ABSTRACT

Objective

To explore emergent values for community-based peer support in three projects and use of peer research methodology.

Background

Peer support refers to the support people with shared lived experiences provide to each other. Its roots are in the civil rights movement, providing alternatives to clinical treatments. This method of support is delivered in different settings, with varying degrees of structure. In this paper, it includes shared experience of mental health issues.

Methods

We reviewed interview data from two evaluations and one development project - mental health (n = 69), women-only (n = 40), and maternal mental health (n = 24), respectively. Each project used peer research methods. Peer support values from each project were compared, along with reflections from mostly peer researchers who worked on them (n = 11).

Results

Six peer support values emerged and were found to be identifiable and applicable in different contexts. Decisions on facilitation and leadership varied across projects and generated some concerns over professionalisation, including non-peer leadership. Frameworks were viewed as broadly useful, but peer support is heterogenous, and peer researchers were concerned about over-rigid application of guidance.

Discussion

We propose caution applying frameworks for peer support. Values must remain flexible and peer-led, evolving in new contexts such as COVID-19. Evaluators have a responsibility to consider any potentially negative consequences of their work and mitigate them. This means ensuring research outputs are useful to the peer support community, and knowledge production is based upon methodologies, such as peer research, that complement and are consistent with the values of peer support itself.

Background

Peer support is recognised as reciprocal social, practical, and emotional support between two or more people, based on sharing knowledge (Mead & MacNeil, Citation2006). In mental health settings, the concept of ‘peerness’ (Silver & Nemec, Citation2016) may be linked to mental health experiences. However, peerness can also be drawn from wider experiences, characteristics, or interests including, gender, cultural heritage, disability and/or parenthood (Watson & Meddings, Citation2019). Expertise based on lived experience is a crucial element of all peer support approaches, whether delivered online, in groups or one-to-one (Basset, Faulkner, Repper, & Stamou, Citation2010).

Peer support in the Global North grew from civil rights, grassroots movements, providing different approaches to clinical treatments (Faulkner & Basset, Citation2012; Mead & MacNeil, Citation2006). User-led groups and organisations in the UK have played a critical role in advancing peer support as an alternative to public mental health services (Faulkner & Kalathil, Citation2012). In doing so, they elevated personal narratives and experiences into a form of collective, symbolic, and political power (Dillon & Hornstein, Citation2013; Noorani, Citation2013). Peer support also occurs organically and has been developed for different marginalised communities (O’Hagan, Cyr, McKee, & Priest, Citation2010). It is often found in the UK voluntary sector and is sometimes labelled as community peer support. The approach is also found in public mental health inpatient and community services (Adame & Leitner, Citation2008), and peer support worker roles have emerged in many countries (Lloyd-Evans et al., Citation2014). Varied terms are used including intentional or formal peer support (Ibrahim et al., Citation2020), yet there are challenges in statutory settings (Faulkner, Citation2020). Some argue it is a co-option of a concept developed to challenge psychiatric dominance, which may assimilate and homogenise experiential knowledge (Beresford & Russo, Citation2016; Woods, Hart, & Spandler, Citation2019). Professionalisation is seen as a risk to the mutuality of peer support (Faulkner & Basset, Citation2012). Further, it has been suggested that peer support workers are being employed as a low-cost, undervalued workforce to gatekeep access to clinical mental health care (Beresford & Russo, Citation2016; Voronka, Citation2015).

Peer support values have been defined and discussed in academic literature (Gillard et al., Citation2017) and by the voluntary sector (National Survivor User Network (NSUN), Citation2017; Together for Mental Wellbeing, Citation2015). The values of shared experience, choice and control, mutuality, reciprocity, safety, hope and empowerment have been identified across peer support types (Faulkner, Citation2020). However, peer-reviewed research on peer support in the not-for-profit sector is more limited (Gillard, Citation2019). This paper explores peer support values from three community-based programmes that were led and facilitated by UK voluntary sector charities and the use of peer research methods in evaluating them.

