ABSTRACT

Focusing on the chess prodigy Samuel Reshevsky (1911–1992), this paper examines the international commercial exploitation of child prodigies and their rise to celebrity. In the early 1920s, this boy wonder toured Europe and the United States, where he defeated some of the best players in simultaneous chess exhibitions, met important personalities and became a subject of global fascination. His ascent into stardom just before Hollywood’s child star era reveals the public’s eagerness to capitalise on gifted children as yet another commodity of the entertainment industry. Parents played a key role in exploiting child prodigies, despite the success of recent campaigns to secure children’s rights such as compulsory education and the regulation of child labour. Meanwhile, philanthropists attempted to aid children like Reshevsky and stop their public exhibition. Moreover, psychologists examined their talent and worried about their futures. Overall, Reshevsky’s case reconstructs the network of interests (commercial, humanitarian, scientific) surrounding child prodigies and historicises the child star phenomenon beyond the mainstream child performer.

Celebrity and the child prodigy phenomenon

To achieve world-wide fame at the age of eight is a mixed blessing. Such was my lot in life. I was a ‘chess prodigy’, and my childhood, from the time I left my native Poland in 1920, consisted of a series of public exhibitions throughout Europe and the United States. Wherever I went, great crowds turned out to see me play. For four years, I was on public view. People stared at me, poked at me, tried to hug me, asked me questions. Professors measured my cranium and psycho-analysed me. Reporters interviewed me and wrote fanciful stories about my future. Photographers were forever aiming their cameras at me. (Reshevsky Citation1948, p. 1)

With these words, Samuel Reshevsky (1911–1992), formerly Szmul Rzeszewski (), opened the preface of his book Reshevsky on Chess (Citation1948), where he reviewed several of his most famous games. This book is assumed to be ghost-written, and although Reshevsky (Citation1991) and other chess experts denied this, it is plausible that the manuscript was heavily edited. At the time the book appeared, the former Polish child prodigy was an established American chess grandmaster, but his past as a chess wonder in the early 1920s was still well remembered. The cited quotation highlights several elements of interest to this paper. First, it elucidates the double role of child prodigies as child stars and scientific subjects. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these two phenomena were closely intertwined. For child prodigies, becoming celebrities meant travelling to display their talents in Europe and America, which in turn, facilitated their examination by experts and learned societies. Journalists were largely responsible for labelling these children as prodigies before scientists took an interest in them. They pinpointed characteristics such as their astonishing precocity and their allegedly innate genius, two factors that were frequently submitted to psychological examination.

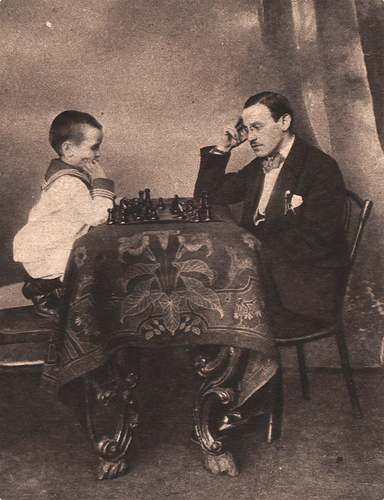

Figure 1. Samuel Reshevsky at five years old. In Das interessante Blatt, 13 September 1917. Courtesy of ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

Another element of interest to this paper, which also appears in Reshevsky’s quotation, is the social concern that surrounds the future of child prodigies. Even today, much of the attention surrounding prodigies considers their capacity to escape a tragic fate as a forgotten child celebrity and continue developing their genius in a useful way for society during their adulthood. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, benefactors and philanthropists were key in supporting child prodigies, helping them cultivate their talents under more positive conditions or simply allowing them to stop performing and become ‘ordinary’ children. However, families were sometimes reluctant to accept offers from philanthropists. Since child prodigies were considered an ephemeral phenomenon, parents and impresarios did not hesitate to prioritise the prodigy’s career over matters such as schooling or socialisation.

In this paper, I employ Samuel Reshevsky’s case to explore the elements that characterise the phenomenon of the child prodigy turned internationally acclaimed celebrity. Obviously, the use of a case study in order to infer general facts concerning this phenomenon has several limitations. Reshevsky’s case is special in a number of ways, such as his talent for chess, which distinguished him from more conspicuous prodigies – for example, in the field of music. Even in the world of chess his story is unusual in terms of the level of public attention he attracted during his childhood, comparable to that suffered by later child stars of film and television. However, as I hope to show, Reshevsky faced many of the challenges experienced by famous children in the early twentieth century – the international commodification of their persona, the neglect of their schooling, and the expectation that they would support their families financially. Such problems were linked to the lack of appropriate policies regarding child labour and protection for itinerant child performers. In this vein, even with its own idiosyncrasies, Reshevsky’s case represents a turning point for the phenomenon of the child prodigy and its relationship to an ever more globalised economy of celebrity in children.

As Jane O’Connor (Citation2008) noted, the child prodigy and the child star are closely linked. In her words, ‘the concept of the child celebrity performer, in terms of a young individual being idolised for their perceived uniqueness and talent, was only brought into being in Western culture with the musical prodigies of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe’ (O’Connor Citation2017, p. 7). Indeed, child prodigies are a modern and socially constructed phenomenon. Although interest in exceptional children existed before the rise of the virtuosos led by Mozart, Liszt and their ‘emulates’ (Menger Citation2009), in previous eras, precocious children were perceived as a symbol of divine or, more frequently, evil possession (Pastoureau Citation1993). In Catholic hagiographical literature, precocity appeared as sign of holiness and was associated with the infant Jesus, who incarnated the motif of the puer senex or the child with the wisdom of an old person (Carp Citation1980). During the Enlightenment, a new understanding of the genius as a ‘new type of being’ (McMahon Citation2013, p. 153) contributed to shaping the modern definition of the child prodigy as an exceptional individual, and the persona of children with extraordinary abilities began attracting wide interest and admiration.

The redefinition of the child prodigy is linked to the ‘invention’ of childhood in Western societies, or the idea that contemporary conceptions of children’s innocence and need for protection are a social construction influenced by demographic, political, scientific, and economic changes (such as compulsory schooling and the rise of the nuclear family) which eventually proclaimed the twentieth century as the ‘century of the child’ (Cunningham Citation2021). The child prodigy phenomenon is yet further proof of the variety of childhoods and the need to consider infancy in its diversity, rather than as a single, natural, and universal phenomenon (James and Prout Citation2005). Prodigies are different from ‘average’ children and their definition as exceptional or extreme cases favoured the development of the construct of the ‘normal child’ in the field of psychology, which was key for modern political and pedagogical reforms (O’Connor Citation2008). Though regarded as children, prodigies did not always enjoy the benefits ascribed to ‘modern’ childhood in the twentieth century, such as the right to receive an education beyond the basics and the exemption from working full-time to support their families (Marten Citation2018). In this vein, the history of child prodigies contributes to debates on the historicity of childhood (e.g. King Citation2007); in particular, this paper explores the commercial, humanitarian, and scientific interests surrounding child prodigies and shows how this phenomenon is linked to the emergence of child celebrities.

