ABSTRACT

Conformational conversion of the cellular prion protein, PrPC, into the abnormally folded isoform of prion protein, PrPSc, which leads to marked accumulation of PrPSc in brains, is a key pathogenic event in prion diseases, a group of fatal neurodegenerative disorders caused by prions. However, the exact mechanism of PrPSc accumulation in prion-infected neurons remains unknown. We recently reported a novel cellular mechanism to support PrPSc accumulation in prion-infected neurons, in which PrPSc itself promotes its accumulation by evading the cellular inhibitory mechanism, which is newly identified in our recent study. We showed that the VPS10P sorting receptor sortilin negatively regulates PrPSc accumulation in prion-infected neurons, by interacting with PrPC and PrPSc and trafficking them to lysosomes for degradation. However, PrPSc stimulated lysosomal degradation of sortilin, disrupting the sortilin-mediated degradation of PrPC and PrPSc and eventually evoking further accumulation of PrPSc in prion-infected neurons. These findings suggest a positive feedback amplification mechanism for PrPSc accumulation in prion-infected neurons.

INTRODUCTION

Prions are causative agents of prion diseases, a group of fatal neurodegenerative disorders including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans and bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie in animals.Citation1 They are widely believed to consist of the abnormally folded, amyloidogenic isoform of prion protein, designated PrPSc.Citation1 PrPSc is produced through conformational conversion of the cellular prion protein, PrPC, by unknown mechanisms.Citation1 PrPC is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane glycoprotein expressed most abundantly in brains, particularly by neurons.Citation2 The constitutive conversion of PrPC into PrPSc leads to accumulation of PrPSc in brains. We and others have shown that the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc is a key pathogenic event in prion disease, by demonstrating that mice devoid of PrPC neither developed the disease nor propagated prions or accumulated PrPSc in their brains after intracerebral inoculation with prions.Citation3–6 Most pathogens usually evade host defense mechanisms to propagate themselves in their hosts. However, the host defense mechanism against prions to suppress prion propagation, or PrPSc accumulation, remains unknown.

The vacuolar protein sorting-10 protein (VPS10P)-domain receptors, including sortilin, SorLA, SorCS1, SorCS2 and SorCS3, are multi-ligand type I transmembrane proteins abundantly expressed in brains and involved in neuronal function and viability.Citation7,8 They function as a cargo receptor to deliver a number of cargo proteins to their subcellular compartments through the VPS10P domain in the extracellular luminal N-terminus.Citation7,8 Accumulating lines of evidence indicate that altered VPS10P receptor-mediated trafficking could be involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's diseaseCitation9–12 and frontotemporal lobar degeneration.Citation13 Sortilin mediates intracellular trafficking of the amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme BACE114 and the neurotrophic factor receptors Trks.Citation15 SorLA and SorCS1 are involved in APP transport.Citation9,11

We recently reported that sortilin negatively regulates PrPSc accumulation by sorting PrPC and PrPSc to lysosomes for degradation, and that PrPSc accumulation itself impairs the sotrtilin-mediated degradation of PrPC and PrPSc by stimulating lysosomal degradation of sortilin, thereby evoking further accumulation of PrPSc in prion-infected cells.Citation16 These findings suggest that the sortilin-mediated lysosomal degradation of PrPC and PrPSc could be a host defense mechanism against prions, and that prions, or PrPSc, could propagate in infected neurons by evading the sortilin-mediated defense mechanism by inducing lysosomal degradation of sortilin.

SORTILIN IS A NEGATIVE REGULATOR FOR PRPSc ACCUMULATION

We found that PrPC directly interacts with sortilin, but not with other VPS10P molecules, on the plasma membrane in PrPC-overexpressing neuroblastoma N2a cells, designated N2aC24 cells.Citation16 The interaction of both molecules was also confirmed in mouse brain homogenates.Citation16 SiRNA-mediated knockdown of sortilin increased PrPSc in prion-infected N2aC24L1-3 cells, which are N2aC24 cells persistently infected with 22L scrapie prions.Citation16 In contrast, overexpression of sortilin in N2aC24L1-3 cells decreased PrPSc.Citation16 We also showed that sortilin-knockout mice had accelerated prion disease caused by early accumulation of PrPSc in their brains after infection with RML scrapie prions.Citation16 These results indicate that sortilin could negatively regulate PrPSc accumulation in prion-infected cells and mice.

