Abstract

“Neglected Tropical Diseases” (NTDs) are lesser-known diseases, existing in the poorest communities in the shadow of the high-profile and well-funded “Big Three” (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria). Blame for neglect is pointed towards protagonists, which include pharmaceutical companies, for not investing in diseases of poverty and donor governments and NGOs, for directing attention to high mortality diseases. Yet, other sites of neglect tend to be ignored, such as global governance priorities. Exclusion of NTDs from the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) in 2000 started the ball rolling for an advocacy campaign to raise these diseases higher up the global health agenda. The MDG omission was used as a frame by advocates to highlight neglect and led to inclusion in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs, set out in 2015, now include NTDs alongside HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases in a goal to end epidemics by 2030. However, reframing based on a concept of neglect was not sufficient to ensure a place at the top of global health priorities. The NTD problem also needed to be made measurable, with metrics set in evidence-based logic, to provide a rationale for intervention and track progress towards quantifiable success.

1. Introduction: Listing Diseases

Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) are a collection of 22 communicable diseases afflicting over 1 billion of the world population (Watts Citation2017). They are immensely diverse, with broad coverage across 149 tropical and subtropical countries, hitting the poorest communities the hardest. Including viral, helminth, bacterial, and protozoal infections, they cross many pathogenic and geographical boundaries, but occur predominantly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists NTDs in Box 1 below as:

Buruli ulcer

Chagas disease

Dengue and Chikungunya

Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)

Echinococcosis

Foodborne trematodiases

Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)

Leishmaniasis

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease)

Lymphatic filariasis

Mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis and other deep mycoses

Onchocerciasis (river blindness)

Rabies

Scabies and other ectoparasites

Schistosomiasis

Soil-transmitted helminthiases

Snakebite envenoming

Taeniasis/Cysticercosis

Trachoma

Yaws (Endemic treponematoses)

During 2000–2015, from the introduction of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to commencement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), NTDs consisted of a group of 17 diseases. The category has since shown to be sought after and, in 2017, five more diseases were added to the list: chromoblastomycosis and other deep mycoses, scabies and other ectoparasites, and snakebite envenoming (WHO NTD-STAG Working Group Citation2018). The criteria for inclusion of new diseases had been formalised the previous year, by the WHO Strategic and Advisory Group (STAG) for NTDs, who were tasked with developing a “systematic, technically driven process for the adoption of additional diseases” (WHO Citation2016a). Conditions would be considered for NTD classification as important health issues for the poor but without a WHO programme home, “for the purpose of advocacy to motivate action or research for the development of new solutions in low resource settings” (WHO Citation2016a, 2). Today, institutional ownership of the process to decide what new diseases are constituted as NTDs lie squarely with WHO NTD-STAG as advisory group to WHO for the control of NTDs and reports directly to WHO’s Director-General. The group which meets annually to assess progress on NTD milestones and targets does not accept all classification proposals and, in 2018, rejected a proposal to include “scorpion sting envenoming” (WHO NTD-STAG Working Group Citation2018).

NTDs have not always been a sought-after category. As the name would suggest, these diseases have been deemed “neglected”. McInnes and Lee (Citation2012) have pointed out that there is a hierarchy of diseases in attracting funding, leading to underfunding of health conditions which cause millions of deaths each year. Compared to the “Big Three” – HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria – NTDs have been overlooked. These three diseases were propelled as targets for global attention, in 2000, as the sixth out of the eight poverty reduction goals: “ … to combat AIDS, malaria and other diseases” (United Nations Statistics Division Citationn.d., Accessed 2/4/14). They were singled out as high mortality global diseases. Coming from the back of the 1980–1990s it is not a surprise that HIV/AIDs would be targeted, although a spotlight on malaria and tuberculosis was not so obvious. Kamat (Citation2013) explains the shift in perceptions of malaria between 2001–2013, stating that it was no longer a disease confined to the “tropics” but “placed on par with HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis as a global killer, at least discursively, demanding renewed attention and enormous resources” (221). Also, tuberculosis was not initially grouped with malaria and HIV/AIDs in the MDGs but included soon after through The Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria.

It was the increased focus on the Big Three, and omission of NTDs from the MDGs, that brought momentum to an advocacy campaign to raise these diseases higher up the global health agenda. While other omissions from the MDGs have been noted, these tended to be topic areas with large and powerful constituencies, excluded on the grounds of political contentiousness – reproductive health services, human rights, and gender empowerment (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2011, 27–28). Following objection from health advocates, some omissions were corrected by 2005 through inclusion in MDG targets (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2011, 27–28). Advocates of these issue areas have also noted the displacement effects of The Big Three (Shiffman Citation2006). On the other hand, advocates for NTDs, still needed to build an effective advocacy lobby and an argument for why exclusion from the MDG was an omission in the first place. The neglect label capitalised on the exclusion by the MDGs and helped to define NTDs, bringing together inconvenient diseases, with no obvious home within the organisational machinery of global health funding, programmes, and institutions. . below shows the list of “NTDs in 2000–2015” created by the WHO Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases in 2005. These 17 diseases compare with 7 tropical diseases listed by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) created in 1974.

Table 1. Comparing WHO list of Post-MDG WHO NTDs to Pre-MDG WHO NTDs (Compiled from: WHO Citation2015, Accessed 2/4/16; Lucas Citation2013)

After the establishment of a Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, the list expanded but excluded malaria. The changes in NTDs as a category are tracked throughout the paper with the aim of tracing the advocacy process undertaken to make the NTD category desirable to join. I do not intend to explain the impact of this individual achievement of SDG inclusion per se but use the MDG–SDG lens to view the progression of NTD advocacy. Section 2 describes the methods used to understand the strategies employed to advocate for the new NTD category, building on elite interviews with those involved in the advocacy process, while Section 3 outlines how NTDs have fared variously in global governance priorities over time. Section 4 covers the actions taken in reframing NTDs to make them comparable and rankable, concentrating on two metrics for the burden of disease and cost-effectiveness of interventions: the “Disability-adjusted life year” (DALY) and the “50 cents per person”. Section 5 discusses the appeal and limitations of using metrics as a form of advocacy, before exploring the results of the quantification efforts through “The London Declaration”; and finally, the inclusion of NTDs in the SDG is discussed in Section 6.

