Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a highly impairing condition with varying clinical presentations. Psychological treatments for ADHD are often similar, irrespective of predominant symptomatology. However, because inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are associated with different challenges in daily life more presentation-specific treatments are warranted. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the feasibility and explore the preliminary effects of a novel group-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) protocol for ADHD predominantly inattentive presentation (ADHD-I), with the aim to reduce symptoms of inattention and associated problems. Materials and Methods. Using an open trial design, 39 adult patients with ADHD-I were included. Participants underwent 14 sessions of the new CBT for ADHD-I (CADDI) protocol, which includes skills training in organizing and initiating activity and coping with procrastination and passivity. In addition, mindfulness meditation is practiced throughout treatment. Results. The CADDI protocol proved feasible in terms of session completion and treatment acceptability. However, home assignment completion was moderate and attrition was high. Inattentive symptoms, assessed by clinicians and self-report, were reduced of a medium effect size, (Cohen’s d = 0.65 and d = 0.55, respectively) and symptoms of depression of a small effect size (d = 0.48). An increase of a large effect size was observed for mindfulness meditation (d = 0.91). No effects were seen in functional impairment, nor in quality of life. Conclusions. The CADDI protocol is a potentially valuable new psychological treatment for adults with ADHD-I, although treatment effects need to be further evaluated and participant retention secured in randomized controlled trials.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition defined by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, presenting before the age of 12 and causing functional impairment in social, academic or occupational functioning according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). ADHD has a prevalence of about 2–4% in the adult population worldwide (Fayyad et al., 2017). The condition is associated with high life-time psychiatric comorbidity, role impairment, and low quality of life (Fayyad et al., Citation2017; Kooij et al., Citation2019). DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) specifies three presentations of ADHD: predominantly inattentive (ADHD-I), predominantly hyperactive/impulsive, and combined presentation.

Symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are in different ways associated with adverse outcomes and consequences in daily life. Inattention has been found to be more associated with functional impairment than hyperactivity/impulsivity (Vitola et al., Citation2017). Distractibility, absent-mindedness, forgetfulness and procrastination, along with difficulties in organization and activation, are typical expressions of attention problems (Kooij et al., 2019; Posner et al., Citation2020). Several studies have found impairment in school and work performance, relationship difficulties, and quality of life to be more closely associated with inattentive than hyperactivity symptoms in adults (Das et al., Citation2012; Fredriksen et al., Citation2014; O’Neill & Rudenstine, Citation2019; Vitola et al., Citation2017). Finally, inattention is specifically associated with high general stress and negative affect (Combs et al., Citation2015; Knouse et al., Citation2008; Salla et al., Citation2019), as well as impaired capacity to set and achieve desired goals (Gudjonsson et al., Citation2010). Therefore, it may be expected that treatment of inattention should have effects on comorbid symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety, in as far as these symptoms are secondary to ADHD. In ADHD-I passivity and procrastination are impairing symptoms and therefore, adults with ADHD-I may need a treatment focusing mainly on inattention and associated problems regarding activation.

International guidelines recommend multimodal treatment for ADHD, including psychoeducation, pharmacotherapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (Kooij et al., 2019). Oftentimes, CBT focuses on compensatory strategies to cope with the symptoms and consequences of ADHD. Strategies can include functional analysis, organizational skills, and mindfulness practice. A meta-analysis of CBT for ADHD in adults including 12 open studies and 18 controlled studies showed reductions of ADHD symptoms of medium-to-large within group effect sizes and small-to-medium between-group effect sizes (Knouse et al., Citation2017). Another meta-analysis including only randomized controlled trials (RCT) showed similar results, but described data as heterogeneous and of low quality (Lopez et al., Citation2018). There are a few open studies and RCTs with passive control favoring CBT on measures of depression and anxiety (Lopez et al., Citation2018).

Functional impairment and quality of life are outcomes of particular interest in the treatment of ADHD. However, few studies have reported on these measures (Knouse et al., Citation2017). In an open feasibility study, measures of impairment and quality of life showed small, but significant changes (Morgensterns et al., Citation2016). Lopez and colleagues (2018) reported no difference between CBT and controls on measures of quality of life in randomized controlled studies. As previous studies (Fredriksen et al., Citation2014; Vitola et al., Citation2017) have found that symptoms of inattention are more strongly related to functional impairments compared to symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity, this outcome is of certain interest in the treatment of ADHD-I.

