Abstract

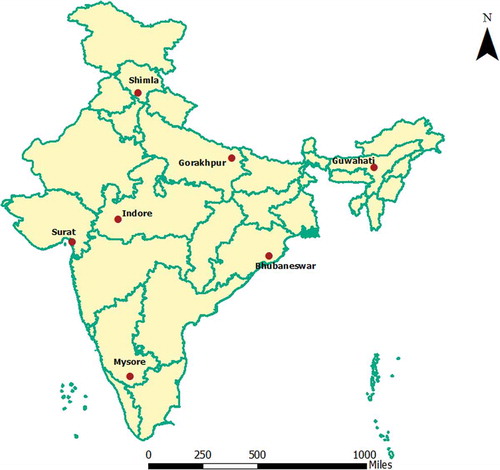

This article highlights the various methodologies adopted for the preparation of climate resilience strategy in seven cities (Surat, Indore, Gorakhpur, Guwahati, Shimla, Bhubaneswar and Mysore) of India under the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN) programme. It analyses these methodologies and the overall processes adopted in each of these cities for its potential for replication and brings out the inherent challenges, gaps and opportunities in achieving this.

Discussions with the key city stakeholders involved in the ACCCRN process and implementing partners were conducted to understand their views on the need and efficacy of resilience planning in Indian cities as well as the challenges encountered by them during the process. Several issues and suggestions that have emerged from the experiences of the city stakeholders could guide city-level engagements in future. Based on these experiences, key lessons have been highlighted with the aim of guiding the cities to undertake urban resilience planning in future.

1. IntroductionFootnote1

Climate change will impose a wide array of stressors on urban areas. Some of these are likely to involve the direct and easily understood impacts of storms, sea level rise, temperature change and extreme climatic events, but others will involve indirect impacts that reverberate through the systems, viz., energy, transport, communications, etc., that urban areas depend on (Moench et al. Citation2011). Planning for urban resilience offers cities the opportunity to prepare for and respond to these stressors. Resilience can be defined as the ‘ability of a system, community, or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner by preserving and restoring its essential basic structures and functions’ (UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction) Citation2009, p. 24). Urban resilience generally refers to the ability of a city or urban system to withstand a wide array of shocks and stresses (Leichenko Citation2011).

Because climate change impacts cross multiple scales and sectors, urban climate change resilience (UCCR) planning requires involvement of multiple levels of governance, such as the central government, state government and the city government. While the central government is the policy-making body, the state government generally looks at the budgetary allocations and policy facilitation and implementation. The policies formed at both national and state levels are materialised into implementable projects at the city or local level. It is this interaction and coordination at various levels that helps a city achieve its development goals. In India, the Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD) is responsible for formulating national-level policies and coordinating the activities of various nodal authorities related to urban development in the country. However, the function of urban development falls under the State List of the Constitution of India. This means that the formulation and implementation of development plans and projects falls within the parameters of the state-level nodal departments. The legislations and regulations governing urban development and finance allocation are also defined at the state level. At the city level, the municipal corporations are responsible for provision and maintenance of urban infrastructure and services. Thus, urban resilience planning depends on the integration and coordination with multiple agencies. Achieving this cross-departmental coordination becomes a grave challenge especially when climate change risk does not always emerge as a priority for city administration (Jabareen Citation2013). Even local governments that demonstrate proactive strategies often face a lack of legal mandate from national governments to implement advanced measures (OECD Citation2010; Thornbush et al. Citation2013).

Taking into consideration the current capacity gaps in the cities of the developing world, there is a need to identify different ways of scaling up capacity-building to equip city stakeholders to advance UCCR efforts (Brown et al. Citation2012). This could be achieved through training programmes, workshops, web-based short courses, etc. Proactive attempts to build climate resilience require coordinated actions by various local government departments and new mechanisms for collaboration between local government departments and with civil society organisations (Tyler & Moench Citation2012).

In Asia, the role of the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN), a seven year initiativeFootnote2 (2008–2015), supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, has been significant in building UCCR. Over the years, ACCCRN has worked in 10 cities in four Asian countries (India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam). All these cities were chosen through a set list of criteria, such as geographic location, climate-related hazards already being faced by these countries and interest of the local government to associate with the initiatives, to name a few. The initiative has supported these cities by developing and demonstrating effective processes and practices for addressing urban climate vulnerabilities using participatory planning as well as implementing targeted intervention projects. Some of these cities, such as Surat, have also gone forward to institutionalise urban climate resilience agenda into the city government’s agenda. The city stakeholders, both civil society and private sector, played an active role in the process and spearheaded several pilot projects in the city. Some of these projects included setting up of the Urban Health and Climate Resilience Centre (UHCRC) and the Surat Climate Change Trust (SCCT). The approach brought out several examples and methodologies that can be replicated and adopted by other cities as well. The initiative is now poised to expand its network and reach to 30+ cities within six countries. This calls for a deeper understanding and analysis of merits and demerits of the various methodologies adopted by different partners in different cities.

