ABSTRACT

This article explores the emerging trajectory of creative arts-based research methods in practical theology. Creative arts-based approaches work with the embodied, material, imaginative, and sacred, foregrounding questions of representation and interpretation. Whilst seen as novel or emerging, creative methods fulfil key practical theological tasks and reveal the roots of the discipline as already creative and constructive. Drawing on Westfield’s engagement with poetry and poetic writing, Byrne’s studio-based visual arts practice, and Walton’s life writing and autoethnography, the article examines the distinctiveness of creative methods in representing lived experiences and generating new, liberative theologies. The article engages collaborative creative arts-based research to discuss practical and ethical issues in undertaking these methods. The paper concludes by reflecting on the possibilities for the future of practical theologies shaped through creative methods.

Introduction

In this article I explore the emerging trajectory of creative arts-based research methods in practical theology, arguing that these approaches offer generative engagement with the embodied, aesthetic, relational, and sacred. In the first section I outline where creative arts-based research methods are understood as emerging in practical theology, yet also enable a fulfilment of key practical theological tasks, revealing the roots of the discipline as already imaginative, creative, and constructive. Secondly, I consider the distinctiveness of creative arts-based methods in practical theology by highlighting three examples that work with poetry and poetic writing, studio-based visual art, and life writing respectively as methods of theological inquiry. Thirdly, I discuss the collaborative creative arts-based project ‘Connecting Stories’ that formed a key part of my doctoral research, focusing particularly on issues of meaning-making and ethical responsiveness. To conclude, I suggest potential avenues for the future of arts-based research in theological research and practice.

The creative arts-based research methods I focus on in this paper differ from broader theological discussions of the arts or theological aesthetics. A central aspect of creative research is undertaking the artistic process as a research method; researching through the practice of creative arts as a way of generating theological knowledge, rather than using artistic works as illustrations of theological points or a starting place for spiritual reflection. Creative arts-based researchers typically resist instrumentalising arts practice: the ‘use’ or technical application of creative methods and methodologies in order to produce stable outputs. Arts-based research is instead more unpredictable, more open to being shaped by various interactions with materials and collaborators in the process of research (Grierson Citation2009, 17). Due to this, I do not include here other valuable works that seek to offer a practical theology of aesthetics or the arts, for example Illman and Smith’s (Citation2013) discussion of a practical theological approach to the arts in which they discuss dance, music, film, theatre, fabric arts, and mural painting (see also for example Begbie Citation2001, Citation2002; de Gruchy Citation2001).

Within practical theology research methods remain contested ground, with debates continuing over the relationship between both qualitative and quantitative methods and practical theology, questioning what can be considered truly ‘theological’ about research (Graham Citation2013; Kaufman Citation2016; Swinton and Mowat Citation2016; Walton Citation2014).Footnote1 These debates have become a central feature of much of the discipline’s discussion of research methods. Yet the focus in these debates on categories of authority and normativity as the ‘key issues’ can reinforce a disciplinary ‘template’ that is ‘taken for granted as neutral’, obscuring where gendered, racial, and colonial power dynamics influence assumptions and understandings of what constitutes ‘key issues’ (Beaudoin and Turpin Citation2014; Goto Citation2016c). As Natalie Wigg-Stevenson contends, these ‘intratheological debates over authority and normativity’ have resulted in practical theologians largely failing to engage with critical methodological issues surrounding representation that are ‘already dated’ in other disciplines (Citation2018, 428). Furthermore, reflecting on empirical methods in ethnographic theology, she asserts that ethnographic theologians have ‘done little to nuance empirical strategies of representation beyond their wholesale acceptance or dismissal’ but have adopted methods ‘as if they were innocent’ and assumed the values ‘aligned with more scientific understandings of objectivity and neutrality’ in order to ‘frame our structures for assessing the merits of our claims’ (Citation2018, 427). Similarly, Heather Walton argues that the desire to secure the academic rigor of practical theology has resulted in remaining attached to critical analytic methods and thus also a ‘very positivistic approach toward human actions’ (Citation2014, 138; quoting Daniel Louw Citation2001, 330). Walton reflects that in the current engagement with methods in practical theology ‘it seems that theology is seen as a static resource rather than a creative response to the enchantment, wonder, and terror of the present age’ (Citation2018, 225).

In this light, my concern is not to position creative arts-based research as a solution to these wider debates, yet neither is it to use the set criteria of these debates to determine the value of creative arts-based research for practical theology. As arts researchers in wider social disciplines have articulated, creative arts-based research is generative precisely because it questions the categories by which research processes and findings are judged, reframes how meaning is made, and provides an orientation toward the unknown and ineffable (see Cole and Knowles Citation2008; Grierson and Brearley Citation2009; Barone and Eisner Citation2011; Osei-Kofi Citation2013; Savin-Baden and Wimpenny Citation2014). My argument is not that practical theologians should undertake creative research practices because these methods produce more reliable data or ‘better representations’ of others, ourselves, and the divine. Belief in the inadequacy of other research methods or simply a love or talent for art are not sufficient reasons to do arts-based research (Barone and Eisner Citation2011, 13). Rather, I suggest that creative methods in practical theology take us further into what is complex, contradictory, and uncertain in our attempts to trace the sacred in our practices of liturgy and learning, protest and peacemaking, and everyday life.

