Abstract

Purpose

To examine the need, feasibility and acceptability of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) implementing a systematic, routine, unmet social needs identification and referral pathway, as a means of promoting health equity and addressing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Method

Quality Improvement methodologies were used to adapt and pilot an unmet social needs identification and referral pathway for use with parents/carers of children with communication disabilities referred to an urban Australian speech-language pathology service. SLPs were surveyed about the acceptability and feasibility of this practice.

Result

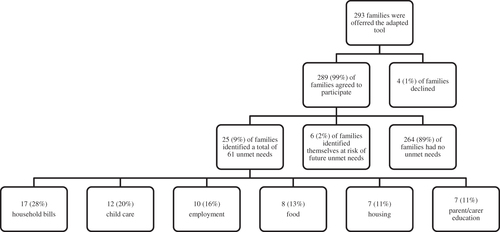

The majority of parents/carers, 289 of 293 (99%), agreed to participate in the study, with 31 of the 289 (11%) reporting concerns about unmet social needs. The most common unmet need related to household bills (n = 17, 28%), followed by childcare (n = 12, 20%), employment (n = 10, 16%), food (n = 8, 13%), housing (n = 7, 11%), and parent/carer education (n = 7, 11%). The majority of these families, 26 of 31 (84%), requested referral to, or information about, local community services/resources. SLPs reported high levels of acceptability (93%) and feasibility (98%).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the need, feasibility and acceptability of SLPs implementing an unmet social needs identification and referral pathway, and the potential to scale this initiative across other speech-language pathology services and allied health contexts. This paper focusses on SDG 1, SDG 2, SDG 3, SDG 4, SDG 8, SDG 10, SDG 11, SDG 16, and also addresses SDG 17.

Introduction

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a global call to action to ensure a better and more sustainable future for everyone, as many citizens of the world are living with unmet social needs and are denied a life of dignity (United Nations, Citation2015). Adopting an overarching framework to address unmet social needs holds promise for promoting child health (Gurewich et al., Citation2020), achieving health equity (Woolfenden et al., Citation2018), and addressing many SDGs (United Nations, Citation2015). Allied health professionals, such as speech-language pathologists (SLPs), are key to this strategy as they often see children and families early and over long periods of time (Dougall & Buck, Citation2021; Royal College of Speech Language Therapists, Citation2021). However, addressing unmet social needs, in partnership with parents/carers of children with communication disabilities, is not a practice routinely and systematically implemented by SLPs. This pilot study aimed to address this gap, and in the process, pursued nine of the critical SDGs by focussing on, no poverty (SDG 1), zero hunger (SDG 2), good health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), reduced inequalities (SDG 10), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16), and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17).

In Australia, one in six children live below the poverty line (Davidson et al., Citation2020). Poverty does not solely refer to a lack of money, but also encompasses access to affordable housing, food, education and health services (World Health Organization, Citation2014). These are the social determinants of health (SDH) – the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Citation2008). The SDH drive child health inequities – differential outcomes that are unjust, unnecessary, systematic and preventable (Marmot et al., Citation2008). Child health inequities affect every part of a young person’s health, education and well-being and these effects last into adulthood (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Citation2008). There is a growing body of evidence that SDH identification and referral pathways for unmet social needs can effectively address SDH concerns (Andermann, Citation2016; Garg et al., Citation2015) and potentially lead to improvements in health, development and well-being, cost, and health equity (Gurewich et al., Citation2020). However, to date such pathways have not been used by SLPs with Australian paediatric populations.

The aim of this study was to promote health equity and address nine SDGs through examining the need, feasibility and acceptability of a systematic, routine, unmet social needs identification and referral pathway in an urban Australian paediatric speech-language pathology community outpatient service.

Ethical approval

Quality Improvement ethical approval (QIE 2021-04-06) was obtained through Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network.

