?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Sustainability assessments provide methodologies to assess the environmental, economic, and social impacts of products along their life cycle. The purpose of this research is to develop a social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) framework derived from a set of challenges identified in the S-LCA field. The S-LCA framework presented in this study is developed by i) performing a systematic mapping of the S-LCA field; ii) gathering of LCA and SIA expert feedback; iii) evaluation through a novice user study; iv) and a case study application. The systematic mapping procedure is explained in detail (Bonilla-Alicea and Fu 2019), while the expert feedback and novice user study are the focus of this article. The case study application of the framework is the subject of a separate publication. The expert feedback is used to verify the relevance of the challenges through electronic survey data. Based on the expert feedback, the number of challenges is reduced from twelve to ten, as two of the challenges are considered part of the study design rather than challenges to performing social assessments. The novice user study implemented a simplified version of the S-LCA framework, and users were able to identify potential social impacts of their capstone design.

1. Introduction

1.1. Previous social assessment studies

Relative to environmental and economic assessments, social assessments lack consensus, a result of the lack of maturity of the field and the breadth of topics covered. The fact that there is no single social impact assessments (SIA) definition or methodology results from the lack of maturity of the field and from the broadness of fields in which SIAs are applied to. Due to the broad spectrum of topics covered in social assessments, it is important to define the following three social assessment methodologies: social impact assessments (SIA), social life cycle assessments (S-LCA) and social organisation life cycle assessments (SO-LCA). Numerous definitions of SIA are found in the literature: ‘it is a methodology to assess the social impacts of a single process and/or plant related to a product or service, and it is often used in the context of development projects’ (Benoît et al. Citation2010); ‘it refers to the process of defining, monitoring, and employing measures to demonstrate benefits created for the target beneficiaries and communities through social outcomes and impacts’ (Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015); ‘it is the process of identifying the social consequences or impacts that are likely to follow specific policy actions or project development, to assess the significance of these impacts and to identify measures that may help to avoid or minimize adverse effects’ (Benoit and Mazijn Citation2009). For the purpose of this article, the following definition of SIA is adopted: ‘a process of research, planning and the management of social change or consequences (positive and negative, intended and unintended) arising from policies, plans, developments and projects’ (United Nations Environmental Programme Citation2007). SIA is thus focused on evaluating the social impacts from policy implementation, projects and development programmesthat are beyond impacts resulting from natural resources (International Institute of Sustainable Development Citation2016). S-LCA evaluates the positive and negative social impacts of products from a product life cycle perspective by adopting the International Organization for Standardisation (ISO) 14044 assessment framework (Benoit and Mazijn Citation2009; International Organization for Standardization Citation2006). SO-LCA provides an extension to S-LCA by combining it with the Organizational Life Cycle Assessment (OLCA), which adapts the product LCA framework to an organisational perspective (Martínez-Blanco et al. Citation2015). Among these three methodologies, the framework presented in this paper focuses on S-LCA, and it proposes an approach to evaluating the social impacts of product systems using an LCA framework.

Plenty of articles have highlighted methodological issues and challenges in social assessment methods. The systematic mapping performed by Bonilla-Alicea and Katherine (Citation2019), showed that 88% of the reviewed articles adopted a social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) structure. The benefit is that it allows for easy integration of a social assessment with an environmental (E-LCA) or life cycle costing assessment (LCC), since it has the same structure. The disadvantage is that it carries the same challenges been faced by E-LCA, along with the challenges presented by social assessment themselves.

provides a summary of previous articles that discuss methodological issues with S-LCA. Sureau et al. (Citation2018), performed a literature review of existing S-LCA frameworks and evaluated the criteria used to select the impact criteria and metrics. Dubois-Iorgulescu et al. (Citation2018), reviewed methodologies to define the system boundaries in an S-LCA based on case studies. Their analysis highlights the high subjectivity in the case studies when defining the system boundaries, as the criteria are mostly qualitative. Tsalidis et al. (Tsalidis et al. Citation2021) highlight how expanding system boundaries by including companies that are subsidiaries of the parent company can result in a different social assessment result when performing an S-LCA analysis. Kühnen and Hahn (Citation2017a) studied issues related to the lack of a standardised set of indicators across industries. They performed a systematic review of indicators across industry sectors and found that ‘only a few sectors receive sufficient empirical attention to draw reasonable conclusions’. Petti, Serreli, and Cesare (Citation2018) identified methodological issues in S-LCA that are borrowed from the E-LCA structure. They identified the impact assessment as the most fragmented stage of the analysis since there is no consensus on a method to complete this step. As a result, several different methods have been developed based on the needs of the applications. The performance reference point (PRP) method attempts to quantify the social impact based on a reference value for each indicator (Chhipi-Shrestha, Kumar, and Sadiq Citation2015). Subramanian et. al (Subramanian and Yung Citation2018) provide a comprehensive summary of different PRP research applications with references. As stated by Shang et. al (Shang et al. Citation2018), ‘other methods rely on databases to perform the impact quantification based on categories determined from the scope of the study. Examples of such methods are the Social Hotspot Database (SHDB) (Norris, Aulisio, and Norris Citation2012) and the Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment (PSILCA) database (Ciroth and Eisfeldt Citation2015)’. The SHDB ‘was developed in accordance with the UNEP/SETAC guidelines and contains data of indicators numerous countries and economic sectors’ (Spierling et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. Summary of articles investigating S-LCA issues

A key aspect of S-LCA is the concept of stakeholder theory. Stakeholder theory is defined as ‘an instrument for evaluating the social harms and benefits resulting from company-stakeholder relationships during the life cycle’ (Kühnen Citation2017c). S-LCA evaluates such harms and benefits by means of indicators assigned to different stakeholder groups. A single definition of stakeholders in S-LCA is yet to be provided, as there doesn’t seem to be a consensus on their role in S-LCA (Mathe Citation2014). Mathe et al., highlight that ‘the role of stakeholders in LCA vary by project’ (Mathe Citation2014). They mention that ‘stakeholders may be considered in the following four ways: (1) as LCA method users, (2) as LCA results users, (3) as victims or beneficiaries of impacts, or (4) as actors in the definition of either the types of relevant impact or more generally the LCA methodology’. Based on the scope of this article and in the application of our framework, the definition of stakeholder applicable to this manuscript is definition (3), where stakeholders are seen as the recipients, and/or participants of any of the processes included within the system boundaries of the study. Although there is no consensus, the framework presented in this article adopts the stakeholder definition provided by stakeholder theory adapted to S-LCA (Benoît et al. Citation2010). A stakeholder is defined as ‘any individual or group of individuals who are affected or can affect the achievement of an organization’s objective’(Freeman Citation1984). In S-LCA, stakeholders are then individuals or group of individuals that are affected or that can affect the activities considered in scope of the life cycle.

Impact assessment methods are divided as Type I and Type II methods in the S-LCA literature. Type I impact assessment methods ‘define impacts based on ordinal scales, where results describe either the risk, the performance or the degree of management of the impacts’ (Benoît-Norris et al. Citation2011). Type II methods aim to ‘define social impact pathways by using characterization models that results in cause-effect relationships between indicators and their resulting social impacts’ (Benoît-Norris et al. Citation2011). This impact method aims at ‘establishing causal relationships between social activities that cause changes and effects resulting in impacts’ Kühnen and Hahn, (Citation2017a). Garrido et al. (Citation2018) performed an analysis of Type I methodologies, with a focus ‘on the inventory data used, the linking of inventory data to the functional unit, and the type of characterization and weighting methods being used’. Their analysis resulted in a proposed typology of characterisation and weighting methods. Zanchi et al. (Citation2018) performed a systematic review of case studies focused on the automotive sector. The focus of their review was analysing how the goal and scope of the analysis is defined. Their analysis resulted in the identification of the following key elements affecting such a definition: ‘perspective, S-LCA as a stand-alone method or within a Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment, selection and prioritization of indicators, definition of the functional unit and system boundaries, classification of background and foreground processes, data sources, data quality and geographic level of data’.

