Abstract

Wool consumption is at its lowest since the 1950s: a 2021 Textile Exchange report states that wool accounts for only 1% of the world’s global fibre market. Despite the low uptake of wool, an interest in natural fibres has recently emerged due to the increased awareness of textile waste causing environmental pollution and loss of biodiversity as the result of a linear and delocalised economy. The aim of this paper is to identify the type of content used by global wool stakeholders to promote wool on social media (Instagram) and how it interacts with contemporary issues in sustainability. An ensuing question is whether the narrative emerging is supporting the expansion of wool consumption. A mixed method was used to gather data about the marketing of wool on Instagram using authoritative national and international wool stakeholders such as the Australian Wool Innovation, Woolmark, Campaign for Wool, British Wool, the International Wool Textile Organisation and New Zealand Merino Co. This study provides a novel account of the interplay between wool, as a primary industry product, and fashion and how their intersections generate content, representation, and ideas on digital media. The study found that wool is presented to consumers as the fibre of choice. To various degrees, all six stakeholders support a sustainability narrative based on the intrinsic qualities of wool as a natural fibre, from its biodegradability to its ability to recycle atmospheric carbon. Material qualities are represented through images and texts referring to wool’s softness, warmth and its versatility as high-performance clothing for a variety of uses, and as an insulating material. Images of sheep, lambs and ewes are posted to create emotional responses toward wool.

Introduction

Wool is simultaneously a primary industry with its industrial processes of husbandry management and transformation of the fibre, and a cultural industry with economic and social implications. The main final products of wool transformation are yarn and textile, objects that are then designed into fashion following immaterial elements such as trends in colour, patterns and styles. Wool’s duality between form and matter, related to its existence in apparently separate realms, brings to the fore the concept of materiality as an indicator of wool’s continuous processes of transformation that bridges the two worlds of agriculture and that of fashion (Ferrero-Regis Citation2020). Wool qualities are transferred to the finished garment through design, marketing and promotion. In many economies where the wool trade was the primary source of GDP, like in Australia until the 1950s, wool was also inseparable from branding and promoting national identity and local fashion industries (Ferrero-Regis Citation2020).

As an agricultural product, wool has always been subject to price fluctuation due to abundance or scarcity of production depending on climate conditions. In Australia, wool production, price and marketing have also often been subject to the interference of national politics (Massy Citation2011). The competition of cheap synthetic fibres, consumer preferences, devaluation in wool prices, stockpiling, fibre quality instability, ethical issues concerned with the practice of mulesing, and a decline in international demand led to the progressive decline of the global wool trade between the 1960s and 1990s. Today, one million tons of wool are produced every year, which still makes it the most used animal fibre in the world. However, wool consumption is at its lowest, accounting for only 1% of the world’s global fibre market, against 24.4% of cotton and 62% of synthetic fibres dominated by polyester (Textile Exchange Citation2019). Within this context, Australia remains the largest producer and exporter of superfine and fine Merino wool for fine apparel, with around 345 million kilograms of wool yearly, with China, Russia, New Zealand, Argentina, South Africa, the United Kingdom and Uruguay following (Woolmark Citation2021a).

An interest in natural fibres has recently emerged thanks to increased awareness of the threat of textile waste causing environmental pollution and loss of biodiversity as the result of a linear economy. Anxieties about the environment have been amplified by mainstream media, which have focussed global attention on the relationship between climate emergency and the destructive force of human activity.

The study of textiles has broad implications within fashion marketing (McCormick et al. Citation2014), and even more so within a framework of sustainable marketing. Circularity, heralded as the implementation system of sustainability in fashion, starts from the fibre. The recent report Synthetics Anonymous from the not-for-profit organisation Changing Markets Foundation (Citation2021) has highlighted fashion’s dependence on recycled polyester, which is today reported by many brands as a sustainable choice. Less than 1% of synthetic fibre used to produce clothing is recycled into textile, and both the Synthetics Anonymous report (Citation2021) and Cernansky (Citation2020) point out that recycled plastic exacerbates the problem of microplastic through continuous production of plastic bottles. Sustainability claims based on the use of textiles from recycled plastic obscures sustainability efforts in fashion and mislead the consumer. These claims often result in green washing, and sustain the unsustainable (Blüdhorn Citation2011). One of the findings of this project reveals that the problem of microplastic in the oceans is the only open reference to sustainability in wool promotion on Instagram accounts.

The aim of this paper is to identify what type of textual content and images global wool stakeholders use to promote wool on social media (Instagram), and how it interacts with contemporary issues in sustainability. The study does not set out to investigate or evaluate market response to wool stakeholders’ marketing on social media. Instead, it considers to what extent the narrative/s emerging support people’s engagement with wool and thus, speculatively, the expansion of wool consumption. Limitations of this research are dictated by its scope. First, the collection is limited to two Winter months in the Northern hemisphere. This gives a skewed and traditional view of the use of wool (i.e. wool is only a fibre for a cold climate). However, at the same time, the very fact that wool is used predominantly in cold climates for clothing offers the opportunity to see people’s engagement with natural fibres for fashion. Second, coding was done manually, and although it was cross-checked and moderated, interpretation errors are inevitable. To address this limitation, analytical digital tools could be employed. Third, the study sets out to addresses only wool industry stakeholders. Community Instagram accounts, such as @woolandthegang, have a substantially high number of followers (486,000 at December 21, 2021), likes and comments compared to industry accounts, and would warrant a different study of narratives created by wool stakeholders and those created by community accounts.

Literature Review

Fashion sustainability

The fashion industry is one of the worst polluters in the world, and as such it has inevitably been at the centre of debates around unsustainable and unjust practices, especially production of pre- and post-consumer textile waste ending in landfills, and labour exploitation in the Global South. The paradox is that “despite increased awareness about environmental unsustainability” (Manieson and Ferrero-Regis Citation2022, 3), fashion consumption is increasing, with consumers buying 60% more clothes than 15 years ago (Changing Markets Foundation Citation2021), with each clothing item kept half the time and discarded in less than a year, sending 85% of textile waste to landfill (Ellen MacArthur Foundation Citation2017; UNECE Citation2018). This growth is generated by a constant desire for newness, driven in turn by macro and micro trends or fads. The fast fashion business model drives overconsumption and consequently also textile waste. This model has created a new paradigm for fashion, revolutionising and changing the fashion industry in the last 20 years. Barnes and Lea-Greenwood (Citation2006) argue that fast fashion is a consumer-driven strategy by big fashion players such as H&M and Zara to respond quickly to fashion demand. The rapid spread of digital media and social media platforms have supported the rapid rise of fast fashion responding to and creating micro-trends and fads, with the subsequent development of digital marketing and retail, and online promotion strategies to develop brand trust.