Method

Quality Improvement methodologies (Batalden & Davidoff, Citation2007) were used to adapt the Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education (WE CARE) SDH screening tool (Garg et al., Citation2015) to create an identification and referral pathway. This pathway was then piloted with parents/carers of children referred to the paediatric community outpatient speech-language pathology service at Sydney Children’s Hospital (SCH), Randwick, over a 12-month period. Parents/carers were offered the pathway as part of routine telephone intake practice. Parents/carers who reported an unmet need were offered onward referral to appropriate support services. An anonymous survey, completed by SCH SLPs, gathered information about the acceptability and feasibility of this practice.

Participants

The study sample included parents/carers of children (0–16 years) referred to SCHs’ paediatric community outpatient speech-language pathology service (n = 317 children from 293 families) and SCH SLPs working at SCH (n = 14, 74%) between 1 March 2021, and 28 February 2022. As this was a feasibility study, it was not powered to detect changes in outcome measures, rather primary outcomes related to feasibility and acceptability.

Procedure

The pathway

A series of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) (Reed, Davey, & Woodcock, Citation2016) cycles were used to guide the development of the unmet social needs identification and referral pathway to suit the local SCH context. Rapid cycles were undertaken to select the screening tool for adaption, develop the pathway, conduct the pilot, assess clinician acceptability and feasibility, and ensure sustainability. The WE CARE screening tool (Garg et al., Citation2015) was selected as the tool to adapt due to the SDH domains assessed (i.e., education, employment, child care, housing, food, utilities), paediatric focus, length, readability, and ease of interpretation. The WE CARE tool was developed in the United States. It was adapted to reflect the local context, language/terminology and support services available from the onward referral partner. The local community partner for onward referrals was Family Connect and Support (New South Wales Government, Citation2021) as they provided support for all SDH domains included in the adapted tool, welcomed referrals from professionals and parents/carers, and had geographical inclusion criteria that matched SCH’s speech-language pathology service. Script modifications, and changes to the order and phrasing of questions, occurred throughout the pilot as part of the PDSA cycles. The adapted WE CARE tool (Supplemental Appendix), addressed six needs: child care, parent/carer education, employment, housing, food security, and household bills. SCH SLPs used the pathway as part of routine telephone intake. Parents/carers were asked whether they wanted to participate in the study. The final pathway took less than five minutes to administer.

SLP survey

To determine whether SLPs found the unmet social needs identification and referral pathway to be acceptable and feasible, the Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM) and Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM) (Proctor et al., Citation2011), were administered. The AIM and the FIM are validated and reliable measures of implementation outcomes based on key implementation outcomes of acceptability and feasibility that can be used with a wide range of key stakeholders. They can be adapted for the population, context and intervention (Weiner et al., Citation2017). The 8-item anonymous online survey () was distributed through the Quality Audit Reporting System (QARS) to all paediatric SLPs (n = 19) employed by SCH.

Table I. SLP acceptability and feasibility survey and responses.

Data collection

The pathway

Identification and referral data was captured and saved on a password protected department drive. Information audited included: number of families asked to participate in the screening; number of families agreeing to participate in the screening; number of children each family were referring to the service; number and type of reported unmet needs for each family; number of onward referrals made to Family Connect and Support; number of requests for onward referral information in lieu of referral; and number of families declining onward referrals or information.

SLP survey

No specialised training was required for the AIM or FIM administration and interpretation. Each measure had five response options, ranging from completely disagree to completely agree. Higher scores indicated greater acceptability and feasibility. Scales can be created for each measure by averaging responses. No items needed to be reverse coded. Data collation and reporting is a feature of QARS.

Ethical considerations

Screening children and families for any condition without having an appropriate treatment or referral pathway raises ethical questions (Perrin, Citation1998). For this pilot, all families were offered a referral to Family Connect and Support if unmet social needs were identified. Clinicians were supported to identify and refer families through training and the development of a script to standardise the pathway.

