ABSTRACT

This article analyses the political style of the Dutch nationalist-populist celebrity politician Geert Wilders and examines the ways in which his self-stylisation epitomises both the strategic use of national imagery, and the affective embodiment of associated sentiments in his public persona. Using insights from imagology, we argue, firstly, that Wilders’ use of national images allows him to align himself with the traditional narrative of Dutch collective resistance to foreign rule and thus to authenticate his political attitude as compliant with that of the Dutch national character. Secondly, turning to the field of celebrity studies, we demonstrate that this self-stylisation also involves a form of emotional work. In speeches, texts, campaign advertisements, and tweets, Wilders projects an affectively charged public self that ‘moves’ the audience and lends a sense of urgency to his politics as well as a feeling of authenticity to his political persona.

Introduction

Geert Wilders is arguably ‘the most famous Dutch politician of the moment throughout the world’ (Vossen Citation2013, p. 8).Footnote1 As a member of the Dutch Lower House, chairman of the Party for Freedom, a figurehead of international anti-Islam alarmism (Vossen Citation2016), an outspoken Eurosceptic (Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2013), and a self-proclaimed ‘Dutch patriot’ (Vossen Citation2013, p. 82), Wilders has succeeded in capturing and maintaining the electorate’s attention with his provocative statements and mediagenic performance year after year. He has been accused of Islamophobia and fascism, convicted for inciting discrimination, and is protected by bodyguards 24/7. Despite this controversy, Wilders has proven to be a serious political force. Although the party has been part of the opposition since its establishment, polls indicate that at the time of writing (late 2018) it is the second to largest in Dutch parliament.

On 20 May 2014, Wilders defended his familiar anti-EU stance by cutting the ‘Dutch’ star out of the European flag during a self-staged political media event on Luxembourg Square in Brussels (see ). Wilders announced that the star should be returned to the Dutch people, promoting ‘Nexit’ – the complete withdrawal of the Netherlands from the ‘monster’ EU. Posing in front of the gathered press with the star in his hands, he concluded: ‘They will never get this back in Brussels’ (NOS Citation2014). This single media performance presents all of the individual elements that constitute Wilders’ political style, here defined as the ‘heterogeneous ensemble of ways of speaking, acting, looking, displaying, and handling things, which merge into a symbolic whole that immediately fuses matter and manner, message and package, argument and ritual’ (Pels Citation2003, p. 45). Wilders’ style includes the invocation of a looming, grotesque Other (i.e., Brussels as the seat of EU power); an us-versus-them rhetoric; the populist appeal to a national ‘people’, allegedly abandoned by the ‘elite’; nostalgia, fuelled by the sentiment that ‘we’ want to get things (e.g., sovereignty, the Guilder, independence, national identity) ‘back’; the hardboiled tone of the determined outsider; and a simple yet powerful imagery. He presents himself as the lone politician, the sole defender of the Dutch, armed with a pair of scissors and a cut up flag. The performance thus exemplified Wilders’ nationalist-populist politics (see Vossen Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Geert Wilders cutting the 'Dutch' star out of the EU flag. Reproduced with permission: AP Images/Hollandse Hoogte.

This particular media event can be considered especially revealing for two reasons. Firstly, it illustrates the increasing importance of nationalist sentiments in Wilders’ politics (see also Vossen Citation2011, p. 185, Citation2013, p. 81–92), emphasising the importance of cherishing ‘our’ Dutch culture, history, and identity in the party’s election manifestos (PVV Citation2006b, Citation2010, p. 33, Citation2012, p. 42–3, Wilders Citation2005, p. 120). Secondly, the event clearly exemplifies his highly effective and affective self-marketing strategies. Even though there was no political follow-up (e.g., a proposed amendment of the law or the introduction of a new policy), Wilders’ actions were broadly covered by Dutch and European news agencies alike. Via this simple street performance, Wilders managed to convince his audience of the urgency of his political message.

In this article, we argue that part of the appeal of Wilders’ self-stylisation results from precisely this effective combination of national imagery on the one hand, and the performative embodiment of associated sentiments on the other. Our aim is to bridge a gap in current research on Wilders’ politics. The increasing importance of national culture and identity in Wilders’ opinions and performances has been examined previously (Pels Citation2011, Vossen Citation2011, Lucardie and Voerman Citation2013, Otjes and Louwerse Citation2015, Wodak and Boukala Citation2015). Likewise, many have addressed the role of Wilders as a public figure, reflecting upon his choice of words (Kuitenbrouwer Citation2010, Landtsheer et al. Citation2011); rhetorical ‘framing’ (de Bruijn Citation2011, Rensen Citation2011); ‘charisma’ (Aalberts Citation2012, p. 29–32); and displays of self-confidence, unconventionality, and strong leadership (van der Pas et al. Citation2013; de Vries et al. Citation2017). However, the interrelations between Wilders’ nationalist thought and the affective qualities of his political persona are yet to be thoroughly investigated: How does Wilders, as a public figure, embody the nationalist sentiments of his party and politics?

Offering an answer to this question, we suggest, can provide new insights into Wilders’ continuing appeal. Whilst several political, economic, and demographic scenarios have been put forward to explain his success (e.g., Vossen Citation2010, van Kessel Citation2011, Aalberts Citation2012, Lucardie and Voerman Citation2013), it seems ultimately impossible to single out any particular political or economic success factor, especially considering both the wide variety in age, class background, and political preferences of Wilders’ electorate (Aalberts Citation2012, p. 34–5, Vossen Citation2013, p. 223–58), and his party’s remarkable combination of right-wing standpoints on immigration and public security, yet left-wing views on, for example, social security, women’s rights, and same-sex marriage (Aalberts Citation2012, p. 18–20). However, several scholars have argued that Wilders’ voters often express comparable sentiments: growing concerns about the impact of transnational developments such as immigration, globalisation, and European integration (Pels Citation2011, Vossen Citation2013, p. 245); dissatisfaction with traditional party politics (Aalberts Citation2012, 33); and the feeling that Wilders alone is able to ‘shake up’ the Dutch parliamentary system (Aalberts Citation2012, p. 50–55, Vossen Citation2013, p. 253).

Following this argument, we propose that Wilders’ continuing appeal may be the result of his capacity to embody a certain affectively resonant form of Dutch national thought. Rather than focusing on his parliamentary politics, we explore this possibility by analysing his self-stylisation – the rhetorical and discursive crafting of his public persona – and argue that it is shaped by (1) a selective use of national imagery to bolster national ‘selfhood through historical remembrance and cultural memory’ (Leerssen Citation2007, p. 29); and (2) a process of personalisation (van Zoonen Citation2005, p. 69–86) through which Wilders projects the persona of an authentic political outsider and true voice of the Dutch people.

