domestic and vernacular photography, where its repeated articulations mark a stern and necessary vigilance against any anodyne notion that memories are happy or can be straightforwardly and faithfully preserved in the photographic act. The melancholic paradigm has powerful progenitors in Susan Sontag’s On Photography and Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, easily the two most cited books of photography criticism, and indeed much of it could be seen as one long footnote to Sontag’s pithy statement that “All photographs are memento mori”.Footnote18 Once an essential retort to naïve common-sense notions of photographic realism and to the rose-tinted spectacles of the Kodak universe, the melancholic paradigm is now one of the major default settings of photography criticism, reproduced automatically, mechanically, and ubiquitously.

Others have noticed the melancholic paradigm and think that it has outworn its usefulness. Ulrich Baer refers to “Benjaminian-Barthesian theorists of photography who see the referent’s death lurking in every image,” and Joanna Zylinska has tried to move beyond “the typical associations between photography, mourning and death”.Footnote19 Their point, and mine, is not that the melancholic paradigm is fundamentally mistaken, but that its dominance serves to obscure other facets of photographic practice, other traditions, other dispositions. The present article proposes that one such practice and disposition overshadowed by the melancholic paradigm is “the play element in photography,” to reword the sub-title of Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (1938). This ludic dimension in photography might be glimpsed in Nadar’s vertiginous aerial exploits and in the grotesque photo-trickery of Weegee, but also in amateur photo competitions and in the rigorous application of arbitrary variables to image-making. As these examples imply, it would be mistaken to search for ludic photography in ludic photographs alone. As the key theorist of play, Roger Caillois, will allow us to see, play in photography is to be found as much in the photographic act as in the photographic image.

Not serious

For Johan Huizinga, who did more than anyone to challenge the idea that play is frivolous,Footnote20 it is a defining activity of culture, even the defining activity. It is, as he says in Homo Ludens,

an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner. It promotes the formation of social groupings which tend to […] stress their difference from the common world by disguise or other means.Footnote21

With this greatly expanded field of play in mind, ludic photography need not be limited to humorous pictures. Although photographic play does not exclude the comic, it cannot be reduced to it. It might include, among other things: photographic practices with no useful purpose or outcomes; rule-bound photography that resembles a game; all kind of collective photographic activities which are, in Huizinga’s words, “‘not serious’, but at the same time absorbing … intensely and utterly”.Footnote22

Ludic photography does not necessarily mean funny photos, but it is with funny photos that we must start, since no other aspect of the ludic in photography has received as much attention. What makes a photograph playful? One recent answer to this question can be found in the special Playtime issue of Aperture magazine (2013). As instances of the playful in photography Playtime offers the absurdist fashion photography of Erwin Wurm, avant-garde experiments from Baldessari and Nauman to Simmons and Antin, images of school grounds and playgrounds, and of the antics of Cambridge undergraduates, montages by Evan Stenram, xerographs by Bruno Munari, and the staged scenes of Kazuyoshi Usui. The front cover features Olaf Bruening’s Pattern People, a series of intertwined bodies dressed head to toe in multi-colour fabrics redolent of cartoons and clown costumes, while on the back cover a blonde child advertises offset.com. What unifies this motley assemblage? The Playtime issue offers no overarching thesis, no master framework to account for what holds these images together as a field. There is an implicit, and in one or two cases explicit, acknowledgement of the debt that playful photography owes to surrealism, with many of the humorous effects in the issue achieved through surprising juxtapositions. This is especially the case in the section “Swiss Mess” devoted to Bruening and a number of his compatriot photographers, where montage and incongruous elements prevail. This absorption of the photographically ludic into an art-historical narrative is to be expected given the magazine’s orientation, but there is no real consideration of the playful beyond that artworld milieu.

In addition to the surrealist current, but without saying so, Aperture broadly defines photographic play in three ways. There are photographs of play (or sites of play); photographs in which play is contrived or constructed for the camera; and photographs which have been played with in one way or another. The three types are not exclusive, and more than one can be at work in any given image in Aperture’s playful miscellany. To shed more light on the third type, we can turn to László Moholy-Nagy’s “eight varieties of photographic vision.” Along with photograms, reportage, snapshots, prolonged exposures, micro and filter photography, radiography and auto photomontage, Moholy-Nagy’s final variety of photographic vision is “Distorted seeing.” This comprises

optical jokes that can be automatically produced by: a) exposure through a lens fitted with prisms, and the device of reflecting mirrors, or b) mechanical and chemical manipulation of the negative after exposureFootnote23

It is a very helpful clarification to locate the source of humour, of the optical joke, in distortion, because it implicitly suggests that visual norms are at stake, and that the comical image contests or upends those norms. At the same time, Moholy-Nagy’s eighth variety of photographic vision allows us to put aside a number of extraneous and borderline cases by making clear that the distortion is a product of specifically photographic processes, rather than being, for example, an attribute of the object photographed.Footnote24 Moholy-Nagy’s schema also brings some respectability to ludic photography by placing it on an equal footing with other kinds of photographic vision, even if it is the last listed of eight. Even more importantly, his category of “distorted seeing” leads us to think historically about funny photos, obliging us to recognize that what Aperture identifies as a contemporary trend is in fact a well-established mode with a long history.

