Abstract

The answer to the question “Why dump on us?” is a pragmatic one, though supported by underlying power relations. In the UK 10 sites, mostly at existing nuclear locations, have been listed for the potential development of new nuclear power stations. They are sites where land is in friendly ownership, some infrastructure is available and where some public support may be anticipated. This pragmatic siting strategy is supported by a strategic siting assessment process which, in effect, provides premature legitimation for a predetermined strategy. The sites are examples of “peripheral communities”, socially and economically marginalised by a process of “peripheralisation” which reproduces and reinforces their relative powerlessness. Power relations shifting over time in response to changing discourses on nuclear energy explain the persistence of peripheral communities as sites for nuclear activities. The emergence of a contemporary Discourse of Security has emboldened government and the nuclear industry to focus new build once again on these sites. The burden of nuclear risk extending into the far future thus becomes concentrated at a few socially and physically vulnerable locations. In the push for new nuclear there has been greater centralisation of decision making and a concomitant diminution of participation and community involvement. Issues of fairness between communities and generations have been subordinated in the hurry to proceed. “Why dump on us?” thereby becomes a plaintive recognition of the inevitable unfairness to specific places of a broader, though controversial, purpose of meeting energy needs.

New reactors, old sites

As the so-called “nuclear renaissance” in Europe gathers pace, attention is focusing on existing nuclear locations as the sites for the new generation of nuclear reactors. In the case of the UK, the government has made this quite explicit: “We expect that applications for building new power stations will focus on areas in the vicinity of existing nuclear facilities. Industry has indicated that these are the most viable sites” (BERR Citation2008a, p. 33). This preference was subsequently confirmed when British Energy (former owner and operator of several sites but subsequently sold off to Electricité de France) undertook a round of consultations stating, “We believe the best locations for potential new build are adjacent to existing power station sites” (British Energy Citation2008). Proposals for potential sites in other European countries, generally speaking, also reflect a strategy of building at existing locations, exemplified by the two under construction at Flamanville (Normandy, France) and Olkiluoto (Finland) as well as prospectively in Sweden.

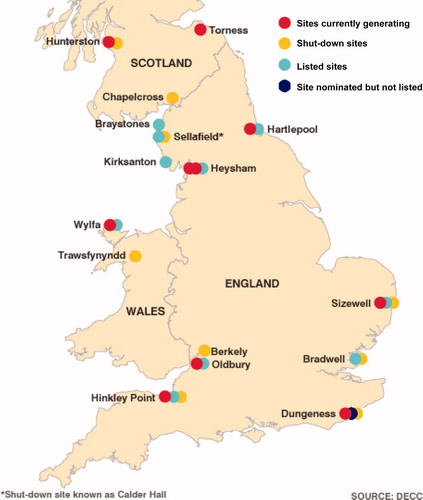

Initially, 11 sites in England and Wales (the Scottish government has currently taken a non-nuclear stance) were nominated by so-called Credible Nuclear Power Operators (CNPOs) ( ). CNPOs encompass a variety of companies involved in energy supply, most of them under foreign ownership. Under the Government's strategic siting assessment (SSA) process each site was assessed against a range of criteria to determine its suitability for inclusion in a final list of suitable sites to be published alongside the Government's National Policy Statement (NPS) on nuclear energy (BERR Citation2008b; DECC Citation2009a). As a result, 10 of the sites were listed in the draft nuclear NPS as “potentially suitable for the deployment of new nuclear stations by the end of 2025” (DECC Citation2009b, p. 44). Dungeness, in south east England, was dropped on grounds that adverse impacts on internationally designated sites of ecological importance could not be avoided or successfully mitigated (DECC, Citation2009c). Three alternative sites were identified as “worthy of consideration”: at Druridge Bay, Northumberland; Kingsnorth, Kent and Owston Ferry, Lincolnshire. However, little site-specific analysis or preparation had been done and it was concluded that it would not be possible to deploy them by 2025, the target date for new nuclear stations (Atkins Citation2009, p. 66). Of the 10 listed sites, four (Hinkley Point, Oldbury, Bradwell and Sizewell) are in southern England; five are in the north of the country at Hartlepool, Heysham, Sellafield, Kirksanton and Braystones; and one, Wylfa, is in Wales. With the exception of Braystones and Kirksanton which are greenfield sites, the eight other sites are adjacent to existing operating or closed power stations or, in the case of Sellafield, within the country's largest nuclear reprocessing and waste management complex. All are on or near the coast or on estuaries where cooling water is available, although the southern sites (Hinkley Point, Sizewell, Oldbury and Bradwell), are in locations liable to inundation from rising sea levels, storm surges and coastal erosion.

Figure 1. Listed sites for new nuclear power stations. (Based on DECC Citation2008a,Citationb, Citation2009a-Citationf)

The main aim of this article is to explore and explain answers to the question somewhat provocatively posed in the title, Why dump on us? It begins (Section 1) descriptively by setting out, as I see them, the various pragmatic reasons which have led to proposals for new build stations on old sites concluding that such a strategy constitutes a case of premature legitimation. I then turn in Section 2 to a more analytical approach, seeking to explain the new build strategy in terms of power relations. In doing so I shall revisit the thesis of peripheralisation which explains the conditions in which the original sites were established and how these (peripheral) conditions are favourable to the location of new build. I go on in Section 3 to examine the social and political context for the new build programme showing how nuclear has benefited from a shift towards energy and environmental security in the discourse on energy. In the following Section 4 I try to demonstrate some of the ethical consequences of this discursive shift notably the burdens which a programme of new build places on peripheral communities and future generations. This focus on intergenerational equity leads into a final section 5 which contrasts the centralised and undemocratic nature of the strategy for new build with the voluntary approach being used to find a site for a deep geological repository for legacy wastes. In concluding, the article speculates that the drive to new nuclear may be slowed, if not halted, leaving a few peripheral communities to bear indefinitely the burden of risk unfairly imposed upon them.

