This is a collection of essays that discussed the nature of postmodernism and its plausibility in South Korea in the early 1990s. In the mid-1980s, the Korean art community was split between two opposing factions: Dansaekhwa, or monochrome painting, as a dominant school of “Korean Modernism” and the radical art movement of Minjung misul, or People’s art.

Dansaekhwa is an artistic movement that emerged in the mid-1970s, characterized by restrained and refined abstract paintings using neutral colors. Although the works of Dansaekhwa are comparable in their reduced forms to American Color field painting, Minimalism, and Japanese Mono-ha, Dansaekhwa artists paid more attention to the material properties of conventional media, such as canvas, paper, paint and pencil, and emphasized the contemplative nature of their bodily discipline in exercising the repetitive motions to create the abstract patterns.Footnote1 By the late 1970s, Dansaekhwa’s self-referentiality and rejection of pictorialism were firmly established as a strict norm of academic and institutional art in Korea. Under the leadership of Park Seo-bo, the charismatic founder and de-facto leader of Dansaekhwa, the school served as a dominant force, which exerted tremendous influence on the Korean art scene.

In the early 1980s, leftist artists began challenging the stifling authority and political insouciance of Dansaekhwa. Indeed, the mid-1980s in Korea was the era of revolution. Progressive artists and critics, who organized collective actions to promote their desire for democracy and human rights under the authoritarian government, initiated a political and populist art movement in the late 1970s known as Minjung misul.Footnote2 Their protests for political change were intensified in the wake of the Gwangju Democratization movement, and consequently many works of Minjung misul were frequently censored and confiscated. This governmental suppression reached its climax in July of 1985, when police forcefully shut down the group exhibition of Minjung misul, 1985: The Power of Twenties of Korean Art, held in the Arab Cultural Center in Seoul. This sparked the grand union of leftist artists and activists across the country to organize the Council for People’s Art (Minjung Misul Hyeobuihwe, a.k.a. Minmihyeop). The protagonists of the Minjung Art movement saw Dansaekhwa’s aesthetics of emptiness and promotion of transcendence through contemplative gestures as a symptom of political apathy, or worse, subservience to the military dictatorship.

The turn of the decade, however, marked a decisive turning point in Korean society. In 1987, the pro-democracy demonstrations, which were primarily carried out by college students and leftist activists, became widely supported by middle class citizens. Responding to the overwhelming popular desire for political reforms, the presidential candidate of the ruling party, who was actually designated as the next president, stunningly announced a direct election for the first time after 16 years of junta government. The next year, the 1988 Seoul Olympics drew the largest audience worldwide without any serious Cold War boycott for the first time in 12 years, following previous boycotts of Moscow and Los Angeles. This dramatically improved Korea’s international reputation and paved the way for domestic political and social confidence. The Seoul Olympics turned out to be the last Olympic Games for the Soviet Union and East Germany, because of the collapse of communism in East Central Europe and the Soviet Union’s dissolution. With these grand historical, social, and political changes, the Minjung art movement lost its ideological battle ground, as its chief enemy—the military dictatorship—had disappeared and democracy had been achieved, at least institutionally.

Discourses about postmodernism as a critical theory, an artistic style, and a social phenomenon arrived on the Korean shore at the moment that this ideological void emerged for progressive intellectuals and left-wing political activists. For leftist critics of both literature and the visual arts in Korea, who advocated realism as a legitimate style for political enlightenment, the eclecticism and relativism of postmodernism seemed to be the new face of an old enemy. That is, it represented another cultural logic justifying capitalism forcibly transplanted from the West. On the other hand, conservative critics—who promoted modernism in art and literature—reincorporated postmodernism as both a theory and a specific mode of artistic practice that could register the rapid social changes of the globalized era, though not without suspicions and challenges. The Korean translations of ‘postmodernism’ into multiple terms, such as ‘de-modernism’ (tal-modeonism), ‘anti-modernism’ (ban-modeonism), and ‘late-modernism’ (hugi-modenonism), along with ‘post-modernism’ (post-modeonism), reflect confusions and heterogeneous understandings of this new critical term.Footnote3

The essays selected for this volume represent the two opposing factions. Jeong Jeong-ho and Kang Naehui are English literature scholars, who first introduced postmodernism as a literary theory to Korean readers. The debates regarding the possibility or plausibility of postmodernism in Korea were first initiated in literature, along with the questions about the validity of “realism” as an ideologically radical and politically subversive style of literature since the 1970s. Because the challenges to realism and its tension with modernism in visual art appeared in the 1980s, many art critics and artists were highly influenced by the literary critics and their debates that happened a decade earlier. In the controversy surrounding the status of postmodernism in Korean art, these two authors’ cautious approach to its acceptance and their understanding of the social condition in general were especially influential.

