Abstract

Introduction

Despite the importance of better understanding how loneliness is associated with physical and mental health symptoms and disorders, and who is at greatest risk, demographic information pertaining to sexuality is often not collected. Although some studies evidence prevalence rates of loneliness amongst sexual minority individuals to be higher when compared to heterosexual individuals, no systematic approaches to examine and compare the literature have been taken. This comparative meta-analysis examined loneliness between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals.

Method

To identify studies, published studies were searched from the following databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Scopus, and Cochrane. Studies that were published in English, compared sexual minorities and heterosexuals; measured loneliness; and presented quantitative data were included.

Result

Four articles were included in the review, reporting data from 481 individuals who identified as sexual minorities and 4176 as heterosexuals. The 4 studies showed that individuals who identified as sexual minorities reported higher ratings of loneliness than heterosexuals (d = 0.352, p = 0.019).

Conclusion

Interventions are needed at the individual and societal level to decrease the loneliness experienced by sexual minorities. This is the first paper to provide aggregated data on loneliness that covers the life span amongst sexual minorities.

Loneliness is a significant health problem (Beutel et al., Citation2017). Rooted in the discrepancy model of loneliness (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982), loneliness is defined as an emotional state of dissatisfaction individuals feel due to the perception that their social needs are not met by desired quantities or qualities of social interactions (see Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982; Russell et al., Citation1980). Loneliness can be situational, an experience that happens at a given moment in one’s life, or chronic, where one feels lonely for a prolonged duration of time (de Jong Gierveld, Citation1998; Young, Citation1982).

Data from the European Social Survey shows that 30 million Europeans (approximately 7%) report to feel lonely, with higher rates of loneliness reported by individuals who experience poor health, live alone, are widowed, earn a low income or are unemployed, and live in Eastern or Southern Europe (d’Hombres et al., Citation2018; Yang & Victor, Citation2011). Differences in rates of loneliness between males and females or those who live in rural or urban areas were found to be minimal. Other studies and reviews have shown loneliness to be associated with poor physical and mental health, including poor cardiovascular health, cancer, dementia, depression, anxiety, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, low wellbeing, and substance use (Beutel et al., Citation2017; Deckx et al., Citation2014; Leigh-Hunt et al., Citation2017). High levels of loneliness have also been associated with all-cause mortality (Leigh-Hunt et al., Citation2017).

Despite the importance of better understanding how loneliness is associated with physical and mental health symptoms and disorders, and who is at greatest risk, demographic information pertaining to sexuality is often not collected (IOM, Citation2011; Westwood et al., Citation2020). Systematic exclusion of sexuality data from health research has resulted in a health knowledge deficit and a lack of evidence-based interventions, especially for loneliness, for sexual minority individuals. Here, sexual minority individuals are those who self-report having a sexual identity, orientation, or practice that is different from the majority of society (i.e., non-heterosexual) (Kann et al., Citation2016). This may include, but is not limited to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning individuals (LGBTQ+) (The Centre, Citation2020). Therefore, direct comparisons that investigate health inequities between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals are essential and needed (Westwood et al., Citation2020).

Research pertaining to loneliness amongst sexual minority individuals from Canada has shown that approximately 13-24% of sexual minority men experience loneliness most or all of the time (Salway et al., Citation2020). Other cross-sectional work has shown that loneliness amongst sexual minority individuals to be 34.7% (Kneale, Citation2016).

Amongst sexual minority individuals, loneliness is associated with poor mental health amongst youth and adolescents (Westefeld et al., Citation2001; Yadegarfard et al., Citation2014), adults (Mereish & Poteat, Citation2015), and older adults (D’Augelli et al., Citation2001). Comparisons between age ranges has shown sexual minority individuals who are older to report the highest levels of loneliness (Hughes, Citation2016). Loneliness has also shown to be associated with experiences of rejection and discrimination (Kuyper & Fokkema, Citation2010), feelings of internalized homophobia and low optimism (Jacobs & Kane, Citation2012), lower body satisfaction (Chaney, Citation2008), and higher engagement in risky sexual behaviors (Martin & Knox, Citation1997). Additionally, sexual minority individuals who lack close relationships, including stable partners, experience higher rates of loneliness (Fish & Weis, Citation2019; Fokkema & Kuyper, Citation2009; Grossman et al., Citation2000; Hyun-Jun & Fredriksen-Goldsen, Citation2016).

