ABSTRACT

Reports worldwide have shown that COVID-19 has impacted vulnerable populations, including homeless populations. The rate of the COVID-19 infection among the homeless populations is still unknown in most countries due to these individuals being scattered inconsistently throughout urban areas; however, surveys have been conducted in some shelters and in areas outside of Japan. Further, psychological impacts associated with COVID-19 infection, such as stress and anxiety or preventive procedures to protect yourself from infection, have also not been well studied among homeless populations. This study analyzes the demographic characteristics of the homeless population, their anxieties about COVID-19, and whether the author’s weekly announcements related to COVID-19 are beneficial to them. A cross-sectional mixed methods study was conducted in a Japanese city from October 2020 to February 2021. Data regarding socio-demographic characteristics, individuals’ experiences of homelessness, and perceptions of COVID-19 were gathered via interviews and examined using quantitative and qualitative methods. 71.1% and 44.2% of the respondents expressed no history of previous diseases and having anxiety due to COVID-19 respectively. Data indicated that they associated COVID-19 with death and serious physical harm. Additionally, 78.6% found the health announcements to be helpful and took preventive measures. Homeless people do not visit doctors, except when experiencing unbearable pain. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously provide comprehensive support for Japan’s homeless population.

KEYWORDS:

Background

COVID-19 has now spread across the globe. Reports have shown that COVID-19 has had a particular impact on vulnerable communities, such as prisoners, nursing home residents, and low-income residents (Tackle coronavirus in vulnerable communities [Editorial], Citation2020, May 19). Both in Japan and abroad, researchers have addressed the need for COVID-19 prevention targeting people experiencing homelessness, as well as the need to provide support for this vulnerable population (Benavides & Nukpezah, Citation2020; Lewer et al., Citation2020).

Homeless people have been identified as a vulnerable population at increased risk for infection because many homeless people experience chronic mental illness and physical ailments (Tsai & Wilson, Citation2020) and face difficulties when attempting to adhere to public health directives (Ralli, Cedola, Urbano, Morrone, & Ercoli, Citation2020). Physical and psychological outcomes of COVID-19 among vulnerable populations are key elements of public health.

Generally speaking, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has had physical and psychological impacts on people from all demographics (Huang & Zhao, Citation2020). An example of one possible psychological effect is that the overload of COVID-19 information may induce further anxiety for some people (Jakovljevic, Bjedov, Jaksic, & Jakovljevic, Citation2020). Further, the economic impacts of COVID-19 have triggered a decline in household income, leading also to a decline in quality of life (Tran et al., Citation2020). As it stands, the physical and psychological statuses of homeless people, considered a vulnerable population, are not well studied in Japan or overseas.

In the United States and Canada, as well as European countries, homeless people live in shelters, on the street, and in train and bus stations depending on their particular circumstances. According to the Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress released by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (The US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Citation2020). In 2019, 567,715 people experienced homelessness on a single night in the United States. On the other hand, the survey by the Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare (MHLW) of 2021 revealed that 3824 homeless people (3510 men, 197 women, and 117 unknown) are living in parks, near rivers, on the street, in train and bus stations, and other locations in Japan (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Citation2021b). This number decreased from its 19,523 totally in 2006 (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Citation2021a). However, the homeless population may be larger than estimated. According to a survey conducted by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government between 2016 and 2017 targeting “people engaged in unstable employment while sleeping at internet cafes or manga cafes,” of the 15,300 users who stay in such establishments overnight, approximately 4,000 people were using them as permanent residences where they sleep each night (Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Citation2018). Domestic workers around the world have been negatively impacted by COVID-19 (International Labor Organization, Citation2020). Likewise, COVID-19 has led to decreased working hours and even termination for some workers in Japan. An unknown number of people may have lost their homes during the coronavirus pandemic as in Japan companies sometimes provide housing for their employees. As a result of that, they became homeless. There are very few homeless shelters in Japan. According to a list of shelters provided by the (MHLW), only two municipalities operates two shelter facilities each in Japan. Beyond this, 51 municipalities operated from 145 locations, such as hotels, instead of formal shelter facilities as of 2014 (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Citation2014). Therefore, the actual number of people without homes in Japan is unknown.