SORTILIN TRAFFICS PRPC TO NON-RAFT DOMAINS AND TO LATE ENDOSOMES/LYSOSOMES

PrPC is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and trafficked to the plasma membrane through the Golgi apparatus.Citation17 PrPC undergoes several posttranslational modifications during its biosynthesis, including cleavage of the N-terminal signal peptide, removal of the C-terminal peptide for attachment of a GPI anchor at the C-terminus and formation of a disulfide bond at the C-terminal domain in the ER, and addition of two core N-linked oligosaccharides at the C-terminal domain in the ER that are further modified in the ER and then in the Golgi apparatus.Citation17 Like other GPI-anchored proteins, PrPC is predominantly located at raft domains and, to a lesser extent, at non-raft domains.Citation16,17 After internalization, some PrPC molecules are delivered back to the plasma membrane directly or indirectly via the recycling endosome compartments and others are transported to lysosomes for degradation.Citation18 Copper and zinc stimulate endocytosis of PrPC by binding to histidine residues in the octapeptide repeat (OR) region located in the N-terminal domain.Citation19–21 It has been postulated that PrPC interacts with an as yet unidentified raft molecule via the N-terminal domain including the OR region, thereby being retained at raft domains.Citation20 The binding of copper or zinc to the OR region causes structural changes in the N-terminal interacting region of PrPC, thereby PrPC leaves raft domains to non-raft domains to be endocytosed via the clathrin-dependent pathway.Citation20 Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 has been reported to be involved in the clathrin-dependent endocytosis of PrPC.Citation22 The clathrin-independent pathways including caveolae, which is considered to be formed by clustering raft domains, or caveolae-like domains have been also reported to mediate the endocytosis of PrPC.Citation18

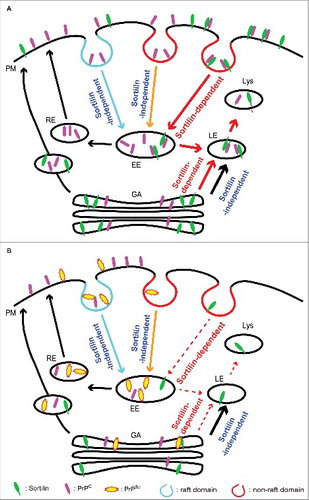

We found that sortilin was predominantly located at non-raft domains in prion-uninfected N2aC24 cells.Citation16 Sortilin knockout caused marked shift in localization of PrPC from non-raft domains to raft domains in N2aC24 cells and mouse brains.Citation16 These findings suggest that sortilin could function to recruit PrPC from raft domains to non-raft domains. We also found that, after internalization, PrPC was transported to both late endosomes and recycling endosomes in N2aC24 cells.Citation16 However, PrPC was preferentially transported to recycling endosomes with reduced localization at late endosomes/lysosomes in sortilin-knockdown and -knockout N2aC24 cells,Citation16 indicating that sortilin also could function as an endocytic receptor for PrPC at non-raft domains to be sent to lysosomes for degradation (). Consistent with this, sortilin-deficient N2aC24 cells showed higher PrPC on their plasma membranes than control N2aC24 cells.Citation16 Sortilin-knockout mice also showed higher PrPC in their brains compared to WT mice.Citation16 Moreover, inhibition of lysosomal enzymes by NH4Cl increased PrPC markedly in N2aC24 cells, but only slightly in sortilin-knockout N2aC24 cells.Citation16

FIGURE 1. A model of the sortilin-mediated intracellular trafficking of PrPC and PrPSc in prion-uninfected and infected neurons. (A) Sortilin-dependent and -independent endocytosis of PrPC in uninfected neurons. Sortilin mediates endocytosis of PrPC on the plasma membrane (PM), particularly at non-raft domains, via the clathrin-dependent pathway to early endosomes (EE) and then traffics it to late endosomes/lysosomes (LE/Lys) for degradation. Other PrPC molecules are trafficked either to LE/Lys for degradation or to the recycling endosome (RE) pathway in a sortilin-independent way. There also might be sortilin-dependent and -independent trafficking pathways from the Golgi apparatus (GA) to LE/Lys for degradation. (B) Intracellular trafficking of PrPC and PrPSc in prion-infected neurons. Prion infection stimulates lysosomal degradation of sortilin via an unknown mechanism, thereby impairing the sortilin-mediated trafficking of PrPC and PrPSc to LE/Lys for degradation. As a result, PrPC and PrPSc are increased at raft domains and endocytosed via the sortilin-independent pathway to RE, causing accumulation of PrPSc and increasing conversion of PrPC into PrPSc in prion-infected neurons. PrPSc could undergo retrograde transport to the GA. However, sortilin might also be functionally impaired in the GA, thereby being unable to traffic PrPSc in the GA to LE/Lys for degradation. The decreased degradation of PrPSc in LE/Lys and the increased conversion of PrPC into PrPSc in raft domains or RE could both contribute to the constitutive production of PrPSc in prion-infected neurons. Dashed arrows indicate restricted trafficking.

