Abstract

The main purpose of this article is to introduce the Social Enterprise Model Canvas (SEMC), a Business Model Canvas (BMC) conceived for designing the organizational settings of social enterprises, for resolving the mission measurement paradox, and for meeting the strategy, legitimacy and governance challenges. The SEMC and the analysis that explains its features are of interest to academics concerned with the study of social entrepreneurship because they offer a new analytical tool that is particularly useful for untangling and comparing different forms of social enterprises. Also, it is of interest to social entrepreneurs, because the SEMC is a platform that can be used to prevent ‘mission drifts’ that might result from problems emerging from the mismanagement of such challenges. The arguments presented are grounded on scientific literature from multiple disciplines and fields, on a critical review of the BMC, and on a case study. The main features of SEMC that makes it an alternative to the BMC are attention to social value and building blocks that take into consideration non-targeted stakeholders, principles of governance, the involvement of customers and targeted beneficiaries, mission values, short-term objectives, impact and output measures.

Introduction

This article introduces the Social Enterprise Model Canvas (SEMC), a conceptual instrument that supports researchers and social entrepreneurs for understanding or designing the structure of organizations dedicated to the pursuit of social goals, by building on a literature review of writings providing contributions to knowledge in a variety of social sciences fields. These include sociology, organizational studies, management, business ethics and research focussed on the nonprofit sector, social enterprises and entrepreneurship, social responsibility, social innovation, public administration and business models. Like the popular Business Model Canvas (BMC) of Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010) used as a blueprint, the SEMC uses building blocks, which allow for the identification of key elements and the analysis of their relationships. However, alternative to the BMC, the building blocks of the SEMC are designed to facilitate the framing and solution of the most important challenges faced by these hybrid organizations.

The SEMC and the analysis that explains its features contained in this article are of interest to academics concerned with the study of social entrepreneurship because they offer a new analytical tool that is particularly useful for untangling and comparing different forms of social enterprises (SEs). Also, it is of interest to social entrepreneurs because SEMC is a platform that can be used to overcome the ‘mission measurement paradox’ (Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011) and to improve communication about a SE, its features and strategy, in order to gain institutional legitimacy and to prevent a ‘mission drift’ (as defined in Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014). In order to introduce this conceptual tool and its rationale, this article is structured as follows: first, the article explains the importance of using business models for the analysis of organizations, but also the conceptual changes that are required to adapt business models to the analysis of SEs. Particularly important for this purpose are reflections about the different understandings of the concepts of value and values. Second, the article briefly focuses on the BMC, its success, and how the original authors propose to use it for the understanding of SEs. Third, the article introduces and explains the four challenges identified here as important issues faced by SEs that the SEMC contributes to unravel, also thanks to explanatory support provided by the case study. Fourth, the article introduces the principles governing the design of the SEMC or its (short) ‘ontology’, the conceptualization of the elements, relationship, vocabulary and semantics (Osterwalder Citation2004). Finally, the SEMC is presented and its building blocks briefly explained, followed by the article’s conclusions.

The case study that illustrates the use of the SEMC concerns the Master’s programme in Digital Communication Leadership (DCLead). The source of information about this programme is the author. DCLead is a joint Master’s programme delivered by the University of Salzburg in Austria, the Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium, Aalborg University in Copenhagen in Denmark, and nine other associated partners, four of which are industry partners, and five other universities outside of Europe. In 2015 DCLead was selected to become an Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree (EMJMD) by the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA) of the European Union (EU), within the framework of the Erasmus + programme.1 The funding of the EU allows for the selection of talented candidates from different parts of the world regardless of their socio-economic background because it provides scholarships covering participation, travelling and installation costs, and a monthly stipend. Due to the large appeal of Erasmus + funding opportunities and the consequent, intense competition from consortia from all disciplines attempting to be selected for funding, EMJMD programmes are considered elite Master’s programmes in the EU.

Furthermore, DCLead and other EMJMD programmes are social enterprises, first, because they are governed by specifically designed management boards composed of ‘social engineers’ (Zahra et al. Citation2009), i.e. the representatives of the institutions of the consortium, which create a new social system addressing existing social needs (see Florin and Schmidt Citation2011), by creating a new educational programme for candidates that aim at obtaining the qualifications that the programme offers, regardless of their socio-economic status. Second, DCLead is a social enterprise because of its potential for delivering social innovations (see Nandan, London, and Bent-Goodley Citation2015; Perrini and Vurro Citation2006; Sinkovics, Sinkovics, and Yamin Citation2014). In fact, to be selected, EMJMDs are expected to propose new educational programmes and to introduce new mechanisms that enable the delivery of degrees jointly awarded by institutions from different countries, and therefore, to effectively go beyond established practices. Third, although they are non-profit organizations, EMJMDs are expected to generate an income from the partaking of self-funding students, which are participants that are not the recipients of the EU scholarship and pay the contribution costs from their own means or from other types of scholarships. All EMJMDs charge participation costs regardless of whether they are formed by higher education institutions from countries where students pay fees or not. The income generated from these students’ partly finances, the overhead that is caused by inviting guest lecturers, hiring extra administrative employees and organizing extra and joint activities with the partners of the consortium. More importantly, however, EMJMDs are expected to become financially sustainable after a period of five or six years or longer, if a programme is selected for more than one contract. Hence, it is equally important for EMJMDs to select talented students regardless of their socio-economic background and create success stories that will make the programme more attractive and to find and select students that meet the requirements and have the financial means to contribute to its costs. Moreover, gradually, the share of self-funding students is supposed to increase, so that the funding generated by their participation costs replaces the funding received from scholarship students, which is phased out. Therefore, the application of the SEMC to the activities and organizational settings of DCLead is considered suitable because it has a social mission, it participates in the marketplaces for educational programmes, and also faces the challenges identified below as important for SEs. Moreover, such a case study might be of interest to academics from different disciplines, particularly in the European Union, which are involved in designing and managing joint educational programmes, given that DCLead was selected by the EACEA in 2015, again in 2018, and marked as best practice following periodical assessments.

Business models, the canvas and the analysis of value

In the mid-1990s, research in business models emerged as an own field of study alternative to more traditional management approaches (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017; Zott, Amit, and Massa Citation2011). Given that business models have been used with a focus on technology and innovation management, strategy, environmental sustainability and social entrepreneurship (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017), there are a variety of interpretations concerning the definition and main purpose of this concept (Zott, Amit, and Massa Citation2011). Nonetheless, there is a relatively large consensus that the current understanding of a business model entails a rationale for the enterprise that is broader than the attempt of generating profits. Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010, 14), for example, explain that a business model describes ‘the rationale and infrastructure of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value.’ Alternatively, others stress that the most important features of business models are descriptions of the use of resources (e.g. Afuah and Tucci Citation2001; Upward and Jones Citation2016), capabilities (Seelos and Mair Citation2007) or the firm’s value proposition (e.g. Seddon et al. Citation2004).

