Abstract

This article will focus on the perennial impact of the Salesian education vision in in Salesian schools in the UK. Following an introduction outlining the history of the Salesian presence in the UK, the Salesian education vision will be explored, focused on its classical characteristics, reason, religion and loving kindness. The decline in the number of professed religious in the UK will be signposted, analogous to the decline across Europe, and the concomitant commitment to a collaboration between the Salesian congregation and lay people in a post-Vatican II context. The nature of Salesian accompaniment will then be surveyed alongside research evidence spanning a decade which constitutes evidential support for the perennial impact of the Salesian education vision.

The history of Salesian presence in the UK

The number of Salesians of Don Bosco, founded by St John Bosco (1815-1888) in 1859, grew dramatically world-wide following the death of Bosco, slowing down only in the wake of the Great War. During the period of office of Bosco’s fourth successor as Rector Major, Fr. Pietro Ricaldone (1932-51), the number of Salesians rose to 16,000. There was then a dramatic rise in numbers to a maximum of 21,614 in 1967 (see Grogan Citation2007, 1). Since Vatican II, in common with the majority of Religious Orders, there has been a steady decline in numbers which currently stand at around 15,000.

There is no doubt that Bosco’s effective use of the media of his day was instrumental in the rapid expansion of Salesian work. Looking back on his life, one sees a man engaged in a constant programme of communication. He was tireless in his efforts to make his work known, by his endless letter writing, the publication of the ‘Salesian Bulletin’ and his willingness to embrace the new technology of his day, namely photography. In an exhortation to Salesians which would be equally valid today Don Bosco said:

Our times call for action. The world has become materialistic, and so we have to go out of our way to make known the good we are doing. Even if we were to work miracles by praying day and night in solitude, the world would neither notice it or believe it. The world has to see for itself.

(Ceria Citation1989, 126)

The work of the Salesians in England expanded rapidly in proportion to the number of young men presenting themselves as Salesians, which doubled in the six years following the First World War in 1919. This expansion reached its zenith in the mid-1960s when the number of Salesians in Great Britain and Ireland touched five hundred, enabling the Order to run seven Secondary schools and two Boarding Schools for pupils with learning disabilities in Great Britain alone. Since then, however, the Order’s presence in Secondary education has taken on a new perspective, that of discerning ways in which to ensure the perennial significance of the Salesian education in general and Salesian accompaniment in particular.

The Salesian education vision

Introduction

The Decree of the Second Vatican Council on the Adaptation and Renewal of Religious Life Perfectae Caritatis (Citation1965) urged religious congregations to ‘return to the sources of all Christian life and to the original spirit of the institutes and their adaptation to the changed conditions of our time.’ (Citation1965, 2). In the context of the Salesian Congregation, Pietro Braido (Citation1981) and Pietro Stella (Citation1985) were responsible principally for this post-Vatican II renewal by producing authoritative works on the Salesian education vision, their work being built upon subsequently by a succession of scholars internationally. The following represents an analysis of key components of Bosco’s education vision.

‘Amorevolezza’ – ‘loving kindness’Footnote1

The nature of Salesian presence is summed up by St John Bosco by the Italian word ‘amorevolezza’ a word used by him to express the key element of the Salesian style of relating to young people. It is generally considered to be untranslatable and is usually rendered by ‘loving kindness’(‘bonta’ in Italian). Martin McPake (Citation1981, 114) agrees with Guy Avanzini (Citation1993, 297) in emphasising that Bosco had in mind ‘love that is seen, that is felt, that is experienced.’ This certainly seems to be the essential meaning drawn out in Bosco’s celebrated ‘Letter from Rome’ of 1884 when he reminds Salesians around the world to hold fast to the original spirit. He uses the word ‘amorevolezza’ twenty-seven times in that letter and, in a major study of the significance of the ‘preventive system’, the American Salesian Arthur Lenti (Citation1989, 7) states that Bosco had in mind:

mature, impartial, spiritual, generous, selfless self-sacrificing love. It is the love enjoined by Jesus. More simply, Don Bosco would say that the educator should love the youngsters in the same way that good Christian parents should love their children.

You are God’s race, his saints; he loves you, and you should be clothed with sincere compassion, in kindness and in humility (3:12)

Presence

For St John Bosco, the first principle of pastoral care was presence. Like the picture painted in the ‘Good Shepherd’, the Salesian educator knows his pupils, goes before them and, like the father in the story of the ‘Prodigal Son’ (Luke 15), is prepared to make the first move. Far from being simply passive watchfulness, the presence-assistance advocated by St John Bosco reflected the optimistic humanism both of himself and that of Frances de Sales. As Bosco’s biographer Fr John Lemoyne (MB III Citation1989 236-237) puts it:

Just as there is no barren, fertile land which cannot be made fertile through patient effort, so it is with a person’s heart. No matter how barren or restive it may be at first, it will sooner or later bring forth good fruit … ..The first duty of the animator is to find that responsive chord in the young person’s heart.

He considered it a sacred duty to be familiarly present among young people. … it is in the Salesian’s informal contacts with young people that true education of character is more than anywhere made possible. (cited in McPake Citation1981, 47)

By being loved in the things they like, through their teachers taking part in their youthful interests, they are led to those things too which they find less attractive, such as discipline, study and self-denial. In this way they will learn to do these things also with love.

though being in the nature of God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing (Greek ‘ekenosen’), taking the very nature of a servant

(2:6-7)

every human person looks bashfully yet longingly in the eyes of another for the yes that allows him to be It is from one human person to another that the heavenly bread of self-being is passed.