Although we limit our focus to Wilders, we do not consider him as an exceptional or idiosyncratic case, nor his success as based on extraordinary personal or rhetorical capacities, which would entail a double reduction of the complex and widespread rise of populism. Indeed, Oudenampsen (Citation2018) classifies Wilders as but one of several Dutch ‘translators’ of the ideological tradition of the New Right (see also Oudenampsen Citation2016). Therefore, an analysis of Wilders’ self-stylisation and authenticating persona has a relevance beyond the single case. Moreover, we believe that the joint perspective of imagology and celebrity studies offers insights that can help to gain a deeper understanding of conservative, nationalist, and populist politicians with an effective personal presence in public debates, both within and beyond the Netherlands.

Our analysis consists of two stages. First, we invoke insights from imagology in order to map the national thought informing Wilders’ understanding of Dutch culture and national identity. However, an imagological classification alone cannot capture succinctly the ‘mood’ or the feelings evoked by the national stereotypes used. Therefore, in the second stage of our analysis, we turn to the domain of celebrity studies, allowing us to further investigate the ‘affective function’ (Wheeler Citation2013, p. 6) of Wilders’ celebrity in the organisation of his political interests.

Reconquering the Netherlands: Wilders’ images of ‘Dutchness’

Imagology offers useful tools and insights into the creation and dissemination of images of nationality and nation-states, revealing how such images effect, not only political thought and practice, but also everyday life, and in doing so, represent some of the most important constituents of modern societies.Footnote2 Initially, the field may seem poorly suited to the domain of celebrity politics, due to its often historical emphasis, and its frequent focus on cultural forms that may not at first seem particularly relevant to contemporary political culture (e.g., literature, poetry, theatre, and opera). However, we ague it is precisely this historical focus and transmedial character that provides its potential, as historicising contemporary politics sheds light upon the deployment of national images by contemporary politicians. By incorporating into the analysis relevant mass media images, we can trace and analyse the similarities between the cultural processes of (early) modern nation-building and the role national imagery plays in contemporary celebrity politics.

Imagological research has shown that two processes are fundamental to the construction of national images (Leerssen Citation2006, p. 17). The first is the process of Othering, in which auto- (self) and hetero- (other) images (Leerssen Citation2006, p. 27) are created, the differences between which are subsequently geographically mapped. Various peoples are attributed with divergent cultures (and physiognomies), which are anchored in different spaces – e.g., North vs. South, East vs. West, ‘the mother country’ vs. ‘the colonies’, the capital vs. the periphery. This re-imagining of reality – as a collection of spatialised cultural differences – allows any group the ability to create and claim a specific identity. Subsequently, an appeal to this identity makes it possible to legitimise the maintenance of geographical, military, political, and administrative borders as cultural borders (Leerssen Citation2006).

Second, imagology reveals that such culturalised borders are always historically rooted. Images of homeland traditions and national history are revisited to give substance to what is conceived of as ‘inland’, ‘home’, or ‘our’ culture. One’s national auto-image, therefore, can be understood as a product of specific ways to imagine, represent, and (re)-appropriate the past. This process is akin to the famous ‘invention of tradition’ (Hobsbawn and Ranger Citation1983), as well as to the more recently conceptualised ‘formation of nativism’ (Duyvendak Citation2011). Acknowledging that national identities are primarily the result of interpretations – identifications, appropriations, and reifications – of historical events for political use, imagology does not offer a sociological or political analysis. Rather, it offers a deconstruction of such interpretations by contextualising them, first and foremost, in the field of culture. Cultural actors, audiences, and texts (in the broadest sense) do not simply represent or follow social and political reality, but rather have their own performative power.

Before we turn to Wilders’ use of national imagery, we first sketch the general contours of Dutch national thought. In existing imagological analyses of Dutch identity, a delimited set of auto- and hetero-images frequently returns (Krol Citation2007). Almost without exception, modern Dutch national imagery forms part of an ongoing reimagining of the time of the Dutch Revolt (1566–1648). This insurgence against the rule of King Philip II of Spain united in their discontent local noblemen and lower estates that came to call themselves ‘Beggars’ (Geuzen), originally under the leadership of William of Orange. What started as a dispute about religious freedom, taxation, and political representation, resulted in an extensive and complicated armed conflict that went down in history as the Eighty Years’ War between Spain and the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands. In 1581, the ‘Act of Abjuration’ (Acte van Verlatinghe) legitimised the Revolt against the imperial ruler. When the Treaty of Münster put an end to the conflict in 1648, the Dutch Republic was formally consolidated and separated from the Habsburg (South) Netherlands. The young Republic, spurred on by a Protestant ethic of hard work and modesty, prospered economically and culturally, and the period became known as the Dutch ‘Golden Age’.

The Dutch Revolt and its aftermath offered all the necessary ingredients for imagining the Republic as the first and original Dutch nation-state: a separate, hard-won territory; an internationally acknowledged sovereign state; economic wealth; a language and culture to be proud of; and heroic foundational battles, with William of Orange as the ‘Father of the Nation’ (Bloemendal Citation1999). Indeed, from the eighteenth century onwards, the Golden Age became the mythological age for the Netherlands (Blom and Lamberts Citation1999, van Sas Citation2004, Wils Citation2005, p. 77, Velema Citation2007). Over time, authors, artists, and politicians ensured that the Revolt came to be associated with particular values: a love for peace and freedom; a desire for equality; and a pride in collective resistance to authoritarian rule (Kloek Citation1999, p. 263, Meijer Drees Citation1999, p. 117, Krol Citation2007, p. 142). As images of the Dutch Revolt became ingrained in Dutch culture, these values came to be seen as the core qualities of the Dutch national character.

However, the central element that united all of these qualities was said to be the notion of tolerance. Tolerance has a long history of easing potential tensions between religion and state politics in various regions (Beller Citation2007). Within a Dutch context, it came to function as a pacifying form of resistance to power. It was considered to be an instrument with which to achieve peace and guarantee freedom and independence (Aerts Citation2001, Velema Citation1999, p. 6–7). Although its origins lay in a combination of a lack of centralisation, a societal politics of multiconfessionalism, and the pragmatic attitude of Dutch merchants (Kooi Citation2018), by the end of the twentieth century, the idea of tolerance was so pervasive in Dutch auto-images that for many, the Netherlands had become a country without a national character. Its culture was considered to be so tolerant that all ideologies, cultures, and identities could co-exist in peace and freedom, as long as there was room for public dialogue, consensus-seeking, and negotiation (Krol Citation2007).

