Abstract

Car usage in Ghana is growing at an alarming rate. Logically, a growth in total number of cars must be because either (a) population is increasing or (b) car ownership per capita is rising or both. However, these do not sufficiently explain the increasing car population in Ghana. The article argues that the high demand for mobility in the country is an intrinsic part of the political economic track on which Ghana has been travelling since the mid-1980s. This demand is created by, and is in turn stimulated by, the accumulation of capital through economic liberalisation and imperial town planning laws that separate home from work. The result is manifest in human lives lost, environmental conditions worsened and property damaged. The article recommends alternative ways of improving urban transportation in Ghana.

1. Introduction

THE NUMBER one citizen of Ghana yesterday suffered a worrying traffic jam and was held up in a pool of cars for more than half an hour when he was on his way to the El-Wak Sports Stadium in Accra to address Muslims during the Eidul-Fitr celebration. President Atta Mills stunned a highly depleted crowd when he appeared late in an all white Muslim attire after trekking through the jammed traffic on foot, abandoning the presidential fleet of four BMWs and one four-wheel drive on the street … When President Mills finally arrived, he apologized to the National Chief Imam, Sheikh Osman Nuhu Sharubutu; Council of Muslim Chiefs, former Vice President Aliu Mahama, Ministers of State, Members of the Diplomatic Corps and the sparse crowd, confirming he had been stuck in heavy traffic and had moved out of his car to walk to the venue. (Mahama Citation2009)

The above quotation eloquently shows that traffic congestion in Ghana has reached pandemic proportions and is no respector of persons, positions or events. Workers stay in their office till late to avoid the heavy traffic after work. They set off for work, which starts at around 9 am, slightly after midnight to avoid the traffic jam in the morning. School children have to be woken up at dawn so that their parents could take them to school while leaving for work. Traffic congestion is a real problem in Ghana. However, there are other problems too.

Road accidents and environmental pollution are two of them. Since 1991, over 21,000 people have died from road accidents and some 90,000 more have been injured (National Road Safety Commission Citation2009a). There is an urgent need for analysis of the causes of these problems, their social cost and possible ways to remedy them. That is not to suggest that there have not been any studies of the transport sector in Ghana.

Indeed, many have described the problems showing how serious they are (Turner et al. Citation1995; Kwakye et al. Citation1997; Owusu-Ansah and O'Connor Citation2006); some have pointed out the weaknesses in the institutions responsible for urban transport (Fouracre et al. Citation1994; Abdul-Azeez et al. Citation2009); others have highlighted the environmental impact of transport-related emissions (Kylander et al. Citation2003; Kayoke Citation2004; Faah Citation2008) and many more have alluded to the benefits of an improved transport system (Hine Citation1993; Turner and Kwakye Citation1996; Agarwal et al. Citation1997).

Yet, most of these studies are carried out without any coherent analysis of the power relations that shroud the transport problem – the political economy of urban transportation. Here lies the mandate of this study. It integrates the existing studies on the transport problem in Ghanaian cities within a political economic framework. Its originality lies in the rigorous reinterpretation of the scattered findings on urban transportation in Ghana. The article argues that the high demand for mobility in the country is an intrinsic part of the political economic track on which Ghana has been travelling since the mid-1980s. That demand is created by, and is in turn stimulated by, the accumulation of capital through economic liberalisation and imperial town planning laws that separate home from work. The result is manifest in human lives lost, environmental conditions worsened and property damaged. Therefore, in terms of contribution, the research in this article touches on the social, economic and environmental pillars of urban sustainable development. The rest of the article analyses the causes of the problems, provides a distributional analysis of their effects and suggests possible ways of overcoming these problems.

2. Transportation problems in Ghana – causes

The increase in the number of vehicles in Ghana gives cause for concern. The argument is population growth and increasing standards of living are to blame for the rise in the number of cars in cities (see, e.g. Shen Citation1997).

None of these sufficiently describes the Ghanaian case. The majority of the people are still poor and over 80% of the population lives under $2 a day. The banks give car loans to only those in the formal sectors – under 20% in Ghana (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2009a). Currently, the rate at which vehicles are imported into the country (10.84) is about three times higher than the rate at which the national population is growing (3.8). At a total vehicular population of 932,540 versus a human population of about 23,000,000, the number of vehicles per capita is only 0.04, which suggests that the cars in the country are concentrated in few hands. The majority of the population simply cannot afford to own cars; yet the number of cars in the country is increasing at an alarming rate. It is useful to consider alternative reasons for the growth in the population of cars in Ghana.

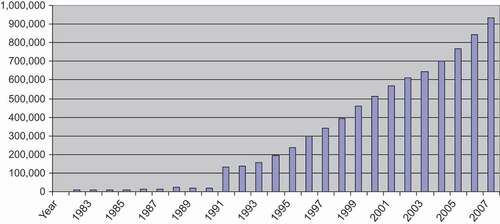

Economic liberalisation is one important reason. According to the president of the Association of Ghana Industries, ‘Ghana's economy [has been] depressingly liberalised’ (see Daabu Citation2009). shows that, prior to 1983, before Ghana started travelling along the neoliberal path, the incremental changes in the number of cars imported into the country was sometimes even negative (e.g. –2184 in 1983). The picture was, however, different after the country was placed on the neoliberal path after 1983. Since the onset of free market ideology, on average, over 35,000 cars are imported into the country every year. So neoliberalism is implicitly responsible for higher material living standards too, at least for the wealthy. But, of course, merely importing cars would not cause traffic jams, unless investments and hence jobs are located in ways in which all traffic in the city must move to the same place. Here too, liberalisation is ‘guilty as charged’.

Figure 1. Total number of cars in Ghana (1982–2007). FootnoteNotes.

Only cities soaked with relatively developed infrastructure like Accra attract private, often multinational, investment. According to the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC), investment in the country continues to grow. Between April and June 2009, there was an increase of 56.6% in the number of registered investment projects in the country compared to the same period in 2008. In monetary terms, this quarter's investment amounted to US$111.67 million, a 91.9 % rise over US$58.19 million, which was the total value for investment projects in the country in 2008 (GIPC Citation2009). These projects ranged from manufacturing to services, agriculture to construction and general trading to tourism. It is important to examine the geographical location of these projects.