1.2. S-LCA framework

In addition to the previously mentioned articles, the systematic mapping performed by Bonilla-Alicea and Fu (Citation2019) highlighted a set twelve of recurring challenges mentioned by authors of references cited in their literature review process. This set of challenges is used as the initial step in developing the S-LCA framework presented in this article. The research question investigated in this article is the following: How can the user be guided through the S-LCA process to overcome the identified challenges? This article proposes an S-LCA framework to evaluate the potential social impacts of products along their life cycle. By adopting the LCA structure it has the following assessment stages: goal and scope, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation of results. The framework provides a mapping of challenges to each stage of the S-LCA along with recommendations for how to overcome them. Also, a classification scheme is provided for the analysis, adopted from the work of Kjaer et al. (Citation2018) on Product Service Systems (PSS). Analysis recommendations are provided for each analysis type. This framework aims at advancing the S-LCA field by guiding users through addressing the identified set of challenges and by providing databases of methodologies to overcome such challenges.

2. Methods

shows the steps in the development of the novel framework. Steps 1–3 are explained in more detail in the following sections. The work presented in this article involves steps 2 and 3 of the framework development process. Step 4, a case study application of the framework is outside the scope of this article and will be the subject of a separate publication.

Table 2. Steps for challenged-derived framework development process

2.1. Systematic mapping of social assessment field

The first part of the work presented in this paper involved a systematic mapping of the social assessment field Bonilla-Alicea and Katherine (Citation2019). Although most articles included in the systematic mapping adopted an S-LCA structure, the mapping included literature beyond S-LCA to identify potential benefits that could be incorporated in S-LCA from outside disciplines. The research question investigated in the systematic mapping was the following: What are the current methods available to perform social impact assessments, and how have these been implemented? An important clarification must be made to the reader before reviewing the systematic mapping paper. In that paper, there is not a clear distinction between the SIA and S-LCA methodologies and definitions for these two are not provided. The reader should understand that there is a clear distinction among the two methodologies, and it is recommended to adopt the definitions provided in the introduction section of this article. The systematic mapping reviewed 81 articles, of which 49 included a case study application, and nine were non-peer reviewed articles. The main outcome from the systematic mapping was the identification of twelve recurring challenges to performing social assessments. The challenges, along with related journal articles, are summarised in :

Table 3. Identified challenges to performing social assessments

2.2. Expert feedback study to evaluate the validity of challenges

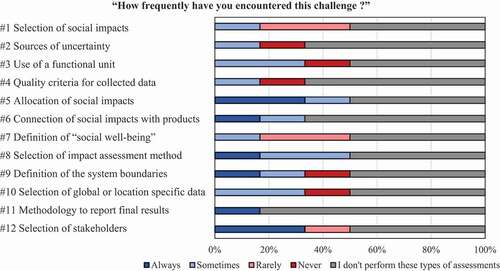

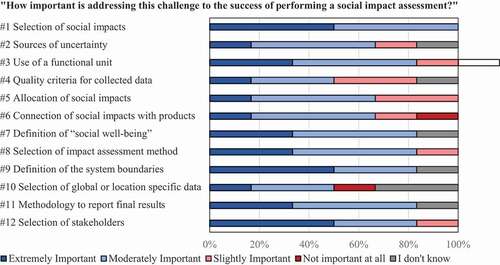

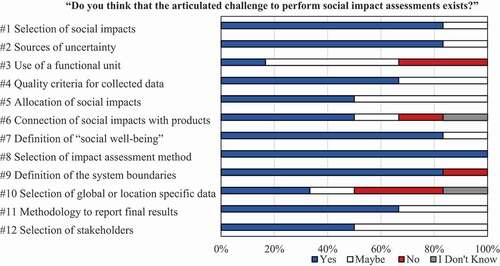

To evaluate the validity of the identified challenges, expert feedback was collected through online surveys. Six experts provided their feedback. The expert feedback questions combined Likert scale type questions and open response type questions (online resource 1). A Likert-scale type of questionnaire ‘is a psychometric scale that has multiple categories multiple categories from which respondents choose to indicate their opinions, attitudes, or feelings about a particular issue’(Beglar and Nemoto Citation2014). The researchers wanted to allow the experts to provide any feedback outside of the Likert questions, which is why open ended questions were included in the expert feedback surveys. The survey questions focused on evaluating the following criteria relevance or validity of the challenge, frequency of encountering the challenge, and importance of the challenge. For the relevance or validity criteria, the experts had the following answer options: yes, maybe, and no. For the frequency of encountering the challenge criteria, the experts had the following answer options: always, sometimes, rarely or I don’t perform these types of assessments. For importance of the challenge criteria, the experts had the following answer options: very important, moderately important, slightly important or I don’t know. A space for open feedback was also provided for each of the challenges. The experts consisted of active researchers in the areas of E-LCA, S-LCA and SIA. The list of experts contacted was created from the articles identified during the systematic mapping procedure, and these were contacted electronically via email. Although experts from North, Central and South America, the European Union, Africa, and Asia were contacted, responses were only received from individuals located in the United States and the European Union.

2.3. Novice user study

The novice user study involved undergraduate senior capstone students from the Georgia Institute of Technology, located in the city of Atlanta, GA. The students were provided with a 50-minute lecture on the topic of S-LCA, along with an example of an S-LCA of a laptop computer. As part of the lecture, the students were provided with a simplified version of the S-LCA framework (online resource 2) that didn’t include the impact assessment stage, which is part of the supplementary material provided with this article. The impact assessment stage was removed for the novice users because of the time and data resources available to the students during their capstone semester. For most of the students, the S-LCA lecture was the first time that they were introduced to the topic of social impacts, so performing a full S-LCA was deemed too overwhelming and time-intensive. Instead, the focus of the lecture and the exercise was to provide students with the knowledge to develop a complete plan to perform an S-LCA . The students were instructed to follow the framework and to use the United Nations Environmental Programme/Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (UNEP/SETAC) guidelines as a source of social impact categories and indicators for their analysis. Feedback data was collected electronically from the students regarding the usefulness of the framework to complete their analysis and to collect any other feedback they may have had. These activities were a part of the course that all students were expected to complete. Those students who chose to voluntarily participate in this IRB approved study gave consent to the research team to examine their course deliverables for the sake of this research effort.

Three reference documents were provided to the students, two of which are provided as supplementary material with this article: simplified capstone S-LCA framework (online resource 2), S-LCA results template (online resource 3), and the UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets for Sub-Categories in S-LCA (Benoît-Norris et al. Citation2011). The simplified framework consists of the following three assessment stages: goal and scope, inventory analysis and interpretation of results. As previously stated, the impact assessment stage was removed. The capstone students were also provided with guiding questions during the interpretation of results stage of the assessment.