Section 1 – pragmatic but inequitable siting

The easy option

Existing sites for new nuclear power stations in the UK (and probably in other countries, too) are favoured for three reasons. They are in friendly ownership either already in the hands of nuclear operating companies or soon to be so. Most of them have facilities and infrastructure (notably transmission lines) available or, at least, with potential for upgrading. And, they are situated in communities where public support allegedly derives from familiarity with the nuclear industry and the jobs and investment it will bring. For instance, in appraisals for specific sites the Government makes clear its view that “people living and working nearby have had a long time to get used to there being an adjacent nuclear plant so this is unlikely to be a problem at this location” (DECC Citation2009f, p. 42). This claim must be treated as an assumption or assertion, in effect propaganda in the absence of any site-specific in-depth research into local community attitudes, values and opinions on the case for new build. What evidence there is on community attitudes is conflicting, with some studies indicating a positive response to nuclear energy in existing nuclear locations while others suggest that an increase in knowledge may result in elevated anxiety. One in-depth study on Living with Nuclear Power (Pidgeon et al. Citation2008) portrays the multi-faceted, complex and sometimes ambiguous perspectives experienced by local people. This study was carried out before the new-build programme was announced and so did not consider how perceptions might be affected once new reactors became a tangible prospect in the vicinity.

New build is not simply a set of reactors producing electricity, it is accompanied by radioactive waste management facilities in the form of encapsulation plants, waste stores and cooling ponds for spent fuel which will remain on site long after the plant has ceased to generate power. The focus on new jobs is clearly intended to stress the developmental benefits to local communities. The Nuclear Industry Association (NIA), in its application to justify new nuclear power stations (required under the Ionising Radiation Regulations of 2004), makes a bold claim that there will be “significant socio-economic benefits to the local economy resulting from a new nuclear power station”. It goes on to add that that each plant would produce around 500 jobs and “such long-term, high quality and stable jobs would be especially valuable in the remote communities that host nuclear power stations” (DECC Citation2008a,Citationb, p. 102). However, there is no recognition of the potential economic detriments that may arise through the negative image and anxiety created by new stations. The risks may act as a deterrent to inward investment and, at some sites, may have a detrimental impact on existing economic activities such as tourism, farming or fishing. There may also be a blighting impact. The emphasis on the positive benefits of nuclear energy almost entirely eclipses the understated risk from nuclear waste which will be present at all these sites. In short, the pragmatic approach to siting focuses on production of energy and the jobs it provides; while the detriments from long-term highly radioactve wastes on site, though not denied, are certainly downplayed.

Strategic siting assessment – a legitimation strategy

The SSA process is the means by which the UK government justifies and legitimates the selection of these sites. The government consulted on the proposed SSA process in 2007 (DTI Citation2007) and set out its response in the White Paper on Nuclear Power (BERR Citation2008a). A detailed consultation on the proposed criteria for site selection was undertaken during 2008 (BERR Citation2008b) and the government published its response in early 2009 (DECC Citation2009a). Later that year a further consultation was launched enabling the public to “Have Your Say” on the 11 nominated sites. This led on to the draft NPSs on Energy and Nuclear Energy (DECC Citation2009b,d) which confirmed the list of 10 sites.

The SSA process provides an apparently rational and comprehensive set of criteria against which sites were assessed. The criteria are divided into “exclusionary” (those which, if not met, would automatically disqualify a site) and “discretionary” which, singly or taken together, may make a site unsuitable. Of the original exclusionary criteria only two, demographics and proximity to military activities remained in the final list. Footnote1 The demographics criterion seems both ambiguous and contradictory. It is expressed in terms of population density weighted for distance from the site. On the one hand, it is argued that it is no longer necessary to adopt a “remote” siting criterion, as was the case for the first generation of Magnox power stations in the UK. On the other hand, “urban” locations, those where the population density is above the limiting criteria to be assessed on the basis of population characteristics, are regarded as “strategically unacceptable”. Instead, a compromise “semi-urban” criterion is proposed, which seems neither fish nor fowl. If it is not necessary, on safety grounds, to site a plant at a remote location then it should follow that it is safe to locate it close to urban areas. What is implied by this criterion is that it is acceptable to impose radioactive risks on rural areas and small towns but quite unacceptable to put a mega nuclear power station near where power is most needed, namely in the major conurbations. It is clear that the demographics criterion is drafted in such a way that none of the existing (and now listed) sites would be excluded.

This pragmatic approach is equally apparent when we come to the discretionary criteria. The two most critical are: flooding, tsunami and storm surge; and coastal processes. The Government indicates that to meet these criteria suitable mitigation measures can be undertaken and simply requires developers to “set out why it is reasonable to conclude that it is practicable to protect the site against flood, storm surge and coastal processes throughout the lifetime of the site and indicate any countermeasures that are likely to be required” (DECC Citation2009a, p. 40). Given the increasingly severe predictions of sea level rise combined with extreme wave height and increases in the possibility of storm surge, defending a nuclear power station, let alone neighbouring coastlines, may turn out to be a very tall proposition indeed for future generations to manage.

Among the other discretionary criteria are those concerned with environmental impacts. Most of the sites tend to be in or close to areas designated as of national or international ecological significance. New power stations in such sensitive locations as the East Anglian coast or the Severn estuary would severely compromise precious habitats, wetlands and landscapes. The criteria covering environmental protection rather than excluding such development merely require developers to “confirm they are able to avoid, minimise or mitigate these effects” (BERR Citation2008b, p. 66). It may be expected that much effort will be made to minimise impacts but the environmental criteria are, ultimately, permissive.

