Abstract

Purpose: Speech and language pathology (SLP) for aphasia is a complex intervention delivered to a heterogeneous population within diverse settings. Simplistic descriptions of participants and interventions in research hinder replication, interpretation of results, guideline and research developments through secondary data analyses. This study aimed to describe the availability of participant and intervention descriptors in existing aphasia research datasets.

Method: We systematically identified aphasia research datasets containing ≥10 participants with information on time since stroke and language ability. We extracted participant and SLP intervention descriptions and considered the availability of data compared to historical and current reporting standards. We developed an extension to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist to support meaningful classification and synthesis of the SLP interventions to support secondary data analysis.

Result: Of 11, 314 identified records we screened 1131 full texts and received 75 dataset contributions. We extracted data from 99 additional public domain datasets. Participant age (97.1%) and sex (90.8%) were commonly available. Prior stroke (25.8%), living context (12.1%) and socio-economic status (2.3%) were rarely available. Therapy impairment target, frequency and duration were most commonly available but predominately described at group level. Home practice (46.3%) and tailoring (functional relevance 46.3%) were inconsistently available.

Conclusion : Gaps in the availability of participant and intervention details were significant, hampering clinical implementation of evidence into practice and development of our field of research. Improvements in the quality and consistency of participant and intervention data reported in aphasia research are required to maximise clinical implementation, replication in research and the generation of insights from secondary data analysis.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO CRD42018110947

Introduction

Speech and language pathology (SLP) for aphasia is a complex, multifaceted intervention delivered to a highly heterogeneous population across a range of possible clinical settings (Medical Research Council, Citation2008). Stroke survivors with aphasia present with individual language, social and cognitive case histories and unique stroke and aphasia profiles which impact on their therapy goals, rehabilitation, activities and participation in life after stroke (Brookshire, Citation1983; Douiri et al., Citation2017; Roberts, Code, & McNeil, Citation2003). Therapists differ in their level of experience (from those that are newly qualified to those with many years of experience) and post-qualification training (some participating in specialist conferences or training while others may not have that opportunity). Implementation of evidence-based SLP may be adapted to the local clinical culture, context or resources (Palmer, Witts, & Chater, Citation2018). For example, therapy assistants, family members or other trained volunteers may also be engaged to deliver rehabilitation programmes.

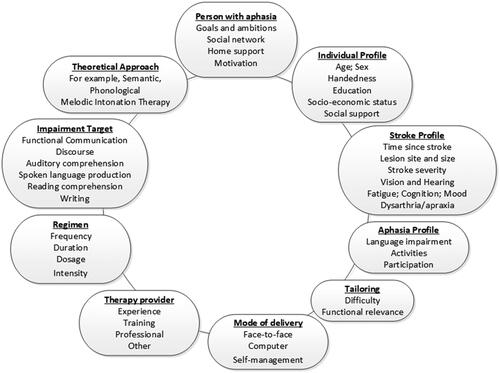

Clinically, therapists tailor interventions to the individual, reflecting the patient’s goals, functional needs, remaining language skills and pattern of impairments. Availability of services in the context of increasing fiscal constraints on rehabilitation provision is also a consideration. The frequency (speech-language therapy days per week), intensity (hours per week), overall duration of input (total weeks) and dosage of therapy regimen (total hours) need to be adapted to patients’ preferences, tolerance, mental capacity and support by significant others (for example, regarding transport or home practice) (). Strong theoretical reasons and early empirical evidence suggest that some of the factors listed above may impact on stroke rehabilitation and recovery (Brady, Kelly, Godwin, Enderby, & Campbell, Citation2016; Van Peppen et al., Citation2004) yet reporting of these features in the research context appears arbitrary.

