ABSTRACT

Once depicted as a flagship case for the soft power—based foreign policy of young democracies, Turkey’s conduct of foreign affairs following its authoritarian backsliding has been increasingly associated with hard power. Using the case of Turkey’s Africa policy under the AKP, this article challenges this reading and its underlying conceptual assumptions. To overcome the spurious democracy—soft power vs. autocracy—hard power dichotomy, it argues for adopting a process-oriented approach to analysing the foreign policies of (autocratising) states by focusing on, firstly, the foreign policy situations in which they mobilize power resources to a particular end; and, secondly, the extent to which they attempt to gain control over societal power resources.

Introduction

Demonstrating an upsurge in foreign interest, Africa has experienced the largest embassy-building boom of any world region in the 2000s,Footnote1 and Turkey topped the list, nearly quadrupling the number of its embassies on the continent from 12 in 2005 to 43 in 2021.Footnote2 Turkey’s presence in Africa displays great variance in terms of substance and purpose, from troop deployment in Mali and Central Africa to the construction of East Africa’s largest mosque in Djibouti to the proliferation of Turkish television series across African television channels. It has been training Somali soldiers, Mauritanian imams, Zambian doctors, and Kenyan journalists, among others. Illuminating Turkey’s new-found popularity in the region, for instance, ‘Istanbul’ is today one of the most common female names in Somalia.Footnote3 ‘We are consolidating our policy of opening up to Africa in a multilayered and multidimensional manner’, Turkish president Tayyip Erdoğan remarked of this comprehensive pivot to Africa.Footnote4

Once lauded for its humanitarian aid initiatives, Ankara’s Africa policy has increasingly been associated with the country’s expanding military footprint as of late. In general, pundits and scholars who have examined foreign policy initiatives during the two-decade rule of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP) tend to equate the relatively democratic first decade with soft power and the more autocratic second decade with hard power. Initially, the AKP’s foreign policy activism, wriggling out of the traditional securitized framework, was largely presented as ‘Turkey’s rising soft power’,Footnote5 or ‘the rise of the trading state’.Footnote6 Concepts such as ‘humanitarian diplomacy’Footnote7 and ‘public diplomacy’Footnote8 were regularly invoked not just to make sense of this political and economic opening in pursuit of regional and global integration but also to provide ground for its normative legitimation. However, as Turkey engaged in several theatres of war in the 2010s, evaluations of Turkey’s public diplomacy have been heavily supplanted by analyses of Turkey’s ‘coercive diplomacy’,Footnote9 ‘gunboat diplomacy’,Footnote10 or ‘drone diplomacy’.Footnote11 The public debate has centred on ‘how Turkey militarized its foreign policy’,Footnote12 thereby problematizing the country’s ‘rising hard power’.Footnote13 In this binary understanding, Turkish foreign policy previously shifted ‘from “hard power” to “soft power” and [recently] back again’ to hard power.Footnote14 This resonates with the observation of Joseph S. Nye, who coined the term soft power, that Turkey’s soft power has been in decline, with less democracy since 2013.Footnote15

This article critiques the democracy—soft power vs. autocracy—hard power dichotomy and utilizes Turkey’s sub-Saharan AfricanFootnote16 policy as a case study to demonstrate the inadequacy of these conceptual categories. It does so by zooming in on the domestic level of analysis and explores how key political transformations at the unit level have impacted the evolution of Turkey’s foreign policy. From a broader perspective, it thus emphasizes the importance of conducting a thorough analysis of the foreign policy choices of the new political regimes that have emerged during the ongoing third wave of de-democratization. While students of comparative politics develop new concepts and approaches for studying these defective forms such as competitive authoritarianism or liberal autocracy,Footnote17 foreign policy analysis, too, demands new research in this field. This article rests on the established practice of invoking domestic politics to explain foreign policy choices.Footnote18 Instead of classifying countries by regime type, such as democratic and authoritarian, and then judging their foreign policy behaviour in snapshots, it focuses on democratization and autocratisation and how these processes are reflected in foreign policy. The article’s contribution to the academic literature is hence twofold: Firstly, it shows how the inclusion of a domestic perspective can help traverse the oft-criticized soft-hard power divide. Secondly, it advances our understanding of how internal processes of political transformation inside a given state sway the evolution of its foreign policy, thus providing new and critical insights into the field of foreign policy change.Footnote19

The article begins with a critical reflection on the soft—hard power divide. Following a brief introduction to the case study, it first explains how Turkey’s Africa policy has traversed its soft and hard powers, rendering any discussion based on these conceptual categories deficient. The article then proposes to seek the trend of change not necessarily from soft to hard power, but rather in the increasing resource control by the state. The final section connects the empirical case to the larger debate on power and foreign policy.

The soft–hard power divide amid autocratisation

Few concepts exist in International Relations that are as popular, while simultaneously being subject to fundamental criticism, as that of soft power. To name but a few examples of this criticism, the concept’s lack of theoretical robustness,Footnote20 its static conceptualization,Footnote21 and its failure to clearly distinguish between power resources and foreign policy instruments have all been scrutinized.Footnote22 The present article argues for adopting a process-oriented approach to analysing how power resources are deployed by autocratising states. In doing so, it also seeks to attenuate two major conceptual problems that have long been discussed with respect to soft power: the ambiguity surrounding the alleged soft—hard power divide and the confusion about the nature and, indeed, permissibility of authoritarian soft power.

In his introduction of the concept as well as in later studies, Joseph S. Nye has contrasted soft or ‘co-optive power’ – i.e., ‘the ability to change what others want’ – with hard or ‘command power’ – i.e., ‘the ability to change what others do’.Footnote23 The inherent dichotomous understanding of intangible soft power on the one hand and tangible hard power on the other has faced substantial criticism.Footnote24 One major reservation is that what can be regarded as soft or hard power is not well defined but critically hinges on the context of resource mobilization.Footnote25 That is, the use of hard power resources such as the military can attract othersFootnote26 as much as the use of soft power resources can provoke the opposite effect.Footnote27 What matters in this respect is not only ‘intelligibility’ – i.e., the question of whether, and how, the (mobilized) resource reverberates in the value system of the receiverFootnote28 – but also, crucially, the particular situation in which power resources are mobilized and to what end.Footnote29 Giving international aid, for instance, can be a source of co-optive power, yet one that can turn coercive when employed to make others comply with your demands. The article takes this contextual argument to be key to traversing the soft—hard power divide.