2. Methods

In setting out how advocacy for NTDs has proved successful through metrics, I draw on a larger project about the policy history of NTDs, involving a series of over 55 semi-structured interviews from 2013–2016 with various institutional actors. However, this paper only picks out a smaller part of the interviews with scientists, academics, NGO workers, and policy officials who led the advocacy movement for NTDs. Many of these actors saw inclusion into the SDGs as a sign of achievement and ongoing accountability of the global health community.

Through an initial literature review, I identified central actors and then relied on snowball referring for further interviewees. The NTD community is small and could be regarded as elite, with high-profile scientists and policy officials being key participants in the initiation of policy change. Typical interview time varied from forty-five minutes to two hours, mostly held in the participant’s office (or via Skype or telephone when this was not possible). As well as taking detailed notes, all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

I followed five main lines of questioning:

Reason for involvement in NTDs: can you tell me about your background, and what led you to the topic?

Problem and solution understanding and framings: what are the causes of NTDs and what are the proposed ways of solving them?

The approach being taken to address NTDs: which particular strategies are pursued and why?

Reflections on the change of terminology: what is your opinion on the use of the term “NTDs”?

What is the relationship between actors: who are the main partners you work with?

3. Exclusion From the MDGs

Early blame for neglect was pointed at large pharmaceutical companies (so-called “big pharma”) because of a historical lack of research and development (R&D) on NTDs called the “10/90 gap”. The 10/90 gap refers to the resource allocation of global research and development compared to the disease burden. The measure was first stated in a report by The Global Forum for Health Research (Citation2004) – an organisation established in 1998 to promote research and innovation for health and health equity. They found that only 10% expenditure on global R&D is dedicated to problems that primarily affect the poorest 90% of the world’s population (The Global Forum for Health Research Citation2004).

The reason given for the disparity is that market share of pharmaceutical businesses is too small for the 90% of the world who are poor, as big pharma lacks profit incentive (Liese, Rosenberg, and Schratz Citation2010). Health journalist Jeremy Smith calls the 10/90 gap “(A) staggering example of neglect” (Smith Citation2015). The metric is not without critique. Philip Stevens (Citation2004) has argued there has been a change in the epidemiology of developing countries, a change in global health actors, and also a dispute of the size of the burden. Furthermore, NTDs were only a small part of the diseases outlined by the 10/90 gap to not receive a proportional share of R&D investment. Still, a connection between NTDs and the concept of neglect proved a suitable match. Unequal research spending by big pharma has been frequently referred to in media articles on NTDs (Balasegaram et al. Citation2008) and became a part of the argumentation that the problem of NTDs lay in R&D, requiring a change in the innovation system (Bosman and Mwinga Citation2000; Hotez and Pecoul Citation2010; Kilama Citation2009; Unite for sight Citationn.d., Accessed 5/6/13). The 10/90 gap metric thus acted as a hook to attract interest and marked the beginning of metrics being used in relation to NTDs, making a policy case for attention which would result in a new status quo. By the time the SDGs arrived in 2015, NTDs had been elevated as a global health priority, receiving funding and attention. At least $1 billion has been pledged to NTDs from 2006 to 2015, including $114 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and $212 million from the US Agency for International Development (Nordrum Citation2015).

Of course, this level of funding was not always the case. NTDs, as a group, had previously been absent from international planning and goals. The MDGs marked a change in focus from health systems to goal-orientated vertical interventions. The switch required targeted advocacy campaigns from individual disease constituencies to vie for attention and research. As Fukuda-Parr and Hulme describe, this was fortuitous for “ … people who had dedicated their professional lives to particular causes and found themselves with potentially important organizational platforms” (Citation2011, 19–20). I argue, that there were three main reasons why NTDs were not well positioned for advocacy of inclusion in the MDGs: (1) low individual mortality figures; (2) poverty being viewed as the result of a lack of resources, not social or economic inequality; (3) weak quantitative measures in place for tracking burden and monitoring progress.

Firstly, NTDs individually compared poorly with higher-mortality diseases, as policy officials placed increasing importance on disease categories and individual disease severity to ensure effective health spending (Jamison Citation2006). In particular, HIV/AIDS and malaria built on the idea of “health as development” (Biel Citation2000), which emphasised the obvious economic impact of mortality. Secondly, NTDs were ideationally inconvenient. The MDGs indirectly accepted global capitalism as the engine for poverty reduction (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2011, 31) and this causes difficulty in identifying the private sector as failing to provide R&D. Through the MDGs, poverty was not viewed as a relational problem that required the addressing of social and economic equality and redistribution, but more linked to goods and services (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2011, 31). Thirdly, the MDGs were designed to be quantitative in nature, so that results could be tracked to hold governments directly responsible (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2011, 22). The expert group finalising the MDGs wanted to keep the list short and only considered objectives which possessed reasonably robust, internationally comparable data series from 1990 (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2011, 22).

NTDs stood outside, not fitting into neat policy intervention categories based on a specific ideational consensus and would need to demonstrate the economic impact of ill health and morbidity in other ways. In comparison, the Big Three were able to obtain a unique position within the MDGs through what Nattrass called an “unprecedented prior international mobilization, especially around HIV/AIDS, thus both reflecting and facilitating an expanding international health agenda” (Nattrass Citation2014, 232). NTD advocate and Director of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, David Molyneux, saw this as an “ … overfocus on unachievable objectives and targets around the Big Three diseases, which if the planet was viewed by aliens would be seen as the only diseases that existed on the planet” (Molyneux Citation2008, 509).

A reframing exercise of the NTD grouping took place in the early 2000s. A number of editorial-style articles began appearing on “neglected diseases” in high-impact medical journals – The Lancet and British Medical Journal – pointing out the problem of big pharma underinvestment in NTDs and lack of public policy incentives (Trouiller et al. Citation2002; Yamey and Torreele Citation2002 – followed by further studies into the drugs and vaccine deficit: Aerts et al. Citation2017; Cohen, Sturgeon, and Cohen Citation2014; Pedrique et al. Citation2013). Yamey and Torreele specifically targeted big pharma and suggested public-private partnerships (PPPs) as a solution in combining resources. Their argument held that other infectious diseases once neglected (the Big Three) were receiving the attention they deserved through PPPs, and the same could happen for neglected diseases.

