ABSTRACT

Objective

Previous research has highlighted men and women from black ethnic groups are more likely to be diagnosed with poor mental health and may have difficulty recognising experiences as such, due to perceptions of stigma and culturally defined attributions of distress. The aim of this research was to explore how black ethnic groups experience mental distress and find meaning in their experiences according to cultural heritage.

Method

Semi-structured interviews with four participants and an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis were conducted.

Results

Findings describe an awareness of cultural stigma relating to mental health, emotional distance impacting disclosure within the family, mental health as a misunderstood concept and feelings of empowerment through acceptance and supported disclosure. Whilst cultural heritage was important for developing awareness and understanding of stigma, attributed meanings of mental distress were individualistic.

Discussion

Awareness of how stigmatic cultural conceptualisations are generationally represented and systemically maintained is vital to understanding how people from black ethnic groups experience mental distress. Clinical implications are discussed to explore how the socio-cultural and mental health needs of this population can be met.

Introduction

Mental health services offered in the UK as part of the National Health Service were previously considered among the best in Europe (World Health Organisation, Citation2008), to comprehensively support a range of psychological difficulties (Davidson, Citation2005). However, the impact of longstanding governmental budget cuts has made apparent the increased pressures on community and inpatient services to meet extraordinary demand, and highlighted inequalities for people experiencing complex mental health difficulties (Cummins, Citation2018). Findings from the Adult Psychiatric Comorbidity Survey 2014 report that one in four people in the UK will experience a mental health difficulty each year, however only 39% of this cohort will access professional support (McManus et al., Citation2016), and this figure falls to 7% for ethnic minority groups (Lubian et al., Citation2016). This highlights inequities in the accessibility of mental health care for ethnic minority communities as well as fundamental barriers to engaging with culturally appropriate services (Devonport et al., Citation2022). This finding is especially pertinent for black ethnic minority groups, and for the purpose of this research these groups will be defined as comprising individuals who identify as black British, black African and/or Caribbean.

Research has consistently shown that black people are significantly more likely than their non-UK counterparts and people from white ethnic groups to be diagnosed with a mental health condition, and likewise, second-generation African-Caribbean people born in the UK show a higher-than-average pre-disposition to experiencing severe psychological problems (Sharpley et al., Citation2001). An individual’s environment may have a more profound influence on psychological functioning than genetic factors due to available opportunities (Cantor-Graae & Selten, Citation2005); in context, black communities are more likely to be exposed to higher rates of discrimination (McLean et al., Citation2003), have significantly fewer social opportunities (Bhugra et al., Citation1997), and experience progressive social drift due to poor socio-environmental prospects (Murali & Oyebode, Citation2004).

Strikingly, only 6.2% of individuals from black communities actively seek mental health support from statutory services (Lubian et al., Citation2016), possibly due to perceptions and experiences of stigma associated with mental healthcare (Wood et al., Citation2022). Gender differences have also been found in perceptions of stigma, extent of disclosure and self-management techniques (Clement et al., Citation2015; Sisley et al., Citation2011). The gender differences in management of mental health among this cohort are considered to be due to services and interventions being perceived by men as ‘feminised’, (Morison et al., Citation2014), precipitating negative connotations of cultural misunderstanding and threatening dominant gender behaviour. Whilst there have been contradictions to these findings relating to help-seeking (Shim et al., Citation2009), people from black ethnic groups reported feeling uneasy with full disclosure of experiences to mental health workers due to perceived bias (Diala et al., Citation2001).

Research has shown disparity between the perceptions of service users, professionals, and the wider black community, maintaining that services facilitated by white ethnic providers consistently misinterpret expressions of cultural identity through gestures, colloquialisms, and behaviours (Memon et al., Citation2016). It has been argued that cultural mistrust of white mental health professionals is reflective of a wider, multidimensional, sociocultural experience between minority and majority ethnic groups; this argument provides insight into the psychosocial functioning of those who experience distress and makes it impossible to ignore the enduring impact of profound historical intergroup experiences (Whaley, Citation2001). For black communities there is a significant lack of opportunities within mental health service provision to engage with culturally sensitive professionals who are aware of the socio-economic challenges, inequality, and power imbalances they face, as well as the way in which mental health is culturally considered within these groups (McLean et al., Citation2003).