Notably, business models are simplifications of real systems that are used for explaining performance and competitive advantage (Zott, Amit, and Massa Citation2011) or for rethinking and redesigning an organization’s strategy in order to benefit from innovations and other opportunities (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017). Moreover, business models are used to articulate, challenge, transfer and recombine tacit knowledge underlying implicit cognitive schemas and heuristics. As a result, business models simplify cognition and help build narratives that facilitate communication and they generally play an important role in coordinating and facilitating social action within the organization and with external stakeholders (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017). On this basis, it is argued that business models can be also useful for framing, understanding and communicating the features and the strategies of a social enterprise, a term that is used in this article to define private organizations explicitly and primarily working towards one or more social welfare goals while participating in the marketplace ( following Dees Citation1998; Galaskiewicz and Barringer Citation2012; Lüdeke-Freund et al. Citation2016; Michelini and Fiorentino Citation2012; Yunus, Moingeon, and Lehmann-Ortega Citation2010).

However, only rare forms of existing business models are useful for the analysis of SEs: these are the ones that consider a conceptualization of value consistent with the ones used to generalize the output and impact of SEs. In fact, unless a different understanding is made explicit, the idea of value that generally underlies a business model is defined by mainstream economics and understood as ‘exchange value’, a form of worth created from the exchange between producers and consumers, generally assumed to be an income for the producer and value in use, or utility, for the consumer. Massa et al. (Citation2017) argues that the more traditional business approaches primarily focus on the supply-side explanation of value: in fact, the expression ‘capturing value’, commonly used to explain the purpose of business models (also in Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010), generally implies that new or existing activities generate an income from a latent demand (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017). Furthermore, also the term ‘values’ (in plural), which, generally speaking, refers to goals and principles that underlie and determines the creation of value, is not contemplated in the basic traditional economic theory (Arvidsson Citation2011) and, therefore, also in the more traditional use of business models. Simply explained, this happens when firms are assumed not to have any other objectives than the maximization of profits for its owners and shareholders and consumers not to have any other goals than the maximization of utility. On the contrary, as it will be argued more in detail below, a proper understanding of the concept of values is particularly important to explain, define and categorize different types of SEs.

Nonetheless, contrarily to the more traditional applications, recent examples of socially oriented business models either address specific cases, such as SE serving the BOP (Seelos and Mair Citation2007; Sinkovics, Sinkovics, and Yamin Citation2014) or particular aspects, such as the articulation of a strategy to build legitimacy (Yang and Wu Citation2016). More generally, there are other business model analyses that are compatible with the study of SE, as they apply multidimensional notions of value and values and contemplate the creation of social worth from underlying social goals. A famous example is provided by Porter and Kramer (Citation2006) and their notion of ‘shared value’. In a nutshell, these authors argue that through specific policies and operating practices, it is possible to align a company’s search for profits (through increased sales, savings, productivity) access to resources (including raw materials, employees) and improved competitive position with the creation of social value, which is based on the goals of better quality of natural environment, nutrition, access to water and housing, health, education, and income (Dembek, Singh, and Bhakoo Citation2016). However, critiques argue that Porter and Kramer tend to focus on the ‘sweet spot’ between business and society or particular win-win situations and neglect the circumstances in which attempts to increase economic gains negatively affect the creation of social value or vice-versa. This is also argued because analyses of shared value creation tend to select only stakeholders directly involved rather than adopting a ‘system perspective’, which implies the inclusion of all stakeholders that are affected by the actions of the enterprise. This selection mechanism facilitates the uncovering of win-win situations used as illustrations, by focussing on the gains made by the stakeholders directly involved, while avoiding the negative consequences suffered by the ones affected (see Dembek, Singh, and Bhakoo Citation2016 for a review of critical assessments of the concept).

A more refined example of analysis of the application of the business model to the pursuit of social goals that also embrace a system perspective is provided by Upward and Jones (Citation2016). In their adaptation, a business model is ‘the definition by which an enterprise determines the appropriate inputs, resource flows, and value decisions and its role in ecosystems, whether natural, social, or economic’ (Upward and Jones Citation2016, 98 emphasis added). They define a Strong Sustainable Business Model (SSBM) that takes into account a socially responsive understanding of the value that considers processes of value creation and destruction among actors in businesses and value networks as social systems. The adoption of an SSBM entails that an enterprise defines its own values in the form of a ‘tri-profit’, based on a multidimensional set of units of flourishing, including money, in the economic, social and environmental dimensions (Upward and Jones Citation2016).

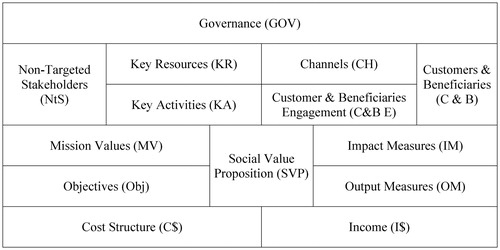

Moreover, it is argued here that not only the conceptualization of value and values are important for the application of business models to SEs, but also the use of ‘formal conceptual representations’. These are business models made explicit because they are written down in pictorial, mathematical or symbolic form (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017) and the Business Model Canvas (BMC) is one of these representations (see ). Below in this article, the application of specific ‘building blocks’ of the BMC is discussed, particularly in relation to the choices of the ones used in the SEMC. However, in this section and in order to explain the rationale of proposing an alternative for the analysis of SEs, only some general characteristics of the BMC are provided, including a critical assessment of the way in which this tool is meant to be used for non-profit organizations. A detailed review of this powerful instrument has to be considered beyond the scope of this article and therefore, interested readers are referred to its original source (i.e. Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010).

Figure 1. The Business Model Canvas/Source: adapted from Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010).

