In November 1936 my father wrote to an old friend: ‘We were going to the Theatre Festival in Russia in September but couldn’t go at the last minute because Rachel and Thomas went down with scarlet fever.’ By then, six of his plays had been produced in London, and eight novels published. Some of these had been translated into Russian, and others would be in the years up to 1945.

In the autumn of 1944, as the war was drawing to a close, he wrote his best-known play, ‘An Inspector Calls’ but could find no London theatre available. In November 1944, he was chosen as President of the Writers Group of SCR – the Society for Cultural Relations between the Peoples of the British Commonwealth and the USSR. Among its aims were to collaborate with the Writers Section of VOKS (The Soviet Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries) and to arrange visits between our two countries.

Failing to find a London theatre, he sent his play to his Russian translator. It was accepted by Tairov’s Kamerny Theatre in Moscow and the Leningrad Comedy Theatre, for two separate productions. My parents were invited to visit Russia by VOKS.

Setting off from Croydon on 8th September 1945 via Germany, they arrived in Moscow on the 11th and saw the Moscow production of An Inspector Calls on the 13th, my father’s birthday. After eight more days in and around Moscow they took the train to Kiev then on to Armenia and Georgia, flying back to Moscow via Stalingrad on 17th October. They took another train to Leningrad from there, leaving Russia on 23 October and travelling back home via Helsinki. It was a journey of seven weeks in all.

My father wrote a series of six articles for a London paper and these were later published in pamphlet form the proceeds for which he donated to the SCR.

My mother wrote copious letters, like a travel journal, which were copied and sent on to her children, my five sisters and me. On 27 single space type sheets she described in detail the experiences and adventures of their journey.

On their return to London she wrote an abbreviated version as an article for the periodical John Bull which came out on 8th December 1945, reproduced here with permission.

December 8, 1945, John Bull

Russia At Home

What are these Russians like at home in their own country? How would they receive you, if you could go there now, and what impressions would you bring away? Here is the answer in an intimate and friendly letter specially written for JOHN BULL.

by Mrs J. B. Priestley

Dear John Bull readers, – You can imagine how eagerly we looked at our first Moscow street. Our hotel had a splendid position, directly across a wide square from the Kremlin. Through a side street we could see the Red Square and Lenin’s Tomb, and farther away the onion-shaped domes and cupolas of St Basil’s Cathedral. On the left was a very high modern block of restaurants, cafes and offices.

It was the rush hour and people were hurrying to the Metro station or bus or tram. They differed from a London crowd only in details—clothes more drab, head shawls on the older women, a great many civilians wearing high leather boots.

It was soon dark. The street lights were brilliant and on each tower at the corners of the long wall enclosing the Kremlin a bright red star stood out against the evening sky.

Next day, our first engagement, which was to plan our itinerary over lunch with our hosts, a group of Russian writers, was not until two o’clock, the usual hour in Moscow. So we went out by ourselves to look round the town.

We went quite freely, just as we would have done in any town anywhere. I say this because so many people thought we would always be carefully shepherded, and I must confess that I had not known what to expect myself.

We walked up Gorky Street, a good wide street with some excellent shops, particularly confectioners and grocers, and some fine new buildings. We went across to the Red Square. I saw the famous old clock that I had occasionally heard on the radio and recognised it when it chimed mid-day.

Churches Inside the Kremlin

We walked down to the Moscow river, and from the bridge saw the beautiful silhouette of the dozens of domes of the churches inside the Kremlin. The Kremlin is a little walled city on high ground above the river—a mixture of Hampton Court, the Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace and Wellington Barracks, all inside these long crenelated walls.

We walked back through the Kremlin gardens and watched the passers by.

There are many climates in the Soviet Union, in fact they have every climate except the tropical. We saw them skating in the north, and saw oranges, tea and tobacco growing in the south.

Our first walk in Moscow was on a drizzling, chilly day and people were already warmly wrapped up, though the chief impression was of dull and shabby clothes, even among the children playing in little parties in the Kremlin gardens. Only an occasional little daughter proudly walking with an officer father was prettily dressed.

