ABSTRACT

In this paper, we analyse the development of the term “legal capabilities”. More specifically, we do three things. First, we track the emergence and development of the notion of legal capabilities. The term legal capabilities was used in legal research long before the capability approach was introduced in that field. Early on, its conceptualisation mainly reflected elements of legal literacy. In more recent writings, it is claimed that the notion is based on the capability approach. Second, we critically analyse the current use of the term legal capabilities and show that there is no proper theoretical grounding of this term in the capability approach. This is problematic, because it might give rise to misunderstandings and flawed policy recommendations. Third, we suggest some first steps towards a revision of the notion of legal capabilities. Starting from the concept of “access to justice”, legal capabilities have to be understood as the real opportunities someone has to get access to justice, rather than merely as formal opportunities or internal capabilities.

Introduction

People who are confronted with legal problems often struggle to solve them adequately and in a timely fashion. There are different reasons for this, one being the capabilities that a person has to approach such problems. The term “legal capabilities” has been coined to describe these capabilities. It is a term which is not completely new, yet it has been receiving increasing attention during the last decade, ever since Martin Jones first linked it to the capability approach (Jones Citation2009).

In this paper, we analyse the development of the term legal capabilities. More specifically, we do three things. First, we track the emergence and development of the notion of legal capabilities. The term legal capabilities was used in legal research long before the capability approach was introduced in that field. Early on, its conceptualisation mainly reflected elements of legal literacy. In more recent writings, it is claimed that the notion is based on the capability approach. Second, we critically analyse the current use of the term and show that at present there is no proper theoretical grounding of the term legal capabilities in the capability approach. Such a conceptually unsound use of the term legal capabilities is problematic, because it might give rise to misunderstandings and flawed policy recommendations. Third, we suggest a revision of the notion of legal capabilities that is conceptually sound and directly related to the practice of legal scholars by relating it to the central legal notion of “access to justice”. Ultimately, our hope is that such an improved concept of legal capabilities will be useful in the study of people’s access to justice and to related policy development.

The paper is structured as follows. We first give a short introduction to the main ideas of the capability approach that are relevant for the aims of the paper (Section 2). Subsequently, we provide an overview of a number of studies employing the legal capabilities concept and linking it to the capability approach. This overview concerns the earliest papers that focussed on legal literacy (Section 3) and the more recent literature that claims a relation to the capability approach (Section 4). In Section 5 we address the question of why it is a problem to make use of unsound conceptualisations while claiming that they are based on the capability approach. In Section 6 we propose a reconceptualisation of legal capabilities that is, on the one hand, properly grounded in the capability approach, and on the other is directly related to the praxis of legal scholarship by relating it to the idea of access to justice. The final section confirms our conclusions.

The Capability Approach

Readers of this journal are very familiar with the capability approach (see, among others, Sen Citation2005; Alkire Citation2005; Robeyns Citation2005; Nussbaum Citation2011; Robeyns Citation2016). Therefore, we will only very briefly mention some of its core features, which will turn out to be relevant for the goals of this paper.

The capability approach is a normative framework which can be used to assess a wide range of topics from individual well-being to policy changes (Robeyns Citation2017). It seeks to foster people’s human development by trying to enlarge their real opportunities – their so-called capabilities. It promotes the idea of focussing on the freedoms people have to achieve a valuable life (Sen Citation2009, 16), which enable them to achieve valuable functionings. While “capabilities” are considered the opportunities to do something or enjoy a state of being, “functionings” focus on the question of whether these capabilities have been realised. Functionings are therefore described by Sen as “achievements” (Sen Citation1999, 7). Functionings are beings and doings, states such as being healthy, and activities such as working. For example, people are able to do a particular activity but may choose not to do so. It is important to note that we do not look at a single capability, but rather at a capability set, which is the combination of various functionings that a person could obtain. In the complex legal world, the outcome “winning a case at court” will require a wide range of legal and more general capabilities, including the ability to recognise a legal problem, to understand that you have a legal entitlement, to cope with this problem, to find and understand legal information, to live in a country where the judiciary system is sufficiently effective and not corrupt, a country where the rule of law is upheld, and to live in a society where those who seek legal help are not prevented from doing so because of a lack of financial means.

