Abstract

This article seeks to interrogate the relationship between two gendered aspects of celebrity: the way in which female celebrities are used to determine normative femininity in a postfeminist regulatory environment, and the way their audiences are primarily imagined as young and female. I aim to consider the intersections of this relationship by conducting an analysis of the discursive and affective practices of a feminine digital public where displays of digitally remixed culture are used to enact identity. Consisting of the circulation of self-representative ‘GIF reaction’ blogs authored by young women on blogging social network Tumblr, I analyse how popular young actress Jennifer Lawrence is discursively and affectively sampled and remixed by these bloggers. These blogs match GIF (or .gif) images excerpted from film, television and other popular culture with self-authored captions to construct narratives of youthful femininity documenting feelings and reactions to quotidian situations. I draw together celebrity studies work and the work of feminist scholars of online identity to ask how young women, as subjects who are addressed by celebrity as a vehicle for broader, postfeminist narratives, use Lawrence’s gendered, affective labour in their own identity work in a social, digital environment. Here, the blogs reuse and reconstruct Lawrence’s skilful affective navigation of postfeminist demands and her celebrity signification of carefree and fun authenticity in narrating the bloggers’ own negotiations of femininity.

Introduction: postfeminism, celebrity and digital identity work

Celebrity, as Holmes and Negra (Citation2011) observe, is a highly gendered phenomenon at a number of levels. Within the field of celebrity representation, female celebrities are used to determine what is ‘out of bounds’ for normative femininity in a ‘postfeminist representational environment’ (Citation2011, p. 2). Further, celebrity culture produces and is subject to clearly gendered assumptions in the way that women and girls are ‘its primary imagined audience’ (Citation2011, p. 14). This article aims to interrogate the relationship between these two gendered aspects of celebrity, by exploring the significance of digital culture in extending and making celebrity a ‘remixable’ (Lessig Citation2008) phenomenon. I draw on work in celebrity studies and the work of feminist scholars of online identity to explore how young women, as subjects who are addressed by celebrity as a vehicle for broader, postfeminist narratives, use celebrity as a social function in their own digital identity work. I use the young American actress Jennifer Lawrence as a primary case study to understand how her star image is ‘remixed’ in a set of blogs authored by young women. I suggest that what becomes visible is a double negotiation of postfeminist affective demands on femininity. Lawrence’s own navigation of postfeminist contradictions through the performance of confessional yet humorous feminine authenticity is visibly taken up and reconstructed by the bloggers in narrating their versions of quotidian, feminine experience.

Out of a number of ways in which we might conceptualise celebrity, Turner (Citation2010) argues that, perhaps, most importantly, celebrity can be thought of as a social function. Celebrity, Turner suggests, is a cultural formation which participates in the ‘field of expectations … of everyday life’ particularly held by young people and others (Citation2010, p. 14). In my analysis here, I locate young women as primary actors in this field of expectations in which celebrity participates. Building on the audience work of scholars such as Allen (Citation2011), Cann (Citation2014) and Jackson et al. (Citation2013), I extend this scholarly dialogue to ask how digital DIY identity work by young women can further inform us about the social significance of celebrity. I draw on Hall’s (Citation1996) conceptualisation of identity as ‘suture’, as a temporary point of attachment to subjectivities which discursive practices create, and the celebrity as a significant mode of subjectivity which embodies key ways of ‘behaving, feeling and thinking in contemporary society’ (Dyer Citation2004, p. 15). I use the term ‘identity work’ in this discussion to signal the ongoing way in which young women manage this suture. Here, I take up identity work as a means of analysing how celebrity participates in this quotidian imaginary for young women, and how celebrity may then be reconstructed through this identity work.

I begin by outlining how Tumblr facilitates the production of ‘remix’ culture as a site for the negotiation of celebrity as a social function and digital identity work. While I am not contending that digital engagement with celebrity is new in and of itself, digital cultures demonstrate the reinterpretation and use of celebrity in novel and accessible forms of borrowing, creation and circulation. I suggest that the ‘remix’ visible on Tumblr can be understood as a contemporary means of managing a media-saturated culture, which consistently (re)produces and normalises certain understandings of feminine subjectivity through ‘star images’ (Dyer Citation2004). Although Tumblr still constitutes a power-striated space in which gender, class and race are enacted, Tumblr also provides a space which facilitates ‘rewriting’ media to a certain degree. This leads me to my theoretical framework, which draws on celebrity studies, scholarship of postfeminism and work on digital culture to orient analysis towards the labour performed by young women in negotiating contemporary gender narratives. This framework provides the space within which I explore how Jennifer Lawrence’s form of celebrity authenticity and postfeminist ‘coolness’ (Petersen Citation2014) is taken up, reworked and used by young women, the primary audience-subjects of postfeminist media.

My case study for this discussion is comprised of a set of ‘meme’ GIF reaction blogs on blogging social network Tumblr, which use GIFs excerpting about three seconds of action from film, television and other Internet video clips, matched with situational captions, to construct a self-narrative of everyday experience. The six blogs (the ‘meme set’) are authored by young women who are predominantly undergraduate students in the USA, and include a popular blog entitled #WhatShouldWeCallMe (WSWCM) and five adapted, meme imitations of this blog. I adopt Shifman’s (Citation2013) definition of ‘meme’ as a unit of cultural distribution which can be imitated in content, form and stance, the unit of imitation in this case being the GIF-dominated style of self-narration. GIFs are used to depict lived experience through affective ‘reactions’ to quotidian situations, such as ‘when my boyfriend forgets to tape The Voice’ (frustration), ‘when my best friend eats the last Reese’s buttercup’ (consternation) or ‘when I get assigned a cute lab partner’ (glee). Celebrities often feature in the facial expressions, emotions and quotes in the GIFs, which are mobilised to convey these reactions. I discuss how these meme blogs, in their use of Jennifer Lawrence, can demonstrate the active, discerning and complex ways in which new forms of contemporary feminine subjectivity are collated and assembled to meet the demands of a postfeminist affective and discursive landscape.

My work here is derived from ongoing research on postfeminist digital publics. Having obtained consent from the bloggers to analyse and use their blogs, I have conducted a visual and textual analysis of several hundred blog posts from the meme set. I selected my sample on a chronologically representative basis, including blog posts dating from the earliest days of the blogs beginning in March 2012 through to more recent blog posts published up to June 2014. This article was conceived during data collection when I was struck by the consistent reconstruction of Lawrence’s authenticity across the meme set, although this constitutes only a small portion of the blog posts in my sample. In undertaking this work, I have employed an overarching Foucauldian discursive analytical approach, which is also centrally concerned with Wetherell’s (Citation2012) notion of ‘affective practice’. Accordingly, I analyse how Lawrence’s form of femininity is constituted through the discursive and affective practices which are enacted in the blogs. Analysis based on affective practice ‘focuses on the emotional as it appears in social life and tries to follow what participants do’ (Wetherell Citation2012, p. 4). Such an approach aims not only to understand celebrity through the lens of audience reception, but to expand on the way in which celebrity and audience identity are both enacted and informed through norms of femininity relating to emotion. My attention to both the discursive and affective aspects of the blogs attempts to draw out how the gendered and social nature of affective labour is central to the performance of celebrity and audience feminine identity work. As scholars such as Miller (Citation2008) and Dean (Citation2010) have argued, affect can be understood as a key component of digital communications in spaces such as social network sites, where communication is not necessarily intended to ‘exchange information’ but to express sociability and connection. Second, celebrity involves a high degree of ‘emotion work’ which is demanded as a premise of an ‘ideology of intimacy’ structuring relations between celebrities and audiences (Nunn and Biressi Citation2010). The success of this emotional labour, ‘traded’ (Nunn and Biressi Citation2010, p. 54) for the continued loyalty of fans, turns on the convincing performance of authenticity of the celebrity through acts of confession and disclosure. Notably, Nunn and Biressi draw on Hochschild’s (Citation1983) sociological work, which focuses on the way in which emotional labour fits into broader systems of gendered labour. In Hochschild’s (Citation1983) analysis, working on and adapting one’s emotions to satisfy clients and others can be seen as an extension of women’s work and feminised practices of care.