The ontology of the BMC was developed by Alexander Osterwalder (Citation2004) in his doctoral dissertation on business model innovation. The current version of the canvas, however, was only published in 2010 (in Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010) and is the result of the collaboration of Osterwalder and Pigneur with 470 practitioners from 45 countries recruited from the Business Model Alchemist (http://businessmodelalchemist.com/), Osterwalder’s blog (Stenn Citation2017). The pervasive success of this conceptual instrument in academia and among practitioners can be summarized in a few key points: before the end of 2014, the template of BMC was already downloaded over 5 million times, while the book Business Model Generation was already translated in over 30 different languages and used in more than 250 universities (Stenn Citation2017). Also, at the time of writing this article, Google Scholars indicates that the Business Model Generation has been cited over 5800 times. Furthermore, the attractiveness of the BMC is also explained by the support that it provides to entrepreneurs. Indeed, this tool is understood to pressure entrepreneurs to consider each of the elements of the business individually and as a whole, and to undertake an exercise of constant reflection, which also stimulates business creativity and innovation (Trimi and Berbegal-Mirabent Citation2012). Also, it improves a business by creating a shared language, supporting brainstorming, team building, collaboration, and creating a structure upon which new ideas and innovations are implemented (Stenn Citation2017).

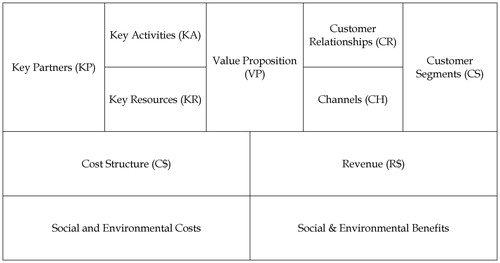

At least according to its authors, the BMC is not only designed to frame for-profit companies, but also to analyze those organizations that ‘have strong non-financial missions focused on ecology, social causes and public service mandates’ (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010, 264). In order to adapt the basic model of the canvas to the organizational settings of organizations that have social goals or as the authors state, to ‘accommodate triple bottom line business models’ (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010, 265), two additional building blocks are added to the original nine and they serve the purpose of including ‘two outcomes: (1) the social and environmental costs of a business model (i.e. its negative impact), and (2) the social and environmental benefits of a business model (i.e. its positive impact)’ (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010, 265).

However, even though the BMC is widely used and praised by many experts, it is also not immune to criticism. For example, the BMC was characterized as ‘static’ because it does not capture changes in strategy or the evolution of the model (Sinkovics, Sinkovics, and Yamin Citation2014). The most obvious limits of this instrument, however, concern its focus on the organizations and its consequent conceptual isolation from its environment, whether this is related to the industry structure (Nicola and White Citation2013) or to stakeholders such as society and natural environment (Bocken, Rana, and Short Citation2015). The two additional building blocks suggest the treatment of social and environmental costs and benefits as ‘externalities’: also for-profit organizations have an indirect social impact (e.g. economic growth, job creation and poverty reduction), which is a by-product of their pursuit of economic value (Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011). However, as argued in more detail below, these building blocks are considered insufficient to analyze the strategic choices of organizations that ‘internalize’ social and environmental benefits and consequences, by making these part of the goals and of the value proposition. In fact, similar to the exercise proposed in this article, other authors offered alternative instruments built on the BMC, that address organizations in services (Zolnowski and Böhmann Citation2014), or organizations that take into account also the physical consequences of using different resources, such is the case of the Strong Sustainable Business Model (SSBM) (Upward and Jones Citation2016) mentioned above. A justification for the proposal of a SEMC in five instrumental principles and an explanation of how this differs from the BMC is proposed in the next section and after a description of the main challenges faced by social enterprises, which provide the rationale for this new instrument.

Three challenges and one paradox for social enterprises

Social enterprises attempt to create and legitimize new institutional forms by combining market and social values (McInerney Citation2012) or core aspects of both charity and business (Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014; Galaskiewicz and Barringer Citation2012; Mair, Mayer, and Lutz Citation2015). Furthermore, they have also been described as organizations that ‘mix elements such as value systems and action logics of various sectors of society into their business models’ (Lüdeke-Freund et al. Citation2016, 12) and that display a strong analytical capacity and a problem-solving orientation striving to exploit social innovation with an entrepreneurial mindset (Perrini and Vurro Citation2006). Particularly fitting for a article concerned with adapting to a business tool for the analysis of social enterprises is the opinion of McInerney (Citation2012) that considers these hybrid organiztions a bridge between the institutional domains of the voluntary and business sectors, as they enable transfers of an idea from one to the other.

The strategy challenge

The first challenge faced by SEs considered here has been referred to as the ‘strategy challenge’ and it addresses the integration and balance of public and private value ‘so that these apparently competing for goals leverage each other to maximize operational efficiency and effective delivery of social/environmental value’ (Florin and Schmidt Citation2011, 166). As explained in more detail below when the measurement of goals is considered, social and economic goals are both important for SEs. Quite commonly, however, social and economic goals can cause tensions within these social enterprises (Cooney Citation2006). In fact, economic goals are notably best served by economic efficiency, which is a principle that can be incompatible with socially motivated measures implemented in various parts of the value chain. These can include, for example, the adoption of social prices for poorer customers or the recruitment and integration of employees because they are physically challenged or belonging to a marginalized community.

There are particular conditions or organizational mechanisms that allow for a converging pursuit of both. For clarity, three examples of these latter mechanisms are provided. The first example is the mechanism of the inclusive business model applied to some SEs that aim at ‘serving the poor profitably’ (Prahalad Citation2006) by delivering goods or services to the Bottom-of-the-Pyramid (BOP), the largest and poorest socio-economic groups. In this case, owners (through a trust) and beneficiaries are the same groups targeted by the service delivered (Michelini and Fiorentino Citation2012; Sinkovics, Sinkovics, and Yamin Citation2014). Hence, measures that improve the efficiency and the profitability of the organizations can provide benefits to the BOP as ‘owners’, while actions that improve the social value of services can provide benefits to the BOP as customers and beneficiaries.

A second mechanism that allows for a convergence of social and economic goals is the Pay-What-You-Want pricing (PWYW). Such mechanism delegates the price determination to each customer as it requires the seller to accept any price including zero. Furthermore, it allows for an enlargement of the customer base to include those that could not afford the fixed price, but also, it signals the adoption of a fair price policy and provides supporters an incentive and the opportunity to support the mission by paying also a higher price (Mendoza-Abarca and Mellema Citation2016). A third mechanism that allows for a minimization of conflicts from social and economic goals, rather than their convergence, is the ‘external social enterprises’. With this organizational arrangement, social programmes and business activities of an enterprise are kept separate so that economic and social goals can be pursued in parallel (Alter Citation2007).

