Abstract

This article examines the role of sporting mega-events in the reconfiguration of the urban landscape, to understand some of their impacts upon social groups directly affected by large projects involved in the construction of the so-called ‘Olympic City’. It studies the case of Rio de Janeiro, which will host the 2014 football World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympic Games. The article seeks to demonstrate how mega-events are being instrumentalized by local political and economic elites, especially by a coalition of ambitious civic leaders, private entrepreneurs, and local real estate interests, who exploit the event-related sense of urgency, mobilization, and consensus in order to remake the city in their own image. Through the study of a series of projects conceived with the mega-events deadline in mind, and with a special emphasis on Porto Maravilha’s port revitalization project, the article shows how such an event-led planning model fosters an exclusive vision of urban regeneration. It sustains that such vision can open the way for the state-assisted privatization and commodification of the urban realm, and promote the rise of a new, ‘exceptional’ form of neo-liberal urban regeneration in the Latin American landscape, which serves the needs of capital while exacerbating socio-spatial segregation, inequality and social conflicts.

Introduction

In October 2009, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced its decision to select Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, as the host for the 2016 Summer Olympic Games. Two years earlier, Brazil had been selected by the FIFA as the host country for the 2014 football World Cup and Rio de Janeiro would figure among 12 host cities, holding the Cup finals at the famous Maracanã stadium. The city would thus welcome two of the world’s most important sporting events within a 2-year span. Local authorities immediately began preparing for this unprecedented ‘double whammy’, launching a series of large-scale projects to improve the city’s urban image and update its infrastructure.

This article examines the role of sporting mega-events in the reconfiguration of the urban landscape, to understand some of their impacts upon population groups directly affected by large projects involved in the construction of the so-called ‘Olympic City’. Following Milton Santos Citation(2001) for whom ‘globalization is the culminating point of the internationalization of the capitalist world, in all its perversities’, it aims to demonstrate the influence of globalization, not only in the economic sphere but also in the production of urban space, especially in the legitimization of urban policies and new paradigms of action.

The production of the Olympic City is the result of an intense image construction process that mobilizes multiple agents and complex territorial strategies. It requires important spatial reconfigurations, often following a market orientation and a managerial approach that can deeply transform both the city and its government (Sanchez 2010). Based on the projection of an illusory image of urban revitalization that will benefit all citizens, it often results in a commodification of urban space and in socio-spatial exclusions that have an alienating effect upon local residents (Broudehoux Citation2007).

The projection and dissemination of synthetic images of the city is not a new phenomenon in Rio de Janeiro’s political landscape. As Brazil’s national capital for over 200 years, and due to its extraordinary geographical location, Rio is a city whose high symbolic profile has long marked its development. However, the opportunity to host coming mega-events, culminating with what has come to know as ‘Rio’s turn’ (A Vez do Rio) or ‘Rio’s moment’ (O Momento Rio) can be understood as a unique occasion to attract global interests, inward investment, and to improve the city’s ‘primitive accumulation of symbolic capital’ (Torres Ribeiro Citation2006).

Through an analysis of many of Rio de Janeiro’s event-related projects, this article seeks to demonstrate how mega-events are being instrumentalized by local political and economic elites, especially a coalition of ambitious civic leaders, private entrepreneurs, and local real estate interests, who exploit the event-related sense of urgency, mobilization, and consensus in order to remake the city in their own image. Through the example of a series of projects conceived with the mega-events deadline in mind, the article demonstrates how such an event-led planning model fosters an exclusive vision of urban regeneration that can open the way for the state-assisted privatization and commodification of the urban realm, thus serving the needs of capital while exacerbating socio-spatial segregation, inequality, and social conflicts.

Much of this analysis rests upon the collective work of a series of scholars involved in two integrated Brazilian research laboratories, the Laboratório Globalização e Metrópole (Globalization and Metropolis) of the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) in Niterói and of the Laboratório Estado, Trabalho, Território e Natureza (ETTERN) (State, Work, Territory and Nature) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Researchers from these groups have explored emerging planning models since the early 1990s (Bienenstein Citation2001; Sánchez Citation2010), analysed large urban projects and studied mega-events (Oliveira et al. Citation2007; Lima Citation2010; Vainer Citation2011). Over the years, international researchers have also collaborated with these groups and helped to define some of the issues related to the relationship between mega-events and urban development in countries of the global South (Broudehoux Citation2001, 2007; Horne Citation2006; Mabin Citation2010; Stavrides Citation2010; Freeman Citation2012; Gaffney et al. Citation2012).Footnote1

The article begins with a discussion of how the transformation in Rio’s urban policy, especially the adoption of strategic planning, would create the conditions for the hosting of the coming mega-events. The article then examines, in general terms, the role of mega-events in urban regeneration and discusses their socio-spatial impacts on the urban landscape. A third section traces the recent history of mega-event planning in Rio de Janeiro, detailing some of the urban transformations related to the hosting of the 2007 Pan American Games. Urban projects planned for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics are then discussed, along with some of the social movements that have developed to contest their realization. The next three sections analyse more closely the case of Porto Maravilha, Rio’s port revitalization project, which embodies many aspects of the exceptional urbanism that has come to characterize the event-city. The project’s impact on socio-spatial polarization is examined, along with the diverse resistance movement that have emerged in reaction to this mega-project. The article concludes with a criticism of the exceptionalism that has come to characterize mega-event planning, and ends with a brief commentary on the significance of the popular unrest that has rocked Brazil in June 2013.

Strategic planning and mega-events in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro’s incursion into the realm of mega-events as a means of positioning itself among great world cities goes back to the early 1990s, with the hosting of the 1992 World Summit on the Environment. Over the next decade, Rio would more firmly embrace the mega-event model of urban development as a core promotional strategy to attract global capital, hosting, among others, the 2007 Pan American Games, the 2011 Military Games, the 2010 World Urban Forum, the 2013 World Youth Day, the 2014 FIFA World Cup, and the 2016 Olympic Games.

Several factors have conspired to help launch this coming ‘Rio moment’. The first was the adoption, in the 1990s, of a neo-liberal mode of governance, often referred to as strategic planning. In many Brazilian cities, this neo-liberal managerial approach was perceived as the only viable option to face the new conditions imposed by globalization and to engage in the ‘mythical’ inter-urban competition for an increasingly mobile global finance capital (Vainer Citation2009). Planning strategies focused on improving the city’s image, repackaging its assets and marketing its competitive advantages in order to attract foreign investors, tax-paying residents, wealthy tourists, and professionals from the so-called creative class.

In order to get a fuller understanding of the city’s new urban policy orientation, it is important to examine, even briefly, some relevant features of the period stretching from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s. This can be viewed as the last period during which urban planning activities influenced urban politics and had a real impact upon urban transformations, both as projects and policies. Legacies of this era include the consecration, in the city’s Master Plan, of housing and environmental policies, the drafting of general guidelines regarding urban revitalization, the end of slum clearance, the adoption of public participation in all planning stages, and the groundwork for the adoption of a progressive land tax (IPTU). These innovations are undoubtedly related to Brazil’s re-democratization process, still ongoing in the immediate post-constitutional era of the late 1980s. For most municipal city planners, this period represents the apex of their prestige and effective internal influence (Oliveira Citation2003).

Indeed, the 1990s saw a great mutation in urban politics, with deep impacts on the city’s institutional structure and its mode of management, in favour of a new symbiotic relationship between the public and private sector. This relationship could be seen as a legitimation of old alliances, especially between real estate capital, and the municipality’s executive power (Bienenstein Citation2001; Oliveira Citation2003; Lima Citation2010). During this period, planning activities were reduced to licensing and inspection, and limited to the promotion of adaptive strategies serving the real estate market and the privatization of public services. Such political reorientation greatly impeded the implementation of policies that could have help reduce social inequality (Oliveira Citation2003).

While the urban restructuring plans (PEU) elaborated for different urban neighbourhoods were a central feature of the 1989 Master Plan, these planning instruments were gradually set aside. One of the dominant features of this restructuring period, initiated in 1996, is the total absence of reference to the Master Plan – or to any general plan for the city for that matter. The pursuit of performance and of concrete, visible, and marketable results, marked much urban policies undertaken in this period, with emblematic projects such as Rio Cidade, greatly influenced by international models for the regeneration of commercial districts.