I use ‘affective’ as a broad term to capture forms of feeling which escape conventional ‘emotional’ coding such as sadness, envy, anger and so on. I note, however, that this parallels with Hochschild’s (Citation1983) use of the term ‘emotional’ and Hesmondhalgh and Baker’s (Citation2011) examination of ‘emotional’ labour in cultural industries. In this way, my use of affect differs from Redmond’s (Citation2014) work, which casts affect as a more bodily sensorial quality in a ‘celebaesthetic’ relationship set up between fans and the ‘carnal figures’ of celebrity. Like Hesmondhalgh and Baker, I focus here on the mobilising, containing and performative labour of the affective practices to hand that demonstrate the way in which emotions are deployed strategically by young women, from stars like Lawrence to the young women bloggers. Here, I particularly examine the performance of humour, accessibility and fun as part of this affective labour and their implication within, and as a response to, the regulatory dynamics of postfeminist identity work. The aim of this affective-discursive analysis, then, is to explore how the affective celebrity work of Jennifer Lawrence is incorporated in young women’s affective, digital identity work to fit within broader systems of gender normativity.

Celebrity, digital remix and Tumblr: rearticulating celebrity

Scholars have explored some parallels between celebrity and postfeminist digital culture in understandings of subjectivity (Dobson Citation2011, Banet-Weiser Citation2012). Keller (Citation2014) argues that an online presence becomes another vital component of media control for the postfeminist celebrity, in individualising their brand in order to maintain a sense of connection and authenticity. Social network sites invite a ‘spectatorial premise’ of DIY authenticity (Dobson Citation2011), similar to the onus on celebrities, particularly female celebrities, to embody authenticity and sincerity in their off-screen lives. Sites of digital self-representation, as Banet-Weiser (Citation2012) notes, also construct governmental spaces that position the self as a commodity, specifically as a self-brand. The ‘interactive subject’ of online social spaces, Banet-Weiser (Citation2012) suggests, is thus invited to follow the neoliberal, postfeminist logics which structure celebrity. Participation in these spaces, accordingly, becomes a way of enacting practices of the self, which emulate celebrity emotional labour.

As Keller (Citation2014) suggests, digital media is an important site for the production of discourses of authenticity, vital to sustaining celebrity image. Celebrity studies scholars have analysed how differing forms of audience–celebrity connection are (re)configured through digital media: through social networks such as Twitter (Marwick and boyd Citation2011, Charlesworth Citation2014); through the digitisation and remix of television into user-generated content (Bennett Citation2011, Burgess Citation2011); and through the dispersal of the celebrity logics of self-presentation in social media more generally (Marshall Citation2006, Citation2010). While scholarship has sought to understand online engagement by fans, particularly with the narratives of favoured books, television and movies (see, for example, Jenkins Citation1992), I suggest that we are yet to fully consider the question of how young women media consumers (who may or may not be considered ‘fans’) reconfigure celebrity in this digitally convergent, postfeminist context. My discussion here takes up celebrity to mean both individual celebrities as texts and celebrity as a mode of subjectivity in ‘enact[ing] ways of making sense of the experience of being a person in a particular kind of social production’ (Dyer Citation2004, p. 15).

Expanding on this work and interrogating these key intersections, I suggest that DIY remix culture online can constitute a means of rewriting media saturated with celebrity narratives. Here, I use the term ‘remix’ (Lessig Citation2008), rather than ‘prosumption’ (Ritzer and Jurgenson Citation2010) or ‘produsage’ (Bruns Citation2008), to highlight the way in which the blogs that I examine sample and appropriate fragments of culture in producing their distinctive forms of narration. As my focus here is a set of blogs on Tumblr, it is important to understand Tumblr as a space where stars as ‘visual, verbal and aural signs’ (Dyer Citation1979) may be rearticulated and circulated. Purchased by Yahoo in May 2013, Tumblr is a popular and fast-growing digital platform, hosting 185 million blogs as of May 2014 and boasting at least 300 million active monthly users (Austin 2013). Tumblr allows users to ‘effortlessly share anything’ – images, text, video – and is notably an image-based rather than text-heavy site (Cho Citation2011). Tumblr operates on the basis that Tumblr bloggers own the content they upload, but provide a licence to other users to share or adapt their content (Tumblr Citation2014). The visual ‘sharing’ ethic of Tumblr thus supports a culture of circulating and adapting the content of other bloggers. Notably, most ordinary (non-celebrity) bloggers use pseudonyms, and as such their ‘real’ identity is not known – but virtually all content on Tumblr is publicly available, via searching Tumblr or by directly entering the URL of the Tumblr. This can be understood as an openness through pseudonymity or anonymity, which creates a certain mobility of circulation of posts, images and ideas (Cho Citation2011).

Accordingly, Tumblr’s features produce a space where celebrity becomes a digital social resource for ‘remix’, through which users process and engage with a world ‘infused with commercial culture’ (Lessig Citation2008, p. 7). This cultural framework, I suggest, is what underpins the success of the original WSWCM blog of this study. The original WSWCM blog boasted 50,000 new Tumblr followers in the month following its creation in early 2012, with independent traffic reports logging the number of page views as one to two million per day (Casserly Citation2012). Not only is each post on WSWCM on average liked and reblogged by up to thousands of other Tumblr users, but arguably the meme set is significant because numerous other bloggers have been demonstrably able to recognise themselves in this novel mode of self-narration put forward by WSWCM. This is demonstrated in the way in which WSWCM has been taken up in a prolific variety of WSWCM-style blogs (the memes) in differing versions of feminine subjectification, such as ‘WhatShouldBetchesCallMe’, ‘WhatShouldWeCallPostgrad’ or ‘WhatShouldPlusSizeCallMe’, which also deal with youthful, feminine self-representational life experiences.