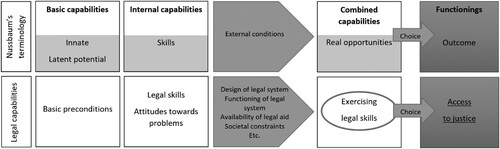

Martha Nussbaum provides further terminological refinement by distinguishing three categories of capabilities, which will turn out to be particularly helpful for our purposes. Nussbaum distinguishes between basic, internal, and combined capabilities. Basic capabilities are innate and might have the potential to develop later in life (Nussbaum Citation2000, 84–85). They are crucial when it comes to developing internal capabilities. Internal capabilities are “states of the person herself that are, so far as the person herself is concerned, sufficient conditions for the exercise of the requisite functions” (Nussbaum Citation1997, 289). These are skills that are present or latent at birth and that are developed during the lifetime of a person. If a person’s physical predisposition allows it, the person can decide whether or not to exercise these skills. Combined capabilities are internal capabilities that are influenced by external conditions (Nussbaum Citation2000, 84–85). Those external conditions can negatively influence internal capabilities and prevent their realisation, but they can also set the necessary circumstances for combined capabilities. The materialisation of those internal capabilities into achievements is not only dependent on whether people make certain choices that are possible because of their capability sets but also depend on the relevant societal circumstances. Nussbaum accounts for this insight by introducing the idea of external conditions that shape a person’s capabilities (Nussbaum Citation2000, 84). Note that what Nussbaum labels internal capabilities are not always considered capabilities. In the capability literature, capabilities are real opportunities that you can exercise if, after reflection, you wish to. It is therefore best not to label Nussbaum’s internal capabilities as “capabilities”, since they are rather a person’s internal capacities and abilities which are indispensable for the exercise of a capability (Robeyns Citation2017, 93). We will further elaborate on these concepts in Section 6.

One very attractive feature of the concept of capabilities is that it combines individual characteristics with external features. A capability is a genuine opportunity to do something or be a particular kind of person, and this requires both personal abilities (skills, knowledge, attitudes, etc.) but also the appropriate circumstances (infrastructure, provisions, properly designed institutions, social norms, etc.). A capability analysis thus puts the person in the structures and contexts in which she lives and asks which genuine opportunities the combinations of these internal abilities and external conditions create. As we will show in what follows, paying attention to both the dimensions of agency and structures is what makes the capability approach such an attractive framework for evaluation and policy design, since both are important in determining the real freedoms and the quality of life that humans can enjoy.

Legal Capabilities and Legal Literacy

The term legal capabilities has been used for decades, but originally this usage was unrelated to the capability approach. In the 1970s, authors were already describing the different capacities a person might need in order to access a legal system effectively (Galanter Citation1974; Garth and Cappelletti Citation1978). The term legal capability was derived from the very broad concept of “party capability”, which is the different strategic advantages and disadvantages a person or another party to a legal dispute can have (Galanter Citation1975). Garth and Cappelletti used this concept as a starting point for analysing the advantages of such a party in the context of debates about access to justice. Access to justice is a trending topic for legal scholars and legal practitioners. It refers to the recourses and remedies that are available to citizens to gain protection from the law and obtain redress in legal disputes within the areas of private and tort law (and in rarer cases public law) (e.g. if one has a conflict or dispute with a family member, neighbour, employee, employer, tenant, etc.). Garth and Cappelletti (Citation1978, 190–193) identified (1) financial resources, (2) one’s competence to recognise and pursue a claim or defence and (3) repeated contact with (and therefore more in-depth knowledge of) the legal system as important when it comes to understanding what legal capability exactly entails. From the conceptual standpoint of the capability approach, none of these three items is a capability. The first is a resource; the second is a skill; and the third is an experience that one has, and hence also points to a skill rather than to a real opportunity.

Around the same time as the introduction of the term legal capabilities, the concept of legal literacy gained prominence. In a narrow sense, legal literacy refers to the professional knowledge of legal experts. Using a broader and more common definition, it refers to everyone’s “degree of competence in legal discourse required for meaningful and active life in our increasingly legalistic and litigious culture” (White Citation1983, 144). Legal literacy is a set of skills that are essential in everyday life and are even seen as “required for effective participation in modern society” (Zariski Citation2014, 21). Possessing a high degree of legal literacy could entail, for example, being able to read and understand legal texts or texts about law (for example in newspapers), knowing the (basic) structure of the legal system, having knowledge about where to find support in case of legal conflicts, and being able to communicate appropriately in such a situation.

The complexity of law, which has its own specific language, has evolved into an area where expert knowledge is required in order to understand and access justice (Roznai and Mordechay Citation2015, 356). Legal literacy can be a way to make law accessible for citizens. Roznai and Mordechay point out that in this context, legal literacy can have many different meanings. The outer extremes of the term are formed by a definition that encompasses a complete understanding of the legal discourse and a definition that only requires a person to be able to recognise legal terms (Roznai and Mordechay Citation2015, 359). They propose defining legal literacy as “mastering legal discourse at a level that is necessary for conducting a meaningful and active life in a world saturated with a legal culture” (Roznai and Mordechay Citation2015, 359). This does not necessarily require skills such as being able to draft a legal text, but rather refers to a person’s understanding of the importance of a legal problem and her ability to find legal support in order to empower herself regarding legal matters. Legal literacy is deemed not only to be an important personal skill but is also regarded as a possible foundation of justice and democratic stability, as it might enhance citizens’ compliance with the law (Roznai and Mordechay Citation2015).

From the preceding paragraphs, it becomes clear that the term legal capabilities was not initially linked to the capability approach; moreover, the concept is older than the literature on the capability approach. As the definitions and descriptions show, it is more closely related to the concept of legal literacy. In recent years, however, authors have been trying to make a connection with the capability approach. It is therefore important to examine whether the term legal capabilities is now used as a concept which can be fully placed within the capability approach. Or, instead, is it mainly trying to tap into the increasing popularity of the capability approach but upon closer scrutiny is merely continuing the language and ideas of the original definition and the concept of legal literacy?