Beginning with musical prodigies in the late eighteenth century, the public exhibition of gifted and talented children gave rise to the commercial exploitation of childhood on a global scale. After the French Revolution, the careers of talented children developed more independently within the growing entertainment industry in Europe. Through this cultural democratisation, the fields of expertise associated with child prodigies multiplied, expanding beyond the classical musical domain that characterised court entertainment during the Enlightenment. From the 1850s onward, the press reported on new prodigies in fields such as literature, languages, arithmetic, variety theatre and chess. With the emergence of the mass media, these children began to be exploited as global celebrities. Their fame and the public display of their talent engendered new forms of cultural exploitation of gifted children, including the development of talent shows on radio and television. In this vein, children known for their gifts and talents have been, and are still, marketed as commercial products or commodities. The result is an economy of celebrity (e.g. Rosen Citation1981, Turner Citation2007) that, in the case of children, remains practically ignored for a period prior to the mid-twentieth century, especially outside domains such as the film industry.

Although celebrity status already existed in the eighteenth century (Lilti Citation2014), celebrity studies have hitherto focused largely on famous adults from contemporary society. Even as the study of child celebrities has increased in recent years, its main focus remains the contemporary child performer, especially in Anglo-American contexts (e.g. Addison, Citation2015, O’Connor and Mercer Citation2017, Potter and Hill Citation2017). Overall, celebrity in childhood is far less studied than in adulthood. Moreover, child stars cannot be studied in the same way as adult celebrities. Children’s lack of autonomy makes them dependent on various social actors, starting with their parents, who contribute to their commercial exploitation. It also raises significant questions regarding children’s rights in the realms of child labour, children’s exposure to the media, and the management of their earnings (Marôpo and Jorge Citation2014).

In addition, what has historically contributed to making children famous is their precociousness. This is another factor where celebrity in children differs from adult celebrity. The social perception of precociousness depends, in turn, on its evolving (mainly psychological) definition; for instance, precocity has been defined as both pathology and potential over the past two centuries (Rawlins Citation2006). From this perspective, it is not insignificant that the commercial exploitation of child prodigies increased in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – that is, at the very moment when psychological debates on precocity, genius and talent in children took hold. Hence, examining the international commodification of a child prodigy such as Samuel Reshevsky, along with its relationship to parenting and psychology, contributes fresh approaches to the phenomenon of child celebrity.

Samuel Reshevsky was an important part of the emergence of chess prodigies as child stars in the first half of the twentieth century. His case followed the Cuban worldwide sensation José Raúl Capablanca (1888–1942) and preceded famous boy wonders like the American Bobby Fischer (1943–2008) and the Spaniard Arturo Pomar (1931–2016), as well as contemporary cases like the Polgár sisters, notably Judit Polgár (b. 1976), whose father, psychologist László Polgár, openly admitted to making a parental experiment in the ‘manufacturing of genius’ (Howe Citation1999). In all of these cases, the children’s celebrity transcended the chess aficionados’ sphere, and they became global sensations. However, Reshevsky’s case is unique, in that his early career comprised almost exclusively simultaneous chess exhibitions; for other chess prodigies such exhibitions were more the exception than the rule, and their main focus were the tournaments. The fact that chess as a sport would not become profitable until the second half of the twentieth century influenced the way in which Reshevsky’s talent was presented to the public – in comparison to, for instance, Fischer.

Extant research on former chess prodigies can be divided between the biographical and the psychological approaches. In the first case, the lives of these prodigies have been reconstructed both in relation to their best games of chess and their journey to becoming chess legends (e.g. Brady Citation2011, Sánchez Citation2015). Psychologists, for their part, analysed some of these cases retrospectively to reflect on matters such as talent, innate genius and expert performance (e.g. Howard Citation2008), sometimes utilising a ‘psychobiographical’ approach (Ponterotto and Reynolds Citation2013). Two notable exceptions to this scholarship are the cultural analyses of Arturo Pomar (or simply ‘Arturito’, as he was best known) by Juan Escourido and of Bobby Fischer by John Sharples. On the one hand, Escourido links Pomar’s rise as a child star with the nationalist media propaganda of Francoism, demonstrating the ways the fascist regime ‘exploited the chess prodigy for populist and ideological purposes’ (Escourido Citation2017, p. 63) before abandoning him in his adulthood. On the other hand, Sharples (Citation2017) reveals that Fischer incarnated various types – from the child prodigy to the eccentric chess celebrity and even the ‘monster’ – and asserts that his cultural image reflected political anxieties in America.

In what follows, I begin by examining Reshevsky’s transformation into a child star and a marketable commodity during his European tour in 1920, especially in Paris. I then consider his brief transformation into a psychological subject in Berlin and conclude with his journey in the United States, where, after refusing offers from European philanthropists, his parents finally accepted the patronage of Julius Rosenwald and stopped the commercial exploitation of their child. In my analysis, I draw upon unexamined archival material, including correspondence from Reshevsky’s parents, tutors, managers and benefactors, which facilitate an investigation of the network of interests surrounding the child prodigy. These rare and exceptional materials – in combination with the press, a short silent film about Reshevsky’s feats, his psychological investigation by Franziska Baumgarten, and his autobiographical texts – permit reconstructing, for the first time, the transformation of this chess wonder from local sensation to worldwide celebrity.

Marketing the prodigy: Samuel Reshevsky in Paris

Born in what would later become Poland in 1911, Reshevsky, the sixth and youngest child from a humble family of Orthodox Jews, was raised according to their religious traditions. He learnt to play chess at the age of four with his father, who was an amateur player. In less than a year, the boy began to defeat all the players in his region, and at six years old, he was brought to Warsaw to compete against national chess masters. There, he lost against the grandmaster Akiba Rubinstein (1882–1961), from whom he learned some techniques and who assured him he would become a world chess champion one day (Reshevsky Citation1954). The same year, he played against Hans Hartwig von Beseler (1850–1921), the German military governor of the territory during the First World War occupation. After winning, Reshevsky allegedly told Beseler: ‘You know how to kill, but I know how to play’ (Le Petit Journal Citation1920). During his chess exhibitions in Poland after its independence in 1918, a young physician, Dr Rosin, noticed him. Amazed by the child’s genius, Dr Rosin convinced Reshevsky’s parents to display his talent in Europe. When Reshevsky was eight years old, his family and Dr Rosin embarked on a tour that took them from Vienna to Berlin, Hamburg, Amsterdam, The Hague, Antwerp and Brussels, among other cities. The physician looked after the boy’s health, preventing him from playing too frequently and ensuring he had adequate rest and was well nourished (Soly Citation1920).