Based on the author’s experience as a medical volunteer serving the homeless population, most homeless people in Japan are among the aging population. Some of them suffer from health problems, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, untreated wounds, and missing teeth. Indeed, many scholars overseas have discussed the health care issues of the homeless populations (Ralli et al., Citation2020; Zlotnick & Zerger, Citation2009). Youth experiencing homelessness are at high risk for experiencing psychiatric disorders (Tucker et al., Citation2020). Although youth homelessness is not a highly visible issue in Japan, according to a report by Nishio et al. (Citation2015), of the 114 homeless individuals surveyed in a city in Japan, 42.1% had been diagnosed with a mental illness.

In the city the author studied, some individuals who had recently lost their house used temporary accommodations provided by the local government. However, many individuals live on the street, near rivers, or in parks. Some homeless people survive partially off of meager pensions, while others collect cans and stickers, or are engaged in irregular employment. Many homeless individuals frequent food kitchens run by nonprofit organizations.

Individuals at homeless shelters have been reported to be at a high risk of contracting COVID-19. In the United States, 36% of people living in homeless shelters in Boston tested positive for COVID-19. In addition, 67% of residents in San Francisco homeless shelters tested positive on a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test (Imbert et al., Citation2020). Japanese homeless people are scattered throughout urban areas and are not clustered in shelters like in other countries, such as the United States, Canada, and some European countries. However, gathering at food kitchens and parks may increase the risk of virus transmission, similar to how restaurants act as hot spots of transmission. In the city selected for this survey, since April 2020, the majority of food kitchens have continued to provide food to the homeless on a weekly basis despite the COVID-19 outbreak. Since these food kitchens provide meals on different days of the week, homeless people are able to receive food somewhere every day. Only a few food kitchens have stopped their services. The author of this study made announcements to prevent COVID-19 infection and created an announcement board called the “Kashiko COVID-19 Fighter Board,” which was posted in an area where homeless people queue to receive food. The information of preventive measurement that were delivered to the participants at the park are as follows;

Learn the appropriate way of wearing masks.

Wash your hands diligently with water using soap.

Be careful when you touch your eyes, nose, or mouth.

The virus might be present on the door knob.

Maintain 2 meters distance when talking to people.

When talking to people, talk sideways, not face-to-face.

Do not touch the surface of the mask.

Although those who visit food kitchens wear masks, it is unknown how much anxiety they experience because of COVID-19 and the risk of being infected. There have been no studies on COVID-19 prevention targeting the homeless population in Japan. Japan has some of the lowest rates of PCR and antibody tests among all OECD countries (OECD, Citation2020). Moreover, the actual number of positive COVID-19 cases in Japan – among the homeless and non-homeless alike – is unknown. During the aforementioned volunteer activities, the author formulated the following research questions:

(1) What are the demographic characteristics of the homeless population? (2) What anxieties do members of the homeless population have about COVID-19? (3) Was the author’s announcement beneficial to homeless people?

Method

Study design

This is a cross-sectional mixed methods study examining both quantitative and qualitative data regarding homeless people’s perceptions of COVID-19. It was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021.

Setting and participants

The sample size was determined based on a G*Power. When the effect size was calculated with use of 0.5, the number of participants was 45. Inclusion in the study was limited to individuals who were homeless and who visited the food kitchen in Park A on Thursday in the city selected for this study. Those who were not homeless, lived in an apartment, and had access to medical assistance were excluded from being participants. Moreover, homeless individuals under the age of 18 were also excluded.

Regular activities of homeless individuals since the outbreak of COVID-19

Every Thursday, the SK organization has been providing food for homeless people and other people in need at Park A in the selected city. Meanwhile, a Life and Health Consultation Team, which belongs to the SS organization, has established an information center in Park A where those in need can receive life and health consultation. The team consisted of volunteer medical workers, including doctors and nurses, as well as other or volunteers without a medical background. Generally, visitors to food kitchens first eat the provided food and then visit the life and health consultation booth to receive consultation or pick up daily necessitiesThe author of this study developed an announcement board called the “Kashiko COVID-19 Fighter Board” based on the graphics depicting infection control and prevention measures developed for Japan (Japanese’s Society for Infection Prevention and Control, Citation2020) and information released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.), Citation2019)). Information included how to put on and take off a face mask, the importance of oral hygiene, hand washing, how to prevent the spread of the virus when coughing, and social distancing guidelines. The author asked the illustrator to create new illustrations or use freely available pictures from the internet. The author printed out these graphics and information on pieces of A4 paper and posted them to the board.