Legal Capability in Recent Legal Scholarship

The concept of legal capabilities as directly linked to and embedded in the capability approach was introduced in 2009 when Martin Jones published a short paper for the Public Legal Education Network (abbreviated as “plenet”, which is now called Law for Life). He mentions the earlier use of the term legal capabilities to distinguish his own approach, which is based on Sen’s capability approach. Jones defines legal capabilities as follows (Jones Citation2009, 1): “Legal capability can be defined as the abilities that a person needs to deal effectively with law-related issues. These capabilities fall into three areas: knowledge, skills and attitudes, emphasising that capability needs to go beyond knowledge of the law, to encompass skills like the ability to communicate plus attitudes like confidence and determination.”

Interestingly, Jones derived these areas of capabilities not from legal literature but from research done on financial capability (Jones Citation2009, 2). Participants at several workshops were asked to propose legal capabilities which people from fictive scenarios need in order to resolve their problems. These capabilities seemed to fit the troika of knowledge, skills, and attitudes which were identified in previous research on financial capabilities, but an explanation of how the capability approach actually inspired the idea of legal capabilities is missing. More importantly, there is no detailed description of how legal capabilities fit in or relate to the core concepts used in the capability approach. We find this somewhat unsatisfying. Rather than outlining a solid concept for legal capability, Jones merely entertains an interesting idea. Moreover, the move to formulating a concrete list of legal capabilities proceeds way too fast: without a more rigorous theoretical underpinning, a comprehensive and justified list cannot be made.

The definition Jones gave has been adapted or slightly altered in several studies on legal capabilities. The notion has been further developed by Law for Life in a framework (Collard et al. Citation2011). Again, a reference to Sen’s capability approach is made without showing how it is used or applied. This obviously raises doubts regarding the definition Collard et al. propose: “In this sense, it may be useful to think of ‘legal capability for everyday lives’, which aims to help people deal with ‘ … the problems of everyday life – the problems people face as constituents of a broad civil society'” (Collard et al. Citation2011, 3).

One might wonder whether our critique is only that there is a lack of proper referencing in the literature on legal capability to insights from the capability literature, or whether the problem is much more profound and that we are claiming that the conceptualisation of legal capability is unsound. The distinction between these two critiques is important because the former is a rather minor critique that can very easily be fixed by proper referencing. The latter is a much more serious critique, since the claim amounts to a charge of work lacking sound theoretical underpinning, and fixing it would require a reconceptualisation of the notion of legal capabilities.

Our critique is indeed the stronger one. It is not merely that there is a lack of proper acknowledgement of and referencing to the capability approach; rather, the problem is one of unsound conceptualisation. The legal capabilities which are currently discussed in the legal literature are mainly what Nussbaum would classify as internal capabilities: skills, knowledge, powers, abilities. Those are the capabilities that are internal to a person and which are developed during one’s lifetime (Nussbaum Citation2000, 84-85). But as we explained in Section 1, what counts in the capability approach are what Nussbaum calls combined capabilities – the combination of internal abilities with the relevant external factors, leading to genuine opportunities. Hence, the literature on legal capabilities adopts only one part of the capability approach and neglects other crucial aspects (the external factors leading to combined capabilities, as well as the distinction between functionings and capabilities). This leaves questions not only unaddressed – such as why people who are able to do something (in the legal context) choose not to so – but even prevents them from being asked.

This critique becomes visible in most of the literature we reviewed. Because a reflection on the capability approach is missing, the lists of legal capabilities often seem rather like a continuation of what was known earlier as legal literacy. An example can be found in the study that was initiated in 2016 by the Community Legal Education Ontario (CLEO) (Brousalis Citation2016). To be clear, we agree that legal literacy is an important concept which can deliver valuable input for the general concept of legal capabilities and, more specifically, for elements of lists of possible specific legal capabilities. However, with the current usage of legal capabilities being largely synonymous with legal literacy, the concept lacks the comprehensive character that is a hallmark of capability analyses. The following critical question therefore arises: does labelling measures of legal literacy as legal capabilities lead to a valuable addition to the capability approach, or is it, instead, merely the use of terminology which may be attracting additional interest?

In sum, the problem we have identified is that legal scholars have introduced the term legal capability, claiming it is based on the capability approach, but they do not explain how this would be the case. The problem is significant, since these studies have more recently been used as the basis for further research by others. The idea of legal capabilities as proposed by Jones and Law for Life has been employed by several studies such as the LAW survey, which assesses legal needs in Australia (Coumarelos et al. Citation2012). In that study, a reference to both Sen and Nussbaum is made, but the term capability approach is not mentioned. Instead, the authors refer to the concept of legal capabilities as introduced by Jones to then introduce a closely related definition. According to the LAW survey, legal capabilities are “the personal characteristics or competencies necessary for an individual to resolve legal problems effectively” (Coumarelos et al. Citation2012, 29, italics added).

