Abstract

The complexities and uncertainties inherent to climate change place ecosystems and governance systems under pressure, in particular at the local level, where the causes and consequences of climate change play out. To address this complexity, local authorities have to be flexible, with an emphasis on learning and experimentation to lower greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the challenges climate change poses – hence, they have to become learning organisations. Examining Malmö, this paper explores whether it has the characteristics to embrace and institutionalise learning and how this affects the development of its climate policies. The analysis finds several elements invaluable for Malmö’s innovative climate policies: climate strategies are incorporated within the city’s long-term vision to become a sustainable city: socially, economically and environmentally; dialogue and learning are emphasised throughout the process; and all stakeholders are involved, including external partners, leading to integrated approaches.

1. Introduction

While actions are needed at various levels to address climate change, urban areas are crucial. For the first time in history, more than 50% of humanity resides in urban areas, altering the relationship between humans and nature: modern cities are defined by a concentration of economic activity, infrastructure and intensive human interaction (United Nations Population Fund Citation2007). Despite benefits, urban areas constitute 40–70% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (International Energy Agency Citation2008; UN-Habitat Citation2011).Footnote1 Cities, however, not only generate emissions, but also strategies to mitigate climate change via policies, technical investments and communication (Kern & Alber Citation2008; Hoornweg et al. Citation2011; UN-Habitat Citation2011). In fact, per capita emissions of many cities are lower than the national average (Dodman Citation2009; Liu et al. Citation2012).

While mitigation has long been on the research and policy agenda, emission reduction strategies have not unfolded quickly enough; adaptation to the short- and long-term vulnerabilities of climate change thus becomes a necessary complement to mitigation (McEvoy et al. Citation2006; Martens et al. Citation2009; McEvoy et al. Citation2010; UN-Habitat Citation2011). While mitigation and adaptation strategies differ in terms of spatial and temporal scales and institutional contexts, it is increasingly recognised that integrated mitigation-adaptation strategies, taking vulnerability and a long-term sustainable development perspective into account, will be required (Klein et al. Citation2007; Wilbanks & Sathaye Citation2007; Martens et al. Citation2009). This is all the more relevant in cities, which both contribute to climate change and are already vulnerable to the consequences. Cities include wide expanses of non-porous surfaces, exacerbating flood risk and urban heat island. Moreover, extreme weather events can lead to temporary or prolonged urban resource demands (e.g. energy and water), weaken urban infrastructural networks or endanger historic architecture (Carter Citation2011; UN-Habitat Citation2011; da Silva et al. Citation2012). Within cities, integrative climate policies, planning and design strategies can facilitate more efficient use of urban services and natural resources, while addressing vulnerability and improving quality of life (e.g. air quality, reduced travel time) (Klein et al. Citation2007; Martens et al. Citation2009; Carter Citation2011; McCormick et al. Citation2013).

Although local authorities are not the only actor(s) to consider in urban climate governance, they remain significant (Bulkeley & Castán-Broto Citation2013, UN-Habitat Citation2011; Kern & Mol Citation2013; McCormick et al. Citation2013). They are, at least traditionally, responsible for coordinating urban planning and design, transportation, building and construction – all relevant sectors for mitigation and adaptation (Wilson & Piper Citation2010; McCormick et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, the response capacity and ensuing policies to address climate change depend on specific local conditions and organisational elements (Tompkins & Adger Citation2005; Burch Citation2010). Due to multiple complexities and uncertainties, addressing urban climate challenges is not the unfolding of a one-time implementation plan; rather, urban climate policies need to be adaptive and flexible (McEvoy et al. Citation2010). Local authorities must tackle the interdependencies and interactions between different actors and actions, adopting an institutionalised ability to continuously learn and change with respect to climate change – they have to become learning organisations (Senge Citation1990). A focus on learning can support urban climate governance and the adoption and implementation of urban climate policies.Footnote2 Learning thus serves as a focal element in this paper.

This paper investigates if a particular local authority reflects the characteristics of learning organisations (Senge Citation1990) and if so, how this facilitates an adaptiveFootnote3 climate policy. To explore the value of learning organisations in urban climate governance, an in-depth analysis was conducted of a city regarded as a sustainability forerunner: Malmö, Sweden (recognised by European Commission’s 2012 RegioStars Award for integrated sustainable development strategies, Idébanken’s 2011 prize for long-term efforts to become a sustainable city, WWF’s 2011 Earth Hour Capital, etc.Footnote4). In addition to its achievements, Malmö has faced struggles. Previously an industrial city, Malmö suffered an economic collapse in the late 1980s. This crisis provided city leaders with an opportunity to redirect Malmö’s identity and policies, learning to adapt from industrial development to sustainable development. Malmö’s organisational structure and relevant climate policies are investigated through an analysis of policy documents, grey literature, participatory observation (e.g. participation in internal, cross-departmental and partner meetings, conferences and workshops)Footnote5 as well as 10 interviews conducted with representatives from the Environment Department, City Planning Office, City Hall and the Streets and Parks Department. The analysis of a single case study is limited when it comes to generalisable results, but has the advantage that it can be conducted in much detail (Yin Citation2009). Studying a forerunner is also relevant from a policy perspective (Flyvbjerg Citation2004). Other cities may learn how Malmö, adopting the structure of a learning organisation, is able to cope with the uncertainties and complexities of climate change.

This paper is divided into four sections. Section 2 applies Learning Organisation Theory to develop a conceptual framework for adaptive climate governance of local authorities. Section 3 investigates to what extent Malmö’s local authority has adopted the characteristics of a learning organisation concerning the development and implementation of its climate policies. Main findings are discussed in Section 4.

2. Addressing climate change at the local level through learning

Local authorities have long been called upon to modify their structure, competencies and responsibilities to provide services and address challenges (Wollmann Citation2004). In the 1980s, New Public Management (NPM) attempted to modernise the public sector along three lines: lean government, introduce private-sector management principles and enhance innovation and flexibility of local leadership (Wollmann Citation2004).Footnote6 NPM has faced criticism concerning its emphasis on market rules, reducing local governments’ ability to regulate (Rose & Ståhlberg Citation2005; Katusiimeh et al. Citation2012). Meanwhile, local authorities moved from a regulatory/service provision role to an enabling role (Rose & Ståhlberg Citation2005; Betsill & Bulkeley Citation2006; Bulkeley & Castán-Broto Citation2013). A second phenomenon is a general trend towards decentralisation of authority in EuropeFootnote7 – in particular in Scandinavia – providing local institutions with increasing responsibilities, expanding participatory rights, while enhancing public accountability (Wollmann Citation2004). Past reforms altered local authorities’ roles and responsibilities (Lidström Citation2011). In the process, they facilitated a more strategic governing role, preparing local authorities to learn to adapt to coming challenges, including climate change.

