ABSTRACT

This paper explores the social visibility of children from Gaelic Irish and settler families during the 17th and 18th centuries given the very significant economic and cultural changes which followed the Plantation of Ulster. Predominantly Protestant settlers from Britain ousted native Catholic congregations from traditional places of worship, which became Protestant churches, and graveyards were now shared with Planter families. Using information from the south and west of the province of Ulster, it examines how children’s memorials may signify the religious, social and/or ethnic identity their families wished to express. It explores how distinctive familial plots were perhaps one means of maintaining complex Gaelic Irish kin relationships in danger of erosion and may have helped settlers replace or strengthen social networks from their original homes. High status interments which included children in prestigious native burial grounds may also have been a means of control and a powerful symbol of subjugation.

Introduction

Permanent memorials to the dead in the form of headstones, ledger stones, tombs, and vaults have persisted over centuries and can offer considerable material insights into past human behaviour. Archaeologists have previously studied them – their shape, manner of construction, emblematic content and the hopes and ideas expressed in inscriptions – to draw conclusions on cultural trends within communities (see Mytum Citation2000). Such studies have included, for example, tracing shifts in Puritan attitudes to death (Dethlefsen and Deetz Citation1966) and observing the material patterns of changing societal and belief systems (Rainville Citation1999; Donnelly et al. Citation2020). Memorials have also allowed insights into the archaeology of public health (Mytum Citation1989) and of emotion (Tarlow Citation1999; Citation2000).

Many burial grounds in Ireland have a lengthy history of use and, even when largely abandoned, have powerful resonances within modern communities (Evans [Citation1957] Citation1976; Kelleher Citation2022). It is now increasingly acknowledged that such memorials can be a source of ‘meaningful archaeological information’ (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017, 103), but most previous studies in Ireland have not focussed on what commemorative practices can tell us about childhood in the past. Exploratory analyses of memorials for children in Irish burial grounds (McKerr Citation2010; McKerr and Murphy Citation2012; McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009), however, have identified their clear visibility within the graveyard population, where children of all ages (including infants) were commemorated with permanent memorials. This can be seen as an expression of personal loss, but also as an acknowledgement of their wider social importance; of their ‘belonging’ within a community which included them fully in death as well as in life. This becomes perhaps more significant when considering the history of post-medieval Ireland, and the province of Ulster in particular, when communities became fractured along religious and ethnic lines following the Protestant Reformation and the influx of settlers from Britain from the early seventeenth century onwards.

This study was undertaken to explore the social visibility of children from both Gaelic Irish and settler (‘Planter’) families during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by investigating the frequencies and appearance of grave memorials which commemorated them. Using information from burial grounds in the south and west of the province of Ulster, it examined how children’s memorials may signify the religious, social and/or ethnic identity their families wished to express, given the very significant economic and cultural changes which followed the Plantation of Ulster in the early seventeenth century.

The Plantation of Ulster

Late Medieval Gaelic Ireland was a hierarchical society comprised of autonomous lineages headed by Gaelic lords who controlled both a geographical territory and the people within that landscape. It had an independent legal system which existed alongside powerful kinship obligations (Nicholls Citation2003); the traditional territories of the Gaelic lords in the northern province of Ulster are shown in . By the end of the sixteenth century resistance to English intervention had escalated into open conflict and the Flight of the Earls in 1607 effectively ended the power of the ruling Gaelic lordships in Ulster (Bardon Citation2005; Hunter Citation2012). The English government then undertook an extensive redistribution of their forfeited territories, mainly to English and Scottish settlers – the ‘Plantation of Ulster’. This was a slow process which unfolded across the province over the seventeenth century, a continuation of the earlier Elizabethan settlement elsewhere in Ireland, ultimately – and deliberately – shaping a divided society. It represented not just an economic proposition, but also the establishment of the English legal system, the imposition of the reformed religion (Protestantism) and the use of the English language (Gillespie Citation2006).

Figure 1. Gaelic Irish territories preceding the Ulster Plantation (prepared by Libby Mulqueeny, after https://sites.rootsweb.com/~irlkik/ihm/gif/ire1600.gif).

By 1630, the island had an estimated population of some 40,000 British settlers and 200,000 Gaelic Irish individuals (Macafee Citation1992, 95); settlements and planned towns grew up around the fortified Plantation dwellings of the new landholders. Throughout the seventeenth century, Planter and Gaelic Irish populations settled into often uneasy relationships (Bardon Citation2005; Donnelly Citation2007), at times breaking into open hostility and armed conflict. The later seventeenth century is commonly seen as a period of consolidation of Protestant ascendancy (Foster Citation1989), which shaped the social and economic structures of the following century. However, this was gained at much cost in human terms particularly to Gaelic Irish communities, but also to settlers. The years following the initial Plantation placed serious economic and social burdens on many families compounded by a climatic downturn that led to a period of very cool weather, known as the Little Ice Age, which lasted until the mid-nineteenth century (Fagan Citation2000; Lamb Citation1982). Along with civil unrest and epidemics, the resultant food insecurity took a heavy toll, especially on the most vulnerable, and surviving burial and taxation records for the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries indicate a high rate of child mortality in Ulster (Macafee and Morgan Citation1981).

Post-Plantation Burial Grounds

As Graham and Proudfoot (Citation1993) have noted, the influx of settlers into the traditional territories of native Irish families brought both continuity and change, with Gaelic Irish castles and churches initially retained by settlers because they were useful, both practically and symbolically. Catholic congregations found themselves ousted from their traditional places of worship, which became post-Reformation ‘Protestant’ churches (at this period, the term for Episcopalian congregations and the ‘Established’ or state church, here known as the Church of Ireland). Burial grounds were now to be shared with Planter families many of whom, though not all, were Protestant (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017), and graves from both communities began to be increasingly marked by permanent memorials, indicating the adoption by Gaelic Irish families of commemorative practices originally introduced by settlers (McCormick Citation2007).

As a result of the Penal Laws of the late seventeenth century, the Church of Ireland maintained control of burials within parishes, which meant that Catholic and Dissenting congregations could not legally create their own graveyards (Donnelly Citation2004; Macafee and Morgan Citation1981), although a number did so (including St Tierney’s, Roslea, Co. Fermanagh, included in this study). With the Penal Codes falling into effective disuse, and the passing of the Catholic Relief Act in 1782 (Curl Citation2000), other denominations could begin to openly establish their own churches and associated graveyards. However, over the following centuries, many settler and Gaelic Irish families, regardless of their chosen religious faith, continued to use the burial grounds of older churches which had been adopted by incoming Protestant settlers. This was true even when the buildings fell into ruin and the churches were rebuilt elsewhere with new graveyards attached. How families sharing contested spaces may have chosen to differentiate themselves through the memorials created for their children is the focus of this paper.

Materials and Methods

The 62 graveyards included in the study were located in seven counties – Armagh, Cavan, Derry, Donegal, Fermanagh, Monaghan and Tyrone – in the historic province of Ulster. All but Monaghan were Plantation counties and, although Monaghan was outside the remit of the official Plantation scheme (the Elizabethan government having previously established Gaelic Irish freeholders there), British settlers had acquired estates from the early seventeenth century, and by the 1630s they were the majority landowners (Bardon Citation2005; Roulston Citation2011).

The burial grounds selected for analysis were all attached to ecclesiastical sites dating to at least the eighteenth century ( and ). The history of the sites was determined using the on-line databases of the Archaeological Survey of Ireland for those currently in the Republic of Ireland (https://www.archaeology.ie/archaeological-survey-database), the Sites and Monuments Record for Northern Ireland (https://apps.communities-ni.gov.uk/NISMR-PUBLIC/Default.aspx), and information from the reports of inscriptions where relevant.

Table 1. Gravestone inscriptions recorded at sites currently in Northern Ireland.

Table 2. Gravestone inscriptions recorded at sites currently in the Republic of Ireland.