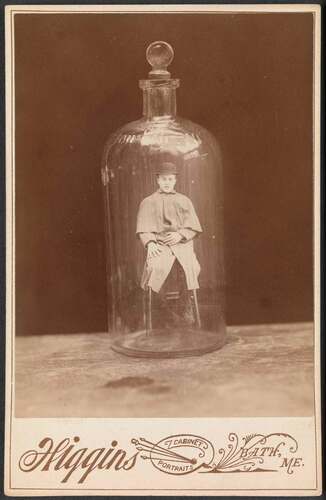

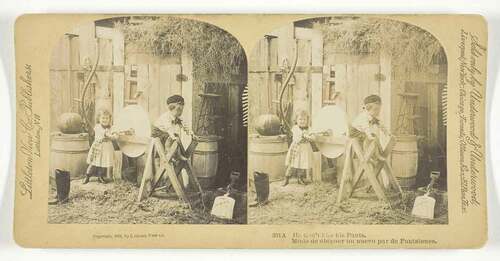

Moholy-Nagy writes of optical jokes, but the techniques that he describes more often fall under the general rubric of trick photography. This history is chronicled by Mia Fineman in Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop, the catalogue of a MOMA exhibition whose sub-title indicates the contemporary lens through which it revisited photographic trickery. Fineman cites among the techniques of manipulation “multiple exposure, combination printing, photomontage, overpainting, retouching”.Footnote25 She notes that as early as the 1860s commercial studios were producing amusing cartes-de-visite featuring men trapped in bottles, woman turned into statues, and people consorting with their double ().Footnote26 Disembodied heads and headless bodies were a perennial favourite of trick photography, as were images of these bodies with the head held in one arm. The nineteenth-century stereograph craze, built on a technology of juxtaposition, was also a natural opening for amusing distortions and photographic tricks ().Footnote27

By the 1890s the tools for making such images were well within the reach of amateurs, and the craze for trick photography was sustained by best-selling how-to books: in France, Bergeret and Drouin’s Les récréations photographiques; (1891); in Germany, Herman Schnauss’ Photographischer Zeitvertreib (1893); in the United States, Walter E. Woodbury’s Photographic Amusements: Including a Description of a Number of Novel Effects Obtainable with a Camera (1896); and in England, Albert A Hopkins’ Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Including Trick Photography (1897). The popularity of “headless” photographs hints at the loss of reason that accompanies the comic, whilst displaying a detached and droll attitude to death that is far removed from the melancholic paradigm. Woodbury’s guide went through eleven editions and was still in print in 1937.Footnote28 Later into the twentieth century Herbert George Ponting patented a lens attachment he called a “variable controllable distortograph” with which he made caricatures of the Chicago Mayor, Big Bill Thompson.Footnote29 Following in Ponting’s footsteps was of course the ‘idiosyncratic jokiness’Footnote30 of Weegee, whose tricks and techniques for producing grotesques are documented in his Creative Camera. In parallel to popular and populist trick photography, as Clément Chéroux has shown, avant-gardists, among them Moholy-Nagy, took up the possibilities of récréations photographiques for artistic purposes.Footnote31

New moves

Play is an activity, not an outcome. It is a doing, not a product or a meaning. And yet, most critics and thinkers who have examined the play element in photography have concentrated on photography’s product — the image — rather than photographic acts and activities. One notable exception is Vilém Flusser. In Towards a Philosophy of Photography, Flusser writes that “The camera is not a tool but a plaything (Spielzeug), and a photographer is not a worker but a player: not Homo faber but homo ludens.”Footnote32 Flusser gives no quotations from other works and provides no bibliography, but the reference to Huizinga is clear. For Flusser a camera is a black-boxed Spielzeug and photography is interchangeably a “program” or a game. In fact, there are in a camera “two interweaving programs”: “One of them motivates the camera into taking pictures; the other permits the photographer to play.”Footnote33 Through the camera’s “program,” photographers engage in “a game of making combinations with the various categories of their camera.”Footnote34

