?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the coordination of green level improvement in a manufacturing supply chain, and analyses the impact of a retailer’ s undertaking a manufacturer’s green R&D costs on stability of the green supply chain. Our research motivation sources from manufacturing enterprises in supply chains, which have been increasingly required to reduce carbon footprint and produce green products. With the help of game theory, we first present green supply chain models without revenue-sharing contracts (RSCs) in centralised and decentralised scenarios. Then, pure RSC and revenue sharing through bargaining contract (RSB) are discussed in decentralised scenarios, the retailer decides the revenue-sharing rate to the manufacturer in RS, and in RSB the retailer and the manufacturer jointly determine the ratio by negotiation. It is found that both contracts can improve the green level of the supply chain, especially RSB. However, RSB makes the green supply chain uncoordinated because it harms the retailer’s benefits. Therefore, this paper contributes to efforts of proposing two kinds of improved RSB, which can promote not only the continual cooperation of supply chain members, but also the goal of improving the green level. Finally, we exert numerical examples under different RSCs to verify the results.

1. Introduction

The main driving force for economic prosperity is manufacturing industry, and manufacturing added value boosted its proportion of global GDP from 15.3% in 2000 to 16.5% in 2018 (UN and GA Citation2019). Meanwhile, with the rapid growth of economy, the public around the world gradually is aware that the development of manufacturing industry can’t be separated from sustainability (Bruntland Citation1987; Linton, Klassen, and Jayaraman Citation2007). In addition, a great number of challenges facing humanity, such as environmental pollution and climate change, can only be solved at the global level by promoting sustainable development goals and targets, which are the principal components of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development released by UN DESA (Citation2016). Following the targets, switching to a sustainable planet through making green products has proven popular (Madani and Rasti-Barzoki Citation2017). In reality, Tesla’s innovative design of a series of high-quality and environment-friendly electric vehicles caters to the majority of government agencies and people that address the pressing global warming problem, although the carbon footprint of the products in the production and recycling phase remains high. Many scholars (Navinchandra Citation1990; Sarkis Citation2001; Gimenez, Sierra, and Rodon Citation2012; Ahi and Searcy Citation2013; Carter and Liane Easton Citation2015) have long been studying the integration of environmental sustainability and supply chain, which can be called green supply chain.

In practice, the governments have responded significantly to the 2030 Agenda and given more emphasis to the harmonious development of economy, society and environment (UN and GA Citation2019). In recent years, many severe environmental regulations have been promulgated. At the same time, with the advent of the global green initiatives, manufacturing enterprises have to take measures to improve environmental performance for their image. Specifically, they need to ensure that products and services are green, or produced by environmental-friendly processes, and can be identified by eco-labels or energy efficiency labels of the third-party (Rao and Holt Citation2005; Murali, Lim, and Petruzzi Citation2019). Therefore, as mentioned in sustainable development goals 8.4, 9.4, 12.4 and 12.5 (DESA Citation2016), it is high time for them to apply green supply chain management, which passes beyond the traditional supply chain management issue to emphasise the balance issue between environment and efficiency (Liu Citation2018; Hong and Guo Citation2019), and dissociate economic growth from environmental deterioration. It involves the long-term improvement of enterprises’ economic goals, and helps managers to understand that green initiatives is not for short-term public praise, but for a decade or more of enterprises’ prosperity (Carter and Liane Easton Citation2015), which requires the common awareness and collective actions of supply chain members. However, Many studies (Esfahbodi, Zhang, and Watson Citation2016; Raj, Biswas, and Srivastava Citation2018) have shown that the investment in greening, which means that the reduction of carbon footprints and negative environmental impacts of product life cycle are a big cost burden for the suppliers (i.e. manufacturing enterprises), meanwhile, the retailers can gain more profits because of the improvement of green level of products, which will lead to the reduction of the suppliers’ incentives to invest in greening (Ghosh and Shah Citation2012; Zhu and Yuanjie Citation2017).

Hence, the above discussions on the continual stability of green manufacturing supply chains can extend the research questions as follows: (i) referring to SDGs 9.4, 12.4 and 12.5, manufacturing enterprises need to adopt clean and environment-friendly technology to minimise the negative impact of products on human health and environment in life cycle (DESA Citation2016). Therefore, enterprises are bound to face a trade-off between SDGs and economic efficiency, in the scenarios of decentralised and centralised decision-making, what green level and price decisions will the manufacturing enterprises make for a green supply chain, and what are the benefits for the supply chain members? (ii) Actually, the centralised decision-making is just a benchmark while the decentralised decision-making in a manufacturing supply chain is widespread. Can revenue-sharing contracts (RSCs) motivate a retailer and a manufacturer to make green decision-making and improve the whole supply chain efficiency? (iii) RSCs refer to solutions about the fair distribution of supply chain profits, namely, a certain proportion of sales revenue shared by the retailer can make the manufacturer ease the cost burden of improving the green level, and lower the wholesale price (Cachon and Lariviere Citation2005). We propose a pure RSC and a revenue sharing through bargaining contract (RSB). Under RSC, the retailer decides directly the revenue-sharing rate due to the manufacturer. Under RSB, by contrast, the manufacturer tries his best to negotiate with the retailer to jointly assign revenue-sharing rates. What are the impacts of different RSCs on the green level, product price and benefits of supply chain members? Are the contracts useful in motivating the players to continue greening? If not, what should be done? (iv) How does consumer’s green preference affect the green level of the manufacturing supply chain and the profitability of players and the supply chain?