An ‘emerging shoot’ revealing deep roots

Creative arts-based research includes a wide range of practices, from visual arts, performance, dance, and music, to creative writing and poetry. As research practices in theology, creative arts-based methods are still emerging, although there are already a wide range of approaches and different artistic practices in the field, including: poetry and poetic writing (Westfield Citation2001; Slee Citation2011); life writing and creative non-fiction (Walton Citation2014, Citation2015; Couture Citation2016); performance, drama, and theatre (Reddie Citation2006; Mesner Citation2014; Falcone Citation2018); studio based visual arts (Byrne Citation2017); mixed media sculpture in theological education (Goto Citation2016b); narrated photography and photovoice (Cruz Citation2008; Ward and Dunlop Citation2011; Dunlop and Ward Citation2012); and music (Paterson Citation2017). Additionally, previous BIAPT conferences have included artists and poets in residence who have hosted workshops and created responses to the proceedings. Creative arts methods may be part of conducting research with participants and communities, generating data and examining one’s own experiences or the life and liturgy of a faith community. Alternatively, a particular creative practice such as writing poetry, constructing installations, or creating a print can be a way of investigating particular theological issues; sometimes a critical commentary is provided alongside this work. In this way, creative arts-based research can be a stand-alone research method or can be a way of adapting more ‘traditional’ research methods.

Creative and artistic methods in practical theology are considered novel and even controversial to the discipline, yet these methods are also understood as offering generative potential for fulfilling the core tasks of practical theology. In Invitation to Research in Practical Theology, Zöe Bennett, Elaine Graham, Stephen Pattison, and Heather Walton recognise that as the field has typically focused on research ‘that makes a practical difference to the life of Church and world’, it may be difficult for practical theology to engage in creative research methods that ‘do not appear to be as self-evidently “useful” as the established analytic tools with which it is familiar’ (Citation2018, 154). Yet, they argue that by working with this different approach of creative methods, practical theology may be able to re-engage with homiletics, liturgy, sacred music and spiritual discipline as creative practices, as well as the creative arts-based practices developed in wider fields of social research (Citation2018, 152–3). For Bennett, Graham, Pattison and Walton, creative arts approaches enable a fulfilment of the ‘mystical, prophetic, and spiritual inheritance’ of practical theology, creating ‘new possibilities in theological thinking, social engagement and ecclesial practice’ (154). In their framing, creative arts-based research generates both new knowledges and practices, whilst also offering a recovery of the aspects of practical theology that may have been side-lined in the efforts to secure practical theology as a useful academic discipline.

In a similar way, Courtney Goto describes the process of inviting her students to create mixed media sculptures as a way of learning to ‘discover, contemplate, and express dimensions of their faith that they know but cannot express fully in words’ (Citation2016b, 80). Goto comments that such practices of researching with and through the arts may be seen as ‘deviating’ from standard practice in theology, yet this ‘decentring’ enables a reconnection with ‘an expanded notion of reflecting that gives form to the sayable and the ineffable’ (Citation2016b, 84). Surveying what she terms as an ‘evolving trajectory of ethnographic and qualitative research’, Moschella (Citation2018) indicates the relevance of artistic and poetic approaches for practice-orientated research in a short discussion on poetics and creative non-fiction. Moschella notes in particular the ‘burgeoning creative, therapeutic, and prophetic capacities’ of this work and the potential for creating ‘sensitive and compelling accounts’ that generate new insights and understandings (Citation2018, 24). The development of these research approaches is reflective of the ‘turn to culture’ in wider theological and religious studies, a recovery of the ‘incarnational, or embodied nature’ of academic theology and a reintroduction of ‘a creative tension between the particular and the universal in theological reflection’ (Moschella Citation2018, 6; quoting Snyder Citation2014).

