Abstract

The purpose of this study is to improve understanding about the process aspects of sustainable community planning. After making a distinction between substance and process in planning, the study evaluates the selection of process tools for sustainable community planning, their different roles, and implementation impacts. Further knowledge of process tools is needed because they convey the unique longitudinal context of planning and visioning for sustainable communities. The contribution to practice lies in increasing planners' awareness regarding process tools in sustainability plans and the need to promote these tools. Overall, the implementation of regulation, evaluation, and education process tools in the Florida Demonstration Project was successful. Process aspects received considerable attention throughout the Project's five years. Discretionary implementation and regional planning were two major weaknesses of the Florida case. Civic engagement, public acceptance, and individual learning were noted as crucial forces in planning and implementing longer-range sustainability.

1. Introduction

Perhaps the most influential planning text of the twentieth century, by Ebenezer Howard, has renewed relevance for contemporary ideas of sustainability (Hall and Ward Citation1998). The book appeared in 1898 under the title Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform and was republished with slight revisions in 1902 as Garden Cities of Tomorrow. Under the new title, Howard's physical, environmental, and economic ideas became popular and ‘probably had more influence on new town development and city planning than any other single approach to urban problems’ (Clapp Citation1971, p. 23). A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, the original subtitle, remained a symbolic reminder of Howard's process approach and social vision that received little attention. Indeed, the Garden City contributed three innovative processes to planning literature and practice: pre-planning for a whole new community, unifying landownership to secure public control over planning, and experimenting in progressive municipal and cooperative forms of social enterprise (Osborn Citation1969, pp. 32–33, Hall Citation1983).

The centennial anniversary of the Garden City also marked the emergence of ‘sustainability’, a new paradigm that might reshape the planning profession. Principles of planning for sustainable environment, economy, and equity (the three Es) are incorporated into plans in an effort to improve environmental protection, local economic development, and fair service delivery (Jepson Citation2001). These principles, which reflect Howard's ideas that influenced generations of European and US planners, address what to do to advance sustainability. Specific answers are provided through a host of plan substantive elements and their measured outcomes. Examples of substantive elements are agricultural land preservation, water reuse, parks and greenways, infrastructure construction, infill development, public transit, and affordable housing (Berke and Conroy Citation2000).

The urban and regional planning literature extensively covers the above elements. However, almost like a recurrence of Garden City history, little attention has been paid to the process of moving towards sustainable ‘three Es’. Perhaps because plans often do not stress administrative and procedural aspects, the literature is almost silent on process principles (Berke Citation2002). These principles address how to advance sustainability. Specific answers may be provided through plan process tools – namely, tools for continuous advancement of the planning-implementation process. Examples of process tools are evaluation indicators, citizen committees, urban design demonstration projects, technical assistance programmes, business retention programmes, and tax incentives (Portney Citation2005, Saha and Paterson Citation2008).

Process-oriented planning has been guiding urban and regional development since the 1960s. For planning scholarship and practice, the emerging sustainability paradigm could serve as a ‘common good’ to improve process/procedural approaches, alongside substantive/design approaches (Berke Citation2002). This study suggests a move in this direction by adding knowledge about long-range planning-implementation process and the central role this plays in the sustainability paradigm. The study argues that process lies at the heart of the paradigm because sustainability is conditioned on the community's long-term capacity to continue to reproduce and revitalise itself without sacrificing future resources. Furthermore, sustainability is conditioned on intergenerational responsibility to maintain local standards of living within the limits of natural resources. Hence, achieving an integrated vision of community sustainability requires continuous plan formulation, revision, evaluation, and negotiation (Campbell Citation1996, Berke and Conroy Citation2000).

The general purpose of this study is to improve understanding about the centrality of process aspects in the sustainability paradigm and to advance a process-oriented definition of planning for sustainability. The study thus provides an evaluation of implementation of process tools for sustainable community planning (SCP). The purpose of the evaluation is to increase knowledge regarding process tools in SCP, their different roles, and implementation impacts. Process tools and substantive elements are the basic components of SCP; regulations regarding these components are documented in a mandatory plan for SCP. The plan is formulated and implemented in a defined spatial unit, namely, a community-wide, large-scale municipal unit (more details below).

The contribution of the study to the literature of planning for sustainability begins with the conceptualisation of SCP and process tools and continues with an evaluation of these tools, their different roles, and implementation impacts. Further knowledge about process tools is needed because they convey the unique longitudinal context of planning and visioning for sustainable communities. In contrast, information is already available regarding substantive elements in planning for sustainability. The contribution to planning practice lies in increasing planners' awareness regarding process tools in plans for sustainability and the need to promote these tools.

The study originates in the familiar notion that plans for sustainability tend to be idealistic, superficial, and vague. Lacking clear identity, their strategies and goals may not differ from those of traditional comprehensive plans. More ideas and claims of sustainability continue to appear in plans, but the question of their uniqueness and translation into practice remains open. More research is needed regarding the translation of sustainability concepts into planning practice and how these guide implementation actions and experiences (Campbell Citation1996, Beatley and Manning Citation1998, Berke Citation2002, Conroy Citation2006, Conroy and Beatley Citation2007).

Because demonstration and pilot projects tend to follow experimental and innovative agendas, they provide ideal settings for sustainability studies. These projects can be influential in drawing cutting-edge lessons and encouraging local professional thinking and public/private actions (Forsyth Citation2002, Chifos Citation2007, Conroy and Beatley Citation2007). The study thus presents a case method of five local communities; the sole participants in a State of Florida pilot initiative entitled the Sustainable Communities Demonstration Project. These communities formulated, mandated, and implemented SCP from 1996 to 2001. The project is evaluated through both content and data analysis of secondary sources, two techniques supplemented by a methodological procedure. The secondary sources include state-level legislation, state–local regulatory documents and reports, census statistics, and academic studies.

The next section provides a theoretical discussion of SCP. The section thereafter introduces the Florida Project and the five communities. The three subsequent sections – methods, results and discussion – cover the selection of process tools for the evaluation and the evaluation itself. The final section draws conclusions and policy implications.

2. Sustainable community planning

Four SCP features mentioned above are discussed below: (1) community-wide, large-scale municipal unit, (2) mandatory plan, (3) substantive elements, and (4) process tools. The first two represent the basic working requirements for SCP. They originated in studies that discuss the limitations of sustainable development (SD). SD has influenced numerous urban and regional plans and gained significant momentum in planning literature during the last two decades. The SD concept was introduced in the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development and then embraced by the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit and the 1996 US President's Council on Sustainable Development. It was adopted worldwide across governments, businesses, universities, and environmental and community groups (Mazmanian and Kraft Citation1999). Berke and Conroy (Citation2000) provided a good example of six broad SD principles: harmony with nature, polluters pay, responsible regionalism, liveable built environment, place-based economy, and equity. Another example is the 10 principles of the President's Council on Sustainable Development (Citation1996). However, SD is still criticised as a holistic and abstract idea, unfit to lead policy development and lacking the specifics to be translated into planning practice. Some of the confusion around SD lies in its applications to different geographical scales, from a small-scale housing subdivision or a recreation park to a large-scale community with a variety of residential, commercial, employment, service, and social activities. In the United States, for example, many communities are adopting SD initiatives in an incremental and piecemeal manner because the intergovernmental system is decentralised and local communities are fragmented. However, local parochial actions diminish the role of SD as an overarching long-term framework for comprehensive sustainability initiatives. Such actions often result in small-scale piecemeal initiatives or short-term programmes (Mega Citation1996, Jepson Citation2001, Berke Citation2002, Conroy Citation2006, Conroy and Beatley Citation2007, Saha and Paterson Citation2008).