There is vast difference between cultural and ethnic identities within black ethnic groups, and the ways these are expressed and perceived within society must not be overlooked when considering experiences of mental distress (Lewis-Fernández & Kirmayer, Citation2019). Ethnicity and what it means to have an ethnic identity is fundamentally schematic; it determines behaviour and psychosocial functioning and is shaped by sociocultural and familial factors (Bhugra & Bahl, Citation1999). Whilst there is a wealth of research on non-Western cultural understandings of distress and help-seeking barriers in ethnic minority groups, there is limited literature concerned with experiential accounts of mental distress and subjective sense-making according to cultural background. This research aims to explore how individuals from black ethnic groups with lived experiences of poor mental health conceptualise and make sense of their experience, and how this is informed by cultural heritage. This will be achieved by asking ‘how do men and women from black ethnic groups experience mental distress and find meaning according to cultural heritage?’

Method

Participants and recruitment

Participants were required to be over 18 years of age, identify as black British, black African and/or black Caribbean and have experienced any type of mental health difficulty. Individuals who had a psychiatric admission in the two months prior to recruitment were not eligible to participate. Recruitment posters were distributed in the Psychology Department of London South Bank University’s campus, local mental health support groups and posted on social media. Four individuals – three self-identifying women and one man aged between 20 and 31 – expressed interest and were sent an information brief with full details of the research; no reimbursements were given. Three of the four participants were born in the UK, two reported experiencing difficulties with their mental health that were not formally diagnosed, and two participants had formal diagnoses of low mood and body dysmorphia, respectively. Names and identifiable places were changed to ensure anonymity ().

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Ethics

Ethical approval was gained by London South Bank University’s Department of Psychology. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to involvement and given the right to withdraw until the point of submission.

Data collection

Individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted with three participants in person and via Skype with one participant who was out of the UK at the time of the research. The mean interview length was 54 min, and explored cultural identity and understanding of mental health, lived experience of distress, help-seeking, disclosure, sense-making, and the attitudes of others. For example, ‘what does the culture you identify with believe about mental health?', ‘how did you make sense of the feelings or experiences you were having?', ‘can you tell me about a time you explained your experience to someone close to you? What was their response?'

Participants were provided with a hard copy of the research brief and a debrief statement upon completion of the interviews, which were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Individual transcripts were analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Smith, Citation1996), and examined alongside corresponding audio recording, with line-by-line margin notes of the descriptive characteristics of participants’ claims and acknowledgement of emotional responses. Notation was then repeated for linguistic nuances and conceptual annotations. These were used to focus on discrete chunks of the transcript to identify emergent themes and facilitate organisation. This process of clustering led to the development of superordinate themes, which were represented in a table with the corresponding page of the participant’s transcript and quote for reference.

This process was repeated for all four participants, and superordinate themes and quote data were repeatedly reviewed to identify thematic connections. This produced a hierarchical structure of superordinate themes prevalent within the entire data set with corresponding subordinate and emergent themes, which were represented in a master table with illustrative extracts.

Researcher – bracketing pre-conceptions

Residing in a culturally diverse area of London, I am aware of how disadvantage impacts wellbeing and standards of living within the black community. In my experience and coincidental interactions, having a strong ethnic identity, self-sufficiency, spiritual beliefs and a ‘just get on with it’ attitude is encouraged in black cultures. My pre-conception of managing mental distress focuses primarily on non-disclosure, self-management, and stigma with an intrinsic element of spirituality. I have consistently perceived a spectrum of juxtaposed humour toward mental health at one end and attributions of weakness, supernatural interference, and faith at the other, and I expect to find that much emphasis will be put on religion and self-management regarding sense-making and interventions. However, I appreciate this is simplistic as it assumes that culture is the only way by which meaning can be extracted from an experience, underemphasising social and gender roles, free will and the reach of media coverage and literature which exists about mental health.

I acknowledged preconceptions were likely to lead to confirmatory bias and impact the breadth of information I deemed beneficial from participants. Noting these views in a reflexive diary enabled me to compartmentalise them, take ownership of them and acknowledge them to be my interpretation of interactions, rather than absolute truths (Willig, Citation2008). By doing so, I am more able to explore the perspectives and perceptions of others, with acute awareness and flexibility to facilitate understanding through interpretation without the imposition of personal expectations.