On the basis of the environmental assessment only one site, Dungeness, failed to pass all the criteria. It failed to meet the criterion on “internationally designated sites of ecological importance”. It was considered that the adverse impacts of developing a new nuclear power station on “the unique coastal system and an internationally important shingle site” could not be mitigated (DECC Citation2009c, p. 71). It was also unlikely that new, greenfield sites away from existing nuclear activities would come forward. In the event two of the Cumbrian sites (Kirksanton and Braystones), though greenfield locations, are close to the Sellafield nuclear complex (where a site has also been listed) within an area of West Cumbria that is being branded the “Energy Coast”. There are no sites listed that are in truly non-nuclear locations. In effect the SSA process would appear to be an elaborate exercise in achieving premature legitimation for a predetermined policy.

Section 2 – security and siting new nuclear power stations

Peripheral communities – sanctuaries for new nuclear

The pragmatic strategy of proposing new nuclear stations on or close to existing nuclear sites relies on a set of conditions or characteristics that indicate where sites are likely to be available and acceptable. These characteristics were originally set out in the thesis of “peripheralisation” (Blowers and Leroy Citation1994) which was intended to provide a socio-geographic explanation for the locations of locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) such as chemical plants, power stations, major infrastructures or waste disposal facilities. Nuclear power stations and radioactive waste facilities are a defining example of LULUs. They tend to be located in what may be called “peripheral” communities, places on the edge of the mainstream. The thesis identifies five characteristics of peripheral communities. These are:

Remoteness: communities in areas that are either geographically remote or relatively inaccessible. | |||||

Economic marginality: places which are monocultural, dependent on a dominant employer or employment sector | |||||

Political powerlessness: key decision making occurs elsewhere, often in metropolitan centres. | |||||

Cultural defensiveness: expressing ambiguous and ambivalent attitudes with feelings of isolation and fatalistic acceptance of nuclear activities. | |||||

Environmental degradation: In the case of nuclear projects this means close to areas of radioactive contamination or places where radioactive risk is present. | |||||

This peripheral condition is reproduced and reinforced by a process of peripheralisation. On the one hand, the very characteristics of peripheral communities mean they will continue to be places to which LULUs such as nuclear facilities will gravitate. Industry and community are brought together by traditional integrating institutions such as trade unions, local councils or business associations. They tend to speak for the community and defend the economic base. On the other hand, where greenfield sites are proposed for nuclear projects community leaders are often able to mobilise resistance. In these places it is possible to integrate and focus opposition that cuts across social, economic and community boundaries. Among the examples are: the resistance of communities in eastern England to proposals for low level radioactive waste repositories during the 1980s (Blowers et al. Citation1991); the long standing opposition to the spent fuel storage and deep disposal facility at Gorleben in Germany (Carter Citation1987; Blowers and Lowry Citation1997); protests of farmers, local communities and environmentalists against potential sites for an underground laboratory in France (Mays Citation2005) and many others.

While these processes of peripheralisation are predictable they are not inevitable. Some peripheral communities may not possess all five characteristics and there may be internal conflicts which weaken the pronuclear consensus. In some non-nuclear communities in greenfield locations it may be possible to achieve nuclear projects through negotiation, incentives and compensation (as in France, for instance). The success or failure of a siting programme will vary according to the type of project, the political opportunities and the local political culture; and the pattern and outcomes of conflicts will vary over time and between places (Leroy and Verhagen Citation2003). Economic conditions appear to be the crucial determinant.

Whilst recognising there may be exceptions it is nonetheless fair to hypothesise that the response to proposals for new nuclear power stations in the UK will vary according to the degree to which communities may be said to be peripheralised. Support is likely to be strongest in the more remote regions such as west Cumbria which has a high dependence on the industry or in Anglesey in Wales where the local economy is being undermined by the closure of the aluminium works and the forthcoming shut down of the Wylfa Magnox nuclear power station. But, the industry's most favoured sites for new nuclear stations are the southern sites in England (Sizewell, Hinkley Point, Oldbury, Bradwell) where remoteness is local rather than regional. The economic and political support is strongest nearest the sites while further away, as dependence lessens or is non-existent, the risks from nuclear energy appear to be uncompensated by any benefits. Bradwell provides a good illustration of this effect with the Blackwater estuary creating a clear contrast between the southern shore surrounding the site where there is some support for the jobs that will be created and the northern shore, within 2 miles of the site but over 30 miles away by land, where predominant economic and social concerns are quite different focusing around safety and security risks to humans, the local fishing and tourist industry and the marine environment (BANNG Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2010a,Citationb).

The process of peripheralisation, therefore, is one of push and pull, a mutually reinforcing process reflecting inequalities between communities. It helps to explain the location of nuclear facilities, why the geography of nuclear energy has remained stable and why it may prove difficult to site power stations or waste management facilities in non-nuclear locations. However, in order to understand the conditions most likely to result in the actual deployment of nuclear stations we need to look at power relations. At certain times nuclear interests have been able to exert power to exploit the periphery; at other times they have been forced to retreat in the face of powerful anti-nuclear interests. The changing balance of power relations may be explained in terms of changing discourses that enable resources to be mobilised in favour or against nuclear energy at different points in time. In the next section, I shall explore these discourses and reveal how we have reached a point where, power, pragmatism, and the periphery have combined to produce the further expansion of nuclear energy at its existing locations.

Section 3 – changing discourses and nuclear power

From post-war to present: a shifting balance of power

Power relations are shaped and shift in response to changing discourses. Discourses are a way of apprehending the world, defined by Hajer as follows, “a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts and categorisations that are produced, reproduced and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which a meaning is given to physical and social realities” (Hajer Citation1995, p. 44). Discourses, then, set the context within which power relations are defined and developed. At the political level discourses constrain and facilitate the ability to mobilise and deploy the power resources (investment, technology, protest and so on) that enable specific ends to be achieved. Discourses shift over time and, for a while, may coexist and overlap before one succeeds another and becomes settled and dominant. As I shall endeavour to show, we may well be in a period of such transformation at present.