The discourse in this article focuses on the methodologies adopted in the seven Indian ACCCRN cities – Surat, Indore, Gorakhpur, Shimla, Bhubaneswar, Mysore and Guwahati, for vulnerability assessment and climate resilience planning. The cities for this study have been chosen on the basis that these were the first amongst the ones where ACCCRN is engaging and had developed their respective resilience strategies to the extent that this study could analyse the impact it made and its potential for replication. The article assesses and informs the merit and replication potential of these methodologies for planned scaling up and expansion of such initiatives. It draws from literature review of the assessment studies and strategy documents prepared under the programme, and detailed discussions and structured interviews with all the ACCCRN partners in India and the key city stakeholders involved in the process in each of the seven cities. It brings about the key components of various methodologies and discusses how methodological differences and procedures differ from city to city due to the contextual differences of each city. It may be noted that the article does not draw inferences on how technically sound these methodologies are, but aims to understand the stages, drivers and challenges in the process of building urban climate resilience. The article provides recommendations that may be useful to the city stakeholders for replicating similar resilience planning exercises.

2. The ACCCRN programme

The ACCCRN programme was devised as a holistic programme involving multiple partner organisations () with an objective of building capacities to plan, finance and coordinate resilience strategies in the chosen cities, developing network for knowledge and learning coming out from the experiences from cities, and scaling up the learning and processes to new cities (acccrn.org).

Table 1. Partner organisations involved in the process.

In ACCCRN, the concept of resilience has drawn heavily from literature on ecosystems and socio-ecological systems, which typically define resilience as ‘…the ability to absorb disturbances, to be changed and then to re-organize and still have the same identity (retain the same basic structure and ways of functioning)’ (Brown et al. Citation2012, p. 534).

The cities engaged in the ACCCRN process focused their activities on anticipating how their city’s vulnerabilities will be exacerbated and altered by climate change. Urban populations are most affected by changing conditions, so climate resilience strategies and actions needs to be developed to meet these serious climate impacts (Opitz-Stapleton et al. Citation2009, p. 2). The Indian cities were involved in two phases of the programme. While Phase I was primarily concerned with the scoping of cities, which subsequently led to selection of cities for detailed assessments and resilience strategy preparation, Phase II of the programme began with three core cities of Surat, Indore and Gorakhpur. TARU was chosen as the implementing partner for Surat and Indore, and Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (GEAG) as the implementing partner for Gorakhpur. During Phase III of the programme, which was termed as the replication phase, four more cities were added to this initiative; Guwahati through the national partner – TERI – and Shimla, Mysore and Bhubaneswar through International Centre For Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) as the implementing partners.

All the seven cities analysed here () are medium sized cities with population ranging from 0.8 to 1.1 million, except Surat which has a population of 4.4 million. Surat, Indore and Gorakhpur were the core cities of the ACCCRN, being the first of the three cities to be taken up. Later in the next phase, Guwahati, Mysore, Shimla and Bhubaneswar were added as the replication cities.

Gorakhpur has grown rapidly into an economic and institutional hub in the region. However, the city has been susceptible to floods and water logging due to multiple factors, such as being located at a level lower than the River Rohin along which it is situated, discharge of excess water from Nepal and city’s bowl-shaped topography. Surat faces the risks of both sea level rise and flooding. The Ukai multi-purpose dam built upstream, 94 km from Surat, was meant for flood control management, irrigation and power generation. During the end of the monsoons, when the dam is near to its capacity, unexpected rains for three to five days can create situations that result in forceful discharge of around 36,811 cusecs (1.3 million cusec), thus, leading to floods in Surat (TARU Citation2011a). During the last two decades, Surat and the surrounding metropolitan region has witnessed major floods. Because Indore is also a major industrial hub in western India, industrial demands are adding to urbanisation pressures. Around 27% of the city’s population currently lives in slums (Rajasekar et al. Citation2012). Out of these, significant proportions of the slums are located along rivers and are prone to floods. During the last decade, three flood events (2002, 2005 and 2009) with increasing intensities have taken place in the city (TARU Citation2011b). The CRS, however, identifies water scarcity as the key problem that the city needs to address as an effect of rapid population growth. Guwahati, the capital of Assam, is an important candidate for the ACCCRN initiative due to its pronounced climate vulnerability, urbanisation pressures and its eco-sensitive location. The city is surrounded by one of the Ramsar notified wetlands, the Deepor Beel which is under threat due to encroachment and unplanned urban development of the city. The city is prone to floods and landslides, and is located on the earthquake belt. Mysore has a moderate climate with summer temperatures ranging from 20°C to 35°C, while the winter temperatures remain in the range of 12–30°C. The civic administration for the city is managed by the Mysore City Corporation. Shimla is a hill city spread on a ridge and its seven spurs. Shimla features a subtropical highland climate as per the Köppen climate classification. The city is one of the most popular hill stations of India. Bhubaneswar is the capital city of Odisha. It has an area of 135 km2, the largest city of the state and has become the centre of economic and religious importance in the region. Bhubaneswar is called the Temple City of India because of the presence of a large number of magnificent temples and its architectural heritage.

gives the summary profiles of the cities taken up for this article.

