Abstract

This article examines the steep rise in self-confidence among the Arab-Palestinian public in Israel over the last two decades. We suggest that this self-confidence is partially due to higher education levels and the rise of the middle class. We argue that these enhanced levels of human capital have led to more concerted cultural, political and social activism. Our analysis is grounded in the ‘politics of faith’ which we define as a willingness to change the status quo. As such, this article contributes to literature explaining how political and social developments affect collective activism in the public sphere—both within one’s one own community and in relation to the state.

The Palestinian Arab minority in Israel is a national minority in a Jewish state and has been struggling to re-build their cultural, political and social institutions since the 1948 war. In recent decades the community has become better educated and more economically stable. Simultaneously, their internal institutions—both political and civic—have become increasingly well-developed and established. As such, they are displaying increasing self-confidence. This article, which examines internal Palestinian Arab attitudes and behaviors, draws a connection between the two positing that increased education levels have contributed to these developments. The article also contributes to existing research that seeks to elucidate transformations which have occurred recently among Palestinian citizens in Israel. We examine two dimensions of Palestinian life: Firstly, we outline increased levels of human capital due to changes in the level and quality of education; secondly, we examine willingness to contribute to public space in general and particularly among those who have obtained higher education. We aim to answer the question: Does this increase in human capital improve confidence levels among the Arab Palestinian minority and, accordingly, their willingness to undertake collective action to improve their status in Israel?

This article first outlines the ways in which the Palestinian Arab minority is marginalized in the Jewish state while pointing to key economic, political and social developments that have taken place over time. It then discusses ways in which this research contributes to a growing body of literature on this minority and political participation. The subsequent section traces increased levels of education over time and attendant job market integration while also noting the importance of Palestinian civil society organizations. We then outline the research methodology which was a survey focusing on levels of education and civic participation and present and discuss the findings from this survey. The article concludes by highlighting the research contribution.

The Arab Palestinian Minority in Israel

Following the 1948 war, which Palestinians refer to as Nakba [catastrophe], only 150,000 Arabs remained in the part of their homeland that became the State of Israel. Although this group received Israeli citizenship, in the aftermath of the 1948 war, these Palestinians were challenged in re-establishing their pre-war social and political institutions. The Nakba left the cultural and political elite and the middle class destitute and disoriented, while the remnants of this community lacked cultural and financial and resources.Footnote1 Seventy-five years later (2023), Israel’s Arab Palestinian citizens number approximately 1.6 million,Footnote2 comprising 21.1% of the population and Israel’s largest minority group.Footnote3 However, they live under the political domination of the 74% of the population which is Jewish.

From 1949 to 1966, the Israeli government imposed a military rule regime on the Palestinian-Arab population. This tight controlFootnote4 impeded political activity and organizing within the Arab community. Simultaneously, Palestinians in Israel were forced to abandon an agrarian way of life;Footnote5 they became much more urbanized and found work as manual wage laborers in Jewish cities. However, they were marginalized within Israel while also disconnected from the Palestinian national movement and the larger Arab world socially, economically, academically, culturally and politically.Footnote6

In the aftermath of the 1967 war, two important developments took place. The Israeli government discarded its policy of military control and also replaced Palestinians in Israel with a cheaper source of labor: Palestinians from the newly occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Simultaneously, Arabs’ economic standing improved. This was the start of a new, educated middle classFootnote7 and triggered an economic, political and social transformation. Access to higher education improved, and many young people obtained college and university education within Israel and Eastern Europe. This new university-educated elite established national Arab-Palestinian institutions such as the National Committee of the Heads of Arab Local Authorities (1974), the National Union for Arab University Students (1975), the National Union for Arab High School Students (1975) and the Committee for Defense of Arab Lands (1975). They began the difficult work of rebuilding Arab cultural, political and social life in Israel.Footnote8

Political Transformation of Arab Palestinians

Research investigating Palestinian Arab political and social developments typically focuses on their relationship with the state and the Jewish majority and as it relates to the larger Israeli Palestinian conflict. These studies harness modernization theory, the internal colonialism modelFootnote9 and the control model among others to explain their findings.Footnote10 Some researchers have examined increased political consciousness and participation. Ilan Peleg and Dov Waxman suggest that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a major factor explaining Arab Palestinian’s political engagement.Footnote11 Oded Haklai traces increased political activism to changes on the national level including the relationship between the state and the Arab minority.Footnote12 For these scholars, transformations over the past three decades ‘mirror changes in Israeli politics at large.’Footnote13 Amal Jamal, however, believes increased political mobilization is due to changes in discourse in the community. He argues that there is widespread disillusionment with the liberal conception of equality, especially its substantive dimensions within the ‘Jewish and democratic’ definition of the state. Jamal also points to an emerging Arab elite that is attuned to global human rights and minority rights discourse and, specifically, a discourse of Arab indigeneity as the moral and political basis for rights.Footnote14 All of these explanations are based on ways in which developments external to the Arab Palestinian community have influenced increased levels of political consciousness and mobilization.

