Abstract

This study examines the effects of urbanisation in three peri-urban communities in Kumasi. Structured interviews, key informant interviews and focus group discussions are used as data collection tools. The study reveals that urbanisation has presented constraints and opportunities to the peri-urban communities. Peri-urbanism has led to agricultural land use giving way to residential land use, with a reduction in population engaged in agriculture. As arable land reduces, agriculture as a source of livelihood has diminished. While agriculture has declined and is in the process of being modified, new livelihood types have evolved. Overall, peri-urbanism has been a blessing, affecting livelihoods positively. The study recommends a speedy implementation of the urban policy which is at the draft stage. Promoting vertical development to protect prime agricultural lands and avert dangers of food insecurity is the way forward. To succeed however, peri-urban dwellers, urban developers and planners, city authorities, traditional rulers and all stake holders must come on-board.

1. Introduction and background

The world is increasingly becoming urbanised, with about half of the world’s population already living in urban areas (Thomas Citation2008; Olujimi Citation2009; Satterthwaite et al. Citation2010). As a result of the different outcomes of urbanisation in different geographical regions, diverse opinions have been expressed about the effects of urban growth on the adjoining rural areas of cities. Modernisation theory has long been strongly linked with urbanisation and the growth of industrial capitalism, principally through spatial diffusion of modernity (Maxwell et al. Citation2000; Potter et al. Citation2008). The emergence of the Growth Pole theory in the 1960s and 1970s saw the activation of cities as growth centres with the notion that growth will trickle down to the adjoining rural areas (Gantsho Citation2008). It is argued that urbanisation provides opportunities that promote growth and development in the adjoining areas through transformation in local economies, leading to greater entrepreneurism. Njoh (Citation2003) shows that urbanisation and development measured in terms of the HDI are positively linked. Research shows that there is a strong positive relationship between urbanisation and economic development in Ghana (Obeng-Odoom Citation2010). The process of urbanisation, it has been noted, holds a great promise for economic and social progress of Ghana (Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development 2010).

Although the potential of these huge increases in urban population has largely been recognised, urbanisation still remains a critical problem particularly in Africa where most of the big cities are characterised by urban sprawl and are faced with the problem of rapidly deteriorating physical and living environment (Olujimi Citation2009; Chirisa Citation2010). Since the second half of the twentieth century, countries, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa have experienced rapid urbanisation. The rate of urban growth in Africa is alarming and the continent is said to have the highest rate of urbanisation globally (Gantsho Citation2008). Concern has been raised about these huge increases in urban population because unlike Europe and other parts of the world, urbanisation in Africa is accompanied with the absence of industrial expansion (Songsore Citation2003; Keiser et al. Citation2004). The populist revision of Modernisation and neo-Marxist theories reverses the view that cities are engines of growth and development, noting that urbanisation in Africa has not necessarily been associated with industrialisation, but is an extractive – even ‘parasitic’ – process that undermines agriculture and rural development (Baker and Pedersen 1992 cited in Maxwell et al. Citation2000). Available statistics show that Ghana has crossed the urban divide, with about 51% of the total population of the country in towns and cities. The rapid pace of urbanisation is taking place within a context where the growth of Ghanaian cities and towns has been anything but planned and controlled (Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development 2010).

Increasing urbanisation and population growth creates scarcity resulting in the high cost of land and other associated problems of multiple allocations and litigations in the city centre. To meet their need for land for residential and non-agricultural purposes, developers look beyond the urban centre for cheaper and problem-free land. Peri-urban interface (PUI) then becomes a hot spot. A key feature of peri-urban environment is their dynamic nature, where social forms and arrangements are created, modified and discarded. Peri-urbanism may lead to a decline in social cohesiveness and increase in social stratification. The strong traditional bonds among the rural folks could be undermined due to demands of work while the influx of wealthier new-comers could heighten social stratification. It is also characterised by conversion of agricultural land to residential and non-agricultural purposes, resulting in rural land prices escalating (Gantsho Citation2008).

PUI is not a homogenous area.It is a fragmented mosaic of dynamically changing resource flows arising as a consequence of urbanisation and offering both opportunities and threats that change over time to people living in this space. The opportunities and threats are not evenly spread either within the PUI space or among the people inhabiting the PUI creating winners and losers. The PUI is considered as a process taking place between rural and urban areas rather than as a geographical location or spatial land use (Brook & Davila Citation2000; Simon et al. Citation2004 cited in Gregory Citation2005). Narain and Nischal (Citation2007) argue that an attempt to define the peri-urban as a process helps to better understand it as the existence of both rural and urban characteristics and the linkages between the rural–urban and the flow of goods and services. For the purpose of this study, peri-urban areas are defined as transition zones of rural fringes surrounding established cities which are characterised by intense flow of people and goods and the co-existence of rural and urban livelihood activities with rural occupations constantly changing in response to urban expansion.

The population of Kumasi has increased at an unprecedented pace. In the inter-censal years (1984–2000), the population of the city grew at the rate of 5.2% per annum. This increased to 5.4% between 2000 and 2010.These growth figures have all been about twice the national growth rate of 2.7% (1984–2000) and 2.4% per annum recorded between the year 2000 and 2010 (Afrane & Amoako Citation2011). While the nation’s rate of population increase is reducing, that of Kumasi is increasing at an uncontrollably high rate and is currently accommodating a third of the population of Ashanti Region (KMA Citation2010). The reasons are not hard to find. Kumasi is both the capital of the Asante State and the Ashanti Region. Its strategic central location (nodal city) as well as its rich forest and other natural resource endowments engineered the city’s role as a transit point and a powerful commercial hub for migrants from both the northern and southern parts of the country and beyond. Historical antecedents of the city have played no mean a role in consolidating the rich cultural heritage of the city (Amoako & Korboe Citation2011). These formed the basis of Kumasi’s growth as a sovereign traditional administrative capital.

The rapid population growth of the city has necessitated a substantial demand for housing within the Metropolis, resulting in an annual housing growth rate of 8.6% between 1984 and 2000 (GSS 2005 cited in Afrane & Amoako Citation2011). The physical structure of the Kumasi Metropolis is thus affected, resulting in the expansion of peri-urban settlement at the city’s fringes. The development of peri-urban Kumasi has revolved around a series of factors which are largely outside the control of the city authorities. This is mostly attributed to the fact that the development of these peri-urban areas does not follow strictly formal and traditional urban planning and development processes (Afrane & Amoako Citation2011). In Kumasi, it is noted that even where there is little or no population pressure, a variety of factors rooted in the desire to realise new lifestyles in peripheral environments, outside the inner city drive the peri-urban growth. This is due to high demand and cost of the built-up areas coupled with the limited space. At the same time, peri-urbanism has accelerated in response to improved transportation links and enhanced personal mobility in the city. The mix of forces include both micro and macro socio-economic trends, such as the means of transportation, the price of land, individual housing preferences, demographic trends, cultural traditions and constraints as well as the application of land use planning policies at the metropolitan level (Afrane & Amoako Citation2011).

