ABSTRACT

The image of Japanese mainstream media reporting is dominated by the institution of “press clubs”. Critical researchers argue that these restricted and institutionalized links between mainstream media and their sources lead to uniformity in media reporting. Other researchers contend that Japanese journalists play diverse roles and frame issues in diverse ways. These contrasting theses are explored through an analysis of three major newspaper's framing of nuclear power in article series (rensai). First, we construct a set of frames of the nuclear power issue out of materials from two political alliances: the pronuclear alliance (the so called “nuclear village”), and the antinuclear alliance. We apply and adapt these frames using a sample of newspaper article series from 1973 to 2014. The comparison shows that there are significant differences of reporting both between newspaper organizations as well as between different periods. Especially for the phase after 2011, reporting turns pronouncedly nuclear-skeptical in two newspapers. While not denying press club influence, the analysis cautions against mechanically applying a distinction between “insider” and “outsider” media and calls for new analytical categories to explain the substantial differences of framing between journalists of various “insider” media organizations.

Introduction

Research on the political role of Japanese media is often concerned with the institution of the press clubs (Hayashi & Kopper, Citation2014, p. 1142). Press clubs are spaces for journalists installed in various ministries, party headquarters and big companies or business federations. Major media companies dispatch journalists to the most important press clubs to cover important sources (for instance, the Prime Minister’s Office) around the clock. The journalists receive briefings and reports from public relations managers and gain access to sources directly in press conferences and informal background meetings (Freeman, Citation2000). Freeman argues that the restriction of access to major media companies and the benefits journalists receive in these clubs lead to a strong pro-elite bias of media reporting. Other authors challenge this view and see a more diverse or oppositional role of Japanese mass media (e.g., Kabashima et al., Citation2010).

Table 1. Pronuclear frames. The “Japanese frames” are displayed in italics

Table 2. Antinuclear frames

In this article we explore both theses by analyzing the framing of nuclear power by two political coalitions and comparing it with the framing in Japanese newspapers. We outline the historical development of the political alliances a) promoting nuclear power in Japan, and b) opposing it. In terms of control of press clubs, the pronuclear alliance is much stronger than the antinuclear coalition. To see how this dominance plays out in media framing, we construct a set of frames. We follow Gamson and Modigliani (Citation1989, p. 3) defining a frame as a “structuring principle that journalists use when producing news”. A frame is a cluster of symbols, arguments, images and reasonings showing up repeatedly in a text or movie. To test the press club hypothesis we construct the frames out of materials from the two political groups (appendix one). These frames differ to some degree from existing content analyses of the Japanese nuclear power debate. We argue that analyzing framing on the basis of statements by political coalitions and comparing these frames with the framing in newspapers (instead of only relying on newspaper content to construct the frames), enables us to more precisely depict key cleavages in the nuclear power debate over a long period of time. Comparing these frames with different newspapers’ framing enables us to assess which coalition was able to dominate the news. The construction of the frames as such is a contribution. We also added new “journalistic frames” which were not found in the statements from the political coalitions, when the frames from the political actors did not seem to adequately reflect the newspapers’ framing. The comparison shows that the influence of political coalitions on framing differs by newspaper, especially after 2011. To enable us to limit the sample over a long period of time, the newspaper articles (appendix 3) were limited to article series (rensai), a category mixing news and background reports. We do not claim to show that press clubs do not have any influence, since we would expect their influence most strongly in straight news (for a detailed discussion see section 5). However, the analysis shows that press clubs cannot be regarded as the decisive influence on the framing in article series on nuclear power, because all newspapers in the sample are represented in the same press clubs.

Theories of the political role of Japanese mass media

Studies of Japanese mass media differ in their assessments of the media’s political role. A large body of research is critical of close relations between elites in government, business and the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Besides Freeman (Citation2000), many media researchers,Footnote1 media criticsFootnote2 like Iwase (Citation1998), but also journalists,Footnote3 criticize uniformity or lack of a critical stance.

Others challenge this view, arguing that Japanese media play different roles in debates concerning different policy issues. Pharr (Citation1996) develops the notion of journalists as “tricksters” adapting to different roles in different situations. Pharr and Krauss (Citation1996) scrutinize the role of journalism in the (short-lived)Footnote4 fall of the long-term LDP government in 1993. They identify journalism as one major factor that contributed to this development. Multiple researchers argue that since the 1990s the media became a driving force of a more open and pluralistic political system (Kabashima & Steel, Citation2010; Martin & Steel, Citation2008). Earlier studies similarly developed models of either media-pluralism (Kabashima & Broadbent, Citation1986; Reich, Citation1984), or, in a negative twist, criticized the media for “leftist bias” (Packard, Citation1966).

Nuclear power reporting in Japan

Similar arguments have been exchanged about nuclear power reporting. The debate intensified after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident. Multiple researchers argue that nuclear power was portrayed too positively during the accident (Mamoru Itō, 2012; Hanada, Citation2012; Kamide, Citation2016; Segawa, Citation2011; Yamada, Citation2013) and before 2011 (H. Itō, Citation2002). Others contend that Japanese media were relatively (Ōyama, Citation1999) or overly critical of nuclear power (Scalise, Citation2012; Tanaka, Citation2004). However, many of these assessments are not based on systematic content analyses. Most of the studies based on content analysis focus on editorials (shasetsu). The analysis of editorials indicates that a long-term shift towards more critical reporting took place from the 1950s to present in the Asahi Shinbun (H. Itō, Citation2005, Citation2005, Citation2009; Ōyama, Citation1999). A limited number of studies focusing on straight news show that reporting was relatively uniform during the immediate crisis of the Fukushima Daiichi accident (for TV: M amoruItō, 2012; for newspapers: Kamide, Citation2016; Segawa, Citation2011), but afterwards, polarization increased between different newspapers' editorials (Abe, Citation2015; H. Itō, 2012).

How do these differences fit with the press club literature? There are different positions in this literature on the stances of newspaper editorials. While Wolferen, Citation1989, p. 97, as cited in Takekawa, Citation2007, p. 63) argues that editorial stances differ (but only to conceal broader consensus), Hall argues that:

“The collaboration (and mutual monitoring) among club members themselves contributes to that virtual identity of layout and that bland, noncontroversial conformity of reportage and interpretation so often noted among Japan’s competing news organizations.” (Hall, cited in Freeman, Citation2000, p. 170)

So, while some authors writing about press clubs acknowledge variation in editorials, but assert uniformity in news coverage, others make us expect uniformity across different formats and titles. To explore these relations we constructed a set of frames to understand the Japanese nuclear power debate. For this purpose, we used materials from the pronuclear and antinuclear coalitions and a sample of newspaper articles.

The pronuclear and antinuclear coalitions

To determine the corpus from which the frames were constructed it is necessary to first describe the political alliances engaging in the nuclear power debate. The Japanese civil nuclear program officially started in 1954 at the initiative of a group of politicians including Shōriki Matsutarō, the owner of the Yomiuri newspaper group who became the first Minister of Science and Technology, as well as later Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro. They forged an alliance for developing nuclear power spanning across parties (the two precursors of the conservative LDP, Socialist Party, and even Communist Party; Katō, Citation2012) and sectors (scientists, politicians, journalists; Arima, Citation2008). This became the core of the so-called “nuclear village”, the network of companies, bureaucratic agencies, researchers, and private groups active in building a nuclear industry and promoting nuclear power (Kingston, Citation2012). Yoshioka (2011) points to the closed character of this network, comparing it to a military-industrial complex. In 1956, they created the Japanese Atomic Industrial Forum (JAIF). The emerging “nuclear village” included utility companies (TEPCO and others), manufacturers (like Toshiba), politicians and bureaucratic bodies (Science and Technology Agency (STA); Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI)) and coordinating forums (Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)) (Yoshioka, 2011). While there was no substantial political group arguing for abandoning civil nuclear energy production until the 1970s (this is true not only for Japan; Radkau, Citation2011), Japan was in a special situation because it had experienced the atomic bombings. This was one of the reasons why the nuclear power coalition put substantial effort in promoting civil nuclear power.

At the same time, a strong social movement against nuclear weapons developed in alliance with the Socialist Party (JSP) and the Communist Party (JCP). The movement split later and the parties built rival anti-nuclear-weapons organizations (Honda, Citation2005). A challenge to the Japanese civil nuclear power program emerged with the spread of the antinuclear movement to Japan in the 1970s. The JSP-affiliated anti-nuclear-weapons group (Gensuikin) positioned itself against the civil use of nuclear power (Katō, Citation2012). In this phase the antinuclear group Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC) was formed by critical scientists, most prominently physicist Takagi Jinzaburō, for instance. The antinuclear coalition was supported by the JSP-affiliated Sōhyō Union as well as various women’s groups (Honda, Citation2005). They organized lawsuits against the construction of nuclear power plants (which had increased since the 1960s). The antinuclear alliance was influenced by the new left student protests of the late 1960s and 1970s and published their views in magazines like Technology and Human (Gijutsu to Ningen; cf. Suga, Citation2012). The antinuclear coalition benefitted from a wave of citizen protests and environmentalism in the 1970s (Hasegawa, Citation2004). This trend coincided with the oil crisis of 1973 leading the pronuclear coalition to put increased effort into public relations campaigns. In 1969 the Japanese Atomic Energy Relations Organization (JAERO) was created by the former secretary of the JAIF (JAERO, Citation1994). Beginning in 1973 the Japan Productivity Centre (JPC), a public foundation based on an alliance between MITI, the business federations and the conservative (Dōmei) labor unions joined the efforts to market nuclear power (Weiss, Citation2019, pp. 111–179). With the increasing construction of nuclear power plants the JAIF also built up local Atomic Forums (Genshiryoku Kondankai) serving as communication and marketing bases.

