Abstract

Purpose: There has been limited academic exploration of the history of speech-language pathology (SLP). This article uses oral histories to explore the experiences reported by speech-language pathologists who began to practise in Australia and Britain, two politically related, but geographically very distant and distinct countries, in the first three decades after the Second World War.

Method: Archived oral history transcripts from eight Australian and sixteen British speech-language pathologists were analysed using thematic network analysis (TNA).

Result: Two global themes are reported, “personal stories” and “professional stories”. Transcripts revealed the ways in which participants negotiated the social and cultural expectations of their time and place and how they developed professional identity and autonomy as their careers progressed. While there were many commonalities, there were both between- and within-group differences in the ways the two cohorts reported the details of their career progression.

Conclusion: This article offers a picture of the challenges and experiences of Australian and British speech-language pathologists in the second half of the twentieth century. It highlights some of the changes over time and forms the basis for comparison with current working practices in the two countries.

Introduction

The history of some health professions, notably doctors and nurses (e.g. Cooter & Pickstone, Citation2003; Bellman, Boase, Rogers, & Stutchfield, Citation2018), has received extensive scholarly attention. There has, however, been limited academic exploration of the history of speech-language pathology (SLP, previously called speech therapy), with the exception of key works by Rockey (Citation1980), Eldridge (Citation1968) and Duchan (Citation2005). Rockey’s work outlines the development of British SLP across the nineteenth century. Eldridge overviews international developments in SLP before 1970, with valuable material on Australia and Britain. Duchan’s well-established website provides a wide range of information on the history of SLP especially in America, although this has limited content post-2000, and only one entry (Porteous, Citation2003) on Australia. Other histories include an outline of the first years of the Australian professional body (Eldridge, Citation1965), a booklet to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) in Britain (Robertson, Kersner, & Davis, Citation1995), content analyses of the British professional journal from 1935 to 2015 (Armstrong & Stansfield, Citation1996; Stansfield & Armstrong, Citation2016; Armstrong, Stansfield, & Bloch, Citation2017) and posters outlining Australian history (McDougall, Citation2009a; Speech Pathology Australia [SPA], Citation2009, Citation2019).

Eldridge (Citation1965) states that the first SLP clinic in Australia was established in 1931, although Logue and Conradi (Citation2010, Citation2018) suggest that around 1918–1919 the Australian Lionel Logue worked with ex-servicemen who had speech and voice disorders as a result of shell shock and gas attacks, prior to his travelling to Britain. Indeed contemporary newspaper reports (e.g. the West Australian, 1919) speak of Logue’s success and Duchan (Citation2012) suggests he was engaged in this work in Australia for around eight years before moving to Britain. It is possible that other Australians were similarly employed, as was the case in Britain (Eldridge, Citation1968).

Australian and British SLP history is to some extent intertwined (Eldridge, Citation1968; Duchan, Citation2012) with a few early British practitioners immigrating to Australia and some Australians spending time or developing their careers in Britain (McDougall, Citation2009a; Duchan, Citation2012). Articles published in the journal Speech, and its successors and correspondence held in the RCSLT archive (e.g. Abotomey, Citation1947) show that from the 1930s, the Australian and Britain and SLP professions grew in parallel and had close links. The history of the profession in the two countries is sparse, however, with much deriving from personal memoirs, such as those of Maloney (Citation2000), Porteous (Citation2003) and Buttifant (Citation2019) in Australia, and Byers Brown (Citation1971) Wilkins (Citation1992), Hewerdine (Citation2014) and Mitchell (Citation2020) in Britain.

In 2002, SPA commissioned an oral historian to interview speech-language pathologists involved with SPA. Themes from eight interviews were reported the following year (Wills, Citation2003) and quotes from these and other interviews were presented in poster form by McDougall (Citation2009b, Citation2009c). Oral histories continued to be collected until 2007 (McDougall, Citation2020): it appears that the later interviews were transcribed, but unanalysed, being archived for future use. The first, and to date only, oral history of speech and language therapy in Britain was published recently (Stansfield, Citation2020).

Oral history has become a well-established approach to collect qualitative life-story information (Thompson & Bornat, Citation2017) and notable large-scale studies have used the methodology in Australia in the Australian Generations Oral History Project (e.g. Holmes, Thomson, Darian-Smith, & Edmonds, Citation2016) and in Britain in the Millennium Memory Bank (e.g. Gallwey, Citation2013). Oral history began as a way of enabling voices of undervalued individuals to be heard and to contest the neutrality and objectivity claimed by traditional written histories, which frequently privilege the rich and powerful (Abrams, Citation2016). More recently it has been used to capture memories of individuals from a range of professions, for example physiotherapy (Richardson, Leighton, Russell, & Caladine, Citation2015) and occupational therapy (Dunne, Pettigrew, & Robinson, Citation2018), whose experiences and perceptions would otherwise have been lost.

A number of challenges do arise within the oral history methodological approach. First, every person has a number of different “selves” and participants and interviewers will each present a particular “self” depending upon the situation, their expectations of the interview process and the non-verbal as well as verbal presentation of the communication partners. Second, memory is central to oral history. Memory is an active process which changes over time and it is likely that high-impact events in a person’s life (episodic memory) will be remembered more vividly, although skilful questioning, pacing and listening can elicit a range of memories (Abrams, Citation2016; Yow, Citation2015). Memory is, by definition, subjective, but the strength of oral history is in that very subjectivity: the ways in which the participant constructs their personal interpretation of the past (Thompson & Bornat, Citation2017). Third, narrative style will shape the way in which memories are reported. A narrative will also emphasise different elements depending upon the interlocutors, and the way in which a story is told will contribute to its interpretation and the construction of the oral history. Finally, each conversation is a performance, either conscious or unconscious, constructed in a style that works in a conversational or interview situation (Abrams, Citation2016). Overall, though, oral history can provide a rich in-depth opportunity to enable the voices of narrators to be heard through collaboration between them and a researcher in a conversational format (Yow, Citation2015).