Our explanation is based on internal developments. We argue that the Arab Palestinian minority’s increased political consciousness is due to a belief in its own power and strength, i.e. faith in its own politics. Our analysis is based on Michael Oakeshott’s book, The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Skepticism.Footnote15 He describes the politics of faith as a desire to achieve the collective goals of society as opposed to advancing individual interests. Oakeshott argues that achieving political, social and economic goals depends on ‘human efforts, and confidence … and faith in human power.’Footnote16 In examining deeply divided societies where a minority is dominated by a majority, the politics of faith relates to minorities’ ability to challenge the dominant group.Footnote17 Three principles underly this faith: basic confidence in a group’s ability to achieve positive change for their community; organized and coordinated efforts to maximize their use of human resources; and prioritization of their goals and interests. Ghanem, similarly, points to three crucial variables in influencing minority politics: demographic and territorial strength; minority levels of cohesion; and the strength of minority leadership.Footnote18 Where these factors are present, a minority is well-placed to satisfy its needs and place demands on the state.

Building on the work of others,Footnote19 we claim that political developments within Israel’s Arab Palestinian community reflect the community’s basic confidence in its ability to work in an organized fashion to achieve its collective interests. We further posit that this is related to demographic and social developments which have bolstered their self-confidence and, accordingly, consolidated their human capital. This has engendered important changes in socio-cultural life and political activity. Currently, the Arab community in Israel is at its strongest point historically in terms of human capital and this has enhanced its cultural, political and social strength.

Development of Human Capital

The Israeli government has sought to control the Arab minority demographically and geographically while inhibiting its human capital and educational achievements. Despite multiple impediments to development, Arab Palestinians have harnessed a numerous strategy to overcome these challenges including enhanced levels of education, better integration into the job market and the establishment of strong civil society organizations, primarily over the last three decades.

Recently, levels of educational achievement, particularly in post-secondary institutions in Israel and abroad,Footnote20 have increased significantly. In 1961, only 7% of Arab students completed secondary education yet by 1976 this number had reached 20%, then 51% in 2008 and 80% in 2014. Of those who reached grade 12 in 2014, 47.8% were eligible for a matriculation certificate.Footnote21 Similarly, in 1990, only 20% were eligible to take matriculation exams yet by 2019 this number reached 63%. Consequently, significantly more Arab students meet the requirements for admission to universities.Footnote22

Advanced degrees enable the Arab minority to enter the labor market, integrate into the regulated economy and participate in larger domestic socio-economic processes in various fields and this has improved their socio-economic status.Footnote23 In the first two decades of the current century, the employment level of Arab males rose from 66% to77 percent. For women, the rate rose from 19.8%-to 38.2% during the same time period. This had important economic implications: between 2010–2020, 28% of Arabs had joined the middle class. This is smaller than the relative proportion of the middle class in the Jewish community but much higher than in previous decades.Footnote24 Arab Palestinians view education as an important vehicle for socio-economic mobility as it enables a certain level of integration into state institutions and in the larger labor market.Footnote25

A revolution in Israeli higher education also has facilitated access to advanced degrees. During the 1980s and 1990s, the government established many new colleges in the country’s geographic periphery, and, accordingly, closer to Arab Palestinian population centers. Increased physical access to these institutions, coupled with improved academic performance meant that more Arab Palestinians could access higher education through these institutions.

The Arab education system also has grown tremendously since 1948. In the academic year 1948–1949 there were 46 schools in Arab communities in Israel, 45 of them elementary schools and one high school. By 1979–1980 there were 371 schools in Arab localities: 312 primary schools and 59 high schools. In 2009–2010, the number of schools in Arab localities had reached 878, including 537 elementary schools and 341 high schools. Similarly, drop-out rates fell. According to current data, there are some 1,122 schools in Arab localities, including 657 elementary schools and 465 secondary schools.Footnote26

Arab Palestinians are not seeking advanced degrees only in Israel: many study abroad. In 1948, 1,113 Arab students studied outside of Israel but the number had fallen to just 70 in 1964. Yet, since the early 1970s, many Palestinian Arab students began to study in countries of the former Soviet Union.Footnote27 According to Khalil Nakhleh,Footnote28 some 300 Arab students (approximately 50–60 annually) received funding for their degrees by the Israeli communist party in 1979. Between 1986–1996, 1,096 Palestinian students from Israel completed their studies in countries of the former Soviet Union. Similarly, since Israel signed a peace agreement with Jordan in 1994, thousands of Arab students have studied in Jordan, many of them choosing medicine.Footnote29 In the past decade, many students also have begun to study medicine and para-medical professions in West Bank universities operating under the Palestinian Authority. In 2018, the number of Arab students from Israel studying outside the country reached 15,341.Footnote30 The choice to study abroad frees Arab Palestinians from the exclusion and marginalization they face in Israel while simultaneously enabling them to benefit from continued opportunities for education.