Rio thus adopted an entrepreneurial mode of governance in the mid-1990s, modelled after the strategic planning approach pioneered in Barcelona, whose highly acclaimed Olympic revitalization was widely emulated around the world, especially in Latin America. Barcelona’s success in mobilizing private sector resources to revitalize its urban infrastructure and its use of culture and sporting events to rejuvenate a depressed urban image, attract external capital, and position itself in the global economy, would greatly influence Rio de Janeiro’s new urban vision (Ferreira Citation2010). In fact, Catalan consultants was directly involved in the elaboration of Rio’s strategic plan, especially Jordi Borja, an important factor in the export and diffusion of the Barcelona model and president of one of the city’s main consulting firms (Nu Citation2012). By the end of 1995, Rio would boast Latin America’s first strategic plan, the Strategic Plan of the City of Rio de Janeiro (Plano Estratégico da Cidade de Rio de Janeiro), which promised to restore tourism as the city’s ‘natural’ vocation and to insert Rio in the circuit of sporting mega-events as a viable way to visibilize the city and attract inward investment (Acioly Citation2001).

Rio’s recent adoption of mega-events as a development strategy is also the result of a rare political alignment at the municipal, provincial, and Federal levels, with a strong political alliance between President Lula’s Worker’s Party, Rio de Janeiro state governor, Sergio Cabral, and Rio’s mayor, Eduardo Paes. This unified political front would be behind Rio’s successful Olympic bid, after two failed attempts to get the Olympics (2004, 2012), and the successful hosting the 2007 Pan American Games.

Mega-events and urban regeneration in critical perspective

In the context of ongoing global economic restructuring, many cities throughout the world have taken an entrepreneurial approach to urban territorial management so as to efficiently compete on the global market (Harvey Citation1989). In this light, the staging of mega-events, including world exhibitions, international conferences or sporting events such as the World Cup and the Olympic Games, has come to be perceived by many city governments as a development strategy and a potent vehicle for post-industrial adjustment (Greene Citation2003; Short Citation2008; Hiller Citation2012; Smith Citation2012). Not only is hosting high-profile events seen as a rare opportunity for place promotion, helping enhance global visibility through media coverage and advertising, but it is also perceived as a panacea for economic regeneration, stimulating domestic consumer markets while capturing mobile forces of capital (Whitson & Macintosh Citation1996; Hiller Citation2000; Miles & Miles Citation2004; Gold & Gold Citation2011). It also represents an important legitimating factor to leverage urban interventions, allowing local governments to reprioritize the urban agenda while enabling the accelerated implementation of key projects and facilitating the attraction of investors to finance those projects (Chalkey & Essex Citation1999; Judd Citation2003; Essex & Chalkley Citation2004; Smith Citation2005; Hiller Citation2006).

Some scholars view mega-events as one of the dominant urban policies used to restructure and reconstruct urban areas around the world. Mega-events have more recently been characterized as much more than simple catalysts for urban development, but as powerful engines in the neo-liberal reconfiguration of the city, promoting the privatization and commodification of urban space, and the implementation of market-oriented economic policies (Peck & Tickell Citation2002; Hayes & Horne Citation2011; Vanwynsberghe Citation2012). Some critics, especially among Brazilian scholars, are going further, suggesting the mega-events are deeply involved in the reconfiguration of power structures at the local and national levels and are used to impose a new neo-liberal order marked by authoritarianism and exceptionalism (Vainer Citation2011).

In Brazil, this neo-liberal mode of governance was marked by an authoritarian conceptualization of the exercise of power, based on consensus-building and selective participation, and by the growing role of the private sector in urban management. Swyngedouw Citation(2010) describes the competitive city as dependent upon a reconfiguration of the political order, with the inclusion of private actors and other unelected participants in the act of governing. For Castells and Borja Citation(1996), strategic planning requires the cessation of the rigid separation between public and private sectors, which Vainer (Citation2009) reinterpreted as the submission of the common good to private interests. Entrepreneurial strategic planning also relies upon institutional flexibility, which enables local authorities to reformulate planning regulations, by adapting zoning and land-use plans, and granting tax exemptions and legal derogations to better serve investor interests (Lima Citation2010).

According to such views, neo-liberal leaders have learned to exploit a crisis discourse of fear, violence, and economic decline to generate a popular consensus about major urban interventions (Arantes Citation2009; Vainer Citation2009). This crisis requires a rapid and appropriate response that cannot allow for lengthy and wasteful political discussion, and thus represents an opportunity to resort to authoritarianism (Gusmão de Oliveira Citation2011).Footnote2 Operating on the same structure as the ‘shock and awe’ of disaster capitalism described by Klein Citation(2007) – a technique used to impose radical free-market neo-liberalism upon local economies – mega-events allow coalitions of political and economic agents to exploit their tight schedule and fixed deadline to deliberately induce an artificial crisis, galvanize large projects, and facilitate the adoption of neo-liberal urban policies (Gaffney Citation2010; Hayes & Horne Citation2011). It is through their capacity to generate a sense of urgency – what Stavrides Citation(2010) calls an ‘Olympic state of emergency’ – that mega-events create unique, exceptional conditions that facilitate and accelerate the realization of large-scale urban projects. The added pressure exerted by international federations such as the FIFA and the IOC) for the production of a flawless event pushes ambitious civic leaders to take whatever measures they deem necessary to achieve success.

The unique planning conditions resulting from this state of emergency has pushed Vainer Citation(2011) to qualify the mega-event host city as a ‘city of exception’. This concept draws upon Agamben’s (Citation2005) notion of the ‘state of exception’, a theory that describes the suspension of laws in times of crisis and emergency in order to face an unexpected ‘necessity’. According to Vainer Citation(2011), exceptions literally become the rule as they represent essential tools to help bypass the democratic political process in the implementation of mega projects. The hosting of world-class events legitimizes the adoption of an exceptional politico-institutional framework that authorizes the relaxation of certain rules and obligations in the implementation of urban interventions that will benefit the event. The event-city is thus characterized by the disruption of accepted legal and social norms; the suspension of established procedures, restrictions, and controls; the reformulation of planning regulations; the circumvention of existing laws; the lifting of safety standards; and the introduction of highly restrictive regulatory instruments to ensure compliance with the stipulations of local and global organizers and better serve investor interests (Lima Citation2010; Hayes & Horne Citation2011).

This state of exception also allows the imposition of extra-legal forms of governance as non-elected agents, including beneficiaries of international capital sponsorship, like the IOC and the FIFA, come to play a key role in local decision-making (Andranovich et al. Citation2001; Burbank et al. Citation2001; Alegi Citation2008; Lenskyj Citation2000, 2008; Gusmão de Oliveira Citation2011). Extraordinary powers are thus given to public–private coalitions to carry out massive urban transformations without any form of accountability. The magnitude of demands made by powerful organizations like the FIFA and the IOC, and the scope of projects to be undertaken have given these coalitions the licence to take exceptional measures in order to reshape the city for the needs of the event, its sponsors and local partners.

Mega-events thus result in the creation of self-governing extraterritorial enclaves, constituted as special autonomous zones – a kind of a state within the state – where political and ethical responsibilities are blurred and sovereign law is suspended. In the Brazilian context, Gusmão de Oliveira Citation(2013) goes as far as talking of the emergence of a parallel form of government and a parallel form of justice. She describes the political and juridical autonomy that characterizes mega-events franchise holders like the FIFA and the IOC, who have been able to institutionalize their own unique approach to the exercise of power. They are thus able to remake the city, in both its temporal and spatial dimension, by imposing their own time frame upon urban development, and creating archipelagos of extraterritoriality, which often become exclusive commercial territories for their sponsors and commercial allies.

The recent history of mega-events in Rio de Janeiro

Rio’s first incursion into the realm of sporting mega-events in the twenty-first century goes back to the hosting of the 2007 Pan American Games. The scale of the event was smaller than the coming mega-events, with a budget (USD 1.94 billion) equivalent to one-eighth of the Rio’s initially projected Olympic expenditures (USD 15.2 billion) (Oliveira Citation2009). Post-event evaluations have demonstrated how event-related state investments were concentrated in urban areas that benefited local real estate development. In spite of official claims, in the candidacy dossier, about the equitable distribution of event-related interventions, distributed in four different areas of the city, namely Barra da Tijuca, Deodoro, Maracanã and Sugarloaf (Pão de Açúcar), in reality, most activities related to the Pan American Games were concentrated in upscale sectors of the city, including Pão de Açúcar and Barra da Tijuca (Mascarenhas et al. Citation2011). Barra da Tijuca, an elite suburb of 300,000 in the western part of the city, would be the heart of activities.