Family spirit

According to Lenti, one of the principal advantages of the involvement of animators in recreation lay in its fostering of family spirit. Recreation contributed to the building up of an atmosphere of happiness and joy, which for Bosco was a fundamental prerequisite for education. Informal, uninhibited self-expression in recreation offered the educator an opportunity to learn about the youngster and his character. The presence of educators almost as equals enhanced the morale of young people, fostering the family spirit and mutual confidence.

The building up of this ‘family spirit’ was one of the key objectives of Bosco’s system. Many Salesian scholars have spoken about Bosco’s almost preoccupation with family spirit, tracing it to his own early experience of a ‘dysfunctional’ family and the role which significant adults, such as Don Calosso, played in his early formative years. There are several testimonies to the way in which Don Bosco attempted to create a family spirit both in oratories and in schools, the following from the first Salesian Cardinal Cagliero:

The life he led in common with us made us feel as though we lived not in a school but in a family, under the guidance of a most loving father who had no other concern than for our spiritual and temporal wellbeing

(Lemoyne Citation1989 MB IV, 203)

In this ‘serene environment’ religious education was architectonic. In other words frequenting the sacraments together with the concomitant catechetical instruction and devotional practices were not merely components of the educational process but constituted the core purpose giving coherence, relevance and purpose to every Salesian apostolic initiative. Resonating with his overall aim to constantly make connections between faith and life, Bosco always made sure that the Church or chapel was close to the playground, echoing the holistic approach of Don Bosco spoken of by Pope Paul VI which has already been noted. He wanted the sense of God’s presence to be available in every situation and the door of the Church was never locked until very late in the day. He encouraged short visits into the silence of the chapel even during recreation or on the way to workshops or classes. Don Bosco wanted the young people to be aware that his whole approach revolved around the mystery of the Christian faith represented by the presence of Jesus in the tabernacle at the centre of the Church.

Bosco was convinced that adolescence constituted the critical ‘moment’ in personal formation, reminiscent of the significance of the Greek term ‘engiken’ in the Gospel: ‘The time has come. The Kingdom of God is near’. The first Article of the Salesian Constitutions (Citation1972, 19) speaks of the mission of the Salesian society in terms of contributing to the salvation of young people, ‘that part of society which is so exposed and yet so rich in promise.’ Adolescence, then, was the time when a young person was most open to making a decisive commitment to the building up of the Kingdom. While the Salesian apostolate may vary according to time and circumstance, the mission is one and the same for everyone everywhere, the salvation of youth, particularly those on the margins who are ‘most exposed to danger’. It is interesting to note the optimistic humanism of St Francis de Sales reflected in Bosco’s reference to such young people being ‘so rich in promise’.

The balance implicit in Bosco’s overarching aim of making connections between faith and life was to be the keynote, also, in the context of relationships. For Bosco, the ‘friendly, informal relationships’ between Salesians and young people referred to earlier should be characterised by detachment and disinterestedness, reflecting self-sacrificing care, in the form of untiring assistance, as opposed to any overzealous sentimentality or affectation. For Bosco, friendships should be firm and lasting as opposed to sentimental and transient. Conscious of the critical nature of the adolescent stage of development, ‘exposed to danger yet rich in promise which was’ (Lemoyne MB II Citation1989, 35), Bosco made several unequivocal statements with regard to over-zealousness in terms of affectation.Footnote2

Self-sacrifice and temperance

Bosco did, however, spend far more time endeavouring to build up an atmosphere in which diligence and industry were normative. He was convinced that idleness led to all sorts of temptation. Prior to his ordination he wrote: ‘Work is a powerful weapon against the enemies of the soul’ (Lemoyne MB I Citation1989, 385). He was convinced that work done with the right intention was of value in itself, reminding us of Aristotle’s position regarding virtue and the Thomistic position that ‘grace builds on nature’. Bosco was convinced that tireless zeal and self-giving was one of the principle ways in which Salesians could contribute to the building of the Kingdom. Immediately prior to preparing to send his first missionary expedition to Patagonia he said: ‘Work and temperance will make the Congregation flourish, whereas the seeking of an easy and comfortable life will instead bring about its death.’ (Ceria Citation1934, 722). For Bosco, ‘work and temperance’ ranked alongside ‘give me souls’ as a motto for Salesian action, echoing similar sentiments articulated by John Sullivan (Citation2002, 93):

… … teaching depends for its effectiveness on a high degree of commitment and self-involvement from staff. … … Their’ presence’ in the classroom and around the school cannot afford to be minimal. If it is to be significant, it must be one that is vigorous rather than virtual and substantial rather than superficial.

Such temperance, for Bosco, was an essential characteristic for all involved in working with young people. In constantly emphasising the need for composure and self-control, Bosco was convinced of the need for temperance as an abiding characteristic for the Salesian rather than simply informing their attitudes to duty and relationships. He also realised that there was an integral link between life outside the school and life within, both for students and teachers. He therefore consistently emphasised the need for an even temper, reminding his fellow workers of the maxim of St Francis of Sales that ‘he would not utter a word when his heart was agitated’. (Salesian Congregation Citation1972, 247)

He also often spoke of the dangers of over-indulgence and its concomitant negative effect on the efficacy of a teacher, resonating with the current debate with regard to the reasonableness and scope of the exemplar role of a teacher in a Catholic school (Sullivan Citation1998, 183). While Bosco’s jurisdiction over his workers was, to a large degree, governed by the disciplines implicit in membership of a Religious Order, he, nevertheless, was firmly convinced of the centrality of the concept of teacher as role model in the fulfilment of educational objectives.