Generally, members of minority groups choose to study professions that allow them to advance professionally irrespective of the discrimination that they may face in their larger societies. Arab Palestinians are no exception to this phenomenon; they choose careers in law and healthcare at particularly high rates.Footnote31 In the legal profession, in 1964 there was one Palestinian judge in the general Israeli court system yet in 2020 there were 72, which is about 9% of the Israel’s judges. Similarly, some 9% of all lawyers in Israel are Arab Palestinian.Footnote32 Arab Palestinians are over-represented in pharmacology. In 1970, only 16 pharmacists in Israel were Arab (3%), but by 2015, this number had risen to 2,933, accounting for 36% of pharmacists in Israel.Footnote33 Among doctors, in 1970 less than 1% of physicians were Palestinians. By 1990, 947 physicians in Israel were Palestinians, 7% of the total; this number rose to 11% (4000 Palestinian doctors) in 2016.Footnote34 Similar trends are evident with dentists: In 1980 there were only 25 Arab dentists (1% of all dentists in Israel); this rose to 304 by 1990 (7% of all dentists), and by 2015 there were 1,752 Arab dentists practicing in Israel—some 17% of all dentists. Many degrees for these professions were obtained abroad.Footnote35

Despite these accomplishments, for a variety of structural reasons, Arab Palestinian labor market participation lags behind that of Jewish citizens. Therefore, in 2015, the Israeli government approved plan 922—a five-year plan with a budgetary allocation of 15 billion Israeli shekels. The plan aimed to enhance and integrate Arab Palestinian citizens into the Israeli economy through economic investment in Arab areas. It focused on several priority areas: education, employment, housing, infrastructure, transportation, housing, and investment in developing the capacity and professionalism of local (municipal) government. This program was renewed for the years 2022–2026 at 30 billion shekels with the aim of building on and enhancing advances made in the context of the initial plan.

Increased human and social capital is also reflected in the area of civil society. Education, globalization, and modernity have contributed to this development. Furthermore, Arab Palestinians understand that they must create their own alternatives to dependence on state institutions. These organizations address a wide variety of needs and are active in numerous fields including arts and culture, the environment health, legal advocacy, religion, scientific research, social welfare, and more.Footnote36 In 1974 only one such organization existed but by 2006, a total 2,609 organizations had been established employing 1,517 activists.Footnote37 These institutions not only serve a number of critical social and economic functions, they have also provided meaningful employment for many highly educated Arab academics who, in some cases, have not been able to penetrate the public and private sectors in Israel. They fill gaps in local and national government provision of services due to discrimination, neglect, or because of the relatively weak financial and social standing of many Arab local governments. They have also facilitated networking and served as sites for collaboration and cooperation that can transcend political, geographic, ideological, familial and other boundaries. As such, they create alternative spaces of belonging and engagement for the Arab minority.

Methodology

Our research in quantitative; we conducted an opinion poll to examine individuals’ readiness to contribute to promoting issues of public and collective concern for the Arab minority. We assumed that higher educational attainment would correlate positively with willingness to contribute to the public good. To this end, we surveyed a representative sample of 300 Palestinian-Arab citizens of Israel. They reflect different religious affiliations (Muslims, Christians and Druze), genders (men and women), geographic areas (Galilee in the North, Triangle in the Center, Negev in the South and mixed Arab-Jewish cities) and educational levels (from primary school to doctoral degrees). The distribution is as follows:

Gender: Male (63.7%); female (36.3%)

Religious Affiliation: Muslim (77.7%); Christian (10.7%); Druze (10%); and undeclared (1.7%)

Geographical Area: Galilee/North (57.7%); Triangle/Center (26.3%); and Negev/South (16%)

Education Level:

11.7 percent did not complete high school but had some elementary and/or junior high school education

8 percent had completed high school but didn’t have a matriculation certificate

20 percent completed high school with a matriculation certificate

12 percent held a non-academic vocational high school certificate

29 percent had a B.A.

5.3 percent had an M.A. or PhD

14 percent did not have any education

We identified these variables as possibly being relevant and influential in relation to attitudes toward civic engagement. The analysis of survey results enabled us to compare among these different variables. We collected data during May 2017 via phone interviews (both land lines and cell phones). Initial questions focused on social and demographic data. We then asked for participant responses to a series of questions examining their attitudes and levels of trust regarding Arab Palestinian representative political and social authorities in Israel (i.e. The Arab Higher Follow-Up Committee, political parties, religious leaders, heads of local authorities). We then queried them about their willingness to engage in such civic activities as signing a petition, participating in a demonstration, voting in elections and engaging in a political debate. Finally, we asked about their willingness to support activities initiated by different institutions such as the Higher Follow-up Committee. The collected data was analyzed using standard software analysis methods.