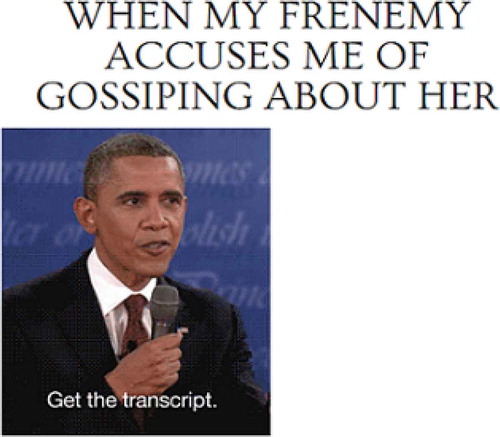

The original WSWCM blog sets out funny and relatable moments in the lives of two ‘best friends’ in GIF (.gif image) reaction posts. What the WSWCM phenomenon is arguably principally known for is the way in which its content, a narration of feminine selfhood, is formatted for the blog audience. It is made up of individual posts, consisting of a heading which outlines a context or situation, and a GIF which acts as the punch line, denoting the action or ‘reaction’ of the blogger. The GIF, which is usually excerpted from online video footage, whether it be film, television or amateur YouTube, captures about three seconds of animation through which this punch line is articulated. The post can then be liked or reblogged, with the number of interactions visible through the ‘notes’ (which are not visible in the screenshots extracting the blog posts in this article). As an example, the screenshot shown in features a blog post, published on 17 October 2013 and accessed on 20 October 2013, which had 568 Tumblr ‘notes’ or interactions, 18 shares through Twitter and 43 ‘likes’ on Facebook (Anon Citation2014a). The heading ‘When my frenemy accuses me of gossiping about her’ sets out the context of the post, a ‘frenemy’ signifying a (usually female) ‘friend’ who is simultaneously an enemy or rival. The GIF then articulates the blogger’s ‘reaction’ to this accusation. The GIF below mobilises the cool gravitas of US celebrity-president Barack Obama to articulate a smooth and level-headed response suggesting that the frenemy check the official, truthful record of what the blogger actually said: ‘Get the transcript’. Obama’s ‘celebrity image’, together with his words, are appropriated to give meaning to an entirely different context from the original setting in which the words were spoken.

Obama’s quote is just one example of the fragments of celebrity and popular culture used in the GIFs to express feelings, responses and reactions by the bloggers. The blogs demonstrate a sophisticated and innovative use of extremely varied situations captured in GIFs, which are appropriated for self-expression. Notably, the GIFs comprise not simply moments of interviews or direct statements of celebrities, but the movements of animals, objects like cars, dialogue in film and television, and parts of YouTube videos. In browsing the blogs, President Obama visually jostles with GIFs of cats from YouTube, the Fresh Prince of Bel Air, animated lizards, Britney Spears and reality television stars, all used to narrate a certain moment in the lives of the bloggers.

Although this may seem chaotic, I suggest that the sheer variety in these GIFs points to a sophisticated level of discernment in their use. In the abundance of GIFs available online, an Obama GIF is not simply selected for use because Obama might be a popular or internationally well-known figure. Rather, the GIF is selected in order to capitalise on, distil and appropriate the meaning that Obama can lend to a particular context. What I suggest becomes visible in this remix is how audiences identify qualities, practices and attributes of public figures and celebrities which resonate because of their wider social meanings. I elaborate further in the next section on the significance of the GIFs featuring Jennifer Lawrence, and how her star image is used as a resource within a set of meanings and practices understandable as part of a postfeminist affective-discursive landscape.

The intersections of postfeminism, celebrity and authenticity

Postfeminism can be understood as a western cultural sensibility in which feminism has been taken into account, so it can now be dismissed as irrelevant (Gill Citation2007). The contradictions posed by this simultaneous incorporation of feminist and anti-feminist narratives are resolved through a strong ‘authentic’ individualism which erases the social/political and the collective from the formation of subjectivity (Gill Citation2007). Accordingly, postfeminism is a sensibility which dovetails with hybrid and mobile neoliberal rationalities (Gill and Scharff Citation2011) that construct and normalise the self-regulating, freely choosing and autonomous subject, without disrupting the privileges of patriarchy. As McRobbie (Citation2009) notes, postfeminist femininity requires young women to come forward as aspiring economic agents, on the condition that feminism is left behind. Young women are to overcome what are cast as the individualised obstacles of race and class through individual ambition, hard work and self-improvement. Youthful femininity, then, can be understood to be intensely governed, where young women are always at risk of making the ‘wrong’ choices and where they only have themselves or their lack of ‘hard work’ to blame for their failures (Harris Citation2004). In a postfeminist representational environment, ambition – together with a (middle-class, hetero)sexuality, and attractive body and appearance – is part of choosing ‘empowerment’ (McRobbie Citation2009). However, one’s feminine identity must be presented as the result of ‘free choice’ and, accordingly, authentic. This individualism arguably requires the marshalling of significant affective labour, to perform an anxiety-free lack of concern regarding social norms, while simultaneously undertaking a disciplinary attitude towards improving aspects of one’s feminine self.

The contemporary female celebrity sits within this landscape of postfeminist contradiction where she is ‘torn’ (Holmes and Negra Citation2011, p. 2) between the double-edged imperative of naturalness and authenticity and of meeting stringent postfeminist standards. Authenticity, in and of itself, as Banet-Weiser (Citation2012) notes, becomes a project to be worked on. Self-disclosure and transparency to others become tools in the postfeminist individual’s mission to access her ‘true self’. Concurrently, the ‘true self’ becomes one’s brand, naturalising the labour one invests as ‘authentic’. Celebrities, to paraphrase Dyer (Citation2004), can be understood as the outcome of labour; however, this labour of constructing a ‘transparent’ self is put under erasure through the ‘individuality’ of the celebrity herself. Further, for women celebrities, the line between being called out as ‘fake’ in investing this labour (Keller Citation2014) and being considered undeserving in not having ‘worked’ for their fame is a thin and precarious one indeed (Holmes and Negra Citation2008, Citation2011, Watkins Fisher Citation2011).

Female celebrities, then, are asked to practise new levels of (affective) labour and self-regulation under increasingly normalised, punitive levels of surveillance enforced by media industries on the purported behalf of media consumers (Allen Citation2011). Accordingly, even while celebrities can be understood as embodying forms of iconic and idealised individuality, postfeminism – not simply as a representational context, but as a context of interactive reception – generates particularly intensified forms of surveillance of female celebrity. This context of interactive reception is visible in entertainment formats such as reality television (Roberts Citation2007, Ringrose and Walkerdine Citation2008, McRobbie Citation2009, Ouellette Citation2009, Tincknell Citation2011, Skeggs and Wood Citation2013) and the tabloid magazine (Holmes and Negra Citation2008), in which audiences are invited to police and evaluate the feminine worth of celebrities and those seeking celebrity. Those who fail to observe the markers of successful postfeminist femininity – slim, white, youthful standards of beauty; the ‘work/life’ balance; or possessing a faithful, heterosexual partner – are offered up for the audience’s disciplinary viewing pleasure (see, for example, Press Citation2011, Watkins Fisher Citation2011, Skeggs and Wood Citation2013). I underline that it is not simply achieving success in these domains but doing it ‘authentically’ that counts. As Keller argues, if female celebrities appear ‘too contrived, artificial, or phony’ then they are subject to public ridicule for ‘not being themselves’ (Citation2014, pp. 160–161). Authenticity thus becomes a valuable and highly managed brand strategy (Banet-Weiser Citation2012, Keller Citation2014).