Yet from the 1990s onwards, this paradox of a ‘typically Dutch’ absence of national character provided an arena for changing debates on Dutchness against the backdrop of immigration and multiculturalism. This time Dutchness was almost exclusively defined in terms of cultural and religious identity (van Reekum Citation2014), whilst the notion of tolerance itself seemed to silence discussions on immigrant integration (van Reekum Citation2016, p. 568). In this respect, the religiously motivated assassination of Theo van Gogh – a harsh public critic of Islam and the Dutch ideal of a multicultural, tolerant society – marked a turning point. Prominent critics argued that tolerance had degenerated into indifference and had thus lost its pacifying powers (Scheffer Citation2011, p. 118–23, van Dam et al. Citation2014). Subsequently, previously highly regarded notions such as tolerance, freedom, and equality were replaced by a polarising discourse of ‘tolerant no more’ (van Reekum Citation2016, p. 561–2, Kurth and Glasbergen Citation2017, p. 225–6). Within this discursive milieu, the capability and the right to speak publically about national identity itself became constitutive for Dutchness (van Reekum Citation2016). When Wilders entered the political stage in this new and complex setting, he did so with a discursive syncopation.

When we compare Wilders’ commitment to issues of national character with the above survey of imagological insights and Dutch auto-images, we can first of all confirm that the construction of such an identity starts with images of the Other – in Wilders’ case, with a considerable series of hetero-images. On the one hand, there are intra-national hetero-images. Wilders distances himself, for example, from the Dutch ‘political elite’ (Wilders Citation2005, p. 104), the ‘progressive elite’ (PVV Citation2012, p. 27), and the ‘multiculturalist establishment’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 192). He also frames several immigrant groups – ‘Moroccans’ (PVV Citation2010, p. 7), ‘Turks’, ‘Poles, Rumanians and Bulgarians’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 12), ‘citizens with double passports’ (Wilders Citation2005, p. 126) – as groups that do not belong in Dutch society. On the other hand, there are trans-national hetero-images, dissociating him from Brussels (PVV Citation2012) as the all too distant source of an uncontrollable techno-bureaucracy, as well as from economically struggling EU member countries such as Greece and Italy (Handelingen II, 2012, p. 4, 8). Whilst the Dutch live ‘according to [the traditional saying that] ‘frugality with diligence builds houses like castles’’, these ‘other cultures are more aimed at early retirement, avoiding taxes and enjoying your drink in the sun’ (PVV Citation2012, p. 13). What all these hetero-images have in common, is that spatial mapping (‘here’ vs. ‘there’) is coupled with cultural Othering (‘us’ vs. ‘them’): ‘we’, the authentic Dutch, stick to rationality, realism and the Protestant ethos of hard work and modesty, whilst ‘they’ uphold ‘foreign’ values and are (depending on the issue discussed) irrational, prejudiced, bureaucratic, prone to financial extravagance, politically correct, backwards, fanatic, imperialist, and so forth.

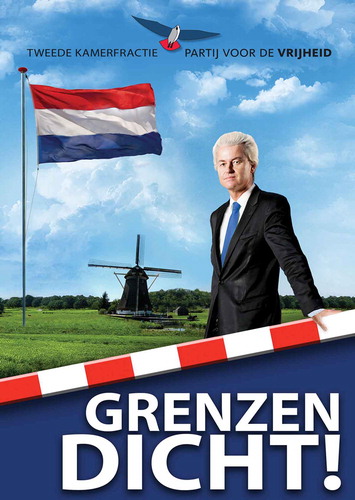

Secondly, contextualising Wilders’ performance allows us to map the process that accompanies patterns of Othering, namely, identification. Clearly, Wilders’ auto-images are firmly and explicitly embedded in Dutch culture and history. Some of the images are quite obvious. ‘Freedom’, for example, is prominent in his party’s name, and Wilders addresses his followers as ‘dear friends of freedom’ (PVV Citation2012, p. 7). Visually, the party’s communications tap into the familiar reservoir of Dutch images: the repeated use of a streaming Dutch flag; a flying seagull as party logo (in the colours of the Dutch flag); and typical Dutch landscapes (the hard-won polders, canals, and windmills) in the background of campaign leaflets (see ).

Figure 2. 'Close the borders!' Campaign folder, 2015, taken from www.pvv.nl. Reproduced with permission: Party for Freedom, 2017.

Furthermore, Wilders specifically foregrounds the importance of Dutch ‘sovereignty’ (PVV Citation2006b, Citation2012, p. 17, Wilders Citation2005, p. 113), thereby explicitly situating himself in the tradition of Dutch resistance to foreign rule. In his book Kies voor vrijheid: Een eerlijk antwoord (Choose for freedom: An honest answer), he compares his opposition to the existing political system to the Dutch Revolt:

At a turning point in the history of the Netherlands our ancestors have declared their independence by signing an act of abjuration (1581). By doing so, they abandoned their trust in a ruler who believed the people were there for him, instead of the other way around. (Wilders Citation2005, p. 128; italics in original)

Such a ‘Declaration of Independence’, Wilders (Citation2005, p. 128) concludes, is ‘required once again’ (see also PVV Citation2010, p. 5). Furthermore, Wilders refers to himself and his followers as ‘patriots’, evoking the eighteenth-century history of the Dutch patriots, who rose up against the rule of Stadtholder William V (PVV Citation2012, p. 10). In an implicit reference to World War II (1940–1945), the 2012 party manifesto mentions the example of Willem Drees, prime minister of the Netherlands between 1948 and 1958. Wilders rhetorically asks: ‘Why would [Drees] throw away the independence that we had only just reconquered with blood and tears?’ (PVV Citation2012, p. 10) Drawing upon the tradition of collective resistance against absolute rulers (e.g., Philip II, William V, or Nazi Germany) as a central building block of Dutch national identity, Wilders thus squarely situates himself within this tradition (Rensen Citation2011, p. 27, Vossen Citation2013, p. 79).

Additionally, Wilders’ cultural references – mostly taken from the time of the Revolt and the Dutch Golden Age – emphasise the assertive independence of the Dutch. One of the party’s manifestos, for instance, is entitled Een nieuwe Gouden Eeuw (A new Golden Age; PVV Citation2006a). In speeches, Wilders refers to Willem of Orange, Piet Heyn, and Michiel de Ruyter as the ‘heroes of the history of the fatherland’ (Vossen Citation2013, p. 85). When in 2010, he was invited by Veronica Magazine to pose as his personal hero, Wilders opted to be photographed as the Dutch Admiral De Ruyter (1607–1676), describing him as ‘one of the greatest heroes in our history. Warlike. Afraid of no one. He showed his fighting spirit in his battles with foreign armies and pirates’ (Veronica Citation2010, see ). On 9 August 2016, Wilders re-used the image in a tweet, now accompanied by the message ‘Reconquer the Netherlands’ (Wilders Citation2018a). Such self-identifying images summarise his agenda of resistance in distinctly militaristic metaphors, emphasising the violent origins of the Dutch Revolt.

Figure 3. 'Reconquer the Netherlands': Geert Wilders posing (with photographer William Rutten) in front of his portrait as Michiel de Ruyter. Reproduced with permission: AP Images/Hollandse Hoogte.