From the 1980s on, a “new wave” of the antinuclear movements emerged. This time mobilization of women from the consumer movement, for example, organized in consumer cooperatives (Seikyō), contributed to the movement. Besides criticism by “citizen scientists” like Takagi, popular nuclear-critical books by Hirose Takashi and Kansha Taeko circulated widely (JAERO, Citation1994). From the 1990s on, environmental protection groups like Greenpeace Japan and FOE Japan joined the antinuclear coalition. Reacting to these trends, the pronuclear alliance used its existing network and financial resources to create a number of pronuclear “citizen groups” (Weiss, Citation2019). In the world of politics, the JSP had extended its opposition to nuclear weapons to include civil nuclear power after the Chernobyl accident in 1986. The JCP renounced its principally pronuclear stance in 2004 (Katō, Citation2012).

The 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident led to a revitalization of the antinuclear movement. Now, domestic environmental groups like the alliance Energy-Shift as well as entrepreneurs like Softbank CEO Son Masayoshi joined the effort to promote renewables and replace nuclear energy (Cassegard, Citation2018). Within both the DPJ and LDP, antinuclear groups gained strength. Consumer activists, critical scientists and environmentalists took to the streets in large scale-demonstrations (Masaaki Itō, 2012).

The framing of nuclear power by the political coalitions

With this landscape of movements and organizations in mind, we proceeded to construct a set of frames out of their statements and materials. We used a qualitative approach to framing, combining deductive and inductive elements. To ascertain some comparability we used the frames constructed by Gamson and Modigliani (Citation1989) in their influential paper on the nuclear power debate in the US. Because of differences in the cultural and political economic environment, it would be insufficient to simply try to find the US frames in the Japanese material. The cultural background in which the frames are used can be expected to differ to a considerable extent. Thus, we adjusted Gamson and Modigliani’s frames wherever they appeared insufficient to display significant aspects of the Japanese debate and constructed new “Japanese frames”. Because we do not use quantitative validity tests, we described the frame elements in depth and provided a codebook (appendix 2) to make the coding of the frames as transparent as possible (Matthes, Citation2007, p. 64).

Frames of the pronuclear coalition

The pronuclear frames were constructed out of PR material published by the pronuclear coalition from 1973 to 2014. This timeframe was chosen because the antinuclear coalition formed in the 1970s and the accidents of Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011 might have triggered significant changes. Of course, the coalitions published numerous materials during this period, but by combining existing analyses and primary sources we hope to achieve some degree of saturation.

For the pronuclear coalition we constructed six major frames, two of them having direct corresponding frames in Gamson and Modigliani’s codebook.

Gamson and Modigliani see Progress as one of the important frames in the nuclear power debate. Gamson (Citation1992, p. 240) underlines that this frame includes both a vision of steady development towards a better world aided by the development of new technologies, nuclear power being one of them, and the discursive separation of atomic bombs and electricity generation. Important symbols in this frame include records like numbers of kilowatt/hour of electricity production, the conquest and control of natural phenomena through science and technology (kagaku gijutsu) (for instance, the use of radiation in medicine and research), as well as heroic characters like scientists and technicians (in particular, the local workers in nuclear power plants frequently appear in PR materials). Another element of pronuclear PR is safety. Here the pronuclear coalition uses phrases like “multi-level-protection” (tajū bōgo) and “take all possible measures” (banzen wo kisu). shows a newspaper advertisement containing some of these symbols.

Figure 1. JAERO advertisement showing Progress elements, for example the separation of nuclear bombs and nuclear power (AS, Citation1974)

Gamson and Modigliani (Citation1989) also include arguments concerning economic growth and electricity prices in this category. We did, however, code this as a distinct frame and labeled it Economy. The pronuclear coalition often underlines the danger of erosion of the industrial base of Japan as a construction superpower (monozukuri taikoku). Also the threat of price hikes (neage) for consumers is a recurring theme in PR materials by the pronuclear coalition (see for an advertisement visualizing elements of this frame). In a positive twist of this frame, the pronuclear coalition underlines the chances of increasing exports by building up a dynamic nuclear industry.

A second pronuclear frame identified by Gamson and Modigliani is Energy Independence. This framing underlines the scarcity of natural resources. In this context, Japan is often labelled a “resource-poor country” (shigen shōkoku). The advertisement by JAERO from 1974 displayed in contains many Energy Independence elements:

Nuclear power is indispensable as a new energy source that replaces oil. Our country is scarce in resources (shigen ni toboshii) and always had to import large parts of its energy from foreign countries to keep its standard of living. But recently the oil price has risen and the world energy supplies could be used up within 30 years (…). New energy sources like solar power, nuclear fusion and hydrogen are promising, but they need much time and effort to be put to use. That’s why we have to gain a large part of our energy from nuclear power. (AS, Citation1974)

Figure 3. JAERO advertisement with Energy Independence elements. The bear symbolizes Russia as a threat to Japanese energy security (YS, Citation1975b)

Another important aspect of this framing are warnings of blackouts. Besides autonomy in terms of raw materials, autonomy in terms of technology is a recurring theme. In a 1977 newspaper interview with two managers from the nuclear industry they ask:

Has the Japanese nuclear industry developed the bad habit of depending on the US, and can it never become independent? (…). We must build more plants and gather experience to improve reactors. (AS, Citation1977)

Especially the fast breeder reactor, which is designed to produce plutonium out of uranium, and can re-use the plutonium produced in this way as fuel, was thought to create a nuclear fuel cycle (kaku nenryō saikuru) opening the path towards a completely independent energy production. It was often referred to as the “reactor of dreams” (yume no genshiro) by the pronuclear coalition (e.g., Arima & Sano, Citation1999, p. 83).

Besides these two frames, we identified three pronuclear symbol clusters that cannot be found in Gamson and Modigliani’s study of the US debate. We labelled one of them Nuclear Education. A central argument in this framing is that because of the historical experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese developed an irrational “nuclear allergy” against anything nuclear. Prime Minister Satō in 1969 used the metaphor to discredit protests against the stay of nuclear powered US military ships in Japanese harbors (referring to an allergy against nuclear weapons). Later, the pronuclear coalition used this metaphor to dismiss sentiments against nuclear electricity production (Hook, Citation1984). To cure the “allergy”, the pronuclear coalition calls for various kinds of Nuclear Education. Buzzwords are “radiation education” (hōshasen kyōiku) and “the right knowledge” (tadashii chishiki). A pronuclear NPO called Radiation Education Forum, founded in the 1990s with support from the pronuclear coalition, claims in its founding document:

Our aim is to strengthen the righteous judgement of citizens, build human capital in this field and improve school and social education. We will spread the right knowledge (tadashii chishiki) and contribute to the public good. (Radiation Education Forum [REF], Citation2010, p. 1)

Recurring themes in “radiation education” are also the existence of natural radiation and radiation in everyday life. Besides “radiation education,” the pronuclear coalition argues for “energy education”. The Japan Productivity Center for example, argues that especially housewives should be targeted with energy education. They should know how much energy they use and have sufficient knowledge about energy problems (Japan Productivity Center [JPC], Citation1996, pp. 22–23). Connections to everyday life serve as an educational device. The pronuclear coalition conducts energy cooking events pointing to the constant need for electricity in modern everyday life, for instance (Weiss, Citation2019). The Nuclear Education frame is based on the assumption that the spread of “the right knowledge” will lead to public acceptance of nuclear power and foster a general pronuclear consensus. If this idea does not materialize, the blame is put on either “the Japanese”, who are deemed ignorant, or on troublemakers like the antinuclear coalition:

(…) all of us first have to correctly understand what the problem of nuclear power means. The stance of the Japanese is to reject knowing about this right from the start. That’s why the nuclear power problem is not a simple energy problem, but a social problem. (S. Yamamoto, Citation1976, p. 1)

Connected to the idea of achieving consensus through Nuclear Education of the people is also a negative view of those who, in the view of the pronuclear coalition, pose obstacles to consensus, i.e. the antinuclear coalition (a picture symbolizing the negative view of conflict contained in Nuclear Education frames is shown in :

