ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to analyse the early phase of apparel design process and how professional designers develop their kernel idea by sketching and how visual sources stimulate their ideation. Three designers were asked to design a piece of outerwear while thinking aloud in an experimental design session. The data (i.e. verbal and video protocols as well as material written and drawn by the participants) was analysed with qualitative content analysis and by constructing idea development diagrams. The results indicated variations in the (1) use of photographs as sources of inspiration, (2) emphasis on simplification and association in interpretation and adaptation of these sources, and (3) designers’ primary generators. Our findings on how expert designers utilise visual material for example to adapt visual details into their ideas or to envision a suitable fabric could be used to give illustrative examples for students of apparel design.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this study was to analyse design expertise, with a special emphasis on the ideation sources and processes of apparel designers. We focused on analysing the idea development of apparel designers: how they developed their kernel idea with the inspiration sources provided and how the design ideas were represented in their sketches. Design ideation and processes have been fields of intense investigation for more than forty years (Cross, Citation2004). However, very little research has been conducted thus far in the field of textile and apparel design.

Only recently has the research on ideation been extended to the field of textile and fashion design (e.g. Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000; Laamanen & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, Citation2014; Lee & Jirousek, Citation2015; Mete, Citation2006; Petre, Sharp, & Johnson, Citation2006). Moreover, design ideation is seen as one of the most important phases for generating and transforming visual representations (Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000, Citation2003; Petre et al., Citation2006). In order to educate future textile and fashion designers, we need a better understanding of the design process of apparel designers and their ways of knowing and thinking (Cross, Citation2006), particularly for the early phase of designing. With this as a starting point, the present study examines the earliest phases of the apparel designers’ design and sketching processes, and their use of sources of inspiration. The research question was: How do professional apparel designers develop their kernel idea by sketching and how do visual sources stimulate their ideation?

2. Related literature

2.1. Ideation and sources of inspiration

Many critical decisions are made in the early phase of design, usually called ideation or the conceptual design phase (Howard, Culley, & Dekoninck, Citation2008) In this iterative process, various inspiration sources enable designers to move from their first vague images towards envisioning final ideas (Laamanen & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, Citation2014; Petre et al., Citation2006). This preliminary design phase involves the initial generation and exploration of ideas to create new solutions. These undetermined alternatives emerge through the incremental transformations of a few kernel ideas (Goel, Citation1995). According to Jonson (Citation2005), an idea in design represents a basic element of thought that can be either visual, concrete, or abstract. Thus, the emergent design idea is not known beforehand, although expert designers do develop ideas from their own previous designs or utilise guiding themes or principles; in design research, these are often referred as precedents (Schön & Wiggins, Citation1992). The designer's previous experiences and an acquired repertoire of various examples and images play a crucial role in problem scoping, ideation, and prioritising (Lawson, Citation2005).

Ideation is strongly related to the inspiration sources. Earlier studies (e.g. Eckert & Stacey, Citation2003; Mete, Citation2006) have shown that sources of inspiration can be anything, material or immaterial. According to Mete (Citation2006), who has studied this in relation in apparel design in particular, the fashion industry uses concrete and conceptual approaches to inspiration sources. Designers can be inspired by materials; in this case, fabrics (Dasgupta, Hammett-Stabler, & McKelvey, Citation2011; Jones, Citation2011), or ideas are generated conceptually from nature, arts, or other products.

The sources of inspiration have also been proven to have different roles in the design process; for example, expanding the idea space and keeping the design in context (Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000, Citation2003). Sources of inspiration refer to all conscious use of previous designs and other objects and images for the pursuit of design (Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000). Anything can inspire the birth of new design ideas, and designers appear to use sources of inspiration for different purposes (Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000; Petre et al., Citation2006). Darke (Citation1979) refers to a ‘group of related concepts’ or self-generated sources of inspiration in the ideation process as the ‘primary generator’ (p. 38). It can be seen as the designer's individual style when certain identifiable elements, qualities or expressions are consistently used. Throughout their career, experienced designers collect an extensive record of design cases that they use to inspire their projects. Experienced designers learn to effectively select and adapt such sources to the purposes of their design. When the use of sources is restricted, for example, in an experimental research setting, designers may use whatever they see in their immediate surroundings.

