ABSTRACT

Climate change is becoming a defining factor for communities in South Asia. Forming one-fifth of the world population, the region increasingly faces climate-induced disasters such as floods, droughts, heatwaves, cyclones etc. This region also has one of the world’s poorest people who struggle to cope with the rapidly changing climatic conditions. Agriculture still employs many people in the region, one of the worst-hit sectors. Agriculture will become untenable in some parts of the region due to climate change. Monsoon patterns have changed, and agriculture does not guarantee sustainable income for the vast majority. Many climate change adaptations have been initiated in the region in response to the threat of climate change. Scholars and practitioners feel that these adaptations must be transformative to be effective. In this paper, we examine eight such adaptations from three South Asian Countries – Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, from the lens of transformative adaptation. We found that no single adaptation initiative meets all the criteria for sustainable socio-ecological transformations. However, there is a significant overlap between different typologies of transformation as envisaged in the paper and literature. We conclude that the concept of socio-ecological transformation is new for South Asia, so integrating it into the programmes and policies is the need of the hour.

1. Introduction

The impact of human activity on global climate has been determined, with a high confidence level, by various reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other scientific literature. According to IPCC’s special report on global warming of 1.5 degrees, anthropogenic activities already caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels in 2018, with a likely range of 0.8°C to 1.2°C (IPCC Citation2018). The report’s projection shows it is expected to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if the emissions continue at the 2018 rate (IPCC Citation2018). The impacts of climate change are bound to pose significant challenges to human civilizations and natural systems over the next few decades and centuries if these worsening trends continue (Allen et al. Citation2018). The frequency of disaster events such as drought, floods, and other extreme events is already increasing, causing disruptions in people’s lives and livelihoods worldwide (Allen et al. Citation2018). Chapter 3 of the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC shows that the populations dwelling in less developed regions are more vulnerable than others (Hoegh-Guldberg et al. Citation2018). There are asymmetries related to contribution to the problem, impacts of climate change, adaptation capacities, and capability to respond to future climatic threats (Hoegh-Guldberg et al. Citation2018)-one of the regions where this is most evident is South Asia. Chapter 24 of the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC, which deals with the impacts of climate change on Asia, points out that South Asian countries, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are among the climate change “hotspots”, where risks arising from changing climate translates to threats to food security, public health, migration patterns etc. over the coming decades (Hijioka et al. Citation2014). The IPCC’s sixth assessment report released in 2022, in chapter 18, says that adaptation has progressed across many sectors, regions etc. However, the adaptation is spread unevenly, with a gap between adaptation and climate risks & vulnerabilities (Schipper et al., Citation2022). Lower-income populations have been highlighted as the group most affected by the global adaptation gap – which is set to increase at current rates (Schipper et al., Citation2022). The latest IPCC report says that a lot of the adaptation undertaken in response to climate change is made, keeping in mind short-term climatic risks at the cost of transformational adaptation (Schipper et al., Citation2022). This is the gap that the paper intends to explore using the agricultural sector in South Asia. The IPCC report highlights that integrated, multi-sectoral adaptation initiatives are needed to address the adaptation gap and resulting inequities and responses based on climatic risks, which will improve food security and nutrition issues (Schipper et al., Citation2022). Through case studies from South Asia, the paper will study transformation adaptations that could address the current adaptation gap.

South Asia’s agricultural sector is one of the most vulnerable, and the effects of climate change are expected to exacerbate the situation (Kaur and Kaur Citation2018; Aryal et al. Citation2019; Goodrich et al. Citation2019). Agriculture employs one of the latest numbers of people in South Asia, including female employment (Joshi et al. Citation2004; Rao et al. Citation2019; Najeeb et al. Citation2020). Women agriculturists employ strategies and use their “agency” to cope with a rapidly changing climate (Rao et al. Citation2019). In this paper, we examine the impacts of climate change on different agricultural practices across other countries (Dilling et al. Citation2019) beyond different contexts and in the context of the socio-ecological transformations undertaken by communities in South Asia. The paper aims to identify what kinds of transformations are being undertaken and how these transformations are helping communities in dealing with environmental changes. The paper analyses the different levels at which transformational adaptation occurs to derive lessons for similar regional situations. The paper used grounded theory, a staple of qualitative studies, as Berlin (Citation1996) describes as “production-based” and “culture-as-lived activities” studies. Grounded theory is used in this paper because the literature on transformational adaptation is still nascent. The grounded theory methodology will allow us to discover the theory from data (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). The data for the study has been gathered through a rapid review of cases to identify adaptations, and evidence from the cases was synthesized. Case selection was made with the following criteria – innovative methods and pilot projects in the agriculture sector in South Asia which were done keeping in mind future climate risks. A rapid review was chosen due to time and resource constraints. Further, once the case studies were selected, using the case study method, this paper studied eight cases from different countries in South Asia. Using the eight cases as a database based on different scales of change is derived, namely, governance and policy transformations, economic transformations, technological transformations, social transformations, and behavioural shifts. The cases studied in the paper fall into one or more of these categories. Transformational adaptations usually operate on one or more scales of change to create truly “sustainable transformations” (Lonsdale et al. Citation2015).

This paper is divided into six sections. Following the introduction, section two provides details of the methodology used in the paper. Section three outlines the definitional challenges and frameworks for transformational adaptation as described in the literature. Section three delves deeper into the five typologies of transformations and the case studies that fall into the different categories of transformations. It shows how socio-ecological transformations are occurring in the region and its typology. Section four provides the details of the cases and analyses them from the transformation lens in the region. Lastly, the paper concludes with implications of the different transformational adaptations in the region. It also discusses what it means for future adaptation to climate change in South Asia.

