ABSTRACT

As craft breweries and craft brewing events have grown in size and number worldwide, it is important to understand the experiences of craft event attendees, ensuring the event is successful. To facilitate this understanding, festivalscape experiences were measured to determine the types of experiences that festival attendees prefer at a craft beer festival. Festivalscape represents the atmosphere and the quality experiences that a festival attendee receives when attending an event. Festival attendees can be male or female. Traditionally more men than women attend craft brewing events, but more and more females are showing interest in craft beer and attending craft-related events. Men and women may experience craft beer and craft beer events differently. Thus, the current study includes two primary objectives: (1) To develop a model of success for a craft beer and food festival and (2) To determine if craft beer experiences differ across gender. Researchers surveyed visitors attending the North Miami Brewfest in North Miami, Florida, United States. Structural equation modeling was employed to examine the relationships among festivalscape, attitude toward attending the festival, and word-of-mouth. Multi-group analysis was applied to explore the moderating role of gender.

Introduction

Craft beer and craft brewing festivals are a growing phenomenon throughout the world. Of all festival types (holiday, cultural, wine, craft beer, art, food, music, etc.) craft beer festivals are amongst the fastest-growing niche festivals worldwide (Fletchall, Citation2016). This growth is aided by the recent increase in the number of craft breweries in the United States. Since 2014, the amount of craft breweries in the United States has grown from 3,464 breweries to more than 8,000 craft breweries (at year-end 2019) (Hertz, Citation2019; Kell, Citation2015). As the number of craft breweries and interest in craft beer increases, it is important to understand the craft beer consumer and the types of experiences they prefer when attending a craft beer-related event.

When people attend craft beer-related events the type of quality and memorable experiences that they receive at these events can be captured via the festivalscape (Crompton & Love, Citation1995; Richards, Citation2020). The festivalscape represents the atmosphere and the quality attributes that make up a festival (Chou et al., Citation2018). To date, few prior studies have measured the quality experiences of the festivalscape in a craft beer festival setting. The quality experiences that influence success of a craft beer festival may be different than those that influence the success of a cultural festival, music festival, or food festival (Selmi et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2019). Further, these quality experiences of the festivalscape may be perceived differently across gender as craft brewing and craft beer is a traditionally male-oriented industry (Murray & O’Neill, Citation2012). Appealing to those festivalscape experiences that interest different gender groups may create more awareness, curiosity, and excitement for craft beer events. This illustrates the importance of quantifying and understanding the festival experiences of craft beer attendees among both males and females. As a result, researchers and event managers will know the festival attributes that can influence the success and revisit intention of an annual craft beer festival.

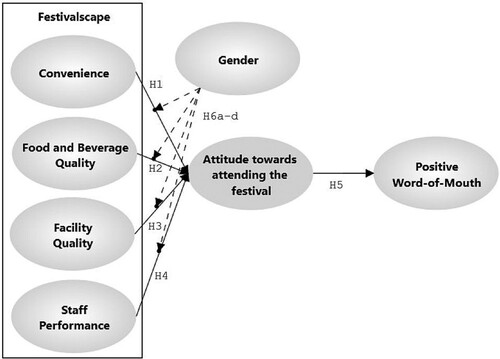

Perceptions of festival event attendees in the hospitality industry are driven by experiences. Many of these festival experiences are positive and unique, providing a positive attitude and satisfaction towards an event, which generally results in favorable outcomes such as positive word-of-mouth recommendations (Baker & Crompton, Citation2000; Davras & Özperçin, Citation2021; Vesci & Botti, Citation2019). To explore this phenomenon, and to determine the overall quality experiences that craft beer consumers prefer, researchers created a theoretical model utilizing festivalscape (to quantify experiences) and resulting factors such as attitude towards the festival and positive word-of-mouth. In addition to the development of a unique success model for craft beer festivals, the authors selected gender as an important factor to understand for future marketers of craft beer related events and craft beer festivals. As mentioned above, the craft beer industry and craft brewing interest has been a male dominated industry. Thus, an important research gap for this study is to explore the differences in festivalscape experience preferences across gender groups. As more females take an interest in craft beer around the world, it is important for event managers to understand female festivalscape experience preferences. The understanding of such experience preferences will allow event managers to appeal to these female experience preferences thus craft-beer related events can be more successful and sustainable annually. To determine differences in preferences across gender, the authors explored whether gender moderates the relationship between festivalscape experiences and attitude towards attending the festival.

To address the above objectives and research gaps, first a background of craft brewing, craft breweries and craft brewing events will be discussed. Next, a background and review of the seminal research on festivalscape is presented outlining the types of festivals that festivalscape has been applied (e.g. cultural, food, music). The authors then present the hypotheses for the path model and justification for the craft beer success model. Next, the methodology is discussed, including data collection and resulting descriptive statistics. Further, the path model is computed including the CFA and a test of the structural model. Results are presented and interpreted along with differences in the pathways across gender groups. Lastly implications are discussed followed by limitations and recommendations for future research.

Literature review and hypotheses

Craft brewing, craft breweries and events

Craft beer related research has captured the attention of scholars in recent years (Alonso & Bressan, Citation2017; Bachman et al., Citation2021; A. Murray & Kline, Citation2015). Generally, craft beer refers to small brewing facilities (e.g. microbreweries, brewpubs, home-breweries, nano-breweries) that produce relatively small amounts of beer when compared with global mega-brewers (Elzinga et al., Citation2015). In today's world, craft brewing is seen as a beverage concept emphasizing quality, flavor, diversity, and limited production, as opposed to traditional beer production processes (Gatrell et al., Citation2018).