Inspiration has been divided into two categories: existing concrete and self-generated sources. Concrete sources include patterns, sketches, photographs, images of works of art, and decorative product materials (e.g. yarn and fabric samples). Self-generated sources are mental, such as memories, narratives, and visions of nature or everyday life. Both recall experiences and memories to envision a design during ideation (Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000; Petre et al., Citation2006). Furthermore, Petre et al. (Citation2006) found that in order to complete constrained design tasks, knitwear designers integrated inspirational elements into their detailed designs using three kinds of strategies: selection (choosing design elements), adaptation (interpreting selected elements), and transformation (manipulating elements within the particular composition).

2.2. Design elements and sketching

Within the fields of textiles and fashion, the dual space search model refers to the designer's manipulation of composition space and construction space (Seitamaa-Hakkarainen & Hakkarainen, Citation2001). Visual design elements such as size, shape, colour, and pattern are part of composition while construction space involves materials, texture and production procedures. Multiple visual elements are manipulated in order to provide aesthetically pleasing garments (Lee & Jirousek, Citation2015). Dasgupta et al. (Citation2011) note that, when developing design ideas, designers utilise the outline, cuts, and texture of various garment elements. Designing visual elements (such as silhouette space, lines and cuts, shape, form, light, colour, texture, and pattern) and principles (rhythm, scale, harmony, contrast, and proportion) are essential guidelines for all textile design fields.

In conceptual design, sketching guides the search for structures, idea generation, and testing of different solutions (Eisentraunt & Günther, Citation1997). Sketching is an integral part of design activity and the principal ‘thinking tool’ for the designer (Eisentraunt & Günther, Citation1997). When developing ideas, fashion designers produce many sketches, editing them and selecting the best one for further development. Using various visual representations, a designer generates alternative solutions and tests them before bringing the designed product to production (Seitamaa-Hakkarainen & Hakkarainen, Citation2001).

Conceptual sketches produced are primarily meant for the designer's own feedback and they are typically rather rough representations of the main abstract idea. The type of sketching appears to indicate how explicit or complete design ideas are (Eisentraunt & Günther, Citation1997; Goel, Citation1995). Goel (Citation1995) has analysed the role and development of sketching by distinguishing syntactic and semantic levels of drawings that can be transformed in a lateral or a vertical manner in the sketching process. Following Goel's idea (Citation1995), Seitamaa-Hakkarainen and Hakkarainen (Citation2000) abstracted two contrasting strategies of sketch development from the protocol data: horizontal and vertical sketch development. Horizontal sketch development indicates the move from one design idea to a different one without articulating either in depth whereas vertical development results in a more articulated and detailed version of the same idea. Similarly, Lee (Citation2017) observed that there are two phases in the fashion designer's sketching process. The first includes lateral transformation of sketches where the designer superficially interprets the inspirational source on paper without evaluating the ideas. During the second phase, the vertical transformation of the sketches includes refining, re-interpreting, and re-grouping the sketches in order to articulate sketches that are more detailed. In the following sections, we explain how we examined apparel designers’ variation in the idea development process by analysing the interaction and relationship between the kernel design ideas, the sources of inspiration and the role of sketching.

3. Participants and methods

3.1. Participants and experimental study

Three designers with similar educational and professional backgrounds voluntarily participated in the present study (they are henceforth referred to under aliases Jane, Laura, and Katy). All of them hold a bachelor's degree in fashion and clothing. They all have experience in designing clothes, making patterns, and sewing garments: Jane for 10 years, Laura for 14 years and Katy for 13 years. Jane and Laura both have their own clothing brand. Laura has also worked in two worldwide design houses for a total of six years. Katy has designed and manufactured custom-made clothes while working as a freelance illustrator.

We asked the participants to solve an authentic small-scale clothing ideation task; namely, to design a spring jacket for women by thinking aloud. The ideation design task was carefully chosen to satisfy a number of criteria that would reflect the characteristics of real-life design tasks. In particular, it was essential that the design task could: be solved in a relatively short time, approached from different perspectives, and resemble the kinds of tasks that the participants were familiar with in their professional field.

The design experiment was conducted in a location of the designers’ choice in order to enable as natural an environment for ideation as possible. Each participant chose to design at a studio or a workroom. The participants were also given the opportunity to choose the equipment they would like to utilise during the experiment. In the experiment setting, the designers were provided with 10 different photographs (five photographs of nature and five urban landscapes), as sources of inspiration, which they could voluntarily use during their ideation process. The researchers subjectively selected photographs that did not include any material related to fashion. The designers were asked not to include their own sources of inspiration. However, because of the location of the experiment setting, we could not eliminate other possible sources in the vicinity.