Since Flusser disdains discussing individual photographs or photographers, it is not very easy to understand what he means or how this works in practice. However, the abstraction of play and Spielzeug in Towards a Philosophy of Photography is partially concretized by two analogies of gaming that Flusser introduces in the course of his short book: chess and dice. Drawing on, but not citing, Saussure’s analogy between chess and language (it is not the material the pieces are made of, but their relations to each other that matter),Footnote35 Flusser argues that an “apparatus” like a camera is not a machine, but a plaything, because it is not the materials from which it is composed that matter, “but the rules of the game, the chess program.”Footnote36 The limits of the chess analogy also help him to specify the nature of the photographic game: “The camera is a structurally complex, but functionally simple, plaything. In this respect it is the opposite of chess which is a structurally simple, and functionally complex game.”Footnote37 Dice, meanwhile, Flusser introduces when he comes to discuss “the photographic universe,” by which he means “the flood of redundancy” of the same familiar images being produced over and over again according to an “automatic” program.Footnote38 This situation resembles the throw of dice, because each instance is random, unpredictable, and yet at the same time can only produce a limited number of combinations, dependent on the numbers 1 to 6 inscribed on the dice. In Flusser’s summary: “The photographic universe is a means of programming society […] for the benefit of a combination game, and of the automatic reprogramming of society into dice, into pieces in the game, into functionaries.”Footnote39

Chess is a game of skill and dicing is a game of chance. It is an opposition that Flusser never explicitly states, while nevertheless clearly favouring chess over dice in the route he envisions out of photography’s impasse: the impasse of always playing the same moves. In this context he reserves special contempt for amateur snapshooters and hobbyists, who “[u]nlike photographers and chess-players […] do not look for new moves […] for the improbable, but wish to make their functioning simpler and simpler by means of more and more perfect automation”.Footnote40 Betraying a notable intimacy with the hobbyist’s obsession with kit and gear, he dismissively calls photography clubs “post-industrial opium dens,” “places where one gets high on the structural complexities of cameras.”Footnote41 As a result hobbyists are no more than “functionaries” of the program of chance. “The photographer” in contrast is “interested (like the chess-player) in seeing in continually new ways, i.e. producing new, informative states of things.”Footnote42

Both amateurism and chance have greatly animated theorists of play. Where Flusser excludes the amateur as insufficiently skilled to produce new moves, it is the professional who is looked on with suspicion in much theory of play. Huizinga, who is aristocratic in his outlook and preferences,Footnote43 rules the professional out of the world of play entirely: “The spirit of the professional” he says, “is no longer the true play-spirit; it is lacking in spontaneity and carelessness.”Footnote44 Caillois agrees, arguing that since games are “an occasion of pure waste […] waste of time, energy, ingenuity, skill, and often of money,” professionals are not players at all but workers.Footnote45 For his part, Flusser’s antipathy for the intoxicated amateur does not have as its alternative the skilled professional. Instead, he simply calls the one capable of new moves “the photographer”.

With chance, Huizinga and Caillois part ways. For Huizinga, games of chance do not count as play because they “fall into the category of gambling” and therefore involve a material interest that should not be present in play.Footnote46 Caillois thinks that Huizinga and other theorists of play exclude games of chance because of the ill repute of gambling rather than the fact that there is a material interest at stake.Footnote47 Gambling and games of chance are disreputable, Caillois says, because they hinge on belief in fate or destiny, and therefore are at odds with rational and bourgeois ideology.Footnote48 To put it another way, Huizinga sees gambling from the perspective of the winner, that is, as an occasion to accumulate, while Caillois, a realist, but also a Bataillean, sees it from the perspective of the loser, and so finds in it no contradiction with his assertion that play is “an occasion of pure waste”. He concludes that “Games of chance would seem to be peculiarly human”.Footnote49

In sum, Huizinga opens up the path for us to take play seriously, and Flusser shows that play in photography may be a question of apparatus and program — of doing — rather than just image. It is Caillois though, with his sympathy for the amateur and his expansion of what counts as play, who offers the richest and broadest scope for understanding the ludic in photography, allowing us, among other things, a non-melancholic interpretation of Félix Nadar and his balloon.

Modalities of play

The value of Caillois to this discussion is that he prompts us to look for ludic photography in less obvious places. In Man, Play and Games (1961), he proposes a division of play into four modes or modalities,

depending on whether […] the role of competition, chance, simulation, or vertigo is dominant. I call these agon, alea, mimicry and ilinx respectively. All four indeed belong to the domain of play. One plays football, billiards, or chess (agon); roulette or a lottery (alea); pirate, Nero, or Hamlet (mimicry); or one produces in oneself, by a rapid whirling or falling movement, a state of dizziness and disorder (ilinx)Footnote50

Agon, alea, mimicry and ilinx are not arbitrary designations, but have clear structural relations to each other. Whereas pure agon is an ideal contest in which the winner prevails through greater skill and cunning, in pure alea the player has no control over the outcome of the game and winning is an “insolent and sovereign insult to merit.”Footnote51 Mimicry involves assuming an external disguise through make-believe, while ilinx acts directly on the body. At the same time, agon and alea tend to be based on artificially-contrived rules and obstacles, whereas mimicry and ilinx are on the side of “improvisation and joy”.Footnote52 These relations, and some examples, are provided by Caillois in .

Caillois’ examples are wide-ranging and his categories capacious, especially once he adds to the primary instances of “cultural forms” the fallen dimensions of “corruption” and “institutional forms”.

