Abstract

The relative paucity of research on directing reflects the way in which the practice of directing occurs – behind closed-doors (Trousdell Citation1992). Despite the power afforded to directors, the literature is often comparatively silent on how a director leads a production. Whilst delineating the role of the director can be problematic, the training of directors is a minefield. Unlike actor training where a myriad of theories and methods guide us, the dearth of pedagogical frameworks for teaching directors has resulted in an ad hoc approach at best. Two case studies, conducted by the authors, within the context of conservatoire actor training, formed the basis for research exploring how leadership and creative collaboration could influence directorial practice. This article argues that a significant, and often overlooked aspect of director training is leadership and explores ways in which it can inform director training curriculum. Global #movements over the past five years have forced universities and conservatoires to consider the voices of marginalised and excluded students. By embedding leadership pedagogy into director training there is the potential to create a ‘brave new world’ where actor efficacy and creative collaboration are the vanguard that take directors into a post pandemic world.

Introduction

The revered position that a director holds in the creative process is a role that only emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century. Much has been written about the tangible tasks that a director can undertake as part of their role; casting, visual composition, character and text interpretation feature in much of the literature (e.g. Sidiropoulou Citation2019; DeKoven Citation2019; Innes and Shevtsova Citation2013). Approaches to directing and Rehearsal studies have also been recognised as an integral part of performance scholarship (Ledger Citation2019; Rossmanith Citation2013; McAuley Citation2012; Mermikides & Smart Citation2010; Cole Citation1992). However, the observational lens has rarely been focused on leadership and power, the minutiae of the interactions between directors and those that they direct. This reflects the way in which the practice of directing occurs – behind closed-doors (Trousdell Citation1992). According to Avra Sidiropoulou (Citation2019) ‘Rehearsals are a private affair’ (71), which has meant that ascertaining the complexities of how a director directs is challenging, in many cases coming from accounts by directors themselves. Training directors too becomes problematic, since, unlike actor training where a plethora of theories and methods guide us, the paucity of pedagogical frameworks for teaching directors has resulted in an extemporised approach at best. Considerations then of how we train directors need to not only encompass the approach and tasks but importantly, the way in which a director leads the process, given the power associated with their role.

The authors of this article both teach and direct within the context of conservatoire actor training at Edith Cowan University’s Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA). Practice-led research was conducted to explore how leadership and creative collaboration practices impact actor efficacy and what attributes are important for a director to develop their craft. This article argues that the centrality of traditional hierarchical modes of direction must be challenged, particularly in light of the seismic shift that has occurred in the wake of global movements such as #metoo and #Blacklivesmatter. We offer directorial methodologies that can inform director training, considering the shifting power relations in society.

Directing and leadership

The art of directing, according to American theatre director, Marshall W Mason (Citation2007), lacks the extensive methodologies and sets of principles that Stanislavski offers to the actor. Directors’ methods vary and their practices often reflect personality, communication style, the way they themselves have been directed or what they have witnessed as students or assistant directors. Unfortunately, the lack of methodologies to guide directing practice has meant that as a craft, directing has not received the same attention that was afforded other art forms such as acting. This may be attributed to the manner in which the role of the director evolved.

Richard Wagner and Georg II The Duke of Saxe-Meiningen’s approach as single creative authorities led to the idea of the modern director (Barranger Citation1980). The hegemony of the director has developed to the point where ‘directors hold the economic, artistic and administrative reins firmly in their hands’ (Callow Citation1985, 217). The revered position of the director remained virtually uncontested until the 1970s when postmodernism saw a ‘trend towards pluralism and diversity’ (Auslander Citation2004, 223). Postmodernism and poststructuralism’s disruption of the notion of universal truth paved the way for more experimental and collaborative forms of theatre making to emerge, such as devising, which confronted the privileged position held by the director and the written text.

Postmodernism and poststructuralism challenged linear narratives and embraced multiple perspectives, which led to shifts and disruptions in performance making practices. Arguably though, the hegemonic structures pervading rehearsal room practices and the organisational structures of theatre companies have not fundamentally changed, remaining largely hierarchical. The paradigm in which direction is seen as the work of a single individual, has remained relatively uncontested. The training ground for directors in Universities and Conservatoires sits within this paradigm of directorial prominence. We argue that this needs to change, that leadership needs to challenge white, hegemonic practices and embrace a style of directing that is inclusive, respects difference and opens up the creative space to voices that may have been marginalised.

