Abstract

The present study suggests that the theoretical framework of evolutionary psychology, in particular theories and models relating to social status and pride, can be used to further our understanding of educational motivation. Our assumption was that the desire for social recognition and high status is a universal human phenomenon. Based on this, we suggested that differences in educational motivation among high school students would be related to differences in the extent to which one sees academic achievements as a viable path to social status and source of pride. The present study examined this topic using a cross-sectional design in a sample of high school students. In general, the results provided support for the hypothesis that status and pride are reliably related to educational motivation in high school students, and that the theoretical framework employed could be used to understand differences in educational motivation related to both gender and level of parental education.

Introduction

According to the OECD report “Education at a glance” (2019), educational attainment comes with several advantages. The unemployment rate for adults with tertiary education in OECD countries is 6.6%, compared to 16.8% for adults with below upper secondary education. Adults with a master’s, doctoral or equivalent degree earn twice as much as those with upper secondary education, and adults with a bachelors or equivalent degree earn 22% more (OECD, Citation2019). In addition, countries benefit from higher education through higher tax revenues and reduced public expenditure on social welfare programs. Finally, higher educational attainment results in better social outcomes in that adults with tertiary education report higher life satisfaction, better health and are less likely than those with lower education to report activity limitation due to health problems (OECD, Citation2019).

Given the above, predicting and influencing educational motivation and achievement is an important area of research. Consequently, there exists a substantial number of studies investigating predictors of educational achievement from a wide array of perspectives, from individual differences related to motivation, personality traits, and intellectual abilities (e.g., O’Connor & Paunonen, Citation2007) to social factors such as social class, gender, and ethnicity (e.g., Harris, Citation2008; OECD, Citation2019; Rampino & Taylor, Citation2013). A considerable amount of research has also investigated what learning environments, pedagogical methods, as well as teacher skills and attributes that are conducive to learning and educational achievements (e.g., Hattie, Citation2009). The present study seeks to contribute to this literature and to further our understanding of differences in educational motivation by employing a theoretical model originating in emotion research and evolutionary psychology, which focuses on the attainment of social status and the emotion of pride, to predict individual differences in educational motivation.

The strive to achieve social status is regarded as a universal human phenomenon (Cheng et al., Citation2013; Henrich & Gil-White, Citation2001; Maner & Case, Citation2016) and high status positions tend to be associated with increased influences over evolutionarily important factors such as resource allocation, group decisions, and conflicts (Henrich & Gil-White, Citation2001). Consequently, from an evolutionary perspective, high status is related to higher relative reproductive success (Cowlishaw & Dunbar, Citation1991; Hill, Citation1984), which suggests that natural selection has been operating on social and intrapersonal strategies as well as psychological modalities and mechanisms related to the attainment and negotiation of social status.

When analyzing status strategies in humans, Henrich and Gil-White (Citation2001) have suggested that there exist two broad categories of strategies that can be traced to our evolutionary history. The first is called dominance, and refers to strategies to attain social status that ultimately rely on the induction of fear in others through threatening behavior, violence, coercion, and/or the control of resources central to the well-being of others (Henrich & Gil-White, Citation2001). The second strategy is called prestige and refers to strategies where status is achieved by the fact that the individual is regarded as knowledgeable and as possessing important skills by other group members (Henrich & Gil-White, Citation2001). Both classes of strategies have ties to our evolutionary history and can be adaptive depending on the social context and characteristics of the individual.