Photography is not exactly a game or cultural form of the sort that Caillois identifies. At the same time, it has without doubt been turned into a contest, or subjected to chance, or been a pretext for play-acting, or even become a source of vertiginous thrills. Caillois is good to think with, and by trying out his categories, putting them to the test of photography, we discover that the play element in photography is more widespread than might normally be assumed. Taking them in turn, I will pass over alea and mimicry more quickly in order to concentrate especially on the competitive and vertiginous in photography, not because chance and make-believe are not at stake in photography, but because they are elements of photographic play that have already been amply explored, if not always as forms of play.

As Michelle Henning notes, the aleatory dimension of photography has often been remarked on. Not only does “the chance constellation of a moment produce an image that could not be completely anticipated prior to its making”, (8), but photographs almost without fail include “contingent, unexpected details” that were not planned or seen and are only detected after the fact.Footnote53 This is not the chance of play, the alea that concerns Caillois, because it is not rule-bound, but rather approaching the realm of pure accident, sheer contingency. In Photography and the Art of Chance, Robin Kelsey takes up this tension between the accidental and the intentional, concentrating on photography that aspires to be art. He detects two strong currents in twentieth-century photographers’” response to the fact that photographs give “the stray and trivial the same treatment as the main and essential”.Footnote54 In the first position — held by Edward Weston, the Newhalls, Walker Evans — there is a prejudice against chance and a will to mastery over the image that would eliminate the arbitrary and contingent. Kelsey is more interested, however, in those who would harness chance, and explicitly put it into play in the making of images. The exemplar here is John Baldessari and works such as Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts) and Choosing (A Game for Two Players), in which the photographer draws on military game simulations popular in California in the early 1970s.Footnote55 In each case Baldessari subjects himself to arbitrary and apparently absurd constraints. In other words, he sets some rules, turning photography into a game of chance, a roll of the dice whose outcomes he cannot control, even if he has determined the parameters in which photographic fate plays out.

“[I]t is not,” Roland Barthes proposes, “by Painting that Photography touches art, but by Theater.”Footnote56 For Barthes the theatricality of photography leads to melancholy, not play, or at least shows us that the ludic and the melancholic paradigms are not mutually exclusive: “Photography is a kind of primitive theater,” he writes, “a kind of Tableau Vivant, a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead.”Footnote57 Mimicry, in other words, potentially encompasses the entirety of photography. In short, if mimicry in Caillois’ scheme means make believe and play-acting, then it is applicable, at the very least, to the entire universe of the pose and the studio. It would include all those images in the Playtime issue of Aperture that I described as “contrived or constructed for the camera,” and would take in everything from William Wegman’s Weimeraners to Cindy Sherman’s stylised self-inventions, to Jeff Wall’s elaborately staged tableaux vivants, to mention only the most frequently commented upon.Footnote58 It also takes us into an old debate pitting artifice against documentation, fiction against fidelity, in what was once dubbed the “directorial mode.”Footnote59 Beyond the art world, ludic mimicry might include “mugging” or “gurning” for the camera, and the whole rich field of performativity in amateur and popular photography.Footnote60 In most cases mimicry takes us back to the ludic residing in one way or another in the object photographed rather than in photographic practices; in the image rather than in the doing.

Photography, agon and ilinx

Organisers of photography contests would have us believe their events are all about the images, but connoisseurs of play will see immediately that they are also about kindling the photographic agon. Competition has always been an important part of photographic cultures, especially amateur ones, and photography contests are a rich and complex ecology in their own right. It is also currently an expanding ecology that builds on inherited modes and overlaps and seeps into other practices. For instance, there are photography “competitions” that outwardly resemble aspects of playful activity, but which are not strictly speaking ludic. These are prestige prizes and awards such as the Prix Pictet, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, World Press Photo Contest, or the Inge Morath Award. For the purposes of drama and promotion, these prizes are often presented with agonistic trappings, with finalists, runners-up and so on. However, the competitors are not players, but workers, who do not enter the field, but are nominated, and who, if they win, are recognized for their work, not for their play. With substantial prize money and reputational gain for the winners, they do not pass the basic test of play, which is that there should be no “material interest” at stake.

