ABSTRACT

This article explores the link between national success as a writer and the promotional structures of world literature in the West. It does so through critically examining how individual people relate to the various creative processes that underpin literature as it travels around the western world. The article draws in particular on Bruno Latour’s work on the concepts of ‘agency’ and ‘mediators’ in the context of actor–network theory, as well as developing the idea of a ‘network intellectual’ put forward in 2015 by Fred Turner and Christine Larson. In so doing, the article finds common ground between literary studies and celebrity studies that can help parse the concept of ‘literary celebrity’. The model for understanding the links between authorship, celebrity and world literature that I propose is exemplified through reference to the intertwined contemporary careers of novelists Daniel Kehlmann and Jonathan Franzen. Both writers have achieved bestseller status in their respective national contexts (Germany/Austria and the United States), both deliberately seek to place their work and person into dialogue with key writers and works from other national traditions, and both have been systematically promoted across multiple countries as international success stories. Approaching them as contemporary case studies in both world authorship and literary celebrity allows us to reconsider how individuals carry wider cultural value in an age of rapid network expansion.

1. Introduction

Literary celebrity has become established as a paradox (Jaffe Citation2005, Moran Citation2006, Mole Citation2007, York Citation2013) that sits somewhat uncomfortably in both literary and celebrity studies. Both areas of study address how changing notions of value that characterise nationally and globally connected markets affect cultural products and activity. If literary studies has a tendency to prioritise the role of the abstract, linguistically determined text in all this, celebrity studies shades its interest more towards extra-textual consideration of the person at the centre of public debates – in the case of literature, the author. But however the priorities are set, the sense of paradox that is common to both stems from a basic realisation that the attempt to champion the intangible and, in this sense, priceless aesthetic realm creates products and draws on broader promotional structures that are themselves fully inserted into the political and the economic spheres of life. This repeatedly throws up crises of conscience for the individual writers involved, or sets literary critics the task of explaining their chosen writers’ timeliness, hypocrisy or opportunism (see Moran Citation2000, Glass Citation2004, Hammill Citation2007, York Citation2013).

While fully acknowledging this paradox, this article takes the study of literary celebrity in a slightly different direction. Reading it through the lens of circulation (Damrosch Citation2003, Apter Citation2013) that comes from world literature, I ask what happens when we take seriously the idea that not just texts but also people and their authorial image or brand circulate outside the home territory. Discussion of literary celebrity thus far has been almost exclusively bound to national contexts of literature. Yet for those of us invested in analysing the rise of world literature as both a consciously emerging field of literary activity (Apter Citation2013) and an economically-driven publishing phenomenon that defines the early decades of the twenty-first century (Walkowitz Citation2015), a conceptual and methodological approach that sets out how people relate to systemic processes at the point where they and their work begin to travel is crucial. I therefore explore how existing work in celebrity studies that sensitises us to the fundamentally collaborative nature of literary labour (York Citation2013, Ohlsson et al. Citation2014) can help us give tangible form to a ‘world author’ figure (Braun Citation2015) that might restore people to literary processes, precisely through analysing how their experiences of fame and agency pass through multiple cultural locations. At the same time, I ask what the resulting ‘world author function’ might be able to tell us about literary celebrity.

2. On notions of fame and agency in the literary sector

If anything continues to render literary celebrity distinct from other forms of celebrity, it is the interlinked notions of intellectual achievement and individual, self-determined agency. For all of the recent work in celebrity studies that has underlined celebrities’ proactive behaviour in shaping the production and mediatisation of their persona or star/celebrity image (for example, Turner Citation2004, Redmond and Holmes Citation2007, Marshall Citation2010, Rojek Citation2016), for most dyed-in-the-wool literary theorists this sort of agency still seems a long way from how authors set about interacting with readers. Film stars and fashion models are demonstrably always acting a role that is largely designed and brought across by other people; footballers and cyclists are performing a physical task that draws on their expertly trained bodies. Writers, as they speak and write their way to public attention, are putting out their ideas, from their brains, and with apparently little input from anyone else. In a world that still broadly clings to a mind–body hierarchy, this is qualitatively the closest we will ever get to the ‘real person’, or Rojek’s (Citation2001) ‘veridical self’. Whilst much of what follows will question the belief in this distinction, the illusion of individual determinacy – what I shall go on to term ‘assumed agency’ – remains sufficiently powerful in both the popular public reception of authors and the academic conventions that surround our study of named canons to demand ongoing consideration. So how can we conceptualise literary agency in a way that accounts for both this fundamental belief in the independent actions of the individual writer and her obvious functionalisation through the structural processes of the literary industry?

The work of the sociologist Bruno Latour offers us one promising way. In Reassembling the Social, Latour (Citation2005) sets about mapping how we can both critique and study so-called ‘social’ phenomena that link up achievements in discrete areas that are routinely assessed with their own methods and in their own right (like ‘literature’ and ‘book sales figures’).Footnote1 Developing actor–network theory, he proposes that social relations can only be made quantifiable through a process of ‘following the actors themselves’. Importantly, while the human beings involved in any network to be studied count as ‘actors’, so do non-human elements. Latour explains:

[E]ven though the question seems really odd at first – not to say in bad taste – whenever anyone speaks of a ‘system’, a ‘global feature’, a ‘structure’, a ‘society’, an ‘empire’, a ‘world economy’, an ‘organization’, the first ANT [actor–network theory] reflex should be to ask: ‘In which building? In which bureau? Through which corridor is it accessible? Which colleagues has it been read to? How has it been compiled?’ (Latour Citation2005, p. 183)

While the people are important, so too are the spaces in which they work, the intellectual traditions invoked, the technical processes and the material objects involved. Latour describes how the sociologist must set about tracing these, in order to build up a map of relations. Particularly important ideas, traditions, physical spaces or powerful individuals who facilitate connections to a large number of actors will emerge on this map as discernible nodes. The larger the node, the greater its relative social significance. Thus we can both set out how different aspects of society relate to one another and determine their relative social significance. Latour’s approach opens up a systematic way of analysing how literary celebrity functions across different fields of activity, in both national and global contexts.