The Reshevskys’ arrival in Paris in May 1920 was much anticipated by the French press, which had been reporting on the boy’s chess exhibitions across the Old Continent. The family had planned to stay in the city until their departure for London in August and the United States at the end of the year. As in the other cities they had visited, in Paris Samuel was expected to participate in chess displays where he competed simultaneously against twenty players. His first exhibition took place in the Café de la Rotonde inside the gardens of the Palais Royal, close to the Louvre. Historically, chess players had been meeting in various cafés around the Palais Royal, where they had also received international masters. Since 1740, the Café de la Régence was their main headquarters, becoming one of the greatest chess meeting points in Europe. In 1858, La Régence welcomed the American prodigy Paul Morphy (1837–1884), who held a blindfolded chess exhibition against eight players (Edge Citation1859). In 1918, a conflict with the owners of La Régence forced chess players to relocate to nearby cafés – first to L’Univers and finally to the Café de la Rotonde in 1920, the year of Reshevsky’s exhibition (Schneider Citation1918).

On May 15, the boy won twenty games in his first simultaneous display against some of the best players of the city – including Marc Herzfeld, who had recently obtained a draw against Capablanca, the forthcoming 1921 world champion (J.L. Citation1920). The exhibition lasted approximately three hours, after which, according to the press, Reshevsky hurried himself into the gardens of the Palais Royal to play with other children as if nothing extraordinary had happened (Le Petit Parisien Citation1920). The international media (including, for example, the Indian press) reported on Reshevsky’s feats, and he landed on the cover of the best-selling French magazine Le Miroir ().

Figure 2. Samuel Reshevsky, eight years old, during his first simultaneous exhibition at the Café de la Rotonde in Paris, 15 May 1920. Published in Le Miroir, 23 May 1920. Courtesy of Gallica/Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

A second simultaneous display was organised a week later with stronger players, but the results were similar, and Reshevsky left triumphant. On this occasion, a short silent film of 28 seconds captured the event and was released by Pathé in the cinema news section in France and abroad. Illustrating the level of international attention Reshevsky attracted, it was even screened in American movie theatres before his arrival to the United States at the end of that year (The Detroit Jewish Chronicle Citation1920). As the film opens, a text caption displays the following message: ‘Paris – France – A young prodigy. Samuel Rzeszewski, eight years old, plays several chess games simultaneously and beats the best players of the Palais Royal Chess Circle’. The film shows Reshevsky dressed in a sailor’s suit moving inside a square form of chess tables and playing rapid moves against his adult adversaries. Men packed inside the café and against the windows stare at the boy and comment on the scene with astonishment (Un jeune prodige Citation1920). These and other images of the young Reshevsky confronting his adult adversaries (usually men over fifty years old) is a reminder that child prodigies and other child stars have been historically admired for their adult-like abilities (Marshall Citation2017).

Following his success in Paris, Reshevsky became a marketable commodity, and his simultaneous exhibitions began to attract a large audience, including aristocratic women, artists and business people who were not chess aficionados but took an interest in the child – as we shall see in the last section. However, greater success also entailed greater problems. Once the initial amazement passed, social concerns began to surface. For example, the Parisian press noted that, despite being eight years old, Reshevsky had never attended school nor had he received any kind of formal education (beyond the study of the Talmud); in fact, he barely knew how to read and write. In public opinion, his talent for chess began to be portrayed as aimless, and doubts were raised about his chances of becoming a ‘true’ genius like Blaise Pascal, who had also been a child prodigy (J.L. Citation1920). In the words of the theatre and music critic Louis Schneider: ‘Let’s hope that he applies his wonderful chess skills to deeper and more useful goals and wait for the moment when we will be told about a great savant who is, at the same time, a chess celebrity’ (Schneider Citation1920).

Reshevsky’s lack of schooling was quite shocking for the French society of the 1920s, where compulsory elementary education had been implemented in the 1880s; however, his case was no exception among child prodigies. Although primary education was mandatory in many European countries since the late nineteenth century, illiteracy and a lack of elementary studies were frequent characteristics of child prodigies of all domains and backgrounds, including children from more well-to-do classes (Graus Citation2020). Considering these children’s celebrity a perishable phenomenon, parents and impresarios prioritised the commercial exploitation of the child’s talent before other matters. To develop their talents, children received a focused education in their domain of expertise, while their elementary studies were postponed until the age of twelve or later – that is, until their career as a prodigy began to fade or a lack of general education became too noticeable. In the long term, however, a one-dimensional education adversely affected the prodigy’s development, including in the cultivation of their talent. Dr Rosin told the press that he wanted Reshevsky to abandon chess and develop his faculties at school to become a ‘man of genius’, but his parents hesitated given the profit to be made out of his simultaneous displays (Bret Citation1920). Beyond Dr Rosin, other scientists in Europe expressed concerns about Reshevsky’s lifestyle and the harm it could cause to his development, and these concerns made him, like other famous child prodigies, a subject of scientific enquiry.

Testing the prodigy: science as an advertisement campaign

Although it was modern psychology that established child prodigies as a scientific subject, scientific interest on these children had been growing since the eighteenth century following the redefinition of genius as a quality of humankind (McMahon Citation2013). In 1764, a member of the Royal Society submitted the eight year-old Mozart to a series of tests to understand genius in its infancy (Barrington Citation1770). Other savants in Europe examined the abilities of mathematical and academic prodigies from multiple points of view, including phrenology and anthropometrics (Nicolas et al. Citation2013). Since the late nineteenth century, experimental psychology asserted that child prodigies facilitated the investigation of general mental traits, such as memory and intelligence, because in them those traits were magnified (Carson Citation1999). This interest was consistent with the psychological attention devoted to other subjects considered extreme or abnormal, such as feral children. Concerning chess, some psychologists, notably Alfred Binet (1857–1911), examined adult chess players to investigate visual memory and imagination (Binet Citation1894), but overall research on the subject remained quite scarce until the 1940s, when the Dutch psychologist and chess player Adriaan de Groot (1914–2006) began his experiments on chess from the cognitive point of view, which became very influential (de Groot Citation1978).

In what appears to be the first investigation of an infant chess prodigy, psychology sought to explain Reshevsky’s talent for chess as well as his general mental faculties. In 1920, the Swiss Franziska Baumgarten (1883–1970), a specialist in psychometrics and gifted children, attended one of Reshevsky’s chess exhibitions in Berlin and convinced the child’s father to submit the boy to a short examination. According to Baumgarten, parents whose children were at the beginning of their careers were more inclined to consent to scientific enquiry because they saw it as a means of advertising their case and certifying their child’s ‘genius’ (Baumgarten Citation1930, p. 5). In contrast, if a child prodigy had already built a reputation, parents were more reluctant to allow scientists to examine their offspring and, perhaps, discredit the prodigy.