In Ashanti Region, control of land is vested in traditional authorities which is held in trust for the community. Access to land for the use of indigenous households and individuals has been on the basis of essentially usufructory leasehold rights, regulated by the rulers or heads of various clans. The commercial transfers of land rights to non-indigenes and the outright sale of land have been recorded as early as the nineteenth century, as a result of imperial and colonial pressures. Over time, such changes have increased the complexity of land tenure and allocation systems considerably. The ultimate title of stool land lies with the community. Usufruct rights are held by individuals or families, and the chief (traditional leader) is allocated the role of a custodian. The responsibility of communal peri-urban or urban land delivery therefore rests with the traditional authority. In order to safeguard the land for future generations, the highest interest that both indigenes and strangers are allowed to hold is leasehold. The land reverts to the allodial community upon the termination of the lease. The emergence of urban monetarisation and commodification of land has changed the ownership of land from customary freehold to leasehold. In Peri-urban Kumasi like other parts of the country, the current reality is that some traditional leaders are using their positions of trusteeship to amass wealth by depriving indigenes of their land rights and extorting money from strangers, especially in areas where the tenets of good governance are not in operation (Ubink Citation2008). Despite the fact that the chiefs are customarily and constitutionally obliged to administer the land in the interest of the whole community, they generally display little accountability for any money generated and most indigenous community members are seeing little or no benefits from the leases.

For years however, growth and development of towns and cities in Ghana have occurred in the country without a comprehensive national urban policy. In the absence of such a policy framework or guideline, the development of urban centres cannot be guided towards achieving the goals of sustainable development of human settlement. It is heart-warming to note that Ghana is working on an urban policy whose goal, in line with the broader national vision, is to ‘promote a sustainable, spatially integrated and orderly development of urban settlements with adequate housing and services, efficient institutions, sound living and working environment for all people to support rapid socio-economic development of Ghana’. The overall objective of the policy is to promote efficient and sustainable development of urban centres. One of the specific objectives is to promote spatially integrated hierarchy of urban centres which enhances rural–urban linkages (Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development Citation2010). One can only hope that there will be the political will and commitment to sustain the process and bring this long awaited policy to fruition.

This article assesses the effects of urbanisation in peri-urban Kumasi. It is divided into four main sections. Section 1 deals with the introduction and sets out the aim of the article. Section 2 provides an over-view of the study area and the research methods. Section 3 presents the land market situation in Ghana, with particular emphasis on Kumasi and the analysis of land use changes resulting from urbanisation. It also examines the effects of urbanisation on agriculture, non-farm income generating activities and households’ socio-economic situation. Section 4 draws conclusions based upon which recommendations are made. It is our view that urbanisation presents both constraints and opportunities to the peri-urban communities in Kumasi but the opportunities are more.

2. Study methodology

2.1. Overview of study area

The study was conducted in peri-urban Kumasi. The Kumasi Peri-urban Interface (KPUI) has broadly been defined as the zone within a 20 km to 40 km radius of the city, although this is a fluid frontier that is constantly changing (Aberra & King Citation2005). The KPUI is undergoing dramatic changes including emergence of multiple land use, influx of new-comers and rise in rent value as the result of rapid urban growth. Three peri-urban communities (Esereso, Deduako, Appiadu) were selected ().

Kumasi is the capital of Ashanti Region and the seat of the Ashanti Kingdom. It is located in the transitional forest zone and is about 270 km north of the national capital, Accra. It is bounded to the north by Afigya Kwabre District and Kwabre East District, to the east by Ejisu-Juabeng District and Bosomtwe District, to the west by Atwima Nwabiagya District and to the south by Atwima Kwanwoma District. The centrality of Kumasi as a nodal city with major arterial routes linking other parts of the country has largely influenced its horizontal expansion. Urbanisation in Kumasi has mainly been due to the rapid increase in population as a result of urban development factors including its status as the regional capital, concentration of industrial activities and as the most commercialised centre in the region. Many villages considerably distant from the city have been swallowed up by the growth of Kumasi (KMA Citation2011).

2.2. Data collection and analysis

The data for this study was collected through a combination of both qualitative and quantitative research methods obtained from primary and secondary data sources. Primary data collection methods included focus group discussion, questionnaires and interviews with household heads, key informant interviews and observation. For each of the three communities, two focus group discussions were held for both men and women. Secondary data sources included content analysis of documents related to effects of urbanisation on peri-urban livelihoods.

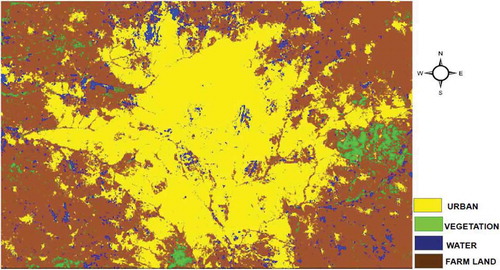

In addition, two Landsat images of path 194 roll 055 were obtained from ITC/KNUST Imagery Data Base to detect land cover changes. These include a 1986 image from Thematic Mapper (TM) sensor of Landsat 5-Satellite and a 2007 image obtained from Enhanced Thematic MapperPlus (ETM+) sensor of Landsat 7-Satellite. KMA and its periphery are subsets from the two scenes. The 1986 image is imperial while the 2007 image is in metric (metres). Using the 2007 image as reference, the 1986 image was re-projected.

The images were geometrically and radiometrically corrected. Moreover, the two images were normalised for the purposes of change detection. The satellite images were already geo-referenced in the War Office Spheroid and Tranverse Mercator Projection System. The ERDAS imagine 9.2 software was used for image pre-processing, classification and accuracy assessment. The supervised maximum likelihood algorithm was used to classify the 1986 and 2007 images. Eighty well-distributed sampled data sets were taken from the field as training sets for the images from which signatures were generated for image classification. Although KMA is characterised by complex and heterogeneous land cover types, the images selected were classified into only four classes namely vegetation, urban, water and farmland since the purpose of the study was to detect the extent of urban encroachment on farmlands and vegetative cover. The extent of each land cover type of the two images was analysed quantitatively in hectares to establish the relationship between urbanisation and land-use change.