As with other fitness relevant aspects of human social life, it has been suggested that we have evolved psychological traits aimed at providing affective, motivational, and behavioral adaptions related to the two strategies described above. In this context, the emotion of pride has been suggested to serve the purpose of motivating status-seeking efforts, signaling status achievements and self-perceived status to others and providing psychological reinforcers to behaviors leading to status attainment (Tracy et al., Citation2010). Pride is a self-conscious emotion that is linked to the regulation and maintenance of self-esteem and social status, and previous research has identified two distinct forms of pride (Tracy & Robins, Citation2007): Authentic pride is based on specific accomplishments and emerges when the individual make attributions that are internal, unstable, and controllable (e.g., “I’m proud of what I did,” Tracy & Robins, Citation2007). In contrast, hubristic pride is loosely tied to specific events and is the result of attributions that are internal, stable and uncontrollable (e.g., “I’m proud of who I am”; Tracy & Robins, Citation2007). Authentic pride is a pro-social, achievement-oriented form of pride associated with the development of successful social relations and genuine feelings of self-worth, whereas hubristic pride is associated with narcissism, aggression, hostility interpersonal problems, and relationship conflict (Tracy & Robins, Citation2007). In their “status-pride model,” Cheng et al. (2010) suggest that the authentic pride is associated with the status strategy prestige, whereas the pride facet hubristic pride is associated with dominance. Support for this model has been found in several studies and in different contexts. Carver et al. (2010) found that authentic pride correlated with measures of self-control, whereas hubristic pride was related to measures of impulsivity and aggression, and concluded that the differential pattern of correlations fitted with a model in which authentic pride is tied to adaptive achievement and goal engagement, whereas hubristic pride is tied to extrinsic values of public recognition and social dominance. Cheng et al. (Citation2010) found a strong correlation between authentic pride and prestige as well as between hubristic pride and dominance, both using self-report measures and rating by peers. In addition, and as predicted by the model, Cheng et al. (Citation2010) found a significant positive correlation between students’ GPA and their self-reported levels of prestige, whereas no correlation was found with dominance. To our knowledge, however, no studies have examined the relationship between educational motivation and the status-pride model. There are however strong reasons to assume that such relationships exist and a few previous studies indirectly suggest that this might be the case: In general, attitudes towards education and how we feel about school have been found to be related to educational motivation as well as educational performance (Artino et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, Kiefer and Ryan (Citation2008) found a negative correlation between educational motivation and performance and the ambition to control peers by inducing fear and obedience. Ames and Archer (1992), conversely, found that students who make an effort in school based on a motivation to appear more competent than others, see education as a means to become socially successful, and, in line with this, Elliot et al. (Citation1999) found that prestige-oriented motives and goals correlated positively with the extent to which students made an effort in school.

Hence, based on both previous research as well as the theory behind the status-pride model, it is reasonable to expect that the status-pride model might be useful in predicting educational motivation. By educational motivation in this context, we refer to an internal state that energize and direct goal-oriented behavior related to educational performance and educational attainment (Kleinginna & Kleinginna, Citation1981). Furthermore, we believe there are strong reasons to assume that the status-pride model can be related also to other aspects known to be associated to educational motivation such as gender, parental education, and socialization regarding the value and benefit of education.

Parental education is known to be a strong predictor of both educational motivation and educational attainment (OECD, Citation2019). In relation to the status-pride model, this ought to be reflected in positive linear trends between parental education and both authentic pride and prestige, indicating that students with highly educated parents to a larger extent believe that others value their achievements and performances and that they take pride in what they accomplish. Furthermore, based on research by, for example, Mickelson (Citation1990) and Harris (Citation2008), we know that in social groups characterized by lower educational attainment, attitudes which conceptualize education as something that is generally of value, only not for them, are more prevalent. These attitudes are based on the perception that for them, there exist social barriers and obstacles that diminish and reduce the positive outcomes of receiving an education and performing well in school (Harris, Citation2008). Given this and in relation to the status-pride model, a reasonable prediction is that students who do not believe that education is a viable path for them to achieve a better life, to a larger extent should seek out other ways of achieving social status and experience other forms of pride than pride in their own accomplishments.

Finally, with regard to gender, in western societies it has been a clear trend during recent decades that girls and young women do better than boys and young men with regard to school performance (OECD, Citation2015) and that they to a higher degree move on to higher education (OECD, Citation2015). Furthermore, it has been reliably found that young women report higher educational aspirations and more positive attitudes towards education than young men (OECD, Citation2015; Rampino & Taylor, Citation2013). In Sweden, where the present study was conducted, girls currently outperform boys in school both when measured in terms of grades and in performances on international standardized tests such as PISA and TIMMS (The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2019). From the perspective of the status-pride model, these trends might reflect a difference in the degree to which young women and young men take pride in educational achievements, where young women’s prestige related pride might be more related to their educational aspirations and achievements, whereas other areas might be more important for young men in establishing a sense of pride and accomplishment.