Research Findings

Research on political behavior has demonstrated a decline in levels and patterns of political participation among citizens. Often the indicator for this is voting in elections, although other research on political and social activism such as falling rates of participation in political and social activities organized by institutions and civic groups such as political parties, social movements and unions yield similar results.Footnote38 While these older forms of participation are declining, new types of political participation have emerged including youth initiatives and utilization of the virtual space and social networks.Footnote39 The findings outlined below examine these trends as it relates to Palestinian Arabs in Israel.

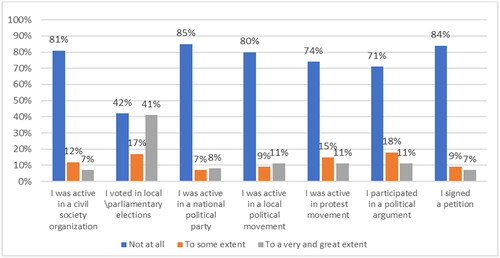

demonstrates that, in our sample, respondents’ levels of political and public participation were very low. The vast majority of those surveyed indicated that they were not involved in political and public activities or events. Other research has found that their political participation was, for the most part, limited to voting in local or national elections; indeed, local voting rates exceed 85% on average.Footnote40 According to above figure, 42% responded ‘not at all’ to the question on voting in local/parliamentary elections.Footnote41

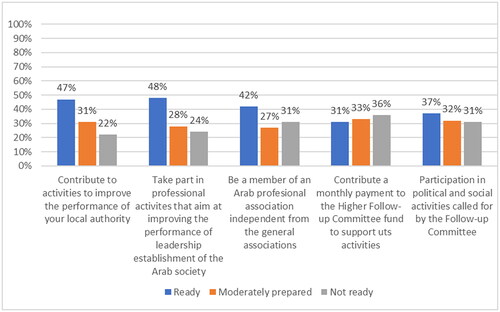

The survey also uncovered low levels of trust between Arab citizens and the political institutions that are meant to represent and serve them (see ). This distrust may explain respondents’ reticence to participate in political activities and events. Generally, levels of trust were between 14 and 26%. Indeed, less than 15% reported being active in political parties; the vast majority were not active in any institution. Low confidence levels seem to indicate that there is divergence and disunity between Arab citizens and representative Arab institutions.

Figure 2. Trust in the political and social institutions among the Palestinian Arab citizens in Israel.

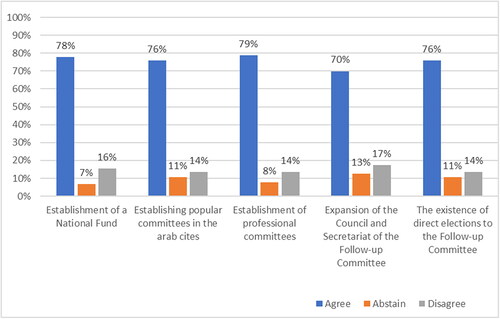

Despite low levels of political and public participation and low levels of confidence in political and social institutions, most respondents wanted to transform these same institutions as indicated in . Based on this data, this sample of Arab citizens favors a radical shift in political action that would give the Arab public increased influence, indicated by the strong support for expanding the ranks of the Follow-up Committee to include members who are elected directly by the public and through popular committees on specific issues alongside existing professional committees.

Figure 3. Attitudes toward steps required to improve the status of Palestinian Arab citizens in the State of Israel.

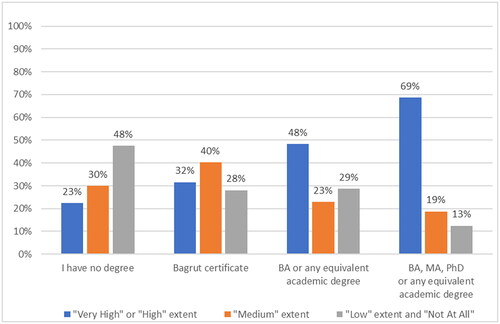

Despite a lack of confidence in existing Arab institutions and low levels of participation in Arab organizations, there is significant willingness to participate and contribute to public activities and events and a desire to improve the performance of political leaders and representative bodies as indicated by . The call to establish independent Arab trade unions can be explained by the fact that the national general trade union, known as the Histadrut, is dominated by Jewish Israelis and, therefore, does not appropriately represent the interests or needs of Palestinian citizens of Israel.