Three peri-urban communities within 20 km radius from the city were purposively selected to represent peri-urban Kumasi. The selection was based on the co-existence of rural and urban livelihoods, proximity to Kumasi and the fact that these are places where multiple livelihood types are evolving in response to the effects of urbanisation. The study made use of snowball and purposive sampling techniques to select respondents due to the unavailability of records on people who have lost their farmlands to urban use. The household was the key unit of analysis and only heads of households were interviewed. Household was defined as ‘a group of people living and sharing meals cooked from one pot’ and taking individual and collective decision within domestic units. This excludes family members living elsewhere (Preston 1994, p. 203 cited in Brook & Dávila Citation2000). A total of 150 household heads were interviewed, fifty (50) from each community. Only people who had access to communal land and have stayed in the communities for not less than 20 years were interviewed in order to be able to explore the changes that have taken place through time, as a guide to future livelihood strategies in peri-urban areas. Respondents identified were classified according to their major economic activities or sources of livelihood in order to compare their responses. The categories were farm and non-farm employment (occupations other than agriculture). Data collected was analysed by the use of descriptive statistics by using Statistical Product for Service Solution (SPSS) and Microsoft Excel to generate frequency tables, cross tabulations, bar graphs and bar charts to analyse quantitative data. The summary was presented in tables and graphs. Qualitative data was recorded, transcribed and used as integral parts of written texts to better understand patterns and relationships between variables. Direct quotations from respondents were also used to analyse qualitative data.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Operation of the land market

The property market in Ghana is a market for the acquisition of undeveloped land. Antwi (Citation2002) in his study observes that 84.6% of respondents acquired a plot of land and developed it from scratch. The land market is complex and diverse and is also associated with high degree of uncertainty and widespread disputes (Gough & Yankson Citation2000). The land market is a dual one consisting of the state sector and the customary sector and is characterised by land value speculations, disputed ownership, unclear title to land and litigations. As Gough and Yankson (Citation2000) notes, customary land tenure operates alongside Western tenurial systems, resulting in a great uncertainty surrounding land policies and objectives. A significant proportion of the population relies on the informal land market (about 87%) to meet their demand for residential lots (Antwi Citation2002). But, this sector has a poor record keeping habit; as a result, multiple land sales abound in the land market. It is not uncommon for purchasers of land to be entangled in land disputes (Gough & Yankson Citation2000). Multiple allocations of land, title disputes between customary landowners and government, absence of registered documents and the unavailability of reliable database of land owners are the major problems confronting the urban land market (Antwi Citation2002). Purchasers of land in the Ghanaian urban centres are exposed to a huge risk of protracted litigation or loss of funds, as vendors may be incapable of transferring proper legal title to the purchasers.

Like the country as a whole, the traditional land sector supplies the bulk of developable lands in Ashanti Region. The traditional informal land market to a large extent is subject to the market forces of demand and supply. With increased demand relative to supply, land prices rise. This is however not a straight forward issue as there may be distortions from other factors. Thus, the informal land transactions reflect the demand and supply conditions of land in a given location but may be imperfect. Antwi (Citation2002) notes that the informal land market obeys the fundamental economic laws of demand and supply and the view that it is responsible for high, escalating and arbitrary land prices is unfounded. The present state of land market in Kumasi reflects the present level of accessibility to land and security of tenure. One of the major forces behind the state of the land market is the economic fortunes of Kumasi comprising on the one hand, a booming commercial sector dominated by retail business and a relatively ailing industrial sector. On the other hand in the PUI, there is a dwindling agricultural sector in which farmlands are under severe threat of displacement by residential occupation (Hammond Citation2011). Increasing urbanisation and population growth have resulted in rising demand for residential land in the three peri-urban communities studied. This is due to scarcity and high cost of land in the city centre. As noted by Afrane and Amoako (Citation2011), high land prices in the core and arterial roads of Kumasi force developers to seek lower prices in the peripheral areas. The price of land on the outskirts is universally much lower than the price of land zoned for housing or the development of services in the city. Peripheral land therefore, becomes a highly attractive target for investors and developers. In response, the chiefs are rapidly converting communal agricultural land or natural land space within peri-urban Kumasi for housing and commercial development, which, they then lease to outsiders. This development then leads to insecurity among community members who lose their agricultural land and are rendered landless. While the peri-urban communities may enjoy, among other things, improved infrastructure, proliferation of non-farm business activities and increased demand for goods and services, they no longer have access to land to grow their own food and generate income by selling the surplus on the market. The reality is that they have to contend with higher food prices and higher cost of living. Local people generally are unable to compete with outsiders employed in the formal sector. The local people thus find it hard to get land for both farming and residential purposes in their own community. This situation has arisen as a result of the expansion of the city and changes in land use.

3.2. Urban expansion and land use changes in KMA

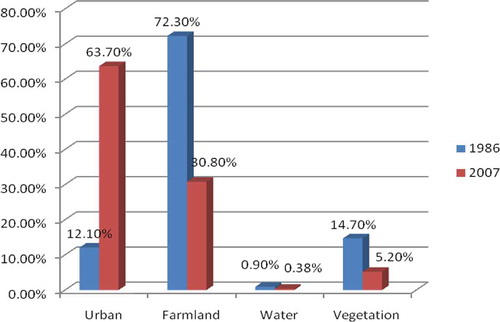

Land use changes from the natural physical environment to urban use mostly in the form of residential buildings, and are the clearest expression of the horizontal expansion of Kumasi in the three peri-urban communities. The changes in land use pose a serious threat to peri-urban livelihood since according to Davila (2002) most households in the peri-urban area depend on land either for food, water or fuel wood. To determine the extent of urban encroachment on farmlands and vegetative cover, 1986 and 2007 satellite images of KMA were classified into urban, farmlands, water and vegetative cover types and the results were compared. From the remotely sensed data, the post-classification change detection analysis of the land cover revealed the overall accuracy level of 87.4% for 1986 and 89.1% for 2007, with kappa indices of 0.74 and 0.80, respectively.