Craft breweries in the United States are defined as breweries that produce less than 6 million barrels annually. In the United States, there are over 8,000 breweries, with more than 98% considered craft breweries (Hertz, Citation2019). The increased popularity of craft breweries can be attributed to the innovation, creativity, and authenticity of microbreweries, which offer enjoyable, memorable, pleasurable experiences that reinforce belonging, self-fulfillment, and social recognition (Donadini & Porretta, Citation2017). According to Murray and Kline (Citation2015), craft breweries receive further popularity and loyalty to their brand due to their connection with the community, desire for unique consumer products, and satisfaction. Craft breweries further emphasize their places in local communities by providing venues for community gatherings (Bachman et al., Citation2021).

Breweries promote craft beer through their offering of tasting rooms from which locals and tourists can visit, take a tour of the brewery, and taste the beer on-site. Breweries also promote their brand through social media, posting pictures, updated beer offerings and various promotions. Additionally, local bars and restaurants may offer local craft beers as an option for consumers. Furthermore, some craft brewers bottle their beers for sale in local and regional grocers and alcoholic beverage stores. Lastly, breweries promote their brand by participating in various beer festivals and beer-related events (Hollows et al., Citation2014; Ikäheimo, Citation2020; Murray & Kline, Citation2015). The number of festival events and opportunities for breweries to participate and promote their product increases each year (Hodge et al., Citation2021). Quantifying the experiences of beer consumers at these events can help brewers promote their products and influence the success of craft beer festival events (Hermann et al., Citation2020).

Festivalscape

Consumer experiences of an event is important for event managers as positive experiences are often presented and perceived as festival quality (Biaett & Richards, Citation2020). For example, Crompton and Love (Citation1995) measured the experiences (festival quality) of visitors to a Christmas-themed festival in Galveston, Texas, United States. Each item on the 22-item scale was presented as an individual attribute (i.e. quality of the entertainers, quality of food and beverage, variety of gifts at the booths). The above research was influential when Lee et al. (Citation2008) proposed a model indicative of festival quality called ‘festivalscape.’ Festivalscape represents the atmosphere that festival-goers experience while attending the festival. This atmosphere is multifaceted and comprises tangible service facilities and intangible services/programs (Chou et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2008; Yang et al., Citation2011). To measure the festivalscape atmosphere, Lee et al. (Citation2008) conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the measurement items for festivalscape. This EFA result included the factor groups program content, facility availability/quality, staff demeanor, souvenir availability/quality, food perceptions, information availability and convenience (Lee et al., Citation2008). These factors and associated items were derived from prior research on retail atmospherics and servicescapes (Baker, Citation1986; Bitner, Citation1992; Lee et al., Citation2003; Lee et al., Citation2008). In addition to Lee et al. (Citation2008), previous studies (see ) have examined festivalscape experiences utilizing a path model to explain relationships among dependent variables. Some of the dependent variables utilized in prior studies include value, satisfaction, loyalty, emotions, intention, motivation, and attitude (Choo et al., Citation2016; Choo & Park, Citation2017; Grappi & Montanari, Citation2011; Lee & Chang, Citation2017; Mason & Paggiaro, Citation2012; Yoo et al., Citation2020; Yoon et al., Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Prior studies utilizing festivalscape in festival events.

Value and attendee satisfaction are among the most used dependent variables featured in a path model involving festivalscape experiences. For example, Lee et al. (Citation2009) conducted a study on the Punggi Ginseng Festival to identify which festivalscape dimensions differ across first-time and repeat festival attendees. They discovered that two dimensions (programs and convenient facilities) are antecedents of value for repeat attendees, while four dimensions (food, souvenirs, programs, and convenient facilities) are value antecedents for first timers. Lee et al. (Citation2011) compared emotional and functional value in a study of the Boryeong Mud Festival. They found that positive emotional value was a direct result from festivalscape factors festival programs and natural environment. Additionally, Yoon et al. (Citation2010) found that festival value was positively associated with festival satisfaction, which positively affected festival loyalty. Furthermore, Song et al. (Citation2014) identified four festivalscape dimensions (program, hospitality, venue, and convenience) to examine the impact of the festivalscape on tourists’ satisfaction, trust, and support at a Korean Oriental medicine festival. Findings from the study indicated that the program factor of festivalscape was a significant antecedent of tourists’ satisfaction. Next, Choo and Park (Citation2017) suggested that festival organizers should focus on the festivalscape factors program, information service, and environment to ensure that local visitors have a satisfying experience so they will come back and spread positive word of mouth.

Previous studies have also investigated the role played by emotions in the relationship with attendees’ satisfaction and behavioral intention. Grappi and Montanari (Citation2011) examined how emotions, hedonic value, satisfaction, and social identification mediated the impact of environmental factors on attendees’ re-patronizing intention. Mason and Paggiaro (Citation2012) identified three factors of festivalscape (food, comfort, and fun) associated with an Italian food and wine festival. Furthermore, they found these festivalscape factors positively affect emotions and satisfaction. Lee and Chang (Citation2017) discovered that the festivalscape factors program and facilities had a significant and positive effect on emotions at two cultural festivals in Taiwan. Additionally, the authors found that the festivalscape factor informational services had a significant negative influence on emotional experience (Lee & Chang, Citation2017).