It is in this space that I position the popularity and star image of young American actress Jennifer Lawrence, whose affective labour positions her as effortlessly authentic and accessible. Jennifer Lawrence is a successful Oscar and Golden Globe-winning actress, well known for her portrayal of determined young (postfeminist) heroines. Her portrayal of tomboy Katniss Everdeen in the successful Hunger Games (Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2014) franchise was possibly one of the defining contributions to this star image. Set in a dystopian future where North America has become ‘Panem’, she and other young people must fight to the death in the ‘Hunger Games’, an Olympic-style reality television contest. Lawrence’s star image is arguably also defined through her acclaimed work in critically lauded films such as Winter’s Bone (Citation2010) and Silver Linings Playbook (Citation2012). Notably, in these films she also plays young women stoically overcoming dark circumstances, often by putting the needs of others before their own (Nadel and Negra Citation2014). However, in her ‘real’ life Lawrence arguably personifies the ‘sunny side’ of fame. As Petersen (Citation2014) writes on pop culture website Buzzfeed, Lawrence is viewed as a ‘refreshingly honest’ celebrity, precisely because her charm appears intrinsically natural and authentic.

This reception may be positioned as part of the historical Hollywood attachment to the ingénue or inexperienced or naïve younger woman as an icon (Sennett Citation1998), designed to both offer possibilities of transformation for young women as well as placate fears about the destabilisation of gender hierarchy. Added to this is arguably Lawrence’s winning screwball authenticity which positions her ‘klutziness’ as ‘real’. Comparing Lawrence at the 2013 Oscars Award ceremony with fellow actress Anne Hathaway, Petersen observes:

Anne Hathaway, who also won an Oscar that night for Best Supporting Actress, is a veritable charm machine. But that’s just it: Hathaway seems like a very talented, very well-programmed machine, while Lawrence seems like a weird, idiosyncratic, charismatic human. (Petersen Citation2014; original emphasis)

Lawrence is well known for trips on the red carpet (humorously taken in her stride), tomboyish activities, such as knocking back champagne at awards ceremonies, and an enthusiasm for food, all while still normatively corresponding to ideals of slim, white, youthful beauty. I suggest that the common use of her nickname ‘JLaw’ in social media and gossip websites demonstrates this sense of her accessibility and ‘best girlfriend’ material: JLaw is funny, likeable and down-to-earth. However, while Lawrence might accordingly be seen as a figure of rebellion, I suggest that this is in virtue of Lawrence’s gendered performance of just-tomboyish enough authenticity through which she meets postfeminist strictures of surveillance and regulation. I now turn to how the blogs have used this signification in demonstrating their creators’ navigation of postfeminist rules of subjectivity.

Sampling Jennifer Lawrence’s ‘realness’

I have suggested that the signification of celebrities on Tumblr is extremely varied. Celebrities feature in the blogs as disconnected images divorced from their original contexts, spliced into the life of the blogger to add meaning to the post. In a pop culture-rich environment, celebrities constitute part of an abundant array of visual resources for bloggers to illustrate or create certain emotions, or depict certain characteristics. The WSWCM meme blogs compress celebrity into forms of shared, distributed data which function as visual representative shortcuts, sourced from other Tumblr users or from the Internet in general. The blogs demonstrate an authorial openness and pragmatism as to who or what they use: celebrities are juxtaposed with YouTube characters, cute animals, or other objects – whatever is required to articulate the emotion expressed by the blogger. In this way the celebrity image, and the narrative in which they are situated, is used and reauthored, and circulated.

In my data sample, Jennifer Lawrence constitutes only one small part of this miscellaneous and abundant celebrity landscape; however, her significance lies in the way her star image, unlike other famous people, is drawn on for its sense of authenticity and normalcy. In 39 out of 43 posts where Lawrence appears in the GIF part of the post, she is featured as herself rather than in her fictional roles, which is notable given that posts usually source GIFs from widely varying pop culture contexts, including film. Lawrence is recurringly featured in ‘candid camera’-type moments, in interviews in talk shows and on the red carpet, rather than extracted from her more explicitly fiction-based performances in film. Arguably, these are the particular moments when Lawrence performs the affective work of her ‘just like us’ celebrity self, which are then circulated in other social media contexts. Further, drawing on Nunn and Biressi’s (Citation2010) analysis of one-to-one celebrity interviews as spectatorial sites of ‘authenticity’, this suggests that Lawrence is primarily seen for her characteristics as a ‘real’ young woman, rather than an actress. Other actors who feature in GIFs are generally spliced from moments of a film or television show in which they star. Rachel McAdams, for example, also features a number of times across the meme set, but usually in her role as Queen Bee Regina George from the movie Mean Girls (Citation2004), or as the lead role in romantic drama The Notebook (Citation2004). The use of Jennifer Lawrence in this way mirrors how reality television stars such as Kim Kardashian, Alana Thompson (Honey Boo Boo) and Lauren Conrad are captured in GIFs; being ‘themselves’, or talking directly to the camera about how they feel. However, in contrast to reality television stars, who are often questioned as to ‘how real’ they might be (Holmes Citation2006), I suggest that, as a film star, Lawrence benefits from a distinction between her ‘acting work’ and ‘being herself’. Thus, ‘artifice’ can be bounded in her work in film, rather than being perceived as spilling into her more quotidian performances of the self.

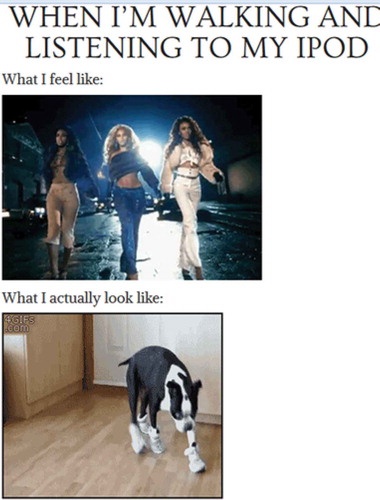

The way in which Lawrence is seen to ‘be herself’ rather than the shadowy figure of ‘someone else’ is visible in the way the GIFs in which she features are mobilised by the bloggers. I suggest that these GIFs are selected for their ‘naturalness’. GIF reaction posts often utilise prominent female celebrities for humour to set up a dichotomy between the blogger’s expectation and the blogger’s ‘reality’. For example, a post for the situation ‘when I’m walking and listening to my iPod’ () contrasts what the blogger feels like to what they ‘actually look like’ (Anon Citation2014a).

The first GIF features the late 1990s R’n’B group Destiny’s Child, embodying an ‘empowered’ sexual attractiveness in strutting confidently down a street. This forms the ‘expectation’ or aspiration: ‘What I feel like’. This is compared with the second GIF of the blogger’s reality: ‘What I look like’. This GIF represents the blogger’s ‘real-life’ movements as those of a loping, awkward dog, who is contrasted humorously, if slightly cruelly, to the desirable fluidity of the movements of the successful pop stars in the first GIF.