The plasma membrane or raft domains are considered to be major sites for the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc,Citation23 although the exact site of PrPSc production remains controversial. It is thus likely that sortilin could negatively regulate PrPSc accumulation by reducing PrPC on the plasma membrane, particularly at raft domains through recruiting PrPC to non-raft domains from raft domains and sorting it to the late endosome/lysosome protein degradation pathway.

SORTILIN IS INVOLVED IN DEGRADATION OF PRPSc

We also found that sortilin could function to direct PrPSc for degradation.Citation16 Sortilin interacted with PrPSc in prion-infected N2aC24L1-3 cells.Citation16 Sortilin-knockout significantly slowed down the degradation of PrPSc in N2aC24 cells infected with RML or 22L prions.Citation16 PrPSc is found at various intracellular compartments, including the plasma membrane, various endosomal compartments such as early and late endosomes, recycling endosomes, and lysosomes, and the Golgi apparatus.Citation18 Enzymatic release of PrPC from the plasma membrane by phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C was shown to reduce PrPSc in infected cells,Citation24 and formation of PrPSc was inhibited by lowered temperature,Citation25 which blocks the endocytosis and internalization of PrPC. These suggest that the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc might occur at the plasma membrane, where exogenous PrPSc is likely to first contact endogenous PrPC, or after its internalization in the endosomal compartment. Internalized PrPSc could also undergo retrograde transport to the Golgi apparatus and/or to the ER,Citation26,27 where the transported PrPSc might trigger the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc. PrPSc molecules on the plasma membrane are trafficked to lysosomes for degradation via the endolysosomal pathway.Citation28,29 The PrPSc retrogradely transported to the Golgi apparatus are subjected to Golgi quality control and trafficked to lysosomes for degradation.Citation27 Sortilin localizes in para-nuclear vesicles, in the trans-Golgi network, and on the plasma membrane.Citation30,31 It is thus possible that sortilin could be involved in both degradation trafficking pathways of PrPSc. However, sortilin and PrPSc molecules differed in their microdomain localization on the plasma membrane in N2aC24L1-3 cells. Sortilin was predominantly detected in non-raft fractions while PrPSc was exclusively located in raft fractions ().Citation16 Therefore, the sortilin-mediated lysosomal degradation of PrPSc located on the plasma membrane might be a minor event.

PRPSc STIMULATES DEGRADATION OF SORTILIN IN LYSOSOMES

Interestingly, we found that sortilin was markedly reduced in both prion-infected cells and mouse brains, and that the reduced sortilin levels in prion-infected cells were recovered by treatment with lysosomal inhibitors but not with proteasomal inhibitor.Citation16 These findings suggest that sortilin is increasingly degraded in lysosomes in prion-infected cells. We also found that PrPSc accumulation preceded the reduction of sortilin in N2aC24 cells freshly infected with RML prions.Citation16 Immunofluorescent staining showed that sortilin was barely detectable in PrPSc-positive cells but still abundantly observed in PrPSc-negative cells.Citation16 It is thus likely that PrPSc produced after prion infection could stimulate sortilin degradation in lysosomes in a cell-autonomous fashion, and that the negative role of sortilin in PrPSc accumulation could be impaired in prion-infected cells, therefore PrPSc progressively accumulates in prion-infected neurons.

CONCLUSIONS

We presented a novel accumulation mechanism of PrPSc through degradation of sortilin. Sortilin could form the host defense mechanism against prions, by functioning to sort PrPC and PrPSc to the late endosomal/lysosomal compartments for degradation (, ). Conversely, PrPSc itself stimulates degradation of sortilin in lysosomes, reducing sortilin levels and impairing its defense function against prions. As a result, PrPC is increasingly converted to PrPSc, and PrPSc degradation is delayed, and eventually PrPSc progressively accumulates in prion-infected cells (). Accelerating the sortilin-mediated lysosomal degradation of PrPC and PrPSc might be beneficial for treatment of prion diseases.