However, whilst novel and emerging, creative methods also reveal that, at its roots, all theological research is a constructive, creative practice. Goto proposes that modes of ‘playing with/through art’ foreground the constructive, creative element in all theological research, stating:

The fact is that we are always imagining, creating, constructing, and fashioning answers to theological questions (as well as re-forming the questions) – perhaps not with paint, marble, or music but with images, ideas, and approaches that are by definition interpretations. In other words, we have been functioning as theologians, imaginatively, all along – without recognising what we have done as creative, aesthetic, and theological. (Citation2016b, 84, italics original)

As feminist, queer, and postcolonial theologians have been articulating for many decades, no knowledge or data arrives to us unmediated. Engaging these perspectives, creative research can foreground where assumptions have been made about the supposed neutrality of certain methods, recognising that all research methods and practices are already shaping and shaped by particular worldviews. By revealing the importance of ‘making’ in any theological research journey, creative approaches highlight that

no methods, however mechanical or quantitative, produce meanings automatically, channeling data into predetermined outcomes. Researchers always shape and craft materials into new forms. These do not present a mirror to some pre-existing reality. Rather, they are new makings that change the way we see the world and so our basic epistemology and ontology. They generate insight. (Bennett et al. Citation2018, 152).

The distinctiveness of creative methods

Whilst affirming that practical theology is already constructive and imaginative, it is also crucial to recognise the distinctiveness of creative arts-based research. As Elizabeth Grierson notes, creative research enables a ‘particular kind of making and doing’, that has the ‘components of aesthetics and the potential always of making-new as a defining characteristic’ (Citation2009, 18, emphasis mine). It is a particular kind of making and doing that engages the process of crafting, making, performing, and visualising in literal ways, foregrounding how ‘[n]ew knowledge is made possible through the materiality of practice itself’ (Grierson and Brearley Citation2009, 5). Arts-based research often runs contrary to the forms of research framed by the ‘metaphysical desire to make things safe and secure’ (Barone and Eisner Citation2011, 15; quoting Caputo Citation1987, 7), working to ‘evoke’ rather than ‘denote’ meanings (Leavy Citation2015, 22). Creative arts-based research emphasises the embodied, emotive, material, intuitive, and performative aspects of making meaning, which are ways of knowing that have typically been elided and ignored in western, white, male, and heterosexual academic work in favour of objectivity, rationality, and certainty (Beaudoin and Turpin Citation2014; Goto Citation2018; Osei-Kofi Citation2013). Here, I offer three examples that demonstrate the distinctiveness of creative arts as a method of theological inquiry: Nancy Lynne Westfield’s engagement with poetic prose and poetry; Libby Byrne’s studio-based practice in visual art; and Heather Walton’s life writing and autoethnography. In the discussions below, I highlight their articulations of how creative practices enable them to challenge dominant theologies, to represent lived experiences, and to generate new theological understandings.

Nancy Lynne Westfield articulates her choice to work with poetic prose and poetry in Dear Sisters (Citation2001) as a way of doing justice to the experiences of her participants in her work on womanist practices of hospitality. She reflects that ‘as an artist I felt compelled to take all that I had seen, felt, learned, relearned, remembered, thought, and experienced from and with the women of the research, and in some way create a work that represented the power of our bodies, minds, and souls to be and become resilient’ (Citation2001, 4). She indicates that in Womanist challenges to the dominant paradigm, ‘artistic renderings’ such as those of Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker have been part of recognising the ‘wellsprings of African American woman’s religious experience’ (Citation2001, 19). Yet she suggests that ‘[f]ew Christian scholars have made the artistic process part-and-parcel of their scholarly methodology’ (Citation2001, 19, emphasis mine).

Engagement with poetry enables Westfield to develop a form of scholarship reflective of the experiences and knowledge of the African American women’s literary group that formed the focus of her research. For Westfield, shaping her work through the artistic and aesthetic is a way of refusing to convey her scholarship ‘through the mainstream male voice that the scholarly guilds employ for communication’ (Citation2001, 22). She goes on to say ‘I understand that art, in and of itself, is an act of resistance, an act of humanness, an act of freedom born out of liberative activity as well as a personal experience of grace. I wanted my work to embody the voices of the women by capturing the voices through poetry, not simply reporting upon their voices as subjects’ (Citation2001, 22). The artistic and ethical are thus deeply linked for Westfield as she explains that this artistic approach recognises the ‘profound complexity’ of her participants and ‘allows description without dissection, exploration without violation, interpretation without devaluation or redaction’ (Citation2001, 10). In this, Westfield highlights where creative research is not simply an alternative way of presenting participants’ experiences but involves a refusal of theological practices prone to objectifying and essentialising human lives.

Describing the use of studio-based art practice as a site for theological making, Libby Byrne argues for the possibilities of a practice-led theology that is at once contemplative, reflexive, and systematic. In Byrne’s account, reflexive studio practice is a way of working on a ‘cohesive body of artwork and accompanying exegesis’, the success of which is ‘often illuminated by the degree to which the process sheds new light upon the questions that have been posed and explored’ (Citation2016, 63, emphasis mine). Here Byrne echoes the emphasis on process in wider creative research, whereby methods are not to be applied in a technical fashion but are ‘emergent and subject to repeated adjustment’, part of a reflexive process which shapes the researcher, as much as being shaped by her (Barrett Citation2007, 6).