Results

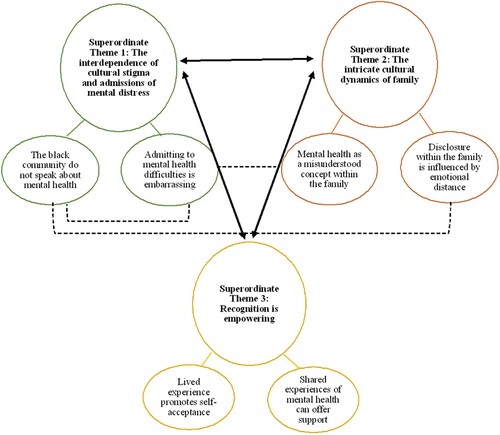

Analysis identified three superordinate themes with significant overlap and interaction: the interdependence of cultural stigma and admissions of mental distress, the intricate cultural dynamic of family, and the recognition is empowering. Each superordinate theme contained two subordinate themes.

The interdependence of cultural stigma and admission of mental distress

This theme represents awareness of stigma surrounding mental health and its impact on participants’ acceptance of their experience and disclosure outside of the family.

The black community do not speak about mental health

Erica made clear that the cultural stigma surrounding mental health in the black community is ‘very much a taboo topic […] the lack of awareness brings ignorance’ and it was suggested that it is perceived in older generations ‘as something probably quite bad erm demonic' as well as a culturally bound phenomenon rather than a universal experience.

[…] a white person’s disease (.) […] that’s something that white people have to deal with, that’s their experience it’s not ours. (Erica)

Interestingly, although Erica described an acute awareness of cultural stigma, disclosing her lived experience to a professional from the same ethnic background was important.

[…] a woman who is not of colour is not going to understand what I need […] I need to find somebody who will understand where I’m coming from. (Erica)

Erica acknowledges that the challenges of experiencing mental distress for someone from a black ethnic group are different to other ethnic groups in line with the cultural stigma she described. However, when help-seeking, ethnic matching and inherent understanding of these challenges was preferred, reflecting a desire for likeness in understanding psychological and sociocultural experiences takes priority over perceptions of cultural stigma, and therefore represents a protective factor facilitating disclosure and engendering trust.

Admitting to mental health difficulties is embarrassing

All participants referred to recognition of their experience as a process, a source of embarrassment and expressed concerns about being treated differently.

I was in denial, erm, (.) […] it’s one thing about looking at yourself and thinking, actually I need to seek help. (Erica)

Erica’s awareness of mental distress may have initially been outside her scope of lived experience, therefore resulting in denial reinforced by an awareness of it not being openly discussed. Maya’s feelings of embarrassment were influenced by her mother, saying, ‘my mum […] wouldn’t have told people […] because it’s embarrassing', which may reflect a generational conceptualisation of mental health according to accustomed cultural attitudes, and more significantly indicates how vicarious stigma may impact sense-making.

Similarly, Ana perceived she would be treated differently by others for disclosing her lived experience as a result of the negative stigma surrounding poor mental health.

If I’m having like a bad day […] they would see me as different. (Ana)

Ana’s concerns perhaps reflect self-perceptions of mental health which, in addition to awareness of stigma, may have reinforced feelings of being treated differently and inhibited disclosure of her experience. Daniel expressed similar challenges to disclosure, stating that it represented ‘an admission of, of something really dire', however, this is in the context of help-seeking rather than self-admission, which contrasts with the other accounts, reflecting that he has not been affected by cultural stigma in the same way.

Consistent references were made to expression of emotions being perceived as weakness which limited the extent of disclosure; as such, it is reasonable to question how suppression as a coping mechanism impacted recognition and acceptance of lived experiences. The perception of vulnerability as weakness suggests that resilience may be a culturally expected response to difficulty which highlights an awareness of the stigma surrounding exploration and displays of difficult emotions. In Maya’s case, her disclosure was circumscribed to those she could be emotionally open with as a form of self-protection and validation which may have facilitated deeper understanding.