The raw data which offers the most robust opportunity to construct any oral history is the audio (or less often video) recording (Thompson & Bornat, Citation2017). However, sound is transient, and, therefore, textual transcription is more frequently the material which is subject to analysis (Bornat, Citation2020).

While long-term links between Australian and British SLP have been identified, to date no attempt has been made to compare the experiences reported by speech-language pathologists in the two countries, or to identify possible influences on these experiences. This study uses transcripts from Australian and British oral histories. It aims to explore commonalities and differences in the experiences reported by speech-language pathologists who began to practise in these two politically related, but geographically very distant and distinct countries, in the first three decades after the Second World War. It also aims to enable current speech-language pathologists to identify the legacy of early practitioners, to recognise the close relationship between the two country’s SLP professions and to identify the ways in which professional identity forms and changes over time.

Method

Participants

Two sets of oral history transcripts are taken as primary sources. The Australian data set comprises eight previously unanalysed transcripts collected between 2002 and 2007, released to the author by the copyright holder, SPA. Australian interviewees had been selected “for their enduring and significant contributions to the profession” (Wills, Citation2003, p. 44) and had qualified between 1945 and the early 1970s. The British data set consists of a subset of 16 transcripts of interviews carried out by Stansfield (Citation2020), who is a dual qualified SLP and historian. Participants were British speech-language pathologist who had qualified between 1946 and 1968. Recruitment took place between 2017 and 2019, with the support of RCSLT.

Procedure

Australian interviews were audio-recorded, and transcribed by McDougall, another dual qualified speech-language pathologist and historian (McDougall, Citation2020). The British interviews were audio recordings, then transcribed commercially, edited by the author using the original audio-recordings and member-checked by participants for accuracy (Stansfield, Citation2020). These audio recordings and transcripts are held as part of the RCSLT archive in the Special Collections, University of Strathclyde. All participants in each cohort had given permission for the transcripts to be archived and analysed for research purposes.

Each set of interviews followed a life-span approach, using similar topic guides asking about career choice, education and training, first and subsequent posts and careers (Wills, Citation2003; Stansfield, Citation2020). Interviews for the British data set were time-stamped and lasted between 40 min and 2 h (mean 56 min). Although not time-stamped, judging from the length of the Australian transcripts, those interviews would have taken a similar amount of time.

While the material was collected at different time points and the Australian cohort was reporting on events closer to the dates of data collection, transcripts relate to approximately the same time period for each cohort, this being 1945–2008.

Analysis

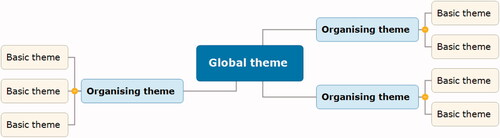

Thematic network analysis (TNA, Attride-Stirling, Citation2001) was used to systematically code and develop themes inductively from the Australian interview transcripts and to re-analyse the British transcripts. This approach is similar to the better-known thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke (Citation2013). Stages build from initial coding of the raw text, identifying basic themes from the codes, which are then grouped together to summarise more abstract concepts (organising themes) and subsequently enabling global themes or constructs to be created from the data. The approach offers a transparent order of stages and replicability of the analysis process and in addition, allows for an accessible visual representation of the themes identified, with themes presented as a web or network which illustrates the relationship between the basic, organising and global themes (see and ).

Table 1. Steps in analyses employing thematic networks: summary (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001 p. 391).

The analysis was carried out manually (rather than using a software package). To assure rigour, two colleagues, one a historian and one a speech-language pathologist, had access to the data sets. At each stage of analysis, they reviewed and commented upon coding and identification of themes. Where there were initial differences in interpretation these were resolved and agreed through discussion. The resulting thematic networks are presented below.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the use of both data sets was granted by the author’s University ethics committee (approval number 16/1345/EthOS 12525), with consent from SPA (Australian data) and the University of Strathclyde (British data). All materials were treated in accordance with the consent given by each participant.

For the purposes of this article, all participants were assigned a pseudonym, either of their own choosing, or allocated by the author, with a further initial: A to indicate Australian (e.g. AlexA) or B for British (e.g. AmandaB). In addition, a small amount of material was further anonymised, while maintaining the essence of the narrative. Account was taken of specific ethical issues in using archived oral history material, in particular, recognition of topics which are socially or historically sensitive (Puri, Citation2015; Bornat, Citation2020).

Result and discussion

Data from a total of eight Australian and sixteen British participants were analysed.

Dates of birth for the Australian participants ranged from 1922 to 1954. For the British group the range was 1926–1947. Qualification dates were also more spread for the Australian cohort and it was notable that some had qualified after an earlier career in a different profession. Brief pseudonymised demographic details for each cohort are listed in and pseudonyms appear in .

Table II. Demographic details.

Table III. Oral history participants (all pseudonyms).

This article reports two global themes: "personal stories” and “professional stories” mirroring two similar global themes identified in Stansfield’s (Citation2020) British study.

Global theme: personal stories

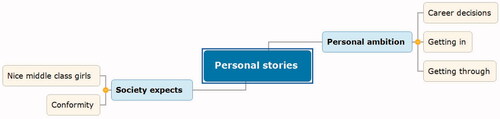

The first global theme demonstrates how participants’ social milieux and personal ambitions were negotiated, as seen in the thematic network, .