Another important source of criticism concerns the concept’s application, and applicability, to authoritarian regimes. Some critics stress that soft power – as per its initial conceptualization and further developmentFootnote30 – is too closely knit to, in fact preconditioned on, the allure of liberal values and institutions and thus fails to recognize non-liberal sources of attraction and authoritarian types of soft power.Footnote31 Yet almost the same reason, albeit levelled from the opposite direction, is used to refute the notion of authoritarian soft power, which, as another set of critics argues, would fail some of the core criteria of soft power. The notion of ‘sharp power’, which was recently introduced to counter the ‘overreliance on the soft-power paradigm [that] has bred analytical complacency regarding the growth of authoritarian influence’,Footnote32 is a prime example for the latter line of argumentation. Authoritarian states, so the argument goes, ‘are ill equipped to “do” soft power well [because of their] state-centric governance model’ that encroaches on civil society, which is a significant source of soft power, yet only if it remains unfettered by the state.Footnote33

The concept of sharp power takes the exclusive attraction of liberalism for granted and does not engage with the question of intelligibility. For this and two further reasons, it is unfit to mend soft power’s conceptual problem regarding authoritarianism. Firstly, sharp power was designed to capture authoritarian efforts to ‘pierce, penetrate, or perforate the information environments in the targeted countries’.Footnote34 As such, it introduces a new concept that should be kept analytically distinct from that of soft power.Footnote35 Secondly and owing to its empirical focus on China and Russia – the modern-day prototypes of full-fledged autocracies – one cannot derive robust conceptual claims for the bulk of today’s authoritarian regimes positioned in the grey zone between autocratising democracies or democratizing autocracies.Footnote36 Despite this, the sharp power concept raises two points that are beneficial in the investigation of our research problem. The first is its call to zoom in on the intentions behind sharp power strategies, which, translated to our context, reiterates the need to focus on the situation in which attempts to influence are made and why (i.e., the contextual argument). The second point of note is its problematization of resource control.Footnote37

To understand what one might refer to as the resource control argument, one must recall that, according to Nye, soft power rests on three main resources: culture, political values, and foreign policy.Footnote38 Nye therefore asserts that ‘civil society is the origin of much soft power’, which is another way of saying that the bulk of a country’s soft power resources are not under the direct control of the (liberal) state, nor are they necessarily responsive to its purpose.Footnote39 Except by its public diplomacy then, which is a typical foreign policy instrument, the liberal state cannot mobilize most of its soft power resources in a coherent manner.Footnote40 By contrast, the situation differs profoundly in full-fledged autocracies such as China, in which the state ‘controls almost all vital resources [and has] control over the use of soft power’.Footnote41 The extent to which a state controls the power resources resting with society is hence a crucial indicator when classifying liberal and authoritarian foreign policies – and one also fit to describe processes of autocratisation, which are characterized by states’ incremental attempts to contain societal freedoms. Likewise, the resource control argument nicely combines with the contextual one: when states’ control over societal power resources increases, so too does their capacity to purposefully employ these in a coercive way whenever they deem fit.

To sum up, the following two assumptions will guide the following empirical analysis. Firstly, the dichotomous understanding of soft and hard power is conceptually spurious and arguably obsolete. Whether a mobilized resource is supposed to attract rather than coerce its target can be answered empirically only by examining the very situation, or series of situations, in which resources are employed and why. This contextual argument militates in favour of a process-oriented approach to assessing the foreign policy of a given state towards another state or group of states. It applies to both liberal and authoritarian regimes and prompts us to also investigate the domestic setting in which foreign policy decisions are taken, especially during autocratisation. Secondly, states can employ only those resources they control. Since many resources commonly associated with soft power are societal rather than state-owned, it is crucial to investigate the degree of a given state’s penetration of society to assess its capacity to use societal resources when making influence attempts, notably during autocratisation. This resource control argument again calls for a process-oriented approach in analysing the international relations of a given state – or, for that matter, Turkey’s relations with African states under the aegis of the AKP.

Turkey’s presence in sub-Saharan Africa

Both the proponents and opponents of the AKP tend to overstate Turkey’s penetration of the African continent. Its advocates extol this unrivalled ‘success story’ as proof of ‘new Turkey’s’ vim and vigour, whereas its international critics point to how the country has been racing head-long into Africa and unsettling the continent for its own ends.Footnote42 While Turkey significantly trails global heavyweights such as the United States and China, the pace is still impressive, particularly for a middle power.Footnote43 Beyond doubt, Turkey looks back on a long history of engagement with Africa. For instance, its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire, appointed a consul to Cape Town in 1861, and the Turkish Republic opened its first sub-Saharan embassy in Addis Ababa in 1926, shortly after its foundation in 1923. It also was quick to recognize the newly independent countries during the decolonization of Africa in the mid-1950s and 1960s. Nevertheless, Africa largely remained anathema to politicians until the 1990s, when Turkey sought to redefine its role in the post—Cold War era and diversify political and economic allies. The shift in Turkey’s predisposition was evident in several initiatives, including former prime minister Necmettin Erbakan’s Islamist project in 1996 to unite Muslim countries from Bangladesh to Nigeria under the D-8 Organisation and the vision of then foreign minister İsmail Cem of Turkey as a multi-civilizational country and the ensuing Africa Action Plan in 1998.Footnote44 In light of Turkey’s aspiration to play a stronger role in the global order, the AKP’s Africa policy represents not a break with, but rather a continuation and indeed realization of, the strategies outlined by preceding governments. AKP governments have envisioned a resurgent Turkey with a multi-faceted foreign policy and have recast the country as an ‘Afro-Eurasian’ state.Footnote45 This entails a much larger projection than the traditional right-wing conceptions of Turkey’s sphere of influence extending from the Adriatic Sea to the Great Wall of China. Since declaring 2005 the ‘Year of Africa’, Turkey—Africa relations have accelerated at a rate unprecedented in the Ottoman and republican history, elevating the once-negligible continent to a central pillar of Turkish foreign policy.