All the projects were located in the richest regions in Ghana. In the poorest regions in Ghana – Central, Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions – no investor sited a project. Even within the regions where these projects were sited, Accra alone received over 84% of all the investments (see GIPC Citation2009, p. 2). The failure to regulate the location of capital is an important cause of traffic congestion.

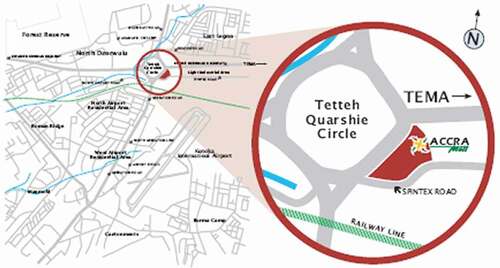

Take, for example, the case of the Accra Mall along the Spintex Road around the Tetteh-Quarshie Roundabout (). This Mall is the first modern retail and leisure shopping centre in Ghana. It was constructed by the award-winning Bentel Associates International of South Africa. Almost overnight, after it started operation, that area has become the epicentre of traffic congestion. There is now endless flow of cars onto Spintex Road and Tetteh Quarshie roundabout (Addae-Bosomprah Citation2009).

Figure 2. Location map of the Accra Mall. FootnoteNotes.

The consistent increase in supply of roads by the state has made a bad situation worse. This diagnosis of the problem may be puzzling to those who feel that more technologically advanced roads like flyovers hold the key to the transport problem in Ghana. A recent editorial in The Chronicle (Citation2009, emphasis added) observed that:

The capital city has become a nuisance for both motorists and passengers due to traffic jams. The situation is even worst around the … Tetteh Quashie Interchange, the Kwame Nkrumah Circle, and many other parts of the city … [but] with the proposed construction of the flyover coupled with the ongoing reconstruction of the motorway extension, Tetteh Quashie-Pantang Junction roads, Accra's traffic problems could be curtailed… . .

Far from this being an outlier, it is a typical response to the traffic congestion problem in Ghanaian cities. Indeed as early as 1975, Tamakloe et al. (Citation1975) were making such proposals to decongest cities in Ghana. As argued by Stilwell (Citation1992), in the Australian case, however, providing more roads only moves the congestion problem around. It is a case of deferring the problem for a different time and/or place. More fundamentally, the construction of more roads may be one of a few cases in which Say's law, supply creates its own demand, works (Stilwell Citation1992). With more roads, there has been the encouragement to private capital to bring in more cars through a liberalised market. Yet, ‘let the roads flow’ appears to be the adopted slogan of the Ghanaian state.

Between 2000 and 2008, a period of only eight years, the total length of surfaced roads in Ghana has increased by over 72%.Footnote1 As of December 2008, Ghana had a total of about 68,000 km road network (World Bank Citation2009). What is more striking is the distribution of the roads among urban, feeder and trunk roads. Indeed, all these could be in urban areas. However it seems that there are some differences though these are not clearly defined. The Department of Urban Roads, for example, defines its ‘functions’, on its official website, as covering all metropolitan and municipal assemblies, which means that the rest of the roads, feeder and trunk, may be in the rural or peri-urban interface. Generally, trunk roads are in the nature of highways while feeder roads, by definition, feed into main roads.

shows that the share of urban and feeder roads have been increasing at an average of 16.52 and 0.3%, respectively. Trunk roads, on the other hand, have been decreasing at an average of 5.79% (i.e. –5.79%). From these figures, it is evident that greater urban road usage is being encouraged. What is not as evident, but not difficult to see nonetheless, is the encouragement of sprawl. As smaller (or feeder) roads are constructed to join the main roads, so are smaller settlements encouraged to join already congested cities. Similarly, by providing more and more feeder roads, the state is, bit by bit, promoting urban sprawl and its associated problems by encouraging the wealthy people in the city to relocate outside the ‘congested’ zones. The increase in mobility through capitalist development therefore has two consequences. It welds rural backwaters into the urban mainstream. At the same time, this mobility tears apart a homogenised urban core (Sawers Citation1978).

Table 1. The share of various types of roads in the total road network in Ghana (2000–2007)

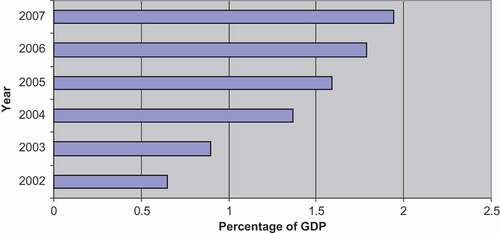

A lot of money – from the Road Fund, the Consolidated Fund and Donor Funds – has been invested in expanding the road network. Between 2002 and 2007 alone, over US$1 billion were sunk into the expansion of roads. More significantly, the share of funds going into road development have been steadily increasing as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) ().

Figure 3. Share of road investment in GDP (2002–2007). FootnoteNotes.

The argument often made by politicians and which infects local chiefs and opinion leaders is that roads that link the country to the city help rural farmers and provide the required mobility for higher prices for farm produce and, hence, enhance poverty reduction. It is even claimed that these new roads may create employment for people in rural areas (see, e.g. Gannon and Liu Citation1997; Faah Citation2008). This latter view may be an exaggeration because other factors such as class, skills and qualifications are more important in seeking employment in Ghana. In any case, for the poor, especially the unskilled poor, they tend to look for work in their immediate neighbourhoods to cut down on transportation cost, knowing well that travelling greater distance for work does not necessarily translate into higher salaries (Fol et al. Citation2007). A recent study in Ghana (Hine and Riverson Citation2001, p. 1) confirms these views. The authors report that:

In a cross-sectional study of 33 villages in The Ashanti Region of Ghana, little evidence was found to suggest that agriculture was adversely affected by inaccessibility, apart from some difficulty in obtaining loan finance in the more remote areas. The more accessible villages were observed to have a higher proportion of people employed outside agriculture. The improvement of existing road surfaces was estimated to have a negligible impact on prices paid to the farmer.