Society expects

Nice middle-class girls

The majority of participants were white middle-class women. Indeed across the two cohorts, there were only two men. AnnaA reported that men could not be recruited to her Australian college because there were no male toilets “that’s true, that’s not a joke: there were no male toilets therefore there could be no male students”. JayB speaking of her British college cohort in 1949 indicated the rarity of male students by saying: “we were famous, we had two men”. Only two participants, both from Australia, self-identified their ethnicity, these being JanA, who said:

My parents… were Jewish and they got out of Germany before the War… and my father joined the Army here. He wasn’t allowed to serve overseas, being an alien.

while PatA reported that in the 1950s, as “an aboriginal … I wasn’t even supposed to be human then”. Apart from JanA and PatA, all others from both groups left their own ethnicity silent, although from the transcripts, membership of the majority culture was implicit.

Class was more frequently acknowledged. SallyB’s (British) cousin had “escorted Churchill round the world”, something that would only be possible for a young woman from an upper-middle or upper-class background. LeahA, said that her mother (although not herself): “came from the [Australian] landed gentry”. In addition, mention of fathers’ working lives indicated middle-class professional affiliations with education and medicine, for example: “My parents… were medical missionaries” (AlexA); “my father knew the local top of the education service” (JillB); “my mother was a Medical Officer of Health” (MillicentB). Only two participants claimed working-class origins. SamA’s father was a skilled blue-collar worker. SamA also reported “my mother was essentially unemployed all her life. I didn’t get into academic life through examples from my parents”. AltheaB was, according to her, from working-class Liverpool (although, in acknowledging that her accent did not reflect this, she said of a colleague “she thought I was posh, and I was a working class girl”). At some point, the need for the “correct” accent was commented upon by all of the British and most of the Australian participants. For example MillicentB reported “They tried to iron out everybody's Scottish accent”, while AndyA, said “I went to London to do speech therapy, so I became [adopts ‘posh’ accent] terribly received pronunciation”, another class marker, as noted also by Duchan (Citation2012).

Conformity

For each of the participants, ambitions for a career were constrained by social expectations of their gender, ethnicity and class. The two men were expected to provide a living for their families (although each had atypical ways of doing this). The Aboriginal participant was restricted as to where work was available, despite qualifications in teaching and SLP. Social expectations did change between the 1940s and 1970s, but all of the women in both cohorts, while encouraged to study for a career, “nursing, teaching or clerical work, there wasn’t much else” (LeeA), were also expected to conform to the social mores of the day, including marriage and children. Indeed, from one of the earliest qualified British participants “I was busy being married” (JayB) to one of the later qualified Australians “I just wanted to be a good wife” (LeahA) this was part of the early assumed direction of their lives.

The majority of the British participants indicated that they did conform. After studying, most married and followed their husband’s jobs if they moved around the country, stopping work when they had children: “in those days, you left when you became pregnant.” (AbigailB). At one point, RuthB was told explicitly by a male medic that “People [meaning women] with children shouldn't work anyway, you know”. Women gradually returned to work only if they could organise child care and domestic roles. “I was fortunate from the point of view I could do a couple of days a week or two and a half days a week or something like that.” (KathyB). Even RuthB and JanetB, who reversed bread-winner roles, did so only temporarily, in order to support husbands who were studying.

The Australian participants typically appeared to be less conformist than their British sisters and possibly rather less constrained by rigid social class rules. AnnaA “thought I might go on radio or I might be an air hostess”. SamA spent some time attempting to carve out an acting career,

but it didn’t pay very well and I wasn’t that good; so I aborted that and did a number of odd jobs … [until one day] my phone rang … and it was [name], and she was enjoying herself at a conference and all her friends were laughing and chatting and I was stuck in an office ordering cement-lined plumbing pipes. And I thought, ‘Mm.’

AndyA, who had been brought up in England and trained as a speech therapist there, summarised why she found Australian lack of conformity more to her liking as “the robustness of the place and the sort of laid-back, don’t-get-your-knickers-in-a-knot attitude, that has really suited me”.

Personal ambition

Career decisions

As SLP was little known when the participants were making career choices, the personal aspirations of participants were often reported to be rather more broadly focussed. KathyB said, “The high flyers were expected to go to university and do law or medicine. If you weren't in that league, and I don't think I was, it was expected you'd become a teacher” not something that appealed to her. Several of the British cohort reported having no clear idea of direction. JillB, for example, said “I was absolutely hopeless leaving school. Couldn't decide what to do”. SelmaB was more sure about what she did not want to do. Her father “heard that [name] was doing speech therapy. And I didn't want to follow Dad into medicine … [so] he said, ‘Well, how about that?’”. Others were caught in an “age trap”, leaving school before they were old enough to go to college. As a result, some were cajoled into “useful” courses. UrsulaB’s mother “enrolled me in a domestic science college for a year, thinking that wouldn't do any harm”, while CarolB joined a secretarial school “I was quite popular as a student because I took all my lecture notes in shorthand and so if anybody had missed anything, they knew that I would probably have much fuller notes than anybody else”. For some, accepting parental and school advice on careers was with a certain amount of reluctance. MegB, for example saw herself as a Shakespearean actress, but was persuaded by her father that this was not a secure occupation. Despite this, she said: “speech therapy… the college in [city] was linked to the drama school and I thought there might be some way of transferring or soaking up something”, while AbigailB “had always wanted to be a nurse” before eventually joining the SLP course.

Most of the Australian participants had expected to study at university. JanA, for example, with a flair for languages, had considered becoming an interpreter. PatA “was doing an arts program, at that stage I was doing geography”, AnnaA thought of psychology and AlexA enrolled to study microbiology, but experienced significant sexism from both students and lecturers and decided to change direction. Eventually, however, all of the participants “discovered” SLP. For some it was through personal contacts “I met her at a party and said ‘what do you do’ and she told me and I thought ‘she’s a nice girl and it sounds like a good idea’” (AlexA), while others, such as JanA went for some vocational guidance, and despite being told “speech therapy, it wouldn’t be difficult for you but you may want to do something more challenging. How about being a librarian?” decided SLP was for her.