Byrne considers specific art methods as a way of exploring theological questions about healing and her own experiences of living with multiple sclerosis. For example, she describes ‘painting over old works to create a series of palimpsests’ that ‘held the memory of a painting that had once existed but was no longer able to be seen, thereby speaking of life before and after the serious diagnosis of multiple sclerosis’ (Byrne Citation2017, 201). This reflexive art practice is a way of ‘making sense’ with and through the materials; however, Byrne is also clear that this ‘making sense’ is not about certainty, but receptiveness ‘to the possibility of revision and transformation’ and also uncovering ‘what cannot be known’ (Citation2017, 200). She describes openness to viewer engagement at an exhibition as well as the way changing sunlight and space challenge her perceptions of the work, thus allowing the studio to be ‘more than a home for ideas, it is a home for God and a site for theology in the making’ (Citation2017, 206).

Heather Walton engages with spiritual life writing, for example in Not Eden (Citation2015), and also often offers creative autoethnographic reflections as part of her argument in more traditional practical theology articles (Citation2018, Citation2019). Placing contemporary spiritual life writing as a re-forming of a long tradition, Walton clarifies that life writing is ‘more open and capacious than autobiography’, offering space for creative construction and hybrid forms that witness to the complexity and ambiguity of lived lives (Citation2015, 33). Walton argues that, although working through one’s own lived experiences, such practices can ‘think beyond the personal and therapeutic aspects of autoethnography and embrace its prophetic and disclosive potential’ (Citation2014, 9), thus enabling such works to be publicly orientated and to generate ‘radical visions out of the earthy, commonplace materials of lived experience’ (Citation2015, 3). This enables critical reflection on aspects of embodied experience that have been overlooked in theology, and Walton has written sensitive and challenging work from her own experiences, including of infertility. She relates: ‘[m]y own deep awareness of embodiment was stamped upon me not by sensuous enjoyment, aesthetic intensity, feminist epistemology or sublime experiences in nature. It came through infertility. The grinding, everyday pain of being unable to conceive’ (Citation2015, 26).

Walton reflects that practical theology has frequently aimed for writing styles that seek to present information in factual, neutral, and authoritative ways, yet creative life writing involves working with lived experiences – such as those noted above – that ‘are not easily rendered in plain terms’ (Walton Citation2014, 27; Citation2015, 133–4). She foregrounds the problems of representation in her work, articulating that creative work does not sidestep these but takes us further into the challenges of representing experiences of grace, loss, trauma, and the divine. As such, in discussing life writing and in her own creative practice, Walton seeks a non-innocent writing, one that ‘has lost all nostalgia for the pure representations of pure forms. A writing that lives spiritually in this world – while still yearning in its travails’ (Citation2015, 42). This approach enables Walton’s creative theological practice to critically affirm the sacred in the everyday, in experiences of trauma, joy, grief, and uncertainty, as she articulates that ‘an embodied and relational self does not seek to lift itself beyond this messy, complicated, world, but rather seeks to adore the sacred within its blemished beauty’ (Citation2015, 20).

In these examples, creative arts-based methods are not separate to theological work, nor are they simply more compelling or aesthetic ways of getting the same points across. Rather, these creative practices form essential argument. They show where creative research engages the challenges of representation, interpretation, and re-making in dealing with the complexities of lived experiences and spiritualities, including recognising the uncertain or unknown.

Meaning-making and ethics in a collaborative arts project

In this section I offer a brief example of the collaborative creative-arts based methods undertaken as part of my doctoral research examining how sharing lived experiences of marginalisation creates transformation. I focus particularly on the processes of meaning-making at work in the creative and collaborative project, highlighting specific practical and ethical considerations arising in the research. The project – ‘Connecting Stories’ – was developed in collaboration with Glasgow-based Poverty Truth Community (PTC), an organisation bringing together people with various experiences of poverty and those in positions of power in order to share stories and work toward social change. After initial discussions about collaborating, we formed a small planning group comprised of myself, two PTC members ‘Kitty’ and ‘Victoire’,Footnote2 and the PTC co-ordinator; together we designed a series of creative reflection workshops for women who have been involved in PTC. These planning sessions involved creative exercises to bring together our different skills and ideas in directing the project, as well as discussing ethical issues around working with people’s ongoing lived experiences.