Indeed, a majority of scientific enquiries on child prodigies occurred at the beginning of their careers. Mozart’s examination, mentioned above, took place during his first major European tour, when he had just attained international celebrity and doubts were still being raised about the genuineness of his talent. Around the 1840s, the Academy of Science in Paris examined calculating prodigies such as the Sicilian Vito Mangiamele (1827–1897) at the age of ten. At the turn of the twentieth century, even more precocious cases attracted scientific curiosity. In Berlin, psychologist Carl Stumpf (1848–1936) studied a German prodigy named Otto Pöhler (1893-?) when the boy was only two years old. Pöhler was a polyglot and was being exhibited in one of the city’s Panoptikums, which displayed ‘exotic’ and ‘deformed’ people (Stumpf Citation1897). A few years later, the physiologist Charles Richet (1850–1935) presented a three-and-a-half-year-old musical prodigy, Pepito Arriola (1896–1954), known as ‘the Spanish Mozart’, during the 4th International Psychology Congress in Paris (Richet Citation1901). In all such cases, the expert assessments of the children served as advertising campaigns that spread their fame in the international media. Concerning Reshevsky, Baumgarten’s investigation (examined below), which was the first to be conducted on him, appeared in the newspaper Berliner Tageblatt, in psychology journals across Europe and in chess magazines, nourishing the general fascination with this wunderkind (Baumgarten Citation1920, Citation1939).

In general, the celebrity status of a child prodigy contributed significantly to the possibility of the child becoming an object of scientific enquiry, and a majority of experts admitted discovering these children thanks to their public reputation. However, the prodigies’ careers as child stars restricted the time and circumstances for scientific examinations. As Baumgarten (Citation1930) noted, child prodigies were ‘migratory birds’ who only spent a few days in a city, where, between their performances and attending the press, they had little time for anything else. In this vein, the scientific enquiry of child prodigies often assumed an improvised form and was conducted in non-laboratory settings; for instance, Baumgarten examined Reshevsky during a few hours in his hotel room. These constraints could make the research appear more preliminary than conclusive, and some scientists admitted the limitations of their investigations under the given circumstances (e.g. Richet Citation1901). Nevertheless, the novelty of such research in the early twentieth century made it relevant even in the absence of appropriate scientific conditions.

In January 1920, in Reshevsky’s hotel room in Berlin, Baumgarten took a chance and submitted the boy to various mental tests, including tests of spatial perception, numerical memory and the Binet-Simon intelligence test. However, a number of problems impeded the progress of the experiment. First, Reshevsky only understood Yiddish correctly, but the tests were in German, so his father had to translate the questions for him. Reshevsky’s ignorance of the Latin alphabet also prevented him from performing some tasks to test his memory, such as memorising series of letters from the alphabet. In addition, his Orthodox Jewish upbringing strongly influenced the development of the experiment. For example, following an exercise from the Binet-Simon intelligence test, Baumgarten (Citation1930) attempted to assess Reshevsky’s aesthetic judgment by showing him pictures of women’s faces, some prettier than others, but the boy refused to look at them, arguing that, as a Jew, he was not allowed to stare at women.

In general, Reshevsky’s results exceeded the average on tasks related to chess, such as spatial perception and numerical memory; for example, he was able to memorise forty numbers within four minutes, an astonishing result. However, he failed in tasks that had a strong cultural and class influence. Unlike many children of his age or even younger, he could not recognise animals such as a lion or a monkey because he had never been to a zoo or seen a picture book. He also failed in drawing tests because he had never drawn before. In the end, Baumgarten compared Reshevsky’s poor performance in the Binet-Simon intelligence test with the results obtained from working class children who had little to no schooling. She determined that Reshevsky, like many uneducated child prodigies, had the capacities but lacked the knowledge and concluded the following:

I pointed out the dangers of the boy’s lifestyle to the parents and even suggested that they looked after his future, but I could not compete with the dollars that awaited him on his tour. There were no limits to the boy’s exploitation since the social institutions did not supervise and regulate the mental and physical exploitation of such children. (Baumgarten Citation1930, p. 58)

Apart from disseminating her findings in the general press, Baumgarten published her investigation on Reshevsky and other child prodigies, from illustrators to virtuosos, in a book entitled Wunderkinder: psychologische Untersuchungen [Child Prodigies: Psychological Investigations] (Citation1930). Adriaan de Groot (Citation1978, p. 11) judged the book to be ‘entertaining but superficial’; however, Baumgarten continues to be considered a pioneer in contemporary psychological research on child prodigies (Shavinina Citation2010). As we shall see in the next section, wealthy personalities in Europe approached Reshevsky’s family to end the boy’s exploitation. However, it was only in the United States, the country where the Reshevskys settled, that child protection services intervened.

‘Playing for his future’: benefactors and philanthropists

Sometimes, because the child’s performances were the main financial resource of the family, exploiting a prodigy’s talent was a matter of survival. This practice was more common among children of the lower classes who, as the main source of income for their households, were more systematically obliged to perform continuously. In Reshevsky’s case, the revenues of his simultaneous displays supported his parents and five older siblings. To remedy the commercial exploitation of the child, however, benefactors and philanthropists offered financial help to families. Some expected to become the prodigy’s guardian and were willing to compensate parents financially in exchange for child custody. Already in the early nineteenth century, the fathers of the calculating prodigies Zerah Colburn (1804–1839) and George Bidder (1806–1878) received generous offers to pay for their child’s education until college. While Colburn’s father removed his son from prestigious schools in Paris and London to continue exploiting his talent (Colburn Citation1833), Bidder was able to stop performing and graduate from the University of Edinburgh thanks to sponsorship from the Fellows of the Royal Society (Shuttleworth Citation2010).

The Reshevskys received similar offers concerning their child. During their stay in Paris, Marie Bonaparte (1882–1962), Princess of Greece and Denmark, and the Rothschilds, a wealthy Jewish family with different branches across Europe, offered financial support to provide Samuel with an education and end his public exhibition.Footnote1 Rabbi Joël Leib Herzog (1862–1934), a contact of the Reshevskys in Paris, was responsible for approaching both Bonaparte and the Rothschilds. Apart from being an Orthodox Jew like the Reshevskys, he was also of Polish origin. He brought Samuel and his parents to Marie Bonaparte’s mansion on the outskirts of Paris, where the boy met the princess’s children and learnt to ride a bicycle, which became one of his passions (Shea Citation1920). What seemed to strike Marie Bonaparte the most was Reshevsky’s Orthodox Jewish upbringing, which prevented him from eating anything that was not kosher and from staring at or touching women, including Bonaparte’s ten year-old daughter whom (the princess wrote in her diary) had not started to menstruate and therefore was just a child and not yet a woman (Bonaparte Citationn.d., pp. 644–645).

