?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The rapid development of technology has made it easier to distribute products directly, and many enterprises excel at executing a multi-channel strategy to distribute products. The introduction of direct channel adds a new competition dimension to the enterprises. This paper considers three market channel structures: R-Channel, D-Channel and H-Channel. In R-Channel, both new products and remanufactured products are sold through a retailer. In D-Channel, new products are sold through retailers and remanufactured products are sold directly to consumers. In H-Channel, new products are sold through retailers, while remanufactured products through dual channel. Using the game theory, we obtain and analyse the equilibrium prices, market demands and the profits gain under these three settings. At the same time, the influence of consumers’ willingness to pay on the environment performance is researched. Our results show that the manufacturer prefers H-Channel. By introducing the direct channel the manufacturer is always economically better off, but it is not for the retailer. The numerical simulation also confirms the theoretical analysis and shows that H-Channel has advantages of economic benefit and environmental performance. It is feasible for practical application.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of technology, the problem of waste generation and management has become more and more serious in China. To deal with these challenges, remanufacturing is becoming an effective measure. It is defined as the process of disassembling, cleaning, inspecting, replacing and reassembling the components of a part or product to bring the product to a like-new condition (Thom and Rogerson, Citation2002). Remanufacturing consumes the used or the EOL (end-of-life) products, it leads to energy saving, less material consuming and helps reduce the impact on the environment. Evidences can be found that the cost of taking back and remanufacturing a core is 40–60% less than that of brand new product (Giutini and Gaudette Citation2003) and leads to higher profit margins for the producer. However, the maximum profitability is usually unrealised as remanufactured products customarily price these products at 45–65% of comparable new products in order to compete with the sales of new products (Lund and Hauser Citation2010).

For a long time, consumers usually have been going to a physical store to do the actual shopping. In recent years, the social networks have made people realise that they not only have made changes to the life of the people by creating a new life, but also are making changes to the traditional sales method. Quite a lot of enterprises have introduced direct-to-consumer sales channel, such as IBM, Nike, Kodak, Apple, etc. (Wang, Wang, Wang Citation2016, Yu and Wei Citation2016). Academic research from the perspective of channel structures attracts more and more attention.

The channel structure has been described as how products reach to retailers and to final consumers. Most researches (Chiang, Chhajed, and Hess Citation2003; Moriarty and Moran Citation1990, etc.) on distribution channels have studied two channel structures: one is the direct channel and the other is the indirect channel. With the development of information and network technology, enterprises are in face of new opportunities and challenges. Nowadays, enterprises usually distribute products directly to the end consumers in addition to channel intermediaries. For example, Dell uses both retail outlets and mail order to distribute their products.

A large number of literatures focus on channel management. Moriarty and Moran (Citation1990) point out that the hybrid marketing channel may reach potential consumer segments and reduce costs. It is often more efficient than any single channel. Iyer (Citation1998) analyses the channel structure under price and non-price competition. Balasubramanian (Citation1998) and Levary and Mathieu (Citation2000) suggest that a mixed-channel strategy could work well. Chiang, Chhajed, and Hess (Citation2003) construct a game model by engaging in direct sales. They find that direct marketing indirectly increases the flow of profits through the retail channel and helps the manufacture improve overall profitability. Park and Keh (Citation2003) investigate and compare the equilibria in different channel structure and find that firms can achieve higher profits when they engage in hybrid channel. Yao and Liu (Citation2003) consider the diffusion of customers between two channels and conclude that both channels enjoy stable demand under certain conditions. Tsay and Agrawal (Citation2004) consider a single product which can be sold to the end market through a variety of channel strategies. They find that the manufacturer reduces the wholesale price to retain some of the retailer’s selling effort, and both retailer and manufacturer can benefit from the addition of a direct channel. Chen, Chen, and Xiao (Citation2007) study a third option in which the retailer pays a third party in a cost-per-click scheme. Dumrongsiri et al. (Citation2008) present a dual channel supply chain in which the manufacturer sells products to a retailer as well as to consumers directly. Consumers choose the purchase channel based on price and service qualities. They show that adding a direct channel can increase the overall profit in the centralised decision case. Hsiao and Chen (Citation2014) investigate the rationale for the introduction of the Internet channel. They identify the pricing strategies, the capabilities of introducing the Internet channel and the interaction between the channel structures. Hsieh, Chang, and Wu (Citation2014) investigate a two-echelon supply chain which consists of multiple manufacturers, and some of them adopt both retail and direct channels, while the rest only refer to the retail channel. They characterise the price and order decisions to explore the impact of channel structure and parameters on the members׳ decisions and performance. Xu et al. (Citation2014) investigates an analytical framework to analyse the impact of establishing a dual-channel supply chain coordinating contract and the impact of risk tolerance on the manufacturer and retailer’s pricing decisions. They find that the two-way revenue sharing contract not only coordinates the dual-channel supply chain but also achieves a win-win situation. Yan et al. (Citation2015) consider a manufacturer sells new products through a retailer but sells remanufactured products through its own e-channel or subcontracting a third party. They obtain that the manufacturer has less incentive to adopt the e-channel because both the manufacturer and the retailer may be worse off. Wang, Wang, and Wang (Citation2016) consider channel structures for marketing new and remanufactured products. Their results show that the manufacturer prefers to differentiate new and remanufactured products by opening a direct online channel. Furthermore, this paper shows that dual channel strategy benefits the end consumers comparing with the traditional channel strategy. Yu and Wei (Citation2016) address two models in which the manufacturer sells remanufactured products through its own e-channel or through a third party. Their results suggest that the retailer can benefit from the strategy of selling remanufactured products through a manufacturer-owned e-channel. When the saving of remanufacturing cost is pronounced, the manufacturer makes more profit through the e-channel.

