ABSTRACT

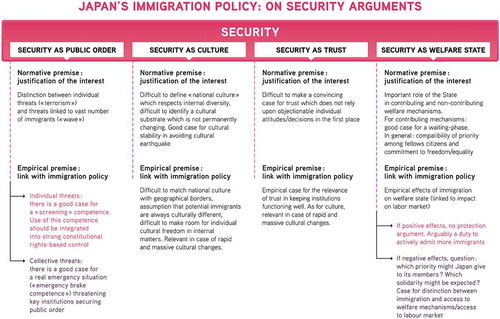

This article contributes to the growing interest in both the ethics of immigration and Japanese immigration studies by analysing the ethical justification of Japan’s immigration policy. The main objective of this article is to specify and address security-based justifications as part of an investigation into the ethical dimension of Japan’s immigration policy. Security is systematically drawn upon as one of the most powerful rationales to justify the competence claimed by Japan to control immigration as it deems adequate. The article will first specify the types of justification at stake. Second, it unpacks four understandings of security in immigration matters: as public order, as protection of welfare mechanisms, as cultural stability and as protection of social trust. Each of these justifications is bound with specific ethical challenges. Overall, the article maps the different justification strategies, their shortcomings and their advantages. The article intends to launch a proper ethical debate on Japan’s immigration policy.

The ethics of Japanese immigration policy

The challenges of immigration have long reached the shores of Japan. Although the government is reluctant to publicly address labour immigration, immigration has found a place within political debates. After his re-election, Prime Minister Abe made clear that Japan would keep its (officially) highly selective labour immigration policy. This position has faced a number of criticisms, ranging from economic concerns about an ageing population to humanitarian calls to relax the asylum policy.Footnote1

This article focuses on a specific type of challenge linked to immigration policy: its ethical dimension. It moves beyond current political and legal debates to dig into the issue of the justification of Japan’s immigration policy. As explained in detail in the methodological section, the task of providing justification is understood as a specific ethical challenge. This article is not an investigation about the legality of immigration laws or an investigation into the socio-political explanations of a specific policy output (Chiavacci, Citation2011; Chung, Citation2014; Roberts, Citation2012; Vogt, Citation2017a). On the contrary, the question focuses on the consistency of ethical arguments based on specific values and principles to which Japan has committed itself.

Within this context of the search for ethical justification, this article focuses on the key argument used for a restrictive immigration policy: security. This argument is well known from public debates on immigration, and has been extensively documented in the literature (Chiavacci, Citation2014, p. 133 ff). Like other industrialized states, Japan has noticed a securitization of its immigration discourse. As put by Chiavacci, the ambition to guarantee security is one of the key rationales in the current immigration debate in Japan: ‘according to this discourse, foreign nationals and increasing immigration are an internal security threat undermining social harmony and public peace’ (Chiavacci, Citation2014, p. 115).Footnote2 This article will unpack this standard argument and map the different understandings of security and their function in the ethics of Japan’s immigration policy. This shall allow us to disentangle normative and empirical claims linked to security.

This article’s contribution is situated at the junction of a growing interest in both ethics of immigration and Japanese immigration study. Although Japanese immigration policy is an important field of interest, its ethical dimensions have remained, at best, dealt with in the margin. In the meantime, the general literature on immigration ethics has not been very interested in applying ethical frameworks on national or regional case studies, let alone on Japan.Footnote3 This article fills this double gap by focusing on one ethical challenge faced by Japan’s immigration policy. Additionally, it provides the broader community of scholars working on the ethics of immigration with a new case study for comparative analysis.

This article is divided into two sections. First, it specifies the scope and the methodology of the investigation with an emphasis on the importance of ethics claims in addition to legal and socio-political investigations of immigration policy. Second, it addresses the structure of security-based arguments used to justify Japan’s immigration regime. Third, it distinguishes and investigates four distinct understandings of security (as public order, as protection of welfare mechanisms, as cultural stability and as protection of social trust).

Scope and methodology

Scope

This article raises the question of the ethical justification used in the context of regular admission into Japan for the purposes of work. To this end, it will not deal with questions of how cohabitation and cooperation within the political community after admission ought to be organizedFootnote4 which is related to the key issue of integration (Komine, Citation2014; Nagy, Citation2012).Footnote5 The main reason to exclude integration from the scope of this article is the ambition to focus on the specific challenges linked to admission, which are arguably distinct from those arising once the immigrant has been accepted into the political community.Footnote6

On the other hand, the article focuses on immigration that occurs within the legal and administrative rules foreseen by the country of destination (‘regular immigration’).Footnote7 The focus on regular immigration, defined as immigration occurring with the consent of the country of destination and with respect for the necessary legal and administrative steps, could be criticized as too enthusiastic regarding the sheer capacity of a political community to control immigration in a meaningful way (Bast, Citation2011, pp. 12–20). This criticism can take the form of the ‘primacy of economic factors’ (by arguing that political and legal decisions are irrelevant in comparison to economic factorsFootnote8 ) or the form of scepticism towards any attempts to control, at a national or regional level (by arguing that only a truly global immigration regime would be efficient) (Castles, Citation2004, p. 210 ff; Dauvergne, Citation2008, p. 29 ff). For the sake of our investigation, this line of criticism should be taken as a warning against the over-interpretation of the capacity of a community to control immigration (Bast, Citation2011, p. 16).Footnote9 In this regards, Japan takes advantages of natural barriers against mobility to ensure efficient control upon entry (Vogt & Achenbach, Citation2012, p. 14).

Methodology

By raising the question of the ethical justification of Japan’s labour immigration policy, this article aims at combining insights by political philosophers with legal scholars and political scientists.Footnote10 We shall first get a better sense of what an ethical justification amounts to and second, specify which normative resources are needed for this exercise.

In general, an ethical justification relates to the normative quality of being able to be recognized as a valid and consistent proposal by the relevant individuals .Footnote11 It pertains to an exercise of comparative and critical judgment since it puts a specific argument ‘against a background presumption of possible objection’ (Simmons, Citation2001, p. 124).Footnote12 The capacity of a specific argument to survive (even hypothetical) objections is here at stake. Understood in this way, ‘justified’ might be used almost interchangeably with ‘legitimate’. In both cases, the key insight for our investigation is to question the way policies, norms or practices are justified in light of Japan’s values and principles.

A policy or a law is not ‘ethical’ per se, it can only be described as ethically plausible or consistent because it convincingly relates to the relevant frame of references. The arguments used in this exercise of ethical justification are based upon a set of values and principles. The search for an ethical justification hence relies on making explicit which underlying values and principles we assume and upon which we elaborate further arguments. The key concept here is ‘consistency’ between specific policy choices enacted in immigration matters and fundamental values and principles proclaimed as normative foundations of the community. As a consequence, the task is not to declare specific norms ‘ethical’ or not in general, but rather to highlight the ethical challenges faced by Japan’s immigration policy in light of the values and principles chosen by Japan itself.

The challenge is of course to make explicit this frame of references (the values and principles ‘endorsed’ by Japan). First of all, let us make clear that to speak of ‘Japan’ is a linguistic shortcut to mean the politically constituted community of Japan (and, as a democracy, the voices of its citizens). Second, we assume that the frame of references endorsed by Japanese citizens in terms of values and principles can be found in key legal commitments accepted by these citizens: the Constitution, but also international agreements accepted by Japan, such as the two UN Covenants on Human Rights (Hasebe, Citation2015). These institutionalized commitments are important features of the state of Japan. They represent the general framework within which Japanese citizens (or their chosen representatives) organize life in society and choose how Japan should act beyond its national borders.