Although the Reshevskys refused Bonaparte’s offer to stay in Paris and stop Samuel’s performances, they did permit her to organise a charity chess contest in the Hotel Majestic on the 1st of July 1920, the profits of which they later reclaimed (Rzeszewski Citation1920).Footnote2 Newspapers in Paris advertised the competition saying that this exhibition was different because Reshevsky was ‘playing for his future’ (Richard Citation1920), and the benefits obtained were supposedly aimed at supporting the boy’s schooling and preventing his commodification (Bonaparte Citationn.d., pp. 645–646). During the tournament, the Countess of Beauchamps sold postcards of Reshevsky to the attendants and collected 500 francs, which were used to pay for the tour expenses (Le Temps Citation1920). This example reveals that derivative celebrity commodities of Reshevsky were already being produced during his first tour.

Bonaparte’s benefit was Reshevsky’s last chess exhibition in Paris before the family departed for London and, later, the United States. In their correspondence with Marie Bonaparte, Rabbi Herzog and Dr Rosin appealed to her compassion, mentioning that Samuel wished to stay in Paris but that his parents would not allow it (Herzog Citation1920a, Citation1920c, Rosin Citation1920a). In one of his letters, Dr Rosin, who had refused an offer from the Reshevskys to follow them to America, did not hesitate to paint an awful portrait of the child’s situation. Although it is a long quotation, it deserves to be presented in full:

Little Samuel, before leaving for London, came up to my house with his father and mother to say goodbye. He offered me his little ice-cold hand and held it in mine for a long time without being able to say anything to me. In his usually cunning eyes, which today were sad, I saw a feeling of regret. He looked so unhappy that when he left, I started to cry. I felt guilty towards this child. It seemed to me that I did not do all my duty towards him. And then the dream I had been nourishing for several months disappeared forever. I took the child out of Poland to make him a useful being for humanity and what an ending!

Here he is launched into the world of ‘money’. They are going to exploit him so cynically—because I have no doubt that they will do everything to make him play in England and America. They will find people and means to succeed. They know how to invent all kinds of stories to make people feel good or to make other ‘trues’ [sic], and there will be no one to expose them. (Rosin Citation1920b)

This letter reveals the intricate network of interests surrounding the child prodigy, including Dr Rosin’s own expectations, which, although he had been careful to hide before Bonaparte, had been not only humanitarian but also financial (Herzog Citation1920b); after all, it was Rosin who had convinced Reshevsky’s parents to launch a European tour and exhibit the child’s talent for chess, although he later regretted it. Still filled with contempt, just before the Reshevskys departure for the United States in October 1920, Dr Rosin (Citation1920c) asked Princess Bonaparte to disseminate negative propaganda of the parents in the American press and contact the New York child welfare services. Although Bonaparte agreed that Reshevsky’s parents were ‘raptors’ and ‘horrible child exploiters’ (Bonaparte Citationn.d., p. 464), she did not make any move in this regard. However, as we shall see, it would not take long for the children’s court to intervene.

The Reshevskys crossed the Atlantic like many other European immigrants in search of the American dream, arriving in New York on the 3rd of November 1920. There his new manager, Max Rosenthal, had already arranged several simultaneous displays, and his arrival was announced in the newspapers. Despite lacking the ability to speak English except for a few chess terms, such as check and checkmate, Reshevsky, in his first exhibition, defeated nineteen army officers before 500 spectators, confirming the reputation he had built on the Old Continent (Moritzen Citation1920). Shortly thereafter, the family began an extensive cross-country tour that lasted almost two years. Reshevsky played in all the major cities, attracting crowds of hundreds to his displays and defeating some of the best chess masters, such as David Janowski (1868–1927), as well as U.S. congressmen. In June 1921, during his stay in Los Angeles, he visited the Hollywood studio where Charlie Chaplin was working on the cutting of The Kid and invited him and Jackie Coogan to his simultaneous exhibition at the Athletic Club. In his autobiography, Chaplin recalls the event as follows:

It was not necessary to understand chess to appreciate the drama of that evening: twenty middle-aged men poring over their chessboards, thrown into a dilemma by an infant of sevenFootnote3 who looked even less than his years. To watch him walking about in the centre of the ‘U’ table, going from one to another, was a drama in itself. (Chaplin Citation2012, pp. 234–235)

After the simultaneous display, Coogan and Reshevsky posed together for a picture while wearing boxing gloves (The Bridgeport Times Citation1921). While the film industry had found a new marketable commodity in children like Coogan (King Citation2001), Reshevsky’s career as a chess prodigy was abruptly interrupted not long after the boys met. On the night of the 22nd of October 1922, Reshevsky was brought to the Bronx Children’s Court where his parents were charged with improper guardianship. Earlier that night, the boy had participated in a benefit for the National Hebrew Orphanage, singing songs and playing five opponents simultaneously. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SPCC)Footnote4 issued a warrant arguing that the Reshevskys had not obtained permission to exhibit Samuel on a Sunday and accused them of causing mental strain to the child and neglecting his education (The Evening Star Citation1922). They insisted that a condemnation was necessary ‘to prevent the further exploitation of the boy for the financial gain of his father, mother and a manager [then, Leo Fisher]’ (New York Tribune Citation1922a). In the end, the judge dismissed the case, maintaining that the charity event was not a theatrical performance and that it did not impair the child’s morals or health; in addition, the parents argued that the boy was a student in a Jewish seminary (New York Herald Citation1922, New York Tribune Citation1922b).

After the incident, however, the press began to call the Reshevskys ‘exploiters’. Although the parents claimed that Samuel only earned 150 dollars per exhibition and that they did not rely on his income, newspapers reported that he earned between three and four thousand dollars per simultaneous display. They compared Samuel with Jackie Coogan, whose parents had allegedly put his money (millions) into a trust fund to avoid such accusation (The Paragould Soliphone Citation1922). As it is well known, when Coogan gained access to the fund at twenty-one years old, he was shocked to discover that the sum amounted to only a thousand dollars. He recovered part of the stolen money by taking his parents to court, and in 1939, the State of California passed the ‘Coogan Bill’ (California Child Actor’s Bill) establishing that the earnings of child performers belong exclusively to them (O’Connor Citation2017). It is worth noting that legislation concerning child stars has often been built around particular cases, such as the ‘Shirley Temple Act’, which allows the hiring of child actors under the legal employment age (Podlas Citation2010).

The confrontation with the SPCC served as a warning for the Reshevskys, who were advised to find a sponsor and report regularly to the children’s court (Tassinari Citation1993). An opportunity came in August 1924, when the boy participated in a chess tournament organised by Morris Steinberg, a Jewish businessman and chess enthusiast from Detroit, who became Reshevsky’s ‘big brother’ (The Detroit Jewish Chronicle Citation1929). He and other Jewish executives were able to secure funding from the millionaire and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald (1862–1932), co-owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company.