A second important perspective is brought to bear by the recent work of media theorists Fred Turner and Christine Larson (Citation2015). Turner and Larson are looking at another form of celebrity intellectual from the literary author, namely high-profile mediators of science and new technologies. Individuals such as Tim O’Reilly, Norbert Wiener and Stewart Brand have emerged from the inherently collaborative context of laboratory-based research to build lucrative careers far beyond their original field of expertise. Turner and Larson argue that the inherently networked context from which these individuals come has produced a fundamentally different form of promotion for both themselves and their original work. Instead of relying on pre-existing media dissemination methods to bring them to a wide audience, the new kinds of celebrity are marked out by their proactive approach to finding an audience and steering the terms of the discourse into which they are inserted:

Unlike the mass media celebrities and public intellectuals with whom we’re most familiar, network intellectuals build the social and intellectual communities that bring them fame. Within these communities, they help develop new social and institutional ties and, with them, new ideas and turns of phrase. They then package this work in books and articles and speeches that promote the networks of people and ideas they’ve built and enhance their own standing. (Turner and Larson Citation2015, p. 55)

This approach to studying how intellectual achievement is communicated to a diverse audience places agency back at the heart of structural processes, whilst at the same time allowing it to be dispersed between multiple actors and located in multiple managed settings, as is commonly the case for more popular forms of celebrity. It also maps on to recent compelling work by Sharon Marcus (Citation2015b). Marcus insists that true celebrity of any form only begins when an individual brings together multiple, diverse publics who would not otherwise have anything linking them. Turner and Larson’s (Citation2015) work is attractive for my purposes precisely because it allows us to account for an individual’s proactive attempts to develop ideas and intellectual working practices of some kind of inherent epistemological value whilst at the same time linking this to a (human-led) systemic will for success that will commodify whatever constituent parts of that success it can. Furthermore, in linking individual achievement to broader self-driven disseminatory practices, the notion of the ‘network intellectual’ allows a new way of thinking about the humanities-led intellectual achievement. Their term gives us a way of expressing how ‘assumed agency’ emerges from the networks of literary relations (as Latour might phrase it) that include the non-human and the collaborative and cohere in the public presence and actions of a driven, self-promoting individual.

3. The writer as a network intellectual in the literary market: Daniel Kehlmann’s literary celebrity

By 2005, Daniel Kehlmann was an averagely successful author with a respectable literary and market profile in German-speaking Europe: he had published five novels or novellas, had won several scholarships and prizes, and had his most recent work reviewed in the national newspapers. He was well connected with publishers and fellow writers, but, by his own account, he was just about on the breadline. With the unexpected bestseller success of Die Vermessung der Welt in Citation2005 (Kehlmann Citation2005; Measuring the World, trans. Carol Brown Janeway, Citation2007), however, Kehlmann’s position within the German literary industry was transformed to that of a literary celebrity. He went from being one of a number of writers broadly following a similar aesthetic programme within a diverse and contested literary landscape to occupying a singular position representing contemporary literature’s broader social significance, both within Germany and beyond. The success of his text was discussed at length by an unusually broad cross-section of society – in addition to the usual literary critics, scientists and historians also weighed in on account of the book’s pseudo-historical and scientific subject matter. The text’s humour and readability won it many additional readers who might not otherwise engage with literature. Furthermore, Kehlmann’s authorial persona was equally propelled into the limelight. Where the prizes he had hitherto attracted had been largely low profile and geared towards supporting his future work, he now received a host of national awards that explicitly rewarded his authorial persona and achievements hitherto and, in so doing, implicitly appropriated him as part of the national literary tradition: the Heinrich von Kleist prize, the Thomas Mann Prize and the Welt Literature Prize in 2006/07 alone (on the particular significance of these prizes, see Braun Citation2014).

This aspect of Kehlmann’s career trajectory might in itself be enough to justify the label of ‘literary celebrity’, if the term simply means being celebrated as an important reference point within literary circles: a celebrity amongst literary folk, disseminated to these audiences through processes of fetishisation that are also common to the realm of popular culture (for more on this understanding of literary celebrity, see Braun Citation2011; for achieved celebrity more generally, see Rojek Citation2001, Turner Citation2004). Bringing in Marcus’s (Citation2015b) definition of celebrity as someone who is capable of drawing together multiple, diverse publics, however, raises the stakes for literary celebrity. Such a degree of broad public resonance is much harder for literary writers to achieve directly, because reading literary texts tends to remain a comparatively niche activity. Nevertheless, Kehlmann’s subject matter did bring him to the attention of many historians and scientists who might not otherwise have engaged with contemporary German fiction, while the economic success of his work has been enough to convince TV chat show hosts, radio programmers and organisers of public festivals that he should be regularly on their guest list (by the time a film version was released in 2012, 2.3 million copies had been sold in Germany alone; Körzdörfer Citation2012).

By 2007 at the very latest, Kehlmann had become a literary celebrity in German-speaking Europe by both definitions (within the particular field of literature, and beyond).Footnote2 As he has repeatedly commented in radio and TV interviews as well as journalistic pieces since, he found himself repeatedly functionalised by a literary industry that revolved around the writer making his authorial persona available on an almost daily basis for public readings, signings, talks and interviews. This popular public engagement with the author has itself spun him beyond the literary. A cartoon strip drawn up by the comic duo Katz & Goldt when sales of Measuring the World hit one million in Germany, and available for a time as a live link on Kehlmann’s website, makes a joke out of the multiple cultural appropriations of Measuring the World: it has become a product passed between people, most of whom never actually read it but all of whom use it to further their own social relations (Katz & Goldt Citationn.d.). The cartoon pillories the paradox of literary celebrity outlined earlier: authors are both idolised as inherently embodying cultural value and immediately commodified in their exertion of this function.