Middle-aged women, rather like comfortable nannies, were looking after the children under school age, which is seven in Russia. There were toys and sand pits. Children are international, and when they are little, they play the same games and use the same gestures and have the same enchantment in every country. There was a very good relation between the nannies and the children.

From Moscow, we went to the Ukraine by train. It took two nights and a day and the train crawled along a line that had been torn up and broken in the war. On either side of the line were the wrecks of trains, and every time our train stopped there was only a wrecked station and the rubble of a ruined village. We saw nothing but ruin in all that journey.

The first morning J. B. said, “I couldn’t sleep last night. It sounded as if men were walking about the roof all night,” And when we climbed out of the train and looked up, we saw he was right.

The broad roofs of the train were covered with recumbent figures and there were people between the coaches, riding on the buffers, mostly Red Army men going home. The train only did about fifteen miles an hour and they seemed in good spirits.

The second morning we crossed the wide Dnieper slowly, before dawn, and came to Kiev. Here, as always, we were met by writers, and a representative of the Ukraine Foreign Office because we were now in a different republic. Who would go to Paddington at 6 a.m. to meet a foreign writer?

Kiev, a city on the high Eastern bank of the river, is built on hills that look over the far horizon of a rolling plain. The middle streets of the town are rubble, but beyond, enough remains to show that Kiev was and will again be a beautiful city.

Here there was a different atmosphere. We walked round the streets early that morning and watched the people going to work and shopping. It was warm and the streets were lined with trees. Jackdaws were wheeling over the University building and I heard many familiar small birds too. People were wearing summer clothes and looked jolly. Moscow had been wrapped up and more shut in for the winter. Kiev, still in summer, wore light-heartedly a summer mood.

Free, Happy Atmosphere

We spent a delightful afternoon in a sort of Ranelagh, or perhaps it was more like Blenheim Park—a large park with woods and lakes. Some people had had country chalets there before the war. There were now only ruins left. But there was an excellent open air restaurant. There were boating and swimming on the lakes. There were nets for volley ball and secluded hammocks among the pines.

It was too big to be crowded, but there were many family parties enjoying their Sunday in the country. All these people were vigorous and gay and were extremely well dressed.

There is a free, happy atmosphere. Young people walk arm-in-arm or hand-in-hand. We saw no drunkenness, no rowdiness anywhere at any time, though there was plenty of high spirits. The general impression was one of a vigorous people tremendously enjoying themselves.

An official luncheon in England can be very stiff and heavy. We are a reserved people. The Russians are different. Five minutes after a meal or a party begins you are all great friends and a sort of happy family Christmas party atmosphere prevails.

Plenty of toasts are drunk—vodka, white and red wine and champagne are plentiful, but again never once did we ever see a hint of bad manners or drunkenness. We had been warned that we would be expected to toss off glass after glass of vodka, but although it was offered with great hospitality, it was always possible to be as moderate as one would wish. Even in the peasants’ cottages, where the hostess always wanted us to eat and drink like Gargantua, we were never pressed beyond friendly good manners.

We had two cars at the disposal of our party in Kiev. My husband went in a closed car and had long literary discussions with the Professor of English and a Ukrainian dramatist. I followed with a shy young Voks official in an open car. The driver still wore army uniform, as he had only just been demobilised from a tank division. He had had ten tanks destroyed under him and survived. He had fought at Stalingrad, Leningrad and Berlin.

The Cossack Spirit

Do you remember the Cossack horsemen before the war in a circus or at Olympia? The fiery dash into the ring at full gallop? My ex-tank driver had that spirit. He drove the car at 100 kilometres an hour along a bumpy cobbled road full of potholes and loved to take both hands off the wheel, like a boy going down hill on a bicycle. I asked him to drive more slowly and he dropped to forty. Riding in his car was rather like a few hours on a switchback.

Before we left he brought his wife and little daughter to see me. They were exquisitely neat and nicely dressed and rather shy. His pride in them was tremendous. But this little man was very serious and sad the day we drove out to a collective farm and he showed me a village where the three deep wells had been full of dead children when the retreating German army had passed.

