ABSTRACT

Against the backdrop of global convergences in education reforms, a growing focus on teacher competences has emerged in European policy discourses about teacher professionalism and professional learning and development that has driven an expanding international and national CPD market involving both state and private operators. Developments in Sweden are an example, and the aim of this article is to identify and explore the discourses on teacher professional learning that seem to proliferate on this newly emerged and expanding market and their connections with and consequences for teacher professionalism. Two sets of data have fed the analysis. These are (a) CPD invoices and (b) interviews with school principals. The analysis indicates that the dominant discourses discursively shape teacher professionalism in relation to ideas about teachers as learners as collegial consumers of knowledge. Policy recommendations about peer learning become a subordinated element of a dominant discourse that prioritises and privileges the agency of knowledge producers, such as consultancies, compared to other actors as intermediaries. Commodification is a new key intermediary process in professional learning for teacher professional development.

Introduction

Towards the end of the previous millennium a series of systemic global education reforms emerged with some shared aims across different countries for changing education investment, education systems and education development (Tatto Citation2006, Beach Citation2010, Ball et al. Citation2017). The acronym GERM, Global Education Reform Movement, used by Sahlberg (Citation2011) describe the neolieberal movement driving the reforms, which had spread from the Anglo-American to the European education policy landscape behind politically driven and economically supported assumptions about competition value, promoted by the World Bank and the OECD. Their main argument was that establishing market-like competition between schools was the best way for improving education quality, equality, and efficiency (Cain Citation2015, Lambirth et al. Citation2019, Sahlberg Citation2023), which although scientifically unproven was enacted in Sweden through the ‘school choice reform’ (Prop. Citation1993/93:230, 1992/93, Prop. Citation1992/92:95) a ‘voucher-system’ that forced pupils and their parents to become ‘customers’ in an increasingly privatised educational market. At the same time, the Swedish school system was decentralised from being nationally to municipally governed, via the ‘municipalization’ reform of public sector services (Proposition, 1990/91:18 in Swedish Kommunaliserings-reformen). Municipalities took responsibility for distributing state funding schools through this reform, including even to the independent, privately run so-called free schools that competed with state schools for pupils on the new market (c.f. Lundahl et al. Citation2013) and in the school law (2010:800) the school principal’s responsibility for local school quality and teachers continuing professional learning (CPD) was stressed. Another educational market increased: a CPD market offering teachers (and principals) continuing professional development (cf. Levinsson et al. Citation2022).

Alongside the GERM-influences in Sweden, an educational discourse emerged about a ‘research- and experienced-based schools’ and teaching. This notion was not new in Sweden, however. As emphasised in the Teacher Education Act from 2010 it had been a cornerstone of both initial and in-service teacher education and development since the beginning of the 1900s (Skog-Östlin Citation2005, Beach and Bagley Citation2012) as a fundamental idea in the Swedish comprehensive school system reform and expansion about basing teaching and professional development on scientific foundations and proven experience (Beach Citation2022). The 1946 School Commission (SOU Citation1948) stressed this idea. However, in the wake of GERM, what was new was the discursive framing of this fundamental notion. Surrounding the discourse about teachers’ needs of continuing professional development (CPD) was now not only ideas about a research base on which to ground and from which to assess sound behaviour, but also formally articulated notions about a new reason for this foundation and new notions about where relevant content should be developed, in what kinds of relationships with whom.

The changes in the framing of discourse are clear in the Swedish government proposals for a national programme of CPD for teachers (The National Professional Program, U2021/03373) and its aim to enhance the quality of education and student knowledge results, as well as to make school professions more attractive (Minister of Education Press Release, June 2022 www.regeringen.se). First, by indirectly negating the existence of a research base, it frames the quality of education and student knowledge as directly linked to teachers’ (and other school professionals’) competence and professionalism and states that the more qualified (i.e. continually educated) teachers we have, the more qualified students there will be, which would also help raise the professional status of teachers and the performance of schools, both of which the program asserts are lacking due to the absence of research-based professionalism. As with the GERM school reforms, this idea about the absence of professional learning and development lacks empirical support. If anything, research suggests that there was once a strong research base for professional practice but that this has become eroded, following earlier GERM reforms in ITE (Beach and Bagley, Citation2012).

Similar national strategies for governing and shaping teacher development in line with GERM appear also in other countries, such as in for example Australia, where they have also been heavily criticised (Mockler Citation2022). Yet this has not stopped the flood of both governmental and private initiatives offering various forms of CPD for teachers (Wermke Citation2011, Forsberg and Wemke Citation2012, Langelotz Citation2017, Levinsson et al. Citation2022). So, our aim in this article is to explore the underpinning perspectives related to teachers’ professional learning and the newly emerged and expanding CPD market and discuss the possible consequences for teacher professionalism. We have used critical discourse analyses from data based on interviews with principals to accomplish our aims, supported also by an analysis of CPD invoices. Swedish school principals have the overall pedagogical responsibility in school, including sometimes over several small schools, and they are also responsible for following regulations and attaining goals related to teachers professional learning. We addressed the following research questions:

What kinds of professionalism do emerging discourses of CPD describe as desirable (and possible to develop) through the Swedish CPD market and

What theoretical perspectives underpin claims about CPD in in these discourses?

Background and research review

Professions, and in particular the teacher profession, have been discussed and problematised extensively both in the general debate and in social sciences over the last 60–70 years (Lloyd and Davis Citation2018). Teachers’ work has been described as an occupation or a semi-profession in comparison to classical professions like doctors or lawyers (e.g. Brante Citation2009) despite decades of political discourse from different governments and parliamentary propositions describing ambitions to further ‘intellectualize’ the professional content knowledge of and (thereby) further professionalise the Swedish teacher profession (Larsson and Sjöberg Citation2021).

