Abstract

Purpose

Current speech-language pathology (SLP) services in Cambodia are limited in scope, service accessibility and integration into government systems. However, momentum is growing to develop an internationally recognised profession. This paper examines the depth and breadth of SLP support available to people with communication and/or swallowing difficulties in relation the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Method and Result

Qualitative interview data collected from service facilities (n = 13) and speech therapy practitioners (n = 27) were mapped and analysed for accessibility and scope of SLP services. Data revealed a workforce density of 0.16:100 000. Disparity in service accessibility was identified between provincial and urban locations, adult and paediatric populations and range of practice areas.

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings demonstrate the importance of partnerships (SDG 17) among government departments, non-government organisations and private sector entities to establish a sustainable and culturally responsive SLP profession in Cambodia. Although there is no Cambodian university training program, there is a growing momentum and local commitment to establishing a workforce to support Cambodians with communication and/or swallowing difficulties. This commentary paper focuses on good health and well-being (SDG 3), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), reduced inequalities (SDG 10), and also addresses no poverty (SDG 1), quality education (SDG 4) and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17).

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 interrelated global goals designed to achieve a more sustainable future for the world’s population by 2030 (United Nations, Citation2015b). Cambodia has recorded significant achievements in meeting target indicators in responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), and notable improvement in no poverty (SDG 1) and clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) (Sach et al., Citation2021). However, the 2021 SDG index scores comparison shows that Cambodia ranks 102nd out of 165 countries in the overall achievement of SDGs (Sach et al., Citation2021, p. 11), with challenges across the remaining 13 SDGs, and varied progress made on specific indicators within each SDG. Further these national-level measures fail to capture the development impact for specific populations or community needs. This paper reports on the emergence of locally based speech-language pathology (SLP) services in Cambodia and the growing commitment to develop a sustainable Cambodian SLP workforce. This paper examines the depth and breadth of SLP support available to people with communication and/or swallowing difficulties through the lens of the United Nations’ SDGs (United Nations, Citation2015b), particularly good health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8) and reduced inequalities (SDG 10), with reference to no poverty (SDG 1), and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17).

Living with a disability in Cambodia

The Cambodian government is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, Citation2006), and has established laws, policies and plans regarding the inclusion of people with disabilities (e.g. Law on the Protection and the Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2009; 2019–2023 National Disability Strategic Plan, Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2019b). Sector leadership is provided under the authority of government stakeholders in partnership with both national and international non-government organisations (NGOs) providing health, education, disability and rehabilitation services and initiatives (Bryce & Bong, Citation2020).

The 10% of the Cambodian population estimated to have a disability (National Institute of Statistics, Directorate-General for Health, and ICF International, Citation2015) continue to face many barriers. While income levels across the nation have risen resulting in reclassification as a lower middle-income nation in 2015 (Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2019a, p. 10) the average income of Cambodian households with at least one person with a disability is only 34% of the national average (OECD, Citation2017). The impact of disability on a family’s economics is not limited to the lost earning potential of both people with disabilities and their caregivers, but includes extra costs related to disability specific expenditures, such as medication, assistive technology and transportation costs. This increased risk of poverty is amplified for women with disabilities who face increased barriers accessing the workforce (Ministry of Women’s Affairs of Cambodia, Citation2014).

Despite the existence of a legislative framework for disability inclusion, Cambodians with communication or swallowing difficulties have not benefitted from Cambodia’s efforts towards achieving the SDGs due to a lack of awareness, services and workforce. Unlike physical disability, communication and swallowing difficulties are rarely highlighted in Cambodian government forums, documents, policies or national statistics. In addition to the aforementioned institutional barriers, Cambodians with communication disabilities also face attitudinal barriers, which have significant impact on their ability to attend school, work, form relationships, and participate in everyday, social and cultural routines such as going to the market or attending community weddings (OIC Cambodia, Citation2019).

Cultural understandings of disability also influence community attitudes and limit everyday identification and access to services for many people with disabilities, in particular communication disability. The majority of Cambodian people are Buddhist and believe in Karma: that is doing good results in receiving good and doing bad results in receiving bad. Cambodians with disabilities often report discrimination due to the common belief of a disability being the result of a person’s negative actions (OIC Cambodia, Citation2019). The abilities of people with disabilities are rarely acknowledged and not publicly recognised. The invisibility of communication disability is also embedded in Khmer language use.