Increasingly, aphasia healthcare professionals and researchers are working towards greater consistency in their terminology, co-ordination of effort and research transparency (Brookshire, Citation1983; Roberts et al., Citation2003; Wallace et al., Citation2018; Worrall et al., Citation2016). Clinically, intervention descriptions need to be transparent and provide sufficient detail (rationale, processes, materials, regimen, tailoring and importance of adherence) to inform patients, family members and healthcare professionals about SLP (Brady, Clark, Dickson, Paton, & Barbour, Citation2011; Frost, Levati, McClurg, Brady, & Williams, Citation2017; Hilton, Leenhouts, Webster, & Morris, Citation2014; Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, Citation2016; Lawton, Sage, Haddock, Conroy, & Serrant, Citation2018) (). This level of understanding is essential if we are to support treatment fidelity (e.g. Lawton et al., Citation2018; Ball, de Riesthal, & Steele, Citation2018; Roulstone, Citation2015). The agreed aphasia research core outcome set ensures that future research will consider the effectiveness of interventions in relation to the outcomes considered important to people with aphasia, their families and healthcare professionals. Shared core outcomes also support greater co-ordination across aphasia research activities and will facilitate future secondary data analysis efforts (Brookshire, Citation1983; Roberts et al., Citation2003; Wallace et al., Citation2018; Worrall et al., Citation2016).

Interpretation of SLP research evidence, clinical implementation and secondary data analysis however is hampered by the limited transparency relating to the participant and intervention descriptions (Roulstone, Citation2015; Brady et al., Citation2016). Where descriptions are poor, replication and clinical implementation of these interventions becomes a challenge. Greater transparency facilitates replication in research, generalisation to clinical settings, and continued development of the field of science (Glasziou et al., Citation2014; Julious et al., 2014; Bernhardt et al., Citation2016; Brady et al., Citation2018; Downing et al., Citation2016; Jørgensen et al., Citation2000). Better reporting of participants and interventions supports timely, cost effective, secondary data analyses which can lead to new insights into the effectiveness of therapy or the identification of previously hidden biases (Lee, Alexander, Hammill, Pasquali, & Peterson, Citation2001; Downing et al., Citation2016). Guidelines have been developed to improve the quality of research design and complex intervention reporting (Stewart et al., Citation2015). The adoption of these guidelines in aphasia research will in turn reduce future aphasia research waste (Chalmers & Glasziou, Citation2009).

People with aphasia are a highly heterogeneous population, known to experience barriers to research participation (Boden-Albala et al., Citation2015). Thus, every effort should be made to gain new insights through the re-use of existing research data though secondary data meta-analysis. Inconsistent participant description however impedes the generalisability of findings, prevents clinicians’ consideration of whether research participants reflect their own caseload and precludes secondary data analysis from combined datasets. Robust subgroup analysis on a highly heterogeneous group requires a very large sample size with sufficient information on individual participant profiles (Altman et al., Citation2001).

Over the last three decades, there have been calls for greater consistency in participant descriptions in aphasia research (Brady et al., Citation2014; Brookshire, Citation1983; Hallowell, Citation2008; Roberts et al., Citation2003). Since 1983 audits of published papers have highlighted participant description inconsistencies across aphasia research reports (Brookshire, Citation1983). A later audit of aphasia articles published from 2001 to 2002, found that only half reported 9 of 43 variables considered: age (92%), sex (91%), lesion location (83%), time since onset (83%), aphasia severity (82%), aetiology (80%), type of aphasia (78%), handedness (60%) and education (55%) (Roberts et al., Citation2003). A more recent review reported that two thirds of SLP for aphasia randomised controlled trials (RCTs) had inadequate between-group participant comparison data at baseline (Brady et al., Citation2016).

Recent methodological developments have provided SLP research with much needed infrastructural and terminology support to describe (and evaluate) SLP interventions for aphasia (Hoffmann et al., 2014, Medical Research Council, Citation2008). More than 23 different approaches to SLP for aphasia after stroke have been evaluated in the context of a RCTs (Brady et al., Citation2016). Many more have been examined within alternative research designs. Overly simplistic or incomplete descriptions of participants and interventions in aphasia research also negatively impact on international treatment guidelines. We considered to what extent participants and interventions were described in the aphasia rehabilitation recommendations from the Australian and the UK national stroke clinical guidelines () (Rohde, Worrall, & Le Dorze, Citation2013, Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, Citation2016). In contrast with the recommendations made relating to rehabilitation for arm function after stroke () (Rohde et al., Citation2013, Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, Citation2016), the recommendations relating to aphasia rehabilitation lacked specific intervention details (such as intensity, timing and dosage) and target population information (such as severity and age). The paucity of intervention and target population details may be symptomatic of the inadequate description of participants and interventions in aphasia research to date.