Table 2. Profiles of the Indian ACCCRN cities.

3. Methodologies adopted

The study reviewed the technical aspects of the methodologies through literature review and the replication potential through a questionnaire survey of the ACCCRN partners and city stakeholders.Footnote3 The literature review included the CRS for Gorakhpur, Guwahati, Surat and Indore; the Vulnerability Assessment Report and Climate Projections Report of Gorakhpur; Phase II Report of Surat and Indore (unpublished) and various papers in peer-reviewed journals. The questionnaire survey for assessing the replication potential was designed with the objectives of:

understanding from the ACCCRN partners the methodological and procedural details in the cities where they have worked

understanding the challenges and opportunities that the partners have faced and their views and experience for the scaling up step

learning about their city’s experience and their views on the process and methodology, data requirement and stakeholder engagements conducted within the ACCCRN process

receiving inputs on how climate resilience could be initiated in more and more cities in India.

4. Overview of methodologies adopted in Indian ACCCRN cities

The Urban Climate Resilience Planning Framework (UCRPF)Footnote4 developed as part of the ACCCRN programme paved the way for city-level resilience planning exercises. It focused on (Moench et al. Citation2011):

urban systems (the foundations on which urban areas survive)

urban agents (the diverse organisations that make up the urban social environment)

urban institutions (the rights, laws, regulations and other social structures that mediate relationships among agents and between agents and systems)

exposure to climate change.

While the Indian ACCCRN partners largely used the core themes of the ACCCRN methodology as the starting point of their resilience building exercises, it was observed that different partners tested different methodologies and used a combination of methods and tools to assess risk and vulnerability in their respective cities and also for the preparation of resilience strategies. The following sections give a brief discussion on the methodologies adopted in the seven ACCCRN cities in India. A comparative review of the methodologies adopted in the seven cities has also been discussed ().

Table 3. Comparative review of methodologies across seven Indian ACCCRN cities.

4.1. Gorakhpur

The Gorakhpur Risk Assessment and Vulnerability Analysis was conducted as part of Phase I of the ACCCRN initiative in India (GEAG Citation2009). GEAG was the primary agency involved in this exercise with support from the Rockefeller Foundation. GEAG’s exercise was based on extensive stakeholder and community engagements using shared learning dialogues (SLD) and PLA tools. The Resilience Strategy addressed a number of cross-sectoral issues in the city, water logging being the primary one. Additionally, the strategy also identified two pilot projects, which are being implemented in the city with ACCCRN support. The first pilot project was about implementing and promoting ward-level micro-resilience planning in one of the identified wards in the city and the second pilot project was about implementing and promoting adaptive peri-urban agriculture in eight surrounding villages of Gorakhpur city (ACCCRN Citation2013). The project involved establishing micro-planning mechanisms in one of the critically affected wards by waterlogging and other issues related to lack of infrastructure and services. The micro-resilience planning included addressing multiple sectors, such as agriculture and livelihoods, solid waste and drainage management, water and sanitation, housing, health and education in a smaller unit like a ward in the city. This new micro-planning model was shared among other wards in the city.

The project targets its activities at three levels:

At the household level: Awareness creation on issues, such as integrated farming and waste management. Flood resilient constructions were carried out with households.

At the neighbourhood level: Community groups were mobilised around issues of common interest, such as health, sanitation, drainage, drinking water, upgraded housing and micro-credit. Technical support was provided to find the technical solutions and climate-resilient agricultural planning was done.

At the ward level: The project engaged with the ward-level committee on issues, such as provision and maintenance of municipal services and conservation of natural water bodies.

4.2. Surat and Indore

In Phase II of the ACCCRN programme in 2009, TARU as the implementing partner began the resilience planning exercise in Surat and Indore. The methodology for the ACCCRN project entailed a detailed vulnerability analysis based on the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) developed by the Department for International Development (DFID), which was contextualised to analyse different aspects of vulnerability and capacity (TARU Citation2010). As per the DFID’s SLF framework, sustainable livelihoods are based on five types of assets or capitals, namely human capital, social capital, natural capital, physical capital and financial capital. In its simplest form, the framework views people as operating in a context of vulnerability (DFID Citation2001). DFID’s SLF framework is based on the following definition of livelihood:

A livelihood is sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks, and maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets both now and in the future, while not undermining the natural resource base (Chambers & Conway Citation1992, p. 6).