The rest of this paper is organised as below. In Section 2, we present contribution of this paper after reviewing the relevant literature. In Section 3, we propose the problem description and the model hypothesis. In Section 4, we compare green supply chain models with and without RSCs and RSB in the centralised and decentralised decision-making scenarios, and demonstrate the impact of different RSCs on the green supply chain decisions. In Section 5, we develop improved RSB models for achieving a higher greening of the green supply chain, which can also encourage the players to enhance cooperation for more benefits. In Section 6, we present numerical examples and sensitivity analysis of the models. In Section 7, we draw a conclusion based on the models and point out their possible limitations and research directions in the future.

2. Literature review

In this paper, we mainly review the relevant literature in two streams based on the research approach. The first stream focuses on greening problems in supply chain management, which comes from greening efforts of manufacturing enterprises. With the rising public environmental awareness, green supply chain has become an increasingly hot research area. Sarkis, Zhu, and Lai (Citation2011), Fahimnia, Sarkis, and Davarzani (Citation2015) make thorough reviews of the literature on green supply chain management. For promoting green supply chain, Rao and Holt (Citation2005) use empirical evaluation to explore the relationship between green supply chain management and improvement of enterprise competitiveness and economic performance. Based on theories of innovation diffusion and ecological modernisation, Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai (Citation2012) show the main reasons why Chinese manufacturers are unwilling to adopt green supply chain management by questionnaires. The case studies are used to discuss driving factors and significance of green supply chain practices (Azevedo, Carvalho, and Cruz Machado Citation2011; Diabat and Govindan Citation2011). The green supply chain is also discussed from the perspectives of remanufacturing and reverse logistics (Abbey et al. Citation2015; Chung and Wee Citation2011; Weraikat, Zanjani, and Lehoux Citation2016). Scholars (Li et al. Citation2016; Sheu and Chen Citation2012; Zhao et al. Citation2012; Zhu and Yuanjie Citation2017) also begin to discuss a green supply chain under different economic backgrounds and put forward strategies based on game theory framework. The previous studies focus on the integration of environment and economy in a green supply chain, but less attention is paid to the practicality of coordinated green supply chain from the quantitative aspect, which will help understand the players’ awareness and individual actions.

The second stream addresses literature about solving the channel coordination in supply chain management. As our work concerns the challenges sourcing from green R&D costs and demand with consumer green preferences, we will concentrate on operational management literature, which has solved those familiar issues by contracts design. In fact, scholars like Tsay, Nahmias, and Narendra (Citation1999), Cachon (Citation2003); Cachon and Lariviere (Citation2005) have made comprehensive overviews of supply chain coordination in which contracts for different environments have been mentioned, such as price-discount contract, quantity flexibility contract, buy-back contract, cost sharing contract, RSC and so on. Revenue sharing and cost sharing are the most familiar coordination contracts in current literature. Ghosh and Shah (Citation2015) extend the impact of cost-sharing and cost-sharing with bargaining on product green level, market price and profit in a supply chain. In the context of low-carbon, Wang, Zhao, and Longfei (Citation2016) achieve the goal of reducing carbon emissions through cost sharing contract, and improve the performance of players by Pareto. Their result is robust under the setting of the retailer-led or the vertical power. Chakraborty, Chauhan, and Ouhimmou (Citation2019) explore that a supply chain with one retailer and two competing manufacturers will get profits by collaborative product quality improvement strategies in cost sharing contract. RSCs are considered to be more efficient than traditional supply chain contracts in coordinating profit distribution and achieving performance (Cachon and Lariviere Citation2005; Veen and Venugopal Citation2005). Raza (Citation2018) applies revenue-sharing contract to inventory pricing and corporate social responsibility investments decisions in a manufacturing supply chain, and uses mechanisms to motivate supply chain members who successfully achieve corporate performance and profitability while undertaking CRS. Considering the consumer’s sensitivity to green products, Song and Gao (Citation2018) propose the green supply chain coordination under revenue sharing and bargaining RSC. Most studies above launch the discussions in the framework of supply chain coordination contracts. They attach importance to the impact of different contracts on the green level of supply chain, and reach a Pareto improvement of supply chain members’ benefits by cost sharing or revenue sharing, but rarely make an analysis about the possible losses of supply chain members’ undertaking R&D costs to raise further green level when bargaining is applied. Bargaining contracts will a great benefit to improving the green level and the total revenue of the supply chain (Bhaskaran and Krishnan Citation2009), but the unequal bargaining power damages the individual interests which will ultimately lead to the uncoordinated green supply chain.

The paper is enlightened by Ghosh and Shah (Citation2015) and Song and Gao (Citation2018) who assume that the bargaining contracts will be powerful to promote the green level of products and coordinate a green supply chain. In a manufacturing supply chain with consumer preference, does revenue sharing have significant effects on the realisation of green supply chain, especially bargaining revenue sharing? For filling the gap in the studies, we model different RSCs to investigate supply chain members’ decision-making and negotiation, and discuss whether the contracts are beneficial to the green supply chain or not. The results show that RSC can improve green level of the products and the members’ profits and realise the green supply chain. RSB widely considered to be a useful strategy in literature (Bhaskaran and Krishnan Citation2009; Ghosh and Shah Citation2012; Song and Gao Citation2018) will account for a higher green level of the supply chain. However, the contract can’t achieve stability of the supply chain because it seriously damages the retailer’s benefits. Furthermore, we contribute to develop the improved RSB solutions for higher greening, which is close to the ideal, and also realises Pareto improvement of the players’ benefits in manufacturing supply chain.