The legitimacy challenge

The extent of the challenges posed by the co-existence of social and commercial values becomes even more apparent when SEs are analyzed as institutions in the need of legitimacy, defined as the generalized perception that ‘the actions of an organization are desirable, proper or appropriate’ (Yang and Wu Citation2016, 333), in the eyes of the stakeholders involved (Galaskiewicz and Barringer Citation2012) or, more broadly, within multiple institutional domains (McInerney Citation2012). More importantly than economically fit, SEs need to be perceived as trustworthy and accountable (Austin, Stevenson, and Wei-Skillern Citation2006; Galaskiewicz and Barringer Citation2012). In this regard, Galaskiewicz and Barringer (Citation2012) argued that SEs experience difficulties because they are problematic for audiences to categorize. In fact, these authors explained that categories, such as for-profit and nonprofit, are important taken-for-granted constructs of norms, expectations and standards that are used by different stakeholders to make judgments about organizations. Hence, SEs struggle to be held accountable as the behavioural norms evoked in their claims generally span across existing categories. A similar argument is proposed by McInerney (Citation2012), who focussed on the multiple forms of worth (i.e. value) created by SEs as the basis for obtaining legitimacy in multiple institutional domains. As this author explained, moral legitimacy concerns doing ‘the right thing’ according to judgments formulated by other actors in the field and SEs make claims of moral legitimacy according to the logic of the market, based on their ability to generate earned revenue in the marketplace, but also according to the moral logic of the social realm, based on their ability to solve particular social problems. Legitimacy transforms things considered true in some group (subjective meanings) into knowledge taken for granted as true by everyone (objective meanings), and it is more than only symbolic: it can be necessary to access donative forms of revenue, obtain a non-profit status or engage with particular business partners.

Consequently and for simplicity, the importance of gaining legitimacy for SEs is referred to here as ‘the legitimacy challenge’. Moreover, of particular importance for managing this challenge is justification (McInerney Citation2012), the act of providing clear and persuasive accounts of strategy and actions. This is the basis of legitimation because it is an instrument that an SE can use to shape and align the way in which it does things with the expectations of other actors. Hence, the third challenge faced by social enterprises considered here concerns the use and the fine-tuning of effective communication, internally and externally, in order to gain institutional legitimacy in different fields.

The mission measurement paradox

The third challenge that SEs strive to meet is interdependent from the first two and relates to the measurement of performance with regard to social goals and impact. Although it is a priority in research to understand the various types of contributions of SEs in terms of social values (Haugh Citation2005; Peattie and Morley Citation2008), the quantification or precise measurement of social impact remains rare (see Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011) and complicated, due to the nature of social phenomena, multi-causality of underlying factors and lengthy temporal manifestation (Austin, Stevenson, and Wei-Skillern Citation2006). The ‘disconnect between mission, objectives, and impact measurement’ has been also eloquently labelled the ‘mission measurement paradox’ (Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011, 137). Notably, the effects of this paradox are far-reaching: being SEs organizations with social goals and business behaviour, they are naturally assessed according to two sets of criteria. However, if on the one hand measures of social achievements are complex and specific to the goals and structure of the organization and hence, require justification and recognition, on the other hand, a measure of economic and financial success belong to universal business knowledge and are easily communicated and understood. As a result, this situation invites many governing boards of SEs – particularly if the SE is an independent social project of a for-profit corporation – to deviate from the normative mission and to be more inclined to ‘follow the money’ by prioritizing a strategy aimed at maximizing resources (Galaskiewicz and Barringer Citation2012; Young Citation2012). Also known as ‘mission drift’ (Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014), the focus on economic objectives and the accumulation of financial capital can lead to undesirable behaviour further undermining social goals, including giving precedence to advantaged (paying) client populations (Salamon Citation1993), decreasing investments in programs that are not profitable (Weisbrod Citation2004) and nurturing business networks before fostering community ties ( Eikenberry and Kluver Citation2004; all cited in Cooney Citation2012 ).

Nonetheless, even though the measurement of social goals is to a large extent specific to each SE, the literature suggests that public and non-profit organizations follow shared principles and adopt similar frameworks. For example, assessment measures of social objectives generally include the use of indicators, the articulation of key activities, capabilities or formalized objectives and an evaluation by key stakeholders (Lee and Nowell Citation2015; Rainey Citation2009). Moreover, in a recent review of conceptualizations of performance mechanisms designed for non-profit organizations published between 1990 and 2012, Lee and Nowell (Citation2015) identified a list of seven dimensions that non-profits consider (or should consider) when building their own performance measures. These dimensions and their definitions or scope are: (1) ‘Inputs’, or the ability to acquire and efficiently use financial and nonfinancial resources to achieve resiliency, growth, and long-term sustainability; (2) ‘Organizational capacity’, which concerns securing the human and structural features that enable an organization to offer programs and services; (3) ‘Outputs’, the dimension that requires the specification of the scale, scope and quality of products and services provided by the organization and focuses on organizational targets and activities that have direct linkages to the accomplishment of the organizational mission; (4) ‘Outcome: behavioural and environmental changes’, broader than the outputs, includes the state of the target population or the condition that the mission is intended to affect and the differences and benefits accomplished through the organizational activities; (5) ‘Outcomes: client/customer satisfaction’, comprises the extent to which the organization satisfied and met the needs of the population targeted; (6) ‘Public value accomplishment’, covers the ultimate value and impact the organization hopes to create for the community or society; and (7) ‘Network/institutional legitimacy’, which focuses on positive relationship with other organizations, reputational legitimacy within the community and field, compliance with laws and best practices (Lee and Nowell Citation2015).

The governance challenge

Finally, the ways in which an SE attempts to meet the two challenges and one paradox described above also depends on the system of governance and the choice or design of such system can be considered a fourth test, or the ‘governance challenge’. Governance defines systems and processes concerned with direction, control and accountability; it determines for what and to whom an organization is accountable (Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014). There are many different ways in which the governance of the SE can be structured, yet the main difference stems from two main factors: the origins of the main sources of funding (e.g. philanthropic donations, governmental support or own revenue) and the way in which the governing board of the organization is composed (Steinberg Citation2006). Indeed, research in the field of organizational studies suggests that the source of funding plays a fundamental role in driving organizational behaviour and strategies, particularly if an organization does not benefit from a diversified income and needs to align its values to the resource provider(s) (Froelich Citation1999; Moulton and Eckerd Citation2012 building on; Oliver Citation1991; Pfeffer and Salancik Citation2003). Moulton and Eckerd (Citation2012) reported, for example, after conducting empirical research from a large sample of non-profit organizations, that a higher level of donations from individuals is significantly and positively associated with performance on the social capital role (i.e. building reciprocal relationships and a sense of community) and negatively associated with performance on the political advocacy role (i.e. engaging directly in the political process to influence public policy outcomes), while on the contrary, higher levels of revenue from the government is strongly and positively associated with performance on the political advocacy role but negatively associated with performance on the social capital role. Moreover, the composition of the main governing board is also a particularly important factor in determining the strategy of SE. In this regard, it is worth signalling the existence of SEs that are Entrepreneurial Nonprofits, where boards are self-perpetuating or appointed, Mutual Nonprofits, governed by a board that is elected by donors and customers (Steinberg Citation2006), which are also the organizations said to adopt a multi-stakeholder approach that allows for the internalization of the objectives of stakeholders other than investors (Borzaga, Depedri, and Tortia Citation2014).