Senge (Citation1990) refers to organisations where new ideas are encouraged to develop, where employees and the whole organisation are continually learning, as learning organisations. Learning organisations are assumed to be better able to address complex challenges with high uncertainty, especially situations where adaptive capacity and flexibility are required to turn incoming information into appropriate strategies. Learning organisations and organisational learning received significant attention in the 1990s, notably in literature on management and organisation (Örtenblad Citation2002; Yeo Citation2005; Rowley & Gibbs Citation2008). Debates on the wider applicability of these concepts are ongoing, also with regard to local authorities and environmental governance (Siebenhüner & Arnold Citation2007; Siebenhüner Citation2008; Dieleman Citation2013). The difference between learning organisations and organisational learning is most commonly referred to as the former being an end, the latter being a means (Armstrong & Foley Citation2003). Learning organisation literature focuses on identifying characteristics that facilitate an organisation to learn, thus serving as an organisational form. Scholars who address organisational (and social) learning examine how learning develops within an organisation (Hinkel et al. Citation2009, Tàbara et al. Citation2010). They pay attention to the learning process (Örtenblad Citation2002; Folke et al. Citation2005; Yeo Citation2005; Nilsson & Gerger-Swartling Citation2009).

This paper focuses on learning organisations, using Senge’s conceptualisation of learning organisations as its starting point. While originally applied to management and organisation studies, it is applicable to studies on public administration and elected officials (Senge Citation1990). Despite criticism of Senge’s demarcation of learning organisations (Örtenblad Citation2002, Citation2007; Rowley & Gibbs Citation2008), his work The Fifth Discipline is used as a starting point, since both academics and professionals most commonly refer to it when discussing learning organisations (Yeo Citation2005; Örtenblad Citation2007). Senge’s approach provides a framework to examine urban climate governance factors, stressing learning within a local authority.

For Senge, there are five disciplines – or conditions (Örtenblad Citation2002) – for creating a learning organisation: personal mastery, mental models, team learning, building a shared vision and systems thinking. The first four disciplines serve as antecedents of the fifth, systems thinking, thereby demonstrating their interconnectedness. According to Senge (Citation1990, p. 12) ‘the five disciplines develop as an ensemble.’ He identifies three levels of learning: individual, team and organisational (Senge Citation1990; Yeo Citation2005). We refer to these as the individual, internal and external dimensions of learning within the local authority. Concerning the individual dimension, personal mastery includes personal commitment to learning, notably among those in leadership. In urban climate governance literature, leadership is equally stressed (Kingdon Citation1995; Bulkeley Citation2010; McCormick et al. Citation2013). Concerning the internal dimensions (within an organisation), mental models establish beliefs and principles which grant meaning; team learning includes dialogue, training and goal setting. In urban climate governance, internal communication and organisational capacity are emphasised (Klein et al. Citation2007; Rogers Citation2009). Concerning the external dimension, when individuals and organisations build a shared vision, they become aware of expectations and find direction. Finally, systems thinking enables persons and organisations to examine a problem in its full setting. In our case, this refers to how a local authority functions within a multi-actor and multilevel system. In urban climate governance, scholars emphasise communication and participation with citizens and stakeholders, as well as horizontal and vertical collaborations with other cities and government levels (Kern & Bulkeley Citation2009; Bulkeley & Castán-Broto Citation2013). When learning occurs at all levels, or dimensions, this is referred to as systemic learning, which is what an organisation should strive for (Yeo Citation2005). Senge’s conceptualisation, while not an exact fit, aligns with relevant factors in urban climate governance literature (Rogers Citation2009; Bulkeley Citation2010; Burch Citation2010; Shaw & Theobald Citation2011; Dieleman Citation2013; McCormick et al. Citation2013).

Using Senge’s conceptualisation of learning organisations, a framework can be developed to examine whether a local authority has the characteristics to embrace and institutionalise learning in its ability to confront climate change. This framework helps to understand and ‘define’ a local authority as a learning organisation in climate governance (see ). In this framework, learning organisation disciplines are referred one-to-one to urban climate governance factors. However, disciplines and factors are interdependent and overlapping. For example, a learning organisation’s team learning most obviously correlates to urban climate governance’s emphasis on building organisational capacity. Team learning is also dependent on leadership, dialogue and communication. Effective urban climate policy is not the result of a single urban climate governance factor, just as a learning organisation is not the result of a single discipline; rather the interdependent combination of disciplines/factors facilitate effective urban climate policy. The remainder of this section frames urban climate governance literature from a learning organisation perspective.

Table 1. Local authorities as learning organisations for urban climate policy.

2.1. Individual dimension – leaders with personal mastery

Learning organisations start with personal mastery, including personal goals and commitment to learning (Senge Citation1990). This requires a new form of leadership, centred on vision. ‘In a learning organisation, leaders are designers, stewards and teachers. They are responsible for building organisations where people continually expand their capabilities to understand complexity, clarify vision and improve shared mental models – that is, they are responsible for learning’ (Senge Citation1990, p. 340). Urban climate governance also requires leaders who motivate employees, recognise opportunities, identify and transform barriers and make use of existing powers; who think beyond election cycles, focusing on long-term planning (Folke et al. Citation2005; Shaw & Theobald Citation2011). Siebenhüner and Arnold (Citation2007, p. 343) identify leaders who ‘initiate innovations and keep innovation processes in motion’. Such persons are often called policy entrepreneurs (Kingdon Citation1995; Bulkeley Citation2010). Leaders (e.g. mayors, senior staff) who understand the relevance of urban climate policy and sustainable development – and how they can increase a city’s overall attractiveness and competitiveness – are more likely to include climate change amongst policy priorities, especially when deciding how to use scarce financial and human resources (Rogers Citation2009; Burch Citation2010; UN-Habitat Citation2011; McCormick et al. Citation2013).

2.2. Internal dimension – dialogue and communication to develop shared mental models

Mental models include beliefs and principles that explain a cause-effect relationship, granting meaning to a particular issue (Bui & Baruch Citation2010). This requires dialogue and communication inside an organisation, including how a message is framed or perceived, which influences beliefs, values, incentives and action (Tàbara et al. Citation2010). In contrast, ineffective communication can jeopardise a learning organisation’s shared vision (Bui & Baruch Citation2010). Dialogue and communication strategies may reveal competing priorities or discourses, such as framing mitigation and adaptation as competing or complimentary (Nilsson & Gerger-Swartling Citation2009; Bulkeley & Castán-Broto Citation2013). Ideally, via dialogue, issues are continuously reframed until a consensus is reached. This is particularly relevant regarding complex and dynamic challenges like climate change, as learning to adapt to a changing system requires continuous dialogue to revitalise a mental model, enable comprehension and build trust, while acknowledging that different perspectives can coexist. In some contexts, climate change itself becomes contested and its problem definition politicised, stalemating any strategy, shared mental models and organisational learning (McCright & Dunlap Citation2011).

Learning organisation and urban climate governance research indicate that an organisational culture built on trust, respect and low-power distances (e.g. junior and senior staff speak freely and share responsibility) is more likely to generate a sense of community, encourage dialogue and facilitate continuous learning (Gephart et al. Citation1996; Folke et al. Citation2005; Rogers Citation2009). Within the local authority, dialogue across departmental silos and with stakeholders can reinforce a particular mental model, preventing strategies from undermining each other (Wilbanks & Sathaye Citation2007; Nilsson & Gerger-Swartling Citation2009). How climate change is communicated to society influences subsequent responses, especially if climate scepticism is relevant. Perceived vulnerability, community values, the level of societal empowerment and trust in (local) government, influence if, when and how cities act (Folke et al. Citation2005; Burch Citation2010; Glaas et al. Citation2010; Carter Citation2011).