One might object to our critique by saying that some of the empirical studies employing the term legal capabilities do account for external conditions. For example, the LAW survey explores the options of legal advice or legal aid (Coumarelos et al. Citation2012, 32–39). But such a response cannot remove our worries. Even though external constraints might play a role when legal capabilities are used in empirical research, it is important to incorporate the concepts of external conditions and combined capabilities in the underlying theory as well.

The same can be concluded regarding the report that discusses the notion of legal capabilities at most length. In 2014, Pascoe Pleasence, Christine Coumarelos, Suzie Forell, and Hugh McDonald published a report (Pleasence et al. Citation2014) on how legal assistance services could be reshaped. Unfortunately, the term “capability” is still used in the analysis to refer to something other than how the capability approach has coined and developed that term. In this report, legal capability means “competences that one needs to make use of the justice system”. People lacking legal capability are described as follows: “They can fail to identify that their problems have legal aspects, may only seek help from non-legal advisers about the non-legal aspects of their problems, may lack knowledge about legal rights, legal services and pathways for legal resolution, and may lack the necessary literacy and communication skills necessary to achieve legal resolution” (Pleasence et al. Citation2014, 31).

Rather than understanding capabilities as the real opportunities available to people (as the capability approach does), Pleasence and colleagues use the term to refer to the personal characteristics and internal resources that allow people to make use of capabilities. There is one difference between their report and the preceding literature, which is that Pleasence and his co-authors discuss the importance of access to resources, such as financial resources and social capital, and not being time-poor (Pleasence et al. Citation2014, 127). It is unclear, however, whether they see this as elements of capabilities or, which they seem to mention most often, as resources that “increase”, “undermine”, and “reduce” capabilities.

Why are Mistaken Conceptualisations a Problem?

In the previous section, we showed that the existing legal literature that uses the term legal capability does not offer a sound conceptualisation of it and uses the term to refer to something else instead.Footnote1 This analysis raises two questions.Footnote2

The first question is as follows: why would it matter that it is claimed that the term legal capabilities is based on the capability approach, even though this turns out to be incompletely the case? There are at least two reasons why the term legal capabilities should be properly based on the capability approach.

The first reason is that it does not help clear communication between legal scholars and policymakers, or between scholars from different disciplines, if the reference to the capability approach is largely semantic rather than conceptually based. In order to have fruitful communication, one must not use term A to refer to something other than A. Yet this is precisely what has happened with the development of the term legal capabilities in the documents and literature discussed in the previous section. The second reason is that a reference to the capability approach comes with a set of normative expectations. In particular, the capability approach is known to lead to informationally rich analyses that take all relevant considerations into account if we are judging people’s opportunities, freedoms, and quality of life, and also to give profound attention to human diversity. A capability analysis goes beyond the formal sphere of life and beyond merely the material dimensions. This also explains its popularity – it does not reduce the diversity of human beings and delivers an informationally rich and “human-centred” analysis. If policy recommendations are based on a more reductionist use of the capability approach, that application and those policy recommendations will in the first instance gain the support of those endorsing the capability approach. It is likely that the application and policy recommendations will not be as comprehensive as a genuine capability application would be. Policy recommendations might neglect some core aspects of the capability approach, such as all relevant dimensions of human diversity, the influence of all relevant external structures and constraints on the shaping of a person’s capabilities, or the normative role attached to human agency.

The second question our analysis raises is: why pay so much attention to the development of the use of such a term rather than directly undertaking the more constructive task of improving the concept? Of course, ultimately the aim should be for legal scholars and policymakers to use a notion of legal capabilities that is conceptually sound. But we believe that it is necessary to make clear how the use of legal capabilities so far has been conceptually unsound. If that is not shown in a convincing way, it will be hard to encourage the community of legal scholars (particularly those who are currently using the term) to reconceptualise it. Solid research cannot proceed without conceptually sound and clear notions. A misleading use of terms cannot advance scholarship. Hence, how we should understand the notion of legal capabilities needs to be clarified if we want that notion to be consistent with the concepts and theoretical framework of the capability approach.

Reconceptualising Legal Capabilities?

In this section, we want to provide what we consider a conceptually sound and more attractive definition of legal capabilities. We believe that legal capabilities are an important concept for capability scholars and legal scholars alike. Independent of our critique of how legal capabilities are defined in the studies discussed earlier, it has to be acknowledged that the notion of legal capabilities is relatively new in the capabilities literature. By offering a refined conceptualisation, we hope to get more legal scholars interested in applying the capability approach. We think it will help us to reach this goal if there is a strong link to a concept that is already known to legal scholars.

Access to Justice

We propose starting from the concept of access to justice, since that is a key concern of the legal scholars who have felt attracted to the capability approach and have been writing about legal capabilities. It is a concept that played an important role in the very early publications on legal capabilities (and legal literacy) (Garth and Cappelletti Citation1978), even before Sen introduced the capability approach. Still, the concept of access to justice remains important – not only in academic literature but also in policymaking (Genn and Beinart Citation1999; Schmitz Citation2020; McDonald Citation2021). Several authors propose applying the capability approach to enhance access to justice. Maggi Carfield (Citation2005, 356–360) suggests using the capability approach as a framework for legal reform enhancing access to justice for those who are disadvantaged. According to Marco Segatti, the capability approach might also be useful in the context of access to justice in order to avoid “tragic choices” when it comes to prioritising cases or the availability of legal support (Segatti Citation2016, 337, 345). This can help to avoid having a legal system that merely grants formal rights. Instead, access to justice can be measured in terms of capabilities and real opportunities (Segatti Citation2016). We agree with Segatti that the capability approach is a helpful framework that can be used to think about access to justice. Moreover, as we will argue in what follows, the capability approach also provides the theoretical resources to reconceptualise the notion of legal capability, thereby addressing the problems with the current uses of that term that we analysed in the previous sections.