On a separate board, information about not touching one’s eyes and massaging one’s face muscles to promote blood flow was posted. Every Thursday starting from the end of April 2020 up until March 2021, the author made 10-minute announcements based on recent COVID-19 news and information at Park A. She addressed homeless individuals queuing in line to receive free food. The author wore a Pink Ranger costume to get the attention of people standing in line (). The costume also protected the author from being exposed to COVID-19 via aerosol particles. On certain occasions, a dental assistant would provide information on oral care as a method for preventing infection. The author also informed listeners that free masks were available. Beginning in the summer of 2020, the author and other volunteers distributed toothbrushes for infection prevention. Some homeless people asked that the text on the letter board be made larger, and that less Kanji characters be used; therefore, the announcement board was revised four times in order to address such requests.

Procedure

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews that lasted approximately 10 minutes were conducted with 45 homeless people who visited the food kitchen every week between October 2020 and February 2021. People who use the food kitchen include homeless people, people living off meager pensions in apartments, and people with serious medical needs. Therefore, before starting each interview, the author randomly picked up a person who was waiting in the food kitchen area and asked whether or not he or she is homeless. The author randomly picked two to three homeless people to interview each week, and asked them questions based on the interview script. The interview questions focused on anxiety and prevention of COVID-19 infection. Other questions included the respondent’s age, sex, duration of homelessness, the number of visits they make to food kitchens each month, and their history of illness. The interviewer also asked respondents which types of social services provided at the park they felt were most beneficial. Interviewees were also asked about their perception of the announcements given every week by the author, and if there were any other methods that could be used to improve COVID-19 prevention. Finally, the author asked about their quality of life, such as the quality of their meals and sleep.

Data analysis

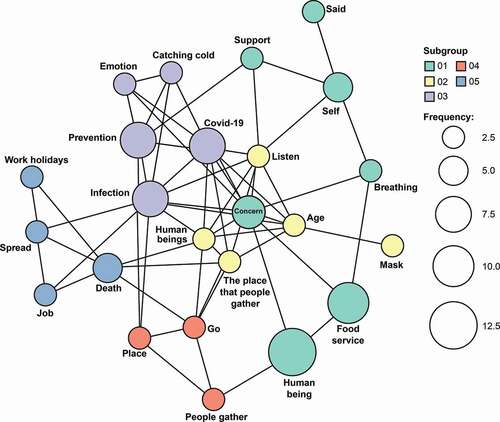

For quantitative analysis, data were analyzed using R studio and SPSS 27. Demographic data and data on perceptions of COVID-19 anxiety and prevention were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For qualitative analysis, the author gathered statements from participants related to COVID-19 and examined text data using KH Coder software, which is a software used for content analysis and text mining. It was developed by Kouichi Higuchi. The network figure captured the frequency of certain statements (). Based on the results of the network figure, the author used theoretical thematic analysis procedures developed by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). They developed those procedures to find and analyze the pattern in the qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; The University of Auckland New Zealand, (Citationn.d.)). The author extracted codes and generated themes.

Results

documents characteristics concerning the eating and sleeping habits of the 45 homeless people who were interviewed. All of the homeless people interviewed were men. Among the 45 respondents, 30 (68.8%) were over 60 years old and 14 (31.2%) were under 60 years old. In addition, 32 out of 45 respondents (71.1%) answered that they had no history of disease and 84.4% felt that they benefited from food services.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics

shows the situation of homeless people surveyed at Park A. The average number of months spent homeless was 78 months. On average, homeless people over 60 had spent a longer time homeless. The average number of times receiving food from a food kitchen was 18 times per month. Younger respondents visited food kitchens more often. In addition, 18 out of 42 respondents (42.9%) felt that their quality of sleep was poor. 19 out of 39 respondents (49%) felt that they were able to eat a sufficient amount of food. represents the perception of COVID-19. A total of 44.2% of participants expressed that they were worried about COVID-19, while 44.2% did not think it became difficult to receive support, and 55.8% did not think COVID-19 caused any trouble. Moreover, 53.3% of respondents answered that they felt no need to receive daily living essentials in order to prevent COVID-19, while others expressed the need for blankets and sleeping bags. A chi-square test revealed that there was no significant association between the ages of participants and their reported levels of anxiety or inconvenience experienced as a result of COVID-19 ().