In this introductory essay, Jeong and Kang described the spatial experience of Lotte World, where the underground passageway from the Jamsil subway station leads to an indoor shopping mall and an amusement park, Lotte World Adventure, which opened in Seoul in 1989. For them, Lotte World Adventure was an essentially postmodern space, where the power of the state and a conglomerate were in the cultural creation of fantasy. Different from Disney Land, for example, they argued that Lotte World erases the borderline between the inside and outside, consumption and entertainment, fantasy and reality, and eventually immerses the consumers in the governing ideology of capitalism. They claimed that postmodernism as a cultural theory is necessary, because it could provide a framework for understanding these new cultural aspects of capitalism that had landed in Korea. Their analysis of Lotte World Adventure has been frequently quoted in describing the Korean condition of postmodern culture by art critics.

While Jeong and Kang acknowledge postmodernism as a cultural symptom of consumer-oriented, multi-national capitalism of Korea, they emphasized that Korea is in an exceptional political, national, historical situation as the only divided country on earth after the unification of Germany. For them, it was imperative for Korean culture to resolve the “national contradictions.” Therefore, they accepted postmodernism as a cultural theory of post-industrial society but retained reservations regarding the ‘deconstruction of the subject’ and ‘abandonment of meta-narrative.’ Their principle of Korea’s unique historical, national, and political condition, and the urgent need of the ‘national subject’ for resolving the historical contradictions was also repeated by many commentators of postmodernism and culture, especially who supported Minjung misul as a radical art movement.

Sung Wan-kyung and Shim Gwang-hyun were at the core of the Minjung misul movement by contributing to its theoretical foundations and curatorial activities. Bahc Mo (1957 ∼ 2004, born Bahc Cheolho, later changed his name to Bahc Yiso) was an artist, who actively participated with the debates on postmodernism and Korean contemporary art. After graduating from art school in Korea, he moved to New York, studied at the Pratt Institute, and established Minor Injury, an alternative space for art exhibition in Brooklyn. Bahc helped organize the first exhibition of Minjung misul in the USA, Min Joong Art: A New Cultural Movement from Korea at Artist Space, in New York’s Artists Space in 1988.

These writers – Sung, Shim, and Bahc - were more or less responding to the critic Seo Seong-rok’s criticism against Minjung misul, especially its tenet of realism. Seo Seong-rok was one of the first critics who supported the new generation of artists that emerged in the late 1980s under the rubric of postmodernism.Footnote4 These artists pursued neither the modernist abstraction of Dansaekhwa nor the political activism of Minjung misul as an effort to overcome the impasse in the Korean art world. They organized cohort groups to deal with such wide-ranging issues as contemporary human conditions, ecological concerns, and the mundane everyday reality of consumer society and mass media culture, which had been rejected by both the Dansaekhwa and Minjung misul movements. They utilized a formal vocabulary of mixed-media installation, and Seo explained their thematic and stylistic experiments using the framework of “pluralism (dawon jui)” as the crucial tenet of postmodern culture (). He argued that this new tendency could resolve the deadlock caused by the dominance of Dansaekhwa in Korean modern art. Seo acknowledged the suppressive tendencies of modernism, but he also vehemently opposed Minjung misul’s increasingly dogmatic and partisan adherence to realism and its anachronistic concept of class conflict. He denounced Minjung misul as a “ferocious realism” that was unable to reflect the present reality, but only to be “hysterical and aggressive.” Seo’s criticisms of Minjung misul ignited a collective response from the leftist artists and critics. The point of tension for them resided in postmodernism’s repression of the realist commitments that had been essential to defending Minjung misul’s social values. It is unfortunate that Seo has firmly rejected to publish his earlier polemical essays in any form of publication.