Prior scholars have applied other theoretical frameworks to help understand consumer experience of the festivalscape. For example, Choo et al. (Citation2016) created an integrated theoretical model which incorporated festivalscape and the theory of planned behavior. The integrated model was utilized to predict revisit intention and satisfaction for a food festival in South Korea. Similarly, Vesci and Botti (Citation2019) also created an integrated model featuring the theory of planned behavior and festivalscape. This model was used to predict visitor attitude and revisit intention for visitors to culinary festivals in Southern Italy. The results of their study indicated that the festivalscape factor food and beverage quality had a significant and positive impact on visitors’ attitude toward visiting local festivals. Additionally, the festivalscape factors staff interaction and services and information sources both had a positive effect on visitors’ attitude toward visiting local festivals (Vesci & Botti, Citation2019).

Festivalscape → attitude towards attending the festival

Prior research indicates that festivalscape factors influence festival attendees’ attitude towards attending the festival. For instance, Vesci and Botti (Citation2019) found that three festivalscape factors (food and beverage quality, staff behavior, information adequacy) directly influenced visitor attitudes toward visiting a local festival. Similarly, Quintal et al. (Citation2015) tested a model of winery quality called ‘winescape’ and found that some factors of winescape (service staff, wine value) were significant predictors of attitude towards the winery. Additionally, prior retail literature has indicated that quality products directly influence consumer attitudes toward the product (Anderson et al., Citation1994; Fornell, Citation1992). Sparks (Citation2007) indicated that the overall experience of a wine festival influences the attitude towards that festival. Additionally, beverage quality has been found to affect wine consumer attitudes (Dodd & Gustafson, Citation1997). In another study, the quality of service provided (staff performance) was found to affect consumer attitudes (Tian-Cole & Cromption, Citation2003). Lastly, signage and available information (convenience) has been found to be an important factor in predicting consumer attitudes (Griffin et al., Citation2006; Vesci & Botti, Citation2019). Thus,

H1: The festivalscape factor convenience will result in a positive attitude towards attending the festival.

H2: The festivalscape factor food and beverage quality will result in a positive attitude towards attending the festival.

H3: The festivalscape factor facility quality will result in a positive attitude towards attending the festival.

H4: The festivalscape factor staff performance will result in a positive attitude towards attending the festival.

Attitude towards attending the festival → positive word of mouth

When festival consumers engage and experience a specific festival event, they formulate an attitude about that event. This attitude encompasses one’s feelings and beliefs (favorable and unfavorable) about attending the event, including whether or not they would consider participating again in the future (in the case of an annual festival) (Ajzen, Citation1991; Murray & Bellman, Citation2011). If festival consumers have positive feelings about an event, they will be more likely to spread positive words about that event to friends, family, co-workers, and on social media (Choo & Park, Citation2017; Mason & Paggiaro, Citation2012; Richards, Citation2020). Thus,

H5: A craft beer and food festival consumer with a positive attitude toward attending the festival will be more likely to spread positive word-of-mouth about the annual festival.

Gender and the festivalscape

Previous studies on the festivalscape have indicated a gender profile often including more females than males (see ). For instance, the majority of festivalscape studies featuring food festivals and food and wine festivals have included a gender profile including more females than males (Choo et al., Citation2016; Choo & Park, Citation2017; Vesci & Botti, Citation2019; Yoo et al., Citation2020). Additionally, cultural festivals in festivalscape studies have also indicated a higher female response than male response (Grappi & Montanari, Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2009; Lee & Chang, Citation2017; Santos et al., Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2019). As a contrast, though festivalscape experiences have not been applied to beer festivals, other prior survey research on beer festivals has indicated that the majority of respondents identify as male (Fountain & Ryan, Citation2015; Harrington et al., Citation2017; Hodge et al., Citation2021; Long et al., Citation2018).

The moderating role of gender

As mentioned above, prior research has indicated that the craft beer industry is a male-oriented market (Murray & O’Neill, Citation2012). Nevertheless, more and more females are participating in craft beer brewing, craft beer consumption, and craft brewing festivals (Coetzee & Lee, Citation2017; Graefe & Graefe, Citation2021; Long et al., Citation2018). This trend is important as researchers assess the differences in experiences among craft beer festival consumers. For this study, individual differences across gender are explored. Ahn et al. (Citation2020) recognized the importance of gender as a moderator when they explored the role of gender among motivations, perceived value, e-wom, and visitor satisfaction at a music, food, and art festival. The authors found differences in perceived value (3-item scale) and satisfaction among gender groups. Other prior studies have indicated significant differences across gender when experiencing hospitality and tourism related products (Han & Ryu, Citation2007; Jin et al., Citation2013). Thus,

H6a: The gender of festival attendees will moderate the relationship between the festivalscape factor convenience and attitude towards attending the festival.

H6b: The gender of festival attendees will moderate the relationship between the festivalscape factor food and beverage quality and attitude towards attending the festival.

H6c: The gender of festival attendees will moderate the relationship between the festivalscape factor staff performance and attitude towards attending the festival.

H6d: The gender of festival attendees will moderate the relationship between the festivalscape factor facility quality and attitude towards attending the festival .