What is needed, the authors argue, is only a modest improvement of a footpath to a motorable vehicle path. Even then, the increase in the benefit to farmers may not necessarily warrant the cost of road construction (Hine and Riverson Citation2001).

Turner and Kwakye (Citation1996) also find that, in the absence of reliable public transport, the poor, especially women and children, do petty trading and door-to-door selling and do not travel outside their communities to look for work. Similar findings about kayayoo or head-load carriers and how they live and work in the CBDs in Ghana have emerged (Agarwal et al. Citation1997).

Roads may help to provide easy access to cities for farmers to sell their produce, even for the infirm to be quickly taken to hospitals, but so would investment in improved urban water provision improve the welfare of the poor. Thus, for the state to withdraw from the provision of water (see Whitfield Citation2006) – perhaps a more important good – and lend considerable support for road construction raises some questions about whether welfare is the only reason for state involvement in road investment or there are other motives.

Unlike roads that are soaked with investment to increase their quantity, rail has only a total of 1300 km and the proportion of the few rail lines in operation in 2000, 90.2%, reduced by more than half to 43.7% in 2003. This figure remained the same for two years (2003–2005) before improving to 44.7% in 2006 and 46% in 2007 – overall growing by an average of slightly above 1% per annum (Ministry of Transportation and Ghana Statistical Service Citation2008).

Public buses fare no better than rail, although official rhetoric is that eventually 80% of all passengers in urban areas will be moved by mass transportation including Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems. Ghana had a public bus system operated by state institutions like the Omnibus Service Authority, City Express Service and State Transportation Corporation. All these made little contribution to urban transport as they focussed on urban–rural and nationwide journeys (Fouracre et al. Citation1994). Most of these services have now been privatised or have simply ceased operation (Finn Citation2008). In 2003, the Metro Mass Transit Limited was established as a joint government (45% share) and private sector (55% share) investment. As of 2007, the fleet strength of the metro mass transport was 779.Footnote2 However, just about 51% of these buses were operational, and the rest were undergoing repairs (Ministry of Transportation and Ghana Statistical Service 2008).

In summary, the state has encouraged people to own cars in three different ways. First, large investments in roads have enticed people to drive. Second, through the liberalisation of the economy, it has become relatively easy to import cars. Third, by consistently under-investing in public transport, bit by bit the state has promoted a strong desire among urbanites to use private cars either as owners or as passengers. It is important to analyse the social cost of increasing number of roads, cars and congestion in Ghana. Road accident and its effects are fairly obvious here. However, pollution and transport-related emissions, which could cause climate change, could also be considered.

3. Social cost of transportation

3.1. Pollution

Increasing vehicular population generally worsens emissions although other factors like fuel characteristics (e.g. contamination and deposits), operation characteristics (e.g. altitude, temperature and humidity) and fleet characteristics (e.g. engine type and fleet mix) are also important. However, in Ghana, an important determinant of emissions is the age profile of vehicles because the age of vehicles provides some indications of which properties (e.g. engine type, the use of catalytic converters or other emission control devices) the vehicles possess (Kylander et al. Citation2003; Kayoke Citation2004).

Only about 8% of the cars imported into Ghana are brand new cars. The remaining 92% could be second-, third-, fourth- or even fifth- hand cars (Linder Citation2006). Some of the vehicles are so old that they have been nicknamed ‘Eurocarcas’ (Yeboah Citation2000, p. 76). These cars, often imported by individuals who have relatives or business partners abroad or shuttle between some developed countries and Ghana, are mostly put to commercial use. In a recent study, the National Road Safety Commission of Ghana found that ‘A significant proportion of the commercial vehicles in the country are old. The age profile is mostly above five (5) years. Only 13 percent are below 5 years, about 34 percent are up to ten (10) years with those up to (15) years and above constituting over 50 percent’ (National Road Safety Commission Citation2009e, Section 3.6).

The quality of the urban environment has been worsened by pollution – noise and environmental – from cars. Vehicular emissions account for 70% of total emissions in Ghana (World Bank Citation2009). As of 2005, the total greenhouse emission from road transport was 4.6 million tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent in Ghana as a whole and will increase by 36% if nothing is done to stem the tide (Faah Citation2008). In per capita terms, the quantity of emissions in Ghana is low – an average of 0.3 tonnes of CO2 per person. In spite of that, the persistent increase of emissions, for example, from 3.8 MtCO2 in 1990 to 7.2 MtCO2 in 2007 (UNDP Citation2007) is worrying.

Cities contribute most of these emissions because of the concentration of cars there (see, e.g. Kylander et al. Citation2003). Arku et al. (Citation2008) have examined the levels and patterns of pollutants in the ambient air in two low-income neighbourhoods in Accra and found that particulate matter (PM), a pollutant made up of components like acids and metals,Footnote3 has increased with the number of vehicles in the city. In the words of the authors, ‘holding other factors constant, proximity to heavy and congested traffic resulted in higher PM2.5 concentration and submicron particle count; this effect was statistically significant for PM2.5 and submicron particle count for congested traffic, and for submicron particle count for heavy traffic’ (Arku et al. Citation2008, p. 228). Another study (Kayoke Citation2004) that examined emission levels of vehicles in the Accra-Tema area in Ghana – focussing on carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides and PM between 1995 and 2003 – found a consistent rise in emissions levels from 3 million tonnes in 1995 through 7 million tonnes in 1999 to 17 million tonnes in 2003 (Kayoke Citation2004, p. 35). Both studies warn that, without changing track, Ghana is headed for disaster.

Atmospheric pollution through vehicle-related emissions like carbon dioxide contributes to greenhouse emissions, to global warming and to adverse conditions of human life through an increase in flood risk and reduced water supply; declining crop production, rising cases of vector-borne diseases, such as malaria and dengue fever; displacement of people who live in coastal cities and islands; and devastating changes in marine ecosystems (UN-Habitat Citation2008, p. 130). These problems in turn have adverse effects on transportation. Infrastructure may be disrupted because of changes in weather patterns, and precipitation affects road safety by increasing congestion and the frequency of accidents (Koetse and Rietveld Citation2009).