Managing the three challenges and one paradox: the example of DCLead

The four issues described above also influence the actions, strategy and organizational settings of the social enterprise used here as a case study: the Master’s programme in Digital Communication Leadership. In fact, the management of the programme is confronted with many instances of the strategy challenge, including one concerned with the targeting of its promotional efforts. The programme wants to recruit, on the one hand, the best eligible and interested candidates for its scholarships, and, on the other hand, eligible students that can afford the participation costs. The latter type of students, in particular, is required to improve the programme’s economic sustainability and to enhance its performance, as it is evaluated by the EACEA, the funding agency. Given that each promotional campaign can effectively target only one of these groups of students at a time because of its content and geographical focus, managing the strategy challenge in the field of promotional efforts entails engaging in (rarer) campaigns that can address both target groups, but also more importantly, finding the appropriate sharing of resources between promotional efforts targeting specific groups of students.

The social entrepreneurs leading the programme are also confronted with different instances of the legitimacy challenge and the mission measurement paradox. Particularly, the success in recruiting self-funding students from European countries depends on effective communication and on acquiring an excellent reputation. The value proposition of this Master’s programme is rather unique because it relies on a network of institutions for delivering different competencies and skills to the students, which spend different mobility periods in different countries. DCLead students also benefit from the two or three mobility periods in different countries, as these improve their intercultural skills. Nonetheless, although the participation in mobility periods and international programmes more in general, are certainly perceived as enriching, DCLead essentially competes with national programmes in similar subjects that do not lead to joint degrees awarded by institutions from different countries, but also provide opportunities for short-term stays in other institutions. More importantly, it is quite common in European countries that these educational programmes are partly or fully subsidized and do not charge participation costs. In other words, effective communication has to be employed in order to attract self-funding students, because DCLead has to convince potential applicants that the participation costs are worth the difference between its value proposition and the ones offered by the less expensive (or free) programmes of single universities.

Moreover, effective communication informed by quantitative and qualitative measures indicating the partial fulfillment of goals and objectives is also crucial for DCLead in order to be positively rated by the EACEA and to stand a chance for re-selection in future rounds. Based on the proposal selected for funding, the management of the programme has to deliver to the EACEA detailed reports on a regular basis. To be rated as ‘best practice’, these reports have to show progress and the partial fulfillment of the programme’s goals and objectives or provide an explanation for any delays or deviations from the original plans. Certainly, the best way to show progression in the achievement of particular objectives includes providing objective and verifiable data that makes successive reports comparable. For this purpose, the management of DCLead tracks different kinds of achievements and signs of impact, where the latter is defined in relation to its goals. There are a variety of different indicators used and they are described below in the section that explains the SEMC’s building blocks ‘Impact’ and ‘Output’.

Finally, DCLead is also confronted with a governance challenge. To solve this, the programme adopted a multi-stakeholder approach and can count on support of different boards: the Programme Board, which is composed of managers representing the three core institutions, is involved with the development of the strategy and the day-to-day operations; a Consortium Board, composed of representatives of core and associated partners, as well as by the student representatives, evaluates the programme once a year and advises the Programme Board; finally, an External Evaluation Board of specialists nominated by the Programme Board, assesses different aspects of the programme and report to the Consortium and Programme Boards. Through these different boards, managers, lecturers, representative of associated partners, students as well as external experts are involved in the design of the content and of the administrative procedures that characterize this master’s programme.

Principles for the design of a Social Enterprise Model Canvas (SEMC)

Underlying the SEMC is the following definition of a business model for SEs: the analysis of the rationale, infrastructure, capabilities and use of resources that enable stakeholders to create value for themselves and for the organization. The conceptualization of the business model presented in this article learns from the formulations used for the analysis of for-profit enterprises, including the ones that have a strong orientation to frame social and environmental consequences. Also, it distinguishes itself from existing models in order to fully consider the specificities of SEs and the challenges that they face.

Furthermore, first, it is argued that a business model for SE should learn from the work of Rokeach (Citation1973) and consider the difference between terminal values, which are the desirable end-states of existence and instrumental values, which refer to desirable modes of conduct and are the motivator to reach end-states of existence (De Mooij Citation2010). The identification of these types of value help differentiate between types of goals and rationalize the difference between official goals and the operative goals (as defined in Rainey Citation2009). Indeed, many SEs have desirable goals that are ideal, never-fully-reachable end-states, which indicate at a macro level, a guide for the strategic plan of the entire organization (McDonald Citation2007, 257). Desirable goals are the official goals and, very often, they are formulated in the mission statements of SEs. The DCLead programme, for example, aims at (1) forming reflective professionals, (2) strengthening cooperation between partners, (3) enhancing the European approach of conducting research in the field, and (4) enhancing the capacity to innovate partner institutions. None of these goals implies a clear end-point or a situation in which even one of them can be considered fully accomplished. Rather, these values provide guidance and, collectively, a direction for the strategy and development of the programme.

For simplicity, organizational goals/terminal values are labelled mission values, because ‘values’ are guiding principles (Schwartz Citation1992) and enduring beliefs (Rokeach Citation1973), but also to clearly distinguish them from the operational goals/instrumental values and desirable mode-of-conduct, labelled objectives. Also, it is assumed that mission values and objectives, together, form a system where values can be ordered in priority with respect to other values (De Mooij Citation2010). Objectives are the more practical, variable, quantifiable, short-term goals; for DCLead, these have been currently identified as: (1) To award a Master’s degree to a minimum of 20 students per intake; (2) to increase the number of applications and of countries represented; (3) to increase the reach of the website and social media; (4) to be selected by the EU for funding for two or three terms; (5) to be recognized as best practice by the EACEA; and (6) to host 15 self-funding students per intake as the basis of financial sustainability.