The reports were assessed qualitatively based on the following eight criteria: evidence of social awareness, level of applicability to design project, accuracy, and completeness of framework implementation, increased mastery of appropriate terminology and vocabulary in S-LCA, ability to be critical of their projects for the sake of improving social impacts, goal and scope explanation, inventory analysis explanation and interpretation of results explanation. For each report, a qualitative score was given as either poor, acceptable, or excellent. A qualitative evaluation rubric (online resource 5) was used to evaluate the capstone student reports. An inter-rater agreement analysis was performed by evaluating the percentage agreement between two raters. Both raters were graduate level engineering researchers with expertise in qualitative and mixed methods research. The first rater coded all the data using the evaluation rubric (online resource 5). The second rater independently coded a randomly selected 25% of the data. Their agreement was checked by comparing the percentage of matching scores for the shared dataset. The goal of the inter-rater analysis was to evaluate the robustness of the qualitative assessment and ensure scientific repeatability. A high agreement between the two raters indicates that the qualitative assessment measurement is robust and can be trusted as unbiased by one individual rater’s judgement

3. Results

3.1. Expert feedback study results

provides a summary of the expert feedback results gathered electronically. The results for each Likert scale question are shown in (). Although the contact experts have combined backgrounds in LCA and SIA, most of them have a focus on applying the LCA framework. Each challenge was either provided support, mixed support, or no support from the experts, summarised in . Based on the expert feedback, the number of challenges was reduced from twelve to ten, by eliminating challenges number ten and number eleven. These two challenges were removed, as they are considered more of issues with the design of the assessment rather than challenges to performing it. The expert feedback results support the rest of the challenges, which validates them and are thus kept.

Table 4. Challenge classification based on expert feedback

Table 5. Summary of expert feedback regarding the challenges

Figure 1. Expert feedback results for question #1: ‘Do you think that the articulated challenge to perform social impact assessment exists?’

3.2. Novice user study results

The capstone report sections on S-LCA were assessed for seven capstone student groups. shows the number of reports that were given each of the rubric scores for each criterion. The criteria used for the qualitative evaluation aims to capture the ability of the student teams to apply the provided reference template and reference documents and to thoroughly explain the importance of each assessment stage of the S-LCA. By doing this qualitative assessment, it is expected to identify the areas in which the students excelled, but more importantly, the areas in which the framework should be improved. Overall, most of the teams received an acceptable or excellent score in most of the criteria, which is encouraging. Quotes extracted from the highest quality reports are provided for each of the criteria evaluated. Portions of the quote related to details of the design are removed to prevent identification of the capstone projects and subsequently of the capstone team participants in the study.

Table 6. Qualitative assessment results of capstone S-LCA reports

Regarding criteria #1, ‘evidence of social awareness’, the teams did an excellent job of mapping the possible potential impacts to each of the stakeholder groups and the product life cycle stages. Some reports showed evidence of external research data and references, in addition to the reference documents provided, which shows increased interest and commitment. The following quote is from a report that had an excellent rating in criteria #1: ‘Associated with the production cycle, it is important to evaluate the methods in which the workers are affected. Workers are impacted by health and safety concerns associated with the use of PET, both with the sanitation concerns associated with used bottles and the extraction of the recyclable materials themselves both of which should be regulated under FDA standards’. The students make an important point in highlighting an area of concern in the process, which could be the focus of efforts to minimise impacts on workers. The reports that did poorly in this section either didn’t make any social awareness comments at all, or if they did, the comments were not mapped to any of the product life cycle stages or the stakeholder groups.

Criteria #2, ‘level of applicability of the project’, showed excellent performance, which is expected as S-LCA are deemed to be universally applicable. Even though the simplified S-LCA framework applies to all the capstone design projects shown in the evaluated reports, it does not mean that it will be perceived to be applicable by all students in the course. The S-LCA framework is expected to apply to all projects, but because only seven reports were reviewed in this qualitative assessment section, such a statement is made. Still, it is encouraging to see that for all the reports analysed for these criteria, the S-LCA framework was seen as applicable by the student teams.

Criteria #3, ‘Accuracy and completeness of framework implementation’, shows more of an acceptable rather than excellent level of completion. The reports that had a score of excellent, provided all the information asked for in the guiding documents and provided explanations for that information. Reports that had an acceptable score used the templates and guiding documents provided to develop the reports, but they failed in the interpretation of results stage. For this stage, guiding questions were provided, and only one of the groups answered all the guiding questions. The reports that were given a score of poor either didn’t use the provided templates or just placed information in the templates without any supporting explanation.

Criteria #4, ‘Increased mastery of appropriate terminology and vocabulary in social impact assessment’, aimed at evaluating the use of S-LCA terminology in the explanation provided by the students. Most of the reports used terms such as product life cycle stages, stakeholder groups, social impact categories and social impact indicators in their explanations. The following is a quote from a report that used S-LCA terms extensively throughout their explanations: ‘After selecting applicable life cycle stages for the device, the Methodological Sheets for Sub-Categories in the Social Life Cycle Assessment were utilized to determine stakeholders involved in each stage … For each stakeholder, there are social impact categories that affect that specific stakeholder. Within those categories are impact indicators that measure positive and negative societal impacts’. Here the students referred to the methodological sheets, and they used the terms ‘stakeholders’, ‘impact categories’ and ‘impact indicators’. The reports that received a score of poor either didn’t use any of the terms or didn’t use the reference documents provided, which make extensive use of the terms. These reports were probably from groups that didn’t attend the S-LCA lecture explanation, but this is merely a speculation and must be investigated in more detail.

Criteria #5, ‘Ability to be candid and critical of their projects for the sake of improving social impacts’, aimed at assessing the ability of the students to foresee the potential social impacts of their designs in an honest way. This part of the S-LCA requires the students to research the far-reaching impacts of their designs. Most of the reports received a score of either acceptable or excellent because they completed the templates for the goal and scope, and the inventory analysis sections. These two sections require the students to select and justify the selection of the affected stakeholder groups and possible social impacts upon them. The following quote is from a report that highlights the potential impacts of the proposed product: ‘If the … supplying company exploits workers, uses child labor, or overworks their employees to meet the increased demand for …, then the effects will be negative … A negative societal impact is that the new system reduces the slowdown periods, which means that the system will feed more … overall, and thus more … will be produced. This will cause more waste when the … are thrown away at the end of the life cycle stage’. This group presents the possible negative social impacts resulting from the design and maps those potential impacts to stakeholder groups and life cycle stages. The groups that received a score of excellent in these criteria mapped the selected social impact categories and indicators to the respective stakeholder groups and product life cycles, while also justifying their selections. Reports that received a poor score either did not mention any possible social impacts resulting from their designs or mostly referred to environmental impacts.

Criteria #6, ‘Goal and scope explanation’, refers to the first S-LCA stage. Out of all the criteria evaluated, this one had the most polarised results, with no teams in the acceptable columns and all of them receiving either an excellent or poor score. In addition to using the provided template, those reports that received a score of excellent clearly defined the goal and scope of their analysis and justified the definition. The following are quotes from reports that did excellent in this criterion: ‘The … reduces paper waste and line slowdown periods, and the new system also brings changes to how the worker interacts with the line. The social impact assessment focuses on the effects of these changes’. This report clearly defines the goal and scope of the S-LCA being proposed. ‘The functional units being considered are the … and … of product. This is associated with the production, manufacturing, and end of life stages, shown in Table … ’ Here, the students clearly defined the functional unit of the analysis and defined the life cycle stages included in the analysis. These reports clearly defined the subsystems being analysed and used the goal and scope definition to guide the rest of the assessment. Those reports that received a score of poor either didn’t use the provided templates, or if used, no explanation or justification was provided for the information provided.