During the post-war history of nuclear energy it is possible to identify four successive discourses. In the early years and lasting into the early 1970s there was a long period during which the nuclear industry was developing around the world. It is possible to portray this as a period when there was a Discourse of Trust in Technology. This was a time, in the UK, when the “peaceful atom” was being promoted as green, cheap (“too cheap to meter”) and clean (safe) and a source of unlimited energy. It was an era, notably in the 1950s but persisting beyond, where austerity limited aspiration and communal provision secured by the welfare state settlement achieved a degree of solidarity and common purpose albeit within a highly stratified society (Hennessey Citation2006; Kynaston Citation2007, Citation2009). There was a tendency of deferential trust in expertise, closed and secretive institutions and high expectation from technological innovations (Falk Citation1982; Camilleri Citation1984; Pringle and Spigelman Citation1982). The dangers of nuclear energy were unrecognised, discounted or undisclosed (for example, the reactor fire at Windscale in 1957) and radioactive waste was a non-problem and either left on sites or dumped in the ocean. Throughout this period the geography of the nuclear industry was being established as new nuclear power stations and reprocessing works were developed around Britain. There was, even then, sufficient concern about the risks for peripheral locations to be chosen. They were relatively remote places and pragmatically sited on land in friendly (public) ownership (Openshaw et al. Citation1989). The nuclear industry was essentially a state activity and civil society was dormant in terms of the nuclear issue especially in the early years. Power was firmly in the hands of government and the nuclear industry.

By the 1960s, however, environmental and peace groups had begun to grapple with the nuclear question, mobilising protests and demonstrations in many countries, at first against nuclear weapons deployment and later against the construction of power plants, before their attention became focused during the 1980s on reprocessing and nuclear waste facilities. The trend in civil society towards greater dissent, conflict and civil disobedience was reflected in terms of nuclear energy in a fundamental shift to a Discourse of Danger and Distrust. From the 1970s on there emerged a distrust of experts, concerns about impacts on health and environment and fears about accidents (inspired by Three Mile Island in 1979 and culminating in Chernobyl in 1986) (Gofman and Tamplin Citation1979). Opposition to nuclear combined with its commercial uncompetitiveness halted its expansion and several countries stopped further development or abandoned it altogether. In the UK, conflicts over nuclear developments, including new power stations (Sizewell B, Hinkley Point C), over nuclear waste sites (in Eastern England), over reprocessing facilities (THORP - Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant at Sellafield) and, ultimately, over the underground laboratory at Sellafield indicated a nuclear industry in retreat and the growing power of anti-nuclear interests (Patterson Citation1985; O'Riordan et al. Citation1988; Ince Citation1984; Blowers et al. Citation1991; Hinchliffe and Blowers Citation2003). Attempts to site radioactive waste facilities relied on the decide announce defend (DAD) approach and were rebuffed by opponents demanding a more open, participative and inclusive approach to decision making. Thus, it proved impossible to find new locations and the industry remained locked into its existing sites. This was a period in which civil society movements achieved growing significance and the balance of power tilted towards them.

Eventually, towards the end of the last century, this turbulent period subsided and a more tranquil, though short, Discourse of Consensus and Cooperation emerged. The Cold War had ended, the memory of major accidents was fading and there was little prospect, it seemed, of a revival of the nuclear industry. This relatively peaceful political environment encouraged a coming together of hitherto opposing interests to seek a solution to the outstanding problem of the nuclear industry, the long-term management of its legacy of radioactive waste. For a while, it seemed, power relations were more evenly balanced. A transition towards more open government encouraged an emphasis on public involvement and engagement in decision making.

The transition to this new discourse was marked by the spectacular failure of the nuclear waste management company (Nirex) in 1997 to secure permission for an underground research laboratory at Sellafield. This precipitated a decisive shift towards a new approach based on the need to inspire public confidence in decisions on long-term management. It led to the setting up by government of the Managing Radioactive Waste Safely (MRWS) process and the appointment of the Committee on Radioactive Waste Management (CoRWM). The Committee embraced an open and deliberative approach in which it combined four knowledge streams to reach a set of linked recommendations that might ultimately lead to the development of a geological disposal facility for long-lived wastes (CoRWM Citation2006; see also Lehtonen in this volume). The knowledge streams were: a detailed scientific assessment (a multi-attribute decision analysis or MADA) of options; an extensive and continuous programme of Public and Stakeholder Engagement (PSE) leading to option appraisal; incorporation of ideas and approaches based on experience overseas; and the use of ethical perspectives to explore the social and environmental implications of different approaches (CoRWM Citation2007a). Finding a site or sites for radioactive waste facilities was envisaged as a staged process based on volunteerism incorporating the principles of participation, partnership and community packages to enhance equity and well-being (CoRWM Citation2007b). Although, in principle, any community could express a willingness to participate in the siting process, it was likely that interest would be confined to nuclear communities which could expect at least some benefit for hosting a facility. Indeed, CoRWM took it as axiomatic that “the well-being of potential host communities will be enhanced in both the short and longer term” (2007b, p. 13). By well-being is meant “those aspects of living which contribute to the community sense of identity, development and positive self-image” (ibid, p. 12) which might, of course, be facilitated by forms of material compensation. Unsurprisingly, the first expressions of interest came from West Cumbria where Sellafield hosts around two-thirds of the UK's inventory of radioactive wastes. While the voluntary approach opened up the prospect of finding a site, it was by no means clear that a site would prove ultimately acceptable on scientific and social grounds.