Case studies

Two case studies, conducted by the authors formed the basis for the research exploring leadership and creative collaboration practices in conservatoire training. In Case Study 1, first-year acting students rehearsed a text-based production, while Case Study 2 sheds light on how the director/researcher devised a production using a creative collaborative approach. These two productions provided data with which to determine how the leadership style of a director can impact the rehearsal process and the agency of actors and in turn what director training needs to include in order to serve emerging directorial students. Ethics approval was granted for the projects in accordance with ECU’s Policy for the Conducting of Ethical Human Research. Permission was obtained from participants to be identified in the research; however, to keep the focus on the findings, we decided to anonymise the students (some of whom would be well known to theatre and film audiences).

Case Study 1 – a production of Away performed by 1st year acting students

Researcher: Gabrielle Metcalf

The leadership style of the director is crucial to how power and influence impact the rehearsal process. Rebecca Daniels (Citation1996) asserts that the director is essentially a leader, ‘While the degree of emphasis differs, most theorists, educators, and practitioners consider leadership to be an integral part of the directing process, and the most often acknowledged quality of a good director is leadership ability’ (11). Case Study 1 examines how a dialogic approach to leadership was instrumental in creating a learning environment where equity and inclusion were central to the directing process.

The production of Away by Australian playwright Michael Gow was conducted over a 6-week period at WAAPA in 2014 with acting students at the end of their first year of training. This group was invited to participate in the study because they had a year of actor training to draw on and they had not yet participated in a fully rehearsed play; their limited experience with professional directors meant their expectations of the director’s role were not as solidly formed as those of students further along in their course. As the director, I took a dialogic approach to the direction of the play, drawing on an autoethnographic methodology. Autoethnography as a research tool, emerged in the late 1980s and is attributed to anthropologist, Carolyn Ellis (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011). It uses the analysis of the lived experience of the researcher as the subject, so that the researcher then becomes both the participant and subject of the study. Therefore, while I was directing I was also a participant in the research, and the dialogic leadership style I used became the subject of the study.

I captured the directing process on video, collected feedback from the students through questionnaires and interviews as well as analysis of the video footage of the rehearsals to determine the efficacy of the leadership approach.

Dialogic leadership

American physicist David Bohm (Citation1996) conceptualises dialogue as a multi-faceted process that is ‘a stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us’ (6), its primary purpose being ‘relaxed, non-judgmental curiosity’ (ix). Through the flow of meaning something new can emerge, which may not have been conceived of previously. Bohm and Peat (Citation2000) maintain that a specific function of dialogue is to dissolve the fixed ways of thinking or blocks we have, which are based on our social and cultural conditioning. The dissolution of fixed ways of thinking that dialogue can make possible allows for originality to emerge. Taylor and Kent (Citation2014) hold that participants in dialogue ‘feel obligated to design their communication interactions with other people to facilitate interaction, self-discovery, and co-creation of reality’ (389). In rehearsal, the co-creation of reality (the world of the play), can be constructed through the communication between the director and members of the cast and crew.

Dialogue’s emphasis on ‘multivocality, open-endedness, human connection, and the co-creation of meaning’ according to communication scholar Laura Black (Citation2008, 94), allows people to explore more fully the complexities of other people’s perspectives. Exploring the complexities of perspectives other than the director’s own invites diversity into the rehearsal/training space. A dialogic approach offers the director an opportunity to interact in ways that are inclusive, non-judgemental and actor-centred.

Dialogic leadership is the term organisational learning scholar William Isaacs (Citation1999a) gives to leading that consistently ‘uncovers, through conversation, the hidden creative potential in any situation’ (2). He considers practical ways in which a dialogic approach towards leadership can be facilitated and the way in which dialogue can enhance creativity. Isaacs (Citation1999a) identifies four behaviours that have the capacity to bring people into dialogue: suspending, listening, voicing and respecting. These four tools of practice informed my direction of Away. The following section explains the tools and provides examples of how they were used in rehearsals.

Suspending

Suspending is a dialogic behaviour where we suspend our view, and simply acknowledge our thoughts and feelings without acting on them. Individuals who are able to suspend do not have all their thoughts already worked out. They are willing to be influenced by the contributions of others and to access their ignorance by asking questions. This is at odds with the long-held belief that a director needs to have a vision, a predetermined journey of the play already worked out. Charlie Peters (Citation2021, 2) contends that the ‘laser focus on a director’s vision is problematic. It sets the director up as a prophet rather than a leader. It focuses on a destination, an imagined end goal, and not on the journey’. While the director needs to have explored the possibilities for the outcome of the production, their vision needs to be held lightly, a departure point that allows freedom for the cast and creatives to be part of the journey and enable change to occur in response to what happens on the rehearsal floor.