Moreover, there are two fundamental reasons for considering the two types of values separately in the analysis of SEs. First, this method allows for an easier framing of conflicting values. In fact, the objectives pursued can be pointing to different directions and being conflicting in the short run, as long as these objectives, singularly taken, are coherent with the more important mission values in a long run perspective. From the expert analyses of SEs summarized above, it is fair to assume that organizations respond to evolving conditions by prioritizing different short-term goals at different times; yet the strategy behind each objective should always be coherent with the mission values. Therefore, in other words, an SE might choose to prioritize economic objectives that are in conflict with social ones, in order to pursue on a short-term basis an increase of revenue that contributes to the more general and long-term goal of economic sustainability, which is necessary for the achievement of the mission values. However, the prioritization of economic goals can become a mission drift, when, in practice, economic objectives become mission values.

Second, the distinction between mission values and objectives is also useful for attempting to tackle mission measurement paradox. As explained above in the short summary of the work of Lee and Nowell (Citation2015), some performance measures relate to different types of outputs and outcomes, which are easily quantifiable, while others aim more generally at assessing outcomes by quantifying an impact of a public value-type. Therefore, the categorization of goals into mission values and objectives also facilitate the choice of appropriate measurement criteria of different kinds, as the partial accomplishment of mission values can be assessed by using measures of impact or outcomes referring to broad changes, while the fulfillment of objectives can be quantified by measures of output and outcome referring to measurable changes. Such a principle is embedded in the design of the SEMC and the case study illustrates its use in the next section.

The Social Enterprise Model Canvas (SEMC)

The SEMC is presented here as a better instrument than the BMC for framing, (re-) designing and explaining the rationale, infrastructure and use of resources that allows an SE and its intended beneficiaries to create value. Such proposal relies on the fact that the SEMC is designed by taking into consideration the challenges that SEs face so that it can be used to meet them. As explained above, these include the difficulties that SE experience in (1) blending social and economic objectives; (2) effectively communicating the objectives and their coherence with the use of resources and, more generally, the strategy; (3) assessing, or more precisely quantifying its results in terms of output, outcomes and impact; and (4) adopting the best governance mechanisms that enable the pursuit of mission values and objectives. As the description of the building blocks reveals, the SEMC is built from the following ‘instrumental’ principles: first, making mission values and objectives explicit and establishing a priority among them; second, translating mission values and objectives, respectively, into notions of impacts and measurable targets, which should also be made explicit; third, differentiating between (and within), non-targeted stakeholders (i.e. partners and affected stakeholders) and targeted stakeholders (i.e. customers and beneficiaries), in order to embrace a systemic approach and extend the rationalization of the business model’s design to the (social) environment in which this unfolds; fourth, keeping into accounts the ways in which targeted stakeholders are involved in the co-creation of value; and fifth, considering the main elements of the organization’s governance, as these are relevant to the conditions for the achievement of mission values and objectives.

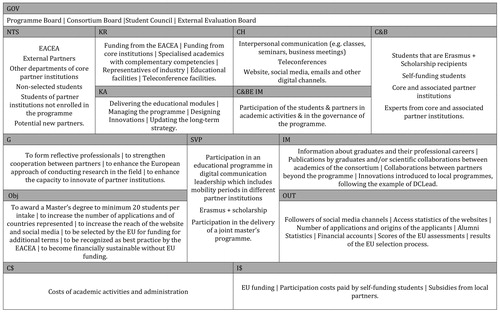

Therefore, in order to meet the challenges of SEs by adopting the instrumental principles described, the SEMC is composed of 14 building blocks (see ): four of them are inherited from the BMC and designed to contain the same type of information; five of them correspond to the remaining building blocks of the BMC, but they have been redefined to fit the analysis and terminology of SEs, and finally, five building blocks are new and specific to the analysis of SEs. The five building blocks inherited from the BMC (as defined in Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010) are: (1) Key Resources (KR), the building blocks that describes the most important assets required to make a business model work; (2) Key Activities (KA), which describes the most important things a company must do to make its business model work; (3) Channels (CH), which describes how an organiation communicates with and reaches its customers to deliver its value proposition (although, in the case of SEs, not only its customers, but also its beneficiaries); (4) Cost Structure (C$), which describes all costs incurred to operate a business model. Examples of how these building blocks have been used in analyzing the Master’s programme DCLead can be found in . The building blocks that have been re-defined to fit the analysis and terminology of SEs include: (5) Social Value Proposition (SVP), which, like the Value Proposition in the BMC, describes the bundle of products and services that create value for specific customers and beneficiaries. Alternatively to the value proposition of the BMC, however, the SVP stresses that value is social and a multidimensional form of worth. In the example of the DCLead programme, the SVP targets the partners of the consortium and the participating students, as it consists in the participation in the delivery of a joint Master’s programme for the former and the participation in an educational programme in digital communication and the possibility of an Erasmus + scholarship for the latter. The building block (6) Non-targeted Stakeholders (NtS), which replaces the Key Partnerships building block of the BMC, focuses on stakeholders that might be likely affected by the activities of the organizations and stakeholders that are partners, but not customers or targeted beneficiaries of the social actions envisaged by the organizations. The analysis of the Master’s programme DCLead, for example, identified as non-targeted stakeholders of the first type non-selected students, students of core partner institutions not enrolled in the programme and potential new partners; and of the second type, the EACEA and external partners that are involved in the External Evaluation Board. Included in the first type are stakeholders that are most likely affected (positively or negatively) by the strategy of the programme, while in the second type are included stakeholders involved in the design and delivery of the key activities. Neither the first nor the second type comprise stakeholders that are beneficiaries of the SVP.

Furthermore, the building block (7) Customers and Beneficiaries (C&B), which replaces the Customer Segments of the BMC, is used to define groups of people that an organization aims to reach and serve; (8) Customers and Beneficiaries Engagement (C&B E), which replaces the Customer Relationships building block of the BMC, suggests a deeper analysis of the relationships established by the organizations with its targeted beneficiaries, which is considered as two-ways, because customers and beneficiaries are involved in the creation of value for the organization. In the case of DCLead, the primary beneficiaries, the students, participate in the delivery of the academic activities, but also in the design of the programme through the participation of their representatives in the Consortium Board. Finally, the building block (9) Income (I$), which replaces the Revenue of the BMC, suggest the inclusion of all kinds of financial and in-kind resources that non-profit and for-profit organizations are recipients of, such as donations, fees, government funding, investments and gifts.