In the context of discipline, Bosco placed a great deal of emphasis on the role of the school leader, particularly in the context of ensuring that an effective level of the Salesian style of ‘presence’ was maintained. ‘Justice’ and ‘consistency’ and ‘proportion’ were key refrains in the context of discipline which, in the case of ‘formal systematic disobedience’ (Lemoyne MB V Citation1989, 517), had to be dealt with decisively. Perceived weakness in dealing with such cases would lead only to a greater degree of indiscipline. The genesis of what would now be called a ‘management structure’ can be seen in Bosco’s suggestion that discipline should be dealt with by the Prefect of Studies (equivalent to a Deputy Head) with the Rector (Headteacher) being responsible for what would now be described as the transformational aspects of leadership.

For Bosco, the most vital aspect of ‘transformational’ leadership revolved around the maintenance of the distinctive Salesian atmosphere. The Belgian scholar Lombaerts (Citation1998) has argued that the ethos and culture of a school, the implicit curriculum, is more important than the intentional learning procedures. In this context one of the principal challenges for the school leader centres on the ability to foster a spirit of collegiality which goes beyond congeniality because it demands something greater than simply the creation of harmonious relationships. Collegiality involves fostering a commitment to the goals of an institution larger than those of any particular individual, described by Bryk (Citation1993, 299) as ‘adult solidarity around the school mission’.

Holistic formation

For Bosco Salesian ethos consisted primarily in creating a happy and serene educational environment, described more recently by Sullivan (Citation2000, 185) as ‘a hospitable space for learning’. The quality of relationships existing within any institution was, by definition, intrinsic to the whole process. Balance, however, between religious and human development, was also a central feature. Pezzaglia (Citation1993, 289) points out that, while religious formation remained the architectonic element, ‘Bosco was careful not to neglect human and professional formation’. This is expressed expressively in Bosco’s own writings (Citation1964, 145–149):

Many boys out of prison have learnt a trade – ‘won their bread with honest work’ - dissipated yet win their own bread

Many in danger of becoming delinquents have stopped giving trouble to other citizens and they are already on the way to becoming good citizens – difficult but may become reasonable and eventually win their own bread through honest work – become ‘docile’ (compliant)

Others become virtuous artisans, teachers

Few occupy positions of leadership or in the Military

Some hold positions in Universities, Law, Medicine and Engineering

Bosco also insisted that a balance had to be maintained between formal education and recreation. The Italian scholar Scurati (Citation1993, 371) points out that Don Bosco cannot be considered in isolation from the growing interest in mass education which was characteristic of Piedmont in this period. Quoting a further Italian scholar Chiossi, he points out that Bosco shared the view that ‘education was not an evil to be exorcised but a resource to be used in order to provide for the complete human and Christian formation of youth’.

While the special contribution of formal academic and vocational education should not be understated, many would argue that the part played by extra-curricular activities and informal contact with young people remained seminal. The joyful optimism generated by involvement in recreational pursuits was integral to maintaining the Salesian family spirit. Bosco wanted young people to be able to enjoy every kind of suitable recreation in a general climate of confident optimism. Some scholars suggest, therefore, that the ability to combine study and recreation was Don Bosco’s most distinctive characteristic. Scurati (Citation1993, 368-389) quotes an earlier Salesian scholar Casoti who claimed that ‘study acquired some of the joyful spontaneity of recreation while the latter acquired, to a certain extent, the composure and seriousness of the former’. He then goes on to quote a modern scholar, Dacquino who claims:

Don Bosco’s didactic method was not predominantly cerebral in approach, something that could be completed sitting at a desk; it was an educational method based essentially on an effective relationship that spanned the entire day. (cited in ‘Scurati’, 369)

Braido (Citation1981, 151) also places a great deal of emphasis on the importance of recreation, describing it as a ‘first class diagnostic and pedagogical tool for educators, and for the boys a field of irradiation and goodness’. Scurati concludes by advocating ‘the necessity of integrating school activities and extra-curricular activities into one educational synthesis’. (Citation1993, 379)

The engagement of Salesian educators in such extra-curricular activities was described earlier as an act of loving condescension. Such engagement, involving relationships that are clearly non-authoritarian, helped sow the seeds of empowerment which, like recreation itself, became an integral part of the Salesian style of education. In Bosco’s time, empowerment of young people was expressed through the formation of clubs or sodalities, referred to by Bosco as ‘compagnie’ and regarded by him as fundamental to the Salesian ‘family atmosphere’, giving it an unmistakable character of solidarity and participation.

Two key features, then, of Don Bosco’s system at the methodological level involved the creation of a familial atmosphere and empowerment, effectively involving the students in the educational process. Such empowerment could only take place through dialogue which many regard as the central component of the ‘preventive system’. Bosco was concerned with the transformation of the lives of every young person with whom he came into contact, resonating with ‘the uniqueness of the individual’, one of the key purposes of Catholic education elucidated by the Bishops Conference in Citation1996. Dialogue was the starting point which, for Bosco, could only take place if there was a genuine personal interest in each individual pupil, resonating with the ‘intrusive interest’ which Bryk (Citation1993, 141) found to be one of the characteristics of the ‘inspirational ideology’ of American Catholic schools.