At the other end of the scale, there is a vast flowering of photo contests that do meet Caillois’ definition of play as a wasteful activity: “waste of time, energy, ingenuity, skill, and often of money”. (“Waste” does not have negative connotations for Caillois, but to remove any doubt, one could substitute the words “non-productive expenditure”.) Some of these contests are curated by media platforms that set a weekly or monthly challenge or theme, such as the BBC’s “We set the theme, you take the pictures”, or The Observer’s “Your pictures: Share your photos on the theme of …”. Others are one-off events run, for example, by charities or colleges or Universities, in order to promote an event or to constitute a virtual community. “Selfie” contests alone make up a fertile and sprawling sub-set, often with modest prize money. Image-hosting sites such as Flickr, Photobucket, and Facebook run a variety of themed contests, but also enable user-run contests which are small-scale and exist without official endorsement and with no prospect of financial gain in a devolved agon where photographers temporarily club together and decide winners through one member one vote systems. As Annebella Pollen has shown in Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life, such projects also predate the internet and digital photography, and many of them have their germ in the One Day for Life competition in 1987.Footnote61

In the growing middle between high prestige non-play and low prestige genuine play there is a bewildering array of contests and competitions that follow the formulae of play, but mostly seek the prestige of the elite prizes. These include the International Photography Awards and the Sony World Photography Awards, each with elite juries and multiple categories open to professionals and non-professionals and culminating in awards ceremonies and exhibitions. Most of the genres represented in these large-scale enterprises also have their own niche contests with corporate or institutional sponsors: Wildlife Photographer of the Year (Natural History Museum), Food Photographer of the Year (Pink Lady Apples), Travel Photographer of the Year (numerous), Cricket Photo of the Year (Wisden — MCC), and so on. Manufacturers of camera equipment and photography magazines run online contests, just as they did before digital and before the internet. While these contests, proliferating in the era of user-generated content, all adopt in one way or another the outward forms of the agon, they tend to be highly regimented modes of play, with entry fees, cash and other prizes, and complex corporate and sponsor structures. Almost without exception they aspire to translate play into work; to convert what might be wasteful expenditure into useful and productive activity. They solicit professional, non-professional and student entrants to their lists, that is, those who work at, those who play at, and those who study photography, but it is either explicitly stated or strongly implied that those who are successful at photographic play who are not already photographic workers will soon graduate from play to the realm of work. These are contests in which the ultimate aim is to leave behind the non-seriousness of the agon.

None of today’s large-scale online photo competitions can claim to have invented the format or even substantially renovated it. Most of its features were established in conjunction with the rise of hobbyist photography in the early twentieth century. Along with photography magazines and camera manufacturers, the third key actor in the foundation of photo contests was the camera club. While for the magazines and the manufacturers, the photo contest was a way to drive sales and circulation, the camera clubs provided the players for the game. Each club would usually run its own competition, with the annual exhibition the culmination of the local photographic calendar. In the UK, amidst the wider ubiquity of photography and photographers, camera clubs still exist, and with them the vestigial, and original, popular photo competitions. This was a transnational phenomenon, as shown by Kerry Ross in Photography for Everyone: The Cultural Lives of Cameras and Consumers in Early Twentieth-Century Japan, one of the most detailed investigations of the symbiosis of camera enthusiasts, camera clubs, photo manufacturers, and photography print media. Ross demonstrates the centrality of photography contests to this nexus in Japan up to the 1940s. All of the popular photography magazines — Asahi Kamera, Fuototaimusu, Shashin Geppo — ran monthly photo competitions for their readers, sometimes in collaboration with manufacturers such as Konishi Roku (Konica), who required use of one of their cameras to qualify for a contest.Footnote62 At the same time, monthly competitions were the “central participatory ritual of the camera club,” and were based on themes such as “dusk,” “vehicles,” “people selling things,” “rivers,” and “rural dwellings.”Footnote63

According to Huizinga, “All play has its rules. They determine what ‘holds’ in the temporary world circumscribed by play.”Footnote64 In the photo contest where do the rules reside? Are they in the obligation to use a Konishi Roku camera? Are they in the binding constraints of the indispensable and ubiquitous “themes”? Will the player who best understands and works within these rules win the game? For the BBC’s “We set the theme,” the rules are brief and largely technical:

Please include the title of theme in the subject line of your message and remember to add your name and a caption: who, what, where and when should be enough, though the more details you give, the better your chance of being selected.

You can enter up to three images per theme.

Pictures should be sent as Jpeg files. They shouldn’t be larger than 5Mb and ideally much smaller: around 1Mb is fine, or you can resize your pictures to 1,000 pixels across and then save as a Jpeg.Footnote65

The iPhone Photography Awards, which have a number of thematic sub-categories (Children, Panorama, Sunset, Travel, and so on) are also bound by technical restrictions:

Entries are open worldwide to photographers using an iPhone or iPad. Photos should not be published previously anywhere. The posts on personal accounts (Facebook, Instagram etc.) are eligible. The photos should not be altered in any desktop image processing program such as Photoshop. It is OK to use any IOS apps.Footnote66

As rules go, they do not tell the player much about how to win the game. They are more like the obligation to wear white at Wimbledon, and to use a racquet whose length does not exceed 29 inches. This is because in addition to these bland terms and conditions, there is another set of rules, the ones that determine what makes a “good” photograph.