Even if it takes them as a broad frame of reference, the present article is not the place to provide a detailed qualification of Japan’s values and principles (as a matter of constitutional interpretation, for instance).Footnote13 For the sake of the argument, we shall often come back to the essential values of individual freedom and moral equality. It seems plausible to interpret Japan’s commitments (such as the ratification of the two UN Covenants on the protection of human rights, but also the commitment to justice and peace as entailed by the Constitution) as an expression of these two values (notwithstanding important and persistent disagreements about what these values exactly represent and amount to). These values shall represent the provisionally given frame of reference of our argument.

Overall, this search for a consistent justification clearly pertains to a normative category and shall not be conflated with a sociological or legal category. The issue is not whether a specific legal norm is regarded as legitimate as a matter of psychological or sociological fact, but whether it proves consistent with certain values and principles. Nevertheless, this contribution works in tandem with empirical investigations conducted by political scientists. Applied ethics is deeply in need of solid empirical data to be able to provide guidance for action. If it wants to formulate practical recommendations, there is a requirement for ethics to engage with empirical scientists. However, for the present article, my claim is more modest. I aim to unpack and map the different understandings which the call to ‘security’ can have in the context of an ethical justification. The argument proceeds in the form of distinct scenarios which are able to integrate empirical research. It typically takes the following form: if it could be shown that X is empirically true, it then follows that X might be used as ethical argument in the following way Y.

On security: justifying Japan’s immigration regime

The preservation of security is one of the most powerful rationales in the context of the Japanese immigration regime (as in other industrialized states) (Akashi, Citation2014, p. 189; Chiavacci, Citation2014, p. 130; Vogt & Behaghel, Citation2006, p. 138 ff). According to Chiavacci, reference to security is by far the most influential discourse in favour of a very restrictive immigration policy (being often opposed to demography-based discourse for open immigration policy). More immigration is seen ‘as a serious peril that will lead to higher criminality, social and ethnic conflicts and will destroy Japan’s social order’ (Chiavacci, Citation2014, p. 115).

Expressed as part of an attempt to justify the competence of Japan to control immigration, the standard argument can be reconstructed in the following way: the competence to choose a very restrictive immigration policy is seen as a required means to guarantee security. This standard argument is the focus of the present chapter. Two main questions are at the forefront: (a) in the context of the search for an ethical justification, where should we locate this security-based argument? (b) How should we understand ‘security’ and which normative implications have distinct definitions?

Locating security in the ethics of immigration

The first task is to locate the security-based argument in the fields of the ethics of immigration. The first dimension is about the level of relevance of the argument. We need to distinguish between the fundamental competence of Japan to regulate immigration and the use of this competence made by Japan (choosing an immigration policy X). The competence is about the claim made by Japan to have the right to choose, frame and implement an immigration policy, as it deems adequate. It underlies every concrete decision made as part of the determination of an immigration policy. This fundamental competence has been the key issue of immigration ethics for almost 30 years (Bader, Citation2005; Carens, Citation2013; Seglow, Citation2013). As it appears, the stakes are high. To find a satisfactory answer to this question is a precondition for Japan to legitimately choose any immigration policy. If it cannot justify its general competence to do so, it has no good ethical case to choose any immigration policy, let alone a restrictive policy that is constructed around the exclusive promotion of its own economic interests. If the fundamental competence is found to be justifiable, the ethical question can be shifted towards the use by Japan of its competence. The criticisms then bear upon features of a specific immigration policy (such as, for instance, the effects of the ‘technical trainees’ programmes upon neighbour states). This issue is independent from the justification given to the fundamental competence to regulate immigration.

In light of this first distinction, the claim to security might be used at two different levels. It can first be used as an argument for the fundamental competence to regulate immigration, and second, to justify a specific immigration policy. We shall above all focus on its use as an argument for the fundamental competence.

The second distinction required to precisely locate the security argument is between two types of arguments: protection arguments and control arguments (Cassee, Citation2016, p. 31 ff; Oberman, Citation2016). This distinction serves as a heuristic device to grasp the structural forces and weaknesses of the different arguments used. Both control and protection arguments can be used simultaneously. They are not exclusive and can be combined.

The structures of the arguments are different. The protection arguments have an instrumental structure: a competence to regulate immigration is needed as a means to protect a valuable good/interest. The logical structure of the arguments can be reconstructed in the following way: (1) a normative premise related to the valuable good/interest (which good? why is it valuable?) and (2) an empirical premise related to the link between the protection of this good/interest and the competence to regulate immigration (how do the two relate to each other?) (Abizadeh, Citation2006). To take an example which we will address at length below: culture is a valuable good for Japan (normative premise) and it might be the case that to safeguard culture, Japan needs the competence to regulate who resides on the territory for which purposes (empirical premise).

By contrast, the control arguments have a different structure. They start from a normative premise on the general right of a political community to be self-determined. The competence to regulate immigration is a component of this general political self-determination. Control arguments also include arguments in which the state is called to maximize economic prosperity and, for that sake, use immigration policy in a specific way.Footnote14 This type of argument relies upon the state determining the objectives it wants to pursue and using immigration policy as a tool. The same way citizens might decide upon the objectives of energy policy, redistribution policy or economic policy, they might decide upon immigration as part of their broader prerogative to organize the life of their society as they deem appropriate. Several variations of the control argument have been addressed in the literature (Pevnick, Citation2011; Wellman, Citation2008; Wellman & Cole, Citation2011).

It is important to see that the two types of arguments contribute to a justification, but not the same type of justification. The protection arguments might arguably provide a good justification for a competence, which takes the form of an emergency brake. In order to protect a specific good/interest, the community has a strong justification to control immigration up to a certain threshold. The justification is broadly negative: the state should have the competence to prevent individuals from entering the territory as soon as the good/interest is put at risk. But this justification is limited to the extent that the measure taken contributes to the required protection of the good/interest. In the contrary case, control arguments provide a far broader justification, which encompasses all dimensions of the immigration policy. The strong link with the claim of the state to choose its policy objectives (as part of its right to self-determination) explains the different scope of the justification.

In light of this distinction, the argument on security clearly appears as a protection argument. In the context of immigration, security is seen as a valuable interest, which Japan has a right to claim and protect (normative premise). If it can be shown that the regulation of immigration has repercussions on this interest (empirical premise), Japan might have a solid argument to justify its competence. However, even if the argument succeeds, it succeeds only in justifying what we have called an emergency brake. The argument has a threshold structure. It is only to the extent that immigration is threatening the specific interest that the state has the justified competence to control immigration. And in that context, control means to prevent people from entering. A protection argument focused on security could hardly justify the claim raised by Japan to favour highly skilled immigration. It must be shown that Japan has no choice but to favour this type of immigration in order to guarantee security.

This short reflection has laid down the structural features of the security argument. This argument should be apprehended as a protection argument. Our next task is to unpack what security could mean in the context of immigration policy and to investigate the normative premise upon which the distinct understandings are based.

Security and its distinct understandings

In a broad sense, security refers to all institutions and practices that, more or less directly, bear upon the fundamental features of a pacified coexistence in a society.Footnote15 In the following, I shall distinguish between four main understandings of security: as protection from criminal threats/public order, as protection of welfare mechanisms, as protection of the Japanese society specifically and as protection of social trust.

Security as public order

The interest in safeguarding security as public order directly concerns the fundamental mission of a political community. In the immigration debate, even promoters of a clear position towards open borders recognize the force of the security argument (Carens, Citation1992, p. 28 ff., Citation2010, p. 14 ff.; Kostakopoulou, Citation1998, p. 899; Märker, Citation2005, p. 122; Mona, Citation2007, pp. 379–405).