New discourse, new nuclear

During the early years of the new century, a quite different nuclear discourse has been developing, a Discourse of Security. It is clearly related to a global discourse of “Securitisation” (Aradau Citation2009). The language of this global discourse is belligerent, expressed in such terms as the “war on terror” following 9/11. Apart from terrorism, the concern with security has various other manifestations, including fears about economic security (especially following global recession), energy security (related to fears about “peak oil” and threats to gas supplies) and environmental security (with climate change the overwhelming issue). Securitisation links together these various threats, “Indeed climate change and terrorism compete in terms of which represents the greater threat to established patterns of western life, with energy security having emerged as the key concern connecting the two” (Blűhdorn and Welsh Citation2007, p. 188). In this context nuclear energy has been reborn as a secure and low-carbon answer to both the threat of energy security and climate change.

This new nuclear discourse has introduced, or rather reintroduced, processes of policy making that refer back to earlier periods. The style of governance is less inclusive and participative, in many ways reverting back to some of the characteristics of what Dryzek et al. (Citation2003) describe as the “actively exclusive state” that had been prevalent in the UK until the early 1990s. While environmental movements are not entirely excluded from participation in decision making there is little doubt that the inclusion they recently enjoyed has been waning. They may be co-opted to facilitate legitimation of nuclear policy rather than to co-operate in finding acceptable solutions. The so-called “deliberative turn” with its emphasis on engagement, dialogue and involvement in decision making (Dryzek Citation2000; Goodin Citation2003; Smith Citation2003) appears to have been an exceptional rather than transformative moment before a return towards more formalised, routine consultation and a centralised process which marginalises more effective participation of local government and local communities.

This discursive shift is evident in decision making for new nuclear power stations in the UK. The predetermined focus on existing (peripheral) sites from the outset is redolent of the discredited DAD approach to site selection. Although there remains an emphasis on participation, the form it takes is determined by government, often implemented by the nuclear industry and provides for limited and passive response to consultations without any real attempt at in-depth PSE. There is strict adherence to a relentless and bewildering timetable of parallel consultative processes designed to achieve legitimation by the fastest possible route. The process is tightly controlled by government and debate is curtailed or avoided altogether by a relatively closed process. For example, the SAA criteria were devised by government advised by consultants with no input from local environmental groups, councils or communities (BERR Citation2008b). Responses to the consultation, many of them heavily critical, were not openly considered by government and very few changes were made to the revised criteria (DECC Citation2009a). Subsequent consultations, first on the nomination of sites, then on the draft NPSs (DECC Citation2009b,Citationc,Citationd) for nuclear energy were heavily criticised for being too hurried, burdensome, inaccessible and weighted in favour of nuclear expansion at the expense of environmental and local community interests (BANNG Citation2010b; Greenpeace Citation2010a; House of Commons and Climate Change Committee 2010; Nuclear Consultation Group 2010a). Running in parallel was the consultation on the NIA's application to justify new nuclear power stations (DECC Citation2008b). Here, too, consultation was restricted. Although the issue of justification is of fundamental importance in considering whether the UK should embark on a new fleet of nuclear reactors, as presented the process is narrowly technical, complex and not easily accessible to widespread PSE. The process is largely conducted and controlled within government with the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change acting as the Justifying Authority and therefore being both judge and jury in the case (Nuclear Consultation Group Citation2009, Citation2010b; Greenpeace Citation2010b). As might be expected, the Secretary of State found that the potential benefits of new nuclear power station designs outweighed the potential health detriments and therefore he proposed to justify them (DECC Citation2009e). Moreover, the Justification decision is likely to be made before other co-dependent processes, notably the generic design assessment (undertaken by the regulatory authorities to assess the acceptability of specific reactor designs) are completed.

Further evidence of the shift to a new more pronuclear and less participative discourse is the introduction of an accelerated planning process for infrastructures which has been explicitly designed to put through proposals without the need for lengthy local planning inquiries. Furthermore, local and national democratic accountability has been severely limited by the introduction of an Infrastructure Planning Commission (IPC) originally envisaged as a decision making body but, following the election of the Coalition Government, a body which makes recommendations on development proposals to the relevant Secretary of State. In the case of nuclear power plants Commissioners of the IPC will examine the evidence using the NPSs as a framework. The framework provides strong guidance to the IPC to use the 10 listed sites “to allow nuclear to contribute as much as possible” to meeting the need for new generating capacity by 2025. The framework suggests that where necessary the concept of Imperative Reasons of Overriding Public Interest (IROPI) should be invoked to give priority to nuclear over other considerations (DECC Citation2009b). By these means, then, government has made a quite deliberate effort to avoid delay or disturbance to its nuclear programme.

As the discourse of security has deepened so it has emboldened government in alliance with nuclear interests to press for new build on or near existing nuclear sites. Once again, as in the early years of the nuclear industry, these sites have been seized for mainly pragmatic reasons but which are endorsed by their peripheral characteristics. The process of peripheralisation has reflected the shift of power relations and raises ethical questions concerning equity to which I now turn.

Section 4 – an ethical issue

When framing the siting strategy for new nuclear power, the nuclear industry and government have understandably stressed the production of electricity and the jobs it would create but understated the risks to health and environment arising from releases of radioactivity from the reactors and more especially from the accompanying spent fuel stores and other waste management operations that will remain on site long after electricity production has ceased. This makes political sense in a situation where the vast majority of people, consistently over four-fifths, register concern about radioactive waste (for a detailed analysis of opinion see Eurobarometer 2005). But, looked at from the local community perspective, the imposition of what are in effect long-term high level radioactive waste management facilities may be regarded as unethical and undemocratic.

The undemocratic nature of the process is inherent in the flaws and bias in the site selection process itself and especially in the consultative procedures. These procedures have been so designed and implemented that local communities, local councils and NGOs are at a disadvantage in terms of access to information, ability to respond and to participate in decision making. Moreover, the consultation process is heavily geared towards new nuclear power, not the legacy of wastes it will generate.