The majority of burial grounds (79.0%; 49/62) were associated with documented ecclesiastical sites established between the Early Medieval period, from the fifth century onwards (Ó Cróinín Citation2017), and the Late Medieval period, which in Ireland can generally be regarded as ending somewhere between the mid-sixteenth century (Horning Citation2007) and c. 1600 (Duffy, Edwards, and FitzPatrick Citation2001). Local histories consider four further sites (Acton, Co. Armagh; Finner, Bundoran, Co. Donegal; St Andrew’s, Killyman, Co. Tyrone and Teightunny, Co. Donegal) as possible Medieval foundations but no confirmatory evidence is available, and they are determined in the Sites and Monuments Record/ Archaeological Survey of Ireland to be most likely Post-Medieval in origin. The remaining nine graveyards were associated with churches established in the early Post-Medieval period (following the Ulster Plantation). Four sites (Irvinestown, Co. Fermanagh; St Anne’s, Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal; St Michael’s, Castlecaulfield, Co. Tyrone and St Salvator’s, Glaslough, Co. Monaghan) were closely associated with Plantation estates and fortified dwellings. St Columb’s Cathedral, Derry, was expressly built by settlers of the London Companies in 1628–1633 ‘as a symbol of the Established church in a foreign land, to impress with its grandeur and to suggest the homeland of the settlers’, but it also laid claims to the past through the association with St Columba (Curl Citation2000, 147). Of the remaining sites established in the Post-Medieval period, St Tierney’s, Roslea, Co. Fermanagh, was unique in being founded as a Roman Catholic church and burial ground in the eighteenth century, at a period when this was technically illegal; the present church dates from c. 1800 (Rowan Citation1979, 479).

Most of the early churches are now ruined or indiscernible. Although a number of burial grounds are still associated with active churches, these are all now modern (Post-Medieval) buildings, and almost all serve Church of Ireland congregations; the exceptions are the Roman Catholic churches of St Jarlath’s, Clonfeacle, Co. Tyrone and St Tierney’s, Roslea, Co. Fermanagh.

Defining Children and Childhood

Archaeologists have long recognised the difficulties of assigning age categories to past human societies, where social and biological age may not necessarily have coincided with economic and legal maturity (Barclay and Reynolds Citation2016; McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009). Accordingly, for this study we adapted the convention developed by Shahar (Citation1992, 21) that those under the age of 18 years should be regarded as ‘children’, unless biographical information indicated they had taken on adult roles, such as marriage partners, artisans or parents. This approach has limitations (see McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009), which will be further discussed, but provides a consistent framework for data collection.

Data Collection – Inscriptions

Records from published, private or church documents were reviewed and those burial grounds which included seventeenth- and eighteenth-century memorials for children were selected for examination.

Grave memorials which specifically marked the burial of a child or children were documented and numbered. These included cases where it was clear that the individual was aged less than 18 years since the age was stated; they were described as an ‘infant son/daughter’, a ‘minor’, as having ‘died young’ or ‘died in infancy’; or where confirmatory biographical information was available. When a child was the first-named on the gravestone they were designated as ‘primary’, while those that followed adults in the listings were considered as ‘secondary’ memorials.

In addition, grave memorials for all definite adults only were recorded. These included those aged 18 years or older, or who are described as, for example, wife/ husband/ mother/ father/ artisan/ clergyman/ doctor or, again, where confirmatory biographical information was available.

Terms such as ‘child’, ‘son’ or ‘daughter’ can, of course, also be applied to adults and if age-at-death is not recorded, it cannot be assumed that the individual was under 18 years of age. For example, Lydia Fairley’s memorial in St Columb’s Cathedral graveyard, Derry, described her as:

The only child of David Fairley Esq./ and Lydia his wife/ both of this City

Here lyes ye body of Cornet W. Clements & Lettice his wife, his moth[er] & grandmoth[er], 2 broth[ers], 2 sis[t]ers & 12 children all since 1700. Ys was set up in 1752

Data Collection – Morphology

Previous studies in smaller numbers of Post-Medieval graveyards (McKerr Citation2010; McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009) had suggested the existence of differentiation in children’s monument types between settler and native Irish families. Stylistic differences in terms of perceived religious affiliation had previously been noted in Mytum’s (Citation2009) study of monuments in West Ulster, although this did not specifically address the situation for children. Mytum’s findings have been confirmed by a more recent and detailed study at St Mary’s Church, Ardess, Co. Fermanagh, which, rather than focussing on religious differences, has identified ‘divergent traditions of memorialisation between native Irish and Planter groups’ (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017, 134). Memorial types were rarely reported in the aforementioned records of inscriptions and site visits were the only means of determining the morphology of children’s monuments. As such, site visits were made to 26 burial grounds for this purpose.

It is possible to divide grave markers into a number of broad typologies (Mytum Citation2000) but for this study, two descriptive categories were used. These comprised ringed crosses (sometimes referred to as discoid markers or wheeled crosses) and horizontal/upright slabs (which include headstones, ledgers and table tombs). Ringed crosses are an early monument form which occur most frequently in south-west Ulster (Mytum and Evans Citation2003; Thomson Citation2006a; Citation2006b) and they may also have mortality symbols carved on the reverse (Mytum Citation2009; Thomson Citation2006b). Attributing religious affiliation on the basis of perceived ‘British’ or ‘Irish’ surnames is problematical, but can be an indication of ethnic origins (McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017). To determine if there were differences between the form of memorial chosen by Gaelic Irish and settler families, and if this varied over time, the surnames and date ranges associated with each type of memorial were also recorded.

Results

All of the burial grounds contained gravestones which were illegible, damaged or otherwise did not carry sufficient information for inclusion. For example, in Donagh graveyard, Co. Monaghan, out of 109 memorials which carried an eighteenth-century date, only 83 (76.0%) contained sufficient information for inclusion in ; a further 15 memorials carried no date or were illegible. At Tullanisken, Co. Tyrone, 60 out of a total of 67 recorded eighteenth-century gravestones (89.9%) contained sufficient information to be included in . However, a further 22 permanent memorials were noted as illegible or carried only a minimum of information, such as a family name, while two memorials with seventeenth-century dates could not be included due to lack of information on those interred. This is a recurrent issue with studies of grave memorials and Parkinson and Murphy (Citation2017, 129) noted that at Ardess, Co. Fermanagh, 51 out of 448 memorials (11.0%) could not be dated due to lack of information. This reinforces the fact that this study can only offer a broad comparison of memorialisation since it just represents a proportion of the children (and adults) who were buried in the graveyards over the centuries in question. Furthermore, a large proportion of the population will lie in unmarked graves, or may have had impermanent memorials.

Table 3. Summary of memorial numbers.

In all, 3389 memorials from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries met the criteria for inclusion ( and ). Of these, 2966 represented confirmed adults only, and 423 (12.5%) represented memorials for children, either solely or included with other family members ().

Children’s Memorials – Inscriptions

All 62 graveyards selected were found to contain eighteenth-century gravestones that commemorated children who, when precise details were given, ranged in age from 10 days to 17 years; many others were noted simply as having died young, or in infancy. Only eight burial grounds contained confirmed seventeenth-century memorials for children. However, seventeenth-century memorials for adults were also poorly represented compared to the numbers in the following century and children’s memorials represented 11.5% (12/103) of the total. Of those, the great majority (91.7%; 11/12) were for individuals with Scottish or English names (see ) and date from 1622 onwards; only one memorial for a child with a Gaelic Irish name was identified and dated to the later seventeenth century, from Magherintemple Old Graveyard Co. Cavan. One of the earliest secondary memorials and located at St Patrick’s, Coleraine, Co. Derry, was a tribute to Mrs Ann Munro (the Scottish wife of Colonel George Munro), who died aged 25 years in 1647, survived by two sons and predeceased by five other un-named children ‘as fore-runners did go to possess Heaven before her’. Her elaborate memorial is very much in the eulogising style of similar Scottish monuments of the period to ‘vertuous women’, with culturally appropriate references to her merits as a wife and mother (Willsher Citation1996, 58–62). In this respect, her children seem to be represented more as part of her persona than as little individuals in their own right, and given what might be described as a ‘provisional “personhood”’ (Montgomery Citation2000, 20).

Table 6. Probable ethnicity of surnames associated with seventeenth-century memorials for children.

By the following century, the number of gravestones recorded for children had increased to 411, representing one eighth (12.5%) of the total confirmed eighteenth-century memorials. Memorials for children with both Planter and Gaelic Irish surnames were identified, and the latter were well represented. For example, in Aghalurcher, Co. Fermanagh, of the 25 memorials recorded for children, 14 (56.0%) carried Gaelic Irish surnames (date range 1737-1791). In Killeevan, Co. Monaghan, out of 15 memorials for children, nine (60.0%) carried Gaelic Irish surnames (1733-1796), while at Old Eglish graveyard in Co Armagh, this figure was 75.0% (15/20; 1704-1789).

Overall, 7.7% of monuments were designated as primary burials for children, either solely or as the first recorded interment in a family grave, and represented some 61.5% (260/423) of the total recorded children’s memorials in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The numbers in individual burial grounds ranged widely, from a single secondary memorial, as at Acton Old Graveyard, Co. Armagh, and St Salvator’s, Glaslough, Co. Monaghan, to a maximum of 25 at Aghalurcher, Co. Fermanagh, and St Patrick’s Cathedral, Armagh, where more than half were designated as primary. At a first glance there does not appear to be a recognisable pattern in distribution. While important and wealthy ecclesiastical centres (such as the cathedrals of St Columb’s, Derry, St Macartan’s, Clogher, and St Patrick’s, Armagh) might be expected to have high numbers of both adult and child memorials, these were also well represented in some semi-rural or rural sites (e.g. Aghalurcher, Co. Fermanagh; Donaghmore, Co. Tyrone; Old Eglish, Co. Armagh and Killeevan, Co. Monaghan), suggesting their significance to a more dispersed population.