One problem with notions like profession and professionalism is their shaping by vaguely defined underpinning ideologies and political interests (Brante Citation2009). They are non-definitive concepts that vary in relation to time and context; as a ‘boundary object’ (Larsson and Sjöberg Citation2021, p. 3, referring to Star & Grieshemer Citation1989). Various normative connotations are therefore underpinning professionalism ‘as something worth preserving and promoting in work and by and for workers’ (Evetts Citation2014, p. 34) instead of something that benefits from being questioned and challenged. Teaching and teachers’ work are for example seen as morally committed and ‘for the public good’ (Parsons Citation1951, Citation1968), and where ‘critical professionalism’ (Barnett Citation1997), and ‘civic professionalism’ (Sullivan Citation2005) are crucial. Englund and Solbrekke (Citation2015) argue, that teacher professionalism relates to teaching quality and the moral responsibility of teachers, whilst from a practice perspective, professionalism is about ‘practicing professionally’ as Macklin (Citation2009, p. 83) puts it. Macklin associate’s teacher professionalism with moral judgement about what is best to do. This is in line with what for example Mahon et al. (Citation2019) call praxis; teachers’ socially and politically informed moral and ethical actions that contribute to historical changes that aim to do ‘good’ in relation to the social, moral, and political purpose of education (see also Francisco et al. Citation2021). Questions like ‘In whose interests are we acting?’ as Kemmis and Smith (Citation2008, p. 3) put it, are crucial to enhance praxis and critical professionalism but often remain unasked questions (see also, Mahon et al. Citation2017). In relation to research, Englund and Solbrekke (Citation2015) claim that professionalism and, also the professionalisation of an occupation concern professional autonomy, ownership of knowledge and knowledge development, and condition what counts as quality within the professional field (cf. Wermke Citation2011, Cain Citation2015, Lambirth et al. Citation2019).

Englund and Solrekke’s perspective aligns well with the theoretical article in this special issue, where the authors emphasise ‘agency’ as crucial for professional learning and the teacher profession (Salo, Francisco and Olin, 2024/forthcoming this SI). The theoretical points of departure are in this sense normative. They constitute the moral and ethical dimensions of practice (cf. Englund and Solbrekke Citation2015) and professional autonomy within which to discuss ‘teacher agency’ and the impact on teaching that continued professional development can have.

Teacher autonomy is both an individual construct and a profession-wide one ‘that shapes the ways in which teachers are governed, regulated, trusted and respected…’ (Kennedy Citation2014, pp. 693–694). She argues further, that although specific CPD models might support teacher autonomy it is crucial to capture the broader picture of context and the underpinning perspectives on professionalism. Sachs (Citation2001) stresses the managerial and democratic discourses underpinning teacher professionalism. The managerial is one of them. It usually claims two things: first, that efficient management can solve any problem and second that any ‘practices which are appropriate for the conduct of private sector enterprises can also be applied to the public sector (p. 151, referring to Rees 1995). She continues:

The core of democratic professionalism is an emphasis on collaborative, cooperative action between teachers and other educational stakeholders. Preston (Citation1996) maintains that this approach is a strategy for industry development, skill development and work organization. According to Brennan (Citation1996) it suggests that the teacher has a wider responsibility than the single classroom and includes contributing to the school, the system, other students, the wider community, and collective responsibilities of teachers themselves as a group and the broader profession. (Sachs Citation2001, p. 153)

Evetts (Citation2014, p. 33) claims that much of the research on professionalism agrees that professions are essentially the knowledge-based category of service occupations and include a period of tertiary education together with some vocational training and working life experience. Hence, a professions’ specified knowledge, together with autonomy and responsibility, become the core criteria defining (teacher) professions, and continuing professional development becomes one of the key practices contributing with knowledge content to enhance professionalism. As Francisco et al. (Citation2021) put it:

We argue that the potential power of professional learning is in supporting and developing the capacity to question institutionalised habits or educational practices that may be in conflict with values, purpose and moral intentions, in order to create positive change. (Francisco et al. Citation2021)

The underpinning (normative) ideologies of CPD discourses, and the knowledge development offered become therefore of relevance to explore. CPD practices seem to be easily opened to unscientific economic entrepreneurialism interests and influence (e.g. Ideland et al. Citation2020, Norlund, Levinsson and Langelotz Citation2022), because of the lack of a strong, research-based scientific discourse of what professionalism entails generally, and not the least particularly in relation to so-called semi-professions (Gunnarsson et al. Citation2014). In the following, we will pay attention to specific circumstances regarding teachers’ professional learning in Sweden.

CPD organisation in Sweden

Teachers’ CPD is regulated in the School Law in Sweden, where it is the principal organiser of schools (called skolhuvudman in Swedish), regardless of whether they are municipal or independent, and thereafter, usually by delegation the school principal, who together with individual teachers themselves become responsible for assuring there are suitable quantities and kinds of professional learning opportunities. Current regulations specify some 104 hours each school year. Municipalities and/or individual schools organise CPD themselves and pay for commercial CPD providers but they also apply and compete for possibilities to get enrolled in state funded CPD programmes like the national Math Boosts (in Swedish ‘Matematiklyftet’).

Principals’ pedagogical leadership responsibilities are emphasised and governed by the authorities in Sweden (e.g. The School Inspection). This has applied effectively since the Municipalisation reform (Proposition, 1990/91:18), which entrusted principals with the responsibility to organise and lead the daily work in the school, whilst the government remained responsible for the national curriculum and the syllabus of the national subjects (Parding and Berg-Jansson Citation2017). The structure of leadership in this respect comprises a quite complicated architecture where principals are responsible by law for the quality of teaching in their school and putting CPD regulations into practice within a quasi-market context shaped concurrently by market and remnants of the previously dominant social-democratic welfare discourses frames (cf. Lundahl et al. Citation2013, Fjellman Citation2017). In this article, we are interested in the various discourses about teacher professionalism in Sweden and if/how they are manifested in principals’ talk about and constituting action relating to continuing professional development, and we have adopted a practice theory to explore this.