GIS-based city-wide vulnerability assessment was conducted to capture current vulnerability, which led to detailed sector studies. In Indore, impact studies were conducted for sectors, such as urban health and environment, transport, water security, energy security and green buildings. In Surat, sector studies examined energy security, water security, health impacts, environmental impacts and flood risk management. Possible future scenarios were developed and presented in the CRS for Surat and Indore.

4.3. Guwahati

In Phase III of the ACCCRN programme in 2011, TERI as the implementing partner began the resilience planning exercise in Guwahati city. The key steps involved in the process included a hazard identification exercise on the basis of literature review, city-level stakeholder consultation and an analysis of the relevant secondary data (TERI Citation2013). Variables, such as topography, population dynamics, socio-economic condition and land use pattern, were studied to understand and identify the vulnerable hotspots, sectors and communities in the context of climate change impacts. For this purpose, climate projections for 2030 at a resolution of 25 × 25 km were conducted for the region to understand the change in temperature (mean, min and max) and precipitation from the baseline. Based on this, adaptation and resilience options to address these risks were identified and a mainstreaming plan was prepared.

4.4. Shimla, Mysore, Bhubaneswar

ICLEI, South Asia, joined the ACCCRN initiative during the replication phase and took up the task of replicating the ACCCRN process in the cities of Shimla, Bhubaneswar and Mysore. The methodologyFootnote5 adopted by ICLEI was based on ISET’s urban resilience principles (Moench et al. 2011; Tyler & Moench Citation2012) developed for ACCCRN and ICLEI’s own experience of working with the cities. Unlike other cities, the methodology did not rely heavily on climate projections or impact modelling. The climate impact assessments for Shimla and Bhubaneswar were derived from India’s 4 × 4 Assessment Report (MoEF Citation2010). For Mysore city, IISC Bangalore’s assessment was used. The analysis of urban systems included a detailed study of the fragile urban systems and the risks they would face due to climate change impacts (Tewari Citation2013). Vulnerability hotspots were located and sector-wise resilience actions were proposed in the three cities.

5. Discussion: replication potential of the technical components of ACCCRN methodologies

In all the cities, the basic format of engagement was same although the methodologies differed. The difference in methodologies seems to have arisen as a result of the following factors:

Contextual difference between the cities, such as the size of the city, geo-topographical features of the city, etc. For example, Guwahati is situated on the banks of the river and is located in a bowl-shaped valley surrounded by hills, whereas Shimla is a hill station in Himachal Pradesh.

ACCCRN partner’s level of comfort with the quantitative and qualitative assessments. The partners used their methodologies as per their specific experience and understanding of the issues related to climate change. While in Gorakhpur, the vulnerability and risk assessment were driven by participatory, qualitative processes. In Surat, the emphasis was given on quantitative assessments using primary surveys and sector specific studies that detailed out impacts of climate change on specific sectors.

Availability of data and its quality. Most of the Indian cities lack a unified database management system. Few cities have started building computerised databases but most of the smaller cities still employ manual means to store data. As a result, much time is being spent by the partner organisation for collecting and managing data as per the requirement of the resilience planning exercise. In other cases, the exercise was re-defined in view of the data gaps. For example, in Shimla, Bhubaneswar and Mysore, ICLEI conducted the resilience building exercise based on the data that was available with the city government.

Extent of city engagement in the process. The process needed consultations from stakeholders to be realistic and grounded to the local realities, perceptions and needs. It was, therefore, necessary that the city level and the state level government departments remain engaged on a regular basis with the programme. The extent of city’s engagement with the programme had direct implication on the achievement of desired objectives.

The different timeframes under which these studies were conducted for core cities (2–2.5 years) and replication phase cities (less than 1 year). The core cities of Surat, Gorakhpur and Indore had a timeframe of 2–2.5 years to conduct the assessments as the programme was new and initiatives for resilience framework were still in the initial phase. However, the timeframe allotted for the replication cities ranged from 9 months to 1 year, and hence it affected the scope of the study.

5.1. Risk assessment

In case of Surat and Indore, though the primary survey-based and GIS-driven vulnerability assessment techniques were technically sound, they were also data and time intensive. To perform such exercise in other cities, it will require access to software, techniques and skilled manpower which may or may not be available. On the other hand, in Shimla, Bhubaneswar and Mysore, the methodology was adapted according to the availability of data in the city. In Guwahati, the approach involved conducting urban profiling to assess the current urban pressures and deficiencies and this was then integrated with the climate profiling to understand the current and future climate-related vulnerabilities.

Use of local knowledge is an important component of resilience planning and would be an important asset for contextualisation and replication in other cities as well. This was observed in case of Gorakhpur, where the local knowledge and expertise was used for the vulnerability analysis and associated sector studies, such as geo-hydrological study. For this purpose, various PRA/PLA tools were identified and were used for SLDs and community consultations (Wajih et al. Citation2010).