Table 2. Street life experience, number visits to the food kitchen, and sleep and food conditions

Table 3. Perception of COVID-19

Table 4. Chi-squared for perception of COVID-19

The qualitative data reveals more details concerning the opinions of respondents (). shows that the frequency of words is depicted by the size of the circle. They were anxiety, prevention, infection, death, human beings, and food service. The content of the interviews of the 45 participants on COVID-19 were categorized into the following main topics: infection, concern for daily life, and prevention. COVID-19 infection was further divided into transmission, death, perception of COVID-19, and uncertain future. The category of “concern for one’s daily livelihood due to COVID-19” was divided into food service support, job, and a place to go. The category of “Prevention against COVID-19” included wearing a mask and maintaining social distance. The qualitative data indicates that they were concerned with preventing themselves from contracting the disease and transmitting it to others. According to the perception of COVID-19, respondents felt that being infected with COVID-19 could lead to serious health consequences or death. In total, 33 out of 42 respondents (78.6%) answered that the author’s announcements were helpful. shows that 88.9% wore masks and some of those wore masks to receive food. However, there was no significant association between the benefit of the announcements and the ratio of mask wearing or oral hygiene practice ().

Table 5. Terms from qualitative data about perceptions of COVID-19

Discussion

The mixed methods employed in this study seem to have been effective at identifying the cultural understanding of psychological features (Groleau, Pluye, & Nadeau, Citation2007). By supplementing the qualitative data with quantitative data, this study bolsters the overall validity and credibility of the findings as a whole. These various analysis methods were used to investigate the data related to COVID-19 in the previous literature. Radanliev, De Roure, and Walton (Citation2020) analyzed three topics – mortality, immunity, and vaccination – based on bibliographic data from Web of Science Core Collection with Biliometrix’package. The conceptual map rendered in visual form using R studio clarifies the key elements of these topics. Likewise, the KH coder software used in this study was able to extract the elements of thought of participants, although the data management capacity in KH coder is lower than in R studio.

Previous studies have identified homeless adults as a population at risk of developing chronic health conditions (Aggarwal, Lippi, & Michael, Citation2020). Particularly, cardiovascular diseases have been identified as a high risk disease associated with COVID-19 (Chen et al., Citation2020; Tsai & Wilson, Citation2020). In this study, 71.1% of respondents stated that they had no history of disease. However, 68.8% of respondents were over 60 years old. This finding differs from previous studies. It is assumed that respondents avoided seeing the doctor except when experiencing unbearable pain.

The results of this study did not reveal a statistically significant association between age and anxiety in the context of COVID-19 or feelings of being inconvenienced by COVID-19. This may be because the sample size was too small. However, qualitative data captured the concerns and feelings of inconvenience of respondents. Anxiety may be spurred by various causes. Existing literature from around the world discusses the mental and physical health outcomes associated with COVID-19. Exposure to excessive, conflicting, inaccurate, and/or uncertain health information (Lee et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2021) may be included as a factor in negative mental health outcomes. For example, in the initial stages of the pandemic, the use of face masks was controversial worldwide. The study conducted by Wang et al. (Citation2020) compared the psychological effects of mask recommendations in two countries with differing recommendations. The respondents in the country where masks were not frequently used revealed high rates of anxiety, depression, and stress. In this study, 17 people presented the rationale of wearing masks as a preventive measure. The use of face masks during COVID-19 helps relieve negative psychological effects, which can help both volunteers and homeless individuals feel more comfortable with participating at food kitchens. Masks help reduce physical and mental risks associated with obtaining food and other basic resources or information, although the process of gathering these supplies remains a concern for infection risk.

Anxiety has also been associated with the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A meta-analysis and systematic review focused on 33 countries (Lee et al., Citation2021) revealed that prompt government measures benefited the mental and physical health of people. This study also revealed that Japan has the lowest level of approval of government response to the pandemic among G7 countries (Vardavas et al., Citation2021). Japan’s suicide rate had decreased since 1979 and suddenly rose in 1998 and then slightly decreased (Dhungel, Sugai, & Gilmour, Citation2019); however, the rate remained high among women from July to September 2020 (Nomura et al., Citation2021). In 2020, a government policy was implemented granting 100,000 yen to all residents in the basic resident register of local government offices in Japan. The number of homeless individuals not registered as residents who did not receive these benefits is unknown. However, some local governments have worked to encourage homeless people to receive their benefits by registering as new residents. Further, the number of homeless people in Japan who have received a COVID-19 vaccine is unknown. MHLW has delivered a notice encouraging vaccination to local government offices (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Citation2021c), and some nonprofit organizations (NPOs) who assist homeless populations encourage homeless individuals to get vaccinated by delivering accurate, up-to-date information. The role of NPOs in managing public health should be recognized by government agencies and subsidies should be considered to protect the services they provide.

