Abstract

We conducted a survey of attitudes towards antimicrobial use and awareness of antimicrobial resistance among turkey and rabbit farmers (N = 117 and N = 41, respectively) in Italy’s utmost turkey- and rabbit-producing region. We found either similarities or significant differences between these two livestock sectors. Most farmers of both groups (72% of turkey farmers vs 76% of rabbit farmers) reported that antimicrobials are properly used in their farms. Almost three-quarters of the farmers reported that antimicrobials solve the health problem treated for. However, 47% of turkey farmers and 78% of rabbit farmers reported that antimicrobial use could be decreased, with a 20–30% reduction being the most frequently chosen range. Genetic improvement was reported to be the main factor able to reduce antimicrobial use in turkeys, whereas improvements in feed quality and microclimate were the main factors for rabbits. Most farmers reported that high antimicrobial use may affect the quality of meat products and be hazardous to human health, but they also reported that antimicrobial resistance is mainly related to antimicrobial use in humans. In conclusion, turkey and rabbit farmers have a generally positive opinion on veterinary antimicrobial use, but also low levels of awareness of the negative impact on public health. Economic and structural factors of rabbit production industry may explain the differences observed. Farm veterinarians will be crucial to support farmers’ education and the expected transition to lower antimicrobial use while maintaining high animal health/welfare standards.

47% of turkey vs. 78% of rabbit farmers thought that antimicrobial use can be decreased

A 20–30% reduction of antimicrobials was the most frequently supposed range

Turkey and rabbit farmers showed a low level of awareness of the negative impact of antimicrobial usage in their farms on human health

Highlights

Introduction

The growing burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is of major public health concern worldwide (World Health Organization Citation2015a). In 2011, the European Commission presented a plan (updated in 2017) for intensifying AMR surveillance and antimicrobial use (AMU) in animals and humans (European Commission Citation2011, Citation2017). The first plan comprised 12 concrete actions to recommend the prudent use of antimicrobials, five of which pertain to AMU in veterinary practice. The focus on food-producing animals is motivated by reports (ECDC et al. Citation2015) showing that, overall, AMU is a bigger issue in livestock relative to humans, and that veterinary AMU is favouring the development of AMR in bacterial populations. The link between AMU in livestock and AMR in humans is then due to resistant bacteria selected by pressure of veterinary AMU being transferred to humans through exposure to animals, foods and the environment. A recent scientific opinion of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) also highlights the need to follow the recommended AMU-reducing actions, including interventions focussing on improving farmers’ education and awareness regarding herd hygiene, biosecurity and husbandry practices (EFSA Citation2017).

In the general population, a recent World Health Organisation (WHO) survey evidenced some alarming signs of misinformation on the topic, for example, that most people incorrectly believe that viral infections can be treated with antibiotics, that they should stop taking antibiotics as soon as they feel better (without therefore completing the therapy), and that AMR is a problem only for people taking antibiotics regularly (World Health Organization Citation2015b). A few studies in the last years have investigated farmers’ perception towards AMR and prudent AMU. A pilot study among dairy farmers in the United States of America (USA) showed low levels of awareness that overuse of antimicrobials in animals could result in AMR development, revealing the need for the development of an educational programme (Friedman et al. Citation2007). In a recent survey from different EU countries, farmers that were more aware of AMR estimated their own AMU as being lower than their less aware counterparts (Visschers et al. Citation2015), indicating that a higher perception towards AMR can result in more responsible AMU. However, overall awareness of AMR was not particularly high. The authors concluded that financial policies are most likely to influence AMU, as farmers do seem to worry about having fewer revenues depending on their AMU levels than about favouring AMR development per se. This agrees with the observed decrease in AMU among Denmark’ pig farms after the introduction of the ‘Yellow Card’ intervention (Jensen et al. Citation2014). Specifically, this policy requires that whether the antimicrobial reduction is not reached after nine months from a first order, a strategy developed by a veterinarian (e.g. sampling and testing, vaccination protocols, management changes, etc.) has to be paid by the farmer.

Previous studies also emphasised the different attitudes to herd health management as related to the livestock sector in question, for example, pig farmers seem to perceive biosecurity and staff training to be more important than sheep farmers do (Garforth et al. Citation2013).