The quarrel (sawagi) about freedom of information (jōhō kōkai) (…) when the opponents clamor that information isn’t disclosed, or that the construction of a power plant is pushed through by force. All these are excuses helping them to find a reason for being against everything. (JAERO, Citation1994, p. 41)

Figure 4. JAERO advertisement showing Nuclear Education elements. The two characters of the word freedom form two fists, one labelled “pro” and the other one “anti”. The underlying assumption is that freedom without guidance or “education” by those who are in charge only leads to unnecessary quarrels (YS, Citation1975c)

Green Nuclear is another frame that does not appear in Gamson and Modigliani’s survey. The pronuclear coalition argues that nuclear power is a clean energy source, because it does not emit CO2 and does not cause oil leaks or the like in the process of energy production. A TEPCO newspaper advertisement from 1973 () shows a kid with a dog walking on a shoal. The sun is reflected on the shallow water, in the background a coastline is visible. The text says:

This ocean is my irreplaceable mother. Nature is irreplaceable. Home is irreplaceable. Even during the necessary production of electricity we won’t let nature be polluted. We work for clean energy production with full power. Clean nature shall stay clean! (cited in Honma, Citation2014, p. 42)

Figure 5. TEPCO advertisement showing Green Nuclear elements described above (from Honma, Citation2014, p. 42)

The advertisement shows that from a relatively early period, the pronuclear coalition marketed nuclear power as clean energy in Japan. The Green Nuclear frame became more prominent with the rise of the issue of global warming and climate change. Since 1990, the “Nuclear Almanac” published annually by JAIF underlines the utility of nuclear power against climate change (JAIF, Citation1990). In a plan drafted by METI (Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry, the successor of MITI) in 2010 envisaging Japan as an “established nuclear nation” (genshiryoku rikkoku) with 50% of energy supply delivered by nuclear power plants, the pronuclear coalition argued that nuclear power is an “ace” in the struggle against climate change (Sōgō Shigen Enerugī Chōsakai, Citation2010, p. 3).

Another important framing by the pronuclear alliance is Regional Development. This frame is also not present in Gamson and Modigliani’s survey. In this framing, building nuclear power plants is connected to the economic and cultural development of peripheral regions in Japan. These are the regions where nuclear power plants are located. Yoshimi cites a PR movie about Japanese nuclear power plants:

Futaba on the coast of Fukushima was in the past called “the Tibet of Fukushima” and was afflicted by severe depopulation. This has clearly changed. The population has grown, streets, sports facilities and schools were built. The municipal and the per-capita income increased. The nuclear power plant lives and develops together with the people of the region. (cited in Yoshimi, Citation2012, p. 267)

This frame could also be categorized as part of the Progress frame. However, we distinguished the two because at the core of Regional Development is an argument about creating equal development between periphery and center, or sharing benefits. This was part of the political debate in the early 1970s when Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei introduced subsidies for nuclear power plant locations. Tanaka argued:

The main reason why the construction of power plants doesn’t take off due to the antinuclear movement is that the construction of plants doesn’t bring any profit to the regions. (cited in Fukui Shinbunsha, Citation2012, p. 80)

The pronuclear alliance emphasizes the “tradition of coexistence” (kyōson) of local people with nuclear power plants:

Over 40 years ago [the village] Ōi took the decision to invite the nuclear power plant of Kansai Electric Power, even though the village was split in half over this question. The region has painstakingly developed through coexistence with the plant. (Fukui Shinbunsha, Citation2012, p. 120)

This argument can also be turned into a weapon against the antinuclear alliance by claiming that they ignore the tradition and livelihood of the people from peripheral regions. Such a reasoning can be found in comments by “pronuclear citizens” in the discussion forums sponsored by the AEC:

The (main) energy consuming areas should try harder to understand the pain of the energy producing areas. The inhabitants of consuming areas should become more aware of their energy and electricity consumption. The people from the metropolitan centers, who consume large amounts of energy should not easily say “pro” or “anti”. (AEC, Citation1999, point 4.3)

Keeping in mind that the antinuclear movement in Japan is stronger in metropolitan areas (compare for example, Machimura & Satō, Citation2016, p.9, Footnote5), this frame challenges the antinuclear coalition’s Soft Path frame (see section 4 below), which portrays nuclear power plants as having been forced on peripheral communities. shows an advertisement with elements of the Regional Development frame. lists the frames of the pronuclear coalition.

Figure 6. JAERO advertisement showing Regional Development elements. The characters on the electricity cable mean Kashiwazaki, an − at the time the sketch was published − contested location designated to host Japan’s largest nuclear power complex. The caption says: “Japan’s energy becomes the energy of the peripheral regions” (YS, Citation1975a)

Frames of the antinuclear coalition

From materials of the antinuclear coalition, we constructed five frames. Four of them can also be found in the Gamson and Modigliani survey.

One central argument by the antinuclear coalition is the attribution of Accountability to the “nuclear village”. Gamson (Citation1992) describes this frame as a justice argument and sees it as key factor for the mobilization of the antinuclear movement.

Scientists and progressives questioned the motives and integrity of politicians suspected to aim at building nuclear weapons as early as the start of the nuclear program, but since the 1970s an Accountability framing began to be directed against the civil use of nuclear power (Radkau, Citation2011). Gamson (Citation1992, p. 240) distinguishes between a softer and a harder version of Accountability. In one version, accidents and trouble in nuclear power production are criticized, but without assuming bad intentions. In the other version, actors of the pronuclear alliance are portrayed as malevolent and irresponsible. Recurring themes are the cover-up of accidents and dangers posed by radiation. In journals like Technology and Human speakers influenced by the student and new left movements criticized the nuclear industry. This can be seen from headlines like “the nuclear administration has begun to run amok” (Shimizu et al., Citation1974), “the true extent of contamination in Tsuruga and Fukushima”, “the strategy of the nuclear rulers”, and “nuclear power subsidies and information fascism” (Gijutsu to Ningen, Citation1976). Popular nuclear power critics from the antinuclear “new wave” of the 1980s like Hirose Takashi, and critical scientists like Takagi Jinzaburō both use the strong version of the Accountability framing. Hirose for example, talks about the alleged killing of people recruited by force to help contain the radioactive debris in Chernobyl (Hirose, as cited in Noguchi, Citation1988, p. 268) and labels a nuclear waste facility in Aomori prefecture as “the devil of the Shimo-Kita peninsula” (Suga, Citation2012). Takagi claims that the Japanese government handled nuclear accidents and disclosure of information similar to the Soviet government’s handling of the Chernobyl accident (Takagi, Citation1987). Iida Tetsunari, a former METI bureaucrat who became a prominent critic of nuclear power, coined the term “nuclear village” for the pronuclear coalition, because of its closed and collusive character:

By working in the field of nuclear power a kind of closed class consciousness and group coherence is developed. Forums like the Atomic Energy Commission and advisory councils are nothing but an excuse for the government to appear neutral. (Iida in Shūkan Asahi, Citation2002, p. 140)

Words like “cover-up” (inpei), “hiding” (kakushi), “manipulation” (kaizan), “nuclear money” (genpatsu manē), “sleaze” (yuchaku) and “waste of (tax) money” (mudazukai) indicate the strong version of the frame, when used in the context of nuclear power.

The weaker version is more often used by allies of the pronuclear coalition. One of their speakers for example, argues that instead of the terms Accountability and information disclosure (jōhō kōkai), the softer wording “responsibility to explain” (setsumei sekinin) should be used (Shimabayashi et al., Citation2008, p. 169). Actors with a more positive view of the pronuclear coalition use words like task (kadai) and lesson (kyōkun) when talking about accidents. shows bureucrats of the Nuclear Industry Safety Agency (NISA) that became a symbol of lack of Accountability during the Fukushima accident.

Figure 7. A picture of the Nuclear Industry Safety Agency (under the umbrella of METI) during a press conference in the midst of the Fukushima Dai'ichi accident. The agency was widely criticized for lack of Accountability during and after the accident (Utsukushii chikyū kankyō wo mamoru tame ni ikimono jakusha ni shien wo, Citation2012)

Runaway is a key frame used by the antinuclear coalition to question the legitimacy of energy production based on nuclear power. This framing emphasizes the risk of science and technology running out of control and turning against its creators. It assumes that nuclear power poses an unparalleled risk to mankind (and the environment) because of its power and the silent and invisible danger of radiation accompanying it. Wider cultural references for this framing in Europe include for example, Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” and Goethe’s “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” (Dahinden, Citation2002; Gamson & Modigliani, Citation1989, p. 20). It includes religious criticism of science but also more rationalistic arguments like the observation that accidents necessarily happen (Perrow, Citation1984). Gamson (Citation1992, p. 240) notes that in this framing the separation of civil use and nuclear weapons is neglected. The (essentially) same technology brings the same risk, which is a grave one.Footnote6 This frame was used by the antinuclear movement from the 1970s onward. It can, for instance, be found in the writings of Takagi Jinzaburō:

If an accident on the scale of Chernobyl happens, this is not a problem that could be dealt with by an apology. No, we will all be dead then and also the nuclear power managers will be dead. Nobody will complain and nobody will be held accountable. Maybe that is actually what scientists, politicians, managers and PR people think, who claim that nuclear power is safe. (Takagi, Citation1987, p. 21)

Hirose Takashi also uses this frame frequently, for example, when he speaks of “the day, when Hokuriku will disappear from the map” (Hirose, Citation1987). Perhaps the most influential formulation of this frame is Takagi’s critique of the inability of the nuclear industry to come up with a feasible plan of nuclear waste management. He coined the metaphor of an “apartment without a toilet” (toire naki manshon), where rubbish keeps piling up, to describe nuclear power (Takagi, Citation1987). The Runaway frame was also reformulated by seismologist Ishibashi Katsuhiko, who coined the term “nuclear earthquake catastrophe” (genpatsu shinsai), and, after the Kobe earthquake in 1995, warned that an earthquake could trigger a nuclear accident (Ishibashi, Citation1997). shows a picture emphasising Runaway elements.