Within this context, the model of circular economy (CE) has grown exponentially, becoming eventually the enabler of sustainability (Ellen MacArthur Foundation Citation2017). Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert (Citation2017) define CE as based on the replacement of the end-of-life concept with “reducing, alternatively reusing, recycling, and recovering materials in production/distribution and consumption processes” (127). Circular economy is predicated on zero-waste and continuous growth (see for example EC’s policies in 2014 – Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Programme for EUROPE – and in 2015, Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy). Critics of this type of have-it-all environmentalism, where overproduction and overconsumption continue to be justified in order to satisfy market growth and consumer satisfaction, argue that this approach is depoliticising the more complex discourse about sustainability (Valenzuela and Böhm Citation2017).

Given the focus of CE on waste production, much of the research focusses on supply chains and environmental impact of textile production. Three categories attract research and development, investment and policy: pollutants, CO2 emissions and consumption of water and energy (Wheeler Citation2019). Textile production requires many steps along a lengthy supply chain. To approach such a complex process, the fashion industry uses indexes that can measure fibres’ environmental impact. The most common was the Higg Index, developed by the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC), and recently suspended following critiques about its bias toward synthetic materials levelled by the Norwegian Consumer Authority (Deeley Citation2022). In the Higg Index, fibres of animal origin were the most penalised in comparison to synthetic fibres because the Index omitted the product’s end of life, which makes natural fibres less impactful, whereas synthetic fibres don’t close the loop with cradle-to-cradle disposal. On the contrary, in the Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) developed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, wool has the highest score as a renewable fibre. Thus Laitala, Klepp, and Henry (Citation2018) and Wiedemann et al. (Citation2020) argue that ratings must take into consideration the lifespan of a textile product, including the use phase. Wool requires less washing, and lower temperatures; in addition, wool garments tend to be passed on or resold, unlike garments of different fibres, thus they have higher potential for reuse and sustainable disposal.

Wool

As a natural fibre, biochemical, technological and agricultural scholarly approaches to wool dominates. They are aimed at understanding and improving the natural properties of wool (Laitala, Klepp, and Henry Citation2018), and how wool’s chemical structures can affect design for textiles (Mogahzy Citation2009). Because of the nexus between wool and animal and land improvement, research is also focussed on animal welfare, environmental impact of husbandry and climate change, with focus on Australia, New Zealand and China (Harle et al. Citation2007). Australian wool has been subject to constant critique by the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) – “the largest animal rights organization in the world” (www.peta.org/about-peta/) – for farmers’ persistent use of mulesing practices in the treatment of flystrike. In the fashion industry, the use of animals “hinges on the industrialization of exploitation” (Sorensen Citation2011), and is connected to other industries, for example, food (Segre-Reinach Citation2022). Animals are actors in the production of fashion, albeit without the ability to give consent, thus their rights must be considered within the fashion ethical framework. Often, the term ecofashion could indicate greenwashing because of the treatment of animals involved in the supply chain (Thomas Citation2008). Tracing the provenance of a fashion item, and therefore including the fibre’s source, has increased the focus of sustainability on ethics, moving from the environment (Thomas Citation2008). This is an important consideration when analysing social media messages of wool stakeholders. In fact, the debate on wool is highly contentious because as a full circle fibre it returns carbon to the soil, and it uses 70% less water than cotton (Woolmark Citation2021b). However, wool’s environmental impact through land clearing, animal feed and water contamination (PETA Citation2022), and because of animal treatment in non-organic farms, wool makes a controversial fibre (Farley, Hill, and Hill Citation2015).

The life cycle assessment (LCA) of wool emphasises laundering in a report commissioned by the AWI in 2017 (Laitala, Klepp, and Henry Citation2017); on farm LCA in three Australian regions (Wiedemann et al. Citation2016); and the environmental impact of a 300 grams wool jumper, including end-of-life (Wiedemann et al. Citation2020). The most comprehensive examination of the wool LCA to date remains in Farrer’s (Citation2000) doctoral thesis, where the LC is evaluated from cradle to grave with a focus on environmental and social cost of producing a wool jumper. A different approach to LCA is in Testa et al. (Citation2017), who examine the way in which SMEs can respond to pressures for the adoption of environmental practices along the entire LCA. Testa et al. (Citation2017) explore the initiative Cardato Recycled led by the Prato Chamber of Commerce in 2014, whose goal was to promote Prato’s recycled wool as a trademark. In Prato, post-consumer wool has been recycled for over 150 years with a mechanical process that allows the fibre to manufacture quality yarns and fabrics that are used in fashion. This historical practice and know-how are now a great lever to demonstrate the circularity of wool compared to other fibres, both natural and synthetic. A different approach to wool recycling in a context of post-consumer waste, and the challenge that blends of natural and artificial fibres represent in recycling textiles, is to be found in Navone et al. (Citation2020), which contributes to the extant literature about chemical fibre separation and treatment of wool blends.

Most of the literature regarding wool marketing, the economics of wool exchange on the international market, and policy are of historical and localised nature (Abbott Citation1998; Abbott and Merrett Citation2019; Merrett and Ville Citation2012; Richardson Citation2001). Wool textile industry supply chain management (SCM) and supply chain systems studies have been attracting much attention in the last 20 years. Champion and Ferne’s study (2001) is an early attempt that suggests holistic changes in the wool industry, whose communication of value was at the time still limited to the auction stage. Champion and Ferne (Citation2001) emphasise the need for Australian and New Zealand wool industry to adopt widespread SCM principles to communicate wool values beyond the farm. Mitchell, Smith, and Dana (Citation2009) explore the history of New Zealand merino wool and its marketing, with a focus on innovation and change in the industry.