Criteria #7, ‘Inventory analysis explanation’, refers to the second S-LCA stage. Most of the reports received either a score of acceptable or excellent. These reports used the provided template and reference documents to present the social impact categories and indicators relevant to the analysis. The reports that were given a score of excellent, explained the social impact categories and indicators selected, and in some instances, provided sources for supplemental information for their analysis. The following quote from a student team report clearly defines the stakeholder groups considered in the analysis and the processes that guide the selection of the impact indicators: ‘Stakeholders being considered in this assessment are workers, society, the local community, and value-chain actors … . Impact indicators include examining existing protocols, looking at the number of injuries over some time, and analyzing Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) violations that occur that have not yet caused injuries, but could in the future. Value-chain actors are assessed to determine the effects of outsourcing labor, and indicators involve methods to ensure that … outsources their labor from reputable companies, shown in Table … The local community is assessed to determine how … (the) new process will affect local employment, with indicators analyzing how their employment demographics change over time’. The reports that were given a score of poor either did not use the provided templates to organise the information requested in this section, or if the information was provided, no explanation or justification was provided.

Criteria #8 ‘Interpretation of results explanation’, corresponds to the final stage of the S-LCA. This section was the most challenging for the students, as only one team earned a score of excellent, and most scores were acceptable and poor. In the template, the students were given guiding questions to aid in this section of the report. At a minimum, the students were expected to answer all the questions listed. The teas that were given a score of excellent highlighted the potential impacts of the use of their product and the affected stakeholder groups. The following quote is from the team that received an excellent score in this criterion: ‘For the consumers, the disassembly and disposal process present the possibility for injury through mishandling, and potentially breaking parts of the product. This concern will be addressed with comprehensive disassembly instructions and the product will be designed so that as few steps as possible will be needed to disassemble the product’. In the report, the students highlight the potential impacts of the use of their product and the affected stakeholder groups. They also propose solutions to minimise the mentioned health and safety social impacts in future design iterations. In those reports that were given a score of acceptable, the students did answer some of the guiding questions, but they failed to address in detail what future changes should be made to the design of the product to reduce future harmful social impacts. The reports that were given a score of poor either didn’t complete this section or did not address the guiding questions in their analysis.

For those student teams that followed the guidance provided in the reference documents, the S-LCA results provided the expected information about the potential impacts of the proposed designs, about the relevant product life cycle stages and stakeholder groups, and about what future design changes could reduce such impacts. Although several groups did not use the provided templates to organise the information, this may be due to a communication issue rather than an issue with the framework itself. Attending capstone lectures is not required for students, and as the semester gets more difficult, student attendance to capstone lectures tends to vary more significantly. As such, some of the students did not attend the S-LCA lecture. Another important aspect to consider is the variation in the capstone instructors’ perceptions of the importance of the social impact section of the final report. Although most instructors supported and valued S-LCA as part of the capstone course, some instructors did not promote this procedure in their capstone section, which might explain why some reports did not complete the section at all. Still, the feedback from the qualitative assessment helped identify changes that should be made to the simplified version of the S-LCA framework, which are discussed in Section 4 of this paper.

As described in Section 2.3, an inter-rater agreement analysis was conducted to verify the robustness of the qualitative assessment criteria for the capstone reports. The results show an overall agreement of 76% among the two raters, which is considered moderate to strong agreement.

3.3. S-LCA framework and implementation

After incorporating the expert feedback study results and novice user study results and feedback, the resultant S-LCA framework is presented in . As previously stated, the framework follows an LCA structure, and it is based on stakeholder theory.

Table 7. S-LCA Framework

For the goal and scope stage, the framework proposes the classification of the analysis as either informative, comparative, or enhancement. This classification is adopted from the work of Kjaer et al. (Citation2018) on evaluating the environmental impact of product service systems (PSS). The informative analysis is used when the analysis aims at understanding the potential social impacts of a single product system. In a comparative assessment, either various concepts of the same product are being compared or different products with similar functionality are being compared. In an enhancement analysis, numerous iterations of the same product are compared, where each of the changes aims at improving the social impacts of the product. The framework also divides the analysis between company conduct and assessing a product or a technology. The two analyses can be combined depending on the scope of the analysis, but this separation ensures that indicators used for each are not combined.

In the inventory analysis stage, a semi-quantitative data quality assessment method is provided. Also, the classification of indicators depends on ‘the goal and scope of the analysis, and the intended application’ (Ren and Toniolo Citation2020). If the analysis aims at comparing the social impacts at a product life cycle stage level or at a stakeholder group level, the indicators should be identified as such to allow this.

In the impact assessment stage, the direction of improvement of each indicator is needed to determine the quantification equation used. This is important, as the numerical scale of the results is based on positive social impacts, meaning that the higher the number, the better the social impact. In the interpretation of the results stage, this framework recommends an individual assessment of each indicator along with a narrative description. No numerical aggregation is recommended for informative type of studies unless it is necessary for the goal and scope of the analysis. Numerical aggregation is only recommended for comparative and enhancement analysis to facilitate the comparison of different concepts and or products with similar functionality. It should be noted that the application of this S-LCA framework to a case study is reserved for a separate, forthcoming publication.

provides a mapping of how the identified challenges map each stage of the analysis. The framework thus provides guidance at each stage of the assessment on how to overcome each of these challenges when doing the analysis. The provided guidance takes into consideration aspects about the study design, as these are factors that implicitly affect some of the challenges. For example, if a comparative type of analysis is performed, the recommendations provided on how to report the results is different than when an informative type of study is performed.

Table 8. Mapping of challenges to S-LCA stages

3.4. How is the framework implemented?

3.4.1. Goal and scope stage

The objective of the goal and scope stage is to define why the study is being performed and what is included in the analysis. The decisions made at this stage of the analysis are important because they have a profound effect on the rest of the analysis. shows a template to summarise the information for the goal and scope stage of the analysis. The summary should define the reason for performing the study and a definition of the system boundaries. Also, the type of analysis being performed is defined (informative, comparative or enhancement), as this has major implications on the steps to follow for subsequent stages of the analysis.

Table 9. Goal and scope information

3.4.2. Inventory analysis

The objective of the inventory analysis is to define the data that is used to perform the social impact assessment by means of the selection of the indicators used in the analysis. The selection of indicators in an S-LCA is seen as a major source of uncertainty by experts. Even though there are many quantitative and semi-quantitative methodologies to establish agreement among the selection of the indicators used in the analysis, there are many factors that affect the final list of indicators. First, the selection of relevant indicators must match the goal and scope of the analysis. Second, there isn’t a universal list of indicators to choose from when performing an S-LCA. Although the lack of a universal set of indicators is also criticised, the breadth of applications of S-LCA makes it difficult to have a single set of indicators that would cover any situation. As part of the systematic mapping procedure (Bonilla-Alicea and Katherine Citation2019), a database of indicators was created and organised (online resource 4). This indicator set is used as the starting point of the inventory analysis step.

The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) provides a structure for companies and organisation to publicly report how their activities contribute towards sustainable development. The GRI standards thus ‘create a common language for organizations and stakeholders, with which the economic, environmental and social impacts of organizations can be communicated and understood’ (GSSB 2020). Although the authors recognise the value of the list of indicators provided by the GRI, they want to extend this list based on the findings from the systematic mapping procedure. Different from the GRI, the indicator set provided with the framework (online resource 4) is structured based on the S-LCA presented in the UNEP guidelines (Benoit and Mazijn Citation2009) by providing each indicator with an impact category, a stakeholder group and an indicator type (quantitative, semi-quantitative or qualitative). By collecting information from a multitude of sources in addition to recognised organisations and standards, the indicator list provided by the framework (online resource 4) aims to provide indicators that are applicable at smaller resolution levels relative to international and global standards. It might be useful for the user to combine the indicator list provided in the framework with those listed in the GRI based on the goal and scope definition of the project.