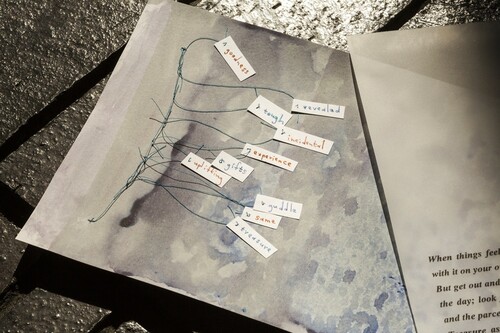

In the workshops, ten women took part in creative exercises that encouraged the generation of text and images reflecting on their activism and lived experience stories in the past decades of PTC’s work and imagining the future of this movement. In facilitating this arts-based process, I aimed to have ‘respect for [people’s] autonomy and capacity to want to create’, appreciating ‘how engagement with creative practices may have implications in terms of leaving people feeling vulnerable’ (Savin-Baden and Wimpenny Citation2014, 42). We developed a series of small creative pieces based on collective and individual stories; often I would work in collaboration with a participant who would make and write where they felt able, offering a way of entering into a process of negotiating meaning together (Savin-Baden and Wimpenny Citation2014, 88–89). These pieces worked with objects like brown envelopes, DWP forms, old wallpaper, thread, PTC reports, and tea-boxes, using processes of inking, printing, painting, stitching, and collage to bring together text, texture, and visuals (see and ). By the end, we had creative work that covered various experiences and topics including: the impact of a broken washing machine; welfare cuts and assessments; activism around food poverty; holding on to a sense of self through the UK asylum system; and recognising the gifts and struggles of others in working together for change.

Figure 1. Photo. Creative piece from Connecting Stories, ‘Root and Branch’ made from old wallpaper. Copyright the author and Anneleen Lindsay.

Figure 2. Photo. Creative piece from Connecting Stories: ‘washing line’ exploring fragile goodness of activist practices. Copyright the author and Anneleen Lindsay.

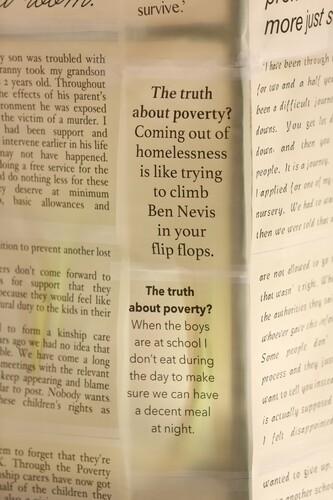

As the group were keen to share their learning and creative pieces, we hosted an event that would encourage a wider community to reflect on the issues we had been exploring. We created an interactive installation as ‘installation requires viewers to engage in a dynamic process of meaning-making that is contingent upon searching for and making connections between what is represented, what is suggested, and what is imagined’ (O’Donoghue Citation2011, 644). Initially we considered a quiet, reflective space but quickly realised that the PTC community is full of lively chat and laughter, and so we made a labyrinth of multiple paths using chairs in order to encourage viewers to encounter one another and sit and chat in the midst of the exhibition. Within the labyrinth, we placed creative pieces made by the group, leading to a central installation of two tents made from PTC members’ stories (see and ). In considering participants’ engagement with the exhibition, we identified the usefulness of ‘opportunities for audiences to debrief or “talk-back” to arts-based representations’ and provided reflection booklets and a response book (Sinding, Gray, and Nisker Citation2008, 463). The reflection booklets elicited responses from viewers about the exhibition and their involvement with PTC, enabling those of us in the creative workshop group to see how viewers had made meaning through interacting with the installation. Many of these were meanings that we had not anticipated or intended, indicating different ways in which viewers made connections between features of the installation. For example, one PTC community member interpreted the embodied element of moving within the labyrinth through a quote on one of the tents: ‘the maze is an excellent device/design – illustrating the difficulties of coming out of poverty – how complex and challenging (like climbing Ben Nevis in your flip flops)’.

Figure 3. Photo. Labyrinth and tents as part of forming Connecting Stories installation. Copyright the author and Anneleen Lindsay.

Figure 4. Photo. Tents made from stories shared by PTC members. Copyright the author and Anneleen Lindsay.

Following the conclusion of Connecting Stories, I faced choices and ethical considerations in presenting the project as part of my doctoral thesis; I discuss two areas here. Firstly, how could I draw on and represent all the findings amassed through the project: my research journal; notes from the workshops; the creative pieces; photographs from the exhibition; formal feedback from viewers and participants; and the myriad of conversations, stories, and laughter shared in the project? As I noted above, this is never simply a process of ‘writing up’ or ‘merely the transcribing of some reality’ as the writing process is itself also a creative act in which we construct, discover, and suggest meaning (Lincoln, Lynham, and Guba Citation2011, 124). I aimed to create research texts as ‘sites of aesthetic contemplation’ that ‘engage researchers and readers/viewers as co-creators of the text’ as a way of running counter to conventional models ‘that treat research texts as vehicles for the display of a fixed meaning created by the researcher’ (Cole and McIntyre Citation2004, 8). In the text, I created a ‘virtual tour’ of the installation, guiding the reader around the labyrinth (see Cole and McIntyre Citation2004, Citation2008), punctuating this with autoethnographic and ethnographic sections that describe the workshops and the process of making the creative pieces and installation.