Figure 8. A picture showing the alleged contamination of the Pacific Ocean after 2011 (http://radioactivetokyo.seesaa.net/upload/detail/image/ASRE7A4BEE6B5B7E6B48BE6B19AE69F93E59CB0E59BB3-thumbnail2.jpg.html)

Soft Path is another prominent frame used by the antinuclear alliance. In Gamson’s codebook the core arguments are that large-scale technological projects and waste of resources destroy the environment and are not sustainable. This is connected to the call to change one’s own lifestyle by saving resources and using renewable energy. shows a famous picture contaning Soft Path elements. Criticism of centralization as essentially undemocratic and the call for decentral energy solutions are also important (Gamson, Citation1992, p. 240). From Gamson’s codebook it becomes clear that he sees Soft Path in contrast to Runaway as focusing not on the unique danger from nuclear power, but its embeddedness in an idea of protecting a wider environment. A point that does not appear in Gamson’s codebook but in his quotations is the connection between society and nuclear power. The yes or no to nuclear power is interpreted as a fundamental choice influencing the development of society. In Japan, the antinuclear alliance took over the Soft Path frame from the 1970s onward. At an annual meeting of Gensuikin for example, a speaker argued:

The atom should be rejected, be it the peaceful use or the military use. Otherwise mankind has no future. Now is the time to conduct a radical value change and to reject nuclear civilization and build an antinuclear civilization opening a beautiful, thorough way of life for humans. (…) develop alternative energy sources (…) return the way of life to natural simplicity. Return from the conquest of nature to a life listening to nature. (Katō, Citation2012, p. 21)

Figure 9. A picture from the cover of the magazine published by the famous anime production company Studio Ghibli, showing Soft Path elements. In the front, celebrated director Miyazaki Hayao walks with a sign saying “no nukes”. The caption says “Studio Ghibli wants to make movies without nuclear power” (https://img.cinematoday.jp/a/byAHfsoKXEGd/_size_640x/_v_1314277457/main.jpg)

This “democracy argument” can also be discerned in Takagi’s writings:

First, because large-scale science (kyodai kagaku) produces discrimination (sabetsu), between citizens on the one hand and scientists on the other hand, equality has to be established. Second, large-scale scientific research may not be conducted top-down with hierarchical pressure. (AS, Citation1979)

In this framing, an often idealized countryside is contrasted with the invading nuclear power plant forced upon the local people by the metropolitan center. In an inversion of the Regional Development frame, nuclear power is portrayed as threatening the livelihood and harmony of marginalized land-dwellers:

Since I started engaging in activism against nuclear power I traveled the whole country, and, strangely, I came to see the most beautiful places of Japan. This is really strange, but they try to build nuclear power plants in the most beautiful places in Japan. (Hirose, Citation1987, p. 61)

[In communities where pronuclear and antinuclear groups organize] people say: “This house is pro, this house is anti”. The village community splits into two. “I won’t carry the portable shrine with these people”. In this way the regional culture is destroyed. (Anzai et al., Citation2012, p. 16)

Finally, references to life (seimei, inochi), motherhood and children figure prominently in Japanese versions of the Soft Path frame. Especially the motherhood references might be specific to the Japanese antinuclear movement (compare Lam’s (Citation1999) book on the green movement in Japan). Kansha Taeko, herself a mother-turned-antinuclear activist from Kyushu, uses Soft Path elements in an influential book published during the “new wave” of the 1980s:

The trees are radiant in verdant green. You hear the chirping of the birds. Everything looks so peaceful. I can hardly believe that in secrecy such a thing [the construction of nuclear power plants] is being done. We mothers wish nothing more than for our children to grow up healthily. We cannot forgive somebody threatening their life (seimei). (…) To protect the life of my unborn child I want to scream out loud “Away with nuclear power!” (Kansha, Citation2011, pp. 154–157)

The rejection of the cost-efficiency argument is another frame frequently used by the antinuclear movement. In the Not-Cost-Effective frame the antinuclear coalition argues that nuclear power is actually more expensive than other energy sources. shows a picture visualizing the financial burden from nuclear power. Critics of nuclear power underline that alternatives like renewables create green growth, and sticking to nuclear power is inhibiting future growth potentials. To limit the power of the utilities, the antinuclear alliance argues for a separation between energy production and transport (hassōden bunri) and a liberalization of the energy market (jiyūka). Takagi for example, claims that by building up nuclear power quickly on the basis of wrong projections of electricity demand, the utilities actually ended up with an over-supply of electricity:

Since 1982 nobody is talking about saving electricity anymore (…). We have an overproduction of electricity. Now the utilities even try to expand the sale of electric household appliances even though this is really the business of the electronics industry. (Takagi, Citation1987, p. 25)

Figure 10. A picture published in the newspaper Tokyo Shinbun showing Not-Cost-Effective elements. On the bottom, normal citizens carry trillions of yen for decommissioning the wrecked Fukushima Daiichi reactors (Tokyo Shinbun Web, Citation2016)

Iida Tetsunari argues to quickly introduce mechanisms to foster the growth of renewable energy:

Germany (…) has become the largest producer of wind power plants in the world (…). Most wind power plants were built after a feed-in-tariff system was introduced. In Denmark the production of wind power systems became an export industry and brought 20,000 jobs. (AS, Citation1999)

Finally, in some parts of the antinuclear movement the call for Resistance follows from the Accountability and Runaway frames. Before 2011, this frame was influential in groups affiliated with the new left. For instance, a poem published in a book by the antinuclear movement and written by elementary school students from the village Mutsu, a place where prominent protests against the maiden voyage of a nuclear powered ship took place, says:

From the boat, the fishermen are screaming: Resistance! The Mutsu Bay is ours! The nuclear ship is dangerous (…). Even if we die, we will fight the nuclear ship! We will defend the scallops! (Genbaku no Taiken wo Tsutaeru Kai, Citation1975, p. 40)

Resistance is the only antinuclear frame in our sample not relating to any frame in the Gamson and Modigliani study. After the Fukushima Daiichi accident, Resistance frames gained prominence not only in calls for action, but also in calls for democratizing energy policy . shows the frames of the antinuclear coalition.

Figure 11. The cover of the catalogue of a retail company calling for a referendum on nuclear power after the Fukushima Daiichi accident (It’s a New World (Blog), Citation2011)

Political frames and journalistic frames

All researchers cited above agree that the pronuclear coalition is far more powerful than the antinuclear one. In terms of media control, they are in charge of key press clubs like the Energy Press Club run by the utility federation, METI’s and other government institutions’ clubs as well those of TEPCO (cf. Uesugi & Ugaya, Citation2011). So we would expect this control to show up in the newspaper framing.

Sample and methods for the newspaper content analysis

To test this thesis, we compared the political frames in the debate with the media framing. We conducted a frame analysis of the newspapers Asahi Shinbun, Mainichi Shinbun, and Yomiuri Shinbun. These newspapers were chosen because they had the highest circulations during the period from 1973–2014. The currently largest newspaper, Yomiuri Shinbun, had a circulation of 5.51 million in 1970 and stood at slightly over 10 million in 2008, dropping to 8.09 million in 2019. The second largest, Asahi Shinbun, stood at 5.99 million in 1970 and 8.03 million in 2008, dropping to 5.59 million in 2019. The third largest, Mainichi Shinbun, stood at 4.66 million in 1970 and 3.8 million in 2008, dropping to 2.43 million in 2019 (Hirobay (Blog), Citation2009; J-Cast, Citation2019; both based on data published by the Japan Audit Bureau of Circulations).

To limit the article population we only focused on the genre of article series (rensai). In this way, we arrived at a total of 2,846 articles on the topic of nuclear power published in article series from 1973 to 2014. The focus on article series widens the scope from editorials (shasetsu), which have been the focus of most systematic analyses of framing of nuclear power in Japanese newspapers (Abe, Citation2015; H. Itō, Citation2004, Citation2005, Citation2009, 2012; Ōyama, Citation1999), but at the same time allows us to limit the sample to trace reporting over a long period of time. Article series range from mini-series of three articles to long-term series with up to several hundred articles (see appendix 3).Footnote7 They usually provide background reports, but mostly relate to recent events considered important by journalists and editors. Some article series are written by senior editors (henshū i’in) who have more freedom in their choice of topics than young reporters in press clubs. Others are written by teams of reporters, some of them stationed in press clubs, reporting incidents like nuclear accidents, the start-up of new power plants or facilities, or recent political or economic developments. Some article series also explicitly aim at producing straight news.