What is most interesting for our purposes in this section of Kehlmann’s career, however, is the way the author begins to function as a ‘node’: to borrow again from Latour, his authorship becomes a larger node on the map of actor–network relations, as ever more cultural and economic initiatives that mark out the contemporary moment are routed through him. Drawing together Marcus’s conceptualisation of the multiple and diverse publics that coalesce around a celebrity and Turner and Larson’s discussion of the ‘network intellectual’, we can visualise literary celebrity as a critical mass that is reached in the number of connections which run through an author’s individual node. This mass is measured both in terms of the sheer number of other actors touched by that individual, and in terms of a significant spread of types of actor, such that the attention that is being bestowed upon the famous author comes from diverse sources well beyond Bourdieu’s (Citation1996) traditional literary field (i.e. staked out by primarily literary actors) and mobilises many different media and institutional settings.

The difference between recognition as an author and recognition as a literary celebrity is, by this model, simply one of scale. The celebrity status that results when one individual’s achievement is sufficiently recognised both coheres around the individual with whom the literary text is most strongly identified (almost always: the author) and is the consequence of the entire set of connections that emanates out from that individual. As the author becomes a literary celebrity, she therefore both gains in assumed agency (her writerly achievements are celebrated as entirely her own and better than those of her immediate contemporaries) and becomes ever more connected to other actors. The actions of these actors begin to alter her individual work and its putative meaning.

In our example of Daniel Kehlmann, this process can be traced through the intermingling of cartoon strip, broadsheet interview and novelistic work that followed the success of Measuring the World. In 2008, Kehlmann agreed to do a series of interviews with Adam Soboczynski, a journalist from the major weekly newspaper Die Zeit, who wanted to write a portrait piece about his experience of success. While meeting for these interviews, Kehlmann began to write a short fictional piece about a writer, Leo Richter, who likewise agrees to do a series of interviews with a journalist from a major weekly newspaper. The subsequent portrait that was written up by the real-life Soboczynski was published in Die Zeit accompanied by Kehlmann’s fictional piece. Both were then reissued in book form, but now additionally accompanied by cartoon illustrations by Frank Stockton for the fictional story about Leo Richter and photographs of Kehlmann by Heji Shin for the real journalistic piece (Kehlmann Citation2009b). The description of all four writers and illustrators in the paratextual materials for this short project emphasise their award-winning attributes, while Soboczynski even begins his portrait by openly acknowledging that the journalist hopes for some of his subject’s prestige to rub off on him (Kehlmann Citation2009b, p. 45). Meanwhile, Leo Richter, the anguished, self-regarding writer who battles with the demands of the media, went on to become one of the key protagonists in Kehlmann’s subsequent novel, Ruhm (Kehlmann Citation2009a; Fame, trans. Carol Brown Janeway, Citation2010).

This brief gloss on the genesis of the novel that follows the hugely successful Measuring the World not only shows an author using his art to respond to his real-life circumstances. It also shows how much the networks into which he is drawn by other actors – the journalist, the newspaper as a cultural institution, the various traditions of visual art that were made available to him – affect both what his authorship is and how it can be perceived by a diverse set of publics. Kehlmann’s individual agency in all this appears to grow – he is ever more present and active in multiple contexts – whilst his direct control over the work and person he represents actually diminishes. The opening paragraph of Soboczynski’s portrait says this directly:

The portrait painter is powerful, because his observations are irrefutable; he draws his conclusions from a dismissive hand gesture, a noisy sneeze, or an angry outbreak from his sitter, and the latter is powerless to stop him. (Kehlmann Citation2009b, p. 45; my translation)

Such a statement underlines the inherently transformative power of the media in the whole process of celebrity construction, whilst at the same time stressing the key role played by a diverse set of individual people with the various technologies available to them (for more on the impact of new technologies on celebrity, see Marshall Citation2010, Marcus Citation2015a, Rojek Citation2016).

This relativising trend in the famous author’s actual, as opposed to assumed, agency continues as we move from the national confines of literary celebrity to world literary authorship. The logical next step for someone who has achieved such national recognition as Kehlmann had by 2007 is for his or her network relations to expand to such an extent that their node becomes visible on a global scale. This too has an element of the uncontrollable about it. We retrospectively intuit some sort of ‘jump’ – whether this is in sales figures, dissemination practices, or perceived cultural or political relevance – that can propel a nationally successful author onto a world stage. However, in discussing how to map the relationship between the local and the global, Latour insists on ‘flatness’ and avoiding the kind of 3D map that sees the global either hovering above the local or somehow framing or engulfing it. Addressing the question of how to scale up our model of social interconnectedness, he argues that the macro should be subject to the same networking scrutiny as the micro, with the resulting connections mapped out in exactly the same way:

Macro no longer describes a wider or a larger site in which the micro would be embedded like some Russian Matryoshka doll, but another equally local, equally micro place, which is connected to many others through some medium transporting specific types of traces. No place can be said to be bigger than any other place, but some can be said to benefit from far safer connections with many more places than others. (Latour Citation2005, p. 176; original emphases)

The bigger ‘scale’ that we perceive is itself a projection initiated by the actors themselves – in our case, the authors, but also the publishers, prize juries and marketing agents, and indeed the materiality of the books thus produced, the established trade channels and the resonance of specific publishing addresses. Rather than simply reaffirming the global nature of this scale as the bigger, grander encompassing frame that we then appropriate to judge success, we should set about making the very act of projection by the individual actors visible:

[…] if there is one thing you cannot do in the actor’s stead it is to decide where they stand on a scale going from small to big, because at every turn of their many attempts at justifying their behaviour they may suddenly mobilize the whole of humanity, France, capitalism, and reason while, a minute later, they may settle for a local compromise. (Latour Citation2005, pp. 184–185)

Finally, Latour argues that the ‘big picture’ or ‘global sweep’, which is nevertheless routinely produced in, for example, influential newsrooms or cultural institutes and which carries much credence, must be subjected to analysis as part of an always-local network: the ‘panoramas’, as he calls them, are produced in specific, located sites. Because these grand contextualising narratives are never anything more than a projection within a closed space, they will always have blind spots. However, they remain powerful, and thus are an important part of the network map we are tracing, because ‘they allow spectators, listeners, and readers to be equipped with a desire for wholeness and centrality. It is from those powerful stories that we get our metaphors for what “binds us together”’ (Latour Citation2005, p. 189; original emphasis).