In the world of fashion, traceability and certifications are becoming increasingly important. Various studies (Farley, Hill, and Hill Citation2015; Niinimäki et al. Citation2020) show that the fibre production phase has the greatest environmental and social impact related to farming practices, gas emissions and pesticides. Certifications are used to guarantee compliance with a shared standard along the fibre production chain, from its origin to the final product. Especially for fibres, certifications are very important as brands increasingly address the percentage of materials they use in their collections in their sustainability reports, determining measurable objectives for improving performance. Thus, transparency in the origin and traceability of wool is an emerging focus for the wool industry. Peterson, Hustvedt, and Chen (Citation2012) examine the relationship between origin certification and consumers’ disposition to pay for certified organic wool apparel in the United States, concluding that consumers value the most environmental sustainability and animal welfare compared to organic certification. These findings are significant to our research, as Peterson, Hustvedt, and Chen (Citation2012) conclude that wool marketing should take into consideration targeted audiences, in our case, engage with a younger audience on social media, if the wool industry wants to expand wool consumption.

Fashion on social media

The rise of social media has enabled an intense circulation of images, and thus visual knowledge has become increasingly central to our cultural exchanges. Social media sites (SMSs) have transformed how fashion brands create marketing strategies to engage global consumers with visual storytelling and two-way communication, which develops viewers’ engagement and participation (Serafinelli Citation2018). The mediatisation of fashion on Instagram (Rocamora Citation2017) extends from product to influencers and their collaboration with brands, fashion shows, backstage presentations, short stories and events (Milanesi, Kyrdoda, and Runfola Citation2022). Naturally, the common focus of Instagram and fashion on fast, new and trendy has attracted scholars’ attention, extending to the examination of sustainable fashion narratives on Instagram (Lee and Weder Citation2021; Milanesi, Kyrdoda, and Runfola Citation2022). Investigations have focussed mainly on brands’ storytelling about how they approach sustainability, or activism. Less attention has been paid to how fibre stakeholders are attempting to influence followers and consumers. This paper seeks to address this gap.

Instagram is the sixth most used social network with 1,158 billion active users as of October 2020 (Statista Citation2020). The platform is predominantly used by young consumers, with people between 18 and 34 as the most frequent users (Statista Citation2021a), and a majority of male users (Statista Citation2021b). Like other SMSs, tagging and hashtags, images and text invite in other users or brands, widening the circle of participants in anyone’s post and creating a community with the potential of increasing marketing targets. Instagram popularity rests on its user demographic of young people. Therefore, the chief aim for wool stakeholders on this platform should be to build a narrative that appeals to millennials and Gen Z.Footnote1 One of the objectives of this article is also to identify the assumed audience for wool promotion through posting and verify if the narrative constructed around sustainability key themes is clear and accessible. Kusumasondjaja (Citation2019) explains that “Instagram content communicating emotional aspects of the luxury brand item using expressive aesthetics is likely to be more relevant than listing their technical specifications” (18). In fact, technical and technological aspects of production processes are completely missing from all the accounts surveyed but one (CfW). The chief type of image is that of lambs, sheep and flocks, confirmed in the number of posts that have been collected during the period surveyed (see ). Our first hypothesis is that animals are used to communicate emotional responses in Instagram users.

Methodology

The purpose of this study is to identify the key themes that global wool stakeholders draw on to promote wool on the SM platform Instagram and ascertain followers’ response. In doing so, the research provides a rare account of how wool promotion interacts with contemporary issues in sustainability to generate a narrative for the expansion of wool consumption. The research is based on a mixed method made of a quantitative analysis of recurrent key words in Instagram posts by six international wool industry stakeholders, and a qualitative content and visual analysis of the images accompanying the written texts. Visual content analysis enables the interpretation of the codes that make up an image, combined with its wider context (Rose Citation2001). However, the frequencies of visual elements in images can risk returning descriptive results (Rose Citation2001). Given the complex and expressive visual and textual presentation of meaning on the social media, this project has employed semiotics to analyse the broader system in which wool images exist as the two methods are not mutually exclusive. Literature review and grey literature allow for verification of primary data (Yin Citation2003). Followers’ engagement through the number of “likes” has also informed aspects of the research.

Given wool inhabits the two worlds of material and immaterial, this project considers Roland Barthes’ (Citation1990) foundational work about fashion as a layered system of material and immaterial things that form a unified structure. For Barthes (Citation1990), a system of social relations, networks and activities comes together to make fashion as opposed to clothing. As Rocamora (Citation2015) notes, Barthes summed up the essential function of the fashion magazine as “a machine that makes Fashion” (in Rocamora Citation2015, 132). Despite the obvious differences between print and digital media in their mode of production, delivery and consumption, Instagram has rapidly developed to be a machine that “makes” fashion, or does fashion (Rocamora Citation2017, 509). The way in which image and text play out in Instagram, often jarring, adds a different layer to Barthes’ semiotic work, who chose the “written system” of fashion over that of the image (Citation1990, x). We found that the properties of the fibre emerge in the stakeholders’ posts in Instagram, but they are visualised through a variety of images that are not depicting the fibre. Central to the research aims of this project is the understanding of how the represented clothing, the “image clothing” and the “written clothing” (Barthes Citation1990), conflate and interact on social media, creating a marketing and promotional narrative for wool.

Methods

The collection methods employed in this research consisted of extracting manually Instagram posts from six major wool stakeholders, the Australian Wool Innovation (AWI), Woolmark, Campaign for Wool (CfW), British Wool (BW), the International Wool Textile Organisation (IWTO) and New Zealand Merino Co (NZMCo). They were chosen for their varied profile: the AWI represents Australian wool farmers, overseeing research and development along the supply chain of the world’s leaders in the production of fine apparel wool; Woolmark is the marketing subsidiary of the AWI, and is the trademark representing and marketing the certification of Pure Merino wool; CfW has been actively promoting wool since 2010 with a global cachet built on its famous patron, the then HRH Prince Charles; BW has been chosen as a counterpart of the AWI; the IWTO is the global representative of the wool trade; NZMCo is an integrated company representing New Zealand Merino wool globally. Data collection started on December 1, 2020 and ended on January 31, 2021.