Evidently, coastal cities like Accra, Cape Coast, Sekondi and Takoradi stand a greater risk of the rising sea levels than other cities like Kumasi, Koforidua and Tamale, which are in the hinterland. It does not mean these latter cities will be completely insulated from rising sea levels. Indirect costs arising from network effects exist. Some costs like delays and cancellation of journeys to and from the hinterland would be unavoidable. For cities like Cape Coast, which are both coastal and tourist cities, they are likely to have a double ‘tragedy’ because the fear of flooding from rise in sea levels may discourage tourists from visiting tourist centres (Koetse and Rietveld Citation2009). This will have a severe toll on Cape Coast where tourism is the major driver of the urban economy (see Agyei-Mensah Citation2006).

Noise pollution is yet another problem. In Ghanaian cities, the clutter of the block-making machine, banging of the blacksmith's hammer, rumbling in churches and deafening music played by the audio cassette sellers are worsened by the shriek of heavy duty vehicles, the roar of traffic and the screeching of cars. According to the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), noise complaints outnumbered all other complaints it received in 2008. In the Accra Metropolitan Area, EPA notes that about 40% of all complaints were on noise. EPA has also noted that such noise pollution impairs productivity at work as it impedes accuracy, increases the risk of accidents and quickens one's feeling of annoyance and irritation. Outside work, EPA notes that the noise levels in Ghana interrupts sleep, increases blood pressure, heart rate, pulse amplitude, hearing impairment and generally causes psychological problems (GNA Citation2009).

3.2. Accidents

Closely related with increasing old cars in Ghana is the increasing number of accidents.

shows that between 1991 and 2006, there were over 9600 road accidents on average every year and a total of 154,341 road accidents for that period. These accidents commonly result in death, injury and damage to property. As shown in , between 1991 and 2006, the number of road accidents increased by about 40%. During the same period, the number of fatalities from road accidents increased by about 96%.

Table 2. Road accidents in Ghana: injuries, fatalities and damage

The following deductions can be made from and . shows that traffic accidents claim more lives in the ‘economically productive’ population (in our case, 16–65 year group) than those in the ‘economically dependent’ group (0–15 and over 65 years). From 2004 to 2006, the productive age group in ‘all fatalities’ has been consistent at over 74%.

Table 3. Road traffic fatalities by age group (2004–2006)

Table 4. Road traffic fatalities by gender (2000–2007)

shows that over 70% of all fatalities since 2000 are men. The combination of this increase in accidents among people of working age and the high incidence of fatalities among men have adverse effect on the dependency ratio and economic growth in the formal sector of the economy.

From and , we could try to value the human lives lost. Exactly how this can be done is difficult because it is almost impossible to reach a consensus on how much human life is worth in monetary terms. A common practice is to value life using the Human Capital Approach, which states the value of human life in terms of labour earnings. A common criticism of the approach is that it assumes that human life is worthless after retirement. For our analysis here, we will not resort to such unrealistic assumptions.

We could estimate how much of GDP is lost to the country by capitalising the Gross National Income per capita ($600) using the real GDP growth rate (6.3%) and assume, for the sake of this analysis, that those who died through accidents would have worked for a further 20 years before their death. This estimation shows that accidents in Ghana between 1991 and 2006 cost the country over US$ 34 million in current terms or 0.2% of GDP. See .

Table 5. Estimation of human lives lost through accidents in Ghana (1991–2006) using a modified version of the Human Capital Approach

The figure excludes cost in terms of injury, property damage or other administrative costs. A 2006 research by the Building and Road Research Institute (BRRI) of Ghana estimates that road accidents cost Ghana US$165 million – including property damage, human cost, administration cost, loss of output, medical cost – or 1.6% of GDP at the time (see report of the National Road Safety Commission Citation2007). At the time of BRRI's study, the road traffic fatalities per 100,000 population was 8.3%. That figure has increased to about 8.9% in recent times (see report of the National Road Safety Commission Citation2007). That means that the BRRI's figure must be adjusted upwards for the difference in the rate of fatalities (8.92 – 8.33 = 0.59%). If that is done, (1 + 0.59) × 1.6, we arrive at a loss in GDP in the order of 2.54% of current GDP or about $436 million.

Road accidents cost lives and property and have adverse effect on the general economic growth in the country. It is striking that the increasing number of road accidents is happening at the same time as the increasing vehicular population in Ghana (). A correlation analysis of vehicle registration and accident data from 1991 to 2006 shows a strong positive relationship between the two, with a coefficient of determination (R2) value of 0.76 (). To test for possible errors in the computation, a test of significance was carried out. This returned a P-value of 0.00001. This means that the result is statistically significant (i.e. P < 0.05).

Table 6. Summary output of correlation analysis

Some words of caution are needed here. The relationship between the two variables, although strong, is not perfect. More importantly, the correlation does not imply causation. The fact that the two variables, vehicular accidents and vehicular registration, covary does not necessarily mean one causes the other. However, it is intuitive to infer some amount of causal relation in the Ghanaian case, especially when old vehicles are predominant in the country. There are other reasons to believe that increasing importation of old vehicles and the behaviour of the private sector cause road accidents in Ghana.

Ninety-five per cent of the private owners employ drivers without any test or scrutiny of their driving licenses. Also, these entrepreneurs or ‘car owners’ – as they are called in Ghana – set unrealistic end-of-day sales for their employees (the drivers) (ABLIN Consult 2008), which forces drivers to work long hours and speed over the legal limit. According to the National Road Safety Commission, about 60% of the drivers travel at an average speed of 100 km/h for mostly medium to long-distance passenger operations to an average of 50 km/h and work for as long as 12 hours a day, six days a week. Some (20%) could even work as long as 20 hours a day with little rest (National Road Safety Commission Citation2009e). Such pressure evidently leads to road accidents and fatalities.Footnote4

The problems of pollution, congestion and accidents resulting from neoliberal policies are problematic enough at the national level, but such problems also have implications for the global distribution of resources. Selling polluting second-hand cars to Ghana is a way of clearing the skies of New York, Berlin and London while soaking the skies of Accra and Kumasi with toxic chemicals. The rich countries make maximum profit from selling used cars to poor countries. This is not only a sale of machines, it is a pact sealed with human life, the lives of the poor in a developing country. Yet, these car and oil companies who reside in New York, Berlin and London do not miss any opportunity to talk about sustainable development. There is the need for these dynamics to come to a halt.