Latour’s conceptual insistence on the grounded nature of all connections is important, because it stops us conceiving of world literary authorship as simply a heightened form of literary celebrity in the simple definition, whereby one person’s achievements are celebrated on an ever larger scale, such that they outgrow their local links. If we instead focus on world authorship as the growth of an author’s connections to actors in diverse geographical and cultural locations, and then look at how these connections are mapped on to a discourse of globally significant achievement, we open up a rather more robust framework for understanding how a transnationally connected author interfaces with diverse publics in today’s environment. One might add, at this juncture, that the blind spots Latour warns about apply equally to this research paper: because we are following the actions and connections between Franzen and Kehlmann, the map of ‘world’ literary authorship that we are tracing is skewed to a western, capitalist perspective. If we were to follow the networks around, say, the Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o or a group of lesser-known Indian writers, different concepts, institutions and people are likely to loom large. Nevertheless, as an exercise in uncovering the principles of how fame and agency move from one location to another as writers seek to expand their networks beyond their home territory, the results might not be so very different, at least when the direction of travel is into or through the West (Huggan Citation2001 and English Citation2005 are both good places to begin looking at the multiple mediators that cohere around non-western authorship on this sort of journey). Indeed, as we shall see in what follows, moving from a primarily local network to a more globally connected one does not necessarily entail growing in importance and leaving local settings behind. In fact, tracing Daniel Kehlmann’s positioning as a ‘world author’ relativises the intense interest to which his celebrity authorial persona has been subject in the German context over the past 10 years.

4. Re-presenting cultural achievement around the world: Jonathan Franzen and Daniel Kehlmann

If Kehlmann rose to fame in the German context on account of his success at mediating the concept of ‘readability’ to a diverse set of publics there (Schaper Citation2016), his attraction to the English-speaking world, where entertaining, readable texts have long been the norm, lay elsewhere. In fact, here it is his very immersion in the Germanic literary-philosophical tradition that recommended him to the major US writer Jonathan Franzen. Franzen’s big American novels, such as The Corrections (Franzen Citation2001) and Freedom (Franzen Citation2010), can be read as studies in creating readable plots that speak directly to many people’s interests whilst trying to make the case for literature. As large-scale literary projects they are also a response to the particular state of the Anglo-American novel, as he first set it out in his 1996 literary manifesto in Harper’s Magazine, ‘Perchance to Dream: In the Age of Images, a Reason to Write Novels’, and has subsequently reflected on in a variety of media contexts, many of which earned him considerable media coverage (Franzen Citation2002). However, since these landmark US-focused statements, Franzen has increasingly sought to connect his work up with Central European literary and philosophical traditions. In turning his attention to the European literary scene, he came across Kehlmann just after Measuring the World had been written. At this juncture in his career, what was interesting for Franzen about Kehlmann was not the fact that he could write a humorous, readable book about German scientific achievement, but that he could make available to him a whole Germanic tradition of complex writing that reflects on how literature interfaces with a wider audience. Kehlmann’s ability to act as a form of gatekeeper for this literary-philosophical tradition resulted in a friendship that gave the German author regular and direct access to the heart of the US literary scene – including ringing endorsements from Franzen on the dust jacket of Fame when it appeared in English in 2010.

However, there is much more to be gleaned from this cross-cultural friendship between two literary celebrities than simply mutual promotion in the English- and German-speaking worlds. As prize-winning authors whose works have subsequently been translated and circulated more widely, Franzen and Kehlmann are now themselves coming into contact with new publics, new literary ideas and new cultural traditions. Furthermore, by mutually supporting one another in Turner and Larson’s (Citation2015) sense of the network intellectual, each is deliberately recalibrating the network of which they are part, bringing a recognisably global aspect to their authorial nodes. Kehlmann has written at length about Anglo-American literature, so positioning himself in that literary network is an obvious move towards strengthening the links between his German-language work and that tradition. Likewise, Franzen has been outwardly Germanophile for many years and clearly seeks cultural cachet from being able to present himself as au fait with European contexts of literature. But even if this network expansion was not actively sought by either national literary celebrity, the principles underpinning it would still apply to any writer whose success beyond the home territory links her to people and concepts rooted in other cultural contexts. As new connections are forged with individuals, institutions or concepts that act as significant nodes in different parts of the world, the assumed agency that was hitherto channelled through the individual writer acting as a literary celebrity on a national stage now underpins a transnationally active author function.

What exactly is at stake for literary celebrity in this unfolding experience of ‘world authorship’ (Braun Citation2015) is documented in multiple ways in Franzen’s (Citation2013) The Kraus Project, which shows the network intellectual at work in many different ways. Indeed, the text is exemplary for the much broader phenomenon of world authorship, because it takes the unusual step of merging the documentation of a collaborative, mediatory process with the finalised, mediated product that bears just one author’s name. Like the pipes and shafts on the exterior of Paris’s Centre Pompidou, it thereby also places on full public view a version – albeit one clearly guided by that one acknowledged author’s hand – of all the connections that Latour has taught us to trace through the individual nodes which collectively constitute any network and here drive the literary.