3.2. Research method and data-analysis

The present study was carried out using a thinking-aloud method, i.e. protocol analysis, following Ericsson and Simon's (Citation1993) protocol analysis technique. Accordingly, each designer was asked to think aloud from the beginning to end of the problem-solving. Although it may have been considered difficult for the participants to speak while sketching (Lee & Jirousek, Citation2015), all of them verbalised their thoughts fluently in this study (see also Seitamaa-Hakkarainen & Hakkarainen, Citation2001). There were only a few five to six second pauses in each participant's speech. Therefore, during the experiment, the researcher did not need to interfere in the participants’ actions in any manner.

The data collected consists of (1) verbal thinking aloud protocols, (2) video-recorded activities, (3) written and drawn material produced by the participants during the design sessions, and (4) post-design interview data. We collected, in total, 4 hours and 24 minutes of data that included protocol and video data and the post-design interviews. Afterwards, we transcribed the recorded protocols and the post-design interviews word-for-word and we observed and identified the design process (activities, sketches, and notes) in the videos at one minute intervals. In order to increase the reliability and validity of the data analysis, the verbal protocols were cross-referenced with the activities observed in the video recording as well as notes and sketches produced during the design session.

Result analysis is based on qualitative content analysis of the thinking aloud protocols in addition to problem-behaviour-graphs (PBGs) constructed for each designer based on the video and protocols. The graphs can be seen as a set of moves from one idea or design element to another design. The starting point of the analysis was an identification of design episodes on the basis of the participant's verbalised intentions (e.g. ‘I will … ’ or ‘I have to … ’). Every design idea or element specifically considered during that episode was then presented as a trace of moves in the graphs. PBG graphically describes each presented idea, source of inspiration and number of sketches produced. This analysis method reveals the various phases of the idea development process, the primary generators developed (see Darke, Citation1979), the cyclical nature of the ideation, and the ideas rejected. Thus, from the segmented video data, each sketch and idea development move enabled us to analyse the connection between sketching and adapting the design elements from the inspirational source. We could also review the data in relation to each idea transformed during the design process.

Secondly, we applied qualitative content analysis to the transcribed protocols, which were segmented into statements identifying main ideas; i.e. the meaning of the content (see Chi, Citation1997 regarding the segmentation of data). The analysis focused on the use of inspiration sources and the development of design ideas during sketching. The coding categories consisted of two main categories (further divided into sub-categories).

The Source of Inspiration category consisted of three sub-categories that explain what kinds of sources of inspiration the designers utilised or mentioned during their ideation: (1) concrete sources of inspiration (e.g. photographs, fabrics), (2) abstract sources of inspiration (e.g. mental images, memories), and (3) sources associated with the participant's own profession (e.g. brand ideologies, earlier designs, fabrics). Extricating the various inspiration sources from the data set made it easier to focus on the analysis of how the designers interpret and adapt them into new designs.

Next, for the second category Adaptation of Source, we applied the categorisation of Petre et al. (Citation2006; see also Eckert & Stacey, Citation2003). It consists of five sub-categories: (1) literal adaptation of the source (i.e. the source is directly copied into the design), (2) adaptation by simplification (e.g. inserting a detail from the source in the design), (3) abstraction (i.e. capturing the essence of the source), (4) modification (i.e. replacing, re-arranging, or combining source elements), and (5) association (i.e. an association is made with other visually similar elements that originated in a similar context; e.g. the source is ‘school’ and the designer adapts an element from that context into the design).

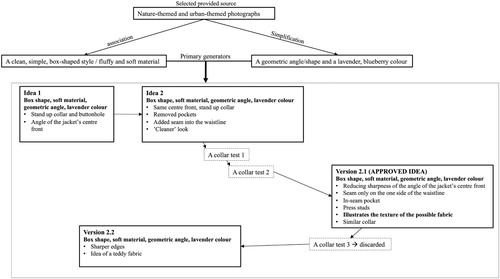

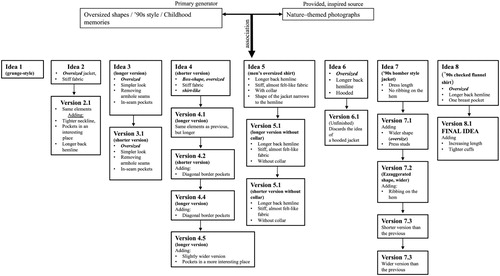

Finally, based on the PBG, we constructed more simple visual graphs for each designer that we called idea development diagrams. These diagrams represent the way the designers’ ideas were developed and the sketches produced. We also compared sketches to find possible similarities and/or a continuum of the designer's primary idea. This procedure was conducted individually for all three designers. Finally, we used the post-design interview data to confirm our interpretations.