Although the differences between principles of SD and those of sustainable community are unclear in the literature, the sustainable community concept offers a spatial approach encompassing a whole community with distinct demographic and social characteristics. Hempel (Citation1999), for example, proposed the following six sustainable community principles: ecological integrity, economic vitality, civic democracy, social well-being, high-quality of life, and reciprocal obligation among community members. The community covers a large-scale geographic area where residents have specific environmental and economic concerns. A sustainable community works to preserve ecological and economic resources. The community links its future sustainability to quality of life, political participation, and consumption habits. On the neighbourhood level, design is related to urban liveability; transportation planning is related to environmental protection (Hempel Citation1998, Citation1999, Portney Citation2005).

SCP is grounded in the sustainable community concept. The spatial unit to apply SCP is a community-wide, large-scale municipal unit: a community with distinct demographic and social characteristics and diversified activities, located within the jurisdiction of an autonomous local government. This spatial unit, the first SCP requirement above, appears compatible with SD. SD proposes an overarching framework to guide integrated visionary planning and to encounter urban and suburban sprawl. Sprawl is a spatial phenomenon with economic and social characteristics. The contemporary anti-sprawl reaction serves as a reminder of the anti-urban reaction towards the problems of the industrial city in the late nineteenth century. That city was the underlying spatial–economic–social phenomenon behind Howard's criticism. The Garden City encountered the problems of the industrial city through planning for several community-wide, large-scale new towns in the region. This integrative planning approach was conducive to a unified social action (Howard Citation1965, Berke Citation2002).

The second requirement for SCP is a mandatory plan, a legally binding document. The plan for SCP consists of mandatory rules, written in explicit style implying political commitment for long-term sustainability. Because of confusion around multiple meanings and ‘buzzword’ uses of SD, sustainability plans often suffer from an uncommitted, symbolic/rhetoric style. A clear commitment may be implied through a formal sustainability plan, especially as part of long-term comprehensive/general/strategic local plan. Another example of a serious commitment is a local office for sustainability programmes (Andrews Citation1997, Jepson Citation2005, Saha and Paterson Citation2008).

The mandatory plan includes the two basic components of SCP: substantive elements and process tools. Substantive elements are largely covered in studies demonstrating the extent that sustainability principles guide community-wide plans. Examples of elements are natural/environmental resource, specific land use, economic development activity, public facility, transportation mode, and housing type. These studies often argue that such elements are also typical of local comprehensive plans. They do not find significant differences between planning documents with SD as an organised framework and those without such a framework. Perhaps more interesting are the studies that measure the degree of substantive elements by using specific evaluation indicators. Common indicators are the rates of elements such as water pollution, water use, gas emission, recycled material, solid waste, job growth, unemployment, housing value, homeownership, vacant businesses, hospital beds, and vehicle miles travelled (Kline Citation1995, Haughton Citation1999, Hempel Citation1999, Berke and Conroy Citation2000, Lindsey Citation2003, Jepson Citation2004a, Haywood Citation2005, Saha and Paterson Citation2008). Evaluation indicators that assess the continuous progress of substantive local plan elements towards sustainability provide an important example of process tools in this study. A technical assistance programme to a community, to plan for sustainability, constitutes another example. A common process tool that appears in this study is a housing demonstration project to educate residents about sustainable urban design. If a housing subdivision is plainly residential, however, it should be counted as a substantive element. Although not immediately apparent, it is important to distinguish between process tools and substantive elements in local plans.

Effective process tools of SCP promote long-range planning, monitor its continuous progress, and educate residents and communities to comply with responsible planning. These tools account for present capacities without sacrificing future resources. They anticipate the needs of present and future generations towards communities and environments (Berke and Conroy Citation2000, Jepson Citation2001, Berke Citation2002). This process notion is reflected in the most popular definition of SD: ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (World Commission on Environment and Development Citation1987, p. 43).

Policy implementation literature explains that lack of information about process tools is related to excessive emphasis on the evaluation of outcomes rather than processes. But, for example, a ‘degraded environment’ as an evaluative outcome does not inform the interaction of development interests and weak planning institutions. Perhaps this dynamic process has resulted in that outcome. Policy literature needs more information about implementation processes and, in particular, how they generate specific outcomes (Pressman and Wildavsky Citation1973, Nakamura and Smallwood Citation1980, Ingram Citation1990, deLeon Citation1999, Sabatier Citation1999, Ben-Zadok and Gale Citation2001).

3. Florida sustainable communities’ demonstration project

Florida's population grew by 32.7% during the 1980s, reaching 12.9 million residents in 1990 (University of Florida, Bureau of Economic and Business Research Citation2000, p. 47). The purpose of the decade's most prominent legislation, the 1985 Florida Growth Management Act (GMA), was to restrain population growth, to control residential and commercial developments, and to protect natural resources and agricultural lands. The 1985 Florida GMA was originally entitled the Local Government Comprehensive Planning and Land Development Regulation Act. Its formal reference in this article is Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.3161–3243, Citation1987. Post-1987 legislative changes in title, section numbers, and their content appear in this article under the reference Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245, Citation1999 or Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3247, Citation2009. The original GMA acronym is kept throughout this article. The GMA implementation began with consistency, the policy that mandated state-centralised, top-down compliance among state, regional, and local plans. A relatively weak and not yet clear SD requirement, compact development, was linked to three secondary provisions of the Act: economic development, affordable housing, and natural resource protection (DeGrove Citation1992, pp. 11–22, Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.3161–3243 Citation1987).

Florida's metropolitan areas grew by 23.5% during the 1990s, reaching 16 million residents in 2000. Close to one-half of the population lived in unincorporated areas, mainly outlying suburbs. One-half of the counties had less than 80,000 residents (Editorial Citation2001, University of Florida, Bureau of Economic and Business Research Citation2002, pp. 14–16). Anti-sprawl, compact development, sustainability, and natural resource issues began to capture Florida's growth agenda in the early 1990s. Suburban sprawl and managing the location of growth, rather than managing growth, became the main problem. The policy response was sprawl containment and increased density in urban areas (DeGrove and Turner Citation1998, deHaven-Smith Citation2000).

The Governor's Commission for a Sustainable South Florida described in its Citation1995 report how residential and commercial developments stretch towards environmental and ecological systems and damage air, water, wildlife, and agriculture. This uncontrolled sprawl harmed the quality of life and curbed compact development. In South Florida, the state's most populated region, the problem was in defiance of most SD principles (Governor's Commission for a Sustainable South Florida Citation1995, pp. 13–23). The Commission's recommendations resulted in a state-wide amendment to the GMA, namely, the 1996 Sustainable Communities Demonstration Project, or Chapter 163.3244 of the GMA. It was the only legislation that focussed explicitly on sustainability and encouraged SCP in Florida localities (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245 Citation1999). The implementation of this legislative amendment from 1996 to 2001 constitutes the case for this study. The amendment's preamble portion called on communities participating in the project to adopt six broad principles of sustainability: (1) limited urban sprawl, (2) healthy and clean environment, (3) restoration of ecosystems, (4) protection of wildlife and natural areas, (5) efficient use of land and other resources, and (6) creation of quality communities and jobs. The preamble authorised the Florida Department of Community Affairs (DCA), the state land planning agency, to administer the project, invite applications, and select five communities ‘of different sizes and characteristics’ (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245, Citation1999 (3244) (1) (2)).