In Good Pictures: A History of Popular Photography, Kim Beil has shown how the rules of what makes a “good picture” are not exactly like the rules of poker, lacrosse or mah-jong. It is not that they are not written down. The hundreds of photographic “[h]andbooks, instructional articles and how-to-guides” that she mines in her book attest to the fact that the “rules” have been regularly spelt out.Footnote67 And each time they are spelt out, it is as eternal doxa, even though in fact good pictures are “good pictures according to the rules of a specific time and place.”Footnote68 In other words, rules for popular photography exist, are very clear to those who know them, and change all the time, as Beil shows in relation to back-lighting, blur, and low angles, among many other amateur photographic canons and trends she traces in Good Pictures. The rules also need to be interpreted. In her comprehensive analysis of the One Day for Life competition, Pollen shows what this means in practice: the enlisting of camera clubs, and an army of curators, editors and practitioners to narrow 55,000 submissions down to the 350 images published in the resultant book, through the application of aesthetic criteria that were protean, complex and contradictory.Footnote69 Unlike a sport then, where the rules are only rarely modified, in the photographic agon the rules are under constant negotiation and evolution. As Beil says, “the rules are not only communicated through instructional articles; they are intuited when people compare their own pictures with those made by others.”Footnote70 In other words, the photographic player enters a photo contest to find out the rules, to show mastery of the rules, and to refine and develop the rules, simultaneously. In sport, rules enable iterations of play. In photo contests, play iteratively produces the rules.

At the opposite pole from the rule-bound play of the agon is the unruliness of ilinx, Caillois’ final mode of play, in which “one produces in oneself, by a rapid whirling or falling movement, a state of dizziness and disorder.”Footnote71 In my book The Camera Does the Rest, I did not use Caillois’ vocabulary, but in retrospect I can see that I demonstrated that the photographic ilinx is at work in Polaroid photography. I noted the regular claims, both positive and negative, that Polaroid cameras were no more than toys, and that the defining feature of the technology was that it was “fun”.Footnote72 For Roland Barthes, this alone was reason enough to dismiss Polaroid.Footnote73 If one was not to dismiss it, the playful aspect had to be taken into account, and when it was, it became clear that existing critical models for talking about popular and amateur photography, such as the melancholic paradigm — so insistently oriented towards questions of memory — were not satisfactory. Taking a cue from early Polaroid ads that claimed, “There’s no thrill like seeing your pictures 60 seconds after you shoot them,” I placed Polaroid under the rubric of a “photography of attractions”.Footnote74 The term adapts the “cinema of attractions,” a concept developed by Tom Gunning to explain the centrality of sensation for the early cinema, sensation that was directly linked to the novelty of cinematic technology.Footnote75 Polaroid also traded on novelty, the “thrill” of using instant photography attributable to the astonishing magic that allowed an image to appear immediately.

I used “photography of attractions” as a way to mark out the distinctiveness of Polaroid photography, making of it a playful exception, or a disjunction, in an historical narrative about popular photography in which representation, identity, and memory are the dominant themes. However, it is clear that what Caillois calls ilinx — play that includes the thrill of the rollercoaster, the bodily sensation of sky-diving — is very much at work in other contemporary photographic practices. Take, for example, the popularity of Go Pro and other action cameras. Common sense tells us that they have been built rugged and waterproof in order to enable the faithful recording of extreme sports. But might it not be the other way around? To use Flusser’s term, might not the camera’s “program” lead its operator to the vertiginous feats? Equally, it is under the sign of ilinx that we can understand the phenomenon of “death by selfie,” in which unlucky amateurs seek out risk entirely motivated by the photographic act. Far more of these thrill-seeking photographs end without incident than end badly, but it is of course the latter that get documented. Of the hundreds of examples of “death by selfie” recorded on the dedicated Wikipedia page, by far the most record “falling” as the cause of death, followed by incidents with trains. Weapons feature fairly regularly, as do animals, both in captivity and in the wild: bears, jaguars, rattle snakes, elephants.Footnote76 Photographic ilinx, then, would seem to bring us full circle to the melancholic paradigm, and its absorption in death. Except that the melancholic paradigm has no answer to daredevil photography, or its sometimes tragic-comic outcome. The woman grinning at the end of a bungee cord, the man posing yards from a grizzly, the couple dangling from a bridge: they have all fundamentally misunderstood the solemn, belated and sorrowful core of photography, and found in it some other, exhilarating, enjoyment.

This returns us to the intrepid nineteenth-century French balloonist, who reminds us that contemporary thrill-seeking photography has significant antecedents. There is a much-reproduced Daumier lithograph of Nadar — himself a very successful humourist and caricaturist before he turned to photography (). In it, Nadar flies precariously over Paris, coattails akimbo, top hat flying loose, hair windswept, his only anchor to the balloon his hands fixed to the camera into which he stares intently. It is an image of photography breathless, thrilling, dangerous. The caption below is either a humorous contrast with the image, or an attempt to bring some serenity to the recklessness of what is shown: “Nadar, elevating photography to the level of art.” Why not, instead, “Nadar: photographie ludique”?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter Buse

Peter Buse is Dean of the School of the Arts at the University of Liverpool and author of The Camera Does the Rest: How Polaroid Changed Photography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Notes

1. This article started life as a talk at the Light | Sensitive | Materials conference at the University of West London in November 2019. The conference title was rich in possible meanings. I chose to interpret “light” not in its optical sense, but in terms of weight, treating it as an invitation to think about photographic lightness.