2.3. Internal dimension – enhancing capacity via team learning

According to Senge (Citation1990, p. 14) ‘the basic meaning of a “learning organisation” is an organisation that is continually expanding its capacity to create its future’. A learning organisation’s culture encourages experimentation and risk-taking, with mistakes viewed as opportunities for organisational learning (Gephart et al. Citation1996). A focus on long-term sustainable development can reinforce adaptive capacity, strengthening a city’s response to climate change and improving resilience (Martens et al. Citation2009). Alavi and McCormick (Citation2004) argue that less hierarchical organisations tend to be more willing to work together towards a common goal, especially if they incorporate a future-oriented perspective. Committed employees, willing to acquire new skills, can expand organisational capacity (Senge Citation1990). Learning organisation and urban climate governance research identify the need for broad-based (e.g. city as a whole) and specific capacities (e.g. technical expertise) within an organisation (Klein et al. Citation2007; Bui & Baruch Citation2010). Capacity can be extended via interactive team learning, trainings or workshops, as well as providing spaces for interaction (Hinkel et al. Citation2009). Such activities, however, require resources, including financial support, staff time and expertise (Wilbanks & Sathaye Citation2007; Rogers Citation2009).

2.4. External dimension – communication and participation to build a shared vision

Building a shared vision, one that the local authority and relevant stakeholders (e.g. citizens, NGOs, private sector) contribute to, can result in a more authentic climate policy; moreover, successful implementation will depend on stakeholder support (Klein et al. Citation2007). To do so requires effective external communication: to generate curiosity and comprehension amongst stakeholders; and participation: to generate stakeholder engagement. When constructing a shared vision, participants understand what is expected, become part of a process and embrace ownership (Senge Citation1990; Fünfgeld Citation2010). Participation implies continuous learning; an organisation must learn to balance competing demands and discourses, whilst maintaining accountability and legitimacy (Bulkeley & Castán-Broto Citation2013). Doing so effectively can increase trust in local government organisations.

Active participation ensures that local expertise is not overlooked, but reinforces scientific knowledge (McEvoy et al. Citation2010). It can tap the skills and interests of the private sector and the public, offering creative approaches to common challenges, while building policy support. To facilitate participation requires some informality, flexibility and an emphasis on learning-by-doing, to balance competing demands (Folke et al. Citation2005; Rogers Citation2009; Glaas et al. Citation2010). Organisations embedded in cultures of trust, with high societal collectivism and social capital, are more likely to work together towards a common goal (Alavi & McCormick Citation2004; Folke et al. Citation2005).

2.5. External dimension – vertical and horizontal collaboration to enhance system thinking

For Senge (Citation1990), the preceding four disciplines are antecedents of the fifth, systems thinking – all together building a stronger organisation internally and externally. Systems thinking facilitates comprehension of how an organisation – a local authority – interacts with external actors, how internal decisions shape outside organisations and vice versa (Fullan Citation2004; da Silva et al. Citation2012). In urban climate governance, a city does not operate in a policy vacuum, but within a multilevel system, including vertical (e.g. higher government) and horizontal (e.g. city networks, neighbouring cities) interactions which influence a city’s ability to incorporate and institutionalise climate policies (Bulkeley Citation2010; Burch Citation2010; Bouteligier Citation2012). Given the complexity of climate change, vertical support (e.g. legal frameworks, financial subsidies) and external expertise (e.g. higher government, scientific institutions) can enable urban climate policies (UN-Habitat Citation2011; McCormick et al. Citation2013). Horizontally, dialogue and collaboration within city networks and with neighbouring municipalities can avoid spatial mismatches, while these stakeholders learn to share resources (Kern & Alber Citation2008). Nevertheless, local authorities should caution against relying too extensively on external resources, as political parties or the prioritisation of political agenda items – and (financial) support – may shift, in particular, during periods of austerity (den Exter et al. Citation2014).

3. Malmö as a learning organisation in addressing climate change

This section explores to what extent Malmö’s local authority emphasises learning and dialogue when enacting urban climate policies, and if it acts as a learning organisation.

At the national level, Sweden is considered to have one of the strongest local authority forms in Europe, politically and functionally, including the power to levy income taxes (Wollmann Citation2004; Lidström Citation2011). Highly decentralised, local authorities are responsible for the majority of public services and goods (e.g. education, planning, environmental protection, social services). Via the Local Government Act of 1991, local authorities have the autonomy to develop an organisational structure best suited to fulfil these duties (Wollmann Citation2004; Lidström Citation2011). Regarding mitigation, Sweden is considered a forerunner; it was placed highest in the 2012 Climate Change Performance IndexFootnote8 due to low emission levels and downward trends, notably in the housing sector (German Watch/Climate Action Network Europe Citation2012). Regarding adaptation, Sweden adopted a national adaptation strategy in 2009, including climate change scenarios (e.g. wetter winters, drier summers, changes in the Baltic Sea and impacts on natural, social and technical systems) and a focus on local adaptation (EEA Citation2012). Sweden was an early adopter of Local Agenda 21 and demonstrates strong commitment to local climate action, including national policy guidance and financial subsidies (Eckerberg & Forsberg Citation1998; Smedby & Neij Citation2013).

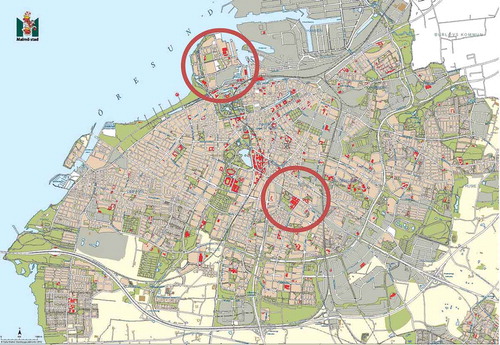

Located in the southernmost province, Skåne, Malmö is Sweden’s third largest city with a population of 300,000 (see ). The capital of Skåne, most of Malmö’s population and employment fall within municipal boundaries; still circa 10% of residents commute, primarily to Lund and Copenhagen, with a larger percentage (circa 20%) commuting into Malmö (Öresunddirekt Citation2013). Historically an industrial city, Malmö was home to Kockums Shipyard. This changed in the 1980s/1990s, when Malmö’s industries collapsed. Despite the challenges, this presented city leaders an opportunity to redirect Malmö’s identity. Three decisions initiated Malmö’s transition: the construction of Malmö University, the construction of the Öresund Bridge between Malmö and Copenhagen, and the construction of Bo01–Sweden’s first 100% renewable energy city-district in its Western Harbour which addressees mitigation and adaptation by design (e.g. energy efficiency, renewable energy, open storm-water management, green roofs). For over 15 years, Malmö has addressed sustainable development and climate change via technical measures (e.g. food waste and sewage sludge transformed to biogas), institutional measures (e.g. local laws, communication, participation) and large-scale pilot projects (e.g. Bo01). While mitigation is prioritised, as a low-lying coastal city, Malmö is vulnerable to climate change (e.g. sea-level rise, rising temperatures, sporadic flooding or drought) (Malmö Citation2012). Current policies attempt to integrate mitigation and adaptation within a sustainable development perspective.