The 1996 project began with the DCA and outside agencies reviewing and assigning scores to 28 local applications. These assessments first assured that the community set an urban development boundary (UDB) and was supported by its Regional Planning Council (RPC). Assessments also accounted for the extent to which the locality demonstrated, in a local plan or land development regulations, sound planning track records that met 12 general criteria mentioned in the statute. The 12 criteria included the promotion of (1) infill development and redevelopment; (2) housing for low-income, elderly, or disabled people; (3) effective intergovernmental coordination; (4) economic diversity and growth while encouraging rural character and environmental protection; (5) public urban and rural spaces and recreation opportunities; (6) transportation and land uses that support public transit and pedestrian-friendly modes; (7) urban design to foster community identity, sense of place, and safe neighbourhoods; (8) redevelopment of blighted areas; (9) disaster preparedness programmes, especially in coastal areas; (10) mixed-use development; (11) financial and administrative capabilities to implement the designation; and (12) effective adoption and enforcement of local comprehensive plan (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245, Citation1999 (3244) (3) (b)). All assessments were forwarded to the Sustainable Communities Selection Committee. The committee reviewed applications, heard public comments, assigned scores, and in December 1996, issued a final report recommending 12 applications. The DCA secretary selected five applications in January 1997. The department and each of the five communities established a Sustainable Communities Team, charged to negotiate a written agreement. The secretary and elected commission/council of each community approved each of the five designation agreements that were signed between May and November 1997 (Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation1997, pp. 1–3). The legislation described the designation agreement as a general document including compliance conditions and procedures. It could be effective for up to five years, subject to revoking if the locality neither complied nor showed progress towards sustainability goals. The locality had to submit an annual self-monitoring report, including updates on amendments, to the DCA. The DCA had to submit to the legislature an annual report, including implementation successes and failures of the whole project and recommendations to either modify or repeal it (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245, Citation1999 (3244) (4) (7) (8)).

The DCA annual reports and the designation agreements were the main sources for content and data analysis in the evaluation described below. The DCA annual report opened and concluded with a general qualitative assessment on the project and the five communities. The rest of the report was a compilation of the annual reports and qualitative assessments from each of the five communities. The five agreements, the basic local SCP documents, also served as the main source for the method of this study. Each agreement was a mandatory plan, a state–local partnership contract for formulation and implementation of general/strategic SCP. The document opened with a brief preamble statement including the promotion of demonstration and innovation values, general strategic goals to achieve local long-term sustainability, and the urban boundary's jurisdiction for applying SCP. The rest of the document described the projects, the substantive elements and process tools targeted for local implementation. The size, comprehensive scope, detailed description, and degree of commitment for the implementation of each local project all varied greatly in each agreement (The DCA annual reports appear in the References, under Florida DCA; the five designation agreements appear under the co-authorship of Florida DCA and the individual community (Florida DCA and City of Boca Raton 1997)).

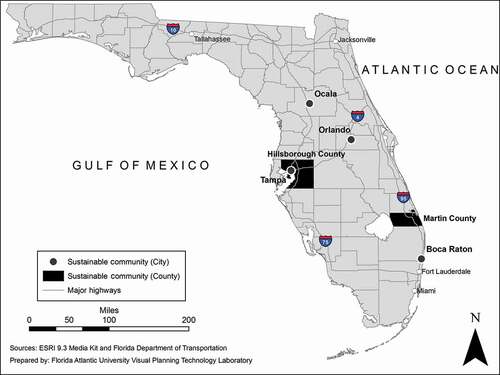

Each of the five designated communities had distinct demographic and social characteristics and constituted an autonomous local government. With respect to the first, Martin County statistics from 1990 to 2000 indicate that it was mid-size by both land area and population relative to the rest of the Florida counties. Sparsely populated with moderate housing prices, this southeast coastal county experienced high growth in the 1990s. Martin's major concerns regarding sustainability were environmental preservation, open space and recreation, disaster preparedness, and affordable housing. Tampa and Hillsborough on the west-central coast received a joint city/county designation to target redevelopment, infill, anti-crime, and sprawl issues. Hillsborough County had a large population, high growth, and housing prices around the state average. Tampa was one of the most populated, dense, and slow-growth communities relative to the rest of Florida's largest cities. Orlando in east-central Florida was also one of the largest cities. Home of Disney World and other huge tourist attractions, Orlando's housing prices were a little above average. Its major concerns were environmental protection in sensitive areas, infill and neighbourhood revitalisation, economic and social programmes, public–private partnerships, and development incentives. Boca Raton on the southeast coast was one of the smaller cities, with high rates of growth, density, and housing price. As a middle- and upper-income community, its concerns were environmental protection, quality of services, and downtown redevelopment. Last, Ocala in the east-central area was a relatively small and slow-growth historic town. As a low middle-income community, it had a broad agenda for improving local conditions (see ; ).

Table 1. Florida sustainable communities by demographic-social characteristics, 1990/2000

4. Methods

4.1. Selection and classification of process tools

All five designated communities met the two basic working requirements for SCP: each represented a community-wide, large-scale municipal unit, and each had a mandatory plan – a strategic SCP document. The plan, the designation agreement, included the two basic SCP components discussed below: substantive elements and process tools.

4.1.1. Selection

SD studies usually select specific items for evaluation, based on content analysis of plans or survey of government officials. After review and content analysis of all possible substantive elements and process tools in the five agreements, elements and tools were selected for this evaluation if they were significant and enforced. The first criterion was the selection of only significant elements and tools and elimination of all other items. Significance of elements and tools was determined by relatively large size, comprehensive scope, and detailed implementation description. The selection ruled out many small, unspecified, and varied items in the agreements. The diversity of items is perhaps related to multiple meanings of sustainability and the lack of focus in translating the concept into planning practice. Other items ruled out during the review were atypical of SCP and mandatory in comprehensive planning sections of the Florida GMA (Hempel Citation1999, Berke and Conroy Citation2000, Jepson Citation2004a, Conroy Citation2006, Saha and Paterson Citation2008). The second criterion was selection of only enforced elements and process tools and elimination of optional ones. After extensive review and content analysis of the agreements, selected elements and tools were those followed by explicit commitment for implementation indicated by key words such as ‘require, must, will, adopt, or implement’. Eliminated items were those followed by less clear commitments, implied by key words such as ‘suggest, encourage, consider, intend, may, would, will address, will determine, will explore, shall define, or shall seek’ (Berke and Conroy Citation2000).

The selection of enforced items only was necessary because of the broad discretionary style of commitments to implement elements and tools in the agreements. Various commitment levels via flexible wording are often related to different levels of political compromises among stakeholders. Ideas of sustainability tend to gather competing interests of businesses, land developers, middle-class residents, and environmental lobbies. In transforming interests into legislation and plans, these groups push compromised bills with flexible language. SCP documents, the signed agreements in the five communities, often represent a mixture of real interests, symbolic rhetoric, and clear and vague commitments (Kraft and Mazmanian Citation1999, Mazmanian and Kraft Citation1999, Jepson Citation2005).