The last group effectively transforms the SEMC in a different instrument than the BMC, as it includes the building blocks that have been added to specifically address important features of SEs. These building blocks are: (10) the Mission Values (MV), which defines the higher, long-term, desirable end-states or goals of the organizations; (11) the Objectives (Obj), which defines the short term, desirable modes of conduct and more practical targets of the organizations; (12) the Impact Measures (IM), which defines the assessment measures of mission values; (13) the Output Measures (OM), which defines the assessment measures of the objectives; and (14) the Governance (Gov), which defines the main rules and/or boards and committees put in place to manage the organization.

In the case of the DCLead programme, the content of the ‘MV’, ‘Obj’ and ‘Gov’ building blocks have been described above (see also ). Here, it remains to be stressed that the SEMC provides a solution to the mission measurement paradox, as it allows for an easier identification of impact measures, as these are assumed to be related to the mission values and of output measures, as these are assumed to be specific to the objectives. In the case of DCLead, impact measures include: Information about graduates and their professional careers; publications and contributions to knowledge from graduates and/or scientific collaborations between academics of the consortium; collaborations between partners beyond the programme; and innovations introduced to local programmes, following the example of DCLead. Alternatively, the output measures, which relates to the objectives and are more easily quantifiable, include: the number of followers of social media channels, access statistics of the websites, and number of applications and origins of the applicants, in order to assess the promotional efforts; alumni statistics to assess the output in terms of graduates; number of self-funding students and financial accounts, in order to assess the economic sustainability of the programme; and scores of the EU assessments and results of the EU selection process, in order to assess the objective of becoming best practice.

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, McInerney (Citation2012) stated that SEs are hybrid organizations bridging the institutional domains of the voluntary and business sectors by transferring ideas from one to the other. Accordingly, this article uses SEs to propose a business tool for the analysis of the latter’s organizational settings, but suitable for understanding the use of resources and the involvement of different stakeholders of for-profit and non-profit organizations alike. First, this writing described the importance of understanding business models as well as explained the success of the most successful tool for this purpose, the Business Model Canvas. Here, it was mentioned that business models are used to articulate, challenge, transfer, and recombine tacit knowledge underlying implicit cognitive schemas and heuristics; hence, they simplify cognition and help build narratives that facilitate communication and they generally play an important role in coordinating and facilitating social action within the organization and with external stakeholders (Massa, Tucci, and Afuah Citation2017). Second, the article briefly defined the social enterprise and the most important challenges faced by this hybrid organization. These were summarized in four points: (1) the strategy challenge; (2) the legitimacy challenge; (3) the mission measurement paradox; and (4) the governance challenge. Third, the article introduces the Social Enterprise Model Canvas (SEMC), its design principles and main features. The SEMC is presented as a conceptual instrument designed following the example of the BMC and after taking into consideration the three challenges and one paradox that SEs strive to meet so that the researchers and social entrepreneurs can take advantages of the analytical power of business models. The case of the joint Master’s programme DCLead, a social enterprise financed with European funding and the revenue generated by the enrolments of self-funding students was used as an illustration of the challenges faced by social enterprises, as well as the benefits that can be drawn from using the SEMC. Furthermore, the article argues that the SEMC is better equipped to formulate a strategy aimed at the solution of social problems and to meet the most common challenges that SEs face. This is because the use of the SEMC requires: the adoption of multidimensional notions of value and values; making goals explicit and differentiating between mission values and objectives; making output and impacts measures also explicit and connected to mission values and objectives; reflections about governance principles within a framework that also includes mission goals, objectives, assessment measures, identification of segments and groups of targets and non-targeted stakeholders, and also the description of different types of interactions with these stakeholders. Finally, being also an instrument for communication, the SEMC adopts, but also refines, some of the building blocks used in the BMC in order to use the appropriate terminology for the description of SE, but also to find common ground with business thinking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Note

Notes

References

- Afuah, A., and C. L. Tucci. 2001. Internet Business Models and Strategies. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Alter, K. 2007. Social Enterprise Typology. Oregon: Virtue Ventures LLC. http://www.virtueventures.com/typology.

- Arvidsson, A. 2011. “General Sentiment: How Value and Affect Converge in the Information Economy.” The Sociological Review 59 (2_suppl): 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02052.x.

- Austin, J., H. Stevenson, and J. Wei-Skillern. 2006. “Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x.

- Bocken, N. M. P., P. Rana, and S. W. Short. 2015. “Value Mapping for Sustainable Business Thinking.” Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 32 (1): 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2014.1000399.

- Borzaga, C., S. Depedri, and E. Tortia. 2014. “Organizational Variety in Market Economies and the Emergent Role of Socially Oriented Enterprises.” In Social Enterprise and the Third Sector: Changing European Landscapes in a Comparative Perspective, edited by Jacques Defourny, Lars Hulgård, and Victor Pestoff, 85–101. Abingdon, Oxon, UK & NY, US: Routledge.

- Cooney, K. 2006. “The Institutional and Technical Structuring of Nonprofit Ventures: Case Study of a US Hybrid Organization Caught between Two Fields.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17 (2): 137–155.

- Cooney, K. 2012. “Mission Control: Examining the Institutionalization of New Legal Forms of Social Enterprise in Different Strategic Action Fields.” In Social Enterprises: An Organizational Perspective, edited by Benjamin Gidron and Yeheskel Hasenfeld, 198–221. London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- De Mooij, M. 2010. Consumer Behavior and Culture: Consequences for Global Marketing and Advertising. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage.

- Dees, J. G. 1998. “Enterprising Nonprofits.” Harvard Business Review 76 (1): 54–69.

- Dembek, K., P. Singh, and V. Bhakoo. 2016. “Literature Review of Shared Value: A Theoretical Concept or a Management Buzzword?” Journal of Business Ethics 137 (2): 231–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2554-z.

- Ebrahim, A., J. Battilana, and J. Mair. 2014. “The Governance of Social Enterprises: Mission Drift and Accountability Challenges in Hybrid Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior 34: 81–100.

- Eikenberry, A. M., and J. D. Kluver. 2004. “The Marketization of the Nonprofit Sector: Civil Society at Risk?” Public Administration Review 64 (2): 132–140.

- Florin, J., and E. Schmidt. 2011. “Creating Shared Value in the Hybrid Venture Arena: A Business Model Innovation Perspective.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 2 (2): 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2011.614631.