The supply chain performance could be better off from the introduction of the direct channel. The hybrid channel is widely used by enterprises. A majority of channel studies in the marketing literature approach the problems from the manufacturers’ perspective, while they ignore the impact of customer channel preference. Thus far, there are only a few research literatures that focus on channel structure from the perspective of boosting the sales of remanufactured products.

Our paper builds on and contributes to the previous literature on the closed-loop supply chain. In the closed-loop supply chain literature, a number of papers focus on the joint pricing of new and remanufactured products, and channel studies in a variety of competitive environments. We make three distinct contributions to this literature. First, our paper extends the channel structures that have been observed in industry. We consider that a manufacturer sells new products through an independent retailer, but with three options for marketing remanufactured products. Second, environmental protection is often put out of the window under the objective of maximum economic benefit. We bring the environmental impact dimension to the comparison of the three market structures. Third, in addition to considering the willingness to pay (WTP) differentiation, our models also capture the channel differentiation. The effects of the channel structures are prominent, and we further find that the manufacturer can make even a larger profit if he chooses a direct distribution channel. The introduction of direct channel is not always necessary detrimental to the retailer. By negotiation and cooperation, it can create a win-win situation. At the same time, dual channel can promote the sale of remanufactured products. The H-Channel model meshes nicely with the themes of energy-saving environmental protection and sustainable economic development. It works not only in the search for knowledge and theories, but also in the development of the remanufacturing industry.

Like many studies, the rest of our paper is organised as follows. The next two sections describe and formulate the models. In Section 4, we derive and analyse the equilibrium solutions of the models. The impacts of the WTP for remanufactured products on the decision variables and the environment performance are presented in Sections 5 and 6, respectively. Section 7 concludes the paper and suggests the future research work.

2. Model description

Our models consist of three channel structures. We assume that the manufacturer has upstream monopoly power, the ability to open a direct channel and a strong say in deciding on the wholesale price. The retailer has to accept the wholesale price. The channel members are independent decision makers and each pursues their own maximum profit.

We assume that all consumers make their purchase decision, product and channel choices by the utility they derive from consumption. The size of the consumer population is normalised to 1. Consumers are heterogeneous in the valuation of products. We denote WTP for a new product is v with cumulative distribution function . To simplify the model, we assume v is uniformly distributed on the interval

. As a result of the uncertain factors of the remanufacturing system, consumers often perceive remanufactured products as being of inferior quality and thus have lower valuation for them. Especially, a direct market provides consumers with only a virtual description of the product, such as text, graphics or web page catalogue, the customer acceptance of direct market is less than traditional market. We capture this by modelling the consumers’ WTP for a remanufactured product is αv if subject to a real inspection and βv when it is obtained from a direct channel (0 < β < α < 1).