Theory and methodology

Research frequently interprets teachers’ professional development narrowly, as related to teachers’ actions (Evans Citation2015) or as policy. It is often context-specific, and it investigates CPD models and/or the effectiveness of CPD. A focus on individual teachers’ experiences of CPD predominates (Kennedy Citation2014), with a focus primarily on individual teachers as the unit of analysis, and studies that look at how the concept of professionalism can be mobilised to influence the profession, in relation to CPD, are much less evident (Kennedy Citation2014, p. 690). Because of this, Kennedy calls for more research and theory considering both the possible outcome of models of CPD and wider systemic patterns and perspectives on professionalism (ibid. p. 694), which is also the point of departure for the present article relating to the knowledge content and underlying perspectives informing CPD practices that (aim to) shape teacher professionalism.

Our theoretical departure is practice theory. Practices consist of what people say, what they do and how they relate to one another (e.g Kemmis and Grootenboer Citation2008). The ‘sayings-doings-relatings’ (Langelotz Citation2017, p. 27) hang together in specific projects or aims (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) and a practice like continuing professional development is historically, socially, materially, culturally, politically, economically, and discursively constrained and enabled (Kemmis Citation2009) through cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements [see e.g. Kemmis et al. (Citation2014); Salo et al. (Citation2024)).

We focus mainly on the ‘cultural-discursive arrangements’ in this article, and the ‘sayings’ in inter-subjective semantic space (e.g. Kemmis et al. Citation2014) when analysing CPD practices to try to identify and generate data to analyse the underpinning ideologies and logics that shape teacher professionalism. The underpinning ideologies traced in the ‘sayings’ in interviews, and in written content and model-descriptions of CPD and surrounding society represent not only cultural-discursive arrangements shaping CPD practices and teacher professionalism but are in this article also understood as ‘practices that systematically form the object of which they speak’ (Foucault Citation1986, p. 64).

Discourses form and re-form our understandings of certain phenomena in this sense, such as professional learning and professionalism (Gunnarsson et al. Citation2014) as an example of how language construes aspects of the social world in a way that transmits and naturalises ideologies, thus linking directly to patterns of injustice, discrimination, as well as political interest and power (Fairclough et al. Citation2011).

Data

The study in this article is part of a research project funded by the Swedish Research Council (ref.nr) following their ethical research principals. The empirical data for this article consist of (a) quantitative data on CPD models (invoices-data) and (b) interviews with principals. These data come from three municipalities in Sweden selected as broadly representative of the scope of variation in terms of municipal size and social composition of municipalities in Swedish society (see Levinsson et al. Citation2022).

To access the invoices, we contacted the financial departments at the education administration for elementary and secondary school (in Sweden secondary schools offer both theoretical-oriented and/or vocational-oriented education) in the three municipalities regarding the total number of teachers’ CPD invoices for the years of 2018 and 2019. The smallest (rural) municipality had only one school unit (K-9), so we chose to collect invoices from yet another year (2017) from this municipality to even out the number of invoices between the three municipalities (see Levinsson et al. Citation2022 for further descriptions).

For the interviews, we contacted principals in the three municipalities via email and phone-calls. We conducted ten (10) semi-structured interviews with fourteen (14) principals and vice-principals in this study. Principals from both elementary and secondary school in the three municipalities took part in the interviews (conducted 2022–2023). They were 40 minutes to one-and-a-half hours long. Three of them were conducted online (three principals and one head principal from the same secondary school participated in one of the on-line interviews) and seven were conducted face to face. All interviews were audio recoded and carried out by one of the authors (eight interviews of ten) and/or co-researchers in the project.

The interviews concerned teachers’ CPD and the principals’ own experiences and strategies when organising (and/or paying for) teachers CPD. We talked about CPD in general (with a focus on teachers’ CPD) and we asked some specific questions regarding the content and the models identified in the invoices at the specific school. In a few settings, the questions regarding specific invoices were a bit dated as a few principals were new at the actual school. However, they were all aware of the ‘bigger picture’ and the CPD history of their school.

Analysis

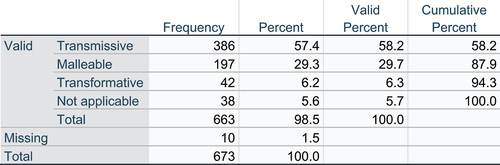

We carried out the analyses of the different empirical material in several steps. Six-hundred and sixty-three (of 981 in total, including other educator roles such as principals) invoices concerned only teachers’ CPD and we based the final data set of this article on these invoices. The coding phase built on the extraction of information from the total set of invoices and on entering data into an SPSS program file consisting of a multitude of variables. Some variables were deductively set based on previous research or theoretical foundations such as Kennedy’s (Citation2014) categorisation of purpose of CPD-model, while others were set inductively (new patterns and phenomena emerged during the processing, for a more thorough description see Levinsson et al. Citation2022). The theoretical framework of CPD-models and their purposes, developed by Aileen Kennedy (Citation2014), was part of the analyses. (see below)

Table 1. Spectrum of CPD models (Kennedy Citation2014, p. 693).

The analysis of the interviews involved 1) several occasions of listening to the recordings, with the research questions in mind. Further, to avoid ‘cherry-picking’ (i.e. finding what we were expecting [Wodak and Meyer Citation2009]), we have also 2) transcribed the interviews using the transcription tool Word Online, to be able to carefully 3) read through the transcripts to double check our first analyses based on listening of the audio-recordings. 4) We have made use of previous results regarding research on ideologies shaping discourses shaping teacher professionalism and previous results from research on the knowledge content offered on the Swedish CPD market (found in the ‘Invoice-project’ [Levinsson et al. Citation2022]) when making our analyses. Thus, the process has been theory-driven, adopting a critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Fairclough et al. Citation2011) describing, interpreting, and explaining combined with concepts from the theory of practice.

We aimed to ensure that underpinning ideas and concepts were not only representative for one of the principals/municipalities. Hence, the quotes in the Results section are representative for all schools. To make sure that the schools and principals remained anonymised in this paper we have not revealed specific characteristics (e.g. school form, municipality etc.).