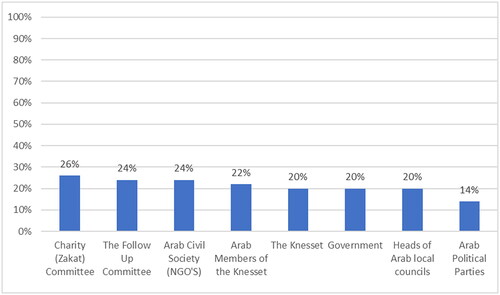

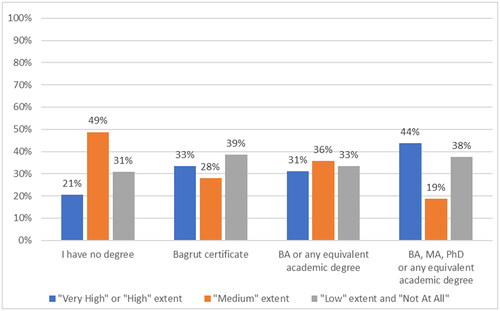

We sought to assess whether educational achievement influenced these findings. As demonstrates, increased educational levels indicated stronger willingness to be involved in social and political issues. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between level of education and ‘readiness to participate in an independent Arab union.’ The resulting correlation was statistically significant (r = 0.21, p < 0.001). This seems to indicate that Arab citizens who have higher levels of education and, therefore, stronger human and cultural capital, are more willing to participate in political and civic activities.

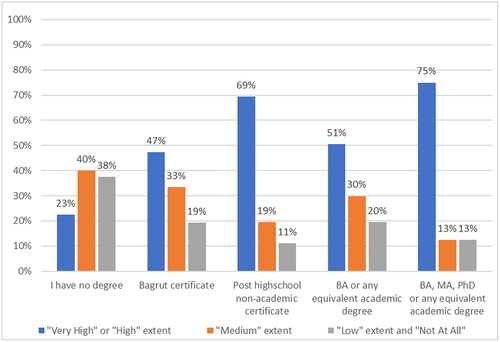

There was a similar correlation in relation to participating in political and civic activities connected to the Higher Follow-Up Committee. Our research demonstrated that, in particular, respondents were interested in activities that would have an impact on the public sphere which could transcend the more local affiliations of kinship and geography (see ). Here again, a Pearson correlation coefficient found a statistically significant correlation (r = 0.19, p < 0.01); therefore, the higher the respondent’s human capital as expressed by education level, the greater the demand for improved performance of the Follow-Up Committee. We also found a statistically significant correlation (r = 0.15, p < 0.01) between education level and ‘readiness to participate in professional activities aimed at improving the performance of the leadership bodies of the Arab society.’ This seems to indicate that more educated segments of the Arab community are both more critical of the Higher Follow-Up Committee and also are more willing to engage in activities that contribute to improving its performance. Regarding willingness to participate in activities that improve the performance of this committee, a Pearson correlation indicated statistically significant findings (r = 0.62, p < 0.001). Respondents’ critical attitude toward the performance of the Follow-up Committee seemed to indicate greater willingness to participate in activities that could improve the performance of leading institutions in Arab society.

Figure 6. Participating in political and civic activities connected to the Higher Follow-Up Committee.

Despite low levels of confidence in the mayors of Arab local authorities and respondents’ low levels of activity in local political parties, there is a willingness to be engaged in activities intended to improve their performance among those with higher education levels as indicated in .

Figure 7. Willingness to be engaged in activities intended to improve the performance of political institutions.

This research demonstrates that there is greater willingness to engage in collective action among respondents with academic degrees and, specifically, to contribute to improving the performance of central Arab Palestinian institutions. This is consistent with changes in Arab society. Along with the increase in education levels among Palestinian Arabs and the founding of Palestinian Arab civil society organizations, there has been a concurrent increase of those involved in or employed by the private and public sectors. Furthermore, this political discourse is influenced by awareness of globalization and international human rights and minority rights standards.

Despite these changes, increased education levels have yet to bring about a qualitative change the Arab community’s political conditions or in the quality and type of interactions between citizens and their representative institutions. Rather, our survey points to a very low level of political and public participation. It seems this is due to poor confidence levels in representative institutions leading to reluctance to participate in political activities and events. Most respondents did express a desire to have a greater influence in civic and political life, particularly among those with higher education levels. Therefore, we claim that higher human capital as indicated by academic achievements is correlated positively with readiness to contribute time, financial resources and personal competencies to advance the interests of their public.

Conclusion

This research explored factors that contribute to the capacity and willingness of minorities living on the cultural, economic and political margins to contribute to the civic and political life of their own communities. Existing research indicates that internal factors (demographic weight, leadership performance, and social and political cohesion) are more suitable variables for explaining the level of civic activity among marginal groups, than variables external to the group.

During the past two decades, an ever-expanding body of literature has focused on the Palestinian Arab minority in Israel and its relationship to the Jewish state and Jewish majority, or the larger Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as it relates to political and civic activism. Other research, in contrast, has examined interactions between the majority and the minority populations. This article examined relevant internal factors with a particular focus on education levels. Using the framework of the ‘politics of faith,’ and examining trust, we found that education levels are a critical determinant of willingness to engage in civic and political activism.