Normally, consumers usually pay for shipping and handling in a direct market. We expect that the unit fixed cost of remanufactured products in retail channel c r that includes the cost of manufacturing and logistics is higher than that in direct channel c d :c r > c d . To arouse the enthusiasm of remanufacturing, we assume the unit cost of new products c n (>c r ) and the manufacturer has unconstrained remanufacturable product supply throughout the product life cycle.

Because the manufacturer is the most effective undertaker of product collection activity, we consider the manufacturer collecting EOL products directly from the customers. The cost of collection consists of the fixed cost and variable cost. If the total collection rate is τ and the fixed investment is given by I, , where c is a scaling constant (Savaskan, Bhattacharya, and Wassenhove Citation2004). In addition, the manufacturer pays for the collection of

of EOL products at a per-unit collection cost of A, where

is the total amount of market demand. Therefore, the collection cost incurred by the manufacturer is

. Thus, the total recycling cost is given by:

.

The manufacturer prefers to add a direct channel alongside the existing retail channel. In the hybrid channel, customers can purchase remanufactured products through retailer channel and direct channel. To avoid channel conflict, the manufacturer may try to cooperate with the retailer by negotiating the wholesale price. Here, we keep the wholesale price w

r

fixed in hybrid channel, i.e. .

We now consider the scenarios in which the new products are sold through the retailer, while remanufactured products can be chosen to sell though the retail channels, direct channels or hybrid channels. We use the traditional retail channel as a baseline, and it helps us characterise the effects of some system parameters on our results.

The game has the following sequence of moves. First, the manufacturer acts as the Stackelberg leader. He chooses the channel structure and has the right to price the wholesale price. Then, the manufacturer and the retailer competitively decide the selling price. Finally, consumers make their choices. We represent the interactions in Figures –.

3. Model framework

3.1. Retail channel for remanufactured products (R-Channel)

The consumer utility of a new product and a remanufactured product is denoted as u

n

and u

r

, and can be expressed as ,

. Ceteris paribus, consumers prefer a new product to a remanufactured product, and a remanufactured product to no purchase, i.e. u

n

> u

r

> 0, which is the relevant case for practice. The following demands for new and remanufactured products are based on the product price and the consumer choice of products (Atasu, Sarvary, and Wassenhove Citation2008).

A consumer purchases a new product if u

n

> 0 and u

n

> u

r

. Otherwise, he purchases a remanufactured product if u

r

> 0. From u

n

> u

r

and u

r

> 0, we get the boundary and

, respectively.

So we derive the demand functions of new and remanufactured products.

The manufacturer solves

and the retailer solves

3.2. Direct channel for remanufactured products (D-Channel)

According the consumer utility functions, we obtain the demand functions as follows:

The profit functions can be expressed as follows:

3.3. Hybrid channel for remanufactured products (H-Channel)

It is easy to see that the demand of R-Channel can be written as:

and the demand of D-Channel is

The respective payoff functions are

Note that we assume that the products’ useful lifetime is a single period, remanufactured only once and all cores are in good enough shape for remanufacturing. The resulting equilibrium values are described in the next section.

4. System equilibrium

4.1. Equilibrium

Using the first order condition, we obtain the optimal parameter expressions by backward induction for the three channel structures. The outcomes for each setting are tabulated in .

Table 1. The optimal results of three channels.

Next, we discuss the decisions of the manufacturer and the retailer in equilibrium.

From the results, sensitivity analysis explores the influence of changes in parameters on decision variables.

4.2. Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity with respect to system parameters are illustrated in Proposition 1. We remind that α is the value discount for a remanufactured product and β is the value discount for the direct channel (0 < β < α < 1).

Proposition 1:

(1)

, (2)

, (3)

, (4)

,

(5)

, (6)

, (7)

, (8)

.

Proof:

Let

First, we find that it is a quadratic function of α, and the quadratic term coefficient is greater than zero, so it is a parabola and is pointing up.

Then, the function value of the vertex is .

Therefore, we reach a conclusion that .

That is .

.

.

.

The same procedure may be easily adapted to obtain the other results. The impact of α and β on other decision variables are depicted by images in Section 5.