GHG emissions are monitored in several ways: nationally, emissions are measured annually, including statistics per municipality; locally, Malmö conducts traffic splits on automobile numbers and monitors particulate matter. Information is publicly available on Malmö’s website. Statistics confirm that Malmö’s GHG emissions fell from 1460 thousand tonnes in 1990 to 1350 thousand tonnes in 2008, despite a population and GDP increase (Miljöbarometern Citation2013). However, in 2010, E-ON opened Öresundsverket, a natural gas combined-heat-and-power (CHP) plant supplying 3 TWh of electricity and 1 TWh of heat. Malmö’s GHG emissions increased to 2490 thousand tonnes – rising 84% between 2008 and 2010 – demonstrating that efforts to address climate change must emphasise collaboration with actors beyond municipal control, such as private energy companies.

Figure 1. Map of Malmö, demonstrating its coastal location. Two of Malmö’s main climate change/sustainability planning projects are circled. On the coast, is Western Harbour, a former brownfield. In the centre, is the retrofit of Augustenborg. This map was provided with permission from the City of Malmö.

Still, Malmö’s local authority is often cited as a forerunner in sustainable urban development and climate policy (e.g. Citation2010 World Habitat Award, 2009 UN-Habitat Scroll of Honour) and receives 5000 expert visitorsFootnote9 a year. Despite its environmental reputation, Malmö suffers from crime and segregation, notably in its immigrant-dominated neighbourhoods. According to interviewees, Malmö depicts a split image: a city of sustainability, of culture, the regional growth hub – and crime scenes and income disparity. Its greatest challenge is learning to connect these issues.

Malmö decided not to enact a specific climate policy; instead, mitigation and adaptation are integrated in various policies to ensure that climate targets are addressed across sectors and departments (Dowding-Smith Citation2013). Strategically, climate change is addressed in the Environmental Programme and the Master Plan. Malmö’s Citation(2009a) Environmental Programme has the objective that Malmö will become ‘Sweden’s Most Climate Friendly City’ (e.g. by 2020, all public buildings and procurement will incorporate renewable energy and energy efficiency; by 2030, the entire municipality will run on 100% renewable energy). Malmö’s Master Plan (until 2032) has the long-term objective that Malmö will become ‘a sustainable and attractive city’. Neither document is legally binding. Still, according to interviewees, adherence is high: circa 95% of city projects fulfil stated criteria. As adaptation is a newer policy area, Malmö also has an Action Plan for Adaptation, which includes an emphasis on ‘climate-adapted planning’ with references to several EU-sponsored projectsFootnote10 on adaptation experiments in Malmö. Operationally, climate change is addressed in several documents: on energy and buildings (e.g. Energy Strategy, Environmental Building Programme for Southern Sweden), on transportation (e.g. Traffic Environment Programme, Bicycle Programme, Walking Programme), on green/blue spaces (e.g. Green Plan, Nature Protection Plan and Rainwater Strategy) and on consumption (e.g. Policy for Sustainable Development and Food).

Climate strategies are predominantly coordinated by the Environmental Department, but other municipal departments and regional authorities are involved, including City Hall, the Streets and Parks Department (transport infrastructure and green spaces), the City Planning Office, the Real Estate Office (public land sales/leasing), the Internal Services Department (managing public infrastructure) and VA Syd (municipal water company). Transportation and waste management are addressed regionally: Skånetrafiken is responsible for public transport; SYSAV (South Scania Waste Company)Footnote11 is responsible for waste management.

As the largest land owner, building manager and employer, Malmö has considerable influence over GHG emissions in its jurisdiction. First, Malmö has a planning monopoly; all new projects must be approved by the City Planning Office. Second, all municipal buildings run on ‘green certified electricity’. Third, Malmö has influence over private developments, notably those built on municipal land. Following economic collapse, Malmö was forced to purchase Western Harbour from its retreating industries (e.g. Kockums, Saab). As the primary land owner, before contracts are signed and land sold, developers must agree to stricter requirements than national building standards, as specified in the Environmental Building Programme for Southern Sweden. New techniques, such as passive housing, green roofs or small-scale renewable energy instillations, are tested in Western Harbour and then applied to other parts of Malmö – with less hesitation from private developers, who learned to incorporate these techniques in Western Harbour. The Building ProgrammeFootnote12 is now required in all new developments that rent or purchase municipal land.

3.1. Individual dimension – leaders with personal mastery

Malmö’s climate polices are influenced by local politicians, directors and managers who demonstrate commitment to climate leadership (Norrman Citation2010; Dowding-Smith Citation2013). According to interviewees and proven by awards (e.g. Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize 2012), former Mayor Ilmar Reepalu (1994–2013) was a driving force behind Malmö’s forerunner status in urban climate governance, demonstrating a high level of personal mastery. Taking office at the height of Malmö’s economic crisis, Reepalu saw this as an opportunity: Malmö was in need of a new identity. Mayor Reepalu came to office with an economic vision, a youth vision, a social vision and a city planning vision – a long-term plan to move Malmö from its industrial past towards a sustainable future. Malmö’s own policy entrepreneur, Mayor Reepalu proclaimed ‘Malmö’s story of transition’ at conferences, among business partners and investors, and among employees and citizens; together constructing Malmö’s shared vision. Interviewees stated that this stable leadership and vision have influenced Malmö’s climate strategies.Footnote13

Leadership is also emphasised amongst department directors and sub-managers, who encourage innovative thinking and cross-sectoral collaboration. They encourage civil servants and technical experts to develop their own personal mastery, taking responsibility and engaging in inter-departmental issue committees.

3.2. Internal dimension – dialogue and communication to develop shared mental models

According to interviewees and conference documents, Malmö embeds climate policy and green growth within its broader sustainability strategies, developing a particular mental model. These issues are framed as relevant not only for the environment, but also for socioeconomic concerns. To enhance understanding and approval of climate strategies, routine meetings amongst departmental directors, local politicians and civil servants are organised, resulting in a shared and repeated mental model: ‘the Malmö story of transition’. Having everyone – at all levels of the organisation – reiterate the same story reduces miscommunications and conflicts and increases organisational trust, according to interviewees. Moreover, climate scepticism is low in Malmö; notably, the Environmental Programme was adopted unanimously across party lines (Dowding-Smith Citation2013). Still, building a coherent understanding of Malmö’s climate policy – even within the local authority – has proven to be a long process. A socially segregated city, Malmö has the highest crime rate in Sweden. Not all departments or politicians agree that climate change should feature as the top priority. This occasionally places social and technical departments at odds as to whether social equity and security, or infrastructure and environment, should be prioritised. Such challenges influence Malmö’s dominant mental model, and how it is framed and communicated. Malmö’s Environment Department encourages a more obvious link between environmental and social concerns, framed as environmental justice.

3.3. Internal dimension – enhancing capacity via team learning

Malmö’s economic crisis of the 1990s initiated a process of continuous capacity development. It forced Malmö to learn to function as a singular unit, across departments and hierarchies, adopting attributes of team learning. Over time, this generated organisational capacity within the local authority, including technical know-how, collaboration methods and the breakdown of sectoral approaches via regular cross-departmental workshops and meetings, especially among technical departments. Building on successes and failures, Malmö is not afraid to experiment with new policy or technical approaches; there are no mistakes, only learning processes (Norrman Citation2010). Malmö perceives sustainability as a continuous learning process, referred to as an ongoing journey.Footnote14

Malmö has circa 50 employees engaged in climate and sustainability strategies. Thirty work at the Environment Department; others are integrated within the City Planning Office, Streets and Parks Department, Internal Services Department and Real Estate Office. Themes, like transport, have coordination teams which meet monthly; this facilitates policy integration across departmental silos to combine expertise and develop integrated strategies. Meetings are often held in Malmö’s interdepartmental sustainability centre, Helix, a physical space to foster collaboration, enrich team learning and build local capacity. Dedicating sufficient resources and high staff numbers in the local authority is a strategic decision; it allows employees time to explore innovative policy or planning approaches. Malmö also brands itself as a climate forerunner: nationally, within Europe and in network affiliations. This has positive economic consequences: for example, the Danish wind energy company Vestas relocated its Nordic headquarters to Malmö. Malmö was also placed fourth in Forbes ‘World’s 15 most inventive cities’ for 2013, noting efforts in the cleantech sector.