In the context of climate projections, it was observed that in some cities detailed projections were conducted and formed an essential component of the climate resilience planning process. In other cities, the methodology did not rely too heavily on these projections. This can be attributed to the implementing partner’s own comfort levels and the availability of data required for this kind of assessment. The partners reiterated that to undertake such assessments, skilled expertise is required which is available only in few institutions across the country. It was also observed that the climate modelling exercise conducted used different time frames ranging from 2015–2030 to 2045–2060 scenarios. The authors feel that taking longer time frames might make it difficult to align climate projections with the planning process. Decision and policy timeframes are often more immediate, 10–20 years at the longest and more local than the scales offered in climate projection information (Moench et al. Citation2011).

5.2. City resilience studies

The CRS were developed as an outcome of the risk assessment exercise. In the core cities, critical sectors for intervention and pilot projects were also identified in this stage. The CRS documents outlined a framework of strategies that could be adopted by cities to reduce their vulnerability and for building resilience in response to the risks of climate change. For core cities, the CRS documents helped in identifying the pilot projects which were subsequently supported by the Rockefeller Foundation for implementation. However, there was no roadmap for the implementation of the whole CRS, except in Gorakhpur and Guwahati, where a mainstreaming action plan was also prepared by the partner TERI with an objective to integrate the CRS into the urban development planning framework.

6. City stakeholder experiences

Apart from understanding the methodology adopted by the cities, the objective of the questionnaire-based discussions with the key city stakeholders was also to understand their experience with respect to the process that was adopted by the respective partner organisation in their city. Several issues and suggestions emerged from the discussion, which can guide engagements in future replication cities. A more detailed discussion on these experiences and challenges follows.

6.1. Motivation of the cities for planning for resilience

Outcomes of the questionnaire survey revealed that addressing present vulnerabilities seems to be an equally important motivating factor for cities to take up resilience planning exercises apart from an understanding to climate proof themselves to future climate impacts (). In the ACCCRN context, most of the respondents felt that the programme addressed the existing problems and challenges of the cities in some way. For example, in Surat and Gorakhpur flooding and water logging is a thing of concern to the municipal bodies. Similarly, in Guwahati, the city felt that the ACCCRN process would be able to bring in a holistic approach to the urban development planning paradigm in the city and would help them tackle the problems arising out of frequent floods considering its changing patterns.

Table 4. Responses from city stakeholders on motivation for their involvement in resilience planning exercise.

6.2. Methodology

The city respondents encountered certain challenges in the methodologies adopted in their respective cities (). These refer to understanding the methodology and the concepts, data availability, climate projections and the extent of stakeholder participation. The city stakeholders felt that when the project started, there was very little understanding of climate change and its inter-linkages with various urban systems. This initially posed a challenge in understanding the methodology for the resilience building exercise being undertaken as part of the ACCCRN initiative. It was observed that awareness generation and capacity-building programmes to sensitise the city-level stakeholders and practitioners could harness support and buy-in as well as facilitate replication exercises.

Table 5. Responses on challenges experienced with methodology and data.

In terms of the risk assessment exercise, it was felt by the respondents that conducting quantitative and qualitative sectoral assessment could prove to be relatively easier for the city-level public agencies as they have data and expertise on their respective subject. However, cities will require continued support from external experts while relating urban issues with climate science and during the vulnerability analysis stage.

6.3. Data

As discussed above, most of the Indian cities do not have a comprehensive database management system due to which data acquisition is a challenging process for any city-level planning exercises. Respondents from all the seven cities faced similar challenges during the vulnerability assessment stage as the data was either not available at all or, if available, was not in the required format and scale (). It was observed that city-level data repositories based on secondary data, focused engagements and primary surveys are needed for urban climate resilience planning.

6.4. Climate projections

The city respondents felt that the climate modelling/projections need to be strengthened for a robust resilience planning exercise (). However, they also observed that currently the cities do not have the capacity to conduct this exercise on their own and will need external support in this regard. It was suggested that the cities will benefit if this is taken up with support from the government of India/state governments. It was also suggested that this climate modelling exercise should be accompanied with impact assessments on urban sectors.

Table 6. Responses on components of the methodology to be strengthened.

6.5. Participatory component

The levels of participation varied from city to city in the ACCCRN process. The city stakeholders felt that the participatory component of the methodology should be strengthened to utilise local knowledge and to integrate the cities’ vision and perceptions into the resilience planning exercise ().

In terms of community engagement the city respondents felt that there was partial engagement of the community in the process. This was mainly limited to the initial stages to seek inputs on identifying the primary risks and to an extent for the implementation of the pilot projects in the core cities. However, both partners and city stakeholders were not sure how and to what extent this engagement could be strengthened. It was felt that the process was too technical and it might not be feasible to involve communities in the intermediary stages and this will be a time consuming process. Some of the stakeholders felt that a more intensive community engagement may lead to deviation from the objective of the exercise. This was attributed to the observation that many a time the discussants tend to deviate to topics and issues which are beyond the scope of the exercise, which defeats the purpose of the discussion.