In the shortlist of selected substantive elements and process tools that emerged after employing the two selection criteria, each item was both significant and enforced. Next, elements were dropped from the list; tools were classified and later evaluated for their implementation impacts. The comparison of the two sets that reached the shortlist, elements versus tools, lent external validity from one set to another. Although the five communities exercised great flexibility in adopting numerous items, each set included only those significant and enforced elements/tools that represented important and clear commitments. The comparison of the two sets strengthened the rationale that communities indeed committed only to a limited number of elements/tools that were worthy of evaluative effort. Of the numerous items in the agreements, the small number of significant and enforced elements/tools selected for the list can also be explained by discretionary state–local relationships. This relationship – state's advisory role and minimum supervision over local SCP – will be revisited later. The discretion in implementing the 1996 project was unusual, considering the previous coercive implementation of the GMA. In general, the GMA's consistency policy prescribes integration of plans from top (state) to bottom (local). The state leads implementation via plan review regulations and enforcement of their consistency. Regulations are recorded in Rule 9J-5, a chapter of the Florida Administrative Code, and implemented by the DCA. Although localities formulate local comprehensive plans and monitor their routine enforcement, plans must be consistent with regional and state plans, and only then can be approved by the DCA (Gale Citation1992, Bollens Citation1993, Innes Citation1993).

The following brief summary compares the two sets of findings, substantive elements versus process tools. Data were compiled from the five designation agreements: Florida Department of Community Affairs and City of Boca Raton (Citation1997), Florida Department of Community Affairs and City of Ocala (Citation1997), Florida Department of Community Affairs and City of Orlando (Citation1997), Florida Department of Community Affairs and City of Tampa and Hillsborough County (Citation1997), and Florida Department of Community Affairs and Martin County (Citation1997). Of the many items in the five designation agreements, only 15 elements and 10 tools were counted as significant and also enforced and thus reached the shortlist. Within this total of the final 25 selected items, communities still made their own flexible choices. Specifically, only five tools were not mandated by the state and were appropriated for implementation in the five communities. Only two elements, environmental protection and affordable housing, were implemented in four communities. Finally, eight elements and tools, close to one-third of the total 25, appeared in only one agreement. Among these were agricultural land preservation, water reuse, and visioning plan.

4.1.2. Classification

The 10 selected process tools that made the shortlist were further analysed regarding their contribution to SCP, which is a long-range planning and visioning process including continuous plan formulation, implementation, evaluation, and revision. It also aims to increase understanding of the community's present capacities while not wasting future resources. Beyond that, the literature provides little insight into process tools or how to classify them. All 10 tools appeared to promote long-range planning and vision, some implied a shorter or longer time interval for planning, some paid more attention to the continuous process of improving sustainability. The classification is grounded in the distinct roles of the tools in SCP. Three exploratory roles were identified, each serving a specific function and including three to four tools that made the shortlist. The first role in the classification is regulation, which has a legal function. Second is evaluation, which is crucial for political/policy accountability. Third is education, representing a public teaching/learning function (see ).

Table 2. Florida sustainable communities by process tools for sustainable community planning (SCP): implementation, 1997–2000

Regulation tools are binding laws incorporated into each agreement at the beginning of the SCP process. They constitute the legal base to launch SCP and to begin implementation. In contrast to distributive policies, which are less contentious because they allocate benefit or service a particular group, regulation tools are adversarial because they impose uniform restrictions on all stakeholders (Anderson Citation2000, pp. 9–13). SD literature covers regulation tools, primarily urban growth/service boundaries and similar zoning measures (Jepson Citation2004a, Saha and Paterson Citation2008). With some local flexibility on details, the same regulation tools were mandated in all five communities. Evaluation and education tools, on the other hand, were chosen by each locality and were then appropriated for implementation.

Evaluation tools are used to assess progress towards meeting goals while the implementation of SCP is underway. They are used for periodic monitoring of the ongoing implementation process and for forecasting purposes. They are especially important for intermediate evaluation of a long-range process to improve sustainability. Choices of evaluation tools in communities can be political, depending on competing local interests. However, collaboration among community groups may reduce tensions around these tools (Campbell Citation1996, Wheeler Citation2000, Lindsey Citation2003). SD literature covers evaluation tools, primarily indicators to track progress and citizen/neighbourhood participation groups that intervene and influence the course of implementation (Innes and Booher Citation2000, Jepson Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Portney Citation2005, Evans et al. Citation2006, Soderberg and Kain Citation2006, Saha and Paterson Citation2008).

Education tools also are employed during the implementation of SCP. They aim to increase understanding of sustainability values and to teach techniques to improve community sustainability. They focus on public education via programmes that produce relatively remote and uncertain long-term impacts (Nakamura and Smallwood Citation1980, p. 76). These programmes tend to be less tangible, lacking the immediate and apparent impacts of regulation and evaluation tools. Programmes often promote universal values, such as the protection of environmental and natural resources for future generations. They lack concrete incentives for implementation and hardly mobilise residents and officials. Government and non-profit organisations thus have an important role in educating citizens to appreciate such programmes and values. Academic planning programmes can also help by increasing involvement and curriculum development in this area (Jepson Citation2001, Weitz Citation2001). SD literature covers education tools, primarily local pilot programmes and demonstration projects (Chifos Citation2007, Conroy and Beatley Citation2007).

Regulation, evaluation, and education are three distinct roles that together represent the planning-implementation process in the five Florida communities. With each including three to four tools of SCP, they are covered in this order in the following results and discussion sections. The implementation effort is evaluated through both content and data analysis of secondary sources, primarily the DCA and legislature reports, which cover the project from 1997 to 2000, with several update materials to 2001.

5. Results

5.1. Implementation of process tools

5.1.1. Regulation tools

Three regulation tools were incorporated into each designation agreement at the beginning of the planning process: Urban Development Boundary (UDB), Exemption to Local Comprehensive Plan Amendment (LCPA), and Exemption to Development of Regional Impact (DRI) (-I). These state-mandated tools, all key and legally binding in the 1996 legislation, outlined the jurisdictions targeted for implementation of SCP (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245, Citation1999 (3244) (4) (5)). The UDB, the basic required tool in each community, separated urban and rural land uses. Proposed LCPA and DRI within the UDB and outside the coastal high-hazard area were exempted from state and regional reviews (see below). If the LCPA or DRI was outside the UDB and within the coastal high-hazard area, the reviews were applicable. Each of the five UDBs was identical to either the urban service area line or the city limits. Urban service area in the GMA is a built-up area where public facilities and services such as roads, schools, sewage, and recreation are already in place. Each UDB also included additional specific criteria. For example, in the city of Ocala, the urban service area was marked after the water and sewer service area; in Martin County it outlined the relatively dense coastal zone (-I).

Following the GMA requirement to adopt a local comprehensive plan consistent with regional and state plans, a locality could adopt an amendment to the plan and submit the proposed LCPA for DCA approval. The five agreements exempted the LCPA from DCA review and issuance of objections, recommendations, and comments. Instead, a locality could adopt a proposed LCPA at a single hearing. Affected persons wishing to challenge the amendment's compliance could file a petition for an administrative hearing. The DCA reported that only two amendments, which Ocala citizens challenged, would not pass if they were subjected to state review. The five communities varied in levels of adoption of exempt LCPAs. In 1999–2000, for example, Tampa/Hillsborough and Orlando had multiple exemptions, Martin County and Ocala each enjoyed only two, and Boca Raton was inactive in this area (-I) (Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation2000, Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000).