The Khmer word for disabled  “Pi- ka” is commonly understood to refer to physical disability. Intellectual disability is known as

“Pi- ka” is commonly understood to refer to physical disability. Intellectual disability is known as  “Vib-blash”, a Khmer word also used for psychological and psychiatric disorders. However, there is no commonly understood word for communication disabilities which remain the hidden issue in communities. Further, Cambodian people living with swallowing difficulties are not included in Cambodian research or publicly available reports.

“Vib-blash”, a Khmer word also used for psychological and psychiatric disorders. However, there is no commonly understood word for communication disabilities which remain the hidden issue in communities. Further, Cambodian people living with swallowing difficulties are not included in Cambodian research or publicly available reports.

While progress is being made in relation to quality education (SDG 4) (Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2019a), access to education remains limited for many children with a disability. One in two Cambodians with disabilities aged between 15 and 29 years have had no formal schooling (compared to 9.4% of non-disabled peers). Amongst primary-school-aged children, 57% of those with disabilities are out of school (compared to 7% of non-disabled classmates) (UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS) and Global Education Monitoring Report (GEMR), Citation2017).

Equity and the development of a “world in which the needs of the most vulnerable are met” is central to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, Citation2015a, p. 4). This is reflected in both Cambodia’s national social protection policy framework 2016–2025 (Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2017) and the Cambodian SDG framework (Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2018) represented through the slogan “leave no one behind”. This aspirational statement implies that development across the Kingdom should benefit all people. However, the lack of progress and positive outcomes in good health and well-being (SDG 3) and quality education (SDG 4) is amplified for Cambodians with communication or swallowing difficulties, due to a lack of accessible services, the invisibility of communication disabilities and limited local workforce.

Access to SLP services in the Cambodian context

The Kingdom of Cambodia is one of the least urbanised countries in South East Asia with approximately three-quarters of the nation’s population of 16 million living in rural areas (GlobalEconomy.com, Citationundated). It is estimated at least 600 000 Cambodians (4% of the population) have communication and/or swallowing difficulties (Salter & Yeoh, Citation2017). Cambodians with communication and swallowing difficulties are an under-served population, facing multiple barriers to access quality and affordable SLP services suitable to specific population’s needs and provided within their community.

Cambodia’s training, employment and regulation of allied health professions and professionals are managed across three government ministries: Ministry of Health; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport; and Ministry of Social Affairs, Veteran and Youth Rehabilitation. Each sector has its own management, service and referral structures and consequently views SLP from their unique perspective. However, the limited recognition or discussion of SLP in policy and services is common across the sectors (Bryce & Bong, Citation2020). For example, while Cambodia’s progress towards meeting good health and well-being targets (SDG 3) have included the establishment of a Health Equity Fund to provide access to free health care to 16.3% of the population who are categorised as poor (Royal Government of Cambodia, Citation2019a), SLP services are not yet recognised or available as essential for any primary health care or rehabilitation system within Cambodia. Challenges of providing universal and comprehensive health coverage are compounded by limited accessibility for those living in rural areas (World Health Organization, Citation2018, p. 10).

The availability and quality of SLP services are also limited by the absence of a local SLP academic program and institutional presence in Cambodia. Recognition of the need for recruitment, development, training and retention of a quality health workforce (Target 3.c) within the Cambodian context is not new. Calls to strengthen the depth and breadth of Cambodia’s health workforce have come from both within and outside Cambodia (Department of Planning and Health Information, Citation2016; World Health Organisation, Citation2019). The current delivery system of SLP services has been described as “challenging and complex” (Salter & Yeoh, Citation2017, p. 104) with a substantial shortage of available and adequately trained SLP workforce to meet the current and growing needs in the country. Current services are significantly limited in scope, service accessibility and integration into government systems (Bryce & Bong, Citation2020). However, services to support people with communication and/or swallowing difficulties are emerging. For example, work-based internship training programmes have occurred in national hospitals and specific NGO services. Momentum, both within and outside the country, to develop an internationally recognised SLP profession is growing.