Results

All the principals, i.e. head of the school, stress the importance of their responsibilities to organise (govern) teachers’ CPD to increase school development. This is mediated through the ‘head teachers’/’first teacher’ i.e. ‘extra skilled teachers’ (in Swedish: FörstelärareFootnote1) often with a position within the management structure. Teachers’ CPD is described in relation to enhanced goal fulfilment (for students) and the ‘systematic quality work’ (in Swedish: Systematiskt kvalitetsarbete [SKA]).

Transmissive models, where teachers ‘consume’ knowledge, dominate the practices of CPD purshased from providers in the CPD market. The knowledge content found in the invoice data is dominated by a strong special educational needs discourse. The main results show that the underpinning perspective on teacher professionalism in relation to CPD in Sweden mainly reflects a strong managerial discourse (Sachs Citation2001) in the sense that the organisations’ development and performative goals are prioritised and aligned to teachers professional learning. Altogether, the practices of CPD seem to discursively shape teacher professionalism and position teachers as Collegial consumers and/or Intermediaries.

We will elaborate on these professional positions and the underpinning ideologies (discourses) in the Discussion section. First, we will present more detailed findings in the two following sections: Knowledge content and CPD models.

Knowledge content

The predominant CPD content revealed in the invoices comes from two domains: 1) special-education and 2) subject-specific didactics mainly in mathematics and literacy often related to students’ learning difficulties. The third most common category, School Development, includes both social activities to strengthen the staff community (like bowling, dinners etc.) and activities like ‘collegial learning’ where for example head teachers/first teachers are responsible (together with the principal) to organise the CPD in the local school. This category represents the highest cost as it often reaches out to all teachers in one unit (the other invoices mostly concern costs for one, or a smaller group of teachers participating in CPD) (see Levinsson et al. Citation2022). In the principal interviews, the CPD content mentioned most frequently concerns issues related to general school development. Sometimes this CPD comes with a financial transaction recorded in the invoices but this CPD is most commonly financially ‘invisible’ as it is organised and run within the school or the municipality.

Content like assessment, implementing new curricula, preventive and health-promoting student health work, classroom management or study counselling are frequent in the local CPD practices for teachers as is ‘Language and Knowledge Developmental Work Methods’ (In Swedish: Språk- och kunskapsutvecklande arbetssätt, [SKUA]). The latter is CPD content proposed by the Swedish National Agency for Education (and/or the municipality). The same content is proposed to all the teachers in the local school (and often in the municipality).

This more general CPD content is problematised by the principals and they seem to be caught between the teachers wishes, the municipality/national organisers demands and their own opinions of what is needed. In the following quotation, the principal talks about the CPD content regarding Language and Knowledge Developmental Work Methods, imposed by the municipality in collaboration with the Agency of Education and universities due to the low school performance.Footnote2 The principal argues that it might be difficult to again engage the teachers in another CPD imposed from ‘above’ (i.e. a mandatory municipality initiative),and that the teachers wish to develop subject specific knowledge:

They [the teachers] think it has been good, the content and such… it has been going on for three years but, will there now be another investment… with the same … or should we start over… they have liked it and … they have had meetings every week and worked on it and I think it has been a great commitment. When you talk more generally with them (the teachers), my experience is that they miss… as well as they think it becomes too general. They want skills development that targets their subjects. The math teachers want a boost in this with someone who is really, good at math, like… meet and listen to them, and language and crafts (teachers) want theirs… When you must carry out general CPD, it often gets a bit blurred (Principal interview January 2023, authors’ translation).

Another suggested content for CPD, mentioned by the principals, concerns how to conduct, and participate in ‘collegial learning’. One principal explicitly mentioned how the teachers (had to) develop their abilities to lead collegial conversations:

Before the pandemic, I trained all my team leaders in something called ’Leading Collegial Learning’ from the Swedish National Agency for Education. They participated in that course as their CPD, with conversation theories and such./ … /so, I did my principal training and asked ’Do I see any collegial learning? Do I see any seeds?’/ … /It is all about collaboration … and the method, and that you can bring in research in small parts also to raise the gaze (Interview school principal Oct 2022, authors’ translation).

All the principals participating in the interviews – no matter municipality nor school form – stress the importance of collegial learning/mentoring. In the quotation above the mandatory education for principals is mentioned. The quote visualises how strong discourses around teacher collaboration travel between educational practices such as the University (offering principal training courses) and the National Agency (offering teacher CPD) (cf. Wilkinson et al. Citation2013).

‘Small portions’ of research is also mentioned as an important part of the CPD knowledge content. However, the importance of research-based knowledge is only mentioned when we interviewers brought it up as an issue. In the following quote the principal talks about research-based literature as a bit problematic for some of the teachers coming from another professional background such as builders or hairdressers (i.e. vocational teachers).

We help the teachers to bring in an [academic] culture because even if you have never done it [taking part of research-based knowledge/literature], it should be like you have always done it// … you might not want to read a whole book if you don’t have [an academic] culture and take courses in your free time. Then maybe you should have an article to begin with, to understand the system so that I can see my own practice based on what someone else has said (Interview school principal Oct 2022, authors’ translation).

A majority of the principals (in eight of ten schools) talk in this kind of way about research-based knowledge as something that has to be treated in an ‘easier’ or more ‘available’ way when presented for the teachers (no matter the teachers’ professional background or experiences). Either the research can be presented by external lecturers, or by the head teachers to make it more attractive and/or available for the teachers. The principals argue that the CPD knowledge (i.e. research-based knowledge) must be directly transferable into the classroom practices. A few of the principals also seem sceptical of the research-based value (other than as a way of financing development work) as the following quote shows:

Kent [a CPD provider] uses a lot of research, but research and proven experience should go hand in hand… If you conduct research at five different schools, you will get different results…/ … /received several million to develop the recess programme… If we apply for money and can link it to research, we get funding more easily… it’s important to be in the right place (Interview school principal March 2023, authors’ translation).