Method

Summary of original projects

We completed two evaluations (Billsborough et al., Citation2017; The Women-Side-by-Side evaluation team writing collaborative, Citation2020) and a development project (Mind & The McPin Foundation, Citation2019). (see ). Each was underpinned by a qualitative, peer research methodology (Lushey, Citation2017) and carried out mostly by people who had been involved personally in peer support. The three teams drew on their lived-experience to facilitate in-depth critical analysis of the data.

Table 1. Information about the evaluated peer support projects.

Side-by-Side worked in nine areas of England. Multi-stakeholder consultations and 69 interviews across 46 new projects and one online platform were undertaken to identify a common set of values. Women-Side-by-Side consisted of 114 observations of peer projects and interviews with 40 women across England and Wales. The evaluation, in part, examined how the Side-by-Side values related to women's peer support, with a focus on modifications required to work in a gendered, trauma-informed way. The Maternal Mental Health project developed a perinatal quality assurance framework and explored the Side-by-Side values in the maternal/perinatal context. This included 24 interviews, three consultation events, and two focus groups with people involved in providing and receiving maternal mental health peer support across the UK.

Secondary analysis

The three projects synthesised for this work were evaluations and service development projects, so no ethical approval was required at the time they were undertaken. However, all work was completed following recognised ethical principles.

The research team for this paper consisted of peer researchers from the initial three projects. This team had access to both the original datasets and the three project reports. Secondary analysis was undertaken, with original datasets and reports reviewed using a deductive approach to explore the values described in the peer support value pyramids (). A table was created to highlight examples of the values within the three datasets.

Peer reflections

For this paper, we asked people who worked on these evaluations to reflect on their work and experience of using a peer research methodology in evaluating peer support. Of 15 people approached, 11 provided oral and written reflections. A majority of these people had peer researcher or peer facilitator roles on the original projects. Three worked across all three projects, three on Side-by-Side, seven on Women-Side-by-Side, and two on the Maternal Mental Health project. These written reflections were thematically analysed. The themes identified were reviewed collectively in team-based groups (via video conferencing due to pandemic restrictions). This allowed the team to finalise the themes collaboratively. The method undertaken was as follows:

Three researchers reviewed written reflections for key and sub-themes.

Key themes and sub themes were summarised on PowerPoint and presented to the authors of the reflections for approval and/modification.

Three online group discussions were undertaken (n = 13), one per project. Discussions were reflexive, exploring positionality and testing assumptions. The decision-making in these groups followed a model of consent rather than consensus (Rau, Citation2021).

Themes were finalised through further group discussion and analysis by three peer researchers.

These formed the reflective findings presented in this paper.

Results

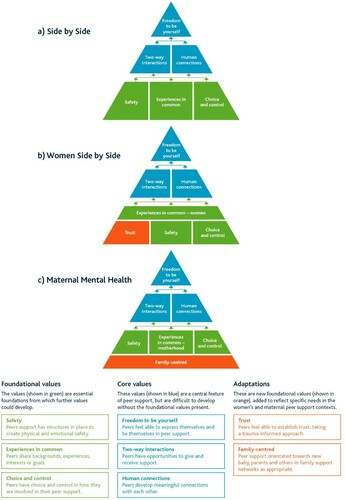

The Side-by-Side evaluation team identified six interconnected and multifaceted values in community-based peer support. A pyramid was developed to visually represent these values, in which ‘Experience in Common’, ‘Choice and Control’, and ‘Safety’ were conceptualised as essential foundations from which another three values could develop (See a). The pyramid was created to support new and emerging groups to develop their own ways of working around a core message of what the data told us ‘good’ peer support needs to flourish. How people chose to organise peer support across five dimensions (see , as an example of this application in one context), meant that projects might look quite different to one another, tailored to shared needs, preferences, and local context.

Table 2. Examples of peer support dimensions impacting groups in Women-Side-by-Side.

The original Side-by-Side values were found to be both identifiable and applicable in different contexts. However, some adjustments were required to suit specific contexts and experiences. The following sections detail both the similarities and differences in the women’s and maternal context, as well as discussing our findings in relation to the implications of defining peer support and our experiences of using a peer research approach in doing so.

Exploring adaptions to the peer support values

The Women-Side-by-Side projects were provided with the Side-by-Side values toolkit by the funder (The Women-Side-by-Side evaluation team writing collaborative, Citation2020). The six original values were identifiable and applicable to the women-specific context. However, commonality of experience was more likely to be gendered, including domestic violence towards women and girls, than based on experiences limited to a mental health diagnosis.