In 2005, neglected diseases were specifically branded “Neglected tropical diseases” or NTDs, by scientists Peter Hotez, Alan Fenwick, and David Molyneux, along with others at WHO and related NGOs, coining the phrase in a joint paper (Molyneux, Hotez, and Fenwick Citation2005). In 2005, the Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases at WHO “formally rebranded this area of work, previously vaguely defined as ‘other communicable diseases’ or ‘other tropical diseases’, meaning other than malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS as neglected tropical diseases” (Savioli, Montresor, and Gabrielli Citation2011, 486). The goal of the scientists, through the coining of NTDs, was to further develop organisations they founded or were aligned with () as vehicles to operationalise the attention created and better fund activities already underway. The diseases they focused on were various helminths amenable to mass drug administration (MDA).

Table 2. Summary of academic specialisms and interventions of the three key scientists advocating for NTDs (compiled by author)

For Molyneux, the NTDs did not arise from the MDG exclusion but this acted as rhetorical device to frame neglect and demonstrate the historical sidelining of NTDs in funding streams and priority settings (Second interview with author, Molyneux, 2016). Therefore, the MDG argument was applied post hoc and was not itself a spur for action. Molyneux was surprised by how the term NTD, which grouped a large number of individual diseases together, had caught on: “None of this was done deliberately … we couldn’t persuade a donor, be a bilateral donor … to actually buy in to the concept of a single disease, we had to find another thing, and I was frustrated” (second interview with author, Molyneux, 2016).

The grouping of NTDs under the banner of neglect met a receptive environment – several factors meant that the timing was right to be championed. The field of global health had risen to prominence for problems of concern in policy, governance, philanthropy, and funding. As McInnes and Lee describe: “ … the new millennium proved something of a turning point. Levels of foreign aid and the political priority given to development both increased substantially … but also by a proliferation of global health actors and initiatives” (Citation2012, 61). One of the debates that gained traction was about “access to medicines”, creating a challenge to the traditional pharmaceutical model (McInnes and Lee Citation2012, 61). While access to NTD medicines has not been the main barrier to prevention and treatment of NTDs, such a debate emphasised the imperative for the pharmaceutical system to better cater to global public health needs. Pressure on big pharma helped establish extensive drug donation programmes for NTDs and new models of working alongside public-sector partners through PPPs and PDPs, including: Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), Infectious Disease Research Institute (IDRI), Sabin Vaccine Institute, and the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC) (Aerts et al. Citation2017).

Also, for established health actors such as WHO, ownership of the NTD problem became part of an objective to re-establish control in global health – especially since the “Big Three” had been adopted as a concern by The Global Fund and UNAIDS. As Kelly Lee (Citation2008) has argued, a defining part of WHO’s activities in the last three decades has been a reassertion of power on global health governance. Focusing on NTDs necessitated more technical knowledge that the institution was well-equipped to supply and a return to focus on poverty-related diseases. Thus, the new framing of NTDs was welcomed through a rise in prominence of global health, the calling on greater responsibility from the private sector through PPPs, and adoption by WHO to expand their influence. However, further agenda-setting avenues were open to be explored to build upon big pharma and WHO interest.

3.1 The London Declaration as an MDG Proxy

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation provided another outlet as a replacement for omission from the MDGs. Bill and Melinda Gates set up their foundation in large-scale philanthropy, applying business approaches modelled on Rockefeller and Carnegie (Solomon Citation2011). The Foundation has achieved a tremendous amount since inception in 1994 as a new global health actor, spending around US$4 billion annually and helping to bring about a “new era of scientific commitment to global health predicaments” (The Lancet Citation2009). The Gates’s have said:

(W)e concentrate on a few areas of giving so we can learn about the best approaches and have the greatest possible impact … We choose these issues by asking: which problems affect the most people, and which have been neglected in the past (Solomon Citation2011, 21).

Here, the concept of neglect was central to the strategy of choosing issues “to solve problems where no one else had stepped in” (Solomon Citation2011, 22). However, this strategy was not obvious. Kari Stoever, former Director of the Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases, recounted how the Gates Foundation was initially sceptical of NTDs – but a few years later, Gates said to her the NTD investment was one of his proudest moments (Interview with author, Stoever, 2016). Described as “relentlessly rational” (Smith Citation2015, 148), Gates had been a believer in Thomas Malthus, the 18/19th-century economist who warned about growth of populations faster than the means of subsistence. Starting with a Malthusian-inspired approach when he began looking at public health in 1997, he focused on birth control: “The logic was crisp and Bill Gates-friendly. Health = resources ÷ people. And since resources, as Gates noted, are relatively fixed, the answer lay in population control” (Smith Citation2015, 148).

However, such thinking would change as he gathered more information. In 2008, he had stepped down from overseeing daily operations at Microsoft to focus full-time on the Foundation and became acquainted with NTDs. He had been given an 82-book reading list by William Foege, former Director of the CDC to learn about global health (Smith Citation2015). His favourite read was the 1993 World Bank Report. Describing what caught his attention:

… ‘It was just a graph that had, you know, these twelve diseases that kill’, said Gates. These included leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, trachoma – the list of leading scourges, preventable at low cost, whose names he’d also never seen before. ‘I thought, This is bizarre’, Gates said. ‘Why isn’t this being covered?’ … (quoted by Smith Citation2015, 145).

Gates committed funding and resources towards NTDs, including for advocacy efforts. In 2007, the Foundation supported the establishment of the “PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases journal” with a $1.1 million grant (The Official PLOS Blog Citationn.d., Accessed 1/5/16) and media campaigns to raise awareness of NTDs, such as “Project Zero” (The Huffington Post Citationn.d.) a schedule of NTD news stories. While advocacy, drug donations and funding of NTDs began to rise, including from Gates, targets and goal-setting were still needed to organise action and would come in the form of “The London Declaration”.