Method

This paper presents quantitative and qualitative data collected via structured interviews in 2019 with staff from 13 Cambodian-based service facilities that self-identified as providing speech therapy. These were the only services known to provide SLP services within Cambodia. The service facilities included government hospitals/clinics, not-for-profit service facilities, and private clinics in the health, disability services and education sectors. Processes of risk, burden and benefit assessment, confidentiality and informed consent adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2022)

Twenty-seven Cambodian health, education, and disability workers identified by the service facilities as providing aspects of SLP services, were also interviewed. Job titles and practice scope varied greatly among this group as did their method and duration of training (some of whom used the job title “speech therapist” despite not having formal tertiary SLP training and qualifications). This report refers to this group as SLP practitioners. Collectively, these practitioners have pioneered services and raised awareness of aspects of SLP practice within Cambodia. Three of the 13 service facilities had qualified expatriate speech-language pathologists (SLPs) working within their services. These SLPs were not included in the interviews.

The interviews were conducted by staff of OIC Cambodia. Data were analysed to map current speech-language services and workforce with reference to service availability and scope of practice. The results, in the form of summary tables, were sent to all participating service facilities for validation.

Results

Universal health coverage (SDG 3) and the SLP workforce (SDG 8)

Across Cambodia, 27 SLP Cambodian practitioners provided a SLP workforce through 13 service facilities. This workforce of less than 0.16 Cambodian SLP practitioners to 100 000 people demonstrates the extent to which Cambodia’s SLP services and workforce were critically insufficient and fall far short of universal health coverage.

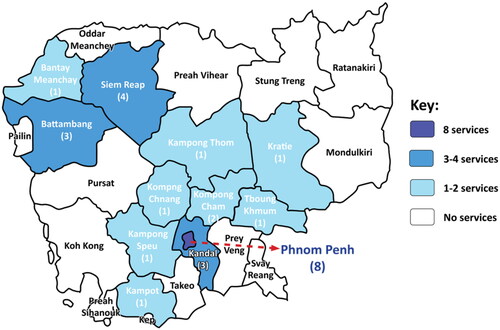

A total of 217 people were reported to access services in the week prior to the interviews: 104 (47.92%) in acute health services; 30 (13.82%) in education; and 83 (38.25%) in disability services. The majority of services were located in Phnom Penh (n = 8, 61.54%). Services outside Phnom Penh include two services within 25 km (15.38%), three provincial services (23.08%) and outreach provided to six additional provinces. Thirteen provinces were without any form of SLP service, while 19 provinces had no locally based SLP services ().

Distribution of services was evenly spread across health (n = 9), education (n = 9) and disability/rehabilitation (n = 10) with the majority of services provided by private facilities and in urban areas (). Accessibility in provincial areas was limited: centre-based services (n = 2) and outreach service (n = 3). The data demonstrate a significant economic and access gap between urban and rural contexts. The majority of services (n = 12) provided support for children with a range of communication or swallowing difficulties (), this included two specialist services for children with cleft lip/palate. Support for adults was limited to swallowing (n = 1) or hearing (n = 2) difficulties. No services were available for adults with communication difficulties or children and adults with acquired brain injury, aphasia or motor speech difficulties.

Table I. SLP services by sector, services delivery, practice focus and geographical location.

Table II. Service availability by target population (impairment type and age).

SLP services were available at the four national level hospitals in Phnom Penh supported by NGOs. Practice areas were limited to adult dysphagia (n = 3), cleft palate (n = 2) and general paediatric (n = 1) services. No services or workforce exist within the sub-national referral and provincial hospitals or health centres.

Supporting quality education (SDG 4)

No SLP services were provided within mainstream government education. However, services were provided through nine private education facilities, including two NGO supported special school classes co-located within government school grounds. Of these, all included pre-school aged children and most (n = 8) primary aged children.

Impact on reducing inequality (SDG 10)

Within disability/rehabilitation services, 10 services identified as providing support to people with communication and swallowing difficulties, with most (n = 9) providing paediatric services only. Of the 10 services, seven were within 25 km of the capital city with one-half (n = 5) offering outreach services. No SLP services were available in any of the government’s 11 provincial physical rehabilitation centres.

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate both a critical need for the development of services to meet the population’s communication and swallowing needs, and the breadth of the emerging SLP profession. Thus, while steady progress has been made in reaching SDGs, Cambodians with communication and/or swallowing difficulties, continue to experience increased rates of poverty (SDG 1), higher levels of inequality (SDG 10), reduced access to education (SDG 4), and reduced health and well-being (SDG 3). Further, these data raise questions about the nature of a contextually and culturally relevant SLP profession for Cambodia.