Although some studies evidence prevalence rates of loneliness amongst sexual minority individuals to be higher when compared to heterosexual individuals (e.g., Kneale, Citation2016; Salway et al., Citation2020), no systematic approaches to examine and compare the literature have been taken. Furthermore, no aggregated, meta-analytic approaches have been made to directly compare self-reported loneliness between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. As a result, this comparative meta-analysis aimed to examine loneliness between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals.

Methods

This comparative meta-analysis adhered to PRISMA guidelines to ensure methods and results were reported in a transparent and comprehensive manner (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic search strategy was developed by both PG and FF. To identify studies, published studies were searched from the following databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Scopus, and Cochrane from inception to September 2020. No limits were imposed on study dates. We applied the following filter (where applicable): English. The search strategy is presented in .

Table 1. Search strategy and MeSH terms.

Study inclusion

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria:

Published in full in English;

Compared sexual minorities and heterosexuals;

Included a measure of loneliness; and

Presented quantitative data.

Study exclusion

Studies were excluded if they were not published in English; did not provide an appropriate control sample (i.e., sexual minorities or heterosexuals); did not report a quantitative measure of loneliness; or used a qualitative design. Gray literature, including review articles, book chapters, books, dissertations, and conference abstracts, was also excluded. Where studies did not provide full details of loneliness results, an email was sent to the corresponding author. Both authors screened the articles independently to assess study eligibility. The authors met and confirmed study eligibility. Discrepancies between the authors over study eligibility were resolved through discussion until an agreement was achieved.

Data extraction

Data was extracted by both authors independently. The authors met afterwards to ensure all necessary data was extracted. Standardized data collection forms were used in order to report the following data:

Year of publication, country, sample size, age, gender, sex, and sexuality.

Loneliness: (i) scale used and data collection methods, and (ii) outcomes, including means and standard deviations.

Data analysis

Raw data (mean, standard deviations, and n) were sourced for loneliness. Effect sizes were calculated through the standardized difference in means (d), as this could have been calculated across different measures of loneliness used in different studies. Overall, effect sizes were pooled across included studies in order to calculate a weighted estimate with 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were conducted using OpenMetaAnalyst (Wallace et al., Citation2009). Random-effects models were applied to this meta-analysis to account for heterogeneity (DerSimonian & Laird, Citation1986). Cochran’s Q was used to assess variance between studies. Variance between studies was reported as I2. The degree of potential publication bias was assessed by a funnel plot.

Risk of bias

To describe the risk of bias of the included studies, an 8-item tool for cross-sectional studies was used (Hoy et al., Citation2012). The tool assessed the internal and external validity of each study and provided an overview of the main methodological characteristics. Risk of bias was assessed by each author independently. Overall agreement between the authors was 100%.

Results

Literature search

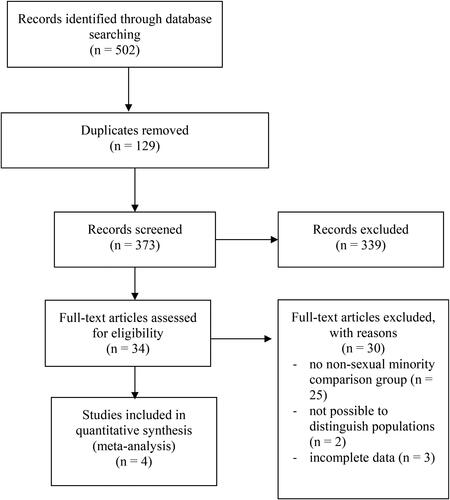

The PRISMA search process is presented in . The database search returned 502 articles. Of the 502 articles, 129 duplicates were removed and 373 articles were screened. In total, 339 articles did not meet inclusion criteria and 34 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. From these 34 articles, 30 were excluded for the following reasons: no heterosexual comparison group (n = 25); not possible to distinguish populations (n = 2); and incomplete data (e.g., means, SD) (n = 3). A list of full-text excluded articles can be seen in .