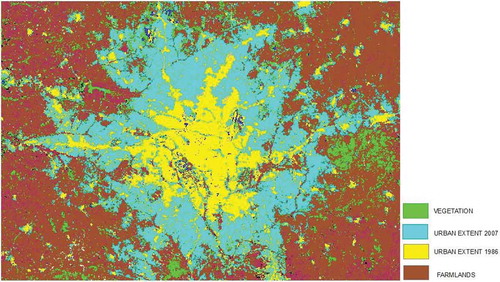

and present the area extent of KMA and land cover types computed from the 1986 Landsat TM image classification. In 1986, farmland was the most extensive land cover constituting about 72.30% of KMA. This was followed by vegetation, urban and water with 14.70%, 12.10% and 0.90%, respectively. The exceptionally high-land area indicated to be under cultivation in 1986 was partly attributed to the drought that characterised the 1983/84 growing seasons (Attua & Laing Citation2001). According to Attua and Laing (Citation2001), most parts of the terrain, especially covered by fallow vegetation could probably not have recovered enough from the drought and the bush fire effect on the vegetative cover. This was captured in the image resulting in areas showing spectral reflectance values similar to that of the recently cultivated fields.

Plate 1. The extent of land cover types of KMA in 1986.

Table 1. Proportion of land cover type from the 1986 Landsat TM image classification

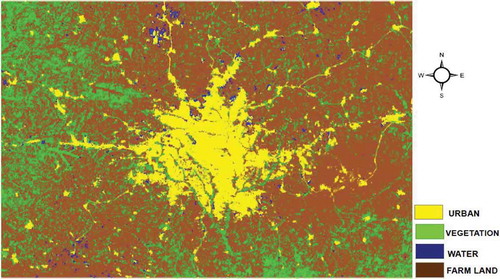

Contrary to the results presented in and , the change detection analysis from the 2007 satellite image shows that Kumasi has greatly expanded to absorb more than half of KMA (). The results corroborate Chirisa’s (2010) argument that the natural physical environment suffers greatly from the peopling of the peri-urban areas. This is because the expansion of the urban front increases demand for rural resources such as land, water, air and rural space to accommodate growing population and growing levels of economic activity (Braun Citation2007).

Plate 2. The extent of land cover types of KMA in 2007.

The results show that urban land use largely remains the dominant land cover (63.70%) in KMA, followed by farmland, vegetation and water with 30.8%, 5.2% and 0.38%, respectively (). A comparison of the 1986 and 2007 satellite images demonstrate an inverse relationship between urban expansion and farmland loss and other natural land cover types. shows that between 1986 and 2007, the proportion of urban share of the study area increased from 12.10% to 63.7% while the extent of farmland, vegetation and water drastically reduced from 72.30% to 30.8%, 14.7% to 5.2% and 0.9% to 0.38%, respectively. In other words, approximately, urban land use increased by 51.6% while farmland, vegetative cover and water reduced by 41.5%, 9.54% and 0.52%, respectively between the period of 1986–2007. Urban extent for 1986 and 2007 in a single diagram can be gleaned from . The study results confirm a similar study conducted by Attua and Fisher (Citation2011) in the New Juaben Municipality. Their findings revealed that the total urban area increased from 49.24% in 2000 to 59.19% in 2003, while vegetative cover diminished in extent from 63.7% to 40.8% during the same period.

3.3. Kumasi’s growth and peri-urban agriculture

A key challenge resulting from urbanisation is the rapid conversion of a large amount of prime agricultural land to urban land use (mainly residential construction), mostly in the urban periphery thereby causing rural land prices to escalate (Owusu & Agyei Citation2007; Gantsho Citation2008). Urbanisation has not only caused changes in occupation (from agriculture to non-agriculture) but also brought changes in how farmlands are acquired as well as in farming practices; as agriculture competes for space with urban settlement in the peri-urban communities studied.

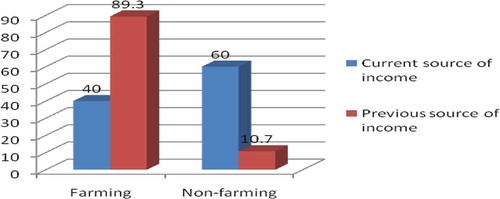

Data on household heads’ previous and current major source of livelihoods () indicate that there has been a shrinkage of the proportion of the population employed in the agricultural sector. Previously as many as 89.3% of the population had farming as their major source of livelihood as against only 10.7% of the population who were mainly non-farmers. The current picture shows 49.3% decline in the proportion of households who have farming as their main source of income.

Table 2. Age of respondents by main source of livelihood

Figure 3. Current and previous main source of income of household heads.

Previously people used to farm on communal (usufructory rights) land but now because of land commodification, farmland in the peri-urban communities is becoming more privatised. Farmland is mostly acquired through purchase, rent, gift, temporary borrowing and share cropping. The changes in land use and ownership have forced people to change occupations since it is difficult getting easy access to farmlands due to constant conversion of agricultural lands to residential buildings. Farm holdings have become increasingly smaller to be economically viable, a major disincentive to farming. This is what a farmer interviewed at Deduako had to say:

It is extremely difficult to get land to farm this time. Where one gets land it is usually not big enough for large-scale production. We cultivate the same piece of land continuously, yields go down from year to year and affect our income.

This supports Thuo’s (Citation2010) findings in peri-urban Nairobi that show that the increased decline in agricultural activities is attributed to the constant conversion of agricultural lands to urban uses which limits access to cultivated farmlands and reduces the quantity and quality of farmland. Similarly, Atamanov and Berg (Citation2011) observe in Kyrgyz Republic in Central Asia that small land size and poor land quality are in part among the reasons that make individuals choose employment in the non-farm sector over agricultural activities. Tacoli (Citation2004) describes this as a survival strategy for vulnerable households and individuals who are pushed out of their traditional occupations and who must resort to different activities to minimise risks and make ends meet.

The current study shows that most of the people who engage in farming as their main occupation are the aged. Farming in the peri-urban area is becoming an occupation for the aged who treat this as a secondary occupation (). The study also shows that peri-urbanism has taken over agricultural lands in the three communities studied. Out of the total of 150 respondents interviewed, 98.7% attributed the loss of farmlands to the expansion of Kumasi (). Respondents indicated that the influx of migrants into their communities and land commodification have increased demand for land and its economic value since rent value within the city is relatively higher. Chiefs in their quest to meet these rising demand for land rapidly convert agricultural lands into non-agricultural uses, especially residential. This supports the work of Ubink (Citation2006) in eight peri-urban communities in Kumasi. Plots of land are leased to non-community members leading to increasing insecurity of community members. The rights to land are transforming from freehold into a permissive right of tenant-like character, based on the leniency of the chief instead of the communal ownership of the land.