Especially after the AKP’s dream to establish a Turkey-led Sunni regional order in the wake of the Arab Uprisings faded away, Africa became a more essential component in its grand strategy. For various Turkish governments, Africa has represented a lucrative market to be tapped, an opportunity to alleviate Turkey’s isolation and break away from traditional allies, a source of strength during times of political and economic distress, and ultimately a blank canvas on which to write its own success story as an emerging global player. The Turkish government has enlisted the assistance of a range of governmental entities to establish a long-term presence on the continent. Apart from the 31 embassies opened between 2009 and 2021, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), which conducts development projects through 22 coordination offices, and Turkish Airlines, which flies to 61 destinations in 40 African countries, have contributed significantly to the infrastructure development as a trailblazer for other state and non-state actors. By 2021, seven Yunus Emre Institutes and 170 Maarif Schools (operating in 25 countries) have provided education to tens of thousands of sub-Saharan African children.Footnote46 Furthermore, Turkish troops have been engaged in UN operations in Mali and Central Africa since 2016, and Turkey created a joint task force command with Somalia in 2017 – Ankara’s largest overseas military training centre. Although none is a prominent commercial partner of the other, the trade volume between Turkey and sub-Saharan Africa has increased eightfold, from $1.35 billion in 2003 to $10.7 billion in 2021.Footnote47 Turkey’s advances were not unrequited but met with open arms: Turkey was designated a ‘strategic partner’ by the African Union in 2008 and elected to the UN Security Council as a non-permanent member the same year, thanks to the support of all but two African countries.Footnote48

Coercive attraction: blurring boundaries between hard and soft powers

AKP governments have deliberately used the notion of soft power to define and legitimize Turkish foreign policy in Africa and beyond.Footnote49 Yet Turkey’s actual Africa policies not only defy such an exclusive self-characterization but also challenge crucial assumptions of the soft power concept, including the attractiveness often assumed to be particular to liberal democracies. To begin with, the Turkish narrative employed towards Africa was not primarily based on its (controversial) status as a model of Muslim democracy as it was in the Middle East during the Arab Uprisings, but on its opposition to Western powers. Turkey has pursued Third Worldism alla turca in its Africa policy, portraying itself as a benevolent actor in stark contrast to Western imperialists in the continent’s past (and present). The Turkish discourse is framed as ‘sterile, apolitical’, and fully humanitarian, emanating from ‘a state without colonial ambition and inspired by goodwill’.Footnote50 Projecting his anti-Westernist rhetoric at home on Africa policy, Erdoğan has repeatedly stressed Turkish exceptionalism: ‘Our ancestors have never had a colonial post in Africa in their millennial history […]. Our ancestors, who established states that spread across three continents have never acted with imperialist purposes in other regions’.Footnote51 This ‘Turkey is not like others’ discourse has been materialized through extensive humanitarian and developmental aid projects in Africa, fostering South—South relations. The AKP promoted ‘humanitarian diplomacy’ as a cornerstone of its foreign policy and, as an EU candidate, allocated almost as much humanitarian aid to Africa in 2018 as the 28 EU member states did combined.Footnote52

Alongside Turkey’s reservations about actively promoting itself as a role model of a Muslim democracy, Turkey also purposefully abstains from applying key standards of liberal donors’ development policies. Turkey does not attach any formal conditionality to its aid or trade, presenting it as a demonstration of ‘its respect for the sovereignty of the recipient countries’.Footnote53 In practice, for the African countries with a long record of human rights violations, authoritarian donors such as China and Turkey seem convenient alternatives to Western donors, undermining the latter’s preconditions such as combatting corruption and upholding the rule of law.Footnote54 According to the 2020 Aid Transparency Index, Turkey’s TIKA is the second-least transparent organization, ranked above only China’s Ministry of Commerce.Footnote55 In trade, for instance, the Ethiopian government’s lethal use of Turkish drones in its controversial suppression of Tigray rebels led to a high number of civilian casualties and raised serious concerns about the lack of humanitarian or legal constraints on Turkey’s drone sales.Footnote56 Whether Turkey’s development and trade policies have led to an increase of its attractiveness in the eyes of African states cannot be stated conclusively – as is the case with the assumed attractiveness of liberal foreign policies. But, as will be shown further below, these policies provided the basis for Turkey’s gaining influence with African states in different contexts.

It has been argued above that the context in which power resources are mobilized, and why, ultimately defines whether such resources can be deemed attractive or coercive. Therefore, even the military, i.e., the hard power resource par excellence, or, by way of extension, the military industry can be a source of attraction. Turkey is NATO’s second-largest military power behind the United States, and its involvement in a variety of military conflicts ranging from Syria to Libya to Nagorno-Karabakh in addition to the use of its combat drones has garnered international attention. While Turkey’s drone programme has a significant impact on the global landscape, the country has become one of the world’s emerging arms suppliers.Footnote57 Among the numerous sorts of weaponry and military vehicles produced by Turkey, the low cost and high efficiency of the Turkish drones have increased the country’s popularity in the global defence market.Footnote58 Turkey’s arms sales have experienced their biggest increase respective to African countries, including Algeria, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, Rwanda, and Uganda. The growing interest in Turkish weapons not limited to Africa resulted in a record of $2.8 billion in defence exports in 2021 – a sevenfold increase over the previous year.Footnote59 Whether or not the Turkish arms industry has been a source of attraction is difficult to prove. But despite claims about Turkey’s isolation in the global politics, these weapons sales prompted many African countries to participate at the 2021 Turkey—Africa Partnership Summit in Istanbul and cut new arms deals.

On a deeper level, the largely uncritical use of the term of ‘soft power’ often conceals the power dynamics that underpin foreign policy decisions.Footnote60 Again, the contextual argument helps reveal the power dynamics at play by zooming in on the situations in which power resources are used and with what intention. Considering the regional rivalry between the Turkish—Qatari and Saudi—Emirati alliances,Footnote61 for instance, both parties have instrumentalised donor assistance to gain political and strategic leverage over the African continent. Likewise, recipient African countries have leveraged their own position to capture and utilize that aid.Footnote62 Soft and hard power are inextricably linked. While (intangible) soft power may necessitate the (tangible) infrastructure of hard power, the reverse holds too. When, for instance, Somalia was suffering from a civil war and famine, Erdoğan visited the capital Mogadishu in 2011 and promised a comprehensive aid package, establishing Turkey as Somalia’s largest donor. Yet, what began as Turkey’s humanitarian intervention was followed by the re-opening of the Turkish embassy the same year, then the opening of Turkey’s largest embassy headquarters ever, in Mogadishu in 2016, and finally the inauguration of Turkey’s largest overseas military facility, TURKSOM, in 2017 – a significant step towards regional supremacy on the Horn of Africa. The trajectory from providing humanitarian assistance to establishing a military foothold runs counter to the innocence of soft power and exemplifies the strong ties between the two categories in the case of Turkey.