The spread of literary agency that is accordingly exemplified here, and which underpins world literature as a circulatory practice, is to be understood in line with Latour’s concept of the ‘mediator’. Unlike a simple ‘intermediary’, a ‘mediator’ has its own agency that not only conveys a message from point a to point b, but also leaves a trace on that message, both altering it and being altered by it in the process (Latour Citation2005, p. 39). In The Kraus Project, Franzen the network intellectual and well-known US literary celebrity pays homage to the early twentieth-century Viennese satirist Karl Kraus, who is a major name in the German literary canon. He does this by both mediating some of his work, through an English-language translation, to a contemporary Anglophone audience, and casting his own literary person in the culturally elite German-speaking European literary tradition as he does so. There is an obvious ambition here to enhance his own literary brand. In order to do this, Franzen provides a very readable translation of two of Kraus’s best known and linguistically difficult essays, ‘Heine and the Consequences’ and ‘Nestroy and Posterity’, together with two later shorter pieces (Franzen Citation2013). These are printed in a parallel-text, bilingual edition, with the English side heavily annotated. Within these annotations, which at times can take up an entire page, or even a range of pages, Franzen expounds in great detail how his own thoughts interact with those of Kraus. Both the mediator (Franzen) and the mediated (Kraus) are affected by the process of mediation that is itself documented in and enacted by the text. However, the interactive, affective nature of mediation around these two literary celebrities does not stop there. Two additional writers feature prominently in Franzen’s mediatory apparatus: the American academic Paul Reitter, who gives extensive specialist knowledge in the footnotes and provided significant help with the translation, and Daniel Kehlmann. Both authors are quoted verbatim, and sometimes at considerable length, in Franzen’s extended footnotes, such that their engagement with Kraus both offsets and underpins his.

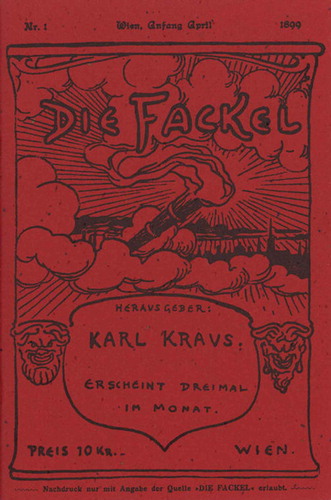

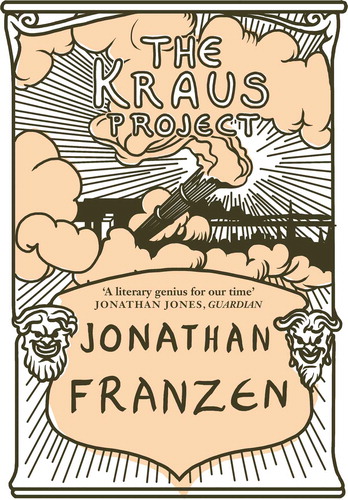

In all of this, Franzen presents himself as much more than merely a faithful translator, editor or celebrity introducer (via a forward or other paratextual apparatus), and both material and legal media conventions assist him in this. The cover of the UK English paperback of The Kraus Project is modelled directly on that of Kraus’s literary journal, Die Fackel (The Torch, 1899–1936) (). This periodical initially published contributions from a range of writers and intellectuals, but in 1911 became an entirely sole-authored affair that was widely read by other writers and journalists on account of its visceral polemics, and Kraus’s brand was fetishised accordingly (Reitter tells us it had a circulation of some 30,000 at its peak; Franzen Citation2013, p. 57). By visually appropriating the journal’s cover for his own translation and comment on Kraus’s essays, Franzen makes clear the extent to which he is appropriating Kraus’s controversial authorial position for his own publication, The Kraus Project, which bears just Franzen’s authorial name on the front cover (). Kraus thereby becomes the subject matter and Franzen the author, despite the large portion of the text that is in fact authored by Kraus and the considerable portion of the footnotes that are authored by Reitter and Kehlmann. The copyright declaration for the work as a whole underlines Franzen’s authoritative appropriation of everything, with just the copyright for their quotable portion of the footnotes attributed to Reitter and Kehlmann: ‘Jonathan Franzen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work’ (Franzen Citation2013).

Figure 2. Reproduction of The Kraus Project Fourth Estate Citation2013 book cover. © HarperCollins.

Both Kehlmann and Reitter have an acknowledged gatekeeper function in all this, because they have greater access to the German-language culture that Franzen so prizes and is at pains to appropriate for himself as much as possible. Towards the end of the text, the famous US author does acknowledge his debt to the other writer figures involved in the project:

I felt that I’d outgrown Kraus, felt that he was an angry young man’s kind of writer, ultimately not a novelist’s kind of writer. What’s drawn me back to him now is partly my affection for Kehlmann and my susceptibility to his enthusiasm; partly the opportunity to understand better, thanks to Paul Reitter, what the hell Kraus was talking about; and partly the beauty of Kraus’s language and humor, to which I’ve attempted to do more justice here than I did at twenty-three; but also, and maybe most important, a nagging sense that apocalypse, after seeming to recede for a while, is still in the picture. (Franzen Citation2013, p. 273)

This admission is revealing, because it highlights both the importance of the collaboration for Franzen’s mediation of Kraus’s global significance and his own attempts to speak authoritatively to the world. Franzen wants to be a ‘world author’, in the sense both of writing about globally significant things and of being someone who can draw on a large swathe of the dominant Central European literary and philosophical canon that, up until very recently, has underpinned conventional understandings of ‘world literature’. Franzen discerns an unrealised potential both in Karl Kraus and in himself to take on this role for the early twenty-first century, but in order to bring it about he needs multiple collaborators. Key to all this is the way he intermingles the power of his own brand of literary celebrity with that of other writers, both living and dead.