One could argue that access to justice is a field that lacks any concise definition (Macdonald Citation2010, 516). Macdonald (Citation2010, 509) defines it as follows: “an accessible system is said to be one that produces: (1) just results, (2) and fair treatment, (3) at reasonable cost, (4) with reasonable speed; and that (5) is understandable to users, and (6) responsive to needs; that (7) provides certainty and (8) is effective, adequately resourced and well organized”. He frames it as an institutional concept encompassing both the process and the results and including a notion of fair treatment. In line with this definition, we consider that access to justice has two main components. On the one hand, it focusses on access to a legal system, and on the other hand, it entertains the idea of fairness and rightness. In this context, the legal system not only encompasses the classic court system but also every possibility that can be used to solve a legal problem. Often those are options which are positioned outside the traditional court system. Examples are offers of mediation as well as access to legal information.

In order to provide a reconceptualisation of legal capabilities, the core concepts of “capabilities” and “functionings” are essential. Recall that capabilities are the opportunity to do something or be a certain kind of person, while functionings focus on the question of whether these capabilities are exercised and realised. Legal capabilities can therefore be considered as the genuine or real opportunities someone has to get access to justice. These include both the formal and the informal possibilities which can be employed to access a legal system or solve legal problems and that are embedded in a system guaranteeing fairness and rightness. The focus on genuine or real opportunities contrasts with theoretical opportunities – that is, those opportunities that one has “on paper” but which one may or may not have in reality.

We consider this conceptualisation of legal capabilities to have three main advantages. First, it is clearly embedded in the capability approach, with its focus on genuine or real rather than merely theoretical or merely formal opportunities. Moreover, linking legal capabilities to access to justice as an outcome does provide us with a measure for assessing legal capability. Lastly, legal capabilities can also add to the research on access to justice. Scholars and policymakers are very interested in (how to achieve) access to justice. At present, the focus of policymakers is often mainly on the provision of and access to resources, such as the provision of legal aid or the access to legal information. Clearly, it is important to consider these aspects (and therefore they are reflected in our model as external factors).

What people are effectively able or willing to do does not always receive adequate attention, though. The use of the notion of legal capabilities can help to shift the current discussion on access to justice towards legal needs and to choices people make. Access to justice can only be realised if external factors such as legal aid or the legal system are creating the legal opportunities to access justice. A houseowner might, for example, request a permit for an extension to their house. Even if this house owner has the capability to understand the procedure and to fill in the necessary documents, there might be barriers in terms of the accessibility of documents or the accessibility of online systems used to submit the request. The owner might have a good understanding of the local language. However, the language which is used in the documents for the permit might be very legal or technical, hence constituting an insurmountable barrier for the houseowner.

Internal and Combined Capabilities

The influence that such barriers (or external conditions) can have on capabilities is discussed by Martha Nussbaum (Nussbaum Citation1997; Nussbaum Citation2000). In particular, her distinction between basic, internal, and combined capabilities is very helpful for further developing the concept of legal capabilities. Recall that basic capabilities are innate and might have the potential to develop later in life (Nussbaum Citation2000, 84–85). In the case of legal capabilities, basic capabilities can play a role as they are necessary for the development of other more advanced capabilities. An example of an innate capability is the capability of learning a language. Thus, even if a person learns and understands a language, this does not mean that s/he has the ability to speak using legal terminology or to understand it. Capabilities that equip you to access justice will not be merely innate. Instead, they are the basic preconditions for what can constitute legal capabilities. Hence, the analysis of legal capabilities should pay attention to internal capabilities, external conditions, and combined capabilities. Only combined capabilities lead to a person being able to gain access to justice.

below visualises the different elements that together constitute legal capabilities. The first row describes the basic terminology that Nussbaum has used to describe capabilities: if basic capabilities develop into internal capabilities, they can, combined with the relevant external conditions, enable capabilities and hence real opportunities. From these (combined) capabilities choices can be made, which result in the outcomes (the functionings). In the case of legal capabilities, a set of basic preconditions can lead to internal capabilities that are relevant for the legal context (such as legal skills or one’s attitudes towards problems). If the relevant conditions apply – such as a properly designed and well-funded legal system, the availability of legal aid, and not being hampered by societal constraints – this creates legal capabilities for people. If people choose to use these capabilities, the outcome is that they have access to justice.

Note that in , even though the categories illustrating legal capabilities have been kept broad, they must be seen as illustrative and non-exhaustive. In fact, an important task for legal scholarship is to analyse what the relevant basic capabilities, internal capabilities, and external conditions are that create legal capabilities.