It is a women-only space, and I think that's really important for women to have that space where they can share that commonality. (Women-Side-by-Side: Interview PI015, group member)

It’s all about trust really and if you trust them, they are going to trust you. (Women-Side-by-Side: Interview PI06, group member and facilitator)

It’s never just volunteers who are with the women alone. We always have a paid member of staff in the room as well, I suppose for safeguarding issues and things like that. (Women-Side-by-Side: Interview PI09, group member)

The Maternal Mental Health project also found that the Side-by-Side values were identifiable and applicable. This included the value of ‘Choice and Control’, which was similarly understood in all three projects as a core element of ‘good’ peer support.

Yeah. It’s okay not to say something. It’s okay to say, I’m not going to talk about this because I don’t feel comfortable talking about this. (Side-by-Side: Interview PV24, group)

So, what I struggled with was severe anxiety. They are quite good with making sure that they don’t force me to speak up or force me to participate. I have that option so that I am not anxious and am not having panic attacks. (Women-Side-by-Side: Interview PI016, group member)

There isn’t those timescales of you’ve got to come in for six sessions, or at this time or whatever, they can just come along … I know having anxiety and things, sometimes getting somewhere for a certain time can be quite difficult. (Maternal Mental Health: Interview FP02, peer lead)

So, like I said before, it’s for mums and dads and carers and people can come along with their family or with their friends. (Maternal Mental Health: Interview ST01, peer lead)

Peers should be involved at all levels, but there should be professional back up. (Maternal Mental Health: SWW, interview, peer lead)

[…] That was more to get the peer group to cohere again so they didn’t need us, so in the future the peer leaders would support each other so enable the group to continue. (Women-Side-by-Side: Interview PI020, staff)

Team reflections: are there unintended consequences in defining peer support values?

Although we saw merit in exploring values, there was a diversity of views amongst the three teams on how community-based peer support should be framed. We questioned: how formalised can peer support become before it loses its essence? The history of peer support as a social justice inspired counterweight to traditional, medicalised care was influential in how teams approached their evaluation work. However, this involved challenges, including the potential for professionalisation, as mentioned early in the Side-by-Side evaluation (Side-by-Side Early Findings Report, Citation2017): ‘The risk of professionalising peer support, losing core values in the process, in order to impress commissioners’ (p. 31).

Our team felt that as peer support is relational, personal, and highly varied, this must be captured and celebrated. Who a ‘peer’ is, and when, depends on context. We held pragmatic views on the professionalisation of peer support based on previous lived-experiences and immersion in projects themselves. Team members felt that any values created must apply to as wide a range of peer support types as possible and that community-based peer support was distinct from peer support worker roles. However, this was complicated by overlapping features in some forms of community-based peer support with formal peer support work. Overlap was identified in formalised processes including job descriptions, payment, supervision, safeguarding and record-keeping. Yet, there is room for a spectrum between structured forms of peer support and informal types.

A crucial, contested dimension, was the role of (peer) facilitation or leadership. In some contexts it is difficult to delineate between peer support and friendship. In others, this ‘line’ is critical in creating boundaries and ensuring safety. In some contexts, risk assessments and moderation guidelines were essential, e.g., in prison settings or online forums. In others, fluidity and shared ownership characterised the culture and distinctiveness of peer support. As peer researchers, we did not all agree on the role of facilitation. Nonetheless, we found that peer support facilitation and/or leadership decisions were central to how values were applied and experienced within projects. Who took on this role? Were they paid, trained and supported? If so, by whom? Despite differing views on the role of facilitation and leadership, we all agreed that lived-experience must be present in some leadership capacity in the development and delivery of peer support.

Values, toolkits and unintended consequences

We concluded that the values framework should be flexible. The pyramids were not designed to be a framework for defining peer support or to measure efficacy. A framework could be leveraged to increase funding opportunities, but we also felt there could be unintended consequences. We held concerns that describing values or creating a toolkit might contribute to commercialising peer support. Further, we felt that if the values were applied as a standardised model, it may foster something more akin to a professional worker-client structure with power imbalances, hindering the development of reciprocal peer relationships. It could also suggest to commissioners that there is one model with specific outcomes, when new peer support groups need adaptability and organic development. There were concerns that user-led community groups may be overlooked in commissioning decisions that favour larger providers with more formalised approaches to peer support. This trend could change the culture of provision to homogenic, outcome-driven approaches, marginalising the unique culture of peer support.