Table I. Overview of therapy recommendationsTable Footnote* for aphasia (a) and arm function (b) from two exemplar national stroke clinical guidelines (Intercollegiate Stroke Working (ISW) Party, Citation2016; Stroke Foundation, Citation2017).

Aim

In this article, we describe what participant and intervention descriptors were available following data extraction from aphasia datasets, systematically gathered and synthesised in the RELEASE research archive.

Method

We systematically identified pre-existing aphasia datasets with individual participant data (IPD) using a prespecified protocol (PROSPERO CRD42018110947), reported in-depth elsewhere (Brady et al., Citation2020). Briefly, following a systematic review of the literature using a range of electronic databases, we identified and invited the contribution of all datasets which included IPD on at least 10 people with aphasia following stroke, detailing the aphasia severity (measured by functional language use, overall aphasia severity, expressive language, auditory comprehension, reading comprehension or writing) and time since stroke. Most study designs with suitable ethical permissions were eligible for inclusion. We did not include qualitative or aggregated group data. All identified records were screened for eligibility. Abstracts and full texts were independently reviewed by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by a third. Research teams that contributed their data to the RELEASE database were invited to participate in the collaboration. In addition, relevant IPD available in the public domain was extracted and included. For all included datasets, we extracted information on the participants and (where applicable) SLP interventions using relevant reporting checklists (Hoffmann et al., 2014) (). We extracted information on each dataset from published and unpublished reports, further supplemented with information gathered through direct communication with the primary researchers.

Table II. Participant and speech and language pathology intervention data extraction items.

We extended the original Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist for our data extraction purposes (Hoffmann et al., 2014). The TIDieR checklist encourages detailed narrative descriptions of interventions’ rationale, theory or therapy goals (relating to the “WHY” checklist item) and the materials and procedures used (relating to the “WHAT” checklist item). Detailed information on these items is essential to replication and clinical implementation of an intervention (Hoffmann et al., 2014). For our purposes however, the disparate narrative descriptions of SLP interventions extracted from study reports were not conducive to data synthesis, omitted specific classification of the SLP approach which in turn, hindered meaningful secondary data analysis. Where details were available, an experienced speech and language pathologist grouped similar approaches and assigned interventions to one or more category labels based on (a) the role in the study design (social support attention control, SLP, conventional therapy), (b) theoretical approach underpinning the intervention and (c) language impairment targeted. Preliminary categorisations were shared with the RELEASE collaborators (n = 68) (comprising contributing aphasia trialists and investigators) for review, comment and agreement via email. A videoconference supported further discussion to resolve any discrepancies in categorisation. During this discussion, two additional theoretical approaches were added; verbal therapy and multimodal therapy (Pierce, O'Halloran, Togher, & Rose, Citation2019). Thus, a total of nine theoretical categories and seven language impairment target categories were agreed upon. These were not mutually exclusive but reflected different ways of describing highly complex interventions (Brady et al., Citation2019). Where intervention descriptions were incomplete, classifications were difficult or only partially possible. Some interventions for example, were only categorised by their language impairment target but not the theoretical approach.

Result

Our systematic search of the literature generated 11 314 records of which we screened 2341 relevant abstracts and 1131 full texts. We invited contributions from 698 potentially eligible datasets and received 75 electronic dataset contributions (3940 IPD) and extracted IPD from an additional 99 public domain datasets (1988 IPD). Thus, our database included 174 datasets (91 referring to an SLP intervention; 45 RCTs) representing 5928 people with aphasia following stroke. Where details were available, data collection took place from 1973 to 2016 or was published between 1973 and 2017.

