Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to explore the Sustainable Development Goal of reduced inequalities (SDG 10) in relation to the experiences of people with communication disability with lived experiences and their access to self-determined healthcare. As such, the article also informs the goal of good health and well-being (SDG 3).

Method

In preparing this article the authors reviewed recent literature on digital health records and digital autonomy as a means to improving equity of access and explored the experiences of two of the authors as people with severe communication disability who use a wide range of digital health technologies in pursuing safe and quality health care. The literature and their experiences highlight a need for improved co-design and usage across disability and health service systems management if e-health records are to be used to reduce inequalities in accessing healthcare.

Result

Recent research and the lived experiences of the first two authors reflect that e-health information systems, designed to improve the consumer’s ability to access and share their own health information, are not used to full advantage in disability and healthcare environments.

Conclusion

Increased access to multimodal communication strategies and communication technologies, along with user-centred co-design that enables digital health autonomy will further progress towards reduced inequalities (SDG 10) and good health and well-being (SDG 3) and for people with communication or swallowing disability.

Background

The primary focus of this paper is on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal reduced inequalities (SDG 10). SDG 10 includes empowering and promoting “social, economic and political inclusion of all” and ensuring equality opportunity “and reduce inequalities of outcomes, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard” (United Nations, Citation2015, np). The paper also relates to healthcare experiences and access, and as such could also inform progress towards good health and well-being (SDG 3). The first two authors of this paper have communication disability and use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) to communicate. As these authors live in Australia, our focus is the My Health Record (MyHR), an ostensibly personally controlled e-health system designed for all Australians (Makeham, Citation2019) for the storage and sharing of particular types of e-health documentation (see Hanna, Gill, Newstead, Hawkins, & Osborne, Citation2017; Van Kasteren, Maeder, Williams, & Damarell, Citation2017) including prescriptions and dispensed medications, test results, event summaries (detailing a particular moment in care), hospital discharge summaries, and an advance care plan. This plan is the only document that can be uploaded by the healthcare consumer, outlining their wishes for future medical care (McCarthy, Meredith, Bryant, & Hemsley, Citation2017).

Personal e-health records could be used to improve health information exchange for people with communication disability, who often struggle to communicate their health information to multiple health providers, impacting on autonomy and self-determination (Hemsley, Rollo, Georgiou, Balandin, & Hill, Citation2018). It is critical that their communication rights are realised in accordance with Article 21 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD) that “persons with disabilities can exercise the right to freedom of expression and opinion, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas on an equal basis with others and through all forms of communication of their choice” UN General Assembly (Citation2007). This group face several barriers to inclusion in e-health initiatives through e-health records requiring high levels of health literacy (Hemsley et al., Citation2018), combined with a lack of opportunity to use these systems, and barriers to computer literacy and digital health literacy (Walsh et al., Citation2021). People with communication disability often have associated physical limitations and reduced physical access to computers and the internet, further contributing to the digital divide (Van Kasteren et al., Citation2017). They may rely on others for support to access computers and the internet and hence their access to digital health technologies (Hemsley et al., Citation2018). However, staff who provide support for people with disability are also at a disadvantage in terms of their digital health literacy, and often speak languages other than English, the dominant language of most e-health applications (Walsh et al., Citation2021).

People with communication disability need support to access and retain their human right of digital autonomy. Digital autonomy is an emergent concept that relates to the user of the technology being able to read, manipulate, and access their digital information and have control over their digital devices, privacy settings, and the information that is shared (Blanc & Sandler, Citation2020). Digital autonomy exists within a digital ecosystem and builds upon the principle of autonomy (Kouser & Ward, Citation2021) as an extension of bodily autonomy; in that rights do not end with the physical body but continue online (Blanc & Sandler, Citation2020). Examples of digital autonomy relevant to health include people using the internet to look up health conditions prior to attending a medical appointment (see Asch et al., Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2017), setting user access and privacy controls within an e-health record, or uploading or requesting removal of information from their e-health records (McCarthy et al., Citation2017). The lived experiences of the first two authors as people with severe communication disability who use AAC are now used to highlight several barriers to achieving equity in healthcare that should be considered in furthering SDG10 particularly in relation to healthcare equity for people with disability.