4. Towards reform

The way orthodox economists propose to solve the problem of transport-related emissions is well documented (see, e.g. Stilwell Citation2008; see also England and Bluestone Citation1971; Fol et al. Citation2007). There should be compulsory antipollution equipment on all cars and a congestion charge or tax for driving at particular places or times, urban toll roads among others. Orthodox economists believe that such measures provide a disincentive for purchasing cars and driving in already congested areas. Such measures have been recommended for Shanghai (Shen Citation1997) and Ghana (see Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences Citation1989) and are already being implemented in cities like London, Singapore, Stockholm, Oslo and Edinburgh (Albalate and Bell Citation2009).

These measures have adverse implications for the poor. A flat rate tax is inherently regressive because it hits the poor the hardest. A congestion charge means greater segregation between the rich and the poor because certain parts of the city can only be visited by the rich, being the ones who can pay the charges. Worse still, a compulsory catalytic device regime will force the poor to pay the same price as the rich for the equipment. Yet, for the poor, it will mean paying more as a share of their income. Such a flat rate becomes less burdensome the wealthier one gets. In the end, inequality and marginality produce further marginality, inequality and poverty (England and Bluestone Citation1971; Fol et al. Citation2007). Some policymakers in the USA have advanced a variant of this latter view, noting that it is socially inequitable to make the poor bear the cost of the pollution of the few rich. The solution, therefore, is not to let the polluter pay because the polluter can pay and the poor need to drive. So rather, the right to pollute should be evenly distributed among different social groups (Fol et al. Citation2007, p. 809).

Such analysis, implicitly assuming that car dependency is natural, is not supported by empirical evidence elsewhere. In Japanese cities, as with Kyoto, bicycles are commonly used as an alternative to cars. About the ‘role of nonmotorised transportation and public transport in Japan's economic success’, Hook (Citation1994) finds that the key role played by public policies discouraged automobile use, encouraged bicycle use and channelled other investment into rail.

The willingness to embrace alternatives to cars depends upon the urban form, social attitudes and public investment in alternative transport technologies and modes. Neither the thinking that car dependence is natural nor the view that the environment must be sold to save it (Stilwell Citation2008) makes sufficient sense. We need alternative measures to curb the problems of transportation in Ghana.

Consideration could be given to banningFootnote5 the importation of cars. Placing high taxes has not dissuaded private individuals from importing these cars, because, on balance, they make huge profit from these less than ideal cars. There is some evidence that a ban would drastically reduce the number of decrepit cars in the country. According to Kayoke (Citation2004), when the government banned second-hand car importation in Ghana between 1998 and 2002 (Kayoke Citation2004), there was a sharp reduction from 15.35% in 1998 to 5% in 2003. Since the government lifted the ban, the rate of registration has shot up to 10.84 (). Merely banning car importation without providing alternatives is not useful.

Alternatives, in the form of greater public transport – buses and trains, nonmotorised forms of transport and land-use change – deserve attention as part of the alternative plan. This three-point agenda should be part of a bigger plan of changing track, of changing an economic system that prioritises profit over human need.

Rail transport is worth considering. It is expensive in terms of physical infrastructure and the cost of land. Nonetheless, the long-term benefits – less congestion, faster travel times, less emissions and a drastic reduction in deaths by road accidents – outweigh the cost. It can be done – indeed it was the dominant form of transport in the Gold Coast, where the rail service was used to help the British to transport cocoa from rural to urban centres. It was a source of inequality as British workers were provided with better conditions of service, culminating in differential work and health conditions between the British workers and the ‘Gold Coasters’ and among the elite Gold Coasters and ordinary labourers (Tsey and Short Citation1995). These are historical observations, and the colonial state was different from the postcolonial state. The former had much more resources and technical expertise at its disposal than the latter. Also, the colonial state was politically insensitive to the people because it was not democratically elected and could decide by state fiat how to use the resources at its disposal. The postcolonial state, especially from 1992 to date, is rather different. It is democratically elected and, in relative terms, sensitive to the needs of the country. Nonetheless, capital behaves the same way yesterday and today.

To make the system serve broader social interests, it is crucial that workers manage or control the management of these rail systems. Recent research by Archon Fung and Erik Wright (Citation2001) shows that ordinary people are able to manage public schools in Chicago, job centres in Wisconsin and public budgets in Porto Alegre. The award of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics to Elinor Ostrom for her work in economic governance – which highlights how ordinary people can successfully manage common property (see The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Citation2009) – should persuade cynics that workers can successfully manage assets. Whether they can manage the railway system in Ghana needs more detailed consideration in the specific context, of course, but these conceptual and empirical contributions from international research suggest that it is at least an open question.

Buses also have potential for reducing congestion, emissions and accidents. About 70% of trips in Ghana depend on buses that use 15% of roads. Compare that with 70% of road usage by the less than 30% of the population that uses private cars and taxis (Global Environmental Facility 2006). Generally, the bigger the buses, the better, as shows.

Table 7. Size of bus vis-à-vis energy use

These gains on their own may still not be encouraging enough for people to use them. Buses must be comfortable. A recent study by Abane (Citation1993) shows that in Ghana comfort and reliability, even more than access, determine which transport mode people use. Here, a BRT, which uses exclusive right-of-way lanes, rapid boarding and alighting, streamlined fare collection and unambiguous route maps, would be particularly useful (see GEF Citation2006). Comfort to people will also mean cleaner environment. GEF (Citation2006) estimates that there could be a 20% further reduction in fuel use if buses operate in less congested lanes. It is estimated that a BRT would cost some US$2–5 million per km in Ghana (GEF Citation2006). This is extremely low compared to the cost of a Do Nothing Approach (see, e.g. for the cost of human life).