3.4. External dimension – communication and participation to build a shared vision

While Malmö emphasises structured internal communication, stakeholder engagement is less formalised. Instead, a learn-by-doing approach encourages flexible participation of NGOs, citizens and businesses. Although flexible, communication and participation are emphasised in the Environmental Programme – building a shared vision together.

Concerning communication, Malmö offers study tours for visiting urban experts in its ‘climate arenas’ (e.g. Augustenborg Botanical Roof Garden, Bo01). Since 2007, Malmö has hosted the No Ridiculous Car Journeys Campaign every May, during which civil servants in orange jumpsuits ride on blue bicycles to promote city cyclingFootnote15 as an alternative to cars for short distances. Public concerts in city squares highlight cycling, and citizens can compete to be the ‘most ridiculous car driver’. This cycling campaign is highly visible: when polled, 50% of residents acknowledge awareness of the campaign; 15% state it has altered their driving habits (Malmö Citation2010).Footnote16 Via such strategies, planners estimate that 35% of commuting to work and school is done by bicycle; meanwhile, car journeys fell from 52% in 2003 to 41% in 2008 (Malmö Citation2009b). Still, for 10 years, total car numbers remain constant, due to a rising population and regional commuting, indicating Malmö will have to work closer with neighbouring municipalities and improve public transport options to lower car numbers. Current transport emissions from commuting are circa 500,000 tons of CO2-equivelent per year (Malmö Citation2009b).Footnote17

Concerning sustainability education, several programmes receive funding and political support. Since 2001, Malmö’s local authority offers Climate-X, interactive workshops for secondary students on climate change. Since 2010, Malmö, Lund and Copenhagen collaborate in an EU-sponsored education partnership, Öresund Classroom, which ‘engages students and teachers in envisioning new learning processes for a sustainable society’. Additionally, by 2020, all schools, health care and public catering will serve organic or ethically certified meals.Footnote18 Several schools have done so already, remaining within the same budget, often via reduced meat consumption. These methods were shared with Malmö School Restaurant staff during a series of workshops in 2011, and teachers educate students on the link between food consumption and climate change.

Concerning participation, Malmö realises that it will not meet its climate targets without engaging citizens and the private sector. Regarding more vulnerable citizens, Malmö attempts to combine social inclusion and environmental sustainability, focusing on specific neighbourhoods. Its largest efforts are in Augustenborg and Rosengård. Built in the 1950s and 1960s, respectively, these neighbourhoods suffer(ed) from flooding and poor insulation as well as crime and unemployment. Both are predominately immigrant communities, so participation techniques vary to engage diverse populations, while focusing on target groups (e.g. youth, elderly, community leaders, women). Ecocity Augustenborg began, in 1998, to address seasonal flooding (via green roofs and open storm-water management) and energy concerns (insulating 1,800 apartments, incorporation of solar panels). Simultaneous with physical measures, citizen participation was stressed from the beginning (via information sessions, workshops, festivals and cultural events) to encourage project ownership, clarify expectations of the local authority and residents, and to facilitate project legitimacy. Roughly 20% of residents participated and many projects were resident-initiatives, such as the open storm-water management system, a community carpool and Café Summer (café/community space).Footnote19

Building on the lessons of Augustenborg, in 2008 Malmö, together with a public housing company, initiated similar strategies in Rosengård. Plans include better connectivity to central Malmö (e.g. improved cycling lanes, more buses), renewable energy (e.g. urban windmills, solar panels at the school) and improved social spaces (e.g. climate-smart food centre, community gardening, women’s activity centre). In Rosengård, Malmö attempts to combine innovative environmental technology, planning and increased social and economic integration, working with residents to do so.

Concerning resident initiatives, the Environment Department offers grants (circa 1.3 million SEK/year) for community start-ups. Previously undersubscribed, many high-quality applications now compete. In addition to official grants, municipal budget flexibility is encouraged. As stated in an interview, ‘When it comes to community organisations, they come with passion and excitement to start something now... If we are going to be an active support mechanism, we need flexibility.’Footnote20 One start-up, Children in the City, linked elderly residents with immigrant families in socially deprived areas via arts and urban agriculture. This evolved into a non-profit, called Grow in the City, which Malmö hired to develop community gardens in Rosengård.

Concerning public–private partnerships, Malmö participated in Sweden’s Building-Living-Dialogue, a collaborative planning method to engage architects, developers and civil servants in partnership throughout the building process, combining expertise on specific themes, such as energy, safety and green space (Smedby & Neij Citation2013). This collaboration reduced production costs (e.g. building a joint-parking garage, shared landscaping), while addressing mitigation and adaptation (e.g. passive-energy housing, green space planning) and other sustainability concerns (e.g. health, safety). Malmö also provides physical spaces to encourage innovation: Minc is an incubator and workspace for sustainability entrepreneurs, venture capitalists and academics.

Still, Malmö’s climate ambitions remain strongly influenced by its largest stakeholders, notably its energy companies. The 2009 opening of E-ON’s natural gas CHP plant, Öresundsverket, drastically increased Malmö’s per capita GHG emissions. As energy security is of national interest (riksintresse) however, Malmö does not have the authority to obligate renewable energy, for example converting Öresundsverket to biogas production. Still, according to an interviewee, through continued dialogue between Malmö and E-ON, E-ON is beginning to consider a transformation to biogas. This, however, is a slow process: in 2008, E-ON had no interest in biogas; by 2010, they started ‘speaking’ about biogas as a substitute for natural gas. No timeline is established. In other projects, E-ON is more cooperative. In Malmö’s new Hyllie neighbourhood, Malmö, VA Syd and E-ON signed a ‘climate contract’ on renewable energy and energy efficiency. According to an interviewee, ‘E-ON sees Malmö as a testing ground for new innovations, which can be used for marketing/profiling.’Footnote21 E-ON and Malmö are also piloting smart grids in several neighbourhoods.

Dialogue and collaboration with Malmö’s largest stakeholders, and its more vulnerable residents, remains a dual priority to further Malmö’s climate policies.

3.5. External dimension – vertical and horizontal collaboration to enhance system thinking

While Malmö has significant autonomy in arranging its climate policy, it functions in a broader system, including vertical and horizontal interactions, influencing its climate policy goals. A systems thinking perspective helps Malmö recognise external interactions with multiple actors at multiple levels, and make use of them in advancing climate learning and leadership.