The focus on security narrowly defined has implications on the types of dangers which might threaten it. Two broad categories can be distinguished (Cole, Citation2000, p. 142; Mona, Citation2007, pp. 383–384). The first pertains to individual dangers in the form of persons or groups of persons whose objective is to harm central institutions of the community. This is the figure of the ‘terrorist’: a person with destructive intentions. The second pertains to the cumulative effects of a large number of immigrants. Taken individually, these persons do not have negative intentions vis-à-vis the community and do not pose any threat. Their sheer number, however, does threaten the community. In public discourse, this is the figure of the immigrant ‘wave’ that destroys the ‘dam’ of society.

The first context pertains to the interest of the community to forbid entrance to individuals with dangerous intentions (Kukathas, Citation2005). In the Japanese context, this link is especially strong when it comes to ‘explain’ criminality in light of immigration (or the presence of foreigners) (Shipper, Citation2005, p. 303 ff). For our focus on admission, the question at stake pertains to the conditions of assessment of someone’s dangerousness. In light of Japan’s commitment to protect fundamental rights (as expressed in Art. 11–13 of its Constitution, but also through its ratification of the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights), one of the most important of these principles is the presumption that community members and potential members alike behave or will behave in accordance with the legal rules in force. This basic presumption of rules compliance does not only frame most of the penal system (presumption of innocence) (Hasebe, Citation2015, pp. 303–304), but also shapes the different national constitutional orders. This presumption might, however, be rebutted on an individual basis if there were sufficiently solid grounds to judge a potentially dangerous individual to the community. But this individual assessment shall respect certain principles. The danger for public policy and security shall be exclusively based upon the conduct of the individual concerned. This individual shall represent a genuine, present and sufficiently serious threat to one of the fundamental interests of society.Footnote16 In that case, this assessment might consistently be used in the context of admission decisions.

However sound, this formulation already reveals all of the difficulties. As a normative challenge, the definition of a satisfactory threshold is a key question. The formulation makes clear that the danger threshold should not be equated with reference to some kind of ‘Otherness’. The decision by the Trump administration to equate the origin of people (being a citizen of a country with a majority of Muslim citizens) with risks of terrorism (which lead to a ban on entry) is a very striking example of a logic that goes against the key principles of a rights-based constitutional order. The fact that an individual comes from a culturally, religiously or politically different society does not constitute sufficient ground to presume that he has dangerous intentions (Cole, Citation2000, p. 143). To argue the contrary would be to reverse the presumption of innocence. In addition to this difficult normative task of defining this individual’s threshold of danger, there are also plenty of practical difficulties. These pertain to the assessment of the individuals at the borders, the kind of procedures foreseen for this task and their procedural guarantees.

In brief, Japan has a strong argument for its competence to regulate immigration if used to forbid entry to individuals with sufficiently well-substantiated dangerous intentions against law and order. Despite its strength, the argument can only be used to justify specific types of measures directly linked to the guarantee of law and order within Japan. Most importantly, it justifies specific preventive measures taken by the authority to assess potential immigrants.Footnote17 This ‘screening’ competence focuses on the prerogative to screen out potential immigrants and take, under strict conditions, appropriate measures against individuals found dangerous (Cholewinski, Citation2005, p. 250). To use an illustration, the immigration officer at Narita Airport has a good justification for screening entry applications and asking questions about suspect cases; but the argument does not justify his competence to choose the substantial part of the immigration policy. For instance, the focus on highly qualified immigrants chosen by Japan cannot be justified with this strict focus on security.

The second dimension of security understood as public order pertains to the community’s interest to prevent a massive arrival of potential immigrants (‘wave’). The focus here lies on the cumulative effects of numerous individuals wanting to enter Japan. This second context raises specific difficulties, which are mainly linked to the definition of an acceptable quantitative threshold.

From the point of view of members of the community and potential migrants alike, it is clearly desirable to prevent the collapse of the fundamental institutions of a pacified political community (Mona, Citation2007, pp. 386–387). The main difficulty would be to distinguish between a legitimate prevention of this collapse and the mere rhetorical utilization of this argument for the sake of a restrictive Japanese immigration policy.Footnote18 This immediately makes the main difficulty with this ‘wave’ variation apparent: the empirical premise is very difficult to fulfil and will only be actionable in emergency situations. It should namely be shown that a massive movement of people arriving to Japan is a plausible scenario and that its credibility justifies taking measures immediately. The current crisis between the two Koreas might represent such a situation, which might lead to important movements of people.Footnote19

Indeed, if this case is made empirically plausible, there is a strong justification for the competence to protect public order against rapid and massive movements of immigration by using specific immigration-related mechanisms. On the one side, it could mean mechanisms meant to deal with the worst-case scenario and the need to outline what a proportional and coordinated institutional response could look like. On this point, we could compare this task with the emergency clause entailed by the Schengen Borders Code, which allows Member States to reintroduce checks at internal borders in the event of a serious threat to internal security.Footnote20 On the other side, it could mean institutional mechanisms meant to ensure the ongoing monitoring of international developments that could lead to such massive movements. Overall, as for the first understanding of preserving security from terrorist threat, this second understanding does not justify any substantial immigration policy. It only justifies a quantitative threshold where emergency mechanisms might be put into place.

Summarising our reflections on the two dimensions related to security narrowly defined as defence of public order, there appears to be a strong argument for the competence to enact specific control measures. As explained when dealing with the structure of the protection argument, our reflections have highlighted that the majority of justifiable measures take the form of an ‘emergency-brake’. If a certain threshold is trespassed, closing mechanisms can be used. With respect to the figure of the ‘terrorist’, another type of mechanism was shown as justifiable: a ‘screening’ competence. But here also, the screening may only lead to concrete action if a specific threshold of danger is trespassed.

Security as protection of welfare mechanisms

Security can further be defined along the various welfare mechanisms put into place by community members. For the present discussion, this concept shall encompass both contributing and non-contributing welfare mechanisms. Contributing mechanisms are funded by the individuals having the right to claim them after a specific period of contributions. By contrast, non-contributing mechanisms are generally paid through general taxes and government budgets and can be claimed independently of one’s own contribution. These mechanisms are considered as common resources that the community can prima facie distribute according to rules, which it sees adequate.Footnote21 Security as protection of welfare mechanisms is often handled together with discussions on the impact of immigration upon the job market. If immigration patterns could be shown to negatively impact resident workers (Japanese and non-Japanese), this could, in turn, have detrimental consequences for welfare mechanisms (e.g. unemployment).

In this context, the key criterion of these welfare mechanisms is their relative openness towards newcomers, for instance immigrants but also new members of an age to actively participate in society (e.g. young adults starting their professional life). Clearly, not every mechanism is organized along a similar rule. For instance, public assistance to alleviate poverty does not work the same way as an insurance scheme to which the person is supposed to contribute beforehand.Footnote22 For the present argument, we focus on public-funded welfare mechanisms for situations of individual urgency (seikatsu hogo). The legal foundation for these mechanisms is usually seen in Art. 25 of the Constitution, protecting minimal standard of living.Footnote23 There is controversy as to whether this right is limited to Japanese nationals (as operationalized in Welfare Law) or whether non-national residents can also claim support. A decision of the Supreme Court in July 2014 stated that ‘foreigners do not possess the right to receive assistance based on the law and are only limited to being subjects for public assistance in a practical sense based on administrative decisions.’Footnote24 This ruling was met with controversial reactions, highlighting that the distribution of public resources to individuals in need (especially non-Japanese) is highly sensitive.Footnote25 Private insurance companies as usual in the Japanese corporatist tradition can be left aside.

In addressing welfare mechanisms as justification, it is important to examine a ‘collapse’ argument (the ‘worst case scenario’ of a massive increase of individuals who claim support from the welfare state) and a ‘strain’ argument (the welfare mechanisms come under pressure, but do not collapse) (Cole, Citation2000, p. 148 ff.).