The steps described below are followed to select the list of indicators for this analysis:

Refer to the indicator database provided with the framework (online resource 1)

Select relevant indicators based on the goal and scope of the case study

For each indicator, identify the following:

Indicator name

Indicator type: quantitative, semi-quantitative or qualitative

Desired direction or direction of positive social impact: positive or negative

Data collection method for indicator: primary (directly from source) or secondary (from indirect sources)

Scale of indicator: State, region, industry sector or company

Social impact category as per the Guidelines of Social Assessment of Products from United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) (Benoît et al. Citation2010)

If a new social impact category is desired, provide enough detail for the reader to understand why it is necessary

Stakeholder group(s) as per the Guidelines of Social Assessment of Products from United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) (Benoît et al. Citation2010)

If a new stakeholder group category is desired, please provide enough detail for the reader to understand why it is necessary

Source of indicator

Perform indicator data quality assessment using the modified matrix method provided in the framework

Update list of indicators based on the results of the data quality assessment

(Optional) Benchmark list of indicators using stakeholder input

When there is access to the stakeholders and when performing a high-detail analysis, use stakeholder input data to validate the list of indicators used in the analysis

Define the performance reference points (PRPs) used for the quantitative indicators

The next step is to assess the quality of the data for each indicator using the provided matrix assessment method (online resource 6). The method is based on the data quality assessment presented in the 2018 Handbook for the Social Impact Assessment of Products (Fontes et al. Citation2018) and the Pedigree matrix method (Weidema and Wesnæs Citation1996). Each column represents the criteria used in the assessment. Each row provides the criteria needed to assign the data quality score. The scores range from 1 (best) to 5 (worst). The assessment is based on the following four criteria: (1) accuracy, integrity, and validity, (2) timeliness or temporal correlation, (3) geographical correlation, and (4) technological correlation. Accuracy, integrity and validity relates to the sources of the data, the acquisition methods used to gather the data, and the verification procedures used to collect the data (Weidema and Wesnæs Citation1996; Fontes et al. Citation2018). Timeliness or temporal correlation refers to the time correlation between the time of the study and the time of collection of the data (Weidema and Wesnæs Citation1996). Geographical correlation refers to the correlation between the area under study and the area of the collected data (Weidema and Wesnæs Citation1996; Fontes et al. Citation2018). Technological correlation refers to aspects of the enterprises, industries, and/or characteristics between the technology or product under study and the collected data (Weidema and Wesnæs Citation1996; Fontes et al. Citation2018). As stated by Weidema and Wesnæs (Citation1996), it is important to see how each of the data quality indicators is assessing an independent aspect of data quality. In addition to assessing the data quality of the collected data, the results of the data quality matrix method should highlight the possibilities of improving the quality of the data being collected by evaluating the results for each of the data quality indicators. The resulting average score value must be less than 3 to pass the quality assessment test.

3.4.3. Impact assessment

The objective of the impact assessment stage is to provide meaning to the list of indicators created in the inventory analysis section. The first step is to define performance reference points (PRP) for the quantitative indicators. PRPs are threshold values used to provide meaning to the quantitative data. They provide a reference from which to quantify the impact of the quantitative indicators. The impact assessment consists of qualitative, semi-quantitative and quantitative indicators. All values are normalised to a scale between 0–1, where 0 represents the lowest social performance and 1 represents the best social performance. Because the final indicator values are assumed to represent positive social performance, the normalisation procedure for indicators with different directions of improvement are different. For quantitative indicators, the range between the minimum and maximum reference values are used to normalise the quantitative indicator:

There are two types of semi-quantitative indicators used in the framework, yes or no questions and a Likert scale with values between 1 and 5. To quantify yes and no questions, a yes is equal to a value of 1, and a no is equal to a value of 0. For Likert type questions, the normalisation depends on the direction of improvement of an indicator. For an indicator where the desired direction of improvement is positive (5 represents the best social performance and 1 represents the worst social performance), the normalisation procedure is the following:

For an indicator where the desired direction of improvement is negative (1 represents the best social performance and 5 represents the worst social performance), the normalisation procedure is the following:

As with semi-quantitative and quantitative indicators, the results are normalised between 0 (worst social performance) and 1 (best social performance). shows the recommended quantification procedure adopted from the Product Social Impact Assessment (PSIA) framework (Goedkoop et al. Citation2020). The quantification is based on the performance of the qualitative indicator relative to the PRP.

Table 10. Quantification of qualitative indicators

3.4.4. Interpretation of results

The objective of the interpretation of results stage is to identify the greatest contributors to social impacts and to propose changes to improve such impacts based on the results from the impact assessment stage. This stage consists of summarising the main learnings from the analysis. The strategy used in summarising and communicating the results should align with the desired question to be answered by performing the study. In other words, the interpretation of results should align with the goal and scope definition of the analysis. The use of aggregation is not recommended to establish conclusions about the potential social impacts of the analysis, but rather as a strategy to facilitate comparison. The recommended strategy is to interpret each indicator individually; in addition to providing a numerical result, a narrative of the results obtained in the analysis should be provided. The aim of recommending a narrative is to provide a complete interpretation of the results to the reader, an interpretation that may not be clear from a single number.

The use of aggregation should also follow the type of analysis being performed. When performing an informative study, no aggregation is recommended as the goal of the analysis is to understand the potential impacts of a single product system. When performing a comparative or enhancement type of study, the goal is to compare the social impacts among different alternatives. In this type of study, aggregation is only recommended to facilitate the comparison among different alternatives rather than to draw conclusions about social impacts. Aggregation may also facilitate comparison among different stakeholder groups or among different product life cycle stages, which again is only recommended to facilitate comparisons. Regardless of the aggregation strategy implemented, the aim is to select a strategy that aligns with the goal and scope of the analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Expert feedback study

Gathering expert feedback is beneficial in the development of a support tool, such as the S-LCA framework presented in this paper. Because of the breadth of applications covered by S-LCAs, having feedback from experienced practitioners adds validity to the findings of the systematic mapping procedure. Out of the twelve challenges identified, seven were supported by the experts, four were supported but to a lesser degree, and one was not recognised as a challenge. These findings resulted in a reduction of the list of challenges from twelve to ten by the removal of Challenges #10 and #11. Challenge #10, ‘selection of global or location-specific data’, was removed because it was considered a decision about the study design, rather than a challenge to performing S-LCA. Rather than being a limitation to performing the S-LCA, the decision to use either type of data depends on goal and scope of the analysis and the characteristics of the system being analysed. For example, let us assume that an assessment of a global product system is performed. In such a case, the decision on whether to use global or location specific data may lean more towards using global data as a reference if the scope of the analysis is to assess impacts at a global scale. If the scope of the analysis is to assess impacts at the local level even though it is a global product system, then the study might provide more insight if location specific data is being used. A different scenario would be that there is only one option for the researcher. For example, if one is attempting to understand the impacts for a system where there is no reliable data available at a global scale, such as in the SHDB, only location specific data can be used. Challenge #11, ‘selection of scoring scales for reporting the results’, was also removed because it is considered more a part of the interpretation and communication of the results, rather than a challenge to performing S-LCA. These results highlight the validity of the challenges identified during the systematic mapping procedure. The rest of the challenges were kept based on expert feedback data. Expert feedback has higher credibility relative to novice user feedback. This feedback aims to improve the usability of the S-LCA framework in professional practice by identifying conceptual problems that require a higher level of experience and knowledge. Experts understand from experience the full context of S-LCA and LCA, so their feedback is better reflective of the S-LCA framework user needs with regards to the challenges to performing S-LCA than novice users that have never perform an S-LCA. The novice user study highlighted areas in which the simplified S-LCA framework should be enhanced.