The fact that 53.3% of respondents stated that there was nothing more that could be done to prevent the spread of COVID-19 indicates that the free food provided to the homeless by several organizations has helped support the livelihoods of the homeless population in Japan. However, some expressed that they need underwear, blankets, and sleeping bags. It is necessary to understand the needs of the homeless regardless of the COVID-19 situation.

The interviews revealed that homeless people possessed basic information of COVID-19 despite not owning a smartphone or TV. Some respondents reported receiving information from acquaintances or the radio. Statements made during interviews also indicated that the announcements made by the author in combination with the announcement board provided homeless people with helpful information that they had not known previously. One respondent stated, “I feel safe when listening to the announcement.” Various alternative therapies exist alongside conventional healthcare. For instance, existing studies have presented alternative therapies with digital humanities tools to deal with the effects of the prolonged COVID-19 lockdown (Radanliev, De Roure, & Walton, Citation2021). Hospital clowns have been known to provide laughter and healing to medical patients worldwide (Adams, Citation2002). A 2016 intervention study supported the association between hospital clowns and positive emotional effects for patients (Auerbach, Ruch, & Fehling, Citation2016). Wearing a costume to deliver COVID-19 information may provide a sense of intimacy and emotional ease to homeless individuals at food kitchens. Further, promoting health while wearing a costume might alleviate the tense atmosphere of gathering during the pandemic.

Although this study was not an intervention study, the announcement was considered effective, as it induced respondents to undertake certain preventive measures, such as wearing a mask, improving their dental hygiene, and carrying disinfectant gel. In particular, respondents were required to wear a mask at the food kitchen, which in turn improved the overall safety at those events.

Although initial data was not obtained before the announcements were commenced, some volunteers indicated that more participants are receiving toothbrushes. Repeated announcements about oral hygiene for the prevention of infection may lead to more homeless people brushing their teeth (n = 11) and using mouthwash (n = 6). Based on my observations as a medical volunteer, it appears that many homeless people do not use toothbrushes and are missing teeth; however, there is no data on this in Japan. Previous studies indicate that oral hygiene has an effect on rates of pneumonia and influenza (Abe et al., Citation2006; Yoneyama et al., Citation2002). Improved awareness of oral hygiene among homeless people may lead to improved infection prevention. The author and supporters requested that participants spray disinfectant gel on their hands while waiting in line, and everyone was cooperative except one or two. Although homeless people live on the street or in parks, they still desire to live, and therefore, they readily accept information and guidance about COVID-19.

Previous studies have examined the impact of outreach on HIV prevention among the homeless and street youth (Gleghorn et al., Citation1997) as well as the effectiveness of interventions by social workers and local governments via screenings and PCR tests for COVID-19 (Benavides & Nukpezah, Citation2020; Wu & Karabanow, Citation2020). However, no studies related to general COVID-19 health education targeting the homeless have been conducted.

Homeless people eat one or two meals per day and often visit food kitchens at night. Food kitchens are run by different organizations and open on different days. The majority of respondents reported getting a poor quality of sleep that lasted no longer than five hours. Studies outside of Japan have shown that COVID-19 can impact mental health, decreasing the quality of sleep and increasing levels of anxiety and depression (Gualano, Lo Moro, Voglino, Bert, & Siliquini, Citation2020; Huang & Zhao, Citation2020; Khan, Mamun, Griffiths, & Ullah, Citation2020). The low quality of sleep reported by homeless people may not be associated with COVID-19. Rather, poor quality of sleep among the homeless may be a result of noisy environment when sleeping outside.

Conclusion

This study prevents quantitative findings complemented by qualitative data. A conceptual map of qualitative data was presented with basic categorization.