This historical contextualisation demonstrates that Wilders’ politics of ‘reconquering’ the Netherlands involves a redefinition of the notions of freedom and tolerance (see Rensen Citation2011). Whilst maintaining that ‘the Dutch are exceptionally civic, open, tolerant, culturally progressive and should be proud of their anti-collectivism’ (van Reekum Citation2012, p. 594; see also Kešić and Duyvendak Citation2016), his militant nationalism ‘[precisely] helps [him] to differentiate between Dutch and foreign, in particular, Islamic, culture’ (van Reekum Citation2012, p. 594). The notion of freedom thus no longer entails collective independence from foreign rule, but becomes defined in terms of socio-economic self-sufficiency and individual safety. Therefore, as Dick Pels (Citation2011, 39) suggests, Wilders’ populism can be characterised as a type of ‘prosperity chauvinism’ or ‘nationalist individualism’. As Wilders (Citation2005, p. 124) himself explained in an extensive, stylistically somewhat awkward passage:

For me, freedom is central. The freedom that allows your mother to go outside at night, the freedom to still have enough salary left to spend on your family, the freedom that you have because your pension is secured, the freedom that is there because our trade and industry are flourishing again, the freedom that you have because the government protects your family against terrorists, the freedom of a job and a decent life, the freedom to take our own decisions as a country.

Similarly, tolerance is reframed as constituting a less inclusive idea of freedom; as a distinctly, even exclusively ‘Dutch’ value that requires a certain intolerance to uphold: ‘We have always been tolerant in the Netherlands and have even gone so far as to tolerate the intolerant. We must learn to become intolerant to the intolerant. That is the only way to preserve our tolerance’ (Wilders Citation2005, p. 73; see also Kurth and Glasbergen Citation2017).

An imagological analysis reveals how Wilders not only ‘raises the question’ of Dutch identity (van Reekum Citation2016), but also fashions himself as the quintessential Dutchman by appropriating traditional national imagery – the Revolt, the Patriots, and the figure of Michiel de Ruyter. Via this self-stylisation, he positions himself as the guardian of the national character, and his political actions as authentically Dutch. This staging of national identity, however, is a highly selective and strategic performance, aimed at a particular sector of the electorate: Whilst foregrounding and reinterpreting national values such as freedom, resistance, and tolerance as exclusively ‘nativist’ qualities (Duyvendak Citation2011; see also Pels Citation2011, p. 35), values such as a love of peace, homeliness, pragmatism, modesty, and equality – although all equally associated with Dutch identity – remain unmentioned.

The authentic underdog: Wilders’ affective persona

Whilst illuminating Wilders’ self-stylisation in terms of national imagery and its transhistorical reappropriation, imagology cannot explain exactly what makes this performance so compelling. The strategic re-use of national auto- and hetero-images alone is not enough to ‘move’ the electorate: Wilders also needs to project a persona that stirs up emotions – hope, anger, grief, discontent, or self-confidence. Populism does not simply reflect (changing) attitudes of the electorate, its style and tone evoke a response as well (Oudenampsen Citation2013, p. 193).

Based on extensive interviews with Wilders’ followers, Aalberts (Citation2012, p. 50) concludes that they ‘let themselves be guided by their feelings’ rather than by familiarity with the party’s policies. They declare themselves to be ‘fans’ of the party leader and not so much of the party itself; they feel that Wilders possesses ‘exceptional qualities’, including an impressive rhetorical talent and a ‘sense of humour’; and cite the ‘effects of his appearance and statements’ (Aalberts Citation2012, p. 55, 69). Factoring Wilders’ style and personality into his appeal, we now turn to celebrity studies – a field that has extensively researched the role of affective embodiment in the political domain.

The celebritisation of the political domain has transformed political leaders into media personalities similar to entertainment celebrities (Marshal Citation1997, p. 203–40, Street Citation2004, van Zoonen Citation2005, p. 69–86, Wheeler Citation2013, p. 87–113). Playing to the increasing interest that audiences have in the personalities and private lives of public figures, they project a specific persona – a carefully constructed public self that allows them to navigate between the private, political, and public spheres (Corner Citation2003, 72–3). Moreover, this public self is a means of realising ‘emotional work’, allowing politicians to tap into the electorate’s feelings and ‘move’ voters in particular ways (Nunn and Biressi Citation2010, p. 50, 54). What makes some politicians true celebrities, is that they have an ‘affective function’ in the ‘organization of interests and issues’: they are ‘means and methods of housing affective power’ (Marshal Citation1997, p. 204, 199).

Insights into the performative nature of celebrity politics are particularly relevant to an analysis of Wilders, because his party can be considered a ‘one-man show’. The Party for Freedom is ‘a party in name only’, as it formally has only one member, namely, Wilders himself (van der Pas et al. Citation2013, p. 459, Vossen Citation2013, p. 178). Therefore, ‘[w]ith no members or organizational structure’, the ‘leader without a party’ depends heavily ‘on the mass media in order to attract electoral support’ (van der Pas et al. Citation2013, p. 459).

Wilders (Citation2005, p. 106) main persona is that of a political outsider who intends to ‘fight the [political] elite on all fronts’, as in his opinion the traditional political system ‘takes care only of itself and has isolated itself from society’ (p. 128). Promising his party ‘will stay clear of party-political and power games, which in the end only fool the voter’ (PVV Citation2006b), Wilders (Citation2012, p. 175) describes the Party for Freedom explicitly as ‘an anti-establishment party’, repeatedly distancing himself from the Dutch parliament by labelling it a ‘joke’ and ‘bogus parliament’ (Handelingen II 2015, p. 6, 51). As the anti-EU performance on Luxembourg Square illustrates, Wilders performed the cutting ritual standing directly outside the European Parliament building – as a true outsider.

As adopting the position of the underdog and voicing anti-establishment opinions is a familiar move within celebrity politics and populist movements, Wilders’ self-stylisation as a political outsider is not exceptionally appealing or compelling per se. In her discussion of celebrity politicians, van Zoonen (Citation2005, p. 83) observes that ‘the resulting growing separation of the political field from everyday lives and experience makes politics susceptible to the intervention of outsiders whose promise invariably is that they will bring politics back to the ‘ordinary man’’. Albertazzi and McDonnell (Citation2008, p. 4–5) argue that populism in general is characterised by the conviction that a political elite has distorted or neglected the will of the common people, who must be ‘given back their voice and power by the populist leader’ – often an outsider or even an ‘anti-politician’ (see also Heinisch Citation2008). Yet in Wilders’ case, this conventional form of populist self-presentation could potentially be perceived as insincere, as he has been a member of the Dutch Lower House for almost two decades. Such an insider position could easily undermine his claim to be an exception to the (political) rule.