On 30 January 2012, a collection of international politicians, pharmaceutical CEOs and heads of global health organisations – notably Bill Gates and the Director of the World Health Organization, Margaret Chan – descended on London (Regnier Citation2012). This was a meeting for setting goals and forming a collective vision to tackle NTDs, echoing the MDGs 12 years before. Many involved in NTDs highlighted the omission by the MDGs and the concentration of donor attention and funding towards the Big Three. The collective prioritisation at the London Declaration was reminiscent of the MDGs, but directed specifically at NTDs, asking for a continuation of existing drug donation and research programmes with encouragement of further R&D. Through public announcement of commitments, the intention was to sustain programmes and drug supply, advance R&D collaboration, and fund implementation and technical support, in a coordinated action by 2020.

Gates and others had been persuaded, by metrics being used, to make a policy case for attention. NTDs were revealed to have a high burden but a low cost of prevention. However, these metrics were a long time in the making. In particular, the health economist Christopher Murray had been an influential figure behind the drive for better tools for measurement in health and had authored the 1993 World Bank Report that had caught Gates’ attention. Murray, with Alan Lopez, developed the DALY and the Gates Foundation now uses the concept of DALYs widely to help determine priorities and evaluate potential projects.

4. Metrics to Present a Problem and a Solution

Before metrics were deployed successfully in NTD advocacy, the neglect framing located tropical diseases within an emotional appeal. Nunes (Citation2016) has argued that the idea of neglect positions those affected by disease with vulnerability through an imposed harm from those in positions of power. Therefore, the concept of a neglected disease casts a net on what is morally acceptable, who is responsible and to blame, prompting action on that emotional imperative (bid.) However, Nunes argues that increased attention does not mean that an issue is adequately addressed, as moments or cycles of attention belie more deep-seated structural underpinnings. Such an observation mirrors the advocacy that would develop for NTDs. Emotional appeal did not automatically translate into NTDs being better addressed by health actors. To find a place in the machinery of global health, the next step after the framing of neglect was the use of measurement and evidentiary practices to put metrics on “neglectedness”. Improved metrics would serve to increase the visibility of NTDs, and measurement of the degree of neglect was needed to make persuasive arguments. WHO noted this need in 2007, stating: “Lack of reliable statistics on the burden of NTDs has hampered raising awareness of decision-makers on NTDs and zoonoses.Footnote1 Accurate assessment of the disease burden is crucial to prioritize use of limited resources, provide timely treatments and prevent diseases” (WHO Citation2007, 14).

Furthermore, metrics do more than simply represent reality. Advocacy by presenting evidence has already been noted (Manderson et al. Citation2009; Maio Citation2014) and the strongest form termed “evidence-based advocacy (EBA)” (Storeng and Béhague Citation2014). However, the metrics used for NTDs and their popularisation formed a type of advocacy in itself. Measurement as advocacy comes through the ability of metrics to communicate information, ideas, and arguments. For NTDs the metrics that performed a role of advocacy were:

The “disability-adjusted life year” showing the burden of disease through a chronic or high-morbidity character of NTDs, and;

“50 cents per person” pointing to cost-effective interventions for a core of NTDs.

4.1. The “Disability-adjusted Life Year”

The “Disability-adjusted life year” (DALY) measure was pioneered by health economist Christopher Murray and epidemiologist Alan Lopez. Their work is described as a “ … systematic effort to quantify the comparative magnitude of health loss due to diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and geography over time” (IHME Citationn.d., Accessed 2/4/14). To begin with, the DALY measure did not appear as a very useful advocacy tool for NTDs. David Canning, a public health expert invited to contribute to the first WHO NTD report, contended that the measurement of NTD impact was a reason for their neglect, because they “ … do not score high from a disease burden perspective, and this lies at the crux for their neglect” (in WHO Citation2005). As Canning argued, NTDs have been subject to the moral imperative of the “rule of rescue” to prioritise diseases that pose imminent threat to life, while chronic and non-life-threatening conditions are overlooked (WHO Citation2005).

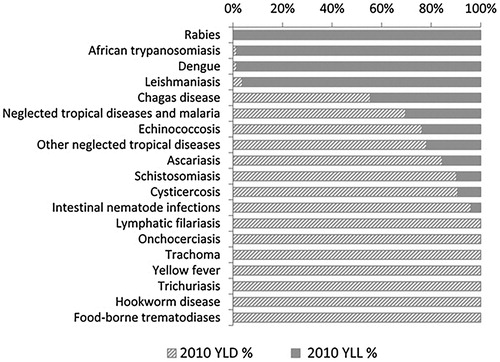

The DALY came to be useful for the NTD cause, due to the theories and ideas embedded in indicators (Davis, Kingsbury, and Merry Citation2012). The intention of the DALY was to capture morbidity from the example of diseases causing loss of life years, by providing standardised estimates for years of life lost due to disease, injury, and risk factors over time (Hay et al. Citation2017). One DALY is equal to the loss of one healthy life year, as the sum of: Years of Life Lost (YLL) due to premature mortality in the population and Years Lost due to Disability (YLD) for people living with the health condition or its consequences (WHO Programmes Citation2015, Accessed 2/4/15). As the metric combines both mortality and morbidity, it has popularised the idea that morbidity is a major concern and is measurable, therefore action is taken (Adams Citation2016). This idea eventually worked in favour of NTDs, as diseases that cause more disability than death. Even though NTDs affect over one billion people, they cause fewer deaths than high-mortality diseases, with recent estimates at approximately 170,000 deaths each year (Watts Citation2017). As shown in . below, NTDs tend to cause more of the “Years Lost due to Disability” than “Years of Life Lost”.

Figure 1. YLDs and YLL of NTDs in ‘The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010’ (Hotez et al. Citation2014).

As the metric has grown in complexity, further NTDs have been included, as well as more detailed reporting on their disabling effects (Watts Citation2017). NTDs can now be described as: “ … the fourth most devastating group of communicable diseases behind lower respiratory infections, HIV, and diarrheal diseases – ranking higher than either malaria or tuberculosis” (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Citation2015). Furthermore, to become an attractive proposition for policy, advocacy for NTDs used the reasoning for shifting attention from mortality towards morbidity through “high return on investment” with low-cost interventions having productivity and economic development impacts to “attract the ear of finance ministers” (WHO Citation2005, 11). DALYs have since been utilised by advocates to convey the message that the burden of disease is high. Below are the types of headlines employed.