Methodology

Researchers and volunteers collected data at a local craft beer and food festival called North Miami Brewfest (NMB) in North Miami, Florida. Sample respondents included festival visitors approached randomly by volunteers and researchers during the one-day festival. Measurement scales utilized in the current study were adapted from prior research. Scale items for festivalscape were adapted from Lee et al. (Citation2008); attitude towards attending the festival from Murray and Bellman (Citation2011), and scale items from world-of-mouth from Maxham (Citation2001). All scale items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). In addition, researchers collected demographic characteristics (including gender, age, income, education, marital status) of the festival participants.

Data collection

Prior to the event, a pilot survey was administered to a small craft beer-related event to ensure the comprehension of each of the questions. After the pilot survey and subsequent revision, a street-intercept survey was employed during the festival to randomly sample respondent attendees at the North Miami Brewfest. In surveying during the event, the effect of memory-based bias was diminished. Those that were surveying (students, researchers) randomly approached various cues at the brewery tents and restrooms. This method proved most fruitful as respondents were happy to fill the time while they waited for the front of the cue. Upon approach, researchers and volunteers introduced themselves and quickly explained the purpose of the survey. Upon completion researchers and volunteers thanked participants for their contribution to the study.

Of the surveys collected, 204 were usable and completed. Respondents consisted of drinking age adults (21 years or older). The response rate of festival attendees was approximately 85%. Approximately 10 surveys had missing values and were discarded. All but 4 respondents (98%) were Florida, United States residents. Of the adult attendees, 56.9% were female (43.1% male) and the average age of respondents was approximately 35 years old. Ethnic groups in the sample were characterized by 56.9% Hispanic, 20.6% Caucasian, 8.3% African American, 3.9% Asian and 10.3% other. Education levels of respondents included graduate or professional degree (34.8%), 4-year college degree (41.7%), some college (13.7%) and high school graduate or equivalent (4.4%). Household income of respondents included 24.9% greater than $100 000, 33.1% between $60,000 and $100,000, and 42% less than $60,000.

Data analyses

The measurement model was tested by utilizing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the hypotheses were tested through the usage of a structural equation (SEM) model (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The analysis was applied via the software packages IBM SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 22. Model fit for the CFA and the structural model (SEM) was measured utilizing chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Cutoff criteria indicating acceptable model fit includes > 0.90 for CFI, NFI and TLI and < 0.08 for RMSEA (Bentler & Bonett, Citation1980; Byrne, Citation2010; Hair et al., Citation2019; Huang & Rundle-Thiele, Citation2014; Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2016). All measurement items were checked for normality. The result of this check indicated that measurement items had kurtosis beta values less than 7, indicating no evidence of non-normality (Byrne, Citation2006).

Results

The researchers ran confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) including 6 factors and 20 measurement items. The confirmatory factor analysis showed adequate model fit: χ2 = 314.928, df = 150, χ2/DF = 2.1; CFI = 0.938; TLI = 0.922, NFI = 0.912 and RMSEA = 0.074. The loadings for each factor were greater than 0.5 which is the standard rule of thumb for confirmatory factor analysis. Factor loadings of 0.5 or higher verify that the associated item indicators are highly related to their constructs and help to confirm construct validity (Hair et al., Citation2019). Construct validity was established via convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was obtained by the average variance extracted (AVE) for all the constructs being greater than 0.5. Composite reliabilities (CR) of each factor surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.70 (see ) (Hair et al., Citation2019). Discriminant validity was substantiated via the average variance extracted (AVE) values being greater than shared variances of all conceivable pairs of latent variables (See ) (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Measures.

Next, the research model was estimated using a structural equation model (SEM). The independent variables included festivalscape (Convenience, food/beverage quality, facility quality, staff performance) and the dependent variables comprised of attitude towards attending the festival and word-of-mouth recommendation. The structural model provided satisfactory model fit indices: χ2 = 323.696, df = 156; χ2/DF = 2.075; CFI = 0.937; TLI = 0.923; NFI = 0.911; RMSEA = 0.073. The results of the proposed model and hypotheses are outlined in . Concerning H1 thru H4, three out of four festivalscape factors positively influenced attitude towards attending the festival. Convenience (β = .049, p > .05) did not influence attitude towards attending the festival, which did not support H1. Food/beverage quality (β = .219, p < .01), festival staff (β = .184, p < .01) and facility (β = .533, p < .001) all positively influenced attitude towards attending the festival, confirming hypotheses H2 thru H4. Next, attitude positively influenced word-of-mouth (β = .991, p < .001), supporting H5 (see ).

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

Table 4. Hypotheses testing results.

Multiple-group analysis (Gender as a moderator)

portrays the result of the moderating role of gender on the pathway from festivalscape → attitude towards attending the festival. To test the moderation of gender, a multiple group analysis was employed. Sample respondents were split into two groups: people that identified as male (n = 88) and people who identified as female (n = 116). In order to compute this multi-group analysis, an unconstrained model was measured with zero pathways constrained (Byrne, Citation2004). This unconstrained model showed a satisfactory fit to the data (χ2 = 574.715, df = 312, CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.918, NFI = 0.915, RMSEA = 0.065). After the unconstrained model was measured, the authors then compared the unconstrained model to a constrained model (χ2 = 633.595, df = 331, CFI = 0.925, TLI = 0.914, NFI = 0.909, RMSEA = .067) using a chi-squared difference test (Prebensen et al., Citation2016). The Chi-square difference between the constrained and unconstrained model was 58.88 with 19 degrees of freedom, significant at p < 0.001. This difference indicates that moderating effects are present.