2. Methodology

This paper uses the qualitative approach called grounded theory methodology to review the socio-ecological transformation cases in South Asia’s agriculture sector. The grounded theory methodology is apt for this study because the theory is being discovered through the data. After all, the literature on transformational adaptation, as mentioned, is still at a nascent stage, especially in South Asia (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Secondly, the grounded theory is apt because of the results, and the theory is traceable to the data that gives rise to it (Neff, Citation1998). Establishing a theory on what types and extent of transformational adaptation is essential to study. Since there is not an existing, prevailing theory on transformational adaptation in the literature, especially in South Asia, the data must lead to the discovery of the theory (even if temporary). In grounded theory, data are examined for dimensions and properties to compare them to similar phenomena (Neff, 1998). The data are regrouped and reconceptualized until at least a provisional theory emerges (Neff, 1998). This paper intends to do that precisely; the dimensions or typology of transformational adaptations and the properties of the adaptation are being captured in the case studies to present a provisional theory on transformational adaptation which applies to the agricultural sector in South Asia. The grounded theory methodology aims to produce a theory where relationships can be found between concepts of a set of concepts (Strauss & Corbin,Citation1990). The grounded theory methodology examines relationships between concepts and sets of concepts (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1994). In this study, the methodology is used to identify the concepts of transformational adaptation, namely, the scale of transformation and the relationship with adaptations to climate risks in the agricultural sector in South Asia. The aim of this study is that it will lead to a finding that are rooted in the cases, which will produce a theory that is both fluid and provisional.

Case studies are used to provide a detailed analysis of the transformational adaptation processes in the agriculture sector in South Asia. A case study is a research design that investigates a particular phenomenon in-depth within its real-life context (Yin Citation2018). The case study approach allows for a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the phenomenon under investigation, as it is based on examining multiple sources of evidence, including interviews, observation, and documentation (Yin Citation2018).

The use of the grounded theory methodology and case studies is particularly appropriate in this study because it allows for the development of a provisional theory based on the real-life experiences of farmers and practitioners in the agriculture sector in South Asia. This approach is well-suited to address the research question of this study, which seeks to identify the typology of transformational adaptations in the agricultural sector in South Asia. Using grounded theory methodology and case studies allows for a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation and the development of a provisional theory that can inform future research and policy development.

Also, the case study transformation processes have veered away from well-managed, inclusive strategies built on foresight and ongoing learning (Vermeulen et al. Citation2018). The qualitative case study method has been increasingly used in fields where large-scale information is unavailable for knowing the trends or changes in the sector, such as agriculture (Assan et al. Citation2018). This study also follows the tradition of bottom-up approaches to research, which is better suited to the research question we have asked for this paper (Sabatier Citation1986; Conway et al. Citation2019; Ostermann‐Miyashita et al. Citation2021). Therefore, we have refrained from giving any framework and trying to see if the cases are suiting the same Instead, we have let the framework evolve via the case studies themselves.

3. Socio-ecological transformations and frameworks

3.1. Definitional ambiguity

Transformational adaptation has a rather vague definition in the literature but is often juxtaposed and contrasted with “incremental transformation”. Lonsdale et al. (Citation2015) define transformational adaptation as consisting of three characteristics, namely, [i] a system-wide change or changes beyond one system, [ii] a focus on the forthcoming and prolonged changes; and [iii] a direct investigation of the efficacy of current systems, social injustices, and proven disparities and inequalities. Others have defined transformation as the capacity to move from the existing or conventional system to a new or different system (Folke et al. Citation2010). Folke et al. (Citation2010) also coined transformative capacity as the ability to introduce “untried beginnings” in response to untenable social, ecological, and economic conditions. Kates et al. (Citation2012) define transformational adaptation as an adaptation that is unseen or new to a particular region with the capacity to transform places. Tschakert and Dietrich (Citation2010) further differentiate between transformative adaption (where adaptation leads to transformation) and transformational adaptation (where adaptation is the transformation).

However, in the literature, there seems to be some ambiguity regarding where incremental adaptations end and transformational adaptations begin (Nelson et al. Citation2007). A study on the differing definitions of transformational change found that incremental and transformational adaptations are not individually seen as a single strategy. Instead, they are both viewed as several robust processes in response to significant changes that are anticipated or in reaction to (Lonsdale et al. Citation2015). Mochain et al. (Citation2019) say that transformational change can occur when there is a recognition that incremental adaptations often fall short of the scale of the threat presented by climate change and developmental issues. Incremental adaptation should work alongside long-term strategic adaptation, thus enabling transformations (Mochain et al. Citation2019). Some definitions further state that such transformational changes can respond to climatic or non-climatic issues (Nelson et al. Citation2007). Lastly, a debate is ongoing in the literature on which leads to which – adaptation to transformation or whether societal transformation leads to adaptation. Therefore extra efforts are not required (Lonsdale et al. Citation2015).

3.2. Scales of transformation

One of the themes that emerge from the literature and research in transformational adaptation is “scales of change” (Lonsdale et al. Citation2015). The literature suggests that transformations occur at different levels, such as economy, governance, technology etc. However, for the transformations to become sustainable, the adaptations have to touch on more than one of the scales of change (Lonsdale et al. Citation2015). Similarly, transformative capacity usually involves new technologies, governance-related reforms, and shifts from conventional practices and culture (O’Brien Citation2011). It is this framework that the paper seeks to build on. The idea is that socio-ecological transformations require transformations at different levels to become more entrenched and sustainable, leading to resilience building (Cretney Citation2014). Through case studies in South Asia, the paper aims to analyse how transformations occur at different levels and how sustainable they are. In the next section, the scales of change in the cases from South Asia will be delved into.