Table 3. Age group distribution of respondents by respondents’ view on whether the loss of peri-urban land is as a result of the expansion of Kumasi

Urban expansion has also led to changes in crop types cultivated and systems of farming, as farm sizes keep on reducing in the peri-urban areas. With the dwindling land size and commercialisation of peri-urban lands, farmers have responded in a variety of ways. Agricultural practices have undergone changes over the last two decades in response to the emergence of urbanisation (). Since large tracts of land are not available in the peri-urban areas and since large-scale cultivation of cash crops is not economically viable in the peri-urban area due to rising land value (Thuo Citation2010), 47.2% of the respondents who had farming either as a main or supplementary economic activity shifted from large-scale farming to small-scale farming. However, 33.3% shifted from the extensive cultivation of cash crops to intensive cultivation of vegetables. Another major factor that has stimulated vegetable production is the rising demand for vegetables in the city. As Satterthwaite et al. (Citation2010) rightly put it; urbanisation brings major changes in demand for agricultural produce both from increases in urban population and from changes in their diets and demands. Crops that are grown by vegetable farmers are mostly exotic crops for commercial purposes. Examples include carrots, shallots, cucumber and lettuce. Since the cultivation of vegetable crops such as cabbage is mostly facilitated by irrigation, most farms visited were along river banks.

Table 4. Changes in agricultural practices by the location of respondents

There has also been a shift from extensive cultivation to intensive cultivation as a result of declining land sizes. About 14% of the respondents who had farming either as the main or supplementary economic activity made a shift from extensive to intensive cultivation. The fallow system which characterises extensive cultivation has faded away in the three communities studied due to unavailability of extensive agricultural lands. Farming on building sites, open spaces and backyard farming, mostly for subsistence have become very common in the study areas as people take advantage to cultivate on any land that is not yet developed. Such opportunistic farming is however prone to tenure insecurity which is a major constraint to peri-urban farming. The uncertainty of when developers will need their land back poses a serious challenge to peri-urban farming. A woman in Appiadu commenting on this issue explained that:

I farm on any undeveloped land sometimes without the knowledge of the owner because it is difficult finding them to inform them that you want to farm on their land. The problem with this one is that, when the owner of the land is ready to develop his land, you go to the farm only to find all your crops gone. You cannot sanction him because he did not ask you to farm on his land. The situation is worrying...most people are discouraged from farming because of these uncertainties.

Though farmers cultivate on small scale, 5.6% indicated a shift from traditional farming to modern ways of farming. Farmers have resorted to the application of fertiliser and the practice of irrigation to increase yield. They gave the explanation that farmlands have lost their fertility due to continuous cultivation. However, application of fertiliser and irrigation are mostly associated with commercial vegetable growers. Farmers who cultivate on subsistence level still rely on the rain. Other measures taken to ensure high productivity are soil maintenance, pest and weed control management. However, most of the vegetable farms visited used untreated waste water to water their crops which poses serious health risks to consumers of these vegetables.

3.4. Effect on non-farm income generating activities

The growth of non-farm income generation activities is in response to the growing constraints on agricultural employment and the alternative job opportunities presented by urbanisation. This is due to the exposure of the previously rural area to urban monetised economy and integration into the urban system. According to Aberra and King (Citation2005), urbanisation creates opportunities in wage employment and trading, and provides access to services and infrastructure. Aberra and King’s view that urbanisation leads to the evolution of different livelihood types is perhaps serving as ‘pull factors’ attracting peri-urban dwellers to take advantage of the alternative non-farm employment opportunities. According to respondents, non-farm employment pays well and involves lower risks as compared to agriculture.

The survey results show that the number of people engaged in non-farm income generating activities has increased (). The increasing polarisation of non-farm employment is in line with the view of Hudala et al. (Citation2008) that with the increasing urbanisation, the traditional rural sector can no longer function as a major income generating activity in the peri-urban areas.

Table 5. Respondents’ view on the new job opportunities the growth of Kumasi has brought by location of respondents

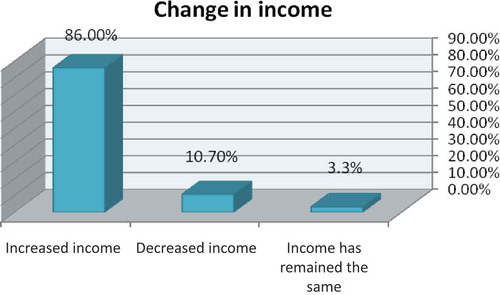

Figure 4. Respondent’s view on whether there has been a change in income in the last 5 years.

The increase in rural-non-farm employment according to IFAD (2001, cited in Tacoli Citation2002), and Braun (Citation2007) is usually seen in traditional regional development theory as the outcome of rural–urban development. In contrast, however, the growth of non-farm employment in peri-urban Kumasi is not triggered by agricultural growth that raises incomes and increases the demand for manufactured non-farm output, but rather it is triggered by the difficulty in accessing the peri-urban agricultural land. Non-farm employment therefore becomes more attractive and is most often a survival strategy adopted by peri-urban dwellers to escape from the extreme effects of urbanisation. Changes in major economic activities of respondents imply that the negative effects of urbanisation are greatly felt by people whose livelihoods depend on natural resources; however the emergence of urban monetary economy serves as opportunities for people who have the right assets and capacity to access the potentials of urbanisation.

The creation of the non-farm livelihood opportunities is largely attributed to the increasing connectivity and proximity of the study areas to the city. Availability of alternative sources of livelihood to absorb displaced indigenes is very essential when it comes to risk reduction. The research found that urbanisation has brought new livelihood opportunities not only into the study areas – Esereso, Deduako, and Appiadu – but also to nearby towns and Kumasi. The loss of farmlands has forced the landless, particularly the young men and women, to change occupation from farming to trading and other non-farm activities to earn a living. The young men have found jobs in the construction industry, the fastest growing sector, and other related industries in and around Kumasi. These job opportunities serve as safety nets which absorb peri-urban dwellers who have lost their farmlands to urban uses. However, the new opportunities have developed spontaneously. The specific livelihood opportunities that urbanisation has presented include trading/business, provision of services, vegetable farming, construction and manufacturing (). However, construction is the main employment sector. This is attributed to the proliferation of new infrastructure development projects arising from growing demands for houses in the peri-urban area. Trading/business follows construction. Respondents (mainly women and middle-aged men) however rated trading/business as the most reliable source of livelihood. People normally trade in cooked food, uncooked food such as vegetables and food stuffs, provision shop, electrical appliances, drinking spot, cosmetics, building materials and credit transfer. However, some respondents gave lack of start-up capital for their non-involvement in trading/business.