Nonmotorised forms of transport could also be promoted. Bicycles are particularly useful as they are ecologically friendly, cheap to use and use less space. Recently, a team from the Earth Institute has begun research into using bamboo to produce Ghana-made bicycles. The pilot project in Kumasi has already been well received by the residents. Using local materials to build the bicycles will make the cost lower, enhance local expertise and create jobs (Sauvant et al. Citation2008). A word of caution is, however, needed. Bamboo is abundant in Ghana and it is a renewable resource. However using bamboos for bicycles also has implications for fauna and flora. There is the need for aggressive bamboo planting at the community, city and national level if this project is to be undertaken on a large scale. Whatever it is, bicycle use in Ghana must be encouraged by prioritising bicycle lanes in the city, providing parking space for them and reducing taxes on their import. These would encourage people to bike to terminals, leave their bicycles parked and board trains/buses to continue their journeys in a ‘park and ride’ system (Kayoke Citation2004).

As with bicycles, walking can be encouraged. Walking has therapeutic effect on the entire human body and if done in a conducive atmosphere – in this case streets designed for it – it could be healing, would make people save money and help the environment to save itself. Evidence has already started emerging (see Abane Citation1993) that people in Ghanaian cities will walk – as they always have! – if given the conducive environment. Concerns about pedestrian safety are genuine. Yet, as we have seen, many of these deaths result from old cars and overworked drivers who are squeezed by their car owners. Banning these second-hand cars and placing fewer cars on the roads would evidently reduce road accidents.

It is also important to change the land-use patterns to better integrate housing and work. This harmonisation, however, is unlikely to happen if private capital is allowed to dictate where it wants to locate. In the housing sector that has been liberalised, rows and rows of estates have been developed in areas without basic facilities like police stations (Obeng-Odoom Citation2009b), contributing to a rise in crime and thus creating fertile grounds for the rise of private security companies in many big cities like Accra and Kumasi. If the central and urban governments are committed to change, the continuous accumulation of capital in only a few cities – and a few areas in those cities – should be rechannelled into alternative spatial forms with more propitious environmental and social effects. Two ancillary policies would further strengthen the potency of this recommendation. Work hours should be negotiated and regulated in the process of granting planning permission and providing business licenses (see also Shen Citation1997). Flexible work hours could help to break the current ‘rush or peak hour syndrome’. It should also be compulsory for all companies to have huge company buses that could be used by the workers to and from work.

There is formidable evidence to suggest that these measures will improve the quality of the environment, increase economic growth, reduce car accidents and reduce the levels of inequality in the country. Empirical studies by Kayoke (Citation2004) shows that greater use of metro buses would reduce emissions by about 50% and a further 50%, if nonmotorised forms of transport are used. In economic terms, such reductions could add about US$20 million to the GDP (Faah Citation2008). To put the figure in perspective, it is about 22% of the total FDI component of the investment projects registered in Ghana by GIPC between 1 April and 30 June, 2009. Also, accident prediction models built by scholars at the BRRI in Kumasi show that with decreases in flow, improvement in the quality of roads and the provision of street lights, road accidents would reduce (see, e.g. Salifu Citation2004).

These proposals are a part of a bigger agenda to change or substantially modify the underlying economic system of production that is currently typified by liberalisation and privatised production. The production and consumption of virtually all goods and services by private individuals and legal persons entail decreasing the welfare of all others in society. Therefore, maintaining private control of resources is ‘inefficient’ in an economic sense and inequitable in a social sense. Because all are affected by every single person's production and consumption decisions, it is only sensible that all must be able to take part in deciding what is produced, how much is produced, for whom it is produced and how it is distributed (see England and Bluestone Citation1971, p. 52). Local governance is important here. What has to be determined is the capacity of the local state to implement such policies.

5. Conclusion

Logically, a growth in total number of cars must be because either (a) population is increasing or (b) car ownership per capita is rising or both. However, these are not sufficient explanations for the increasing car population in Ghana. The rapid rate of car growth is a function of government liberalisation policies and road construction. The former has made the importation of cars relatively easy, whereas the latter has enticed people to buy cars. Both have been fuelled by a poor public transportation system. Both have caused traffic congestion, which has been worsened by neoliberal planning that permits new investment to be sited according to market and neomarket policies.

Only the rich can afford cars in Ghana. They buy brand new cars for themselves and import second-, third-, fourth- or even fifth-hand cars for commercial use. Drivers of these commercial vehicles are overworked and overstretched – they have to make unrealistic returns for their greedy taskmasters. The results are catastrophic, adversely affecting the environment, callously claiming human life, unjustly tearing society apart and ultimately slowing down the wheels of economic growth, redistribution and poverty reduction. There is cacophonous noise that causes several health-related problems; lead, carbon dioxide and PM emissions soak the urban environment and greenhouse gas emissions dangerously hang in the urban environment as a result of neoliberal transport policies. Year by year, several people lose their lives through car accidents. Year by year, massive amounts of property are lost. Year by year, many people are injured and year by year, the country misses gains it could have made towards economic growth and development. These severe costs are unevenly distributed. Invariably, they hit the poor the hardest. There is the need to change track.

Here, pollution taxes would be as ineffective as taxes on importing second-hand cars. Such policies are inherently unequal. They create segregation and social discord. They literally result in a situation where the rich and mighty can buy their way to places where the poor do not have the resources to go. They force the poor to pay more of their income to access basic goods. Urban road tolls have similar impacts. All such policies would result in selling the environment.

More progressive policies are broad ranging and could cover the issues of harmonising job and residential location and making greater use of public transport and nonmotorised forms of transport like biking and walking. Evidently, such policies mean the banning (not taxation) of all used cars and the immediate rethinking of the idea that more roads create less congestion.