Table 2. Full-text excluded articles with reasons.

In total, 4 articles were included in the review, reporting data from 481 individuals who identified as sexual minorities and 4176 individuals who identified as heterosexual. Ages for both sexual minorities and heterosexuals ranged from 8 years to 92 years. Individuals who identified as girls, women, or female represented 72.2% of the total population under review (n = 4657, 67.2% (sexual minority), 72.3% (heterosexual)). Studies were conducted in USA (n = 3) (Beam & Collins, Citation2019; Keenan et al., Citation2018; Westefeld et al., Citation2001), and the UK (n = 1) (Rivers & Noret, Citation2008). Measures of loneliness included the UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 (Russel, Citation1996) and Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale (Asher & Wheeler, Citation1985). Rivers and Noret (Citation2008) used one discrete item on loneliness, asking if participants felt lonely. Included study characteristics are presented in .

Table 3. Included study characteristics.

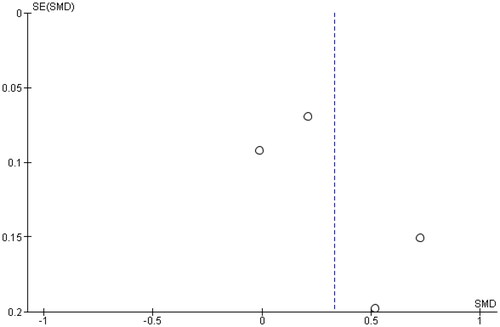

Overall, the included studies displayed a low risk of bias for both internal and external validity. The risk of bias results can be seen in . A generated funnel plot indicated no publication bias (Higgens & Green, Citation2011). The publication bias funnel plot can be seen in .

Table 4. Risk of bias assessment.

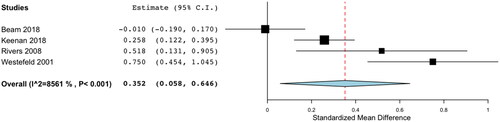

The 4 studies showed that individuals who identified as sexual minorities (n = 481) reported higher ratings of loneliness than individuals who identified as heterosexuals (n = 4105) (d = 0.352, p = 0.019). There was substantial heterogeneity detected (Q = 20.843, p < 0.001, I2 = 85.61%) ().

Discussion

The purpose of this comparative meta-analysis was to examine whether a difference in loneliness existed between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. Overall, results from this meta-analysis show that sexual minority individuals are more likely to report feelings of loneliness than heterosexual individuals. Results illustrate that a small to medium effect size exists with regards to loneliness and identifying as a sexual minority individual. This effect was seen across a wide range of ages, from children to individuals who are older. This is the first meta-analysis to quantitatively aggregate comparative findings on loneliness between individuals who identify as sexual minorities and heterosexuals.

The results of this meta-analysis reinforce and support the findings of previous qualitative reviews that have investigated loneliness amongst sexual minority individuals (Fish & Weis, Citation2019; Freedman & Nicolle, Citation2020; Garcia et al., Citation2020). Given loneliness is associated with poor physical, mental, and social health, and that sexual minority individuals are at higher risk of reporting to be lonely, interventions need to distinctly address the specific needs of this population. Such needs may be addressed across individual, social, and structural dimensions (Garcia et al., Citation2020; Westwood et al., Citation2020).

Previous research, which has also investigated concepts of social isolation amongst younger as well as older sexual minority individuals (Fish & Weis, Citation2019; Garcia et al., Citation2020), has shown that the creation of enabling environments that are identity safe and foster social connectedness may be most beneficial in helping individuals address loneliness.