Children’s Memorials – Form

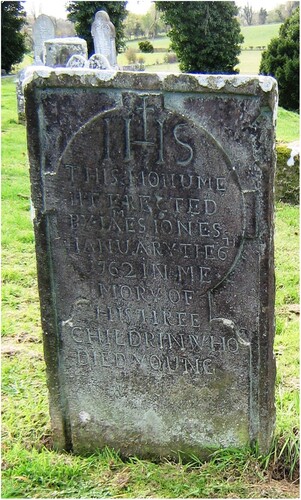

Two types of gravestone forms were found at the sites visited – upright, low ringed crosses and rectangular slabs (horizontal or as headstones). The child memorials located on site visits were similar in size and shape to those for adults. In two instances, the Jones family group in Aghavea, Co. Fermanagh (from 1734 to 1762), and the Magauran gravestone (1764) at Templeport, Co. Cavan, memorials displayed features of what might be seen as a transitional form between a ringed cross and an upright slab (Mytum Citation2006; ). Very few ringed crosses commemorating children were located and all carried Gaelic Irish names ().Footnote1, Footnote2

Figure 2. ‘Transitional’ ringed cross imagery used in a Jones family memorial in Aghavea burial ground, Co. Fermanagh. THIS MONUME/ NT ERECTED/ BY JAMES JONES/ JANUARY THE 6TH/ 1762 IN ME/ MORY OF/ HIS THREE/ CHILDREN WHO/ DIED YOUNG (photograph L. McKerr).

Table 4. Site visits: eighteenth-century children’s memorial forms and associated names.

The dates of the ringed cross memorials commemorating children ranged from 1714 to 1754 (); the majority of the ledger memorials carried surnames of settler origin, mostly Scottish (e.g. Armstrong, Campbell, Ferguson, Graham and Todd) but also English and Welsh (e.g. Atkinson, Lyons, Davis and Williamson). A total of 66 different names ranging in date between 1700 and 1796 were recorded; names such as Armstrong, Campbell, Foster, Miller and Scott appeared at a number of sites, reflecting their settlement in different counties. A further 13 surnames were either undetermined in origin (such as Gudden and Murr), or common to Scotland, England and Wales as well as Ireland, where they were anglicised in spelling, such as McAdam, Smith/Smyth, Curry and Rodgers (Bell Citation2021). The use of ledger memorials for children of Gaelic Irish origin was noted from 1723 onwards (the Coan family grave at Assaroe Abbey, Co. Donegal) and, in total, 43 different Gaelic Irish surnames were recorded.

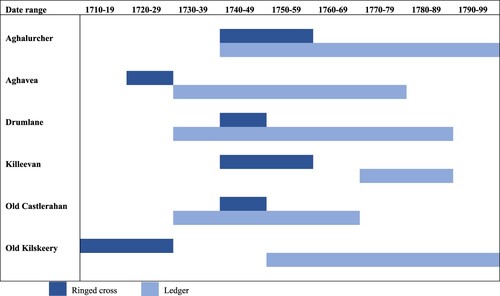

There were six sites where both types of memorial were located – Aghalurcher and Aghavea, Co. Fermanagh; Drumlane Abbey and Old Castlerahan, Co. Cavan; Killeevan, Co. Monaghan; and Old Kilskeery, Co. Tyrone. Ledger memorials for families with Gaelic Irish names either overlapped with the later period of use of ringed crosses (as at Aghalurcher, Co. Fermanagh; Drumlane Abbey and Old Castlerahan, Co. Cavan) or dated to the later part of the eighteenth century (at Aghavea, Co. Fermanagh; Killeevan, Co. Monaghan and Old Kilskeery, Co. Tyrone). Something of the contrast between the ledger stone for a settler child, Robert Beacom (aged five years) and the ringed cross memorial for a child from a Gaelic Irish family, John O’Neill (aged four years), can be seen at Old Kilskeery, Co. Tyrone ().

Figure 4. ‘Planter and Gael’, from Old Kilskeery burial ground, Co. Tyrone. a) Armorial ledger stone for Thomas Beacom and his family. HERE LIETH THE BODY /OF THOMAS BEAC/ OM WHO [DAUCUS]/ THE 1 1729 AGED 67/ ALLSOW THE BODY OF/ ROBERT BEACOM WHO/ DYED SEPTEMBER 28 1756 AGED 5 YEARS. A/ ND 2 OF HIS BROTHERS, 3 S/ ONS TO JOHN BEACOM O/ F GLASMULLAGH/ Edward Beacom/ Glasmullagh died 1st April 1859. Aged 100/ years (photograph L. McKerr). b) Ringed cross for the O’Neill family. HERE/ LIETH/ THE/ BODY/ OF/ MR. JOHN O’NEILL/ SON TO MR. HENERY O NEILL/ WHO DYED / THE 2 OF MAY 1714/ AGED 4 YEARS/ CATHEREN O’NEILL/ DYED THE YEAR 1711 (photograph L. McKerr).

![Figure 4. ‘Planter and Gael’, from Old Kilskeery burial ground, Co. Tyrone. a) Armorial ledger stone for Thomas Beacom and his family. HERE LIETH THE BODY /OF THOMAS BEAC/ OM WHO [DAUCUS]/ THE 1 1729 AGED 67/ ALLSOW THE BODY OF/ ROBERT BEACOM WHO/ DYED SEPTEMBER 28 1756 AGED 5 YEARS. A/ ND 2 OF HIS BROTHERS, 3 S/ ONS TO JOHN BEACOM O/ F GLASMULLAGH/ Edward Beacom/ Glasmullagh died 1st April 1859. Aged 100/ years (photograph L. McKerr). b) Ringed cross for the O’Neill family. HERE/ LIETH/ THE/ BODY/ OF/ MR. JOHN O’NEILL/ SON TO MR. HENERY O NEILL/ WHO DYED / THE 2 OF MAY 1714/ AGED 4 YEARS/ CATHEREN O’NEILL/ DYED THE YEAR 1711 (photograph L. McKerr).](/cms/asset/8e76eb62-9ef8-47b9-8b01-38ad51035c2e/ycip_a_2235649_f0004_oc.jpg)

Children’s Memorials – Decorative Motifs

It was difficult to systematically study decorative motifs on the memorials due to issues of preservation but some general observations can be made. Similar decorative elements were evident on child memorials compared to those of adults; inserts on stones included religious iconography such as the Tree of Life, paschal lamb, crowing cocks and religious verses. Armorial carvings were also present on some of the children’s memorials located, although most were secondary burials. These included Planter families such as that for the Beacoms from Kilskeery, Co. Tyrone (see ) and the Todd children, from St Patrick’s Coleraine, Co. Derry, and were also present on memorials for children from Gaelic Irish families such as the O’Briens and McCabes. Two distinctive primary memorials with armorial carvings for children from Planter families, Marie Balfour (1672) and Margret Wilson (1746) are discussed in the following section. Mortality symbols also appear on gravestones where children were the primary or only burials, as in the memorials for the infant John McCollum in St Patrick’s, Coleraine, Co. Derry, and Michael Connolly, aged 10 years, in Killeevan, Co. Monaghan ().

Figure 5. Examples of memorials with mortality symbols. (a) Front view of memorial for Michael Connolly in Killeevan burial ground, Co. Monaghan. THIS STONE WAS ∼/ ERECTED BY ARTHUR/ CONNOLLY IN MEMORY/ OF HIS SON MICHAEL/ CONNOLLY WHO DE∼/ PARTED THIS LIFE/ OCTOBER THE 7TH / 1779 AGED 10 YEARS. (b) Rear view of the Connolly memorial with verse. STAY PASSINGERS STAY/ AND SEE AS YOU ARE∼/ NOW ONCE HAVE I BEEN/ BUT AS I AM NOW SO/ SHALL THOU BE. PREPARE/ FOR DEATH AND FOLLOW/ ME∼ (c) Front view of the gravestone for the Edmeston boys in St Patrick’s graveyard, Coleraine, Co. Derry. HERE/ LIETH/ THE BODYS OF TWO/ CHILDREN ALSO ROBT/ WHO DEP DECMR 1795/ AGED 4 YRS& 3 MONTHS SONS /OF ROBT EDMESTON (d) Mortality symbols on the rear of the Edmeston gravestone. REMEMBER DEATH (photographs L. McKerr).