Stories of experience in digital health autonomy

Fiona’s story

Being actively involved in healthcare decisions from an early age became easier for me when, at the age of 10, I was provided with a communication device and health professionals became more inclined to engage with me directly. These days I use a wide variety of digital health technologies, increasingly during the COVID-19 lockdown and reduced access to in-person services. These include (a) preparing notes to doctors to give them at appointments to save time and help with note-taking, (b) using email to make appointments and exchange health information (e.g. scan results) with my specialists, (c) making health appointments in mobile phone apps, and (d) using SMS for confirmation and reminders and receive results. Using SMS or email removes the need for me to answer the phone and is more empowering than relying on my support worker to speak on my behalf.

Partly due to having a physical disability, I find it difficult to keep track of the large amount of health-related paper records at home. However, my support workers often do not know where information is kept or how to access the same documents from their employer whom I have authorised to share my information online in their secure systems. The support workers seldom make the effort to check the online information kept by my disability service, or else have trouble reading English, and so I am constantly repeating the same information directly.

MyHR has so much potential, especially for people in my situation, yet it is not widely used even by health professionals. Although the Australian Government (Citation2022) reports 23.3 million Australians and 99% of general practitioners (GPs) are registered to use the MyHR with 98% of GPs having used it, none of my doctors are actively using it with me. The only documents that have been uploaded to it are a health summary by my general practice nurse, some pathology results, and a record of my last two COVID-19 vaccinations. I tried to access a radiology report but as that section of MyHR was empty I had to ask the GP to email the report to me so I could email it to my physiotherapist.

Acknowledging that it is important and beneficial for health professionals to ask and hear my story directly (Komesaroff & Kerridge, Citation2018), I tire of having to repeatedly draw upon my own recollection to explain my health history, particularly when I am unwell or in a time-pressured situation. For example, I recently had to change dentists without any notice and all my records were with the old practices. My new dentist remarked “you have had a lot of dental work done in the chair” and my mother said “she had her wisdom teeth done under general anaesthetic”. I asked for my device and said “more than just that, I have had other work done under general anaesthetic”. Memory aside, it takes effort for me to communicate my complete medical and dental history so it would be nice if it was accurately stored in one place other than in my head (Makeham, Citation2019). So overall, I would say that my experiences in striving to manage my multiple forms of health information are affected by a lack of cohesion among my team of support workers and healthcare providers, and lack of a systematic health information infrastructure across disability and health services (Dahm, Georgiou, Bryant, & Hemsley, Citation2019).

Meredith’s story

Like Fiona, I am self-determined and long capable of using multiple systems and strategies for managing my health information. As well as using my speech device and mobile speech apps on my iPad, I use Health Engine, DocBook, HotDoc and email to book appointments, prefer SMS for appointment confirmations and reminders, and write notes to hand over. And yet, in getting older, I am becoming no less frustrated that service providers are not recognising my information as valid or not using the available digital health systems in time. My recent experience shows just how much self-advocacy I use trying to overcome barriers to sharing my healthcare history and needs both at home and in hospital.