The End Fund: “When measured in disability-adjusted life years, the NTD burden is greater than that of malaria or tuberculosis, and ranks among the top four most devastating groups of communicable diseases, along with lower respiratory infections, HIV/AIDS, and diarrheal diseases” (The END Fund Citationn.d., Accessed 4/6/16).

Scientists Hotez, Fenwick, Molyneux and others: “By some estimates, the neglected tropical diseases are second only to HIV/AIDS as a cause of disease burden, resulting in approximately 57 million DALYs annually” (Hotez et al. Citation2006).

Instead of being problematised as comparatively low mortality diseases, DALYs characterise NTDs as high in importance by being high-morbidity diseases. In the section that follows, I turn to understanding neglect in solutions that are proposed in order to tackle NTDs.

4.2. “50 cents per person”

The idea that many NTDs are treatable for a small amount of money demonstrated how the solution could be a quantifiable, cost-effective intervention. For HIV/AIDs, cost-effective treatment of anti-retrovirals was also required before widespread adoption in global governance priorities (Fehling, Nelson, and Venkatapuram Citation2013). Five NTDs (trachoma, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and soil-transmitted helminths) are being addressed primarily through Mass Drug Administration (MDA) of anthelminthics and antiparasitics, along with antibiotics. According to the NGO ENVISION: “(MDA) is the administration of drugs to entire populations, in order to control, prevent or eliminate common or widespread disease” (ENVISION Citationn.d., Accessed 2/4/14). MDA as regular and systematic administration of medicines to populations is hailed as an effective policy intervention (WHO Citation2012).

The NGO Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases calls this “the solution” on their webpage: “Unlike many other global health problems we face today, the solution is relatively simple. For just 50 cents, we can provide a person with treatment against the most common NTDs for an entire year” (Global Network Citationn.d., Accessed 9/12/12). It is a cheap treatment, according to the CDC: “one of the best buys in public health – with a low cost of about $0.10 to $0.50 per person/year and the benefit of helping prevent or treat several different diseases” (CDC Citation2010, 2). As Warren Lancaster, a senior vice president at NGO The End Fund, has put it: “for the donor community that’s a very attractive proposition” (Interview with author, Lancaster, 2014).

Scientist Alan Fenwick similarly describes MDA for NTDs as “ … the best buy for public health” (APPMG Citation2009, 14), acting as a marketing tool to “sell” an attractive solution. It proved to be a successful pitch for Fenwick to catch the eye of Alan McCormick, a partner at global investment firm Legatum, following an interview Fenwick gave to the Financial Times in 2006:

… a phrase from an interesting article on philanthropy implanted itself in his mind: that such treatable ailments ‘do not need innovation but simply modest funding and a little imagination in order to distribute drugs to those in need’ … He was inspired by the idea that it might be possible to change the lives of millions, to free them from the burden of devastating illness, for as little as 50 cents per person (The Legatum Group Citationn.d., Accessed 4/30/16).

The result was that the Legatum Foundation established The END Fund as an NGO to finance control initiatives and new programmes to control or eliminate the five most common NTDs.

5. Appeal and Limitations of Metrics as Advocacy

The DALY and the “50 cents per person” metrics both provided a level of quantification that assisted in advocating for NTDs. Winkler and Satterthwaite (Citation2017) point out that metrics also inspire action, in being pegged to specific targets that help translate aspirational language into implementation. Through the DALY measure of disease burden, morbidity is highlighted, and through the cost-effectiveness measure of “50 cents per person” an attractive intervention is presented. Both open the door for the NTD problem to be dealt with. Thus, metrics on the one hand measure a current state and monitor progress, but on the other concentrate efforts and attention (Winkler and Satterthwaite Citation2017, 1075–6).

Metrics have a performative role in the way a problem is understood and dealt with: more is entailed than the final figures produced. What is emphasised or remains hidden and ignored is my main contention about the use of metrics as an advocacy strategy. As Davis et al. describe, the appeal of quantification is to give decision-makers the appearance of objectivity so that “decisionmaking processes that rely on indicators can be presented as efficient, consistent, transparent, scientific, and impartial” (Citation2012, 84). What lies beneath the surface are the origins of metrics, how they are constituted, and how supporting data is collected and made available.

The 10/90 gap argument initially framed the problem of NTDs as being mainly on a pharmaceutical basis, due to lack of R&D. The emphasis on pharmaceutical responsibility has tended to get confused with treating NTDs as “for-profit” diseases. For example, access for poorer countries to HIV/AIDS treatments developed in wealthier countries is problematic because intellectual property rights protect for-profit research efforts. However, NTDs are generally not-for-profit diseases, without significant access barriers that need dismantling. Mary Moran outlines this argument in her critique of WHO pilot projects beginning in 2014 to fund research for NTDs. Her claims are presented in the provocatively-titled Nature article, “WHO plans for neglected diseases are wrong” (Moran Citation2014). When interviewed, she summed up her paper: “I understand that there are problems with accessing commercial and intellectual property, but we don’t have that problem in neglected diseases, and the solutions you’re proposing don’t fit here” (Interview with author, Moran Citation2014). Therefore, use of the 10/90 gap, as a compelling metric to explain the problem of NTDs being with big pharma, constrains the understanding and responsibility for these diseases, within a limited set of actors and ways of dealing with them.

Similarly, for the DALY metric, a concentration on quantifying morbidity is an understanding of diseases in economic terms rather than values of equality, justice and rights. DALYs are a statistically quantifiable metric but do not sit in isolation and go toward creating the “Global Burden of Disease index” (Hay et al. Citation2017), ranking diseases according to their DALY score. Therein comes the importance of measuring and creating metrics at all – to be able to list, hierarchically and relationally, problems for policy that allow comparison and prioritisation of funding and resources. However, the DALY helps hide the political and social origins of NTDs by listing diseases on grounds of need and the facade of ideological or political impartiality. This ranking is a type of depoliticisation that does not engage with the advocacy of groups petitioning politicians on the interests, values and causes they support as part of democratic processes.