Getting in

Schools of SLP in both countries started small. They were usually private concerns and it was only gradually that they became integrated into colleges, polytechnics and eventually Universities. The first degrees were established in Britain (University of Newcastle) in 1964 and Australia (University of Queensland) in 1967 (Robertson et al.,Citation1995; McAllister, Citation2020).

Getting into an SLP course offered different challenges and it is likely that social class was a factor in being accepted. CarolB, in Britain said: “The interview was very strange… I had the entry qualifications, and really, after they knew that, they wanted to look at my mouth to see about my dentition and they also wanted to know what my father did”. AbigailB, reported: “I went for an interview and in those days, you went very nicely attired, wearing a hat, with my mother and a very close aunt in tow and of course, we got the inevitable IQ test and the personal interview and the good going over by [name]”. However, speaking of the same college, one of the earliest qualified participants JayB, said “my mother went and interviewed [the Head of Department] ”, while UrsulaB, “was admitted, or accepted, for the following year without any interview, without being seen. I was taken in only because the lady in question, [name] knew my father. That wouldn't happen today”. In Australia, LeeA was also given an IQ test “and then they said the following day could I come to Mrs [name]’s house for afternoon tea”, being unaware this trial-by-teacups was part of the selection process. SamA, was told that SLP “was a really elite group of professionals and there were only twelve people admitted” but gung-ho, deciding to apply for higher education, “stuck down medicine, vet science, law, aeronautical engineering, astrophysics, I also put speech therapy down there, and I got accepted for the lot and I chose speech therapy”.

Getting through

“Getting through” college brought other issues to the fore. The formality was unexpected for many participants, who reported feeling constrained by excessive rules and regulations, often much stricter than their schools had imposed. While a few people lived at home with parents, the majority of young women were away from home for the first time, so possibly this was in order to protect them, but it certainly rankled for many “suddenly I was thrust into a ‘Miss Jean Brodie’ set up. It was incredible. Quite unbelievable. We had to wear blazers with the colours round it and the proper scarf” (JanetB).

College experiences were similar in Australia and Britain. Participants spoke of sharing lectures with other professional student groups, usually designed for those groups, rather than the SLP students. Sometimes this was appreciated “we went to a neurology clinic in the Royal every Friday afternoon… one of these great galleried things, with all the medical students there. And we had lectures in neurological conditions. From this very charismatic lecturer called [name], and it was like it was a theatrical performance” (MegB), but at other times the work seemed incongruous: “we had to pith these Queensland cane toads to prepare sciatic gastrocnemius muscle fibre” (LeeA), and sometimes not only the students but also the lecturers were at sea: “It was pretty hairy the first year, because a lot of the lecturers didn't know quite what we were supposed to be taught. Like we had a lecturer in maths, and we couldn't do any of the maths” (AltheaB). Both cohorts reported moving around various venues for classes. LeeA reported a great deal of walking “from one hospital to another and to the University”, while according to MillicentB “[classes] were all in different parts of [city]. So we had phonetics at the University… and then we went [over a mile] to the Sick Children's Hospital for anatomy and physiology”. JayB summarised by saying “we had a very kind of peripatetic life”.

In the earliest days, London students even moved between two different schools of SLP for different aspects of their course:

Normal speech and voice which we went to the Central School to do because they obviously specialised in it there. So twice a week we went to them and they came to us for the anatomy and things like that. The medical things, they came to us, their students who were doing speech therapy (SallyB).

This latter statement came as something of a surprise, as it was not much earlier that the London colleges, their staff and graduates were said by Robertson et al. to be “at daggers drawn” (1995, p.10).

In both countries, where students were studying core subjects (speech pathology, phonetics, physics of sound, normal voice and speech and much later, linguistics) these tended to be in small spaces, often part of the lecturers’ homes or private rooms rented for the purpose. A common complaint from participants was that they did not have a real student experience. In part this was a result of the intensity of the course “we were into it from morning till night. Nine o’clock lectures, six o’clock lectures sometimes” (LeeA);

it was very full-on. Never a minute to spare. In fact, I remember going to classes of an evening, and I lived maybe 30 miles away from [city], and we went to anatomy classes in [name] University, and I had to travel home at 8:00 at night and got home until 10:00 at night in the middle of winter, and in bad weather and so on. That was quite daunting. And not only that, we had classes on a Saturday morning. (KathyB)

But there was also a sense of being “other”, not quite a part of the student cohorts they met “it was difficult to join interest groups. We were visitors to campus. So we felt like visitors and we didn’t join in the social activities much” (AndyA); “We didn't have any corporate life. We didn't belong anywhere” (JayB).

Even clinical placements were frequently long distances from students’ residences. In Britain, especially for those students outside London, it sometimes seemed that they had been allocated to ensure the maximum level of discomfort. SelmaB, for example was sent a good 60 miles from the south side of her city to a rural placement in the west: “So, it meant getting up in the morning at some unearthly hour when you were scraping frost off the bus windows on the inside”. Comparable experiences were reported by the Australian participants, with PatA saying of a bus journey to one placement “which I hated. It took me just about an hour and a half to get there”. Sometimes the bus could be preferable. AbigailB recalled one clinical educator:

Because I lived on her route to hospital, she would give me a lift. Her car was something else. You perched on the seat and looked down through the floorboards and saw the road – and she drove like a maniac.