I didn’t feel that my pain and my illness was valid […] they don’t see me as down, they don’t see me vulnerable. (Maya)

That said, an awareness of stigma in isolation may initially have impacted the sense she was able to make of her experience in the way she perceived validation, which corresponds to her embarrassment regarding disclosure.

The intricate cultural dynamic of family

This theme represents how participants’ lived experiences of mental distress were understood within their family.

Mental health as a misunderstood concept within the family

Two participants in particular felt that parental understanding of mental health was limited, and oversimplified beliefs were held about causes of mental distress.

Both Ana’s and Maya’s parents grew up in non-Western cultures and the obscure nature of mental distress, references to theology and generational differences in understanding of mental health was evident in both accounts. Maya reported ‘my mum never really understood why people get depressed', with Ana stating, ‘I don’t know if she even knows exactly what mental health is'. Ana also expressed that religious management suggested by her mother was insufficient in reducing her distress, reflecting an incongruence between understanding of Ana’s experience and influenced the extent of disclosure at home.

Disclosure within the family is impacted by emotional distance

Showing vulnerability through disclosure within the family was deemed as negative.

Ana stated, ‘I know that she does love me but the way she shows emotion, her love is different', and her mother’s response inhibited future disclosure of her distress within the family home, leading to a perception of emotional detachment and a reinforced need for resilience. Similarly, Erica explained that she did not feel comfortable showing vulnerability within her family.

I have to be very guarded and quite protective […] that’s a conversation I can’t have with my family.

Erica’s statement conveys threat and mistrust and her reference to a lack of emotional safety mirrors Ana’s extract. Erica also described how her need for self-protection was reinforced by her family’s reaction, which may have been informed by perceptions of criticism from others because of her acute awareness of stigma, as previously discussed, and inhibited further disclosure.

Daniel also reported that ‘it’s also really, really confronting thing to do as well as very uncomfortable place […] for me to be in, to have these kinds of talks with my parents', though it can be suggested that the context within which this discomfort is situated is different from the others’ experiences, as Daniel suggests that the disclosure is difficult for both parties rather than just himself. It is possible that a factor of Daniel’s discomfort with disclosure may be concerned with incongruence between a stereotypical gender role and showing vulnerability. A more significant consideration is that Daniel did not experience his mental health difficulties within the context of his Afro-Caribbean heritage and was therefore not exposed to the same cultural conceptualisations of mental distress or attitudes to disclosure.

Recognition is empowering

This theme encapsulates participants’ perceptions of their lived experience as being beneficial to their process of self-acceptance, building resilience and raising awareness of mental health.

Lived experience promotes self-acceptance

All participants unanimously perceived that their experience of poor mental health enabled them to accept it as one dimension of their life experience.

It doesn’t define me […] I’m still the same person that has many layers and sometimes you get the good part, sometimes you get the bad part. (Maya)

It’s not about […] bringing a defective self back up to sort of average working capacity, […] it’s sort of like an addition. (Daniel)

Whilst cultural background may have informed an awareness of stigma, the meaning participants attributed to their lived experience was self-generated and individualistic, lending itself to resilience, self-acceptance, and constructive self-reliance to overcome personal difficulty. However, there were some nuanced differences in the process of self-affirmation. Ana’s religious beliefs influenced management of her distress to an extent, signifying an external source of solace and a proxy by which she achieved self-affirmation. Similarly, Maya felt validated by her diagnosis to ‘protect the fact that I’m feeling this' and helped her to make sense of the emotions she was experiencing, though it is possible to question where Maya’s sense-making would be situated were it not for her diagnosis. However, the diagnostic label may represent comfort in much the same way as Ana’s religious beliefs and brings the two conflicting philosophies more into alignment.

Shared mental health experiences can offer support

Disclosure of lived experiences was described as beneficial if it facilitated relief and support, and participants were enthusiastic about normalising mental health.

If you sit down with someone who’s really done their work on themselves […] that someone who’s, you know, […] can really be valuable to you in, in that disclosure process. (Daniel)

Daniel’s description of the emotional support he deems valuable to his disclosure may reflect how it was facilitated within his family and wider social circle, particularly as he did not discuss cultural stigma in the same way as the other participants. Daniel also expressed that full disclosure could be a therapeutic process and may have been an opportunity for ownership of his experience and a route to establish meaning through vocalising his difficulties. Mental distress was also normalised by participants depicting that their experiences led to a heightened awareness of wellbeing extending beyond social exposure or cultural understanding.