Even the metric describing the solution for NTDs is not without problems. “50 cents per person” presented by NGOs such as The Global Network Against Neglected Tropical Diseases emphasises MDA of drugs as a central strategy. The five NTDs addressed through MDA are then focused upon, as is the involvement of big pharma through drug donation. Other concerns include a worry of drug resistance from continued usage on this scale (Barry et al. Citation2013) and also the argument of anthropologists Parker and Allen (Citation2011) who found acceptance by local communities and over-promise of benefits problematic: “Strategies primarily rely on the mass distribution of drugs to adults and children living in endemic areas. The approach is presented as morally appropriate, technically effective, and context-free.” (Citation2014, 224). Their argument is that NTD advocacy has been undertaken with a high level of optimism without fully considering negative aspects of campaigns or non-technical causes of neglect. Promissory claims are put forward, stemming from aspirations to achieve the MDGs by “making poverty history” (Parker and Allen Citation2011, 2).

6. Conclusion: SDG Inclusion and Beyond

Promises and optimism have worked. NTDs have now joined the ranks of the Big Three as part of the “gang of four” in the SDGs, set out in 2015 (Smith and Taylor Citation2013). NTDs fall under SDG target 3.3: “By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, waterborne diseases and other communicable diseases” (Target 3.3; see: Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform Citationn.d.).

However, measuring NTDs remains problematic. Though HIV infections, tuberculosis, malaria and Hepatitis B all have indicators on reduction of incidence in the population, the NTD indicator is much less specific, referring to a reduction in the “number of people requiring interventions against neglected tropical diseases” (Target 3.3; see: Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform Citationn.d.). While the end goal is ambitious – by 2030 to end the epidemic of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in all countries, this depends on definitions of “epidemic” for a group of diseases and there is no targeted level of reduction. The reasoning, described by WHO, is because disease-specific indicators are already measuring progress towards NTD targets. As described by Fitzpatrick and Engels at WHO: “The challenge was to achieve consensus on a single indicator for ‘the end’ of NTDs as a group, without undermining existing disease-specific indicators” (Citation2016, i15). This decision reflects the difficultly in reporting burden of disease for NTDs, but also the wide variance in severity and control from diseases included, with some being very close to eradication.

Therefore, while inclusion in the SDGs is a huge achievement, there are ongoing difficulties in measuring these very heterogeneous diseases that continue to place pressure on the grouping – a concern if metrics are necessary to keep NTDs high up the global health agenda. SDG inclusion does have further consequences for entrenching diseases within the global health policy agenda and organisational machinery. Now that NTDs are a part of the SDGs, they have moved beyond the singular commitments of the London Declaration. Dominic Haslam, a director at NGO Sightsavers, sees NTDs and other so-called lost causes being brought out of the fringes of the development agenda, constitutes a “once-in-a-generation chance to reframe NTDs within a more mainstream approach to health and development” (Haslam Citation2016). Similarly, Molyneux, an NTD advocate, reflected on what the SDGs meant as a sign of achievement and ongoing accountability of the global health community:

To have got NTDs included in the sustainable development goals was, for me, the most important achievement. Had they not been there, I would have thought that our efforts and advocacy would have failed. So I really believe that was a big plus because they’re embedded there semi-legally, and so we can always point to them as being the targets (Second interview with author, Molyneux, 2016).

The original omission from the MDGs may not have harmed the NTD campaign significantly. In fact, exclusion from the MDGs in 2000 set the ball rolling for heightened NTD advocacy. Having evidence of exclusion suited the conceptualisation and framing of “neglect”. The attention and funding that followed for NTDs came from a wide variety of sources, from the Gates Foundation to pharma companies. Inclusion into the SDGs now presents NTD advocates with the question of whether metrics will need to be used in new ways to continue to present the NTD case.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my PhD supervisors Brian Balmer and Jack Stilgoe for all of their support in developing this research topic, and also the ESRC for funding my studentship. In addition, I am very grateful to all those I interviewed for their insights. Finally, this article has benefitted from thoughtful comments by Sarah Loving and Haris Shekeris, and the anonymous reviewers who provided many instructive suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Samantha Vanderslott http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8685-7758

About the Author

Samantha is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Oxford Vaccine Group and the Oxford Martin School, working within the Programme on Collective Responsibility for Infectious Disease. She is also a Junior Research Fellow at Linacre College. She is working on health and society topics, drawing on perspectives from sociology, history, health policy, and science and technology studies (STS).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A zoonosis is any disease or infection that is naturally transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans (WHO Citation2015).

2 A branch of science that deals with the study of insects (Merriam-Webster online dictionary Citationn.d.).

References

- Adams, V. 2016. Metrics: What Counts in Global Health. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Adams, J., K. A. Gurney, and D. Pendlebury. 2012. Global Research Report - Neglected Tropical Diseases. Evidence, Thomson Reuters, (June).

- Aerts, C., T. Sunyoto, F. Tediosi, and E. Sicuri. 2017. “Are Public-Private Partnerships the Solution to Tackle Neglected Tropical Diseases? A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Health Policy 121 (7): 745–754. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.05.005.

- APPMG. 2009. The Neglected Tropical Diseases: A challenge we could rise to – will we? Report for the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases (APPMG). http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/NTD_Report_APPMG.pdf.

- Balasegaram, M., S. Balasegaram, D. Malvy, and P. Millet. 2008. “Neglected Diseases in the News: A Content Analysis of Recent International Media Coverage Focussing on Leishmaniasis and Trypanosomiasis.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2 (5): e234. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000234.

- Barry, M. A., G. G. Simon, N. Mistry, and P. J. Hotez. 2013. “Global Trends In Neglected Tropical Disease Control and Elimination: Impact on Child Health.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 98 (8): 635–641. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-302338.

- Biel, R. 2000. The New Imperialism: Crisis and Contradictions in North–South Relations. Zed Books. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_New_Imperialism.html?id=u1C3AAAAIAAJ&pgis=1.

- Bosman, M., and A. Mwinga. 2000. “Tropical Diseases and the 10/90 Gap.” Lancet 356 (Suppl. s63). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)92049-X.