Regarding measures of feasibility, dropout rate, attendance rate, and participant evaluations have been used in previous studies (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2011; Morgensterns et al., Citation2016; Philipsen et al., Citation2007). These studies show low attrition and good acceptability. Feasibility can also be described in terms of adherence to treatment procedures, for example, home assignments; but these adherence rates are rarely reported in studies of ADHD.

Both individual CBT (Safren et al., Citation2005, Citation2010) and metacognitive therapy in a group format (Solanto et al., Citation2010) have proved beneficial in reducing ADHD symptoms compared to active control groups. A much used group treatment is the Hesslinger protocol (Hesslinger et al., Citation2002; Philipsen et al., Citation2007), which is an adaptation of dialectical behavior therapy, using primarily functional analysis and mindfulness meditation. This protocol has proved feasible in clinical settings (Morgensterns et al., Citation2016; Philipsen et al., Citation2007) and effective compared to active control groups (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2011). However, the protocol was not proved superior to individual counseling in a large multicenter RCT (Philipsen et al., Citation2015).

Mindfulness is a type of meditation with the aim to enhance present-moment awareness and is commonly used to reduce stress (Gotink et al., Citation2016). Mindfulness meditation is also used to improve attention and emotion regulation. There is growing support of mindfulness meditation having an effect on ADHD symptoms through increased regulation of attention, affect and behavior (Hepark et al., Citation2019; Janssen et al., Citation2019). There are studies showing promising results for mindfulness as an important component in interventions for ADHD, but evidence still remains weak due to the lack of larger randomized studies (Poissant et al., Citation2019). At present, the Hesslinger protocol (Hesslinger et al., Citation2002) is the only CBT protocol that includes mindfulness meditation as a treatment component of ADHD. Further, mindfulness is an appreciated component in this protocol (Philipsen et al., Citation2007). A challenge for psychological treatments is the transfer of learned strategies into everyday life through home assignments. Individual support might need to be added to group treatment to increase adherence to the treatment, as recognized in previous studies (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2011; Morgensterns et al., Citation2016).

In conclusion, symptoms of inattention in adults are associated with large impairments in daily life (Vitola et al., Citation2017). The CBT protocols by Safren (Citation2005) and Solanto and colleagues (2010) focus on strategies for organization of activity but do not include mindfulness. The protocol developed by Hesslinger and colleagues (2002) includes mindfulness practice and functional analysis of behavior but focus on organization of activity and procrastination to a lesser extent. To our knowledge, no psychological treatment protocol for adults has yet been designed specifically for ADHD-I focusing on inattention and its associated difficulties with passivity and procrastination in conjunction with mindfulness.

The present study introduces a novel treatment protocol called CBT for ADHD-I (CADDI), which includes skills training regarding organization and activation, as well as mindfulness meditation as a means of enhancing attention and self-regulation. The development of the CADDI protocol was motivated by a clinical concern regarding how to deal with symptoms of passivity and procrastination in patients with ADHD-I using available CBT protocols. The CADDI protocol therefore includes skills training of organizing, initiating, and completing activity to cope with avoidance and procrastination. Finally, the protocol includes individual support and follow-up on home assignments outside of sessions in order to increase adherence to home assignments and adapt the treatment to the individual needs of participants.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the feasibility of the CADDI protocol, including participant retention, adherence, and treatment acceptability, in preparation for a future RCT designed to assess the effectiveness of the protocol (Eldridge et al., Citation2016). A secondary aim was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the effects of the CADDI protocol in routine psychiatric care on outcomes of psychiatric symptoms, functional impairment, and quality of life.

Materials and methods

Design and procedure

The present feasibility study had an open trial design and was conducted at four centers of a psychiatric outpatient clinic in Stockholm, Sweden. Treatment groups were led by eight therapists who were psychologists or psychotherapists experienced in CBT for ADHD. Participants provided written informed consent and were assessed pre and post treatment. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (2016/255-31/5, 2016/1733) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02889354).