The Turkish case not only illustrates how soft and hard power can be traversed in different contexts, but it also showcases the extent to which asymmetrical relationships facilitate the use of one and the same power resource to either attract or coerce others. Small countries face the risk of being bullied in relationships with less dependent partners as they lack bargaining power and are subject to later revisions of the terms. In the African context, because Turkey can mostly walk away from political and economic relationships at little cost, disparities, if not dependence, may develop, compelling the weaker state to grant political or economic concessions to the other. Turkey’s relationship with Somalia, likened to that between Turkey and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, showcases how far this proto-dependency can evolve.Footnote63 Asymmetric relationships alone do not confer political influence, as dependent states eventually develop skills to avoid exploitation or accommodation.Footnote64 Nonetheless, such asymmetries are ‘most likely to provide sources of influence for actors in their dealings with one another’.Footnote65

The AKP government has used these asymmetries to dictate its terms, while turning the instruments of attraction to those of coercion. In 2014, it launched a transnational campaign against its erstwhile ally, the Gülen Movement (GM),Footnote66 and warned African countries about such ‘vicious structures’ operating ‘under the mask of education or humanitarian assistance’.Footnote67 After the failed coup attempt of 15 July 2016, which Erdoğan blamed on the GM and its extensions within the Turkish military, the AKP government frequently declared its intention to root out the GM in Africa and used several means to that end.Footnote68 Due to their clientelistic relationship with Turkey, some African countries agreed briskly to Turkey’s demand, whereas others saw it as an intrusion into their internal affairs.Footnote69 Reaping the benefits of its military technology investment and finding new markets, Turkey has managed to leverage African demand for Turkish-made military hardware as a ‘bargaining chip’ in economic and political negotiations. For example, in exchange for selling combat drones to Ethiopia in 2021, Turkey was allowed to close ten Gülen schools in that country and transfer them to the Maarif Foundation.Footnote70 As another case, the Nigerian government was long reluctant to accept the Turkish government’s repeated requests to close 17 Gülen schools in the country. When the Turkish embassy’s espionage and profiling activities against Gülen schools were exposed, President Buhari deemed the Turkish spying as a threat to Nigeria’s sovereignty.Footnote71 However, the purchase of Turkish drones at a time of an impending US embargo ‘motivated’ the Nigerian government to restrict the GM’s business and financial operations in the country. ‘The Nigerian government clearly will not allow any interest, individual or group, to undermine the very warm and cordial relationship between the two nations’, the president’s spokesperson Shehu stated.Footnote72

Re-statisation and increasing resource control in foreign policy

While acknowledging the impact of domestic politics on foreign policy, this paper does not see that impact in Turkey’s recently intensified use of power resources typically associated with hard power vis-à-vis African states. Despite a noticeable increase in its military footprint, Turkey’s ‘soft power engagements’ in education, culture, and diplomacy remain vibrant. Turkey’s domestic change, however, is most visible in the state’s increasing resource control in foreign policy making and implementation. As outlined above, it is the relative control over societal power resources that distinguishes autocratising states from democratizing ones, and it is the incremental control over societal power resources that enhances the capability of autocratising states to purposefully use resources typically associated with soft power. This trend of appropriating societal power resources is also displayed in Turkey’s Africa policy.Footnote73

The AKP’s Africa policy began as a text-book example of the collaboration of state and non-state actors. In fact, the GM established a foothold in many African countries before the Turkish state did, prompting scholars to frame the Turkish pivot to Africa as ‘a civil society-led, state-followed initiative’ ().Footnote74 Parallel to Turkey’s vision of opening up to Africa in the 1990s, the first Gülen schools were opened in Algeria (1994), Senegal (1997), Nigeria, Kenya, and Tanzania (1998), all of which already had diplomatic representation from Turkey. But the movement’s educational network soon expanded exponentially, reaching 98 schools across the continent by 2015.Footnote75 While the movement’s organization Kimse Yok Mu initiated several humanitarian assistance programmes, its umbrella business association the Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists (TUSKON) facilitated trade with African partners through annual ‘trade bridge’ meetings.Footnote76 Because of the marriage of convenience between the AKP and GM at home and the government’s ensuing support for the latter’s activities in Africa, the movement was perceived by the African authorities as part of the ruling bloc.Footnote77 In the absence of diplomatic missions, the Gülen schools indeed acted as Turkey’s de facto embassies, deepening the country’s ties with the African continent.

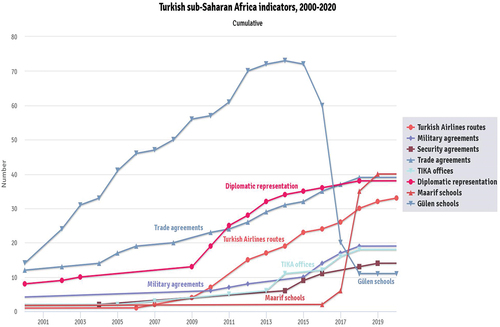

Figure 1. Indicators of Turkish foreign policy towards Sub-Saharan Africa (2000–2020).Footnote80

In line with a new understanding of ‘total performance’, i.e., the mobilization of state and non-state actors towards shared foreign policy goals, the AKP governments not only thrived on these prior networks as a precursor to its move to Africa, but also enabled them to flourish with state recognition and assistance. Turkey’s Africa policy evolved from single-track diplomacy centred on the state to a multi-track diplomacy, encompassing both public and private stakeholders.Footnote78 This multidimensional and multistakeholder framework largely set Turkey apart from other rising powers.Footnote79 Compared to the limited role of non-state actors in pre-AKP foreign policy, this de-statisation occurred concurrently with the AKP’s relatively inclusive democratic discourse at home. TIKA occupied a central position in the country’s Africa policy. It began operations in Africa from an office in Ethiopia in 2005, acting as a facilitator and coordinator of public and private actors operating south of the Sahara.