Table 5. Result of the moderating effect.

Each hypothesis path was constrained (H6a-d) one-by-one to test if the pathways were different across gender groups (male, female). Firstly, the moderating effect of gender between convenience and attitude towards attending the festival was tested (H6a). The resulting model presented a good fit (χ2 = 583.338, df = 313, CFI = 0.914, TLI = 0.908, NFI = 0.904, RMSEA = 0.065). The chi-square comparison between the unconstrained model and the constrained models specified that the constrained pathway (convenience → attitude towards attending the event) between the male and female festival attendees is significantly different (Δχ2/Δdf = 8.62(1), p < .001). For those volunteers who were female, the effect of convenience on attitude towards volunteering was significant and positive while this moderating role of convenience → attitude was significant and negative for males.

Next, the moderating effect of gender between food and beverage quality and attitude towards attending the festival was tested (H6b). The resultant model showed a good fit (χ2 = 578.848, df = 313, CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.908, NFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.065). The chi-square comparison between the unconstrained model and constrained model specified that the constrained pathway (food and beverage quality → attitude towards attending the event) between male and female gender specification is significantly different (Δχ2/Δdf = 4.43(1), p < .05). For male festival attendees, their food and beverage quality perception positively affected their attitude towards attending the festival, while this moderating role and relationship did not exist for female festival attendees.

Further, the moderating effect between facility quality and attitude towards attending the festival was tested (H6c). The resulting model showed a good fit (χ2 = 578.625, df = 313, CFI = 0.922, TLI = 0.917, NFI = 0.906, RMSEA = 0.065). The chi-square comparison between showed that the constrained pathway (facility quality → attitude towards attending the event) between the male and female groups was significantly different (Δχ2/Δdf = 3.91(1), p < .05). For those volunteers who were female, their gender identification strengthened the effect of the facility quality dimension on their attitude towards attending the event. This moderating role did not exist for those who identified as male.

Lastly, the moderating effect of staff performance on attitude towards attending the festival was tested (H6d). The resulting model showed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 574.943, df = 313, CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.910, NFI = 0.902, RMSEA = 0.064). The chi-square comparison (unconstrained model and the constrained model) indicated that the constrained pathway (staff performance → attitude towards attending the event) between the male and female groups was not significantly different (Δχ2/Δdf = 0.23(1), p > .05).

Discussion and conclusion

This study identified important experience factors among the festivalscape that can influence one’s positive attitude towards attending the festival and ultimately an intention to speak fondly of the festival to their friends/family. Important success factors for festivals to consider include facility quality, food and beverage quality, and staff performance. Each of these factors predicted positive attitude towards attending the festival and ultimately an intention to speak positively of the festival. The variable ‘attitude towards attending the festival’ was added to the model to mediate the relationship between festivalscape factors and word-of-mouth. This attitude-related mediator was important in the model as it provided evidence of an indirect relationship from festivalscape to positive word-of-mouth through the mediating factor (attitude towards attending the festival). The measurement items from the attitude mediator adopted from Murray and Bellman (Citation2011) provided a more tailored scale to this study as the scale is intended to measure attitude towards an activity or game. Next, three of the four hypotheses including the moderator ‘gender’ were significant, indicating that festival attendees view each dimension of the festivalscape experience differently across gender. These results support and extend prior research that indicates significant differences between males and females when consuming a (festival) product or service (Ahn et al., Citation2020; Han & Ryu, Citation2007; Jin et al., Citation2013).

Managerial and practical implication

Results of this study provide practical implications for event managers and stakeholders in the craft brewing industry as they seek to create interest in craft beer and craft brewing related events and festivals. First, three festivalscape factors were identified as the most relevant to predict attitude towards attending the festival (food and beverage quality, facility quality, and staff performance). This confirms prior research that indicates a significant relationship between festivalscape and attitude (Vesci & Botti, Citation2019). For the food and beverage festivalscape factor, craft beer festivals should be aware to provide quality food with the beer and provide breweries with ice to keep the beer cold and fresh for festival consumers. Results of the moderator gender indicated that this relationship was strongest and significant among males, but not significant among females. Males may have more interest in beer quality and food quality than those of the female group. As mentioned above, females are relatively new to the craft brew scene and are developing their knowledge and taste for craft beer. For facility quality, festival organizers should be sure that the festival site is clean and spacious, with an easy to navigate layout. Results of the moderator gender indicated that this relationship was strongest and significant among the female group but was not significant among the male group. Those that were female craved the quality layout, and cleanliness of the festival site, which enhanced their positive attitude towards attending the festival. Next, for staff performance, festival staff should be trained, knowledgeable, and friendly with the festival consumer. Results of the moderator gender showed that the relationship between festival staff and attitude towards the festival was not different across gender.

Lastly, the convenience factor of festivalscape was not a significant predictor for attitude towards the festival (when including males and females together). Nevertheless, when splitting the sample into two groups, multi-group analysis indicated that the relationship between convenience and attitude was significant and differed across gender. For the male group, there was a significant negative relationship between convenience and attitude towards attending the festival. For females, this relationship was positive and significant. The negative relationship between convenience and attitude for males may be a festival specific result for North Miami Brewfest and may not apply to other festivals. For instance, some male festival participants may have perceived the festival to be in an inconvenient location, with inaccessible and difficult to find parking and restrooms. Researchers observed that some of the restroom lines were abnormally long, which may have contributed towards this result. For females, the experience of the convenience factor resulted in a strong positive attitude towards attending the festival. Females may have felt more strongly positive about convenient parking, ample places to sit down, and easy to find restrooms which in turn led to a positive attitude towards attending the festival. Festival managers (of all craft-beer festivals) should take note and focus on these convenience attributes to appeal to females attending the festival.