2. Cadava, “Nadar’s Photographopolis,” xiv & xlvi

3. Ibid., xxv.

4. Ibid., xxxvii.

5. Cadava, “Nadar’s Photographopolis,” xi; and Krauss, “Tracing Nadar,” 29.

6. Cadava, “Nadar’s Photographopolis,” xi.

7. Nadar, When I Was a Photographer, 3.

8. Ibid.

9. Cadava, “Nadar’s Photographopolis,” xxxix & xlii.

10. Nadar, When I Was a Photographer, 57–8.

11. Begley, The Great Nadar, 3.

12. Cadava, “Nadar’s Photographopolis,” xli.

13. Prosser, Light in the Dark Room, 1.

14. Richter, “Between Translation and Invention,” xxxii.

15. Doane, “Real Time,” 28.

16. Langford, Suspended Conversations, 198.

17. Batchen, “Ere the substance fade,” 42.

18. Sontag, On Photography, 15. In mid 2021 Camera Lucida (10,525 citations) had a slight edge over On Photography (9,756) in the English language on Google Scholar. This is hardly a rigorous measure, but the distance between these two and the rest gives a rough sense of their all-pervasive influence.

19. Baer, Spectral Evidence, 16; Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography, 4–5. See also Buse, The Camera Does the Rest, 27–30.

20. Sutton-Smith, Ambiguity of Play, 202.

21. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 13.

22. Ibid.

23. Moholy-Nagy, “A New Instrument of Vision,” 94.

24. For example, for the purposes of this article, Garcia, Photography and Play, is very promisingly titled, but is in fact just a collection of images of people “at play” in the broadest sense — on holiday, at the beach, engaged in “leisure” activities.

25. Fineman, Faking It, 7.

26. Ibid., 117.

27. See Henisch and Henisch, Positive Pleasures, 148–50; and Kaplan, Photography and Humour, 106.

28. Kaplan, Photography and Humour, 53.

29. Fineman, Faking It, 105.

30. Flint, Flash!, 193.

31. Chéroux, Avant l’avant-garde.

32. Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography, 27.

33. Ibid., 29.

34. Ibid., 35.

35. Saussure, Cours de linguistique générale, 125–29.

36. Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography, 30.

37. Ibid., 57.

38. Ibid., 65 & 69.

39. Ibid., 70.

40. Ibid., 58.

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid., 59.

43. Sutton-Smith, Ambiguity of Play, 203.

44. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 197.

45. Caillois, Man, Play and Games, 5–6. Another view is offered by Bernard Suits, who argues that the amateur and the professional may hold different attitudes towards games, but not towards rules. Suits, The Grasshopper, 146.

46. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 198.

47. Caillois, Man, Play and Games, 169–70.

48. Ibid., 69.

49. Ibid., 18.

50. Ibid., 12.

51. Ibid., 17.

52. Ibid., 27.

53. Henning, The Unfettered Image, 18 & 120.

54. Kelsey, Photography and the Art of Chance, 6.

55. Ibid., 306–10.

56. Barthes, Camera Lucida, 31.

57. Ibid., 32.

58. See for example, Campany, “Preface,” 23–32.

59. See Coleman, “The Directorial Mode.”

60. See for example, Stylianou-Lambert, “Tourists with Cameras,” 90–93.

61. Pollen, Mass Photography, 1–3, 24–28.

62. Ross, Photography for Everyone, 137–46.

63. Ibid., 124–5.

64. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 11.

65. “We set the theme.”

66. “IPPA Awards.”

67. Beil, Good Pictures, 6.

68. Ibid., 4.

69. Pollen, Mass Photography, 147–85. Pollen does not frame her study in relation to play, but her account is one of the most thoroughgoing of the way in which amateur photographic canons and categories are formed and judged through competition. She is also very clear that One Day for Life was not just a competition, but a “mass-participation project” inspired by charitable fund-raising and with wider ambitions that included “visual history, democracy, communication”, as well as community and even nation-building. Pollen, Mass Photography, 2.

70. Ibid., 6.

71. Caillois, Man, Play, and Games, 12.

72. See Buse, Camera Does the Rest, 25–50.

73. Barthes, Camera Lucida, 9. Barthes calls Polaroid “Fun, but disappointing,” but as has been noted by many, the original edition of his book has for its frontispiece a Polaroid by Daniel Boudinet, so it is not entirely clear whether Barthes should be taken at his word. For an account of the debates around this image, see Buse, Camera Does the Rest, 30 & 236.

74. “More FUN with a Camera.”