One of the limitations of the expert survey feedback is the low number of participants. Despite the lower than desired number of experts providing feedback, electronic surveys allow researchers to contact experts globally. Nonetheless, six participants are a significant sample size for experts, as they are notoriously difficult to access, and sample sizes in studies of experts across the literature are often in the single digits. An additional limitation of the expert feedback is that, even though all of them were familiar with Life Cycle Assessments, not all of them had experience performing social impact assessments. Although there are inherent similarities between social impact assessments and life cycle assessments, it would be of benefit if all experts providing feedback had first-hand experience performing S-LCAs. Given the two limitations of the expert feedback study, it is recommended to perform such a task in a setting where the experts are present, such as a workshop or a conference on the topic of S-LCA and have them provide the feedback in person.

4.2. Novice user study

One goal of the S-LCA framework developed in this paper is for it to be useful for both novice and expert users. The novice user feedback collected in this research aims at complementing the expert feedback gathered and shown in this paper. The novice user study highlighted areas in which the framework should be enhanced to make it more useful in a classroom setting. The qualitative assessment revealed that the most challenging part of the S-LCA is the interpretation of results stage. More specifically, the results showed that students struggled the most with design recommendations to reduce social impacts in future design iterations. Although guiding questions and an example was provided in the S-LCA template, additional lecture time and a more detailed example might help students with this task. Future versions of the framework will provide students with additional guidance in this section, with a focus on how to determine potential changes to the product design that would reduce the negative social impacts of future design iterations. Another observation is that all the groups performed the S-LCA on the final design iteration. For future S-LCA capstone lectures, the students would be advised to consider social criteria at earlier design stages, and they should be provided with an even simpler version of the framework for such purposes. Also, the qualitative assessment revealed the differences between student performance that followed and those that did not follow the guiding templates. The quality of the report of the students that followed the provided instructions was far superior to those that did not use the reference documents provided. The learnings from the novice user study will be incorporated into the guiding templates and documents provided to future students. The goal is to provide future engineers with a basic understanding of social impacts and the tools available to systematically assess the social impacts of design decisions. The interrater agreement analysis resulted in an overall agreement of 76%. This value shows that even though it is useful, additional research may be pursued to improve the qualitative rubric used in the assessment to make it even more robust. Additional input may be requested from experts on how to modify the rubric to improve it.

The novice user study had limitations. One limitation is the low participation rate of the students. Participation of teams of students is difficult to achieve because the entire team must provide consent to use the team data. There were many teams for which only a portion of the members provided consent, so their data couldn’t be used. Because of such a low number of participants, no generalisations or statistical analyses of the results can be made for the rest of the senior capstone student population. An additional limitation is that there is no record of the number of students that didn’t attend the S-LCA lecture. This may be important when performing the qualitative assessment of the reports because it may be that the students that did better on the report are those that attended the S-LCA lecture. It may be that the reference materials were not enough for the students to know in detail what is expected from them in the S-LCA report section. Also, there was one team in the study that didn’t complete an S-LCA section at all. This might reveal some miscommunication issues regarding the requirements of the capstone report.

4.3. What makes the framework novel?

There are two aspects that make the S-LCA framework presented in this paper novel. The first aspect is that it is the first framework that uses a set of identified S-LCA challenges as its starting point. The S-LCA framework maps the individual challenges to each of the S-LCA assessment stages (goal and scope, inventory analysis, impact assessment and interpretation of results) and then maps each of these challenges to methods for how to overcome them. shows how each of the identified challenges maps to each assessment stage. This mapping from assessment stage to method is expected to provide a more holistic approach to addressing S-LCA challenges, rather than the status quo approach of current studies, in which a solution method is presented for individual or a smaller subset of the challenges. By adopting this approach, the aim is to contribute to the development of a standard framework that is applicable to most problems, rather than providing a solution to a single challenge. For each of the challenges, the user is presented with a database of methods to overcome it (online resource 4). The user is referred to (Bonilla-Alicea and Katherine Citation2019), where a database of S-LCA articles are provided and could serve as an organised reference of previous studies. General recommendations, advantages and disadvantages of the different methods are provided to the user to help them make an educated decision about which method to use and why. By combining the identified challenges, how they relate to each S-LCA assessment stage, the methods and databases, the framework attempts to serve as a central source of information; time and effort will be saved for the user as all the needed information is found on a single document. Still, it is advised that the challenges, methods, and databases provided are limited to the findings of the systematic mapping procedure, and that their potential exists additional valuable information outside of the scope of the completed literature review.

The second aspect that makes the framework novel has to do with the goal and scope assessment stage of the analysis. An analysis classification scheme adapted from the work of Kjaer et al. (Citation2018) on product service systems, classifies the analysis into one of the following three types: informative, comparative or enhancement. Current S-LCA studies don’t explicitly make such a distinction, and it is recommended because the type of analysis being performed is linked to recommendations in the inventory analysis and impact assessment stages. For an informative type of study, the impact assessment results for quantitative indicators should be presented individually without any averaging. For comparative or enhancement studies, it is recommended to use a common indicator database for all products being analysed. It is only for the comparative or enhancement types of analysis that aggregation is recommended, and it should only be used to compare the S-LCA results of the different products or concepts being examined.

4.4. Limitations of the framework

As with any metric based framework, the main limitation of this framework is the risk of misinterpreting the social impacts for each of the stakeholders considered in the analysis. The goal of this framework is to support decision-making for experts, experts that are evaluating the social impacts of the system being analysed, based on their own interpretation. In S-LCA, local context becomes extremely important, meaning that a set of identified social impacts in a region or a group of individuals may be seen in a totally different manner by a different group of individuals. When performing the analysis, one must respect the opinions and input from the stakeholders, as they are the ones being affected by the system being studied. As an expert, one must redefine the term expert, in the sense that the stakeholders are the experts themselves, about what affects them and how. Therefore, it is recommended that the list of indicators is verified by using stakeholder input. There are some instances in which such an exercise may not be possible, either because of a lack of resources or because there is no way to reach the stakeholders and ask for their input. As with any stakeholder analysis, the individual or group of individuals performing the analysis must respect the stakeholder opinion and must avoid at all costs defining what is best for the stakeholder based only on a technical expertise.

5. Conclusions

A challenged-derived S-LCA framework is presented in this article. Relative to current S-LCA methodologies, the proposed framework either improves upon, expands, or follows a different approach relative to what is currently being done in the S-LCA field. Regarding the goal and scope assessment stage, the framework provides an improvement based on the definition of the level of detail of the study. Different levels of detail will have different data quality assessment requirements and different data source requirements. For low-detail studies, only secondary data-sources may be used. For high detailed studies, primary data is required. Also, data quality requirements are more stringent for highly detailed studies. The overall strategy recommended in this framework is to use a two-step approach. The first step is to perform a low-detail study that incorporates as much information as possible within its boundaries. The results from such an analysis are then used to perform a more focused, higher detail analysis that relies on primary data. Regarding the inventory analysis stage, an improvement is made by forcing the user to define the aggregation procedure before creating the indicator database. This is needed so that the indicators are defined in a way that it allows for the desired level of aggregation. For example, indicators to be aggregated at the stakeholder group must be defined per stakeholder group or product life cycle stage; otherwise, the desired aggregation is not possible. For the interpretation of results stage, the results for the indicators must be a combined numerical and qualitative assessment to reduce misinterpretation. The qualitative assessment should be in the form of a narrative and should complement the numerical indicator value.