4. South Asia and socio-ecological transformations

For this paper, select cases from “South Asia” have been studied to determine the kind of social-ecological transformations. The cases have been selected from the agriculture sector where climate change will make the continuing existing agricultural practices untenable or is anticipated to make them untenable (Lwasa Citation2015). In all the cases selected, the adaptations are prompted by a threat to the status quo due to factors relating to climatic or non-climatic changes. The transformational adaptations are, in some cases, a single strategy that might improve the socio-economic conditions of the communities or could be a suite of adaptation strategies that are required to counteract the effects that climate change may have on the community. In the literature, transformational adaptation has definitional ambiguity; sometimes, these definitions reach a confluence, and at other times, they are disparate (Andrachuk and Armitage Citation2015). This paper attempts to capture what the case studies are trying to tell us about transformational adaptation in South Asia. The report uses 8 cases from different countries, regions, and climatic conditions in South Asia. The cases of transformational adaptations also vary from small-scale adaptations at the single farm level to large-scale adaptations at the state or country level to get the overall experience of transformational adaptations in the region.

Instead of choosing and applying a particular framework to the case studies from South Asia selected in this paper, it would be prudent to let the case studies inform the scale of transformation in the regional context. The selected case studies show transformations of different scales, such as (i) Economic transformation, (ii) Governance and Policy, (iii) Technological adaptation, (iv) Social transformation, and (v) Behavioural shifts. The case studies can simultaneously fall into one or more of these transformation scales. This section of the paper will detail case studies relating to the types of transformations described above.

4.1. Economic transformation

An initiative undertaken in four districts of Bangladesh shows an adaptation that fostered economic transformation for rice paddy farmers. Bangladesh is a developing country in South Asia with a burgeoning population. Due to high population density, agricultural farms are becoming smaller in scale due to land fragmentation. This increases pressure on rice production – a regional staple food (Hossain et al. Citation2005). Adopting measures such as using chemical fertilizers and pesticides is a necessity in present conditions, which gives rise to two issues; firstly, the heavy use of chemicals is harmful to the environment, water sources (consequently animals and people), and soil health (Hossain et al. Citation2005). Secondly, farmers already dealing with small-scale farming are strapped for resources. They cannot purchase the large agrochemical requirement to produce the quantity or quality of rice required in the country (Hossain et al. Citation2005).

As a response to the untenable situation and increasing demand for rice production in Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) introduced the Integrated Rice-Duck Farming (IRDF) initiative to increase the productivity of rice farmers in the four districts selected (Khan et al. Citation2005). The initiative was undertaken in Sylhet, Barisal, Moulvibazar, and Sunamganj districts covering 147 farmers who were identified as resource-poor (Hossain et al. Citation2005). The IRDF system introduces ducks in rice fields to increase yield and income for farmers where duckling of a certain age is presented in the field and removed after a few months (Hossain et al. Citation2005). The system, on average, increased the yield by 20% in the farms where the system was introduced, and net revenue also increased by 50% (Hossain et al. Citation2005). The rice-duck system has been a traditional practice in Japan for generations and other Asian Countries (Khan et al. Citation2005). The system has a positive impact on the yield of rice production, economic gains (increasing rice provisioning ability of farmers and increased revenue), soil health (the result of grazing and duck excreta adding nutrients to the soil), and at the same time, reduced insect population. Weed plants were reduced in some farms where the initiative was undertaken (Hossain et al. Citation2005).

The adaptation borrowed from other countries means there are some downsides, such as the vulnerability of the ducklings to the local climate, which led to duckling mortality being as high as 8–12% (Hossain et al. Citation2005). Despite the drawback, the IRDF was adopted in many countries across Asia in both tropical and sub-tropical countries (Suh Citation2015). Nepal is another country where the IRDF was experimented with as a transformational adaptation to increase rice paddy productivity. The IRDF pilot project was started in Chitwan and Nawalparasi, where farmers saw an increase in rice paddy yield, and their nutritional needs got a boost through duck meat at the same time. The IRDF is an adaptation that has transformed through an untried system in countries where rice production increase is imperative.

4.2. Governance and policy transformation

Climate change is set to significantly impact freshwater resources available in global climate hotspots. As water resources become scarcer, a rainfed agricultural system dependent on annual rainfall will become vulnerable. To deal with this issue, the Government of India introduced the National Innovation on Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) scheme (ICAR Citation2011). Under the scheme, an initiative was undertaken in Nawada village, Bihar (India). Indian agriculture contributes to 67% of livelihoods among the overall working adults in the country (Singh et al. Citation2020). Therefore, it is a crucial sector and one of the most vulnerable to climatic changes. Singh et al. (Citation2020) estimate that most of the negative impacts of climate change on the agriculture sector in India are expected to occur between the years 2010–2039, which is likely to reduce agricultural yield by 4.5% − 9% (a loss of 1.5% of GDP of India annually). It is crucial to increase the climate resilience of the agriculture sector through conversion from rainfed agriculture, which accounts for 58% of the net sown area, to irrigation systems (Singh et al. Citation2020).