Regarding younger sexual minority individuals, Garcia et al. (Citation2020) showed in their review that social connectedness in the LGBTQ + communities was associated with higher feelings of wellbeing, self-esteem, self-acceptance, and self-worth and value. It was also found to be associated with lower levels of internalized homophobia. The creation of enabling environments, ones that were identity-safe spaces be they in person or online, provided opportunities for relationship building and support for dealing with rejection and isolation. For younger individuals, Genders and Sexualities Alliances (GSAs) may play an important role in helping sexual minority individuals develop a sense of self and belonging within a community. A sense of belonging has been shown to be a protective factor against loneliness (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Mellor et al., Citation2008).

Amongst older sexual minority individuals, stronger and larger social networks that aim to create a sense of belonging have also been shown to have a positive impact on addressing loneliness (Fish & Weis, Citation2019). Specifically, creating built spaces, like bars, clubs, and cafes, for people to come together (Kneale, Citation2016); creating affinity or activity groups (Ceatha et al., Citation2019; Wilkens, Citation2015); and participating in formal and informal social events or rituals that shape social and cultural identity (Glass & Few-Demo, Citation2013). Furthermore, living in close proximity to friends in one’s neighborhood has also been found to be associated with increased frequency of contact, increased feelings of belonging, and decreased loneliness (Green, Citation2016). Green (Citation2016) found that overall, LGBT adults in comparison to heterosexual adults were more likely to have weaker social networks, where they were less likely to have any social contact and receive informal support. Similar findings were made by Kneale (Citation2016), that showed that LGB people in comparison to heterosexual individuals have higher rates of renting housing in the private sector and lower rates of home ownership (Kneale, Citation2016), thus creating the potential for housing instability and frequent needs to move. Additionally, LGB people were more likely to experience income inequality, especially at lower income ranges. Both income and housing instability have been associated with reported feelings of loneliness (Kneale, Citation2016). Support for and access to affordable housing, across adulthood, needs to be a priority for sexual minority individuals as it has been shown to be a key determinant of mental and physical health (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019). To address the need for affordable and inclusive housing, arguments have been made for the creation of LGBTQ + specific care homes for older sexual minority individuals (King & Stoneman, Citation2017).

Last but not least, loneliness has been found to be related to minority stress factors such as experiences and expectations of stigmatization that have an impact on mental and physical health (Mereish & Poteat, Citation2015). Hence, it has been suggested that interventions to decrease societal sexual prejudice (Kuyper & Fokkema, Citation2010), and recognition of sexual minority rights, can positively impact on feelings of loneliness (Stojanovski et al., Citation2015).

Clinical significance

Because of the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis, evaluations of loneliness amongst different genders and sexes, age groups, and ethnicities was not possible. As indicated by Westwood et al. (Citation2020), there is a need to establish a mental health research agenda to address health inequalities amongst sexual minority individuals. Specifically, the need for comparative data to better understand health inequalities in comparison to non-sexual minority individuals so that deficits in health and healthcare services can be identified and addressed through specific interventions (Jennings et al., Citation2019). Results from the National LGBT Survey in the UK found that of those individuals who tried to access mental health services, 50% did not find the process easy. Individuals surveyed stated they encountered stigma and discrimination throughout the process with 22% indicating they dealt with unsupportive general practitioners (Government Equalities Office, Citation2018). Previous research has shown that LGBT individuals, in comparison to heterosexuals, were more likely to delay health care use (Jennings et al., Citation2019). The collection of demographic data on sexuality and gender is essential for the development of future interventions and services that are accessible to sexual minority individuals (Gorczynski & Brittain, Citation2016; Gorczynski & Fasoli, Citation2020). To integrate evaluations and services about loneliness into clinical practice, clinicians will have to consider the therapeutic relationships they have with their patients (Campaign to End Loneliness, Citation2015). For instance, clinicians should consider how to approach the topic of loneliness with their patients, be it through in-person and open discussions or through pre-appointment self-administered brief questionnaires like the Three-Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., Citation2004). Clinicians should consider how suitably trained they are to evaluate and discuss loneliness especially in the context of their patients’ sexuality and gender. Clinicians will require training in evaluations and discussions of loneliness and will require support from their colleges and organizational bodies as well as local health and voluntary sectors to ensure that their patients’ loneliness is acknowledge and addressed in a meaningful manner. Clinicians should also consider how they can devote sufficient time to the initial and on-going evaluations of loneliness with their patients. Lastly, clinicians should consider what resources and services they can provide to their patients.