4. Results

4.1. Developing kernel ideas based on the provided source

The participants used between 45 and 79 minutes to design (an average of 60 minutes). Each designer decided to use pencil and paper for sketching. There were differences in the number of sketches the designers produced and at what pace: Jane generated seven sketches, Laura 22 sketches, and Katy produced three sketches at a rather slow pace. All of the designers started their session by leafing through the provided photographs. There was variation in how much time the designers spent talking about the photographs before and during the sketching activity. Jane and Katy both referred to their selected sources in between different ideas multiple times while Laura kept the photos beside her during the design session without verbally referring to them after the very beginning.

The designers started with an original idea, then refining it with one version, created a new idea, moved back to one or more previous ideas, refined the current idea (the number of versions varied), combined elements between ideas, refined, analysed, and discarded ideas, and continued these activities until they were pleased with their outcome. The inconsistency between the participants’ ideation activity was mainly connected to the number of sketches produced.

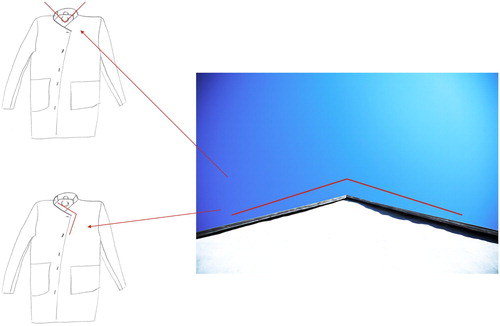

We observed that each participant utilised the provided sources in a varied manner. Jane's kernel ideas were derived from the photographs provided. She adapted the inspiration through association and simplification. At the beginning of her session, she noted that she normally does not find landscapes inspiring. However, against her own personal interests, Jane selected two of the photographs and put them aside (): a nature photo with flowers and an urban photo. From these photos, she adapted four different sources into her design ideas for outerwear. Two of the sources she adapted by association: 1. a clean box-shape for the overall shape of the jacket from the urban photograph, and 2. an association of fluffy and soft material from the flowers in the nature-themed photograph. The sources she adapted by simplification were 3. a lavender, blueberry colour from the nature-themed photograph and 4. a geometric angle/shape from the urban photo (into the idea of the jacket's collar, centre front and buttonholes).

Jane combined all of the sources chosen from the beginning of her session without separating them at any point. The adapted sources are visually represented in her final idea (). The association of a material did not change Jane's first idea about the jacket's overall look, but only gave an idea of the possible material to be used. Therefore, the structure of the material was mainly observable in her verbal delivery. Nor was the idea of the colour visually presented in the designer's sketches. Nevertheless, we considered colour to be a vital source for the designer because she talked about including a lavender colour into the final idea.

The second designer, Laura started her session by ‘vibing’ the provided photographs. She only talked about the nature-themed landscapes, noting that they reminded her of some childhood memories and an anorak-style outerwear. The adaptation of the sources in Laura's process occurred through association. Laura was the only one who did not literally confirm that she exploited the photographs provided during her ideation. However, it appeared that Laura had already developed a design concept, which was then supported by the nature-themed photographs. The association, adapted from the photographs, resonated with her primary generator of a vision of the nineties style oversized look. According to the verbal data, the nineties style is the participant's memories of the clothes she wore in the nineties: an anorak jacket, checked flannel shirts, band t-shirts, and a bomber jacket.