All participants were motivated to share the challenges they faced in their own recognition, acceptance, and management of distress, and it is particularly telling that disclosure was considered valuable despite it not being facilitated within the family dynamic. This represents the duality of disclosure as empowering and inducing vulnerability, and it is also indicative that promotion of emotional safety and disclosure were not perceived in some family environments.

The superordinate themes and corresponding subordinate themes discussed are illustrated in . Although all data themes are meaningful individually, it is pertinent to address that the significance of overlap between them, as reflected in participants’ accounts, makes it is possible to draw connections to highlight how these factors interact and contribute to the participants’ understanding and sense-making of their lived experiences.

Discussion

The findings of this study resonate with previous research (Clement et al., Citation2015; Wood et al., Citation2022) highlighting that stigmatic attitudes present a barrier to distress recognition and disclosure. However, the current findings also indicate that cultural heritage in a familial context may contribute more significantly to these factors than has previously been accounted for.

Acute awareness of stigma was situated in participants’ cultural rather than societal context, suggesting that stigma and conceptualisations of mental distress are culturally transmitted through families (Office of the Surgeon General U.S, Citation2001) and integrated with aspects of cultural identity (Kleinman & Hall-Clifford, Citation2009). Therefore, this impact within a cultural family environment is more pronounced due to a concentration of beliefs, values, and identities, suggesting that cultural attitudes structure the family environment to create a psychosocial contribution to stigma (Rutter, Citation2005). Whilst this research showed that disclosure inhibition and perceptions of emotional distance were concentrated within the family system, it can be argued that the immediate family environment can be also be a protective factor from cultural stigma for people from ethnic minority backgrounds (Wood et al., Citation2022), which was reflected in Daniel’s account. Furthermore, conceptualisations of mental distress relating to spirituality and morality in the present study was discussed only in the context of older generations, perhaps reflecting an attitudinal shift across generations. It is also plausible that additional factors within the household, such as the degree of culturally informed beliefs, age variance and nature of relationships may account for the impact of these differences. Nevertheless, these variables indicate that cultural family dynamics have not been sufficiently studied in relation to experiences of mental distress in ethnic minority groups.

Even though previous research has found gender differences in stigma experiences (Sisley et al., Citation2011), in this study all participants felt vulnerable disclosing their lived experience and stigma was only perceived to be pervasive if participants were exposed to their cultural heritage. This may be due to concerns of there being a lack of understanding and risk of being ostracised from their cultural community due to experiencing poor mental health (Wood et al., Citation2022). Only one participant did not demonstrate an awareness of cultural stigma, leading to the assumption that the non-black culture within which they were raised offered psychological security during experiences of distress (Mossakowski, Citation2003) in much the same way as ethnic matching in help-seeking interactions (Cabral & Smith, Citation2011).

Although it has been argued that perceptions of stigma and insight into mental health difficulties negatively impacts self-efficacy (Lysaker et al., Citation2008), the opposite was found in this research. All meanings participants attributed to their distress were individualistic, and although participants’ cultural identities were stable, it was not a component which facilitated meaning. Therefore, their sense of self identity was more pronounced and promoted self-efficacy and empowerment of the self and others (Hemenover, Citation2003). This further contributed to resilience and ameliorated the impact of cultural stigma (Schwarzer & Warner, Citation2013).

Regarding the limitations of the study, it is acknowledged that within the small sample, single interviews per participant were conducted without follow-up. Due to the quality of data elicited from initial interviews within the limited scope of this research, secondary interviews were not considered necessary given the useability of the existing data and best practice guidelines (Smith et al., Citation2009; Vasileiou et al., Citation2018). That said it is necessary to consider whether breadth of responses may have been restricted if respective difficulties were still being actively experienced, as participants’ perceptions and sense of self-growth may not have been as developed or expressed as being meaningful. Although findings cannot be generalised, it is prudent to highlight that the gender sample was unbalanced, potentially limiting reliability of the representation and reflecting volunteer bias (Edlund et al., Citation1985). Whilst participants demonstrated an awareness of generational differences in cultural stigma, it was not possible to explore this further alongside any distinctions between culture-specific conceptualisations of mental distress due to the narrow age range and limited cultural breadth of the sample. Furthermore, although a negative correlation between social disadvantage and mental wellbeing for people from ethnic minority groups was acknowledged (Murali & Oyebode, Citation2004), participants’ socio-demographics were not discussed in relation to the current findings, given the limited scope of the research. As such, the process of interpretation may not have encapsulated the nuances of participants’ experiences.