Secondly, making creative pieces in collaborative research raises questions around ownership and attribution. As Savin-Baden and Wimpenny note, in arts-related research it is ‘important to consider to whom the work belongs, how the study findings will be disseminated, and over what time frame’ (Citation2014, 42). As a collaborative project, who could access and circulate these materials? If participants are to be anonymised in the wider research, what are the implications for giving attribution to their creative work? Can creative works be properly ‘anonymised’ without removing some of the key artistic and expressive aspects? In dealing with these questions, we decided that the installation credit should be collective, with individual participants highlighting their specific personal contributions within the context of showing others round. We also hired a photographer to document the artworks, installation and people’s interactions so that the photographs could be used by PTC in the future and in my research.

However, these questions are as much applied to the collaborative learning and knowledge emerging from the project as they are to specific creative pieces. To whom does this work and knowledge belong, and how can it be properly attributed? Whose power is served in the creation of representations of particular communities? Can and should collaborative, creative work be fully ‘translated’ from community settings to academic texts? Creative arts-based methods thus foreground the need to deal with where practical theological research often extracts time, energy, and critical knowledge from communities in service of a researcher’s own power in creating authoritative interpretations. Aware of the challenges of representation in practical theology, I aim to incorporate ‘representations of the community that resist interrogation’ by creating encounters with and through creative pieces and texts, allowing ‘the other to be seen and known in a variety of ways’ (Goto Citation2018, 157). As Goto suggests, various creative arts forms can ‘defy concretization and domestication, especially if the theorist is sensitive to this’ (Goto Citation2018, 157). In the creation of ‘aesthetic texts’, I also aimed to gesture to the experiences and learning of others that cannot be pinned down or recuperated into academic texts, recognising the possibilities of knowledges that exist beyond and do not belong to researchers and their disciplinary fields (see Ahmed Citation2000, 64).

I experienced this collaborative creative research as deeply challenging and generative, in part because it was not a smooth, predictable research process. The multiple forms of collaboratively making meaning can be unsettling, and so it was important as a researcher to ‘learn to live with uncertainty, become comfortable with discomfort, and be excited by the insights and creativity’ emerging from unpredictable and thorny moments (Barndt Citation2008, 360). Whilst I had intellectually affirmed the value of these creative practices, it was only through this engagement with the embodied practices of making and imagining in this community that I was enabled to learn about creative research practices, about the knowledge and ways of knowing my collaborators wished to share, and about ways of constructing practical theologies with and through lived experiences. Furthermore, it enabled me to sit with the silences, uncertainties, and ellipses in the research, all the grief and trauma and joy and sacred in this community that could not be fully known or represented.

Conclusion

In exploring creative arts-based research in practical theology, I have highlighted where creative methods critically engage with how theological meanings are made and shaped, foregrounding the complexities of interpretation and representation of ourselves, others, and the divine. Drawing on the work of Westfield, Byrne, and Walton, as well as my own research, I have indicated where creative methods work with and through embodiment, materiality, intuition, and imagination as valid ways of theological knowing, especially for experiences that dominant theologies have ignored. However, of necessity, this article has presented an argument about creative arts-based research, highlighting critical issues and particular works, rather than itself being a piece of creative arts research; I encourage others to experience the fullness of some of the examples I have cited – the life writing, the poetry, the visual art, the performances. This is again a challenge for the future of practical theology, to consider the ‘outputs’ and material resources that are produced as ways of sharing and highlighting our reflections.

As we seek in practical theology to respond to the challenges, changes, and injustices in our current times – to make meaning with what is at once deeply personal, political, material, and spiritual – I encourage others to explore, play, and fashion their own theological inquiries through different creative practices and processes. Forms of artistic play (Goto Citation2016a) and ‘artful analysis’ can be undertaken without necessarily having to commit to the production of a final artistic ‘end product’ (Butler-Kisber Citation2005, 205), as processes that are committed to being open to the embodied, imaginative, intuitive, and emergent nature of interpretation. Although I have focused here on poetry, life writing, studio based visual art, and collaborative mixed media and installation, I suggest that the future of practical theological reflection and inquiry holds great scope for multiple creative processes including sculpture, print-making, dance, music, film-making, liturgy, musical composition, liturgy, performance, and protest. Creative research practices may be more unpredictable than practical theologians have become used to, yet in embracing such vulnerability, uncertainty, and multiple ways of knowing creative arts practices gesture toward the sacred in the embodied, material, and everyday.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wren Radford

Wren Radford holds a PhD in Theology and Religious Studies from the University of Glasgow. Their research into theology and inequality includes focusing on areas of poverty, disability, gender, embodiment, and creative practice.