A DRI in Florida constitutes any development that, because of its location, magnitude, or character, affects the residents of more than one county. The level of exemption from state review for DRI was determined in each agreement. Tampa/Hillsborough was the only community to receive the maximum exemption, enabling review of new DRIs and amendments to existing DRIs. By far the largest community in the Florida Project (), this joint city/county unit had professional staff with extensive technical expertise. In 1999–2000, for example, Tampa (9) and Hillsborough (37) handled 46 reviews. Orlando and Ocala had an exemption for existing DRIs, but they did not conduct any reviews during that time. Martin County and Boca Raton did not review because of state oversight over their DRIs (-I) (Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation2000, Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000).

5.1.2. Evaluation tools

The 1996 legislation paid little attention to systematic evaluation and required only two evaluation reports lacking specific guidelines. Each community submitted an annual self-monitoring report to the DCA and, in turn, the department submitted to the legislature an annual evaluation report of the whole project. Taking a more intense approach, every designation agreement included detailed descriptions of several important evaluation tools. These tools demonstrated the central role of evaluation in the Florida Project and in SCP. Four of the tools are presented in this section: visioning plan, evaluation criteria, evaluation indicators, and citizen feedback (-II).

The visioning plan, the most comprehensive evaluation tool in the project, included long-range goals and strategies for community sustainability (Campbell Citation1996). Their progress and outcomes were monitored via integrated systems linking the other three evaluation tools: criteria, indicators, and citizen feedback. The Martin County Planning Director said that the purpose of the visioning plan was to bring new leadership and citizen participation into planning processes and to build consensus around critical issues in a ‘very politically polarised’ community (Adams Citation1997). Martin County was the only community that chose to create a visioning plan (-II). Throughout the first 18 months of its designation, this county prepared the plan by developing 20 principles to achieve sustainability by the year 2020, 50 evaluation indicators to measure progress, a compatible work plan for local initiatives, and a map of desired locations and types of development. Related citizen feedback activities included a review of alternative future scenarios and consensus on sustainability goals and strategies (Florida Department of Community Affairs and Martin County Citation1997, Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation2000).

Each designation agreement contained a separate section on evaluation criteria and indicators. Evaluation criteria were aimed to assess general progress and success in meeting local goals of sustainability. Evaluation indicators were developed and applied by the locality; goals were continuously measured against specific indicators. This progress assessment was incorporated into the community's annual self-monitoring report. Several agreements noted the limited ability of communities to complete certain projects because of the experimental nature of the Florida Project or shortage of funding.

The agreements listed almost identical criteria for ‘evaluating success of designation’. The following general criteria, all required for the annual report, were employed across-the-board in the five communities (-II): progress and accomplishments made towards achieving general goals of the designation as measured by indicators; progress and accomplishments made towards achieving the goals of specific planning initiatives and projects; adoption and implementation of comprehensive plans and plan amendments in accordance with the GMA; and successful implementation of DRI amendments.

All five agreements required the development of evaluation indicators to measure progress and success in meeting the designation's goals. The indicators represented an assortment of detailed direct measures or broader definitions. Examples were total recycled water used, number of affordable houses provided, number of homes rehabilitated, number of bus stops installed, number of transit riders, expansion of bus routes in city, increase in jobs, net job growth rate, and unemployment rate (for a full list of evaluation indicators, see the five designation agreements, including attachments, mentioned above). The five communities developed evaluation indicators, albeit not all applied them. In the absence of application, Boca Raton and Ocala were marked for little effort. The other three communities developed and applied indicators. Orlando and Martin County demonstrated an extensive effort, Tampa/Hillsborough a moderate one. Hence, there were noticeable differences among the five communities in this area (-II).

The Orlando 1998 report included an extensive analysis of citywide sustainability indicators and their detailed measurements for previous and upcoming years (City of Orlando Citation1998). After Martin County developed 20 principles and 50 respective indicators in the first 18 months of the designation, it started to collect data through direct measurements. Examples of indicators from Martin were the number of acres for agricultural use, street miles for sidewalks/bike lanes, gateways/entrance signs, building permits per neighbourhood, and gated community residents. Marin completed evaluation with a 2000 report covering each principle using several indicators measured per 1999, 2001 (expected) and against the final goal (Martin County Board of County Commissioners Citation2000). The principle ‘conserve and recycle precious community resources’, for example, was measured by indicators such as the ratio between recycled and landfill material.

The DCA contracted with a private consulting firm to make indicator software available to all communities without charge. The purpose was to bridge implementation gaps among communities and to encourage the application of indicators. However, after Tampa and Orlando began to work with the firm in 1999, funding for the INDEX software was slashed and the project was not budgeted for 2000–2001. The Senate report later recommended additional funds to develop evaluation indicators in Florida communities (Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000).

Citizen feedback, the final evaluation tool, was not required in the 1996 legislation. After state–local negotiation, voluntary citizen activities were incorporated into the designation agreements. The activities included review of planning and implementation via citizen committees and surveys. These evaluation efforts aimed to bring citizen input into the SCP process. Each agreement also contained a separate section on public participation, advertising, and hearings. These evaluation inputs to localities applied to persons affected by plan amendments. They are not reported in this article because they are mandated in the GMA. Citizen feedback to SCP covered a broad scope of evaluation activities in communities. It registered an extensive effort in the designation agreements of Martin County, Tampa/Hillsborough, and Orlando but no activity in Boca Raton and Ocala (-II). Martin organised several public participation activities to create its visioning plan, including strategic visioning process, a review of scenarios, and the development of evaluation indicators. Martin initiated a visioning team, an advisory committee to work with a consulting firm on the visioning process, a Hazard Mitigation Strategy Team, which involved residents, and a citizen survey on quality of life. Tampa/Hillsborough also established an advisory committee to develop SD concepts, initiatives, and indicators. Orlando approached public participation as one of six target areas for SCP. The city scored high, particularly on citizen feedback, because of continuous monitoring and reporting of implementation between 1997 and 2000. Orlando aimed to increase citizen participation by tapping local leadership and reaching out to stakeholders who did not participate in traditional comprehensive planning. Neighbourhood training workshops assisted in developing neighbourhood plans and sustainability indicators throughout the year 2000. Orlando even conducted a visual preference study and had a comprehensive website that documented all SCP activities to 2001 (Florida Department of Community Affairs and City of Orlando Citation1997, Florida Department of Community Affairs and City of Tampa and Hillsborough County Citation1997, Florida Department of Community Affairs and Martin County Citation1997, Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation1998, Citation2000).

5.1.3. Education tools

‘Growing Smart’, the American Planning Association project launched in 1994, provides a good example of advancing professional education regarding sustainability. It aimed to assist states in modernising their planning/zoning statutes and disseminating related material to state planning agencies and legislatures. Most states also initiated public and community education programmes to increase awareness around sustainability issues. This is an important issue for Florida because of the centrality of the state's growth issues and a host of extensive and complicated GMA laws. A 2001 survey of planning programmes in the United States indicated that Florida State University and University of Florida are among the three accredited graduate planning programmes offering growth management courses. The architecture school at the University of Miami is home to several ‘smart growth’ and ‘new urbanism’ pioneers, among them the co-authors of one of the first books on the subject. In general, academic planning departments began to enrich programmes and curricula through instruction and reading material about sustainability, particularly in courses on planning statute reform (Duany and Plater-Zyberk Citation1991, Weitz Citation2001).