3. Problem description and hypothesis

We consider a two-echelon green manufacturing supply chain including a manufacturer and a retailer. The manufacturer delivers all green products to the retailer at a wholesale price , while the retailer sells to consumers at a price

through the retailing channel, which also equals the market price because of the uniqueness of the retailer. For convenience’s sake, the following assumptions are listed.

The members in the green supply chain have a complete symmetry of information and common knowledge. At the same time, they are risk neutral.

Green products will incur fixed R&D costs. In fact, a lot of ‘greening’ activities directly lead to cost reductions and efficiency gains for long run, which brings the enterprises a great economic burden and weakens their competitive advantage for a short term. Therefore, it is necessary to externalise the R&D expenses from the perspective of manufacturing enterprises.

stands for green level of the product, which also is equal to greening level in the supply chain. In order to ensure that consumers with environmental awareness and green preferences can distinguish green products, the manufacturers need to determine the value of

, and the higher it is, the more environment-friendly the products are. In practice, labels for energy efficiency, carbon and harmful substance content are usually used to reflect and estimate the green level of different products. Meanwhile, the increase of green level will generate huge R&D investments. According to the study of Bhaskaran and Krishnan (Citation2009) and Banker, Khosla, and Sinha (Citation1998), we consider the investments as

which means the greening costs will increase sharply with

and improving

becomes more difficult, where

represents the green investment level coefficient which reflects the unit cost brought by the convex growth of

. Similarly, the bigger

is, the higher greening investments are.

Manufacturers play a leading role in the market. Because the threshold of manufacturing market represented by steel, automobile and non-ferrous metals industry is high, there is often only one manufacturer who can dominate over these sectors who determines

and

firstly, then the retailer decides unit product profits

.

Similar to the methods of Choi (Citation1991) and Song and Gao (Citation2018), the market demand for the green product is a linear function about

and

, which is formulated as

.

Where

indicates the total market potential,

is the price sensitivity coefficient which reflects rational consumer response to price, and

represents consumer sensitivity coefficient to green level which directly reflects consumer preferences and measures the market response to the improvement. The higher

is, the more market demand will be, while the opposite is true for

. Essentially, the equation is a deterministic linear demand expression after normalisation, which still traces the dependence of demand on price and green level in a supply chain.

The retailer shares sales revenue with the manufacturer through contracts while indirectly undertaking R&D costs for improving supply chain profit, green level of the products for more profit distribution in the supply chain.

In addition, the variable cost of the product has nothing to do with

, and the manufacturer’s per product profit is

. Besides, other costs are not considered. Hence, product price consists of

and

, namely,

. To ensure that the following discussion is economically meaningful, it is assumed that the demand function and profit function are positive where

.

Thus, profit functions of the manufacturer, the retailer and the whole green supply chain in manufacturing industry are given as follows:

Furthermore, the symbols and notations mentioned in the model are summarised as follows ().

Table 1. Symbols and notations.

4. Model formulation and solution procedures

In this part, models with different scenarios of revenue sharing are formulated and solved to analyse how the retailer’s behaviour of sharing the manufacturer’s green R&D costs affects stability of the green supply chain, including centralised and decentralised decision-making models without RSCs including RSC and RSB. The parameters of supply chain profit, product greening level and members’ profit under equilibrium are compared.

4.1. Model of green supply chain without revenue sharing

In order to compare with the green supply chain models under RSC and RSB, the non-revenue sharing green supply chain models are first discussed which (Ghosh and Shah Citation2012; Zhu and Yuanjie Citation2017; Chakraborty, Chauhan, and Ouhimmou Citation2019; Li et al. Citation2019; Liu Citation2018) are often used as benchmarks to evaluate the merits and demerits of other coordination contracts.

4.1.1. Centralised decision-making models

In this scenario, the manufacturer who has retail channels independently decides the optimal and

, and the profits of the manufacturer are equal to those of the green supply chain. The profit function can be shown as:

Using the second-order condition and partial derivative in EquationEq. (4(4)

(4) ), there are

, and

, where

if

. The Hessian matrix is negative definite and the function is joint strictly convex which also has a maximum. The first derivative of

and

of EquationEq. (4)

(4)

(4) is obtained. When it is equal to zero, the optimal values are obtained. We get

And

If and

are of economic significance, the following parameters must be satisfied:

, and

. Hence, the optimal parameters in the centralised supply chain model are shown in .

Table 2. Equilibrium under centralised and decentralised.

4.1.2. Decentralised decision-making model

The manufacturer and the retailer are independent decision-makers who pursue maximum individual profits. Using the second-order condition of EquationEq. (2(2)

(2) ), we can get

. Therefore, the retailer function has a maximum if

, and

Substituting EquationEq. (7)(7)

(7) into EquationEq. (1

(1)

(1) ), we use the second-order condition and partial derivative of the manufacturer profit function and get

and

which mean negative definite, then the profit function has a maximum. Similar to processing method in centralised model, the optimal parameters of decentralised decision-making can be obtained ().

4.2. Model of green manufacturing supply chain with revenue sharing

The implementation of green supply chain in the absence of cooperation with the retailer will reduce individual profits. The manufacturer is motivated to continuously cut down on the investment expenses of green R&D, which will ultimately lower the green level of the supply chain. Therefore, RSCs are introduced, which encourage the manufacturer and the retailer to cooperate for improving greening of the supply chain and pursuing more benefits.