Limitations

Despite a robust search and evaluation of all included articles, a number of limitations should be addressed. First, efforts were made to contact the study authors of excluded studies where limited data was published. Such information may have led to the inclusion of studies in the meta-analysis and expanded our understanding of loneliness between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. In the future, researchers should make every effort to publish full results to minimize publication bias. Ultimately, the limited number of included studies may limit the overall generalizability of our findings. In particular, data referred mostly to USA and it would be interesting to compare data from countries varying on attitudes toward sexual minorities and LGBTQ + rights (ILGA, Citation2020). Second, Rivers and Noret (Citation2008) did not use a valid or reliable measure of loneliness in their study. Instead, they assessed loneliness through the use of a single question. Overall, the Rivers and Noret (Citation2008) study exhibited a higher risk of bias than other included studies and their results must be viewed with caution. Lastly, there was substantial heterogeneity detected in our comparative meta-analysis. Overall, studies included populations of sexual minorities that differed in age and how individual chose to self-identify their sexuality (e.g., sexual minority vs current/previous same sex relationship vs LGBTQ+). Additionally, different measures of loneliness were used which may have further limited the generalizability of the results. Also, limited data was available concerning race and ethnicity. Future longitudinal research needs to be mindful as to what demographic data is collected (i.e., information concerning multiple protected characteristics), how loneliness is measured (i.e., through reliable and valid measures), the temporal nature of loneliness (i.e., temporary or chronic), and how loneliness is contextualized (i.e., is it the result of social exclusion or a public health emergency). Researchers should also investigate how clinicians can best meet the needs of patients with respect to their loneliness. Such evidence is essential in the construction of any intervention that will be culturally competent and contextually well-suited.

Overall, the results of our meta-analysis show that sexual minority individuals were more likely to report feeling lonely than heterosexual individuals. Given the limitations of included studies, researchers should aim to be inclusive of demographic information that may lead to a better understanding of loneliness amongst sexual minority and heterosexual individuals and address publication biases that may limit the generalizability of findings. Nevertheless, our findings contribute to the recent work on loneliness among sexual minority individuals (Fish & Weis, Citation2019; Freedman & Nicolle, Citation2020; Garcia et al., Citation2020) and suggest the need to consider interventions at the individual and societal level to decrease the loneliness experienced by sexual minorities. This is the first paper to provide quantitative aggregated data on loneliness that covers the life span, from children to older individuals, amongst sexual minorities. Such data will allow for the comparison of future data and aid in policy and intervention development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adam, B. D., Betancourt, G., & Serrano Sanchez, A. A. (2011). Development of an HIV prevention and life skills program for Spanish speaking gay and bisexual newcomers. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 20(1), 11–17.

- Asher, S. R., & Wheeler, V. A. (1985). Children’s loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(4), 500–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.500

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

- Beam, C. R., & Collins, E. M. (2019). Trajectories of depressive symptomatology and loneliness in older adult sexual minorities and heterosexual groups. Clinical Gerontologist, 42(2), 172–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1518283

- Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., Wiltink, J., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., Lackner, K. J., & Tibubos, A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

- Busby, D. R., Horwitz, A. G., Zheng, K., Eisenberg, D., Harper, G. W., Albucher, R. C., Roberts, L. W., Coryell, W., Pistorello, J., & King, C. A. (2020). Suicide risk among gender and sexual minority college students: the roles of victimization, discrimination, connectedness, and identity affirmation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 121, 182–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.11.013

- Campaign to End Loneliness. (2015). Measuring your impact on loneliness in later life. https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Loneliness-Measurement-Guidance1.pdf

- Ceatha, N., Mayock, P., Campbell, J., Noone, C., & Browne, K. (2019). The Power of Recognition: A qualitative study of social connectedness and wellbeing through LGBT sporting, creative and social groups in Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193636

- Chaney, M. P. (2008). Muscle dysmorphia, self-esteem, and loneliness among gay and bisexual men. International Journal of Men’s Health, 7(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0702.157

- D’Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A. H., Hershberger, S. L., & O’Connell, T. S. (2001). Aspects of mental health among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Aging & Mental Health, 5(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860120038366

- de Jong Gierveld, J. (1998). Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. Review in Clinical Gerontology, 8, 73–80.