Purpose and hypotheses

Based on the background described above, the purpose of the present study was to test the validity of the status-pride model suggested by Cheng et al. (Citation2010) in predicting attitudes toward education in students’ attending upper secondary school (16- to 18-year old). Given previous findings on differences in educational attitudes and achievement related to gender and socioeconomic group, we also wanted to test hypotheses concerning how the status-pride model and its relationship to educational motivation varies as a function of gender, parental education and the degree to which one views education as a viable path to a better life.

More specifically, the study was designed to test the following hypotheses:

The status-pride model will be valid in predicting positive attitudes towards education in that there will be a positive correlation between prestige and authentic pride, and the measure of educational motivation. The correlation between dominance and hubristic pride and educational motivation, is assumed to be zero or negative.

Given the fact that parental education is positively related to educational achievement (OECD, Citation2019) we expect that there will be a significant positive linear trend between parental education and both authentic pride and prestige.

Participants who perceive, and who are told by their parents, that education is not a reliable way for them to receive a good life should resort more to dominance strategies in achieving social status and less to prestige-based strategies. Hence, we expect that there will be positive correlations between Dominance and Hubristic pride and perceptions of barriers despite schooling and parents’ message of barriers despite schooling (Harris, Citation2008, see method section below), as well as negative correlations between Prestige and Authentic pride and the same variables.

As referred to above, research indicates that young women prioritize education more than young men (OECD, Citation2015; Rampino & Taylor, Citation2013). From the perspective of the status-pride model, this might reflect a situation where young women emphasize education in reaching social status and take more pride in educational achievements to a higher degree than young men. Based on this, we hypothesize that there will be a significant difference between young men and young women in educational motivation, and that the positive association between prestige and authentic pride and educational motivation would be significantly stronger in women than in men.

Method

Participants and procedure

The participants in the present study (N = 837) were volunteers recruited among high-school students attending different programs at 17 different schools in Sweden. Thirteen of the contacted schools declined participation. Booklets containing an information letter and all the measures were administered to the students by the school administration at the schools agreeing to participate in the study, either in paper form or electronically via e-mail. There were no exclusionary criteria to participate in the study. The sample consisted of 63% girls (N = 527) and 37% boys (N = 309) and the average age was 17.1 years (SD = .89). 74% (N = 610) of the respondents had parents that were both born in Sweden, whereas 14% (N = 116) had at least one parent born in the rest of Europe or North America. 11% (N = 93) had at least one parent born outside Europe or North America.

Measures

Dominance-prestige self-report scale

Dominance and prestige strategies were assessed by the Dominance-prestige self-report scale (DPSS)-scale, which has been validated in previous studies (Cheng et al., Citation2010). In the DPSS, the respondents are asked to indicate “the extent to which each statement accurately describes you,” on a 7-point likert scale (1: not at all; 7: very much). The DPSS-scale include eight items assessing prestige (e.g., “My unique talents and abilities are recognized by others” and “Others seek my advice on a variety of matters”) and eight items assessing dominance (e.g., “I enjoy having control over others” and “I often try to get my own way regardless of what others may want”). The Swedish version of the scale showed adequate internal consistency (Chronbach’s alphas: Prestige: .71; Dominance: .70)

Authentic and hubristic pride scale

Authentic and hubristic pride were assessed with the authentic and hubristic pride scale (AHPS). AHPS is a 14-item adjective checklist designed to measure authentic pride (7 items) and hubristic pride (7 items). The AHPS has shown satisfactory psychometric properties in previous research. To complete AHPS participants were instructed to use a five-point Likert scale (1: not at all; 5: always) to assess the extent to which they generally feel as described in each scale item. The Swedish version of the scale used in this study exhibited adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas: Authentic pride: .84; Hubristic pride: .77).

Barriers despite schooling

To assess attitudes related to whether education is seen as a viable path to a better job, two items previously used in research (Harris, Citation2008) were used. The first assessed the participants’ own perception by asking the participants to rate the degree to which they agreed with the statement “People like me aren’t treated fairly at work no matter how much education they have” on a scale from 1 to 7. The other item measured the extent to which the participants experienced that their parents had given them the impression that there exists barriers to social advancement despite education. This was done by asking them to rate the degree to which they agreed with the statement “My parents say people like us are not always paid or promoted according to our education” on a 7-point scale. In the present sample, the two items measuring barriers despite schooling showed a strong bivariate correlation (r = .57, p < .001).