Salesian accompaniment

Introduction – ‘Go to the Pump’

The key characteristics of the Salesian education vision discussed, alongside the notion of ‘intrusive interest’, represent the underpinning of the concept of Salesian accompaniment, in evidence from the outset of Bosco’s ministry. Reflecting the initiative of Jesus in inviting the two disciples to share their story in the account of the post-resurrection appearance on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24: 31–35), St John Bosco’s advice to one of his key early collaborators, Vespignani, was to ‘Go to the Pump’ (Vespignani Citation1930). At the water pump in Valdocco, Turin, near the site of Bosco’s first Oratory, boys often came together. Bosco expected his educators to be where the boys were. Such encounters in a non-formal context have the effect of building up trust which forms the basis of every educational practice or encounter. As Carlo Loots suggests ‘this practice teaches that it is best to follow first to be allowed to guide later’ (Citation2018, 5).

Bosco’s idea was that the boys would be inspired, through these initial invitational encounters of ‘going to the pump’, to join his Oratory, a name which reflects the influence of St Philip Neri (1515-95), the founder of the Oratorians. Don Bosco took over the basic features of the Oratory including catechism lessons and opportunities for recreation. He would often make the point that oratories without some element of religious instruction were simply games rooms. Luciano Pazzaglia (Citation1993, 282) is insistent on the latter point, cautioning against a reductionist view of the first Oratory as a playground or a meeting place for children: ‘what Don Bosco had in mind was a school … where … religion was practised and youngsters were inspired to live a Christian life’.

Bosco (Citation1989) was undoubtedly affected deeply by his experience of visiting the Turin prison, the Generala, a prison where he saw large numbers of boys aged 12-18. In the Memoirs of the Oratory (Citation1989) he recalls that the experience of seeing them idle, without food for body and soul, left him with a deep sense of concern:

What shocked me most was to see that many of them were released full of good resolutions to go straight, and yet in a short time they landed back in prison, within a few days of their release (Bosco, Citation1989, 182).

Sodalities: a family within the Salesian family

‘Going to the pump’, involving relationships that are clearly non-authoritarian, helped sow the seeds of empowerment which, like recreation itself, became an integral part of the Salesian style, giving it an unmistakable character of solidarity and participation.

Sodalities, derived from the Latin ‘soliditatem,’ were seminal to the Catholic ecclesial tradition and emerged strongly following the founding of major religious orders such as the Dominicans in the thirteenth century. In Bosco’s time, the formation of sodalities, referred to by him as ‘compagnia’, was a key expression of empowerment, regarded by him as fundamental to the Salesian family. The terms ‘sodality’ and ‘confraternity’ are sometimes used interchangeably, connoting a concept of solidarity around a common mission. Hilgers (Citation2012, 142) describes such sodalities as:

From the era of the Middle Ages very many of these pious associations placed themselves under the special protection of the Blessed Virgin, and chose her for patron under the title of some sacred mystery with which she was associated. The main object and duty of these societies were, above all, the practice of piety and works of charity … in the course of the sixteenth century and the appearance of the new religious congregations and associations, once more there sprang up numerous confraternities and sodalities which laboured with great success and, in many cases, are still effective.

Lemoyne (Citation1989) describes the founding of several sodalities around 1859 which combined spiritual exercises with charitable activities. The boys themselves were responsible for the running of the sodalities, under the guidance of one of the Salesians who acted as a spiritual director (Lemoyne MB Citation1989 Vol. VI, 103). Such an organisational structure promoted the building up of energetic and integrated Christian characters who gained confidence through the delegation of responsibility. Sodalities were an essential, indispensable factor in Don Bosco’s educational organisation, and they grew along with the maturing of his experience. They were an instrument for the practical realisation of those educative collaborations between pupils and educators, without which it would be idle to speak of a family spirit.

Initially the charitable activities were focused on the members of the school community. Louis Grech (Citation2019, 96) refers to the Sodality of Mary Immaculate to which the schoolboy Saint Dominic Savio belonged and makes the point that ‘being of service to others was a very useful means which Bosco used to empower the young people to mature in responsibility and spirituality’. Lemoyne points out, however, that the work of the sodalities was extended to include service to others beyond the confines of the school community. Collaboration with the Society of St Vincent de Paul was significant in this context. This accompaniment in the service of others has been described by Miguel Morcuende (Citation2018, 200) as an experience of compassion which promotes service and love for what is essential:

Compassion is the criterion by which one’s inner life is judged to be authentic. Compassion is not a feeling. It is something much deeper, its roots in the depths of the heart. From a soul that is open to what is essential in life are born genuine Gospel experiences, missionary hearts and actions with a social outreach and generous solidarity benefitting the poor.

Spiritual accompaniment

Sodalities represent a significant bridge between the building of trust gained in non-formal contexts and accompaniment at a more deeply spiritual level. This is made possible by the maturing of relationships between Salesians and young people through the media of recreation and participation in sodalities. Jack Finnegan (Citation2018, 144) encapsulates this bridge when suggesting that:

Salesian spirituality develops in spaces where intense interior energy and social solidarity converge. Through the art of friendly conversation, Salesian spiritual accompaniment encourages and supports dynamic convergence. Through gentle dialogue it seeks, identifies and promotes wise and reasonable ways to harmonise interior and social practices with the abilities and understanding of those accompanied. Salesian spirituality seeks God in ordinary ways in the ordinary activities of life, ways centred in and driven by the heart, a heart that is open and generous, humble, gentle and committed.