There has been little understanding or consideration of the indefinite nature of the commitment. New build raises important ethical questions since it creates inequities both between places (intragenerational) and between generations (intergenerational). Those (peripheral) communities that host new build must bear the burden of risk on behalf of society as a whole without having either an effective say in the process or being effectively compensated. Moreover, the burden persists over time into the far future.

It is conceded by government that onsite interim storage may be required for “around 160 years from the start of the nuclear power stations's operation” (DECC Citation2009b, p. 24). That is, around 60 years operation and 100 years for cooling that the high burn-up spent fuel requires. It is asserted that it is practicable to manage the wastes safely and securely throughout that period. The Government claims that it “is satisfied that effective arrangements will exist to manage and dispose of the waste that will be produced from new nuclear power stations” (DECC Citation2009b, p. 25).

There is, as yet, no final solution in prospect for the management of the wastes arising from new build, so the wastes may remain in store indefinitely. The stores are planned to last for 100 years; beyond that it will be necessary to build new or replacement stores and repackaging and encapsulation will also be required. Even if a repository for permanent emplacement of the wastes is built or regional stores or a central store are opened there will be problems of transportation that have scarcely been tackled. And there may be daughter nuclear plants constructed at the sites thereby lengthening still further the time scales. All in all, it is not inconceivable that new nuclear power stations, waste stores and encapsulation plants on existing sites will maintain a presence for 200 years and beyond.

Meanwhile, some of the sites will be increasingly vulnerable to inundation. The trend in forecasts is towards more frequent and severe weather events and higher sea level rise within the 100-year range than has been initially planned for. Beyond this, uncertainty increases and the combination of worsening climatic conditions and longer time-scales for storage could lead to an unmanageable and dangerous exposure to radioactivity for areas near the new build sites. Furthermore, the proposals transfer the burden and responsibility for the safe management of nuclear sites in potentially difficult circumstances to future generations who may have neither the resources, the institutions, the skills nor the motivation to undertake the task.

Ethically, it may be asked how far into the future does our responsibility extend? One view is that responsibility never ceases: responsibility has to extend “to the potential reach of our actions” (Adam in CoRWM Citation2007a, p. 14). A more pragmatic ethical position recognises that our capacity to affect the future diminishes over time and that at some point in the far future responsibility must necessarily cease. Whichever view is taken, both show a concern for taking responsibility for the long term and this has certainly applied to the management of legacy wastes. But when it comes to new build such concern is much less evident. Given the contrast it is pertinent to put the existential question, Why should we be responsible for the future? The answer to this may seem obvious and uncontentious. It is a requirement, a duty to ensure there is a future presence on the earth and a duty to ensure a worthwhile quality of life. As Hans Jonas puts it, “It is our duty to preserve this physical world in such a state that the condition for that presence remains intact” (Jonas Citation1979, p. 10). Yet, in the case of new build wastes, the needs of the future appear to be neglected in favour of the present urgency to develop nuclear power at existing sites as rapidly as possible. How can this be? This brings us back to the key question posed in the title of this article.

Section 5 – so why dump on us?

The answer, it seems, derives from the transformation in the discourse of nuclear energy discussed earlier. With energy and environmental security as the new dispensation, a rapid deployment of a fleet of new stations is justified to deal with an emerging and imminent energy gap. Moreover, as the peripheralisation thesis demonstrates, there are sites readily available and apparently acceptable at existing nuclear locations. These are peripheral sites, vulnerable both in terms of power relations as well as physically liable to inundation. They are places already living with nuclear risk and facing the prospect of the perpetuation of risk into the far future. They have been selected prematurely, identified as the most favoured sites before the site selection process even began. The listed sites are hapless victims of a set of power relations that place national economic and security interests far above the interests in security and safety of local communities or those of future generations.

The development of nuclear power at existing sites is unfair for two fundamental reasons. One is that it imposes a burden of risk on peripheral communities, least able to resist, offered neither compensation nor effective participation in decision making. The other is that it imposes a burden of risk on generations in the far future who must take responsibility for managing, in deteriorating conditions, the residue of an industry from which they derive no benefits.

The siting process for new nuclear stations is particularly unfair when compared to the parallel process for siting radioactive waste management facilities for legacy wastes, the so-called MRWS process derived from the recommendations of CoRWM (outlined earlier) and adopted in large measure by government (Defra Citation2008). This process has two fundamental tenets. One is that any site chosen for a potential deep repository must be scientifically acceptable and subject to rigorous scientific research to determine its safety. The other tenet is that any site chosen must be acceptable to the potential host community. Moreover this acceptability is provisional since the community volunteers to participate in a siting process from which it may withdraw up to a pre-defined stage in the process (CoRWM Citation2007b, p. 58). Of course, this process has yet to be fully tested and, no doubt, it is possible that powerful interests may take a rather more short-term view of the balance between material benefit and long-term safety considerations. But the point is that the principles applied to legacy wastes should be equally applicable to new build. Although there is ultimately an intention to remove the spent fuel from the new build sites, it may not happen for a very long time, if ever. So, it may be argued that, in principle, there is little difference between finding a site for a repository for the long-term management of legacy wastes and finding a site for long-term storage of new build wastes. In either case it will be necessary to store wastes somewhere for a very long time, certainly beyond the foreseeable future. It may be argued on ethical grounds that any community where it is intended to store spent fuel for an indeterminate period should be asked if it is willing to accept (for the present and on behalf of future generations) the burden and, if so, under what conditions of involvement and withdrawal.

In a little-remarked passage in its implementation report, CoRWM considered this issue.

“It is clear that CoRWM's recommendations on implementation must be applied at least to new central or major regional stores at new locations if CoRWM's recommendations are to inspire public confidence. The extent to which they should be applied to other new stores and existing stores is a matter for further consideration” (ibid, p. 10).