A few of the principals/vice-principals from two different school settings (one primary and one secondary school, two different municipalities) emphasise however, that their staff ask for well-educated lecturers/CPD contributors and research-based knowledge content. If the teachers don’t get that they will ‘throw out’ the contributors/contribution as one of the principals stated:

There must be a fairly, high academic standard on what we bring in because our teachers are of a high academic standard and if we were to bring in something that has no basis in it then it would just be thrown out right away and that … It’s nice that the teachers are so critical. I have been…I have been involved when … First teachers have previously also been involved … who may not…have had such a high academic standard and it has, yes it has…there will be no positive evaluations of it./ … /they are critical, and it is good that they are(Interview school principal September 2022, authors’ translation).

The models used for CPD differ between the data sources (invoices and interviews) as following descriptions will show.

Models and the organisation of CPD

The most frequent CPD model identified in the invoices falls into what Kennedy (Citation2014) categorises as Transmissive. As shows, single lectures by ‘experts’ predominate the costs found in the invoices.

Figure 1. Percentage of CPD models found in the invoices based on Kennedy’s (Citation2014) categorisation.

To gain CPD through an external ‘expert’ (Transmissive model) is also described by several of the principals as something that teachers find desirable. This wish is often denied, usually due to costs (i.e. material-economic constraints). However, the principals talk mostly about how they (or the municipality organiser) have organised teachers’ CPD using various ‘collegial learning models’. These models dominate teachers’ CPD according to the principals. These models are categorised as Malleable (and sometimes Transformative) in Kennedy’s (Citation2014) framework. In the following quote, a principal describes how he/she as a former head teacher worked closely with the management and developed a ‘collegial learning model’ inspired by the National Agency’s models.

So, it is the school management … we came up with a method that we no longer use. But it started with us having to look at this formative assessment … there was a big joint lecture that actually the whole municipality had. And we were given a book and such to read/…/Somewhat reflect what the Swedish National Agency of Education had when you had Maths lift and Swedish lift and all that… there is a film that was… well, you would read something between classes and then when you were a pre-primary teacher like I actually was then, then you had to go with the school management and so you had… you prepared together and we had different Head teachers in different subjects and gave each other tips./ … /and then we ran it with different types of orientations for two years, actually based on the book you can say … (Interview with school principal, September 2022, authors’ translation).

There are various ways of organising ‘collegial learning groups’ of teachers. One way is through a so-called ‘working team’ where teachers with different subject knowledge, teaching the same students, are gathered for CPD. Parallel groups are labelled as ‘subject teams’ in which teachers with the same subject (e.g. maths teachers) are encouraged to undertake professional development. The teachers are often organised in several group constellations where collegial learning (CPD) is supposed to happen. The head teachers/first teachers in the local schools are involved in the organisation, planning and implementation of CPD. There are also municipality and/or nationally organised ‘collegial learning groups’ in which ‘key teachers’ take part. The ‘key teachers’ are often not the same persons as the head teachers. Hence, another group of teachers, besides the head teachers, is also pointed out as intermediaries between the municipality and the local schools.

The principals describe how the head teachers sometimes express frustration with their colleagues because of their lack of performing the (new?) ideas in their classrooms and acting as agreed on during the CPD. The principals talk about how important it is that the content offered in CPD matches their plans (such as school development policies, analyses based in evaluations etc.) to achieve goal fulfilments for all students.

One of the principals described how they (the school and municipality organiser) had to pay a fine to the School Inspection (because of low school performance and for not fulfilling their tasks) and therefore had the possibility to get enrolled in the SBS program (see above/footnote 1). Hence, an extensive pot of money for CPD became available and the school could engage ‘external partners’ for lectures and CPD collaborations. The principal emphasised how much more convenient it is to collaborate with private actors (and/or to book university lecturers outside the university system). These collaborations are supported by the Agency of Education and the municipality organiser. As pointed out earlier, the Agency works with both universities and private CPD providers, but several principals stressed the difficulties of collaborating with universities, noting that it is hard to book a researcher/lecturer from the university and that one must book long in advance.

To summarise: the content and the models of CPD organised both in the local schools and the CPD market seems underpinned by a managerial logic heavily influenced by market discourses, that discursively shape teacher professionalism and position teachers as (Collegial) Consumers and/or Intermediaries of knowledge. This will be further elaborated on in the following discussion.

Discussion

Teachers continuing professional development (CPD) and teacher professionalism are of growing financial interest both in Sweden and internationally, and of course also of political and ideological interest. Kemmis et al (Citation2104) argue that three analytically separable arrangements enable and constrain practices like teachers’ learning: the cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements i.e. the practice architectures (see also Salo et al. Citation2024). As an example, the cumulative CPD discourse is partly a result of global competition (e.g. international student assessments like PISA, PIRLS, TIMSS), where countries are competing on a global knowledge market based on the Global Economic Reform Movement (GERM) notional belief (Sahlberg Citation2011), that such competitiveness can promote an increase in national and global economies if successful (cf. Kennedy Citation2014). In Sweden, commercial CPD providers take a commanding market position that helps to generate a significant source of profit potential in the light of these strong international discourses around teachers’ need for professional learning and development. Hence, cultural-discursive (e.g., the global CPD discourses and ideas concerning teachers’ need for development), material-economic (e.,g., the global knowledge market and commercial CPD providers), and social-political arrangements (e.g., the collaboration between the State and commercial CPD providers) condition practices of teachers professional learning. The arrangements intertwine, however.

In this article, the main analytical focus has been on parts of the cultural-discursive arrangements: we have analysed discourses that shape and are shaped by ideologies in relation to teachers’ continuing professional development practices. Shaping professional discourse and practice by ideological means is well known from research on professional discourse (Gunnarsson et al. Citation2014). Kennedy (Citation2014) stresses the importance of interrogating the underpinning perspectives on teacher professionalism when researching professional development/learning and in this article, we followed the two discourses she points out referring to Sachs (Citation2001). These competing discourses are managerial versus democratic professionalism. Managerial professionalism is imposed, contrived, reinforced by employing authorities and has an emphasis on accountability and effectiveness (Sachs Citation2001, p. 149), whilst Democratic professionalism emerges from the profession itself.