The majority of placements, however, were reported to be positive experiences, with participants enjoying the clinical work. The impression from the transcripts is that the Australian cohort had more clinical hours overall, and more experience with a range of adult-acquired impairments, although all had to comply with the input hours required by the respective professional bodies before being allowed to sit their final examinations.

At the time these participants were studying, examination papers and practical assessments were set by professional bodies, the predecessor organisations of SPA or RCSLT, and to a large extent, these were very similar, having been originally established by British trained speech therapists. “Finals” were five three-hour papers over two and a half days, something which would cause a riot with today’s students. In addition to written examinations, practical exams had to be performed “in front of two or three people, which I felt sorry for the patients, actually” (LeeA), and the eminence of some of the examiners was enough to cause major anxiety for students. JayB, for example said: “I was examined by, would you believe Muriel Morley and Catherine Renfrew [two of the best known names in Britain at the time]. Well, of course, Muriel Morley was treated to a cleft palate child, naturally enough, whose case history was outlined, totally word for word, verbatim, from her own book”. Adding “And I passed! ”, as, of course did all the other participants.

Summary

There were many similarities between the British and Australian groups when reporting their personal stories. British participants appeared to be more accepting of constraints than their Australian counterparts, but, class and gender (and, overtly in Australia, ethnicity) mediated expectations, ambitions and opportunities available to each individual.

Global theme: professional stories

This second global theme illustrates how participants’ professional identities and careers developed once they had qualified. presents the thematic network.

Professional identity

Expanding understanding

Participants’ professional identities began to be formed throughout their college years, but rapidly expanded once they had qualified. Many were launched into their careers with little or no support, frequently saying they suddenly realised how little they knew, or what to do. A few were confident “the feeling then was that you knew everything” (JanA), but most were not. Of the Australians, AlexA, for example said “I’d never had a case longer than twelve weeks. And I wasn’t sure that I would altogether know what to do after twelve weeks” while SamA reported of frequently being “bewildered”, not least when, having had a single stuttering placement at college and gaining a first post, being told “Oh, you know about stuttering? Well, you can be the stuttering specialist”. British therapists had similar experiences. JessB said of her first post “I was entirely on my own. Had no mentor. I was simply told to get on with it”.

Challenges did not just encompass client groups, but also the logistics of reaching clinics. SallyB’s first post was in rural Kent, with very limited public transport in the late 1940s:

I would catch a bus into Canterbury, to catch another bus out of Canterbury to go to Folkstone or to go to the Margate area. And, another day I took a bus to Whitstable to get a train to Sittingbourne

SelmaB, single-handed in north-west Scotland “had to work out things like boat timetables, ferry timetables, and I'd go to some places… everything from Campbelltown to Ardnamurchan and the islands of Mull, Coll, Tiree, Islay, Jura, Collansea, Gigha”. Distance was even more of an issue for the Australian participants. While most took up posts in the major Australian cities, service to rural areas was much more challenging, and for many years extremely sparse. SamA pointed out that “in Australia thirty per cent of people live rurally” while AlexA said “there would be very very few people from the country… who would have received any speech therapy services”. Sporadically, services were offered through speech-language pathologists travelling in for a week of consultations to places such as “Atherton and Millaa Millaa”; “Lameroo and Pinnaroo”; “Whyalla and Ceduna”. On such occasions LeeA, for example spoke of being “indundated, absolutely inundated… they were desperate”. Unfortunately, even when posts were created to work in country areas, “they didn’t want to leave the town. So it was it was difficult to get people to go to the country” (LeeA) or to retain staff.

Eventually, participants from both groups reported increasing confidence in their clinical work, and spoke with enthusiasm about the clients with whom they worked. The earliest qualified spoke mostly of “speech” disorders. Articulation, stuttering and cleft palate in children were mentioned, along with trauma, stroke, stuttering (again) and voice disorders in adults. In retrospect and later, participants recognised characteristics of language impairment, both in children and adults and embraced the opportunity to work with these. There was, however, initial resistance to dysphagia, which only began to be part of SLP work towards the end of the 1980s. At the time: “I’d no more teach them about swallowing than teach them about hopscotch. It seemed to be so, ‘It’s not about communication’”. (SamA). For each new area, it took time for theoretical approaches to be accessible and as a result, for many years participants continued to be “bewildered” (SamA) but “did the best I could” (RuthB) in the absence of a great deal of theoretical support.

Seeing the gaps

It was not just the lack of theory that was noted by participants, but also the mismatch between the needs of patients and the services on offer. All of the Australian participants commented on the medical model of service delivery. AndyA said “if a consultant was walking down the corridor you flattened yourself against the wall”, while LeahA reflected, “we didn’t have this understanding of family-centred practice… it was very medical model, expert model, ‘I’m the expert, I do the assessment, you do what I tell you to do’”. Participants from both countries, however, rapidly found that that the medical model was neither sufficient, nor for many patients, necessary. In Britain, the social impact of poverty came as a huge culture shock to some, “Part of my work was in a very, very, very poor area of Birmingham with a lot of slum housing and I think those three years I grew up (JessB), while AbigailB was challenged by other social factors: “I think the final warning came when I parked outside some houses… and a woman was hanging out of her window and she said, ‘Will you get out there the noo, hen, because he's hame’ [gloss, please leave at once, because my husband, a violent man, has returned home] and I realised that perhaps I was being a bit silly and going into people's houses not really knowing what I might find”.

Gender could be an issue. In Australia one of the men found “mothers had a high degree of anxiety about leaving children alone with a strange man… [so taking a prudent approach] I wouldn’t see a child unless a parent was there”. In Britain AltheaB spoke of a colleague treating a well-known private patient who:

was desperate for women in his family, because he had several wives and mothers and sisters walking round, and he was sat there on his own. And he grabbed her and he offered her a big sheaf of money. And she had to run out of the room, and she ran into the sister's office, and the sister said, "Oh not you as well."