The work presented in this study has inspired ideas for future research directions expected to advance both the framework presented in this paper and the social assessment field. One planned research direction is to further develop the framework so that it can be applied during the complete development process of a product. The goal would be to incorporate portions of the S-LCA framework into the engineering design process and describe how it could be applied at the different stages of the design process. This could result in a proactive approach to minimise the negative social impacts of a product, rather than relying on reactive measures. Future research should also pursue collaboration among engineers and social science experts. To provide a more holistic approach, collaboration efforts between technical and social sciences should aim to educate practitioners on the dangers of over quantification and on the development of methods that will help more technical practitioners avoid losing customer needs information due to the use of purely quantitative approaches. Overall, future research should focus on the development of social impact assessment methods and on educating future professionals in how to use them. Social criteria should be as important as economic and environmental criteria. Social impacts are tied to technical decisions, and future professionals need to have access to tools and methods to better understand such relationships.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (434.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (58.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (94.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to the experts and the capstone students that completed the electronic surveys and provided their feedback. In addition, the authors want to thank undergraduate researcher Nisha Detchprohm for her dedication and assistance with the novice user study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ricardo J. Bonilla-Alicea

Ricardo J. Bonilla-Alicea, Senior Engineer at 787Engineering, Augusta, GA, USA

Katherine Fu

Katherine Fu, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA

References

- Anaya, F. C., and M. M. Espírito-Santo. 2018. “Protected Areas and Territorial Exclusion of Traditional Communities: Analyzing the Social Impacts of Environmental Compensation Strategies in Brazil.” Ecol Soc 23(1). art8. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09850-230108.

- Arcese, G., M. C. Lucchetti, I. Massa, and C. Valente. 2018. “State of the Art in S-LCA: Integrating Literature Review and Automatic Text Analysis.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23: 394–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1082-0.

- Arvidsson, R., J. Hildenbrand, H. Baumann, K. M. Nazmul Islam, and R. Parsmo. 2018. “A Method for Human Health Impact Assessment in Social LCA: Lessons from Three Case Studies. Int.” J Life Cycle Assess 23 (3): 690–699. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1116-7.

- Beglar, D., and T. Nemoto. 2014. “Developing Likert-Scale Questionnaires.” JALT2013 Conf. Proc. 2013 Japan, 1–8.

- Benoît-Norris, C., G. Vickery-Niederman, S. Valdivia, J. Franze, M. Traverso, A. Ciroth, and B. Mazijn. 2011. “Introducing the UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets for Subcategories of Social LCA.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 16 (7): 682–690. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-011-0301-y.

- Benoit, C., and B. Mazijn. 2009. “Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products, 5 April 2018.” https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/2009-GuidelinesforsLCA-EN.pdf

- Benoît, C., G. A. Norris, S. Valdivia, A. Ciroth, A. Moberg, U. Bos, S. Prakash, C. Ugaya, and T. Beck. 2010. “The Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products: Just in Time!” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 15 (2): 156–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-009-0147-8.

- Bianchi, A., and E. Ginelli. 2018. “The Social Dimension in Energy Landscapes. City, Territ.” Archit 5 (1): 9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-018-0085-5.

- Bonilla-Alicea, R. J., and F. Katherine. 2019. “Systematic Map of the Social Impact Assessment Field.” Sustainability 11 (15): 4106. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154106.

- Chhipi-Shrestha, G., K. H. Kumar, and R. Sadiq. 2015. ““Socializing” Sustainability: A Critical Review on Current Development Status of Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method.” Clean Technol Environ Policy 17 (3): 579–596. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-014-0841-5.

- Ciroth, A., and F. Eisfeldt. 2015. “PSILCA – A Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment Database (Documentation).” Database Version 1 (December): 1–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b108584k.

- Corona, B., K. P. Bozhilova-Kisheva, S. I. Olsen, and G. S. Miguel. 2017. “Social Life Cycle Assessment of A Concentrated Solar Power Plant in Spain: A Methodological Proposal.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (6): 1566–1577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12541.

- Dubois-Iorgulescu, A., M. Anna Karin Elisabeth Bernstad Saraiva, R. Valle, and L. M. Rodrigues. 2018. “How to Define the System in Social Life Cycle Assessments? A Critical Review of the State of the Art and Identification of Needed Developments.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 507–518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1181-y.

- Dunmade, I., M. Udo, T. Akintayo, S. Oyedepo, and I. P. Okokpujie. 2018. “Lifecycle Impact Assessment of an Engineering Project Management Process - A SLCA Approach.” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng, July 9-13, 2018, 413, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/413/1/012061

- Ekener, E., J. Hansson, and M. Gustavsson. 2018. “Addressing Positive Impacts in Social LCA—Discussing Current and New Approaches Exemplified by the Case of Vehicle Fuels.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 556–568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1058-0.

- Eren, Y., G. Alev, and M. Arif. 2019. “Resources, Conservation & Recycling Environmental and Social Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Di Ff Erent Packaging.” Waste Collection Systems 143 (December 2018): 119–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.12.028.

- Fedorova, E., and P. Eva. 2019. “Cumulative Social Effect Assessment Framework to Evaluate the Accumulation of Social Sustainability Benefits of Regional Bioenergy Value Chains.” Renew Energy 131: 1073–1088. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.07.070.

- Fontes, J., P. Tarne, M. Traverso, and P. Bernstein. 2018. “Product Social Impact Assessment.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 547–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1125-6.

- Fortier, M.-O. P., L. Teron, T. G. Reames, D. T. Munardy, and B. M. Sullivan. 2019. “Introduction to Evaluating Energy Justice across the Life Cycle: A Social Life Cycle Assessment Approach.” Applied Energy 236 (October 2018): 211–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.11.022.

- Freeman, R. E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston, MA: Cambridge University Press. (Vol. 292: 0521151740).

- Garrido, R., J. P. Sara, L. Beaulieu, and J. P. Revéret. 2018. “A Literature Review of Type I SLCA—Making the Logic Underlying Methodological Choices Explicit.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 432–444. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1067-z.

- Gaviglio, A., M. Bertocchi, M. E. Marescotti, E. Demartini, and A. Pirani. 2016. “The Social Pillar of Sustainability: A Quantitative Approach at the Farm Level.” Agric Food Econ 4 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-016-0059-4.

- Goedkoop, M. J., I. M. De Beer, R. Harmens, D. Peter Saling, A. Morris, and F. A. Hettinger. 2020. “Product Social Impact Assessment Handbook. Accessed8 July 2020.” https://product-social-impact-assessment.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/20-01-Handbook2020.pdf

- Gregori, F., A. Papetti, M. Pandolfi, M. Peruzzini, and M. Germani. 2017. “Digital Manufacturing Systems: A Framework to Improve Social Sustainability of A Production Site.” Procedia CIRP 63: 436–442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2017.03.113.

- >Grubert, E. 2018. “Rigor in Social Life Cycle Assessment: Improving the Scientific Grounding of SLCA.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 481–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1117-6.