Overall, if craft beer festival festivalscape experiences above are positive and memorable, festival attendees will be more likely to enjoy the festival, return to the annual festival in the future, and ultimately speak positively of the festival to family and friends. The types of festival experiences (food/beverage quality, convenience, festival staff, facility) should be emphasized by other craft brewing events as they proved to be important in predicting a positive attitude towards attending the festival. Determining how to influence positive festivalscape experiences should be a primary goal of planners of craft beer and food festivals. Festival planners and managers can particularly focus on the festivalscape experiences that influence attitudes towards attending the festival.

In summarizing the above differences in experience preferences across gender, females preferred convenience and facility quality experiences, while males preferred a quality food and beverage experience. For females and facility quality, festival planners and managers should focus on the formation of a spacious, comfortable, clean, and easy-to-navigate festival site. For convenience, festival planners and managers should provide females ample places to lounge/sit-down and relax, convenient and easy to access parking, and easy to find pairing/educational sessions and restrooms.

For males and food/beverage quality, it is important to provide quality food and craft beer, a variety of food/beer, and enough food/beer for everyone throughout the event. For the craft beer, it is important for festival organizers be sure the beer is cold, with plenty of ice available for the brewers (during the festival). Next, male craft beer consumers prefer flavors and varieties of beer they may not see at the grocery store or the brewery. Festival managers should encourage craft brewers to include special pours, which can include special flavors and varieties that are festival specific and not available for retail sale (Johnson, Citation2019; Sawyer, Citation2016). Lastly, many craft brew festivals only offer beer with the ticket price. Food is not included in many brew festivals, thus it can be a differentiating value to provide participants with quality local food as part of the event and ticket price (Alshammari & Kim, Citation2019).

For festival staff, this festivalscape experience was not different across gender, but it still was an important factor overall in predicting a positive attitude towards attending the festival. The appropriate number of event managers, staff, and volunteers is important when producing a craft brewing festival. Festival staff help keep the event clean, answer questions of attendees, scan tickets to enter the festival in a timely manner, and assist beer/food vendors with keeping their products warm/cool, etc. Training staff prior to the festival is important such that the above duties can be performed in an efficient, timely manner such that both vendors and attendees are pleased with staff performance and wish to attend and speak positively of the event in the future (Grate, Citation2017).

Theoretical implication

This study provided a thorough examination of Festivalscape Theory to understand the to understand the types of experiences that craft beer festival attendees crave when attending an event. Further important was the exploration of the moderating role of the gender and its effect on the relationship between festivalscape and attitudes toward attending the festival. For example, males with a strong food and beverage quality experience resulted in a positive attitude towards attending the festival (not significant for females). Additionally, few studies have utilized ‘attitude’ as a mediator between festivalscape and behavioral intentions such as word-of-mouth. The important role of the mediator, attitude towards attending the festival was confirmed. The mediator attitude towards attending the festival positively impacted positive word-of-mouth which specified an indirect relationship between festivalscape and positive word-of-mouth. If a festival attendee had a positive attitude towards attending the festival (I enjoyed North Miami Brewfest, I liked this beer festival, I want to go back to North Miami Brewfest again), this affected their intention to speak positively of the festival to family and friends (positive word-of-mouth).

Recommendation for future studies

This study quantified the festivalscape factors important to beer festival attendees and provided essential contributions for future studies. The four important festivalscape factors (convenience, food quality, facility quality, staff performance) for craft beer and food festivals can be applied to other craft beer festivals to understand the performance of the festival and determine the relationship between festivalscape and other factors (e.g. loyalty, value). Furthermore, the moderating role of gender delivered unique insight when crafting experiences for those identifying as male or female. Different festivalscape experience factors offer different appeals depending upon the gender identification of festival attendees. When considering gender and the festivalscape, future studies may also look to the group dynamics of each attendee. For example, males attending the festival with other males may have experienced the festival differently than males who attended the festival with other females. In addition to the moderating role of gender, future studies may examine other moderators (e.g. age, income level) which help to understand the festivalscape experiences craved by (craft beer) festival attendees.

Festivalscape experiences significantly affected the mediating role of attitude towards attending the festival, a mediator seldom used in festivalscape literature but still provided an important role in the model (facilitated an indirect relationship of festivalscape experience and positive word-of-mouth). Future studies may investigate other positive behavioral outcomes influenced by attitude towards attending the festival. These behavioral outcomes may include revisit intention (for an annual festival) and electronic word of mouth (e.g. posting positive images and messaging on social medial about the festival).