The confluence of race and disability also impacted. AlexA spoke of a prisoner, an “Aboriginal man from [area] who’d had meningitis as a child. He came in through the audiology clinic. Now there’s no way that man should have been in jail, he had no sign language, there’s no way he could have understood the court process”. In both countries, many other stories reflected similar concerns and the need to go beyond the medical model as new fields developed.

Memorable mentors

All the participants spoke of people who had helped to establish their professional identity and had influenced their careers. There were some who created friction and distress and a determination not to be like them. Possibly these had invested so much energy into their work that they were unable to recognise others’ needs, or possibly enjoyed their pre-eminence in a small female professional pool at the expense of others? UrsulaB, for example, speaking of one eminent British academic said “she … dominated everybody… we were all terrified”. MegB, speaking of another similar character told the story of being put well in her place:

she said, "Suppose you were appointed to post in Persia. How would you set about organizing a speech therapy service?" And my jaw dropped and I said, "I don't know anything about it. I don't speak Persian." She looked at me witheringly and said, "I said Perthshire”

In Australia AlexA, SamA and JanA were influenced by an eminent psychologist and researcher in stuttering. All acknowledged that he could be uncompromising and this did not always make him popular with the SLP profession, but “he’s one of the stand-out people” (AlexA); “his leadership in those days led many treatment revolutions around the world… they were controversial because they were behavioural treatments’ (SamA); “he was an innovator; he was an experimenter; he was a researcher; he was a man with a lot of integrity” (JanA).

Few mentors were seen as being perfect human beings, but their influence, leadership and in many cases charisma were celebrated. Some well-known names were reported to have had a major impact on the lives of the participants, with “a superb clinician”; “you watched her doing therapy and it was inspiring”; “a very learned lady and an excellent lecturer” or simply “inspirational” being frequently seen in the transcripts. Beyond well-known names, the influence of individuals who worked closely with participants was also acknowledged, with mention of challenging but fair bosses, supportive colleagues, and motivating clinicians who stimulated new thinking and the courage to try new approaches in the participants’ practice. In addition, several of the participants in each cohort of this study were themselves cited as being memorable, inspirational mentors.

No learning ever lost

From practice to theory

As participants gained confidence in their own clinical skills and began to question received wisdom, many began to look for further experience and in particular further qualifications in order to develop their understanding. Here there was some difference evident between the Australian and British cohorts, partly it appeared as a result of cultural differences, partly geography and possibly partly a result of the original inclusion criteria for the two groups. All the participants reported taking opportunities for continuing professional development when the opportunities arose, although the availability was limited, especially for local study in many areas. Most of the Australian participants took the chance to travel to broaden their personal and professional horizons “it was quite often done for people to go overseas, for young women and men to go overseas, get out of Australia” (JanA) and several found themselves in Britain. LeeA, for example “went to London and did the Reynell courses”. JanA, in England along with a friend, visited Moor House School, a specialist centre for communication disordered children and both were offered jobs there. AnnaA “only worked with London County Council as far as speech therapy went” but from there was interviewed in Canada House and got a post in Canada as a speech-language pathologist.

A few British participants also travelled abroad. SusanB moved around the world following her husband’s diplomatic career and working in “an ad-hoc manner” (SusanB) as a speech-language pathologist in Trinidad, teaching in Kenya and lecturing in Iran. JillB and RuthB took temporary opportunities for travel and new learning in Canada and the US, but the majority of British participants did not leave the shores of the country for work purposes. Probably the most adventurous was JanetB. Her story of (safely) travelling to the Peto Centre in Hungary is just one example:

two men arrived, and I'm not joking, they had fedora hats on, collar up on their coat, and don't forget, this was Eastern Europe and the '60s, and I think one of them even had dark glasses on… and I'm thinking, "You're absolutely mad, sitting in the back of this car with two strange men who look straight out of a spy movie, and you're believing them."

More traditionally, participants from both groups sought university qualifications, although again there were differences between the Australian and British participants. The Australians were more likely to pursue higher degrees abroad especially in the USA. Possibly this was because the availability of advanced SLP courses was limited in Australia and much more available in the USA, at least in the early years (although two subsequently completed doctorates in Australia); possibly because funding was available for educational travel; possibly because travel abroad was, in any case, more acceptable for young middle class Australians, than their British counterparts at the time. No British participant studied formally outside Britain and most had a struggle to be accepted onto Masters courses with only their College of Speech Therapists Diplomas. RuthB, for example was rejected by her chosen University “they were still being snooty about speech therapy qualifications” but found a course willing to accept and encourage her, which led to a career as a researcher. AltheaB, CarolB, JessB and SusanB all took advantage of an MSc course explicitly established to encourage speech-language pathologists to study, although even so, it raised some eyebrows, as CarolB reported: I remember telling [a medical colleague] that I was going off to Guy's Hospital to do a Masters and he said, "But you're a speech therapist. How on earth did you get on a course like that?". JillB, on the other hand, applied what, judging from the rest of the interview, was probably force of personality to get accepted to study for her PhD, saying: “I decided to take a PhD and I was allowed to, without any entry requirements other than the Diploma”.

Unexpected directions

Many participants from each group found that at times their professional lives took unexpected turns. Sometimes this was a result of adverse personal situations, sometimes serendipity. JayB was bereaved relatively early in her marriage:

Yes a bit of a shock. And I was left with my part-time job and I had to do something about it, they found me some more sessions… [then a new management post was created] So I thought, well, I'll go for it, and it's either that or go out to Australia and make a new life. Anyway, I got the job.