Figure 1 Kim Chandong, Meta Object: Myth, 1986, Korean paper and others, 120 x 80 cm © Kim Chandong. Image courtesy of Kim Chandong.

Shim Gwanghyun also wrote this essay in response to Seongrok Seo’s criticism against Minjung misul and its tenet of social realism. I chose Shim’s text as an example of the reaction of the Minjung misul sector because he more clearly responds to Seo’s points of criticism, and thereby provides a contextual framework of Minjung misul in responding to such criticism.

Shim first warns against the danger of postmodernism from the West, especially its call for deconstruction of subject and denial of social totality, which can result in anarchism, extreme individualism, and even nihilism. He stresses that the radical art movements, prominently Minjung misul of the 1980s, regained the avant-garde art’s subversive potential that had been abandoned by Korean modernism. The “realism,” he argues, is the achievement of Minjung misul, in the sense that it reflects the sociohistorical reality of Korea and actively attempts to overcome the “national conflicts.” Shim defends social realism by arguing that the questions of forms, styles, and medium of art remained secondary to the grand principle of the independent development of national art of the people for Minjung misul sector. He criticizes Seo’s argument that Korean postmodern art of the 1980s is in reality only art as commodity of the “neutralists” of ideology, or worse, “opportunists.”

Yun Jin-seop is a curator and critic, who supported Korean modernism and promoted the Dansaekhwa movement towards its global success after 2000. In the mid-1980s, Yun paid attention to the new generation artists groups, such as Golden Apple (Hwangeum Sagwa), Museum (Myujium), and Sunday Seoul (Sseondei Seoul), which were soon to be dubbed as ‘New Generation (shin sedae)’ artists, as postmodern art practices (). Now the globally renowned artists, such as Choi Jeong-hwa and Lee Bul, first participated with these group exhibitions. In evaluating their works, Yun emphasized the prevalent sense of defeatism, emptiness, anxiety, obscenity, and irrationality, which were registered in forms of fragmented statements and kitschy aesthetics. These formal characteristics and their innate resistance to interpretation were soon to become the crucial elements in appraising Korean ‘postmodern’ art of the 1990s.

Figure 2 Group Museum’s exhibition, Sunday Seoul (Sonahmoo Gallery, August 10 - August 20, 1990), Installation scene. © Kim Sung-bae. Image courtesy of Kim Sung-bae.

Yun understood postmodernism as the cultural symptom of the late capitalist, post-industrial society, which he believed was the condition of Korea in the 1980s. This was partially supported by Jeong and Kang’s introduction to postmodernism. For Yun, even Minjung misul was an outcome of the postmodern society, in which the ever-thriving entertainment business, information network, consumer culture, and the principles of mass production and mass consumption were infiltrating the everyday life of common people. While the avant-garde art movements of minimalism, conceptualism, and Neo-Dada in the Western world failed through co-optation by the art market, Yun argued, the Korean de-modernization or postmodern art movements still maintained their subversive potential of avant-garde, because they were not commercialised and commodified yet.

Since the mid-1980s, the critic Lee Jae-eon also promoted the new generation artists of figurative paintings and mixed media installations along with Seo Seong-rok. Unlike Seo, however, Lee saw their experiments as a symptom of late modernism rather than postmodernism. In this vein, he argued that both new figurative paintings and Minjung misul are anti-modernism or de-modernization that attempted to rebel against the stronghold of modernism in the Korean art world. For the modernization in every sector of Korean society is intricately entangled with struggles in regard to Westernization and the anxieties of colonialism. Lee pointed out, therefore, that even though Dansaekhwa was widely acknowledged as the ‘quintessentially Korean’ art of spirituality and meditation, this ‘Korean’ aesthetics was first discursively constructed by Japanese scholars from the colonial era and secondly formulated by mimicking the Western style of abstraction. He believed that the decline of Korean modernism, which refers to the criticism against Dansaekhwa in the 1980s, was due to its dependence on the foreign discourses and the superficial reception of the Western modernism.