Participants

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria were available for two-thirds of the 174 datasets (115; 66%). Selection criteria described pre-existing neurological damage (85; 48.9%); cognitive impairment (100; 57.5%); depression (62; 35.6%); significant hearing impairment (82; 47.1%); visual impairment (35; 20.1%); dysarthria (19; 10.9%) and apraxia of speech (34; 19.5%).

Our RELEASE inclusion criteria specified IPD on time since stroke and aphasia severity (or language impairment). Most datasets had details of participants’ age (97.1%) and sex (90.8%) but other participant descriptors were less frequently described (for example, living context (21/174 datasets, 12.1%; 701 IPD)). Socio-economic status was available for 175 IPD (4/174 datasets, 2.3%) but additional (non-aggregatable) data were also available such as occupation or occupational status prior to or following stroke (1626 IPD) ().

Table III. Participant descriptors in datasets.

We lacked handedness information for a third of participants (2049 IPD, 34.6%) (). Information on the index stroke and co-existing health issues were limited. Whether the index stroke was a first or subsequent stroke (45/174 datasets; 25.8%) and stroke severity at baseline (measured using National Institute of Health Stroke Scale [8/174 datasets; 4.6%], modified Rankin Scale (Bonita & Beaglehole, Citation1988) [6/174 datasets; 3.4%] or Barthel Index (Wade & Collin, Citation1988) [5/174 datasets; 2.9%]) was seldom available.

Participants’ mono- or multilingualism (and the languages spoken) was rarely available (12/174; 6.9%; 526 IPD) though the language of data collection highlighted a predominance of English-language datasets (3162/5928; 53.3%). The remainder of data was collected across 22 other languages with German (420 IPD), the next most frequent data collection language. Participants’ living context during the intervention period (and thus a reflection of their social support and functional practice opportunities) was only available for 701 participants (21/174 datasets; 12.1%) though the context of SLP was available for most (65/67; 97%).

Information on participants’ age was slightly more available than previously reported (up from 91–92% to 97%; ). Other potentially important data items highlighted in previous audits (Brookshire, Citation1983, Roberts et al., Citation2003) were also unavailable in the datasets; handedness (63.8%), multilingualism (6.9%), occupation (17%), vision (20%), hearing (52%), stroke severity (4.6%), and prior stroke (25.9%) (). Other rarely available information that we extracted was socio-economic status (2.3%) and ethnicity (13.8).

Table IV. Descriptions of aphasia research participants; comparison of data availability.

Interventions

Approximately half of the RELEASE datasets referred to an SLP intervention (91/174, 52.3%; 2746 IPD; 46.3%). Only 67 (2330 IPD) sought to evaluate the benefit of SLP by capturing language data both prior to and following the intervention. We considered the completeness of those 67 SLP intervention descriptions (). Eight SLP intervention studies (11.9%, 529 IPD, 22.7%) described therapy only in very general terms (e.g. “conventional therapy”). More detailed categorisation was not possible. Using our extended TIDieR framework, we were able to categorise 45 of the 67 interventions by their theoretical approach (67% of the datasets; 838/2330 IPD, 35.9%) and 41 by their impairment target. One intervention could target more than one aspect of language recovery and so categories were not mutually exclusive. Spoken language impairment was most commonly targeted (41 interventions, of which 30 interventions targeted naming). Few intervention descriptions mentioned targeting reading and writing recovery ().

Table V. Descriptions of speech and language pathology interventions for aphasia after stroke (RELEASE dataset) using an extended TIDieR framework.

Other therapy descriptors were also extracted (where available) including therapy provider, mode of delivery, context, therapy regimen and tailoring (). Information on the therapy frequency, duration, intensity and dosage information was available for most interventions at group level (). Tailoring of SLP to the individuals’ level of language difficulty was described by 42 of the datasets investigating interventions (62.7%; 1145 IPD). A third of datasets (22 datasets; 649 IPD) described tailoring SLP for functional relevance but few mentioned the prescription of home practice tasks or referred to measures of adherence, elements closely linked to the dosage of an intervention.