Turkey’s humanitarian intervention in the 2011 Somali famine was the pinnacle of the collaboration between the Turkish state and (Turkish) non-state actors in the African theatre. Simultaneously, it was a watershed moment in which the Turkish state put its capacity to the test and thereafter incrementally took control of the resources mobilized for its Africa policy. As shows, although declared in 2005, Turkey’s actual opening to Africa took place between 2009 and 2015 with the mushrooming of Turkish embassies and new destinations of Turkish Airlines in Africa. The shift away from the private sector-driven nature of this foreign policy also coincides with the transformation of the AKP—Gülen rift from a hidden confrontation into an all-out war from late 2013 onwards.Footnote81 An early step towards increasing state control was the nationalization of the Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEIK), which lost its autonomous status by a 2014 decree and was restructured as a sub-unit under the Ministry of Economy. Thus, the state assumed direct control of the economic realm of Turkey’s foreign policy. In place of the outlawed TUSKON, DEIK has periodically organized Turkey—Africa Economy and Business Forums, the first having taken place in November 2016 – all with state funds.Footnote82 As such, the Turkish state has either devised new instruments or reconfigured existing ones to increase resource control. In the security sector, the state-owned Presidency of Defence Industries was reorganized to serve as the primary actor in controlling and promoting Turkey’s defence exports.Footnote83 In education, the Maarif Foundation was founded in June 2016 for the explicit purpose of taking over the Gülen schools and establishing a transnational education network under Turkish state control. As Turkey’s overseas education arm, it possesses exclusive authority as stated in Article 2(f) of the founding law (No. 6721): ‘Abroad, in cities in which the Turkish Maarif Foundation opened formal and non-formal educational institutes, other public institutions and organizations cannot form other units with the same purpose’.Footnote84 indicates how rapidly the Maarif schools have multiplied through either the confiscation of the Gülen schools or the opening of its own. Under the International Imam-Hatip (Imam and Preacher) High School Project, Turkey’s Diyanet Foundation has also been providing scholarships to tens of thousands of African students.Footnote85

Recognising the GM’s transnational operations as a national security threat, the Turkish state has increasingly taken on functions previously outsourced to the private actors. The AKP continues to collaborate with loyal non-governmental organizations such as Deniz Feneri, the Cansuyu Charity and Solidarity Foundation, and the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH).Footnote86 Embedded Sufi communities such as the Aziz Mahmud Hüdayi Foundation and Erenköy Cemaati are also allowed to operate as the Diyanet’s ‘silent partners’ in Africa, promoting the Turkish state’s imam-hatip model of religious education.Footnote87 In the economy, the pro-government Independent Industrialists and Businessmen Association (MUSIAD) was strengthened in Africa with offices established in South Africa and Sudan in 2016.Footnote88 Overall, while a limited number of private actors showing allegiance to the government are permitted to operate, this does not negate the emerging monopoly of state institutions such as Diyanet or the Presidency of Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB) in their respective fields of Africa policy.

This re-statisation is still different from the pre-AKP foreign policy tradition, in which the military enjoyed a salient role in defining the national security framework and prioritizing it over other foreign policy objectives. It is not the military but the political leadership that now dominates foreign policy formulation and implementation. Such an overconcentration and personalization of power, with enhanced resource control, is typical of the Middle East.Footnote89 This notwithstanding, the Turkish case reflects the patterns of populist autocratisation, by which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been gradually sidelined and nearly replaced by the Presidential Palace in terms of its functions.Footnote90 By the end of 2021, President Erdoğan had visited 30 African countries – an unprecedented feat for a non-African leader. This increasing travel diplomacy is the new custom for developing and implementing Turkey’s Africa policy. The institutional reflection of this personalization of power is noteworthy. For instance, TIKA, which, under the prime ministry, used to coordinate humanitarian and development aid to foreign countries in cooperation with state and non-state actors, was downgraded and attached to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism by presidential decree dated 15 July 2018.Footnote91 This was a clear indication of TIKA’s demotion. The official restructuring suggests a new setting in which the state partly relinquishes the role of coordinator and takes the reins of resource control in foreign policy.

Conclusion

Turkey’s Africa policy under the AKP, and its foreign policy in general, has recently witnessed a categorical reclassification by scholars, think tank personnel, and journalists alike. Once depicted as a flagship case for a soft power-based foreign policy of a nascent democracy, Turkey’s Africa policy in the aftermath of its authoritarian backsliding has come to be seen as proof that authoritarian regimes cannot do soft power but prefer to play it hard. This article set out to challenge this reading as well as its underlying conceptual assumptions. Empirically, it has shown both that while Turkey’s Africa policy under early AKP governments has made use of foreign policy resources associated with hard power, if modest in scope, its latest Africa policy has not completely dispensed with those ingredients commonly associated with soft power either. While there has been a noticeable change in character, it is questionable whether this shift can be commensurably captured with the binary categories provided by the soft-power approach. On a conceptual level, the article has thus suggested, firstly, zooming in on the foreign policy situations in which power resources are mobilized to a particular end and, secondly, investigating the extent to which the state attempts to gain control over power resources that rest with society. Both the contextual and the resource control argument challenge the customary, clear-cut categorizations of soft vs. hard power, and they encourage researchers to focus on foreign policy processes, including those that occur when states transition from democracy to authoritarianism, and vice versa.

From this shifted perspective, the evolution of Turkey’s Africa policy since roughly mid-2010s can be considered as autocratising in that the Turkish state has increasingly appropriated societal power resources, which, together with traditional sources of state power, were more often used to coerce African governments to fulfil its demands in several foreign policy situations. At times, these demands were prompted by Turkey’s conflicts – for example, with regional rivals such as Saudi Arabia or the UAE. At other times, Turkish demands towards African governments were rooted in the AKP’s conflicts with domestic rivals and, as such, a more obvious token of Turkey’s autocratisation. In a nutshell, Turkey’s Africa policy has indeed become more coercive or, put differently, the flow of Turkish resources to African countries has been increasingly impinged upon by the government’s domestic considerations. However, while it is still intriguingly difficult to gauge a country’s soft power (i.e., as an outcome), this transactional momentum may not bode well for Turkey’s attractiveness in Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jens Heibach

Jens Heibach is a postdoctoral research fellow at the GIGA Institute for Middle East Studies, Hamburg. His research focuses on conflict dynamics in the Persian Gulf and on the Arabian Peninsula in particular. Heibach’s articles have appeared in journals such as Democratization, International Politics, and Middle Eastern Studies. His research has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and EC Horizon 2020.