Rosenwald had first met Reshevsky in Chicago during the spring of 1921, when he hosted a game at his home against the U.S. chess champion of German origin Edward Lasker (1885–1981), which Reshevsky lost. When Lasker picked Reshevsky up at the train station he was expecting to meet a boy a little older than his alleged nine years old (after all, it was common for child prodigies to lie about their age so as to appear even more wondrous) but he found that Reshevsky looked even younger. About a hundred guests were invited to the game at Rosenwald’s home. According to Lasker:

They were completely spellbound by the unlikely spectacle which unfolded before their eyes, and though quite a number among them did not know the game at all and had come only to get a close look at the boy, they sat silently, as if hypnotized, through the two hours during which the play lasted. I felt hypnotized myself. (Lasker Citation1951, pp. 231–232)

A picture captured the event: Rosenwald, in the middle, acting as referee, while an international group of attendees, including the cousin of the emperor of Japan, watched the boy play and Samuel’s parents stood behind him (). The image portrays the kind of naive entertainment surrounding child prodigies, where their public exhibition appears justified and harmless given their extraordinary nature.

Figure 3. Samuel Reshevsky, nine years old, playing against Edward Lasker at Julius Rosenwald’s home. In The Chicago Tribune, ‘Youthful chess champion defeated’, 1 April 1921. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

In exchange for Rosenwald’s support, the family agreed to settle in Detroit and end the boy’s performances until he graduated from college (Slomovitz Citation1936). According to Reshevsky, during his nine years of absence from public view, ‘occasionally, someone would ask what had happened to the boy wonder with the tongue-twisting name – “the one who beat everybody at chess a few years ago” – but only a few intimate friends knew the answer. Young Sammy Rzeszewski was learning to read and write!’ (Reshevsky Citation1948, p. 21). Reshevsky resumed his chess career after graduating with a degree in accounting from the University of Chicago in 1933 and became an international grandmaster. In this way, Reshevsky was ultimately able to break with the old proverb concerning child prodigies, which in Liszt’s words, asserts that they ‘have their future in the past’ (cited in Baumgarten Citation1939, p. 246).

Conclusion

The recent success of The Queen’s Gambit (Citation2020) series has renewed the worldwide appeal that chess enjoyed during the first half of the twentieth century and enabled the chess boy wonders of that time (Capablanca, Pomar, Fischer to become pop culture icons (Escourido Citation2017, Sharples Citation2017). In 1920, Samuel Reshevsky, the youngest chess prodigy of the period, was transformed into a global child star and a cultural incarnation of the child prodigy. His appearance on the cover of best-selling magazines like Le Miroir, the short film on his simultaneous exhibition screened in France and America, and the hundreds of articles in the international press demonstrate his celebrity status before the advent of Hollywood’s child star era that followed the release of The Kid in 1921.

Reshevsky’s rise into stardom was influenced by the globalisation of the media and the growth of the entertainment industry in cities, which allowed for the expansion of the child prodigy phenomenon in multiple fields. Moreover, improvements in the quality and costs of transportation facilitated the international mobility of young talents. While early nineteenth century prodigies such as the calculating prodigy Zerah Colburn had already crossed the Atlantic from the U.S. to Europe, Reshevsky and his parents were able to tour seven European countries and reach the United States in less than a year. This extensive travel enabled Reshevsky’s public persona to be more easily exposed and consumed in different countries and before more numerous audiences, and it increased the media attention he received.

The celebrity status of the prodigy influenced not only the entertainment business but also the scientific and humanitarian milieu surrounding child prodigies. Psychology experts were not immune to the trends of celebrity culture and capitalised on the prodigies’ mobility to examine their talent. Recognising their potential value as a promotional campaign, the parents of child prodigies often agreed to such examinations, especially at the beginning of their child’s career. Nevertheless, they did not seem interested in following the experts’ subsequent advice. Baumgarten’s recommendation to halt Reshevsky’s public exhibition and provide him with an appropriate education was certainly disregarded by his parents until the Bronx Children’s Court advised them to find a benefactor.

The interest that philanthropists took in child prodigies aligned with early twentieth-century values against child labour and abuse, which prompted new legislation to defend children’s rights. Although Reshevsky’s parents finally agreed to settle down in exchange for Rosenwald’s support, it must be noted that, by that time, Samuel was already twelve years old and that his career as a child prodigy had certainly reached its peak. In other words, the profit to be made out of his commercial exploitation was no longer comparable to its level in 1920, when they had refused financial offers from Bonaparte and the Rothschilds. That does not mean, however, that the final outcome was unsatisfactory. Reshevsky’s career as a chess prodigy certainly offered him many more opportunities (including the chance to obtain a university degree) than he could have dreamed of had he lived as a ‘normal’ Orthodox Jewish child in Poland in the early twentieth century. His talent brought him and his family an escape from the dramatic situation of their country during the First World War and the post-war years, as well as a safe home in the United States, especially during the Second World War. Unlike other former child prodigies, Reshevsky was not resentful of his parents for his childhood experiences and was able to live an ordinary life in his adulthood, forming a family and continuing his religious traditions.

As for other child celebrities, the prodigy’s voice is frequently absent from the picture and can be traced only occasionally via historical sources. Some former prodigies recounted their stories in autobiographies written in their adulthood, which provided them with the opportunity to reflect on their childhood and blame or defend their parents. Reshevsky did not write an autobiography per se, but some of his books on chess combine a personal account of his life with an expert explanation of his best-known games. In those texts, Reshevsky sought to normalise his experience as a world-famous prodigy. Although he admitted that it was an ‘unnatural life for a child’, he professed to have enjoyed his travels with his family and to have known that there was something ‘special’ about how he played chess (Reshevsky Citation1948, p. 1–2). To protect his parents from further criticism, he also concealed controversial facts about his childhood. For instance, when writing about the end of his career as a prodigy and the beginning of his formal schooling in 1924, he did not mention his parents’ problems with the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children; instead, he simply stated that ‘it was decided that a formal education was long overdue’ (Reshevsky Citation1948, p. 21). In this vein, his autobiographical texts represent merely a projection of himself and, as such, should be read as yet another layer of the celebrity’s public persona.

The digital era poses new yet similar challenges to the phenomenon of child celebrity to those experienced by Reshevsky. In recent years, the viewing time of YouTube channels aimed at infants (many of them presented by children) has seen an increase of around 200%. A popular format is the ‘unboxing toys’ channel, responsible for child stars and influencers like Ryan from Ryan Toys Review (Burroughs Citation2017). Along with these new e-celebrities, child prodigies in music and other domains continue to proliferate on YouTube with specific resonances to Mozart-like figures (de Mink and McPherson Citation2016). Like past prodigies, these ‘microcelebrities’ are managed and monetised by their parents, including new practices like ‘sharenting’ – sharing pictures and other content of one’s children online – which violate the infants’ digital right to be forgotten (Leaver Citation2021).