As noted earlier, it cannot be assumed that all settlers were Protestant (that is, members of the Church of Ireland) or Dissenters, or that all those with Gaelic Irish names were Roman Catholic. It is possible to determine religious identity with some confidence from the inclusion of monograms such as IHS which is largely, but not exclusively, a sign that the deceased was a Roman Catholic (McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017; Timoney Citation2005), or from inscriptions that ask for prayers for the soul of the deceased. Where visible on the memorials located, these have been noted in . What may be perceived as Catholic iconography was present on the gravestones for a number of names deriving from settler ancestry (such as Campbell, Jones, McIntire and Ware).

Table 5. Site visits: religious inscriptions on eighteenth-century gravestones for children.

Family Histories

A number of family plots were observed where multigenerational burials had occurred, and this tradition applied both to those with Gaelic Irish and settler surnames. Many of the memorials clearly defined the child’s lineage, usually in relation to paternal status, and this was true for both male and female children. A number of particularly visible and striking early gravestones for young girls were recorded on site visits; the dates ranged from 1672 to 1740. The children were aged from 13 months to 13 years, and were the sole or primary burial inscribed on the memorial. They were all from Planter families and the majority had Scottish surnames (Balfour, Todd and Wilson), although Brooke is English in origin (Bell Citation2021). The gravestone for Marie Belfourd [Balfour], who died aged two years in 1672 and was buried in Aghalurcher, Co. Fermanagh, and also that of Margret Wilson, who died aged one year and nine months in 1740 and was buried in St Patrick’s Church Coleraine, carried striking armorial carvings (). Both families were relatively early Plantation arrivals; Marie’s family acquired their estate through Sir James Balfour, who settled in what is now Lisnaskea, Co. Fermanagh, in 1615 (Crichton Citation1896; Johnston Citation2004) and the Wilson surname appears on the Muster Roll for Estates in County Londonderry in 1630 (Macafee Citation2012).

Figure 6. Some distinctive early gravestones for young girls of settler families. (a) HERE LYETH THE/ BODY OF MARIE BELFOURD OF TWO YEA/ RES OLD DAUGHT/ ER TO CHARLES BALFOURD ESQR WHO DEPAR/ TED THIS LYFE THE/ 10 OF NOVBR AN/ NO 1672. Aghalurcher graveyard, Co. Fermanagh (© Crown DfC Historic Environment Division). (b) MARGRET WILSON DIED YE 1 OF/ DECR 1740 AGED 1 YR 9 MONTH/ ALSO WILLM WILSON HER FATHER/ WHO DIED YE 23 OF APRIL 1742/ AGED 33 YEARS. St Patrick’s graveyard, Coleraine, Co. Derry (photograph L. McKerr).

The youngest girl commemorated, Shusanna Todd, died in 1731, aged 13 months. The Todds were very wealthy merchants who settled in Coleraine in the early seventeenth century (McMurty Citation2012); again, the surname appears on the Muster Roll in 1630 (Macafee Citation2012). Her memorial, now almost illegible, is in close proximity to a much larger and more elaborate Todd gravestone, heavily ornamented with the family coat of arms, commemorating the death of her grandfather, Daniel Todd, in 1737 and listing her uncles and aunt who had died young. By comparison, the simple memorial for Shusanna includes what might be seen as a very personal statement of loss – both parents were named, and her exact date of birth, and her age at death were given. Susanna Brooke died aged 13 years in 1733, and her gravestone occupies a prominent position within the now-ruined Drumlane Abbey, Co. Cavan. The cryptic poetic inscription on her ledger (weathered to illegibility) is highly unusual compared to the statements on other children’s memorials:

Susanna Brooke: entombed lies here/ Who died of age the: 13th year/ Xber the 13th years 30 and three to: 17 hundred added must be/ When the virgin departed lamented by all/ And heavenly promotion was her earthly fall/ Sic Gloria transit mundi … (O’Reilly Citation1979, 356).

Discussion

Memorialisation is the final step in a funerary process, most of which is now largely invisible. It begins with loss, preparation for burial, the interment itself and finally, acts of commemoration, and although these can vary across time and place, they generally follow a culturally appropriate ritual pattern (e.g. Christie Citation2023; Tait Citation2002). For the children and adults in the graveyards surveyed who have no permanent memorials, we have lost sight of all these steps, but cannot assume that commemoration (such as visiting the grave or saying prayers) did not occur.

Commemoration of Children

The analysis of inscriptions on memorials in this study found that 12.5% (423/3389) were for children, either solely or included with other family members. While this proportion is relatively small, it confirms that at least some children had an acknowledged social role from infancy onwards. It is not possible to say how representative these figures are of the general population at the time; the results of this study exclude what is almost certainly a much greater number of both children and adults. As noted earlier, as well as gravestones with illegible or incomplete inscriptions, there is an absence of information on those buried with ephemeral memorials or in unmarked graves. Additionally, an unknown number of children will also have been buried in the informal graveyards known as cillíní (Donnelly and Murphy Citation2018), a final resting place for those, including unbaptised infants, whose interment would not have been sanctioned by Roman Catholic church authorities.

The Rise of Memorialisation

Although Medieval examples of elite memorials within churches exist elsewhere in Ireland (Rae Citation1970), there was no widespread tradition of permanent memorialisation in pre-Plantation Ulster, and it seems that this was an introduction by Scottish settlers (McCormick Citation2007). Overall, the total number of legible surviving memorials from the seventeenth century in this study is low when compared to the following century, even allowing for substantial demographic changes; the population of Ulster was an estimated 240,000 in 1630, of which some 40,000 were thought to be British (Macafee Citation1992, 96). By 1732, the general population had more than doubled, to around 600,000, of which almost half (270,000) were estimated to be British (Macafee Citation1992, 96), and had risen to around 820,000 by the later eighteenth century (Kennedy, Miller, and Currin Citation2012, 61).

It would be expected, however, that the number of early examples of monuments, both for adults and for children, would be low. Initially, only the very wealthiest families could have provided inscribed memorials and even when they would have become more available and desirable the social unrest and economic hardships of the seventeenth century meant that the majority of people would not have been in a position to adopt the practice. It should be noted too that the situation is complicated by the fact that preservation of early monuments is poor, with illegible or broken stones evident in all graveyards.

Of the 12 recorded examples of seventeenth-century memorials for children, the earliest were for wealthy settlers (the Munro family, in St Patrick’s, Coleraine and the Stewart children in Donaghenry, Co. Tyrone). The only memorial for a child of Gaelic Irish descent, John Fay, dated to 1690 and was found in Magherintemple burial ground, Co. Cavan, perhaps providing confirmation that the Gaelic Irish had started to follow settler practice and use grave memorials to mark the burial places of their dead (McCormick Citation2007), but numbers are much too low to generalise. By the eighteenth century however, the rise in ‘external commemoration’ (McCormick Citation2007, 367–368; Mytum Citation2006, 105) was notable, and not only for the elite; this follows an earlier pattern established in Scottish burial grounds from the seventeenth century, which could be described as ‘a gradually increasing democracy of death’ (Willsher Citation1996, 4). It was not only prominent Planters or Gaelic Irish nobles now who raised memorials for their families, but also those ‘ordinary people’ who could afford memorials and whose surnames, whether Irish or British in origin, are still common in parts of Ulster today (Livingstone Citation1969, 68).

The number of eighteenth-century monuments for both for children and adults was found to differ greatly between burial grounds, with nine (14.5%) having only one memorial suitable for inclusion. The reasons for this are probably related to preservation issues which will have particularly impacted upon those that were documented most recently. Where the perceived majority of memorials were from Gaelic Irish and/or Catholic communities (for example in Clones Abbey, Co. Monaghan, and Finner, Co. Donegal), low numbers overall may reflect the fact that belonging to either group carried economic as well as social penalties during the period (Donnelly Citation2004; McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009), or that they had deliberately resisted the adoption of this aspect of ‘imposed Planter material culture’ (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017, 134). Clones was part of an area which was more slowly colonised, however, with Gaelic Irish families maintaining substantial landholdings in County Monaghan until the later seventeenth century (McMahon Citation2018; Roulston Citation2011). The settlers had established a new church and graveyard at St Tighernach’s at the end of the seventeenth century (McMahon, Slowey, and O’Neill Citation1988, 90), and the two communities did not share their burial grounds in the same way that occurred elsewhere. The low numbers may therefore reflect the fact that the pace of cultural change was slower than in areas, such as Derry, where settlement was established early in the Plantation process.