6.6. Implementation support

The city stakeholders were questioned on the kind of support the cities will require for initiating action on climate resilience. It was observed that in absence of any policy/statutory backing, it would be a challenge to implement the resilience strategy completely. It was pointed out that unless climate change is part of the mandate for municipal corporations, any resilience planning exercises would be seen as an additional burden. The stakeholders suggested that the climate action should be initiated at the city and state levels.

The respondents stressed the need for capacity building support as well as policy and financial support. It was also emphasised that there is a need for building technical expertise and acquiring skilled manpower both at the urban local body (ULB) as well as at the state level (). The importance of toolkits and capacity building programmes for cities was highlighted in this regard.

Table 7. Responses on the required support needed by the city to initiate climate action.

6.7. Finance

There are no financing mechanisms marked currently for urban climate resilience at the city or the state level in India. The respondents suggested a range of financing options for replicating resilience planning exercises in Indian cities. These included resource allocation by national and state governments and facilitating direct funding from multilateral/bilateral sources for implementation of infrastructure projects at the city level.

It is felt by the authors that budget analysis of various public agencies including municipal corporations at the city level, as part of the CRS, will help in formulating a finance mobilisation plan for resilience building.

7. Key lessons drawn from the ACCCRN experience – pointers for replication

The study captured the inputs of those who spearheaded the methodology and were involved in the process and will ultimately implement the prepared strategies. These include the technical consultants and the city stakeholders.

7.1. Awareness and capacity building

If resilience planning is to be attempted in other cities and the cities have to lead the effort by themselves, the first step would be to extensively build capacities of various stakeholders. In ACCCRN this task was taken up by ACCCRN partners who engaged with the city officials and other city stakeholders at various stages of the programme. For greater benefit, however, it is recommended that toolkits, guidelines and training programmes should be developed for cities so that they are well equipped to take up the resilience planning. The toolkits may give guidance on the following:

conducting risk assessments

urban profiling

vulnerability assessment

sectoral impact studies

data collection and management (formats, frequency, timeframe)

mechanisms for including participatory components and identifying relevant stakeholders

formulation of CRS and prioritisation of adaptation projects.

While the required capacity generation would take time as it has to be targeted at multiple levels, the actual risk assessments for climate impacts at urban scale has to be facilitated amongst the ULBs.

7.2. Methodology

The methodology should be such that a city can conduct quick and easy assessment of their risk and vulnerability to climate impacts considering the time, capacity and absence of supporting policies with the city government. This is suggested because in ACCCRN, while the project duration for core cities ranges from 1.5 to 2 years, the time frame allotted to replication cities was too less ranging from 9 months to 1 year only. Based on the experience of the ACCCRN cities, the following recommendations at various stages of resilience planning exercise are proposed.

7.2.1. Risk assessment

7.2.1.1. Climate projections

The cities can analyse past climate trends in-house. They require external support for climate projections and detailed modelling exercises. The state government could commission detailed studies and disseminate the outcomes to the cities and maintain a repository of the climate modelling results.

7.2.1.2. Vulnerability assessment

This stage would require some toolkits and guidelines, which will assist cities to conduct urban profiling and vulnerability assessment. Climate projections, as suggested earlier, would also require some external support.

Local knowledge and expertise should be integrated into the process to ascertain that the local priorities and problems at the grassroots level are addressed.

Separate toolkits/questionnaires/primers should be developed to involve community in the process.

7.2.1.3. Sectoral impact studies

Sectoral impact studies should be conducted to understand the risks across sectors. Sectoral studies involve a detailed spatio-temporal analysis to provide a strong basis for detailed project report (DPR)Footnote6 preparation and prioritisation of required interventions.

7.2.2. City resilience strategy

Resilience is a continuous process, and therefore it is important to identify actions in the short, medium and long-term context and to have mainstreaming action plans for implementation of the overall CRS.

Key adaptation projects should be identified for implementation and require preparation of DPRs for potential funding. Alternative financing options should also be considered. This area has not yet been explored under the ACCCRN framework and needs to be developed for replication of the process in other cities.

The experience from ACCCRN cities has revealed that city authorities should prevent poor quality data, which prevents them conducting accurate and useful calculations and assessments of the climate risks and associated vulnerability on various urban sectors.

Hence, it would be beneficial to develop toolkits for guiding the city authorities on data upkeep and management. The proposed toolkit should also have a component on the type of data, the frequency of data and the timeframe within which the data will be essentially required. For example, for the climate trend analysis the climate data of at least 30 years is required. The city that proposes to plan for resilience would have to maintain and regularly update the required database through a database management system (DBMS).

While data feeds into the more technical part of the assessment, a lot of crucial and practical information comes from stakeholders. Resilience building strategies have shown very clearly that there needs to be a strong participatory component to a resilience exercise. The city respondents laid stress on strengthening this component of the methodology. Based on the city context, appropriate representation of all types of stakeholder groups should be ensured.