Internal capabilities can be seen as certain skills a person possesses, but also as indicating an attitude. Does a person, for example, have reading skills? What is a person’s attitude towards solving problems? Internal capabilities are the main focus of the current literature on legal capabilities (Jones Citation2009; Collard et al. Citation2011; Coumarelos et al. Citation2012). helps us to see why that focus is too limited. Internal capabilities might develop, mature, or change during a person’s lifetime. In order to develop and exercise these skills, the external conditions need to be favourable. A person who is able to read will need something to read in order to really exercise this skill. This is a combined capability. Consequently, combined capabilities are real opportunities which require that we have both the relevant internal capabilities and the external conditions that are required for the opportunity to manifest itself. It is important to consider that not all of them are constraints. They might instead enhance the possibility of exercising legal skills. Of course, external conditions are often not favourable and therefore limit access to justice and hence one’s realisation of legal capabilities. External conditions can be rather obvious obstacles, such as the design and functioning of the legal system, the lack of information on legal procedures, or the availability of legal aid.

Because of the obstacles some external conditions might present, the problems are often ingrained very deeply in the system and in society as a whole. Societal constraints, such as racism or sexism, might constitute impediments which cannot be overcome by an individual. An example of such a constraint is the systematic disadvantage that minorities experience in many legal systems (Sandefur Citation2019). This systemic disadvantage starts long before the engagement in a legal procedure (Monk Citation2019). This became known to a broader public with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. In the United States, Black parents prepare their children for encounters with the police by telling them about the institutional racism of the police and justice system. As a consequence, people develop strategies to navigate these systems and avoid encounters with the police (Malone Gonzalez Citation2019). While obstacles like the lack of information might be overcome by personal commitment (investing time in research) or maybe by help from outside (hiring an expert – if available and affordable), an individual will not be able to simply change the broader societal and systemic structures. Instead, one might avoid coming into contact with this system. In that case, the question arises of whether there is a genuine opportunity to access justice and therefore realise one’s capabilities.

Focussing on combined capabilities prevents us from considering legal entitlements as isolated entities which can be equally distributed to different parties. As a consequence, those entitlements always have to be evaluated in terms of the real opportunities they offer. Well-known examples of legal entitlements are human rights. However, not all aspects of each human right granted by a state to an individual might be justiciable. Second-generation human rights in particular (e.g. food, housing, health care) might be enforceable to different degrees. The use of combined legal capabilities enables us to focus on those aspects which are justiciable.

Legal Capabilities or Legal Functionings?

An important question is whether the focus in the debate about legal capabilities should be on combined capabilities or on functionings, that is, on opportunities or on outcomes.Footnote3 As is the case with the capability approach in general, there may be instances where a focus on functionings rather than capabilities can be justified. One reason for focussing on functionings rather than capabilities can be a lack of a sufficiently high level of agency. Examples are persons with a limited legal capacity, such as those from certain age groups (children) (Watkins Citation2016), and groups that might have a reduced mental capacity (Lewis Citation2011; Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Citation2014). They might have a significantly reduced (or even absent) capacity for making well-informed choices. Their reduced agency can be a reason for choosing functionings over capabilities (Robeyns Citation2017, 108–109)

Another reason to focus on functionings directly is that there are some dimensions regarding which it is highly plausible to assume that, given the opportunity, everyone would choose to opt for the corresponding functioning. Examples are opportunities not to be murdered, raped, kidnapped or harassed. It would be almost absurd if the criminal system waited for people to let it know whether they wanted to realise those opportunities before the government offered them the protection of these functionings. However, for other dimensions, including overall access to justice, we should focus on the capability aspect rather than on the functioning, since there might be reasons why a citizen would prefer not to exercise her freedom. Put differently, we must protect the person’s choice of whether or not (and if so, how) to get engaged in legal matters.

There are several examples that illustrate why a person might choose not to exercise her legal capabilities. A legal conflict which concerns the private sphere, such as family and/or friends, is something many people try to avoid because of the bonds one is likely to have and the future relationships one wants to maintain. It is therefore not unlikely that a legally capable person decides not to exercise their legal capabilities and therefore will not have the corresponding functioning. Another example is a victim of sexual abuse who chooses not to report it to the police or is not willing to get involved in a legal procedure because of the publicity involved or because of the repeated trauma this might cause. These examples show that a person can certainly possess legal capabilities without having the correspondent functionings. We therefore consider the focus on combined capabilities as essential to reflect the freedom which is central to the capability approach.

However, note that focussing on combined capabilities instead of functionings can entail some difficulties. It is relatively easy to establish and measure internal capabilities (as shown in Section 4, this has already been done to a certain extent). It also seems feasible to measure functionings by assessing whether someone reached a certain outcome. Measuring combined capabilities in empirical research often poses more challenges. Analysing a combined capability, as something dependent on both the internal capability and the external factors, is often not straightforward. For example, how to formulate a survey questionnaire that aims to measure combined capabilities is a significant challenge. Here, using functionings instead of combined capabilities can be justified on pragmatic grounds – as long as we also gather information on the choices a person can make.