The WTP for remanufactured products can have significant bearing on the decision variables. As α increases, the wholesale, retail price and market demand for remanufactured products is higher, while the demand for new products is lower.

When WTP for the different channel structure for remanufactured products β is large, the retail price in direct market for remanufactured products is increasing in β. The total demand of remanufactured products in H-Channel is also increasing in β.

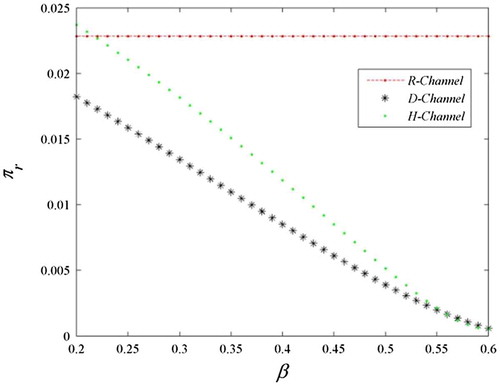

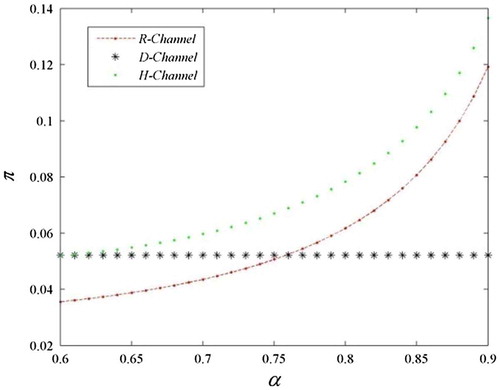

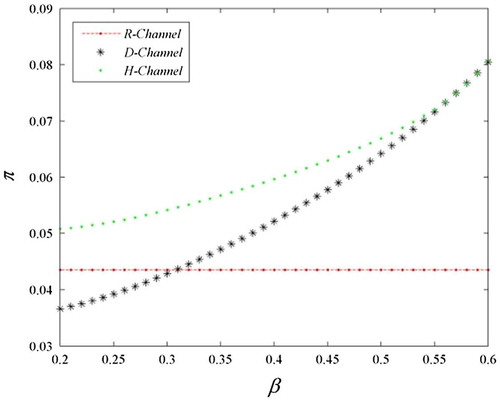

To facilitate the interpretation, the impacts on the profits are explored in Figures –.

4.3. Compare analyses

Through comparing the analytic expression of the optimal solution from the above table, we obtain the following propositions.

Proposition 2:

Proof:

Proposition 3:

.

Proof:

From , we can easily get that

Item 1 of Proposition 2 and item 1 of Proposition 3 indicate that the optimal wholesale price and the market demand for new products in R-Channel and H-Channel are the same. The wholesale price for new products in D-Channel is the lowest.

Proposition 2 compares the equilibrium prices under the three cases. It shows that the pricing equilibrium of new products is the highest under the R-Channel. For remanufactured products, the retail pricing equilibrium is higher under R-Channel than under H-Channel.

Proposition 3 compares the equilibrium demands. For remanufactured products, the total demand under H-Channel is greater than R-Channel. These results reveal that the manufacturer can choose H-Channel to push the sales of remanufactured products and obtain the environmental performance.

Payoff is always a key concern of the channel members. To the question: How do the equilibrium payoffs compare among the three models? We use the graphics to describe the relationships. All parameters influence the channel members’ profit and their corresponding strategies. Section 5 will graphically depict the sensitivity of the above three issues.

5. Numerical experiments

In this section, we carry out numerical experiment and gain intuitive understanding about the changes of price, demand and profit. The numerical values used in this experiment are given in the next. As β varies,

, and when α varies,

In this section, we repeat the same analysis for

and

.

Corresponding to this market situation, the impacts of the parameters α and β on decision variables are illustrated in Figures –. Note that q

r

represents and

in R-Channel, D-Channel and H-Channel, respectively.