However, by ‘persona-lizing’ (van Zoonen Citation2005, p. 72) his politics, Wilders attempts to dispel any doubts about the urgency of his politics and the sincerity of his populist stance. Marshal (Citation1997, p. 231) observes that, in order to appear authentic, a ‘politician must maintain the conception of a continuity between the public presentation of self and images of the private self’, necessitating careful disclosure of details about that private self. Thus, for Wilders, the creation of a persona that effectively embodies the nationalist sentiments of his party could both make his politics emotionally compelling, and authenticate his position as the quintessential outsider. Therefore, Wilders employs a cluster of affective strategies, suggesting an intimate knowledge of the electorate; cultivating a sense of isolation; aligning his politics and personality; and creating a matching online persona.

First, Wilders projects a persona that is very much ‘in touch’ with the concerns of Dutch citizens. Again, national auto-images are employed, affectively charged and inviting an emotional response. For example, Wilders defines ‘the people’ as comprising ‘common’, ‘hardworking people’’ (Wilders Citation2005, p. 131), who want to feel ‘proud of this country again’ (PVV Citation2006b). The political establishment, however, has ‘sold out’ its ‘own Dutch identity’ (Wilders Citation2005, p. 112), whilst ‘the Dutch people’ supposedly have to cough up money – for the EU, for bailout loans to Greece, and for foreign aid, etc. (PVV Citation2012, p. 50). Here, Wilders appeals to national images (the Protestant ethic of hard work and modesty) whilst inviting an emotional response in the form of anger, outrage, or a sense of unfairness. In 2008, Wilders introduced ‘Henk and Ingrid’ – a fictitious, ‘very ordinary’ couple with ‘typical’ Dutch names that functions as a pars pro toto for the people (PVV Citation2010, Citation2012, Vossen Citation2013, p. 223, Handelingen II Citation2018, p. 2, 53). This ensures that Wilders’ observations about the deplorable state of affairs in Dutch politics become highly personal – ‘the Greek pour themselves another ouzo with thanks to Henk and Ingrid’ (PVV Citation2012, p. 13) – implying Wilders knows his potential voters intimately.

A second strategy that allows Wilders to combine national images with emotional work is by drawing attention to his political and personal isolation. Already in 2002, Wilders (Citation2005, p. 143) claimed he had become ‘isolated’ within the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy because of his opinions, further stating that, after his break with the party, ‘I found myself on my own’ (42). His isolation would soon take on very real forms, as the aftermath of the assassination of Theo Van Gogh forced him to live in military safe houses, making a normal social life practically impossible. Wilders incorporates these details into his public self-stylisation by describing his life in safe houses in detail and circulating his own images of his temporary quarters in Camp Zeist (Wilders Citation2005, p. 48–9, Citation2012, p. 22, EuroTrump Citation2017), making his isolation a symbol of steadfastness and endurance. Subsequently, being alone and isolated is reframed in the party’s official statements as a form of independence. In a 2008 campaign advertisement, for instance, the electorate is presented with a two-and-a-half-minute long voice-over shot of Wilders, seen mostly from the back, completely alone, standing on a windy Dutch beach, gazing over the surf (PVV Citation2008). On a similar note, the party repeatedly claims in its 2012 election manifesto:

We are the only ones who say: let us break loose from this snare […] We are the only ones who say to the unelected Eurocrats: your ending is our beginning […]. We are the only ones who say: it has to stop. (PVV Citation2012, p. 14)

This rhetorical reframing of solitude affirms the connection between Wilders’ persona and national ideals of self-rule and resistance to outside forces, but this time these ideals become affectively charged. Wilders’ political persona brings with it a ‘mood’ of isolation, partly enforced, partly self-inflicted, inviting our admiration and sympathy.

Via a third strategy, Wilders authenticates his persona by presenting his political attitude as flowing naturally from his character traits. This is achieved predominantly through extended sections of autobiographical writing in his two published books. In Choose for Freedom, Wilders (Citation2005, p. 35) writes: ‘It is not my nature […] to hold back, nor to renounce the electorate out of self-interest.’’ Whilst, in Marked for Death, he adds: ‘I am stubborn. The harder people make it for me, the more I persist’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 140). The natural link between personality and politics is further strengthened as Wilders roots his political convictions in personal experiences. As ‘a rebellious, difficult kid’, he grew up in Limburg, where people ‘have a strong sense of identity stemming from their attachment to their land, their traditions, and their faith’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 31; see also EuroTrump Citation2017). Travelling through Israel and Egypt as an eighteen-year-old, he witnessed ‘brutal oppression by non-democratic leaders’ (Wilders Citation2005, p. 14) and the ‘vitriolic hatred’ (Wilders Citation2012, 80) against Jews first hand (see also Wertheim Citation2017), and has ‘an important revelation’: the Middle East’s failure to ‘progress like the rest of the world’ is the fault of its ‘culture’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 54). After his return to Netherlands, he was violently mobbed by ‘three Arab youths’ that had followed him ‘like predators tracking their prey’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 139). He also recounts how his life changed drastically after the murder of Van Gogh ‘for the crime of offending Islam’ in 2004: ‘I live in a government safe house, heavily protected and bullet proof […]. I have not walked the streets on my own in more than seven years’ (Wilders Citation2012, p. 4). This extensive personalisation implies that the elements that make up Wilders’ political agenda – reclaiming regional or national heritage and identity; ‘de-Islamisation’; reducing street crime; putting a halt to immigration; and defending freedom of speech – are not merely populist showpieces, but authentic concerns, originating from personal experience.

Finally, Wilders supplements this autobiographical and emotional work with the use of an affectively charged online persona. Whilst there has been some academic attention paid to Wilders’ use of social media, describing it as ‘impersonal’ (Theunissen Citation2012, p. 42); a ‘vehicle for issuing a ‘call to action’’ (Blancquart and Cook Citation2013, p. 7); and a tool for ‘antagonistic messaging’ (van Kessel and Castelein Citation2016, Gonawela et al. Citation2018) and ‘double differentiation’ (suggesting inclusion in, and exclusion from, the political establishment; Groshek and Engelbert Citation2013), little attention has been paid to the affective dimension of his online persona. Specifically, this is achieved through references to Dutch popular culture and self-reflexive media puns. Nationalist pride, for instance, shines through in Wilders (Citation2018a) tweets about Dutch culture: he praises the Dutch astronaut Wubbo Ockels for bringing ‘the Netherlands to great heights’ (14 May 2014); celebrates the controversial national tradition of ‘Black Pete’ (5 December 2018); tweets a picture of his dinner with the caption ‘Dutch fare. Nothing tastes better’ (4 November 2018); and makes a point of congratulating only the Dutch 2016 Olympic medallists (August 15–16, 2016).