Hakkı Taş

Hakkı Taş is a postdoctoral research fellow at the GIGA Institute for Middle East Studies, Hamburg. His research interests include populism, political Islam, and identity politics, with a special focus on Turkey and Egypt. His articles have appeared in journals including Comparative Studies in Society and History, PS: Political Science and Politics, and The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. Taş’s research has been funded by several institutions such as the Swedish Institute, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, and Gerda Henkel Foundation.

Notes

[1] G. Mills and M. Nwokolo, Foresight Africa 2022, Brookings, Washington DC, 2022, pp. 104–122.

[2] G. Kavak and T. Aktas, ‘Turkey’s influence in Africa on the rise’, AA, 21 October 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkeys-influence-in-africa-on-the-rise/2399194 (accessed 3 November 2021).

[3] Mohammed Dhaysene, ‘“Istanbul” a common female name in Somalia as Turkish influence gains momentum’, AA, 24 December 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/istanbul-a-common-female-name-in-somalia-as-turkish-influence-gains-momentum/2456289 (accessed 3 March 2022).

[4] R.T. Erdoğan, ‘Presidency of The Republic of Turkey: “We Consolidate Our Policy of Opening up to Africa in a Multilayered and Multidimensional Manner”’, 26 January 2020, https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/115392/-we-consolidate-our-policy-of-opening-up-to-africa-in-a-multilayered-and-multidimensional-manner- (accessed 1 November 2021).

[5] İ. Dağı (ed.), ‘Special Issue: Turkey’s Rising Soft Power’, Insight Turkey, 10(2), 2008, pp. 3–116.

[6] K. Kirişçi, ‘The Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy: The Rise of the Trading State’, New Perspectives on Turkey, 40, 2009, pp. 29–56.

[7] A. Davutoğlu, ‘Turkey’s humanitarian diplomacy: objectives, challenges and prospects’, Nationalities Papers, 41(6), 2013, pp. 865–870; P. Akpınar, ‘Turkey’s Peacebuilding in Somalia: The Limits of Humanitarian Diplomacy’, Turkish Studies, 14(4), 2013, pp. 735–757.

[8] İ. Kalın, ‘Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Turkey’, Perceptions 16(3), 2011, pp.5–23; S. Çevik and P. Seib (eds.), Turkey’s Public Diplomacy, Palgrave, London, 2015.

[9] Ş. Kardaş, Understanding Turkey’s coercive diplomacy, German Marshall Fund of the United States, Washington DC, 2020.

[10] İ. Uzgel, ‘The rise of Turkey’s gunboat diplomacy’, Duvar, 6 January 2020, https://www.duvarenglish.com/columns/2020/01/06/the-rise-of-turkeys-gunboat-diplomacy (accessed 3 December 2021).

[11] F. Borsari, ‘Turkey’s drone diplomacy: Lessons for Europe’, ECFR, 31 January 2022, https://ecfr.eu/article/turkeys-drone-diplomacy-lessons-for-europe/ (accessed 3 April 2022).

[12] A.J. Yackley, ‘How Turkey militarized its foreign policy’, Politico, 15 October 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/how-turkey-militarized-foreign-policy-azerbaijan-diplomacy/ (accessed 2 April 2022).

[13] A. Bakır, ‘Mapping the Rise of Turkey’s Hard Power’, Newlines Institute, 24 August 2021, https://newlinesinstitute.org/turkey/mapping-the-rise-of-turkeys-hard-power/ (accessed 11 December 2021).

[14] G. Tol and B. Baskan, ‘From “Hard Power” to “Soft Power” and Back Again: Turkish Foreign Policy in the Middle East’, The Middle East Institute, 29 November 2018, https://www.mei.edu/publications/hard-power-soft-power-and-back-again-turkish-foreign-policy-middle-east (accessed 2 June 2021).

[15] M. Zeynalov, ‘Joseph Nye says Turkey has less soft power, less democracy’, Today’s Zaman, 5 April 2015.

[16] For the sake of readability, the article henceforth uses ‘Africa’ instead of ‘sub-Saharan Africa’ except in those cases where this omission could lead to textual misunderstandings.

[17] D. Collier and S. Levitsky, ‘Democracy with Adjectives—Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research’, World Politics 49(3), 1997, pp. 430–451; S. Levitsky and Lucan A. Way, ‘Elections without Democracy—The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism’, Journal of Democracy, 13(2), 2002, pp. 51–65; F. Zakaria, The Future of Freedom—Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, W.W. Norton, New York, 2003.

[18] J. D. Fearon, ‘Domestic Politics, Foreign Policy, and Theories of International Relations’, Annual Review of Political Science 1, 1998, pp. 289–313.

[19] S. Blavoukos and D. Bourantonis, ‘Foreign Policy Change’, Oxford Research Encyclopedias, 26 October 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.424 (accessed 10 March 2023).

[20] C. Layne, ‘The unbearable lightness of soft power’, in I. Parmar and M. Cox (eds), Soft Power and US Foreign Policy: Theoretical, Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Routledge, London, 2010, pp. 51–82.

[21] I. Bakalov, ‘Setting soft power in motion: Towards a dynamic conceptual framework’, European Journal of International Relations, 26(2), 2020, pp. 495–517.

[22] D.A. Baldwin, Power and International Relations: A Conceptual Approach, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2016, pp. 164–171.

[23] Joseph S. Nye, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, Basic Books, New York, 1990, p. 267; Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Public Affairs, New York, 2004, p. 7.