A strong foundation and local commitment to the development of a Cambodian SLP profession is evident in the range of services for children and adults despite the lack of a recognised profession or locally accessible SLP university training. Local non-government service facilities provide training for health, education and rehabilitation professionals seeking to support their clients’ communication and swallowing needs and in doing so are establishing the role of SLP professionals across the three relevant sectors contributing to future job creation and decent work (SDG 8).

Partnerships within and between government departments, NGOs and the private sector (SDG 17) are essential for establishing a sustainable and culturally responsive SLP profession. Through training and advocacy, partnerships are being established with education, health and rehabilitation ministries. Specialist SLP organisations are working on capacity building projects within the three key ministries. This has resulted in work-based internship training programmes being introduced into national hospitals and the inclusion of individuals and NGOs advocating for SLP services within national disability and education system and policy review. Historical precedent regarding physical disability services in Cambodia (see above) provides a strong foundation for current and future projects focussing on the activity and participation needs of individuals with communication and swallowing difficulties.

Consideration of partnerships between Cambodian and international entities and individuals is also vital. Abrahams et al. (Citation2019) argue that the professionalisation of SLP and Western models of service delivery, reinforced by Western medical models of care and power inequities of coloniality, can lead to increased inequality. Consequently, commitment to the SDGs requires expatriate SLPs and international organisations to commit to culturally responsive partnerships through critical self-reflection on their values, attitudes and beliefs, as well as how these influence their individual and team-based practices (Hopf et al., Citation2021). As a foundation, this requires the foregrounding of Cambodian perspectives and aspirations as any international support seeks to work alongside local initiatives. For example, the exclusion of expatriate SLPs from this study reflected the research team’s focus on understanding the local workforce from a local perspective. Relationships with non-Western SLP organisations within the Cambodian region are being fostered to support cross-fertilisation of ideas and approaches to the development of a relevant SLP profession that support equality in Cambodia.

A common language to talk about SLP in the Cambodian context is required to address the invisibility of communication and swallowing disabilities in Cambodian society and policy. Rather than translating Western SLP terminology and practices into Khmer language and the Cambodian context, Cambodian led research is exploring community language use regarding speech, language and communication disability. Investigation of existing caregiving and care-seeking behaviours and underlying beliefs, is required to address the current barriers experienced by individuals with communication and swallowing difficulties and develop responsive and sustainable services and systems (Wylie et al., Citation2017). A Cambodian led project to explore these issues for communication disability is underway. An early application of this research will be developing contextual information resources, and capacity building of the workforce in primary health care, community rehabilitation and educational outreach services to increase understanding in key areas of childhood communication development, strategies for inclusion and support of people with communication and swallowing difficulties. The authors consider caregiver, primary-health and community-rehabilitation resourcing to be a strong immediate priority, complementing the long-term academic program and establishment of comprehensive SLP services within government and private systems.

Further, research regarding swallowing difficulties in Cambodia is required to support the development of services and a local evidence-base. Concurrently, ensuring access to information and empowering people with communication and swallowing disabilities to be able to self-advocate and engage in decision making about services is needed. A support group for individuals with complex communication needs has been established through a Cambodian NGO. Facilitating forums such as this for peer learning and advocacy will be an important part of SLP’s role in Cambodia to reduce inequality (SDG 10).

Finally, a sustainable, quality SLP workforce requires a Cambodian university education programme. Since the data were collected, the first Cambodian with a university qualification in SLP has graduated and returned to Cambodia. However, while SLP practitioners trained through work-based professional development and short courses are the foundation of the current workforce, increased public and government awareness of SLP is adding to momentum for a university programme and a recognised SLP profession (SDG 8). In addition, the intentional establishment of formal partnerships and integration of capacity building within existing public health, rehabilitation and education systems have been prioritised by specialist SLP organisations to ensure the sustainability of the future SLP in Cambodia.

Summary and conclusion

This paper acknowledges Cambodia’s commitment to the SDGs, while highlighting Cambodia’s limited SLP service coverage. To address multiple SDGs, significant development is required regarding availability, quality, location equity and breadth of practice areas across health, education and disability. Partnerships with the three key government ministries have been formally established and form the basis for the future development of a Cambodian SLP workforce and university education program. While current projects and initiatives may be small, collectively they contribute to the growth of the Cambodian SLP profession and momentum is growing to develop an internationally recognised SLP profession in Cambodia. These partnerships (SDG 17) contribute to the fulfilment of SDGs by reducing poverty (SDG 1) and inequalities (SDG 10) experienced by Cambodians with communication and/or swallowing disability, strengthening both health (SDG 3) and education systems (SDG 4) with the aim of a future robust, well-defined SLP workforce (SDG 8).