This idea resonates with CoRWM's view that any assessment of new build wastes “should build on the CoRWM process, and will need to consider a range of issues including the social, political and ethical issues of a deliberate decision to create new nuclear wastes” (CoRWM Citation2006, p. 14). Predictably there is silence on the Government's part on these ideas. A likely scenario might suggest that the process for finding a repository for legacy wastes will, increasingly as time goes by, also include new build wastes despite the different issues they raise. Further, that process will be used to signify that a solution has been found sufficient to remove the issue of waste management as an impediment to the further development of the nuclear industry. Under this scenario, communities around sites for new nuclear power stations will have no effective say in the decision to store wastes on site and it will be assumed that these wastes will remain on site indefinitely or until a national repository becomes available to receive them. By such deceptive legerdemain new nuclear sites will become de facto hosts for the long-term management of spent fuel and other long-lived nuclear wastes.

The policy for managing legacy wastes has all the hallmarks of the discourse of consensus and cooperation. It is voluntary and encourages potential host communities to participate in open decision making and partnership. By contrast, the management of new build wastes perfectly expresses the new dispensation of a discourse of security. The wastes are imposed on communities who have no effective say in the matter by government and industry acting in a powerful combination with centralised powers in a relatively closed decision making process in which consultation is really a legitimation function.

In the scheme of things, the sacrifice of a few communities to the broader purpose of meeting energy needs and saving the planet may seem unfair but defensible. But their sacrifice may be in vain. However quickly the new stations are built they are likely to be too little and too late to help with problems of energy security and climate change. The contribution of a replacement fleet of nuclear stations, in the Government's estimation, is likely to save between 5% and 12% of carbon emissions per year (BERR Citation2008a, p. 52) and produce around a third of the country's electricity. Other estimates put a lower figure, as little as 4% (Sustainable Development Commission Citation2006). Although the potential contribution is useful it will not begin until around 2020 and beyond. But, there is little evidence to suggest that the nuclear industry will deliver such a large fleet on time and within budget. Past experience indicates that costs will overrun and delays will occur and the UK may end up with a mere handful of stations. Rather than embark on a programme that may turn out to be a fantasy it would be more prudent to give much greater priority to achieving energy and environmental goals through a viable alternative strategy with energy conservation and renewables at its core.

Instead, the way policy is developing, the UK may by 2020 see a handful at most of existing sites with new nuclear power stations, all that is achieved from the nuclear renaissance. For the communities around these sites there will be no compensation for enduring the dangers and risks of an unnecessary and failed policy. A century and more later those sites, inactive but still radioactive, and quite possibly inundated, will, like the scattered remains of the statue of Ozymandias, king of kings, bear a lonely testimony to the passing triumphs of a former age.

“Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

(Shelley, Ozymandias)

Notes

1. In the original list seismic risk and capable faulting were exclusionary but were subsequently classed as ‘flag for local consideration’. Proximity to military activities remained classed as both exclusionary and discretionary.

References

- Aradau , C . 2009 . “ Climate emergency: is securitisation the way forward? ” . In A warming world. DU311 Earth in Crisis , Edited by: Humphreys , D and Blowers , A . 1165 – 1205 . Milton Keynes : The Open University .

- Atkins . 2009 . A consideration of alternative sites to those nominated as part of the Government's strategic siting assessment process fore new nuclear power stations M.Sc. in Environmental Technology, Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College, London, for DECC

- BANNG (Blackwater Against New Nuclear Group) [Internet] . 2008 . Consultation on the strategic siting assessment process and siting criteria for new nuclear power stations in the UK November 9; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: banng.org.uk

- BANNG (Blackwater Against New Nuclear Group) [Internet] . 2009 . ‘Have Your Say’ government consultation on nomination of sites for new nuclear power stations May 14; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: banng.org.uk

- BANNG (Blackwater Against New Nuclear Group) [Internet] . 2010a . Consultation on Draft National Policy Statements for energy infrastructure 22 February; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: banng.org.uk

- BANNG (Blackwater Against New Nuclear Group) [Internet] . 2010b . House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee, inquiry into energy policy statements January 17; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: banng.org.uk

- BERR (Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform) . 2008a . Meeting the energy challenge: a white paper on nuclear power , London : TSO .

- BERR . 2008b . Towards a nuclear national policy statement: consultation on the strategic siting assessment process and siting criteria for new nuclear power stations in the UK , London : BERR .

- Blowers , A and Leroy , P . 1994 . Power, politics and environmental inequality: a theoretical and empirical analysis of the process of peripheralisation . Environ Politics , 3 ( 2 ) : 197 – 228 . Reprinted in Stephen et al. 2006

- Blowers , A and Lowry , D . 1997 . Nuclear conflict in Germany: the wider context . Environ Politics , 6 : 148 – 155 .

- Blowers , A , Lowry , D and Solomon , B . 1991 . The international politics of nuclear waste , London : Macmillan .

- Blűhdorn , I and Welsh , I . 2007 . Eco-politics beyond the paradigm of sustainability: a conceptual framework and research agenda . Environ Politics , 16 ( 2 ) : 185 – 205 .

- British Energy . 2008 . New nuclear power stations in the UK Consultation leaflet

- Camilleri , J . 1984 . The state and nuclear power , Brighton : Wheatsheaf Books .

- Carter , L . 1987 . Nuclear imperatives and public trust , Washington : Resources for the Future .

- CoRWM (Committee on Radioactive Waste management) . 2006 . Managing our radioactive waste safely: CoRWM's recommendations to government , London : CoRWM .

- CoRWM . 2007a . Ethics and decision making for radioactive waste , London : CoRWM .

- CoRWM . 2007b . Moving forward: CoRWM's proposals for implementation. CoRWM Document 1703 , London : CoRWM . February

- DECC (Department for Energy and Climate Change) . 2008a . The justification of practices involving ionising radiation regulations 2004: Consultation on the Nuclear Industry Association's application to justify new nuclear power stations. Vol. 2. Appendix B: Copy of the Application , London : DECC .