Suspension requires adaptability to change; being able to suspend one’s thoughts so as to create space to hear what someone else is saying is a complex task. I often had to remind myself to suspend my thoughts when I began a discussion with the actors. To do this I would try to ask the actors what they thought about the scene or the character’s motivations before I said anything and allowed their responses to influence my thinking.

I am discussing the character of Gwen, with the actor Ellie. The actor is curious about Gwen’s motivations.

Gabrielle: What does she want from him?

There’s a long pause.

Ellie: God.um.I…um. Obedience? Is that allowed?

Gabrielle: Is that what you think?

Pause. Elle thinks about it as another actor shares her thoughts.

Ellie: Just out of interest what do you think the ‘never, never, never’s mean? Are they wilting or decrescending, are they different or is it just the same word she’s just saying three times?

I prepare to launch into my explanation for why I think Gwen repeats the word. Then, Ι stop myself. I suspend my opinion, and instead ask her what she thinks.

Gabrielle: What do you think?

Ellie: I don’t know… I am playing around with it. I just haven’t figured it out yet.

This exchange encourages her to think about why the character says those words and offers her agency in the process. My belief in the validity of her opinion affords her the opportunity to trust her own instincts. Asking her questions not only encourages self-reliance for Ellie but also opens up my own thinking to possibilities. Suspending my beliefs about how a character should be played or a scene interpreted allowed me to hear thoughts and opinions other than my own. As a result, her performance of this scene in the play was embodied and compelling to watch; a testament to the work we did dialogically in rehearsal to discover the character’s motivations.

Listening

Listening requires blending with the person speaking, so rather than imposing meaning on what the actor is saying and looking for alignment with our own point of view, we participate fully in trying to understand how they are perceiving the situation. Isaacs (Citation1999a) asserts that to ‘listen together is to learn to be part of a larger whole – the voice and meaning emerging not only from me, but from all of us’ (4). As a director, the manner in which I listened to the actors was vital to uncovering what the text was saying.

I am rehearsing a monologue with the actor playing Coral and we are trying to understand what the line, ‘He was all golden’ means. Miriam, the actor, becomes completely engaged in the conversation as we search for possibilities and answers.

Gabrielle: Who do you think she is talking to?

The actor pauses, thinks, her eyes searching.

Miriam: I think she is just talking to herself. Or maybe to God or something?

Gabrielle: I don’t know. What is the impulse for her to share this information?

Miriam: I think she um… I think she almost goes into that silence that she’s done before because she is thinking so much about the play…and how it’s affected her. Another pause. I think it’s the turning point for her…it’s inspired something in her.

I am listening so I can understand how the actor is seeing the character. I am asking questions of the actor to help her and myself find what we need to know to progress the scene. This process is dependent on the actor’s willingness to voice what is true for her.

Voicing

Voicing has to do with revealing what is true for the speaker and determining what needs to be expressed in the present moment. Dialogue is about speaking with and includes creating an environment where people are able to share their ideas and thoughts. Dialogue requires asking good questions rather than giving good answers. For the director, asking questions of the actor (rather than telling), opens up the space for diversity of thought and perspective.

Will and I are trying to work out why his character, Harry, opens up and reveals his son’s illness to a relative stranger.

Gabrielle: Do you intend to tell him that your son is sick? What do you think?

The actor sways, looks up and fidgets, as he tries to work out what his character’s intentions are.

Will: Well, actually, yes, I reckon. Maybe not, but when the speech starts, it looks like it’s going that way.

Gabrielle: Yeah.

I pause, I suspend, I notice he hasn’t stopped thinking.

Will: But no, it’s sort of… he pauses still thinking. No, it’s actually no. I don’t think he is planning on telling him until about halfway through the speech.

The actor comes to this realisation because he was able to voice his thoughts and then have them explored. This gives the actor a deeper understanding of what might be going on for his character. He begins to perform the scene.

Will: We have no regrets.

I stop him. It is not clear to me why he said ‘We have no regrets’.

Gabrielle: All right, so why do you respond with ‘We has no regrets’?

Will: I don’t know actually. He pauses.

Will then goes through a whole host of reasons for his character having no regrets. I prompt him with questions to help him clarify his thoughts. His honesty about not knowing allowed us to think together and try and work out what the character is meaning. Together we had the power to discover more about the character than either of us was able to do on our own.