7.5. Institutionalisation

There is a strong need to institutionalise the resilience building process at the city level. Because climate resilience would have implications for various sectors, such as urban development, resource management, disaster management, environmental management and conservation, the range of the task would actually go beyond ULBs. Recognising that resilience actions like adaptation projects are embedded within an institutional system which may have particular goals (Cannon & Müller-Mahn Citation2010), resilience building may be integrated to the existing institutional system or could also seek to promote or bring in new systems at places that support resilience projects’ implementation. Therefore, the cities would have to identify the relevant stakeholders and build in a process whereby regular consultations with stakeholders and inter institutional coordination are materialised. A separate cell could be constituted in the municipal corporation for this purpose. This cell could have ex officio representatives from relevant city-level sectoral departments and state line departments. The cell could be chaired by the divisional commissioner, with the municipal commissioner as the member-secretary, to ensure interdepartmental coordination, communication and engagement of various city-level and state line departments. In the absence of institutionalisation and vetting of responsibilities, the agenda for resilience planning may be subsumed within the regular development priorities of a municipal body.

7.6. Policy and implementation support

The experience from ACCCRN has also proved that the new cities would need support in terms of capacity, policy and finance from the state government for the implementation of the resilience strategy. While all the ACCCRN cities engaged in the process showed utmost interest in the process; however, complete adoption and implementation of the same was not possible for them considering the lack of funds and a clear mandate from the state government. The cities wanted state government approval for implementing the resilience strategy, even for partial implementation. Therefore, policy and mandates at state and national level are needed for long-term sustainability and complete success of this initiative. A mandate from state governments, either linked with the respective state action plans on climate change or the state environment or urban development policy, would go a long way in ensuring action by the urban areas to address climate change impacts. A national government policy would permit the state as well as the cities to initiate resilience building efforts. It is important, however, that each of these policies or mandates are defined clearly and propose a detailed ecosystem of implementation, financing and institutional responsibilities. Extensive replication would only be possible when the governance systems are designed, updated and channelized towards the goal of resilient cities.

8. Conclusion

The seven-year ACCCRN initiative has introduced the concept of urban resilience planning in selected Asian cities. With the expansion of the network to more and more cities, it is now imperative that the learning and experiences of the pioneer ACCCRN cities feed into this scaling up and replication process. This article brings about the critical issues for replication of ACCCRN process and methodology, based on the experiences of the partners and city stakeholders from the Indian ACCCRN cities. The discussions and recommendations are aimed at guiding the resilience planning exercise in cities that may choose to follow this in future. The article particularly makes recommendations to cities on the prerequisites and key features of the methodologies to be adopted for developing climate resilience plans. For enabling these exercises, the need for reforms in the policy and institutional arrangements has also been highlighted. Besides this, capacity building measures (like toolkits), climate projection analysis and data management systems need to be developed at the city level to inform decision-making and for developing resilience strategies. Interviews and interactions with the city partners and city officials are needed to develop a strong policy mandate at the national and state level for formulation and implementation of the city level climate resilience strategy.

Funding

This work was supported by the International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED), London under the ACCCRN initiative [IIED Project Code 719.05].

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), London, for granting this study to The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) under the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN) initiative and providing their inputs at various stages of the study. Of particular mention is the support from all the national partners to ACCCRN in India – ICLEI, Institute of Social and Environmental Transition (ISET), Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (GEAG) and TARU Leading Edge Private Limited (TARU), and the stakeholders and practitioners in the seven ACCCRN cities, who extended their time and support to TERI during the course of the study. Finally, our sincere thanks are due to all the senior colleagues and reviewers associated with this project within TERI.

Notes

1. This article is based on a research study entitled ‘Urban resilience: A review of the methodologies adopted under the ACCCRN initiative in Indian cities’. The detailed working paper on the study has been published by IIED, London, as part of the ACCCRN Working Paper Series and can be accessed at http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/10650IIED.pdf

2. The initiative has now been extended up to 2016.

3. These include officials from the municipal corporation and other public agencies, academics, local subject experts and representatives from non-government/private sector who were involved in the ACCCRN initiatives in their respective cities.

4. The Urban Climate Resilience Planning Framework (UCRPF), developed by ISET and Arup, focuses on resilience as a goal that is not merely responsive to predicted climate impacts, but also fosters proactive and systemic approaches to face unexpected and indirect effects of global change.

5. The vulnerability assessment studies/resilience strategies for Shimla, Mysore and Bhubaneswar have not yet been published. This discussion is based on interviews with the implementing partner, ICLEI.