Methodological details

Modifications to the therapy protocol were rarely described. Methodological details such as the date of study entry (79/174; 45.4%), a full account of participant dropouts (a third of datasets described dropouts) and the use of blinded outcome assessors are important markers of research methodological quality (unreported for 92/174; 52.9%). Similarly, randomisation details including adequate sequence generation (28/45 RCTs; 62.2%) and concealment of allocation (21/45 RCTs; 46.7%) were available for some of the RCTs.

Discussion

Inadequate descriptions of participants in aphasia research has continued over an extended period of time (Brookshire, Citation1983; Roberts et al., Citation2003; Brady et al., Citation2014). In our more detailed approach to data retrieval, we extracted data from both published papers, unpublished sources of information and directly from the primary researchers. We also found gaps in participant information availability. Despite access to IPD datasets, descriptions of SLP interventions were rarely available at IPD level. Most were only available at group level and often lacked information on an intervention’s theoretical approach or tailoring of materials for functional relevance to the participants. Few datasets described methodological details such as study withdrawals. Study withdrawals amongst a stroke survivor population are not uncommon. Aphasia researchers should be encouraged to report whether there were study withdrawals (with reasons) because of the valuable insights this may generate into the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention. Despite the advances made across aphasia research in recent times, key participant, intervention and methodological details are lost to the research process.

We adopted a systematic approach to the identification of IPD datasets with no exclusions by date, language or publication status. Only those IPD datasets meeting our inclusion criteria, contributed by the primary research team or available in the public domain were included (Brady et al., Citation2019). Our RELEASE inclusion criteria which specified aphasia following stroke and IPD on time since stroke and language impairment may have excluded datasets with particularly poor participant and intervention descriptions, which failed to report these and other data items. Other datasets also exist that were not contributed to our database; those that were still in use by the primary researchers, researchers that we failed to establish contact with, datasets that were of poorer quality and those that that the primary researchers declined or were unable to share.

The increasing availability of checklists support high quality reporting of complex interventions such as SLP for aphasia, methodological factors which reduce the risk of bias and other research design features (EQUATOR Network, Citation2014). For our database, we extended the TIDieR checklist to categorise therapy interventions by (i) impairment target and (ii) theoretical approach to support a comprehensive, transparent description of interventions for aphasia, meaningful data synthesis, meta-analysis and ultimately implementation in clinical settings. We propose, in the context of SLP interventions for aphasia, the continued use of this extension to the TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al., 2014). In our study, the classification of SLP for aphasia using these categories was feasible and supported our data extraction and secondary data analysis.

Research implications

Detailed description of participants and interventions in aphasia research supports clinical implementation and secondary analysis insights. Despite previous calls to improve the quality of aphasia research reports, we found that many participants and SLP intervention details were unavailable, even when attempts were made to retrieve that information directly from the primary research teams. We acknowledge the importance of balancing the burden of data collection on participants and researchers and the need to gather a core dataset or meet reporting standards. However, in order to maximise the benefits of our research efforts and funding, to improve clinical practice and our field of science through a reduction of research waste, we need to gather and share information about our participants and SLP interventions. Steps should be taken now to reduce further loss of data.

Clinical implications

In our specialist field of research, amongst a heterogeneous population who experience barriers to research participation and complex individually tailored interventions, it is vital that we maximise the use of any research data gathered. Reuse of existing datasets can support important secondary data analysis and novel exploration of new research questions while minimising research waste. Better participant description will inform therapists more clearly about the generalisability of the research findings to their clinical population and candidacy for new intervention approaches. Better reporting of interventions will provide therapists with sufficient information to ensure that effective interventions within the research context might be delivered as intended in the clinical setting thus achieving maximal gains for people with aphasia. Additional challenges are likely to remain in ensuring the implementation of effective therapy across “real-world” clinical settings, but these are beyond the scope of this particular manuscript.