The Florida Project approached public and community education via three major tools: housing demonstration project, technical assistance, and information dissemination. The DCA encouraged ‘smart’ urban design of housing demonstration projects, including mixed land uses and public transportation. Such efforts varied from low level in Tampa/Hillsborough and Boca Raton to moderate in Martin County and Ocala and high level in Orlando (-III). Martin and Ocala were active in 1997–1998, concentrating on smart urban design and construction of affordable and energy-efficient housing. Martin approved the site and preliminary plan for its urban design project and also began to plan for a $300,000 state-sponsored resource centre including an environmentally sensitive water and sewer system. Orlando was active continuously from 1997 to 2000. The city contracted for a housing project emphasising ‘smart’ urban design. It anticipated funding for the project but could not secure a site. Orlando also organised a demonstration project to reverse neighbourhood deterioration and stabilise multi-family and lower-income housing. (The above summary is based on the five designation agreements mentioned above and the following two reports: Florida Department of Community Affairs (Citation1998) and (Citation2000)).

Delivery of technical assistance to communities was an important aspect of the 1996 legislation. State agencies were supposed to assist and fund programmes in designated communities and to enter project agreements with developers and businesses (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3245, Citation1999 [(3244) (5) (a)] [(3244)(6)]). The DCA was initially uncertain how to move on this legislative goal, but finally began implementation in late 1997. The emerging module was a state–local network based on the delivery of technical assistance to all Florida localities that wished to participate. The network was led by the five designated communities, with each receiving $100,000 as general funding for technical assistance (-II).

Florida Sustainable Communities Network covered about 40 localities, including all 28 designation's applicants, RPCs, and non-profit and private agencies. The network aimed to assist communities in planning for long-term SD beyond conventional comprehensive planning, inform communities on best SCP practices, and create a network for information exchange among all communities engaged in SCP (Peterson Citation2000). The DCA contracted with the architecture school at Florida A&M University to create and maintain the network for three years, with a total budget of one million US dollars. The network conducted a series of state–local technical assistance forums, such as round table discussions, state-wide and regional workshops, and outreach activities for sharing plans and experiences among communities. It also funded the INDEX indicator software, mentioned earlier, an activity free of charge to communities. General funding continued to October 2000 but was not renewed for 2000–2001 (Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation1997, Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation2000).

The network had an information dissemination arm, a website called the Florida Sustainable Communities Centre, which was accessible to Florida public and all local communities. The website included four channels: news, resources, forum, and directory. It served as an interactive electronic forum for communities to present sustainability plans and to disseminate information about new books, articles, and implementation stories. Before the website was closed in 2000, it recorded 9000 users per month. It is noteworthy that Orlando supplemented information dissemination through its own website covering all SCP activities between 1997 and 2001 (-III) (Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000, Peterson Citation2000, City of Orlando Citation2001).

5.1.4. Summary

Of the three roles representing the SCP process in the five communities, evaluation scored the highest implementation effort. With four ‘significant and enforced’ tools, evaluation registered one high, two varied, and one low effort score. With three tools each, education was second registering two high and one varied score; regulation came third. Regarding implementation of individual process tools, the visioning plan and DRI exemption, each was implemented in only one of the five communities and thus scored a low implementation level. Four tools were more popular and had varied performance, i.e. different levels of implementation across the five communities. They were the LCPA exemption, evaluation indicators, citizen feedback, and housing demonstration project. Four other tools received high scores because each was used in all five communities: the UDB, evaluation criteria, technical assistance, and information dissemination (, ‘Combined’ column).

Overall, implementation of process tools for SCP was successful. Note that each of the 10 selected tools was implemented in one or more of the five designated communities; calculating 10 tools × 5 communities gives a total of 50 cases. Of these 50 possible cases, only 11 registered no implementation, which merely reflected the flexible style of making choices in the designation agreements. Specifically, four communities did not commit to a visioning plan, two did not commit to citizen feedback, four did not take advantage of the DRI, and one did not use the LCPA exemption. Of the total 39 implemented cases, little and moderate implementation efforts were registered in only six and three cases. But a total of 30 cases, including the used marks, recorded a high level of implementation impact (, ‘Sustainable Community’ columns).

The final finding on implementation of process tools regards the emergence of two groups of communities, after aggregating the implementation levels and efforts of all 10 tools in each community. The first group, with relatively high implementation impact, especially in the use of evaluation tools, included Martin County, Tampa/Hillsborough, and Orlando. These were larger and relatively diversified communities with more resources and technical expertise. The second group, with relatively moderate implementation impact, included Boca Raton and Ocala. These were smaller and relatively homogeneous communities with less resources and technical expertise (, ‘Sustainable Community’ columns). In the first group, each community scored ‘high’, ‘extensive’, and ‘used’ for the implementation of seven or eight tools. In the second group, each community scored ‘used’ for the implementation of four tools and even less for the rest.

6. Discussion

6.1. Implementation of process tools

6.1.1. Discretion

This section takes the discretionary implementation of process tools as the underlying theme that explains most of the results. After a decade of GMA implementation, Florida legislature and the DCA were facing much pressure from localities and developers to ease the coercive review of consistency among state, regional, and local plans. State and local officials began to de-emphasise certain tools and promote others. The 1996 legislation marked a policy shift towards increased discretion in state–local relations in an effort to facilitate negotiations and feasible political solutions among competing interests. This shift was reflected in many flexible state and local tools in the five DCA community designation agreements (Pellham Citation1992, Deyle and Smith Citation1998, Ben-Zadok and Gale Citation2001). SD ideas suited the new state–local partnership because they are often implemented through negotiated conflicts among local interest and citizen groups. The groups tend to generate multiple meanings of SD to facilitate flexible solutions. This lack of focus in translating SD into planning practice may explain the diversity of items and the different levels of implementation commitments in the designation agreements (Campbell Citation1996, Beatley and Manning Citation1998, Hempel Citation1999, Mazmanian and Kraft Citation1999, Berke and Conroy Citation2000). The many optional items that proliferated in the agreements reflected much flexibility. Most were voluntary, with performance evaluation subjected to the discretion of state–local administrators and planners. Indeed, only ‘enforced’ items with clear implementation commitments were ultimately selected for this study.

The designation agreements show that regular projects were still enforced according to local comprehensive plans, subjected to DCA Rule 9J-5 for minimum criteria. In addition, the broad guidelines in the agreements provided great discretion to localities to develop implementation rules with minimum state supervision. Agreements occasionally referred to best development practices (Ewing Citation1997) as a general guide for a sustainable community. After the book was published by the DCA (and later by the American Planning Association), it was recommended as a guide to Florida officials and developers.

The Florida Senate report concluded that the new state–local labour division worked well and that implementation ran smoothly with minimal conflicts. The two government levels learned to solve problems together and thus improved their relationship. Localities shifted from regulatory compliance to long-term outcome-oriented projects. They did not exploit their discretionary power and acted responsibly, even without rigorous state oversight. The report noted that local discretion and experimentation facilitated compromises among competing stakeholders, provided incentives to communities to initiate SCP processes, and helped to affirm and implement the designation agreements (Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000). But the Florida Project did not answer the question of whether discretionary tools and guidelines improve programme performance. In fact, the senate report criticised the DCA for not applying specific plan components to all communities. Because each community developed its own terms of sustainability, performance evaluation across communities became difficult. The department later provided indicator software for performance evaluation to communities that chose to use it. But in the final analysis, reduction in state oversight and an increase in local discretion were not assessed in relation to corresponding measures of sustainability in communities (Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000).