Therefore, an initiative was started to ensure assured irrigation as an adaptation by NICRA to transform the agriculture sector in Nawada village in Bihar. The initiative proposed to increase irrigation in the village and reduce the village’s dependence on rainfed agricultural processes. Freshwater resources were developed in Nawada under the scheme to ensure more irrigation, increasing crop yield and making the local community the scheme’s beneficiaries (Singh et al. Citation2020). The government installed six tube wells under the NICRA scheme with submersible pumps catering to 12–15 hectares of the area, which significantly increased the crop intensity of the farms in Nawada village (Singh et al. Citation2020). The transformational adaptation to climate resilience through government policy in Nawada village is a perfect example of governance transformation to adapt to climate change. Implementing the assured irrigation project through government-provided tube wells resulted in savings for the farmers (Singh et al. Citation2020). The farmers of Nawada village saved Rs 1300 per acre per crop cycle, and the assured irrigation project ensuredthree3 crop cycles a year (Singh et al. Citation2020). wheat yield also jumped by 10–15% after the implementation of the project because the more reliable water resources meant that water was available at critical stages of the crop cycle (Singh et al. Citation2020). On average, the farmers of Nawada each saved Rs. 10000 ($ 140) per hectare over three crop cycles, apart from indirect benefits such as the reduction of pollution from diesel pumps used earlier (Singh et al. Citation2020). Similar projects are now being planned in other geographical locations in India under NICRA.

4.3. Technological transformation

New technologies can lead to transformational adaptation to overcome climatic and non-climatic issues. The case of Uber for Tractors is an excellent example of how smallholder farmers are using digital technology to transform how they undertake agricultural mechanization. Smallholder farmers account for approximately 80% of all farmlands worldwide (Khanal et al. Citation2020). On average, smallholder farmers in the developing world are impacted more by relatively fewer resources and revenue (Khanal et al. Citation2020). Technological tools that help smallholder farmers gain access expensive agricultural equipment could reduce their overall cost of farming, and the cost of the ers who are providing service (Daum et al. Citation2021).

EM3 Agri-services India is a service like Uber does for taxi services. The service established “custom hire centres” to expand to a franchise model, where the franchisee’s owners would purchase the machinery. Still, the government would subsidize the purchase value (Daum et al. Citation2021). The case of EM3 operating in Rajasthan shows the extent of the success of the technological transformation that occurred. In the state, 300 custom hire centres were supposed to be opened in 28 of the 32 districts per the agreement reached between EM3 and the state government of Rajasthan (Daum et al. Citation2021). The end of 2019 saw the company establish as many as 275 centres in the state (Daum et al. Citation2021). The result of the technological intervention has been the reduction of transaction costs for the service providers. In contrast, the transaction cost of the service users is less pronounced; however, the users mainly benefit from the supply-side issues in terms of mechanization (Daum et al. Citation2021). The transformation of mechanization in agriculture through technology can be truly unlocked by further digital literacy and increasing coverage (Daum et al. Citation2021). However, the potential for transformation that the EM3 will bring to smallholder farmers in the same way Uber transformed the taxi service for urban users is promising.

4.4. Social transformation

Social transformations are another feature of transformational adaptations. The social transformations, however, can be a positive change by enhancing local knowledge and practices. They can also be a negative social transformation, as shown in two cases from Bangladesh and India. For a case of positive social transformation, we analyse a case from Raydas Bari Char in the Gai Bandha District of Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, the agriculture sector is one of the most vulnerable sectors to climate change and due to its location, the country is likely to face the worse effects of climate change (Ahmed et al. Citation2021). Further, Chars, the local Bengali name for riverine islands, are particularly vulnerable, at the mercy of rivers prone to flooding (Ahmed et al. Citation2021). Chars are essentially sand bars or river islands in the river deltas of Bangladesh. The Raydas Bari Char, like most other char islands, is highly vulnerable to seasonal changes such as floods, droughts, and erosion, which are in perpetual variation (Ahmed et al. Citation2021). The conditions of the Chars constitute a significant issue for the residents of the islands, considering that agriculture is the main occupation of the community (Ahmed et al. Citation2021). The agricultural practices of Char dwellers are also unique considering the soil texture and environmental variability, which, therefore, forces the dwellers to choose a limited number of crops and keep the land fallow during particular seasons such as Kharif (the primary cropping season elsewhere) (Ahmed et al. Citation2021). Environmental or climatic conditions could make the Char dwellers’ livelihoods untenable for agriculture. To counteract the ever-changing conditions, the Raydas Bari Char local communities use a “trial and error knowledge to adapt to these diverse effects of climate change in their situation” (Ahmed et al. Citation2021, p. 7). Studies have suggested that the Char dweller’s adaptations are based on their traditional knowledge, and the adaptations are at the individual level (ILA) and planned adaptations (PA) (Ahmed et al. Citation2021). However, the anticipated climatic changes far exceed their current adaptation. The challenge would be to innovate on to traditional knowledge to produce more practical and effective adaptations that will require further social transformation (Ahmed et al. Citation2021).

As for a case of negative social transformation, we analyse a case of the Contract Farming of Eucalyptus by the paper industry in the State of Odisha, India. In this case, from the Koraput district of Odisha, the twin forces of the corporatization of agriculture for economic benefits and the rise of religious nationalism resulted in women’s agency in agricultural practices being significantly reduced (Mitra and Rao Citation2021). Contract farming of eucalyptus introduced by the paper industry in the district on the Dongar lands or uplands has disrupted women’s control over the cultivation of millets and pulses in these areas (Mitra and Rao Citation2021). The issue of contract farming has also raised another social aspect of the local community whereby, although considered individually owned legally, the land was viewed as a collective “ecological space” (Mitra and Rao Citation2021). The introduction of contract farming has upended this by prioritizing individual interests instead of the community’s common interests (Mitra and Rao Citation2021). The de-collectivization of the ecological spaces has also meant that a few community members benefit from the contract farming practice. In contrast, others are left impoverished (Mitra and Rao Citation2021). Women’s agency has been systematically reduced through contract farming, where their control over labour, revenue, and power to decide on crops and land has been decimated (Mitra and Rao Citation2021). Therefore, contract farming, introduced to foster farmers’ economic transformation in developing countries has led to an undesirable social transformation.