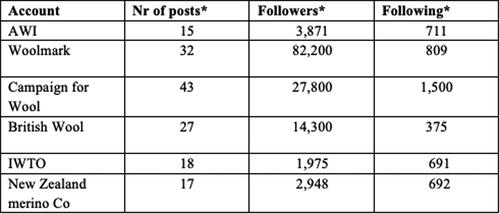

Using qualitative software NVivo we generated and manually assigned codes to the data files based on initial key codes collected and triangulated with previous research projects findings from field research conducted in Australia with wool growers, scholarly literature on wool, and a similar pilot project about three wool stakeholders’ storytelling on Instagram conducted by the research team. From the initial key words High performance, Craft, Merino sheep, Laundering, Shearing, Australia/n,Footnote2 Designer, Fashion, Farming, Environment, Lamb, and Sustainability, it became apparent that some of the initial key words were in fact child codes, and other highly recurrent key words needed to be added. Data collection provided a snapshot of the six stakeholders’ presence on Instagram (see ). The use of NVivo facilitated the integrated and rich qualitative and quantitative analysis between images and texts in the six chosen global wool stakeholders.

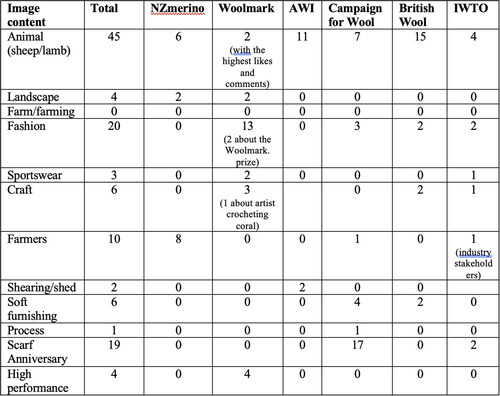

Figure 2 Image content of the six accounts. Posts with illustrations or single random images, such as Christmas bells or composite images, were not counted.

Posts were analysed inductively and qualitatively in a back-and-forth process to facilitate an open exploration of the themes in the written post and the image content accompanying them. Following De Souza and Ferris (Citation2015), the categories that contributed to data collection and analysis were modified to suit the type of accounts (upstream supply chain instead of brands). We noted:

The total number of posts made by each stakeholder surveyed in the period;

The total number of followers of each stakeholder;

The type of content that each stakeholder posted, in images and written text;

The type of engagement and feedback of followers was also noted.

Findings and Discussion

The findings of this study propose a framework for understanding narratives and storytelling about how the wool industry promotes the sustainability of the fibre and related products on social media. We suggest that the communication of sustainability exists at the intersection of different paradigmatic levels: the depiction of animals to invite emotional response; the inherent physical qualities of wool to stimulate choice; and the aesthetic to mediate ideas about culture. These results are generated by the interplay between image and text, where the image does not necessarily depict the key textual code (see ).

Given Instagram’s communication multimodality, images were easily catalogued manually. Barthes (Citation1990) argued that the written text follows a rigid system of language, whereas the image is direct and is interpreted by the viewer; in other words, the image’s meaning is not fixed. Elements that anchor the image and contribute to the way in which the image is read are the space in which the image exists, the kind of objects depicted and the aesthetic references in the image. In Instagram, images are attention-grabbing and anchor the text. The dominant type of image is the portrayal of animals, either lambs or flocks of sheep with 45 images across the six accounts (see ). Two of these images posted on the Woolmark account received the highest number of likes of all accounts we surveyed. One of the images depicts two small cuddling twin lambs sleeping in the sun and received 12,489 likes (see 5 January 2021) (see ); the other portraying a ewe peering from behind a tree received 7,340 likes (22 December 2020). The text accompanying both images was minimal, with no keywords related to wool other than “lamb” or “ewe.” In comparison, two fashion images with most likes received 4,191 and 3,497 likes.

It is clear that “seductive” (Segre-Reinach Citation2022) animal images are used to induce an emotional response, especially considering that a post depicting Bella Hadid (a celebrity fashion model) wearing a wool jumper only received 343 likes (19 January 2021), with a text that read generically “a winning combo” referring to both the model and the wool jumper. After these preliminary observations, we turn to a close examination of the three themes we have singled out and ask the question: How do the main wool industry stakeholders represent narratives of sustainability?

Animal welfare

The main finding confirms our hypothesis that posts related to animals are predominant and they are meant to stimulate emotional response. shows that the portrayal of animals, whether in a flock or individually, is a common feature in all accounts. Many of these images depict a natural and pristine landscape, reinforced by words such as “These (#) sheep are fully equipped to handle whatever the winter throws at them.” British Wool (BW) has the highest number of images of sheep (15) as they are connected to BW’s weekly selection #SheepOfTheWeek (see ). BW also uses flocks of sheep photographed in different environments: in snow, on the beach and in wild green landscapes. Of all wool accounts surveyed in this research, BW posts the most varied selection of images related to animals and the fibre, perhaps motivated by capturing the Britishness of British wool.