Comparatively fewer children’s memorials were also evident in the burial grounds of new Post-Medieval Protestant churches in wealthy Plantation settlements, and it might be expected that economic factors would not have accounted for the differences. Given that the sites were in use since the beginning of the eighteenth century, it may be that families preferred to use their established plots in older graveyards ‘however neglected and overcrowded they may be’ (Evans [Citation1957] Citation1976, 294). For example, St Salvator’s, Glaslough, Co. Monaghan, replaced the old church and burial ground at Donagh and it has only one confirmed child memorial, compared to eight at Donagh. However, not all the burial grounds in this survey were so related and a more detailed and localised comparison would be required before any firm conclusions could be drawn.

Separation and Segregation

The question of spatial segregation of different populations within burial grounds was not explored during site visits, although there is evidence that this was specifically practiced in a number of graveyards, including Carne, Co. Donegal (Ó Gallachair, Slevin, and Cunningham Citation1989, 135); Aghalurcher, Aghavea and Ardess, all in County Fermanagh, and to some extent at Killeevan, Co. Monaghan (Mytum and Evans Citation2003; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017). This may have arisen at least initially for a number of reasons, including a need to mark social boundaries between competing populations. In the case of Gaelic Irish families, however, there may have also been earlier familial associations; the fact that there were no surviving recognisable grave markers (or at least, those recognisable to modern observers) should not exclude the possibility that people knew where previous generations had been buried. All of the graveyards visited had undated, uninscribed stones, which may have been field stones or rubble from the derelict church used to mark burials (Mytum Citation2009; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017) and this may have been a common practice before the more widespread introduction of permanent memorials. By the eighteenth century, Gaelic Irish communities were being increasingly marginalised, and distinctive familial plots were perhaps one means of maintaining the complex kin relationships which were in danger of erosion.

For the settlers arriving in a new and often hostile land, they needed to establish social networks to replace or strengthen the kin groups from their original homes. With some modern immigrant populations, there is a preference for spatial association within burial grounds and the placing of cultural references on memorials (Francis, Kelleher, and Neophytu Citation2005); visiting cemeteries is one way of maintaining a sense of community, and shared ethnic identities can be regarded as a ‘greatly extended kinship group’ within their new environment (Francis, Kelleher, and Neophytu Citation2005, 191–192). Early nineteenth-century Irish settlers in Lowell, Massachusetts, USA, for example, soon established their own burial ground (later known as St Patrick’s). While following the example of their Yankee contemporaries and using black slate stone for their memorials they also introduced a suite of differences in the inscriptions and motifs that clearly signalled their origins as Catholics who had migrated from Ireland (Donnelly et al. Citation2020). For the early Plantation settlers in Ireland, burial together then can perhaps be seen as an extension of ‘relatedness’ and this can be expressed both through spatial separation and inscriptions that create a narrative of ‘belonging’ and establish a sense of place in society (McKerr Citation2010, 141).

Once such initial boundaries were established, however, and permanent memorialisation became more common, a tradition of familial burial plots arose in Irish graveyards (Mytum Citation2004, 33). Initially, these may have consisted of simple markers inscribed with a surname, or a brief statement of ownership such as: ‘This stone and burial place belongeth to Roger McMahon and his posterity 1745’ (Mulligan and McMahon Citation1984, 429). Mytum (Citation2004, 33–34) notes the emphasis both on plot ownership, and the desire to signal ‘continued family use’ with these simple markers. Individualised family memorials become more common as the eighteenth century progressed (Mytum Citation2004), perhaps in part due to improved technology which allowed for longer inscriptions, and children were specifically included either as the first named or in a secondary position. They may be individually named, or unnamed (as with the Jones children in Aghavea, Co. Fermanagh, see ), accurately aged or described simply as infants or having died young. A number of distinctive family groups of gravestones, both for settler and Gaelic Irish families, were noted on site visits where some multigenerational plots can be seen to extend across four centuries.

Signs and Signifiers

In general, competing groups adopt ‘belief systems, symbols and practices’ which set them apart from others (Cairns Citation2000, 439). Differences in memorialisation are one way of maintaining such identities when a shared space is contested. For those children who were commemorated with a permanent grave marker, this was not only an expression of private loss for families; churchyards are public spaces, even more so when the attached church had an active congregation. As Mytum (Citation2003/2004, 114) has noted of later monuments, an inscribed stone would have been ‘interpreted by others at the time, and given meaning to them through their perception of its physical form and location, but also through their knowledge of individuals named on the stone, and the family generally’. How such memorials are made visible – that is, not just their shape and content, but where they are placed – may therefore carry additional information; burial grounds themselves can be seen as ‘in effect, open cultural texts, there to be read and appreciated’ (Meyer Citation1993, 3). Permanent memorials which have survived will therefore contain both direct and indirect messages about society in the past.

Dating from early to mid-eighteenth century, a number of the graveyards contained children’s memorials in a distinctive ringed cross (or ‘discoid’) form. This is in keeping with the findings for similar adult memorials in south and west Ulster (Mytum and Evans Citation2003; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017; Thomson Citation2006b). Although both Gaelic Irish and settler names are found on horizontal and upright slabs, only Gaelic Irish names are found on the ringed cross stones for children located in the graveyard surveys. This characteristic has been noted in other more general studies of this monument form (Mytum Citation2006; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017). It is thought the distinctive shape may owe its origins to that of early Irish high crosses (Mytum Citation2006) although it may also reference other aspects of pre-Plantation ‘visual culture’ (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017, 131). By adapting this for commemorative purposes in burial grounds shared with settlers, the native Irish population were clearly stating their identity (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017); both children and adults were being commemorated in this distinctive style. Mytum (Citation2009) sees it as a specifically Catholic memorial, as the great majority of the Gaelic Irish population would have adhered to that faith and the iconography associated with ringed crosses in Ulster also has religious significance. A general decline in numbers from the mid-eighteenth century has been documented for these memorials (Mytum and Evans Citation2003; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017; Thomson Citation2006b) and slab headstones and ledger stones were becoming increasingly frequent for children from both Gaelic Irish and settler families.

Religious Iconography

Other differentiating factors may also emerge and show increases over time. Decorative inserts on stones, such as coats of arms, or religious iconography, such as the paschal lamb, crowing cocks, angel motifs and religious verses have been identified in small numbers in this study. A ‘Tree of Life’ was evident on the memorial of Geain Cadden, who died aged 17 years in 1776. The inclusion of such iconography on memorials, particularly religious symbols or statements associated with Catholicism (e.g. ‘Pray for the soul of … ’) became a statement of identity as gravestone forms became more similar and narrative in style and this is in keeping with findings for graveyard populations in west Ulster in general (Mytum Citation2006; Citation2009; Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017). Half of the graveyards surveyed on site visits contained these symbols, dating from the first half of the eighteenth century. It is debateable how representative these findings are, however, as location of previously recorded child memorials proved difficult in many of the sites visited due to very poor preservation or maintenance. It is also possible that families may not always have been able to exercise the choice; ‘God’s Acre’ at Tydavnet, Co. Monaghan, was subsequently owned by a Non-Conformist family who apparently did not permit monuments with an ‘invocation to prayer’ (O’Daly Citation1954, 45).

What may be perceived as Catholic iconography was present on the gravestones for a number of names associated with British ancestry (such as Campbell, McIntire and Ware) confirming that it is unwise to assume that settlers were uniformly Protestant. This may explain the unusual transitional style of memorial noted for one family of settler origin, that of the Jones children at Aghavea, Co. Fermanagh (see ). The gravestone form and the associated iconography suggest a Catholic settler family was adopting what could be seen more generally as ‘Catholic’ symbolism. It also indicates that transformation and transmission of funerary culture was not solely in one direction.

In previous studies (McKerr Citation2010; McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009) attention was drawn to the contrast between the simplicity of inscriptions on ringed crosses compared to the frequently lengthier ones on Planter ledgers in Derry City, suggesting this owed much to an oral tradition among the Gaelic Irish population, and perhaps the more limited space available. The contrast between eighteenth-century ‘Planter’ and ‘Gaelic Irish’ memorials is perhaps highlighted in two examples from Old Kilskeery, Co. Tyrone, shown in , where the ledger for Thomas Beacom and his son Robert, who died aged five years in 1754, bears a lengthy inscription and a crest. That for John O’Neill, who died aged four years in 1714, is in the form of a ringed cross with a short inscription and is beside the memorial for Con O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, presumably from the same family group. The latter however shows the existence of a substantial lower rectangular portion above ground level which continued the inscription (Ó Gallachair Citation1973). This at least raises the possibility that other such crosses, where the ground level has risen over the centuries, may carry more information than presently visible.