75. Gunning, “Aesthetic of Astonishment.”

76. “List of selfie-related injuries and deaths.” See also Jain and Mavani, “A Comprehensive Study.”

References

- Aperture, vol. 212 Playtime. Fall, 2013.

- Baer, U. Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

- Barthes, R. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. London: Jonathan Cape, 1982.

- Batchen, G. “Ere the Substance Fade: Photography and Hair Jewellery.” In Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, edited by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, 32–46. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Begley, A. The Great Nadar: The Man behind the Camera. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

- Beil, K. Good Pictures: A History of Popular Photography. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2020.

- Bergeret, A., and F. Drouin. Les récréations photographiques. Paris: Ch. Mendel, 1891.

- Buse, P. The Camera Does the Rest: How Polaroid Changed Photography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Cadava, E. “Introduction: Nadar’s Photographopolis.” In When I Was a Photographer ( translated by Eduardo Cadava and Liana Theodoratou), edited by Félix Nadar, ix–xlvii. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

- Caillois, R. Man, Play, and Games. Translated by Meyer Barash. New York: The Free Press, 1961.

- Campany, D. “Preface.” In Art and Photography, edited by David Campany, 10–45. London: Phaidon, 2003.

- Chéroux, C. Avant l’avant-garde. Du jeu en photographie, 1890–1940. Paris: Textuel, 2015.

- Coleman, A.D. “The Directorial Mode: Notes Towards a Definition.” In Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present, edited by Vicki Goldberg, 480–491. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981.

- De Saussure, F. Cours De Linguistique Générale. Paris: Payot, 1971.

- Doane, M. “Real Time: Instantaneity and the Photographic Imaginary, in Stillness and Time.” In Stillness and Time: Photography and the Moving Image, edited by David Green and Joanna Lowry, 22–38. Brighton: Photoworks, 2006.

- Fineman, M. Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop. New York: MOMA, 2012.

- Flint, K. Flash!: Photography, Writing, and Surprising Illumination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Flusser, V. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Translated by Anthony Mathews. London: Reaktion, 2000.

- Garcia, E.C. Photography and Play. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012.

- Gunning, T. “An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)credulous Spectator.” Art and Text 34 (1989): 31–45.

- Henisch, H.K., and B.A. Henisch. Positive Pleasures: Early Photography and Humour. Penn: University Park, Penn State Press, 1998.

- Henning, M. Photography: The Unfettered Image. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2018.

- Hopkins, A.A. Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Including Trick Photography. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co., 1897.

- Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (1938). Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2016.

- “IPPA Awards: Call for Entries.” Accessed February 27, 2021. https://www.ippawards.com/2021-entries-form/

- Jain, M.J., and K.J. Mavani. “A Comprehensive Study of Worldwide Selfie-related Accidental Mortality: A Growing Problem of the Modern Society.” International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion 24, no. 4 (2017): 544–549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2016.1278240.

- Kaplan, L. Photography and Humour. London: Reaktion, 2017.

- Kelsey, R. Photography and the Art of Chance. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2015.

- Krauss, R. “Tracing Nadar.” October 5 (1978): 29–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/778643.

- Langford, M. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001.

- “List of Selfie-related Injuries and Deaths.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_selfie-related_injuries_and_deaths. Consulted 27 February 2021.

- Moholy-Nagy, L. “A New Instrument of Vision.” In The Photography Reader, edited by Liz Wells, 92–96. London: Routledge, 1936 [2003].

- “More FUN with a Camera.” Camera, February, 1950.

- Nadar, F. When I Was a Photographer. Translated by Eduardo Cadava and Liana Theodoratou. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2015.

- Pollen, A. Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life. London: I.B. Tauris, 2016.

- Prosser, J. Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

- Richter, G. “Between Translation and Invention: The Photograph in Deconstruction.” In Copy, Archive, Signature: A Conversation on Photography, edited by Jacques Derrida, ix–xxxviii. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2010.

- Ross, K. Photography for Everyone: The Cultural Lives of Cameras and Consumers in Early Twentieth-century Japan. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2015.

- Schnauss, H. Photographischer Zeitvertreib: Eine Zusammenstellung einfacher und leicht ausführbarer Beschäftigungen und Versuch mit Hilfe der Camera. Düsseldorf: Liesegang, 1893.

- Sontag, S. On Photography. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. “Tourists with Cameras: Reproducing or Producing?” In The Photography Cultures Reader: Representation, Agency and Identity, edited by Liz Wells, 90–109. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Suits, B. The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1978.

- Sutton-Smith, B. The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge: Harvard, 1997.

- “We Set the Theme, You Take the Pictures.” 1 March 2020. Accessed February 27, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-10768282

- Weegee, Creative Camera. Garden City, New York: Hanover House, 1959.

- Woodbury, W.E. Photographic Amusements: Including a Description of a Number of Novel Effects Obtainable with a Camera. 3rd ed. Scovill and Adams: New York, 1898.

- Zylinska, J. Nonhuman Photography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017.