JanetB had been enjoying a post in a specialist centre for cerebral palsy “great centre. Great team. Wonderful team to work with” when she was also bereaved. She found the social efforts of well-meaning colleagues difficult. “I know they were trying to be supportive, but… so I applied for a job in the Bulletin, for Tasmania… as the sole therapist for a language unit” and this was the start of a peripatetic career across three continents. Interestingly, in each of these cases, the close relationship between Britain and Australia came to the fore, with Australia being seen as an opportunity for freedom.

Others found a career change in unexpected ways. PatA moved out of SLP on successfully gaining a senior post as Dean of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders studies at [university]. AmandaB was “head hunted by the Bishop to be a hospital chaplain… I was ordained in the June. And things had moved on in the Church of England by then, so instead of just being ordained as a deacon, I could be a priest’. AltheaB (working-class Liverpool girl) became the Chair of a body representing over thirty SLP related charities, organising major events in London, “the Queen Mother came, she brought all her corgis, and they were all running all over the place” (AltheaB).

Higher degrees were the stimulus for several participants from each cohort to change the direction of their career. AlexA had enrolled on an SLP PhD, only to find when she arrived at the university in the US that the speech department had been closed. She was lucky, however to transfer to Psychology, “and that has opened up a whole new domain [in paediatric cognitive neuro-psychology] in my life, that has been extra-ordinary”. For those who were already teachers or lecturers, success at masters or doctoral level developed a stronger sense of self-assurance in initiating change in their practice. AnnaA, rather to her surprise, contributed to a highly influential book on clinical education. SamA became increasingly confident in the research field, designing rigorous experiments which challenged and ultimately changed the profession’s view of efficacy and evidence-based practice saying quietly: “today I know a great deal about very little” (SamA), while LeahA went on to develop novel approaches to rural clinical practice and both she and SamA led national and international developments in tele-medicine long before these became essential in the eighteen-plus months of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Summary

As participants’ professional lives progressed there was, unsurprisingly, more variation both between and within the groups. All recognised the need to expand their knowledge as new client groups were identified and all engaged in a range of continuing professional development, drawing on new evidence as it became available, in order to enhance their practice. With age, experience and relaxation of social conventions over time, more career opportunities became available and participants reported having greater confidence in taking advantage of these opportunities as they arose. Individual life events influenced the direction each career took sometimes to the surprise of the participants concerned,

Limitations

The two oral history sets were collected at different time periods and for somewhat different purposes and so direct comparisons must be viewed with caution. While the author had access to the original British audio recordings as well as transcripts, this was not possible for the Australian data, which may have influenced interpretation of this data set. As in Will’s (2003) work, the voices of men and of minority ethnic groups are largely conspicuous by their absence.

Conclusion

This article draws on the transcripts from twenty four speech-language pathologists who qualified in the first three decades after World War two. SLP was seen as a suitable career by parents and school staff but at least in the early days seemed to embody the limitations implicit within participants’ social milieux. Participants from each cohort described college days in detail, with other life changing events coming to the fore across their careers. After the initial shock of having to manage a range of client groups and the logistics of clinical work, they began to see the limits of their initial training, both in terms of the speech conditions they met, but also underlying assumptions about health care hierarchies and social position. They all reported ways in which they negotiated the personal and professional challenges and the degree to which these were successful or not. The profession’s and the individuals’ scopes of practice expanded over the period of participants’ careers. Some participants continued as clinical speech-language pathologists throughout their working lives, some became academics or researchers, some moved into complementary fields of work, but all appeared comfortable with the trajectory and eventual outcomes of their working lives. AlexA’s statement that “no learning is ever lost” was clear in the directions that the various participants’ careers took, within and outwith SLP.

It is probably that the nature of SLP practice had the effect of influencing the narratives from these participants, which transcended geographical contexts. The motivations that led to becoming speech-language pathologists and the professional experiences reported during and after training suggest a group of articulate, curious individuals who recognised that the needs of their patients and students could be met not just by direct face to face good practice, but also by being willing to take risks in order to expand their knowledge and skills. The ways in which the two cohorts did this varied, influenced by social and cultural as well as geographical differences between the two countries, but the many similarities in attitudes suggest that the professions in Britain and Australia had a great deal in common at the times they were discussing, which appears to continue to the present day (Armstrong et al., Citation2017; SPA, Citation2019).

The voices of these participants come through compellingly in the transcripts, giving a rich picture of SLP in Australia and Britain in the second half of the twentieth century. This article does not assert a positive linear improvement across the decades, although the increased knowledge base and level of service availability mean that more people with communication and swallowing disorders in each country now have access to SLP. The changes reported by participants from both Australian and British speech-language pathologists draws attention to the heritage of the profession and how professional identity is formed, and modified over a life time.

Future directions

There is a great deal more transcript material which is still to be investigated. A further examination of participants’ contributions to the profession’s increased knowledge base and service availability could be drawn from these transcripts. Participants’ professional body activity and the relationship between changing social policy, professional politics and personal aspirations also remain to be explored.

The data sets used in this research were existing oral history transcripts from early members. It would be of value to collect further oral histories form current practitioners and especially from minority groups within the profession, which can be used to trace the ways in which professionals experience and view their lives and careers.

Acknowledgements

Prof Lindy McAllister, Nicole Pantalleresco and Alison McDougall, facilitated access to the Australian transcripts. Dr Linda Armstrong and Dr Laura Kelly contributed to the analysis and provided helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. The two anonymous reviewers offered valuable critiques. All are thanked.

Declaration of interest

The author reports no declaration of interest.

References

- Abotomey, O. (1947). Correspondence with college of speech therapists. London: RCSLT Private Archive, Uncatalogued Membership Files, Abotomey.