Underpinning perspectives

In the present study, the content focus of professionalism discourse is a managerialist and contrived one, relating largely to the teachers’ (lack of) general teaching knowledge (e.g. classroom management) and/or the pupils’ learning difficulties or health-related issues, which the discourse casts as needing correction. The dominant knowledge content found in the invoices reflects this moreover. It focuses on students with special educational needs (SEN), which is a strong global educational discourse (see also Levinsson et al., Citation2022; Tomlinson, Citation2012). The dominant discourse is one that drives forward a model of CPD involving restricted professional learning wherein private stakeholders offer simplified solutions to complex problems. Currently contrived largely around/by a special educational needs (SEN) discourse (c.f, Langelotz et al., Citation2022; Levinsson et al. Citation2022), as Brint (Citation1994) pointed out, teachers’ understanding of their professional needs and the complexity of teaching are pushed away by cognitive and technical dimensions where an individual-oriented focus is dominating.

However, the interview data has also suggested the presence of a strong collaboration discourse connected to teacher leaning and development partly underpinned by democratic ideologies of professionalism (cf. Sachs Citation2001, Langelotz Citation2014). Here, the principals emphasised the need for teachers to be engaged in their own knowledge development and the importance that teachers learn and develop together, and they also stressed the significance of teachers’ own questions and ideas and that they don’t want to interfere in the CPD (i.e. ‘collegial learning’). Previous research shows how the idea of ‘collegial learning’ (in the form of peer group mentoring) can be traced to Nordic ideals of ‘folkbildung’ (in Swedish: folkbildning) and study circles (Langelotz and Rönnerman Citation2014). The ‘collegial’ models build on the idea of the profession (teachers) as knowledgeable and autonomous and might enhance a critical professionalism (cf. Boylan et al. Citation2023). Yet, this ‘collegial content’ seems to be deceptively packaged as it is strongly governed by the school management and the municipality organiser. ‘collegial learning’ is not problematised or defined (more than as ‘collaboration’ or as the Agency models). Langelotz (Citation2017, p. 58) argues that collegial learning sometimes represents an imaginary hybrid of a transformative model (cf. Kennedy Citation2014) and that several collegial models lack empirical support. Thus, concerning teachers as Collegial consumers and intermediaries, in this study it seems like ‘collegial learning’ is used to govern teachers rather than to embrace the empowering craft that collegiality can enhance (see for example Lambirth et al. Citation2019, Boylan et al. Citation2023). Instead of positioning them as collegial leaders, teachers are ascribed a role of collegial consumers of CPD and as a profession that needs to ‘learn how to work collaboratively’ led by head teachers or other colleagues.

There is an unproblematized correlation between teachers’ professional learning, school development and student goal fulfilment found in this studyprincipals talked about these three in the same breath. By this correlation CPD becomes part of an accountability and effectiveness discourse (cf. Englund and Solbrekke, Citation2015; Sachs Citation2001). The principals emphasised how the municipal organiser, organises (and governs) parts of teacher CPD (often in collaboration with national authorities such as the Agency of Education, the Agency of Special Education, or the School Inspectorate) influences and steers the local school’s initiatives. All the principals express that if only the teachers (and the school/management organisation) do the right things i.e. organise and/or take part in collaborative CPD, the goal fulfilments for all students will be achieved. Another example of the managerialist perspective underpinning professional learning, is the local time consuming organization around teacher learning with several groups of teachers on different levels involved in the implementation of imposed CPD content. Hence, another (or combined) position of teachers is discursively constructed: as Intermediaries. The head teachers are often used to implement CPD content, through ‘collegial learning’ imposed by the management/municipality/national authorities. This intermediaries position is also embedded in material-economic arrangements, two of the principals argued that the extended responsibility for the head teachers, helps them justify their titles (and higher salary).

The majority of the principals in this study do not seem to recognise the agency of teacher profession or teachers as highly educated academics (cf. Salo et al. Citation2024). The global discourse on (and the Swedish State ambition of) a research-and experienced-based education is touched upon prompted by us (interviewers). Some of the principals expressed scepticism of the research-based knowledge as too far from the ‘practical work’ in the classroom and mistrust of the teachers’ engagement (and capacity) in research literature. The principals stressed at the same time, the importance of reading literature (although not ‘too much’ nor ‘too complicated’ but ‘based in research’) together in ‘collegial learning/mentoring teams’. Research-based knowledge seems not to be understood as something that teachers themselves could perform or contribute to (this is not mentioned or reflected upon at all). Professional learning, enhancing the ‘capacity to question institutionalised habits or educational practices that may be in conflict with values, purpose and moral intentions, in order to create positive change’ (Francisco et al. Citation2021). seems to be limited to say the least.

There seems to be a clear negative side to the patterns we identify. One of them is that (seen from the outside through invoice data), CPD programs and courses purchased at municipal level do not seem to address the professional needs of the teacher collective and teacher agency (cf. Salo et al. Citation2024 this SI). Instead, it seems to frame, position, and even exploit teachers as ‘doers’ who are responsible only for communicating official school knowledge and assessing pupil performances in relation to a narrow range of outcomes, rather than collectively professional responsible thinkers and co-developers of education who need an abstract, powerful, theoretical knowledge for the realisation of a national school project in the national interest (Nilsson-Lindström and Beach Citation2015). Developments thus may risk undermining the foundations for professional judgement (cf. Macklin Citation2009, Mahon et al. Citation2019) instead of scaffolding their learning, and undermining teacher professionalism based on professional autonomy (cf. Englund and Solbrekke Citation2015, Salo et al. Citation2024) through the marginalisation of critically and theoretically informed professional knowledge. Both the CPD invoices and the interviews with school principals carry evidence of this.