The main problem of the collapse argument does not rely upon its normative component, but upon the very demanding empirical premise. The normative component of the argument considers that the collapse of the welfare system cannot be in the interest of either the members of the community or the potential migrants. The empirical component of the argument has to demonstrate the plausibility of an immigration movement leading to this collapse. If this case can be made for Japan (due to the Korea crisis, for instance), the argument will partly merge into the security argument discussed above.

However, the specificity of the welfare argument is that it makes clear why we need to distinguish between presence on the territory and access to welfare mechanisms. On the one hand, it corresponds to security understood as public order (if the mere presence of a number of individuals threatens the foundations of the state). On the other hand, it echoes to a distinct understanding of security focused on the financial resources of the state. If too many individuals claim support from the Japanese state, it might be justifiable to restrict access to welfare mechanisms. But here as well, like in the security as public order argument, the threat must be proven fundamental, and that it would put the foundations of the Japanese welfare state in danger. Otherwise, it is only a variation of the ‘strain’ argument, which will be discussed below.

In contrast to the ‘collapse’ arguments, the ‘strain’ argument appears as empirically more realistic and normatively challenging to address. The main normative challenge is a challenge of redistribution and exclusion: is it justifiable for Japanese citizens to redistribute resources in priority to themselves and to exclude potential immigrants who want to become part of the Japanese economy? Similarly, is it justifiable to prevent further immigrants to enter the country if they directly compete with resident workers?

It is important to note that this specific redistribution challenge becomes relevant only in the case where an immigration policy amounts to increasing economic burdens. In other words, the argument rests upon an unspoken empirical premise: immigration is bad for welfare mechanisms (and for the job market). On the contrary, if immigration is beneficial to the welfare mechanisms (by bringing more resources in than out through increase of paid taxes and other economic positive effects), there could hardly be an argument based on the protection of welfare mechanisms. In this case, the ‘strain’ argument has no relevance. Indeed, the argument could even be reversed and become a duty to attract more immigrants (if it is shown to have positive effects on public finances).

It is important to note that this unspoken empirical premise upon which the argument relies is at the very least a questionable premise in the context of Japan (Shimasawa & Oguro, Citation2010). There is a structural explanation specific to Japan: because it (officially) implements a highly selective labour immigration policy, it first and foremost accepts immigrants who have a strong capacity to contribute to the national economy and public finances. This ambition is at the core of the ‘official’ immigration policy as currently defended by the Abe government (and as enacted by Shutsunyūkoku kanri oyobi nanmin nintei hō, the Immigration Control Act). As expressed in Abe’s strategy paper ‘Nihon saikō senryaku: Japan is Back’ (July 2013), labour immigration is clearly grasped as temporary stays for the sake the Japanese economy. This general stance towards labour immigration is symbolized by the ambition to ‘activate international human resources’ (Vogt, Citation2017a, p. 81). A similar link between immigration and economic contribution seems to hold true even if we widen the scope of investigation and consider the four side-doors to this ‘official’ immigration policy: the students’ economic activities, the Nikkeijin regulation, the foreign trainees programme and the bilateral economic cooperation (Chiavacci, Citation2014; Chung, Citation2014; Hammouche, Le Bail, & Mori, Citation2013; Vogt & Behaghel, Citation2006). Every side-door highlights a distinct, but consistent link between the admission to stay and work in Japan and the economic ‘usefulness’ of potential immigrants.

This structural specificity explains also why effects on the Japanese job market tend to be positive (Nakamura, Citation2010).Footnote26 Indeed, the demography-based discourse underlines that the Japanese job market needs more individuals able to work (Akashi, Citation2014).Footnote27 If this is true for Japan in general, this does not exclude specific situations of pressure on employment, especially for residents being in direct competition with new-comers (so called ‘substitutes’).Footnote28 It is interesting to note that this pressure-effect is only noticeable in situations of direct substitutability, meaning that if immigrants are not in direct competition with residents (similar competences), no such effect will occur. Furthermore, it is important to see that these displacement effects are likely to be temporary and that situations will tend to converge in the mid-term (Kerr & Kerr, Citation2011, pp. 9–10).Footnote29

The counter example to this positive correlation between Japanese labour immigration and economic impact is the field of asylum. In this field, the criterion of economic contribution is presumed irrelevant, being replaced by the criterion of vulnerability and need for protection. But Japan has very few asylum applications, and only accepts a tiny minority (Wolman, Citation2015). It might not plausibly be claimed that these few individuals represent a danger for the welfare contributions or for the employment market. Overall, there is a strong structural ground to think that immigration policy as currently regulated by Japan is beneficial to public finances rather than detrimental.

For the sake of argument, let us nevertheless assume that immigration is negative for welfare mechanisms and for the employment market. With this assumption, the previously mentioned challenge becomes relevant: under which conditions is it legitimate for Japan to claim (1) to keep its resources for its current population and (2) to prevent immigration on such grounds? In order to reserve and protect its financial security, Japan claims a right to exclude potential immigrants.

Following Scheffler’s analysis, this question bears upon the legitimacy of the priority-giving scheme among fellow members from the point of view of outsiders (Scheffler, Citation2001, p. 54 ff). This objection puts the group’s relationships (Japan in our case) into a larger perspective by stressing the exclusion effects of such special prerogatives. It forces us to widen the investigation and specify in which sense Japan might be said to have responsibility towards outsiders. In order to concretize the tension at stake, imagine that Japan claimed that any negative effect on its public finances due to immigration (even the smallest cost) could be rightly used as an argument to stop immigration.

This argument relies upon two arguably problematic elements. First, Japan implicitly claims that any cost bearing upon its public finances can be used as a justification to prevent immigration, i.e. to limit the freedom to move of potential immigrants. The normative conflict we need to face is a conflict between two a priori legitimate claims: the claim made by Japan to decide how to distribute public resources in the form of welfare mechanisms, but also the legitimate claim raised by potential immigrants and based upon their individual freedom to move. In the present contribution, we can only map the different elements to be taken into account when addressing these complex conflicts. On the one hand, we need to get a better view of the value of individual freedom to move. In most cases, this freedom to move has an instrumental moral value: to enjoy mobility serves the pursuit of morally valuable goals in one’s life. Among the most important, we can cite freedom to flee from a source of danger, to associate (both in private (marriage) and professional matters), which in turn relates to the freedom to lead a family life and the freedom to secure a decent level of subsistence for oneself by exercising a professional activity.Footnote30 It means that individual freedom to move can be more or less weighty (from an ethical point of view). For instance, claiming that any cost would provide a good case to refuse an asylum seeker seems hardly defensible: the value of the freedom to move in a life threatening case seems to trump monetary considerations. The challenging question is whether a case of normal labour immigration application does carry sufficient weight to trump these considerations (Rochel, Citation2015, p. 436 ff).

On the other hand, we need a better view on the other element of this conflict: the claim raised by Japan to keep its resources for its own population. Namely, this is a question about the general justice duty, which a state owes to every human being, even outsiders.Footnote31 On this point, it is interesting to highlight that Japan acknowledges having justice duty towards outsiders. This rationale appears clearly as the official justification for its programme of international ‘technical traineeship’. In brief, the programme foresees a temporary permit to stay in Japan and work as a trainee in a specific economic sector (Vogt, Citation2017a, p. 85). The rationale of the programme is officially to train foreign individuals, give them specific skills and competences, before sending them back home with the hope that they will contribute to the economic and social prosperity of their country of origin.Footnote32 Similarly, despite the fact that Japan virtually accepts no refugees, it does not contest that it has a justice duty towards persecuted individuals. It contests that the best way to help them is, in general, to grant them asylum. This might be true in exceptional cases, but, by default, there are other options in order to fulfil this duty of protection (like funding of the UNHCR).