Specific and General Legal Capabilities

For the analyses of legal capabilities, the distinction between general and more specific capabilities (Robeyns Citation2017, 49) is often relevant. A general legal capability such as understanding legal texts can translate into several specific capabilities such as understanding a rental contract, understanding a judgment, or understanding legislation. Many of these specific capabilities depend on external conditions and the choices a person makes when it comes to exercising his/her capabilities. This becomes clear when looking at the example of the specific capability of adequately communicating with legal representatives such as lawyers and judges or even a broad category of employees of different companies, the municipality, or other state agencies which might handle a legal problem. Whether this translates into the specific capabilities of writing a formal letter, making a complaint, or speaking to a judge in court is a person’s choice. Consequently, the act of choosing also determines whether legal capabilities really lead to access to justice.

Is This New Conceptualisation an Improvement?

In order to give a definite answer to the question of whether the conceptualisation of legal capability that we propose is an improvement, applied and empirical research would be needed that would test it in concrete cases of legal conflict or other legal settings. However, conceptually we can already contrast it with the earlier proposals to show what difference it makes and why we think this is an improved concept of legal capabilities.

Recall that the historic use of legal capability focussed on legal literacy, skills, and attitudes. But this will not always be enough for a person to have genuine opportunities to access justice (hence, whether they have legal capabilities as we have conceptualised them). A person can be perfectly literate and able to read and understand legal texts. Still, this does not transform into a real capability if the documents that are required are not available or accessible, or if she lives in a society in which de facto her legal complaint will not be processed within a reasonable time frame.

Take as an example a couple seeking a divorce. This not only depends on both parties being willing to divorce, being capable of understanding the process, and, if necessary, getting legal support, but also on a system that allows couples to divorce at all. A country like the Philippines, which is the last country (except for the Vatican) where divorce is illegal (this legislation is currently under debate), makes it virtually impossible for large parts of the population to legally separate (Abalos Citation2017). Therefore, we should move away from a narrow focus on internal capabilities and instead broaden the focus towards taking into account external conditions in order to assess the combined capabilities a person has when it comes to solving legal problems and accessing justice.

Conclusion

We have argued in this paper that the existing literature which aims to operationalise the capability approach in the legal field by conceptualising the notion of legal capabilities is conceptually unsound. This literature uses a notion of legal capability and claims that it is based on the capability approach. However, we have found this claim wanting. There is a lack of solid conceptualisation and theoretical underpinning. The use of the term does not include some of the essential characteristics of the capability approach.

The idea of legal capabilities is, however, a promising one, and in this paper, we have tried to refine the concept to make it (a) conceptually sound and (b) more attractive for legal scholars. When advocating better access to justice for all people, the notion of legal capabilities can potentially play an important role. It can shift the focus from broad requirements of legal literacy and competencies to an approach that takes into account all the factors that influence whether people have a genuine opportunity to have access to justice (capability) and also what possible constraints they experience when using that capability and translating it into an outcome in which their legal problems are properly addressed (and hence access to justice is secured). In order to allow that research agenda to move forward on solid conceptual foundations, we have proposed a new conceptualisation of legal capabilities that is consistent with the capability approach. We hope that this will contribute to a further development of insights from the capability approach in legal scholarship.

Acknowledgement

For comments on earlier versions of this paper, the authors are grateful to Maurits Barendrecht, Ineke van den Berg, Nicolas Brando, Janet van de Bunt, Quirine Eijkman, Fergus Green, Marco Segatti, Dawn Watkins, and two reviewers for this journal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ann-Katrin Habbig

Ann-Katrin Habbig is a PhD candidate at Utrecht University and a researcher and lecturer in international law at Inholland University of Applied Sciences in Rotterdam. Her research focusses on mapping and developing legal capabilities to advance the access to justice of community-dwelling older people. Her PhD research is funded is funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Ingrid Robeyns

Ingrid Robeyns holds the Chair in Ethics of Institutions at the Ethics Institute of Utrecht University. She has published widely on the capability approach, including its nature, structure and interpretation, as well as questions related to the selection of dimensions, and its promise and limitations in the literature on social justice. She has also used the capability approach for various applied (normative) questions. In 2017, she published the open access book Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: The Capability Approach Re-examined (Open Book Publishers).

Notes

1 In a recent study undertaken independently from ours, Dawn Watkins (Citation2021) comes to very similar conclusions.

2 We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers of this journal, whose comments prompted us to address these concerns explicitly.

3 We are grateful to a reviewer for raising this question.

References

- Abalos, Jeofrey. 2017. “Divorce and Separation in the Philippines: Trends and Correlates.” Demographic Research 36: 1515–1548. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.50.

- Alkire, Sabina. Mar 01, 2005. “Why the Capability Approach?” Journal of Human Development 6 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1080/146498805200034275.

- Brousalis, Kristina. 2016. Building an understanding of legal capability: An online scan of legal capability research. Ontario: Community Legal Education Ontario (CLEO).

- Carfield, Maggi. 2005. “Enhancing Poor People's Capabilities Through the Rule of Law: Creating an Access to Justice Index.” Washington University Law Quarterly 83 (1): 339–360. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol83/iss1/4.