However, despite their founding importance for the project, Reitter and Kehlmann are accorded subordinate positions in Franzen’s text. This can be seen in Franzen’s stage-managing of the footnotes, in which the evolving narrative increasingly leads to him, his opinions and his development as a writer. But it is also visually and performatively apparent in a YouTube video that accompanied the book’s launch in the Deutsches Haus (German House) at New York University. Both a full hour-and-a-half-long video of the podium discussion between Franzen, Kehlmann and Reitter and a one-and-a-half minute trailer of the event are available (Deutsches Haus Citation2013a, Citation2013b). There is not space here to analyse either in detail, but just briefly touching on the trailer () reinforces a number of my key points. These pertain to the nature of the ‘panoramic’ network that an author, acting as a network intellectual aiming to straddle multiple geographies and cultural traditions, builds around him- or herself. They also pertain to the blind spots that accompany such willed agency, as the individual, acting as a ‘world author’, taps into and is affected by processes of literary celebrity as they play out in local contexts.

Figure 3. Daniel Kehlmann (left), Jonathan Franzen (centre) and Paul Reitter (right) on the podium at the Deutsches Haus. Image reproduced with kind permission, © Laia Cabrera & Co.

Firstly, although an image of Kraus is projected on two large screens in the room and Franzen sets out his intellectual debt to the author, it is clear throughout that the product at the heart of this event is the book authored by Franzen – which he is shown confidently signing with a flourish at the end of the trailer, literally inscribing his authorial name over the bulk of the title page. This shows the extent to which Franzen’s putative remediation of Kraus as an important figure of world literature to a contemporary audience is significantly overlaid by his own self-projection as a literary celebrity in both local and global terms (pace Latour, earlier). But there are also many more people than Franzen at work here: the book-signing event will have been orchestrated by his publisher, while the readers are the people who request the signature. These network dynamics are reinforced by a number of spatial factors. The positioning of the three living authors, with Franzen at the centre of the trio – they call themselves a ‘Kraus troika’ – makes it abundantly apparent that he is the ‘node’ from which the most connections radiate (). The placing of the living authors on a podium and the dead author flat against two screens positioned to the side underscores the pre-eminence of contemporary Anglophone culture as the larger appropriating discourse, further relativising not just Kraus but also Kehlmann. Thirdly, the video itself acts unwittingly as a reflection on the ‘panorama’ of worldness that all three writers – in conjunction with the German House in New York and quite possibly the US publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux – project. The high-quality production is situated in a plush room full of well-to-do, largely white, middle-aged people in the middle of a wealthy capital city characterised by bright lights and tall buildings. It is set to a self-consciously ‘contemporary’ musical background, whose insistent pulsating score is reminiscent of ‘breaking news’ updates.

The blind spots of which Latour warns are apparent: all three writers on the podium, together with the moderator, are men in suits, speaking from positions of cultural privilege in an elite location. It is notable that throughout The Kraus Project no reference whatsoever is made to women, although there is ample opportunity for any of the three contributors on the project to highlight absences in Kraus’s own creation of a canon, or to reflect on the gender politics of their own contemporary setting. Indeed, a gender-aware reading of the literary text would have to point out that it is an entirely self-contained, male affair of camaraderie and intellectual affinity across a markedly male canon.

While The Kraus Project clearly supports Franzen’s growth of assumed agency as a network intellectual in multiple ways, only some of which he directly controls, Kehlmann’s involvement in the transnational initiative takes a rather different trajectory. From his point of view, while pursuing a high-profile connection to Jonathan Franzen might increase his cultural cachet in the eyes of any German readers who happen to follow his activities in the United States, it does not result in a degree of global recognition that surpasses his German-based literary celebrity. Rather, as the video trailer makes visually evident, in the company of Franzen his importance and achievements are distinctly relativised, such that in the text of The Kraus Project he even has to be reintroduced on several occasions. In so doing, Franzen largely downplays his main career as a creative writer: Kehlmann is ‘my friend Daniel Kehlmann, who is an actual Viennese and a deep student of Kraus’ on his first arrival in the text (Franzen Citation2013, p. 67). Later he is glossed again as ‘Kehlmann, the Viennese and major Kraus fan’ (Citation2013, p. 165), while still later again he gets a whole new introduction, as Franzen recollects a visit to Vienna where he found himself surrounded by the very kind of journalists which he, through Kraus, has been railing against:

Thankfully, there was also a goofily friendly, immensely well-read young man who apologized for the journalists and was eager to talk about Karl Kraus. His name was unfamiliar, but his novel Measuring the World was about to become one of the bestselling fiction titles in German publishing history. This was Kehlmann. (Franzen Citation2013, p. 189)

Only at this point, almost 200 pages in, does Kehlmann graduate from being Franzen’s authentic Viennese friend to an independently successful literary writer. This is instructive on a number of levels. Kehlmann’s very inclusion in the project, from inception through execution to the subsequent marketing, does demonstrate his success at maintaining meaningful connections with people and institutions well beyond his immediate national confines. As we follow his interaction with the famous US writer and the established academic in US German Studies in powerful institutional surroundings, we see him proactively building his own network and thereby expanding his node. When he pursues these connections, however, his own agency as a literary celebrity also becomes smaller, relativised by the multiple actors with which he interacts. This is because the more his authorship moves beyond his immediate, local network, the more it becomes modified by multiple mediators. Even if Franzen was to do nothing explicit to introduce him to an Anglophone audience, the mere fact of Kehlmann appearing alongside him in the German House in New York automatically modifies Kehlmann’s authorship by dint of association.