It is argued that the process of peri-urbanism is characterised by changing local economic and employment structures, from agriculture to manufacturing (Hudala et al. Citation2008). By contrast, this study indicates that the process of peri-urbanism in the study areas is not characterised by the concentration of heavy industrial activities as compared to other peri-urban areas in Kumasi such as Buoho, Barekese and Abuakwa, where the availability of Precambrian Rock has favoured the proliferation of quarrying industries. In the study areas, sachet water production is the most predominant industrial activity. The trend of Kumasi peri-urbanism is characterised by the changing employment structure from purely agricultural activities to commercial activities rather than heavy concentration of manufacturing industries. This trend of change supports the argument presented by Keiser et al. (Citation2004) and Songsore (Citation2009) that urbanisation in Africa is characterised by the absence of industrial expansion because many cities in Africa were developed as colonial administrative or trading centres rather than industrial zones.

3.5. Socio-economic effects of urbanisation

From the survey results, the urbanisation of Kumasi presents both opportunities and constraints to the people living in peri-urban Kumasi. Such opportunities and constraints manifest both at the household level and at the community level. Respondents’ view of urbanisation on their livelihoods support modernists’ notion that urbanisation initiates growth and development in the adjoining areas (Todaro 1977 cited in Maxwell et al. Citation2000; Gantsho Citation2008). At the household level, the study revealed that though some people have lost their farmlands, urbanisation has largely been a blessing, affecting their livelihoods positively. According to the respondents, there have been changes in their income situations. Majority (86%) of respondents were of the view that their incomes have increased. Respondents attribute this increment to access to multiple cash-income jobs. They indicate that urbanisation of what used to be rural areas has given them greater access to different cash income job opportunities. Households generate additional income by engaging in other secondary occupations such as trading/business, artisan and construction in order to sustain their livelihoods (diversified livelihood portfolios). They also generate additional income from rental and other services. Room renting has become a lucrative venture in the peri-urban communities studied, as a result of movement of people from the city to these areas. The growth of non-farm job opportunities serves as alternative sources of livelihoods which absorb people who have been displaced from their farmlands. The remaining 14% of the population represent those with falling incomes and those with stable income (). The reasons given by those with decreased income are reduction in farmland size, unemployment, high cost of living and loss of livelihood.

Respondents complain generally about the high cost of living. They identify a rise in food prices, high-rental charges, transportation problem, pressure on social amenities, inadequate capital and lack of access to loans, pollution and social vices as problems confronting them. For instance, at Deduako, respondents complain that due to their proximity to Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, rent has increased drastically as students keep moving to the area. Respondents however complain of the bad attitudes of some land lords/ladies who have taken advantage of the situation to eject old tenants since it is more profitable to rent to students than to non-students. Respondents explain that people who cannot afford the exorbitant rental charges either squat or relocate to more rural areas where rent is relatively lower.

As Aberra and King (Citation2005) note with urbanisation, rural spaces on the fringe of urban centres are exposed to all sources of vulnerability and poverty typical of urban livelihoods, including integration into a monetised economy and access to fewer safety nets. Urbanisation allows every commodity or service to be quantified in monetary terms and this serves as a major constraint on peri-urban livelihoods, as peri-urban dwellers now have to purchase almost all their food and other goods as well as pay for using services such as housing, transportation, health care and education (Cohen & Garret Citation2009).

Table 6. Effects of Kumasi’s growth on peri-urban interface

The research shows that the most vulnerable groups are the aged whose children are not engaged in any gainful employment and those who do not have financial resources to start trading. Lack of financial capital serves as a major constraint on peri-urban livelihoods. An old lady in Deduako commenting on the effects of Kumasi’s expansion on livelihoods said that:

How can one eat without money to buy food? It has become difficult to make a living because one can only eat only when one has money to buy food. Previously the entire ‘new site’ used to be farms, I could just get vegetables and food stuffs from the farm without paying for it, but now I virtually buy everything, even pepper, since I no longer have land to farm … We are suffering.

Some traders are of the view that petty trading is not as profitable these days as a result of unhealthy competition resulting from its proliferation. In view of the large number of people engaged in trading, daily sales are not encouraging. In one of the discussions held in Esereso, a woman had this to say:

Trading has become the most common job in this community because even if you want to go into farming, there is no land for such activity... People are either selling food items in small kiosks in front of their houses or operating in a container. People are converting their rooms to stores, even in the new developing areas (new site). Most houses have in-built provision shops that they operate. Now it seems almost every household has something to sell. My banana sometimes gets rotten due to its perishable nature. I have reduced the quantity I sell. Some people think that the influx of ‘new comers’ into the community will boost demand for goods yet most of them don’t buy from us. They leave home early in the morning for work and come home late in the evening.

Inadequate start-up capital and inability of most peri-urban residents to access loans from banks as a result of lack of collateral are major problems in the PUI. Access to financial capital is seen as a requirement for people to participate in the emerging non-farm activities. The urban poor are thus unable to take advantage of the opportunities that urbanisation presents. From the discussion held in Appiadu, a young man comments:

Even if you learn a skill, it is difficult getting money to open your own shop. After completing training as a carpenter, I have not been able to set up my own shop because of the cost involved and space to put up my shop. Most of the youth here have learnt a skill but because of this problem they have resorted to social vices such as prostitution and armed robbery.

The effects of urbanisation are not only manifested at the household level, they can also be witnessed at the community level (). At the community level, it was discovered that due to peri-urban proximity and connectivity to Kumasi, these areas have undergone vigorous infrastructure development. There is greater market demand for goods and services and opportunity to acquire skills and knowledge for capacity building. Out of the total number, a sizeable number of respondents (62%) attributed infrastructure development in their communities to the expansion of Kumasi. Residents now have greater access to facilities such as schools especially new basic schools owned by private individuals, electricity, roads, potable water supply, among others. For instance, improvement in the transportation system opens a window for people to get access to the city centre to transact business while the availability of and access to market widens the scope for non-agricultural income generating employment. The establishment of new infrastructure facilities has created new employment opportunities in the areas under study. While 16.7% of the respondents expressed the view that the expansion of Kumasi has created a market for goods and services due to the influx of migrants into the communities, 10.7% expressed the view that the growth of Kumasi has created the opportunity to acquire skills and knowledge for capacity building. Several studies demonstrate the importance of access to physical infrastructure and participation in non-farm activities and increased incomes. According to Mandere et al. (Citation2010), infrastructure development such as roads and markets provide outlets for people to purchase and sell their goods. Cheap and efficient transport infrastructure encourages peri-urban workers to commute daily to the city to access urban market and other services. Tacoli (Citation2004) asserts that access to urban markets is the key to increasing income for rural and peri-urban farmers while Barrett et al. (Citation2001) and Atamanov and Berg (Citation2011) demonstrate that access to infrastructure improves non-farm earnings and is also crucial for participating in non-farm activities.