In another affectively charged tweet, Wilders (Citation2018a) posted a screen shot of a non-existent app entitled ‘Minder’, adding: ‘Get minder!:)’ (5 August 2016). The post plays on the name of the popular dating app Tinder and the Dutch word ‘minder’ (‘fewer’), thereby implicitly repeating his controversial 2014 public plea for ‘fewer’ Moroccans, which led him to be tried for – and found guilty of – inciting discrimination (Siegal Citation2016). The tweet is an example of Wilders’ habit of ridiculing any criticism raised against him by simply repeating and often exaggerating his controversial statements – a strategy he repeated in early 2016, when journalists exposed his second, anonymous Twitter account, via which he followed a Dutch porn star and a dozen Donald Duck accounts (RTL Citation2016). Soon after the story broke, Wilders (Citation2018b) posted on the anonymous account: ‘Our parliament is one big joke. Things are much better arranged in Duckburg,’ thus effectively pre-emptying any further criticism. Whether these posts are brilliantly funny or just shallow and tasteless, is something about which the Dutch Twitter community clearly disagrees, yet the number of comments demonstrates that, either way, their affective impact is undeniable.

Through these affective and emotional strategies, Wilders supplements the logos of national identity with an ethos of authenticity and a pathos of urgency, enabling him to embody the sentiments of his party. The politician thus not only brands his nationalist-populism as typically Dutch, but also evokes and taps into the ‘affective atmosphere’ of nationalism (Stephens Citation2015). Interviews with voters suggest that he succeeds in doing so: voters describe ‘Geert’ as someone who combines ‘will power with toughness’, ‘who speaks the language of the people’, ‘has the guts to speak his mind’, and ‘knows how to move you’ with his ‘language’ and ‘sense of humour’ (Aalberts Citation2012, p. 52–68). These perceived qualities resonate with the values foregrounded by Wilders’ persona: affinity with the common man, strong-willed independence, fearless candour, bitter sarcasm, and the angry determination of the underdog.

Conclusion

An imagological approach to contemporary politics supplemented with insights from celebrity studies offers valuable insights into the appeal of Wilders and his party. By analysing national images and their transhistorical appropriations, we have mapped the recurring cluster of auto-images of the Dutch Revolt and the Golden Age as foundational to his nationalist-populist stance. These images allow him to position himself in the tradition of collective and even violent resistance, and to authenticate his political attitude as fully in line with the Dutch national character. In the process, he appropriates notions such as freedom and tolerance, redefining them as exclusive – and excluding – properties of nativist culture. Using complementary insights from celebrity studies, we have demonstrated that this self-stylisation also involves a form of emotional work. Wilders projects an affectively charged public self that ‘moves’ his audience and lends both a sense of urgency and a feeling of authenticity towards his political persona.

Although Wilders’ political style is characterised by a local Dutch ‘inflection’, it shares many similarities with the style of other celebrity politicians, such as Donald Trump (Street Citation2018).Footnote3 At the same, an analysis of Wilders’ personalisation distinguishes his style from that of younger right-wing politicians from the Netherlands as elsewhere. Key figures such as Thierry Baudet from the Dutch Forum for Democracy, Bart de Wever from the New-Flemish Alliance, and Alternative for Germany’s Björn Höcke take a more intellectualist stance and articulate a high-cultural conservatism, differing sharply from Wilders’ more popular nationalism. Baudet, for instance, has created a distinct political persona of his own by addressing Dutch parliament in in Latin and working lines of contemporary poetry into his speeches (Faber Citation2018) – elements that would certainly not fit with Wilders’ repertoire. Intriguingly, however, Baudet’s politics remain ideologically compatible with Wilders’, up to the point that they can be said to compete for the same section of the electorate. This seems to confirm that, within celebrity politics, ‘moving’ voters is not so much a matter of making ideological choices, but rather of cultivating personalised differences.

Finally, returning to his performance on Luxembourg Square, we can conclude that in Wilders (Citation2012, p. 216) nationalist thought, a transnational flag is an oxymoronic idea that by definition symbolises a threat to liberty: ‘The peoples of the free world […] can defend their liberties only if they can rally around a flag with which they identify. This flag, symbolizing ancient loyalties, can only be the flag of our nation.’ Thus, it was not the attack on the flag itself that was remarkable, but the truly performative nature of the act – not least because there is no historical, vexillological, or otherwise traditional relation between the individual stars and the constituting EU member states (Bruter Citation2004, p. 30, Shore Citation2013, p. 47). By shredding the flag and symbolically identifying one of its stars as ‘Dutch’ (NOS Citation2014), Wilders performatively projected the Netherlands as a nation with a single, separate, (literally) clear-cut identity and, by proxy, himself as a grim version of Michiel de Ruyter; the sole arbiter and lone defender of the Netherlands. With Dutch identity still a core issue in the political and public debate (van Holsteyn Citation2018), this persona is likely to remain both appealing and effective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gaston Franssen

Dr. Gaston Franssen is assistant professor of Literary Culture at the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He co-edited the volumes Celebrity Authorship and Afterlives in English and American Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); and Idolizing the Author: Literary Celebrity and the Construction of Identity, 1800 to the Present Amsterdam University Press, 2017). Recently, he has published on celebrity and authenticity (Celebrity Studies, 2019) and celebrity health narratives (European Journal of Cultural Studies, 2020).

Jan Rock

Dr. Jan Rock is assistant professor of Modern Dutch Literature at the University of Amsterdam and works for SPIN, the Study Platform on Interlocking Nationalisms. Rock’s research interests include the history of cultural nationalism and scholarship in the Netherlands and Belgium. He has contributed to R. Bod, J. Maat & T. Weststeijn (eds.), The Making of the Humanities, vol. 3: The Modern Humanities (Amsterdam University Press, 2014), T. van Kalmthout & H. Zuidervaart (eds.), The Practice of Philology in the Nineteenth-Century Netherlands (Amsterdam University Press, 2015), and the journal Science in Context.

Notes

1. All translations from Dutch are by the authors. We would like to thank Neil Ewen and David Zeglen as well as the Celebrity Studies reviewers for their help and comments.

2. For more on this field, see Beller and Leerssen (Citation2007) and the online database Imagologica.eu.

3. Indeed, after Trump won the Presidential Election in 2016, CNN labelled Wilders ‘Holland’s Donald Trump’ (Robertson Citation2016).

References

- Aalberts, C., 2012. Achter de PVV: Waarom burgers op Geert Wilders stemmen. Delft: Eburon.

- Aerts, R., 2001. Living apart together: Verdraagzaamheid in Nederland sinds de negentiende eeuw. In: M. ten Hooven, ed. De lege tolerantie: over vrijheid en vrijblijvendheid in Nederland. Amsterdam: Boom, 60–79.