We acknowledge that, in the context of a primary research study, some participant and intervention descriptors may be less centrally relevant to the interpretation of that study’s findings. Other descriptors are only recently being recognised as potentially relevant factors in recovery (e.g. socioeconomic status). Multidisciplinary consensus is required on a core dataset for participant and intervention reporting in aphasia research which is consistently adopted in future aphasia research activities. We plan to take this forward within the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists (www.aphasiatrials.org). Consistent, high quality reporting will enhance the transparency of research evidence, support clinical replication and inform clinical guidelines which will in turn, benefit people with aphasia, their families and the healthcare professionals that work with them.

Conclusions

Current descriptions of participants and SLP interventions for aphasia after stroke are incomplete, restricting the reach of research findings, transparency, implementation and secondary data analysis. Our proposed extension to TIDieR categories will support more transparent description of SLP interventions in research reports.

Disclaimer

This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, CCF, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme, the Department of Health, the Tavistock Trust for Aphasia, the Chief Scientist Office or the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates.

Author Contributions

MB: Conceived, designed and led the grant application and study, assessed the risk of bias, drafted and finalised the final report; MA1, AB, EG, KH, JH, SH, DH, TK, ACL, BMacW, RP, CP, SAT, EVB, LW: Co-applicants and contributors to the grant application; FB, MG, LMTJ, MLR, IvdM: Named collaborator on grant application; MB, KVB, LRW: Screened records, abstracts and full titles, extracted data, checked data extraction and risk of bias; KVB, LRW: Retrieved papers; MA2, FB, AB, CB1, CB2, SB, DAC, TBC, MdiP-B, PE, JF, FLG, MG, BG, EG, KH, JH, SH, PJ, EJ, LMTJ, MK, EYK, EMK, AP-HK, TK, ML, MALP, ACL, BL, APL, RRL, AL, BMacW, RSM, FM, IM, MM, RN, EN, N-JP, RP, IP, BFP, IPM, CP, TPJ, ER, MLR, CR, IR-F, MBR, CS, BS, JPS, SAT, MvdS-K, IvdM, EV-B, LW, HHW: Contributed IPD primary data; LJW: Led and conducted the statistical analysis; MA1: Contributed to the statistical analysis, SH: Co-ordinated and facilitated patient and public involvement in the study; NH: Advised on the statistical analyses. All authors were involved in interpretation of the results, reviewing and approving of the final report.

Conflict of interest

Marian Brady reports grants from Chief Scientist Office (CSO), Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, grants from EU Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) funded Collaboration of Aphasia Scientists (IS1208 www.aphasiatrials.org), and grants from The Tavistock Trust for Aphasia during the conduct of the study, and is a member of the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists.

Audrey Bowen reports that data from her research is included within the analyses in the RELEASE report. Her post at the University of Manchester is partly funded by research grants and personal awards from NIHR and Stroke Association.

Caterina Breitenstein reports grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) during the conduct of the study.

Erin Godecke reports Western Australian State Health Research Advisory Council (SHRAC) Research Translation Project Grants RSD-02720; 2008/2009 during the conduct of the study.

Neil Hawkins reports grants from National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study.

Katerina Hilari reports grants from The Stroke Association, grants from European Social Fund and Greek National Strategic Reference Framework, and grants from The Tavistock Trust for Aphasia outside the submitted work.

Petra Jaecks reports a PhD grant from Weidmüller Stiftung.

Brian MacWhinney reports grants from National Institutes of Health.

Rebecca Marshall reports grants from National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, NIH, USA during the conduct of the study.

Rebecca Palmer reports grants from NIHR senior clinical academic lectureship, grants from NIHR HTA, and grants from Tavistock Trust for Aphasia outside the submitted work.

Ilias Papathanasiou reports funding from European Social Fund and Greek National Strategic Reference Framework.

Jerzy Szaflarski reports personal fees from SK Life Sciences, personal fees from LivaNova Inc, personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from NeuroPace Inc, personal fees from Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Inc, grants and personal fees from SAGE Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from UCB Pharma, grants from Biogen, grants from Eisai Inc, and other from GW Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work.

Shirley Thomas reports research grants from NIHR and The Stroke Association outside the submitted work.