In April 2016, I woke up in agony, and from past experience I knew I had a kidney stone. Living in a retirement complex, I pressed the buzzer beside my bed, and explained with my iPad speech app that I needed an ambulance. The woman answering my call thought I had a fall – I explained I had a kidney stone. The ambulance came, and on the way to the hospital I gave the paramedic my ambulance membership number and other details. She said “your apartment complex is lovely”. I nodded. I thought to myself, yes, I worked hard for 30 years and had to sell a house to get it. I told her I used MyHR thinking this would help with details. She seemed disinterested and said she had opted out of using it. We arrived at Emergency and the paramedic mentioned the MyHR to the triage administration officer, who replied: “We don’t have that”. As the ambulance officer was leaving she said “Meredith lives in a care facility”. I was in too much pain and too angry to correct her at that moment. My anger returned a few days later (and still does) when after discharge home I logged into MyHR to see my discharge report – despite the admin person saying “we don’t have that” – and the discharge summary incorrectly noting that I lived in a care facility. Incorrect assumptions are on my Record forever, and are presumably on my hospital record too. I had to return to the same hospital recently, and as I was being discharged to go home, they kept referring to the “nurse” that was picking me up, when it was actually a ride-share I had organised.

I cannot always rely on the digital health systems being used or having the correct information updated or healthcare providers believing my own report of health information. In 2021, I emailed my admission documents to the hospital after phoning the technology help section twice; as the internal software program for uploads was not working. When I was admitted two hours later they had attached my old admission documents. The nurses phoned the dietitian to check on my tube feeds, and the dietitian looked up the old records and said “three feeds a day”, without checking with the rehab affiliate who had increased it to four feeds a day – information I had included in my admission documents. I had to argue with the nurses from then on for the fourth feed, and I had two nurses tell me I was only to have three feeds a day. When I told them I was dangerously underweight and needed the fourth feed, they thought I wanted to be weighed. I was weighed, at 34.48 kg, which showed I was dangerously underweight – but still the nurses did not give me a fourth feed. I had lost the argument. I doubt if they would have believed me even if I had told them “look up my electronic health record”. Once home, I used email to send a letter of complaint.

Conclusion

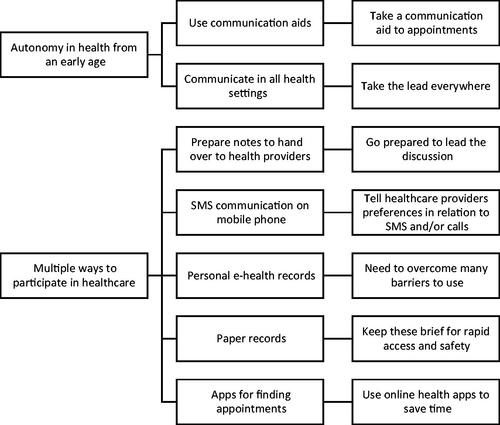

Fiona’s and Meredith’s stories reflect the importance of self-determination and the use of multiple e-health technologies and communication strategies in striving for digital health autonomy, concepts reflected in , a framework of strategies to increase health equity of people with communication disability. People with communication disability face several barriers in accessing personal e-health records related to their communication difficulties and lack of user-centred co-design of these systems. Both authors’ stories of experience reflect their need to monitor the accuracy of stored health information, their frustration borne of a lack of cohesion across disability and health service providers, and interruptions in the exchange of health information impacting on their healthcare experiences across settings.

Figure 1. Strategies to increase equity of access to health information and digital health autonomy for people with communication disability.

Digital health records have the potential to reduce inequality in healthcare service provision, particularly for people in rural and remote areas (Almond, Cummings, & Turner, Citation2017), and for people with communication disability (Hemsley et al., Citation2018), potentially furthering the SDG 10 to reduce inequalities in health across countries. However, such records will not be sufficient and will still rely on the human users of the systems (Komesaroff & Kerridge, Citation2018) to upload and share information. As digital health autonomy is an emerging field (Kouser & Ward, Citation2021), there is much scope for people with communication disability to be included in co-design of digital health technologies that help to meet SDG 10. Once made accessible to people with communication disability and supportive of digital autonomy, digital health systems could be used to increase choice and control and potentially improve equity of access to health services. Further collaborative research with people with communication disability is needed to reduce inequalities to autonomous access to e-health records throughout the world (Hemsley & Debono, Citation2021). The stories of experience presented in this paper highlight several barriers and facilitators in the use of personal information and e-health records discussed in relation to evidence from the literature. There is a need to build better digital health information infrastructure that furthers the sustainable development goal of reduced inequalities (Walsh et al., Citation2021). If SDG 10 is to be realised, future inclusive and user-centred co-design will be needed to develop, implement, and evaluate the impact of any e-health record system to increase safe and quality health care equity (Hemsley & Debono, Citation2021).