Participants

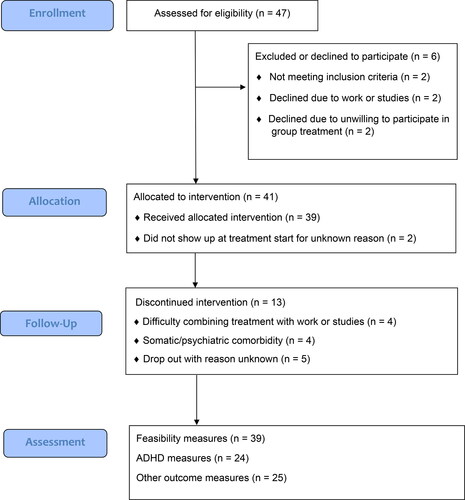

Participants were recruited among patients with a previously established diagnosis of ADHD-I according to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Diagnostic assessment was conducted according to clinical guidelines and included multi-professional assessment of ADHD, anamnestic information, and assessment of intellectual ability. In addition to ADHD-I the inclusion criteria were: ≥ 18 years of age, full scale IQ ≥ 80, and unmedicated or on stable medication since two months. Exclusion criteria were: autism spectrum disorder, substance use disorder, previous difficulties in compliance with pharmacological or other treatment, and major social and/or psychiatric problems that could interfere with participation in treatment (e.g., homelessness, psychotic symptoms). Participants were assessed for comorbidity using the modules focusing on affective and anxiety disorders of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., Citation1998). A total of 47 individuals were assessed for eligibility and 39 were included in the study as participants. See flow diagram of participants presented in , including reasons for exclusion. Of the participants, 21 (53.9%) were females and the mean age was 31.3 years.; see for participant characteristics.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants.

Treatment

The CADDI protocol was developed by EES and KS, inspired by the work on psychological treatment of ADHD by Hesslinger and colleagues (Hesslinger et al., Citation2002, Hesslinger et al., Citation2004; Philipsen et al., Citation2007) and Safren and colleagues (2005; Safren et al., Citation2010), as well as by the work on behavioral activation by Addis and Martell (Citation2004). The CADDI protocol includes themes regarding organization of activity, daily routines, coping with procrastination and negative affect, and uses functional analysis to identify reinforcement contingencies. Mindfulness meditation is practiced during the sessions continuously throughout the treatment and as home assignments based on audio-recordings of meditation exercises. The aim of mindfulness practice is to enhance attention and awareness of thoughts, feelings, and impulses to facilitate behavior change. All major themes in the protocol are rehearsed over two sessions and followed up continuously. Some sessions are dedicated solely to repetition to enhance acquisition of new habits and routines. To enhance learning and the transfer of new strategies to everyday life participants conduct home assignments and are encouraged to share the content of the week’s session with a significant other. An overview of the CADDI protocol is presented in .

Table 2 The content of the CADDI protocol.

The CADDI protocol was delivered in a group format consisting of 14 weekly 2-hour sessions including a break and was designed for groups of a maximum of 10 participants; in the current study, treatment group size ranged from five to 10 participants (M = 7.8, SD = 2.2). After each session, participants were given the option of a short (≤ 30 min) individual consultation of treatment progress. Following the first five sessions, a group leader called the participants by telephone once a week to support adherence to home assignments and to offer extra support if needed.

Measures

Feasibility

Feasibility of the CADDI protocol was explored using several measures, including the number of sessions attended, completed home assignments, the use of mindfulness meditation outside of treatment sessions, the use of telephone support between sessions, and dropout from treatment. In addition, treatment acceptability was measured by the patient evaluation form of the Hesslinger protocol (Hesslinger et al., Citation2004), which includes the following three items: 1) “The intervention has focused on my difficulties”, 2) “I can handle my symptoms better after the intervention”, and 3) “I am no longer as impaired by my symptoms”. Items were scored on a scale ranging from 1 (Definitely not true) to 5 (Definitely true). The form was modified for use in the current study, exchanging the intermediate score of 3 from I don’t know to True to some extent. Participants rated the separate treatment components using a scale with the following response alternatives: 0 (Not helpful), 1 (A little helpful), 2 (Quite helpful), and 3 (Very helpful). Moreover, the whole intervention was graded by participants using the following response alternatives: 0 (Failed), 1 (Passed), 2 (Passed with distinction), and 3 (Passed with special distinction). At session 5, treatment acceptability was also assessed in terms of participants’ perception of treatment credibility and expectancy for improvement using the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ; Devilly & Borkovec, Citation2000). Finally, adverse events were assessed using the Negative Effects of Psychological Treatments Questionnaire (NEQ; Rozental et al., Citation2016).