Ineke van der Meulen reports grants from Stichting Rotterdams Kinderrevalidatiefonds Adriaanstichting, other from Stichting Afasie Nederland, other from Stichting Coolsingel, and other from Bohn Stafleu van Loghum during the conduct of the study.

Linda Worrall reports a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

All other authors have declared no competing interests

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.4 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1762000

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altman, D.G., Schulz, K.F., Moher, D., Egger, M., Davidoff, F., Elbourne, D., … Lang, T, & the CONSORT GROUP (2001). The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134, 663–694. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012

- Ball, A.L., de Riesthal, M., & Steele, R.D. (2018). Exploring treatment fidelity in persons with aphasia autonomously practicing with computerized therapy materials. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 27, 454–463. doi:10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0204

- Bernhardt, J., Borschmann, K., Boyd, L., Thomas Carmichael, S., Corbett, D., Cramer, S.C., … Ward, N. (2016). Moving rehabilitation research forward: Developing consensus statements for rehabilitation and recovery research. International Journal of Stroke, 11, 454–458. doi:10.1177/1747493016643851

- Boden-Albala, B., Carman, H., Southwick, L., Parikh, N.S., Roberts, E., Waddy, S., & Edwards, D. (2015). Examining barriers and practices to recruitment and retention in stroke clinical trials. Stroke, 46, 2232–2237. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008564

- Bonita, R., & Beaglehole, R. (1988). Modification of Rankin Scale: Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke, 19, 1497–1500. doi:10.1161/01.STR.19.12.1497

- Brady, M.C., Ali, M., Fyndanis, C., Kambanaros, M., Grohmann, K.K., Laska, A.C., … Varlokosta, S. (2014). Time for a step change? Improving the efficiency, relevance, reliability, validity and transparency of aphasia rehabilitation research through core outcome measures, a common data set and improved reporting criteria. Aphasiology, 28, 1385–1392. doi:10.1080/02687038.2014.930261

- Brady, M.C., Ali, M., VandenBerg, K., Williams, L.J., Williams, L.R., Abo, M., … Wright, H.H. (2020). RELEASE: a protocol for a systematic review based, individual participant data, meta- and network meta-analysis, of complex speech-language therapy interventions for stroke-related aphasia. Aphasiology, 34, 137–157. doi:10.1080/02687038.2019.1643003

- Brady, M.C., Clark, A.M., Dickson, S., Paton, G., & Barbour, R.S. (2011). Dysarthria following stroke: the patient’s perspective on management and rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25, 935–952. doi:10.1177/0269215511405079

- Brady, M.C., Godwin, J., Kelly, H., Enderby, P., Elders, A., & Campbell, P. (2018). Attention control comparisons with SLT for people with aphasia following stroke: methodological concerns raised following a systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 32, 1383–1395. doi:10.1177/0269215518780487

- Brady, M.C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (6). Art. No.: CD000425. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

- Brookshire, R.H. (1983). Subject description and generality of results in experiments with aphasic adults. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48, 342–346. doi:10.1044/jshd.4804.342

- Chalmers, I., & Glasziou, P. (2009). Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 114, 1341–1345. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c3020d

- Douiri, A., Grace, J., Sarker, S.-J., Tilling, K., McKevitt, C., Wolfe, C.D.A., & Rudd, A.G. (2017). Patient-specific prediction of functional recovery after stroke. International Journal of Stroke, 12, 539–548. doi:10.1177/1747493017706241

- Downing, N.S., Shah, N.D., Neiman, J.H., Aminawung, J.A., Krumholz, H.M., & Ross, J.S. (2016). Participation of the elderly, women, and minorities in pivotal trials supporting 2011-2013 U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals. Trials, 17, 199. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1322-4

- EQUATOR Network. (2014). Retrieved from www.equator-network.org

- Frost, R., Levati, S., McClurg, D., Brady, M., & Williams, B. (2017). What adherence measures should be used in trials of home-based rehabilitation interventions? A systematic review of the validity, reliability, and acceptability of measures. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98, 1241–1256. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2016.08.482