Laura: My designing started while I was “vibing” these [nature-themed] photos. I straight away had this kind of a nature excursion feeling about these. It easily takes my imagination to some sort of anorak type of style. Maybe it's some sort of childhood association of going into the woods wearing an anorak … like the nineties … when I wore oversized clothes … and band t-shirts …

The third designer, Katy, selected two photographs and moved the other ones to the side. The pictures left on her working desk were the same nature photo with flowers that Jane had selected and another black and white urban landscape with straight lines (). The colour palette (black and white, lavender) fascinated Katy. In addition, the expression of form (i.e. ’graphic straightness’ and ‘softness’) and the contrast between the two photos interested her. She adapted three sources via association and simplification into her ideas: 1. association of the clean graphic shape from the urban photo, 2. the soft material and shape from the nature photo, and 3. colour from the nature photo (by simplification). Furthermore, she used the urban photo to envision the shape of the jacket. She wanted to bring some softness into the idea by visualising a soft yet light material. She ended up changing the overall shape of the jacket into a curvier look that resonated with her primary generator of soft material (). The idea of the jacket's colour adapted by simplification from the provided photo was not visually presented in Katy's sketches, but the idea was carried along in her speech until the final idea.

4.2. Inspirational elements and sketching

As mentioned earlier, Laura did not verbally choose any of the provided inspirational sources while Jane and Katy both specifically chose two of the photographs as their inspiration. In terms of the source selection, we found this difference between the designers’ verbal statements interesting and therefore decided to present a more detailed report of Jane and Laura's processes. However, we are not reporting a thorough analysis of each step of the design process, simply a report of the main turning points in their ideation. Detailed analysis of the designers’ idea development processes revealed similarities between Jane and Katy. Therefore, we decided not to detail Katy's sketches. The only difference between Jane and Katy was that Katy developed fewer number of sketches (three sketches) and that her pace in drawing was slower compared to the other designers.

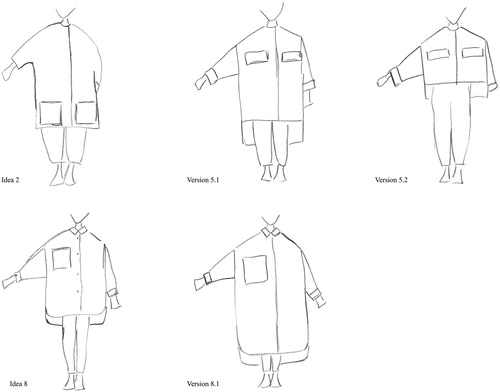

To illustrate the ideation processes of Jane and Laura, we formulated two main figures ( and ), in which the designers’ ideas and versions of the sketches are presented in chronological order. These figures illustrate the production of sketches (their number and order), the manifestation of the primary generator, and the sources adapted. Furthermore, the figures reveal how the ideas in the designers’ sketches were transformed horizontally or vertically. When the designers transformed sketches horizontally, it represented a new idea, whereas the versions of sketches developed vertically represent detailed versions of the same idea. We also decided to show pictures of their sketches to exemplify these adaptations.

4.2.1. Jane's transformation of ideas

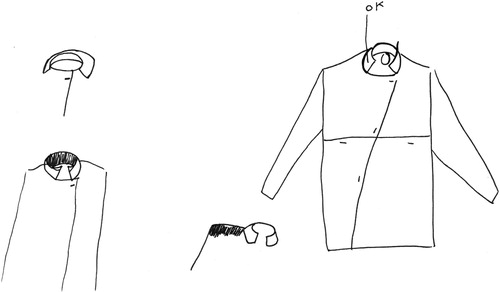

presents Jane's ideation and sketches. Jane started sketching to adapt the source into an idea. She already attached the idea of a box and a clean shape as well as furry and fluffy material with the lavender colour in the first version of Idea 1. In the first sketch (Idea 1, ), she started by adapting the geometric angle from the provided source into the collar and centre front of the jacket (). She also considered the shape of the jacket more important than the style. In this phase, sketching played an important role. The first interpretation of the inspirational source generates a representation (first sketch) that cumulatively aids the design. Further, Jane added two-pieced sleeves and the fluffy texture into the design but then noticed that the current idea reminded her of something she had seen before, so she decided to move ‘forward’ in designing.

Jane: [Idea 1] … this [urban photo] clearly gives me the idea of the collar and the buttonhole … I’ll start with the overall shape before I think about the style … reminds me of something previous I’ve designed. Maybe a two-pieced sleeve … from that [nature photo] the texture and otherwise, it would be like box-shaped …

At this point (Version 2.1), Jane determined the style of the jacket would be box-shaped with lowered shoulders. She reduced the angle of the centre front and removed the waistline seam from one side of the jacket, adding the idea of an in-seam pocket with a press stud to make it invisible. The collar is similar to the previous sketch but, in this version, Jane decided to illustrate the texture of the fabric for the first time. For Version 2.1, she also envisioned a collar but then discarded this idea.