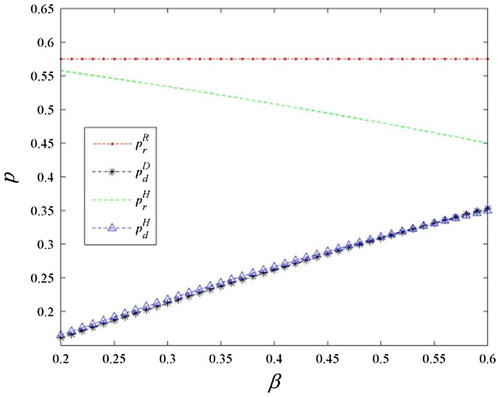

Together, Figures and illustrate the price equilibrium with respect to α and β: Retail prices of new products and remanufactured products are unrelated to β or decreases in β. Comparing the figures we find that the price is highest in the R-Channel. That is to say, the competition between market channels causes to price falling. The introduction of direct channel is beneficial, not detrimental to consumers.

To attract the existing and the potential customers, companies often compete on price. Price sensitive consumers turn to buy low price products. It can help to push the sales of this product, and then improve the merchant’s profit.

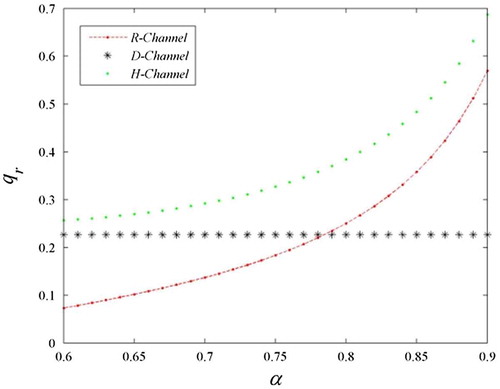

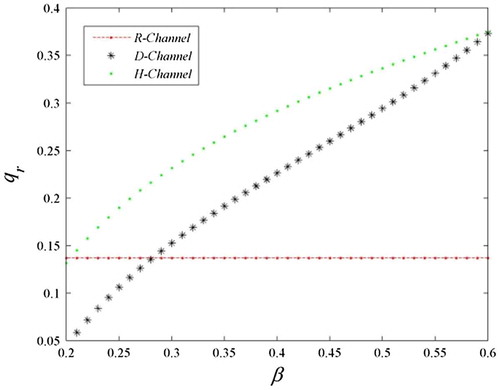

Figures and graphically demonstrate how the market demand depends on the WTP α and β. They indicate that the demand for remanufactured products is the highest in H-Channel. At the same time, we know that the demand for remanufactured products is increasing in α and β.

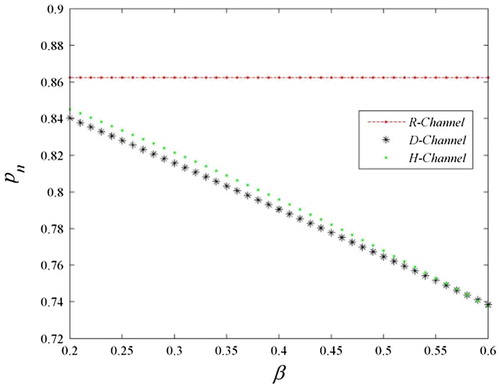

It can be noticed from , the demand for remanufactured products is increasing in β. In other words, the existence of the direct channel can enhance the sales of remanufactured products, and hence promote the development of remanufacturing industry. Also, shows that the hybrid channel for remanufactured products is prior to the direct channel. The sales volume of remanufactured products in R-Channel and D-Channel depends on consumer acceptance of the direct channel. When the acceptance of the Internet channel is higher, D-Channel for remanufactured products is superior to R-Channel. For coordinating the economic effect and environmental impact and realising the sustainable development, the manufacturer can decide to open or close the direct channel. The paper can be used as a guideline for marketing remanufactured products.

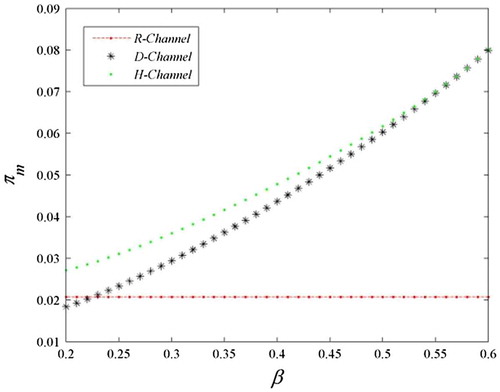

Figures and describe this phenomenon that the direct channel is always beneficial for the manufacturer comparatively to the retailer. As long as the Internet channel exists, the profit of the manufacturer grows rapidly. But it is always worse off for the retailer. An intuitive explanation is as follows. Traditionally, consumers obtain the products usually through the physical stores. And as the WTP β increases, the existence of the direct channel affects the customers’ purchase choices. A sizable majority of consumers turn their attention to direct channel, and it leads to decreases in performance of the retailer. The higher payoff generates the incentive that encourages the manufacturer to open an Internet channel, while the retailer is not willing to do so.