Respecting

Respecting is not a passive act; the origins of the word lie in the Latin word respecere, meaning ‘to look again’ (Isaacs Citation1999b). Respect requires a person to take a second look and accept that other people have something to teach us. To respect is to see people as legitimate others, where their viewpoint is valued in the same way we would like our perspective valued. This encourages free, creative thoughts to emerge.

In order to do this, we need to recognise the habitual reflex that many directors (myself included) have to jump in with our own thoughts, judgment, and a voice that can interrupt flow, direction and creativity. Respect has a dual purpose in the dialogic rehearsal space. One is to see the worth of people, in this case of the actors who I am directing. I see each member of the company as having something valuable to offer, regardless of their experience/knowledge/age/race/gender. Seeing the worth in each person allowed the students to be ‘Open, honest and creative’ (Student A9), which then meant that as a company we were harnessing what each person had to offer.

Luke, who is playing Tom, is working on the scene where he reveals his illness to his friend Meg. At the end of the first beat, I stop the scene.

Gabrielle: So what’s this about?

I assume I know exactly what is going on here for the character of Tom but respecting the value of the actor, I suspend my ideas to listen to his.

Luke: Um…he looks around… thinking. I think it’s about um… internally he’s just thinking everyone knows he, Tom, is sick…

Gabrielle: ‘And that I had to fight and I did’. What does that mean to you?

Luke: Um…I’m thinking back to all the chemos…

Luke’s suggestions cause me to think. I hadn’t even thought about the ‘chemos’. It is in the pauses, the ‘ums’, where we often jump in to give our view or perspective. Respecting the silence, opening the space for a thought to find its way to speech gives rise to true creativity. We run the beat again, the storytelling is much clearer this time, the actor has had the chance to think and to listen to what the character is revealing to him in this moment.

Student response to dialogic leadership

I was successful in creating a space where 90% of participants reported that the sense of collaboration was something they had enjoyed about the rehearsal process. When describing the atmosphere of the rehearsal room, actors mentioned ‘positive and engaging’ (Student A1), ‘strong sense of ensemble’ (Student A4), ‘and ‘It was a fun, safe and creative work environment’ (Student A9).

While the actors indicated that they ‘really enjoyed the freedom given in the process’ (Student A2), they also found that the ‘collaboration was quite daunting.’ I investigated what ‘quite daunting’ meant and learnt that for some actors, the freedom I offered challenged their belief that the director should be telling them what to do. For Student A6, ‘[in] some moments I was not aware whether or not I was going in the right direction’ and ‘I wanted to get told I was wrong.’ For Student A8 ‘it felt a bit like we were winging our way through at times.’ The need to be told they were wrong or going in the right direction is understandable considering their inexperience and perhaps their preconceived ideas about what a director should do.

I had assumed that the freedom would empower the actors, however the permission to offer your opinions, thoughts and fears can also be overwhelming. For example, one actor described to me in a conversation a year after the production that ‘if I had had more confidence in myself and the technique then, I feel like I would have jumped into it even more’ (Student A10). The process of dialogic leadership was for Student A5 ‘Always interesting. I was always learning. Gave me permission to grow and develop.’ The data revealed that the actors in the rehearsal of Away felt confident to voice their opinions and listen to others without judgement, to come together dialogically to create something that was greater than their individual contributions.

Learning and practicing the tools of dialogic leadership; suspending, listening, voicing and respecting could offer the student director fundamental building blocks to learn how to lead a cast where they are able to harness the collective creativity of the actors they are directing. In the dialogic paradigm, directing students have the tools to establish a space that invites participation from all members of the company and to uncover the uniqueness of each person’s contribution.

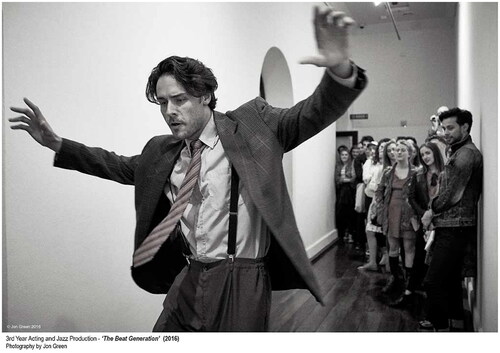

Case Study 2 – the Beat Generation

Researcher: Andrew Lewis

Case Study Two took place at WAAPA in 2016 with students completing their final year of a Bachelor of Arts (Acting) degree. It was the cohort’s concluding production prior to graduating and while they were highly skilled actors by this time in their training they had never created or performed a devised work for a public audience. The Beat Generation was a devised work based on the 1950s anti-authority movement, led by poets, musicians and writers. I used an a/r/tographic methodological approach, drawing on the three aspects of my professional identity – artist, researcher and teacher. Barbara Bickel (Citation2008) provides a deeper understanding of the methodology saying, ‘[a]/r/tography calls for an inner collaborative relationship between my artist self, researcher self and teacher self’, suggesting each of these roles engages the researcher with a ‘critical hermeneutic, self-reflexive practice of art-making and writing’ (126).