[24] J. Bially Mattern, ‘Why “soft power” isn’t so soft: Representational force and the sociolinguistic construction of attraction in world politics’, Millennium, 33(3), 2005, pp. 583–612; L. Hagström and C. Pan, ‘Traversing the soft/hard power binary: The case of the Sino-Japanese territorial dispute’, Review of International Studies, 46(1), 2020, pp. 37–55; A. Simonyi and J. Trunkos, ‘Eliminating the soft/hard power dichotomy’, in A. Jehan and A. Simonyi (eds), Smarter Power: The Key to a Strategic Transatlantic Partnership, Center for Transatlantic Relations, Washington, DC, 2014, p. 16; S.B. Rothman, ‘Revising the soft power concept: What are the means and mechanisms of soft power?’, Journal of Political Power, 4(1), 2011, pp. 49–64.

[25] See also Nye, Soft Power, op. cit, pp. 7–8.

[26] C. Atkinson, Military Soft Power: Public Diplomacy through Military Educational Exchanges, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, 2014.

[27] G.M. Gallarotti, ‘Soft power: What it is, why it’s important, and the conditions for its effective use’, Journal of Political Power, 4(1), 2011, p. 34.

[28] G.M. Gallarotti, Cosmopolitan Power in International Relations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, pp. 23–8; D.W. Kearn, ‘The hard truth about soft power’, Journal of Political Power, 4(1), 2011, pp. 71–72.

[29] Baldwin, op. cit, pp. 165–167.

[30] Gallarotti, ‘Soft power’, op. cit, p. 33.

[31] M. Barr, V. Feklyunina, and S. Theys, ‘The soft power of hard states’, Politics, 35(3–4), 2015, pp. 213–215; Y. Fan, ‘Soft power: Power of attraction or confusion’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(2), 2008, p. 135; J.E.C. Hymans, ‘India’s soft power and vulnerability’, India Review, 8(3), 2009, pp. 236–7.

[32] C. Walker, ‘What Is “Sharp Power”?’, Journal of Democracy, 29(3), 2018, p. 18.

[33] Ibid., p. 18.

[34] C. Walker and J. Ludwig, ‘From “soft power” to “sharp power”: Rising authoritarian influence in the democratic world’, in International Forum for Democratic Studies (ed.), Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence, National Endowment for Democracy, Washington, DC, 2017, p. 13.

[35] Walker, op. cit, p. 18.

[36] A. Lührmann and S. Lindberg, ‘A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it?’, Democratization, 26(8), 2019, pp. 1095–1113.

[37] Walker, op. cit, pp. 18–19.

[38] Nye, Soft Power, op. cit, p. 7.

[39] Ibid., pp. 14, 17; Kearn, op. cit, p. 78; M. Kroening, M. McAdam, and S. Weber, ‘Taking soft power seriously’, Comparative Strategy, 29(5), 2010, p. 413.

[40] B.M. Blechman, ‘Book review “Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics”’, Political Science Quarterly, 119(4), 2004, p. 680.

[41] Fan, op. cit, p. 150.

[42] Y.K. Küçük, ‘Turkey’s Africa Policy: Success Story or Inflated Narrative?’, The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, 16 April 2021, https://agsiw.org/turkeys-africa-policy-success-story-or-inflated-narrative/ (accessed 10 January 2022).

[43] M. Özkan and A. Kanté, ‘West Africa and Turkey forge new security relations’, ISS Today, 31 March 2022, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/west-africa-and-turkey-forge-new-security-relations (accessed 4 April 2022).

[44] V. İpek and G. Biltekin, ‘Turkey’s Foreign Policy Implementation in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Post-International Approach’, New Perspectives on Turkey, 49, 2013, pp. 121–56.

[45] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Turkey-Africa relations, 2021, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey-africa-relations.en.mfa (accessed 3 November 2021).

[46] Kavak and Aktas, op cit.

[47] Küçük, op cit.

[48] Y. Turhan, ‘Turkey’s Foreign Policy to Africa: The Role of Leaders’ Identity in Shaping Policy’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(6), 2021, p. 1336.

[49] S. Cevik, ‘Reassessing Turkey’s Soft Power: The Rules of Attraction’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 44(1), 2019, pp. 50–71; Davutoğlu, op cit; Kalın, op cit.

[50] G. Bacik and I. Afacan, ‘Turkey Discovers Sub-Saharan Africa: The Critical Role of Agents in the Construction of Turkish Foreign-Policy Discourse’, Turkish Studies, 14(3), 2013, p. 489.

[51] F. Tih, ‘Erdogan: “We know very well who exploited Africa’, AA, 25 January 2017, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/erdogan-we-know-very-well-who-exploited-africa/734731 (accessed 2 January 2022).

[52] D. Cihangir-Tetik and M. Müftüler-Baç, ‘A Comparison of Development Assistance Policies: Turkey and the European Union in Sectoral and Humanitarian Aid’, Journal of European Integration, 43(4), 2021, p. 439.

[53] Y. Tüyloğlu, ‘Turkish Development Assistance as a Foreign Policy Tool and Its Discordant Locations’, CATS Working Paper, 2, 2021, p. 14.

[54] M. Kamp, ‘Authoritarian Donor States and their Engagement in Africa’, KAS International Reports, 2, 5 July 2021, p. 62.

[55] Publish What You Fund, Aid Transparency Index 2020, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/PWYF_AidTransparency2020_Digital.pdf (accessed 2 April 2022).

[56] F. Taştekin, ‘Drone Sales Could Dampen Turkey’s African Venture—Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East’, Al Monitor, 21 December 2021, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/12/drone-sales-could-dampen-turkeys-african-venture (accessed 3 March 2022).

[57] D. Soyaltin-Colella and T. Demiryol, ‘Unusual middle power activism and regime survival: Turkey’s drone warfare and its regime-boosting effects’, Third World Quarterly, 2023, pp. 1–20. DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2022.2158080.

[58] F. Donelli, ‘UAVs and beyond: Security and Defence Sector at the Core of Turkey’s Strategy in Africa’, MegaTrends Africa Policy Brief, 2, 2022, p. 4.

[59] Taştekin, op cit.

[60] G. Angey-Sentuc and J. Molho, ‘A critical approach to soft power: Grasping contemporary Turkey’s influence in the world’, European Journal of Turkish Studies, 21, 2015, http://journals.openedition.org/ejts/5287 (accessed 5 October 2021).

[61] J. Heibach, ‘Sub-Saharan Africa: A Theater for Middle East Power Struggles’, Middle East Policy, 27(2), 2020, pp. 69–80.