For our argument, it means that the acknowledgment of justice duty towards outsiders is part of an immigration policy. Building upon this element, the normative challenges upon which further research is required are the following: first, we need a better definition of the global justice duty of Japan (by addressing the question: how much should be expected from Japan in terms of investment of public resources for justice beyond its borders?).Footnote33 Second, we need to investigate the link between what should be expected from Japan in terms of global justice and its relevance for the determination of its immigration policy.Footnote34 For instance, it might be plausible to argue that a labour immigrant coming from a developing country (to which Japan, arguably, has justice duty) should be accepted, even if there is a risk that this person could be detrimental to financial security. This financial risk is part of what could be expected from Japan as part of its justice duty.

Summarizing our reflections on security understood as protection of welfare mechanisms, we have highlighted the importance of an informed empirical discussion on the effects of current immigration on public resources. This includes discussion on the impact of immigration patterns on the employment market (and therefore, indirectly, upon welfare). There are strong structural grounds that explain why these effects are and should remain in globo positive. In this case, the ethical discussion about a potential threat on security is losing its relevance. If immigration can be shown to be a threat for welfare mechanisms, we have pinpointed the main points to be discussed. We need to specify the justice duty of Japan and the effects of this duty on what could be expected from Japan within its immigration policy. These two points represent the basis of a general, consistent account of justice duty in the context of immigration policy.

Security as cultural stability

Security can be further defined along cultural stability. In brief, the argument tends to take the following shape: Japan has the competence to control immigration because it is necessary to protect and foster Japanese culture understood in a broad sense.Footnote35 Japanese culture is identified as a putatively strong justification for the competence to control immigration (Vogt & Behaghel, Citation2006, p. 139).Footnote36 We will first try to define ‘culture’ before addressing its relevance in the context of Japan’s immigration policy. The main hypothesis is that, despite its intuitive strength, the protection of Japan’s culture fails to be a consistent justification in most circumstances.

There is a very rich literature on the definition of Japan’s culture. This literature addresses both methodological challenges (Sugimoto, Citation2009, pp. 1–20) and substantial perspectives ranging from sociological, historical, and anthropological investigations (Harumi, Citation2009). The objective of this article is not to engage with this work, but rather to map the ethical challenges linked to them. In that sense, these challenges bear upon distinct approaches to Japanese culture(s) and are to some extent independent (resp. compatible) from them.

For the sake of this discussion, our working definition of culture will refer to a set of features linked to the specificity of Japan as a political community and to how individuals understand and experience themselves as members of this community. This set of features encompasses a broad range of customs, habits and traditions, but also social norms ranging from shared history, language or religion to cultural production in a more conventional sense (e.g. works of art, oral or written traditions).Footnote37 None of the features from this non-exhaustive list is in itself necessary or sufficient to define culture. Rather, culture is understood as a configuration of these various features, which mark out a group of individuals.Footnote38 It is important to underline that we do not consider here what could be called ‘constitutional’ elements of the culture. For instance, the UNESCO definition considers ‘fundamental rights of the human being’ to be part of culture. This might be true, but for the sake of our present argument, these ‘constitutional’ elements are treated as part of the security as public order section.

This working definition of Japanese culture faces different difficulties. The most important pertains to the difficulty of positively defining what this set of features might encompass and navigate between stating the few but obvious features (say, the Japanese language and its multiple expressions) and trying to have a broader definition of culture which would immediately prove very contested. Without such a positive definition of what culture entails, the argument for the competence to regulate immigration as a means to protect this (indefinable) culture does not work.Footnote39

The second difficulty is inherent in the ambition to somehow isolate ‘a’ Japanese culture at a certain time T. Culture, as defined above, should be understood as the permanent re-production and re-appropriation of the goods and practices of a given community. Culture is a matter of permanently changing practices and cannot be crystallized at a point X without losing its core meaning.Footnote40 In the meantime, its use as justification for the immigration competence requires the capacity to pinpoint a certain state of the Japanese culture at a time T (a substrate which needs to be protected).

Third, it appears challenging to define Japanese culture in a way that matches the geographical borders of Japan. For culture being used as an interest in the context of an immigration argument, it is crucial to match the definition to the contours of Japan as a state. This task is faced with two standard difficulties: on the one hand, this shall prove difficult with respect to the immediate neighbours of Japan (e.g. Korea). It is the exclusivity of a putative Japanese culture which is here at stake. On the other hand, the issue of the internal diversity of Japan poses a great challenge to the argument. Does urban Tokyo have, in any meaningful sense, the same culture as Okinawa or the Hokkaido rural areas? The issue is not only an issue of the nationality divide (Japanese vs. non-Japanese residents), but among Japanese citizens on the basis of individual preferences.Footnote41 It might prove challenging to come up with a definition of culture which reflects the habits and practices of a vast majority of Japanese citizens.

Assuming for the sake of argument that these definitional difficulties can be overcome, we shall also deal with the relevance of culture as an argument in the context of immigration. We need to distinguish between the non-instrumental and instrumental lines of the argument. The non-instrumental relevance of culture is linked to the strict preservation of a culture that is conceived as valuable per se (Meilaender, Citation2001; Walzer, Citation1983).Footnote42 On the one hand, the promoters of the argument have to explain in which sense the community is entitled to reify a specific moment of a culture’s process of permanent evolution.Footnote43 On the other hand, promoters of the argument have to deal with the counterintuitive consequences of this argument (if found valid). This argument can namely be used against any phenomenon that changes the culture of Japan. This could mean culturally different immigrants. But more generally, it can be used as an argument against any technology-based changes. To give one example, the introduction of smartphones has changed the Japanese culture much more profoundly than any immigration policy could ever do. Nevertheless, calls for prohibitions of smartphones upon cultural reasons have remained scarce.

The instrumental case for the relevance of culture can take several forms. In its structure, it links the value of culture to its positive effects on other morally valuable interests (Bader, Citation2002, p. 162; Mona, Citation2007, pp. 352–358). Following the influential account provided by Kymlicka, culture as a set of shared practices represents a pre-condition for individuals to be able to lead an autonomous life (Kymlicka, Citation1995, Citation2001).Footnote44 If freedom implies the capacity for making choices among various options, then the societal culture is important not only because it provides its members with a range of options, but also because it transforms this bare material into meaningful options. Waldron provides an influential criticism of this idea, questioning the notion that access to a specific and unique culture (or some forms of culture) is crucial. What is essential could rather be the access to the societal culture which applies to one specific environment, but which is largely independent from the state one resides in (Waldron, Citation1995).Footnote45

In sum, the justification of the competence to regulate immigration on the basis of security understood as protection of the culture faces difficulties, which prove hardly surmountable. A more promising argument would focus on the value of cultural stability.Footnote46 The focus is shifted from the protection of culture to the protection of stability. The new focus is on the rhythm of changes, not on the changes themselves. This relative cultural stability – assuming that all definitional difficulties can be settled – can be deemed valuable to the community in that it allows it to plan evolutions in a more assured way. This represents a rejoinder to Kymlicka’s thesis. A relatively stable cultural and political life provides members of a community with an environment that allows them to make sense of the options they have and to see themselves as members of a given group. The interest of the community’s members is in enjoying a certain cultural stability.Footnote47 The focus of the argument is clearly on the pace of the evolution, not on their acceptability per se (Mona, Citation2007, p. 356). Interestingly, this can make the argument applicable to other types of ‘earthquake-kind’ revolutions (such as robotics). In the context of immigration, this interest is an argument for the prevention of a cultural revolution. It speaks against a rapid, profound and pervasive change in the culture of a community, what we could define as a sort of cultural earthquake. But if immigration is to occur in a controlled and non-overwhelming way, there seems to be no strong argument as to why a culture should be immune to slow and altogether normal evolution.