- Holger, S., K. Jan, Z. Petra, S. Andrea, and J.-F. Hake. 2017. “The Social Footprint of Hydrogen Production - A Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) of Alkaline Water Electrolysis.” Energy Procedia 105: 3038–3044. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.626.

- Hossain, M. U., C. S. Poon, Y. H. Dong, M. C. L. Irene, and J. C. P. Cheng. 2018. “Development of Social Sustainability Assessment Method and a Comparative Case Study on Assessing Recycled Construction Materials.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (8): 1654–1674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-017-1373-0.

- International Organization for Standardization. 2006. Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Requirements and Guidelines ISO 14040Geneva.

- James, K. L., N. P. Randall, and N. R. Haddaway. 2016. “A Methodology for Systematic Mapping in Environmental Sciences.” Environ Evid 5 (1): 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-016-0059-6.

- Janker, J., S. Mann, and S. Rist. 2019. “Social Sustainability in Agriculture – A System-Based Framework.” Journal of Rural Studies 65 (December 2018): 32–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.010.

- Kjaer, L. L., A. Pagoropoulos, J. H. Schmidt, and T. C. McAloone. 2016. “Challenges When Evaluating Product/Service-Systems through Life Cycle Assessment.” Journal of Cleaner Production 120: 95–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.048.

- >Kjaer, L. L., D. C. A. Pigosso, T. C. McAloone, and M. Birkved. 2018. “Guidelines for Evaluating the Environmental Performance of Product/Service-Systems through Life Cycle Assessment.” Journal of Cleaner Production 190: 666–678. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.108.

- Kühnen, M., and R. Hahn. 2017a. “Indicators in Social Life Cycle Assessment: A Review of Frameworks, Theories, and Empirical Experience.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (6): 1547–1565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12663.

- Kühnen, M. 2017b. “Indicators in Social Life Cycle Assessment: A Review of Frameworks, Theories, and Empirical Experience.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (6): 1547–1565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12663.

- Kühnen, M. 2017c. “Indicators in Social Life Cycle Assessment: A Review of Frameworks, Theories, and Empirical Experience.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (6): 1547–1565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12663.

- Leistritz, Larry, and Murdock, Steve. International Institute of Sustainable Development, 6 February 2016. Social Impact Assessment . doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07349165.1984.9725505

- Martínez-Blanco, J., A. Lehmann, Y. J. Chang, and M. Finkbeiner. 2015. “Social Organizational LCA (Solca)—a New Approach for Implementing Social LCA.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 20 (11): 1586–1599. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-015-0960-1.

- Mathe, S. 2014. “Integrating Participatory Approaches into Social Life Cycle Assessment: The SLCA Participatory Approach.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 19 (8): 1506–1514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-014-0758-6.

- Nguyen, L., B. Szkudlarek, and R. G. Seymour. 2015. “Social Impact Measurement in Social Enterprises: An Interdependence Perspective.” Can J Adm Sci/Rev Can Des Sci l’Administration 32 (4): 224–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1359.

- Nichols Applied Management Management and Economic Consultants. 2016. Benga Mining Ltd. Grassy Mountain Coal Project Socio-Economic Impact Assessment.

- Norris, C. B., D. Aulisio, and G. A. Norris. 2012. “Working with the Social Hotspots Database - Methodology and Findings from 7 Social Scoping Assessments.” Leveraging Technol A Sustain World 581–586. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29069-5_98.

- Peruzzini, M., F. Gregori, A. Luzi, M. Mengarelli, and M. Germani. 2017. “A Social Life Cycle Assessment Methodology for Smart Manufacturing: The Case of Study of A Kitchen Sink.” J Ind Inf Integr 7: 24–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jii.2017.04.001.

- >Petti, L., M. Serreli, and S. D. Cesare. 2018. “Systematic Literature Review in Social Life Cycle Assessment.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 422–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1135-4.

- Poverty Reduction Group (PRMPR) and Social Development Department (SDV). 2003. A User’s Guide to Poverty and Social Impact AnalysisWashington, D.C. (2 February 2019). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/278581468779694160/A-users-guide-to-poverty-and-social-impact-analysis

- Rafiaani, P., T. Kuppens, V. D. Miet, H. Azadi, P. Lebailly, and V. P. Steven. 2018. “Social Sustainability Assessments in the Biobased Economy: Towards a Systemic Approach.” Renew Sustain Energy Rev 82 (August 2017): 1839–1853. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.118.

- Reap, J., F. Roman, S. Duncan, and B. Bras. 2008a. “A Survey of Unresolved Problems in Life Cycle Assessment.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 13 (4): 290–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-008-0008-x.

- Reitinger, C., M. Dumke, M. Barosevcic, and R. Hillerbrand. 2011. “A Conceptual Framework for Impact Assessment within SLCA.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 16 (4): 380–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-011-0265-y.

- Ren, J., and S. Toniolo. 2020. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Decision-Making. Elsevier. 978-0-12-818355-7 . doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/C2018-0-02095-2.

- Shang, Z., M. Wang, S. Daizhong, Q. Liu, and S. Zhu. 2018. “Ontology Based Social Life Cycle Assessment for Product Development.” Adv Mech Eng 10 (11): 168781401881227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814018812277.

- Siebert, A., A. Bezama, O. Sinéad, and T. Daniela. 2018b. “Social Life Cycle Assessment: In Pursuit of a Framework for Assessing Wood-Based Products from Bioeconomy Regions in Germany.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 23 (3): 651–662. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1066-0.

- Siebert, A., S. O’Keeffe, A. Bezama, W. Zeug, and D. Thrän. 2018a. “How Not to Compare Apples and Oranges: Generate Context-Specific Performance Reference Points for a Social Life Cycle Assessment Model.” Journal of Cleaner Production 198: 587–600. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.298.

- Sierra, L. A., E. Pellicer, and V. Yepes. 2017. “Method for Estimating the Social Sustainability of Infrastructure Projects.” Environ Impact Assess Rev 65 (April 2016): 41–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.02.004.

- Spierling, S., E. Knüpffer, H. Behnsen, M. Mudersbach, H. Krieg, S. Springer, S. Albrecht, C. Herrmann, and H.-J.-J. Endres. 2018. “Bio-Based Plastics - A Review of Environmental, Social and Economic Impact Assessments.” Journal of Cleaner Production 185 (June): 476–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.014.

- Subramanian, K., and W. K. C. Yung. 2018. “Modeling Social Life Cycle Assessment Framework for an Electronic Screen Product – A Case Study of an Integrated Desktop Computer.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 417–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.193.

- Sureau, S., B. Mazijn, S. R. Garrido, and W. M. J. J. Achten. 2018. “Social Life-Cycle Assessment Frameworks: A Review of Criteria and Indicators Proposed to Assess Social and Socioeconomic Impacts. Int.” J Life Cycle Assess 23 (4): 904–920. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-017-1336-5.

- Tsalidis, G. A., D. S. Elena, J. J. E. Gallart, J. B. Corberá, F. C. Blanco, U. Pesch, and G. Korevaar. 2021. “Developing Social Life Cycle Assessment Based on Corporate Social Responsibility: A Chemical Process Industry Case regarding Human Rights.” Technol Forecast Soc Change 165 (April): 120564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120564.

- United Nations Environmental Programme. 2007. “Dams and Development: Relevant Practices for Improved Decision-Making.” A Compendium of Relevant Practices for Improved Decision-Making on Dams and Their Alternatives. (24 May 2019). https://wedocs.unep.org/rest/bitstreams/11346/retrieve