Educational motivation

To assess individual differences in educational motivation we used the aggregated scores on items from three different measures: Affective Attitudes Towards School, Perceived Value of Schooling and Likelihood of Future Education. Affective Attitudes Towards School is a four item scale measuring feelings towards homework, different subjects and studying in general whereas Perceived Value of Schooling consists of five items intending to capture participants perceptions of the extent to which schooling can improve their live chances. The scales have been used in previous research on educational motivation and has shown adequate psychometric properties (Harris, Citation2008). On both scales, the participants rate on a seven point scale the degree to which the items are true for them. Likelihood of Future Education was a single item measure designed for the present study and consisted of the question “do you intend to attend post-secondary education” and was rated on a scale ranging from “No, definitely not” (1) to “Yes, definitely” (7). The aggregated measure of Educational motivation showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .83).

Results

Relationship between the variables in the status-pride model

As a first step in the data analysis, the intercorrelations between the different variables in the status-pride model (Cheng et al., Citation2010) were examined. This was done to assure that the measures employed to measure the constructs in the present study had similar relationships to each other as what has been found in previous research. Results are presented in .

Table 1 Bivariate intercorrelations between the different variables of the status-pride model.

As can be seen in , the intercorrelations between the variables in the present study were well in line with what is to be expected based on the status-pride model (Cheng et al., Citation2010). In addition, the correlations between the variables in the present study is close to what has been found in previous research (Cheng et al., Citation2010). The only correlation which is a bit surprising given the theory behind the model is the positive correlation between authentic pride and hubristic pride. A very similar correlation between these variables (r = .19) was found, however, by Cheng et al. (Citation2010) in their study, which they suggested could be explained by a possible shared variance in self perceived agency.

Hypothesis 1: Status-pride model and educational motivation

Regarding the relationship between the components of the status-pride model and educational motivation, we hypothesized (hypothesis 1) that there would be a positive correlation between prestige and authentic pride and the measure of educational motivation and a negative correlation between dominance and hubristic pride and the same variable. To test the hypothesis bivariate correlations were calculated between the variables of interest. Results are presented in .

Table 2 Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s) between the components of the status-pride model and educational motivation.

Hence, as hypothesized the analysis revealed positive correlations between the status strategy “Prestige” and educational motivation. In accordance with our hypotheses, we also found a significant positive correlation between authentic pride and educational motivation. With regard to the status strategy Dominance our hypotheses was supported in that we found negative correlations between Dominance and educational motivation and a significant negative correlation between Hubristic pride and the same variable.

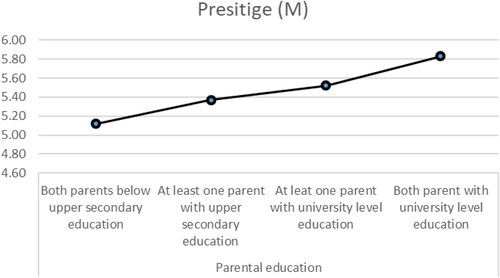

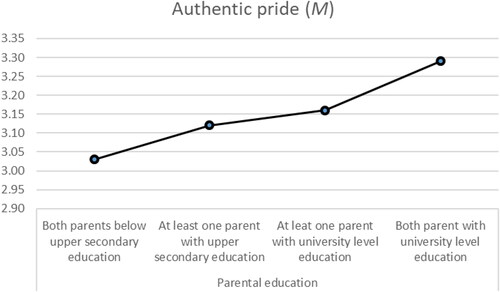

Hypothesis 2: Pride, authentic pride, and parental education

The second hypothesis stated that there would be positive linear trends for both prestige and authentic pride with increasing level of parental education. To examine the hypothesis two analyses of variance were performed using polynomial contrasts to test for linearity. displays the relationship between parental education and prestige and the relationship between parental education and authentic pride.