It was recognised following analysis that previous emphasis on spirituality as a means of sense-making was misplaced, and the role of a self-identity was overlooked. It is also possible that pre-conceptions may have been discernible due to minor lapses in critical language awareness (Willig, Citation2008) in less structured moments of the interviews. This could have highlighted expectations and led participants to respond in ways they perceived would be desirable to the researcher, therefore, demonstrating demand characteristics Researcher pre-conceptions may have also led to sections of data being discriminately afforded more focus during the analytic process; therefore, the original transcripts were systematically reviewed to preserve a close tie with the data whilst maintaining a distinction between researcher interpretation and experiential accounts (Smith & Osborn, Citation2004).

Future research

Given the vast difference between cultural and ethnic identities within black communities, future research could explore convergences and differences in inter-generational attitudes of mental distress between black ethnic groups. Further research is also required to identify whether culturally informed conceptualisations of mental health may be subject to change at different stages of experiencing a mental health difficulty. Thus, providing a rationale to not only to focus on outcomes, perceptions, and recognition, but also to explore challenges attached to these lived experiences which diversify attributions of meaning.

Clinical implications

There must be an awareness of the impact of cultural stigma in an intimate family environment as well as a barrier to socio-cultural understanding and management of mental distress. Understanding the evolution of cultural attitudes will ensure that consistent cultural sensitivity is demonstrated at initial triage to identify potential systemic difficulties which may further impact mental distress, and to support emotional disclosure and processes of sense-making through desired frames of reference. In turn, this will encourage more positive pathways to accessing support, reduce cultural stigma and avoid marginalising the needs, cultural beliefs and lived experiences of the black community (Bhugra & Bahl, Citation1999).

Conclusion

Cultural heritage may impart an acute awareness of stigma regarding mental distress in the black community, particularly in older generations, and negative attitudes and misunderstandings of distress may be filtered down through generations through cultural transmission. Whilst cultural stigma impacts disclosure, it does not wholly inform attributional meanings for lived experiences, which were observed to be situated within individual self-concepts. This process of sense-making was discussed in relation to differentiation between cultural and self-identity, and the protective role ethnic identity may play in offering psychological security was acknowledged. It is necessary to create receptive, culturally appropriate services which offer sensitive facilitation of the subjective process by which experiences may be recognised, and to reflect an understanding of a possible protective need for ethnic matching to engender trust, and the prevalent socio-cultural challenges within and away from the family environment. It is this process which, if sufficiently supported, can replace cultural and social conceptualisations of mental health as weakness and instead serve to promote it as an aspect of lived experience which offers an additional dimension of self to embody empowerment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bhugra, D., & Bahl, V. (1999). Ethnicity – Issues of definition. In D. Bhugra, & V. Bahl (Eds.), Ethnicity: An agenda for mental health¸ (pp. 1–6). Gaskell.

- Bhugra, D., Leff, J., Mallett, R., Der, G., Corridan, B., & Rudge, S. (1997). Incidence and outcome of schizophrenia in whites, African-Caribbeans and Asians in London. Psychological Medicine, 27(4), 791–798. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291797005369

- Cabral, R. R., & Smith, T. B. (2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025266

- Cantor-Graae, E., & Selten, J. (2005). Schizophrenia and migration: A meta-analysis and review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.12

- Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., Morgan, C., Rüsch, N., Brown, J. S., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129

- Cummins, I. (2018). The impact of austerity on mental health service provision: A UK perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061145

- Davidson, L. (2005). Recovery, self-management and the expert patient – Changing the culture of mental health from a UK perspective. Journal of Mental Health, 14(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230500047968