While the format is usually not (or not only) the report from an official source (happyō) generated in press clubs, the journalists contributing to article series retain press club membership, and at times, series are initiated through press clubs, for example, when journalists are invited for a tour of nuclear facilities (interview with Makino Kenji, Mainichi Shinbun). Series can also take the form of tie-ups initiated directly or indirectly (via the newspaper company management) by government agencies or companies, often coupled with symposia and advertisements (interview with Matsuzawa Hiroshi). While article series leave more room for independent agenda-setting than straight news, they display the whole range of reporting from business- or government-initiated reporting to independent journalistic agenda-setting. It is thus perhaps safe to say that – while less indicative of press club influence than straight news – article series provide us with a measure of reporting closer to everyday news than editorials, which are usually written by senior editors and published after being discussed with other senior journalists.

The search was conducted in the newspaper databases using multiple keywords like “nuclear power”, “reactor”, and names of various nuclear accidents and organizations involved in nuclear policy. We identified the full set of article series dealing with nuclear power over the period in question. Out of this sample we analyzed every third article for the period before 2011 and every fifth article after 2011 (only every tenth article of average length for the Asahi Shinbun due to the high number of overall articles in this newspaper after 2011).Footnote8 We analyzed 687 articles in total. For the period after 2011 we used not the number of articles but the average number of characters in an article to sample. This serves to adequately represent the differing length of articles during that period.Footnote9 We coded single passages and phrases with the frames explicated above. From the sum of these passages we coded up to three main frames for every article. We also kept the option to code articles as “without mainframe” when they did not fit any of the frames. In both the “political corpus” and the “newspaper corpus” we used open coding, adapting codes (and constructing new frames) when necessary (Gläser & Laudel, Citation2010).

Newspaper frame analysis

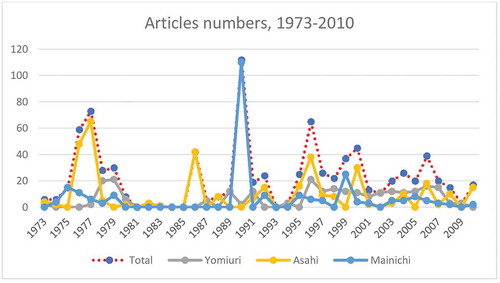

First, the number of articles varies by year. The numbers by newspapers show some contrasting trends but also similarity ().

In general, the Asahi published by far the most article series. The Yomiuri and the Mainichi published similar overall numbers, but with different distributions over time. Overall article numbers rose in the mid- to late 1970s, but to quite different degrees. Then, all newspapers’ article numbers dropped to nearly zero in the first half of the 1980s. From the mid- to late 1980s, article numbers rose again, and stayed at a relatively constant level afterwards. The Mainichi showed a peak in 1990 but before and afterwards coverage remained lower than that of the other two newspapers. From the mid-1990s through 2010 the article numbers of the Asahi and the Yomiuri stayed on a roughly similar level. shows the overall distribution of article numbers.

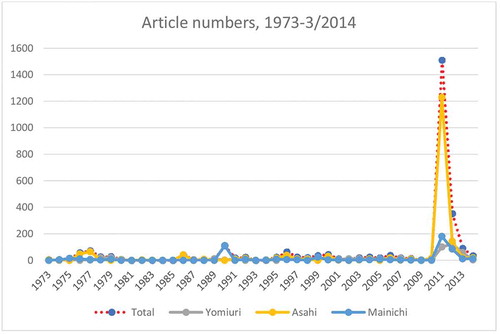

In the three years after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident the articles in all three newspapers increased rapidly. The numbers for the Asahi rose to 1,413 articles in three years compared to slightly fewer than 300 articles respectively for the other newspapers. Of course we would expect an increase of coverage after a major event such as the Fukushima Daiichi accident, but still from the perspective of agenda-setting, at least for some periods press clubs do not seem to be the most important factor influencing the quantity of article series. Besides these differences between time periods, the differences in quantity of coverage between the newspapers are notable. But what about the framing of nuclear power? From the newspaper analysis we constructed two genuine journalistic frames of nuclear power, which we did not find in the political corpus. We named one frame Hurdles because it depicts difficulties and obstacles that have to be overcome to develop nuclear technology in the future, without questioning the technology as such. It can be seen as a softer form of Progress framing and it often accompanies the softer version of Accountability, but is not very prominent on the whole. It appears most often in the Asahi from the 1990s onward. We also coded one additional neutral frame after 2011. We labelled it Victims because it focuses on the plight of victims of the nuclear accident (mainly evacuees), but it avoids any attribution of Accountability or general verdicts about nuclear power. This frame is most prominent in Yomiuri, but also appears in Asahi and Mainichi.

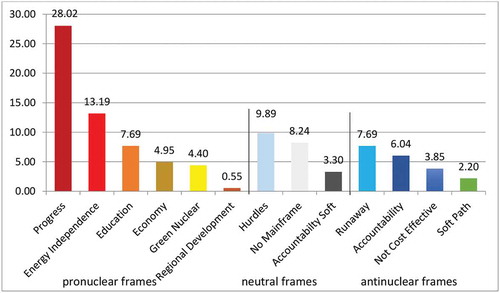

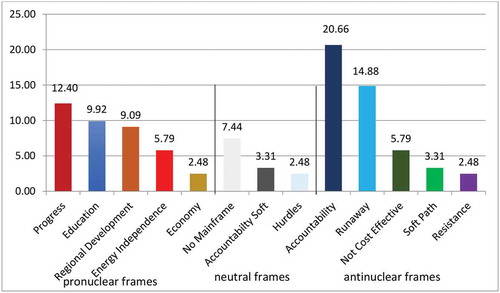

In the Asahi during the early phase of reporting until the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986, a positive framing of nuclear power remains dominant. Progress and Energy Independence figure most prominently. After 1986, the coverage becomes more balanced. Antinuclear frames like Runaway and Accountability gain prominence. On the whole, the balance in the Asahi rests slightly in favor of pronuclear framing. shows the framing in the Asahi before 2011.

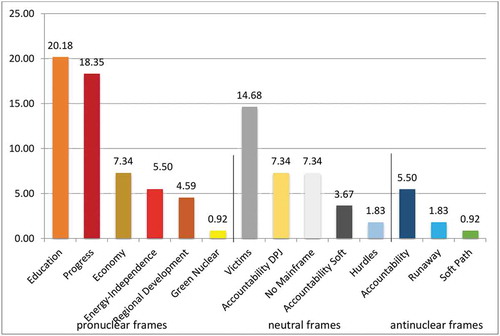

The Yomiuri is more clearly pronuclear. Here the frame balance is on the pronuclear side over the whole period, with one small exception in 1989. In contrast to the Asahi, framing of nuclear power plants becomes increasingly positive from the mid-1990s through 2010. In the Yomiuri, Progress, Nuclear Education, Energy Independence and Green Nuclear frames make up 81% of the main frames before 2011. show the framing of the Yomiuri before 2011.

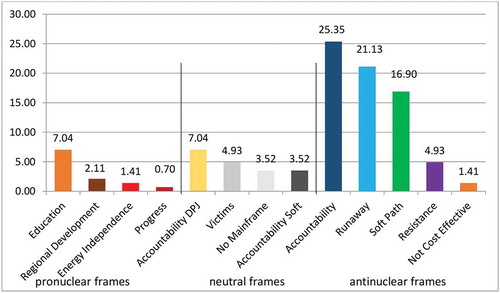

The Mainichi builds a contrast to the two other newspapers for the period before 2011. Here the framing of nuclear power is more often negative than positive. Accountability (21%) and Runaway (15%) frames appear most frequently. On the other hand, Progress (12%), Nuclear Education (10%), and Regional Development (9%) are also prominent. shows the framing of the Mainichi before 2011.

The impact of “Fukushima”

From the article numbers alone it becomes clear that the impact of the nuclear accident on media reporting was high. In the three years after the Fukushima Daiichi accident the newspapers published 57 times as many articles as in the three years before.