Jennifer Lawrence, by way of contrast, usually embodies what is meant to be conveyed as the ‘actual’ experience of the blogger, rather than the blogger’s ‘expectation’. This is interesting, given that in some ways Lawrence could be considered an aspirational rather than relatable figure. As a young woman who has not only won an Oscar at a relatively young age, but who also corresponds to postfeminist strictures of appearance, Lawrence’s successful femininity may be considered ‘unachievable’ for many. Notwithstanding this, Lawrence’s understood persona as a ‘normal’ young woman appears to be the dominant way in which she is reconstructed in the blogs, and used as a means of relating everyday experiences. What is notable, then, is the way in which Lawrence both uses and successfully erases the affective labour of normative femininity. Her ‘authenticity’, performed through an open confessional style, narration of humorous, self-deprecating anecdotes and laidback demeanour effaces the affective labour of managing a desirable feminine persona.

In the blog posts that follow, I extract exemplars of the way Jennifer Lawrence’s star image is ventriloquised by the bloggers. I suggest that this occurs in two main ways: Lawrence is used for her ability to manage postfeminist governmental strictures through self-deprecating, confessional humour; and in her fun, feminine accessibility as ‘BFF’ (best friend forever). Accordingly, Lawrence is arguably constructed in the blogs as an authentic vehicle through which feminine, youthful experiences can be articulated, particularly when one is understood to diverge from a life script. This script, I argue, is constituted of implicit (and sometimes explicit) postfeminist rules regulating contemporary feminine subjectivity, of which the blogs appear to demonstrate a heightened awareness.

Jennifer Lawrence’s affective labour and the funny, self-deprecating postfeminist subject

One key way Jennifer Lawrence is used in the blogs is as a means of engaging with governmental postfeminist requirements that young women should be productive, strategic and industrious citizens (Harris Citation2004, McRobbie Citation2009). Young women must be seen to be economically productive, in terms of paid work, and also in investing in the self, as a brand (Banet-Weiser Citation2012). Notably, this labour on the self must often take the form of ‘care’ or work on the body, which is seen as synecdochal for the fitness of the self brand overall (Gill Citation2007, Ringrose and Walkerdine Citation2008, Tincknell Citation2011). I suggest that in the blogs Lawrence signals the right amount of transgressive potential in navigating this requirement demanded of young women across professional and personal domains of life. However, I argue that it is Lawrence’s very ability to navigate the ‘feeling rules’ (Hochschild Citation1983) of postfeminist subjectivity through her charm and humour that allows certain forms of transgression to be enactable.

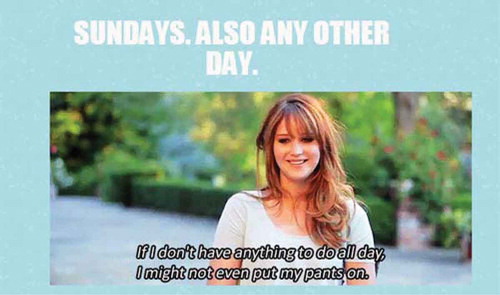

The blogs in the meme set often speak back to postfeminist demands of productivity, by overtly celebrating idleness and rest. However, this idleness, while mildly rebellious, is often produced in a socially sanctioned form. For example, on one of the blogs a post constructs what happens on ‘Sundays. Also any other day’ (Anon Citation2014b). The situation is articulated by Lawrence, laughing charmingly in what appears to be an interview: clouds of blonde hair frame her face as she states ‘if I don’t have anything to do all day, I might not even put my pants on’ ().

Why, one might ask, is it significant that in one’s own time, one does not get dressed? This, perhaps, suggests the intensity with which youthful femininity is governed. One’s leisure time, as a young woman, must still be productive. Jennifer Lawrence’s endearing, humorous and seemingly natural confession about breaking the rules, then, becomes a way of managing transgression in an acceptable way. One may rebel, then, if one can mobilise one’s affective resources and laugh while confessing one’s derogations from the norm. The phrasing of ‘Also, any other day’ as an afterthought both reconstructs the status of Sunday as a normative day for leisure, and the rebelliousness of the blogging subject in adopting a less than productive attitude. ‘Any other day’ extends the days on which idleness may be celebrated and indulged in, on the proviso that one does not ‘have anything to do’. This rebellion is performed through a feminine conspiratorial whisper, acknowledging a certain legitimacy of the affective-discursive rules governing feminine self-monitoring, appearance and industriousness, while at the same time putting them into question.

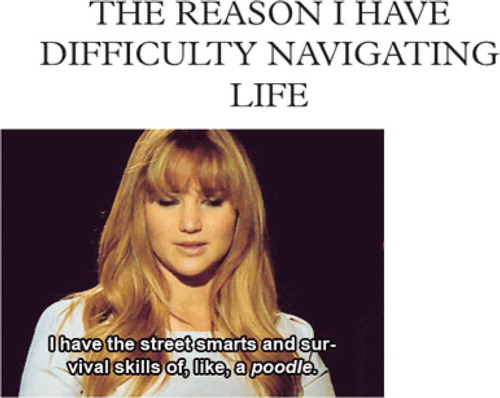

On another blog, Lawrence is used to articulate ‘The reason I have difficulty navigating life’ (Anon Citation2013). The ‘difficulty in navigating life’ arguably speaks to the ways in which young women are constructed as always at risk of making the ‘wrong choices’ (Negra Citation2008, McRobbie Citation2009), yet at the same time are enjoined to be ambitious, calculating, individual citizens (Harris Citation2004, Gonick Citation2006). Another paradox at the heart of this articulation is arguably what McRobbie (Citation2009) has identified as the imperative for young women to embody empowerment, yet at the same time to apologise for it. Although it is increasingly compulsory for women to succeed in their life plans (McRobbie Citation2009), they must do so becomingly. In the way that Bridget Jones skittishly and girlishly makes blunders, records them and engages in humorous, disciplinary self-talk, young women must acknowledge their weaknesses in managing this call to always make the right choices. Here, Lawrence’s self-deprecating humour is marshalled for this purpose. Seated, speaking to an off-camera interviewer, Lawrence’s eyes are demurely downcast when she begins saying ‘I have the street smarts and survival skills of a … poodle’, looking up when she finishes her phrase. Lawrence, in confessing her lack of ‘street smarts’ that the postfeminist top girl ostensibly possesses, is used by the blogger to smoothly perform the suture between the acknowledged imperative to ‘navigate life’ with the feminine self-deprecation simultaneously required of young women ().

Sexuality is another key, regulative element of postfeminist subjectivity, which one must demonstrate through enacting an abundant, active, desiring heterosexuality (McRobbie Citation2009, Ringrose and Barajas Citation2011). However, as McRobbie (Citation2007) notes, usually this desire is only speakable under the raced and classed conditions of the postfeminist sexual contract. One of the blogs features Lawrence in the scenario to navigate the somewhat fantastical scenario of ‘when I turn up to a party full of really hot, wet and shirtless lifeguards’ (Anon Citation2013). While the heading evokes heterosexual desire in an almost comical way, the blog channels a tactical self-deprecation in the ‘reaction’ to this situation: ‘I’m not cool enough to be at this party’, Lawrence states matter-of-factly in what appears to be a late-night talk-show setting ().