Vertically, Malmö collaborates with national agencies, such as the Energy Agency (Energimyndigheten), the Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) and the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (Boverket). The EPA’s Climate Investment Programme (KLIMP) and its predecessor Local Investment Programme (LIP) funded numerous climate projects in Malmö, providing grants for hard and soft measures. KLIMP concluded in 2012, but other agencies continue to offer financial support. The Energy Agency runs Sustainable Municipalities and the Housing Board finances one-third of project costs via Delegation for Sustainable Cities. In Citation2011, Malmö received one billion SEK (114€ million) from the Delegation to retrofit Rosengård on energy efficiency, transportation, climate-smart food and participation strategies for hard-to-reach groups. Still, most subsidies terminated at the end of 2013, with no new subsidy schemes yet established.

At the EU level, Malmö has a permanent representative in Brussels to follow, influence and learn about new legislation and funding opportunities. Many departments have an EU coordinator. Consequently, Malmö is involved in multiple EU-sponsored projects,Footnote22 which encourage learning and interaction among partner cities and within the local authority, further engraining climate strategies. Malmö joined the EU Covenant of Mayors in 2008 and former Mayor Reepalu chaired the EU Committee of Regions’ Commission for Environment, Energy and Climate Change.

Horizontally, Malmö works with city networks and regional partners. Network participation includes ICLEI, Eurocities (Reepalu chaired the Environment Forum), Baltic Metropoles, Energy Cities, Union of the Baltic Cities and Similar Cities. Nationally, Malmö is involved with Klimat Kommunerna and collaborates with Sweden’s largest cities, Stockholm and Göteborg. Reepalu also served as president and vice president of Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

Regionally, Malmö engages with neighbouring municipalities and sectoral authorities in Skåne, depending on specific policy goals (e.g. energy, transport, climate adaptation). Malmö participates in Energy Öresund – a collaboration of Swedish and Danish municipalities and energy companies to become ‘the first carbon-neutral region in Europe’. Collaboration with Lund and Copenhagen is high on the political agenda, including research/business links and improved public transportation, as well as a high-speed cycle way between Malmö and Lund. With Vellinge and Flasterbo (south of Malmö), new offshore wind-park and a light-rail link are being discussed. Still, interviewees indicate that few concrete steps have been taken, in part, because Malmö does not have autonomy outside its own jurisdiction. Climate adaptation presents a new avenue for cooperation with neighbouring local authorities; currently, Malmö discusses storm-water management and flooding concerns with neighbouring municipalities.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This paper examined how local authorities, as learning organisations, address climate change. Due to the multiple complexities and uncertainties of climate change, when local authorities develop and implement (long-term) urban climate policies, they should be adaptive and flexible. Local authorities need to adopt an institutionalised ability to continuously learn to adapt their strategies, thus becoming learning organisations. To examine what it means for a local authority to become a learning organisation in urban climate governance, we examined one of the ‘best practitioners’ until now: Malmö, Sweden.

Malmö’s local authority appears to have adopted various characteristics of a learning organisation, in its organisational structure and working methods when addressing climate change. Its climate priorities are embedded in top steering documents and its vision to become an ‘environmentally, socially and economically sustainable city’. Climate change is the challenge; the solution, a continued focus on sustainable development and learning. Malmö could have followed a very different trajectory after its economic crisis of the 1980s/1990s. Instead, leadership, a shared, internalised and consistently disseminated sustainability vision, and an organisational structure centred on learning, drove climate policy ambitions and implementation forward. Although the former mayor was criticised in some areas, his environmental leadership offers a lasting legacy. Likewise, priorities on dialogue, communication and partnerships (internally and externally) enhance Malmö’s learning capacity, and encourage citizens and private actors to participate in co-developing and co-implementing a common climate vision. Malmö takes advantage of vertical and horizontal collaborations to facilitate its climate policies, such as national/EU support, engaging in city networks and with regional partners. Learning Organisation Theory and urban climate governance factors are evident in Malmö, albeit some factors having greater relevance than others. It is the interdependence of many factors (rather than one single factor) that is responsible for Malmö’s successful, and in many regards, ‘leading’ climate policy. This resembles the ideas of interdependent disciplines within Learning Organisation Theory.

But challenges remain for Malmö’s local authority. First, several individuals, notably Malmö’s long-standing mayor, are accredited as drivers behind its success. Will Malmö maintain its position as an innovative forerunner, now that Mayor Reepalu has stepped down? Theoretically, learning, dialogue and partnership should have institutionalised innovativeness and flexibility, supporting adaptive climate policies within Malmö’s political and organisational structure, making it less vulnerable to personnel/leadership change; but time will tell. Second, with the opening of a natural gas CHP plant in 2009, Malmö saw its GHG emissions increase for the first time in a decade. Malmö’s ability to reduce emissions is largely dependent on the energy plant owner E-ON, challenging Malmö’s authority and agency to address climate change. With E-ON’s climate choices largely out of municipal control, achieving Malmö’s climate policy goals will require continuous dialogue and partnership with E-ON. Third, Malmö has relied on national and EU financial support to facilitate many of its climate actions. However, key subsidies (e.g. KLIMP) concluded in 2012 or 2013, while the European financial crisis may limit EU funding. Nevertheless, due to the decentralised nature of authority in Sweden, Malmö is largely responsible for climate-relevant sectors and policies, however, with fewer financial resources to do so. Malmö has to safeguard other funding sources or reduce its ambitions. Fourth, while a climate frontrunner, Malmö is a divided city with enduring social challenges. Addressing social challenges remains a priority – though it competes with others. Malmö’s attempt to link social and climate challenges, via an environmental justice perspective, is key to the enduring success of its climate governance model which focuses on dialogue, participation and shared visions.

Malmö, as a learning organisation, offers several lessons for other cities addressing urban climate governance. First, deliberate and structured methods to facilitate ‘working across departmental silos’ enable continuous dialogue and learning within the local authority, especially to balance different priorities and design innovative strategies. Second, strategic local politicians, who adopt and actively propagate long-term visions and recognise opportunities, leverage the implementation of urban climate policies. Third, using various (complementary) methods for dialogue and participation encourages stakeholder and citizen engagement. Stakeholders should be involved early to ensure ownership, in particular, when the regulatory powers and resources of local authorities are limited. Continuous dialogue – within the organisation and with stakeholders – can institutionalise continuous learning and flexible working methods to adapt to coming challenges, including climate change.

Notes

1. Debates remain on how this is calculated (consumption or production). Cities are often more efficient than suburban/rural areas at similar affluence levels (Dodman Citation2009).

2. In this paper, we refer to urban climate governance and urban climate policies. Urban climate governance refers to broader climate activities and strategies in a city, including those of non-governmental actors. Urban climate policies refer to concrete policies of the local authority.

3. Adaptive, in this context, refers to the ability to adjust to emerging situations, including climate change, technical and economic resources, human/social capital and governance schemes (Martens et al. Citation2009).

4. Other acknowledgements include: first (of 800 projects) in European Campaign for Take‐off for Malmö’s ‘City of Tomorrow: 100% Local Renewable Energy’ (2000); Design Prize winner (2005); Liveable Communities Award winner (London, 2007); featured in State of the World Report (WWI, 2007); World’s 13 most creative cities (Fast Company, 2009); BEX Award for Best Master Plan (World Green Building Council, 2009); Sweden’s Most Sustainable City 2010 (Swedish Environmental Magazine, Miljöaktuellt) and national recognition for cycling and sustainable procurement, 2012.

5. The lead author previously worked for Malmö’s Local Authority, providing in-depth understanding of its climate and sustainability policies, including organisational elements.