Treatment effects

Inattention symptoms was assessed as a clinician-administered interview conducted by the group leaders using the Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scales (BADDS; Brown, Citation1996). BADDS measure the frequency of inattention symptoms and associated problem behaviors. The BADDS includes 40 items and has shown high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability (Brown, Citation1996; Kooij et al., Citation2008). Further, the inattention subscale of the Current ADHD Symptoms Scale (CSS; Barkley & Murphy, Citation1998) was used as a self-report measure. The CSS items closely parallel the DSM symptom criteria for ADHD and are scored on a 4-point scale. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Citation2001), anxiety using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment 7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Citation2006) and stress using the Perceived Stress Scale-14 (PSS-14; Cohen et al., Citation1983). Mindful awareness was assessed using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, Citation2003). Quality of life was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., Citation1985) and functional impairment using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; Sheehan, Citation1983).

Statistical analysis

Proportions, means and standard deviations were calculated for feasibility measures. Paired samples t-tests were used to explore treatment effects. Within-group effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d.

Results

On average, the 39 participants attended 10.0 (71.4%) of 14 sessions, while those 26 participants who completed treatment attended 12.8 (91.4%) of sessions. Home assignments followed 13 of the 14 sessions and were completed on average 6.1 (46.9%) of sessions for all participants, and 7.9 (60.8%) of sessions for participants completing treatment. Mindfulness meditation between sessions was practiced on average 6.3 (52.5%) of 12 weeks for all participants and 8.6 (71.7%) weeks for those completing treatment. Individual telephone support on home assignments during the first five weeks of the intervention was used on average 2.6 (52.0%) of the weeks for all participants and 3.4 (68.0%) of the weeks for those completing treatment. Thirteen (33.3%) participants dropped out of treatment. Attrition varied greatly between psychiatric centers: one center had high attrition (n = 5; 71.4%), while the other three centers had moderate attrition or no dropouts. When counting out the center with highest attrition, the dropout rate for the remaining centers was 25.0%. Of note is that four (30.8%) of the participants dropped out due to difficulties of combining treatment with work or studies.

Concerning treatment acceptability, 83.4% of participants rated a 4 or a 5 (out of 5) regarding to what extent the treatment focused on their difficulties (M = 4.1, SD = 0.7). Nearly half of the participants (45.9%) rated a 4 or 5 regarding to what extent they perceived that they could manage their symptoms better after treatment (M = 3.4, SD = 1.0), the same scores were rated by a third (33.3%) of participants regarding if they were less impaired by their symptoms after treatment (M = 3.3, SD = 1.2). With regard to treatment credibility using the CEQ, 69.7% of participants rated a 7 or above (M = 7.1, SD = 1.4) on the 9-point scale on how logical the treatment seemed. Regarding how successful the treatment would be in reducing their symptoms, 27.3% of participants scored a 7 or above (M = 5.5, SD = 1.6) and 69.7% scored a 5 (Somewhat successful) or above. Of participants, 63.6%, rated a 7 or above (M = 6.9, SD = 1.8) on whether they would recommend the treatment to a friend. Regarding treatment expectancy using the CEQ, a majority (54.5%) of the participants expected an improvement in symptoms of 50% or more at the end of treatment (27.3% of participants scored expecting 70% or more) and 66.7% felt that the treatment would at least “somewhat” (i.e., a score of 5) help them to reduce their symptoms (18.2% scoring a 7 or above). Similarly, 51.5% of the participants felt that at the end of treatment, 50% improvement in symptoms would occur (18.2% of participants scoring 70% and or above).