- Collard, Sharon, Chris Deeming, Lisa Wintersteiger, Martin Jones, and John Seargeant. 2011. Public Legal Education Evaluation Framework: Law for Life.

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2014. General Comment no. 1. Article 12: Equal Recognition Before the Law. United Nations.

- Coumarelos, Christine, Deborah Macourt, Julie People, Hugh M. Mcdonald, Zhigang Wei, Reiny Iriana, and Stephanie Ramsey. 2012. Legal Australia-Wide Survey: Legal Need in Australia. Sydney: Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales.

- Galanter, Marc. Jan 01 1975. “Afterword: Explaining Litigation.” Law & Society Review 9 (2): 347–368. doi:10.2307/3052981.

- Galanter, Marc. Oct 01 1974. “Why the Haves Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change.” Law & Society Review 9: 95–160. doi:10.2307/3053023.

- Garth, Bryant, and Mauro Cappelletti. 1978. “Access to Justice: The Newest Wave in the Worldwide Movement to Make Rights Effective.” Buffalo Law Review 27: 181–292. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1297610102.

- Genn, Hazel. 1999. Paths to Justice: What People do and Think About Going to Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Jones, Martin. 2009. Legal Capability. London: Plenet.

- Lewis, Oliver. 2011. “Advancing Legal Capacity Jurisprudence.” European Human Rights Law Review 6: 700–714. doi:10.3316/agis.20210528047596.

- Macdonald, Roderick A. 2010. “Access to Civil Justice.” In The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research, edited by Cane, Peter and Herbert M. Kritzer, 493–522. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Malone Gonzalez, Shannon. Jun 2019. “Making it Home: An Intersectional Analysis of the Police Talk.” Gender & Society 33 (3): 363–386. doi:10.1177/0891243219828340.

- McDonald, Hugh. 2021. “Assessing Access to Justice: How Much “Legal” do People Need and how Can we Know?” UC Irvine Law Review 11 (3): 693–752. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/ucirvlre11&div=24&id=&page

- Monk, Ellis P. Jul 27, 2019. “The Color of Punishment: African Americans, Skin Tone, and the Criminal Justice System.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (10): 1593–1612. doi:10.1080/01419870.2018.1508736.

- Nussbaum, Martha. 1997. “Capabilities and Human Rights.” Fordham Law Review 66 (2): 273–300. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3391&context=flr.

- Nussbaum, Martha. 2000. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nussbaum, Martha. 2011. “Capabilities, Entitlements, Rights: Supplementation and Critiqu.” Fordham Law Review 66 (2): 23–37. doi:10.1080/19452829.2011.541731.

- Pleasence, Pascoe, Christine Coumarelos, Suzie Forell, and Hugh M. McDonald. 2014. Reshaping Legal Assistance Services: Building on the Evidence Base. Sydney: Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2017. Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: The Capability Approach Re-examined. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. Jul 02, 2016. “Capabilitarianism.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17 (3): 397–414. doi:10.1080/19452829.2016.1145631.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. Mar 01, 2005. “The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey.” Journal of Human Development 6 (1): 93–117. doi:10.1080/146498805200034266.

- Roznai, Yaniv, and Nadiv Mordechay. 2015. “Access to Justice 2.0: Access to Legislation and Beyond.” The Theory and Practice of Legislation 3 (3): 333–369. doi:10.1080/20508840.2015.1136151.

- Sandefur, Rebecca L. Jan 01, 2019. “Access to What?” Daedalus (Cambridge, MA) 148 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1162/daed_a_00534. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48562963.

- Schmitz, Amy J. 2020. “Measuring “Access to Justice” in the Rush to Digitize Measuring “Access to Justice” in the Rush to Digitize Recommended Citation Recommended Citation.” Fordham Law Review 88: 2381–2406. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol88/iss6/11/

- Segatti, Marco. 2016. “A Capabilities Approach to Access to Justice. Unfulfilled Promises, and Promising Strategies in the US and in Europe.” Teoria Politica. Nuova Serie Annali 6: 335–359. https://journals.openedition.org/tp/704.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Commodities and Capabilities. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, Amartya. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Sen, Amartya. Jul 01, 2005. “Human Rights and Capabilities.” Journal of Human Development 6 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1080/14649880500120491.

- Watkins, Dawn. 2021. “Reimagining the Relationship Between Legal Capability and the Capabilities Approach.” International Journal of Public Legal Education 5 (1): 4–36. doi:10.19164/ijple.v5i1.1082.

- Watkins, Dawn. Mar 31, 2016. “Where do I Stand? Assessing Children’s Capabilities Under English Law.” Child and Family Law Quarterly 28 (1): 25–44. https://www.familylaw.co.uk/docs/pdf-files/2016_01_CFLQ_025.pdf.

- White, James Boyd. 1983. “The Invisible Discourse of the Law: Reflections on Legal Literacy and General Education.” University of Colorado Law Review 54 (2): 143–159. https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2113/.

- Zariski, Archie. 2014. Legal Literacy: An Introduction to Legal Studies. OPEL Open Paths to Enriched Learning. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press.