Results

SDH identification and referral pathway

The majority of parents/carers, 289 of 293 (99%), agreed to participate in the pathway (). Overall, 264 of the 289 (91%) of families had no current unmet needs. However, 25 of the 289 (9%) of families had between 1 and 5 unmet social needs out of a possible 6 areas of need, with a total of 61 unmet needs collectively for this group (i.e., 1 unmet need = 9 families, 2–3 unmet needs = 8 families, >3 unmet needs = 8 families). The most common unmet need related to household bills (n = 17, 28%), followed by childcare (n = 12, 20%), employment (n = 10, 16%), food (n = 8, 13%), housing (n = 7, 11%), and parent/carer education (n = 7, 11%). A further group of parents/carers (n = 6, 2%) reported no current unmet needs but indicated being at risk of upcoming financial hardship/job loss and requested onward referral information.

Eighty-four percent (n = 26) of families who reported concerns about unmet social needs, requested onward referral (n = 13, 50%) or information (n = 13, 50%) to community services/resources to address the identified unmet needs. Families who did not seek onward referral or information (n = 5, 16%) were already accessing family support programs or services (n = 4, 13%) or were not concerned (n = 1, 3%).

SLP survey

Overall, the SCH SLPs survey results () indicated high levels of acceptability (93%) and feasibility (98%). Regarding acceptability, all SLPs welcomed the pathway, with the majority (92.9%) indicating it appealed to them and that they liked it (85.6%). In relation to feasibility, all SLPs agreed that SDH screening was implementable, with the majority (92.8%) also indicating that SDH screening seems easy to use.

Discussion

The aim of SDGs is to end poverty and inequalities and make sure no one is left behind. This study, the first of its kind in Australia and the first known study by SLPs globally to address unmet social needs, contributes to making nine of the SDGs a reality. The aim was to examine the need, feasibility and acceptability of a systematic, routine, unmet social needs identification and referral pathway in an urban Australian paediatric speech-language pathology community outpatient service. Results indicated that it was possible for SLPs to promote nine of the SDGs by incorporating an unmet social needs identification and referral pathway into routine clinical intake practice.

Current evidence

This pilot study demonstrates lower rates of unmet social needs identification (9%), yet higher rates of onwards referrals (84%), compared to recent studies that report rates of 20-68% and 43-70% respectively (Berger-Jenkins et al., Citation2019; Fiori et al., Citation2020; Garg et al., Citation2015). Many factors could have contributed towards these outcomes, including the location, population, method and timing of this pilot.

Limitations

Limitations include: (a) the relatively small sample size; (b) evaluation of the attitudes and perceptions of a small sample of SLPs from the setting where the pilot took place, (c) a lack of psychometric evidence for the adapted tool, and for SDH screening tools in general (Henrikson et al., Citation2019), and (d) a lack of outcome data measuring the benefits these referrals had on families’ unmet needs. Furthermore, this pilot only focussed on one moment in time. We acknowledge the need for sustained solutions in addressing childhood disadvantage and recognise that measuring disadvantage as unidimensional, at a single point in time, is likely to understate the true extent and persistence of disadvantage and is only one small step in promoting equity through action on the SDH (Goldfeld et al., Citation2018).

Implications for future research

Further development of the adapted tool with parent/carer input, followed by trials with larger sample sizes across different geographic and socioeconomic locations, and outcome data, would provide valuable evidence in defining the role of SLPs, and allied health professionals, in this field. Psychometric assessment of the adapted tools used to identify SDH concerns is also essential.

Implications for practice

SLPs and allied health professionals have the opportunity to address health inequities and SDGs as part of child and family centred care by developing practice guidelines that will ensure that questions about unmet social needs are asked sensitively and there are clear identification and referral pathways to support and assist families’ needs (Andermann, Citation2016). Future guidelines must examine the feasibility and acceptability of such a practice change given health workers report a number of barriers in screening for the SDH including lack of time, lack of training, lack of understanding of available screening tools and community resources, and feelings of being overwhelmed by addressing such daunting social problems (Andermann, Citation2016). Furthermore, guidelines should be developed in consultation with the onward referral partner to ensure the pathway is appropriate, feasible and sustainable.