Acknowledgments

The Australia academics acknowledge the traditional custodians of Wiradjuri and Dharug Country where they live and work. The authors acknowledge the donors that make the work of OIC Cambodia possible, including OIC Australia, and within-country support of Government ministries, and local non-government organisations including OIC Cambodia and Speech Therapy Cambodia. In addition, the authors acknowledge the service facilities and speech therapy practitioners who participated in this study.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrahams, K., Kathard, H., Harty, M., & Pillay, M. (2019). Inequity and the professionalisation of speech-language pathology. Professionalism and Professions, 9, e 3285. doi:10.7577/pp.3285

- Bryce, R., & Bong, D. (2020). Situational review of Cambodian systems and progress related to building a SLP profession in Cambodia. [Unpublished report].

- Department of Planning and Health Information (2016). Health strategic plan 2016-2020. Royal Government of Cambodia: Phnom Penh

- GlobalEconomy.com (undated). Rural population, percent of total population, 2021 - Country rankingsi. www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/rural_population_percent/South-East-Asia

- Hopf, S., Crowe, K., Verdon, S., Blake, H.L., & McLeod, S. (2021). Advancing workplace diversity through the Culturally Responsive Teamwork Framework. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30, 1949–1961. doi:10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00380

- Ministry of Women’s Affairs of Cambodia (2014). Policy brief 9 RIGHTS: Vulnerable groups of women and girls. Cambodia gender assessment. www.mowa.gov.kh

- National Institute of Statistics, Directorate-General for Health, and ICF International (2015). Cambodia demographic and health survey 2014. National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, and ICF International. https://www.nis.gov.kh/index.php/en/17-cdhs/54-cambodia-demographic-and-health-survey-2010

- OECD (2017). Social protection system review of Cambodia, OECD development pathways. OECD Publishing: Paris.

- OIC Cambodia (2019). Lived experience of adults with communication disability in Cambodia [Unpublished report].

- Royal Government of Cambodia (2009). Law on the protection and the promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities. http://www.dac.org.kh/resource-center/download/Cambodia_Disability_Law_English.pdf

- Royal Government of Cambodia (2017). National social protection policy framework 2016-2025. https://nspc.gov.kh/Images/SPFF_English_2019_10_28_12_10_56.pdf

- Royal Government of Cambodia (2018). Cambodian sustainable development goals framework (2016-2030). https://data.opendevelopmentcambodia.net/laws_record/cambodian-sustainable-development-goals-framework-2016-2030

- Royal Government of Cambodia (2019a). Cambodia’s 2019 voluntary review on the implementation of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/23603Cambodia_VNR_SDPM_Approved.pdf

- Royal Government of Cambodia (2019b). National disability strategic plan 2019-2023. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/10/Cambodia_National-Disability-Strategic-Action-Plan-NDSP-2014-2018.pdf

- Sach, J.D., Kroll, C., Lafortune, C., Fuller, G., & Woelm, F. (2021). Sustainable development report 2021. The decade of action for the sustainable development goals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Salter, C., & Yeoh, W. (2017). Small steps towards a speech therapy profession in Cambodia: Lessons learned so far. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 2, 104–113. doi:10.1044/persp2.SIG17.104

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and Global Education Monitoring Report (GEMR) (2017). Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education. Policy paper 32/Fact sheet 44. UIC and GEMR.

- United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- United Nations (2015a). General Assembly Resolution Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf

- United Nations (2015b) Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- World Health Organization (2018). Access to rehabilitation in primary health care: An ongoing challenge: Technical series on primary health care. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1236081/retrieve

- World Health Organization (2019). Investing in the health workforce for the future. https://www.who.int/cambodia/news/feature-stories/detail/investing-in-thhealth-workforce-for-the-future

- World Medical Association (2022). WMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Wylie, K., McAllister, L., Davidson, B., Marshal, J., Amponsah, C., & Bampoe, J. O. (2017). Self-help and help-seeking for communication disability in Ghana: Implications for the development of communication disability rehabilitation services. Global Health, 13(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0317-6.