- Deckx, L., van den Akker, M., & Buntinx, F. (2014). Risk factors for loneliness in patients with cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 18(5), 466–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.05.002

- DeLonga, K., Torres, H. L., Kamen, C., Evans, S. N., Lee, S., Koopman, C., & Gore-Felton, C. (2011). Loneliness, internalized homophobia, and compulsive internet use: Factors associated with sexual risk behavior among a sample of adolescent males seeking services at a community LGBT center. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18(2), 61–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2011.581897

- DerSimonian, R., & Laird, N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials, 7(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

- d’Hombres, B., Schnepf, S., Barjakovà, M., & Teixeira, F. (2018). Loneliness—An unequally shared burden in Europe. (Science for Policy Briefs): European Commission. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.2.21745.33128

- Dowshen, N., Binns, H. J., & Garofalo, R. (2009). Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(5), 371–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2008.0256

- Escher, C., Gomez, R., Paulraj, S., Ma, F., Spies-Upton, S., Cummings, C., Brown, L. M., Thomas Tormala, T., & Goldblum, P. (2019). Relations of religion with depression and loneliness in older sexual and gender minority adults. Clinical Gerontologist, 42(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1514341

- Fernández, M. I., Bowen, G. S., Warren, J. C., Ibanez, G. E., Hernandez, N., Harper, G. W., & Prado, G. (2007). Crystal methamphetamine: A source of added sexual risk for Hispanic men who have sex with men? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(2-3), 245–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.016

- Fernández, M. I., Jacobs, R. J., Warren, J. C., Sanchez, J., & Bowen, G. S. (2009). Drug use and Hispanic men who have sex with men in South Florida: Implications for intervention development. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 21(5 Suppl), 45–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.45

- Fish, J., & Weis, C. (2019). All the lonely people, where do they all belong? An interpretive synthesis of loneliness and social support in older lesbian, gay and bisexual communities. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 20(3), 130–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-10-2018-0050

- Fokkema, T., & Kuyper, L. (2009). The relation between social embeddedness and loneliness among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the Netherlands. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(2), 264–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9252-6

- Freedman, A., & Nicolle, J. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness: The new geriatric giants. Approach for primary care. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 66(3), 176–182.

- Garcia, J., Vargas, N., Clark, J. L., Magaña Álvarez, M., Nelons, D. A., & Parker, R. G. (2020). Social isolation and connectedness as determinants of well-being: Global evidence mapping focused on LGBTQ youth. Global Public Health, 15(4), 497–519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1682028

- Garnham, L., & Rolfe, S. (2019). Housing as a social determinant of health: Evidence from the Housing through Social Enterprise study. https://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/7295/Housing_through_social_enterprise_WEB.pdf

- Glass, V. Q., & Few-Demo, A. L. (2013). Complexities of informal social support arrangements for black lesbian couples. Family Relations, 62(5), 714–726. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12036

- Gorczynski, P. F., & Brittain, D. R. (2016). Call to action: The need for an LGBT-focused physical activity research strategy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), 527–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.03.022

- Gorczynski, P., & Fasoli, F. (2020). LGBTQ + focused mental health research strategy in response to COVID-19. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(8), e56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30300-X

- Government Equalities Office. (2018). National LGBT Survey: Research report. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-lgbt-survey-summary-report

- Green, M. (2016). Do the companionship and community networks of older LGBT adults compensate for weaker kinship networks? Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 17(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-07-2015-0032

- Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., & Hershberger, S. L. (2000). Social support networks of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults 60 years of age and older. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(3), P171–P179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.3.P171