Ratings of the eight components of the CADDI protocol showed that 75.0% of participants considered mindfulness meditation and coping with stress as quite helpful or very helpful, making these the highest rated components. Planning and organization skills, initiating and finishing tasks, and information about ADHD were considered to be quite helpful or very helpful by about 71% of participants. The lowest rated component was lifestyle, which was considered quite helpful or very helpful by 33.3% of participants. When treatment as a whole was rated on a scale from 0 to 3, 87.0% of participants evaluated the intervention as a 2 (Passed with distinction) or a 3 (Passed with special distinction). None of the participants rated the intervention as a 0 (Failed). Finally, with regard to the occurrence of negative effects, 16.0% of participants reported increased stress due to treatment, while no participant experienced negative effects on sleep, worry, mood, or self-esteem. No participant regarded the treatment as poor, useless, or lacking positive outcomes.

For results of a preliminary evaluation of treatment effects, see . Both clinician-assessed and self-rated measures of inattention showed a statistically significant decrease of a medium effect size from pre to post treatment, whereas a decrease of a small effect size was found for depressive symptoms. An increase of a large effect size was observed for mindful awareness. No statistically significant effects were found on measures of general anxiety, stress, functional impairment, or quality of life.

Table 3 Means, standard deviations, paired t-tests and Cohen’s d effect sizes for treatment outcome measures.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the feasibility and explore the preliminary effects of the CADDI protocol in adults with ADHD-I in a psychiatric outpatient setting. The CADDI protocol is the first CBT protocol designed for ADHD-I and proved feasible in terms of session completion and treatment acceptability. However, home assignment completion was moderate and attrition was a concern. An evaluation of treatment effects showed symptom reduction on measures of inattention and depression and an increase on mindful awareness, with small-to-large effect sizes.

The completion rate of 71.4% of the sessions (91.4% among completers) is reasonable in a group treatment context and comparable to the attendance rate reported in another feasibility study (Morgensterns et al., Citation2016). However, home assignments, including mindfulness meditation, were completed half of the sessions (60.8% among completers). Telephone support was offered as unstructured follow-up on home assignments the first five weeks of treatment and aimed to assist participants in completion of home assignments. This individual follow-up between group sessions was underused by some participants while others received it as intended. To improve the protocol, it could be considered to make telephone support a mandatory part throughout the whole treatment, thereby likely increasing adherence to treatment procedures.

The dropout rate varied between centers and was particularly high at one of the four centers. Probably, the high attrition at this center could be explained by organizational difficulties and change of staff shortly before treatment start, resulting in lower therapist adherence to study procedures and thus an increased risk of participant dropout. Of note is that 30.8% of the participants dropping out reported difficulty of combining treatment with work or studies, pointing to the particular demands of treatment in a group format, including session length and a fixed schedule for sessions. The treatment length of 14 group sessions is considered important to ensure implementation of new strategies but may contribute to increased dropout. To ensure engagement and decrease attrition, it should be considered important for future studies to conduct a more careful assessment of the participants’ capacity to engage in treatment. More individual adjustments and support through weekly follow-up on home assignments could also increase engagement in treatment and prevent dropout.

Treatment acceptability was high as a majority of participants considered the CADDI protocol to correspond adequately to their needs and being helpful with regard to lowering ADHD symptom levels. The treatment components were appreciated by participants, particularly mindfulness meditation, planning and organization, and coping with stress. This suggests that the protocol succeeded in being tailored to the perceived needs of patients with ADHD-I. Organizing daily life is a significant problem area for many patients with ADHD-I that may be insufficiently covered in the protocol by Hesslinger and colleagues (2010), an observation also made by Morgensterns and colleagues (2016). Participants considered the themes about lifestyle factors, self-esteem and relationship skills the least helpful, which may be a consideration in future improvements of the protocol. These aspects were included to address common difficulties in individuals with ADHD-I, but they are not core symptoms of ADHD-I. Ratings on measures of treatment credibility and expectancy for improvement showed that a majority of participants considered the treatment to be logical and that they would recommend it to others. About half of the participants expected an improvement in symptoms of 50% or more at the end of treatment, which is reasonable considering the persistent nature of ADHD. A possible contributing factor of the feasibility of the CADDI protocol may be its repetitive structure, designed to meet the particular needs of patients with ADHD-I.