- Glasziou, P., Altman, D.G., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Clarke, M., Julious, S., … Wager, E. (2014). Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. The Lancet, 383, 267–276. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X

- Hallowell, B. (2008). Strategic design of protocols to evaluate vision in research on aphasia and related disorders. Aphasiology, 22, 600–617. doi:10.1080/02687030701429113

- Hilton, R., Leenhouts, S., Webster, J., & Morris, J. (2014). Information, support and training needs of relatives of people with aphasia: Evidence from the literature. Aphasiology, 28, 797–822. doi:10.1080/02687038.2014.906562

- Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, (2016). National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke. Fifth Edition. Retrieved from https://www.strokeaudit.org/Guideline/Full-Guideline.aspx

- Jørgensen, H.S., Kammersgaard, L.P., Houth, J., Nakayama, H., Raaschou, H.O., Larsen, K., … Olsen, T.S., et al. (2000). Who benefits from treatment and rehabilitation in a stroke Unit? A community-based study. Stroke, 31, 434–439. doi:10.1161/01.STR.31.2.434

- Lawton, M., Sage, K., Haddock, G., Conroy, P., & Serrant, L. (2018). Speech and language therapists’ perspectives of therapeutic alliance construction and maintenance in aphasia rehabilitation post-stroke. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53, 550–563. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12368

- Lee, P.Y., Alexander, K.P., Hammill, B.G., Pasquali, S.K., & Peterson, E.D. (2001). Representation of Elderly Persons and Women in Published Randomized Trials of Acute Coronary Syndromes. JAMA, 286, 708–713. doi:10.1001/jama.286.6.708

- Medical Research Council. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group (1995). Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The New England Journal of Medicine, 333, 1581–1587.

- Palmer, R., Witts, H., & Chater, T. (2018). What speech and language therapy do community dwelling stroke survivors with aphasia receive in the UK?. PLoS One, 13, e0200096. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200096

- Pierce, J.E., O'Halloran, R., Togher, L., & Rose, M.L. (2019). What is meant by “Multimodal Therapy” for aphasia? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28, 706–716. doi:10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0157

- Roberts, P., Code, C., & McNeil, M. (2003). Describing participants in aphasia research: Part 1. Audit of current practice. Aphasiology, 17, 911–932. doi:10.1080/02687030344000328

- Rohde, A., Worrall, L., & Le Dorze, G. (2013). Systematic review of the quality of clinical guidelines for aphasia in stroke management. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 19, 994–1003. doi:10.1111/jep.12023

- Roulstone, S. (2015). Exploring the relationship between client perspectives, clinical expertise and research evidence. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 211–221. doi:10.3109/17549507.2015.1016112

- Stewart, L.A., Clarke, M., Rovers, M., Riley, R.D., Simmonds, M., Stewart, G., & Tierney, J.F. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses of individual participant data: The PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA, 313, 1657–1665. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3656

- Stroke Foundation (2017/2019). Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. Melbourne Australia.

- Van Peppen, R.P., Kwakkel, G., Wood-Dauphinee, S., Hendriks, H.J., Van der Wees, P.J., & Dekker, J. (2004). The impact of physical therapy on functional outcomes after stroke: what’s the evidence?. Clinical Rehabilitation, 18, 833–862. doi:10.1191/0269215504cr843oa

- Wade, D.T., & Collin, C. (1988). The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? International Disabilities Studies, 10, 64–67. doi:10.3109/09638288809164105

- Wallace, S.J., Worrall, L., Rose, T., Le Dorze, G., Breitenstein, C., & Hilari, K. (2018). A core outcome set for aphasia treatment research: The ROMA consensus statement. International Journal of Stroke, 14, 180–185. http://doi.org/10.1177/1747493018806200

- Worrall, L., Simmons-Mackie, N., Wallace, S.J., Rose, T., Brady, M.C., Kong, A.P.H., … Hallowell, B., et al. (2016). Let’s call it “aphasia”: Rationales for eliminating the term “dysphasia”. International Journal of Stroke, 11, 848–851. doi:10.1177/1747493016654487