- Halkitis, P. N., Cook, S. H., Ristuccia, A., Despotoulis, J., Levy, M. D., Bates, F. C., & Kapadia, F. (2018). Psychometric analysis of the Life Worries Scale for a new generation of sexual minority men: The P18 Cohort Study. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 37(1), 89–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000537

- Hidaka, Y., & Operario, D. (2006). Attempted suicide, psychological health and exposure to harassment among Japanese homosexual, bisexual or other men questioning their sexual orientation recruited via the internet. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(11), 962–967. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.045336

- Higgens, J., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.3 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

- Hoy, D., Brooks, P., Woolf, A., Blyth, F., March, L., Bain, C., Baker, P., Smith, E., & Buchbinder, R. (2012). Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: Modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(9), 934–939. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014

- Hughes, M. (2016). Loneliness and social support among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people aged 50 and over. Ageing and Society, 36(9), 1961–1981. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1500080X

- Hughes, M. (2018). Health and well being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people aged 50 years and over. Australian Health Review: A Publication of the Australian Hospital Association, 42(2), 146–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1071/AH16200

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

- Hyun-Jun, K., & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I. (2016). Living arrangement and loneliness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 548–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu083

- ILGA. (2020). Maps. Sexual orientation laws. https://ilga.org/maps-sexual-orientation-laws

- IOM. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. The National Academies Press.

- Jackson, S. E., Hackett, R. A., Grabovac, I., Smith, L., & Steptoe, A. (2019). Perceived discrimination, health and wellbeing among middle-aged and older lesbian, gay and bisexual people: A prospective study. PloS One, 14(5), e0216497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216497

- Jacobs, R. J., & Kane, M. N. (2012). Correlates of loneliness in midlife and older gay and bisexual men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 24(1), 40–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2012.643217

- Jennings, L., Barcelos, C., McWilliams, C., & Malecki, K. (2019). Inequalities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health and health care access and utilization in Wisconsin. Preventive Medicine Reports, 14, 100864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100864

- Kann, L., Olsen, E. O., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Yamakawa, Y., Brener, N., & Zaza, S. (2016). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9-12 - United States and selected sites, 2015. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC: 2002), 65(9), 1–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1externalicon

- Keenan, K., Wroblewski, K., Matthews, P. A., Hipwell, A. E., & Stepp, S. D. (2018). Differences in childhood body mass index between lesbian/gay and bisexual and heterosexual female adolescents: A follow-back study. PloS One, 13(6), e0196327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196327

- King, A., & Stoneman, P. (2017). Understanding SAFE Housing – putting older LGBT* people’s concerns, preferences and experiences of housing in England in a sociological context. Housing, Care and Support, 20(3), 89–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/HCS-04-2017-0010

- Kneale, D. (2016). Connected communities? LGB older people and their risk of exclusion from decent housing and neighbourhoods. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 17(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-04-2015-0019

- Kuyper, L., & Fokkema, T. (2010). Loneliness among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: The role of minority stress. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(5), 1171–1180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9513-7

- Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

- Martin, J. I., & Knox, J. (1997). Loneliness and sexual risk behavior in gay men. Psychological Reports, 81(3 Pt 1), 815–825. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1997.81.3.815

- Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y., & Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020

- Mereish, E. H., & Poteat, V. P. (2015). A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 425–437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000088

- Miller, G. E., Kemeny, M. E., Taylor, S. E., Cole, S. W., & Visscher, B. R. (1997). Social relationships and immune processes in HIV seropositive gay and bisexual men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 19(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02883331

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Mustanski, B., Newcomb, M. E., & Garofalo, R. (2011). Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: A developmental resiliency perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23(2), 204–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2011.561474

- Nokes, K. M., & Kendrew, J. (1990). Loneliness in veterans with AIDS and its relationship to the development of infections. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 4(4), 271–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9417(90)90042-J

- Operario, D., Smith, C. D., Arnold, E., & Kegeles, S. (2010). The Bruthas Project: Evaluation of a community-based HIV prevention intervention for African American men who have sex with men and women. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 22(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.37