In accordance with our expectations, the analysis for Prestige revealed a significant linear trend related to increased parental education (Contrast estimate = .51, p < .001). The same, and also in support of our hypothesis, was true for authentic pride (Contrast estimate = .15, p = .01).

Hypothesis 3: Relationship between perceived barriers despite schooling and the status-pride model

In the third hypothesis, we assumed that there would be a positive correlation between the included measures on barriers despite schooling (parents message of barriers and own perceptions of barriers) and Dominance and Hubristic pride, whereas negative correlations were expected with Prestige and Authentic Pride. The hypothesis was tested by calculating bivariate correlations, and the results are presented in .

Table 3 Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s) between the components of the status-pride model and perceived barriers in life despite schooling (based on own experience and message from parents).

Hence, our hypothesis was supported for all calculated correlations except for the correlation between Authentic Pride and Parents’ message on barriers despite schooling, which was nonsignificant rather than negative.

Hypothesis 4: Gender and the status-pride model’s relationship to educational motivation

The final hypothesis stated that women would score higher than educational motivation than men and that there would a stronger positive correlation between both prestige and authentic pride and the measure of educational motivation for women than for men. As expected, an independent samples t-test showed that women scored higher than med on educational motivation (Mwomen = 45.1, SD = 8.60; Mmen = 42.3, SD = 9.03; t (816) = 4.59, p < .001).

The bivariate correlations are presented in .

Table 4 Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s) for women and men between prestige, authentic pride, and educational motivation.

To compare the differences between the correlation coefficients for women and men, Fisher’s r-to-z transformations were performed. The results are presented in .

Table 5 Results of Fisher’s r-to-z test of the correlation coefficients for women and men between the components of the status-pride model and educational motivation.

As can be seen in , our hypothesis was supported in that the correlations between prestige/authentic pride and educational motivation were significantly stronger for women than for men.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to test the validity of the status-pride model suggested by Cheng et al. (Citation2010) in predicting attitudes towards education in students’ attending upper secondary school (16- to 18-year old). The rationale for this was an assumption that the strive for social status and recognition is a universal human phenomenon and that among young people – who spent a lot of their time in school and whose main occupation is related to education and studying – individual differences in whether or not one sees academic achievements as a viable path to social status and source of pride, is likely to be an important predictor of educational motivation.

In general, our analyses showed that the status-pride model can predict differences in educational motivation. The two status strategies (dominance and prestige) and their corresponding facets of pride (hubristic and authentic) correlated as expected with the measure of educational motivation. Indeed, when compared to a variable such as parental education, which is known to be an important predictor of educational attainment and aspirations, and which in our sample correlated .15 (Person’s r) with educational motivation, the correlation between the status strategy “Prestige” and educational motivation was significantly stronger (r = .27; z = 2.53, p = .006).

Furthermore, prestige and authentic pride showed significant linear positive trends with parental education, indicating that the higher educated the parents are, the more students tend to report high levels of status strategies related to social recognition of their achievements and competencies and pride related to success in important areas of life. This finding can also be related to the finding that students who reported higher levels of barriers to social advancement despite education (self-perceived and parent mediated), also tended to report more status strategies related to social dominance and less to achievements. This can be interpreted as reflecting a process related to the reproduction of group-based social differences in education and socioeconomic status, where children of parents with high education see school and educational achievements as a natural arena for performance and social reinforcements, whereas students of less privileged backgrounds – who from previous research are known to perceive more social barriers despite schooling (Harris, Citation2008) – to a larger extent turn to other arenas and strategies to achieve social status and a sense of self-worth.

Finally, the performed study also provided support for the hypothesis that the gender difference in educational aspirations (e.g., OECD, Citation2015; Rampino & Taylor, Citation2013) would be reflected in a gender difference in the degree to which prestige and authentic pride is related to educational motivation. In the present study, women scored higher than men on educational motivation, and the correlation was stronger with both prestige and authentic pride and educational motivation among young women than young men. This can be interpreted as implying that young men seek and receive prestige-based status through other forms of achievements than school performances to a higher degree than young women, which might in turn be related to young men having lower educational aspirations and ambitions. This gender difference in educational motivation might in turn be one of the factors explaining the gender difference in educational achievements (OECD, Citation2019; The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2019).