Lee was cautious, however, in readily adapting the term ‘postmodernism’ in defining the rebellions against Dansaekhwa. He uses ‘anti-modernism (ban-modeon)’ and ‘de-modern (tal-modeon)’ as the periodical attitude of the 1980s’ art in general, which incorporates both Minjung misul, the new figurative paintings, and mixed media installations. Regardless of the two sectors’ opposite political or even partisan tendencies, Lee found commonalities in their attempt to subvert the institutionalized power of Dansaekhwa and diversify the artistic styles and subject matters. On the one hand, he valorised Minjung misul’s promotion of realism as a way to reject Dansaekhwa’s absolute principles of monochrome canvas. On the other hand, he supported the newly emerged expressive paintings and installations, because they expanded the subject matters into the current issues of everyday life and overcame the previously exclusivist tendencies of partisan politics. Though unclear and inconclusive, Lee’s work reveals an effort of a conservative critic to analyse the current artistic changes and provide a vision for the future.

Bahc Mo was particularly concerned with art’s capacity for sociopolitical intervention amid political violence, which eventually led him to critically support Minjung misul. In particular, Bahc served as a catalyst for exporting Minjung misul out of Korea and importing postmodern theory back to Korea. At the same time, as an alien in New York, Bahc pursued the self-reflexive practices of representation often utilized by cultural minorities in the U.S. and the Western world more broadly. Responding to postmodernism as an oppositional theory, he searched for counter-narratives to destabilize hegemonic views of the nation during the early stages of globalization and embraced postmodernism’s potential for promoting politically motivated art from a Third World country. Standing at the intersection of the two worlds, Bahc created a passage from ‘Third Wordist cultural nationalism’ to postmodernism in the middle of the open site of political and ideological contestation in Korea at the turn of the decade. While he reflected on Korean identity and struggled to register its specificity in the mainstream art world of the West, he simultaneously desired to undermine the dominant rhetoric of tradition, patriotism, and cultural nationalism in his home country.

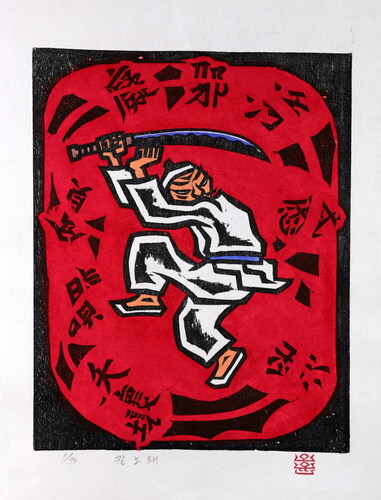

Since its emergence in the late 1970s, Minjung misul had rigorously promoted ‘tradition’ as its artistic origin and the rediscovery of tradition became a particularly pressing concern. The protagonists of Minjung misul saw Dansaekhwa’s aesthetics of ‘Korean spirituality’ and its promotion of transcendence through contemplative gestures as a symptom of political apathy, or worse, subservience to the military dictatorship. Standing in opposition to Dansaekhwa’s elite intellectualism, Minjung artists attempted to revitalize folkloric traditions, such as woodcut printing, decorative crafts, murals and banner paintings, shamanistic rituals, and talchum (a form of traditional mask dance theater). Their commitment to the traditions of the common people was part of a broader cultural movement of the 1980s, when leftist intellectuals and political activists denounced the particular brand of tradition valorized by state-sponsored institutions as the residue of reactionary feudalism. Minjung misul particularly embraced the ‘peasant’ as the genuine subjectivity of the Koreans, which they endorsed as the quintessential agent of a healthy national subject (). The leftists’ preoccupation with rural communities reflected their desire to distance themselves from the contemporary context of a highly industrialized, capitalist, urban society. The peasant and its collective formation of the Minjung was promoted as a counter hegemonic cultural identity that offered the resilient, utopian, and nativist vision of Korean society, as if it once ‘really’ was.Footnote5

Figure 3 Oh Yoon, Sword Song, 1985, Woocut print on cotton, 47 x 31.6 cm © Oh Young-Ah. Image courtesy of Oh Young-Ah.