The legal void concerning child protection policies affecting child stars of the digital era is comparable to that suffered by Reshevsky and other prodigies before him. Existing child labour guidelines do not apply to children who work from domestic spaces, such as YouTube child influencers (Burroughs and Feller Citation2021), or children who appear in reality television shows (Podlas Citation2010). Furthermore, the terms of the contracts between these microcelebrities and their agents are obscure (Abidin Citation2021). As in previous centuries, the lack of legislation results in uncontrolled forms of child abuse both by parents and by the media industry, to the point that there is arguably a need for a new ‘Coogan Bill’ for the digital era. As noted above, new policies concerning child stars are often inspired by particular cases. Reshevsky’s case influenced the ways in which child welfare services dealt with the public exhibition of prodigies, and this may explain why later chess wonders participated in fewer simultaneous displays. In this way, his experience contributed to raising social awareness of this issue and served to vindicate the rights of children whose talents make them famous.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Rémy Amouroux for providing excerpts of Marie Bonparte’s journal concerning Samuel Reshevsky, and to Florent Serina for facilitating this exchange. I also want to thank John Donaldson, Oliver Hochadel, Stefan Löffler, and Hanon Russell for reading previous versions of this article and sharing their knowledge and memories about Reshevsky.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrea Graus

Andrea Graus is a Beatriu de Pinós Fellow at the Milà i Fontanals Institution (CSIC), where she examines the history of child prodigies and the fascination with talent in children. Part of the research for this article was done while she was a Marie Curie Fellow at the Centre Alexandre Koyré (CNRS).

Notes

1. Before them, a philanthropist from Hamburg had offered 250,000 marks to pay for Reshevsky’s schooling and halt his performances, but the father refused (Soly Citation1920). This was one of the many offers that he declined.

2. While in London, Reshevsky’s father wrote (in English) to Marie Bonaparte: ‘I really don’t known how can I and my family express all our gratitude to you, for your angelic goodness, yet I am in a pecuniary situation as I had to pay too many debts in Paris, and left without [a] penny. I should be ever so thankful to you, Madam, if you would be so kind as to send me the balance of that last chess exhibition as I need it for our food’ (Rzeszewski Citation1920).

3. Reshevsky was nine years old at this time.

4. The SPCC was founded in 1874 in New York City, becoming the first child protection agency to prevent child neglect and abuse and expanding throughout the United States and Britain (Thompson Citation2001).

References

- Abidin, C., 2021. Pre-school stars on YouTube: child microcelebrities, commercially viable biographies, and interactions with technology. In: L. Green, et al., eds. The Routledge companion to digital media and children. New York and London: Routledge, 226–234.

- Addison, H., 2015. ‘Holding our heartstrings in their rosy hands’: child stars in early Hollywood. The journal of popular culture, 48 (6), 1250–1269. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12358

- Barrington, D., 1770. An account of a very remarkable young musician, a letter from the Honourable Daines Barrington, F.R.S., to Mathew Maty, M.D., Sec. R.S. The philosophical transactions of the royal society, 60, 54–64.

- Baumgarten, F., 1920. Wunder oder Kind? Zur Intelligenz-Prüfung des Schachwunderkindes. Berliner Tageblatt, 4 Feb.

- Baumgarten, F., 1930. Wunderkinder, psychologische Untersuchungen. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Baumgarten, F., 1939. When Samuel Reshevsky was a ‘prodigy’. Intelligence tests on the U.S. champion twenty years ago. Chess, 14 Mar., 245–246.

- Binet, A., 1894. Psychologie des grands calculateurs et joueurs d’échecs. Paris: Hachette.

- Bonaparte, M., n.d. Private journals. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Princess Marie Bonaparte’s papers, Sigmund Freud Collection, Manuscript Division, MSS13169.

- Brady, F., 2011. Endgame. Bobby Fischer’s remarkable rise and fall - from America’s brightest prodigy to the edge of madness. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Bret, P., 1920. À huit ans il fait ‘échec et mat’ de vieux maîtres du jeu. L’Intransigeant, 27 May.

- The Bridgeport Times, 1921. Camera news. The Bridgeport Times, 2 Sept.

- Burroughs, B., 2017. YouTube kids: the app economy and mobile parenting. Social media + society, 3 (2), 1–8. doi:10.1177/2056305117707189

- Burroughs, B. and Feller, G., 2021. The emergence and ethics of child-created content as media industries. In: L. Green, et al., eds. The Routledge companion to digital media and children. New York and London: Routledge, 217–225.

- Carp, T.C., 1980. ‘Puer senex’ in Roman and Medieval thought. Latomus, 39 (3), 736–739.

- Carson, J., 1999. Minding matter/mattering mind: knowledge and the subject in nineteenth-century psychology. Studies in history and philosophy of biological and biomedical sciences, 30 (3), 345–376. doi:10.1016/S1369-8486(99)00016-3

- Chaplin, C., 2012. My autobiography. New York: Melville House.

- Colburn, Z., 1833. A memoir of Zerah Colburn; written by himself. Springfield: G. and C. Merriam.

- Cunningham, H., 2021. Children and childhood in western society since 1500. 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- de Groot, A.D., 1978. Thought and choice in chess. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Academic Archive.

- de Mink, F. and McPherson, G.E., 2016. Musical prodigies within the virtual stage of YouTube. In: G.E. McPherson, ed. Musical prodigies. Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 424–452.

- The Detroit Jewish Chronicle, 1920. Youthful chess prodigy arrives to conquer U.S. The Detroit Jewish Chronicle, 12 Nov.

- The Detroit Jewish Chronicle, 1929. Sammie Reshevsky hailed by his friends as great chess player and fine singer. The Detroit Jewish Chronicle, 1 Mar.

- Edge, F., 1859. Paul Morphy, the chess champion. An account of his career in America and Europe. London: William Lay.

- Escourido, J., 2017. Arturo Pomar will always be Arturito: media, nationalism and sports celebrity in Francoist Spain. Studia Iberica et Americana, 4 (4), 57–78.

- The Evening Star, 1922. Boy chess shark in court fight over guardian. The Evening Star, 23 Oct.

- Graus, A., 2020. Extreme giftedness? Trading on the general education of child prodigies in the nineteenth century. Dynamis, 40 (2), 349–373.

- Herzog, J.L., 22 July 1920a. Herzog to Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (46).

- Herzog, J.L., 2 Aug 1920b. Herzog to Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (46).

- Herzog, J.L., 5 Aug 1920c. Herzog to Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (46).

- Howard, R.W., 2008. Linking extreme precocity and adult eminence: a study of eight prodigies at international chess. High ability studies, 19 (2), 117–130. doi:10.1080/13598130802503991

- Howe, M.J.A., 1999. Genius explained. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- J.L., 1920. Un joueur d’échecs merveilleux. Le Temps, 16 May.

- James, A. and Prout, A., 2005. Constructing and reconstructing childhood. 2nd ed. London: Falmer Press.

- King, M.L., 2007. Concepts of childhood: what we know and where we might go. Renaissance quarterly, 60 (2), 371–470.

- King, R., 2001. The kid from The Kid: Jackie Coogan and the consolidation of child consumerism. The velvet light trap, 48 (Fall), 4–19.

- Lasker, E., 1951. Chess secrets I learned from the masters. New York: Dover.