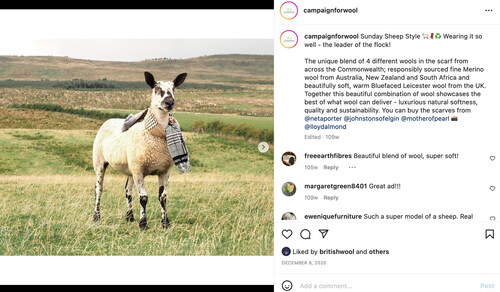

There are two types of imagery of animals. One type shows young lambs or ewes in close-ups, accompanied by adjectives like “cute, adorable” (CfW, January 20, 2021) (see ). The second type shows flocks of sheep, and they are intended to tap into the more general relationship between animals grazing in a healthy and wild environment, also synonymous with a pristine landscape, and wool as a pure and clean fibre. Within this group, the language of emotions is well represented with an image of a mid-shot of a woman bending over a “poddy” kissing it, with the caption reading “Lily, a former poddy lamb, saying hello to an old friend … poddies never forget their humans!” (AWI, December 18, 2020), which establishes an explicit relationship between farmers and sheep. Many other images depict flocks of sheep with reference to healthy farming, regenerative farming, and new generations of farmers. This messaging, mainly on the AWI account, encourages not only an emotional response to wool, but especially a romantic view of producing wool, and of Australian farmers’ efforts in adopting sustainable practices. It is of particular interest because in the analysis of the stakeholders profiles covered by this survey, only one reference is made to the welfare of the sheep (AWI, January 27, 2021), but it is presented to farmers via the promotion of a webinar that promises to explain how to manage flystrike. No information is given on mulesing, even to explain the reasons behind the adoption of this practice. Yet the issue is becoming crucial from a commercial point of view. According to data updated to June 2021 (Textile Exchange Citation2021, 41), 203 brands have adopted a mulesing-free policy. There are various forms of mulesing: steining refers to the removal of skin around the tail through freezing with the application of liquid nitrogen. This is a crucial point because the Australian Wool Exchange (AWEX) includes removing the skin from the lamb’stail with shears. This means that the wool sold as non-mulesed, according to AWEX’s definition, could still have been shorn from sheep treated with freezing mulesing.Footnote3 It is not possible to obtain any certification of wool if it is not certified that the flock has not been subjected to mulesing. According to the 2021 Textile Exchange report, in Australia, 57% of wool is mulesed, 26% is high mulesing risk and 18% is freeze mulesing risk (Textile Exchange Citation2021, 41). We conclude that the reason for not including a conversation about mulesing is that the stakeholders surveyed are trying to sell a wholesome and ethical view of wool. The conversation about mulesing occurring on social media is conducted by activist groups such as PETA. For many years, the organisation has led the battle against the use of fur in fashion, and for some years has been working on the theme of animal fibres to ensure fair treatment for animals on farms. Their campaigns have a strong communicative impact and can involve audiences from all over the world, but are beyond the scope of this article’s analysis.

Physical properties of wool – material values

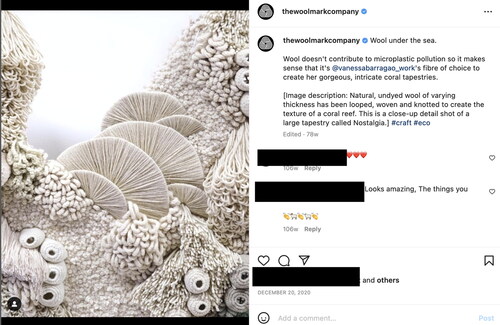

Wool’s biodegradable and recyclable properties, its warmth, softness, durability, breathability, comfort and strength are presented as strong features of the fibre. The biodegradable quality of Merino is pitched against microplastic waste generated by polyester flowing into oceans, and form part of the narrative about sustainability of the fibre. This is emphasised in a text accompanying an image that depicts tridimensional tapestry of coral in a neutral colour (Woolmark, December 20, 2020). The text “Wool doesn’t contribute to microplastic pollution” indicates the connection between the natural fibre and sustainability (see ). The biodegradability of wool is mentioned also in posts about caring for wool, which emphasise that when washed, it does not release microplastic in the water, and in the ocean. These properties are communicated mainly via text (see ), with images depicting clothing or furnishing.

Woolmark is the account with most fashion and clothing posts and is a particularly interesting account as it connects material and immaterial values through the combination of text and image. In a post featuring an image with a pair of pyjamas the text reads “These (hashtag name) ones are made from 100% Merino wool which means they are soft and naturally breathable” (December 15, 2020). The post connects these qualities to Merino wool, the softest and finest wool fibre that is grown by the Merino sheep. Also, Merino wool regulates body temperature, and therefore it is used particularly in sport and outdoor activities. Woolmark’s digital promotion addresses body thermoregulation in four posts that have to do with high performance sport, and outdoor lifestyle. The Luna Rossa’s team competing at the 36th America’s Cup in Auckland (December 3, 2020, and January 22, 2021) appears in two posts. The team, praised for its strength, wore special clothing created in a partnership between Woolmark, Pirelli and Prada. The natural properties of wool are collected in a CfW post that reads “Wool is the ultimate performance fibre; it regulates your body temperature, is odour resistant, durable and comfortable to wear” (January 5, 2021). The post is accompanied by an illustration showing a male wearing a one-piece sportswear while stretching, alluding to the stretching qualities of wool. The post calls for new healthy habits through physical exercise, conflating it with the use of wool.

The insulating properties of wool are recalled in a IWTO post, which promotes wool for pharmaceutical packaging, in connection to Covid vaccines. The post is completed with an image that shows a pile of folded wool sheets for insulation. BW promotes a young couple who have padded their campervan with wool sheets purposely made for insulation (January 5, 2021). The image shows a young woman applying a wool sheet to the camper. Wool as a natural fire retardant is a marginal comment.

Aesthetics – immaterial values

Barthes (Citation1990) highlights the transformative activity of fashion, from the real garment to image to language. The transition from the real garment to the image and then to language delivers simultaneously the iconic message where the real garment, the industrial, the sewn and the represented are entangled. The accounts surveyed in this research seldom show the fibre and its stages of manufacturing, its transformation from fibre to textile, to the designed object. They do not engage with sustainable practices in manufacturing; on the contrary, the process is maintained as opaque and invisible, as it is one of the most complex system compared to other fibres, also because of the geographical dissemination of its many practices. Instead, the finished garment and other images that elicit an emotional response are used to convey physical properties of wool. These images are thus metonymic in that they build a new language to signify wool, its properties and why it should be a fibre of choice. This concept is highlighted by the CfW scarf promotion.

Between December 4 and December 19, 2020, CfW posted images daily (a total of 19) that promoted a limited edition of a scarf designed by Amy Powney to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the founding of CfW (see ). Images alternate between the (then) Prince of Wales (patron of CfW and owner of the Duchy of Cornwall estates), the scarf as finished product, landscape (video), still life of the scarf, weaving of the textile, a video of a model wearing the scarf, a sheep, a video of the (then) Prince of Wales, a mother wearing the scarf and a child, a model wearing the scarf, two composite images of people (including men) wearing the scarf, a child with the scarf, two images of sheep, two images of models wearing the scarf, and finally the manufacturer, Johnstons of Elgin, hugging a sheep. Importantly, this is the only post that notes the origin of the wool blend used in the weaving of the textile, that is four countries of the Commonwealth, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the United Kingdom. These posts reinforce the invisible manufacturing of the scarf as it does not show the means of transport of the fibres, which are associated with pollution, and their sites of processing.