This tension arose in the Women-Side-by-Side evaluation where the team felt that, in some instances, values developed during Side-by-Side were applied as training or measurement tools. In contrast, in the Maternal Mental Health project, the team found there was appetite for a framework for peer supporters and organisations to use. This was seen to make peer support safer and more helpful for mothers whilst also demonstrating value to clinicians and attracting funding, and thus this tension did not resonate with their experience. The principles developed by this evaluation have been utilised and disseminated, suggesting support for their creation and use.

Power and peer research

Our teams were aware of their own peerness in evaluating peer support spaces where power hierarchies are traditionally flattened. We wanted to use methods consistent with the ethos of peer support. However, we were undertaking formalised funded evaluation, creating power differences between researcher and researched. Research and evaluation must also be robust and reliable. Across all evaluations, it was important to work reflexively and be aware of our own power as researchers. Peer researchers drew on lived-experiences in ways that felt appropriate and safe. The strongest sense of peerness came from our peer evaluation colleagues. However, despite many of the team being open about their experiences and this enriching relationships with projects and peers, in the Side-by-Side and Women-Side-by-Side projects we were not always viewed as peers. Identifying as a peer researcher sometimes unintentionally resulted in tensions for both the researchers and groups. There were instances where disclosure was both helpful and unhelpful. This contrasted with the Maternal Mental Health project team, where the term ‘peer facilitator’ was used. This may have allowed for a more equitable relationship with participants at consultation events – such as mothers with experience of mental ill-health – than if the title of peer researcher had been used. These experiences reflect our finding that how, and who, is seen as a peer depends on context, language and interactions. This is important for future work using peer research methods.

There were unintended consequences of being a peer in a research context. There was a sense that, as peer researchers, we were positioned as custodians of the concept of peer support. We felt a commitment to reciprocate to peers working with us, to inform outputs and dissemination. We wanted to ensure that any values we described were not seen to create artificial boundaries on peer support, or unintentionally severing it from its organic, civil rights roots. Creating values drawing on peerness involved a level of introspective reflection not often embedded into traditional evaluative research. As these tensions and conversations on values and peer support were intricately connected to peer researchers’ own identities and experiences, there was also an increased impact on emotional wellbeing. In all three teams, peer support of one another was crucial. This reflected the values we found within the projects with which we were working and strengthened our understanding of how peer support, in any context, shares a similar value base. Despite the emotional impact of undertaking peer research, this method is critical to ensuring any exploration of peer support aligns with its focus on mutuality.

Overall, we believe that describing peer support is useful to delineate and characterise the benefits of peer relationships. Generally, our teams were not averse to creating a toolkit of peer support values, but some were concerned about how these values could be applied. This raises another question: where do our responsibilities as evaluators end and the responsibilities of others begin? We believe that peer research methods reflect the values we saw within various types of peer support in different contexts and align with embedding lived experience. Nonetheless, we also feel the impacts of drawing on peerness are important considerations for peer research, especially in relation to peer support. Working in this way requires critical thinking around organisational support for peer researchers.

Discussion

Community-based peer support is described in different contexts. There are various ways in which it is organised, led and experienced. Delivery may be group-based or individual, in person or online, the latter becoming more present during the COVID-19 pandemic (Faulkner, Citation2020). Key values across different settings can be identified, and frameworks based on these can support people starting new projects as well as those reflecting on existing peer support. This was readily identified in the Maternal Mental Health project, where they developed their own framework based on new principles and an accompanying self-assessment tool (Mind & The McPin Foundation, Citation2019). However, categorising the heterogeneity of community-based peer support is challenging. Others have reported the risks of naming and describing characteristics of peer support (Mead & MacNeil, Citation2006). These include the potential loss of reciprocity in peer spaces if definitions are applied as a model, training tool or commissioning/evaluation framework rather than as a guide for peers to build on. Furthermore, where standardisation occurs, the development of authentic peer leadership could be lost in favour of roles designed to suit mainstream statutory systems. Smaller charities may lose out to larger providers that can meet high resource demands of outcome measurement. We propose that frameworks should be flexible to context and informed and led by peers.