- Abrams, L. (2016). Oral history (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Armstrong, L., & Stansfield, J. (1996). A content analysis of the professional journal of the British Society of Speech Therapists I: The first 10 years. Spotlight on ‘Speech’’, 1935–1945. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 31, 91–105. doi:10.3109/13682829609042214

- Armstrong, L., Stansfield, J., & Bloch, S. (2017). Content analysis of the professional journal of the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, III: 1966–2015-into the 21st century. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 52, 681–688. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12313

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). ‘Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research’. Qualitative Research, 1, 385–405. doi:10.1177/146879410100100307

- Bellman, L., Boase, S., Rogers, S., & Stutchfield, B. (2018). Nursing through the years: Care and compassion at the Royal London Hospital. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword History.

- Bornat, J. (2020). Looking back, looking forward: Working with archived oral history interviews. In K. Hughes & A. Tarrant (Eds.), Qualitative secondary analysis (pp.137–153). London: Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

- Brown, B.B. (1971). Speak for yourself, Reading. Educational Explorers.

- Buttifant, M. (2019). 70th anniversary video. Melbourne: SPA. [accessed 3.12.2020]. Retrieved from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/whats_on/70th_Anniversary/SPAweb/What_s_On/70th_Anniversary/70th_Anniversary.aspx?hkey=6e5d02b2-32f6-46b1-a55f-f6e017fac261

- Cooter, R., & Pickstone, J. (Eds.) (2003). Companion to medicine in the twentieth century. London: Routledge.

- Duchan, J. (2005). History of speech-language pathology. [accessed 17.10.20]. Retrieved from http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/∼duchan/new_history/overview.html

- Duchan, J. (2012). Historical and cultural influences on establishing professional legitimacy: A case example from Lionel Logue. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 387–396. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2012/11-0122)

- Dumb speak: successful cures in Perth. The Western Australian, Fri 4th July 1919, p. 8. [accessed 11.1.21]. Retrieved from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/2737079

- Dunne, B., Pettigrew, J., & Robinson, K. (2018). ‘An oral history of occupational therapy education in the Republic of Ireland’. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81, 717–726. doi:10.1177/0308022618770135

- Eldridge, M. (1965). A history of the Australian college of speech therapists. Melbourne, Australia: SPA.

- Eldridge, M. (1968). A history of the treatment of speech disorders. Edinburgh, Scotland: E. & S. Livingstone Ltd.

- Gallwey, A. (2013). The rewards of using archived oral histories in research: The case of the millennium memory bank. Oral History, 41, 37–50.

- Hewerdine, E. (2014). Memoirs of a peash ferapis. New York, NY: Vanguard Press.

- Holmes, K., Thomson, A., Darian-Smith, K., & Edmonds, P. (2016). ‘Oral History and Australian Generations’. Australian Historical Studies, 47, 1–7. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/ accessed 3.12.20. doi:10.1080/1031461X.2016.1119778

- Logue, M., & Conradi, P. (2010). The King’s speech. London: Quercus.

- Logue, M., & Conradi, P. (2018). The King’s war. London: Quercus.

- Maloney, D. (2000). From student to clinical educator – A historical or hysterical perspective. ACQ, 2, 21–22.

- McDougall, A. (2009a). Speech pathology and its professional association in Australia. The development. Poster Melbourne, Australia: SPA.

- McDougall, A. (2009b). Speech pathology and its professional association in Australia. In their own words (I). Poster. Melbourne: SPA.

- McDougall, A. (2009c). Speech pathology and its professional association in Australia. In their own words (II). Poster. Melbourne, Australia: SPA.

- McDougall, A. (2020). Personal communication, April 24th, 2020.

- McAllister, L. (2020). Personal communication, October 9th 2020.

- Mitchell, P. (2020). A career to remember: A personal account of my life as a speech and language therapist. Self-published Google.

- Porteous, R. (2003). Nature, nurture, knowledge and experience in the life of our profession. Keynote paper, Speech Pathology Australia National Conference Hobart, Tasmania, May 8, 2003. Retrieved from http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/∼duchan/history_subpages/ruth_porteous.html accessed 28.11.2020

- Puri, A. (2015). Oral History Ethics: The Australian Generations Project. INSITE magazine Nov 2014-Jan 2015, 4-5 [accessed 25.2.2021]. Retrieved from https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1678741/ma-vic-insite-article1.pdf

- Richardson, B., Leighton, A., Russell, S., & Caladine, L. (2015). An oral history of development of the physiotherapy profession in the United Kingdom. Physiotherapy, 101, e1282. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.1195

- Robertson, S., Kersner, M., & Davis, S. (1995). A history of the College 1945–1995. London: RCSLT.

- Rockey, D. (1980). Speech disorder in nineteenth century Britain. London: Croom Helm.

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2009). Speech pathology Australia celebrates 60 years. Poster. Melbourne, Australia: SPA.

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2019). Speech pathology Australia celebrating 70 years of service and advocacy. Poster. Melbourne, Australia: SPA.

- Stansfield, J., & Armstrong, L. (2016). Content analysis of the professional journal of the College of Speech Therapists II: Coming of age and growing maturity, 1946–65. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 51, 478–486. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12220

- Stansfield, J. (2020). Giving voice: An oral history of speech and language therapy. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 55, 320–331. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12520

- Thompson, P., & Bornat, J. (2017). The voice of the past. Oral history (4th ed.). Oxford: OUP.

- Wilkins, J. (1992). A child’s eye view. Bishop Aukland, England: Pentland Press.

- Wills, J. (2003). Voices from the past: Speech pathology and oral history. AQC, 5, 44–46.

- Yow, V. (2015). Recording oral history (3rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.