4.5. Behavioural shifts

Transformational adaptation can occur on the level of behavioural change of entire communities to adapt to climate change. This phenomenon can be observed with tea cultivation in Assam, India. Tea is extremely sensitive to global climate change and its various impacts. Climate change is anticipated to impact both the quantity and quality of tea produced and the tea-growing regions are also expected to decline by 40–55% (Baruah and Handique Citation2021. Tea growers will be impacted by diverse climatic impacts such as drought, changing rainfall patterns, and average temperature increases. Given the importance of the industry, it could impact many communities, from owners of plantations down to workers (Baruah & Handique, Citation2021). A case study in Assam’s four main tea growing areas, namely, Upper Assam, South Bank, North Bank, and Cachar, exhibits the behavioural shifts due to transformational adaptations due to climate change (Baruah & Handique, Citation2020).

Tea is a crop that is grown as a rain-fed crop in Assam and, therefore, vulnerable to climatic changes – it is predicted that by 2070, these tea-growing regions will not be able to sustain their livelihoods in most parts of the State (Baruah & Handique, Citation2020). In response to these existential threats, most of the plantations in the state have implemented adaptive measures such as Rainwater Harvesting, Afforestation programs, soil mulching, wind barriers, artificial irrigation, and maintaining biodiversity (Baruah & Handique, Citation2020). These are individual incremental adaptations that all add up to the behavioural changes in the long term, leading to transformational adaptation. Most of the plantations in the state are also planning future adaptations such as plant-tolerant cultivars, awareness and training programs, clean energy, organic manures, and anti-erosion measure (Baruah & Handique, Citation2020). The adaptations are moving away from conventional behaviour in the face of an anticipated untenable situation for most plantations.

5. Transformative adaptation in South Asia: a long way to go

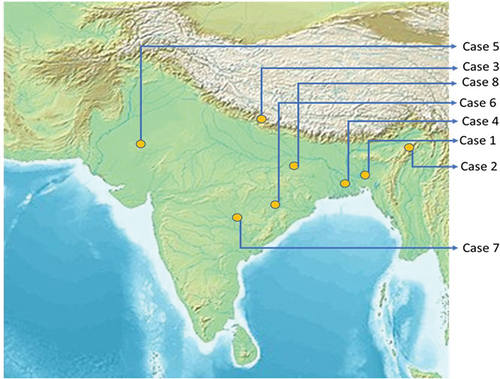

For the paper, eight case studies (n = 8) have been studied and compiled into a database of cases (See for the location of cases from South Asia). The database of cases was compiled through secondary sources to identify unique cases of transformational adaptation in the agricultural sector where climate change is already impacting or is anticipated to have an impact. The cases are all unique and novel adaptations from South Asia, which go beyond simple incremental adaptation and seek to change the status quo or existing way of carrying out agricultural practices. From the cases, the five transformation scales were identifiable: Economic Transformation, Governance and Policy Transformation, Technological Transformation, Social Transformation, and Behavioural shifts.

Figure 1. Case studies from South Asia with Unique Adaptations.

The cases do not, however, fit into one scale in most cases, and often there is an overlap. A technological transformation could aid cases with economic transformation, for example. Refer to for the case database and overlap of types of transformation. As we can see from , most of the case studies can be bucketed into two or more scales of transformations. Six of the eight cases have major behavioural shifts, which depart from conventional practices and fundamentally new ways of carrying on agriculture as Folke et al. (Citation2010) describe the transformation in socio-ecological conditions as the capacity of the communities or individuals to attempt “untried beginnings” in response to undesirable or even untenable ecological, economic, and social issues (Nelson et al. Citation2007; Park et al. Citation2012; Thornton and Comberti Citation2013).

Table 1. Scales of change in transformation cases.

Table 2. Case database.

The two cases that saw technological transformations interestingly did not touch on social transformations, but focused more on economic transformations and behavioural shifts. In the literature, for transformations to be genuinely sustainable and long-lasting, they have to be necessitated by changes on different levels (Lonsdale et al. Citation2015). A combination of scales of change gives the transformations a better chance of sustaining in response to threats such as climate change (Refer to number of scales of change in each case). We see that all the cases have two or more levels of transformation. However, in case 6 (Koraput District, India), one of the changes turned out to be negative in the two cases where there were more than two overlapping transformations. Only in the case of Nawada village (India), where there was a transformational adaptation due to a governance and policy intervention, did the benefits lead to an economic, behavioural, and social transformation. The case of Nawada can be a valuable reference to other communities in the region trying to move from less sustainable agricultural practices to assured irrigation, which has benefits in terms of both increases in yield and cost-saving for farmers.

6. Conclusion

South Asia, home to one-fifth of the world’s population, is reeling under the changes brought about by altering environmental conditions and the climate. Agriculture is one of the sectors worse affected by these changes (Aryal et al. Citation2019). The region is already experiencing climate-induced disasters such as floods, droughts, heatwaves and changing monsoon patterns affecting its economy (Im et al. Citation2017; Ahmed et al. Citation2019). One of the worst affected people is poor and marginalized communities, including women, who derive their daily sustenance from the immediate environment (Yadav and Lal Citation2018). Adaptation is one of the keys to coping with these rapidly changing environmental systems. However, as the latest IPCC assessment report of 2022 points out, the lower-income population group across the world is at the mercy of the uneven distribution of adaptation initiatives to combat climate change. Examples of the effectiveness of adaptation options are very few in South Asia (Merrey et al. Citation2018; Dasgupta et al. Citation2020), leading to a lack of choices for the people. The situation is increasing vulnerabilities, especially for communities below the poverty line and in some of the most environmentally stressed regions (Dilshad et al. Citation2019). It is increasingly felt that adaptation that looks at ‘one-size-fits-all is flawed (Dilling et al. Citation2019), and therefore, systemic transformation is required (Fedele et al. Citation2019).