[Version 2.1]: … the model has a lowered shoulder and box-shape … pocket is always needed … a cutting seam so the pocket would be hidden inside the seam here and with a press stud so you couldn't see it … the texture's from the photo [nature photo]. Maybe cashmere type of material …

4.2.2. Laura's transformation of ideas

presents all of Laura's sketches as well as her primary generator and the inspirational source. The first sketch (Idea 1), in her opinion, was not something worth refining. However, at the time of this very first idea, the designer already talked about a grunge-look that could be connected to her primary generator; namely, the designer's own vision of nineties style and an oversized look. Laura made two sketches of Idea 2. She started to visualise an oversized jacket made out of stiff fabric () and cultivated this idea in Version 2.1 with a tighter neckline and a longer back hemline. She talked about creating a shape that would just stand on its own. Somehow, the designer connected the idea of a stiff fabric into an almost sculpture-like vision.

Laura: … [Idea 2] would be nice to create a shape that somehow stands on its own. Like a giant jacket … I’ll cultivate this idea. I want the neckline a bit tighter. And a bit wider … longer from the back and shorter from the front [Version 2.1] …

[Idea 5]: … I want to go back to the jacket with a longer back hemline … now I’m thinking about the fabric and just what kind of opportunities I could have with it … I’m thinking about kind of a stiff fabric … like almost a felt-like fabric that would just stand on its own without bending … I suddenly started to envision an ‘80s type of design so that it narrows a bit towards the hemline … reminds me of a man's oversized shirt … and maybe without a collar [Version 5.1] … now I’ll do also a shorter version [Version 5.2] …

[Idea 8]: … the idea of a checked flannel shirt from the nineties … maybe a jacket from that … but more like a dress, a jacket dress … almost a tent-like shape … some other length maybe, could be like an ankle length … this must have something petite also … now I’m liking this idea … because I think this looks somehow new … something new and interesting [Version 8.1] …

5. Discussion

The thinking-aloud method provided us with the opportunity to access the designer's actual thoughts during the apparel ideation process. All three participants were able to verbalise their thoughts and, due to the post-design interviews, the designers were also given the chance to explain the main turning points in their ideation. Through our observation and the designers’ verbal thoughts, with the video data and the designers’ sketches, we were able to illustrate the relation between sketching and thinking. The design task in our experiment was formulated to match the aspects of design tasks in a real-life design situation. Concerning the limitations of the present study, however, one must take into account that our design experiments only captured a short section of a normally lengthy process.

Our findings suggest that there were both similarities and differences in how the provided sources stimulated the designers’ idea development. All the designers connected the inspirational source in the context of apparel design. The inspirational sources not only provided elements for the designers’ ideation but also kept the process within its context (cf. Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000). Jane and Katy started their ideation by adapting specific elements (e.g. colour, geometric shapes, fabric idea) through simplification and association. They carried the adapted elements from the beginning of the ideation until the final idea. We observed that the inspirational sources stimulated Jane and Katy's ideation by helping them create a kernel idea or primary generator. They both framed their primary generators around the photographs provided, which set the terms for their idea development. Conversely, Laura seemed to already have a design concept at the beginning of the experiment. The adaptation of the inspirational sources in her case was more intuitive and the sources reinforced her existent but vague idea. The adapted sources were carried along from the beginning of the ideation until the final idea in each of the designers’ processes.

Compared to earlier studies (Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000; Petre et al., Citation2006), we similarly observed that the external inspirational sources conjured self-generated sources such as designers’ memories and visions of materials that are essential in the field of apparel design. Each designer already included a suggestion for a fabric in the first jacket idea. In the present study, the role of the fabric was observed to be essential. Even if the designer did not have the fabric concretely at hand, she reflected on her professional experiences and visualised one. In Jane and Katy's processes, the provided photographs played a significant role as a stimulus for them to form an association and envision a soft fabric, which is an ability informed by the professional knowledge they have already gained. The knowledge of the characteristics of a fabric also set constraints on a designer's ideation; if she found the idea of the fabric somehow unsuitable, she either moved to a different idea of a jacket or altered the jacket's design to match the image of the material.