Commemorative Language

A small number of seventeenth-century inscriptions were in Latin, but the great majority were written in English. There were no memorials recorded for children in Irish, even though it remained the first language of people in many areas well into the nineteenth century (Mac Murchaidh Citation2014). Of the Irish inscriptions noted for adults, the earliest (1723) was recorded in Drumully, Co. Fermanagh, for Heimey Murphy (a phonetic rendering of the Irish form of the name James; Moore Citation1954). Another, for Rose Kenen in St Tierney’s, Co. Fermanagh, was dated to 1793 (Mulligan and McMahon Citation1984) and was inscribed ‘Gloar Da Yea’ (Gloir da Dia; ‘Glory to God’). Mytum (Citation1994, 262–265) noted that in Wales, there are also few early examples of Welsh language inscriptions despite a vigorous oral culture, perhaps reflecting the fact that fluency in English was seen as a measure of success and this may also be a significant factor in Ulster burial grounds. At a time when Gaelic Irish culture and influence was being suppressed, the form of the ringed cross, and later the religious iconography was a significant statement of identity and belonging (Parkinson and Murphy Citation2017), which could also be clearly ‘read’ by those who were not literate in either Irish or English. These differences would also seem to reflect a shift in perspective; by the middle of the eighteenth century, the dichotomy was much more clearly that of ‘Protestant’ and ‘Catholic’, as religious differences began to be perceived more rigidly as synonymous with ethnic identity and this also applied to memorials for children.

Creating Histories

As gravestone inscriptions became more narrative in style, and as English became the language of the majority, there were more opportunities to create or embellish family histories. Shirley (Citation1879, 295–296) in his survey of Donagh Old Graveyard, Co. Monaghan, observed examples of ‘stones erected in the eighteenth century with fictitious coats of arms … ’. By the eighteenth century, many settlers had established positions of power and wealth and, even for those without aristocratic ancestors, it was possible to make what might be seen as ‘lineage’ statements with their family memorials, particularly the merchants of Derry City whose ledger tombs were prominently placed around St Columb’s Cathedral (McKerr, Murphy, and Donnelly Citation2009). Mytum (Citation2004, 106) noted ‘[e]xternal memorials could now actively define and promote social identities through longer inscriptions that could be understood by a significant proportion of the population’; this was particularly true of the rising merchant classes (Mytum Citation2006). The inscription on the gravestone of the youngest named child in this study, Jean Vans, reads:

Here Lyeth the body of/ Elizabeth wife of Alexand/ er Vans of this city Mercht/ and daughter of Alderman/ Edward Brooker Mercht and/ some tyme mayor of this Citty/ who departed this life the/ 6th of August 1709 and in/ the 26th year of [her?] age/ and also Jean Daughter to/ the said Alexander and El/ izabeth who departed this life/ the 3rd March 1707/ aged 10 days (St Columb’s Cathedral records; McKerr Citation2010, 141).

Place, Power and Memory

In describing the ‘powerful dead’, Parker Pearson (Citation1993, 203) states that among the roles that societies have attributed to them are ‘legitimation of the social order, embodiments of land rights, martyrs to a holy cause, [and] guardians of ancestral traditions’. For many communities throughout history and prehistory, burials and territory are intrinsically linked (Bloch and Parry Citation1999). From the Medieval period onwards in Ireland it was common for members of high status Gaelic Irish families to be buried within the grounds of the principal churches of their territories (Fry Citation1999). At that time graves were generally not marked (McCormick Citation2007), certainly not with the type of permanent memorials which arose following the Plantation and, in effect, power resided within the place, rather than an individual’s burial space. Interment of high status family members in specific territorial burial grounds was therefore a means of controlling that power and gave the sites themselves particular meaning. Incoming elite families appropriated these prestigious burial places in due course (Tait Citation2002), and some of these graveyards are the locations of the earliest children’s memorials found in this study.

The Balfours of Lisnaskea, Co. Fermanagh, for example, were a Scottish settler family who chose to place their vault in the ancient Maguire church of St Ronan’s, Aghalurcher. In all, there are five elaborately carved ledgers complete with armorial inscriptions, dated to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and two-year-old ‘Marie Belfourd’, was buried there in 1672 () with the same degree of prominence as her adult relations. While smaller than those of the adults, her gravestone bears the Balfour coat of arms, and confirms her social identity both for contemporary society and for posterity (McKerr Citation2010). The gravestone is very striking, beautifully carved and when viewed in situ, somehow very emotive; the Balfours had two other children, who survived to adulthood (McKerr Citation2010), but the death of their two-year-old daughter was sufficiently meaningful for them to communicate their loss with a personalised memorial at a time when these were very rare for children, and scarce even for adults. However, as with other gravestones in the vault, it may have had additional socio-political significance. It lies within the traditional burial ground of the Maguires, the Gaelic lords in whose territory her family had settled and whose lands and castle they had acquired, a practice that Tait (Citation2002, 71) has described as a necessity ‘to “plant” ecclesiastical as well as secular space’. In effect, Marie – hardly out of infancy – had become an ‘ancestor’ (Lally and Moore Citation2011), whose gravestone signalled the territorial claims of her family.

Little Women

Some striking and very visible early memorials for Marie Belfourd and other girls from high status settler families were recorded during site visits. Rowan (Citation1979, 258) has also noted a memorial in St Anne’s church, Dungannon, Co. Tyrone, for Penelope Knox who died in 1696, aged 7 years; a descendant of her father would later become the Earl of Ranfurly, with an estate in territory formerly belonging to the O’Neills. It seems that the wealthy families of these girls were making a very public statement about personal loss, and often in ways which emphasised family status. These results also perhaps throw into relief the difficulties of defining childhood, given that the relationship between cultural and developmental perceptions is acknowledged to be variable across both time and place (Barclay and Reynolds Citation2016). Although 500 years is a relatively short period in archaeological terms, we cannot assume that childhood would have been defined in the same way as it is at present, or that this was not dependant on factors such as wealth and class. Certainly, in the early seventeenth century, children from very high status English or Scottish families may have been expected to make marriage contracts at a young age; the Countess of Atholl, some of whose children are buried in Donaghenry Old Graveyard, Co. Tyrone, was married in 1604 in her 13th year, for example, and her husband was in his 15th year (Cracrofts Irish Peerage). It seems likely (allowing for the scarcity of available data) that such early marriages were not the norm for the majority of the post-Plantation population from both Gaelic Irish and settler communities (Kennedy, Miller, and Currin Citation2012) although pre-1802 figures indicate that legally girls and boys could marry at 15 years (Morgan and Macafee Citation1984, 186). By the eighteenth century the average age at marriage for women in Ireland was estimated to be some two to five years lower than in other European countries, where women on average married in their mid-twenties (Dennison and Ogilvie Citation2014; Kennedy, Miller, and Currin Citation2012). For most children then, there was a substantial span of time between puberty and marriage, where they would still have been (both legally and in the familial sense) regarded as dependents.

There is perhaps an assumption that the loss of male children would be seen to have been more dynastically and economically significant, but the situation was likely to have been more complex. In terms of kinship structures, that of the Scots was traditionally regarded as agnatic, ‘dependant on an ancestor, either real or mythical, in the male line’ (Wormald Citation1981, 30). As with Gaelic Irish families, the line of descent was traced through males; women entered or left the group through marriage but kept their family name and this is apparent on a number of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century gravestones in the sites analysed, both for Scottish and Gaelic Irish families. Although alliances were created or strengthened by such marriages, kinship ties (the complex obligations which controlled social and political life) were not created with women’s families and, under Gaelic Irish laws, a woman’s family ‘never relinquished their rights and interests over her’ (Kenny Citation2006, 33). In contrast, the traditional English kinship model was cognatic, that is both maternal and paternal kin bonds were created by marriage.

This led to differences in the system of inheritance particularly for those women who were the sole heirs of the nobility. The basis for transmission of titles and property held in England and most of Scotland – unlike that for the Gaelic Irish – was primogeniture which meant that when there were no surviving male heirs, property could pass to daughters (Laurence Citation2009). Although the great majority of titles could only pass to males, in some instances where there were no surviving sons, the daughter of higher ranking English and Scottish families could inherit wealth and titles which then passed to her children, a situation where she would be described as a peer ‘in her own right’ (House of Lords Library Citation2022). In a time of high child mortality, survival of sons was as uncertain as that of any sisters they may have had, which then created a situation where the daughters of high status settlers may have been seen as potential heirs. The distinctive memorials to the girls of wealthy Planter families may therefore reflect their dynastic importance and signal the determination to mark out past and future ‘belonging’.