This paper looks at the concept of transformative adaption from the analyses of eight case studies chosen from three South Asian countries – Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. Using the grounded theory methodology, the cases were analysed to create different scales of change. We looked at governance and policy, economic, technological, social, and behavioural transformations as core ingredients of transformative adaptation. We found that the case studies fall into different categories of transformations but do not comply with all the facets of the revolution. There is also an overlap between different transformation scales, as a neat categorization may not be possible due to integrated systems.

The idea of socio-ecological transformation is recent to the South Asian region. Moving beyond incremental changes is now seen as a necessity in specific circumstances. The Tea plantations in the State of Assam (India), one of the cases studied in this paper, are an excellent example of how transformational changes are a recent development. Tea plantations that have existed for many decades, since the British colonization of India, have to try completely new practices such as using c, lean energy, rainwater harvesting, organic manures, etc., in response to climate change. Climate change is set to reduce the cultivable areas of tea by approximately 40% worldwide, which is an existential threat to tea growers in Assam. They are responding to it by transforming the way they grow tea and transforming the communities depending on the plantations. However, the transformational adaptations in Assam are still not formalized in policy and technological innovations needed to enable sustainable transformations are yet to occur. The cases of technological innovation-aided transformations are similarly limited in that they enable economic transformation but do not touch the other five scales of transformation. In the “Uber for Tractors” case, for example, the technological transformations have direct cost-saving benefits for service providers and indirect benefits for the users. However, many users are still not using the software application developed for this purpose and are still physically going to the service centres. Therefore, showing the need to increase awareness of technological innovation and indicates untapped potential. Only in one of the eight cases do we observe four scales of transformations. In most cases and across the region, there is still some way to go before genuinely sustainable socio-ecological transformations become standard practices in areas where climate change poses an existential threat.

6.1. Areas for future research and action

Understanding that transformational adaption as a concept and practice is in its nascent stage in South Asia, five areas for future research has been identified.

Firstly, there is a need for further research into the effectiveness of different adaptation strategies in South Asia. The text highlights the uneven distribution of adaptation initiatives in the region and the limited examples of effective adaptation options. Therefore, there is a need for more research to identify which strategies are most effective for different communities and environments in South Asia. This research could involve case studies, experimental trials, and comparative analyses to determine which strategies work best and why.

Secondly, there is a need for research into how to support and enable transformative adaptation in South Asia. The text highlights the need for systemic transformation rather than incremental change, but also notes that the necessary policy and technological innovations are yet to occur. Further research is needed to identify how governments, NGOs, and other stakeholders can support transformative adaptation in South Asia, and what kind of policy and technological innovations are needed to enable such transformations. This could involve stakeholder engagement, policy analysis, and technological assessments.

Thirdly, there is a need for research into the socio-economic impacts of transformative adaptation in South Asia. The text highlights the vulnerability of poor and marginalized communities in the region, but also notes that transformative adaptations could have wider economic, social, and behavioural impacts. Further research is needed to identify how transformative adaptations could impact different communities and stakeholders, and how to ensure that the benefits of transformative adaptations are shared equitably.

Fourthly, there is a need for research into the intersection of different scales of transformation in South Asia. The text notes that the cases of transformative adaptation in South Asia fall into different categories of transformations, and that there is an overlap between different transformation scales. Further research is needed to better understand the interplay between different scales of transformation and how to design and implement adaptation strategies that incorporate multiple scales of change.

Finally, there is a need for research into how to scale up and replicate successful transformative adaptations in South Asia. The text notes that many of the successful case studies are still not formalized in policy, and that technological innovations are yet to occur. Further research is needed to identify how to scale up and replicate successful transformative adaptations, and how to ensure that they are integrated into policy and practice. This research could involve knowledge transfer and capacity building, as well as identifying barriers and enablers to scaling up successful adaptations.

6.2. Limitations of the study

The concept of transformation is very new (Vermeulen et al. Citation2018), and South Asia is not an exception. This is precisely why the paper uses the grounded theory methodology as an analytical lens. One of the central aims of the methodology is to discover theory through the data and not to test theory already established. The risk of this methodology lies in the fact that the theory that emerges from the study could be a step in producing a more pronounced and nuanced theory. While the advantage of the grounded theory is that the theory produced, even if provisional, is always traceable to the data – a rapid literature review, as done in this paper, could result in overlooking specific data or case studies. Therefore, the limitation of time and resources to conduct a systematic review of cases from South Asia would be a logical next step.

Secondly, grounded theory methodology relies on finding that are rooted in precise analytical procedures (Neff, 1998). However, the theory produced as a result is not set, permanent or closed. We recognize that the scales of the transformational adaptation framework we have devised in this paper are fluid, open and provisional. It is not encompassing all the cases of transformational adaptation in South Asia. At best, it contributes to the literature on transformational adaptation specific to the agricultural sector in a specific context (South Asia). A more systematic, multi-sectoral study will need to follow the study to establish the scales of the transformation framework presented in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Pranav Prakhyat Garimella has changed affiliation to World Resources Institute India where he currently works as a Program Manager. The author is grateful to the organisation for the time and resources provided to complete the review process and publish the article.

The authors thank the Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business for providing support in terms of time and resources to undertake research and write the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

- Ahmed AU, Appadurai AN, Neelormi S. 2019. Status of climate change adaptation in South Asia region. In: Status of climate change adaptation in Asia and the Pacific. Cham: Springer; pp. pp. 125-–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-99347-8_7.

- Ahmed Z, Guha GS, Shew AM, Alam GMM. 2021. Climate change risk perceptions and agricultural adaptation strategies in vulnerable riverine char islands of Bangladesh. Land Use Policy. 103:103, 105295. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105295.