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Prof. Horiuchi (Hokkaido University) for anti-PrP antibody clone 132 and N2a cells, and Prof. Doh-ura (Tohoku University) for ScN2a cells. We also would like to thank Mitsuru Tomita, Masashi Yano, Junji Chida, Hideyuki Hara and Nandita Rani Das at Tokushima University and Anders Nykjaer at Aarhus University for their contributions.

FUNDING

This work was partly supported by Pilot Research Support Program in Tokushima University, Naito Foundation, JSPS KAKENHI 26460557 and MEXT KAKENHI 17H05702 to KU, and JSPS KAKENHI 26293212, MEXT KAKENHI 15H01560 and 17H05701, and Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Diseases of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) to SS.

REFERENCES

- Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13363–83. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. PMID:9811807

- Stahl N, Borchelt DR, Hsiao K, Prusiner SB. Scrapie prion protein contains a phosphatidylinositol glycolipid. Cell. 1987;51:229–40. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90150-4. PMID:2444340

- Bueler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner RA, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissmann CWeissmann C. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell. 1993;73:1339–47. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. PMID:8100741

- Prusiner SB, Groth D, Serban A, Koehler R, Foster D, Torchia M, Burton D, Yang SL, DeArmond SJ. Ablation of the prion protein (PrP) gene in mice prevents scrapie and facilitates production of anti-PrP antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10608–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.22.10608. PMID:7902565

- Manson JC, Clarke AR, McBride PA, McConnell I, Hope J. PrP gene dosage determines the timing but not the final intensity or distribution of lesions in scrapie pathology. Neurodegeneration. 1994;3:331–40. PMID:7842304

- Sakaguchi S, Katamine S, Shigematsu K, Nakatani A, Moriuchi R, Nishida N, Kurokawa K, Nakaoke R, Sato H, Jishage K, et al. Accumulation of proteinase K-resistant prion protein (PrP) is restricted by the expression level of normal PrP in mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted strain of the Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent. J Virol. 1995;69:7586–92. PMID:7494265

- Nykjaer A, Lee R, Teng KK, Jansen P, Madsen P, Nielsen MS, Jacobsen C, Kliemannel M, Schwarz E, Willnow TE, et al. Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature. 2004;427:843–8. doi:10.1038/nature02319. PMID:14985763

- Nykjaer A, Willnow TE. Sortilin: a receptor to regulate neuronal viability and function. Trends in neurosciences. 2012;35:261–70. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.003. PMID:22341525

- Rogaeva E, Meng Y, Lee JH, Gu Y, Kawarai T, Zou F, Katayama T, Baldwin CT, Cheng R, Hasegawa H, et al. The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:168–77. doi:10.1038/ng1943. PMID:17220890

- Caglayan S, Takagi-Niidome S, Liao F, Carlo AS, Schmidt V, Burgert T, Kitago Y, Füchtbauer EM, Füchtbauer A, Holtzman DM, et al. Lysosomal sorting of amyloid-beta by the SORLA receptor is impaired by a familial Alzheimer's disease mutation. Sci Translat Med. 2014;6:223ra20. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3007747.

- Reitz C, Tosto G, Vardarajan B, Rogaeva E, Ghani M, Rogers RS, Conrad C, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Fallin MD, et al. Independent and epistatic effects of variants in VPS10-d receptors on Alzheimer disease risk and processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP). Translat Psychiatry. 2013;3:e256. doi:10.1038/tp.2013.13. PMID:23673467

- Reitz C, Cheng R, Rogaeva E, Lee JH, Tokuhiro S, Zou F, Bettens K, Sleegers K, Tan EK, Kimura R, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between variants in SORL1 and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:99–106. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.346. PMID:21220680

- Hu F, Padukkavidana T, Vaegter CB, Brady OA, Zheng Y, Mackenzie IR, Feldman HH, Nykjaer A, Strittmatter SM.. Sortilin-mediated endocytosis determines levels of the frontotemporal dementia protein, progranulin. Neuron. 2010;68:654–67. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.034. PMID:21092856