However, assuming that the interest in preserving cultural stability is legitimate, its empirical relevance is limited.Footnote48 In Japan today – and even if the immigration policy was to become more open – there is no significant threat of revolution to a putative Japanese culture(s).Footnote49 Indeed, because Japanese culture(s) is very protected due the Japanese language (working as a ‘natural’ barrier), the perspective of a profound and rapid change seems far remote.

Protection of social trust

The security argument can be understood as bearing upon the protection of a kind of ‘social trust’ among community members (Bilgiç, Citation2013; Carens, Citation2010, p. 23 ff.; Cassee, Citation2016, p. 157 ff; Christiano, Citation2008, pp. 955–960; Macedo, Citation2007; Miller, Citation2016, p. 64 ff; Pevnick, Citation2009). This ‘social trust’ relies on a multitude of elements related to the broad identity of a community. The argument is mainly negative in its structure. Without this social trust, important institutions such as the welfare system or an operational democracy are unable to function properly. Their functioning is claimed to rely upon members sharing some kind of trust and conviction about a common valuable project.Footnote50 In the context of the justification for Japan’s competence to regulate immigration, it must be shown that this competence is required for social trust to be safeguarded. The argument faces a range of empirical and normative difficulties.

First, it might be empirically contested that the existence of social trust is necessary for the functioning of public institutions. This article is not the place to engage in the extensive empirical literature on this issue, but only to highlight structural challenges.Footnote51 As proposed by Pevnick, there are good reasons to argue that the functioning of institutions at least partially depends upon the way these institutions are conceived and implemented rather than upon people’s ability to identify with them as part of a common societal project (Pevnick, Citation2009, pp. 148–150). The conditionality between trust within a political community and functioning public institutions might not be unilateral. Well-functioning institutions might themselves produce or at least reinforce the trust they need. This point does not negate the fact that trust is an important feature within personal networks (Lenard, Citation2008). It does question its empirical relevance as an argument for the sustainability of public institutions.

Second, assuming that the empirical case for the necessity of social trust can be made, the main difficulty is its underlying normative assumption. Social trust is a set of attitudes and expectations held by community members vis-à-vis other members of the community and the functioning of their common public institutions. In the context of immigration, the argument seems to be the following: if immigration increases, the confidence putatively shared by members will erode in a way that makes the functioning of institutions impossible. The argument relies upon a self-fulfilling prophecy. The ‘fact’ that letting potential immigrants enter would undermine social trust relies upon the attitude adopted by community members. For instance, Vogt notes that a significant number of Japanese (36.3%) think that it would be better not to live in the vicinity of foreigners (as reported in the World Value Survey 2010–2014) (Vogt, Citation2017a, pp. 89–90). Proponents of the social trust justification tend to extrapolate this kind of finding and highlight that this trend is detrimental to the functioning of public institutions and that, therefore, immigration should be banned.

From a normative point of view, this justification is problematic. The attitude is objectionable in the first place, because it is inconsistent with values to which Japanese citizens have committed themselves through their Constitution. As explained by Lenard, this attitude represents a chosen political act of discriminatory and exclusionary policy (Lenard, Citation2012, p. 102 ff). This act tends to destroy the social trust that it claims to protect in the first place, but the main problem is that this act is a chosen act, for which individuals bear responsibility.

Overall, this argument only asserts a prediction according to which detrimental consequences would occur because of the attitudes adopted by the people asserting the argument. In its structure, the argument is similar to the prediction expressed by a racist saying that if more ‘Black’ immigrants are accepted, they will organize a riot and that, as a consequence, social trust might decrease. The attitude, freely chosen and adopted by this racist person, is problematic in the first place and might not be used as justification for public policy. As Carens states, ‘from a normative perspective, it matters enormously whether the unwillingness to support the welfare state grows out of morally objectionable attitudes such as racism or other forms of prejudice or simply out of what one might call legitimate indifference to the well-being of these new arrivals’ (Carens, Citation2010, p. 23). If we assume the sociological definition of ‘political trust’ proposed by Lukner and Sakaki (entailing perceived performance, evaluative orientation, normative expectations, political legitimacy), we might locate the main normative problems within ‘evaluative orientation’ and ‘normative expectations’ (Lukner & Sakaki, Citation2017, p. 4). If the evaluation orientation by citizens towards public institutions’ performances is based on ethically objectionable criteria (such as racism), their assessment of political trust will be faulty. The same holds true for their normative expectations if the promises and commitments of the government are assessed on the basis of objectionable expectations. Both dimensions highlight the inconsistency between values otherwise promoted (such as those found in the Constitution) and individual predictions.

To argue for a solid normative case, two options are available. The first one is about addressing the inconsistency by changing the values and principles accepted in the first place (i.e. by removing commitment to equality or freedom). Nevertheless, an ethical criticism based upon equality or freedom as universal values would remain. The second option is to show that the detrimental effects potential immigrants would imply for the social trust do not depend, in a relevant way, on the decisions made (intentionally) by members of the community. Because this reaction is automatic (and hence non-chosen), their responsibility is not triggered.

If this mechanistic reading were proven cogent, this interest would then be legitimate in the very specific circumstances in which the rapid and massive arrival of potential immigrants automatically puts the social trust at risk. This argument would merge into the cultural stability argument, by focusing on the rhythm of evolution.Footnote52 However, it must be noted that this argument represents a strong interest community members might assert towards potential members (i.e. potential co-citizens), and not towards potential immigrants (Pevnick, Citation2009, p. 154 ff.). The instrumental case for social trust is made with respect to key institutions to which potential migrants might not automatically have immediate access (such as access to the welfare system after a period of contribution).

To summarize the ‘social trust’ variant, it appears to suffer from empirical challenges as well as normative deficiencies. The argument fails to provide justification beyond a self-fulfilling prophecy, which relies upon objectionable attitudes and behaviours in the first place. These deficiencies make this argument inconsistent with the values and principles chosen by Japan.

Conclusion

We have dealt with four distinct understandings of security relevant for the Japanese immigration context. First, this discussion makes clear that, because of its instrumental structure, a protection argument does not succeed in justifying an all-encompassing competence on immigration. In specific cases, it only justifies a particular competence, which is essentially a competence to stop immigration in case of danger. This is important because, on the basis for this security-based argument, it drastically reduces the perimeter of an ethically justifiable competence to control immigration. As was shown, security-based arguments might justify a screening competence (a competence to assess potential threats) and a set of ‘emergency-brake’ competences relying on a threshold structure. But it cannot justify the competence claimed by Japan to choose a policy of highly skilled immigration or the distinct side-doors let open by the government more or less willingly. In its structure, this claim requires another type of argument based on a general claim to political self-determination. However, for our present investigation, it is important to note that this distinct type of argument does not rely upon security as key argument.

Second, our analysis of the security arguments has shown that the interests that would be empirically more plausible are, from a normative point of view, more difficult to defend. Security understood as public order is normatively very convincing, but its empirical relevance is limited to very specific cases. The competence it might justify is hence equally limited in its relevance. By contrast, security understood as protection of the welfare provisions could be empirically more relevant, but it is normatively more disputed and needs a careful argumentation, which necessitates that numerous other elements be clarified.