Lastly, the authors surveyed at a craft beer and food festival in one area of the Southeastern United States. The United States is a multi-cultural country as demonstrated by the demographics in the study. These demographics included approximately 80% non-white attendees. Of the non-white festival attendees, 56% of the respondents were of Hispanic origin, 8% were African American and almost 4% Asian. Future research studies may survey one or more craft beer festivals in multiple regions in the United States and the rest of the world to increase the generalizability and scope of the research model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahn, J. J., Choi, E. K. C., & Joung, H. W. (2020). Does gender moderate the relationship among festival attendees’ motivation, perceived value, visitor satisfaction, and electronic word-of-mouth? Information (Switzerland), 11(9), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/INFO11090412

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(3), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alonso, A. D., & Bressan, A. (2017). Stakeholders and craft beer tourism development. Tourism Analysis, 22(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14828625279690

- Alshammari, F., & Kim, Y. K. (2019). Seeking and escaping in a Saudi Arabian festival. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 10(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-02-2018-0015

- Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Lehmann, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252310

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Bachman, J. R., Hull, J. S., & Marlowe, B. (2021). Non-economic impact of craft brewery visitors in British Columbia: A quantitative analysis. Tourism Analysis, 26(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354221X16079839951439

- Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

- Baker, J. (1986). The role of the environment in marketing services: The consumer perspective. In J. Czepiel, C. Congram, & J. Shanahan (Eds.), The services challenge: Integrating for competitive advantage (pp. 79–84). American Marketing Association.

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

- Biaett, V., & Richards, G. (2020). Event experiences: Measurement and meaning. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12(3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2020.1820146

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252042

- Byrne, B. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(2), 272–300. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8

- Byrne, B. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Choo, H., Ahn, K., & Petrick, J. F. (2016). An integrated model of festival revisit intentions: Theory of planned behavior and festival quality/satisfaction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(4), 818–838. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2014-0448

- Choo, H., & Park, D. B. (2017). Festival quality evaluation between local and nonlocal visitors for agriculture food festivals. Event Management, 21(6), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599517X15073047237197

- Chou, C. Y., Huang, S. C., & Mair, J. (2018). A transformative service view on the effects of festivalscapes on local residents’ subjective well-being. Event Management, 22(3), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599518X15258072560248

- Coetzee, W., & Lee, C. (2017). The “Ale” in female: The feminine voice at a craft beer fermentation fest. Beyond the Waves: 4th International Conference on Events.

- Crompton, J. L., & Love, L. L. (1995). The predictive validity of alternative approaches to evaluating quality of a festival. Journal of Travel Research, 34(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759503400102

- Davras, Ö., & Özperçin, İ. (2021). The relationships of motivation, service quality, and behavioral intentions for gastronomy festival: The mediating role of destination image. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2021.1968881

- Dodd, T. H., & Gustafson, A. W. (1997). Product, environmental, and service attributes that influence consumer attitudes and purchases at wineries. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 4(3), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1300/J038v04n03_04

- Donadini, G., & Porretta, S. (2017). Uncovering patterns of consumers’ interest for beer: A case study with craft beers. Food Research International, 91, 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2016.11.043

- Elzinga, K. G., Tremblay, C. H., & Tremblay, V. J. (2015). Craft beer in the United States: History, numbers, and geography. Journal of Wine Economics, 10(3), 242–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/jwe.2015.22

- Fletchall, A. M. (2016). Place-making through beer-drinking: A case study of montana’s craft breweries. Geographical Review, 106(4), 539–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2016.12184.x

- Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600103

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fountain, J., & Ryan, G. (2015). “It’s not all beer and skittles”: An exploratory analysis of the characteristics and motivations of beer festival visitors. In CAUTHE 2015: Rising tides and sea changes: Adaptation and innovation in tourism and hospitality (pp. 471–474). Southern Cross University.

- Gatrell, J., Reid, N., & Steiger, T. L. (2018). Branding spaces: Place, region, sustainability and the American craft beer industry. Applied Geography, 90(January), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.02.012

- Graefe, D. A., & Graefe, A. R. (2021). Gender and craft beer: Participation and preferences in Pennsylvania. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 4(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41978-020-00067-y

- Grappi, S., & Montanari, F. (2011). The role of social identification and hedonism in affecting tourist re-patronizing behaviours: The case of an Italian festival. Tourism Management, 32(5), 1128–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.10.001

- Grate, R. (2017). 5 essential steps to planning your festival operations. https://www.eventbrite.com/blog/how-to-plan-a-festival-ds00/

- Griffin, T., & Loersch, A. (2006). The determinants of quality experiences in an emerging wine region. In J. Carlsen & S. Charters (Eds.), Global wine tourism: Research, management and marketing (pp. 80–91). Cabi.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning, EMEA.

- Han, H., & Ryu, K. (2007). Moderating role of personal characteristics in forming restaurant customers’ behavioral intentions: An upscale restaurant setting. Journal of Hospitality \& Leisure Marketing, 15(4), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1300/J150v15n04_03

- Harrington, R. J., von Freyberg, B., Ottenbacher, M. C., & Schmidt, L. (2017). The different effects of dis-satisfier, satisfier and delighter attributes: Implications for oktoberfest and beer festivals. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24(October 2016), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.09.003

- Hermann, U. P., Lee, C., Coetzee, W., & Boshoff, L. (2020). Predicting behavioural intentions of craft beer festival attendees by their event experience. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 33(2), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-05-2020-0019

- Hertz, J. (2019). Big year for small and independent beer in 2019. Brewer’s Association. https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/big-year-for-small-and-independent-beer-in-2019/

- Hodge, M. G., Torsney, B. M., & Paris, J. H. (2021). Ticket to intoxication: Exploring attendees’ motivations for attending craft beer events. Leisure Studies, 1–15. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1948591