Some would even suggest that these policies should be part of a bigger agenda of gradually replacing the economic system that privatises profit above human need with a more humane economic system. Although this view could be taken for the current situation where there are both positive and negative externalities, there are costs (e.g. time) in this alternative too, as in resolving resource allocation questions through public discussion and political processes rather than through the individualised processes of the market. Also, the capacity of the state to play the role of production and distribution becomes crucial. Evidently, there are no easy answers. There is, however, the need to balance, in Gramsci's words, the ‘pessimism of the intellect’ with the ‘optimism of the will.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Prof. F.J.B Stilwell, Priscilla Lee, Kim Neverson and the anonymous reviewers of IJUSD for very helpful comments and suggestions on initial drafts of this paper. Any disparity between their intentions and realisation in this article is solely his.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Franklin Obeng-Odoom

Franklin Obeng-Odoom is a Teaching Fellow and Ph.D candidate at the Department of Political Economy, the University of Sydney. His research interest is in economic development, focussing on the political economy of urbanisation and debates in economic development. His research has appeared in journals such as Regional Studies, Cities, Housing Studies, Development and Habitat International. He is on the editorial boards of Journal of Sustainable Development and African Review of Economics and Finance. He co-ordinates discussions on the online academic forum, Urban Dev (http://urbandev.ning.com/).

Notes

Source: Adapted from National Road Safety Commission (Citation2009b) and Yeboah (Citation2000).

Source: www.ViewGhana.com, Citation2009.

Source: Adapted from Ministry of Transportation (MOT) and Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2008) and Centre for Policy Analysis (CEPA) (Citation2009).Note: The current official name of MOT is ‘Ministry of Roads and Highways’. However, on many of its official reports, it is referred to simply as ‘Ministry of Transportation’. Therefore, the two names are taken as synonyms here.

1. Author's calculations based on various statistics from the Ministry of Roads and Highways.

2. The total number of buses in 2009, as stated on the company's official website, is 838. There is no record of how many of the buses are operational or are grounded; see MMT, 2009.

3. For this definition of particulate matter and other related insights, see US EPA, 2009, ‘Particulate Matter’, http://www.epa.gov/oar/particlepollution/ (accessed 15 September 2009).

4. The definition for ‘fatalities’ used by the National Road Safety Commission is ‘number of deaths resulting from road traffic crashes, with the deaths being those occurring within 30 days after the crash’

5. With the advent of ‘greening’ cars, in future, a policy of banning all second-hand cars could be replaced with a policy of importing only ‘green’ second-hand cars. Unfortunately, even this latter policy would not curb the problem of rapid growth in the rate of car importation.

References

- Abane, A., 1993. Mode choice for the journey to work among formal sector employees in Accra, Ghana, Journal of transport geography 1993 4 (1993), pp. 219–229.

- Abdul-Azeez, A., et al., 2009. Appraisal of the impact of team management on business performance: study of metro mass transit limited, Ghana, African journal of business management 3 (9) (2009), pp. 390–395.

- ABLIN Consult, 2008. A study on the conditions of service of commercial vehicle drivers and impact on road safety conditions. ABLIN Consult..

- http://news.myjoyonline.com/features/200909/34672.asp Last accessed 29Sep2009. , Addae-Bosomprah, E., 2009. Accra shopping mall – right solution: wrong location. myjoyonline.com..

- Agarwal, S., et al., 1997. Bearing the weight: the Kayayoo, Ghana's working girl child, International social work 40 (1997), pp. 245–263.

- Agyei-Mensah, S., 2006. Marketing its colonial heritage: a new lease of life for Cape Coast, Ghana?, International journal of urban and regional research 30 (3) (2006), pp. 705–716.

- Albalate, D., and Bell, G., 2009. What local policy makers should know about urban road charging: lessons from worldwide experience, Public administration review (2009), pp. 962–975.

- Arku, R., et al., 2008. Characterizing air pollution in two low-income neighbourhoods in Accra, Ghana, Science of the total environment 402 (2008), pp. 217–231.

- Centre for Policy Analysis (CEPA), , 2009. The current state of the macro economy of Ghana (2000–2009). Accra: CEPA Research Document; 2009.

- http://news.myjoyonline.com/business/200907/3320.asp Last accessed 30Sep2009. , Daabu, M., 2009. Ghana's economy depressingly liberalised – Oteng-Gyasi. myjoyonline.com..

- England, R., and Bluestone, B., 1971. Ecology and class conflict, Review of radical political economics 3 (1971), pp. 31–55.

- Faah, G., 2008. Road transportation impact on Ghana's future energy and environment. Thesis (PhD). Submitted to the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg; 2008.

- Finn, B., 2008. Market role and regulation of extensive urban minibus services as large bus service capacity is restored – case studies from Ghana, Georgia and Kazakhstan, Research in transport economics 22 (2008), pp. 118–125.

- Fol, S., Dupuy, G., and Coutard, O., 2007. Transport policy and the car divide in the UK, US and France: beyond the environmental debate, International journal of urban and regional research 3 (4) (2007), pp. 802–818.

- Fouracre, P., et al., 1994. Public transport in Ghanaian cities — a case of union power, Transport reviews 14 (1) (1994), pp. 45–61.

- Fung, A., and Wright, E., 2001. Deepening democracy: innovations in empowered participatory governance, Politics and society 29 (1) (2001), pp. 5–41.

- Gannon, C., and Liu, Z., 1997. Transport and poverty. Discussion paper prepared for the Transport, Water and Urban Development Division (TWU); 1997, World Bank, Paper no. TWU-30.

- Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences, , 1989. The future of our cities. Accra: Commercial Associates Ltd; 1989.

- GIPC, , 2009. Second quarter 2009 investment report (1st April to 30th June 2009), The GIPC quarterly update 5 (2) (2009), pp. 1–5.

- Global Environmental Facility (GEF), , 2006. Ghana urban transport – project executive summary. GEF Council Submission; 2006, Project ID P092509.

- http://ghanabusinessnews.com/2009/16/ghana- epa-records-high-complaints-about-noise-making/ Last accessed 27Sep2009. , GNA, 2009. Ghana EPA records high complaints about noise making, Ghana Business News..

- Hine, L., 1993. Transport and marketing priorities to improve food security in Ghana and the rest of Africa. Giessen: Paper presented at the international symposium of regional food security and rural infrastructure; 1993, 1993.

- Hine, J., and Riverson, J., 2001. The impact of feeder road investment on accessibility and agricultural development in Ghana. Study commissioned by the Ghana Highway Authority as part of the Second Highway Project; 2001.