Figure 5. ‘When I show up to a party full of really hot wet and shirtless lifeguards.’ Two Dumb Girls, 2 September 2014.

Yet, as Petersen (Citation2014) argues, Lawrence is a ‘cool girl’ in her ability to seamlessly perform an accessible and (heterosexually) desirable femininity while making it appear natural. The ‘cool girl’ Petersen cites is derived from the book Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn (Citation2012); rather than connoting exclusivity, which is suggested by Lawrence’s quote, this ‘cool girl’ embodies a mix of qualities which placate fears about feminine excess and dominance. The Cool Girl is idealised in a masculine world; she is heterosexually attractive, but she is ‘laidback’; she is not ‘needy’; she is tomboyishly funny but not excessively assertive. Self-deprecating humour can be seen to be one affective strategy of performing the Cool Girl. Accordingly, Lawrence’s disavowal of ‘coolness’ might also be seen as a part of her winning unaffectedness, which strategically underplays her star power. This blog post similarly avows a failing: ‘I’m not “cool” enough to be at this party’, undercutting the suggestion of an active, desiring postfeminist sexuality which is invoked by the construction of ‘really hot’, ‘shirtless’ lifeguards. Thus, the blogger manages to have it both ways: demonstrating postfeminist possession of active heterosexual desire through the citation of masculine bodies conventionally recognisable as ‘hot’, and at the same time as exhibiting a feminine, middle-class sense of restraint and inadequacy.

These posts demonstrate the way in which the subjectivities of empowered young women which dominate consumer advertising culture must in fact be managed through softer, pleasing and confessional forms of femininity in performing the everyday in post-girl power culture (Riordan Citation2001). It could be argued that the choice of Jennifer Lawrence as a vehicle for this rebellion, then, is fitting, as a figure that is able to flout conventional rules of femininity relating to elegance, moderation and control. Ultimately, however, I argue she is able to flout these rules through a charming and humorous girlishness, practised through a body which is youthful, white and coded as heterosexually attractive. These posts simultaneously invite judgment through the confession of weakness but undercut possible disciplinary viewing in virtue of its humorous, girlish avowal. This self-deprecating, confessional form of humour as affective labour serves to demonstrate important postfeminist qualities: first, one’s authenticity, as one distances oneself from the feminine artifice of being ‘perfect’ and ‘polished’; and second, that one is ‘fun’ and ‘up for it’ because one does not take life ‘too seriously’. Through this form of humour, one may point to one’s problems (or indeed, produce them) in a way that minimises the emotional labour required of others; indeed, in a way that performs accessibility for others. In gendered terms, it points to increased work for young women, on themselves, to perform a pleasing form of feminine individuality suitable for a postfeminist system in which young women must not go beyond the ‘licensed trangression’ (McRobbie Citation2007) afforded to them.

Jennifer Lawrence as safe and fun girlfriend material

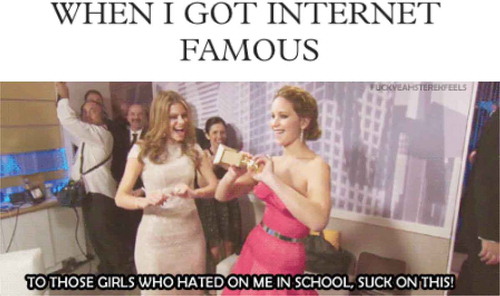

I suggest that a final, key aspect of Jennifer Lawrence’s star image taken up by the blogs is the sense of her accessibility, which is bound up in the way her A-list star status is invoked yet downplayed. Indeed, this is a vital part of Lawrence’s authenticity, which plays into the way her femininity is coded as both sociable but also highly individual. This construction of Lawrence can be seen in the manner in which her dancing with a Golden Globe, a symbol of triumph, is appropriated by one of the bloggers in the situation ‘When I got Internet Famous’ (famous on the Internet) (Anon Citation2014c). In the GIF, Lawrence joyfully dances with Maria Menounos, an American TV host, holding the trophy horizontally with both hands as a dance prop. In the boyishness and exuberance of her movements, Lawrence escapes being captured by the conventional coding of sexy/feminine which overdetermines the dancing of young women, although she is dressed in a form-fitting pink dress. The GIF caption, which is usually a quote from the person featured in the GIF, states: ‘To those girls who hated on me in school, suck on this!’ Lawrence is captured in a moment where she simultaneously successfully differentiates herself from feminine rivals, yet exudes a ‘girlfriendliness’. Although Lawrence has spoken about fraternising with boys rather than girls as a child (Petersen Citation2014), in this instance the quote is not from Lawrence. The caption was perhaps added by the blogger, or the original creator of the GIF.

I suggest that this is significant, precisely because these words, despite not being a specific quote from Lawrence, are imaginable as attributable to her and thus part of her star image. This phrase suggests a type of ‘revenge’ against presumably hostile feminine Others, and through the comical movements of Lawrence’s body the GIF articulates a pleasure in achievement despite the wishes of numerous unknown feminine rivals. The blogger’s reaction to ‘when [she] got Internet Famous’ thus draws on this gleeful retribution to celebrate her own individual, deserving success in attaining Internet popularity. Her triumph is enacted through a merry hostility towards the ‘girls’ of high school embodying feminine, disciplinary pettiness. Maria Menounos’ body becomes ‘girlfriended’ in the process of this dancing with Lawrence, softening the otherwise harsh tone of Lawrence’s imaginary insult to these spectral Mean Girls. Lawrence’s attractive tomboyishness provides a space where a particular type of femininity can be expelled as one one’s ‘constitutive limit’ (Skeggs and Wood Citation2013), all while being fun and safe ().

As Winch (Citation2013) argues, in postfeminist girlfriend culture men are rendered ultimately banal in feminine suffering; one must look out for the treacherous wiles of other young women. The way in which Lawrence’s body is captured in this GIF shows that she is understood to seamlessly walk the line between being a ‘man’s woman’ and a ‘girl’s girl’. As a strong, individual young woman she willingly criticises Other Girls, speaking out against their disciplinary regulatory behaviour. However, importantly, one must know to deliver this critique with humour. Postfeminist subjects might be ‘fierce’ (Keller Citation2014) and ‘autonomous’ (Dobson Citation2012); but the payoff for this is that they must not be emotionally excessive, lapsing into ‘bitterness’ or feminine ‘meanness’.

I contend that celebrity identity work parallels these postfeminist demands by requiring a strategic performance and containment of the kinds of emotional labour Nunn and Biressi (Citation2010) and Hesmondhalgh and Baker (Citation2011) discuss. Lawrence can thus be used to speak a form of resistance without transgressing the entrenched boundaries of gender relations. She is not ‘angry’ or ‘shrewish’; while being selectively boyish, she does not critique the privilege of men. Moreover, her purported weaknesses are confessed through knowing humour; they are strategically used to demonstrate authenticity. Lawrence’s star signification, hence, is spliced into affective fragments that are construed as adaptable, useful and ultimately safe in the practice of everyday feminine identity for these young women bloggers. In navigating the contradictory rules of postfeminist subjectivity, Lawrence can perform the suture whereby one can articulate one’s individuality, while still adhering to key markers and boundaries of femininity.