Human and social capital at both the individual and the collective levels, are fundamental for promoting cultural, democratic and social growth and development. Putnam writes about what he terms ‘social immunity’ and characterizes this as interdependence and social cohesion. It involves the willingness of individuals to contribute their own resources, such as time, financial resources and personal capabilities to advance their communities socio-economically. He claims that this quality makes it easier for social groups to overcome challenges and to advance.Footnote42

Palestinian Arabs in Israel have experienced significant developments since the Palestinian Nakba and the founding of the state of Israel. Their internal political and social structures have become much stronger, as has their level of human capital. Socio-cultural changes such as rising employment levels and increased educational attainment have led to a much stronger and more significant middle class. This new Arab elite has established political and social organizations, as well as new forms of activism. They also are more willing to contribute to civic and political causes. In sum, they are exhibiting increased collective self-confidence.

We attribute the on-going situation of inferiority of the Palestinian minority in Israel to national government policies. Nevertheless, the increased confidence among the public has failed to make a noticeable difference in the political sphere, due to ineffective and untrustworthy political action by Arab minority political institutions. Specifically, the High Follow-up Committee, the Joint List, and the United Arab List that emerged from it in 2020 are viewed as being incompetent and unable to transform their representative role into organized and effective political action. Thus, improving the functioning of the political institutions representative of the minority is a key factor for translating the changes reviewed in this article into effective political change capable of truly transforming the status of the Palestinian minority in Israel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Ian Lustick (Citation1980) Arabs in the Jewish State: Israel's Control of a National Minority (Austin: University of Texas Press).

2 This data includes only official citizenship holders of the Arab minority; including the Arab residents of East Jerusalem, which Israel annexed in 1967, elevates the number of Palestinian Arabs to 1.95 million.

3 Only 17.2% are considered official citizens and the remaining 3.9% have legal status of permanent residents. See Central Bureau of Statistics, selected annual data (Citation2021). Available online at: http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/newhodaot/hodaa_template.html?hodaa=201711279, accessed 04/08/2022.

4 Yair Bauml (Citation2007) A Blue and White Shadow, The Israeli Establishment's Policy and Actions Among its Arab Citizens: The Formative Years, 1948–1968 (Haifa: Pardis Press).

5 Elia Zureik (Citation1979) The Palestinians in Israel: A Study in Internal Colonialism (London: Routledge).

6 Majid Al-Haj (Citation1993) The Arabs Educational System in Israel: Issues and Trends (Jerusalem: The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies).

7 Aziz Haidar (Citation1990) The Arab Population in the Israeli Economy (Tel Aviv: International Center for peace in the Middle East); and Aziz Haidar (Citation1995) On the Margins: The Arab Population in the Israeli Economy (London: Hurst).

8 Eli Rekhes (Citation1993) The Arab Minority in Israel: Between Communism and Arab Nationalism, 1965–1991 (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuhad and Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies in Tel Aviv University).

9 Zureik, The Palestinians in Israel.

10 Lustick, Arabs in the Jewish State.

11 Ilan Peleg & Dov Waxman (Citation2011) Israel's Palestinians: The Conflict Within (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

12 Oded Haklai (Citation2011) Palestinian Ethnonationalism in Israel (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press).

13 Ibid, p. 8.

14 Amal Jamal (Citation2011) Arab Minority Nationalism in Israel: The Politics of Indigeneity (London: Routledge), pp. 11.

15 Michael Oakeshott (Citation1996) The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Skepticism (New Haven: Yale University Press).

16 Ibid, pp. 23, 114.

17 For detailed description, see: As'ad Ghanem & Mohanad Mustafa (Citation2018) Palestinians in Israel: The Politics of Faith after Oslo (New York: Cambridge University Press).

18 As'ad Ghanem (Citation2012) Understanding Ethnic Minority Demands: A New Typology, Nationalism & Ethnic Politics, 18(4), pp. 358–379.

19 See Doron Navot, Aviad Rubin & As'ad Ghanem (Citation2017) The Israeli Elections 2015: The Triumph of Jewish Skepticism, the Emergence of Arab Faith, The Middle East Journal, 71(2), pp. 248–268; and As'ad Ghanem & Mohanad Mustafa (2018) Palestinians in Israel: The Politics of Faith after Oslo (New York: Cambridge University Press).

20 Aziz Haider (2021) New Arab-Palestinian Middle Class in Israel: Economic, Socio-Cultural And Political Aspects (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University); Rassim Khamaisi (Citation2017) The Growth of the Middle Classes and its Impact on the Management of Arab Local Authorities (Haifa: University of Haifa).