- Albertazzi, D. and McDonnell, D., eds., 2008. Twenty-first century populism: the spectre of Western European democracy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Beller, M., 2007. Toleration/Intolerance. In: M. Beller and J. Leerssen, eds. Imagology: the cultural construction and literary representation of national characters. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 437–441.

- Beller, M. and Leerssen, J., eds., 2007. Imagology: the cultural construction and literary representation of national characters. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Blancquart, G. and Cook, D., 2013. Twitter influence and cumulative perceptions of extremist support: a case study of Geert Wilders. Research paper. Available from: http://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=act. [Accessed 1 Dec 2018].

- Bloemendal, J., 1999. Rond de Vader des Vaderlands: Oranje, Heinsius en Leiden. In: K. Enenkel, S. Onderdelinden, and P.J. Smith, eds. Typisch Nederlands”: De Nederlandse identiteit in de letterkunde. Voorthuizen, the Netherlands: Florivallis, 11–25.

- Blom, J. and Lamberts, E., 1999. History of the low countries. New York: Berghahn.

- Bruter, M., 2004. On what citizens mean by feeling ‘European’: perceptions of news, symbols and borderless-ness. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 30 (1), 21–39. doi:10.1080/1369183032000170150

- Corner, J., 2003. Mediated persona and political culture. In: J. Corner and D. Pels, eds. Media and the restyling of politics: consumerism, celebrity and cynicism. London: Sage, 67–84.

- de Bruijn, H., 2011. Geert Wilders speaks out: the rhetorical frames of a European populist. The Hague: Eleven International Publishing.

- de Vries, R.E., et al. 2017. Politieke persoonlijkheden: Perceptie van de publieke persoonlijkheid van partijleiders uit de Nederlandse politiek voorafgaand aan de 2017 Tweede Kamer-verkiezingen. Research report. Available from: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/political-personalities-perception-of-the-public-personality-of-d. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Duyvendak, J.W., 2011. The politics of home: belonging and Nostalgia in Europe and the United States. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- EuroTrump, 2017. Documentary. Directed by S. R. Morse. London: Observatory.

- Faber, S., 2018. Is dutch bad boy Thierry Baudet the new face of the European alt-right? The Nation, April 30-May 7. Available from: https://www.thenation.com/article/is-dutch-bad-boy-thierry-baudet-the-new-face-of-the-european-alt-right. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Gonawela, A., et al., 2018. Speaking their mind: populist style and antagonistic messaging in the tweets of Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, Nigel Farage, and Geert Wilders. Computer supported cooperative work, 27 (3–6), 293–326. doi:10.1007/s10606-018-9316-2

- Groshek, J. and Engelbert, J., 2013. Double differentiation in a cross-national comparison of populist political movements and online media uses in the United States and the Netherlands. New media and society, 15 (2), 183–202. doi:10.1177/1461444812450685

- Handelingen II, Handelingen der Tweede Kamer [Online transcripts]. (1995-present). Available from: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/zoeken/parlementaire_documenten. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Heinisch, R., 2008. Austria: the structure and agency of Austrian populism. In: D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell, eds. Twenty-first century populism: the spectre of Western European democracy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 67–83.

- Hobsbawn, E. and Ranger, T., eds., 1983. The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Kešić, J. and Duyvendak, J.W., 2016. Anti-nationalist nationalism: the paradox of dutch national identity. Nations and nationalism, 22 (3), 581–597. doi:10.1111/nana.12187

- Kloek, J.J., 1999. Vaderland en letterkunde. In: N. van Sas, ed., Vaderland: Een geschiedenis van de vijftiende eeuw tot 1940. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 237–274.

- Kooi, C., 2018. Religious tolerance. In: G. Janssen and H. Helmers, eds. The cambridge companion to the dutch golden age. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 208–223.

- Krol, E., 2007. Dutch. In: M. Beller and J. Leerssen, eds. Imagology: the cultural construction and literary representation of national characters. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 142–145.

- Kuitenbrouwer, J., 2010. De woorden van Wilders & hoe ze werken. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

- Kurth, L. and Glasbergen, P., 2017. The influence of populism on tolerance: a thematic content analysis of the dutch Islam debate. Culture and religion, 18 (3), 212–231. doi:10.1080/14755610.2017.1358194

- Landtsheer, C., Kalkhoven, L., and Broen, L., 2011. De beeldspraak van Geert Wilders, een Tsunami over Nederland? Tijdschrift voor communicatiewetenschap, 39 (4), 5–21.

- Leerssen, J., 2006. National thought in Europe: a cultural history. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Leerssen, J., 2007. Imagology: history and method. In: M. Beller and J. Leerssen, eds. Imagology: the cultural construction and literary representation of national characters. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 17–32.

- Lucardie, P. and Voerman, G., 2013. Geert Wilders and the party for freedom: a political entrepreneur in the polder. In: K. Grabouw and F. Hartleb, eds. Exposing the demogogues: right-wing and national populist parties in Europe. Brussel: Centre for European Studies & Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 187–204.

- Marshal, P.D., 1997. Celebrity and power: fame in contemporary culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Meijer Drees, M., 1999. Vechten voor het vaderland’ in de literatuur, 1650–1750. In: N. van Sas, ed. Vaderland: Een geschiedenis van de vijftiende eeuw tot 1940. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 109–142.

- NOS, 2014. Wilders knipt ster uit vlag Europa. Available from: http://nos.nl/artikel/650299-wilders-knipt-ster-uit-vlag-europa.html. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Nunn, H. and Biressi, A., 2010. A trust betrayed: celebrity and the work of emotion. Celebrity studies, 1 (1), 49–64. doi:10.1080/19392390903519065

- Otjes, S. and Louwerse, T., 2015. Populists in parliament: comparing left-wing and right-wing populism in the Netherlands. Political studies, 63 (1), 60–79. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12089

- Oudenampsen, M., 2013. Explaining the swing to the right: the dutch debate on the rise of right-wing populism. In: R. Wodak, M. KhosraviNik, and B. Mral, eds. Right-wing populism in Europe. London: Bloomsbury, 191–208.

- Oudenampsen, M., 2016. Deconstructing Ayaan Hirsi Ali: on Islamism, neoconservatism, and the clash of civilisations. Politics, religion & ideology, 17 (2–3), 227–248. doi:10.1080/21567689.2016.1232195

- Oudenampsen, M. 2018. The conservative embrace of progressive values: on the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in dutch politics. PhD diss. Tilburg University, The Netherlands.

- Pels, D., 2003. Aesthetic representation and political style: re-balancing identity and difference in media democracy. In: J. Corner and D. Pels, eds. Media and the restyling of politics: consumerism, celebrity and cynicism. London: Sage, 41–66.