I worked with the students to create and direct the work, which provided the opportunity to examine and reflect on the implications of the devising process, leadership and the role of the director. I wanted to discover the efficacy of the devising process for conservatoire training and examine the position assumed by director/educator within this paradigm.

In the current acting degree at WAAPA, most productions draw on extant scripts. While devising and co-creation practices have been introduced into the curriculum, most shows are directed by staff and visiting directors where the director is arguably the dominant creative force, responsible for the vision, casting, rehearsals and putting together of the chosen play. This production gave the students an opportunity to experience a different style of directing that included generating content rather than text interpretation. On my end, I could shift my practice from text based directing to taking on a more facilitatory role in the rehearsal process.

Creating The Beat Generation

The rehearsal process of The Beat Generation was constructed in three-stages:

Generating material

Consolidating the material

Sharing and refining the material

These stages were repeated as we continued to develop the work. In the early stages, I gave the students tasks to research the cultural background of the Beat Generation era. Through a series of devising exercises including viewpoints, stream of consciousness writing and structured improvisation, we generated material that the students could test out. We also developed theatrical sequences using a strategy developed by the Tectonic Theatre CompanyFootnote1 called ‘Moment Work’ (personal communication, May 20, 2016). This occurs when actors are given a prompt such as an object or piece of text and then create performative moments in between the direction of ‘We begin’ and ‘We end’. Moments can include a physical shape, theatrical vignette, movement or vocal composition. From these moments we created a cycle of writing, editing and refining the material, achieving this required adaptability, flexibility and an ability to curate the work effectively.

Using poetry from the era we also created imagined theatrical work, incorporating music, song, movement sequences and enactments. The students were then provided with their own self-directed time to consolidate the work. During this phase we met weekly for ‘show and tell’ sessions, where we provided feedback to each other. When the feedback revealed frustration with differences of opinion, I decided to conduct classes on collaborative processes emphasising creative offers and acceptance. I used many of the exercises and games suggested by Viola Spolin (Citation1999), which helped the students to work through their creative differences. I utilised dialogic leadership which enabled the students to voice their individual views in a forum which resulted in shared decision-making. Explaining that healthy creative abrasion is necessary in devised work helped the students move forward towards creating a performance.

Confidence, ownership and frustration

The outcome of the research revealed how the students experienced the creative collaboration process and how the experience of working in a non-traditional, hierarchical manner on The Beat Generation increased their confidence. Student 1 said it gave her ‘confidence to write and direct my own material’, while for Student 2 it ‘gave me the confidence to continue creating my own material’. Student 3 remarked that their new-found confidence would allow them to ‘develop [their] own work … understanding of use of story arc and space’. Student 4 reflects on the agency he felt, ‘…no director and no external person can really inform you, the way that you can inform yourself. That gives you the confidence to take on other roles and own them as though you’ve written them yourself.’ Students also highlighted the sense of ownership and empowerment they gained from the experience. For Student 5, ‘There is a certain ownership of the performance I’d never experienced before.’

For other students there was a degree of vexation with the process. For example, Student 3 was frustrated in rehearsals because there were ‘no clear leadership positions. There was no cohesion to the vision … There were too many chefs in the kitchen.’ Student 10 identified challenges: ‘It certainly tests your limits with classmates. It’s very hard to create a piece of work with 18 other people, all of whom have different visions’. Student 11 identified that ‘collaboration is both immensely frustrating and satisfying. It’s great to see ideas morph and then grow, but equally, it’s tough to see a lack of progress when decisions can’t be made’. For many students it was frustrating not having a script to work on and I too shared this frustration at times. I wanted to tell them what I thought they needed to do, but not stifle their creativity in the process – it was a balancing act, giving guidance without imposing my vision on the outcome.

For the director

The process of devising encourages ‘diversity and discord’ and deliberately engages a manner of ‘unsettling knowing’ (Perry Citation2011, 68, italics in original). The uncertainty of creative collaboration in devising new and original work meant I had to sit in uncertainty, as multiple visions emerged, retreated, reappeared, changed – somewhat counter to the notion of directorial vision.