The sequence of images constructs an effective narrative that combines agricultural elements with fashion elements, but limited to the natural origin of the fibre. The (then) Prince of Wales’ involvement in the scarf campaign and his well-known commitment to environmental issues and organic farming add credibility to sustainability. People, planet, sustainability, biodegradability, softness of wool recur in all the texts, either with images of the scarf and models, or of sheep. The relationship between material and immaterial sustainable values of wool is explored in depth, identifying organic farming and natural fibres as fundamental to mobilise a sustainable fashion industry (see ).

A post made on December 5, 2020 shows a stage in wool manufacturing by depicting the weaving of the textile used for the scarf. This image is accompanied by a long text that superficially describes the transformation of the raw fibre into the finished product through 30 different processes. The text also mentions skills, capabilities and craftmanship held for generations at Johnstons of Elgin. The post is effectively a promotion of the manufacturer, but it is important to highlight that it is the only post we found in our research that explores the wool manufacturing process and the skilled labour needed in the making of high-quality products with the finest wool.

Despite this important digital promotion, there remains the question about how the scarf narrative connects with the predominant Instagram demographic of young consumers. All images show expensive interiors, prestige, heritage and royalty (the then Prince of Wales), exclusivity and authenticity which are offered with the coupling of sheep and scarf, with the words “luxurious,” “sustainable,” “softness,” “longevity” and “natural.” As Kusumasondjaja (Citation2019, 16) maintains, “luxury consumption holds intrinsic emotional value,” and sustained storytelling on social media can engage consumers in a deeper way. It is difficult to establish how effective this campaign was as CfW’s “likes” are hidden (the other accounts’ likes were visible). However, it is possible to infer that with the strong presence of older models (men and women), family and royalty the series of posts constructs a narrative directed to an older luxury consumer rather than a millennial. If the goal is to reach a younger age group, to educate younger consumers to choose wool, the goal is not achieved, as the CfW campaign communicates the exclusivity of wool: the scarf is a luxury item, aimed at a particular type of consumer. The style of the images, the messages and texts support this conclusion. The campaign is accompanied by the hashtags #choosewool #makeadifference, however both hashtags are not developed with adequate textual content capable of making them understandable to an audience that needs to appreciate why they should choose wool.

A final point about the conflation of material and immaterial values must be made about the way in which New Zealand engages with the promotion of its Merino wool (see ). In their accounts, NZMCo posts feature mostly images of landscape, with and without sheep. These images are long shots that show the breadth and depth of New Zealand’s wilderness. Some of these images are without sheep, but instead they feature sheep dogs, a metonymic reference to sheep. This digital messaging is aligned with the marketing of New Zealand as 100% Pure, a campaign that has been successful in increasing international tourism to the country and subsequently became a successful branding strategy for the nation. Like other countries, New Zealand wool followed the same development and implosion of the global market that determined the decline of wool as a fibre of choice. For the New Zealand wool industry, it was important to separate generic wool marketing from Merino wool (Mitchell et al. Citation2009), which was a significant factor in the success of the high performance underwear in fine Merino wool, the Icebreaker® brand. The NZMCo account has very minimal textual engagement, and in the period surveyed did not have any posts related to fashion or clothing. It is possible to infer that the account focusses on the quintessential character of the environment as a guarantee for the purity of its wool, and thus adopts a strategy based on traceability of wool origin.

Conclusion

This research set out to investigate and analyse how wool as a primary industry commodity is marketed via different types of accounts from within the global wool industry. The focus was to understand how six global wool stakeholders present narratives of sustainability on Instagram. In this research, we have found that the marketing messages are indirect, subtle and depict mixed content. Given that in our case the Instagram accounts are those of wool industry stakeholders and not brands, we expected that posts should aim at establishing a dialogue and creating a conversation with the followers about wool. Key findings have identified that in the period surveyed, the six Instagram accounts have communicated the sustainable narrative through three main visual and verbal strategies: the visual depiction of animals to invite emotional response; the verbal inherent physical qualities of wool to stimulate choice; and aesthetics to mediate fashion and cultural ideas about wool.

Many posts explain why wool is sustainable through the emphasis of wool properties: fineness, biodegradability, durability, comfort, softness, warmth, fire retardancy, insulation. Wool stakeholders use ideas of sustainability mainly through showing its natural, agricultural origin and then through the biodegradable quality of wool, mentioning the lack of microparticles in the ocean, hence the focus is on the consumer care of wool (laundering) and disposal (biodegradable). As a natural fibre, wool is renewable as it decomposes in soil in a short time, returning CO2 to pastures. This is an easy strategy that is readily understandable by a lay consumer. However, the long global value chain of wool, from the production of greasy wool to its end-of-life phase (including second-hand and recycling) remains opaque on Instagram. On the contrary, posts represent material values through handicraft products, clothing and fashion bringing together the different elements that make the totality of the fashion and clothing system (Barthes Citation1990).

There is a disconnect between Instagram audience (a group of people mainly under the age of 35, who pay great attention to aesthetics), and the textual and photographic language chosen in the communication of the analysed accounts. It is a hybrid communication model, which is neither institutional as one would expect from the industry environment, nor cool for fashion enthusiasts. From the analysis of photos and texts, the lack of construction of an identified audience with whom to communicate appears clear. Yet the world of wool is facing major challenges (Farley, Hill, and Hill Citation2015), and the ability to engage with consumers is fundamental. Animal fibres must face a counter-communication also played on Instagram that highlights the negative aspects, the social and environmental impact of production, in an increasingly decisive way. Our recommendation would be for wool stakeholders on Instagram to carry out a serious information campaign on wool, farms, and the production cycle: knowledge is always an excellent method to allow the consumer to make informed choices. The #sheepoftheweek competition will not be enough to allow this fibre to maintain and increase its presence in the market.