Notes

1 This has included debates over qualitative versus quantitative research, yet many practical theologians aim to move away from characterisations of qualitative as ‘soft, subjective, and unscientific’ and quantitative as ‘failing to capture the meanings that inform human action’ (Osmer Citation2008, 50; see also Dreyer Citation2009). Both qualitative and quantitative approaches make valuable contributions to the discipline, and many practical theologians combine both in mixed methods approaches. Similarly, ‘empirical theology’ is variously used to describe a range of quantitative, qualitative, and blended approaches (Francis, Robbins, and Astely Citation2009). The critiques raised here do not apply solely to qualitative or quantitative research, but more broadly to how debates over methods in practical theology can obscure either the vital ethical questioning in other disciplines, or the responsive nature of theology.

2 Alternative names have been chosen by participants.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2000. “Who Knows? Knowing Strangers and Strangerness.” Australian Feminist Studies 15 (31): 49–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713611918.

- Barndt, Deborah. 2008. “Touching Minds and Hearts: Community Arts as Collaborative Research.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by J. Gary Knowles and Ardra L. Cole, 351–362. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Barone, Tom, and Elliot W Eisner. 2011. Arts Based Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Barrett, Estelle. 2007. “Introduction.” In Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, edited by Estelle Barrett and Barbara Bolt, 1–14. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Beaudoin, Tom, and Katherine Turpin. 2014. “White Practical Theology.” In Opening the Field of Practical Theology: An Introduction, edited by Kathleen A. Cahalan and Gordon S. Mikoski, 251–269. Maryland and Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Begbie, Jeremy. 2001. Beholding the Glory: Incarnation Through the Arts. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

- Begbie, Jeremy. 2002. Sounding the Depths: Theology Through the Arts. London: SCM.

- Bennett, Zöe, Elaine Graham, Stephen Pattison, and Heather Walton. 2018. Invitation to Research in Practical Theology. Abingdon, Oxon, and New York: Routledge.

- Butler-Kisber, Lynn. 2005. “The Potential of Artful Analysis and Portrayals in Qualitative Inquiry.” Counterpoints 276: 203–217.

- Byrne, Libby. 2016. Healing Art and the Art of Healing. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Divinity. Accessed 25th August 2019. https://repository.divinity.edu.au/2043/1/FinishedPhDThesis-LibbyByrne.pdf.

- Byrne, Libby. 2017. “Practice-led Theology: The Studio as a Site for Theology in the Making.” Theology 120 (3): 197–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0040571X16684434.

- Caputo, John D. 1987. Radical Hermeneutics: Repetition, Deconstruction and the Hermeneutic Project. Indianapolis, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Cole, Ardra L., and Maura McIntyre. 2004. “Research as Aesthetic Contemplation: The Role of The Audience in Research Interpretation.” Educational Insights 9 (1), Accessed 14th January 2019. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download? doi=10.1.1.572.3206&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Cole, Ardra L., and Maura McIntyre. 2008. “Installation art-as-Research.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by J. G. Knowles and A. L. Cole, 287–298. London, England: Sage.

- Couture, Pamela. 2016. We Are Not All Victims: Local Peacebuilding in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Zurich: LIT Verlag.

- Cruz, Faustino. 2008. “Immigrant Faith Communities as Interpreters: Educating for Participatory Action.” New Theology Review 21 (4): 27–37.

- de Gruchy, John W. 2001. Christianity, Art and Transformation: Theological Aesthetics in the Struggle for Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dreyer, Jaco S. 2009. “Establishing Truth from Participation and Distanciation in Empirical Theology.” In Empirical Theology in Texts and Tables: Qualitative, Quantitative and Comparative Perspectives, edited by Leslie J. Francis, Mandy Robbins, and Jeff Astley. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Dunlop, Sarah, and Pete Ward. 2012. “From Obligation to Consumption in Two-and-a-Half Hours: A Visual Exploration of the Sacred with Young Polish Migrants.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 27 (3): 433–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2012.722037.

- Falcone, John. 2018. “Body and Spirit Together: Theatre of the Oppressed, Pragmatist Semiotics, and Practical Theological Method.” Society for the Arts in Religious and Theological Studies ARTS 30 (1), https://www.societyarts.org/in-the-study-body-and-spirit-together.html#.

- Francis, Leslie J., Mandy Robbins, and Jeff Astely. 2009. Empirical Theology in Texts and Tables: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Comparative Perspectives. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Goto, Courtney. 2016a. The Grace of Playing: Pedagogies for Leaning in to God’s New Creation. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications.

- Goto, Courtney. 2016b. “Reflecting Theologically by Creating Art: Giving Form to More Than We Can Say.” Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry 36: 78–92. http://journals.sfu.ca/rpfs/index.php/rpfs/article/view/426/413.

- Goto, Courtney. 2016c. “Writing in Compliance with the Racialized ‘Zoo’ of Practical Theology.” In Conundrums in Practical Theology, edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, and Joyce Ann Mercer, 110–133. Leiden: Brill.