The official intent in concentrating activities in this elite sector of the city was to protect the athlete’s safety and well-being, while ensuring that the city’s world image would not be tainted by sights of violence, disorder, and poverty. In reality, this choice was partly motivated by the relocation of many local companies from Rio’s downtown to this emerging new secondary urban centre, specialized in the new business and in the advanced tertiary economic sector. Investments and infrastructure improvements were therefore partly biased in favour of a certain economic elite.

The athlete’s village or Vila Panamericana was presented as an investment that could help overcome an urgent urban crisis and be showcased as a development success. Built upon reclaimed marshland, it intended to stimulate the local real estate sector and to accelerate the urbanization of the area. However, the project would turn out to be a white elephant, and was plagued with major structural problems due to unstable land conditions. The project was also criticized as a direct transfer of public funds to the private sector (Mascarenhas et al. Citation2011). Although publicly funded,Footnote3 the athlete’s village was ceded to be commercially exploited as a residential condominium by Agenco Engenharia e Construções S.A., an important real estate company in the Barra da Tijuca landscape. While units were sold rapidly, many still remain uninhabitable today.

The largest project built for the Pan American Games is the João Havelange Olympic Stadium, which was the main venue for the event. Known as the Engenhão, it was built in the working class neighbourhood of Engenho de Dentro, north of the city centre. Although the official rhetoric had promised that the stadium would help revitalize the neighbourhood in which it was inserted, this de-contextualized punctual project had little positive impact upon its urban surroundings, apart from enhancing traffic congestion (Martins da Cruz Citation2010). The realization of the stadium benefited from many exceptional conditions, including the relaxation of local zoning regulations. Built in a low-rise sector with a predominantly horizontal urban fabric, regulations around the stadium now allow to build in excess of 12 storeys. Real estate development in the area is also capitalizing upon the symbolic value of the Engenhão to market new apartments and condominium.

In spite of its high construction cost, evaluated at USD 175 million, no relevant infrastructural investment was done in the stadium’s surroundings. After the Games, the stadium was leased to the privately owned Botafogo Football Club, who made little use of its state-of-the-art athletic facilities and only used the stadium for football games and occasional mega-concerts. In April 2013, experts deemed the Engenhão unsafe for public use after major structural defects were found in its roof. The 7-year old stadium was thus closed for an undetermined period. Its very short usable lifespan reopened public debate about the waste of public funds on sporting infrastructure and allegations of overbilling during its construction resurfaced.

Of all sporting venues built with state funds in preparation for the Pan American Games, not a single one, including the Engenhão, was opened for community use after the Games (Sánchez & Bienenstein Citation2009). Rio’s Pan American Games were nonetheless among the most expensive ever hosted, with public expenditures of USD 3.3 billion, many times above the initial estimated cost of USD 224 million. The participation of the private sector was of only 20%. For Sánchez and Bienenstein Citation(2009), such disproportionate contribution demonstrated the unbalanced reality of public-private partnerships in the production of metropolitan space.

Many patterns of interventions that had already emerged at the time of the Pan American Games would set the tone for what was to follow with Rio’s twenty-first century sporting mega-events. For example, Olympic investments remained concentrated in Rio’s western elite suburb at Barra da Tijuca, where the dream of building a magnificent, post-card perfect vision of modern Rio is still very much alive. Olympic projects continue to be planned as instruments of real estate development, with the implementation of modern infrastructure and telecommunications to help promote land valuation, and boost the local hotel and cultural industries.

The ad hoc and market-friendly nature of interventions, marked by a total disregard for long-term development and a lack of concern for the local social and material context, would guide the way for future Olympic development. However, the most lasting impact of this initial venture into event-led redevelopment was the powerful consensual rhetoric that would paint mega-events as a panacea for the ongoing urban crisis, and a quick fix solution for urban regeneration.

However, the consensus regarding mega-event benefits was not complete and the Pan American Games gave rise to several resistance movements, as people organized protests, raised questions, and denounced injustice, resulting in a few key victories. Among these stands Vila do Autódromo, a well-established low-income neighbourhood near the Olympic Village, whose existence was threatened by repeated eviction orders. Its persistence in demonstrating its rights and claiming its legitimacy warranted its survival. Another victory concerns Rio’s famous Flamengo Park, near the city centre, and its protection as part of Rio’s public heritage, after it was threatened by the city-approved expansion of the privately owned Glória Marina, as part of the city’s preparations for the Pan American Games. It was under pressure from resistance movements that the state recognized the commercial project as a violation of the Park’s landscape and social heritage and that the development project was halted in extremis (Mascarenhas et al. Citation2011).

The politics of mega-events: Rio’s 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics

For the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, urban projects were planned with a vision that confirmed the permanent character of the prevailing market-friendly planning orientation, at once elitist, segregationist, and exclusive. Rio’s mega-events were put forward by public policies that promote the concentration of power and capital, and the privatization of public services and public space. Large private engineering and construction firms like Odebrecht and OAS Ltd (to name the most ubiquitous) have expanded their influence in urban affairs, winning bid after bid for major public works and many World Cup and Olympic-related project. Among others, these firms are involved in the construction of the new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors, the subway expansion, the Maracanã Stadium makeover, and the Porto Maravilha, Rio’s vast port revitalization project (Oliveira Citation2013). These investments have strengthened the role of these private companies in the transformation of the city’s urban landscape, especially in transportation management.

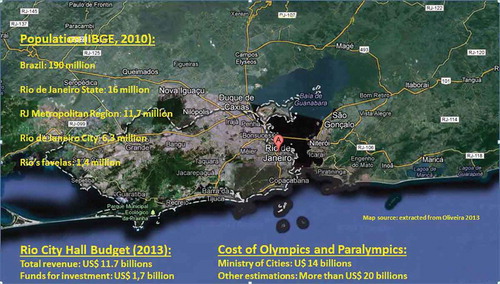

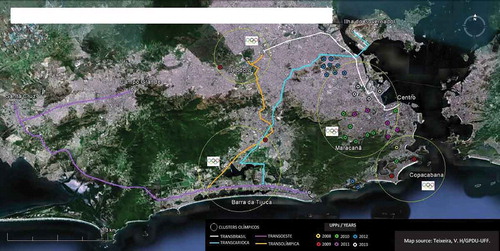

In Rio, the current economic, social, and politic conjuncture, intensified by the promotion of upcoming mega-events, has favoured the adoption of opportunistic projects, pushed by local economic agents. Many public projects were used as self-serving marketing initiatives for the municipal government, who promised a positive Olympic legacy, especially in terms of sports and urban infrastructure, and public transportation. It is estimated that more than USD 20 billion will be spent in Rio de Janeiro on Olympic-related investments, the majority of which will come from diverse levels of government, in the form of subsidized loans or direct investments. And even though many of these investments are not exclusively serving the Olympics or the World Cup, the realization of the two coming mega-events clearly justified the federal government’s decision to spend more money in Rio de Janeiro – Brazil’s new ‘showcase’ – than in any other Brazilian city. The government of the State of Rio de Janeiro similarly concentrated its investments in the state capital, while the city government changed the order of priority of its municipal investments to suit the needs of coming mega-events (Oliveira Citation2013) ( and ).

For example, thanks to the Olympics, about USD 4 billion of public money (both federal loans and state funds) is being spent on a 16-km subway expansion towards Barra da Tijuca, where many Olympic venues, including the Olympic Village, will be concentrated. To improve accessibility, City Hall is spending USD 1.3 billion to build exclusive lanes for the new BRT system connecting Barra da Tijuca to the city centre. Massive in both scope and scale, these BRT lines, which are the centrepiece of Rio 2016s transportation project, represent the largest one-off transportation investment in Rio de Janeiro’s history. Planned to extend over a distance of 150 km, their construction will result in the dislocation of tens of thousands of residents and will have permanent social, physical, and functional effects on the urban landscape. Furthermore, according to Gaffney et al. Citation(2012), the confluence of three of the four BRT lines in a 5-km radius is directing urban mobility to this limited region of the city, potentially shifting its urban centrality. The immense wetland region is undergoing vertiginous real estate speculation, increased traffic congestion, and is experiencing significant environmental stresses.