Variability of peer support across context

We identified common underlying values across varied contexts, and the overlap between the values in the three datasets suggested similarities in experiences among peers. We also noted that values appeared and were prioritised differently in these contexts: for example, ‘Trust’ was identified as an additional foundational value in women-only peer support, and being ‘Family-Centred’ was foundational in the maternal mental health context. Further, ‘Experiences in Common’ were context-dependent and only definable by those within the peer relationship. These values will be experienced differently depending on practical decisions taken whilst setting up peer support in different contexts. The distinctions between formal peer support worker roles and community-based peer support facilitation were blurred, and ways in which people initiated groups to embed the value of safety differed. Although our work covered a significant breadth of diversity, including migrants and refugees, marginalised ethnic communities, and neurodiverse people, we could not explore all such contexts independently of one another. However, we anticipate that these common underlying values would apply in other peer support contexts, and further adaptions would also be required.

Peer research of peer support

Our peer researcher and peer facilitator team felt a responsibility to research peer support sensitively, carefully producing new knowledge. Researchers have a responsibility to ensure the roots of peer support are not erased by the popularity of peer support worker roles or groups facilitated by non-peers. As Gillard (Citation2019) suggests, studies of peer support should include peers as research leaders and resist the demands of ‘traditional health services’ evidence base, which is poorly aligned with grassroots peer support (Mead & MacNeil, Citation2006).

Limitations

The research was not designed as a comparative case study design; thus, methods varied between evaluations and projects differed in resource, structure, and staffing levels. A strength of this study is our reflective work. However, using this as data also necessitates a style of data reporting that may feel limiting; we have combined our voices on common ideas rather than directly quoting individuals so that no single voice was prioritised.

Conclusion

Peer support values must continue to remain flexible and peer-led, evolving in new contexts such as COVID-19. Our work did not seek to define community-based peer support, but to identify key values that can guide those involved in this vital mental health support. There are clear messages to mental health commissioners from our work, who should fund and develop peer support according to values-based frameworks rather than outcomes measures allowing for flexibility and context-specific evolution. We have a responsibility as peer researchers to consider any potentially negative unintended consequences of our work and to mitigate against them. In the peer support space, this means ensuring research outputs are useful, and that knowledge production is based upon methodologies that complement and are consistent with the values base of peer support itself.

Acknowledgements

We also wish to acknowledge everyone who has supported our work in the original three projects discussed in this paper including the researchers, peer researchers & peer facilitators as well as the teams at Mind, both the evaluation team and service development staff. We also wish to thank those that shared their experiences and knowledge of peer support.

Data availability statement

The anonymised data table used for this study is available on request from the McPin Foundation. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their original data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available

Disclosure statement

This work undertaken was in a charity that specialises in public and patient involvement in mental health research. Two authors work at a mental health charity that delivers peer support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adame, A., & Leitner, L. (2008). Breaking out of the mainstream: The evolution of peer support alternatives to the mental health system. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 10(3), 146–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1891/1559-4343.10.3.146

- Basset, T., Faulkner, A., Repper, J., & Stamou, E. (2010). Lived experience leading the way: Peer support in mental health. London: Together for Mental Wellbeing.

- Beresford, P., & Russo, J. (2016). Supporting the sustainability of Mad studies and preventing its co-option. Disability & Society, 31(2), 270–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1145380

- Billsborough, J., Currie, R., Gibson, S., Gillard, S., Golightley, S., Kotecha-Hazzard, R., … White, S. (2017). Evaluating the Side by Side peer support programme. London: St George’s, University of London and McPin Foundation.

- Dillon, J., & Hornstein, G. (2013). Hearing voices peer support groups: A powerful alternative for people in distress. Psychosis, 5(3), 286–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2013.843020

- Faulkner, A. (2020). The inconvenient complications of peer support: Part 1 & 2, National Survivor User Network. Available from: https://www.nsun.org.uk/Blog/the-inconvenient-complications-of-peer-support & https://www.nsun.org.uk/blog/the-inconvenient-complications-of-peer-support-part-2.