- CDC. 2010. CDC’s Neglected Tropical Diseases Program. Accessed 22 December 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/ntd/resources/ntd_factsheet.pdf.

- Cohen, J. P., G. Sturgeon, and A. Cohen. 2014. “Measuring Progress in Neglected Disease Drug Development.” Clinical Therapeutics 36 (7): 1037–1042. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.004.

- Davis, K. E., B. Kingsbury, and S. E. Merry. 2012. “Indicators as a Technology of Global Governance.” Law & Society Review 46 (1): 71–104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5893.2012.00473.x.

- The END Fund. n.d. NTD Overview. Accessed 21 December 2016. http://www.end.org/whatwedo/ntdoverview.

- ENVISION. n.d. Mass Drug Administration. Accessed 15 December 2015. http://www.ntdenvision.org/technical_areas/mass_drug_administration.

- Fehling, M., B. D. Nelson, and S. Venkatapuram. 2013. “Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: a Literature Review.” Global Public Health 8 (10): 1109–1122. doi:10.1080/17441692.2013.845676.

- Fitzpatrick, C., and D. Engels. 2016. “Leaving no one Behind: a Neglected Tropical Disease Indicator and Tracers for the Sustainable Development Goals: Box 1.” International Health 8 (Suppl 1): i15–i18. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihw002.

- Fukuda-Parr, S., and D. Hulme. 2011. International Norm Dynamics and the “End of Poverty”: Understanding the Millennium Development Goals. Global Governance. Brill. doi:10.2307/23033738.

- G-FINDER. n.d. Policy Cures: G-Finder. Accessed 25 February 2016. http://policycures.org/gfinder.html.

- The Global Forum for Health Research. 2004. The 10/90 report on health research 2003-2004. http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/20043112798.html;jsessionid=84A7B2585EFA800D7ADFF2BDA8298458.

- Global Network. n.d. Global Network. Accessed 14 September 2015. http://www.globalnetwork.org/.

- Haslam, D. 2016. Is This a Turning Point for Neglected Tropical Diseases? http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/dominic-haslam/tropical-disease_b_7559636.html.

- Hay, S. I., A. A. Abajobir, K. H. Abate, C. Abbafati, K. M. Abbas, F. Abd-Allah, and C. J. L. Murray. 2017. “Global, Regional, and National Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) for 333 Diseases and Injuries and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2016: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016.” The Lancet 390 (10100): 1260–1344. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32130-X.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2015. The U.S. Government and Global Neglected Tropical Diseases. Accessed 7 December 2015. http://kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-u-s-government-and-global-neglected-tropical-diseases/.

- Hotez, P. J., M. Alvarado, M.-G. Basáñez, I. Bolliger, R. Bourne, M. Boussinesq, and M. Naghavi. 2014. “The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010: Interpretation and Implications for the Neglected Tropical Diseases.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 8 (7): e2865. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865.

- Hotez, P. J., D. H. Molyneux, A. Fenwick, E. Ottesen, S. Ehrlich Sachs, and J. D. Sachs. 2006. “Incorporating a Rapid-Impact Package for Neglected Tropical Diseases with Programs for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.” PLoS Medicine 3 (5): e102. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030102.

- Hotez, P. J., and B. Pecoul. 2010. ““Manifesto” for Advancing the Control and Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 4 (5): e718. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000718.

- The Huffington Post. n.d. Project Zero. Accessed 15 February 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/topic/project-zero.

- IHME. n.d. About. http://healthdata.org.

- Jamison, D. T. 2006. “Disease Control Priorities Project.” In Priorities in Health. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Kamat, V. R. 2013. Silent Violence: Global Health, Malaria, and Child Survival in Tanzania. University of Arizona Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=6XxOAQAAQBAJ&pgis=1.

- Kilama, W. L. 2009. “The 10/90 gap in sub-Saharan Africa: Resolving Inequities in Health Research.” Acta Tropica 112: S8–S15. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.08.015.

- The Lancet. 2009. “What Has the Gates Foundation Done for Global Health?” The Lancet 373 (9675): 1577. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60885-0.

- Lee, K. 2008. The World Health Organization (WHO). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203029732.

- The Legatum Group. n.d. United Voices: The Story of the END Fund. Accessed 21 December 2016. http://www.legatum.com/philanthropy/investing-in-development/united-voices/.

- Liese, B., M. Rosenberg, and A. Schratz. 2010. “Programmes, Partnerships, and Governance for Elimination and Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases.” The Lancet 375 (9708): 67–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61749-9.

- Lucas, A. O. 2013. “Research and Training in Tropical Diseases.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 3 (3): 220–224. doi:10.1179/030801878791925958.

- Maio, F. De. 2014. Global Health Inequities: A Sociological Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ese9CgAAQBAJ&pgis=1.

- Manderson, L., J. Aagaard-Hansen, P. Allotey, M. Gyapong, and J. Sommerfeld. 2009. “Social Research on Neglected Diseases of Poverty: Continuing and Emerging Themes.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3 (2): e332. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000332.

- McInnes, C., and K. Lee. 2012. Global Health and International Relations. Polity. Accessed from https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Global+Health+and+International+Relations-p-9780745649467.

- Merriam-Webster online dictionary. n.d. Definition of Entomology. Accessed 12 June 2017. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/entomology.

- Molyneux, D. H. 2008. “Combating the “Other Diseases” of MDG 6: Changing the Paradigm to Achieve Equity and Poverty Reduction?” Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 102 (6): 509–519. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.02.024.

- Molyneux, D. H., P. J. Hotez, and A. Fenwick. 2005. ““Rapid-Impact Interventions”: how a Policy of Integrated Control for Africa’s Neglected Tropical Diseases Could Benefit the Poor.” PLoS Medicine 2 (11): e336. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020336.

- Moran, M. 2014. “WHO Plans for Neglected Diseases are Wrong.” Nature 506 (7488): 267–267. doi:10.1038/506267a.

- Nattrass, N. 2014. “Millennium Development Goal 6: AIDS and the International Health Agenda.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (2-3): 232–246. doi:10.1080/19452829.2013.877427.