As had been the case with the hosting of the 2007 Pan American Games, Olympic preparations confirmed the centrality of Barra da Tijuca as a priority development area, despite its condition as an elite suburb already blessed by generous public investment. The government is clearly favouring Barra in its mass transportation spending while the working-class residents of the northern and western periphery continue living with inadequate transportation, despite having ten times Barra’s population and more pressing needs in terms of mobility (Oliveira Citation2013) ().

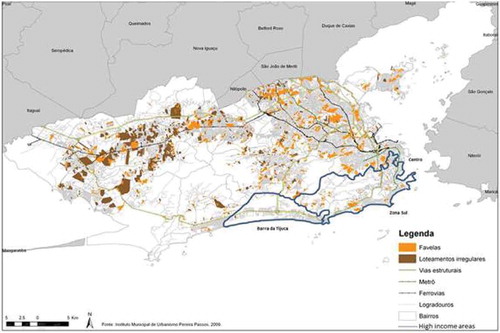

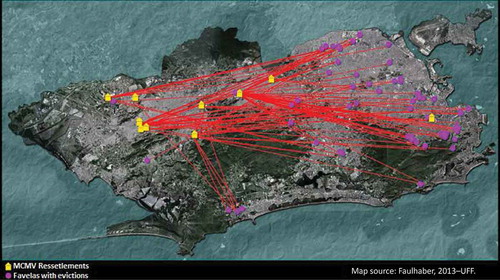

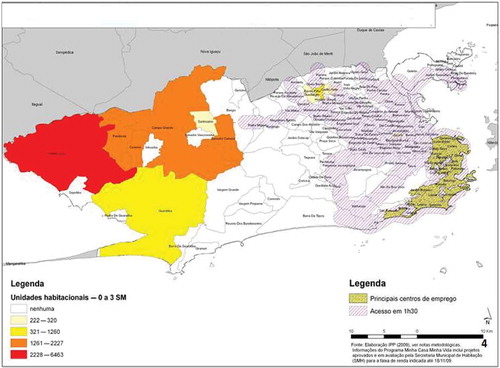

In terms of exceptional mega-event planning, an important national programme deserves attention. Minha Casa Minha Vida (My House, My Life) is a vast federal low-income housing programme, unprecedented in the country’s history in terms of dedicated funds and number of units. However, the programme has been plagued with problems, and is widely criticized for promoting the displacement of hundreds of thousands of poor residents to the far urban periphery, where public facilities and services are limited. The programme had a particular impact on Rio, where low-income people have long been distributed throughout the urban territory. While wealthy people are concentrated in certain urban sectors (central and southern areas as well as Barra da Tijuca), the poor have lived in the periphery, but also in central city slums, near major employment centres. Under the Minha Casa Minha Vida programme, poor families evicted from these central areas are resettled in housing projects in the far periphery (Faulhaber Citation2013; –).

Figure 4. Access to major employment centres in 1:30 hours and housing units of Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV/My House, My Life Housing Project) for 0–3 minimum wage.

Another emblematic example of the exceptional urbanism that marked Rio’s mega-events preparation is the polemical renovation of the Maracanã stadium and the transformation of its immediate vicinity. Symbol of Brazilian identity and of Rio’s popular culture, the mythical stadium, where the World Cup’s closing match and the Olympics opening and closing ceremonies will be held, had already undergone a costly (USD 250 million) renovation for the 2007 Pan American Games. However, FIFA required an in-depth reform that deeply altered the stadium’s architectonic qualities and spatial organization. Part of the renovation involves the creation of a brand exclusion zone around the Maracanã, backed by special federal legislation. While Brazilian law prohibits the sale of alcohol within a vast perimeter surrounding sporting stadia, this rule will be lifted during the World Cup, to allow for the sale of beer by its exclusive sponsor. Exceptional legislation adopted in sight of the coming mega-events will thus allow the establishment of an exclusive, monopolistic commercial territory, where the sale of products and the placement of advertisements from companies other than official event sponsors are prohibited. Traditional food-sellers will be banned from the area, where they have held the right to work for years, and where generations of families have enjoyed pre-game churrascos (barbecues). As Gusmão de Oliveira (Citation2013: 224) puts it, in these territories of exception, you will not be able to consume beer that is not Budweiser’s, soft drinks that are not Coca-Cola, sandwiches that are not McDonald’s or hygiene products that are not Johnson & Johnson’s.

Fans associations and members of the general public accused the FIFA of denaturing the Maracanã by drastically reducing the amount of available seating and forbidding the kinds of popular uses that had marked its history (Mascarenhas & Oliveira Citation2006; Prieto & Viana Citation2009; Mascarenhas et al. Citation2011). Social movements emerged to contest interventions threatening the integrity of the stadium as a material and immaterial heritage, and protest its transformation into a multi-use arena for concerts and spectacles. A series of judicial actions were taken against the state’s plan to privatize this beloved public institution, after spending more than half a billion dollars of tax payers money to bring up the stadium to FIFA standards. Conflicts also irrupted with regard to multiple evictions in the stadium’s vicinity, especially with respect to planned demolition of the Fredenreich municipal school, the Célio de Barros track-and-field stadium, the Julio Delamare aquatic park, and the historical building of the Museu do Indio (Aboriginal Museum), all of which were threatened with demolition to establish a safety perimeter and create vast parking lots around this exclusive shopping and sports entertainment centre.

In March 2013, Rio’s riot police brutally evicted dozens of indigenous squatters from the abandoned museum near the Maracanã (Sánchez 2013). Since 2006, native people from across Brazil had used the building as a safe haven when visiting Rio to study, sell crafts, or receive medical attention, renaming it Aldeia Maracanã (Maracanã Village). More than one-hundred unarmed protesters were dispersed by shock troops using pepper spray and tear gas. The eviction took place, symbolically, on the day of the revamped stadium’s inauguration. Few journalists could witness the demonstration and report on the subsequent clash with the police because they had been taken directly into the stadium in government vans and to be shown a demonstration of the stadium’s new light and sound capabilities. Maracanã was also at the heart of the June 2013 protest movement that rocked all of urban Brazil. Many actions denouncing the high social and economic price of hosting mega-events took place near the stadium during the Confederations Cup, an event which serves as a form of testing ground for next year’s World Cup. At the time of writing, in August 2013, all planned evictions and demolitions around the stadium had been halted.

Porto Maravilha: Rio de Janeiro’s port revitalization project

One particular Olympic project embodies the complex dynamics of mega-event-led regeneration, and exemplifies many aspects of the city of exception theory. Porto Maravilha, Rio’s port revitalization project, is unprecedented in the history of the city, both in its scope, affecting five inner-city districts, and by its cost, estimated at nearly USD 4 billion. It seeks to turn 5 km2 of devalued housing and industrial buildings into upscale office and residential towers, turning the old port area into a world-class mixed-use living, working, and entertainment district. Rio’s municipal government had long wanted to exploit the tourism potential of the derelict industrial port, but many previous plans dating back to the early 1980s had failed to see the day (Acioly Citation2001). It would take a rare political alignment at the national, state, and municipal level, as well as the opportunity presented by the two mega-events for the project to finally be launched.

Rio’s old port sector sits at the heart of the metropolitan area, directly north of the central business district. This vast area was of great economic, cultural, and political importance in the city’s history – as the centre of port and industrial activity, a hub in the colonial slave trade, the locus of numerous popular revolts and the birth place of many Afro-Brazilian cultural traditions such as samba and capoeira. However, Rio’s port area had suffered from severe economic decline and depopulation over many decades. In 1960, Rio de Janeiro lost its status as Brazil’s national capital and the transfer of government functions to Brasília deeply affected the local economic activity, leaving a number of Federal buildings vacant. Starting in the 1970s, de-industrialization reduced economic activity while containerization brought the transfer of the city’s remaining industrial port functions to more up-to-date facilities further down the bay. Middle-class flight to the city’s developing western suburbs in the 1980s accelerated the area’s depopulation and opened the door for squatting. Over the years, lack of public investment and a laissez faire attitude exacerbated urban degradation and the rise of marginality and violence (Acioly Citation2001). Throughout its history, the port area’s average income, education, and employment levels were substantially lower than in the rest of the city. Today, it still boasts one of the highest concentrations of squatting and homelessness in Rio.