Third, as explained in the methodological remarks, we had assumed a provisionally given frame of reference on the basis of the values entailed by the Japanese Constitution and the international commitments made by Japan. As made clear by the argument, the field of immigration policy does not escape from this requirement of consistency. Japan cannot claim to be a sovereign land that regulates immigration as it sees fit without constraints. It is bound by the very values and principles which it is committed to. These constraints are of legal nature (which was not the focus of the article), but most importantly of ethical nature. This article has focused on the values of equality and freedom, while arguing for the relevance of global justice duties in assessing immigration policy. Our reflections on immigration policy show that an understanding of freedom and equality, which is only focused on residents (citizens or not) is not complete. The demands raised by immigrants challenge every political community by provoking a necessary reflection on the importance it ought to give to the freedom and equality of ‘outsiders’. Our discussion of each of the four understandings of security brought evidence of this process: each argument claimed by Japan has implications beyond its borders. Individuals affected by Japan’s decisions should somehow be taken into account.

Our reflection also makes clear that this exercise of applied consistency has a strong political dimension. It might be the task of political philosophy to challenge specific policies and their justification, but it is the task of citizens to address this challenge as part of their political prerogatives. In other words, Japanese citizens should make sure that their country has an immigration policy that addresses its ethical challenges. In addressing these challenges, Japan should aim at what Cohen-Eliya and Porat call a ‘culture of justification’. As they write, ‘at its core, a culture of justification requires that governments provide substantive justification for all their actions, by which we mean justification in terms of the rationality and reasonableness of every action and the trade-offs that every action necessarily involves’ (Cohen-Eliya & Porat, Citation2011, pp. 466–467). This culture of justification is indeed relevant with respect to Japanese citizens. But it is at the same time decisive that outsiders and other political communities affected by Japan’s immigration policy be integrated into this culture of justification. Hence, the justification for Japan’s immigration policy can only be the product of a vast public debate among Japanese citizens, while integrating the views of individuals affected by Japan’s choices in immigration. The argument presented here is a modest contribution to this very challenging societal and political debate on the consistency between the values chosen by Japan and its concrete policy choices.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues at the Institute of Social Science at the University of Tokyo for their comments on an earlier draft. Special thanks to Gracia Liu-Farrer, Gregory Noble, Glenda Roberts, Konrad Kalicki, Magali Ntongo, and Stefan Heeb

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Batchelor, T. (Citation2017, November 20). Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe refuses to relax immigration rules despite shrinking population. The Independent. Retrieved 17 May 2018, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/japan-immigration-shinzo-abe-refuse-relax-rules-prime-minister-policy-shrinking-population-foreign-a8065281.html

2 See Usuda, K. (Citation2017, October 20). Abe’s ‘Japan First’ immigration policy. Japan Today. Retrieved 17 May 2018, from https://japantoday.com/category/features/opinions/abe’s-‘japan-first’-immigration-policy

3 There is an important literature focusing on the USA, see e.g. Macedo (Citation2007). For the case of the EU, Rochel (Citation2015); Märker and Schlothfeldt (Citation2002). For France, Weil (Citation2005).

4 On this structural distinction in the case of the EU, see Bast (Citation2011, p. 269 ff). For a similar choice, see Märker (Citation2005). For a different choice in dealing with Japan’s immigration policy, see Komine (Citation2014).

5 For the investigation of the link to racial considerations, see Iwata and Nemoto (Citation2017).

6 For a defence of this claim (and its link to the issue of jurisdiction), see Rochel (Citation2015, p. 322 ff).

7 The use of the term legal could be said, from a terminological and semantic point of view, to reinforce putative commonalities between immigration, illegality and security matters (Cholewinski, Citation2007, pp. 305–306); Düvell (Citation2005, pp. 14–15). For irregular immigration and ethics, see Carens (Citation2013, pp. 129–157).

8 For an overview of the debate, see Düvell (Citation2005, p. 14 ff).

9 The political ambition of the political community to concretely control immigration should also be taken into account; see Motomura (Citation2008, p. 2054).

10 For an overview on the distinct ethical questions at stake, see Rochel (Citation2016).

11 Follesdal writes that normative legitimacy is ‘often expressed in terms of justifiability among political equals’ (Follesdal, Citation2008, p. 380). For a similar approach, see Dobson (Citation2006, p. 523).

12 See also Scanlon (Citation1998, p. 45).

13 For a philosophical-legal qualification of these values, see for instance Inoue (Citation2011, pp. 328–329). For the specificity of constitutional adjudication in Japan and the correlated values, see Haley (Citation2011).

14 This specific example is linked to a utilitarian argument. In the context of immigration ethics, see Carens (Citation1987); Wellman (Citation2010, p. § 2.4).

15 For definitional work, see Cameron (Citation2000, p. 39 ff.). For a comparative approach, see Schmid-Drüner (Citation2007).

16 This formulation is inspired by EU case law on interpreting threats to public order. Régina v Pierre Bouchereau (Citation1977, p. § 35); Commission of the European Communities v Kingdom of Spain (Citation2006, p. § 46); Commission of the European Communities v Kingdom of the Netherlands (Citation2006, p. § 43).

17 As noted by Bast (Citation2011, pp. 79–81), it is also clear that this argument has provided – and still does – the fundamental rationale for the securitization of immigration matters, from the ‘Fremdenpolizei’ to high-tech control mechanisms at the borders.

18 For the ethical formulation, see Carens, (Citation1987, p. 259 ff.). For the use of this war-like discourse on foreign invasion, see Chiavacci (Citation2014, p. 131 ff).

19 See Staff and Agencies. (Citation2017, November 16). North Korea nuclear crisis: Japan bracing itself for influx of evacuees if war erupts. The Independent. Retrieved 17 May 2018, from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/north-korea-crisis-latest-japan-evacuees-influx-nuclear-war-shinzo-abe-kim-jong-un-missile-tests-a8058151.html

20 Pursuant to its Art. 25. A Website of the European Commission lists the current internal controls in force and their justification: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen/reintroduction-border-control_en

21 This formulation shall not give the impression that the resources that are to be distributed are in any sense fixed (as in a cake-style example, where a cake is to be distributed among more and more individuals). These resources evolve, not least due to immigration. Furthermore, as rightly noted by Oberman, the amount of resources that might be used by the community is not a disjunctive choice between giving more to one’s members or engaging these resources for their background obligations or for newly accepted immigrants (Oberman, Citation2014, p. 32).

22 For an overview of the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, refer to Social Security in Japan (Citation2014), pp. 7–8. For the broader framework of social justice in Japan, see Akimoto (Citation2014).

23 Art. 25 reads as follows: ‘All people shall have the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living. In all spheres of life, the State shall use its endeavours for the promotion and extension of social welfare and security, and of public health’.

24 Quoted from Richards (Citation2014). Japanese Supreme Court Rules Against Foreign Residents on Welfare. The Diplomat. Retrieved 17 May 2018, from https://thediplomat.com/2014/07/supreme-court-makes-foreigners-second-class-citizens/

In brief, foreigners are treated on the basis of an analogy with Japanese nationals. One implication of this decision is that they have weaker rights of appeal against a negative decision.

25 See for instance, Richards (Citation2014). Japanese Supreme Court Rules Against Foreign Residents on Welfare. The Diplomat. Retrieved 17 May 2018, from https://thediplomat.com/2014/07/supreme-court-makes-foreigners-second-class-citizens/ .

26 See the previsions based upon 150,000 immigrants per year by Shimasawa and Oguro (Citation2010).

27 See also Chiavacci (Citation2014, p. 117 ff).

28 For an example in the European context, see Nijkamp, Poot and Sahin (Citation2012, pp. 26–29).

29 Literature on the European context suggests that residents’ professional career might take benefit from the presence of newcomers. See D’Amuri and Peri (Citation2014).

30 See Lenard (Citation2010); Carrera, Faure-Atger, Guild, and Kostakopoulou (Citation2011); Oberman (Citation2014); Pécoud and de Guchteneire (Citation2006).