The practice of teachers’ professional learning is clearly conditioned by discourses (i.e. cultural-discursive arrangements) but they also reflect and obtain form and content through material-economic (i.e. economy) and the social-political arrangements (e.g., loyalties between authorities and private CPD providers) as well. Indeed, market discourses (and material-economic arrangements like finances) combined with managerial logic underpin the practices of CPD and the shaping of teacher professionalism. None of the principals problematise (or criticise) the surrounding society as unjust or the built-in quasi market as unfair and based on an economic logic. Sachs (Citation2001) argues that there are competing discourses – we would like to claim that the discourses underpinning teachers’ professional learning in the Swedish educational market also seem to nourish each other; a managerial logic also infiltrates democratically underpinned CPD content and models like ‘collegial learning’.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council under grant number 2019-03828. We would like to thank Magnus Levinsson and Anita Norlund, University of Borås, for their contribution to data production and early discussions. We are grateful to the principals who shared their thoughts and stories.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Another educational reform (SFS 2013:70) in the wake of GERM in Sweden.

2. The collaboration between municipality organisers, local schools, universities, and the Agency of Education is called ‘Collaboration for Best School’ (In Swedish: Samverkan för Bästa Skola [SBS]). The Agency offer municipalities with low performance achievement to participate in the collaboration (see Skolverket.se). This kind of united action has been questioned and described as a ‘school development industry’ (Håkansson and Rönnström Citation2022)

References

- Ball, S., Juneman, C., and Santori, D., 2017. Edu.Net: globalisation and education policy mobility. London; New York: Routledge.

- Barnett, R., 1997. Higher education: a critical business. Buckingham: SRHE & Open University press.

- Beach, D., 2010. Neoliberal Restructuring in Education and Health Professions in Europe: questions of global class and gender. Current sociology, 58 (4), 551–569. doi:10.1177/0011392110367998.

- Beach, D. and Bagley, C.A., 2012. The weakening role of education studies and the re-traditionalisation of Swedish teacher education. Oxford Review of Education, 38 (3), 287–303. doi:10.1080/03054985.2012.692054.

- Boylan, M., et al., 2023. Re-imagining transformative professional learning for critical teacher professionalism: a conceptual review. Professional development in education, 49 (4), 651–669. doi:10.1080/19415257.2022.2162566.

- Brante T., 2009. Vetenskap och profession. Högskolan i Borås.

- Brennan, M., 1996. Multiple professionalism for Australian teachers in the information age? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York.

- Brint, S., 1994. In an age of experts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cain, T., 2015. Teachers’ engagement with published research: addressing the knowledge problem. The curriculum journal, 26(3), 488–509, [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®]. doi:10.1080/09585176.2015.1020820.

- Englund, T. and Solbrekke, T.D., 2015. Om innebörder i lärarprofessionalism. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 20 (3–4), 168–194.

- Englund, T. and Solbrekke, T.D., 2015. Om innebörder i lärarprofessionalism. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 20 (3–4), 168–194.

- Evans, L., 2015. Professionalism and professional development: what research fields look like today - and what tomorrow should bring. Hillary Place Papers, 2.

- Evetts, J., 2014. The concept of professionalism: professional work, professional practice and learning. In: S. Billett, C. Harteis, and H. Gruber, eds. International Handbook of Research in professional and Practice-based Learning. Springer International Handbooks of Education. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8_2.

- Fairclough, N., Mulderrig, J., and Wodak, R., 2011. Critical discourse analysis. In: T.A. van Dijk, ed. Discourse studies. A multidisciplinary introduction. Sage, 357–378.

- Fjellman, A.-M., 2017. Differentiering genom reglerad marknadsanpassning: Uppkomsten av en regional skolmarknad [Differentiation through regulated market adjustment: The emergence of a regional school market]. Utbildning & Demokrati, 6 (1), 107–132. doi:10.48059/uod.v26i1.1074.

- Forsberg, E. and Wemke, W., 2012. Knowledge sources and autonomy: German and Swedish teachers’ continuing professional development of assessment knowledge. Professional development in education, 38 (5), 741–758. doi:10.1080/19415257.2012.694369.

- Foucault, M., 1986. The archaeology of knowledge. Great Britain: Tavistock Publications.

- Francisco, S., Forssten Seiser, A., and Grice, G., 2021. Professional learning that enables the development of critical praxis. Professional development in education, 49 (5), 938–952. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1879228.

- Gunnarsson, B.L., Linell, P., and Nordberg, B., 2014. The construction of professional discourse. London: Routledge.

- Håkansson, J. and Rönnström, N., 2022. Samverkan för bästa skola – skolförbättring som politiskt styrd nationell angelägenhet genom samverkan och forskarmedverkan. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 26 (1), 7–14. ISSN 1401–6788: doi:10.15626/pfs26.01.01.

- Ideland, M., Jobér, A., and Axelsson, T., 2020. Problem solved! How eduprenuers enact school crises as business possibilities. European Educational Research, 20 (1), 83–101. doi:10.1177/1474904120952978.

- Kemmis, S., 2009. Understanding professional practice: a synoptic framework in. In: S. Kemmis, ed. Understanding and researching professional practice. Brill, 19–38. doi:10.1163/9789087907327_003.

- Kemmis, S, et al., 2014. Changing education, changing practices. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S. and Grootenboer, P., 2008. Situating practice in praxis. In: S. Kemmis and T.J. Smith, eds. Enabling praxis. Challenges for education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 37–62.

- Kemmis, S. and Smith, T.J., 2008. Praxis and praxis development. In: S. Kemmis and T.J. Smith, eds. Enabling praxis: challenges for education. Rotterdam: Sense, 3–13.

- Kennedy, A., 2014. Understanding continuing professional development (CPD): the need for theory to impact on policy and practice. Professional development in education, 40 (5), 688–697. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.955122.

- Lambirth, A., et al., 2019. Teacher-led professional development through a model of action research, collaboration and facilitation. Professional development in education, 47(5), 815–833, Taylor & Francis Online. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1685565.