For the daughters of Gaelic Irish nobles, the situation was less clear. In terms of lineage and succession, under Gaelic law ‘there was no prospect of acquiring lands or titles by marrying a female heir’ (Kenny Citation2006, 34). This did not mean that women who married into powerful families, however, took a subservient role; marriages could create strong strategic alliances and the wives of lords could wield an ‘extraordinary amount of political power within Gaelic Ireland’ (Kenny Citation2006, 34). They could also bring property or money in the form of dowries, which would be considerable in high status marriages; for example, Gráinne O’Malley ‘brought a fleet of ships’ (Laurence Citation2009, 447). Although lands and titles could only pass to males, primogeniture or ‘legitimacy’ were not major factors in inheritance; marriages were regulated by Gaelic law rather than the sacraments of the church and it was not unusual for men to have concubines as well as a legally recognised wife (Kenny Citation2006, 32). This meant that wealthy men could have a large number of offspring, as with Con O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, whose gravestone in Old Kilskeery commemorates 21 children (Ó Doibhlin Citation1967; Ó Gallachair Citation1973, 85). It is also recorded that Turlough O’Donnell (Lord of Tirconnel) had ‘eighteen sons by ten different women and fifty-nine grandsons in the male line’ (Kenny Citation2006, 32). This flexibility in marital arrangements would obviously allow for a high probability of a suitable male heir, in that he need not necessarily be the first born, nor the child of a ‘legal’ wife.

Given the different social structures of Gaelic Ireland compared to settlers it then seems unlikely that the death of a child of either gender, however grievous to the family, would be perceived as the loss of a potential ‘heir’ in the same way that it would have been for high status English or Scottish families who were dependent on formal legitimacy. The graveyards surveyed in this study had very few surviving legible seventeenth-century gravestones, and only one of those identified was for a child with a Gaelic Irish name. Perhaps young children were considered to exist in the ‘private’, rather than the public, sphere of family life (Tait Citation2002, 68–69), a perception which then shifted with the cultural changes in memorialisation introduced by the Plantation.

Sorrow and Loss

Although we can attempt to analyse the social significance of monument types in terms of the wider community who shared the burial grounds, we can only catch glimpses of the grief and sense of loss felt by parents following the death of a child during this period. Although it is likely that parents managed their grief through the forms and rituals of religious belief, it is no longer assumed that they were inured to such loss, even when child mortality was very high (Barclay and Reynolds Citation2016; Murphy Citation2011).

Many of the gravestones commemorate several children from the same family, as with this early memorial from St Michael’s, Clonoe, Co. Tyrone:

Heir the bodis lyes of Marey Fals and Ann childrein of Eduard Chrichley who died all young. 1698 (Fee and Coyle [Citation1980] 1981, 65).

… his beloved children Roger and Rose Magui/ re and his posterity who both died February / 1756, Roger being 22 years and Rose being 12 years (Maguire Citation1958, 339).

Here lyeth ye body of Jane McMullen who departed this life January ye 15 1727/ Margaret and John & Christian and Mary Susanna and Daniel departed June ye 26 1752 children to William McMullen (Paterson MSS114, 173).

The inscriptions otherwise rarely give an insight into parental emotions, perhaps in part because of a separation of public and private mourning; the rise in permanent memorials during the eighteenth century reflected (or was driven by) an emerging change in cultural attitudes to expressing loss. As with other forms of material culture associated with children in the past, memorials and their inscriptions perhaps carry ‘fingerprints of emotion’ (Barclay and Reynolds Citation2016, 6), traces of the lived experiences of bereaved families. The textual content during this period tends to be biographical, and it is not until the nineteenth century that sentiment is more frequently expressed in the form of poems, prayers and terms of endearment (McKerr Citation2010; Rainville Citation1999). However, some inscriptions are more personal, as with the memorial for Gness Ledlie from St Columb’s Cathedral, Derry, which also includes her young grandson:

Affection and benevolence/ Governed her pious life/ living she was universally/ esteemed/ Now equally regretted/ James Ledlie her grandson aged/ 5 years died Christmas day 1762 (McKerr Citation2010, 152).

HERE LYETH THE BODY OF / JAMES HENERY WHO DE/ PARTED THIS LIFE JULY 12th / AGED 2 Y. 1M. 10 DAYS. ANNO DOM. 1771 (Paterson 1926, MSS 118).

Conclusions

Permanent memorials for children were found in all of the graveyards surveyed; although surviving (and legible) gravestones from the seventeenth century are rare, they existed initially for Planter and later for Gaelic Irish children, increasing in number throughout the eighteenth century. This mirrors the patterns observed for adult commemoration during the same period. Wealth and class would have been major restricting factors in the erection of permanent memorials. The number of Gaelic Irish names and Catholic iconography present on memorials at a time when economic conditions for Catholics were perceived as very harsh is an indication that people wished to commission what were often skilfully carved and beautiful memorials – both for children and adults (McCormick Citation1976).

For both communities, having children was not just an emotional commitment to the future, it was a means of passing on traditions, building or continuing communities, and also of securing rights to contested landholdings in an era where boundaries were being redrawn. Children were therefore ‘central to how communities defined themselves, negotiated their relationship with the divine and articulated emotional norms and values’ (Barclay and Reynolds Citation2016, 4) and this is true in death as well as in life. The differences in form, content and spatial arrangement between child memorials of the Gaelic Irish and settler communities have suggested that they were a means of creating and maintaining both individual and collective memory within a contested space, and also that place (the location of the gravestone) could be a focus not just of memory but also of power. Ultimately, however, for many families the loss of a child and, in some instances, the loss of many children, was also a personal grief, expressed for some through the memorials in this study. For many, raising inscribed memorials was not possible but, perhaps for all, there was some comfort, as the titular proverb states, in memory.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Royal Irish Academy who funded the initial research. Many individuals kindly helped with access to sites and shared data, including Sean Bardon, Armagh County Museum; Patricia Bogue (Donaghmore Historical Society); Aiden Fee (Stewartstown Historical Society); Aubrey Fielding MBE (St Columb’s Cathedral, Derry); Isobel Hyland /Friends of Shankill Graveyard; Professor Harold Mytum and Kate Chapman, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool; Willie O’Kane, Irish World; Kathleen Morrison (North of Ireland Family History Society); the late Roy Orr (St Augustine’s Church, Derry) and Peter Robinson (St Patrick’s Church, Coleraine). Thanks are also due to Libby Mulqueeny for help with the illustrations and to Tony Corey and HED for permission to use the photograph of Marie Belfourd’s gravestone. We are also extremely appreciative of the patience shown by Ivan Walton and members of the McKerr and Murphy families on the many outings made to the burial grounds included in the study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lynne McKerr

Lynne McKerr is a Visiting Scholar in the School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen’s University Belfast. She is a former Research Fellow in the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University, working in the fields of education, autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. As an archaeologist, her interests include the social history and archaeology of Irish National Schools and commemorative practices for children in the past and she has published widely with co-authors from a range of disciplines. She is the Monographs Editor for the Society for the Study of Childhood in the Past.

Eileen Murphy

Eileen Murphy is Professor of Archaeology in the School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen’s University Belfast. She is particularly interested in the use of approaches from bioarchaeology and funerary archaeology to help further understanding of the lived experiences of people in the past. Her recent books include co-editorship of Across the Generations: The Old and the Young in Past Societies (2018, with Grete Lillehammer) and Normative, Atypical or Deviant? Interpreting Prehistoric and Protohistoric Child Burial Practices (2023, with Mélie Le Roy). She is the founding editor of Childhood in the Past.

Notes

1 Irish proverb.

2 The surname Fitzpatrick (Drumlane Abbey; O’Reilly Citation1979) is included, as it is the only variant with the prefix ‘Fitz’ which is not of Norman origin, having been assumed by the Mac Giolla Phadraig sept in the sixteenth century (Bell Citation2021, 64).

References

Primary sources

- Armagh County Museum, The Mall East, Armagh, Co. Armagh:

- Paterson, T. G. F. “St Patrick’s Church of Ireland Cathedral Gravestone Inscriptions.” MSS 114.

- Paterson, T. G. F. “Mullavilly Churchyard Inscriptions.” MSS 115.

- Paterson, T. G. F. “Mullabrack Parish Notes.” MSS 118.

- Armagh Robinson Library, 43 Abbey St, Armagh, Co. Armagh:

- Pillow, R. “Inscriptions on Ancient Tombstones.” P0015943.

- Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, 2 Titanic Boulevard, Titanic Quarter, Belfast:

- McClay Papers D3672

- “Inscriptions from St Patrick’s Church Coleraine.” D3672/7.

- “Inscriptions from Aghadowey Church of Ireland – St Guaire’s.” D3672/8.

Private collections

- St Augustine’s Church, Derry: “Gravestone Inscriptions.”