Implications and further questions

I suggest that the discussed meme set demonstrates that the late modern call to young women’s ‘empowerment’ and ‘self-expression’ (Budgeon Citation2011) thus cannot always be straightforwardly adopted as a mode of subjectivity to which young women might attach. However, it also demonstrates that dominant modes of subjective transgression which are available for young women still involve affective practices that reproduce postfeminist dynamics where women are enjoined to work on themselves. Particularly, it shows how self-deprecating, confessional humour and the performance of a fun and carefree persona can constitute forms of strategic affective labour which render one’s feminine self more accessible, authentic and ‘cool’ for others. Accordingly, a girl-subject like Jennifer Lawrence, who is able to straddle postfeminist contradictions through humorously avowing weaknesses, blunders and boyish qualities, may be considered more accessible and adaptable. What is visible on the blogs is a highly discerning use of Lawrence’s ability to walk an ever-precarious line in performing contemporary femininity. The affects and narratives constituting Lawrence in these distilled GIF forms are ably put to use in a wide variety of everyday situations. Celebrity here, then, becomes a social resource used to navigate these postfeminist rules governing quotidian situations. These blogs demonstrate nuanced recognition of postfeminist affective demands on femininity in ways that can deepen scholarly understanding of the minute, intimate negotiations which constitute contemporary femininity.

Approaching celebrity as I have done here manifests how the interrogation of digital DIY artefacts can provide an account of how audiences expand the signification and significance of celebrity. I have sought to use data which chronicle the self-representational everyday experience of young women as a springboard for understanding the signification and significance of Jennifer Lawrence. This orientation towards the quotidian in the narratives of femininity I have analysed provides a grounded account of how celebrity, both as a form of discourse and as a social function, is used day to day. Yet the very ordinariness of the data I have used also raises questions about how remix culture remakes ideas of accessibility and use-ability. While the blog posts featuring Lawrence here are fairly benign, what are the social implications of a digital culture where both celebrity and non-celebrity bodies are made ever more accessible, and shareable as data? What might be the ‘social life’ (Beer and Burrows Citation2013) of these data, in its reconfiguration of the accessibility of feminine celebrity? How might norms of young women’s visibility and accessibility impact on the meaning of celebrity, and vice versa? Indeed, for young women, and for Jennifer Lawrence and other female celebrities whose personal photos were recently stolen and distributed online, these may be recurring concerns.

Understanding celebrity as a type of social function implies a set of social relations not simply between audience and celebrity, but within and between audiences: what elements of a celebrity image, emotional labour or self-work are available to be used as a social function, by whom and why? This discussion has attempted to extend feminist scholarship at the intersections of postfeminist digital culture, celebrity and identity (see Allen Citation2011, Banet-Weiser Citation2012, Dobson Citation2012, Jackson et al. Citation2013, Keller Citation2014, Redmond Citation2014) by exploring the complexity and depth of the affective and discursive practices of audiences. Strongly represented as it is by cultural studies scholars, the field of celebrity studies has often used discursive and textual analysis to understand celebrities as media texts (Turner Citation2010). My approach here has been to take a discursive approach, but also to ground this analysis with a concept of affective practice which draws on sociological concerns with labour. Such an interpretation of affect orients analytical attention to the negotiated practices of participants, as well as the signification of discourse. This discussion has mobilised an understanding of the everyday gendered labour of both audiences and celebrity in order to situate the audience remaking of Jennifer Lawrence. By asking how the gendered labour of female celebrity correlates with the affective practices of audiences, I hope that this approach contributes to the renewed interest in audience-oriented and digital celebrity studies scholarship. While deceptively simple in appearance, digital DIY remix, I suggest, can say much about gendered, raced and classed assumptions underpinning the everyday experience of audiences, as well as their reception and use of celebrity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Akane Kanai

Akane Kanai is a PhD candidate at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. Her research interests include postfeminism, race, class and feminine sociality in digital media. She has published in M/C – A Journal of Media and Culture and has contributed a chapter to eGirls, eCitizens (University of Ottawa Press, 2015).

References

- Allen, K., 2011. Girls imagining careers in the limelight: social class, gender and fantasies of ‘success’. In: S. Holmes and D. Negra, eds. In the limelight and under the microscope: forms and functions of female celebrity. New York: Continuum, 149–173.

- Anon, 2013. TwoDumbGirls [online]. Available from: http://twodumbgirls.tumblr.com/ [Accessed 2 November 2014].

- Anon, 2014a. WhatShouldWeCallMe [online]. Available from: http://whatshouldwecallme.tumblr.com/ [Accessed 20 October 2014].

- Anon, 2014b. 2ndhandembarrassment [online]. Available from: http://2ndhand-embarrassment.tumblr.com/ [Accessed 2 November 2014].

- Anon, 2014c. WhatShouldBetchesCallMe [online]. Available from: http://whatshouldbetchescallme.tumblr.com/ [Accessed 20 October 2014].

- Banet-Weiser, S., 2012. AuthenticTM: the politics of ambivalence in a brand culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Beer, D. and Burrows, R., 2013. Popular culture, digital archives and the new social life of data. Theory, Culture & Society, 30 (4), 47–71.

- Bennett, J., 2011. Architectures of participation: fame, television and Web 2.0. In: J. Bennett and N. Strange, eds. Television as digital media. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 332–357.

- Bruns, A., 2008. Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: from production to produsage. New York: Peter Lang.

- Budgeon, S., 2011. The contradictions of successful femininity: third-wave feminism, feminism, postfeminism and ‘new identities’. In: R. Gill and C. Scharff, eds New femininities: postfeminism,neoliberalism and subjectivity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burgess, J., 2011. User-created content and everyday cultural practice: lessons from YouTube. In: J. Bennett and N. Strange, eds. Television as digital media. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Cann, V., 2014. The limits of masculinity: boys, taste and cultural consumption. In: S.K. Roberts, ed. Debating modern masculinities: change, continuity, crisis? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 17–34.

- Casserly, M., 2012. #WhatShouldWeCallMe revealed: the 24-year old law students behind the new Tumblr darling. [online]. Available from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/meghancasserly/2012/03/29/whatshouldwecallme-revealed-24-year-old-law-students-tumblr-darling/ [Accessed 31 January 2013].

- Charlesworth, D., 2014. Performing celebrity motherhood on Twitter: courting homage and (momentary) disaster – the case of Peaches Geldof. Celebrity Studies, 5 (4), 508–510.

- Cho, A., 2011. Queer Tumblrs, networked counterpublics. In: Conference papers – International Communication Association, 1–37.

- Dean, J., 2010. Blog theory: feedback and capture in the circuits of drive. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dobson, A.S., 2012. ‘Individuality is everything’: ‘autonomous’ femininity in MySpace mottos and self-descriptions. Continuum, 26 (3), 371–383.