6.1.2. Regulation tools

The UDB was one tool that did not facilitate local discretion because it separated urban and non-urban land uses. Exemption from review of LCPA and DRI gave communities tremendous discretion. It also saved supervision effort to the state, which, instead, counted on quality local planning. The LCPA and DRI exemptions from state and regional reviews exemplified the great discretionary power granted to localities in the designation agreements. These flexible regulation tools could facilitate compromises between state–local governments and local developers and businesses. The DCA nonetheless noted the lack of interest in exemption from review of new and existing DRIs; the DRI was not tested at all in four communities (Florida Department of Community Affairs Citation2000).

Perhaps regulation tools were utilised less than evaluation/education tools because their implementation demanded significant local resources and technical expertise to perform complex regulatory reviews. However, granting absolute power to communities over DRI reviews was a problematic approach from the beginning. This is because Florida regional planning system was dwindling in the 1990s. The review power of RPCs over consistency of local plans was diminishing because of pressure from developers (Starnes Citation1993, deHaven-Smith Citation1998). DRI exemptions from state and regional reviews could only further cripple the RPCs in their efforts to coordinate anti-sprawl policies among adjacent communities. Although the Florida Project aimed to demonstrate how to control urban and suburban sprawl, it did not address the regional planning issue. It suffered from limited local capacities to conduct regional reviews and showed little interest in DRI exemptions.

6.1.3. Evaluation tools

The Florida Project promoted evaluation as a central and unique function of SCP. Evaluation was emphasised in Martin County, Tampa/Hillsborough, and Orlando. These larger communities were more diversified, had more resources and technical expertise, and used evaluation tools to build consensus among competing groups and to organise support for SCP. In general, this group of larger communities performed better in implementing process tools in the Florida Project. Smaller communities with less resources and technical know-how could not perform well in a project suffering from limited state funding. GMA studies report on limited planning activities in small communities with scarce funding resources (Liou and Dicker Citation1994).

The three larger communities demonstrated extensive effort regarding citizen feedback, including local committees and similar resident activities. But the actual intensity and impact of citizen engagement over SCP decisions is still an open question that must be substantiated (Selman Citation2001). Throughout the 1990s, Florida citizens had little influence over local planning priorities. Planning processes were controlled by the DCA, localities, developers, lobbyists, and paid consultants. In local plan amendment and project approval processes, local officials worked closely with developers; citizens found the discussion and professional jargon difficult to follow (deHaven-Smith Citation1998, Grosso Citation2000). Special needs of socioeconomic and racial groups were also handled with inadequate citizen participation (Turner and Murray Citation2001).

Martin County was most active in evaluation, partly in effort to encourage conflict resolution among citizen groups. It was the only community to develop a visioning plan, whereas all other communities preferred immediate and practical plans. The visioning plan was a broad and comprehensive evaluation tool in comparison to a host of specific technical evaluation elements in other designation agreements. Its goals were subjected to constant monitoring, evaluation, and citizen review.

Evaluation criteria and indicators were two tools to assess whether goals met expected outcomes during implementation. These tools were agreed upon by competing local interests because they both had important economic and political implications. Hence, subjective interpretation and multiple meanings of SD were reflected in the variety of indicators that were developed and applied in the five communities. Whether evaluation covers private consumption habits or public policies, such as economic development, discretionary selection of indicators to measure SD entails some bias because the concept is neither apparent nor agreeable to stakeholders. A limited agreement among stakeholders can be reached by developing indicators for partial constructs based on several principles rather than many principles of sustainability. Still, the mere employment of indicators to measure progress towards goals already implies a serious commitment to sustainability (Hempel Citation1999, Kraft and Mazmanian Citation1999, Lindsey Citation2003, Saha and Paterson Citation2008).

6.1.4. Education tools

Because communities might prefer immediate and practical incentives, they lent only moderate support to education tools. Rather than providing such incentives, these tools promote public acceptance and life-long learning of sustainability ideas. This was the abstract rationale behind two education tools, technical assistance and information dissemination. They were delivered from state to local, a centralised arrangement that required minimal local budgets and was especially favoured by small communities with scarce resources. The DCA then sought to expand this arrangement beyond the winning communities. It promised to work with all programme applicants to improve plans for sustainability and to increase their prospects to enjoy broader legislation in the future (DeGrove Citation2005, p. 72). This resulted in Florida Sustainable Communities Network, a DCA-led state–local arrangement.

Lack of resources forced efficiency in the delivery of education tools. Although the DCA delivered technical assistance and information dissemination tools to all communities, state-level delivery did not include funding for local-level education tools, which remained undeveloped in communities. The senate report concluded that the two state-level tools served the mission of the Florida Project well. The report recommended future programmes to continue low-cost, across-the-board equal delivery to communities. But it also pinpointed the general lack of state funding for these activities as a major weakness of the project (Florida Senate, Committee on Comprehensive Planning Citation2000). On the other hand, the relative popularity of local housing demonstration projects supported the notion of communities as laboratories for innovative designs.

7. Conclusions and policy implications

Ideas of SD have gained popularity in the public discourse and academic literature since the late 1980s. Drawn from a broad reform movement, these ideas generated multiple meanings and political controversies. Liberals criticised the ‘sustainable’ component for a fixed division of duties between present and future systems and lack of inspiration to change the status quo. Environmentalists criticised ‘development’ for damaging natural resources and encouraging consumption and waste. State and local legislatures transformed SD ideas into laws and planning agencies have translated the laws into urban and regional plans. But planning literature criticises SD as an all-encompassing framework that generated multiple interpretations to suit competing local interests. The literature suggests that impact ‘on the ground’ is less evident and SD needs further development into planning practice. The question then remains open regarding the uniqueness and translation of SD ideas into effective legislation and implementation. A partial answer may lie in the sustainable community concept. Focussing on the geographical area and the municipal unit to apply sustainable strategies, this community-wide concept covers the distinct demographic and social characteristics of the local population. It also accounts for environmental, economic, and equity concerns of the residents (Ophuls Citation1996, Andrews Citation1997, Beatley and Manning Citation1998, Hempel Citation1999, Berke and Conroy Citation2000, Lindsey Citation2003, Jepson Citation2005, Portney Citation2005, Conroy Citation2006, Conroy and Beatley Citation2007).

Local plans and demonstration projects promoting SD and sustainable community ideas received increased public and private funding in the United States throughout the 1990s. Businesses and developers also began to realise the high costs of sprawl and expressed sympathy to sustainability plans and projects. Anti-sprawl strategies received much attention and the balance of political forces appeared to tilt in favour of more compact developments. In Florida, the 1996–2001 Sustainable Communities Demonstration Project signalled a small-funded pledge for sustainability. Demonstration projects nonetheless may produce creative lessons; communities can learn through experiences and examples from other locales (Leo et al. Citation1998, Burchell et al. Citation2000, Chifos Citation2007).

The Florida Project made state and local governments more familiar with sustainability strategies and encouraged them to work together on improved planning techniques. The designation agreements should have been more explicit on commitment to substantive elements and process tools, but their sustainability language and terms were not mere symbols (Lindsey Citation2003). The agreements went beyond the ‘sustainable, smart, liveable community’ buzzwords that are often used in professional and layman vocabularies. They were successful in promoting sustainability goals and in giving considerable attention to procedural and process aspects. Indeed, similar DCA–local agreements were executed in Florida's 2002 Local Government Comprehensive Planning Certification Program or Chapter 163.3246 of the GMA. Succeeding the 1996 project, this programme also allowed communities with exemplary planning and compact development practices to operate with reduced state and regional oversight (Florida Statutes, Chapter 163.2511–3247, Citation2009).