- Pels, D., 2011. Het volk bestaat niet: Leiderschap en populisme in de mediademocratie. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

- PVV, 2006a. Een nieuwe Gouden Eeuw. Available from: https://www.pvv.nl/index.php/30-visie/publicaties/703-een-nieuwe-gouden-eeuw.html. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- PVV, 2006b. Klare wijn. Available from: http://www.pvv.nl/index.php/component/content/article/30-publicaties/706-klare-wijn.html0. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- PVV, 2008. PVV Spotje zendtijd voor politieke partijen. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgwVlewo17w. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- PVV, 2010. De agenda van hoop en optimisme: Een tijd om te kiezen: PVV 2010–2015. Available from: https://www.parlement.com/9291000/d/2010_pvv_verkiezingsprogramma.pdf. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- PVV, 2012. Hún Brussel, óns Nederland. Available from: https://www.pvv.nl/images/stories/verkiezingen2012/VerkiezingsProgramma-PVV-2012-final-web.pdf. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Rensen, M., 2011. Geloven in Nederland: de PVV-retoriek in het debat over de nieuwe nationale identiteit. In: J. Verheijen and J. Bekkenkamp, eds. Onszelf voorbij: over de grenzen van verbondenheid. Almere, the Netherlands: Parthenon, 23–49.

- Robertson, N., 2016. Geert Wilders: why voters are flocking to the dutch trump. Available from: http://edition.cnn.com/2016/12/14/europe/geert-wilders-holland-robertson/. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- RTL, 2016. Van Donald Duck tot Kim Holland: Wilders’ stiekeme Twitteraccount. Available from: http://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/politiek/van-donald-duck-tot-kim-holland-wilders-stiekeme-twitteraccount. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Scheffer, P., 2011. Immigrant nations. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Shore, C., 2013. Building Europe: the cultural politics of European integration. London: Routledge.

- Siegal, N., 2016. Geert Wilders, dutch far-right leader, is convicted of inciting discrimination. The New York Times, 9 Dec.

- Stephens, A.C., 2015. The affective atmospheres of nationalism. Cultural geographies, 23 (2), 1–18.

- Street, J., 2004. Celebrity politicians: popular culture and political representation. The British journal of politics and international relations, 6 (4), 435–452. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2004.00149.x

- Street, J., 2018. What is Donald Trump? Forms of ‘celebrity’ in celebrity politics. Political studies review, 1–11. [Accessed 1 December 2018]. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918772995

- Taggart, P. and Szczerbiak, A., 2013. Coming in from the cold? Euroscepticism, government participation and party positions on Europe. JCMS: journal of common market studies, 51 (1), 17–37.

- Theunissen, A., 2012. Political transparency in the media: the old media’s influence on politicians’ Twitter behaviour. MaRBLe. Available from: http://openjournals.maastrichtuniversity.nl/Marble/article/download/118/68. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- van Dam, P., Mellink, B., and Turpijn, J., 2014. Inleiding. In: P. Dam, B. van Mellink, and J. Turpijn, eds. Onbehagen in de polder: Nederland in conflict sinds 1795. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 7–21.

- van Holsteyn, J., 2018. The dutch parliamentary elections of March 2017. West European politics, 41 (6), 1364–1377. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1448556

- van Kessel, S., 2011. Explaining the electoral performance of populist parties: the Netherlands as a case study. Perspectives on European politics and society, 12 (1), 68–88. doi:10.1080/15705854.2011.546148

- van Kessel, S. and Castelein, R., 2016. Shifting the blame: populist politicians’ use of Twitter as a tool of opposition. Journal of contemporary European research, 12 (2), 594–614.

- van der Pas, D., de Vries, C., and van der Brug, W., 2013. A leader without a party: exploring the relationship between Geert Wilders’ leadership performance in the media and his electoral success. Party politics, 19 (3), 458–476. doi:10.1177/1354068811407579

- van Reekum, R., 2012. As nation, people and public collide: enacting dutchness in public discourse. Nations and nationalism, 18 (4), 583–602. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2012.00554.x

- van Reekum, R., 2014. Out of character: debating dutchness, narrating citizenship. PhD diss. University of Amsterdam.

- van Reekum, R., 2016. Raising the question: articulating the dutch identity crisis through public debate. Nations and nationalism, 22 (3), 561–580. doi:10.1111/nana.12154

- van Sas, N., 2004. De metamorfose van Nederland: van oude orde naar moderniteit 1750–1900. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- van Zoonen, L., 2005. Entertaining the citizen: when politics and popular culture converge. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Velema, W., 1999. Het Nederlandse vrijheidsbegrip: Ter inleiding. In: E. Haitsma Mulier and W. Velema, eds. Vrijheid: Een geschiedenis van de vijftiende tot de twintigste eeuw. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1–10.

- Velema, W., 2007. Republicans: essays on eighteenth-century dutch political thought. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill.

- Veronica, 2010. Heroes: Geert Wilders als Michiel de Ruyter. Veronica Magazine, 10 June. Available from: https://www.veronicamagazine.nl/entertainment/backstage/128-geert-wilders-als-michiel-de-ruyter. [Accessed 18 August 2016].

- Vossen, K., 2010. Populism in the Netherlands after Fortuyn: Rita Verdonk and Geert Wilders compared. Perspectives on European politics and society, 11 (1), 22–38. doi:10.1080/15705850903553521

- Vossen, K., 2011. Classifying Wilders: the ideological development of Geert Wilders and his party for freedom. Politics, 31 (3), 179–189. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2011.01417.x

- Vossen, K., 2013. Rondom Wilders: Portret van de PVV. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Vossen, K., 2016. The dutch whistleblower: Geert Wilders as figurehead of international anti-Islam alarmism. In: J. Jamin, ed. L’extrême droite en Europe. Liège: Bruylant, 65–72.

- Wertheim, D., 2017. Geert Wilders and the national-populist turn toward the Jews in Europe. In: D. Wertheim, ed. The Jew as legitimation: Jewish-gentile relations beyond antisemitism and philosemitism. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 275–289.

- Wheeler, M., 2013. Celebrity politics: image and identity in contemporary political communications. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Wilders, G., 2005. Kies voor vrijheid: Een eerlijk antwoord. Den Haag: Groep Wilders.

- Wilders, G., 2012. Marked for death: Islams’ war against the west and me. Washington: Regnery.

- Wilders, G., 2018a. Twitter account Geert Wilders. Available from: https://mobile.twitter.com/geertwilderspvv. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Wilders, G., 2018b. Twitter account Willie Geerens. Available from: https://mobile.twitter.com/zip15nl_frank. [Accessed 1 December 2018].

- Wils, L., 2005. Van Clovis tot Di Rupo: De lange weg van de naties in de Lage Landen. Antwerpen: Garant.

- Wodak, R. and Boukala, S., 2015. European identities and the revival of nationalism in the European Union: a discourse historical approach. Journal of language and politics, 14 (1), 87–109.