- Dobson, A.S., 2011. Hetero-sexy representation by young women on MySpace: the politics of performing an ‘objectified’ self. Outskirts [online], 25. Available from: http://www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.au/volumes/volume-25/amy-shields-dobson [Accessed 19 March 2013].

- Dyer, R., 1979. Stars. London: British Film Institute.

- Dyer, R., 2004. Heavenly bodies: film stars and society. London: Routledge.

- Flynn, G., 2012. Gone girl. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Gill, R., 2007. Gender and the media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gill, R. and Scharff, C., 2011. Introduction. In: R. Gill and C. Scharff, eds. New femininities: postfeminism, neoliberalism and subjectivity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–17.

- Gonick, M., 2006. Between ‘Girl Power’ and ‘Reviving Ophelia’: constituting the neoliberal girl subject. NWSA Journal, 18 (2), 1–22.

- Hall, S., 1996. Who needs identity?. In: S. Hall and P. Du Gay, eds Questions of cultural identity. London: Sage, 1–17.

- Harris, A., 2004. Future girl: young women in the twenty-first century. London: Routledge.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. and Baker, S., 2011. Creative labour: media work in three cultural industries. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hochschild, A., 1983. The managed heart: the commercialisation of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Holmes, S., 2006. When will I be famous? Reappraising the debate about fame in reality TV. In: D.S. Escoffery, ed. How real is reality TV: essays on representation and truth. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland & Company, 7–25.

- Holmes, S. and Negra, D., 2011. Introduction: in the limelight and under the microscope – the forms and functions of female celebrity. In: S. Holmes and D. Negra, eds. In the limelight and under the microscope: forms and functions of female celebrity. New York: Continuum, 1–16.

- Holmes, S. and Negra, D., 2008. Introduction. Genders [online] (48). Available from: http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE|A194279236&v=2.1&u=monash&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=03e0b87ae5c4c94a12e2805635fc7e4a# [Accessed 9 July 2014].

- Jackson, S., Vares, T., and Gill, R., 2013. ‘The whole playboy mansion image’: girls’ fashioning and fashioned selves within a postfeminist culture. Feminism & Psychology, 23 (2), 143–162.

- Jenkins, H., 1992. Textual poachers: television fans and participatory culture. New York: Routledge.

- Keller, J.M., 2014. Fiercely real? Tyra Banks and the making of new media celebrity. Feminist Media Studies, 14 (1), 147–164.

- Lessig, L., 2008. Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. New York: The Penguin Press.

- Marshall, P.D., 2006. New media – new self. In: P.D. Marshall, ed. The celebrity culture reader. New York: Routledge, 634–644.

- Marshall, P.D., 2010. The promotion and presentation of the self: celebrity as marker of presentational media. Celebrity Studies, 1 (1), 35–48.

- Marwick, A. and boyd, d., 2011. To see and be seen: celebrity practice on Twitter. Convergence: the International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 17 (2), 139–158.

- Mean girls, 2004. Film. Directed by Mark Waters. USA: SNL Studios.

- McRobbie, A., 2007. Top girls? Young women and the post-feminist sexual contract. Cultural Studies, 21 (4–5), 718–737.

- McRobbie, A., 2009. The aftermath of feminism: gender, culture and social change. London: Sage.

- Miller, V., 2008. New media, networking and phatic culture. Convergence: the International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14 (4), 387–400.

- Nadel, A. and Negra, D., 2014. Neoliberalism, magical thinking, and. Silver Linings Playbook. Narrative, 22 (3), 312–332.

- Negra, D., 2008. What a girl wants? Fantasising the reclamation of self in postfeminism. London: Routledge.

- Nunn, H. and Biressi, A., 2010. ‘A trust betrayed’: celebrity and the work of emotion. Celebrity Studies, 1 (1), 49–64.

- Ouellette, L., 2009. Take responsibility for yourself: Judge Judy and the neoliberal citizen. In: S. Murray and L. Ouellette, eds. Reality TV: remaking television culture. New York: New York University Press, 223–242.

- Petersen, A.H., 2014. Jennifer Lawrence and the history of cool girls [online]. Buzzfeed. Available from: http://www.buzzfeed.com/annehelenpetersen/jennifer-lawrence-and-the-history-of-cool-girls [Accessed 12 March 2014].

- Press, A.L., 2011. ‘Feminism? That’s so seventies’: girls and young women discuss femininity and feminism in America’s next top model. In: R. Gill and C. Scharff, eds. New femininities: postfeminism,neoliberalism and subjectivity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 117–133.

- Redmond, S., 2014. Celebrity and the media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ringrose, J. and Barajas, K.E., 2011. Gendered risks and opportunities? Exploring teen girls’ digitized sexual identities in postfeminist media contexts. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 7 (2), 121–138.

- Ringrose, J. and Walkerdine, V., 2008. Regulating the abject: the TV make-over as site of neo-liberal reinvention toward bourgeois femininity. Feminist Media Studies, 8 (3), 227–246.

- Riordan, E., 2001. Commodified agents and empowered girls consuming and producing feminism. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 25 (3), 279–297.

- Ritzer, G. and Jurgenson, N., 2010. Production, consumption, prosumption: the nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10 (1), 13–36.

- Roberts, M., 2007. The fashion police: Governing the self in What not to wear. In: Y. Tasker and D. Negra, eds. Interrogating postfeminism: gender and the politics of popular culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 227–248.

- Sennett, R., 1998. Hollywood hoopla: creating stars and selling movies in the golden age of Hollywood. New York: Billboard Books.

- Shifman, L., 2013. Memes in a digital world: reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18 (3), 362–377.

- Silver linings playbook, 2012. Film. Directed by David O. Russell. USA: The Weinstein Company and Mirage Enterprises.

- Skeggs, B. and Wood, H., 2013. Reacting to reality television: performance, audience and value. Abingdon: Routledge.

- The hunger games, 2012. Film. Directed by Gary Ross. USA: Color Force.

- The hunger games: Catching fire, 2013. Film. Directed by Francis Lawrence. USA: Color Force.

- The hunger games: Mockingjay part 1, 2014. Film. Directed by Francis Lawrence. USA: Color Force.

- The notebook, 2004. Film. Directed by Nick Cassavetes. USA: Avery Pix.

- Tincknell, E., 2011. Scourging the abject body: Ten years younger and fragmented femininity under neoliberalism. In: R. Gill and C. Scharff, eds. New femininities: postfeminism,neoliberalism and subjectivity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 83–95.

- Tumblr, 2014. Terms of service [online]. Available from: https://www.tumblr.com/policy/en/terms-of-service [Accessed 20 January 2015].

- Turner, G., 2010. Approaching celebrity studies. Celebrity Studies, 1 (1), 11–20.

- Watkins Fisher, A., 2011. We love this trainwreck: sacrificing Britney to save America. In: S. Holmes and D. Negra, eds. In the limelight and under the microscope: forms and functions of female celebrity. New York: Continuum, 303–332.

- Wetherell, M., 2012. Affect and emotion: a new social science understanding. London: Sage.

- Winch, A., 2013. Girlfriends and postfeminist sisterhood. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Winter’s bone, 2010. Film. Directed by Debra Granik. USA: Anonymous Content and Winter’s Bone Productions.