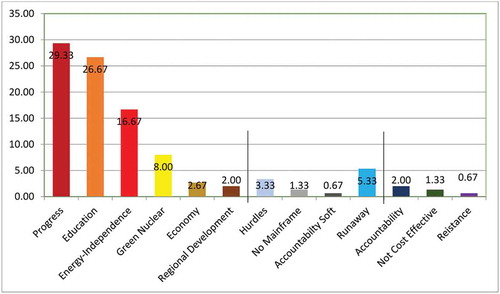

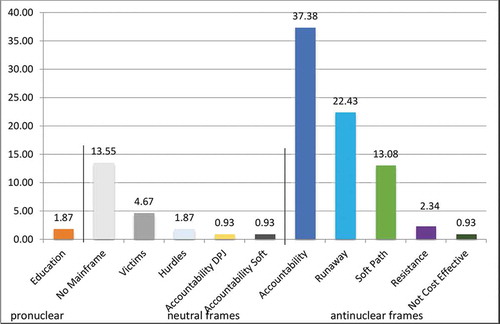

The most dramatic change can be observed in the Asahi. Here, positive framing disappears almost completely. Now Accountability, Runaway, and Soft Path together add up to 72% of all frames. shows the framing in the Asahi after 2011.

The Mainichi shows a similar trend, but it is less pronounced since the overall tendency was antinuclear well before 2011. Here, a margin of about 10% of frames remain pronuclear, but the rest resembles the framing in the Asahi. shows the framing in the Mainichi after 2011.

The Yomiuri is the only newspaper in the sample still framing nuclear power in a positive way after 2011. The most important change is that neutral frames rise from nearly zero to about one third. shows the framing in the Yomiuri after 2011Footnote10 Among the pronuclear frames, Green Nuclear (from eight to only one percent) declines. Nuclear Education becomes the most prominent frame (20%) followed by Progress (18%). Victims adds up to 15% of frames in the Yomiuri.

Conclusion

From analyzing the political and journalistic statements, we can see that the press club thesis hardly explains the media framing of nuclear power in article series. shows the overall tendency of framing before 2011.

While there is arguably some extent of “uniformity” and pro-elite bias before 2011 in the Asahi and especially the Yomiuri, for the sample from the Mainichi this does not hold. For the period after 2011, a polarization between the Yomiuri on the one pole and the Asahi and the Mainichi on the other pole can be observed. shows the overall tendency of framing after 2011.

These findings are in line with existing research based on the analysis of editorials (Abe, Citation2015; H. Itō, 2012). Because of the specific character of the sample, the differences do not disprove the claims concerning press clubs and uniformity, but they allow for a more nuanced evaluation especially for the period after 2011. Commentators concerned with the political economy of the media (Honma, Citation2014; Lill, Citation2017) note that press clubs are not the only mechanism for controlling the media. Historical studies of the press club system note that in the prewar phase, press clubs often served as a means for journalists to protect their freedom against the interests of powerful sources and newspaper managers (Kawasaki, Citation2009, pp. 1–2). Also, in the postwar era at times press clubs came into conflict with power holders. For example, in 1976 the conservative Ishihara Shintarō, then head of the Environmental Agency, clashed with the agency’s press club (Saitō, Citation2003). The newspapers of Okinawa also have very different standpoints on a variety of issues while still being represented in press clubs.Footnote11 We do not wish to deny the function of press clubs limiting independent reporting and constraining outsiders’ access to important sources. Most researchers and practitioners of journalism agree that the Japanese press club system in its current form is problematic. However, distinguishing between “bad” “insider mass media” and “good” “outsider media” is not always a useful perspective to explain the outcomes of media reporting. Obviously, our results allow us only to make sense of reporting on one limited issue, the nuclear power debate, so it would be useful to include other issues.

If the press clubs are not always the main factor influencing framing, what other factors are important? This question cannot be dealt with here exhaustively, but some possible factors can be identified. Media critics and some journalists have noted the extraordinary amount of advertising money for nuclear power PR channeled into the media before 2011 (e.g., Honma, Citation2014). How did this influence reporting? From the analysis of article series we can guess that there are pronounced differences between the effects of pressure through advertising money in different newspapers (see Honma, Citation2014). A distinction between “outsider” and “insider media” does not help to explain these differences. For the period after the Fukushima accident, especially from the start of the second Abe administration, observers note a decline in press freedom and increased government efforts to silence critical reporting (see Lill, Citation2017). This pressure, however, is primarily (though not exclusively) directed against influential “insider media”, not against outsiders of the press club system. A political struggle over nuclear power reporting of the Asahi Shinbun in 2014, for instance, was characterized by eventually successful right-wing attacks on the Asahi directed against the “special reporting unit” (tokubetsu hōdōbu) (Fackler, Citation2016), a section the newspaper had created to focus on investigative reporting. This happens to be the section responsible for a substantial part of the nuclear-critical article series analyzed here (see appendix).

Too much emphasis on the “insider-outsider” dichotomy can obfuscate the analysis rather than clarifying the problems at hand. Analysts should aim to develop models and indicators able to transcend this relatively simple dichotomy, comparing for example, how political and economic influences impact reporting in different organizational environments (for such an approach to classical media see, for instance, Benson, Citation2013). Given the recent decline of influence and political efficacy of “insider media” worldwide, analysts should aim to understand how the transformation of the power balance between newspapers, etc. and online media is impacting the framing of issues. The worldwide rise of online hate speech and political propaganda should caution us against assuming that “outsider media” necessarily report news in a more open, just and fair manner.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Humer Foundation for Scientific Talent, Forschungskredit of University of Zurich, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (GR16108) and the University of Zurich Alumni Research Talent Development Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tobias Weiss

Tobias Weiss is assistant professor (akademischer Mitarbeiter) at University of Heidelberg. He studied Japanese studies at University of Hamburg and earned a PhD at University of Zurich. He published a book on the reporting of nuclear power in Japanese journalism. His work also appeared in the journalsPoetics and Journal of Civil Society.

Notes

1 Compare Asano (Citation1993), Feldman (Citation1993, Citation2011), Hall (Citation1998), Krauss (Citation2000), and T. Yamamoto (Citation1989).

2 Uesugi and Ugaya's (Citation2011) criticism reached a large audience for instance.

3 For example Shibata (Citation2013).

4 The LDP came back to power in a coaliton in 1994 and eventually recaptured the position as long-term ruling party.

5 Kainuma (2012) echoes the pronuclear alliance when asserting that the antinuclear alliance illegitimately claims to represent the Japanese countryside. While this is not necessarily true, it is probably safe to say that the antinuclear movement is stronger in the metropolitan areas (with post-3.11 Fukushima as a possible exception; Machimura & Satō, Citation2016, p. 9). Hasegawa (Citation2004, p. 160) also notes that an antinuclear referendum in a more urbanized setting had a better chance of success than one in a very rural setting dependent on supporters from more distant towns and the prefectural capital.

6 Gamson and Modigliani (Citation1989) see fatalism as a key aspect of the Runaway frame. They underline that, because of this fatalism, Runaway does not encompass a rejection of nuclear power. However, we see the reason why they see fatalism as an element characteristic for this frame in the sample they use to construct it. They use caricatures, which is an art form based on exaggeration and sarcasm. To describe the Japanese framing of nuclear power it seems more useful to separate this aspect and redefine the frame based on the points mentioned above.

7 Articles concerning nuclear power from article series about wider topics, for example, energy, were included in the sample. In these cases, the number of articles in a series in the appendix can be one, but the articles are still part of an article series.

8 We made the change in the sample frequency because the number of articles increased rapidly from 2011, especially in the Asahi (see appendix). The sampling method is stratified random sampling.

9 In the Mainichi, only 22 articles of 291 after 2011 account for a third of the character count. If we had counted only the number of articles without taking into account their length, this would have led to longer articles being underrepresented when counting the frames. More relatively long feature series were published after 2011. Differences in article length do exist before 2011, but they are less pronounced.

10 We included Accountability attributions to the DPJ and Prime Minister Kan Naoto, which could also reasonably be included in the pronuclear section, in the neutral category. That the framing still remains strongly antinuclear in two newspapers should support our point about differences in reporting.

11 This does not imply that Okinawan and national, Tokyo-based newspapers operate under the same conditions, our point is only that both gather information through reporters in press clubs.

References

- Abe, Y. (2015). The nuclear power debate after Fukushima: A text-mining analysis of Japanese newspapers. Contemporary Japan, 27(2), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1515/cj-2015-0006

- AEC. (1999). 1.1. Genshiryoku no sentakushi (1.1. The choices in nuclear power). http://www.aec.go.jp/jicst/NC/iinkai/entaku/H11/teigen/ronten.html

- Anzai, I., Iida, T., Ōshima, K., & Hasegawa, U. (2012). Genpatsu zero. Watashitachi no sentaku (Zero nuclear – Our choice). Kamogawa Shuppan.

- Arima, A., & Sano, S. (1999). Interview: Mirai aru enerugī to shite wakaku yūshū na jinzai wo genshiryoku ni (Interview: Young and excellent human capital into nuclear power as the energy of the future). Enerugī Forum, 539, 82–85.

- Arima, T. (2008). Shōriki, genpatsu, CIA. Kimitsu bunsho de yomitoku Shōwa rimenshi (Shōriki, nuclear power, and the CIA. Telling the secret Shōwa-history with classified documents). Shinchōsha.

- AS (Asahi Shinbun). (1974, October 26). Jūgatsu 26nichi ha Genshiryoku no Hi (October 26 is the Day of Nuclear Power), 10.