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Almond, H., Cummings, E., & Turner, P. (2017). An approach for enhancing adoption, use and utility of shared digital health records in rural Australian communities. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 235, 378–382. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-753-5-378

- Asch, J.M., Asch, D.A., Klinger, E.V., Marks, J., Sadek, N., & Merchant, R.M. (2019). Google search histories of patients presenting to an emergency department: An observational study. BMJ Open, 9, e024791. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024791

- Australian Government. (2022). My health record statistics and insights, February 2022. Australian Government, Digital Health Agency. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/mhr-statistics-february-2022.pdf

- Blanc, M., & Sandler, K. (2020). The declaration of digital autonomy, licensed under creative commons attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International. https://techautonomy.org/

- Dahm, M.R., Georgiou, A., Bryant, L., & Hemsley, B. (2019). Information infrastructure and quality person-centred support in supported accommodation: An integrative review. Patient Education and Counseling, 102, 1413–1426. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.03.008

- Hanna, L., Gill, S.D., Newstead, L., Hawkins, M., & Osborne, R.H. (2017). Patient perspectives on a personally controlled electronic health record used in regional Australia. Health Information Management Journal, 46, 42–48. doi:10.1177/1833358316661063

- Hemsley, B., & Debono, D. (2021). Recognising complexity: Foregrounding vulnerable and diverse populations for inclusive health information management research. Health Information Management Journal, 2021, 183335832110527. doi:10.1177/18333583211052708

- Hemsley, B., Rollo, M., Georgiou, A., Balandin, S., & Hill, S. (2018). The health literacy demands of electronic personal health records (e-PHRs): An integrative review to inform future inclusive research. Patient Education and Counseling, 101, 2–511. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2017.07.010

- Komesaroff, P., & Kerridge, I. (2018). The My Health Record debate: Ethical and cultural issues. Internal Medicine Journal, 48, 1291–1293. doi:10.1111/imj.14097

- Kouser, T., & Ward, J. (2021). Health-related digital autonomy: An important, but unfinished step. The American Journal of Bioethics, 21, 31–33. doi:10.1080/15265161.2021.1926591

- Makeham, M. (2019). Connecting Australians to their My Health Record. Health Information Management Journal, 48, 113–115. doi:10.1177/1833358319841511

- McCarthy, S., Meredith, J., Bryant, L., & Hemsley, B. (2017). Legal and ethical issues surrounding advance care directives in Australia: Implications for the Advance Care planning document in the Australian My Health Record. Journal of Law and Medicine, 25, 136–149.

- Smith, R.J., Crutchley, P., Schwartz, H.A., Ungar, L., Shofer, F., Padrez, K.A., & Merchant, R.M. (2017). Variations in Facebook posting patterns across validated patient health conditions: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, e7. doi:10.2196/jmir.6486

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals: 17 Goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals

- UN General Assembly. (2007). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 24 January 2007, A/RES/61/106, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/45f973632.html [accessed 12 July 2022].

- Van Kasteren, Y., Maeder, A., Williams, P.A., & Damarell, R. (2017). Consumer perspectives on My Health Record: A review. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 239, 146–152.

- Walsh, L., Hemsley, B., Allan, M., Dahm, M.R., Balandin, S., Georgiou, A., … Hill, S. (2021). Assessing the information quality and usability of My Health Record within a health literacy framework: What’s changed since 2016? Health Information Management Journal, 50, 13–25. doi:10.1177/1833358319864734