Acknowledgements

This project was given ethical clearance by Office of Research, Ethics and Integrity, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Women in Research program at the Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. We would also like to thank Dr Abigail Winter from the Design Lab, QUT, for her kind support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tiziana Ferrero-Regis

Dr Tiziana Ferrero-Regis is Associate Professor in the School of Design at the Queensland University of Technology. Tiziana combines a professional background in the fashion industry (Vogue Italia) with a scholarly background in fashion theory and history, cultural studies, and sustainability. Her research focusses on circular economy in a local context. Tiziana is co-leader of the research group TextileR at QUT. [email protected]

Silvia Gambi

Silvia Gambi is an Italian journalist and an independent researcher specialising in the topic of sustainable fashion. She is the author of a content platform, “Solo Moda Sostenibile,” which consists of a magazine, a podcast and a newsletter. She is specialised in textile recycling and collaborated on the screenplay of the documentary Stracci, produced by Kove, released in November 2021. [email protected]

Notes

1 Millennials and Gen Z refer to two age groups born between 1981 and 1995 (Millennials), and between 1996 and 2012 (Gen Z). Millennials have spent a longer life as adults than Gen Z. Millennials have grown up with technology, but are less globally connected via technology than Gen Z. Gen Z are seen as pragmatic and more committed to social justice. Millennials grew up with brands and remain committed to brands (Raslie Citation2021; Francis and Hoefel Citation2018).

2 Australia is the highest producer of Merino wool and references to the country occurred also in non-Australian Instagram accounts.

3 Mulesing is a practice that is used in farms and consists of the removal of strips of skin around the tail of lambs to avoid flystrike problems. These types of infections spread quickly between animals and can cause great damage to farms. This practice is believed to be painful for animals and some countries, such as New Zealand, have prohibited it. The Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines for Sheep defines mulesing as “The removal of skin from the breech and/or tail of a sheep using mulesing shears” which AWEX adopts (AWEX Citation2020). The completion of the mulesing status of a mob is voluntary and each farmer must comply with the National Wool Declaration of mulesing.

References

- Abbott, Malcolm J. 1998. “Promoting Wool Internationally: The Formation of the International Wool Secretariat.” Australian Economic History Review 38 (3): 258–279. doi:10.1111/1467-8446.00033.

- Abbott, Malcolm J., and D. Merrett. 2019. “Was It Possible to Stabilise the Price of Wool? Organised Wool Marketing 1916 to 1970.” Australian Economic History Review 59 (2): 202–227. doi:10.1111/aehr.12136.

- AWEX (Australian Wool Exchange). 2020. National Wool Declaration Business Rules for Mulesing Status Issue: 5 Update: Monday 11th May 2020. https://www.awex.com.au/media/2064/nwd-v80-release-notes-and-business-rules-for-mulesing-status-issue-5-11th-may-2020.pdf.

- Barnes, Liz, and Gaynor Lea-Greenwood. 2006. “Fast Fashioning the Supply Chain: Shaping the Research Agenda.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 10 (3): 259–271. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/13612020610679259/full/html. doi:10.1108/13612020610679259.

- Barthes, Roland. 1990. The Fashion System. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Blüdhorn, Ingolfur. 2011. “The Politics of Unsustainability: Cop15, Post-Ecologism and the Ecological Paradox.” Organization and Environment 24 (1): 34–53. doi:10.1177/1086026611402008.

- Cernansky, Rachel. 2020. “As Fashion Churns Out More ‘Sustainable’ Goods, Why Is So Much Made from Plastic?” Vogue Business, 5 March. https://www.voguebusiness.com/sustainability/sustainable-goods-why-so-much-made-from-plastic-adidas-stella-mccartney-levis

- Champion, S. C., and A. P. Ferne. 2001. “Alternative Marketing Systems for the Apparel Wool Textile Supply Chain: Filling the Communication Vacuum.” The International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 4 (3): 237–256. doi:10.1016/S1096-7508(02)00070-8.

- Changing Markets Foundation. 2021. Synthetics Anonymous: Fashion Brands’ Addiction to Fossil. Fuels. http://changingmarkets.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/07/SyntheticsAnonymous_FinalWeb.pdf

- De Souza, Izabella M., and Sharmila Pixy Ferris. 2015. “Social Media Marketing in Luxury Retail.” International Journal of Online Marketing 5 (2): 18–36. doi:10.4018/IJOM.2015040102.

- Deeley, R. 2022. “Dutch, Norwegian Regulators Issue Guidance on Controversial Higg Tool.” Business of Fashion, 11 October. https://www.businessoffashion.com/news/sustainability/dutch-norwegian-regulators-issue-guidance-on-controversial-higg-tool/

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2017. “A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future.” http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications

- Farley, G. J., C. Hill, and C. Hill. 2015. Sustainable Fashion: Past, Present and Future. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Farrer, Joan. 2000. “Wool: From Straw to Gold, an Ecological Assessment of the Lifecycle of Wool from Cradle to Grave and beyond Resulting in Yarns Composed of 100% Post Consumer Waste.” Doctoral thesis., Royal College of Art. https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/2864775/Wool_From_Straw_to_Gold_Thesis_.pdf.

- Ferrero-Regis, T. 2020. “From Sheep to Chic: Reframing the Australian Wool Story.” Journal of Australian Studies 44 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1080/14443058.2020.1714694.

- Francis, T., and F. Hoefel. 2018. “‘True Gen’: Generation Z and its Implications for Companies.” McKinsey & Company, November 12, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies

- Harle, K. J., S. M. Howden, L. P. Hunt, and P. Dunlop. 2007. “The Potential Impact of Climate Change on the Australian Wool Industry by 2030.” Agricultural Systems 93 (1–3): 61–89. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2006.04.003.

- Kirchherr, Julian, Denise Reike, and Marko Hekkert. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation & Recycling 127: 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Kusumasondjaja, Sony. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Visual Aesthetics and Presentation Modality in Luxury Fashion Brand Communication on Instagram.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 24 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1108/JFMM-02-2019-0019.

- Laitala, Kirsi, Ingun Grimstad Klepp, and Beverly K. Henry. 2017. Use Phase of Apparel: A Literature Review for Life Cycle Assessment with Focus on Wool. February 2018, Consumption Research Norway – Sifo Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.25769.90729.

- Laitala, L., I. G. Klepp, and B. Henry. 2018. “Does Use Matter? Comparison of Environmental Impacts of Clothing Based on Fiber Type.” Sustainability 10 (7): 2524. doi:10.3390/su10072524.

- Lee, E., and F. Weder. 2021. “Framing Sustainable Fashion Concepts on Social Media. An Analysis of #Slowfashionaustralia Instagram Posts and Post-COVID Visions of the Future.” Sustainability 13 (17): 9976. doi:10.3390/su13179976.