The equilibrium profits of the system are intuitively presented in Figures and . The direct channel for remanufactured products is not an optimal market structure. The system profit is always highest in H-Channel. It will be the preferred marketing channel for the foreseeable future.

In a nutshell, the manufacturer is interested in introducing the direct channel to push customer to buy the remanufactured products, and consequently to increase profit. For all admissible parameter values, the manufacturer is always economically better off when providing the direct channel but not for the retailer.

One mechanism to help alleviate the channel conflict is to use a side payment. As it should be for reducing conflict, this side payment is from the manufacturer to the retailer. Then the manufacturer’s profit would reduce by this amount, while the retailer’s profit would increase by the same amount. Only if the retailer may be compensated by some side payments from the manufacturer, does he allow R-Channel to compete with the other two channels.

6. Environmental performance

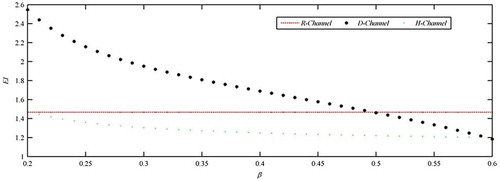

In this section, we extend to investigate the environmental performance of the three channel structures. The per unit disposal impact of a new product and a remanufactured product is denoted by n and r, respectively (Agrawal et al. Citation2012; Yan et al. Citation2015). Since remanufacturing requires less material and energy than manufacturing new products, we further assume that n > r. The environmental impacts of three models are illustrated in .

After analysing Figures –, we come to the conclusion that H-Channel is desirable in the closed-loop supply chain system. The benefits are economic, profitable and environmental, which all comply with the idea of ecosystems sustainably.

7. Conclusion and future research

The characteristic of remanufactured products and the WTP differentiate for channel structures are considered in this paper. Our focus is on the influences of the type of distribute channels instead of the channel coordinator. One of the major aspects in our model is that, in addition to capturing the WTP differentiation, it also models the channel differentiation. We examine the effects of the channel structures and find that the manufacturer can make even a larger profit if he chooses a hybrid channel structure. At the same time, hybrid channel can promote the sales of remanufactured products, i.e. multi-channel for remanufactured products is an effective strategy. This is of vital importance in efforts to promote the change in the pattern of economic growth and increase energy conservation and environmental protection. Some results in this paper are quite useful, and establish a benchmark for the future research in this field.

However, a limitation of this paper is the lack of empirical analysis that would substantiate the analytical results. Nonetheless, we believe this paper can contribute towards our understanding of manufacturer’s channel choosing. There are plenty of rooms for further research, such as the effect of the power of the retailer in the model, the value-added behaviour for products and how to find out the optimum solutions from the retailer’s and consumers’ perspective. We hope that this research sets up the benchmark comparison for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by A Project of Shandong Province Higher Educational Science and Technology Programme [grant number J17KA174]; The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number NP 2016303], [grant number NS 2017057]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 71372122], [grant number 71672166].

Notes on contributors

Xi-Gao Shao holds a PhD in Probability Theory. His research interests include probability theory and supply chain management

Bi-Feng Liao is a doctoral student. Her research interests are supply chain management and game theory.

Bang-Yi Li is doctor of management, doctoral tutor, professor. His research interests include supply chain research and producer responsibility.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor, the referees and Professor Shu-yun Wang for their helpful comments and suggestions.

References

- Agrawal, V. V., M. Ferguson, L. B. Toktay, and V. M. Thomas. 2012. “Is Leasing Greener than Selling?” Management Science 58 (3): 523–533. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1110.1428.

- Atasu, A., M. Sarvary, and L. N. V. Wassenhove. 2008. “Remanufacturing as a Marketing Strategy.” Management Science 54 (10): 1731–1746. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1080.0893.