Devising encourages actors to make bold offers and take creative risks. It requires of directors to work from a base of listening and dialogue, where they are prepared to allow their directorial vision to evolve and change. Over the course of devising, rehearsing and directing The Beat Generation, I learned how to encourage and enable the actors to make their own choices in relation to producing content. It became apparent that students gained a sense of empowerment and confidence by developing their own material and could apply the skills learned in some way during their career. What could this mean for training directors?

My approach to teaching and directing shifted during this project; I became more reflective about the processes and tasks I set for the student actors. I can see the importance in teaching student directors to become more attuned to hearing all the voices in the room and welcoming even those who may directly challenge their ideas. Mary Overlie (Citation2017) attests to this, seeing the director as one who functions as an ‘observer/participant’ amid the radical elements of the stage, without the need to dominate. The devising process places the actor at the centre of the creative process. At the same time for the student director, learning how to create a strong relationship with the actor allows room for a richer, more inclusive vision to emerge. For myself as a director, this process enhanced my skills of active listening and receptivity, thus providing space for more meaningful dialogue to occur.

One year later

A year after they graduated, I interviewed the students (now professional actors) and asked them for their reflections on The Beat Generation experience. Student 6 stated, ‘since leaving WAAPA, it’s quite obvious how few and far between jobs it is and how hard it is to make a break into the industry’. She had recently collaborated with a group of ex-WAAPA students,

We used a space at the Merrygong theatre for a week to workshop ideas one of us had for a play. It was really great just to get up and have a play together, much like we did with the Beat Generation.

Student 6 acknowledged that The Beat Generation ‘gave me tools that I have used and seen friends use to make work for ourselves and to keep us creative’ since leaving WAAPA. Student 7 noted the value of the devising experience: ‘I auditioned for this really cool feminist play … and they encouraged you to write your own thing. So, I just did my beat poetry thing. They loved it!’. A year after graduating, Student 7 played the role of Lady Macbeth. She notes that

Being able to direct yourself and make bold choices yourself, gave me complete ownership of the character, to the point where I was like, I disagree with this costume choice you’ve made, I don’t think she would wear that. Which was cool.

I learnt from the students’ responses to The Beat Generation that many had gained empowerment and agency from devising their own work. The project certainly had its challenges, with students creating a fully realised work for the first time in their training, but many became aware that devising could help them with future work. They learned to trust their choices and I learned more about directing by listening to them.

Arguably, student actors in a traditional conservatoire model of actor training are rarely involved in the visionary tasks afforded to a director and can be seen in some instances as a vessel for the director to realise a text. Digitisation, dwindling funding for the arts and higher than ever unemployment calls actors to do more than just be great actors. They must be able to generate their own work, make creative offers and get projects up from scratch. The traditional hierarchical style of directing can potentially leave student actors dependent on the director and less resilient as autonomous artists when they graduate from their training.

Director training then could benefit from drawing on leadership pedagogies and the process of creative collaboration. However, it has also become crucial that the way in which we teach students to become directors must also enable them to navigate their way in a world that has experienced upheaval and change in the last five years.

Implications for director training

The past five years has seen a plethora of social movements that have challenged the status quo and forced not only society but performing arts training institutions to confront systemic forms of discrimination embedded in their policies and processes. #metoo gained momentum with many women coming forward with accounts of sexual harassment following the arrest of film producer Harvey Weinstein. Thousands of women supported 2021 Australian of the Year, Grace Tame, with ‘Enough is enough’, a cry for violence against women to stop (Diaz Citation2021). Similarly, the Black Lives Matter campaign took hold with the George Floyd killing and drew attention to violence and systemic racism towards people of colour (Cheung Citation2020). Greta Thunberg drew young people together to speak out against Climate Change. Together with a world-wide pandemic, our global community has experienced unprecedented upheaval in recent years.