Here we present the results of a study aiming to investigate the attitudes towards AMU and the awareness of AMR among Italian meat turkey and meat rabbit farmers. These two livestock sectors have a common need to increase biosecurity standards, a generally high AMU (Falcão-e-Cunha et al. Citation2007; EMA Citation2017), and alarming rates of AMR (EFSA and ECDC Citation2016; Agnoletti et al. Citation2017). Moreover, antimicrobial treatments in turkeys and rabbits are usually orally administered, possibly resulting in under-dosing of large groups of animals in a herd, which may contribute to AMR development more incisively (EFSA and ECDC Citation2016). Furthermore, in comparison to other livestock, meat rabbits have fewer vaccines available for disease prevention (Agnoletti Citation2012). The ultimate goal of this study was therefore to identify turkey and rabbit farmers’ educational needs about the AMU and AMR to be targeted in future interventions.

Material and methods

Procedure

Two paper-and-pencil surveys among meat turkey and meat rabbit farmers were conducted in North-Eastern Italy. Two self-administered questionnaires (SAQ) were designed combining expertise from veterinary and social sciences and were based on available literature (Lavrakas Citation2008; Visschers et al. Citation2015; Visschers et al. Citation2016).

The questionnaire for turkey farmers was administered to all participants (n = 176) during five educational meetings organised by a major poultry industry from May to June 2016 in Veneto Region. The events were part of the compulsory education programme organised by the poultry industry for the affiliate turkey farmers and were focussed on the application of biosecurity measures in the poultry sector. The questionnaire for rabbit farmers was administered to all participants (n = 45) during one free educational meeting organised by the public sector (IZSVe) in December 2015 in Veneto Region. The event was focussed on the application of biosecurity measures in the meat rabbit sector and specifically addressed to rabbit farmers. Both the questionnaires were administered to participants before the meeting started and the filling lasted around 15 minutes. Ethical guidelines for the inclusion of human subjects in research were followed and response to the questionnaire constituted the participants' consent. Written information was included in the questionnaire that data would have been treated with respect of privacy and confidentiality, in compliance with Italian Legislative Decree n. 196 of 30 June 2003 on personal data protection.

In Italy, Veneto is the first producer of rabbit meat and accounts for 177 rabbit farms (Regione del Veneto Citation2018) out of 795 with more than 500 does at the national level (Unaitalia Citation2018). Moreover, 379 turkey farms are present out of 733 with more than 1000 animals at the national level (Ministero della Salute Citation2018). In contrast to turkey farms, only a minor part of rabbit farms are structured as a vertically integrated farming industry. Both questionnaires consisted of the same series of closed-ended questions except for a few questions related to the specific farming systems in question (Table ). In total the turkey farmers’ questionnaire was composed of 28 questions, whereas the rabbit farmers’ questionnaire of 30. The questions included in the present study are reported in the Supplementary material.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the two samples of respondents and characteristics of their farms, both expressed with percentage values (%, N = 117 turkey farmers and 41 rabbit farmers from North-Eastern Italy).

The two structured surveys covered the following topics:

Farmers’ usage and opinion on antimicrobials

Farmers’ perception of AMR

Training wishes (farmers’ interest in the topic)

Personal data

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced for all variables to describe the general picture of respondents’ opinions and perceptions towards AMU and AMR. In the text, rounded percentages for both respondents’ groups were reported. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences in the distribution of categorical variables. The Mann–Whitney test was used to assess differences in the distribution of ordinal variables expressed on a 1 to 10 Likert scale. Data were processed using SPSS software (version 21.0) for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (α = 0.05).

Results

Respondents’ characteristics

Overall, 221 questionnaires were administered (176 to turkey farmers and 45 to rabbit farmers).

A total of 158 (71%) questionnaires completely filled in were included in the analysis: 117 from turkey farmers and 41 from meat rabbit farmers. The 29% of the collected questionnaires were lacking and this was probably due to the time limits given to the participants for filling in the questionnaire (around 15 minutes).

The sample population was mainly composed by males (turkey farmers = 85%, rabbit farmers = 95%) between 41 to 55 years old (turkey farmers = 46%, rabbit farmers = 46%), having the high school diploma (turkey farmers = 39%, rabbit farmers = 45%) and carrying out the farmer’s profession for more than 25 years (turkey farmers = 46%, rabbit farmers = 39%). Detailed respondents’ characteristics and farms information are described in Table .

Farmers’ usage and opinions of antimicrobials

Farmers’ perceptions towards AMU are summarised in Table . The majority of either turkey or rabbit farmers reported that antimicrobials are used fairly in their farms, in line with veterinarians’ recommendations (turkey farmers = 72%, rabbit farmers = 76%). Almost three-quarters of the respondents (turkey farmers = 74%, rabbit farmers = 73%) reported that AMU in their farms often solves the problem; no one reported that AMU seldom solves the problem and only one turkey farmer (1%) reported that AMU never solves the problem.