A preliminary evaluation of treatment effects showed medium effect size reductions for both clinician-assessed and self-rated inattention symptoms, providing preliminary support of the CADDI protocol as a potentially beneficial treatment for ADHD-I. These results are in line with other studies of CBT for ADHD which have found medium-to-large within-group effect sizes (Knouse et al., Citation2017; Lopez et al., Citation2018; Morgensterns et al., Citation2016). In addition, a reduction in symptoms of depression of a small effect size was observed, which is consistent with some previous studies (Lopez et al., Citation2018; Morgensterns et al., Citation2016; Philipsen et al., Citation2007), but not with others (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2011; Philipsen et al., 2015). However, no effects were found on anxiety and stress, which is in line with previous studies (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2011; Morgensterns et al., Citation2016; Solanto et al., Citation2010). One explanation is that the treatment itself can be stressful as work with behavior change is strenuous. Activation as opposed to passivity may in the short perspective be demanding, while hopefully decrease stress in the long run. Similar to the study by Morgensterns and colleagues (2016), a minority of the participants in the present study reported increased stress levels during treatment. Another explanation is that the theme on stress in the protocol may have been insufficiently covered relative to the needs in the group. The strong connection between inattention and stress (Combs et al., Citation2015; Salla et al., Citation2019) along with the result of the present study indicate that coping with stress is of high relevance in treatments for ADHD-I and the CADDI protocol may be further developed in this regard. However, a significant increase of a large effect size was observed on mindful awareness. Findings from several previous studies indicate that mindfulness training is effective for decreasing symptoms of inattention (Hepark et al., Citation2019; Janssen et al., Citation2019). It is therefore of great interest to investigate mindfulness meditation as a possible mediator of treatment outcome in future RCTs.

Measures of functional impairment and quality of life did not detect any significant changes, as was also observed by Hirvikoski and colleagues (2011). It may be expected that psychological treatment for any psychiatric disorder should increase quality of life and reduce functional impairment, but it may be that benefits of treatment need some time to be realized in daily living. Studies designed to assess effectiveness and including follow-up on measures of functional impairment and quality of life are highly needed.

Strengths of the present study included the use of several measures of feasibility and that it was conducted within routine clinical care at four locations, which provide support for external validity. Moreover, the sample characteristics regarding education and employment are comparable to reports in previous intervention studies of ADHD conducted in Sweden (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2015, Hirvikoski et al., Citation2017), providing support of representativity. Furthermore, negative effects were assessed and both clinician ratings and self-reports of inattention symptoms were used. A major limitation of the present study was the high attrition rate. This is a concern that needs to be managed in future RCTs of the CADDI protocol. Possibly more careful assessment of potential participants’ current capacity to engage in treatment and providing mandatory telephone support throughout treatment may decrease attrition. Nevertheless, other measures indicated feasibility of the CADDI protocol, including session attendance and treatment acceptability. Another limitation pertains to the fact that the clinician-administered assessments of inattentive symptoms were conducted by the group leaders. The findings presented here motivate further studies of the CADDI protocol. Currently, we are conducting a multicenter RCT comparing the effects of the CADDI protocol to the Hesslinger protocol (Hesslinger et al., Citation2004), based on lessons learned from the present feasibility study.

Geolocation

The study was conducted at four locations (Nynäshamn, Värmdö, Haninge, and Tyresö) in the southeast suburban area of Stockholm, Sweden.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants and the group leaders in the study, and Capio Psychiatry, Stockholm, Sweden for allocation of research time to EES.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the last author, BB. The data are not publicly available due to ethical/privacy restrictions.

References

- Addis, M. E., & Martell, C. R. (2004). Overcoming depression one step at a time: The new behavioral activation approach to getting your life back. New Harbinger Publications Incorporated.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Author.

- Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (1998). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder—A clinical workbook. Guilford Publications.