The results of this study show that homeless people perceive COVID-19 to be related to death and serious physical harm. They have made efforts to prevent contracting COVID-19. Specifically, wearing masks is required at food kitchens, which are vital to the survival of those who are homeless. The study also revealed that some respondents did not have enough information regarding medical assistance; therefore, continuous support is essential in order to maintain and improve the health of homeless individuals. This can be achieved through the delivery of social services, such as providing free meals and places to sleep. This, in turn, can improve their quality of life and improve prevention of infectious diseases, including COVID-19. This study concludes that the homeless population in Japan must be continually provided with beneficial information about COVID-19.

List of abbreviations

AHAR Annual Homeless Assessment Report

PCR Polymerase chain reaction

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

The Nagoya University Ethics Committee approved this research protocol on Oct 7, 2020 (Approval No. 20,269). All participants provided written informed consent. The informed consent form was written using large, easily legible font.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used during the current study are included in this published article and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Numeric data are also available from Esumi Corporation in Japan.

Author contribution

The author designed the study and interpreted the data by consulting specialists in statistics and data analysis. The author wrote the entire manuscript.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all of the study participants and volunteer staff at the Sasashima Support Center. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Mr. R. Fukushima for his expertise in statistics and MR. S. Okazaki for his expertise in data analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abe, S., Ishihara, K., Adachi, M., Sasaki, H., Tanaka, K., & Okuda, K. (2006). Professional oral care reduces influenza infection in elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 43(2), 157–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2005.10.004

- Adams, P. (2002). Humour and love: The origination of clown therapy. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 78(922), 447–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.78.922.447

- Aggarwal, G., Lippi, G., & Michael, H. B. (2020). Cerebrovascular disease is associated with an increased disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A pooled analysis of published literature. International Journal of Stroke, 15(4), 385–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493020921664

- Auerbach, S., Ruch, W., & Fehling, A. (2016). Positive emotions elicited by clowns and nurses: An experimental study in a hospital setting. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2(1), 14–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000055

- Benavides, A. D., & Nukpezah, J. A. (2020). How local governments are caring for the homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 650–657. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942062

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Interim guidance on unsheltered homelessness and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for homeless service providers and local officials. Retrieved Nov 4, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-shelters/unsheltered-homelessness.html

- Chen, T., Wu, D. I., Chen, H., Yan, W., Yang, D., Chen, G., … Ning, Q. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. The BMJ, 368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1091

- Dhungel, B., Sugai, M. K., & Gilmour, S. (2019). Trends in suicide mortality by method from 1979 to 2016 in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1794. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101794

- Gleghorn, A. A., Clements, K. D., Marx, R., Vittinghoff, E., Lee-Chu, P., & Katz, M. (1997). The impact of intensive outreach on HIV prevention activities of homeless, runaway, and street youth in San Francisco: The AIDS evaluation of street outreach project (AESOP). AIDS and Behavior, 1(4), 261–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026231519630

- Government, T. M. (2018). Results of a survey on the actual situation of unstable workers who lost their address. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://www.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/tosei/hodohappyo/press/2018/01/26/14.html (in Japanese).

- Groleau, D., Pluye, P., & Nadeau, L. (2007). A mix-method approach to the cultural understanding of distress and the non-use of mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 16(6), 731–741. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701496386

- Gualano, M. R., Lo Moro, G., Voglino, G., Bert, F., & Siliquini, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4779. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134779

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

- Imbert, E., Kinley, P. M., Scarborough, A., Cawley, C., Sankaran, M., Cox, S. N., … Fuchs, J. D., & SF COVID-19 Response Team. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in a San Francisco homeless shelter. Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciaa1071. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1071

- International Labor Organization. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on loss of jobs and hours among domestic workers. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, wcms_747961.pdf.

- Jakovljevic, M., Bjedov, S., Jaksic, N., & Jakovljevic, I. (2020). COVID-19 pandemia and public and global mental health from the perspective of global health security. Psychiatria Danubina, 32(1), 6–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2020.6

- Japanese’s Society for Infection Prevention and Control. (2020). Guide to dealing with new coronavirus infections in medical institutions. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from http://www.kankyokansen.org/uploads/uploads/files/jsipc/COVID-19_taioguide2.1.pdf. (in Japanese).