- St Columb’s Cathedral Derry: “Gravestone Inscriptions.”

- Irish World: “Inscriptions at St Patrick’s Church, Coleraine, Co. Derry.”

- Irish World: “Inscriptions at Old Donaghmore Graveyard, Co. Tyrone.”

- Irish World: “Inscriptions at St Andrew’s Church, Killyman, Co. Tyrone.”

- Irish World: “Inscriptions at St Michael’s Church, Castlecaulfield, Co. Tyrone.”

- Irish World: “Inscriptions at St Paul’s, Killeeshil, Co. Tyrone.”

Internet publications

- Clonleigh Old Graveyard: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~donegal/oldclonleighgY.htm

- Cracroft’s Irish Peerage: https://web.archive.org/web/20220408112224/http://www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk/17th-century memorials in west Ulster: https://www.ancestryireland.com/plantation-ulster/?page_id = 187

Secondary sources

- Anon. 1997. “Inscriptions in Kill Cemetery, Kilnaleck.” Breifne 9 (33): 825–838.

- Baillie, F. A. 1984. Magheraculmoney Parish (A Parish History). Lurgan: LM Press.

- Barclay, K., and K. Reynolds. 2016. “Introduction: Small Graves: Histories of Childhood, Death and Emotion.” In Death, Emotion and Childhood in Pre-Modern Europe, edited by K. Barclay, K. Reynolds, and C. Rawnsley, 1–24. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bardon, J. 2005. A History of Ulster. Belfast: Blackstaff Press.

- Begley, A. 1978. “Graveyard Inscriptions at St. Anne’s Church of Ireland, Ballyshannon.” Donegal Annual 12 (2): 320–358.

- Begley, A. 2011. Ballyshannon: Genealogy and History. Ballyshannon: Carrickboy Publishing.

- Bell, R. 2021. The Book of Ulster Surnames. Belfast: Ulster Historical Society.

- Bloch, M., and J. Parry. 1999. “Introduction: Death and the Regeneration of Life.” In Death and the Regeneration of Life, edited by M. Bloch and J. Parry, 1–44. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bradfield, L., and R. Torrens. 2019. Aghadowey Parish Church Graveyard. genealogy.torrens.org/BannValley/church/AghadoweyCOI/Graves.html.

- Cairns, D. 2000. “The Object of Sectarianism: The Material Reality of Sectarianism in Ulster Loyalism.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 6 (3): 437–452.

- Christie, S. M. 2023. “A Childhood cut Short? The Mortuary Analysis of Subadult Decapitation Burials in Western Roman Britain.” In Normative, Atypical or Deviant? Interpreting Prehistoric and Protohistoric Child Burial Practices, edited by E. M. Murphy and M. Le Roy, 201–218. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

- Crichton, J. [Earl of Erne] 1896. “Account of Some Plantation Castles on the Estates of the Earl of Erne in the County of Fermanagh.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 2 (2): 73–85.

- Curl, J. S. 2000. The Honourable The Irish Society and the Plantation of Ulster, 1608-2000. Chichester: Phillimore and Company.

- Dennison, T., and S. Ogilvie. 2014. “Does the European Marriage Pattern Explain Economic Growth?” The Journal of Economic History 74 (3): 651–693. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050714000564

- Dethlefsen, E., and J. Deetz. 1966. “Death’s Heads, Cherubs and Willow Trees: Experimental Archaeology in Colonial Cemeteries.” American Antiquity 31 (4): 502–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/2694382

- Donnelly, C. 2004. “Masshouses and Meetinghouses: The Archaeology of the Penal Laws in Early Modern Ireland.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 8 (2): 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IJHA.0000043697.57999.d0

- Donnelly, C. 2007. “The Archaeology of the Ulster Plantation.” In The Post-Medieval Archaeology of Ireland, 1550-1850, edited by A. Horning, R. O. Baoill, C. Donnelly, and P. Logue, 37–50. Dublin: Wordwell Ltd.

- Donnelly, C. J., and E. M. Murphy. 2018. “Children’s Burial Grounds (Cillíní) in Ireland: New Insights Into an Early Modern Religious Tradition.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Childhood, edited by S. Crawford, D. Hadley, and G. Shepherd, 608–628. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Donnelly, C., E. Murphy, D. McKean, and L. McKerr. 2020. “Migration and Memorials: Irish Cultural Identity in Early Nineteenth-Century Lowell, Massachusetts.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 24 (2): 318–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00521-y

- Donnelly, E. E. 1993. A History of the Parish of Tullanisken. Dungannon: Privately published.

- Donnelly, J., and C. Dillon. 1989. “St Jarlath’s Cemetery, Clonfeacle: Inscriptions and Index of Names.” Dúiche Néill 4: 51–69.

- Duffy, P. J., D. Edwards, and E. FitzPatrick. 2001. “List of Abbreviations and Conventions.” In Gaelic Ireland c. 1250-c.1650: Land, Lordship and Settlement, edited by P. J. Duffy, D. Edwards, and E. FitzPatrick, 15–17. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Evans, E. E. [1957] 1976. Irish Folk Ways. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Fagan, B. M. 2000. The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850. New York: Basic Books.

- Fee, A., and H. Coyle. [1980] 1981. “Gravestone Inscriptions Saint Michael's, Clonoe.” Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society 10 (1): 63–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/29740948

- Foster, R.F. 1989. “Ascendancy and Union.” In The Oxford History of Ireland, edited by R. F. Foster, 134–173. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Francis, D., L. Kelleher, and G. Neophytu. 2005. The Secret Cemetery. London: Routledge.

- Friends of Shankill Graveyard. 2022. “Shankill Graveyard: Inscriptions”. [Pre-publication data].

- Fry, S. L. 1999. Burial in Medieval Ireland, 900–1500. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Gaffney, B. 1994. “Inscriptions from Denn old Cemetery.” Breifne 30: 497–513.

- Gallogly, D. 1963. “Inscriptions in Magherintemple Cemetery.” Breifne 2 (6): 248–253.

- Gillespie, R. 2006. Seventeenth-Century Ireland: Making Ireland Modern–The Quest for a Settlement. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd.

- Graham, B. J., and L. J. Proudfoot. 1993. “A Perspective on the Nature of Irish Historical Geography.” In An Historical Geography of Ireland, edited by B. J. Graham and L. J. Proudfoot. London: Academic Press

- Hancox, P., H. Magowan, D. Hamilton, and C. Murtagh. 2009. “St Mark’s Church of Ireland, Ballymore, Tandragee, Co. Armagh.” [ Unpublished record of inscriptions, North of Ireland Family History Society].

- Hewson, E. 2006a. Old Irish Graveyards: County Cavan Part I. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2006b. Old Irish Graveyards: County Cavan Part IV. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2007a. Fermanagh Graveyards Part IV. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2007b. Fermanagh Graveyards Part V. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2007c. Fermanagh Graveyards Part VI. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2008a. Donegal Graveyards Part I. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2008b. Donegal Graveyards Part II. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Hewson, E. 2008c. Donegal Graveyards Part IV. Wem: Kabristan Archives.

- Horning, A. 2007. “Introduction: Of Time, Place and Landscape.” In The Post-Medieval Archaeology of Ireland, 1550-1850, edited by A. Horning, R. O. Baoill, C. Donnelly, and P. Logue, 3–6. Dublin: Wordwell Ltd.

- House of Lords Library. 2022. “Women, Hereditary Peerages and Gender Inequality in the Line of Succession.” Accessed 01/03/2023 from https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/women-hereditary-peerages-and-gender-inequality-in-the-line-of-succession/.

- Hunter, R. J. 2012. The Ulster Plantation in the Counties of Armagh and Cavan, 1608-1641. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation.

- Johnston, J. 2004. “The Towns of Magherastephany Barony, County Fermanagh.” In Fermanagh: History and Society, edited by E. Murphy and W. Roulston, 551–570. Dublin: Geography Publications.

- Johnston, J. I. D. 1972. Clogher Cathedral Graveyard. Omagh: Graham.

- Kelleher, O. 2022. “Grave Technology Set to Tell Stories of the Dead via QR Codes on Headstones.” Irish Mirror 22nd November. https://www.irishmirror.ie/news/irish-news/grave-technology-set-tell-stories-28557074.

- Kennedy, L., K. A. Miller, and B. Currin. 2012. “People and Population Change, 1600–1914.” In Ulster Since 1600: Politics, Economy and Society, edited by L. Kennedy and P. Ollerenshaw, 58–73. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kenny, G. 2006. “Anglo-Irish and Gaelic Marriage Laws and Traditions in Late Medieval Ireland.” Journal of Medieval History 32 (1): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2005.12.004