Denying this openness for transcendence and the encompassing meaning of human existence, which it could be argued is one consequence of a dominant post-modern secular narrative, does not do full justice to the essential dimension of being human. For Burggraeve (Citation2016, 2), the Salesian pedagogical project in the spirit of Don Bosco rejects such a closed image of the human. In contrast it ‘honours an integral or holistic view of the human whereby the existentially spiritual openness to transcendent meaning is not shied away from but actually takes centre stage’

The perennial impact of Salesian accompaniment – research evidence

Accompaniment – research evidence

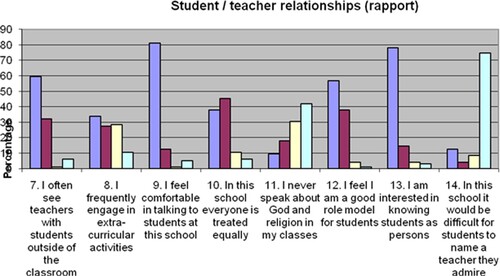

To discern the extent to which accompaniment constitutes a perennial reality in Salesian schools, Lydon (Citation2011) engaged quantitative analysis across the five secondary schools that constitute the network of Salesian schools in England. A questionnaire was distributed electronically to over 400 teachers, over 80% of whom were affiliated with Christian denominations, and the response rate of over 60% was particularly positive.

One of the aspects of the research focused especially on student–teacher relationships or rapport, seminal in the context of accompaniment. In St John Bosco’s mind, the ability of teachers to form an engaging rapport with students was a central component in building up a family spirit within a school. The characteristics of this rapport, which are linked integrally to the notion of ‘vocation’, both in the context of modelling ministry on Christ in general and modelling the educative style of St John Bosco in particular. For the moment, suffice it to say that one of the key characteristics of the Salesian style of relating is bound up not by the language of psychology but rooted in the ability of the educator to engage constructively with students.

As has been stated previously, in a Salesian context, there is a consistent focus on the value of engagement beyond the academic curriculum, reflecting a holistic perspective that focuses on the spiritual, moral, social and cultural development of the student alongside the academic curriculum. In the atmosphere engendered by constructive engagement, the spiritual development of students was architectonic, encapsulated in the aphorism ‘honest citizens and good Christians’.Footnote4 Within this system, as in the case of that of other religious orders, the teacher must aim to be a role model, breathing life into individuals and groups which make up the educating community. Constructive engagement, spiritual development and role modelling constitute the basis of the series of statements encapsulated in the questionnaire:

I frequently engage in extra-curricular activities,

I feel comfortable in talking to students at this school,

In this school everyone is treated equally,

I never speak about God and religion in my classes,

I feel I am a good role model for students,

I am interested in knowing students as persons,

In this school it would not be difficult for students to name a teacher they admire.

In the context of being a role model, central to the concept of Salesian accompaniment and a sacramental vision, 93.7% of teachers responded with a first or second rank to the direct statement ‘I feel I am a good role model for students’. This constitutes strong corroboration in terms of the literature. The median rank for this question was 1.5, again suggesting that role modelling features highly in teacher’s perception of their role, at least in the context of Salesian schools, reflecting Bosco’s conviction that the Salesian teacher must be a role model. Concomitant validation is provided by the fact that 74.7% of respondents strongly agreed that ‘it would not be difficult for students to name a teacher they admire’, further supported by the median rank.

The nature of role modelling in Salesian tradition is subsumed within the nature of Salesian presence as opposed to any elaborate treatise on its nature. This article has maintained consistently that engagement in extra-curricular activities is a central feature of such presence, both in terms of the sacrificial nature of the commitment involved, modelling that of Christ, and the extent to which such engagement constituted the critical factor in building relationships between teachers and students and, a fortiori, the Salesian family spirit. In this respect, 81.1% of teachers agreed strongly that ‘they felt comfortable in talking to students at this school’ with a further 12.6% in agreement, again with a median rank within the ‘strongly agree’ category. In the context of ‘talking’, the fact that 72.6% confirmed that they at least disagreed with the statement ‘I never speak about God or religion in my classes’ resonates with the architectonic nature of religion in the mind of St John Bosco.

Translating ‘talking to students’ into ‘engaging in extra-curricular activities’ appears, at first sight, to be challenging, in that 33.7% strongly agree and 27.4% agree that ‘they frequently engage in extra-curricular activities’, with a median rank in the latter category. The word ‘frequently’ cannot be quantified which means that the responses do not indicate necessarily that teachers are not involved in any way with extra-curricular activities. Perhaps more significantly, the responses may suggest that teachers are aware of work–life balance and, therefore, this resonates with the findings in separate research (see Lydon Citation2011) which suggested that three-quarters of those interviewed held a deeply felt conviction that such a balance is necessary in order to be effective in a school context.

The value of extra-curricular engagement in building student confidence and a ‘family atmosphere’ in schools constitutes the distinctive contribution of St John Bosco to a philosophy of Catholic education. While appearing on the surface to be disarmingly simplistic, Pope Francis, at the World Congress on Catholic Education in 2015, highlighted it as a particularly significant characteristic for Catholic Schools of the twenty-first century. Citing the example of Bosco’s integration of formal and extra-curricular into one educational synthesis in support of his assertation that education was in danger of being impoverished by an over-emphasis on academic outcomes, the Holy Father suggested that:

We need new horizons and new models. We need to open up horizons for an education that is not just in the head. There are three languages: head, heart and hand. Education must pass through these three pathways. We must help them to think, feel what is in their hearts, and help them in doing. So these three languages must be in harmony with each other (World Congress on Catholic Education 2015).