- Le Petit Journal, 1920. Samuel Rzeszewski le petit ‘as’ du jeu d’échecs aime surtout les montagnes russes. Le Petit Journal, 26 May.

- Le Petit Parisien, 1920. Un enfant de huit ans bat les meilleurs joueurs d’échecs. Le Petit Parisien, 17 May.

- Le Temps, 1920. Le petit joueur d’échecs. Le Temps, 3 July.

- Leaver, T., 2021. Balancing privacy: sharenting, intimate surveillance, and the right to be forgotten. In: L. Green, et al., eds. The Routledge companion to digital media and children. New York: Routledge, 235–244.

- Lilti, A., 2014. Figures publiques. L’invention de la célébrité. Paris: Fayard.

- Marôpo, L. and Jorge, A., 2014. At the heart of celebrity: celebrities’ children and their rights in the media. Communication & society, 27 (4), 17–32. doi:10.15581/003.27.4.17-32

- Marshall, D., 2017. Music/image and the cusp-persona: the child/adult public persona of child celebrities. In: J. O’Connor and J. Mercer, eds. Childhood and celebrity. Abingdon: Routledge, 184–193.

- Marten, J., 2018. The history of childhood: a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McMahon, D.M., 2013. Divine fury. A history of genius. New York: Basic Books.

- Menger, P.-M., 2009. La précocité créatrice et les conditions sociales de l’exception. In: Le travail créateur. S’accomplir dans l’incertain. Paris: Gallimard, Seuil, 429–445.

- Moritzen, J., 1920. Poland’s chess prodigy to battle best players in the United States. The Sunday Star, 14 Nov.

- New York Herald, 1922. Boy chess expert, 10, wins right to play on. New York Herald, 16 Nov.

- New York Tribune, 1922a. Boy chess marvel is arrested; parents accused as exploiters. New York Tribune, 22 Oct.

- New York Tribune, 1922b. Boy chess wizard stumped by mysterious moves of law. New York Tribune, 24 Oct.

- Nicolas, S., Guida, A., and Levine, Z., 2013. Broca and Charcot’s research on Jacques Inaudi: the psychological and anthropological study of a mental calculator. Journal of the history of the neurosciences, 23 (2), 140–159. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2013.840751

- O’Connor, J., 2008. The cultural significance of the child star. New York: Routledge.

- O’Connor, J., 2017. Childhood and celebrity: mapping the terrain. In: J. O’Connor and J. Mercer, eds. Childhood and celebrity. Abingdon: Routledge, 5–15.

- O’Connor, J. and Mercer, J., eds., 2017. Childhood and celebrity. Abingdon: Routledge.

- The Paragould Soliphone, 1922. ‘Kid stars’ have money troubles. The Paragould Soliphone, 1 Nov.

- Pastoureau, M., 1993. Enfants prodiges, enfants du diable. In: M. Sacquin, ed. Le printemps des génies. Les enfants prodiges. Paris: Robert Laffont/Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 27–33.

- Podlas, K., 2010. Does exploiting a child amount to employing a child? The FLSA’s child labor provisions and children on reality television. UCLA entertainment law review, 17 (1), 39–73. doi:10.5070/LR8171027132

- Ponterotto, J.G. and Reynolds, J.D., 2013. The ‘genius’ and ‘madness’ of Bobby Fischer: his life from three psychobiographical lenses. Review of general psychology, 17 (4), 384–398. doi:10.1037/a0033246

- Potter, A. and Hill, L., 2017. Cultivating global celebrity: Bindi Irwin, FremantleMedia and the commodification of grief. Celebrity studies, 8 (1), 35–50. doi:10.1080/19392397.2016.1200474

- The Queen’s Gambit, 2020. Directed by Scott Frank. USA: Netflix.

- Rawlins, R., 2006. Raising ‘precocious’ children: from nineteenth-century pathology to twentieth-century potential. In: B. Beatty, E.D. Cahan, and J. Grant, eds. When science encounters the child. Education, parenting and child welfare in 20th-century America. New York and London: Teachers College Press, 77–95.

- Reshevsky, S., 1948. Reshevsky on chess. New York: Chess Review.

- Reshevsky, S., 1954. Reshevsky frente al tablero. Buenos Aires: Sopena Argentina.

- Reshevsky, S., 1991. The grand old man. Interviewed by Hanon Russell. Chess Life, 8–12 Nov.

- Richard, G.C., 1920. C’est son avenir qu’a joué hier le petit joueur d’échecs et il a gagné la partie. Le Petit Parisien, 2 July.

- Richet, C., 1901. Note sur un cas remarquable de précocité musicale. In: P. Janet, ed. IVe Congrès International de Psychologie. Compte rendu des séances et texte des mémoires. Paris: Félix Alcan, 93–99.

- Rosen, S., 1981. The economy of the superstars. American economic review, 71 (5), 845–858.

- Rosin, D., 7 July 1920a. Rosin to Marie Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (47).

- Rosin, D., 14 July 1920b. Rosin to Marie Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (47).

- Rosin, D., 18 Oct 1920c. Rosin to Marie Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (47).

- Rzeszewski, J., Aug 1920. Rzeszewski (father) to Bonaparte. Paris: Bibliothèque National de France (Richelieu), [Letter], NAF 28230 (47).

- Sánchez, M.A., 2015. José Raúl Capablanca. A chess biography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Schneider, L., 1918. Les joueurs d’échecs et le Café de la Régence. Le Gaulois, 8 June.

- Schneider, L., 1920. Le jeune Samuel Rzeschewski. Le Gaulois, 18 May.

- Sharples, J., 2017. A cultural history of chess. Minds, machines, and monsters. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Shavinina, L.V., 2010. What does research on child prodigies tell us about talent development and expertise acquisition? Talent development & excellence, 2 (1), 29–49.

- Shea, D.P., 1920. Boy chess wizard prefers a bike. Boston Post, 11 Nov.

- Shuttleworth, S., 2010. The mind of the child. Child development in literature, science, and medicine, 1840–1900. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Slomovitz, P., 1936. Sammy Reshevsky-America’s new champion. The Jewish Criterion, 5 June.

- Soly, J., 1920. Un petit polonais prodige. Samuel Rzeschewski, joueur d’échecs. La Presse, 24 May.

- Stumpf, C., 1897. Un enfant extraordinaire. Revue Scientifique, 7 (11), 336–338.

- Tassinari, E.J., 1993. Reshevsky, Samuel Herman. In: K.T. Jackson, ed. The Scribner encyclopedia of American lives. Volume three, 1991–1993. New York: Charles Scribner’s sons, 440–442.

- Thompson, A.M., 2001. A history of child protection. Back to the future? Family matters, 60 (1), 46–57.

- Turner, G., 2007. The economy of celebrity. In: S. Redmon and S. Holmes, eds. Stardom and celebrity: a reader. London: SAGE, 193–205.

- Un jeune prodige, 1920. Short silent film. France: Pathé.