- Nordrum, A. 2015, May. How Three Scientists ‘Marketed’ Neglected Tropical Diseases And Raised More Than $1 Billion | Global Network. IBT Times. http://www.ibtimes.com/how-three-scientists-marketed-neglected-tropical-diseases-raised-more-1-billion-1921008.

- Nunes, J. 2016. “Ebola and the Production of Neglect in Global Health.” Third World Quarterly 37 (3): 542–556. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1124724.

- The Official PLOS Blog. n.d. Announcing PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. Accessed 1 May 2016. http://blogs.plos.org/plos/2006/09/announcing-plos-neglected-tropical-diseases/.

- Parker, M., and T. Allen. 2011. “Does Mass Drug Administration for the Integrated Treatment of Neglected Tropical Diseases Really Work? Assessing Evidence for the Control of Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminths in Uganda.” Health Research Policy and Systems 9 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-9-3.

- Parker, M., and T. Allen. 2014. “De-Politicizing Parasites: Reflections on Attempts to Control the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases.” Medical Anthropology 33 (3): 223–239. doi:10.1080/01459740.2013.831414.

- Pedrique, B., N. Strub-Wourgaft, C. Some, P. Olliaro, P. Trouiller, N. Ford, and J.-H. Bradol. 2013. “The Drug and Vaccine Landscape for Neglected Diseases (2000–11): a Systematic Assessment.” The Lancet Global Health 1 (6): e371–e379. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70078-0.

- Regnier, M. 2012. Neglected tropical diseases: The London declaration. https://blog.wellcome.ac.uk/2012/01/31/neglected-tropical-diseases-the-london-declaration/.

- Salaam-blyther, T. 2011. Neglected Tropical Diseases: Background, Responses, and Issues for Congress.

- Savioli, L., A. Montresor, and A. F. Gabrielli. 2011. Neglected Tropical Diseases: The Development of A Brand with No Copyright: A Shift from A Disease-Centred to A Tool Centred Strategic Approach. Accessed 6 February 2016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62524/.

- Shiffman, J. 2006. “Donor Funding Priorities for Communicable Disease Control in the Developing World.” Health Policy and Planning 21 (6): 411–420. doi:10.1093/heapol/czl028.

- Smith, J. N. 2015. Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients. https://books.google.ch/books/about/Epic_Measures.html?id=EvqEoAEACAAJ&pgis=1.

- Smith, J., and E. M. Taylor. 2013. “MDGS and NTDs: Reshaping the Global Health Agenda.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7 (12): e2529. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002529.

- Solomon, L. D. 2011. Tech Billionaires: Reshaping Philanthropy in a Quest for a Better World. Transaction Publishers. https://books.google.com/books?id=jmkdbrhlfK8C&pgis=1.

- Stevens, P. 2004. Diseases of poverty and the 10/90 Gap. Accessed 8 December 2015. http://www.who.int/intellectualproperty/submissions/InternationalPolicyNetwork.pdf.

- Storeng, K. T., and D. P. Béhague. 2014. “Playing the Numbers Game: Evidence-Based Advocacy and the Technocratic Narrowing of the Safe Motherhood Initiative.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 28 (2): 260–279. doi:10.1111/maq.12072.

- Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. n.d. Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed 31 March 2016. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300.

- Trouiller, P., P. Olliaro, E. Torreele, J. Orbinski, R. Laing, and N. Ford. 2002. “Drug Development for Neglected Diseases: A Deficient Market and A Public-Health Policy Failure.” Lancet 22: 2188–2194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09096-7

- United Nations Statistics Division. n.d. Methodology: Standard country or area codes for statistical use (M49). Accessed 15 November 2018. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

- Unite for sight. n.d. The Importance of Global Health Research: Closing The 10/90 Gap. Accessed 20 December 2016. http://www.uniteforsight.org/global-impact-lab/global-health-research.

- Uniting to Combat NTDs. 2014. Delivering on Promises and Driving Progress: The Second Report on Uniting to Combat NTDs. Accessed 14 September 2015. http://unitingtocombatntds.org/sites/default/files/document/NTD_report_04102014_v4_singles.pdf.

- Watts, C. 2017. “Neglected Tropical Diseases: A DFID Perspective.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11 (4): e0005492. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005492.

- WHO. 2005. Strategic and Technical Meeting on Intensified Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Renewed Effort to Combat Entrenched Communicable Diseases of the Poor. Report of an international workshop Berlin, 18–20 April 2005. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69297/1/WHO_CDS_NTD_2006.1_eng.pdf.

- WHO. 2006. Neglected Tropical Diseases: Hidden Successes, Emerging Opportunities. Accessed 6 August 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69367/1/WHO_CDS_NTD_2006.2_eng.pdf.

- WHO. 2007. Global Plan to Combat Neglected Tropical Diseases 2008–2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69708/1/WHO_CDS_NTD_2007.3_eng.pdf.

- WHO. 2012. Guidelines For Assuring Safety of Preventive Chemotherapy (First Edition). Accessed 21 December 2015. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/TZ_Guidelines_Assuring_Safety_Preventive_Chemotherapy.pdf.

- WHO. 2015. Zoonoses. WHO. Accessed 9 December 2015. https://www.who.int/topics/zoonoses/en/.

- WHO. 2016a. Report of the WHO Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Accessed 23 November 2016. www.who.int/neglected_diseases/NTD_STAG_report_2015.pdf.

- WHO. 2016b. The 17 Neglected Tropical Diseases. Accessed 22 March 2014. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/.

- WHO NTD-STAG Working Group. 2018. 11th meeting of the Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Accessed 11 August 2018. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/events/eleventh_stag/en/.

- WHO Programmes. 2015. Metrics: Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY). Accessed 9 December 2015. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/metrics_daly/en/.

- Winkler, I. T., and M. L. Satterthwaite. 2017. “Leaving no one Behind? Persistent Inequalities in the SDGs.” The International Journal of Human Rights 21 (8): 1073–1097. doi:10.1080/13642987.2017.1348702.

- The World Bank. 1993. World Development Report: Investing in Health. World Development Report. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/0-1952-0890-0.

- Yamey, G., and E. Torreele. 2002. “The World’s Most Neglected Diseases.” BMJ 325 (7357): 176–177. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12142292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.176