[62] J. Mosley, Turkey and the Gulf States in the Horn of Africa: Fluctuating Dynamics of Engagement, Investment and Influence, The Rift Valley Institute, Nairobi, 2021.

[63] T. Alaranta, ‘Turkey in Africa: Chasing Markets and Power with a Neo-Ottoman Rhetoric’, FIA Briefing Paper, 280, 2020, p. 7.

[64] G. A. Flores-Macías and S. E. Kreps, ‘The Foreign Policy Consequences of Trade: China’s Commercial Relations with Africa and Latin America, 1992–2006’, The Journal of Politics, 75(2), 2013, pp. 357–71.

[65] R. O. Keohane and J. S. Nye, Power and Interdependence, 4th ed., Longman, Boston, 2011, p. 9.

[66] The Gülen Movement is a transnational Islamic network which gained its recognition for its schools and interfaith dialogue activities. Nonetheless, its overpoliticization and empowerment in Turkey’s civil-military bureaucracy created a rift between the AKP and the movement. The government accused the GM of the 2016 coup attempt and designated it as the Gülenist Terror Organization (FETÖ). While the GM has always had its critics and sceptics in Turkey, it managed to recruit wide support for its activities overseas. C. Tee, ‘The Gülen Movement: Between Turkey and International Exile’, in M. A. Upal and C. Cusack (eds), Handbook of Islamic Sects and Movements, London: Brill, 2021, p. 87.

[67] R. T. Erdoğan, ‘Speech by H.E. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the President of the Republic of Turkey’, Second Turkey-Africa Partnership Summit, 21 November 2014, http://afrika.mfa.gov.tr/21-november-2014-speech-by-HE-recep-tayyip-erdogan-the-president-of-the-republic-of-turkey.en.mfa (accessed 1 March 2022).

[68] One should note the multiplicity and changing priorities of foreign policy goals. For instance, the particular case of Turkey’s official development aid does not fully reflect its carrot-and-stick approach; its allocation does not always correlate with recipient countries’ respective stances on the Gülen schools in their country. Turhan, op cit.

[69] J. Czerep, ‘Turkey’s Soft-Power Crisis in Africa’, PISM Policy Paper, 3(173), 2019, p. 5.

[70] Donelli, ‘UAVs and beyond’, op. cit, pp. 4–5.

[71] Czerep, op cit, p. 5.

[72] A. Irede, ‘Nigeria Places Erdogan’s Enemies on Surveillance in Exchange for Turkey’s Military Assistance’, The Africa Report, 21 December 2021, https://www.theafricareport.com/159327/nigeria-places-erdogans-enemies-on-surveillance-in-exchange-for-turkeys-military-assistance/ (accessed 1 March 2022).

[73] One key source that helps tracking the Turkish state’s incremental control over societal power resources is the ‘CSO entry and exit’ indicator (v2cseeorgs) provided by the Varieties of Democracy project. This indicator measures the extent to which ‘the government achieve[s] control over entry and exit by civil society organizations (CSOs) into public life’. In 2010, Turkey scored close to 2 (1,98), indicating a situation of ‘moderate control’. In 2016, Turkey plummeted to 0.65, thus hovering between ‘monopolistic control’ (0) and ‘substantial control’ (1), with the latter score describing a situation in which ‘The government licences all CSOs and uses political criteria to bar organizations that are likely to oppose the government. [… It] actively represses those who attempt to flout its political criteria and bars them from any political activity’. Until 2022, the Turkey’s score slightly rose to 0.83 again, still marking a sharp overall decline when compared to the highest score (2.27) reached in 2003 though, i.e., roughly one year into the rule of the AKP government. For the data and the codebook (v13, March 2023, p. 195), see https://www.v-dem.net/ (accessed 10 March 2023).

[74] M. Ozkan, ‘Does “Rising Power” Mean “Rising Donor”? Turkey’s Development Aid in Africa’, Africa Review, 5(2), 2013, p. 145.

[75] D. Shinn, Hizmet in Africa, Tsehai, Los Angeles, 2015.

[76] Czerep, op. cit, p. 6.

[77] G. Angey, ‘The Gülen Movement and the Transfer of a Political Conflict from Turkey to Senegal’, Politics, Religion&Ideology, 19(1), 2018, p. 54.

[78] Akpınar, op. cit, pp. 743–744.

[79] F. Donelli, Turkey in Africa: Turkey’s Strategic Involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa. London: I.B. Tauris, 2021.

[80] The authors’ dataset rests on open sources and official reports from the relevant institutions and includes data on the Gülen and Maarif schools, TIKA offices, Turkish embassies, and Turkish Airlines routes, as well as security and military agreements the Turkish state has signed with sub-Saharan African countries. See: http://tur-ssa.giga-set.info.

[81] H. Taş, ‘A History of Turkey’s AKP-Gülen Conflict’, Mediterranean Politics, 23(3), 2018, pp. 395–402.

[82] E. Guner, ‘The Scalar Politics of Turkey’s Pivot to Africa’, POMEPS, 16 June 2020, https://pomeps.org/the-scalar-politics-of-turkeys-pivot-to-africa (accessed 1 December 2021).

[83] Donelli, ‘UAVs and beyond’, op. cit, p. 5.

[84] Turhan, op cit, p. 803.

[85] A. Sıradağ, ‘The Rise of Turkey’s Soft Power in Africa: Reasons, Dynamics, and Constraints’, International Journal of Political Studies, 8(2), 2022, pp. 1–14.

[86] These NGOs are not only passive receivers of state assistance but attend official meetings and make formal contributions to Turkey’s agenda-setting in Africa policy. Turhan and Bahçecik, op cit.

[87] E. Guner, ‘NGOization of Islamic Education: The Post-Coup Turkish State and Sufi Orders in Africa South of the Sahara’, Religions, 12(1), 2020, pp. 1–22.

[88] Czerep, op cit, p. 6.

[89] R. Hinnebusch and A. Ehteshami, ‘The analytical framework’, in R. Hinnebusch and A. Ehteshami (eds), The Foreign Policies of Middle East States, Lynne Rienner, Boulder, 2002, p. 16.

[90] H. Taş, ‘The Formulation and Implementation of Populist Foreign Policy: Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean’, Mediterranean Politics, 2020, DOI: 10.1080/13629395.2020.1833160.

[91] Tüyloğlu, op cit, p. 25.