- Manieson, L., and T. Ferrero-Regis. 2022. “Cast-Off From The West, Pearls in Kantamanto? A Critique of Second-Hand Clothes Trade.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 1–11. doi:10.1111/jiec.13238.

- Massy, Charles. 2011. Breaking the Sheep’s Back: The Shocking True Story of the Decline and Fall of the Australian Wool Industry. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

- McCormick, Helen, Jo Cartwright, Patsy Perry, Liz Barnes, Samantha Lynch, and Gemma Ball. 2014. “Fashion Retailing – Past, Present and Future.” Textile Progress 46 (3): 227–321. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00405167.2014.973247?journalCode=ttpr20. doi:10.1080/00405167.2014.973247.

- Merrett, David, and Simone Ville. 2012. “Industry Associations and Non-Competitive Behaviour in Australian Wool Marketing: Evidence from the Melbourne Woolbrokers’ Association, 1890–1939.” Business History 54 (4): 510–528. doi:10.1080/00076791.2011.631123.

- Milanesi, Matilde, Yuliia Kyrdoda, and Andrea Runfola. 2022. “How Do You Depict Sustainability? An Analysis of Images Posted on Instagram by Sustainable Fashion Companies.” Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 13 (2): 101–115. doi:10.1080/20932685.2021.1998789.

- Mitchell, Joseph D., Luke J. Smith, and Leo Paul Dana. 2009. “The International Marketing of New Zealand Merino Wool: Past, Present and Future.” International Journal of Business and Globalisation 3 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1504/IJBG.2009.022602.

- Mogahzy, Y. E. El. 2009. Engineering Textiles: Integrating the Design and Manufacture of Textile Products. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing.

- Navone, Laura, Kaylee Moffitt, Kai-Anders Hansen, James Blinco, Alice Payne, and Robert Speight. 2020. “Closing the Textile Loop: Enzymatic Fibre Separation and Recycling of Wool/Polyester Fabric Blends.” Waste Management (New York, NY) 102: 149–160. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2019.10.026.

- Niinimäki, Kirsi, Greg Peters, Helena Dahlbo, Patsy Perry, Timo Rissanen, and Alison Gwilt. 2020. “The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion.” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (4): 189–200. doi:10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9.

- PETA. 2022. “Environmental Hazards of Wool.” https://www.peta.org/issues/animals-used-for-clothing/wool-industry/wool-environmental-hazards/

- Peterson, Hikaru Hanawa, Gwendolyn M. Hustvedt, and Yun-Ju (Kelly) Chen. 2012. “Consumer Preferences for Sustainable Wool Products in the United States.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 30 (1): 35–50. doi:10.1177/0887302X12446064.

- Raslie, H. 2021. “Gen Y and Gen Z Communication Style.” Studies of Applied Economics 39 (1): 1–18. doi:10.25115/eea.v39i1.4268.

- Richardson, Bob. 2001. “The Politics and Economics of Wool Marketing, 1950–2000.” Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 45 (1): 95–115. doi:10.1111/1467-8489.00135.

- Rocamora, Agnes. 2015. Thinking through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists. London: I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited.

- Rocamora, Agnès. 2017. “Mediatization and Digital Media in the Field of Fashion.” Fashion Theory 21 (5): 505–522. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2016.1173349.

- Rose, Gillian. 2001. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Segre-Reinach, S. 2022. Per un Vestire Gentile: Moda e Liberazione Animale. Milan: Pearson.

- Serafinelli, Elisa. 2018. Digital Life on Instagram: New Social Communication of Photography. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

- Sorensen, John. 2011. “Ethical Fashion and the Exploitation of Nonhuman Animals.” Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty 2 (1-2): 139–164.

- Statista. 2020. “Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of October 2020, Ranked by Number of Active Users.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

- Statista. 2021a. “Distribution of Instagram Users Worldwide as of October 2021, by Age Group.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/325587/instagram-global-age-group/

- Statista. 2021b. Distribution of Instagram Users Worldwide as of by Age and Gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/248769/age-distribution-of-worldwide-instagram-users/.

- Testa, Francesco, Benedetta Nucci, Fabio Iraldo, Andrea Appolloni, and Tiberio Daddi. 2017. “Removing Obstacles to the Implementation of LCA among SMEs: A Collective Strategy for Exploiting Recycled Wool.” Journal of Cleaner Production 156: 923–931. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.101.

- Textile Exchange. 2019. Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report. https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf.

- Textile Exchange. 2021. Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report. https://textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-and-Materials-Market-Report_2021.pdf.

- Thomas, Sue. 2008. “From ‘Green Blur’ to Ecofashion: Fashioning an Eco-Lexicon.” Fashion Theory 12 (4): 525–539. doi:10.2752/175174108X346977.

- UNECE. 2018. Fashion and the SDGs: What Role for the UN? United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). World Resources Institute (WRI). https://unece.org/DAM/RCM_Website/RFSD_2018_Side_event_sustainable_fashion.pdf.

- Valenzuela, F., and S. Böhm. 2017. “Against Wasted Politics: A Critique of the Circular Economy.” Ephemera Theory & Politics in Organization 17 (1): 23–60.

- Wheeler, Melissa. 2019. “The Future of Denim, Part #3: Waste Not; Water Not – Innovation.” Fashion Revolution. https://www.fashionrevolution.org/the-future-of-denim-part-3-waste-not-water-not-innovation/.

- Wiedemann, S. G., L. Biggs, B. Nebel, K. Bauch, K. Laitala, I. G. Klepp, P. G. Swan, and K. Watson. 2020. “Environmental Impacts Associated with the Production, Use, and End-of-Life of a Woollen Garment.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 25 (8): 1486–1499. doi:10.1007/s11367-020-01766-0.

- Wiedemann, S. G., M.-J. Yan, B. K. Henry, and C. M. Murphy. 2016. “Resource Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Three Wool Production Regions in Australia.” Journal of Cleaner Production 122: 121–132. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.025.

- Woolmark. 2021a. “Where Wool Comes From.” https://www.woolmark.com/fibre/woolgrowers/where-wool-comes-from/.

- Woolmark. 2021b. “Wool as a Sustainable Fibre for Textiles.” https://www.woolmark.com/industry/sustainability/wool-is-a-sustainable-fibre/.

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design & Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.