6. In Scandinavia, public participation and information access were equally important for NPM (Wollmann Citation2004; Lidström Citation2011).

7. Not all European countries subscribe to decentralisation; the United Kingdom remains primarily centralised with nominal localism.

8. In this ranking, Sweden ranked highest in 2008 and 2009 and second highest in 2010, 2011 and 2013.

9. ‘Expert visitors’ include urban planners, politicians, academics, city networks and business partners.

10. Includes: Green-Clime-Adapt, sponsored by EU LIFE+ and Green and Blue Space Adaptation for Urban Areas, sponsored by EU Interreg IVA.

11. SYSAV is a publicly owned company, jointly owned by several municipalities in Skåne (http://www.sysav.se/).

12. The national government is currently debating whether local governments have legal footing to set standards higher than those of the national government.

13. Mayor Reepalu’s leadership has been questioned in other areas, notably regarding property vandalism against a Malmö minority group (Stevens Citation2010). While statements were clarified, this tainted his reputation, weakening his credibility. Reepalu stood down in 2013.

14. This conversation was held amongst Malmö politicians and conference delegates attending COP15 in Copenhagen, December 2009. The lead author attended this meeting.

15. The campaign targeted those driving 5 km or less, referred to as ‘ridiculous driving’.

16. The campaign was replicated in Helsingborg, Kristianstad and Umeå (Malmö Citation2010).

17. This does not include the Copenhagen–Malmö Port (CMP). As a binational port, Malmö does not have regulatory authority over CMP, which adheres to national and EU legislation regarding port emissions (e.g. sulfur). Still, industries in Northern Harbour are part of an EU-sponsored project on E-harbours to encourage electricity use in industrial vehicles and facilitate energy exchange via industrial symbiosis.

18. Specified in Malmö’s Policy for Sustainable Development and Food (2010).

19. Ecocity Augustenborg had other spin-off effects. Interviewees highlight an increased level of trust in (local) public decision-making. Participation in local elections also increased from 54% in 1998 to 79% in 2002 and Augustenborg has Malmö’s highest recycling rate, at 50% (World Habitat Award Citation2010).

20. Head of Sustainable Communities at Malmö Environment Department; 8 March 2012.

21. Malmö Environment Department representative; 30 September 2013.

22. EU-financed support schemes include, but not limited to: CIVITAS (Sustainable Mobility for people in urban areas), LIFE+ (Plug-in-city Malmö and Climate Living in Cities Concept), Interreg IVA programme (Öresundsklassrummet) and IEE (Partnership Energy Planning as a tool for realising European Sustainable Energy Communities).

References

- Alavi SB, McCormick J. 2004. A cross-cultural analysis of the effectiveness of the learning organisation model in school contexts. Int J Educ Manag. 18:408–416.

- Armstrong A, Foley P. 2003. Foundations for a learning organization: organization learning mechanisms. Learn Organ. 10:74–82. doi:10.1108/09696470910462085

- Betsill M, Bulkeley H. 2006. Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Global Governance. 12:141–159.

- Bouteligier S. 2012. Cities, networks, and global environmental governance: spaces of innovation, places of leadership. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bui H, Baruch Y. 2010. Creating learning organizations: a systems perspective. Learn Organ. 17:208–227. doi:10.1108/09696471011034919

- Bulkeley H. 2010. Cities and the governing of climate change. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 35:229–253. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-072809-101747

- Bulkeley H, Castán-Broto V. 2013. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans Inst Br Geographers. 38:361–375. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00535.x

- Burch S. 2010. In pursuit of resilient, low carbon communities: an examination of barriers to action in three Canadian cities. Energy Policy. 38:7575–7585. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.06.070

- Carter JG. 2011. Climate change adaptation in European cities. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 3:193–198. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2010.12.015

- Da Silva J, Kernaghan S, Luque A. 2012. A systems approach to meeting the challenges of urban climate change. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 4:125–145. doi:10.1080/19463138.2012.718279

- Den Exter R, Lenhart J, Kern K. 2014. Governing climate change in Dutch cities: anchoring local climate strategies in organisation, policy and practical implementation. Local Environ. doi:10.1080/13549839.2014.892919

- Dieleman H. 2013. Organizational learning for resilient cities, through realizing eco-cultural innovations. J Cleaner Prod. 50:171–180. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.027

- Dodman D. 2009. Blaming cities for climate change? An analysis of urban greenhouse gas emissions inventories. Environ Urbanization. 21:185–201. doi:10.1177/0956247809103016

- Dowding-Smith E. 2013. Integrating ambitious renewable energy targets in city planning [Internet]. Bonn: ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability and International Renewable Energy Agency. [cited 2013 Sep]. Available from: http://www.irena.org/Publications/RE_Policy_Cities_CaseStudies/IRENA%20cities%20case%207%20Malmo.pdf

- Eckerberg K, Forsberg B. 1998. Implementing Agenda 21 in local government: the Swedish experience. Local Environ. 3:333–347. doi:10.1080/13549839808725569

- European Environment Agency. 2012. National adaptation strategies [Internet]. [cited 2013 Sept]. Available from: http://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/climate/national-adaptation-strategies

- Flyvbjerg B. 2004. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. In: Seale C, Gobo G, Gubrium J, Silverman D, editors. Qualitative research practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; p. 420–434.

- Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 30:441–473. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

- Fullan M. 2004. Leadership and sustainability: system thinkers in action. Thousand Oaks (CA): Corwin Press.

- Fünfgeld H. 2010. Institutional challenges to climate risk management in cities. Environ Sustainability. 2:156–160.

- Gephart MA, Marsick VJ, VanBuren ME, Spir MS. 1996. Learning organisations come alive. Train Dev. 50:34–45.

- German Watch/Climate Action Network Europe. 2012. The climate performance index: results 2011. Bonn (DE): German Watch.

- Glaas E, Jonsson A, Hjerpe M, Andersson-Sköld Y. 2010. Managing climate change vulnerabilities: formal institutions and knowledge use as determinants of adaptive capacity at the local level in Sweden. Local Environ. 15:525–539. doi:10.1080/13549839.2010.487525

- Hinkel J, Bisaro S, Downing TE, Hofmann ME, Lonsdale K, McEvoy D, Tàbara JD. 2009. Learning to adapt: narratives of decision makers adapting to climate change. In: Hulme M, Neufeldt H, editors. Making climate change work for us: European perspectives on adaptation and mitigation strategies. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Hoornweg D, Sugar L, Trejos Gómez CL. 2011. Cities and greenhouse gas emissions: moving forward. IIED’s Environ Urbanization Rep. 23: 207–227. London: Sage Publications.

- International Energy Agency. 2008. World energy outlook 2008. Paris: IEA.

- Katusiimeh MW, Mol APJ, Burger K. 2012. The operations and effectiveness of public and private provision of solid waste collection services in Kampala. Habitat Int. 36:247–252. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.10.002

- Kern K, Alber G. 2008. Governing climate change in cities: modes of urban climate governance in multilevel systems. Paper presented at: OECD Conference on Competitive Cities and Climate Change Final Report. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Kern K, Bulkeley H. 2009. Cities, Europeanization and multi-level governance: governing climate change through transnational municipal networks. JCMS J Common Market Stud. 47:309–332. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2009.00806.x

- Kern K, Mol APJ. 2013. Cities and global climate governance: from passive implementers to active co-decision makers. In: Stiglitz JE, Kaldor M, editors. The quest for security: protection without protectionism and the challenge of global governance. New York (NY): Columbia University Press; p. 288–305.