The proposed revitalization project incorporates features commonly seen in paradigmatic examples of gentrified waterfront redevelopments around the world, including Barcelona’s Puerto Vell, Buenos Aires’s Puerto Madero, and Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. It seeks to create a new festive entertainment hub, with up-to-date tourist facilities and cultural amenities that will act as Rio’s new international face (Nu Citation2012). First-rate science and art museums, shopping malls, and a new cruise-ship terminal will anchor the project, while docks and warehouses will be converted for entertainment and consumption purposes. The project plans to quadruple the area’s present population of 25,000 and to increase the port capacity from 50,000 to 2 million passengers a year (Porto Maravilha Citation2011).

Although Rio’s port was not part of the original Olympic bid, once the city’s candidacy was secured, local authorities lobbied with the IOC to transfer Olympic functions to the port area (Bentes Citation2011; Nu Citation2012). While efforts to locate major facilities, including the Olympic Village in the district failed, the IOC reluctantly allowed a few minor Olympic projects to be built in the port, including a technical operations centre, to be converted into a hotel and convention centre, as well as a media village, to be sold as middle-class condominiums after the Olympics (Cidade Olímpica Citation2011). All aspects of Porto Maravilha, even those with no direct relation to the Games, will benefit from the added weight and authority conferred by the Olympic enterprise. By establishing itself as one of the great Olympic legacies to the city, Porto Maravilha has acquired a new symbolic significance and now capitalizes upon its association with the Olympic brand to help market the project (Ferreira Citation2010). The 2016 target date also fostered a sense of imminence and helped justify the haste with which many planning decisions were taken.

Porto Maravilha also represents the largest public-private-partnership (PPP) in Brazilian history. In 2009, the municipal government set up a corporation, the Port Urban Development Company (CDURP) to coordinate the project and court international investors. Much of the provision of public infrastructure was contracted out to a private consortium, the Concessionária Porto Novo, modelled after the Business Improvement Districts found in cities like London, New York, and Los Angeles. Made up of three of Brazil’s largest engineering and construction firms – Norberto Odebrecht Brasil, Carioca Christiani-Nielsen Engenharia, and OAS Ltd, this consortium signed a 15-year contract with CDURP, and will be responsible for managing the project, clearing the land and upgrading urban infrastructure, as well as providing basic services such as street lighting, drainage, and garbage collection in the district (Porto Maravilha Citation2011).

Porto Maravilha as an ‘exceptional’ Olympic project

The redevelopment process was facilitated by extraordinary political interventions, financial innovations, and legal decrees passed in exceptional circumstances, justified by the need to comply with promises made to the IOC in the original bid proposal, which became binding after the city’s candidacy was accepted. For example, the municipal decree that authorized the establishment of a public-private partnership with the Porto Novo consortium was passed within weeks of Rio winning its Olympic bid. Although the decision to grant the responsibility for the realization of public works, and the maintenance and provision of public services for an entire urban district to a single contractor was largely unprecedented in Brazil, the decree was adopted in an emergency fashion that failed to allow sufficient time for public scrutiny (Gusmão de Oliveira Citation2011). Other municipal laws, including those providing tax benefits to CDURP and businesses wishing to settle in the port area or to participate in its redevelopment, were adopted with similar urgency.

Evidence suggests cases of possible collusion, or at least intense collaboration, between the state and private enterprises in the reconfiguration of the legal framework that would allow Porto Maravilha’s realization. Entire sections of the municipal decrees that defined the structure of the PPP, described its financing make-up, determined its territorial limits, and suggested modifications to the Master Plan, appear to have been lifted from a private sector proposal submitted in 2009 regarding the redevelopment of the port area (Gusmão de Oliveira Citation2011). The three enterprises behind this proposal were Odebrecht, Carioca, and OAS Ltd, the same companies, which would be selected, in 2010, as the unique eligible contenders for the realization of Porto Maravilha, later incorporated as the Porto Novo consortium (Gusmão de Oliveira Citation2011). These companies are already greatly benefitting from the economic activity generated by the two mega-events, especially Odebrecht which is involved in the construction of several of the main stadia build throughout Brazil for these events.Footnote4

Another example of the exceptionalism that characterizes Porto Maravilha’s realization has to do with the Certificates of Additional Construction Potential (CEPAC), an innovative financial instrument adopted to finance the second phase of the project. A CEPAC is a permission to build beyond permitted limits in a specific area of the city. It is a title, regulated by the commission of real estate values (CVM), which can be traded on the stock exchange and subjected to speculation. CEPACs came into existence as part of the City Statute, a Federal law passed in 2001, and have been used in several occasions, especially in São Paulo, but they have been heavily criticized and denounced as a form of financialization of real estate speculation (Rolnik Citation2011).

One of the main goals of the CEPACs is to capture in advance the increased property value created by Olympic revitalization, so as to help finance necessary large-scale infrastructure projects. CEPACs also help raise the confidence and interest of potential investors in the project by lowering financial risks. With these titles in hand, private enterprises can build beyond the established limit and maximize land use to increase their profit margin. In Porto Maravilha, CEPACs represent the right to build above the six storeys (18 m) legal height limit, to up to 50 storeys. In June 2011, the city auctioned off 6.4 million CEPACs with a nominal value of USD 312 in a single lot for a total of USD 2 billion. The winner and only bidder in the auction was the FGTS (Fundo de Garantia por Tempo de Serviço), the government-run worker’s pension fund, which is controlled by the Caixa Econômica Federal, an important public banking institution. The FGTS’s profit from the sale of CEPACs to individual developers will be used to pay the Porto Novo consortium to carry out all urban operations in the port (Porto Maravilha Citation2011).

The FGTS thus is committed to fund the planned USD 4 billion in the infrastructure for Porto Maravilha, in addition to the USD 2 billion already paid to acquire the CEPACs. According to an analysis carried out by Jorgensen Citation(2011), under such conditions, a square metre of residential or office space in Porto Maravilha will have to sell for at least USD 5000 for a developer to make a profit, making it some of the most expensive real estate in Rio. It is therefore highly unlikely that any residential units within the price range of working class or even lower middle-class residents will be built in the area, with the majority being elite housing and luxury offices, thus making CEPACs a prime instrument of gentrification (Broudehoux Citation2013).

Porto Maravilha, extraterritoriality, and socio-spatial polarization

The highly speculative nature of Porto Maravilha is causing concern for socio-spatial segregation and the creation of an extraterritorial enclave in which the poor have no right or place. The success of the project relies upon the potential for this devalued part of town to become prime real estate, which is contingent on a drastic alteration of the area’s socio-economic make-up. The port area is populated by mostly poor, working-class residents, 51% of whom were renters in 2002 (Galiza Citation2011). In Brazil, the proximity of poverty is one of the main sources of real estate devaluation. In upscale neighbourhoods of Rio de Janeiro, the simple view of a favela (informal settlement) can justify a 50% price difference between units in the same building. It is clear that this situation is not conducive to the valuation of market shares and that, in order for the Caixa Econômica to recoup its investment and attract benefits, many poor families will have to be relocated from sectors where CEPACs are sold (Freeman Citation2012).

In Porto Maravilha, gentrification and social exclusion will not be the accidental by-products of an urban renewal led by the market’s invisible hand, but represent necessary conditions for market-led urban redevelopment and property speculation. Original plans had promised the construction of 20,000 low-rent units in the area, accessible for families earning the equivalent of five times the minimum wage (which is above the paying capacity of most current residents, who earn no more than three times the minimum wage). However, subsequent plans later reduced the planned amount of social housing to 500 units, to be located on the western periphery of the project, near the Central do Brasil railway station, where land is cheap and social housing is less likely to devalue prime CEPAC redevelopment sites (Galiza Citation2011). At the time of writing, in August 2013, Eduardo Paes had recently admitted that the CEPACs would privilege commercial use over residential use. It thus remains unclear how much housing, either high-end or low-end, will actually be produced.