- Khan, K. S., Mamun, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., & Ullah, I. (2020). The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0

- Lee, Y., Lui, L. M. W., Chen-Li, D., Liao, Y., Mansur, R. B., Brietzke, E., … McIntyre, R. S. (2021). Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 290, 364–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.050

- Lewer, D., Braithwaite, I., Bullock, M., Eyre, M. T., White, P. J., Aldridge, R. W., … Hayward, A. C. (2020). COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness in England: A modelling study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(12), 1181–1191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30396-9

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. (2014). Guide to temporary life support business. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12000000-Shakaiengokyoku-Shakai/03_ichiji.pdf (in Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. (2021a). Outline of current homeless measures Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://www.go.jp/shingi/2006/07/dl/s0731-9c.pdf (in Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. (2021b). About the results of a national survey on the actual situation of the homeless. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_17922.html (in Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. (2021c). Securing vaccination opportunities for new coronavirus infections for homeless people. Retrieved Nov 10, 2021, fromhttps://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000804469.pdf (in Japanese).

- Nishio, A., Yamamoto, M., Horita, R., Sado, T., Ueki, H., Watanabe, T., … Shioiri, T. (2015). Prevalence of mental illness, cognitive disability, and their overlap among the homeless in Nagoya, Japan. PLOS ONE, 10(9), e0138052. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138052

- Nomura, S., Kawashima, T., Yoneoka, D., Tanoue, Y., Eguchi, A., Gilmour, S., & Kawamura, Y. (2021). Trends in suicide in Japan by gender during the COVID-19 pandemic, up to September 2020. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113622. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113622

- OECD. (2020). Tackling coronavirus (COVID-19): Contributing to a global effort, Testing for COVID-19: A way to lift confinement restrictions. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://oe.cd/il/2Y0.

- Radanliev, P., De Roure, D., & Walton, R. (2020). Data mining and analysis of scientific research data records on Covid-19 mortality, immunity, and vaccine development - In the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(5), 1121–1132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.063

- Radanliev, P., De Roure, D., & Walton, R. (2021). Alternative mental health therapies in prolonged lockdowns: Narratives from Covid‑19. Health and Technology, 11(5), 1101–1107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-021-00581-3

- Ralli, M., Cedola, C., Urbano, S., Morrone, A., & Ercoli, L. (2020). Homeless persons and migrants in precarious housing conditions and COVID-19 pandemic: Peculiarities and prevention strategies. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 24(18), 9765–9767. doi:https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202009_23071

- Tackle coronavirus in vulnerable communities [Editorial]. (2020, May 19). Nature, 581, 239–240. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01440-3

- The University of Auckland New Zealand. (n.d.). Thematic analysis, a reflexive approach. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/thematic-analysis.html

- The US Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2020). The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved Feb 10, 2021, from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2019-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- Tran, B. X., Nguyen, H. T., Le, H. T., Latkin, C. A., Pham, H. Q., Vu, L. G., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on economic well-being and quality of life of the Vietnamese during the National social distancing. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565153

- Tsai, J., & Wilson, M. (2020). COVID-19: A potential public health problem for homeless populations. The Lancet Public Health, 5(4), e186–e187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30053-0

- Tucker, J. S., D’Amico, E. J., Pedersen, E. R., Garvey, R., Rodriguez, A., & Klein, D. J. (2020). Behavioral health and service usage during the COVID-19 pandemic among emerging adults currently or recently experiencing homelessness. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 603–605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.013

- Vardavas, C., Odani, S., Nikitara, K., El Banhawi, H., Kyriakos, C., Taylor, L., & Becuwe, N. (2021). Public perspective on the governmental response, communication and trust in the governmental decisions in mitigating COVID-19 early in the pandemic across the G7 countries. Preventive Medicine Reports, 21, 101252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101252

- Wang, C., Chudzicka-Czupała, A., Grabowski, D., Pan, R., Adamus, K., Wan, X., … Ho, C. (2020). The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 901. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981

- Wang, C., Chudzicka-Czupała, A., Tee, M. L., Núñez, M. I. L., Tripp, C., Fardin, M. A., … Sears, S. F. (2021). A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85943-7

- Wu, H., & Karabanow, J. (2020). COVID-19 and beyond: Social work interventions for supporting homeless populations. International Social Work, 63(6), 790–794. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820949625

- Yoneyama, T., Yoshida, M., Ohrui, T., Mukaiyama, H., Okamoto, H., Hoshiba, K., … Sasaki, H.; Oral Care Working Group. (2002). Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(3), 430–433.

- Zlotnick, C., & Zerger, S. (2009). Survey findings on characteristics and health status of clients treated by the federally funded (US) health care for the homeless programs. Health & Social Care in the Community, 17(1), 18–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00793.x