6. The DPR is an essential step in planning for infrastructure development and service delivery.

References

- ACCCRN. 2013. Implementing and promoting ward-level micro resilience planning [Internet]. New York: The Rockefeller Foundation; [cited 2013 Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.acccrn.org/initiatives/india/gorakhpur/city-projects/implementing-and-promoting-ward-level-micro-resilience-pla

- Brown A, Dayal A, Rumbaitis Del RC. 2012. From practice to theory: emerging lessons from Asia for building urban climate change resilience. Environ Urban. 24:531–556. doi:10.1177/0956247812456490

- Cannon T, Müller-Mahn D. 2010. Vulnerability, resilience and development discourses in context of climate change. Nat Hazards. 55:621–635. doi:10.1007/s11069-010-9499-4

- Chambers R, Conway G. 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper 296. Brighton: IDS.

- DFID. 2001. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets [Internet]. London: Department for International Development; [cited 2013 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.efls.ca/webresources/DFID_Sustainable_livelihoods_guidance_sheet.pdf

- GEAG. 2009. Vulnerability analysis – Gorakhpur City [Internet]. Gorakhpur: Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (GEAG); [cited 2013 Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.hamaragorakhpur.com/PDF/Vulnerability-Report-PDF-file.pdf

- Jabareen Y. 2013. Planning the resilient city: concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities. 31:220–229. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.05.004

- Leichenko R. 2011. Climate change and urban resilience. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 3:164–168. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2010.12.014

- MoEF. 2010. Climate change and India: A 4x4 Assessment (INCCA Report # 2) [Internet]. New Delhi: Ministry of Environment & Forests (MoEF), Government of India; [cited 2013 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.moef.nic.in/downloads/public-information/fin-rpt-incca.pdf

- Moench M, Tyler S, Lage J, eds. 2011. Catalyzing urban climate resilience: applying resilience concepts to planning practice in the ACCCRN Program (2009–2011) [Internet]. Boulder, CO: Institute for Social and Environmental Transition, International; [cited 2013 Jul 23]. 306 p. Available from: http://www.i-s-e-t.org/images/pdfs/ISET_CatalyzingUrbanResilience_allchapters.pdf

- OECD. 2010. Cities and climate change [Internet]. Paris Cedex 16: OECD Publishing; 276 p. [cited 2013 Jul 17]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264091375-en

- Opitz-Stapleton S, Seraydarian L, Macclune K, Guibert G, Reed S, eds. 2009. Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN): responding to the urban climate challenge. Working paper [Internet]. Boulder, CO: Institute for Social and Environmental Transition; [cited 2013 Jul 20]. 60 p. Available from: http://ssi.ucsd.edu/scc/images/Asian%20Cities%20CC%20Network%2011.pdf

- Rajasekar U, Bhat GK, Karanth A. 2012. Tale of two cities: developing city resilience strategies under climate change scenarios for Indore and Surat, India [Internet]. [cited 2013 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.acccrn.org/sites/default/files/documents/TaleofTwoCities_TARU.pdf

- Sharma D, Singh R, Singh R. 2013. Urban climate resilience: a review of the methodologies adopted under the ACCCRN initiative in Indian cities [Internet]. Asian Cities Climate Resilience Working paper series, number 5, London: IIED; [cited 2013 Feb 11]. Available from: http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/10650IIED.pdf

- TARU. 2010. Phase 2: city vulnerability analysis report (Indore & Surat) [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jul 23]. Available from: http://www.imagineindore.org/resource/VA_Report_27Feb/ACCCRN%20II%20Report%20Draft%2025Feb10.pdf

- TARU. 2011a. Surat city resilience strategy [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jul 22]. Available from: https://acccrn.org/sites/default/files/documents/SuratCityResilienceStrategy_ACCCRN_01Apr2011_small_0.pdf

- TARU, 2011b. Conjunctive water management: Indore [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.acccrn.org/sites/default/files/documents/Poster_CWM%20Project_Indore_Feb2011_Final%20a4_0.pdf

- TERI. 2013. Climate proofing Guwahati, Assam: City resilience strategy and mainstreaming plan (Synthesis Report). New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. 72 p.

- Tewari S. 2013. ICLEI ACCCRN process. Presented at: International Conference on Resilient Cities: Experiences from ACCCRN in Asia and Beyond; New Delhi, India.

- Thornbush M, Golubchikov O, Bouzarovski S. 2013. Sustainable cities targeted by combined mitigation–adaptation efforts for future-proofing. Sustainable Cities Soc. 9:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2013.01.003

- Tyler S, Moench M. 2012. A framework for urban climate resilience. Clim Dev. 4:311–326. doi:10.1080/17565529.2012.745389

- UNISDR. 2009. UNISDR terminology on disaster risk reduction [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.unisdr.org/preventionweb/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf

- Wajih S, Singh B, Bartarya E, Basu S, Team ACCCRNISET. 2010. Towards a resilient Gorakhpur [Internet]. Gorakhpur: Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (GEAG); 19 p. [cited 2013 Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.hamaragorakhpur.com/PDF/Towards-a-Resilient-English.pdf