- Allen MR, Dube OP, Solecki W, Aragón-Durand F, Cramer W, Humphreys S, Kainuma M, Kala J, Mahowald N, Mulugetta Y, et al. 2018. Framing and Context. In: Zhai V,P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, Pirani A, Moufouma-Okia W, Péan C, Pidcock R, Connors S, Matthews JBR, Chen Y, Zhou X, Gomis MI, Lonnoy E, Maycock T, Tignor M, and Waterfield T, editors. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009157940.001.

- Andrachuk M, Armitage D. 2015. Understanding social-ecological change and transformation through community perceptions of system identity. Ecol Soc. 20(4):26. doi: 10.5751/ES-07759-200426.

- Aryal JP, Sapkota TB, Khurana R, Khatri-Chhetri A, Jat ML, Jat ML. 2019. Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: adaptation options in smallholder production systems. Environ Dev Sustain. 22:1–31. doi:10.1007/s10668-019-00414-4.

- Assan E, Suvedi M, Schmitt Olabisi L, Allen A. 2018. Coping with and adapting to climate change: a gender perspective from smallholder farming in Ghana. Environments. 5(8):86. doi: 10.3390/environments5080086.

- Baruah P, Handique G. 2021. Perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in tea plantations of Assam, India. Environ Monit Assess. 193(4):165. doi: 10.1007/s10661-021-08937-y.

- Berlin JA. 1996. Rhetorics, Poetics, and Cultures: Refiguring College English Studies. Refiguring English Studies. Urbana, Ill: National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana.

- Conway D, Nicholls RJ, Brown S, Tebboth MG, Adger WN, Ahmad B, Wester P, Crick F, Lutz AF, De Campos RS. 2019. The need for bottom-up assessments of climate risks and adaptation in climate-sensitive regions. Nat Clim Chang. 9(7):503–511. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0502-0.

- Cretney R. 2014. Resilience for whom? Emerging critical geographies of socio‐ecological resilience. Geography Compass. 8(9):627–640. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12154.

- Dasgupta P, Sahay S, Prakash A, Lutz A. 2020. Cost effective adaptation to flood: sanitation interventions in the Gandak river basin, India. Clim Dev. 12(8):717-–729. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2019.1682490.

- Daum T, Villalba R, Anidi O, Masakhwe M, Gupta S, Birner R. 2021. Uber for tractors? Opportunities and challenges of digital tools for tractor hire in India and Nigeria. World Dev. 144:105480. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105480.

- Dilling L, Prakash A, Zommers Z, Ahmad F, Singh N, de Wit S, Nalau J, Daly M, Bowman K. 2019. Is adaptation success a flawed concept? Nat Clim Chang. 9(8):572–574. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0539-0.

- Dilshad T, Mallick D, Udas PB, Goodrich CG, Prakash A, Gorti G, Rahman A, Anwar MZ, Khandekar N, Hassan SMT. 2019. Growing social vulnerability in the river basins: evidence from the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) Region. Environ Dev. 31:19–33. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2018.12.004.

- Fedele G, Donatti CI, Harvey CA, Hannah L, Hole DG. 2019. Transformative adaptation to climate change for sustainable social-ecological systems. Environ Science & Policy. 101:116–125. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2019.07.001.

- Folke C, Carpenter S, Walker B, Scheffer M, Chapin T, Rockstrom J. 2010. Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol Soc. 15(4):20. doi: 10.5751/ES-03610-150420.

- Glaser, Barney G., Strauss, Anselm L. 1967 The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (United States of America: AldineTransaction) 265 0-202-30260-1

- Goodrich CG, Prakash A, Udas PB. 2019. Gendered vulnerability and adaptation in Hindu-Kush Himalayas: research insights. Environ Dev. 31:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2019.01.001.

- Hijioka Y, Lin E, Pereira JJ, Corlett RT, Cui X, Insarov GE, Lasco RD, Lindgren E, Surjan A. 2014. Asia. In: Barros VR, Field CB, Dokken DJ, Mastrandrea KJ, Mach TE, Chatterjee BM, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR White LL, editors Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: regional Aspects. contribution of working group II to the Fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York: Cambridge University Press; pp. 1327–1370.

- Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jacob D, Taylor M, Bindi M, Brown S, Camilloni I, Diedhiou A, Djalante R, Ebi KL, Engelbrecht F, et al. 2018. Impacts of 1.5ºC global warming on natural and human systems. In: Zhai V,P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, Pirani A, Moufouma-Okia W, Péan C, Pidcock R, Connors S, Matthews JBR, Chen Y, Zhou X, Gomis MI, Lonnoy E, Maycock T, Tignor M, and Waterfield T, editors. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- Hossain ST, Sugimoto H, Ahmed GJU, Islam MR. 2005. Effect of Integrated rice-duck farming on rice yield, farm productivity, and rice-provisioning ability of farmers. Asian J Agric Dev. 2(1):79–86. doi: 10.37801/ajad2005.2.1-2.7.

- ICAR. (2011, February 2). Welcome to NICRA. National innovations in climate resilient agriculture. [Accessed 2021 June 9]. http://www.nicra-icar.in/nicrarevised/index.php/home1.

- Im ES, Pal JS, Eltahir EA. 2017. Deadly heat waves projected in the densely populated agricultural regions of South Asia. Sci Adv. 3(8):e1603322. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603322.

- IPCC. 2018. Summary for Policymakers. In: Zhai V,P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, Pirani A, Moufouma-Okia W, Péan C, Pidcock R, Connors S, Matthews JBR, Chen Y, Zhou X, Gomis MI, Lonnoy E, Maycock T, Tignor M, and Waterfield T editors Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA.