- Pando, M. A., Dolezal, C., Marone, R. O., Barreda, V., Carballo-Dieguez, A., Avila, M. M., & Balán, I. C. (2017). High acceptability of rapid HIV self-testing among a diverse sample of MSM from Buenos Aires, Argentina. PloS One, 12(7), e0180361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180361

- Parsons, J. T., Halkitis, P. N., Wolitski, R. J., & Gómez, C. A, & Study Team, T. S. U. M. S. (2003). Correlates of sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 15(5), 383–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.15.6.383.24043

- Parsons, J. T., Schrimshaw, E. W., Bimbi, D. S., Wolitski, R. J., Gómez, C. A., & Halkitis, P. N. (2005). Consistent, inconsistent, and non-disclosure to casual sexual partners among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS, 19(Supplement 1), S87–S97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000167355.87041.63

- Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and practice (pp 1–17). John Wiley.

- Rew, L., Taylor‐Seehafer, M., Thomas, N. Y., & Yockey, R. D. (2001). Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 33(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x

- Rivers, I., & Noret, N. (2008). Well-being among same-sex- and opposite-sex-attracted youth at school. School Psychology Review, 37(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2008.12087892

- Roth, E. A., Cui, Z., Rich, A., Lachowsky, N., Sereda, P., Card, K., Moore, D., & Hogg, R. (2018). Repeated measures analysis of alcohol patterns among gay and bisexual men in the momentum health study. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(5), 816–827. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1388259

- Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

- Salway, T., Ferlatte, O., Gesink, D., & Lachowsky, N. (2020). Prevalence of exposure to sexual orientation change efforts and associated sociodemographic characteristics and psychosocial health outcomes among Canadian sexual minority men. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(7), 502–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720902629

- Siconolfi, D. E., Halkitis, P. N., Barton, S. C., Kingdon, M. J., Perez-Figueroa, R. E., Arias-Martinez, V., Karpiak, S., & Brennan-Ing, M. (2013). Psychosocial and demographic correlates of drug use in a sample of HIV-positive adults ages 50 and older. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 14(6), 618–627. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0338-6

- Stojanovski, K., Kotevska, B., Milevska, N., Mancheva, P. A., & Bauermeister, J. (2015). “It is one, big loneliness for me”: The influences of politics and society on men who have sex with men and transwomen in Macedonia. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-014-0177-2

- The Centre. (2020). What is LGBTQ? https://gaycenter.org/about/lgbtq/

- Wallace, B. C., Schmid, C. H., Lau, J., & Trikalinos, T. A. (2009). Meta-analyst: Software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-80

- Waite, L. J., Laumann, E. O., Levinson, W., Lindau, S. T., McClintock, M. K., & O’Muircheartaigh, C. A. (2007). A national social life, health, and aging project (NSHAP): Wave 1, July 2005–March 2006. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR20541.v8

- Westefeld, J. S., Maples, M. R., Buford, B., & Taylor, S. (2001). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual college students: The relationship between sexual orientation and depression, loneliness, and suicide. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 15(3), 71–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J035v15n03_06

- Westwood, S., Willis, P., Fish, J., Hafford-Letchfield, T., Semlyen, J., King, A., Beach, B., Almack, K., Kneale, D., Toze, M., & Becares, L. (2020). Older LGBT + health inequalities in the UK: Setting a research agenda. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(5), 408–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-213068

- Wilkens, J. (2015). Loneliness and belongingness in older lesbians: The role of social groups as "community". Journal of Lesbian Studies, 19(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.960295

- Yadegarfard, M., Meinhold-Bergmann, M. E., & Ho, R. (2014). Family rejection, social isolation, and loneliness as predictors of negative health outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, and sexual risk behavior) among Thai male-to-female transgender adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, 11(4), 347–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2014.910483

- Yang, K., & Victor, C. (2011). Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing and Society, 31(8), 1368–1388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1000139X

- Young, J. E. (1982). Loneliness, depression, and cognitive therapy: Theory and application. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 379–406). Wiley-Interscience.