Further, the analysis of the designers’ ideation processes revealed the importance of sketching to adapt and transform inspirational elements into ideas. By sketching, the designers were able to: (a) see how the adapted inspirational elements acted in their ideas, (b) test whether the adapted element fit into the idea of the primary generator, and (c) merge different inspirational elements into one idea. For each designer, sketching appeared to be a vital ‘thinking tool’ (Eisentraunt & Günther, Citation1997), which interacted with her previous experiences but also helped to find fresh new ideas. The differences in the number of sketches produced did not seem to diminish the role of sketching in any designer's processes. According to Lee and Jirousek (Citation2015), fashion designers can move back and forth between previous sketches, developing ideas by combining elements from one sketch to another. In our study, the sketching process also revealed details of the iterative nature of the ideation process. The designers jumped from the current idea to a previous one, and flexibly detached and connected features. In addition, the designers were able to test both the aesthetic and technical features of the idea simply by drawing them on paper. For example, if an aesthetic feature of an idea did not fit within the context of their primary generator, the designer sketched a new version of the same idea to test whether it worked with a different detail.

6. Conclusion and further research

The results of this study could be applied in a clothing design course to offer examples of the ideation phase of the apparel design process. Design students could benefit from seeing illustrative examples of the ways in which design experts utilise visual material to support their ideation. As the present study shows, both immaterial and material sources of inspiration have a role in the design process. Our study also highlighted the important role of fabric materials and sketching. In addition, maintaining design ideas that are sensitive to the social, cultural, and technological environment opens up new horizons (see Eckert & Stacey, Citation2000; Petre et al., Citation2006). In order to develop new ways of teaching design, there is a need for further research on design expertise and ways of thinking (especially during the ideation phase) in order to clarify how inspirational sources are created at both the professional and educational level and offer a deeper understanding of the apparel domain. Mete’s (Citation2006) studies revealed two different approaches to the usage of inspirational sources in the fashion industry. As such, the role of fabric materials and concepts would also benefit from future examination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chi, M. T. H. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271–315.

- Cross, N. (2004). Expertise in design: An overview. Design Studies, 25(5), 427–441.

- Cross, N. (2006). Designerly ways of knowing. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Darke, J. (1979). The primary generator and the design process. Design Studies, 1(1), 36–44.

- Dasgupta, A., Hammett-Stabler, C. A., & McKelvey, K. (2011). Fashion design: Process, innovation and practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Eckert, C., & Stacey, M. (2000). Sources of inspiration: A language of design. Design Studies, 21(5), 523–538.

- Eckert, C., & Stacey, M. (2003). Adaptation of sources of inspiration in knitwear design. Creativity Research Journal, 15(4), 355–384.

- Eisentraunt, R., & Günther, J. (1997). Individual styles of problem solving and their relation to representations in the design process. Design Studies, 18(4), 369–383.

- Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Goel, V. (1995). Sketches of thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Howard, T., Culley, S. J., & Dekoninck, E. (2008). Describing the creative design process by the integration of engineering design and cognitive psychology literature. Design Studies, 29(2), 160–180.

- Jones, S. J. (2011). Fashion design. London: Laurence King Publishing.

- Jonson, B. (2005). Design ideation: The conceptual sketch in the digital age. Design Studies, 26(6), 613–624.

- Laamanen, T.-K., & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2014). Constraining an open-ended design task by interpreting sources of inspiration. Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, 13(2), 135–156.

- Lawson, B. (2005). How designers think? The design process demystified. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Lee, J. S. (2017). The role of sketches in fashion design – Focus on a case study of a professional designer’s process. Journal of Fashion Business, 21(3), 58–66.

- Lee, J. S., & Jirousek, C. (2015). The development of design ideas in the early apparel design process: A pilot study. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 8(2), 151–161.

- Mete, F. (2006). The creative role of sources of inspiration in clothing design. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 18(4), 278–293.

- Petre, M., Sharp, H., & Johnson, J. (2006). Complexity through combination: An account of knitwear design. Design Studies, 27(2), 183–222.

- Schön, D. A., & Wiggins, G. (1992). Kinds of seeing and their functions in designing. Design Studies, 13(2), 135–156.

- Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., & Hakkarainen, K. (2000). Visualization and sketching in the design process. The Design Journal, 3(1), 3–14.

- Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., & Hakkarainen, K. (2001). Composition and construction in experts' and novices' weaving design. Design Studies, 22(1), 47–66.