- Balasubramanian, S. 1998. “Mail versus Mall: A Strategic Analysis of Competition between Direct Marketers and Conventional Retailers.” Marketing Science 17 (3): 181–195.10.1287/mksc.17.3.181

- Chen, F. Y., J. Chen, and Y. Xiao. 2007. “Optimal Control of Selling Channels for an Online Retailer with Cost-per-Click Payments and Seasonal Products.” Production Operation Management 16 (3): 292–305. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2007.tb00260.x.

- Chiang, W. K., D. Chhajed, and J. D. Hess. 2003. “Direct Marketing, Indirect Profits: A Strategic Analysis of Dual-Channel Supply-Chain Design.” Management Science 49 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1287/mnsc.49.1.1.12749.

- Dumrongsiri, A., M. Fan, A. Jain, and K. Moinzadeh. 2008. “A Supply Chain Model with Direct and Retail Channels.” European Journal of Operational Research 187 (3): 691–718. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2006.05.044.

- Giutini, R., and K. Gaudette. 2003. “Remanufacturing: The Next Great Opportunity for Boosting US Productivity.” Business Horizons 46 (6): 41–48.10.1016/S0007-6813(03)00087-9

- Hsiao, L., and Y. J. Chen. 2014. “Strategic Motive for Introducing Internet Channels in a Supply Chain.” Production and Operations Management 23 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1111/poms.12051.

- Hsieh, C. C., Y. L. Chang, and C. H. Wu. 2014. “Competitive Pricing and Ordering Decisions in a Multiple-Channel Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 154 (4): 156–165. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.04.024.

- Iyer, G. 1998. “Coordinating Channels under Price and Non-Price Competition.” Marketing Science 17 (4): 338–355.10.1287/mksc.17.4.338

- Levary, R., and R. G. Mathieu. 2000. “Hybrid Retail: Integrating E-Commerce and Physical Stores.” Industrial Management 42 (5): 6–13.

- Lund, R. T., and W. M. Hauser. 2010. “Remanufacturing - an American Perspective.” International Conference on Responsive Manufacturing - Green Manufacturing IEEE 2010: 1-6. doi.:10.1049/cp.2010.0404.

- Moriarty, R. T., and U. Moran. 1990. “Managing Hybrid Marketing Systems.” Harvard Business Review 68 (6): 146–155.

- Park, S. Y., and H. T. Keh. 2003. “Modeling Hybrid Distribution Channels: A Game Theoretic Analysis.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 10 (3): 155–167.10.1016/S0969-6989(03)00007-9

- Savaskan, R. C., S. Bhattacharya, and L. N. V. Wassenhove. 2004. “Closed-Loop Supply Chain Models with Product Remanufacturing.” Management Science 50 (2): 239–252. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1030.0186.

- Thom, B. K., and P. Rogerson. 2002. “Take It Back.” IIE Solutions 2002: 34–40.

- Tsay, A. A., and N. Agrawal. 2004. “Channel Conflict and Coordination in the E-Commerce Age.” Production and Operations Management 13 (1): 93–110. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2004.tb00147.x.

- Wang, Z. B., Y. Y. Wang, and J. C. Wang. 2016. “Optimal Distribution Channel Strategy for New and Remanufactured Products.” Electronic Commerce Research 16 (2): 269–295. doi:10.1007/s10660-016-9225-8.

- Xu, G. A., B. Dan, X. M. Zhang, and C. Liu. 2014. “Coordinating a Dual-Channel Supply Chain with Risk-Averse under a Two-Way Revenue Sharing Contract.” International Journal of Production Economics 147 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.09.012.

- Yan, W., Y. Xiong, Z. Xiong, and N. Guo. 2015. “Bricks Vs. Clicks: Which is Better for Marketing Remanufactured Products?” European Journal of Operational Research 242 (2): 434–444. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2014.10.023.

- Yao, D., and J. Liu. 2003. “Channel Redistribution with Direct Selling.” European Journal of Operational Research 144 (3): 646–658. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00137-6.

- Yu, X., and Y. Wei. 2016. “Implications of Channel Structure for Marketing Remanufactured Products.” European Journal of Industrial Engineering 10 (1): 126–144.