From a financial point of view, the best scenario for the project would be the complete relocation of lower income residents to outside the Porto Maravilha area (Jorgensen Citation2011). Already, at the end of 2011, approximately 5000 families had been removed (Galiza Citation2011). Many were squatters, who had taken possession of vacant office buildings owned by the Federal government, undertaken major repairs and were engaged in extensive negotiations to gain ownership, thereby creatively contributing to the alleviation of the city’s dismal housing shortage.

A major risk factor for the project is Morro da Providência, a prominent favela housing 5000 inhabitants on a hill looming over the vast real estate project. This 115-year-old informal settlement, the earliest in the city and first to bear the name ‘favela’ has housed generations of port workers. Long ostracized for reasons of racial prejudice, it was further marginalized by the arrival of violent drug gangs in the 1980s. Although Providência’s presence at the heart of Porto Maravilha is clearly problematic, the community’s wholesale relocation is politically unfeasible.

Under the combined effect of various interventions, Providência will be symbolically tamed, trimmed, and turned into a tourist attraction. This drastic makeover is key to understanding the financial potential of the CEPACs and the success of Porto Maravilha as an extraterritorial enclave. The construction of diverse infrastructure will displace many residents and reduce the size of the settlement. Multiple cosmetic interventions and the establishment of a permanent police pacification unit will also neutralize the favela’s negative image and make it less threatening (Freeman Citation2012).

A major intervention in Providência’s touristification was the construction of a cable car system, completed in 2013, which connects residents to public transportation networks while helping tourists benefit from magnificent views of the harbour. The cable car will connect Providência to Rio’s main rail station and significantly, to Samba City, a popular tourist attraction and entertainment venue. Inspired by Medellín’s Metrocable system, the construction of this cable car will require the relocation of dozens of families. Its main station occupies the site of Praça Américo Blum, Providência’s main square, obliterating a cherished community space. More families will be removed for the construction of a funicular leading to Cruzeiro, the oldest and uppermost portion of the community, crowned by an emblematic nineteenth-century chapel. There, consolidated houses will be removed to make way for an open-air museum built in an anachronistic colonial style.

An estimated total of 749 families, or approximately one-third of the community, is threatened by port-related interventions, under the cover of the state-sponsored favela upgrading programme Morar Carioca. It is unlikely that these residents will be rehoused in this same neighbourhood, since the Federal programme Minha Casa Minha Vida, responsible for rehousing evictees, only plans to build 2% of relocation homes in or near Providência (Galiza Citation2011).

Repeated visits by the authors to the favela during between 2010 and 2013 reveal that the community’s initial optimistic expectations for Porto Maravilha, in terms of job creation in the construction and service sectors, were quickly replaced by sentiments of fear and resentment. People complain that these multi-million dollar projects do not address the most important issues facing their community, in terms of sanitation, education, and healthcare. Many claim to have little use for a cable car about which they were never consulted and which they view as a dubious transportation improvement; proof that national and international tourism development supersedes local needs. Residents feel they are being wilfully expelled from the area in order to serve the interests of mega-events stakeholders.

Resisting Porto Maravilha

In Providência, like elsewhere in Rio where event-related interventions are threatening local communities, residents complain about what they see as a total lack of information, dialogue, and transparency, and a blatant disrespect for local history. Local activists criticize the construction of expensive, image-driven cultural projects as part of Porto Maravilha, while more urgent needs should be prioritized, especially in terms of education, health, and the fight against poverty (Barbosa & Ossowicki Citation2009).

Many have mobilized to fight unjustified evictions and housing rights violations. But they are fighting an uphill battle in taking on mega-events. Local resistance to the neo-liberal reconfiguration of the city and to the violent dislocation of the poor has been weakened by several factors. The very essence of mega-events as global spectacle has hindered the organization of efficient resistance. Their symbolic appeal, their powerful status as high visibility media magnets and their strong consensual power promote the disavowal of their social consequences and discourage attacks and criticism (Broudehoux Citation2013).

The lack of transparency of the project implementation process, especially the heavily bureaucratic and individualized housing relocation process, is another major impediment to the development of efficient resistance movements. It often takes weeks for people whose house is marked for demolition to obtain details about the conditions of their relocation. Individual households eventually receive an appointment at the municipal housing bureau where they are informed of their compensation options. They are offered the choice of a lump sum (around USD 10,000, well below the market value of any local home), or of a replacement unit (likely located in a western suburb, far from their community), and of receiving a monthly rent allocation (USD 200) to find temporary lodging until their new unit is delivered (which can take months). By individualizing the negotiation process, keeping residents in the dark as to the specifics of the project, and scattering displaced residents around the territory, authorities have managed to limit collective action and to accelerate project implementation (Broudehoux Citation2013).

Resistance movements are also hindered by the fragmentation of interests among community members and by the fact that urban interventions do not have a uniform impact upon different households. In Providência, many short-time residents (newcomers to the favela who are mostly renters) expressed satisfaction at the idea of receiving a cash compensation for their lost home. However, for long-term dwellers, especially homeowners with stronger community ties and deep emotional attachment to place, the enforced relocation is often traumatic. Demolition does not only signify the loss of a valuable, lifelong investment, but it also represents the severance of important social networks, and the uprooting from a familiar environment, with easy access to essential services, sources of employment, and education opportunities (Broudehoux Citation2013).

The mixed success of popular resistance to urban regeneration is evident in the glut of event-related projects launched throughout the city, and the growing number of protest movements competing for media and state attention. In Providência, a series of well-organized protests, with clever slogans and powerful images, succeeded in attracting media attention and convinced authorities to postpone demolition and make concessions about the project implementation process.

Citizens have also tried joining forces with other community groups to increase their visibility and leverage. Many have joined the Fórum Comunitário do Porto (Port Community Forum), an alliance of residents, scholars, activists, and community leaders created in January 2011 to fight for the rights of residents of the entire port area. Others are members of the Comitê Popular da Copa e das Olimpíadas (People’s Committee for the Cup and the Olympics), a vast coalition fighting to limit the negative social impacts of mega-events. But here again, individual causes too often get lost among the multiplicity of issues defended by these coalitions.

Conclusion: rethinking state of emergency planning

The story of Porto Maravilha testifies the rise of a new, exceptional form of a neo-liberal urbanism in the Latin American landscape. It is an exceptionalism marked by the accelerated demise of a planning vision in the service of the public interest, to be replaced by a competitive, entrepreneurial, and economistic conceptualization of the city; characterized by privatization and the search for revenue generation. No longer geared towards meeting the basic needs of the population, this event-led planning vision is characterized by authoritarianism, legislative flexibility, and disregard for civic rights. This form of planning in a ‘state of emergency’ has inscribed new forms of power relations in the urban landscape, giving extraordinary powers to non-elected actors to transform the urban environment. Through the vehicle of PPPs, private interests and aspirations were allowed to dictate the nature, location, and end users of major urban projects and to transform the urban realm into a marketable commodity.

Porto Maravilha also marks the rise of a new, aggressive, state-sponsored form of gentrification, where government incentives help make it both safe and attractive for speculators to appropriate new urban territories, and benefit from unlocked land values. It embodies a revanchist urban vision that is socially, economically, and spatially exclusive, and whose policies both victimize and discriminate against those who are not valued as deserving members of society. In fact, Porto Maravilha is taking neo-liberal regeneration to an entirely new level, so much so that even Barcelona planners, who had so eagerly exported their model to Brazil and convinced local planners and authorities to adopt their vision, find that things are going too far. They insist in their model that the market should serve the city, not the opposite (Ferreira Citation2010).

Post-script: final notes on June 2013 events

The June 2013 events have already become key markers in the timeline of the history of both Rio and Brazil. Over a 2-week period, which coincided with the FIFA’s Confederations Cup held in several Brazilian cities, the entire country was shaken by social conflicts on a scale rarely seen in the last 20 years. In Rio de Janeiro, where mobilization was the strongest, more than 100,000 protesters took to the streets on June 17, and 3 days later at least five times more people descended upon the city centre. On June 20, demonstrations in nearly 400 cities, large, medium, and small throughout Brazil mobilized millions, demanding the immediate overturn of the recent increase in public transportation fare. Over the next days, the protests intensified in reaction to violent police repression, attracting a wider socio-economic make-up and embracing a broader agenda (Badaró Forthcoming Citation2013). Demands not only focused on public transportation, education, health, and housing, but also called for a radical transformation of Brazilian society and a deep reform of the exercise of political power.