4.2.1. Model of green supply chain in RS

If RSC is adopted, the manufacturer will use a lower to induce the retailer to share sale revenue, while the retailer will agree on the contract for benefits. Then, the manufacturer obtains

of the retailer’s sharing revenue, and the retailer’s surplus share is

, where

. The manufacturer’s costs in green R&D are reduced through revenue sharing, and the model can be formulated as below:

At this time, the scenario becomes the action choice between the manufacturer and the retailer in RS, which still is a Stackelberg game in which the manufacturer acts before the retailer. Following the backward induction, we use the second-order condition of EquationEq. (9)(9)

(9) and calculate

. The retailer function is maximum when

, and we get

. The second-order condition and partial derivative of the manufacturer profit function are gained by substituting

into EquationEq. (8

(8)

(8) ), there are

and

. The function is joint strictly convex when

, and the manufacturer’s profit is maximum if

and

, where

Substituting the values of EquationEq. (10)(10)

(10) into

,we get

For optimisation, the revenue-sharing ratio is determined when the retailer’s profit is maximum, and are substituted into EquationEq. (9)

(9)

(9) while

is a function of

. We calculate the second-order condition of

and get

.

is maximum if

and

, which will result in

. Further, we get the optimal parameters under the equilibrium ().

Table 3. Equilibrium value in revenue-sharing contracts.

4.2.2. Model of green supply chain in RSB

Revenue-sharing rate in RSC is entirely determined by the retailer, but if the retailer and the manufacturer cooperate well under information sharing, they negotiate the retailer’s revenue-sharing ratio through RSB. In this scenario, the manufacturer will encourage the retailer to increase the proportion of revenue sharing by promising to further lower the wholesale price and raise the green level, while the retailers will make concessions to gain more market share and supply chain profit distribution. As a result, they will bargain about the revenue-sharing ratio. It is assumed that the bargaining process follows Nash bargaining game and the goal is to maximise the profits of the green supply chain. The bargaining process can be described in the following model:

The revenue-sharing ratio is determined by Nash bargaining, where

. With perfect information, the manufacturer first determines

and

based on

and the retailer response function, while the retailer also decides the profit

on the basis of

,

and

.

Using the analytical framework of RS, we can get that is a function of

and

, then profit functions of the supply chain members can be expressed as:

Based on EquationEq. (12(12)

(12) ),

is a function of

. We can get

If or

,

will run up to a maximum when

, namely,

, and the optimal parameters under the equilibrium are listed in . Based on and , the following propositions can be drawn by comparing the green supply chain models of centralised decision-making, decentralised decision-making, RSC and RSB.

Proposition 1. The optimal green level of the supply chain satisfies the following order: .

Proof: from and

, we get

and

.

Here, . And we get

, and

. Thus, Proposition 1 can be deduced, namely,

.

In particular, the proofs of Propositions 2–7 are similar to Proposition 1.

It can be seen from proposition 1 that the green level will reach the highest under the centralised decision-making mode, but it is the most ideal result for reference. In stark contrast, the decentralised decision-making mode without revenue sharing has the lowest green level due to the influence of double marginal effect. At the same time, RSCs are conducive to improving the green level of manufacturing supply chain, especially in the case of RSB.

Proposition 2. The optimal wholesale price of green products satisfies the following order: .

Proposition 2 shows that the wholesale price of green products is the highest in the decentralised decision-making model and the lowest in RSB. The reason for this result is that decentralised decision-making of green supply chain has the lowest operational efficiency and is most significantly affected by the dual marginal effect. In a revenue-sharing supply chain, the retailer indirectly shares the green R&D costs due to the manufacturer, alleviates the negative impact of the dual marginal effect, and plays a direct role in encouraging the manufacturer to reduce the wholesale price.

Proposition 3. The optimal retailer’s unit profit of green product is in the order: .

Proposition 3 suggests that the retailer’s optimal unit profit of green product is the lowest in the decentralised model and the highest in RSB. The reason is largely due to the fact that the wholesale price under the decentralised is the highest, which makes the retailer get the least unit revenue from selling green products, while the wholesale price in the revenue-sharing supply chain is relatively low, which leads to the increase of the retailer’s revenue, especially in RSB.

Proposition 4. In RSC and RSB, the proportion of revenue sharing satisfies: .

Proposition 4 shows that the retailer shares a larger proportion of revenue in RSB than that in RS. The reason is that in order to achieve a higher green level and a lower wholesale price in RSB, the retailer can only stimulate the manufacturer by indirectly sharing more green R&D costs, which ultimately shows an increase in the proportion of revenue sharing.

Proposition 5. The optimal manufacturer’s profits follow the order: .

From proposition 5, it is observed that the manufacturer’s optimal profits are the lowest in the decentralised model and the highest in RSB. The main reason is that the wholesale price in the decentralised is the highest. On the other side, the retailer sells the products at the highest price, which leads to the lowest sales amount and ultimately makes the manufacturer get the lowest profits, while the opposite is true in the revenue-sharing supply chain. Meanwhile, under RSB, the manufacturer’s profits increase to the peak with the retailer’s revenue-sharing rate.

Proposition 6. The retailer’s optimal profits satisfy the order: .