- Brown, T. E. (1996). Brown attention-deficit disorder scales for adolescents and adults. Psychological Corporation.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

- Cohen, S. A., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

- Combs, M. A., Canu, W. H., Broman-Fulks, J. J., Rocheleau, C. A., & Nieman, D. C. (2015). Perceived Stress and ADHD Symptoms in Adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(5), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054712459558

- Das, D., Cherbuin, N., Butterworth, P., Anstey, K. J., & Easteal, S. (2012). A population-based study of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and associated impairment in middle-aged adults. PLoS One, 7(2), e31500–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031500

- Devilly, G. J., & Borkovec, T. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31(2), 73–86.

- Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., & Bond, C. M. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: Development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One, 11(3), e0150205–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

- Fayyad, J., Sampson, N. A., Hwang, I., Adamowski, T., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Andrade, L. H. S. G., Borges, G., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Hu, C., Karam, E. G., Lee, S., Navarro-Mateu, F., O'Neill, S., Pennell, B.-E., Piazza, M., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV adult ADHD in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 9(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0208-3

- Fredriksen, M., Dahl, A. A., Martinsen, E. W., Klungsoyr, O., Faraone, S. V., & Peleikis, D. E. (2014). Childhood and persistent ADHD symptoms associated with educational failure and long-term occupational disability in adult ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 6(2), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0126-1

- Gotink, R. A., Meijboom, R., Vernooij, M. W., Smits, M., & Hunink, M. G. M. (2016). 8-week mindfulness based stress reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice—A systematic review. Brain and Cognition, 108, 32–41. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 26]Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.07.001

- Gudjonsson, G. H., Sigurdsson, J. F., Gudmundsdóttir, H. B., Sigurjónsdóttir, S., & Smari, J. (2010). The relationship between ADHD symptoms in college students and core components of maladaptive personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 601–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.12.015

- Hepark, S., Janssen, L., de Vries, A., Schoenberg, P. L. A., Donders, R., Kan, C. C., & Speckens, A. E. M. (2019). The efficacy of adapted MBCT on core symptoms and executive functioning in adults with ADHD: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(4), 312–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715613587

- Hesslinger, B., Philipsen, A., & Richter, H. (2004). Psychotherapy in adult ADHD: a workbook. Hogrefe Psykologiförlaget.

- Hesslinger, B., Van Elst, L. T., Nyberg, E., Dykierek, P., Richter, H., Berner, M., & Ebert, D. (2002). Psychotherapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults-a pilot study using a structured skills training program. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252(4), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-002-0379-0

- Hirvikoski, T., Lindström, T., Carlsson, J., Waaler, E., Jokinen, J., & Bölte, S. (2017). Psychoeducational groups for adults with ADHD and their significant others (PEGASUS): A pragmatic multicenter and randomized controlled trial. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 44, 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.04.005

- Hirvikoski, T., Waaler, E., Alfredsson, J., Pihlgren, C., Holmström, A., Johnson, A., Rück, J., Wiwe, C., Bothén, P., & Nordström, A. L. (2011). Reduced ADHD symptoms in adults with ADHD after structured skills training group: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(3), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.001

- Hirvikoski, T., Waaler, E., Lindström, T., Bölte, S., & Jokinen, J. (2015). Cognitive behavior therapy-based psychoeducational groups for adults with ADHD and their significant others (PEGASUS): An open clinical feasibility trial. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 7(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0141-2

- Janssen, L., Kan, C. C., Carpentier, P. J., Sizoo, B., Hepark, S., Schellekens, M. P. J., Donders, A. R. T., Buitelaar, J. K., & Speckens, A. E. M. (2019). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: A multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 49(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000429

- Knouse, L. E., Mitchell, J. T., Brown, L. H., Silvia, P. J., Kane, M. J., Myin-Germeys, I., & Kwapil, T. R. (2008). The expression of adult ADHD symptoms in daily life: An application of experience sampling methodology. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(6), 652–663. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707299411

- Knouse, L. E., Teller, J., & Brooks, M. A. (2017). Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatments for adult ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(7), 737–750. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000216