- DECC . 2008b . The justification of practices involving ionising radiation regulations 2004: consultation on the Nuclear Industry Association's application to justify new nuclear power stations , Vol. 1 , London : DECC . Vol. 1: Consultation Document, December, London, DECC

- DECC . 2009a . Towards a National Nuclear Policy Statement: Government response to consultations on the Strategic Siting Assessment process and siting criteria for new nuclear power stations in the UK; and to the study on the potential environmental and sustainability effects of applying the criteria , London : DECC . Office for Nuclear Development, January, London, DECC

- DECC . 2009b . Draft national policy statement for nuclear power generation (EN-6) , London : TSO .

- DECC . 2009c . Consultation on draft national policy statements for energy infrastructure , London : DECC .

- DECC . 2009d . Draft overarching national policy statement for energy (EN-1) , London : TSO .

- DECC . 2009e . The justification of practices involving ionising radiation regulations 2004: consultation on the secretary of state's proposed decisions as justifying authority on the regulatory justification of the new nuclear power station designs currently known as the AP1000 and the EPR. Volumes 1 and 2 , London : DECC .

- DECC . 2009f . Appraisal of sustainability: site report for Bradwell Supplement to draft national policy statement on nuclear power generation (EN-6), London, DECC, November

- Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) . 2008 . Managing our radioactive waste safely: a framework for implementing geological disposal, Cm 7386 , London : TSO .

- Dryzek , J . 2000 . Deliberative democracy and beyond, liberals, critics, contestations , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Dryzek , J , Downes , D , Hunold , C , Schlosberg , D and Hernes , H-K. 2003 . Green states and social movements: environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Norway , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry) . May 2007 . The role of nuclear power in a low carbon UK economy , May , London : DTI . Consultation document

- Eurobarometer . 2005 . Radioactive waste , European Commission . Special Eurobarometer 227 – Report

- Falk , J . 1982 . Global fission , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Gofman , J and Tamplin , A . 1979 . Poisoned power , Emmaus , PA : Rodale Press .

- Goodin , R . 2003 . Reflective democracy , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Greenpeace [Internet] . 2010a . Greenpeace submission to the consultation on the draft national policy statements for energy infrastructure; cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: www.greenpeace.co.uk

- Greenpeace [Internet] . 2010b . Greenpeace submission to the proposed regulatory justification decisions on new nuclear power station: consultation document; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: www.greenpeace.co.uk

- Hajer , M . 1995 . The politics of environmental discourse , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Hennessey , P . 2006 . Having it so good: Britain in the fifties , London : Penguin Books .

- Hinchliffe , S and Blowers , A . 2003 . “ Environmental responses: radioactive risks and uncertainty ” . In Environmental responses , Edited by: Blowers , A and Hinchliffe , S . 7 – 50 . Milton Keynes : Wiley and The Open University .

- House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee . 2010 . The proposals for national policy statements on energy. Third Report of Session 2009–10 , Vol. 1 and 2 , London : TSO .

- Ince , M . 1984 . Sizewell report , London : Pluto Press .

- Jonas , H . 1984 [1979] . The imperative of responsibility , Chicago , IL : University of Chicago Press .

- Kynaston , D . 2007 . Austerity Britain 1945–51 , London : Bloomsbury Publishing .

- Kynaston , D . 2009 . Family Britain 1951–57 , London : Bloomsbury Publishing .

- Leroy , P and Verhagen , K . 2003 . “ Environmental politics: society's capacity for political response ” . In Environmental responses , Edited by: Blowers , A and Hinchliffe , S . 143 – 184 . Milton Keynes : Wiley and The Open University .

- Mays , C . 2005 . “ Where does it go? siting methods and social representations of radioactive waste management in France ” . In Facility siting: risk, power and identity in land-use planning , Edited by: Boholm , A and Löfstedt , R . 21 – 43 . London : Earthscan .

- Nuclear Consultation Group (NCG) [Internet] . 2009 . Consultation on the Nuclear Industry Association's application to justify new nuclear power stations Response from the Nuclear consultation Group; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: www.nuclear consult.org

- Nuclear Consultation Group (NCG) [Internet] . 2010a . Consultation on draft national policy statements for energy infrastructure February 19; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: www.nuclearconsult.org

- Nuclear Consultation Group (NCG) [Internet] . 2010b . Justification of practices involving ionising radiation regulations 2004: Consultation on the Secretary of state's proposed decisions as justifying authority on the regulatory justification of the new nuclear power station designs currently known as AP1000 and the EPR Response from the NCG; [cited 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: www.nuclearconsult.org

- Openshaw , S , Carver , S and Fernie , J . 1989 . Britain's nuclear waste: safety and siting , London : Belhaven Press .

- O'Riordan , T , Kemp , R and Purdue , M . 1988 . Sizewell B, anatomy of the inquiry , London : Macmillan .

- Patterson , W . 1985 . Going critical, an unofficial history of British nuclear power , London : Paladin .

- Pidgeon , N , Henwood , K , Parkhil , K , Venables , D and Simmons , P . 2008 . Living with nuclear power in Britain: a mixed-methods study Cardiff University and University of East Anglia. ESRC Social Contexts and Responses to Risk (SCARR) Research Report, School of Psychology, Cardiff

- Pringle , P and Spigelman , J . 1982 . The nuclear barons , London : Sphere Books .

- Smith , G . 2003 . Deliberative democracy and the environment , London : Routledge .

- Stephen , H , Barry , J and Dobson , A editors . 2006 . Contemporary environmental politics: from margins to mainstream , 203 – 230 . London : Routledge .

- Sustainable Development Commission [Internet] . 2006 . Is nuclear the answer? London; cited 2010 Aug 20. Available from: www.sd-commission.org.uk