The people in the country showed signs of the tremendous strain of the German occupation. They had aged far beyond their years and there were lines of grief in their faces they will never lose.

They were beginning to have such a good life before the war. The farms were prosperous: clothes and furniture were coming along. Every big farm had schools, nursery schools, crèches, clinics and welfare centres: often a theatre and a clubhouse. The good life was there, but now most of these amenities are destroyed.

Many of the buildings are temporary or inadequate and so much now has to be made all over again. But although they have a long way to go, there is no doubt in their minds. They know they can get what they want, and they are going to work for it. What the German armies have destroyed will be built up again. In republics not overrun by the enemy, as in Georgia and Armenia, the people know they can make a better life for everyone and that is what they are out for.

You can imagine that to spend seven weeks with such a people was the most heart-warming and stimulating experience. We travelled much before the war, but we have never met such warmth and friendliness, and this Russian journey leaves a glow in mind and in heart.—Yours sincerely, Mary Priestley

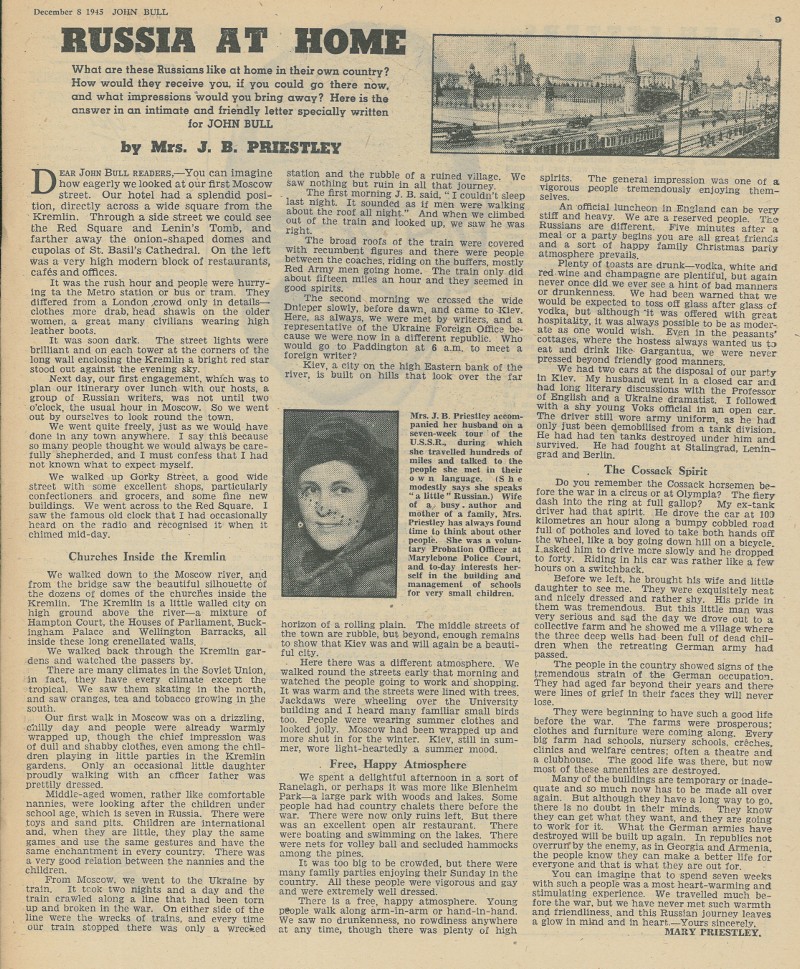

[Caption to photograph]

Mrs J. B. Priestley accompanied her husband on a seven-week tour of the U.S.S.R., during which she travelled hundreds of miles and talked to people she met in their own language. (She modestly says she speaks “a little” Russian.) Wife of a busy author and mother of a family, Mrs Priestley has always found time to think about other people. She was a voluntary Probation Officer at Marylebone Police Court, and to-day interests herself in the building and management of schools for very small children.