- AS. (1977, August 27). Zadankai: Nihon no genshi no hi“ kyō seijinshiki, (Discussion: The nuclear flame becomes an adult today), 4.

- AS. (1979, April 24). Takagi Jinzaburō: Kagaku ha kawaru. (Takagi Jinzaburō: Science is changing), 25.

- AS. (1999, April 9). Shizen-enerugī: Hiromeru rippō isoge. (Natural energy: Hurry with the legislation for fostering it!), 4.

- Asano, K. (1993). Kyakkan hōdō (Objective reporting). Chikuma Shobō.

- Benson, R. (2013). Shaping immigration news. A French-American comparison. Cambridge University Press.

- Cassegard, C. (2018). The post-Fukushima anti-nuke protests and their impact on Japanese environmentalism. In D. Chiavacci & J. Obinger (Eds.), Social movements and political activism in contemporary Japan: Re-emerging from invisibility (pp. 137–155). Routledge.

- Dahinden, U. (2002). Biotechnology in Switzerland. Science Communication, 24 (2), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554702237844

- Fackler, M. (2016). Sinking a bold foray into watchdog journalism in Japan. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/the_feature/asahi_shimbun_japan_journalism.php

- Feldman, O. (1993). Politics and the news media in Japan. University of Michigan Press.

- Feldman, O. (2011). Reporting with wolves. In T. Inoguchi & P. Jain (Eds.), Japanese politics today (pp. 183–200). Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Freeman, L. A. (2000). Closing the shop: Information cartels and Japan's mass media. Princeton University Press.

- Fukui Shinbunsha. (2012). Genpatsu no yukue (The future of nuclear power) (Electronic ed.). Fukui Shinunsha.

- Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95 (1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213

- Genbaku no Taiken wo Tsutaeru Kai. (1975). Genbaku kara genpatsu made (From atomic bombs to nuclear power) (Vol. 1). Agune.

- Shimizu, Y., Hanada, Y., Taketani, M., Kamata, S., Gijutsu to Ningen editors &.Kume, S. (1974). Tokushū genshiryoku kaihatsu no saikentō (Special issue: reconsidering nuclear development). Gijutsu to Ningen, 15, 6–63.

- Gijutsu to Ningen(Ed.). (1976). Genshiryoku hatsuden no kikensei (The danger of nuclear power). Gijutsu to Ningen, 6–295.

- Gläser, J., & Laudel, G. (2010). Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente rekonstruierender Untersuchungen. VS Verlag.

- Hall, I. (1998). Cartels of the mind: Japan's intellectual closed shop. W.W. Norton.

- Hanada, T. (Ed.). (2012). Shinbun ha daishinsai wo tadashiku tsutaeta ka (Have the newspapers conveyed the earthquake catastrophe right?). Waseda Daigaku Shuppanbu.

- Hasegawa, K. (2004). Constructing civil society in Japan: Voices of environmental movements. Trans Pacific Press.

- Hayashi, K., & Kopper, G. (2014). Multi-layer research design for analyses of journalism and media systems in the global age: Test case Japan. Media, Culture & Society, 36 (8), 1134–1150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443714545001

- Hirobay (Blog). (2009). Sonbō no ki wo mukaeta shinbun (The newspapers have passed the turning point). http://www.geocities.jp/yamamrhr/ProIKE0911-120.html

- Hirose, T. (1987). Ima Nihon de okite iru koto (What is just happening in Japan). In Y. Amano (Ed.), Kōkoku Hihyō: Tokushū akarui ashita ha genpatsu kara (Advertisement Critique: Special issue: A bright future from nuclear power) (Vol. 95, pp. 56–69).Madora Shuppan.

- Honda, H. (2005). Datsugenshiryoku no undō to seiji. (The antiinuclear movement and politics). Hokkkaidō Daigaku Toshokankōkai.

- Honma, R. (2014). Genpatsu kōkoku to chihōshi (Nuclear advertisements and local newspapers). Aki Shobō.

- Hook, G. D. (1984). The nuclearization of language: Nuclear allergy as political metaphor. Journal of Peace Research, 21 (3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234338402100305

- Ishibashi, K. (1997). Genpatsu shinsai (Nuclear earthquake disaster). Kagaku, 67 (10), 720–724.

- It’s a New World (Blog). (2011). Terebi Asahi ga Catalog House ‘Tsūhan Seikatsu’ no CM hōei wo kyohi shita koto ni taisuru kokumin no hannō (The reaction of the people against TV Asahi rejecting the airing of Catalog House’s Tsūhan Seikatsu CM). http://toniha.blog59.fc2.com/blog-entry-95.html

- Itō, H. (2002). Kagaku hōdō no kinō to kōzō (Structure and function of science news). Poole Gakuin Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō, 42, 59–72.

- Itō, H. (2004). Genshiryoku kaihatsu riyō wo meguru media gidai, -jō (The media agenda regarding the development and use of nuclear energy (1)). Poole Gakuin Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō, 44, 63–76.

- Itō, H. (2005). Genshiryoku kaihatsu riyō wo meguru media gidai, -chū (The media agenda regarding the development and use of nuclear energy (2)). Poole Gakuin Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō, 45, 111–126.

- Itō, H. (2009). Genshiryoku kaihatsu riyō wo meguru media gidai, -ka (The media agenda regarding the development and use of nuclear energy (3)). Poole Gakuin Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō, 49, 101–116.

- Itō, H. (2012). Fukushima Daiichi genpatsu jiko igo no genshiryoku hōdō (Reporting on nuclear power after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident). Poole Gakuin Daigaku Kenkyū Kiyō, 52, 199–212.

- Itō, Mamoru (2012). Terebi ha genpatsu jiko wo dō tsutaeta ka (How has TV conveyed the nuclear accident?). Heibonsha.

- Itō,Masaaki (2012). Demo no media-ron (Demo-media theory). Chikuma Shobō.

- Iwase, T. (1998). Shinbun ga omoshirokunai riyū (Why the newspapers aren’t interesting). Kōdansha.

- JAERO. (1994). Genshiryoku bunka wo mezashite (Envisaging a nuclear culture). Nihon Genshiryoku Bunka Shinkō Zaidan.

- JAIF. (1990). Genshiryoku nenkan (Nuclear almanac). Nihon Genshiryoku Sangyō Kaigi.

- Japan Productivity Center (JPC). (1996). Genshiryoku genjō no kadai to sono shōrai wo kangaeru (Rethinking contemporary challenges of nuclear power and their future). Shakai Keizai Seisansei Honbu.

- J-Cast. (2019). Mainichi Shinbun ga mō sugu Nikkei ni oikosareru. Chōmaiyomi no shūen (The Mainichi is soon going to be overtaken by the Nikkei. The end of Chōmaiyomi). https://www.j-cast.com/2019/09/07366659.html?p=all

- Kabashima, I., & Broadbent, J. (1986). Referent pluralism: Mass media and politics in Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 12(2), 329–361. doi:10.2307/132391

- Kabashima, I., & Steel, G. (2010). Changing politics in Japan. Cornell University Press.

- Kabashima, I., Takeshita, T., & Serikawa, Y. (2010). Media to seiji (Media and politics). Yūhikaku.

- Kamide, Y. (2016). Hōdō no jikokisei (The self-censorship of media). Liberta Shuppan.

- Kansha, T. (2011). Mada ma ni au no nara (If I’m still on time) (Tablet ed.). Jiyūsha.

- Katō, T. (2012). Nihon Marx-shugi ha naze ‘genshiryoku’ ni akogareta no ka (Why was Japanese Marxism attracted to ‘nuclear power’?). http://members.jcom.home.ne.jp/rikato/120526atom.pdf

- Kawasaki, Y. (2009). Senzenkisha club ni taisuru sūryōteki bunseki. Nihon Shinbun Nenkan wo mochiite (Quantitative analysis of press clubs during the prewar period on the casis of Newspaper Yearbooks). Hyōron Shakai Kagaku, 87, 71–94.

- Kingston, J. (2012). Japan’s Nuclear Village. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 10 (37).https://apjjf.org/2012/10/37/Jeff-Kingston/3822/article.html

- Krauss, E. (2000). Broadcasting politics in Japan: NHK and television news. Cornell University Press.

- Lam, P. E. (1999). Green politics in Japan. Routledge.

- Lill, F. (2017). Im Käfig oder nur zu zahm? Wie frei sind Japans Medien unter Abe? In S. Heinrich & G. Vogt (Eds.), Japan in Der Ära Abe: Eine Politikwissenschaftliche Analyse (pp. 163–183). Iudicium.

- Machimura, T., & Satō, K. (ed.). (2016). Datsugenpatsu wo mezasu shimin katsudō (The citizen movement against nuclear power). Shinyōsha.

- Martin, S., & Steel, G. (Ed.). (2008). Democratic reform in Japan. Lynne Rienner.

- Matthes, J. (2007). Framing-Effekte. Fischer.