Proposition 6 shows that the optimal profits of the retailer in RSC are higher than that in decentralised model, while the optimal retailer’s profits in RSB are lower than those in RS. The reason is that sharing revenue can reduce the wholesale price, and the retailer compensates for the loss of sharing revenue by increasing the price to gain more profits. However, as the share ratio increases to the peak, the retailer can compensate no more for the loss and ultimately reduce individual profits.

Proposition 7. The optimal profits of green supply chain are in the order: .

According to Proposition 7, the profits level of green supply chain is increased by introducing RSCs compared with the decentralised green supply chain without revenue sharing. The optimal profits in RSC and RSB account for and

, respectively, of the profits in the centralised model. The proposition shows that RSCs have a significant and positive effect on improving the profits of the supply chain which also are more conducive to promoting the green level of supply chain in manufacturing industry.

Corollary 1. If , the profits of the manufacturer, the retailer and the supply chain are functions of

in RSB, where

, the functions respectively are monotonic increasing, monotonic decreasing and monotonic increasing functions and are shown as follows

.

Proof: From , and Eqs. (13) and (14),

We get ,

and . Because

,

we get and

.

From , we get

, and

. Thus,

.

From Propositions 1–7, interestingly, we can see that the optimal green level of the supply chain with RSCs are higher than that in the decentralised supply chain without the contracts, especially RSB, in which the manufacturer obtains more profits than in RS. On the contrary, according to propositions 6–7 and corollary 1, it is observed that the retailer’s profits in RSB are always lower than in RS, and even lower than in the decentralised supply chain without revenue sharing. In fact, Corollary 1 shows that the revenue-sharing ratio and the profits of the manufacturer and the supply chain are increasing, while those of the retailer are decreasing. This means as well that the profits of supply chain will increase further under RSB while the profit distribution is unfair to the supply chain members, as the manufacturer will benefit and the retailer will suffer. The inconsistency of supply chain members’ awareness and collective actions will make the green supply chain uncoordinated, namely, the retailer intends to use RSC for profits, while the manufacturer is under pressure to balance the green level and profits and prefers RSB.

5. Improved model of revenue sharing with bargaining

Because the green level and overall profit of green manufacturing supply chain in RSB are the closest to the centralised model compared with other models, we consider introducing an effective mechanism to reallocate the profits of the supply chain under RSB (namely, improved RSB) so as to realise and promote continual stability of the green supply chain, which means that the manufacturer and the retailer will act collectively for a higher green level while maintaining their common awareness.

5.1. Improved RSB based on two-part tariff contract

From Proposition 2, we can see that the retailer in RSC bears the highest proportion of the manufacturer’s green R&D costs, which seriously damages the retailer’s profits. However, due to the advantages of RSB, two-part tariff contract can be introduced to improve RSB. The specific idea is described as follows: the manufacturer in RSB firstly pays a certain amount of fees to the retailer for him to decide whether to follow or not. The retailer’s incentive is that the profit gained must be higher than that in RS, so the following parameters must be satisfied, namely,

or

.

At the same time, the manufacturer has the motivation to propose the improved contract when the conditions are in place where or

.

Proposition 9. The members of the supply chain accept two-part tariff contract and have the incentive to act as if and only if . Eventually, the supply chain not only improves the green level but also achieves continual stability under improved RSB. Where

represents the maximum amount of prepaid expenses to the retailer and

the minimum, and

.

5.2. Improved RSB based on profit sharing contract

In order to constantly maintain the higher green level in the manufacturing supply chain, profit sharing contract can be incorporated into RSB for improved RSB. This method is meant for distributing the total profit of green supply chain to the supply chain members based on the proportion, and the retailer gains the total profit ratio

while the manufacturer

. In particular, the retailer will adopt the contract if the conditions are met where

and

.

Simultaneously, the manufacturer’s motive for enacting the contract needs to satisfy the conditions that his profits through profit distribution are greater than or equal to those obtained in RS, where , and

.

Proposition 10. If and only if , the supply chain members reach the profit sharing contract, which not only raises green level of the manufacturing supply chain in improved RSB, but also achieves the consistency of awareness and collective actions.

6. Numerical examples and sensitivity analysis

By theoretical analysis, it is known that the changes of price sensitivity coefficient , consumer sensitivity coefficient to green level

and the green investment level coefficient

greatly influence the solutions to different models. Specially, if the green supply chain in manufacturing industry is based on consumer green preference which means that products with high green level are usually more popular with consumers, the manufacturer and the retailer will have an incentive to improve the green level of products, which will result in expensive R&D costs. Hence, this paper takes

as the decision variable, verifies and explains the influence of retailer’s undertaking manufacturer’s green R&D costs by RSCs on the stability of green supply chain in manufacturing industry by numerical analysis. Where

, the value of

is varied from 0 to 1 for ensuring the economic significance of the analysis.