Accompaniment – research evidence 2022

Briody (Citation2022) undertook a similar survey to that outlined above in respect of Lydon’s (Citation2011) research. The survey engaged the teachers currently ministering in the same schools as those surveyed by Lydon with a relatively significant higher response rate. While it could be argued that Briody’s research moved the project more deliberately in the direction of spiritual accompaniment, the centrality of role-modelling in Salesian schools remains preeminent, reflected especially in the 91.95% of teachers who strongly agreed/agreed with the statement ‘the leadership team model what it means to be a Salesian educator’. Taken alongside the 98.73% who strongly agreed/agreed that ‘in this school it would be easy for students to name a teacher they admire’ (an increase of 15.63 when compared to Lydon’s survey), these figures constitute compelling empirical evidence of the centrality of role-modelling in the minds of teachers in terms of maintaining a Salesian style of accompaniment.

In the context of constructive engagement by teachers and students in extra-curricular activities, described in the retrieval of literature as seminal in terms of sustaining the impact of the Salesian education vision, Briody’s evidence is certainly more convincing than that of Lydon. In the latter’s survey 71.1% of teachers and leaders strongly agreed/agreed that ‘I frequently engage in extra-curricular activities’ in contrast with the more recent survey which confirms that 99.57% claim that ‘staff often go the extra mile in terms of engaging students and keeping them on board.’ While the framing of the statements is not congruent, the more positive picture being painted by the recent survey is corroborated when comparing the responses to the statement ‘in this school students are encouraged to join an extra-curricular activity’ with 97% strongly agreeing/agreeing in the more recent survey compared to 85.2% in the earlier survey.

In relation to spiritual accompaniment, Briody’s research indicates that 95.78% strongly agree/agree that opportunities for collective worship (Mass, Sacrament of Reconciliation, Assemblies) feature prominently in the life of the schools while 91.44% strongly agree/agree that ‘spiritual development is a key concern of the leadership of the school’. This indicates persuasively that a holistic perspective, the pivotal aim of Salesian education encapsulated in Bosco’s aphorism ‘honest citizens and good Christians’ referenced earlier, has been maintained in Salesian schools. It is also suggestive of the reality that there is a genuine spiritual openness as opposed to the spiritual life of the school being marginalised in favour of more managerialist approach canonising targets in relation to academic achievement.

Formation and modelling the charism

Both Lydon’s, and to a greater extent Briody’s research, demonstrates a deeply-rooted commitment to the value of maintaining a Salesian style of educating in schools in the UK. This is especially meaningful in the light of the declining number of Salesian religious in schools referenced earlier, a pan-European reality which has been addressed by religious orders in their own context including the Salesians. In the UK the study by a USA Salesian Fr Stephen Shafran (Citation1994) has proved to be influential. Shafran conducted a study which set out to determine the extent of the practice of the Salesian educational system in the 12 Salesian high schools in the USA. Following extensive quantitative and qualitative analysis he concluded that, while the Salesian education vision was strongly perceived by both students and educators, it would be necessary to introduce an organised training programme and to create a new written resource on the Salesian educational vision in order to maintain its abiding influence. From the perspective of a female religious order, Mary Jane Herb IHM (Citation1997) carried out a similar study of schools in the USA sponsored by her order, the Congregation of Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Her recommendations resonate with those of Shafran, albeit couched in more general terms. Herb maintains that, while the distinctive charism exerts some influence on the sponsored schools, the schools need to find ways of maintaining a relationship with the Congregation in the future. She then goes on to strongly recommend that ‘the challenge for religious congregations is to find ways that the sponsored institutions can be a vehicle for the prophetic witness of the congregation within the cultural context of contemporary society.’ (1997:224)

In terms of maintaining a relationship with the Salesian congregation and based on a series of interviews which Lydon (Citation2016) undertook in preparation for the National Catholic Education Association (NCEA) Conference which took place in that year, headteachers were unequivocal in articulating the empowering nature of the support ‘from the centre’. This collaboration is evidenced today by the continuing presence of the Salesian Schools Team which provides a range of resources and support including bi-annual conferences, reflecting Shaffran’s training programmes and written resources. The headteachers agreed that the work of the Schools Team was empowering, particularly at the level of revisiting the Salesian charism, thereby revitalising its awareness among teachers and the school community in general. The responses resonated with the findings of a survey engaged by Lydon in 2001, especially in the context of the approach adopted by the Salesian order, marked by ‘reciprocity and mutuality’ (Sullivan Citation2001, 134)

While recognising the importance of formation programmes, the headteachers were convinced that the presence in schools of teaching colleagues committed to living out the Salesian charism gave far greater impetus in so far as they constituted an embodiment of the charism, enabling it to be passed on in the lives of the teachers themselves. These headteachers insisted that teachers gain a far greater degree of understanding by following examples of best practice, Salesian or lay, who themselves are committed to living the Salesian education vision. In this regard they felt no compunction in challenging teachers to indicate ways in which they could contribute to the living the vision. They also emphasised the value of informal conversations with staff with regard to Salesian ways of working.