The issue of public spending on sporting events figured prominently on the agenda of many demonstrations, especially in cities hosting the 2014 World Cup. Demonstrators denounced the arrogance and brutality of ruling political coalitions, especially members of those with events-related interests, including media agencies, large national corporations, real estate speculators, and a host of international businesses with close links to the FIFA and the IOC. According to Vainer (2013), it was their blindness, pretension, and violence that brought together in collective action, hundreds of thousands of hitherto un-politicized youth. International media headlines for June 20 corroborated this reading of events. The Guardian wrote: ‘Brasilians take the streets of major cities to demand better public services and protest the wasteful spending on sporting events’ (The Guardian 2013).

It is likely that the work accomplished, in the previous 2 years, by the Comitê Popular da Copa e das Olimpíadas (People’s Committee for the Cup and the Olympics) played a significant part in raising public awareness to the public policy problems posed by mega-events. This organization had condemned shady deals in the construction of World Cup stadia, unjustified evictions and the controversial demolition of cherished institutions near the Maracanã, all of which entered the public debate and were widely featured in slogans and on posters during the protests.

Participants in this ‘Vinegar Revolution’ demonstrated a clear understanding of the issues at stake with relations to the hosting of mega-events. Many of the slogans heard on the streets creatively merged social demands, criticism of the coming sporting events and complaints about Rio’s city branding initiatives, symbolically challenging the consensus that had hitherto prevailed. ‘We want FIFA-standard public schools’ ‘Call me a stadium and invests in me’, ‘How many schools are worth one Maracanã?’ Other ingenious acts of resistance used large screen projections to question the objectivity of the mainstream media and denounce the close relationship between Globo TV, Brazil’s the largest television network, and the current government.

Ironically, power holders appear to have been totally unprepared for such popular backlash against their greed and excess. Neither political leaders nor the FIFA knew how to regain control on this political crisis. State attempts to dampen the movement by revoking the bus fare hike had the opposite effect, convincing people that staying on the street would allow them to achieve what had seemed impossible the day before. ‘If you have any claims or protest, go to the streets and demonstrate’; ‘We want this and we want more’ were the new slogans.

What came out of the crisis was an incredibly rich and eloquent form of symbolic resistance, which used highly strategic and evocative territories as locales for the expression of discontent: it was around major stadia, in front of emblematic infrastructure and near establishments of power that people came to voice their grievances with the system. And those grievances were voiced in a way that made clear that the people had not been duped by the mega-event spectacle, and would no longer tolerate to see their cities being sold to private corporations.

The ‘pacified city’ is a notion associated with the myth of the ‘safe city’ – devoid of conflict and contradictions – which stands as the idealized model for the perfect Olympic city. In this context, Rio’s leaders have relied upon a pacifying narrative in their construction of the city’s new world image: we are modernizing Rio, it says, getting ready to host the world, and the future! But even with the state’s control of the city’s rebel territories, the expulsion of their undesirable residents, and the implementation of a complex security apparatus, the idea of the urbe pacificada is now under serious threat. Displaced and militarized communities, whose territory was being looted by handful of enterprises, are now re-awaking the spirit of the old Maracanã. Denunciations and accusations of civil rights abuses from citizens who endured the violent repression of the protest movement are multiplying. Even after the closing of the Confederations Cup, contestation continues unabated. The ever growing multitude on the streets revealed the fragility of a system that long appeared all-powerful and invulnerable, and which is now swaying in the face of peaceful contestation and in the light of the revelations of its abusive practices.

Rio’s city centre and affluent neighbourhoods of the South Zone, like Leblon where the State Governor resides, or Laranjeiras, where the Governor’s Palace is located, have been the scene of many demonstrations. Their residents have witnessed the effect of the state police’s pacifying tactics and had the opportunity to experience the dark (and usually hidden) side of the ‘pacification’ of poor communities, which has little to do with the idyllic image broadcasted on national television. They have also realized the way mainstream media manipulates information to blame groups of hooded provocateurs, window smashers and other troublemakers, in contrast with the generally peaceful demonstrations experienced on the streets. In Vainer (2013)’s words, they have learned that pacification is ‘the order given by the occupying force, which transforms everyone, indiscriminately, into a suspect: suspect, in the favela, of drug trafficking, or suspect, on city streets, of vandalism’.

As discussed throughout this article, it is in a state of emergency that Rio de Janeiro has been planned and renovated in recent years. A state of emergency which was aggravated after winning the dubious privilege of hosting the World Cup and the Olympics. There are moments in history when the days feel like years. It can be said that Brazil’s recent social upheaval has allowed demonstrators to experience, in real time, a situation akin to Henri Lefebvre’s notion of ‘experimental utopia’. The outcome of this powerful wave of demonstrations remains uncertain. But it appears that the political landscape of mega-event planning may never be the same.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Geographer Vitor Hugo Teixeira for the production of maps and figures.

Notes

1. 1. Many of these scholars participated in the 2010 International Conference on Mega-Events and the City, organized by the members of both research laboratories and held at the Fluminense Federal University in Niterói.

2. 2. Nelma Gusmão de Oliveira Citation(2013) sees a strong convergence between the authoritarian character of neo-liberal planning practices and the production of mega-events, marked by the direct inference of executive powers in the act of legislation. For her, one of the great dangers of strategic planning, especially in the context of the Olympic state of emergency, lies in its depoliticizing power that can lead to a form of authoritarianism. In her view, the vast adoption of strategic planning, an approach that rests upon the construction and consolidation of consensus, has led to the gradual disappearance of the political – or the political fight for the right to be heard – in favour of the consensual. The essence of consensus is not peaceful discussion, democratic negotiation, and reasonable agreement (as opposed to conflict and violence), but the elimination of dissent. For Vainer (Citation2009), entrepreneurial planning results in a radical negation of political space, no solely in the dis-partition of the rigid separation between public and private sectors that had been announced by Castells and Borja Citation(1996) but as the submission of public interest to the private.

3. 3. Its construction was funded by the Worker’s Support Fund (FAT), which is managed by the Caixa Econômica Federal (CEF), a Brazilian public bank.

4. 4. Odebrecht is responsible for the construction of 4 of the 12 FIFA stadia in Brazil, (in Rio, Sao Paulo, Salvador, and Recife). Apart from its involvement in the first and second phases of Porto Maravilha, Odebrecht is also responsible for the refurbishing of Maracanã stadium, as well as the construction of the city’s new BRT system.

References

- Acioly C. 2001 . Reviewing urban revitalisation strategies in Rio de Janeiro: from urban project to urban management approaches . Geoforum . 32 (4 ):501 –530 .

- Agamben G. 2005. State of exception. Chicago, IL:: University of Chicago Press.

- Alegi P. 2008. A nation to be reckoned with: the politics of world cup stadium construction in Cape Town and Durban, South Africa. Afr Stud. 67(3):397–422.

- Andranovich G, Burbank MJ, Heying CH. 2001. Olympic cities: lessons learned from mega-event politics. J Urban Affairs. 23(2):113–131.

- Arantes O. 2009. Uma estratégia fatal. A cultural nas novas gestoes urbanas. In: Arantes O, Vainer C, Maricato E , editors. A cidade do pensamento unico: Desmachando consensus. Petrópolis: Vozes ; p. 11–74.

- Badaró MB. Forthcoming 2013. A multidão nas ruas: construir a saída para a crise política [The multitude on the streets: Building an exit for a political crisis]. History Department, Federal Fluminense University.

- Barbosa AA, Ossowicki TM. 2009. Revitalização do Porto, IPHAN e políticas culturais no Morro da Conceição [Internet]. Minha cidade, 108: 02 [cited 2013 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/minhacidade/09.108/1842

- Bentes J. 2011. Perspectivas de Transformação da Região Portuária do Rio de Janeiro e a Habitação de Interesse Social. Paper presented at: 14th annual meeting of the National Association of Researchers in Urban and Regional Planning (ANPUR); Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Bienenstein G. 2001. Globalização e Metrópole: a relação entre as escalas global e local: o Rio de Janeiro. Proceedings of the 9th annual meeting of the National Association of Researchers in Urban and Regional Planning (ANPUR); Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Broudehoux AM. 2001. Image making, city marketing and the aesthetization of social inequality in Rio de Janeiro. In: Alsayyad N, editor. Consuming tradition, manufacturing heritage: global norms and urban forms in the age of tourism. London: Routledge ; p. 273–297 .