6.1. Analysis of model solutions under non-revenue sharing and revenue sharing

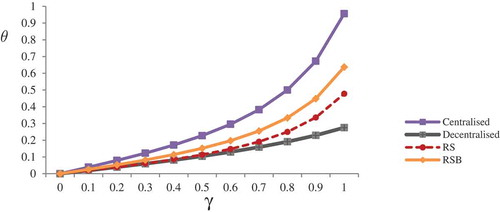

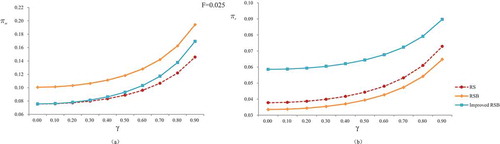

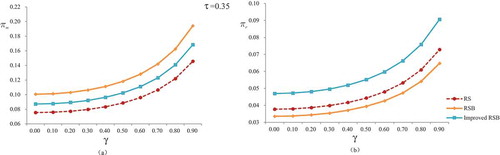

From , it is observed that the green level of products arises monotonously with the increase of . This gives us inspiration that the manufacturer will strive to improve it in market competition if consumer green preference increases. It also explains the external motivation of some manufacturing industries actively to establish green supply chain besides the reasons for the stringent environmental regulations. Meanwhile, the scenario ranking of greening level is in the descending order as below, centralised decision-making model, RSB, RSC and decentralised decision-making model, which illustrates that RSCs can bring higher green level.

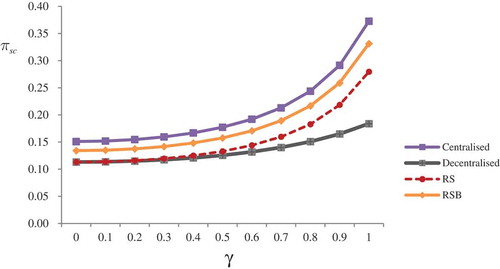

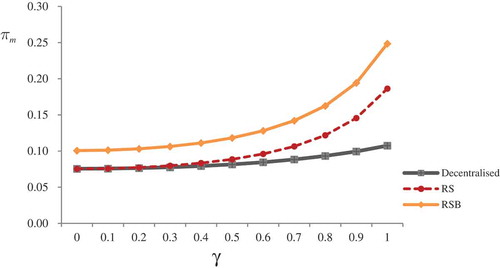

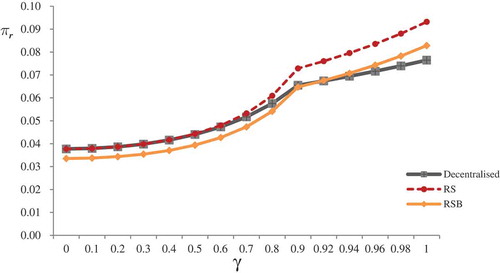

From –, we see that the profits of the manufacturer and the green supply chain in three different supply chain models will rise with the increase of , and the increase effect is the worst in the decentralised and the best in RSB. At the same time, the retailer’s profits increase gradually with the enhancement of

in RS. The retailer’s profits are higher in RSB than in the decentralised only when

satisfies the condition where

, namely,

, otherwise the retailer’s profits in RSB will be lower than those in other models. The result of numerical analysis confirms that RSB can improve the green level of the products, which cannot sustain the green supply chain. Obviously, consumer sensitivity coefficient to green level

has a positive impact on improving overall supply chain profits and environment performance, which is also very obvious in numerical analysis case above. This fact also shows that the green preferred consumer market creates opportunities for the players in the manufacturing supply chain to carry out green initiatives, which will bring more benefits to the supply chain members if the design of coordination mechanism is appropriate.

6.2. Analysis of improved RSB

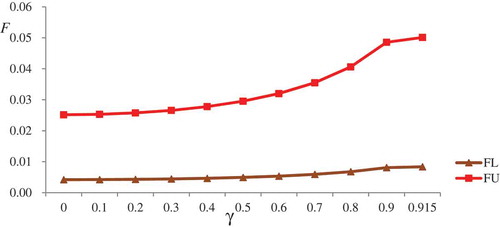

In addition, it is observed from that the upper and the lower limits of the manufacturer’s prepaid expenses constantly rise with the increase of

in improved RSB based on two-part tariff contract. If

, then the relationship between the supply chain members’ profits and

before and after improved RSB based on two-part tariff can be drawn as in . Meanwhile, the parameter

in improved RSB based on profit sharing satisfies

. We also develop the relationship between the supply chain members’ profits and

before and after improved RSB based on profit sharing where

in .

From and , the profits of the manufacturer and the retailer in models vary with the changes of . The ranking of the usefulness of models from the profits’ perspective of the manufacturer, the retailer respectively follows as below:

,

. Therefore, both two-part tariff contract and profit sharing contract help to attain improved RSB. When related parameters of the models meet the constraints, profits for the green supply chain members can be higher than by RS, and RSB finally achieves the Pareto improvement and continual stability of green supply chain in manufacturing industry. Clearly, the analysis shows that from the perspective of supply chain members’ profits, RSB will lower the retailer’s returns. By introducing two contracts, the purpose of improving RSB is realised, which not only raises the green level, but also increases the supply chain members’ profits. Meanwhile, the players will benefit from the improved RSB, but the degree of benefits is different. In practice, surplus profit distribution depends on the bargaining power of the two parties, namely, either of which is more irreplaceable in the market, which is also a question worth discussing in the future.

7. Conclusions

The paper analyses the green supply chain in manufacturing industry, which consists of a manufacturer and a retailer. The impacts of RSCs for undertaking green R&D costs on continual stability of green supply chain are discussed. The analysis results show that RSC realises the stable development of green supply chain; secondly, RSB makes the manufacturer gain more profits than RS, which can produce a higher green level than before. However, RSB will make the retailer’s profit lower than in the decentralised supply chain with no revenue sharing, so the retailer will not follow the contract unless other conditions are changed. In this dilemma, two-part tariff contract and profits sharing contract are introduced separately to improve RSB. When the retailer obtains a manufacturer’s prepaid expenses or a proportion of supply chain profit which meets the constraints, the green level, overall and individual profit in green supply chain are further improved, and the continual stability comes true in RSB.