21 Ministry of Education (Citation2012) Eligibility for matriculation certificate, in: The Jerusalem Post (Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Post Ltd). Please note that not all students who complete secondary school sit for these exams.

22 Ibid.

23 Higher education has an enormous effect on the social-economic status of the population. Since 2000, the employment rate of Arab men started to recover and delivered consecutively until 2017 from 66 to 77 percent; similarly, the employment rate of Arab women also rose consistently since 2001 when the employment rate of Arab women was 19.8, and nearly doubling by 2018 when it reached 38.2 percent.

24 Gershon Shafir (Citation2017) From a Clear Differentiation to a Covert Differentiation of Israel's Arab Citizens in the Galilee, Merhav Tsebore [The Public Sphere], 13, pp. 73–98. (in Hebrew).

25 Al-haj, The Arabs Educational System in Israel.

26 Al-Haj, The Arabs Educational System in Israel; Yoav Peleg & Gershon Shafir (2005) Being Israeli: The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press). (in Hebrew); Ministry of Education (Citation2021) Data on Eligibility for Matriculation 2021 (Jerusalem: Ministry of Education).

27 Khalil Nakhleh (Citation1979) Palestinian Dilemma: Nationalist Consciousness and University Education in Israel (Shrewsbury: Association of Arab-American University Graduates).

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Khalid Arar & Kussai Haj-Yehia (Citation2017) Trends in Higher Education Abroad Among Palestinian Minority in Israel, in D. Velliaris & D. Coleman-George, eds., Handbook of Research on Study Abroad Programs and Outbound Mobility (Sydney: AHEPD Book Series), pp. 66–87; Economist Division (2019) Weekly Economic Review: Barriers to the Integration of the Arab Population in the Higher Education System (Ministry of Finance, September 2019).

31 Arar & Haj-Yehia, Trends in Higher Education Abroad Among Palestinian Minority.

32 Guy Lurie (Citation2015) Appointment of Arab Judges to Israeli Courts, Law and Government, 16, pp. 307–315 (in Hebrew); Central Bureau of Statistics (Citation2019). Available online at:

33 Ministry of Health (Citation2016) Data on Health workers (Jerusalem: Ministry of Health).

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Majid Shihade (Citation2011) Not Just a Soccer Game: Colonialism and Conflict among Palestinians in Israel (New York: Syracuse University Press); Kussai Haj-Yehia & Boaz Lev Tov (Citation2018) Preservation of Palestinian Arab Heritage as a Strategy for the Enrichment of Civil Coexistence in Israel, Social Identities, 24(6), pp. 727–744.

37 Amal Jamal (Citation2017) Arab Civil Society in Israel: New Elites, Social Capital and Oppositional Consciousness (Jerusalem: Hakebotz Hameouhad Press). (in Hebrew).

38 Ronald Inglehart & Gabriela Catterberg (Citation2002) Trends in Political Action: The Developmental Trend and the Post-honeymoon Decline, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43(3–5), pp. 300–316.

39 James Sloam (Citation2012) Introduction: Youth, Citizenship and Politics, Parliamentary Affairs, 65(1), pp. 4–12.

40 Arik Rudnitzky (Citation2020) Voter Turnout in Knesset Election: The Real, The Deal and The Hope for Change (Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute). (in Hebrew).

41 The gap between the voting in the local elections and the answers of those surveyed in the survey stems from the fact that the question referred to voting in both the local elections and the Knesset elections. Accordingly, the voting rate in the Knesset elections among the Arab public is much lower and ranges from 45% to 65% in the last five election sets between 2019–2022.

42 Putnam Robert (Citation2000). Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, Originally Published in Journal of Democracy, Culture and Politics: A Reader 6(1), pp. 223–234.

References

- Al-Haj, M. (1993) The Arabs Educational System in Israel: Issues and Trends (Jerusalem: The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies).

- Arar, K., & Haj-Yehia, K. (2017) Trends in higher education abroad among Palestinian minority in Israel, in: Velliaris, D. & Coleman-George, D. (eds) Handbook of Research on Study Abroad Programs and Outbound Mobility, pp. 66–87 (Sydney: AHEPD Book Series).

- Bauml, Y. (2007) A Blue and White Shadow, The Israeli Establishment’s Policy and Actions among its Arab Citizens: The Formative Years, 1958–1968 (Haifa: Pardis Press).

- Central Bureau of Statistics (2019). Available online at: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/pages/2021/%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%9B%Dyour 7%99-%D7%93%D7%99%D7%9F-%D7%A4%D7%A2%D7%99%D7%9%D7%99%D7%9D-%D7%91%D7%A1%D7%95%D7%A3-%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%AA-2019,-%D7%9C%D7%A4%D7%99-%D7%AA%D7%9B%D7%95%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%A0%D7%91%D7%97%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%AA.aspx. (accessed 03 June 2023).