At the community level, the negative effects of urbanisation are environmental degradation of natural resources and the growing unemployment rate especially among those who have limited access to livelihood assets to develop their livelihood strategies. Out of the total of 150 respondents, 7.3% were of the view that the expansion of Kumasi has created unemployment (meaning loss of jobs in this context). This is due to loss of farmlands and unavailability of alternative job opportunities. As the city expands to engulf agricultural lands, no conscious effort is made by authorities to create alternative jobs to absorb those who have been hard hit by the process of urbanisation. Ashong et al. (Citation2004) identified lack of employable skills and requisite qualifications among the causes of unemployment in the peri-urban areas. Due to this, many displaced indigenes are not able to acquire jobs both in the city and the community to secure better livelihoods. However, 3.3% of the respondents express poor sanitation as a result of the expansion of Kumasi.

The survey reveals that social cohesiveness has declined and social stratification increased. The loss of farmlands due to urbanisation has forced the landless, who are mainly the young men and women, to seek jobs in trading and other non-farm activities in and around Kumasi to earn a living. These young men and women leave their homes early each morning to work in the city, returning late in the evening. Social interactions among the people is thus minimised by this new lifestyle in all the three communities. The strong traditional ties or bonds that are expected among the rural folks are weakening as a result of the economic imperatives of the day. In addition, the influx of strangers, who are mainly civil servants and wealthy business people into these peri-urban communities, has heightened social stratification.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

After a thorough investigation into the effects of the horizontal expansion of Kumasi on peri-urban livelihoods, it comes to light that the KPUI presents both constraints and opportunities to people living in peripheral villages. The sprawling of Kumasi poses a serious threat to peri-urban dwellers that depend on natural resources for survival. This development has led to a decline or displacement of agricultural livelihoods.

In the three communities studied, people have lost their farmlands as a result of rapid conversion of agricultural lands to urban uses. Thus, the number of people engaged in agricultural activity has reduced. It is clear that Kumasi peri-urban dwellers are subjected to hardships in the form of high cost of living as a result of the emergence of urban monetary economy which allows for commercialisation and quantification of goods or services. Besides, the survey reveals that social cohesiveness has declined and social stratification increased.

This not-withstanding, peri-urbanism has brought in its wake multiple non-farm livelihood opportunities as alternative means of survival in the new urban economic landscape. The peri-urban areas by virtue of their proximity and connection to Kumasi have greater access to infrastructure, demand for goods and services and opportunity to acquire skills and knowledge. Multiple cash-income job opportunities such as trading, construction work, manufacturing among others as alternative means of livelihood have emerged.

With the rising demand for peri-urban lands and the huge indiscipline and insecurity in the urban land market, the article recommends the full implementation of the National Land Policy. This will help check abuses and irregularities in the system and control the rate at which agricultural lands are converted to urban land uses. In this regard, all actors in land use planning and zoning, land administration, land allocation and land utilisation have roles to play.

The research recommends that through a planned programme and coordinated efforts, alternative means of livelihood should be provided in these communities to ensure proper integration of peri-urban dwellers into urban monetary economy. This can be done through the diversification of the peri-urban economy and the development of the non-farm income generating activities. Peri-urban agriculture should also be encouraged in the form of intensive agriculture to ensure sustained urban and peri-urban food supply. Avenues for skills training and development could be created. Access to credit should be expanded to cover the peri-urban poor. The District Assemblies, traditional rulers in partnership with other agencies can play lead roles in this respect. The article, however, recognises the huge challenges that confront the District Assemblies and the local authorities in discharging these responsibilities. Weak institutional structure, inadequate human and financial resources, low levels of commitment, undue political interference, ineffective teamwork and chieftaincy and land disputes among others are noteworthy (Mensah Citation2005; Yeboah & Obeng-Odoom Citation2010) but these are not insurmountable.

To check urban sprawl, emphasis should be placed on the need to build compact cities (vertical development) in order to protect prime agricultural lands. It is the view of this article that the political will to formulate an urban policy, which is at the draft stage, be sustained. The necessary support needed to bring it to reality should be given by all stakeholders involved so as to address the problems of urbanisation and peri-urbanism. For a sustainable peri-urban development, all actors including peri-urban dwellers, urban developers and planners, Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, political elites, traditional leaders, non-governmental organisations and other development partners must come on-board.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kwadwo Afriyie

Kwadwo Afriyie: Department of Geography & Rural Development, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Knust, Kumasi, Ghana

Kabila Abass

Kabila Abass: Department of Geography & Rural Development, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Knust, Kumasi, Ghana

Janet Afua Abrafi Adomako

Janet Afua Abrafi Adomako: Department of Geography & Rural Development, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Knust, Kumasi, Ghana

References

- Aberra E, King R. 2005. Additional knowledge of livelihoods in the Kumasi Peri-Urban Interface (KPUI), Ashanti Region, Ghana: Development Planning Unit, and University College London [Internet]. [cited 2010 Oct 2]. Available from: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu/pui/research/previous/synthesis/index.html

- Afrane S, Amoako C. 2011. Peri-Urban development in Kumasi. In: Adarkwa KK, editor. Future of the tree: towards growth and development of Kumasi. Kumasi: University Printing Press; p. 92–110.

- Amoako C, Korboe D. 2011. Historical development, population growth and present structure of Kumasi. In: Adarkwa KK, editor. Future of the tree: towards growth and development of Kumasi. Kumasi: University Printing Press; p. 35–54.

- Antwi A. 2002. A study of informal urban land transactions in accra, Ghana. Our Common Estate Series. London: Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors.

- Ashong K, Adjei BF, Ansah EO, Naaso R, King RS, Kunfa E, Quashie Sam JS, Awudza JAM, Simon D. 2004. Who can help the peri-urban poor? (Boafo ye na) Adoption and Impact of Livelihood Activities on Community Members in the Kumasi Peri-Urban Interface-R8090 Revised Research Report 4, CEDEP-Kumasi, Ghana, KNUST-Kumasi, Ghana, CEDAR-Surrey, UK.