Quantitative analysis results could be applied as valuable guidance for green supply chain management in manufacturing industry, and the following managerial insights can be put forward. Firstly, improving the degree of information sharing among supply chain members is important, and the manufacturer and retailer can establish an integrated supply chain management system through strategic cooperation. Secondly, the reduction of green cost through cooperative R&D is required. The manufacturer can not only reduce R&D costs by sharing revenue, but also has more benefit and less risk than the retailer. Meanwhile, cooperative R&D of green products enhances mutual trust, and also helps to reduce investment and promote the profits level of both sides. Thirdly, publicising green ecology and enhancing consumer environmental awareness are essential. Meanwhile, we strongly recommend that the governments strengthen the implementation of environmental regulations and promote the eco-labels for green products.

In this paper, the research of green supply chain coordination is based on the simple linear market demand in a deterministic setting. It only discusses a two-echelon green supply chain in manufacturing industry including one manufacturer and one retailer, and only production and R&D cost exist in the model. Future research can be extended to a stochastic environment, and the players of green supply chains include multiple manufacturers, multiple retailers and governments. In addition, with the improvement of government regulations on the green level of products, we can further explore the impact on the stability of green supply chains caused by the other costs (e.g. marketing cost, fixed cost, government penalty).

Authors’ contribution

Maozeng Xu conceived and designed the the Framework of the paper, Luqing Rong carried out experimental analysis and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for the anonymous reviewers’ valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Luqing Rong

Luqing Rong is a PhD candidate of Management Science and Engineering at Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China. His current research interests include green supply chain management and sustainability, supply chain system optimization.

Maozeng Xu

Maozeng Xu is a professor of Management Science and Engineering at Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China. He has published more than 10 papers indexed by EI, who also is a doctoral supervisor. His current research interests include green supply chain management and sustainability, supply chain system optimization. His E-mail is: [email protected].

References

- Abbey, J. D., M. G. Meloy, V. D. R. Guide Jr., and S. Atalay. 2015. “Remanufactured Products in Closed-Loop Supply Chains for Consumer Goods.” Production and Operations Management 24 (3): 488–503. doi:10.1111/poms.12238.

- Ahi, P., and C. Searcy. 2013. “A Comparative Literature Analysis of Definitions for Green and Sustainable Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Cleaner Production 52: 329–341. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.02.018.

- Azevedo, S. G., H. Carvalho, and V. Cruz Machado. 2011. “The Influence of Green Practices on Supply Chain Performance: A Case Study Approach.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 47 (6): 850–871. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2011.05.017.

- Banker, R. D., I. Khosla, and K. K. Sinha. 1998. “Quality and Competition.” Management Science 44 (9): 1179–1192. doi:10.1287/mnsc.44.9.1179.

- Bhaskaran, S. R., and V. Krishnan. 2009. “Effort, Revenue, and Cost Sharing Mechanisms for Collaborative New Product Development.” Management Science 55 (7): 1152–1169. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1090.1010.

- Bruntland, G. 1987. World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cachon, G. P. 2003. “Supply Chain Coordination with Contracts.” Handbooks in Operations Research & Management Science 11 (11): 227–339. doi:10.1016/S0927-0507(03)11006-7.

- Cachon, G. P., and M. A. Lariviere. 2005. “Supply Chain Coordination with Revenue-Sharing Contracts: Strengths and Limitations.” Management Science 51 (1): 30–44. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1040.0215.

- Carter, C. R., and P. Liane Easton. 2015. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Evolution and Future Directions.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 41 (1): 46–62. doi:10.1108/09600031111101420.

- Chakraborty, T., S. S. Chauhan, and M. Ouhimmou. 2019. “Cost-sharing Mechanism for Product Quality Improvement in a Supply Chain under Competition.” International Journal of Production Economics 208: 566–587. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.12.015.

- Choi, S. C. 1991. “Price Competition in a Channel Structure with a Common Retailer.” Marketing Science 10 (4): 271–296. doi:10.1287/mksc.10.4.271.

- Chung, C.-J., and H.-M. Wee. 2011. “Short Life-cycle Deteriorating Product Remanufacturing in a Green Supply Chain Inventory Control System.” International Journal of Production Economics 129 (1): 195–203. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.09.033.

- DESA, UN. 2016. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” https://stg-wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/11125/unep_swio_sm1_inf7_sdg.pdf?sequence=1

- Diabat, A., and K. Govindan. 2011. “An Analysis of the Drivers Affecting the Implementation of Green Supply Chain Management.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 55 (6): 659–667. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.12.002.

- Esfahbodi, A., Y. Zhang, and G. Watson. 2016. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Economies: Trade-offs between Environmental and Cost Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 181: 350–366. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.02.013.

- Fahimnia, B., J. Sarkis, and H. Davarzani. 2015. “Green Supply Chain Management: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis.” International Journal of Production Economics 162: 101–114. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.01.003.

- Ghosh, D., and J. Shah. 2012. “A Comparative Analysis of Greening Policies across Supply Chain Structures.” International Journal of Production Economics 135 (2): 568–583. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.05.027.

- Ghosh, D., and J. Shah. 2015. “Supply Chain Analysis under Green Sensitive Consumer Demand and Cost Sharing Contract.” International Journal of Production Economics 164: 319–329. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.11.005.