31 ‘The force of the distributive objection to special responsibilities among compatriots therefore depends entirely on how we specify the general responsibilities that obtain beforehand’ (Miller, Citation2007, pp. 42–43). See further what Miller calls ‘weak cosmopolitanism’ (Miller, Citation2016, pp. 20–38).

32 The wording used by the Japan International Training Cooperation Organization is very clear:

‘There is a need to provide training in technical skills, technology, knowledge from developed countries (hereinafter, referred to as “Skills”) in order to train personnel who will become the foundation of economic and industrial development in developing countries’. (http://www.jitco.or.jp/english/overview/itp/index.html) (accessed 1 December 2017).

33 This question opens the wide field of debates on the best understanding of global justice. For a Japanese perspective, see Inoue (Citation2013) For a discussion, see Takikawa (Citation2015).

34 For a formulation of a strict conditionality thesis if justice duties are not fulfilled, see Schlothfeldt (Citation2002, p. 105 ff.); Wilcox (Citation2007, pp. 5–7).

35 For contributions focused on the issue in the ethics of immigration, see Scheffler (Citation2007); Rüegger (Citation2007); Miller (Citation2005); Sager (Citation2008); Perry (Citation1995); Mona (Citation2012); Mona (Citation2007, p. 352 ff.); Lenard (Citation2010).

36 Specifically, discriminatory policy justified upon cultural reasons might be relevant in this context. See Humbert (Citation2010).

37 This definition reflects the definition of culture adopted by UNESCO in Mexico in 1982 at the World Conference on Cultural Policies: in its widest sense, culture may be said to be the whole complex of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a society or social group. It includes not only the arts and letters, but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, value systems, traditions and beliefs.

38 Kymlicka uses the concept of ‘societal culture’ in a similar way. See Kymlicka (Citation1995). For a distinction between ‘general’ culture and ‘societal’ culture, see Sager (Citation2008, p. 71).

39 To see the difficulties at stake, compare with the attempt by Huntington (defining the US culture as an Anglo-protestant culture threatened by the Hispanics) (Huntington, Citation2004).

40 According to Scheffler, to safeguard this capacity of the culture to evolve is a key for its preservation. Scheffler (Citation2007, p. 109). Similarly, see Waldron (Citation1995); Benhabib (Citation2002).

41 As noted by Vogt, ‘it comes as a surprise that Japan, in 2006, should pick multiculturalism as its very model to achieve social integration, i.e. cohesion in times of an increasing diversity’ (Vogt, Citation2017b, p. 80).

42 Seglow has labelled this view a ‘communitarian’ defence of the right of the state to restrict immigration for cultural reasons (Seglow, Citation2005, pp. 320–321). For similar labelling and criticism, see Mona (Citation2012, p. 152 ff.).

43 Scheffler calls them ‘cultural preservationists’ (Scheffler, Citation2007, pp. 102–103). See also Perry (Citation1995, pp. 115–116).

44 This argument might be said to be broadly shared by liberal-nationalists, such as Tamir (Citation1995); Margalit and Raz (Citation1990).

45 For a similar criticism, see Scheffler (Citation2007, p. 99 ff.); Seglow (Citation2005); Rüegger (Citation2007, p. 115).

46 For a related distinction between cultural ‘continuity’ and cultural ‘rigidity’, see Miller (Citation2005).

47 Lenard notes that it would therefore be false for promoters of a more open borders policy to try to negate the relevance of culture altogether. Culture is also relevant for potential migrants’ mobility (Lenard, Citation2010, p. 638).

48 For a similar structure in this argument, see Wellman (Citation2010). For a similar conclusion regarding the empirical relevance, see Sager (Citation2008, p. 77); Abizadeh (Citation2006, p. 4).

49 In the immigration context, the number of non-Japanese residents might be taken as a proxy for this hypothesis. See Vogt (Citation2017b).

50 For the example of democracy and the required trust in electoral systems, elected representatives but also minority protection, see Lenard (Citation2012).

51 For conceptual clarifications and references to Japan’s context, see Lukner and Sakaki (Citation2017). For the issue of political trust in Japan, see Krauss, Nemoto, Pekkanen, and Tanaka (Citation2017). For methodological reflections on the measurement of trust, see Bauer and Freitag (Citation2017).

52 This might be especially important in the context of highly contextualized trust-relations experienced by Japanese. See Inoguchi (Citation2002, p. 383).

References

- Abizadeh, A. (2006). Liberal egalitarian arguments for closed borders: Some preliminary critical reflections. Ethique et économiques/Ethics and Economics, 4(1), 1–8.

- Akashi, J. (2014). New aspects of Japan’s immigration policies: Is population decline opening the doors? Contemporary Japan, 26(2), 175–196.

- Akimoto, T. (2014). Social justice in an era of globalization: Must and can it be the focus of social welfare policies? Japan as a case study. In M. Reisch (Ed.), Routledge international handbook of social justice (1st ed., pp. 48–60). New York: Routledge.

- Bader, V. (2002). Praktische Philosophie und Zulassung von Flüchtlingen und Migranten. In A. Märker & S. Schlothfeldt (Eds.), Was schulden wir Flüchtlingen und Migranten? Grundlagen einer gerechten Zuwanderungspolitik (pp. 143–170). Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Bader, V. (2005). Constellations. The Ethics of Immigration, 12(3), 331–361.

- Bast, J. (2011). Aufenthaltsrecht und Migrationssteuerung. (Habil -Schrift Univ Frankfurt am Main, 2010). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Batchelor, T. (2017, November 20). Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe refuses to relax immigration rules despite shrinking population. The Independent. Retrieved May 17, 2018, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/japan-immigration-shinzo-abe-refuse-relax-rules-prime-minister-policy-shrinking-population-foreign-a8065281.html

- Bauer, P. C., & Freitag, M. (2017). Measuring trust. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The oxford handbook of social and political trust (online publication). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Benhabib, S. (2002). The claims of culture: Equality and diversity in the global era. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bilgiç, A. (2013). Rethinking security in the age of migration: Trust and emancipation in Europe. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Cameron, I. (2000). National security & the European convention on human rights. The Hague: Kluwert Law International.

- Carens, J. (1987). Aliens and citizens: The case for open borders. The Review of Politics, 49(2), 251–273.

- Carens, J. (1992). Migration and morality: A liberal egalitarian perspective. In B. Barry & R. E. Goodin (Eds.), Free movement: Ethical issues in the transnational migration of people and money (pp. 25–47). University Park: Harvester-Wheatsheaf and Penn State University Press.

- Carens, J. (2010). Open borders and the claims of community. Washington: APSA 2010 annual meeting paper (pp. 1–55).

- Carens, J. (2013). The ethics of immigration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carrera, S., Faure-Atger, A., Guild, E., & Kostakopoulou, D. (2011). Labour immigration policy in the EU: A renewed agenda for Europe 2020. CEPS Policy Brief, 240, 1–15.

- Cassee, A. (2016). Globale Bewegungsfreiheit - Ein philosophisches Plädoyer für offene Grenzen. Berlin: Surkhamp.

- Castles, S. (2004). Why migration policies fail. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(2), 205–227.

- Chiavacci, D. (2011). Japans neue Immigrationspolitik: Ostasiatisches Umfeld, ideelle Diversität und institutionelle Fragmentierung (1. Aufl. ed.). Wiesbaden: VS.

- Chiavacci, D. (2014). Indispensable future workforce or internal security threat? Securing Japan’s future and immigration. In W. Vosse, V. Blechinger-Talcott, & R. Drifte (Eds.), Governing insecurity in Japan: The domestic discourse and policy response (pp. 115–140). London: Routledge.