- Langelotz, L., 2014. Vad gör en skicklig lärare? En studie om kollegialt lärande som utvecklingspraktik. [What ’makes’ a good teacher? A study on collegial learning as a development practice.], PhD theses, Göteborgs universitet. ACTA

- Langelotz, L., 2017. Kollegialt lärande i praktiken – kompetensutveckling eller kollegial korrigering? [collegial learning in practice – continuing professional development or collegial correction?]. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Langelotz, L., Norlund, A. and Levinsson, M. (2022). Continuing professional development - a threat to Teacher professionalism. Paper presented at annual meeting of American Educational Reserach Assocation (AERA), San Diego.

- Langelotz, L. and Rönnerman, K., 2014. The practice of peer group mentoring – traces of global changes and regional traditions. In: K. Rönnerman and P. Salo, eds. Lost in practice: transforming nordic educational action research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 75–95.

- Larsson, C. and Sjöberg, L., 2021. Academized or deprofessionalized? – policy discourses of teacher professionalism in relation to research-based education. Nordic journal of studies in educational policy, 7 (1), 3–15. doi:10.1080/20020317.2021.1877448.

- LevinssonM., Norlund A., and Langelotz L., 2022. Innehåll och pedagogiska diskurser på lärares kompetensutvecklingsmarknad - en studie av insatser som genererar fakturor. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 28 (4), 7–37. doi:10.15626/pfs28.04.01.

- Lloyd, M. and Davis, J.P., 2018. Beyond performativity: a pragmatic model of teacher professional learning. Professional development in education, 44 (1), 92–106. doi:10.1080/19415257.2017.1398181.

- Lundahl, L., et al., 2013. Educational marketization the Swedish way. Education inquiry, 4 (3), 22620. doi:10.3402/edui.v4i3.22620.

- Macklin, R., 2009. Moral judgement and practical reasoning in professional practice. In: R. Macklin, ed. Understanding and researching professional practiceVol. 8, 83–99. Publisher: Brill E-Book ISBN:9789 087 907 327. doi:10.1163/9789087907327_007.

- Mahon, K., et al., 2017. Introduction: practice theory and the theory of practice architectures. In: K. Mahon, S. Francisco, and S. Kemmis, eds. Exploring education and professional practice. Through the Lens of practice Architectures. Singapore: Springer, 1–30.

- Mahon, K., Heikkinen, H.L.T., and Huttunen, R., 2019. Critical educational praxis in university ecosystems: enablers and constraints. Culture, pedagogy and society, 27 (3), 463–480. doi:10.1080/14681366.2018.1522663.

- Mockler, N., 2022. Teacher professional learning under audit: reconfiguring practice in an age of standards. Professional development in education, 48 (1), 166–180. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1720779.

- Nilsson-Lindström, M. and Beach, D., 2015. Changes in teacher education in Sweden in the neo-liberal age: toward an occupation in itself or a profession for itself? Education inquiry, 6 (3), 241–258. doi:10.3402/edui.v6.27020.

- Parding, C. and Berg-Jansson, 2017. Conditions for workplace learning in professional work discrepancies between occupational and organisational values. Journal of workplace learning, 30 (2), 108–120. doi:10.1108/JWL-03-2017-0023.

- Parsons, T., 1951. The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

- Parsons, T., 1968. Professions. In: D. L. Sills, and R. K. Merton eds. International Encyclopedia of the SocialSciences. New York: The Free Press and MacMillan, Vol. 12, 536–547.

- Preston, B., 1996. Award restructuring: a Catalyst In the Evolution of Teacher Professionalism. In: T. Seddon, ed. Pay, Professionalism and Politics. Melbourne: ACER.

- Prop. 1991/92:95., 1992. Regeringens proposition 1991/92:95 om valfrihet och fristaende skolor.

- Prop. 1992/93:230., 1993. Regeringens proposition Valfrihet i skolan.

- Sachs, J., 2001. Teacher professional identity: competing discourses, competing outcomes. Journal of education policy, 16 (2), 149–161. doi:10.1080/02680930116819.

- Sahlberg, P., 2011. The fourth way of Finland. Journal of educational change, 12 (2), 173–185. doi:10.1007/s10833-011-9157-y.

- Sahlberg, P., 2023. Trends in global education reform since the 1990 s: looking for the right way. International Journal of Educational Development, 98, 102748. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102748

- Salo, P., Franscisco, S., and Olin Almqvist, A., 2024. Understanding professional learning in and for practice. Professional development in education, 50 (3).

- Skog-Östlin, K., 2005. Att bryta ny mark: Kvinnors bruk av läroverslärarutbildning omkring 1900. Örebro: Pedagogiska institutionen.

- SOU 1948:27, 1948. 1946 års skolkommissions betänkande med förslag till riktlinjer för det svenska skolväsendets utveckling. Stockholm: Statens offentliga utredningar.

- Star, S.and Grieshemer, J.R. 1989. Ecology, ‘translations’and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social studies of science, 19 (3), 387–420. doi:10.1177/030631289019003001.

- Sullivan, W., 2005. Work and integrity. The crisis and promise of professionalism in America. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers Inc.

- Tatto, M.T., 2006. Education reform and the global regulation of teachers’ education, development and work: a cross-cultural analysis. International Journal of Educational Research, 45 (4–5), 231–241. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2007.02.003.

- Tomlinson, S., 2012. The irresistible rise of the SEN industry. Oxford Review of Education, 38 (3), 267–286.

- Wermke, W., 2011. Continuing professional development in context: teachers’ continuing professional development culture in Germany and Sweden. Professional development in education, 37 (5), 665–683. doi:10.1080/19415257.2010.533573.

- Wilkinson, J., et al., 2013. Understanding leading as travelling practices. School leadership & management, 33 (3), 224–239. doi:10.1080/13632434.2013.773886.

- Wodak, R. and Meyer, M., 2009. Critical discourse analysis: history, agenda, theory and methodology. In: R. Wodak and M. Meyer eds. Methods for critical discourse analysis. Sage Publications Ltd, 1–33.