- Kingdon JW. 1995. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. New York (NY): Harper Collins.

- Klein RJT, Huq S, Denton F, Downing TE, Richels RG, Robinson JB, Toth FL. 2007. Inter-relationships between adaptation and mitigation. In climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Lidström A. 2011. Sweden: party-dominated subnational democracy under challenge? In: Loughlin J, Hendriks F, Lidström A, editors. The Oxford handbook of local and regional democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 261–281.

- Liu W, Wan C, Mol APJ. 2012. Rural residential CO2 emissions in China: where is the major mitigation potential? Energy Policy. 51:223–232. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.05.045

- Malmö. 2009a. Environmental programme 2009–2020 [Internet]. Malmö Local Authority. [cited 2013 Jan]. Available from: http://www.malmo.se/download/18.6301369612700a2db9180006235/1383649547373/Environmental-Programme-for-the-City-of-Malmo-2009-2020.pdf.

- Malmö. 2009b. Malmöbornas resvanor och attityder till trafik och miljö 2008: samt jämförelse med 2003 [Internet]. (Malmö residents travel habits and attitudes concerning traffic and the environment 2008: compared with 2003.) Malmö Local Authority. [cited 2013 Jan]. Available from: http://www.malmo.se/download/18.48c74f1f1249b31458c80007230/1383643899697/RVU%2BMalm%C3%B6%2Bslutrapport%2B20090421.pdf

- Malmö. 2010. Final application for the European green capital award: City of Malmö. Malmö Local Authority.

- Malmö. 2011. Master plan 2013 [Internet]. Malmö Local Authority. [cited 2013 Jan]. Available from: http://www.malmo.se/download/18.723670df13bb7e8db1bc547/1383643976032/OP2012_planstrategi_utstallningsforslag_web_jan2013.pdf

- Malmö. 2012. Handlingsplanförklimatanpassning Malmö 2012–2014 [Internet]. (Action plan for climate adaptation). Malmö Local Authority. [cited 2013 Sep]. Available from: http://www.preventionweb.net/applications/hfa/lgsat/en/image/href/2327

- Malmö. 2013. Miljöbarometern [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jan]. Available from: http://miljobarometern.malmo.se/

- Martens P, McEvoy D, Chang C. 2009. The climate change challenge: linking vulnerability, adaptation and mitigation. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 1:14–18. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2009.07.010

- McCormick K, Anderberg S, Coenen L, Neij L. 2013. Advancing sustainable urban transformation. J Cleaner Prod. 50:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.01.003

- McCright AM, Dunlap RE. 2011. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming 2001-2010. Sociol Q. 52:155–194. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

- McEvoy D, Lindley S, Handley J. 2006. Adaptation and mitigation in urban areas: synergies and conflicts. Proc ICE Integr Municipal Engineer. 159:185–191. doi:10.1680/muen.2006.159.4.185

- McEvoy D, Matczak P, Banaszak I, Chorynski A. 2010. Framing adaptation to climate-related extreme events. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 15:779–795. doi:10.1007/s11027-010-9233-2

- Nilsson A, Gerger-Swartling Å. 2009. Social learning about climate adaptation: global and local perspectives. Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Norrman M. 2010. Därför är Malmö miljöbästakommunen i Sverige [Internet]. (This is why Malmö is Sweden’s best environmental municipality. Miljöaktuellt). Stockholm: Miljöaktuellt. [cited 2013 Jan]. Available from: http://miljoaktuellt.idg.se/2.1845/1.331027/darfor-ar-malmo-miljobasta-kommunen-i-sverige

- Öresunddirekt. 2013. Öresund Information Centre [Internet]. [cited 2013 Sept]. Available from: http://www.oresunddirekt.se/

- Örtenblad A. 2002. A typology of the idea of learning organization. Manag Learn. 33:213–230. doi:10.1177/1350507602332004

- Örtenblad A. 2007. Senge’s many faces: problem or opportunity?. Learn Organ. 14:108–122. doi:10.1108/09696470710726989

- Rogers N. 2009. A study of regional partnership and collaborative approaches for enhanced local government adaptation to climate change [Internet]. The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Australia. [cited 2013 Jan]. Available from: http://www.churchilltrust.com.au/media/fellows/2009_Rogers_Nina.pdf.

- Rose L, Ståhlberg K. 2005. The Nordic countries: still the ‘promised land'? In: Denters B, Rose L, editors. Comparing local governance: trends and developments. New York (NY): Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rowley J, Gibbs P. 2008. From learning organization to practically wise organization. Learn Organ. 15:356–372. doi:10.1108/09696470810898357

- Senge PM. 1990. The fifth discipline: the art and practice of a learning organisation. Sydney: Random House.

- Shaw K, Theobald K. 2011. Resilient local government and climate change interventions in the UK. Local Environ. 16:1–15. doi:10.1080/13549839.2010.544296

- Siebenhüner B. 2008. Learning in international organizations in global environmental governance. Global Environ Politics. 8:92–116. doi:10.1162/glep.2008.8.4.92

- Siebenhüner B, Arnold M. 2007. Organizational learning to manage sustainable development. Business Strategy Environ. 16:339–353. doi:10.1002/bse.579

- Smedby N, Neij L. 2013. Experiences in urban governance for sustainability: the constructive dialogue in Swedish municipalities. J Cleaner Prod. 50:148–158. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.044

- Stevens A. 2010. Ilmar Reepalu: Mayor of Malmö. City Mayors [Internet]. [cited 2014 Jan]. Available from: http://www.citymayors.com/mayors/malmo-mayor-reepalu.html

- Tàbara JD, Dai X, Jia G, McEvoy D, Neufeldt H, Serra A, Werners S, West JJ. 2010. The climate learning ladder. A pragmatic procedure to support climate adaptation. Environ Policy Governance. 20:1–11.

- Tompkins E, Adger W. 2005. Defining response capacity to enhance climate change policy. Environ Sci Policy. 8:193–198. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2005.06.012

- UN-Habitat. 2011. Cities and climate change: global report on human settlements. London: Earthscan.

- [UNFPA] United Nations Population Fund. 2007. State of world population 2007: unleashing the potential of urban growth. New York: UNFPA Secretariat.

- Wilbanks TJ, Sathaye J. 2007. Integrating mitigation and adaptation as responses to climate change: a synthesis. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change. 12:957–962. doi:10.1007/s11027-007-9108-3

- Wilson E, Piper J. 2010. Spatial planning and climate change. London: Routledge.

- Wollmann H. 2004. Local government reforms in Great Britain, Sweden, Germany and France: between multi-function and single-purpose organisations. Local Government Stud. 30:639–665. doi:10.1080/0300393042000318030

- World Habitat Award. 2010. Ekostaden Augustenborg; [cited 2013 Sept]. Available from: http://www.worldhabitatawards.org/winners-and-finalists/project-details.cfm?lang=00&theProjectID=8A312D2B-15C5- F4C0-990FBF6CBC573B8F

- Yeo RK. 2005. Revisiting the roots of learning organization: a synthesis of the learning organization literature. Learn Organ. 12:368–382. doi:10.1108/09696470510599145

- Yin RK. 2009. Case study research: design and methods. Los Angeles (CA): Sage.