The growing response of students to a world and an industry that has begun to acknowledge that it is structured by hegemonic white knowledge, with historical bias around race, skin colour, body image, age and gender, has been prolific. Challenges to the perpetuation of discriminatory practices that pervade our institutions and can marginalise many students has been evident in many countries (Kubota Citation2020). In the United Kingdom, the outcry from students experiencing racism led to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) releasing a statement saying it was ‘committed to supporting all black students’ but acknowledged ‘there is work we must do’ (Bakare Citation2022). RADA are ‘committed to institution-wide change to create an anti-racist and inclusive culture’ (https://www.rada.ac.uk/student-life/zero-tolerance-statement/). Professor Gavin Henderson has apologised for ‘the lived experiences of students of colour’ and his racist comments during his time as Principal of Royal Central (Hill Citation2020). The website of Royal Central states that ‘we have been complicit in systemic and institutional racism. We want to do better.’ (https://www.cssd.ac.uk/anti-racism-at-Central). Guildhall alumni, Paapa Essiedu and Michaela Cole describe the racism they were subjected to while studying there. The school has since made an official apology to the two actors and undertaken programs to address racism in the institution

In the US, students accused Juilliard with systemic injustice and demanded an end to the school’s ‘almost completely Eurocentric faculty, curriculum, and performances…’ (Mac Donald Citation2021). Similarly, an online petition by the Carnegie Mellon student body states: ‘we are saddened by the lack of action our school has taken to combat racial inequality’ (https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/confronting-racial-prejudice-at-carnegie-mellon-university/). In Europe, student-led initiatives have ignited positive change with many art schools in France establishing ‘Listening Centers’, to gather testimonies from students who have experienced racism and discrimination (Lauter Citation2022).

In Australia, acting students at WAAPA decided not to continue with the season of a play about the plight of African American people. They felt that the casting was problematic, and the directing not sensitive to the students of colour in the cast. While disappointed about not being able to finish the season, standing up for their beliefs gave them a sense of agency (personal communication, October 26, 2022). WAAPA have published a statementFootnote2 committing to Anti-Racism as a first step in dismantling the systemic discrimination. At the National Institute of Dramatic Arts (NIDA) in Sydney, more than 100 alumni, students and former staff signed a letter accusing the performing arts school of failing to support black and Indigenous students and students of colour (Ryan Citation2020). NIDA chief executive Liz Hughes sincerely apologised and vowed to quickly drive significant change.

Students’ call for greater diversity, equity and inclusion offers an historic opportunity to greet their demands by examining the role of the director and how we will prepare students to direct and be directed, in a landscape that is vastly different from the one where we learnt our trade. How can we guide student directors to develop an artistic practice that acknowledges the impact of colonisation and racism, that acknowledges the inequities of gender, that acknowledges the systemic oppression that many people face?

A crucial part of training directors is leadership skills and the degree of complexity around leadership training is significant. This is due in part, to long held beliefs around the power that a director must wield and the position they hold in the creative process. This can be a daunting remit for emerging directors. Introducing a more dialogic approach where the rehearsal room becomes a place for difference to be investigated, where people listen to each other and are able to voice their opinion regardless of their role may potentially create an environment where creativity and inclusivity can flourish. The implications for training directors is that by teaching the skills of collaboration and dialogue, the student director may be better equipped to meet the expectations often placed upon them. Training directors to listen to their heart, listen to actors, listen to co-creators, listen to broader culture and listen to an audience will assist them in becoming receptive artists. By embedding dialogic leadership pedagogy and creative collaboration into director training curriculum, there is the potential to respond to the mine field that global upheaval has caused and create a brave new world where actor efficacy and empowerment can be the vanguard taking directors into a post pandemic world.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gabrielle Metcalf

Gabrielle Metcalf (PhD) is a director, intimacy director/co-ordinator and actor. She lectures in acting and directing at The Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA). She has a special research interest in leadership methodologies and processes for directors, which she has applied to her directing and teaching practice. Gabrielle is a leadership facilitator and coaches Executive Leadership Teams across Australia. She recently completed a book, Teaching Drama, commissioned by Beijing Normal University, outlining how drama can be taught in Chinese schools.

Andrew Lewis

Associate Professor Andrew Lewis has recently completed a PhD investigating the need for devising and collective creation practices to be taught within conservatoire actor training. He has extensive experience in directing film, television and theatre and has directed numerous stage plays and short films. Andrew is a directing graduate of the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) and holds two Masters degrees, in Film and TV Directing (AFTRS) and Film and Theatre Studies (UNSW). He is currently a Senior Lecturer in Acting and Directing at WAAPA and Associate Director of the WA Screen Academy.

Notes

1 The Tectonic Theater Project was founded by Moises Kaufman and Jeffrey LaHoste in 1991, predominantly as a vehicle to engage audiences in social-political change. The two artists are most recognised for their verbatim theatre event, The Laramie Project, developed in 2000.