- Broudehoux AM. 2007. Spectacular Beijing: the conspicuous construction of an Olympic metropolis. J Urban Affairs. 29(4):383–399.

- Broudehoux AM. 2013. Sporting mega-events and urban regeneration: planning in a state of emergency. In: Leary ME, McCarthy J, editors. The Routledge companion to urban regeneration. London: Routledge.

- Burbank M, Andranovich G, Heying CH. 2001. Olympic dreams: the impact of mega-events on local politics. Boulder: Lynne Rienner (CO).

- Castells M, Borja J. 1996. As cidades como atores políticos. Novos Estudos. 45:152–166.

- Chalkey BS, Essex SJ. 1999. Urban development through hosting international events: a history of the Olympic Games. Plann Perspect. 14(4):369–394.

- Cidade Olímpica. 2011. Porto Olímpico, futura referência em habitação de qualidade. [Internet]. [cited 2012 Mar 21]. Available from: http://www.cidadeolimpica.com/porto-olimpico-sera-referencia-em-habitacao-de-qualidade/

- Essex S, Chalkley B. 2004. Mega-sporting events in urban and regional policy: a history of the Winter Olympics. Plann Perspect. 19(2):201–232.

- Faulhaber L. 2013. Rio Maravilha: práticas, projetos e intervenções no território. Niterói: EAU [monograph work], Federal Fluminense University .

- Ferreira A. 2010. O Projeto ‘Porto Maravilha’ No Rio De Janeiro: Inspiração ee Barcelona e Produção a Serviço do Capital? Revista Bibliográfica de Geografía Y Ciencias Sociales. 15, 895:20.

- Freeman J. 2012. Neoliberal accumulation strategies and the visible hand of police pacification in Rio de Janeiro. Revista de Estudos Universitários. 38(1):95–126.

- Gaffney C. 2010. Mega-events and socio-spatial dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919–2016. J Latin Am Geogr. 9(1):7–29.

- Gaffney C, Sanchez F, Bienenstein G, Gomes T. 2012. The river in transition: transportation discourse and impacts in Rio de Janeiro. Paper presented at: International Congress. Latin American Studies Association; San Francisco (CA), USA.

- Galiza H. 2011. Politique de logement sociaux au Brésil: Le projet de rénovation Porto Maravilha à Rio de Janeiro. Paper presented at: Centre d’études et de recherches sur le Brésil, Montreal, Canada.

- Gold J, Gold M. 2011. Olympic cities: urban planning, city agendas and the world’s games, 1896 to the present. London: Routledge.

- Greene SJ. 2003. Staged cities: mega-events, slum clearance and global capital. Yale Human Rights Dev Law J. 6:161–187.

- The Guardian. 2013. [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jun 18]. Available from: http://m.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jun/18/brazil-protests-erupt-huge-scale#comments

- Gusmão de Oliveira N. 2011. Força-de-lei: rupturas e realinhamentos institucionais na busca do ‘sonho olímpico’ carioca. Paper presented at: 14th annual meeting of the National Association of Researchers in Urban and Regional Planning (ANPUR); Rio de Janeiro.

- Gusmão de Oliveira N. 2013. O Poder Dos Jogos e Os Jogos De Poder: Os Interesses Em Campo Na Produção De Uma Cidade Para O Espetáculo Esportivo [dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: IPPUR, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

- Harvey D. 1989. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late Capitalism. Geografiska Annaler. 71:3–17.

- Hayes G, Horne J. 2011. Sustainable development: shock and awe? London 2012 and Civil society. Sociology. 45(5):749–764.

- Hiller HH. 2000. Towards an urban sociology of mega-events. Res Urban Sociol. 5:181–205.

- Hiller HH. 2006. Post-event outcomes and the post-modern turn: the Olympics and urban transformations. Eur Sport Manage Q. 6(4):317–332.

- Hiller HH. 2012. Host cities and the Olympics: an interactionist approach. London: Routledge.

- Horne J, Manzenreiter W. 2006. Sports mega-events. Social scientific analyses of a global phenomenon. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Jorgensen P. 2011. Tentando entender a Operação Urbana Porto do Rio’ Online posting [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jun 19]. Available from: http://abeiradourbanismo.blogspot.com/2011/10/tentando-entender-operacao-urbana-porto.html

- Judd D. 2003. The infrastructure of play: building the tourist city. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- Klein N. 2007. The shock doctrine: the rise of disaster capitalism. Toronto: Knopf.

- Lenskyj HJ. 2000. Inside the Olympic industry: power, politics, and activism. Albany (NY): State University of New York Press.

- Lenskyj HJ. 2008. Olympic industry resistance: challenging Olympic power and propaganda. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Lima PN, Jr. 2010. Uma estratégia chamada ‘planejamento estratégico’. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras.

- Mabin A. 2010. Thinking the complexities of Mega-events in cities, 2010 and after. Paper presented at: International conference on Mega-events and the city. Federal Fluminense University; Niterói, Brazil.

- Martins da Cruz MC. 2010. Do Mississipi Carioca ao Estádio Voador. Forjando espaços de legitimação na indiferença [thesis]. Niterói: Federal Fluminense University.

- Mascarenhas G, Bienenstein G, Sánchez F. 2011. O Jogo Continua. Megaeventos e Cidades. Rio de Janeiro: Press of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (EDUERJ).

- Mascarenhas G, de Oliveira LD. 2006. Adeus Ao Proletariado?: a Dimensão Simbólica do Estádio da Cidadania. Lecturas, Educación Física y Deportes [Internet] [cited 2013 Jun 19]; p. 101. Available from: http://www.efdeportes.com/efd101/estadio.htm

- Miles S, Miles M. 2004. Consuming cities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nu J. 2012. From Zona Portuaria to Porto Maravilha: the transnational dimensions of urban redevelopment in Rio de Janeiro. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers; New York, USA.

- Oliveira A. 2009. O emprego, a economia e a transparência nos grandes projetos urbanos. Paper presented at: Globalização, Políticas territoriais, Meio Ambiente e Conflitos sociais [Globalization, Territorial Policies, the Environment, and Social Conflicts]. Second Meeting of the ETTERN-IPPUR-UFRJ on; Vassouras, Brazil.

- Oliveira F, Lima PN, Jr, Sánchez F, Bienenstein G. 2007. Grandes projetos urbanos: panorama da experiência brasileira. Proceedings of the 9th annual meeting of the National Association of Researchers in Urban and Regional Planning (ANPUR); Belém, Brasil.

- Oliveira FL. 2003. Competitividade e pragmatismo no Rio de Janeiro: a difusão de novas práticas de planejamento e gestão das cidades na virada do século [dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: IPPUR, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

- Oliveira FL. 2013. Urban Politics and Olympic Games in Rio. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers; Los Angeles (CA), USA.

- Peck J, Tickell A. 2002. Neoliberalizing space. Antipodes. 34(3):380–404.

- Porto Maravilha. 2011. Official website [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.portomaravilha.com.br

- Prieto G, Viana J. 2009. Há-Há Hu-Hu O Maraca é Nosso: Uma Análise Do Espaço Público e das Territorialidades do Estádio Jornalista Mário Filho (Maracanã). Neue Romania. 39:95–105.

- Rolnik R. 2011. Porto Maravilha: custos públicos e benefícios privados? [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jun 19]. Available from: http://raquelrolnik.wordpress.com/

- Sánchez F. 2010. A Reinvenção das Cidades para um Mercado Mundial. 2nd ed. Chapecó: Argos, UNOChapecó.

- Sánchez F. 2013. Aldeia Maracanã: é assim que se faz uma Copa? Brasil de Fato [cited 22 July 2013]. Available from: http://www.brasildefato.com.br/

- Sánchez F, Bienenstein G. 2009. Jogos Pan-Americanos Rio 2007: Um Balanço Multidimensional. Paper presented at: International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Santos M. 2001. Por uma outra Globalização. São Paulo: Record.

- Short J. 2008. Globalization, cities and the summer Olympics. City. 12(3):321–340.

- Smith A. 2005. Reimaging the city: the value of sport initiatives. Ann Tour Res. 32(1):217–236.

- Smith N. 2012. New globalism, new urbanism: gentrification as global urban strategy. Antipode. 34:427–450.