- Hook, W., 1994. Role of nonmotorized transportation and public transport in Japan's economic successes. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board; 1994.

- Kayoke, E., 2004. Pollutant emissions measured: rising transport pollution in the Accra – Tema metropolitan area, Ghana. Thesis (MSc). Sweden: Lund University; 2004.

- Koetse, M., and Rietveld, P., 2009. The impact of climate change and weather on transport: an overview of empirical findings, Transportation research, Part D 14 (2009), pp. 205–221.

- Kwakye, E., Fouracre, P., and Ofosu-Dotse, D., 1997. Developing strategies to meet the transport needs of the urban poor in Ghana, World transport policy and practice 3 (1) (1997), pp. 8–14.

- Kylander, M., et al., 2003. Impact of automobile emissions on the levels of platinum and lead in Accra, Ghana, Journal of environmental monitoring 5 (2003), pp. 91–95.

- http://www.accra.diplo.de/Vertretung/accra/de/01/2006_Reden_PressReleases/mercedes_S_Klasse.html Last accessed 26Sep2009. , Linder, P., 2006. Speech by H.E. Peter Linder, German Ambassador to Ghana, delivered on the occasion of the official launch of the Mercedes S-Class in Accra..

- http://dailyguideghana.com/newd/index.php?option = com_content&task = view&id = 5494&Itemid = 243 Last accessed 25Sep2009. , Mahama, A., 2009. Traffic catches mills. Daily Guide, 22 September 2009..

- http://metromass.com/establish_mmt.htm Last accessed 01Oct2009. , MMT, 2009. The establishment of MMT’, MMT official Website..

- Ministry of Transportation and Ghana Statistical Service, , 2008. Statistical and analytical report (2000–2007). MOT and GSS publication under the Transport Sector Programme Support (Transport Indicators Database Project), Phase II (TSPS II); 2008.

- National Road Safety Commission, , 2007. Accra: National Road Safety Commission, 2007 Annual Report (2007).

- National Road Safety Commission, , 2009a. Annual distribution of fatalities by road user. Accra: National Road Safety Commission; 2009a.

- National Road Safety Commission, , 2009b. National Trends in road traffic accidents and casualties. Accra: National Road Safety Commission; 2009b.

- National Road Safety Commission, , 2009c. National road fatalities by age of victims (2004–2006). Accra: National Road Safety Commission; 2009c.

- National Road Safety Commission, , 2009d. National road fatalities by gender. Accra: National Road Safety Commission; 2009d.

- National Road Safety Commission, , 2009e. Conditions of service of commercial vehicle drivers and their impact on road accidents. Accra: National Road Safety Commission; 2009e.

- Obeng-Odoom, F., 2009a. Contesting neoliberal prescriptions: the case of secondary mortgage market in Ghana, Current politics and economics in Africa 2 (3–4) (2009a).

- Obeng-Odoom, F., 2009b. The future of our cities, Cities. The international journal of urban policy and planning 26 (1) (2009b), pp. 49–53.

- Owusu-Ansah, J., and O'Connor, K., 2006. Transportation and physical development around Kumasi, Ghana, World academy of science, engineering and technology 17 (2006), pp. 129–134.

- Salifu, M., 2004. Accident prediction models for unsignalled urban junctions in Accra, Ghana, IATSS research 28 (1) (2004), pp. 68–81.

- Sauvant, K., et al., 2008. Bamboo bicycles in Kumasi, Ghana. MCI and VCC working paper series on investment in the millennium cities; 2008, Paper no. 04/2008.

- Sawers, L., 1978. "The political economy of urban transport". In: Tabb, K., and Sawers, L., eds. Marxism and the metropolis: new perspective in urban political economy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1978.

- Shen, Q., 1997. Urban transportation in Shanghai, China: problems and planning implications, International journal of urban and regional research 21 (4) (1997), pp. 589–606.

- Stilwell, F., 1992. Reshaping Australia; urban problems and policies. Sydney: Pluto Press; 1992.

- Stilwell, F., 2008. Sustaining what?, Overland (2008), pp. 46–50.

- Tamakloe, E., Riverson, J., and Okyere, J., 1975. Traffic planning of Kejetia: the Piccadilly Circus of Kumasi, Ghana, Transportation 4 (1975), pp. 3–18.

- http://news.myjoyonline.com/features/200909/34669.asp Last accessed 30Sep2009. , The Chronicle, 2009. Editorial: flyover for Nkrumah Circle. myjoyonline.com..

- http://kwa.se Last accessed 15Oct2009. , The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 2009. The prize in economic sciences 2009. Information to the public..

- Tsey, K., and Short, S., 1995. From head loading to the iron horse: the unequal health consequences of railway construction and expansion in the Gold Coast, 1898–1929, Social science and medicine 40 (5) (1995), pp. 613–621.

- Turner, J., Grieco, M., and Kwakye, E., 1995. Subverting sustainability? Infrastructural and cultural barriers to cycle use in Accra. Sydney: Presented at the Seventh World Conference on Transport Research; 1995. pp. 16–21, 1995.

- Turner, J., and Kwakye, E., 1996. Transport and survival strategies in a developing economy: evidence from Accra, Ghana, Journal of Transport Geography 4 (3) (1996), pp. 161–168.

- N-Habitat, U, 2008. State of the world's cities 2008/2009. London: Earthscan; 2008.

- UNDP, , 2007. Human development report: fighting climate change. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2007.

- http://www.accramall.com/images/locationmap.jpg Last accessed 10Dec2009. , ViewGhana.com, 2009. Accra shopping mall. View Ghana.com..

- Whitfield, L., 2006. The politics of urban water reform in Ghana, Review of African political economy 33 (109) (2006), pp. 425–448.

- Project appraisal document on a proposed credit in the amount of SDR 150.5 million (US$225.0 million equivalent) to the republic of Ghana for a Transport Sector Project. Patent number Report No. 47324-GH. 2009, Transport Sector.

- Yeboah, I., 2000. Structural adjustment and emerging urban form in Accra, Ghana, Africa today 47 (2000), pp. 61–89.