Sung Wan-kyung is a founding member and a leading critic of the Minjung art collective, Reality and Utterance (Hyeongshilgwa Bareon). As a prolific writer, critic, and curator, Sung has published numerous articles and books on the developments of political discourse in South Korean arts, and first introduced Minjung misul to a foreign audience by participating with the organization of Minjung Art exhibition (Artist Space in New York, 1988) and Global Conceptualism (Queens Museum of Art, 1999). As shown in the round table discussion of Sung, Shim, and Jeong, along with Bahc, they tried to overcome the conflict—postmodern deconstruction versus the endorsement of a nostalgic, nationalist agenda—by insisting on Korea’s unique historical condition as a “third world nation.”Footnote6 Jung Jichang, an expert in Brechtian literature and theatre, has actively supported and promoted Korean traditional performances, such as Madangguk and Minjokguk.

They argued that Korea’s history of colonization, the presence of class struggles under state-driven economic growth, and the national division of North and South made postmodern skepticism toward grand-narratives unacceptable. This argument is also found in Jeong and Kang’s introduction to postmodernism. For these critics, postmodernism’s deconstructive strategy of decentered and fragmented subjectivities would efficiently screen out any appeal to identity, which serves as an integral component of self-realization and cultural emancipation for the third world in the post-colonial era. They claimed that the engagement with the traditional criteria of truth, ethical value, and political principle should not be easily deflected by embracing the Anglo-American hegemony of discourse. This strategic justification of Minjung misul by means of concepts such as class, humanism, subjectivity, grand narratives, historicism, and Otherness was highly acclaimed by leftist critics.

However, the almost compulsive obsession with such concerns of unique cultural identity and specifically Korean condition began to subside rapidly in later years of the 1990s. Until then, concepts related to ethnicity, self-formation, originality, identity, and subjectivity have been persistently discussed by critics irrespective of the differences in their political views, whether they are conservative or progressive. On the one hand, the preoccupation with a distinct identity was being challenged as a form of essentialism or antagonistic nationalism, but the pursuit of universality was also identified with cultural obsequiousness. However, the controversy surrounding “Koreanness” has withered since the mid-90s as a result of the Korean art scene’s assessment that it could finally participate in the contemporaneity of global discourses. ‘The contemporary’ revealed through institutionalized exhibitions, new media, and commonplace materials is bound to be blamed for the depoliticization and dehistoricization of contemporary art, yet this was also absorbed as one of its essential characteristics.

Notes

1 For an extensive study of Dansaekhwa, see Joan Kee, Contemporary South Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). “Tansaekhwa” is the old style of romanization for Dansaekhwa. Also see Yisoon Kim, “Dansaekhwa: Aesthetics of Korean Abstract Painting,” in Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation, Interaction, ed. Yeonshim Chung, Sunjung Kim, Kimberly Chung, and Keith B. Wagner (New York: Phaidon, 2020), 74–95.

2 For a discussion of South Korea’s political circumstance, where the radical art movement was emerged, see Chunghoon Shin, “Reality and Utterance: In and Against Minjung Art,” in Korean Art from 1953, 97–115; Namhee Lee, The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007).

3 For a discussion of the advent of postmodernism and its artistic practices, see Jung-Ah Woo, “Contemporaneity of Korean Contemporary Art,” in Interpreting Modernism in Korean Art: Fluidity and Fragmentation, ed. Kyunghee Pyun and Jung-Ah Woo (New York: Routledge, 2021), 179–94.

4 Seo Seong-rok, “Culture and Criticism in Revolutionary Era [Byeonhyeokgiui munhwawa bipyeong],” Korean Art and Postmodernism [ Hangung misulgwa poseuteumodeonijeum] (Seoul: Mijinsa Publishing, 1992), 140–56. Originally published in Gana Art (May/June 1991).

5 Tobias Lehmann, “Minjung Art Reconsidered: Art as a Means of Resistance,” Trans-action v. 84 (January 19, 2010), 73–90.

6 “South Korea as Social Space: Fredric Jameson Interviewed by Paik Nak-Chung, Seoul, 28 October 1989,” in Global/Local: Cultural Prouction and the Transnational Imaginary, ed. Winmal Dissanayake and Rob Wilson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996).