The 1997 agreements constituted mandatory plans for sustainability in the five project's communities. The agreements served as the main sources to evaluate the different roles and implementation impacts of process tools for SCP. These SCP documents appeared to encourage communities to consider the limits of their resources and to think about long-range planning. A tri-role series of process tools was implemented successfully along this planning continuum. Especially emphasised was the role of periodic evaluation and related plan revisions. It was followed by public education via programmes to promote and inform about community sustainability. Less emphasised was regulation, legal tools to begin the planning process. Additional roles and process tools should be investigated in an effort to advance the concept of SCP and distinguish it from comprehensive planning.

The discretionary approach of the SCP documents stood in contrast to the previous state–regional–local strict plan consistency of Florida GMA. But this approach was consistent with the literature's criticism regarding ambiguity and professional disagreement around SD ideas. Of the numerous optional items listed in the agreements, many were insignificant, small in size, and were not followed by numerical performance measurements. This practice endowed state–local administrators and planners with much flexibility in implementation. In the annual reports used for this evaluation, they often recorded implementation outcomes in qualitative rather than numerical values.

Discretionary implementation processes may work in some responsible communities with sound planning practices. In most Florida communities, however, discretion tends to facilitate negotiations and short-term trade-offs among developers, local politicians, and the state. The state then should force communities to incorporate explicit rules and detailed incentives into local sustainability programmes. It should also monitor the implementation of these programmes. Future sustainable community designations should be encouraged in communities that enjoy reasonable levels of resources, technical know-how, and funding. Ultimately, implementation of SCP in communities must confront Florida's political reality and willingness to advance this kind of planning. The traditional implementation constraints of the state include strong interest groups and developers, citizens who mistrust local government, localities short on budgets and technical expertise, and short-term agendas limited by legislative terms (Starnes Citation1993, Faludi Citation1999, Evers et al. Citation2000, FAU/FIU Joint Center for Environmental and Urban Problems Citation2000, pp. 64–67; Ben-Zadok and Gale Citation2001).

These constraints also contributed to flexible implementation of regional planning, another major weakness of the Florida Project. Not only was the DRI exemption the only regional process tool in the project, it also allowed communities to conduct their own reviews with minimum state supervision. Because coordination of anti-sprawl policies among communities is crucial for sustainable regional planning, Florida RPCs should be re‐empowered to maintain state standards. Although the UDB was an excellent example of a community-wide anti-sprawl tool with metro-regional implications, it did not apply to other communities in the region. In contrast, Oregon's urban growth boundary is mandated by every city and, thus, it can cut potential utilitarian trade-offs between economic development and environmental protection (Weitz and Moore Citation1998).

Regional government institutions for reconciling differences among communities are critical for effective anti-sprawl and sustainability policies. Like many programmes in the United States, the Florida Project barely touched the problem of competition among local communities and the need for metro-regional coordination. Acknowledging this problem, smart growth agendas promote regional efficiency, environmental protection, and fiscal responsibility in land-use decisions (Porter Citation1998, Burchell et al. Citation2000, Weitz Citation2001). Similarly, sustainable communities should benefit from fair resource allocation and extend preservation efforts beyond their boundaries. They should work together for responsible development–environment policies that account for the needs of all communities in the region, state and even worldwide (World Commission on Environment and Development Citation1987, Mega Citation1996, President's Council on Sustainable Development Citation1996, Vitousek et al. Citation1997, Haughton Citation1999, Wheeler Citation2000, Feiock and Stream Citation2001).

Indeed, linking local–regional–state–global spaces and present–future needs are abstract and costly ideas. Sustainable community initiatives often take place in higher-income communities. Hence, it is important to ensure equity in delivering tools and incentives to all localities in the region and state. This was a central issue in Agenda 21 of the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit (Hempel Citation1999, p. 57, United Nations Environmental Programme Citation2000). Ultimately, the process and progress of sustainable community reforms depend on civic engagement, public acceptance, and individual learning of sustainability ideas through life-long education. The same social and individual forces that were at the heart of Ebenezer Howard's reforms (Hall Citation1983, President's Council on Sustainable Development Citation1996, p. 12, Selman Citation2001, Evans et al. Citation2006, Edge and McAllister Citation2009).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Efraim Ben-Zadok

Effraim Ben-Zadok. School of Public Administration, College of Architecture, Urban and Public Affairs, Florida Atlantic University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA. [email protected]

References

- Adams, S., 1997. Martin county: Florida sustainable communities demonstration project. Tallahassee: Florida Sustainable Communities Center; 1997.

- Anderson, J.E., 2000. Public policymaking. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2000.

- Andrews, R.N., 1997. "National environmental policies: The United States". In: Jaenicke, M., and Weidner, H.J., eds. National environmental policies: a comparative study of capacity building. New York: Springer Verlag; 1997. pp. 25–43.

- Beatley, W.C., and Manning, K., 1998. The ecology of place: planning for environment, economy and community. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1998.

- Ben-Zadok, E., and Gale, D.E., 2001. Innovation and reform, intentional inaction, and tactical breakdown: the implementation record of the Florida concurrency policy, Urban affairs review 36 (6) (2001), pp. 836–871.

- Berke, P.R., 2002. Does sustainable development offer a new direction for planning? Challenges for the twenty-first century, Journal of planning literature 17 (1) (2002), pp. 21–36.

- Berke, P.R., and Conroy, M.M., 2000. Are we planning for sustainable development? An evaluation of 30 comprehensive plans, Journal of the American planning association 66 (1) (2000), pp. 21–33.

- Bollens, S.A., 1993. "Integrating environmental and economic policies at the state level". In: Stein, J.M., ed. Growth management: the planning challenge of the 1990s. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 143–161.

- Burchell, R.W., Listokin, D, and Galley, C.C., 2000. Smart growth: more than a ghost of urban policy past, less than a bold new horizon, Housing policy debate 11 (4) (2000), pp. 821–879.

- Campbell, S., 1996. Green cities, growing cities, just cities? Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development, Journal of the American planning association 62 (1996), pp. 296–312.

- Chifos, C., 2007. The sustainable communities experiment in the United States; insights from three federal-level initiatives, Journal of planning education and research 26 (2007), pp. 435–449.

- City of Orlando, , 1998. Sustainable communities demonstration project: annual progress report. Orlando: City of Orlando; 1998.

- City of Orlando, , 2001. Sustainable communities demonstration project: annual progress report. Orlando: City of Orlando; 2001.

- Clapp, J.A., 1971. New towns and urban policy. New York: Dunellen; 1971.

- Conroy, M.M., 2006. Moving the middle ahead: challenges and opportunities of sustainability in Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio, Journal of planning education and research 26 (2006), pp. 18–27.

- Conroy, M.M., and Beatley, T., 2007. Getting it done: an exploration of US of sustainability efforts in practice, Planning, practice & research 22 (1) (2007), pp. 25–40.

- DeGrove, J.M., 1992. The new frontier for land policy planning and growth management in the states. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy; 1992.

- DeGrove, J.M., 2005. Planning policy and politics: smart growth and the states. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy; 2005.

- DeGrove, J.M., and Turner, R., 1998. "Local government: coping with massive and sustained growth". In: Huckshorn, R.J., ed. Government and politics in Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida; 1998. pp. 169–192.