This of course applies in the other direction too, so that in Germany Franzen’s authorial brand is affected by his proximity to Kehlmann: here, Franzen is placed within the markedly German discourse of ‘readability’, which is arguably something the US author has been trying to move away from in more recent years, and which certainly does not sit particularly well with The Kraus Project. Thus, in 2013 Franzen was awarded the public-facing Welt-Literaturpreis (Welt literary prize, named after the Welt newspaper) that had gone to Kehlmann six years earlier and which explicitly rewards pre-existing success both across Germany and internationally. Kehlmann provided the congratulatory address, framing in particular how Franzen had taught him to write the kinds of books that he might actually like to read, and ending by punning on the prize’s name to emphasise that Franzen’s ability to combine deep thought with accessible writing makes him a worthy recipient of a ‘Weltliteraturpreis’ (world literature prize) (Kehlmann Citation2013). Bearing in mind Kehlmann’s position as a former laureate of the prize as well as a household name in Germany, the celebrity dynamics here are partially reversed from those at the German House in New York, even though Kehlmann is careful to stress Franzen’s seniority. In particular, it is his turn now to introduce Franzen as his ‘friend’, which he flags up straight away in the sub-title of the printed version of his speech – ‘a congratulatory address for my friend’ – before reflecting further on relations of literary influence as well as real emotional affinity.Footnote3 Furthermore, in 2014 The Kraus Project was translated back into German (now minus Franzen’s English translations) (Franzen Citation2014) and published with a book cover that rendered his name as a footnote to the (in this German-speaking context) culturally higher-status author Kraus ().

Figure 4. Reproduction of Das Kraus Projekt Rowohlt Citation2014 cover.

In extending the network of connections around authors who are literary celebrities in their home market territory, world authorship thus further diminishes the actual agency of the individual author as his or her ‘flat’ network grows ever larger around them, while the level of assumed agency may grow or shrink depending on the particular dynamics of the different local settings involved. At the same time, both Kehlmann and Franzen’s active participation in a deliberately cross-cultural network shows the extent to which they are consciously operating as Turner and Larson’s ‘network intellectual’ who knows exactly how to build audiences in multiple contexts for ideas that have been grown by a whole team of people. In fact, as representative connective nodes on the global literary map whose assumed agency as literary celebrities in their home territory is high, they grow in inverse proportion to the rate that their actual agency as literary writers mediating their texts shrinks.

5. The world author in us all?

I have gone into such depth on both Kehlmann’s career to date and Franzen’s Citation2013 collaborative text because the interconnected case studies they provide illustrate a number of key points about world authorship, and this in turn gives us new purchase on the concept of literary celebrity.

First, the kind of literary celebrity that can be routinely achieved within a national context is not inherently a precursor to global fame. The example of Kehlmann’s career shows that even achieving literary celebrity amongst diverse publics for addressing transnational issues and attracting a significant global market share does not automatically make the nationally famous author into a globally recognised literary celebrity. Rather, if the author gets beyond her national context at all, her position as the originator of a literary text is likely to appear weaker and more relativised in other regional settings around the world. In terms of exerting direct control over the network that Turner and Larson’s concept implies, this also rings true for the case of Franzen in Germany, despite the global strength of his brand and his particular German fan base.

Second, an author requires multiple mediators if he or she is to move from one cultural context to another – and even more if he or she is to co-exist in both. These mediators are likely to change the image of the author and/or his or her writing quite significantly. Both Franzen and Kehlmann show clear traits of Turner and Larson’s ‘network intellectual’ because they both benefit from and disperse themselves through one another’s networks to promote their own ideas and authorial personae. At the same time, Latour’s non-human actors exert considerable influence over the way their willed recalibration is more broadly socially coded.

Third, the more authorship moves beyond its immediate, local network, the more it becomes modified by multiple mediators. Accordingly, literary celebrity, understood as a position of cultural power through mass recognition, is both enhanced by a visible enactment of world authorship and curtailed, depending on which position one is looking from on the map. This distinction in degrees of actual agency and promotional autonomy is crucial, because it allows us to sketch out a far more robust framework for understanding how a literary-celebrity-turned-world-author interfaces with diverse publics nationally and internationally.

To return to my opening comments about literary celebrity and world literature, this article has shown how the fundamentally collaborative nature of authorship at both national and transnational levels can be uncovered and used to differentiate our understanding of how agency unfolds as literary celebrity travels. Such an acknowledgement has significant repercussions for how we understand the practice of close reading that remains the stock-in-trade for most literary scholars. In order fully to grasp the collaborative nature of authorship, we need additional, complementary conceptual and methodological approaches. This is a matter of establishing how to put human agency back at the heart of structural processes, but in such a way that acknowledges this agency is dispersed between multiple actors which are both human and non-human in nature and are located in multiple managed settings. Latour’s sociological work, which provides both conceptual and methodological impetus in his ‘flat map’ and in his exhortation to ‘follow the actors themselves’ respectively, opens up a range of possibilities for just such systematic study. This article has explored one way of doing this in respect of a particular example that could be scaled up if space and time allowed. In time, I hope it might help underpin not just larger studies of literary relations and their ‘worldliness’, but also other methodological approaches to evaluating these networks; for example, digital mapping or anthropological practices of ‘thick description’. If applied systematically and sensitively, these methodologies have the potential not to trump or somehow replace literary close-reading, but rather to enhance the very investment in local and culturally specific forms of meaning that underpins all contemporary engagement with literature as both a personal relationship and a transnational phenomenon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecca Braun

Rebecca Braun is Senior Lecturer in German Studies and Director of the Authors & the World interdisciplinary research hub at Lancaster University, UK (www.authorsandtheworld.com). She has written widely on literary prize culture in the Central European context, as well as on how the work of individual German-language writers engages with the twentieth- and twenty-first-century media environment. Her monograph, Constructing Authorship in the Work of Günter Grass, was published by Oxford University Press in 2008. Recent co-edited publications include a special issue of the Canadian journal Seminar on ‘World Authorship’ with Andrew Piper in 2015, and, with Lyn Marven, the Cultural Impact in the German Context: Studies in Transmission, Reception, and Influence (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2010).

Notes

1. The examples are mine; Latour works more with examples from the sciences, but the principle is the same.

2. This date is chosen because that year marks both the award of the Welt-Literaturpreis (Welt literary prize) to Kehlmann – awarded to the ‘personality’ who has done the most for German literature – and the publication of Measuring the World in English translation. Publication in English is highly significant for non-Anglophone writing. On this phenomenon, see Sapiro (Citation2010).