Table 2. Farmers’ data on their perception of antibiotic usage and AMR in farms (%Table Footnotea, N = 117 turkey farmers and 41 rabbit farmers from North-Eastern Italy).

With regard to the economic burden posed by AMU in farms, most turkey farmers (55%) reported that this is light, while most rabbit farmers (49%) reported that such burden is heavy. Forty-seven percent of turkey farmers and 78% of rabbit farmers reported that AMU could be decreased, and Fisher’s exact test showed that this difference was statistically significant (p=.001). Those responding positively were then asked how much it would be possible to decrease AMU in their farms, and a reduction of 20–30% was the most frequently chosen range (turkey farmers = 38%, rabbit farmers = 31%).

The main factors that may contribute to veterinary AMU reduction in the short term according to farmers’ opinion were also investigated: most turkey farmers reported animal genetic improvement to be the main factor (50%), whereas improvements in the quality of feed and/or raw materials and housing microclimate conditions were the main factors indicated by the rabbit farmers (63%). Finally, most respondents reported that AMU may heavily affect the quality of meat products (turkey farmers = 47%, rabbit farmers = 39%), and that AMU in farms may affect human health (turkey farmers = 56%, rabbit farmers = 63%); Fisher’s exact test showed that this difference was not statistically significant.

Farmers’ perception towards AMR

The majority of respondents reported to be aware of what AMR is (turkey farmers = 70%, rabbit farmers = 85%). These respondents (82 turkey farmers and 35 rabbit farmers) were asked to assess their level of knowledge about AMR on a 1 to 10 Likert scale (1 = very low, 10 = very high). The rabbit farmers perceived themselves to be more informed on the AMR issue than turkey farmers did (turkey farmers median = 5.5, rabbit farmers median = 7). The difference between the two groups distributions was statistically significant according to the Mann–Whitney test (p=.024).

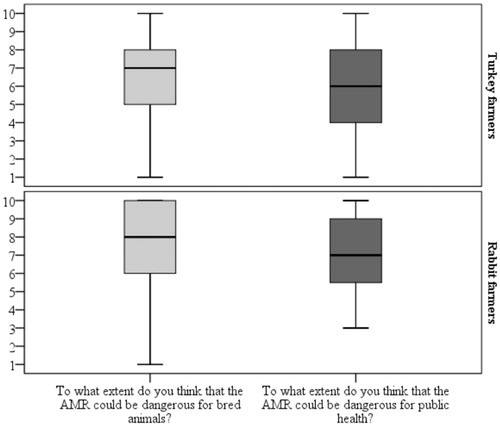

Moreover, those farmers reporting to know what AMR is, were also asked to what extent they thought that this issue could be dangerous for animal and public health (assessment on a 1 to 10 Likert scale, 1 = not dangerous at all, 10 = highly dangerous). The distribution of the scores assigned by rabbit farmers was, in both variables, different from the distribution of scores attributed by turkey breeders (Figure ). These differences were statistically significant (p=.012 and p=.032 respectively). Finally, regarding the most important factor contributing to AMR in humans (Table ), the majority of respondents selected the option ‘the use of antibiotics administered to humans when a health issue occurs’ (turkey farmers = 60%, rabbit farmers = 60%).

Training wishes

In the last part of the questionnaire, the interest of the respondents in enhancing their knowledge of AMR was investigated (Table ). All farmers responded to this question, regardless of their previous knowledge on AMR. Both turkey farmers and rabbit farmers reported that they are rather interested in deepening their knowledge of the issue (turkey farmers = 60%, rabbit farmers = 51%). Yet, among rabbit farmers, 44% reported to be very interested in doing so and none to be not interested at all, whereas among the turkey farmers only 29% reported to be very interested and 5 respondents (4%) were not interested at all. Those showing interest in enhancing their knowledge of AMR (n = 153, response option ‘very interested’, ‘quite interested’, ‘little interested’) were thus asked to specify how they would have preferred to receive more information. The turkey farmers identified the farm veterinarian as the preferable source of such information (48%), whereas the rabbit farmers mainly indicated classroom-based training courses/meetings (56%).

Table 3. Farmers’ training wishes (%, N = 117 turkey farmers and 41 rabbit farmers from North-Eastern Italy).