Summary and conclusion

This pilot study demonstrated the need, feasibility and acceptability of SLPs implementing an unmet social needs identification and referral pathway, and the potential to scale this initiative across other SLP services and allied health contexts. Health professionals working in every level of health care play an important part in tackling health inequalities through addressing SDGs. This innovative initiative provided a way for SLPs to embrace and integrate the SDH into routine clinical practice to achieve “a better and more sustainable future for all” (United Nations, Citation2015).

SCH_adapted_WE_CARE_screening_tool_April_2022.docx

Download MS Word (69.7 KB)Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andermann, A. (2016). Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188, E474–E483. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160177

- Batalden, P.B., & Davidoff, F. (2007). What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? BMJ Quality & Safety, 16, 2–3. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

- Berger-Jenkins, E., Monk, C., Dʼonfro, K., Sultana, M., Brandt, L., Ankam, J., … Meyer, D. (2019). Screening for both child behavior and social determinants of health in pediatric primary care. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 40, 415–424. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000676

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Final report of the commission on social determinants of health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1

- Davidson, P., Bradbury, B., Wong, M., & Hill, T. (2020). Poverty in Australia 2020-part one: Overview. The Australian Council of Social Services, The University of New South Wales. http://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Poverty-in-Australia-2020_Part-1_Overview.pdf

- Dougall, D., & Buck, D. (2021). My role in tackling health inequalities: A framework for allied health professionals. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/tackling-health-inequalities-framework-allied-health-professionals

- Fiori, K.P., Rehm, C.D., Sanderson, D., Braganza, S., Parsons, A., Chodon, T., … Rinke, M.L. (2020). Integrating social needs screening and community health workers in primary care: The community linkage to care program. Clinical Pediatrics, 59, 547–556. doi:10.1177/2F0009922820908589

- Garg, A., Toy, S., Tripodis, Y., Silverstein, M., & Freeman, E. (2015). Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: A cluster RCT. Pediatrics, 135, e296–e304. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2888

- Goldfeld, S., O’Connor, M., O’Connor, E., Chong, S., Badland, H., Woolfenden, S., … Mensah, F. (2018). More than a snapshot in time: Pathways of disadvantage over childhood. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47, 1307–1316. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy086

- Gurewich, D., Garg, A., & Kressin, N.R. (2020). Addressing social determinants of health within healthcare delivery systems: A framework to ground and inform health outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35, 1571–1575. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05720-6

- Henrikson, N.B., Blasi, P.R., Dorsey, C.N., Mettert, K.D., Nguyen, M.B., Walsh-Bailey, C., … Lewis, C.C. (2019). Psychometric and pragmatic properties of social risk screening tools: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57, S13–S24. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.012

- Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T.A., & Taylor, S. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372, 1661–1669. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6

- New South Wales Government. 2021. Family connect and support. https://www.familyconnectsupport.dcj.nsw.gov.au/

- Perrin, E.C. (1998). Ethical questions about screening. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 19, 350–352. doi:10.1097/00004703-199810000-00006

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., … Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 65–76. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Reed, J.E., Davey, N., & Woodcock, T. (2016). The foundations of quality improvement science. Future Hospital Journal, 3, 199–202. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.3-3-199

- Royal College of Speech Language Therapists. (2021). Addressing health inequalities: The role of speech and language therapy. https://www.rcslt.org/health-inequalities

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Weiner, B.J., Lewis, C.C., Stanick, C., Powell, B.J., Dorsey, C.N., Clary, A.S., … Halko, H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12, 1–12. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3

- Woolfenden, S., Asher, I., Bauert, P., De Lore, D., Elliott, E., Hart, B., … Goldfeld, S. (2018). Summary of position statement on inequities in child health. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 54, 832–833. doi:10.1111/jpc.14134

- World Health Organization. (2014). World development report 2015: Mind, society, and behavior. The World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0342-0