- Devonport, T. J., Ward, G., Morrissey, H., Burt, C., Harris, J., Burt, S., Patel, R., Manning, R., Paredes, R., & Nicholls, W. (2022). A systematic review of inequalities in the mental health experiences of Black African, Black Caribbean and black-mixed UK populations: Implications for action. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 10(4), 1669–1681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01352-0

- Diala, C. C., Muntaner, C., Walrath, C., Nickerson, K., LaVeist, T., & Leaf, P. (2001). Racial/ethnic differences in attitudes toward seeking professional mental health services. American Journal of Public Health, 91(5), 805. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.5.805

- Edlund, M. J., Craig, T. J., & Richardson, M. A. (1985). Informed consent as a form of volunteer bias. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142(5), 624–627. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.142.5.624

- Hemenover, S. H. (2003). The good, the bad, and the healthy: Impacts of emotional disclosure of trauma on resilient self-concept and psychological distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(10), 1236–1244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203255228

- Kleinman, A., & Hall-Clifford, R. (2009). Stigma: A social, cultural and moral process. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(6), 418–419. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.084277

- Lewis-Fernández, R., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2019). Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: Understanding symptom experience and expression in context. Transcultural Psychiatry, 56(4), 786–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519861795

- Lubian, K., Weich, S., Stansfeld, S., Bebbington, P., Brugha, T., Spiers, N., McManus, S., & Cooper, C. (2016). Mental health treatment and service use. In S. McManus, P. Beddington, R. Jenkins, & T. Bhugra (Eds.), Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014: A survey carried Out for NHS digital by NatCen social research and the department of health sciences (pp. 69–105). University of Leicester, NHS Digital.

- Lysaker, P. H., Tsai, J., Yanos, P., & Roe, D. (2008). Associations of multiple domains of self-esteem with four dimensions of stigma in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 98(1–3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.035

- McLean, C., Campbell, C., & Cornish, F. (2003). African-Caribbean interactions with mental health services in the UK: Experiences and expectations of exclusion as (re)productive of health inequalities. Social Science & Medicine, 56(3), 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00063-1

- McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., & Brugha, T. (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014: A survey carried Out for NHS digital by NatCen social research and the department of health sciences. University of Leicester, NHS Digital.

- Memon, A., Taylor, K., Mohebati, L. M., Sundin, J., Cooper, M., Scanlon, T., & De Visser, R. (2016). Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open, 6(11). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337

- Morison, L., Trigeorgis, C., & John, M. (2014). Are mental health services inherently feminised? The Psychologist.

- Mossakowski, K. N. (2003). Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519782

- Murali, V., & Oyebode, F. (2004). Poverty, social inequality and mental health. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 10(3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.10.3.216

- Office of the Surgeon General. (2001). Culture counts: The influence of culture and society on mental health. In Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity: A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

- Rutter, M. (2005). How the environment affects mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(1), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.1.4

- Schwarzer, R., & Warner, L. M. (2013). Perceived self-efficacy and its relationship to resilience. In S. Prince-Embury, & D. Saklofske (Eds.), Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults (pp. 139–150). Springer.

- Sharpley, M., Hutchinson, G., Murray, R. M., & McKenzie, K. (2001). Understanding the excess of psychosis among the African-Caribbean population in England: review of current hypotheses. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(S40), s60–s68. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.40.s60

- Shim, R. S., Compton, M. T., Rust, G., Druss, B. G., & Kaslow, N. J. (2009). Race-ethnicity as a predictor of attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking. Psychiatric Services, 60(10), 1336–1341. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1336

- Sisley, E. J., Hutton, J. M., Goodbody, C. L., & Brown, J. S. (2011). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of African Caribbean women’s experiences and management of emotional distress. Health & Social Care in the Community, 19(4), 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00986.x

- Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology & Health, 11(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400256

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage.

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2004). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 53–80). Sage.

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Whaley, A. L. (2001). Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. The Counselling Psychologist, 29(4), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000001294003

- Willig, C. (2008). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Open University Press.

- Wood, L., Byrne, R., Enache, G., Lewis, S., Fernandez Diaz, M., & Morrison, A. P. (2022). Understanding the stigma of psychosis in ethnic minority groups: A qualitative exploration. Stigma and Health, 7(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000353

- World Health Organisation. (2008). Policies and practices for mental health in Europe: Meeting the challenges.