Discussion

Although AMR is a topic of growing concern for public and animal health (Schwarz et al. Citation2001; World Health Organization Citation2014), only a few studies have assessed farmers’ perceptions to AMR in Europe. This is remarkable as the farmers, along with the veterinarians, are the ‘gatekeepers’ of veterinary AMU and can make a difference in limiting AMR development. Italy’s public health authorities need to implement intervention strategies based on AMR risk perception as to maximise their effectiveness in lowering AMU in farms. Although the farmers participating in the survey reported to be aware of AMR (turkey farmers = 70%, rabbit farmers = 85%), the self-evaluation of the level of knowledge was rather low, particularly among meat turkey farmers. Previous studies have showed that farmers’ perceptions to AMR differed significantly depending on the production system (and its level of integration) in question. Data were in line with those from a study among New Zealand dairy farmers (McDougall et al. Citation2017), but quite different from those of USA dairy (Friedman et al. Citation2007) and pig (Moreno Citation2014; Visschers et al. Citation2016) farmers, which were mostly unaware of this issue. Most farmers understood that a high use of antimicrobials may heavily affect the quality of the meat produced (turkey farmers = 75%, rabbit farmers = 68%) as well as be hazardous to human health (turkey farmers = 56%, rabbit farmers = 63%). However, data also showed that farmers attribute the development of AMR mainly to AMU for human health problems (turkey farmers = 60%, rabbit farmers = 60%) more than to veterinary AMU (turkey farmers = 17%, rabbit farmers = 37%). This finding is in accordance with the WHO survey (World Health Organization Citation2015b) where the majority of respondents indicated the need for a more rational AMU in human medicine as the first priority action.

As reported by Visschers et al. (Citation2016) from other EU Member States, also most Italian farmers reported to use antimicrobials properly in their farms. However, farmers also indicated that the use of antimicrobials could be decreased, in particular in the meat rabbit sector (47% of the turkey farmers and the 78% of the rabbit farmers). This implies that, in accordance to what evidenced in pig farms (Visschers et al. Citation2016), most farmers do accept that turkeys and rabbits can stay healthy without a high AMU levels. Moreover, animal genetic improvement was perceived as the main factor that can contribute to decrease AMU in turkeys, while feed and microclimate were considered striking aspects for rabbits.

The difference between the two sectors suggests increased awareness of the particularly high AMU in the rabbit sector, possibly perceived by the farmers especially in term of high costs. Conversely, in the integrated poultry production sector, farmers receive medicines as part of contract-guaranteed veterinary services. Moreover, integrated companies might also provide more efficient support and education campaigns to farmers in order to achieve specific targets on drug use reduction to satisfy consumer’s demands. This hypothesis agrees with the results of Wei and Aengwanich (Citation2012), which suggested that biosecurity levels of company-owned poultry farms were better than those of individual farms due to a harmonised policy of investments in farmers’ education.

Our data suggest that the respondents are generally interested in enhancing their knowledge of AMR. Both farmer groups indicated, with similar percentages (42–48%), that the farm veterinarian would be the preferred source of information. Several studies have reported veterinarians to be the preferred sources of information regarding farming practices in general (Friedman et al. Citation2007; Garforth et al. Citation2013), as well as AMU in particular (McDougall et al. Citation2017; Visschers et al. Citation2015; Visschers et al. Citation2016). However, rabbit farmers seemed also to prefer classroom-based training and meetings (56% vs. 35%), whereas turkey farmers were more orientated to readable documentations (books, leaflets, brochures) (26% vs. 7%). This difference may be due to a higher education level of turkey farmers compared to rabbit farmers (8% vs. 3% had a bachelor degree or higher education), rather than to a different age range. It has to be taken into account that the sample of turkey farmers was taken within a compulsory education programme (i.e. all affiliate farmers had to take part), while rabbit farmers jointed freely within an event organised by the public sector. This difference could be a limitation of the study and further investigations on rabbit farmers’ population will be needed.

Conclusions

In contrast with previous surveys on other livestock farmers, rabbit and turkey farmers seem to be aware of a high AMU and agree that the reason is intrinsically connected with these specific production systems, either in term of animal genetics or production environments. This study also highlighted a generally low level of awareness of the negative impact of such AMU, that is AMR, on both public and animal health. This seems to be driven mostly by economic reasons (i.e. antimicrobial treatment costs), particularly for livestock productions with low integration and under lower profitable conditions, such as meat rabbits. Integrated livestock production systems may therefore provide more opportunities for proper farmers’ education and control on AMU. Nonetheless, the role of the farm veterinarian will be crucial in the years to come in order to support farmers’ education and the expected transition to lower AMU, while maintaining high animal health and welfare standards.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agnoletti F. 2012. Update on rabbit enteric diseases: despite improved diagnostic capavity, where does disease control and prevention stand? In Proc. 10th World Rabbit Congress, September 3 - 6, 2012. Sharm-El-Sheikh, Egypt, 1113- 1127.