- Joshi PK, Gulati A, Birthal PS, Tewari L. 2004. Agriculture diversification in South Asia: patterns, determinants and policy implications. Econ Polit Weekly. 39(24):2457–2467.

- Kates RW, Travis WR, Wilbanks TJ. 2012. Transformational adaptation when incremental adaptations to climate change are insufficient. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 109(19):7156–7161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115521109.

- Kaur H, Kaur S. 2018. Climate change impact on agriculture and food security in India. J Bus Res. 7:35–62.

- Khan MA, Ahmed G, Magor N, Salahuddin A. 2005. Integrated rice-duck: a new farming system for Bangladesh. In: Mele PV, Salahuddin Ahmad, Magor NP, editors. Innovations in Rural Extension. Dhaka, Bangladesh: CABI Publishing; p. 143–155.

- Khanal U, Clevo W, Rahman S, Boon L, Hoang V (2020). Smallholder Farmers’ adaptation to climate change and its potential contribution to UN’s sustainable development goals of zero hunger and no poverty. MPRA Paper no. 106917. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/106917/

- Lonsdale K, Pringle P, Turner B. 2015. Transformative adaptation: what it is, why it matters & what is needed. UK Climate Impacts Programme. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Lwasa S. 2015. A systematic review of research on climate change adaptation policy and practice in Africa and South Asia deltas. Reg Environ Change. 15(5):815–824. doi: 10.1007/s10113-014-0715-8.

- Magnetto Neff, J. (1998). Grounded theory: A critical research methodology. In C. Farris & C. Anson (), : at the , Under construction: Working at the intersections of composition theory, research, and practice (pp.124–135). Logan, Utah: Utah State UP.

- Merrey DJ, Hussain A, Tamang DD, Thapa B, Prakash A. 2018. Evolving high altitude livelihoods and climate change: a study from Rasuwa District, Nepal. Food Secur. 10(4):1055–1071. doi: 10.1007/s12571-018-0827-y.

- Mitra A, Rao N. 2021. Contract farming, ecological change and the transformations of reciprocal gendered social relations in Eastern India. J Peasant Stud. 48(2):436–457. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2019.1683000.

- Mochain D, Spear D, Ziervogel G, Masundire H, Angula MN, Davies J, Molefe C, Hegga S. 2019. Building transformative capacity in southern Africa: surfacing knowledge and challenges through participatory vulnerability and risk assessment. Action Res. 17(1):19–41. doi: 10.1177/1476750319829205.

- Najeeb F, Morales M, Lopez-Acevedo G. 2020. Analyzing Female Employment Trends in South Asia. Washington: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-9157.

- Nelson DR, Adger WN, Brown K. 2007. Adaptation to environmental change: contributions of a resilience framework. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 32(1):395–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.32.051807.090348.

- O’Brien K. 2011. Responding to environmental change: a new age for human geography? Prog Hum Geogr. 35:542–549. doi:10.1177/0309132510377573.

- Ostermann‐Miyashita EF, Pernat N, König HJ. 2021. Citizen science as a bottom‐up approach to address human–wildlife conflicts: from theories and methods to practical implications. Conserv Sci Pract. 3(3):e385. doi: 10.1111/csp2.385.

- Park SE, Marshall NA, Jakku E, Dowd AM, Howden SM, Mendham E, Fleming A. 2012. Informing adaptation responses to climate change through theories of transformation. Glob Environ Change. 22(1):115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.003.

- Rao N, Gazdar H, Chanchani D, Ibrahim M. 2019. Women’s agricultural work and nutrition in South Asia: from pathways to a cross-disciplinary, grounded analytical framework. Food Policy. 82:50–62. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.014.

- Sabatier PA. 1986. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: a critical analysis and suggested synthesis. J Public Policy. 6(1):21–48. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00003846.

- Schipper ELF, Revi A, Preston BL, Carr ER, Eriksen SH, Fernandez-Carril LR, Glavovic BC, Hilmi NJM, Ley D, Mukerji R, et al. 2022. Climate Resilient Development Pathways. In: Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Tignor M, Poloczanska ES, Mintenbeck K, Alegría A, Craig M, Langsdorf S, Löschke S, Möller V, et al, editors. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; pp. 2655–2807 doi:10.1017/9781009325844.027.

- Singh AK, Rajput J, Rai A, Gangwar A, Shahi B, Sharma RB, Kumari N, Singh SK, SriKant, Rai VK, et al. 2020. Socio-economic upliftment of farmers through model irrigated village approach in East Champaran (Bihar), India: a case study. J Appl Nat Sci. 12(4):556–559. doi: 10.31018/jans.v12i4.2332.

- Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. 1990. Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Suh J. 2015. An institutional and policy framework to foster integrated rice–duck farming in Asian developing countries. Int J Agric Sustain. 13(4):294–307. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2014.975480.

- Thornton TF, Comberti C. 2013. Synergies and trade-offs between adaptation, mitigation and development. Clim Change. 13(9/2013):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0884-3.

- Tschakert P, Dietrich KA. 2010. Anticipatory learning for climate change adaptation and resilience. Ecol Soc. 15(2):11. doi: 10.5751/ES-03335-150211.

- Vermeulen SJ, Dinesh D, Howden SM, Cramer L, Thornton PK. 2018. Transformation in practice: a review of empirical cases of transformational adaptation in agriculture under climate change. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2:65. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2018.00065.

- Yadav SS, Lal R. 2018. Vulnerability of women to climate change in arid and semi-arid regions: the case of India and South Asia. J Arid Environ. 149:4–17. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2017.08.001.

- Yin RK. 2018. Case study research and applications: design and methods. Saint Peters, MO, USA: Sage Publications.