- Hollows, J., Jones, S., Taylor, B., & Dowthwaite, K. (2014). Making sense of urban food festivals: Cultural regeneration, disorder and hospitable cities. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2013.774406

- Huang, Y. T., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2014). The moderating effect of cultural congruence on the internal marketing practice and employee satisfaction relationship: An empirical examination of Australian and Taiwanese born tourism employees. Tourism Management, 42, 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.005

- Ikäheimo, J. (2020). Exclusive craft beer events: Liminoid spaces of performative craft consumption. Food, Culture and Society, 23(3), 296–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2020.1741065

- Jin, N., Line, N. D., & Goh, B. (2013). Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 22(7), 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2013.723799

- Johnson, C. (2019). Beer festival 101. https://bigworldsmallgirl.com/beer-festival-must-haves/

- Kell, J. (2015, March). Craft brewers now produce 1 out of every 10 beers sold. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2015/03/16/craft-beers-volume-rising/

- Lee, J. S., Lee, C. K., & Choi, Y. (2011). Examining the role of emotional and functional values in festival evaluation. Journal of Travel Research, 50(6), 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510385465

- Lee, J. S., Lee, C. K., & Yoon, Y. (2009). Investigating differences in antecedents to value between first-time and repeat festival-goers. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 26(7), 688–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400903284511

- Lee, T. H., & Chang, P. S. (2017). Examining the relationships among festivalscape, experiences, and identity: Evidence from two Taiwanese aboriginal festivals. Leisure Studies, 36(4), 453–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2016.1190857

- Lee, Y.-K., Lee, D.-H., Kwon, Y.-J., & Park, Y.-K. (2003). The effects of In-store environment cues on purchase intentions across the three types of Restaurants in korea. International Journal of Tourism Sciences, 3(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980634.2003.11434541

- Lee, Y.-K. K., Lee, C.-K. K., Lee, S.-K. K., & Babin, B. J. (2008). Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 61(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.05.009

- Long, J., Velikova, N., Dodd, T., & Scott-Halsell, S. (2018). Craft beer consumers’ lifestyles and perceptions of locality. International Journal of Hospitality Beverage Management, 2(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.34051/j/2019.5

- Mason, M. C., & Paggiaro, A. (2012). Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1329–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.12.016

- Maxham, J. (2001). Service recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 54(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00114-4

- Murray, A., & Kline, C. (2015). Rural tourism and the craft beer experience: Factors influencing brand loyalty in rural North carolina, USA. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8–9), 1198–1216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.987146

- Murray, D. W., & O’Neill, M. A. (2012). Craft beer: Penetrating a niche market. British Food Journal, 114(7), 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701211241518

- Murray, K. B., & Bellman, S. (2011). Productive play time: The effect of practice on consumer demand for hedonic experiences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(3), 376–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0205-6

- Prebensen, N. K., Kim, H. (., & Uysal, M. (2016). Cocreation as moderator between the experience value and satisfaction relationship. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 934–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515583359

- Quintal, V. A., Thomas, B., & Phau, I. (2015). Incorporating the winescape into the theory of planned behaviour: Examining “new world” wineries. Tourism Management, 46, 596–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.013

- Richards, G. (2020). Measuring the dimensions of event experiences: Applying the event experience scale to cultural events. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12(3), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2019.1701800

- Santos, J. d. F., Vareiro, L., Remoaldo, P., & Cadima Ribeiro, J. (2017). Cultural mega-events and the enhancement of a city’s image: Differences between engaged participants and attendees. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1157598

- Sawyer, K. (2016). Pros spill 6 tips for planning the ultimate beer festival. https://www.eventbrite.com/blog/7-tips-for-planning-the-ultimate-beer-festival-ds00/

- Schumacker, E., & Lomax, G. (2016). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Selmi, N., Bahri-Ammari, N., Soliman, M., & Hanafi, I. (2021). The impact of festivalscape components on festivalgoers ‘ behavioral intentions: The case of the International Festival of Carthage. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 22(4), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/15470148.2021.1887784

- Song, H. J., Lee, C. K., Kim, M., Bendle, L. J., & Shin, C. Y. (2014). Investigating relationships among festival quality, satisfaction, trust, and support: The case of an oriental medicine festival. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 31(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.873313

- Sparks, B. (2007). Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1180–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.11.003

- Tian-Cole, S., & Cromption, J. (2003). A conceptualization of the relationships between service quality and visitor satisfaction, and their links to destination selection. Leisure Studies, 22(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360306572

- Vesci, M., & Botti, A. (2019). Festival quality, theory of planned behavior and revisiting intention: Evidence from local and small Italian culinary festivals. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 38(December 2018), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.10.003

- Yang, J., Gu, Y., & Cen, J. (2011). Festival tourists’ emotion, perceived value, and behavioral intentions: A test of the moderating effect of festivalscape. Journal of Convention and Event Tourism, 12(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/15470148.2010.551292

- Yoo, M., Kitterlin-Lynch, M., Kim, B., Kitterlin, M., & Kim, B. (2020). Motivating and retaining festival patronage. Event Management, 24(4), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599519X15506259856101

- Yoon, Y. S., Lee, J. S., & Lee, C. K. (2010). Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(2), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.10.002

- Zhang, C. X., Fong, L. H. N., Li, S. N., & Ly, T. P. (2019). National identity and cultural festivals in postcolonial destinations. Tourism Management, 73(September 2018), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.013