- Goto, Courtney T. 2018. Taking on Practical Theology: The Idolization of Context and the Hope of Community. Leiden: Brill.

- Graham, Elaine. 2013. “Is Practical Theology a Form of ‘Action Research’?” International Journal of Practical Theology 17 (1): 148–178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt-2013-0010

- Grierson, Elizabeth. 2009. “Ways of Knowing and Being: Navigating the Conditions of Knowledge and Becoming a Creative Subject.” In Creative Arts Research: Narratives of Methodologies and Practices, edited by Elizabeth Grierson and Laura Brearley, 17–32. Rotterdam, Boston: Sense Publishers.

- Grierson, Elizabeth, and Laura Brearley. 2009. Creative Arts Research: Narratives of Methodologies and Practices. Rotterdam and Boston: Sense Publishers.

- Illman, Ruth, and Alan Smith. 2013. Theology and the Arts: Engaging Faith. New York and London: Routledge.

- Kara, Helen. 2015. Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Kaufman, Tone Stangeland. 2016. “From the Outside, Within, or In Between? Normativity at Work in Empirical Practical Theological Research.” In Conundrums in Practical Theology, edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Joyce Mercer, 134–162. Boston: Brill.

- Knowles, J. Gary, and Ardra L. Cole, eds. 2008. Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Leavy, Patricia. 2015. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. Second Edition. New York, London: The Guilford Press.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., Susan A. Lynham, and Egon G Guba. 2011. “Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences, Revisited.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, Fourth Edition, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 97–128. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

- Louw, Daniel. 2001. “Creative Hope and Imagination in a Practical Theology of Aesthetic (Artistic) Reason.” In Creativity, Imagination and Criticism: The Expressive Dimension in Practical Theology, edited by Paul Ballard and Pamela Couture, 91–104. Fairwater, Cardiff: Cardiff Academic Press.

- Mesner, Kerr. 2014. Wrestling with the Angels of Ambiguity: Scholarship in the In-between: Queer Theology/ Performative Autoethnography. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Accessed 26 November 2018. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0135575.

- Moschella, Mary Clark. 2018. “Practice Matters: New Directions in Ethnography and Qualitative Research.” In Pastoral Theology and Care: Critical Trajectories in Theory and Practice, edited by Nancy J. Ramsey, 5–30. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

- O’Donoghue, Dónal. 2011. “Doing and Disseminating Visual Research: Visual Arts Based Approaches.” In The Sage Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by Eric Margolis and Luc Pauwels, 638–650. London, Los Angeles: Sage.

- Osei-Kofi, Nana. 2013. “The Emancipatory Potential of Arts-Based Research for Social Justice.” Equity & Excellence in Education 46 (1): 135–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2013.750202.

- Osmer, Richard. 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans.

- Paterson, Michael Sean. 2017. Kinship in the borderlands of praxis: A theological performance auto/ethnography. DPT thesis, University of Glasgow.

- Reddie, Anthony. 2006. Dramatizing Theologies: A Participative Approach to Black God-Talk. London: Routledge.

- Savin-Baden, Maggie, and Katherine Wimpenny. 2014. A Practical Guide to Arts-Related Research. Rotterdam. Boston and Taipei: Sense Publishers.

- Sinding, Christine, Ross Gray, and Jeff Nisker. 2008. “Ethical Issues and Issues of Ethics.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by J. Gary Knowles and Ardra L. Cole, 495–468. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Slee, Nicola. 2011. Seeking the Risen Christa. London: SPCK.

- Snyder, Timothy K. 2014. “Theological Ethnography: Embodied.” The Other Journal 23 (5), Accessed 26 November 2018. https://theotherjournal.com/2014/05/27/theological-ethnography-embodied/.

- Swinton, John, and Harriet Mowat. 2016. Practical Theology and Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. London: SCM Press.

- Walton, Heather. 2014. Writing Methods in Theological Reflection. London: SCM Press.

- Walton, Heather. 2015. Not Eden: Spiritual Life Writing for This World. London: SCM Press.

- Walton, Heather. 2018. “We Have Never Been Theologians: Postsecularism and Practical Theology.” Practical Theology 11 (3): 218–230. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1756073X.2018.1461489.

- Walton, Heather. 2019. “A Theopoetics of Practice: Re-Forming in Practical Theology.” International Journal of Practical Theology 23 (1): 3–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt-2018-0033.

- Ward, Pete, and Sarah Dunlop. 2011. “Practical Theology and the Ordinary.” Practical Theology 4 (3): 295–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/prth.v4i3.295.

- Westfield, Nancy Lynne. 2001. Dear Sisters: A Womanist Practice of Hospitality. Cleveland: Pilgrim Press.

- Wigg-Stevenson, Natalie. 2018. “What’s Really Going on: Ethnographic Theology and the Production of Theological Knowledge.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 18 (6): 423–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708617744576.