- Atamanov A, Berg M. 2011. Microeconomic analysis of rural non-farm activities in the Kyrgyz Republic: what determines participation and returns?. Wageningen: Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, University of Maastricht, Maastricht and Development Economics, Wageningen University.

- Attua EM, Fisher JB. 2011. Historical and future land cover change in a municipality of Ghana [Internet]. Earth Interactions 15: Paper No. 9. [cited 2012 Apr 4]. Available from: http://www.earthInteractions.org

- Attua EM, Laing E. 2001. Land cover mapping of the Densu Basin: interpretations from multi-spectral imagery. Bull Ghana Geographical Ass. 23:14–25.

- Barrett CB, Reardon T, Webb P. 2001. Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food Policy. 26(4):315–331.

- Braun von J. 2007. Rural-urban linkages for growth, employment and poverty reduction. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Brook RM, Dávila JD, editors. 2000. The peri-urban interface: a tale of two cities. School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences. London: University of Wales and Development Planning Unit, University College London.

- Chirisa I. 2010. Peri-urban dynamics and regional planning in Africa: implications for building healthy cities. JAERD. [Internet]. [cited 2010 Aug 13]; 2:16–25. Available from: http://www.academicjournal.org/JAERD

- Cohen JM, Garret LJ. 2009. Food price crisis and urban food (in) security [Internet]. London: Sage Publications on behalf of IIED; p. 469–470. [cited 2011 Jan 9]. Available from: http://eau.sagepub.com/content/22/2/467

- Dávila JD. 2002. Rural-urban linkages, problems and opportunities. Espaço & Geografia. 5:35.

- Gantsho SVM. 2008. Cities as growth poles: implications for rural development. A paper presented at Annual Meetings Seminar; 2008 May 14–15; Maputo, Mozambique.

- Gough KV, Yankson PWK. 2000. Land markets in African cities: the case of peri-urban Accra, Ghana. Urban Stud. 37:2485–2500.

- Gregory P. 2005. A synthesis of peri-urban research of Kumasi, Hubli-Dharwad and Kolkata Peri-urban Interfaces [Internet]. Final Report on Project R8491, DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme, Development Planning Unit, University College London. [cited 2010 Jul 23]. Available from: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu/pui/research/previous/synthesis/index.html

- Hammond DNA. 2011. Harmonising land policy and the law for development in Kumasi. In: Adarkwa KK, editor. Future of the tree: towards growth and development of Kumasi. Kumasi: University Printing Press.

- Hudala D, Winarso H, Woltjer J. 2008. Peri-urbanisation in East Asia: a new challenge for planning. Int Dev Plan Rev. 29:29–44.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J, Caldas de Castro M, Smith AT, Tanner M, Singer HB. 2004. Urbanisation in sub-saharan Africa and implication for malaria control. Princeton, NJ: Office of population Research, Princeton University.

- [KMA] Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly. 2010. Development plan for Kumasi metropolitan area (2010–2013). Kumasi: Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

- [KMA] Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly. 2011. KMA Medium Term Development Plan 2010–2013. Kumasi: Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly, Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Environment, Ghana.

- Mandere MN, Ness B, Anderberg S. 2010. Peri-urban development, livelihood change and household income: a case study of peri-urban Nyahururu, Kenya. JAE RD. [Internet]. [cited 2010 Aug 17]; 2:73–79. Available from: http://www.academicjournal.org/JAERD

- Maxwell D, Levin C, Armar-Klemesu M, Ruel M, Morris S, Ahiadeke C. 2000. Urban livelihoods and food and nutrition security in Greater Accra. Ghana: IFPRI.

- Mensah J. 2005. Problems of district medium-term development plan implementation in Ghana. Int Dev Plan Rev. 27:245–270.

- Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. 2010. Draft national urban policy plan, Accra.

- Narain V, Nischal S. 2007. The peri-urban interface in Shahpur Khurd and Karnera, India. Env. Dev. 19:261–273. doi:10.1177/0956247807076905. [Internet]. [cited 2010 Aug 1]. Available from: http://eau.sagepub.com/content/19/1/261.

- Njoh AJ. 2003. Urbanisation and development in sub-saharan Africa. Cities. 20:167–174.

- Obeng-Odoom F. 2010. ‘Abnormal’ urbanization in Africa: a dissenting view. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 29:13–40.

- Olujimi J. 2009. Evolving a planning strategy for managing urban sprawl in Nigeria. J Hum Ecol. 25:201–208.

- Owusu G, Agyei J. 2007. Changes in land access, rights an livelihoods in peri-urban Ghana: the case of Accra, Kumasi and Tamale metropolis. Accra: ISSER.

- Potter RB, Binns T, Elliot JA, Smith D. 2008. Geographies of development: an introduction to development studies. 3rd ed. London: Pearson Education Limited.

- Satterthwaite D, McGranahan G, Tacoli C. 2010. Urbanisation and its implication for food and farming, Royal Society Publishing. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 365: 2809–2820. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0136. [Internet]. [cited 2011 Aug 1]. Available from: rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org

- Songsore J. 2003. Towards a better understanding of urban change: urbanisation, national development and inequality in Ghana. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

- Songsore J. 2009. The urban transition in Ghana: urbanisation, national development and poverty reduction. A Study Prepared for the IIED as Part of Its Eight Country Case Studies on Urbanisation. Accra: University of Ghana.

- Tacoli C. 2002. Changing rural-urban linkages in sub-Saharan Africa and their impacts on livelihoods: a summary. Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies, Working Paper 7. London: IEED.

- Tacoli C. 2004. Rural-urban linkages and pro-poor agricultural growth: an over view. London: IIED.

- Thomas S. 2008. Urbanisation as a driver of change. Arup J. 43:58–66.

- Thuo ADM. 2010. Community and social responses to land use transformations in the Nairobi Rural-urban Fringe, Kenya [Internet]. Field Actions Science Reports, Special Issue 1-Urban Agriculture. [cited 2009 Aug 1]. Available from: http://factsreports.revues.org/index435.html

- Ubink J. 2006. Land, chiefs and custom in peri-urban Ghana. A paper for presentation on ‘Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Community Rights and Tenure Arrangements’, as part of the International Conference on Land, Poverty, Social Justice and Development ISS and ICCO; 2006 Jan 9–14; The Hague.

- Ubink J. 2008. Negotiated or negated? The rhetoric and reality of customary tenure in an Ashanti village in Ghana. Africa. 78:77–96.

- Yeboah E, Obeng-Odoom F. 2010. ‘We are not the only one to blame: District Assemblies’ perspectives on the state of planning in Ghana. Commonw J Local Governance. Issue 7:78–98.