- Agnoletti F, Brunetta R, Bano L, Drigo I, Mazzolini E. 2017: Longitudinal study on antimicrobial consumption and resistance in rabbit farming. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 51:197–205.

- European Commission. 2011. Action Plan Against the rising threats from Antimicrobial Resistance. Accessed on August 6, 2018. http://ec.europa.eu/health/amr/sites/amr/files/communication_amr_2011_748_en.pdf

- European Commission. 2017: A European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Accessed on August 6, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/health/amr/sites/amr/files/amr_action_plan_2017_en.pdf

- ECDC, EFSA, EMA. 2015. ECDC/EFSA/EMA first joint report on the integrated analysis of the consumption of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from humans and food-producing animals. EFSA J. 13:1–114.

- EFSA, ECDC. 2016. The European Union Summary Report on antimicrobial resistance in Antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in the European Union in 2014. EFSA J. 14:4380.

- EFSA. 2017. EMA and EFSA Joint Scientific Opinion on measures to reduce the need to use antimicrobial agents in animal husbandry in the European Union, and the resulting impacts on food safety (RONAFA). EFSA J. 15:4666.

- EMA. 2017: Sales of veterinary antimicrobial agents in 30 European countries in 2015. Trends from 2010 to 2015. Seventh ESVAC report. Accessed on August 6, 2018 http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2017/10/WC500236750.pdf

- Falcão-e-Cunha L, Castro-Solla L, Maertens L, Marounek M, Pinheiro V, Freire J, Mourão JL. 2007. Alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters in rabbit feeding: a review. J World Rabbit Sci. 15:127–140.

- Friedman DB, Kanwat CP, Headrick ML, Patterson NJ, Neely JC, Smith LU. 2007. Importance of prudent antibiotic use on dairy farms in South Carolina: a pilot project on farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices. Zoonoses Public Health. 54:366–375.

- Garforth CJ, Bailey AP, Tranter RB. 2013. Farmers’ attitudes to disease risk management in England: a comparative analysis of sheep and pig farmers. Prev Vet Med. 110: 456–466.

- Jensen VF, de Knegt LV, Andersen VD, Wingstrand A. 2014. Temporal relationship between decrease in antimicrobial prescription for Danish pigs and the ‘Yellow Card’ legal intervention directed at reduction of antimicrobial use. Prev Vet Med. 117:554–564.

- Lavrakas PJ. 2008. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- McDougall S, Compton CWR, Botha N. 2017. Factors influencing antimicrobial prescribing by veterinarians and usage by dairy farmers in New Zealand. New Zeal Vet. J. 65:84–92.

- Ministero della Salute. 2018. Sistema Informativo Veterinario. Accessed on August 6, 2018. https://www.vetinfo.sanita.it

- Moreno MA. 2014. Opinions of Spanish pig producers on the role, the level and the risk to public health of antimicrobial use in pigs. Res Vet Sci. 97:26–31.

- Regione del Veneto. 2018. Banca Dati Regionale dell’Anagrafe Zootecnica. Accessed on August 6, 2018. http://www.crev.it

- Schwarz S, Kehrenberg C, Walsh TR. 2001. Use of antimicrobial agents in veterinary medicine and food animal production. Int J Antimicrob Agent. 17:431–437.

- Unaitalia. 2018. [CrossRef][10.3301/IJG.2017.23] http://www.unaitalia.com/sezioni/dati-e-statistiche

- Visschers VHM, Backhans A, Collineau L, Iten D, Loesken S, Postma M, Belloc C, Dewulf J, Emanuelson U, grosse Beilage E, et al. 2015. Perceptions of antimicrobial usage, antimicrobial resistance and policy measures to reduce antimicrobial usage in convenient samples of Belgian, French, German, Swedish and Swiss pig farmers. Prev Vet Med. 119:10–20.

- Visschers VHM, Backhans A, Collineau L, Loesken S, Nielsen EO, Postma M, Belloc C, Dewulf J, Emanuelson U, grosse Beilage E, et al. 2016. A comparison of pig farmers’ and veterinarians’ perceptions and intentions to reduce antimicrobial usage in six European countries. Zoonoses Public Health. 63:1–11.

- Wei H, Aengwanich W. 2012. Biosecurity evaluation of poultry production cluster (PPCs) in Thailand. Int J Poult Sci. 11:582–588.

- World Health Organization. 2014. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Accessed on August 6, 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. 2015a. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Accessed on August 6, 2018. http://www.wpro.who.int/entity/drug_resistance/resources/global_action_plan_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. 2015b. Antibiotic resistance: multi-country public awareness survey. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Accessed on August 6, 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/194460/1/9789241509817_eng.pdf?ua = 1