- Finan GM, Okada H, Kim TW. BACE1 retrograde trafficking is uniquely regulated by the cytoplasmic domain of sortilin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12602–16. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.170217. PMID:21245145

- Vaegter CB, Jansen P, Fjorback AW, Glerup S, Skeldal S, Kjolby M, Richner M, Erdmann B, Nyengaard JR, Tessarollo L, et al. Sortilin associates with Trk receptors to enhance anterograde transport and neurotrophin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:54–61. doi:10.1038/nn.2689. PMID:21102451

- Uchiyama K, Tomita M, Yano M, Chida J, Hara H, Das NR, Nykjaer A, Sakaguchi S. Prions amplify through degradation of the VPS10P sorting receptor sortilin. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(6):e1006470. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006470. PMID:28665987

- Harris DA. Trafficking, turnover and membrane topology of PrP. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:71–85. doi:10.1093/bmb/66.1.71. PMID:14522850

- Campana V, Sarnataro D, Zurzolo C. The highways and byways of prion protein trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:102–11. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.12.002. PMID:15695097

- Pauly PC, Harris DA. Copper stimulates endocytosis of the prion protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33107–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.50.33107. PMID:9837873

- Taylor DR, Watt NT, Perera WS, Hooper NM. Assigning functions to distinct regions of the N-terminus of the prion protein that are involved in its copper-stimulated, clathrin-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5141–53. doi:10.1242/jcs.02627. PMID:16254249

- Lee KS, Magalhaes AC, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Prado MA. Internalization of mammalian fluorescent cellular prion protein and N-terminal deletion mutants in living cells. J Neurochem. 2001;79:79–87. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00529.x. PMID:11595760

- Taylor DR, Hooper NM. The low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) mediates the endocytosis of the cellular prion protein. Biochem J. 2007;402:17–23. doi:10.1042/BJ20061736. PMID:17155929

- Taraboulos A, Scott M, Semenov A, Avrahami D, Laszlo L, Prusiner SB. Cholesterol depletion and modification of COOH-terminal targeting sequence of the prion protein inhibit formation of the scrapie isoform. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:121–32. doi:10.1083/jcb.129.1.121. PMID:7698979

- Enari M, Flechsig E, Weissmann C. Scrapie prion protein accumulation by scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells abrogated by exposure to a prion protein antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9295–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.151242598. PMID:11470893

- Borchelt DR, Taraboulos A, Prusiner SB. Evidence for synthesis of scrapie prion proteins in the endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16188–99. PMID:1353761

- Beranger F, Mange A, Goud B, Lehmann S. Stimulation of PrP(C) retrograde transport toward the endoplasmic reticulum increases accumulation of PrP(Sc) in prion-infected cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38972–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205110200. PMID:12163492

- Goold R, McKinnon C, Rabbanian S, Collinge J, Schiavo G, Tabrizi SJ. Alternative fates of newly formed PrPSc upon prion conversion on the plasma membrane. J cell Sci. 2013;126:3552–62. doi:10.1242/jcs.120477. PMID:23813960

- Yamasaki T, Suzuki A, Shimizu T, Watarai M, Hasebe R, Horiuchi M. Characterization of intracellular localization of PrP(Sc) in prion-infected cells using a mAb that recognizes the region consisting of aa 119–127 of mouse PrP. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:668–80. doi:10.1099/vir.0.037101-0. PMID:22090211

- Veith NM, Plattner H, Stuermer CA, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Burkle A. Immunolocalisation of PrPSc in scrapie-infected N2a mouse neuroblastoma cells by light and electron microscopy. Europ J Cell Biol. 2009;88:45–63. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.08.001. PMID:18834644

- Petersen CM, Nielsen MS, Nykjaer A, Jacobsen L, Tommerup N, Rasmussen HH, Roigaard H, Gliemann J, Madsen P, Moestrup SK. Molecular identification of a novel candidate sorting receptor purified from human brain by receptor-associated protein affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3599–605. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.6.3599. PMID:9013611

- Nielsen MS, Madsen P, Christensen EI, Nykjaer A, Gliemann J, Kasper D, Pohlmann R, Petersen CM. The sortilin cytoplasmic tail conveys Golgi-endosome transport and binds the VHS domain of the GGA2 sorting protein. Embo J. 2001;20:2180–90. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.9.2180. PMID:11331584