- Froelich, K. A. 1999. “Diversification of Revenue Strategies: Evolving Resource Dependence in Nonprofit Organizations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 28 (3): 246–268.

- Galaskiewicz, J., and S. N. Barringer. 2012. “Social Enterprises and Social Categories.” In Social Enterprises: An Organizational Perspective, edited by Benjamin Gidron and Yeheskel Hasenfeld, 47–70. London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Haugh, H. 2005. “A Research Agenda for Social Entrepreneurship.” Social Enterprise Journal 1 (1): 1–12.

- Lee, C., and B. Nowell. 2015. “A Framework for Assessing the Performance of Nonprofit Organizations.” American Journal of Evaluation 36 (3): 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214014545828.

- Lüdeke-Freund, F., L. Massa, N. Bocken, A. Brent, and J. Musango. 2016. Business Models for Shared Value. Cape Town: Network for Business Sustainability South Africa.

- Mair, J., J. Mayer, and E. Lutz. 2015. “Navigating Institutional Plurality: Organizational Governance in Hybrid Organizations.” Organization Studies 36 (6): 713–739.

- Massa, L., C. L. Tucci, and A. Afuah. 2017. “A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research.” Academy of Management Annals 11 (1): 73–104. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2014.0072.

- McDonald, R. E. 2007. “An Investigation of Innovation in Nonprofit Organizations: The Role of Organizational Mission.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 36 (2): 256–281.

- McInerney, P.-B. 2012. “Social Enterprise in Mixed-Form Fields: Challenges and Prospects.” In Social Enterprises: An Organizational Perspective, edited by Yeheskel Hasenfeld and Benjamin Gidron, 162–84. London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mendoza-Abarca, K. I., and H. N. Mellema. 2016. “Aligning Economic and Social Value Creation through Pay-What-You-Want Pricing.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 7 (1): 101–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2015.1015437.

- Michelini, L., and D. Fiorentino. 2012. “New Business Models for Creating Shared Value.” Social Responsibility Journal 8 (4): 561–577.

- Moulton, S., and A. Eckerd. 2012. “Preserving the Publicness of the Nonprofit Sector: Resources, Roles, and Public Values.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41 (4): 656–685.

- Nandan, M., M. London, and T. Bent-Goodley. 2015. “Social Workers as Social Change Agents: Social Innovation, Social Intrapreneurship, and Social Entrepreneurship.” Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 39 (1): 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2014.955236.

- Nicola, S., and G. White. 2013. “Business Models.” In Handbook on the Digital Creative Economy, edited by Ruth Towse and Christian Handka, 45–56. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Oliver, C. 1991. “Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes.” Academy of Management Review 16 (1): 145–179.

- Ormiston, J., and R. Seymour. 2011. “Understanding Value Creation in Social Entrepreneurship: The Importance of Aligning Mission, Strategy and Impact Measurement.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 2 (2): 125–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2011.606331.

- Osterwalder, A. 2004. The Business Model Ontology – A Proposition in a Design Science Approach. Lausanne. Switzerland: University of Lausanne.

- Osterwalder, A., and Y. Pigneur. 2010. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Peattie, K., and A. Morley. 2008. “Eight Paradoxes of the Social Enterprise Research Agenda.” Social Enterprise Journal 4 (2): 91–107.

- Perrini, F., and C. Vurro. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: Innovation and Social Change Across Theory and Practice.” In Social Entrepreneurship, edited by Johanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson, and Kai Hockerts, 57–85. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pfeffer, J., and G. R. Salancik. 2003. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Porter, M. E., and M. R. Kramer. 2006. “Strategy and Society: The Link between Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitive Advantage.” Harvard Business Review 84 (12): 78–92.

- Prahalad, C. K. 2006. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Rainey, H. G. 2009. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rokeach, M. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. Vol. 438. New York: Free Press.

- Salamon, L. M. 1993. “The Marketization of Welfare: Changing Nonprofit and for-Profit Roles in the American Welfare State.” Social Service Review 67 (1): 16–39.

- Schwartz, S. H. 1992. “Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, by Mark P. Zanna, 25, 1–65. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press.

- Seddon, P. B., G. P. Lewis, P. Freeman, and G. Shanks. 2004. “The Case for Viewing Business Models as Abstractions of Strategy.” The Communications of the Association for Information Systems 13 (1): 64.

- Seelos, C., and J. Mair. 2007. “Profitable Business Models and Market Creation in the Context of Deep Poverty: A Strategic View.” Academy of Management Perspectives 21 (4): 49–63.

- Sinkovics, N., R. R. Sinkovics, and M. Yamin. 2014. “The Role of Social Value Creation in Business Model Formulation at the Bottom of the Pyramid – Implications for MNEs?” International Business Review 23 (4): 692–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.12.004.

- Steinberg, R. 2006. “Economic Theories of Nonprofit Organizations.” In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, Second Edition, edited by Walter W. Powell and Richard Steinberg, 277–309. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Stenn, T. L. 2017. Social Entrepreneurship As Sustainable Development. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48060-2.

- Trimi, S., and J. Berbegal-Mirabent. 2012. “Business Model Innovation in Entrepreneurship.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 8 (4): 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0234-3.

- Upward, A., and P. Jones. 2016. “An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: Defining.” An Enterprise Framework Compatible with Natural and Social Science’. Organization & Environment 29 (1): 97–123.

- Weisbrod, B. A. 2004. “The Pitfalls of Profits.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 2 (3): 40–47.

- Yang, Y.-K., and S.-L. Wu. 2016. “In Search of the Right Fusion Recipe: The Role of Legitimacy in Building a Social Enterprise Model.” Business Ethics: A European Review 25 (3): 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12118.

- Young, D. R. 2012. “The State of Theory and Research on Social Enterprises.” In Social Enterprises: An Organizational Perspective, edited by Benjamin Gidron and Yeheskel Hasenfeld, 19–46. London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yunus, M., B. Moingeon, and L. Lehmann-Ortega. 2010. “Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience.” Long Range Planning, Business Models 43 (2–3): 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.12.005.

- Zahra, S. A., E. Gedajlovic, D. O. Neubaum, and J. M. Shulman. 2009. “A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges.” Journal of Business Venturing 24 (5): 519–532.

- Zolnowski, A., and T. Böhmann. 2014. “Formative Evolution of Business Model Representations – The Service Business Model Canvas.” ECIS 2014 Proceedings, Tel Aviv, Israel. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2014/proceedings/track20/8.

- Zott, C., R. Amit, and L. Massa. 2011. “The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research.” Journal of Management 37 (4): 1019–1042.