- Gimenez, C., V. Sierra, and J. Rodon. 2012. “Sustainable Operations: Their Impact on the Triple Bottom Line.” International Journal of Production Economics 140 (1): 149–159. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.01.035.

- Hong, Z., and X. Guo. 2019. “Green Product Supply Chain Contracts considering Environmental Responsibilities.” Omega 83: 155–166. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2018.02.010.

- Li, B., M. Zhu, Y. Jiang, and L. Zhenhong. 2016. “Pricing Policies of a Competitive Dual-channel Green Supply Chain.” Journal of Cleaner Production 112: 2029–2042. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.017.

- Li, T., R. Zhang, S. Zhao, and B. Liu. 2019. “Low Carbon Strategy Analysis under Revenue-sharing and Cost-sharing Contracts.” Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 1462–1477. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.282.

- Linton, J. D., R. Klassen, and V. Jayaraman. 2007. “Sustainable Supply Chains: An Introduction.” Journal of Operations Management 25 (6): 1075–1082. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2007.01.012.

- Liu, P. 2018. “Pricing and Coordination Strategies of Dual-channel Green Supply Chain considering Products Green Degree and Channel Environment Sustainability.” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 1–11. doi:10.1080/19397038.2018.1488891.

- Madani, S. R., and M. Rasti-Barzoki. 2017. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management with Pricing, Greening and Governmental Tariffs Determining Strategies: A Game-theoretic Approach.” Computers & Industrial Engineering 105: 287–298. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2017.01.017.

- Murali, K., M. K. Lim, and N. C. Petruzzi. 2019. “The Effects of Ecolabels and Environmental Regulation on Green Product Development.” Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 21 (3): 519–535. doi:10.1287/msom.2017.0703.

- Navinchandra, D. 1990. “Steps toward Environmentally Compatible Product and Process Design: A Case for Green Engineering (NO. CMU-RI-TR-90-34).” Carnegie Mellon Univ Pittsburgh Pa Robotics Inst. https://www.ri.cmu.edu/pub_files/pub3/navin_chandra_dundee_1990_1/navin_chandra_dundee_1990_1.pdf.

- Raj, A., I. Biswas, and S. K. Srivastava. 2018. “Designing Supply Contracts for the Sustainable Supply Chain Using Game Theory.” Journal of Cleaner Production 185: 275–284. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.046.

- Rao, P., and D. Holt. 2005. “Do Green Supply Chains Lead to Competitiveness and Economic Performance?” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 25 (9): 898–916. doi:10.1108/01443570510613956.

- Raza, S. A. 2018. “Supply Chain Coordination under a Revenue-sharing Contract with Corporate Social Responsibility and Partial Demand Information.” International Journal of Production Economics 205: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.08.023.

- Sarkis, J. 2001. “Manufacturing’s Role in Corporate Environmental sustainability-Concerns for the New Millennium.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 21 (5/6): 666–686. doi:10.1108/01443570110390390.

- Sarkis, J., Q. Zhu, and K.-H. Lai. 2011. “An Organizational Theoretic Review of Green Supply Chain Management Literature.” International Journal of Production Economics 130 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.11.010.

- Sheu, J.-B., and Y. J. Chen. 2012. “Impact of Government Financial Intervention on Competition among Green Supply Chains.” International Journal of Production Economics 138 (1): 201–213. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.03.024.

- Song, H., and X. Gao. 2018. “Green Supply Chain Game Model and Analysis under Revenue-sharing Contract.” Journal of Cleaner Production 170: 183–192. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.138.

- Tsay, A., S. Nahmias, and A. Narendra. 1999. “Modeling Supply Chain Contract: A Review. Quantitative Models for Supply Chain Management.” In R. and Magazine, edited by T. S. Ganeshian. M Kluwer Academic Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4949-9_10.

- UN, Economic and Social Council, and General Assembly. 2019. “Special Edition of the Sustainable Development Goals Progress Report (E/2019/68).” https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2019/secretary-general-sdg-report-2019–Statistical-Annex.pdf

- Veen, J. A. A. V. D., and V. Venugopal. 2005. “Using Revenue Sharing to Create Win–Win in the Video Rental Supply Chain.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 56 (7): 757–762. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601879.

- Wang, Q., D. Zhao, and H. Longfei. 2016. “Contracting Emission Reduction for Supply Chains considering Market Low-carbon Preference.” Journal of Cleaner Production 120: 72–84. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.049.

- Weraikat, D., M. K. Zanjani, and N. Lehoux. 2016. “Coordinating a Green Reverse Supply Chain in Pharmaceutical Sector by Negotiation.” Computers & Industrial Engineering 93: 67–77. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2015.12.026.

- Zhao, R., G. Neighbour, J. Han, M. McGuire, and P. Deutz. 2012. “Using Game Theory to Describe Strategy Selection for Environmental Risk and Carbon Emissions Reduction in the Green Supply Chain.” Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 25 (6): 927–936. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2012.05.004.

- Zhu, Q., J. Sarkis, and K.-H. Lai. 2012. “Green Supply Chain Management Innovation Diffusion and Its Relationship to Organizational Improvement: An Ecological Modernization Perspective.” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 29 (1): 168–185. doi:10.1016/j.jengtecman.2011.09.012.

- Zhu, W., and H. Yuanjie. 2017. “Green Product Design in Supply Chains under Competition.” European Journal of Operational Research 258 (1): 165–180. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2016.08.053.