- Central Bureau of Statistics (2020) Selected Annual Data. Available online at: http://www.cbs.gov.il/shnaton68/st02_05x.pdf, accessed November 22, 2022.

- Central Bureau of Statistics (2021) Selected Annual Data. Available online at: http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/newhodaot/hodaa_template.html?hodaa=201711279, Accessed June 03, 2023.

- Economist Division (2019) Weekly Economic Review: Barriers to the Integration of the Arab Population in the Higher Education System (Jerusalem: Israeli Ministry of Finance).

- Ghanem, A. (2012) Understanding Ethnic Minority Demands: A New Typology, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 18(3), pp. 358–379.

- Ghanem, A., & Mustafa, M. (2009) Arab Local Government in Israel: Partial Modernisation as an Explanatory Variable for Shortages in Management. Local Government Studies, 35(4), pp. 457–473.

- Ghanem, A., & Mustafa, M. (2018) Palestinians in Israel: The Politics of Faith after Oslo (New York: Cambridge University Press).

- Haidar, A. (1990) The Arab population in the Israeli economy (Tel Aviv: International Center for Peace in the Middle East).

- Haidar, A. (1995) On the Margins: The Arab Population in the Israeli Economy (London: Hurst).

- Haidar, A. (2021) New Arab-Palestinian Middle Class in Israel: Economic, Socio-Cultural and Political Aspects (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University).

- Haj-Yehia, K., & Lev Tov, B. (2018) Preservation of Palestinian Arab Heritage as a Strategy for the Enrichment of Civil Coexistence in Israel, Social Identities, 24(6), pp. 727–744.

- Haklai, O. (2011) Palestinian Ethnonationalism in Israel (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press).

- Inglehart, R., & Catterberg, G. (2002) Trends in Political Action: The Developmental Trend and the Post-Honeymoon Decline, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43(3–5), pp. 300–316.

- Jamal, A. (2011) Arab Minority Nationalism in Israel: The Politics of Indigeneity (London: Routledge).

- Jamal, A. (2017) Arab Civil Society in Israel: New Elites, Social Capital and Oppositional Consciousness (Jerusalem: Hakeotz Hameouhad Press). (in Hebrew).

- Khamaisi, R. (2017) The Growth of the Middle Classes and its impact on the Management of Arab Local Authorities (Haifa: University of Haifa).

- Khaib, M., & Riziq, S. (2021) Youth Survey in the Palestinian Community in Israel (Shfar’am: The Galilee Society).

- Lurie, G. (2015) Appointment of Arab Judges to Israeli Courts, Law and Government, 16, pp. 307–315. (in Hebrew).

- Lustick, I. (1980) Arabs in the Jewish State: Israel’s Control of a National Minority (Austin: University of Texas Press).

- Ministry of Education (2012) Eligibility for matriculation certificate. The Jerusalem Post (Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Post Ltd).

- Ministry of Education (2021) Data on Eligibility for Matriculation 2021 (Jerusalem: Ministry of Education).

- Ministry of Health (2016) Data on Health workers (Jerusalem: Ministry of Health).

- Nakhleh, K. (1979) Palestinian Dilemma: Nationalist Consciousness and University Education in Israel (Shrewsbury: Association of Arab-American University Graduates).

- Navot, D., Rubin, A., & Ghanem, A. (2017) The Israeli Elections, 2015: The Triumph of Jewish Skepticism, the Emergence of Arab Faith, The Middle East Journal, 71(2), pp. 248–268.

- Oakeshott, M. (1996) The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Skepticism (New Haven: Yale University Press).

- Peled, Y., & Shafir, G. (2005) Being Israeli: The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press). (in Hebrew).

- Peleg, I., & Waxman, D. (2011) Israel’s Palestinians: The Conflict Within (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Putnam, R. D. (2000) Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital: Originally Published in Journal of Democracy, Culture and Politics: A Reader, 6(1), pp. 223–234.

- Rekhes, E. (1993) The Arab Minority in Israel: Between Communism and Arab Nationalism, 1965–1991 (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuhad and Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies in Tel Aviv University).

- Rudnitzky, A. (2020) Voter Turnout in Knesset Election: The Real, The Deal and The Hope for Change (Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute). (in Hebrew).

- Shafir, G. (2017) From a Clear Differentiation to a Covert Differentiation of Israel’s Arab Citizens in the Galilee, Merhav Tsebore, (The Public Sphere), 13, pp. 73–98. (in Hebrew).

- Shihade, M. (2011) Not Just a Soccer Game: Colonialism and Conflict among Palestinians in Israel (New York: Syracuse University Press).

- Sloam, J. (2012) Introduction: Youth, Citizenship and Politics, Parliamentary Affairs, 65(1), pp. 4–12.

- Zureik, E. (1979) The Palestinians in Israel: A Study in Internal Colonialism (London: Routledge).