- Faulkner, A. (2020). Remote and Online peer support: A resource for peer support groups and organisations. https://www.nsun.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=cb18e4f8-a96c-46ab-9dbe-31112a0d7197.

- Faulkner, A., & Basset, T. (2012). A helping hand: Taking peer support into the 21st century. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 16(1), 41–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/20428301211205892

- Faulkner, A., & Basset, T. (2012). A long and honourable history. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 7(2), 53–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/17556221211236448

- Faulkner, A., & Kalathil, K. (2012). The freedom to be, the chance to dream: Preserving user-led peer support in mental health. London: Together for Mental Wellbeing.

- Gillard, S. (2019). Peer support in mental health services: Where is the research taking us, and do we want to go there? Journal of Mental Health, 28(4), 341–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1608935

- Gillard, S., Foster, R., Gibson, S., Goldsmith, L., Marks, J., & White, S. (2017). Describing a principles-based approach to developing and evaluating peer worker roles as peer support moves into mainstream mental health services. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(3), 133–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-03-2017-0016

- Ibrahim, N., Thompson, D., Nixdorf, R., Kalha, J., Mpango, R., Moran, G., … Puschner, B. (2020). A systematic review of influences on implementation of peer support work for adults with mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(3), 285–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01739-1

- Lloyd-Evans, B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Harrison, B., Istead, H., Brown, E., Pilling, S., … Kendall, T. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 14(39), 14–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-39

- Lushey, C. (2017). Peer research methodology: Challenges and solutions. SAGE Research Methods Cases. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473994614

- Mead, S., & MacNeil, C. (2006). Peer support: What makes it unique. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 10(2), 29–37. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228693717_Peer_Support_What_Makes_It_Unique.

- Mind & The McPin Foundation. (2019). Five Principles for Perinatal Peer Support, https://maternalmentalhealthalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/mind-mcpin-perinatal-peer-support-principles-full-mmha-WEB.pdf.

- Mind & The McPin Foundation. (2019). Peer Support Principles for Maternal Mental Health Project. https://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Peer-Support-Principles-for-perinatal-mental-Health-2019-FINAL.pdf.

- National Survivor User Network (NSUN). (2017). The peer support charter. https://www.nsun.org.uk/resource/peer-support-charter/. [Google Scholar].

- Noorani, T. (2013). Service user involvement, authority and the ‘expert-by-experience’ in mental health. Journal of Political Power, 6(1), 49–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2013.774979

- O’Hagan, M., Cyr, C., McKee, H., & Priest, R. (2010). Making the case for peer support. Calgary: Mental Health Commission of Canada, 1-92. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2016-07/MHCC_Making_the_Case_for_Peer_Support_2016_Eng.pdf.

- Rau, T. (2021). Consent decision making. Sociocracy for all. [online] Consent decision making | Sociocracy For All.

- Richmond, L. (2020). Peer Workers in Perinatal Mental Health Services: A Values-Based Approach. https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/6334/perinatal-mental-health-peer-support-thought-piece-final.pdf.

- Side-by-Side Early Findings Report. (2017). https://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/14814_Mind-Side-by-Side_Early-Research-findings_v9_Online.pdf.

- Silver, J., & Nemec, P. B. (2016). The role of the peer specialists: Unanswered questions. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(3), 289–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000216

- The Women-Side-by-Side evaluation team writing collaborative. (2020). Evaluation of the women Side by Side programme. https://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/WSBS-McPin-Report.pdf.

- Together for Mental Wellbeing. (2015). Peer support charter. https://www.together-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2016/03/Peer-Support-Charter-FINAL.pdf.

- Voronka, J. (2015). Troubling inclusion: The Politics of Peer Work and ‘people with lived experience’ in mental health interventions. PhD diss. University of Toronto.

- Watson, E., & Meddings, S. (Eds.) (2019). Peer support in mental health. Bloomsbury: Red Globe Press.

- Woods, A., Hart, A., & Spandler, H. (2019). The recovery narrative: Politics and possibilities of a genre. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-019-09623-y