- Kooij, J. J. S., Bijlenga, D., Salerno, L., Jaeschke, R., Bitter, I., Balázs, J., Thome, J., Dom, G., Kasper, S., Nunes Filipe, C., Stes, S., Mohr, P., Leppämäki, S., Casas, M., Bobes, J., Mccarthy, J. M., Richarte, V., Kjems Philipsen, A., Pehlivanidis, A., … Asherson, P. (2019). Updated European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. European Psychiatry : The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 56(1), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.001

- Kooij, S. J. J., Boonstra, M. A., Swinkels, S. H. N., Bekker, E. M., de Noord, I., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2008). Reliability, validity, and utility of instruments for self-report and informant report concerning symptoms of ADHD in adult patients. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(4), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707299367

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Lopez, P., Torrente, F., Ciapponi, A., Lischinsky, A., Rojas, J., & Romano, M. (2018). Cognitive-behavioural interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults (Review). Cochrane Library, 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010840.pub2.www.cochranelibrary.com

- Morgensterns, E., Alfredsson, J., & Hirvikoski, T. (2016). Structured skills training for adults with ADHD in an outpatient psychiatric context: An open feasibility trial. ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 8(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-015-0182-1

- O’Neill, S., & Rudenstine, S. (2019). Inattention, emotion dysregulation and impairment among urban, diverse adults seeking psychological treatment. Psychiatry Research, 282, 112631 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112631

- Philipsen, A., Jans, T., Graf, E., Matthies, S., Borel, P., Colla, M., Gentschow, L., Langner, D., Jacob, C., Groß-Lesch, S., Sobanski, E., Alm, B., Schumacher-Stien, M., Roesler, M., Retz, W., Retz-Junginger, P., Kis, B., Abdel-Hamid, M., Heinrich, V., … Tebartz van Elst, L. (2015). Effects of group psychotherapy, individual counseling, methylphenidate, and placebo in the treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1199–1210. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2146

- Philipsen, A., Richter, H., Peters, J., Alm, B., Sobanski, E., Colla, M., Münzebrock, M., Scheel, C., Jacob, C., Perlov, E., Tebartz Van Elst, L., & Hesslinger, B. (2007). Structured group psychotherapy in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of an open multicentre study. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 195(12), 1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815c088b

- Poissant, H., Mendrek, A., Talbot, N., Khoury, B., & Nolan, J. (2019). Behavioral and cognitive impacts of mindfulness-based interventions on adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. Behavioural Neurology, 2019, 5682016–5682050. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5682050

- Posner, J., Polanczyk, G. V., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2020). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Lancet, 395(10222), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33004-1

- Rozental, A., Kottorp, A., Boettcher, J., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2016). Negative effects of psychological treatments: An exploratory factor analysis of the negative effects questionnaire for monitoring and reporting adverse and unwanted events. PLoS One, 11(6), e0157503–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157503

- Safren, S. A. (2005). Mastering your adult ADHD: A cognitive-behavioral treatment program. Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

- Safren, S. A., Otto, M. W., Sprich, S., Winett, C. L., Wilens, T. E., & Biederman, J. (2005). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(7), 831–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.07.001

- Safren, S. A., Sprich, S., Mimiaga, M. J., Surman, C., Knouse, L., Groves, M., & Otto, M. W. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy vs relaxation with educational support for medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 304(8), 875–880. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1192

- Salla, J., Galéra, C., Guichard, E., Tzourio, C., & Michel, G. (2019). ADHD symptomatology and perceived stress among French college students. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(14), 1711–1718. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716685841

- Sheehan, D. V. (1983). The Anxiety Disease. Charles Scribner and Sons.

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl. 20), 22–33.

- Solanto, M. V., Marks, D. J., Wasserstein, J., Mitchell, K., Abikoff, H., Alvir, J. M. J., & Kofman, M. D. (2010). Efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy for adult ADHD. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 958–968. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Vitola, E. S., Bau, C. H. D., Salum, G. A., Horta, B. L., Quevedo, L., Barros, F. C., Pinheiro, R. T., Kieling, C., Rohde, L. A., & Grevet, E. H. (2017). Exploring DSM-5 ADHD criteria beyond young adulthood: phenomenology, psychometric properties and prevalence in a large three-decade birth cohort. Psychological Medicine, 47(4), 744–754. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002853