In Citation2009 Lydon’s article entitled Transmission of the Charism: A Major Challenge for Catholic Education was published in this journal. The authors believe that the decisive impact of modelling or emulating the Salesian education vision, evidenced in the responses to the quantitative instrument analysed, remains equally valid in the current context. From a sociology of religion perspective, when speaking about the survival of religious communities, Peter Berger(Citation1990, 46) uses the term plausibility structures to indicate the critical infrastructure or social base which forms the basis of a particular community and without which the community could no longer maintain legitimation. Berger explained the term by insisting that ‘the reality of the Christian world depends upon the presence of social structures within which this reality is taken for granted and within which successive generations of individuals are socialised in such a way that this world will be real for them.’ Footnote5

Taking this model on a stage further, the encouragement of senior pupils to model their lives on inspirational teachers and engage in the Salesian educational mission in the future may constitute a creative way of maintaining the charism. In this way they would be living out a values-based message which could also be regarded as a measurable feature of the impact of the Salesian mission. There is compelling evidence of this model being taken a ‘stage further’ in Salesian schools in the UK by the considerable number of former students of Salesian schools who are now teachers or leaders in those schools while other former students have taken on significant responsibilities in Dioceses in a range of pastoral ministries.

Conclusion

This article has outlined the central tenets of the Salesian education vision, highlighting the centrality of accompaniment, self-sacrifice and ‘the school as family’. It has cited fieldwork research in support of the perennial impact of the Salesian education vision, emphasising the importance of modelling best practice in relating out the Salesian education vision. In this context the presence of leaders and teachers in whom the vision is embedded represents a significant catalyst for its flourishing. A future article could focus on the extent to which a similarly positive pattern is reflected in Salesian [or schools of a similar religious order committed to the Catholic Church’s education mission] schools across Europe.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Lydon

Professor John Lydon is currently Professor of Catholic Education at St Mary's University and editor of the leading journal International Studies in Catholic Education. He is also a Professor of the University of Notre Dame. His research richly combines the disciplines of theology and education and has had a long-standing focus on applying teaching as a vocation in practice by Catholic educators and leaders, based on his extensive experience as a Catholic school leader. Significant areas of Lydon's scholarship and research focus on building spiritual capital, Catholic school leadership and maintaining distinctive religious charisms. He is a leader of the Thematic Group on Education of the Catholic-Inspired NGO Forum for education working in partnership with the Vatican Secretariat of State. He has recently been invited to form part of an international research strategy on Educating in Trust by the Federation of International Federation of Catholic Universities (FIUC). He is also a member of the Global Researchers Advancing Catholic Education (GRACE) Steering Committee. Lydon is a mentor to Masters, doctoral and post-doctoral researchers, accompanying them along their journey. He is a sought-after speaker and regularly delivers lectures in the Americas, Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. Some notable publications include Transmission of a Charism (2009), The Contemporary Catholic Teacher (2011) and the edited volume Contemporary Perspectives on Catholic Education (2018).

Fr. James G. Briody SDB

Fr James Gerard Briody, SDB joined the Salesians of Don Bosco in 1985 and was ordained priest in 1995, having studied at the University of Durham, Heythrop College London and All Hallows College, Dublin. Following ordination Fr Briody served in Salesian Schools in Chertsey, Surrey and Farnborough, Hampshire in which he held a number of leadership roles before being appointed Headteacher of Savio Salesian College, Liverpool. He was appointed Provincial of the UK Province of the Salesians of Don Bosco in August 2016, reappointed in 2022 and is currently engaged in research on the maintenance of the Salesian education vision in a contemporary context.

Notes

1 The most cursory examination of Don Bosco’s words indicates that prevention was a partial, though distinctive aspect of his educational system. In Don Bosco’s Pedagogical Experience, Braido refers to several contemporary authorities on preventive education such as Ferrante Aporti (1791-1858), a professor at the University of Turin, who spoke of the primary importance of gaining the affection and confidence of pupils. The Biographical Memoirs also refer to the numerous contacts which Bosco had with the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Indeed Bosco speaks reverentially of the contribution made to education by John Baptist de la Salle in Storia Ecclesiasica, referring to the fact that he gave up a canonry of the Diocese of Reims in order to ‘teach boys and found an institute that aims at the moral and civil education of youth’.

2 Cf. Ceria Citation1989 MB XII p.22. See also Bosco’s words in his Treatise on the Preventive System – ‘They (teachers) should strive to avoid as a plague every kind of particular friendship for their pupils, and they should also remember that the wrongdoing of one alone is sufficient to compromise an educational institute.’ In Avallone, (1979), Reason, Religion and Loving Kindness, p. 76

3 Morrison J., (Citation1979), The Educational Philosophy of St John Bosco, see Chapter 4, Note 86.

4 This seminal aim of the Salesian educational system permeates primary and secondary Salesian sources. The phrase first appeared in St John Bosco’s ‘Plan for the Regulation of the Oratory’ in 1854 and was cited in Lemoyne, J., (ed.), The Biographical Memoirs of St John Bosco/Memorie Biografiche di don Giovanni Bosco, New Rochelle NY, Salesian Publications, 1989, Volume II: 46.

5 Berger, P L., (Citation1990), The Sacred Canopy, Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion, p. 46.

References

- Avallone, P. 1979. Reason, Religion and Loving Kindness. New Rochelle: Salesian Publications.

- Avanzini, G. 1993. “Don Bosco’s Pedagogy in the Context of the 19th Century.” In Don Bosco’s Place in History, edited by P. Egan, and M. Midali, 297–306. Rome: LAS.

- Berger, P. L. 1990. The Sacred Canopy, Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Anchor Books.