- Noguchi, K. (1988). Detarame darake no Hirose Takashi ‘Kiken na hanashi’ (“A dangerous thing” from Hirose Takashi is full of nonsense). Bungei Shunjū, 66 (9), 262–283.

- Ōyama, N. (1999). Genshiryoku hōdō ni miru media frame no hensen (Changing media frames on nuclear power). Tōkaidaigaku Kiyō, 72, 41–60.

- Packard, G. R. (1966). Protest in Tokyo: The security treaty crisis of 1960. Greenwood.

- Perrow, C. (1984). Normal accidents. Basic Books.

- Pharr, S. (1996). Media as a trickster. In S. Pharr & E. Krauss (Eds.), Media and politics in Japan (pp. 19–44). University of Hawaii Press.

- Pharr, S., & Krauss, E. (Eds.). (1996). Media and politics in Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

- Radkau, J. (2011). Die Ära der Ökologie. Beck.

- REF (Radiation Education Forum). (2010). Teikan (statute). Hōshasen Kyōiku Forum.

- Reich, M. (1984). Crisis and routine: Pollution reporting by the Japanese press. In G. DeVos (Ed.), Institutions for change in Japanese society (pp. 148–165). Institute of East Asian Studies.

- Saitō, T. (2003). Kūso na shōkōtei: Ishihara Shintarō to iu mondai. Iwanami Shoten.

- Scalise, P. J. (2012). Hard choices: Japan’s post-Fukushima energy policy in the twenty-first century. In J. Kingston (Ed.), Natural disaster and nuclear crisis in Japan (pp. 140–155). Routledge.

- Segawa, S. (2011). Genpatsu hōdō ha daihon’ei happyō datta ka. (Were the news on the nuclear accident announcements from the imperial headquarters?). Journalism (Tokyo), 255, 28–39.

- Shibata, T. (2013). Kagaku hōdō (Science reporting). Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppankai.

- Shimabayashi, Y., Hayashizaki, N., & Torii, H. (2008). Kagaku gijutsu no senmonka ni setsumei-sekinin ga shōjiru kyokumen no tankyū: Kagaku gijutsu no tokushusei to shakaiteki sekinin wo shiten to shite (Searching for instances when science and technology specialists have a responsibility to explain: Focusing on the characteristics of science and technology and social responsibility). Kenkyū Gijutsu Keikaku, 23(2), 163–175.

- Shūkan Asahi. (2002, September 27). Tōdai kōgakubu shusshinsha ga shuryū „genshiryokumura“ no hijōshiki. (The stupidity of the nuclear village, where Tokyo University Engineers are the majority), 140.

- Sōgō Shigen Enerugī Chōsakai. (2010). Genshriyoku rikkoku keikaku (Plan for an established nuclear power nation). METI.

- Suga, H. (2012). Hangenpatsu no shisōshi (A history of ideas of the antinuclear movement). Chikuma Shobō.

- Takagi, J. (1987). Genpatsu kōkoku no tadashii yomikata (The right way to read nuclear power advertisements). In Y. Amano (Ed.), Kōkoku Hihyō: Tokushū akarui ashita ha genpatsu kara (Advertisement Critique: Special issue: A bright future from nuclear power) (Vol. 95, pp. 23–45). Madora Shuppan.

- Takekawa, S. (2007). Forging nationalism from pacifism and internationalism: A study of Asahi and Yomiuri’s New Year’s Day editorials, 1953–2005. Social Science Japan Journal, 10 (1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jym030

- Tanaka, Y. (2004). Genshiryoku to Communication I (Nuclear energy and communication I). Gakushuin Review of Law and Politics, 40 (1), 1–66.

- Tokyo Shinbun Web. (2016). No title. http://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/economics/list/201612/CK2016121702000152.html

- Uesugi, T., & Ugaya, H. (2011). Media saigai, genpatsu-hen (Media catastrophes, nuclear edition). Gentōsha.

- Utsukushii chikyū kankyō wo mamoru tame ni ikimono jakusha ni shien wo. (2012). No title. https://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/shgmmr/GALLERY/show_image.html?id=63586257&no=0)

- Weiss, T. (2019). Auf der Jagd nach der Sonne. Das journalistische Feld und die Atomkraft in Japan. Nomos.

- Wolferen, K. V. (1989). The enigma of Japanese power: People and politics in a stateless nation. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Yamada, K. (2013). 3.11 to media (3.11 and the media). Transview.

- Yamamoto, S. (1976). Nihonjin to genshiryoku (The Japanese and nuclear power). World of Press.

- Yamamoto, T. (1989). The press clubs of Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 15 (2), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/132360

- Yoshimi, S. (2012). Yume no genshiryoku: Atoms for dreams. Chikuma Shinsho.

- YS (Yomiuri Shinbun). (1975a, July 27). Nihon no naka no Kashiwazaki (Kashiwazaki in the middle of Japan), 13.

- YS. (1975b, June 28). Hidezō-san ni kiku Hidezō (Hidezō asking Mr. Hidezō), 14.

- YS. (1975c, April 27). Hantai haichō (Listening to the ‘anti’), 10.

- YS. (1975d, March 29). Jimoto no hito ga kakukaku shikajika (The local people think like this), 16.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Codebook

The following questions were used to code the frames. Gamson and Modigliani’s codes are taken from Gamson (Citation1992, pp. 234–243). In the beginning of every frame section there is a condensed statement of the core assumptions.

Progress: “Technological progress steadily improves our lives. Nuclear power is essentially safe, though minor problems might have to be resolved. Radiation exists everywhere, it is a problem of managing the dose. Nuclear accidents are normal and should be seen as a chance to improve safety measures.”

Gamson:

There is no practical alternative to nuclear power; we need it.

Nuclear energy can provide a lot of power, we can’t do without it.

Other sources of energy all have serious problems.

Officials will protect the public from harm, are concerned with protecting the public. The situation is under control.

The TMI or Chernobyl accident was not that serious; media coverage exaggerated the risk.*

Nuclear power isn’t so different from other forms of energy.

Nuclear energy hazards are just another of life’s many hazards; not that different.

Underdeveloped nations can especially benefit from peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

Nuclear energy can (will) liberate us. Although it can be used to destroy (with weapons), it can also give us the abundant energy we need for the good life.

Nuclear power is necessary for economic growth, maintaining our way of life, standard of living; the choice is between nuclear energy and going back to a more primitive time of technological backwardness. We owe it to future generations to develop nuclear power.

The problems of nuclear power are solvable ones; they will be solved by effort and research; the question isn’t whether to rely on nuclear power but at how fast a rate; nuclear power can (will) become more cost-effective.

TMI shows that the system works; a serious accident didn’t happen because the backup systems functioned to prevent it.

Nuclear power opponents are “coercive utopians” or a “new class” trying to impose their values and vision on others; nuclear protesters are protesters in search of a cause.*

Nuclear power opponents are hysterical, afraid of change, opposed to technological progress, naive and panicky, neo-Luddites, pastoralists.*

“Too cheap to meter” quote.

Safety record of nuclear power plants is excellent.

Chernobyl is contrasted with TMI to make the point that radiation was contained at TMI; Chernobyl couldn’t happen here.

U.S. plants are different from and safer than Soviet plants.

Lessons for a safer future can be learned from TMI and Chernobyl; new procedures will be instituted that will reduce future risks.

* I included these codes under the “Education” frame.

Adapted/complemented:

Progress

Technology, quality of life

Is nuclear power being associated with advances of the quality of life?

Are new and amazing technological developments and/or opportunities (related to nuclear power technology) being presented?

Do records like unprecedented reactor sizes, kilowatt per hour production of electricity or general electricity output appear?

Is nuclear power being depicted in the context of new discoveries and frontiers like the exploration of space or the cultivation of the seas?

Is the importance of scientific progress (related to nuclear power) being emphasized?

Are nuclear power plants being related (in a positive way) to symbols of power like professional sports?

Is the fast breeding reactor depicted as a way towards unlimited energy supply?

Is the high level of Japanese nuclear power technology being underlined?

Are there references to the Astro Boy comic (Atomu) when talking about nuclear power?

Are there references to the nuclear flame (genshi no hi ga tomoru) or “the third flame” (daisan no hi) being lightened?

Is the progress/development of nuclear power being portrayed in historical perspective (in a positive way)?

Is electricity connected to progress/“a good life”?

Are positive impacts of nuclear power on fish breeding presented?

Are prospects of nuclear technology (for example, the fast breeder) for becoming more advanced and safer/more competitive being portrayed?

Are the prospects or achievements of technological progress being underlined?

Japan’s nuclear power is at the peak of development.

Is the use of technologies like mixed nuclear fuel portrayed in terms of progress?

Peaceful use

Is the peaceful character of nuclear electricity production being underlined?

Is Japan’s right or obligation to work on the peaceful use of nuclear power (as an atomic bomb victim) being underlined?

Are differences between the bomb and electricity generation being underlined?

Japan chose the peaceful use (heiwa riyō) of nuclear power.