When interpreting the results of the performed study, there are some limitations that should be kept in mind. The main limitation is the fact that the study has a cross sectional design which make it impossible to draw conclusions about possible causal relationships between the studied variables. This of course poses limitations to the theoretical conclusions that can be drawn from the study, but perhaps less so when one considers the fact that it seems unrealistic to expect a simple linear causal relationship between the status-pride components and educational motivation – no matter what direction one assumes that the causality has. Most likely these characteristics has developed in a reciprocal relationship across the individuals’ lifespan and in interaction with their social context. In future studies, it would therefore be interesting to study the longitudinal relationships between the components of the status pride model and educational motivation and see how these variables and their covariation change over time. Another limitation is the fact that all employed measures are based on self-reports which makes the results susceptible to mono method biases and effects of social desirability. In future research on the status-pride model, it would be interesting to also include peer ratings of social status and on what this status is based (prestige vs. dominance) as well as grades or other external measures such as teacher ratings of educational achievements.

Despite these limitations we believe that the present study expands the research on the status-pride model suggested by Cheng et al. (Citation2010) in significant ways in that it tests it in a new context (educational motivation in secondary education) and in relation to important social factors known to be related to educational aspirations (e.g., gender and parental education). In addition, and most importantly, the study provides a new perspective to the understanding of differences in educational motivation by applying a model based in evolutionary emotion research to the study of educational psychology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1992). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students' learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 260–267.

- Artino, A. R., Jr., Holmboe, E. S., & Durning, S. J. (2012). Control‐value theory: Using achievement emotions to improve understanding of motivation, learning, and performance in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 64. Medical Teacher, 34(3), e148–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.651515

- Carver, C. S., Sinclair, S., & Johnson, S. L. (2010). Authentic and hubristic pride: Differential relations to aspects of goal regulation, affect, and self-control. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(6), 698–703. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.09.004

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030398

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., & Henrich, J. (2010). Pride, personality, and the evolutionary foundations of human social status. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 334–347. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.004

- Cowlishaw, G., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1991). Dominance rank and mating success in male primates. Animal Behaviour, 41(6), 1045–1056. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80642-6

- Elliot, A. J., McGregor, H. A., & Gable, S. (1999). Achievement goals, study strategies, and exam performance: A mediational analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 549–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.549

- Harris, A. L. (2008). Optimism in the face of despair: Black white differences in beliefs about school as a means for upward social mobility. Social Science Quarterly, 89(3), 608–630. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00551.x

- Hattie, J. A., (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior: Official Journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, 22(3), 165–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00071-4

- Hill, J. (1984). Prestige and reproductive success in man. Ethology and Sociobiology, 5(2), 77–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(84)90011-6

- Kiefer, S. M., & Ryan, A. M. (2008). Striving for social dominance over peers: The implications for academic adjustment during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 417–428. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.417

- Kleinginna, P., Jr., & Kleinginna, A. (1981). A categorized list of motivation definitions, with suggestions for a consensual definition. Motivation and Emotion, 5(3), 263–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993889

- Maner, J. K., & Case, C. R. (2016). Dominance and prestige: Dual strategies for navigating social hierarchies. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 129–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2016.02.001

- Mickelson, R. A. (1990). The Attitude-Achievement Paradox Among Black Adolescents. Sociology of Education, 63(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2112896

- O’Connor, M. C., & Paunonen, S. V. (2007). Big Five personality predictors of post-secondary academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 971–990. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.017

- OECD. (2015). The ABC of gender equality in education: Aptitude, behaviour, confidence, PISA. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264229945-en

- OECD. (2019). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en

- Rampino, T., & Taylor, M. (2013). Gender differences in educational aspirations and attitudes. ISER Working Paper Series.

- The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. (2019). Könsskillnader i skolresultat. https://skr.se/tjanster/merfranskr/rapporterochskrifter/publikationer/konsskillnaderiskolresultat.28930.html

- Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007). The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 506–525. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.506

- Tracy, J. L., Shariff, A. F., & Cheng, J. T. (2010). A naturalist's view of pride. Emotion Review, 2(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073909354627