- Bosco, G. 1989. Memoirs of the Oratory. New Rochelle, Salesian Publications.

- Bosco, G. 1964. Scritti (Writings) di S. Giovanni Bosco, XX, (1964), Rome, LAS – translated from Italian.

- Braido, P. 1981. Don Bosco’s Pedagogical Experience. Rome: LAS.

- Briody, J. G. 2022. The Extent to which it is Possible to Maintain the Salesian Charism in Salesian Schools in a Contemporary Education Culture in the UK. Twickenham: St Mary’s University.

- Bryk, A. 1993. Catholic Schools & The Common Good. Cambridge, MASS: Harvard University Press.

- Buber, M. 1974. To Hallow This Life – An Anthology. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Burggraeve, R. 2016. “The Soul of Integral Education Orientations for a Contemporary Interpretation of ‘Religione’.” In The Salesian Pedagogical Project KU Leuven, edited by C. Loots, 1–26. Leuven: KU Leuven.

- Catholic Bishops Conference of England & Wales. 1996. Principles, Practices and Concerns. London: CES.

- Ceria, E. 1934. Annals of the Salesian Society. Rome: LAS.

- Ceria, E. 1989. The Biographical Memoirs of St John Bosco(Volumes XI-XVIII), (BM). New Rochelle: Salesian Publications. Vol XVIII.

- Dickson, W.J. 1988. The Dynamics of Growth. Rome: LAS.

- Finnegan, J. 2018. “Spiritual Accompaniment: The Challenge of the Postmodern and the Post Secular in the Contemporary West.” In Salesian Accompaniment, edited by F. Attard, and M. Garcia, 131–152. Part 3 Bolton: Don Bosco Publications.

- Grech, L. 2019. Accompanying Youth in a Quest for Meaning. Bolton: Don Bosco Publications.

- Grogan, B. 2007. History of the Great Britain province. Rome: Salesianum.

- Herb, M. J. 1997. An Investigation of the Role of a Religious Congregation, as Founder, in the Shaping of School Culture in a Catholic school. Boston College, http://scholarship.bc.edu.dissertation.

- Hilgers, Joseph. 2012. “Sodality.” In The Catholic Encyclopaedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church, edited by Charles George Herbermann, 142–148. New York: Robert Appleton Company. vol. 14.

- Lemoyne, J. 1989. The Biographical Memoirs of St John Bosco. (MB), New Rochelle NY: Salesian Publications. Volumes 1-X.

- Lenti, A. 1989. Don Bosco’s Educational Method. New Rochelle NY: Salesian Publications.

- Lombaerts, H. 1998. The Management & Leadership of Christian Schools. Groot Bijgaarden: Vallams Lasalliaaans Perspectif.

- Loots, C. 2018. The Theory of Presence of Andries Baart. Leuven: Forum Salesiano.

- Lydon, J. 2009. Transmission of the Charism: A Major Challenge for Catholic Education in Grace, G., (Editor), International Studies in Catholic Education. London: Routledge.

- Lydon, J. 2011. The Contemporary Catholic Teacher: A Reappraisal of the Concept of Teaching as a Vocation in the Catholic Christian Context. Saarbrucken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Lydon, J. 2016. The Value of Maintaining Distinctive Religious Charisms. Washington DC: NCEA.

- McPake, M. 1981. The Constitutions – A Simple Commentary. Madras (India): The Citadel.

- Morcuende, M. 2018. “Personal Accompaniment in the Salesian Educative-Pastoral Plan.” In Salesian Accompaniment Part 3, edited by F. Attard, and M. Garcia, 187–200. Bolton: Don Bosco Publications.

- Morrison, J. 1979. The Educational Philosophy of St John Bosco New Rochelle, Salesian Publications.

- Pazzaglia, L. 1993. Don Bosco’s Option for Youth and his Educational Approach’ in Egan & Midali, Egan, P., and Midali, M., (Editors), Don Bosco’s Place in History, Rome: LAS.

- Salesian Congregation. 1972. The Constitutions and Regulations of the Society of St Francis of Sales, (Hereafter CR). Rome: LAS.

- Salesian Congregation. 1986. The Project of Life – A Guide to the Salesian Constitutions. Rome: LAS.

- Scurati, C. 1993. Classroom & Playground: A Combination Essential to Don Bosco’s Scheme of Total Education in Egan & Midali.

- Shafran, S. 1994. The Educational Method of St John Bosco as School Culture in the Salesian High Schools in the United States, Ann Arbor, Michigan (USA), UMI Dissertation Services.

- Stella, P. 1985. Don Bosco Life and Work. New Rochelle: Salesian Publications.

- Sullivan, J. 1998. Compliance & Complaint’ in Irish Educational Studies. Volume 17.

- Sullivan, J. 2000. Catholic Schools in Contention. Leamington Spa: Veritas.

- Sullivan, J. 2001. Catholic Education: Distinctive and Inclusive. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Sullivan, J. 2002. “Leadership and Management.” In Contemporary Catholic Schools in the United Kingdom, edited by A. Hayes, and E. Gearon, 91–106. Leominster: Gracewing.

- Thevenot, X. 1993. Don Bosco Educare e il Systemo Preventivo (Education and the Preventive System) in Egan & Midali.

- Vatican Council II. 1965. Adaptation and Renewal of Religious Life Perfectae Caritatis. London: CTS.

- Vespignani, G. 1930. A Year at the School of Blessed Don Bosco (1886–87). San Benigno Canavese: Salesian Publications.