3. Kehlmann explains in this speech how Franzen prefers to speak about ‘friendships’ with other writers when acknowledging literary influence, and it may well be that Franzen’s use of the term for Kehlmann in The Kraus Project, as set out earlier, is also tinged with this meaning. Considering that an uninitiated reader of either The Kraus Project or Daniel Kehlmann’s congratulatory address is unlikely to read it like this, however, and given the actual friendship that clearly links the two, the sense of camaraderie remains significant when looking at how each positions the other within their literary networks.

References

- Apter, E., 2013. Against world literature: on the politics of untranslatability. London: Verso.

- Bourdieu, P., 1996. The rules of art: genesis and structure of the literary field. Trans. by Susan Emanuel. Cambridge: Polity.

- Braun, R., 2011. Fetishising intellectual achievement: the Nobel Prize and European literary celebrity. Celebrity studies, 2 (3), 320–334.

- Braun, R., 2014. Prize Germans: changing notions of Germanness and the role of the award-winning author into the twenty-first century. Oxford German studies, 43 (1), Special issue on Institutions and Culture. Ed. S. Williams & D. Wilson, 37–54.

- Braun, R., 2015. Introduction: the rise of the world author from the death of world literature. Seminar: a journal of Germanic studies, 51 (2), Special Issue on World Authorship. Ed. R. Braun & A. Piper, 81–99.

- Damrosch, D., 2003. What is world literature? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Deutsches Haus at New York University, 2013a. The Kraus project: Jonathan Franzen, Daniel Kehlmann, and Paul Reitter. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5SPtKK2NPk [Accessed 8 June 2016].

- Deutsches Haus at New York University, 2013b. Trailer Kraus project: Jonathan Franzen, Daniel Kehlmann, and Paul Reitter. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AcZbHiUkATQ [Accessed 8 June 2016].

- English, J.F., 2005. The economy of prestige: prizes, awards, and the circulation of cultural value. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Franzen, J., 2001. The corrections. London: Fourth Estate.

- Franzen, J., 2002. How to be alone. London: Fourth Estate.

- Franzen, J., 2010. Freedom. London: Fourth Estate.

- Franzen, J., 2013. The Kraus project. London: Fourth Estate.

- Franzen, J., 2014. Das Kraus Projekt. Trans. B. Abarbanell. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- Glass, L., 2004. Authors Inc.: literary celebrity in the modern United States 1880–1980. New York: New York University Press.

- Hammill, F., 2007. Women, celebrity, and literary culture between the wars. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Huggan, G., 2001. The postcolonial exotic: marketing the margins. London: Routledge.

- Jaffe, A., 2005. Modernism and the culture of celebrity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Katz & Goldt, n.d. Der Comic zum Millionenseller. Available from: http://www.kehlmann.com/inhalt30.html [Accessed 8 June 2016].

- Kehlmann, D., 2007. Measuring the world. Trans. C. Janeway. London: Quercus.

- Kehlmann, D., 2005. Die Vermessung der Welt. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- Kehlmann, D., 2009a. Ruhm. Ein Roman in neun Geschichten. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- Kehlmann, D., 2009b. Leo Richters Porträt. Sowie ein Porträt des Autors von Adam Soboczynski. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

- Kehlmann, D., 2010. Fame. Trans. C. Janeway. London: Quercus.

- Kehlmann, D., 2013. Er hat uns gezeigt, wie man heute erzählen soll. Die Welt, 10 Nov. Available from: http://www.welt.de/kultur/literarischewelt/article121737859/Er-hat-uns-gezeigt-wie-man-heute-erzaehlen-soll.html [Accessed 29 July 2016].

- Körzdörfer, N., 2012. Zwei Genies erforschen die Welt – in 3D! Bild-Zeitung, 25 Oct. Available from: http://www.bild.de/unterhaltung/kino/kinostarts/die-vermessung-der-welt-26859516.bild.html [Accessed 8 June 2016].

- Latour, B., 2005. Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marcus, S., ed., 2015a. Public culture. Vol. 27 (1). Special issue on Celebrities and Publics in the Internet Era.

- Marcus, S., 2015b. Celebrity 2.0: the case of Marina Abramović. In: S. Marcus, ed. Public culture. 21–52.

- Marshall, P.D., 2010. The promotion and presentation of the self: celebrity as marker of presentational media. Celebrity studies, 1 (1), 35–48.

- Mole, T., 2007. Byron’s romantic celebrity: industrial culture and the hermeneutic of intimacy. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Moran, J., 2000. Star authors: literary celebrity in America. London: Pluto.

- Moran, J., 2006. The age of hype: the contemporary star system. In: P.D. Marshall, ed. The celebrity culture reader. New York: Routledge, 324–344.

- Ohlsson, A., Forslid, T., and Steiner, A., 2014. Literary celebrity reconsidered. Celebrity studies, 5 (1–2), 32–44.

- Redmond, S. and Holmes, S., eds., 2007. Stardom and celebrity: a reader. London: Sage.

- Rojek, C., 2001. Celebrity. London: Reaktion.

- Rojek, C., 2016. Presumed intimacy: para-social relationships in media, society, and celebrity culture. Cambridge: Polity.

- Sapiro, G., 2010. Globalisation and cultural diversity in the book market: the case of literary translations in the US and in France. Poetics, 38 (4), 419–439.

- Schaper, B., 2016. Poetik und Politik der Lesbarkeit in der deutschen Literatur. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Oxford.

- Turner, F. and Larson, C., 2015. Network celebrity: entrepreneurship and the new public intellectuals. In: S. Marcus, ed. Public culture. 53–84.

- Turner, G., 2004. Understanding celebrity. London: Sage.

- Walkowitz, R., 2015. Born translated: the contemporary novel in an age of world literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

- York, L., 2013. Margaret Atwood and the labour of literary celebrity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.