References

- Auslander, P. 2004. “Postmodernism and Performance.” In The Cambridge Companion to Postmodernism, edited by Steven Connor, 97–115. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bickel, B. 2008. ““Who Will Read This Body?” An a/r/Tographic Statement.” In Arts-Based Research in Education: Foundations for Practice, edited by M. Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund, 125–136. New York: Routledge.

- Bakare, L. 2022. “Drama schools accused of hypocrisy over anti-racism statements.” The Guardian Weekly, June 10. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2020/jun/06/drama-schools-accused-of-hypocrisy-over-anti-racism-statements

- Barranger, M. S. 1980. Theatre: A Way of Seeing. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Black, L. W. 2008. “Deliberation, Storytelling and Dialogic Moments.” Communication Theory 18 (1): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00315.x

- Bohm, D. 1996. On Dialogue. Edited by Lee Nichol. London: Routledge.

- Bohm, D., and F. D. Peat. 2000. Science, Order, and Creativity. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge.

- Callow, S. 1985. Being an Actor. London: Penguin Books.

- Cheung, H. 2020. “George Floyd death: why US protests are so powerful this time.” BBC News, June 8. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52969905

- Cole, S. Letzler. 1992. Directors in Rehearsal: A Hidden World. New York: Routledge.

- Daniels, R. 1996. Women Stage Directors Speak. 1st ed. London: McFarland & Company.

- DeKoven, L. 2019. Changing Direction: A Practical Approach to Directing Actors in Film and Theatre. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

- Diaz, J. 2021. “Thousands march in Australia as another #MeToo wave hits the country.” NPR, March 15. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/15/977340049/thousands-march-in-australia-as-another-metoo-wave-hits-the-country

- Ellis, C., T. E. Adams, and A. P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12 (1): 1–19.

- Hill, L. 2020. “Drama School Head Falls on his Sword.” Arts Professional, June 12. https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/drama-school-head-falls-his-sword

- Innes, C., and M. Shevtsova. 2013. The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Directing, Cambridge Introductions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Isaacs, W. N. 1999a. “Dialogic Leadership.” The Systems Thinker 10 (1): 1–5.

- Isaacs, W. N. 1999b. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together. New York: Random House.

- Kubota, R. 2020. “Confronting Epistemological Racism, Decolonizing Scholarly Knowledge: Race and Gender in Applied Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics 41 (5): 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz033

- Lauter, D. 2022. “The #MeToo and BLM Movements transformed French art schools. But some say they have a lot further to go.” Artnet, March 31. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/descrimination-in-art-schools-2091261

- Ledger, A. J. 2019. The Director and Directing: Craft, Process and Aesthetic in Contemporary Theatre. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mac Donald, H. 2021. "The revolution comes to juilliard." City Journal, May 23. https://www.city-journal.org/racial-hysteria-is-consuming-juilliard

- Mason, M. W. 2007. Creating Life on Stage: A Director’s Approach to Working with Actors. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Drama.

- McAuley, G. 2012. Not Magic But Work: An Ethnographic Account of a Rehearsal Process. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Mermikides, A., and J. Smart, eds. 2010. Devising in Process. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Overlie, M. 2017. Standing in Space: The Six Viewpoints Theory & Practice. New York: Fallon Press.

- Perry, M. 2011. “Theatre and Knowing: Considering the Pedagogical Spaces in Devised Theatre.” Youth Theatre 25 (1): 1–19.

- Peters, C. 2021. “Instead of a vision: listening and dialogue as the work of a theatre director.” Howlround, August 23. https://howlround.com/instead-vision-listening-and-dialogue-work-theatre-director

- Rossmanith, K. 2013. “Spending Two Weeks 'Mucking Around’: Discourse, Practice and Experience during Version 1.0's Devising Process.” Australasian Drama Studies (62): 179–193.

- Ryan, H. 2020. "Alumni accuse NIDA of 'systemic and institutionalised racism.’" Sydney Morning Herald, June 17. https://www.smh.com.au/culture/theatre/alumni-accuse-nida-of-systemic-and-institutionalised-racism-20200617-p553jz.html

- Sidiropoulou, A. 2019. Directions for Directing: Theatre and Method. New York: Routledge.

- Spolin, V. 1999. Improvisation for the Theater: A Handbook of Teaching and Directing Techniques. 3rd ed. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Taylor, M., and M. L. Kent. 2014. “Dialogic Engagement: Clarifying Foundational Concepts.” Journal of Public Relations Research 26 (5): 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2014.956106

- Trousdell, R. 1992. “Directing as Analysis of Situation.” Theatre Topics 2 (1): 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2010.0049